- 1The First School of Clinical Medicine, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China

- 2Department of Endocrinology, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 3Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China

- 4School of Nursing, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China

Objective: To reveal the association between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation in medical students and explore the potential mediating roles of alexithymia and psychological resilience.

Methods: Based on a cross-sectional survey conducted at a medical university in Anhui Province, 2,377 medical students were included. Assessments were performed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale, the Resilience Scale, and the Suicidal Ideation Scale.

Results: Our results showed that childhood trauma significantly increased the risk of suicidal ideation in medical students (β=0.500, 95% CI: [0.470, 0.540]; The association was mediated by an alexithymia-resilience chain (mediating effect β=0.03, 95% CI: [0.029,0.040].

Conclusion: Emphasizing attention to medical students’ childhood trauma experiences, focusing on enhancing their emotion-processing abilities, and promoting psychological resilience represent effective strategies for preventing suicide risk in this population.

1 Introduction

Suicide among university students has become a major challenge in the realms of campus public health and safety due to its unpredictability. Medical students face unique professional and occupational demands and their mental health is crucial for individual growth and development. Medical students showed more severe anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies compared to the average levels among university students in other disciplines (1). Academic stress is prevalent among contemporary college students; however, medical students are confronted with a unique set of severe long-term stressors. These stressors cumulate and interact with one another, and compared to their peers in other majors, this cumulative effect significantly elevates the risk of adverse mental health outcomes in medical students. First of all, medical students have a heavier academic burden, they must master a large amount of complex scientific and clinical knowledge, which is directly related to their future career prospects, and there are many high-risk exam pressures (2). Second, intense coursework, clinical rotations, and self-study schedules inevitably lead to long-term sleep deprivation, which directly impairs emotion regulation, cognitive function, and coping mechanisms, and exacerbates vulnerability to stress and psychopathology (3). Third, medical students are prematurely and repeatedly exposed to human suffering, death, and moral dilemmas during their clinical training, leading to particular emotional distress that may contribute to internal stress and emotional depression (4).

Suicidal ideation refers to thoughts or cognitions about ending one’s own life and is a necessary psychological precursor to suicidal behavior. Over the past decade, the prevalence of suicidal ideation among Chinese medical students has been approximately 13% (5). A latent profile analysis of suicide risk factors in university students revealed that, in terms of individual vulnerability factors, borderline personality traits, deficits in emotional regulation ability, childhood trauma, impulsive personality traits, negative coping with stress, and psychological resilience constitute risk factors for suicidal ideation (6).

Childhood trauma refers to any form of abuse and neglect experienced during an individual childhood development (7). As an early-life environmental factor, childhood trauma serves as an important predictor for numerous psychiatric disorders (8). Studies indicated that childhood trauma was associated with a substantially increased risk of adolescent suicide and suicidal ideation (9). Suicidal behavior is linked to an individual inherent diathesis and exposure to traumatic events. Childhood traumatic experiences not only represent persistent underlying factors but also constrain the development of psychological resilience. Severe trauma may precipitate alterations in personality structure, ultimately elevating suicide risk in adulthood (10). This study aims to investigate the impact of childhood trauma on suicidal ideation among medical students and elucidate its underlying mechanisms.

Alexithymia, also referred to as “Emotion Articulation Disorder” or “Affective Expressiveness Impairment,” denotes an individual’s impairment in identifying others’ emotions and expressing their own emotions. It manifests primarily as difficulties in emotion recognition, emotion expression, and externally oriented thinking (11). Research on the formation mechanisms of alexithymia indicates that its development correlates with adverse childhood experiences. It arises from disruptive events and relationships that inhibit the development of emotional functioning during early childhood (12), with subsequent reinforcement through sociocultural and relational contexts. Alexithymia is recognized as an impairment in emotion cognition, processing, and regulation (13). Concurrently, an individual’s level of alexithymia is closely associated with physical and psychological symptoms. Due to deficits in emotional cognitive regulation and maladaptive emotion management strategies, individuals with alexithymia tend to employ dysfunctional defense mechanisms when confronting negative events. This increases their susceptibility to psychological problems, including suicidal ideation and behavior, exerting detrimental effects on physical and mental health (14, 15). Based on this evidence, it can be hypothesized that alexithymia may mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation in university students.

In real-world contexts, however, not all individuals with childhood trauma histories develop severe psychological disturbances. Luthar et al. proposed that protective factors that enable individuals to cope with adverse environments or crises can promote positive psychological development among trauma-exposed children—one such factor being psychological resilience (16). Richardson’s (2002) Dynamic Model of Resilience posits that the interaction between protective and risk factors drives individuals through cycles of balance, imbalance, and rebalance across physiological, psychological, and social domains—a process that underlies the development of psychological resilience. Childhood trauma, as a chronic stressor, disrupts protective and adaptive systems, thereby hindering the development of psychological resilience (17). Studies of children, adolescents, and university students consistently demonstrate that childhood trauma negatively predicts an individual’s level of psychological resilience and impairs its development (18, 19). As a buffering protective mechanism for mental health, psychological resilience mediates or moderates the relationship between negative life events and psychological problems such as depression (20, 21). Sher’s research identified psychological resilience as a critical protective factor against suicide-related psychological behaviors (22), while Stark et al. found it negatively predicts suicidal ideation in adolescents (23).

Alexithymia prevents individuals from effectively managing the negative emotional states resulting from childhood trauma. The inability to recognize and regulate painful emotions consumes cognitive resources that could otherwise be used for adaptive coping and problem-solving, thereby diminishing the capacity for psychological resilience (24). Alexithymia is characterized by deficits in identifying and describing one’s own emotions, and it also impairs empathy and the ability to interpret the emotional states of others. This makes it difficult to form and maintain close, supportive interpersonal relationships. As a result, individuals may lack the key social buffers that promote psychological resilience (25). Individuals who have experienced childhood trauma often develop alexithymia as a defense mechanism to avoid the unbearable pain. This emotional processing defect directly weakens the foundation of psychological resilience through multiple pathways (26). Alexithymia is not only a related factor but also an important mechanism that partly explains how early trauma leads to the continuous weakening of resilience. Consequently, higher levels of psychological resilience facilitate maintenance of healthy psychological states and reduce the incidence of suicide-related behaviors. Thus, this study will examine the role of psychological resilience in the association between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation among medical students.

Emotion management ability also constitutes a significant factor in the development of an individual’s psychological resilience. Research indicates that individuals with proficient emotion management abilities attain higher levels of psychological resilience (27). Conversely, alexithymia—characterized primarily by deficits in emotion-related cognition and regulation functions—impedes the development of psychological resilience. In their investigation of the relationship between alexithymia and psychological resilience, Craparo et al. found significant negative correlations between alexithymia and all dimensions of psychological resilience (28). Similarly, Morice et al. identified a negative correlation between alexithymia and psychological resilience when examining the predictive role of alexithymia, further demonstrating that lowering alexithymia levels enhances psychological resilience (29). Research indicates that affective temperaments constitute a genetic factor in mood disorders. These emotional dispositions contribute to complex conditions such as psychiatric syndromes, personality disorders, and suicidal behavior, while also influencing disease progression and treatment adherence (30). Consequently, personality and affective temperament may also serve as precipitating factors for suicide, warranting further investigation.

Therefore, this study will first investigate whether alexithymia and psychological resilience act as a chained mediating pathway between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation in university students. On this basis, we hypothesized that alexithymia and psychological resilience would sequentially mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation among medical students.

2 Research methods

2.1 Participants

This study employed random sampling to recruit medical students from a medical university in Anhui Province as participants. Scale assessments were administered through group testing. We selected all undergraduate students majoring in clinical medicine, anesthesiology and nursing from the first to the fifth year of a medical university. Stratification was conducted based on medical specialties and grades, resulting in a total of 15 strata. We obtained the list of all students’ student numbers, names, specialties, grades, and genders from the university’s academic affairs office. The margin of error was set at 5% and the confidence level was set at 95%. Following the exclusion of incomplete questionnaires, 2,377 valid responses were retained (1,176 males, 1,201 females; mean age = 19.03 ± 1.33 years). All participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and significance and provided written informed consent prior to participation. The research protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the first author’s affiliated university. Students identified with high suicidal ideation through screening received follow-up interventions conducted jointly by clinical experts from the research team and psychological counselors at the university’s student mental health center.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Childhood trauma questionnaire

Childhood trauma was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF), originally developed by Bernstein et al. (1998). The Chinese version validated by Zhao Xingfu et al. was used. The 28-item scale evaluates five clinical subtypes of maltreatment: Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Emotional Neglect, and Physical Neglect. Participants scoring in the ‘Low’ to ‘Severe’ range on any subscale were considered to have a positive history of that specific type of childhood maltreatment (31). Each subscale contains 5 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). In this study, we tallied the total score of the scale. A higher score indicates more severe childhood trauma. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.720 in this study, indicating good reliability and validity.

2.2.2 Toronto alexithymia scale

Alexithymia was assessed using the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20). The instrument comprises three dimensions: Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF), Difficulty Describing Feelings (DDF), and Externally Oriented Thinking (EOT). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.726 in this study, indicating adequate reliability and validity.

2.2.3 Positive and negative suicide ideation inventory

Suicidal ideation was measured using the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation inventory (PANSI), translated and revised by Wang Xuezhi et al. (2011). This 14-item scale employs a 5-point response format from 1 (“never like this”) to 5 (“always like this”). The PANSI contains two subscales: Positive Suicide Ideation (6 items, reverse-scored) and Negative Suicide Ideation (8 items, forward-scored). Higher total scores indicate greater severity of suicidal ideation. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.902 in this study, demonstrating excellent reliability and validity.

2.2.4 Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10)

Psychological resilience was measured using the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10), abbreviated by Campbell-Sills et al. from the original 25-item CD-RISC developed by Connor and Davidson (2003). Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), with higher total scores indicating better psychological resilience. The scale demonstrated excellent reliability in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.961).

2.3 Intervention programs for high-risk groups

Participants with a high risk of suicide determined by scale scores will be followed up by phone by our team’s well-trained psychologists, who will provide them with moderate psychological education and strongly recommend that they seek professional help. We will also help them contact the university’s mental health services and continue to maintain follow-up contact to ensure that they successfully receive professional services.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0. Descriptive statistics characterized continuous normally distributed variables as mean ± standard deviation. Pearson correlation analysis examined inter-variable relationships. A chained mediation model was tested using Hayes’ PROCESS macro version 3.3. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of variables

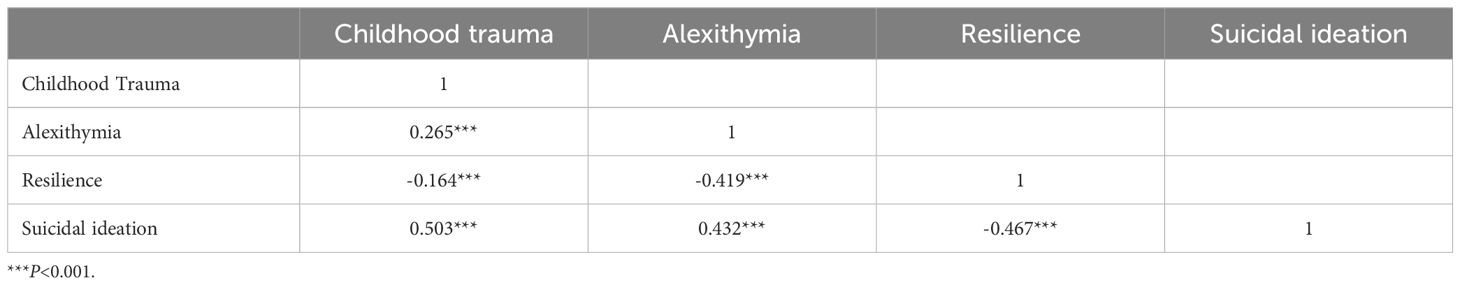

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were performed for all variables. Results indicated that: Childhood trauma, alexithymia, and suicidal ideation were significantly positively correlated between each pair of variables; Psychological resilience showed significant negative correlations with childhood trauma, alexithymia, and suicidal ideation (Table 1).

3.2 Mediation effects of alexithymia and psychological resilience

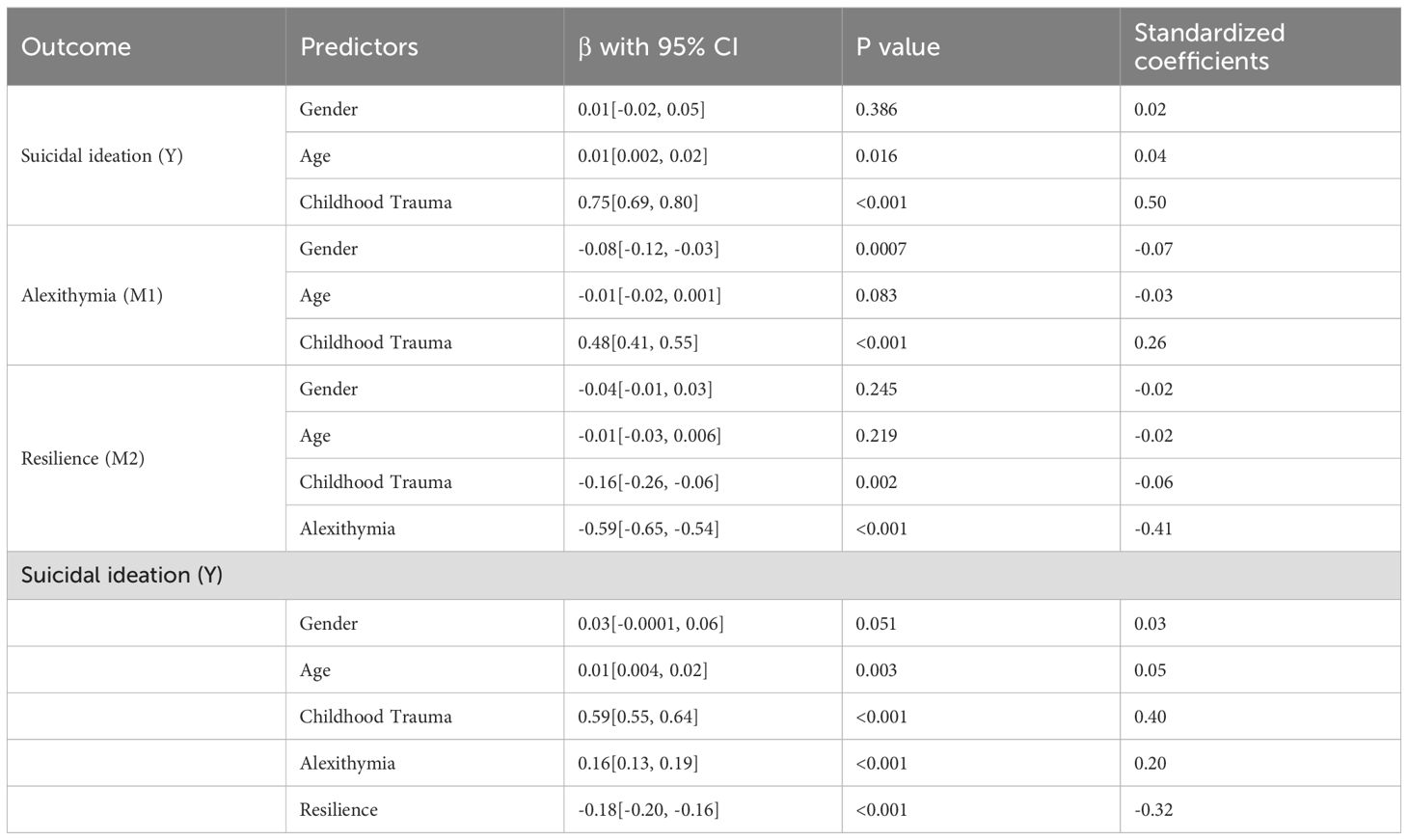

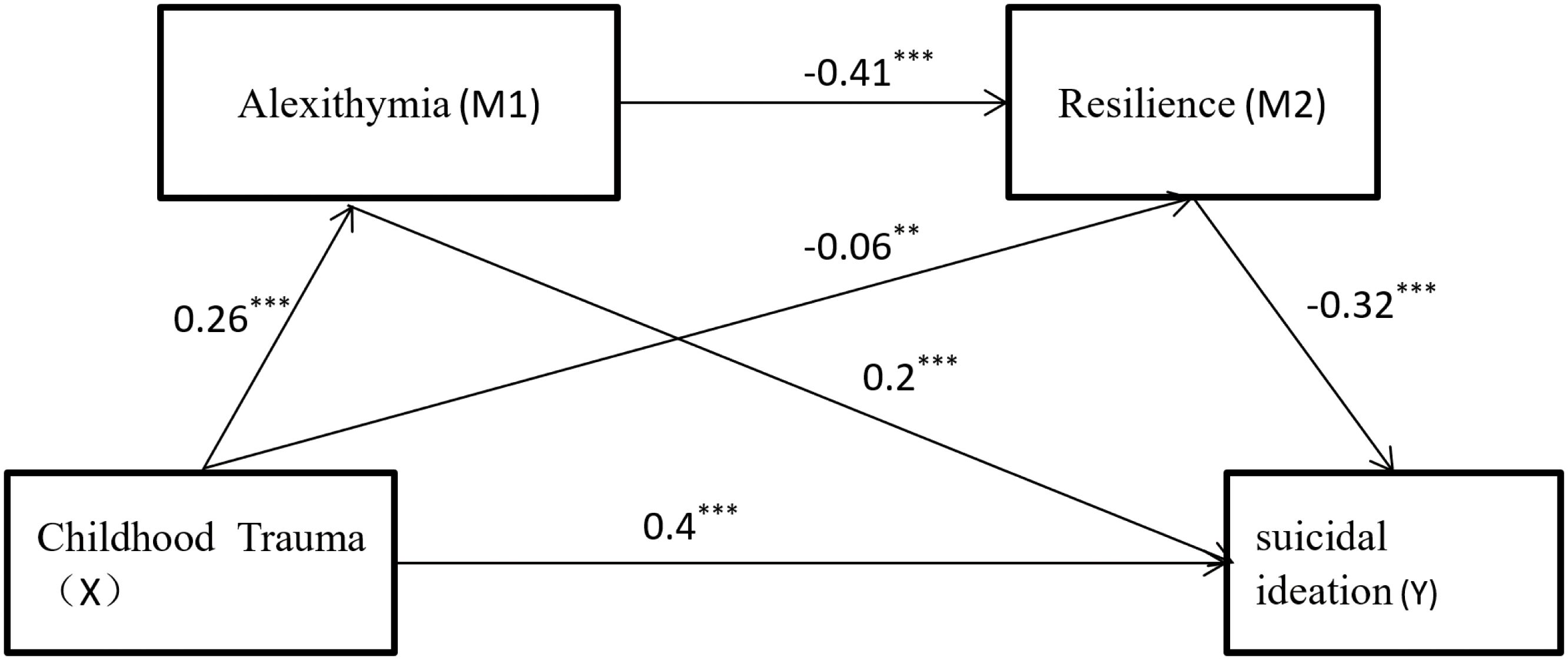

Mediation analyses were conducted using PROCESS 3.3 in SPSS, with gender and age as covariates, to test the bootstrap-based mediating effects of alexithymia and psychological resilience on the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation. Regression results (Table 2) demonstrated that: After introducing mediators, childhood trauma exerted a significant direct effect on suicidal ideation (β=0.400, 95% CI [0.370, 0.430]), accounting for 80% of the total effect. Childhood trauma positively predicted alexithymia (β=0.260 [0.220, 0.300], p <0.001) and negatively predicted psychological resilience (β = -0.06 [-0.100, -0.020], p < 0.01). Alexithymia negatively predicted psychological resilience (β = -0.410 [-0.440, -0.370], p < 0.001) and positively predicted suicidal ideation (β = 0.200 [0.160, 0.230] p < 0.001). Psychological resilience negatively predicted suicidal ideation (β = -0.320 [-0.350, -0.290], p < 0.001).

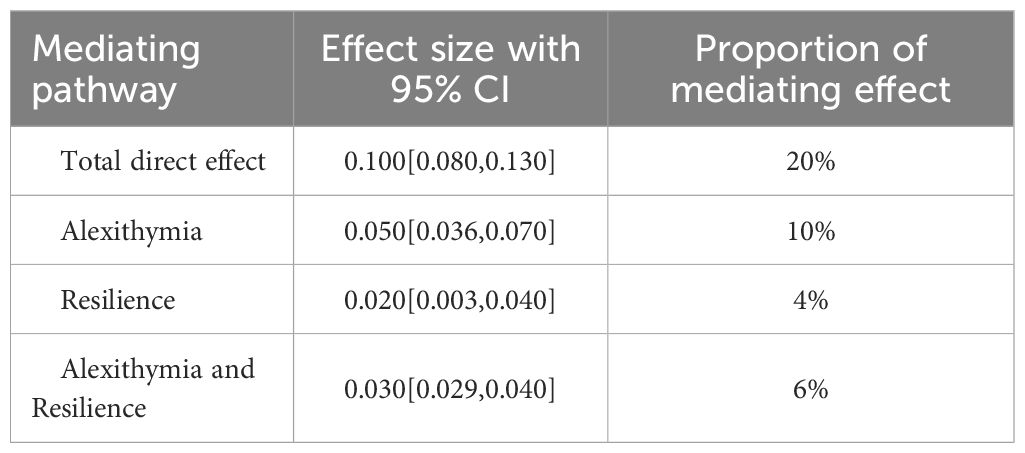

Mediation analysis with 5,000 bootstrap resamples estimated 95% confidence intervals (see Table 3 and Figure 1). Results indicated a total indirect effect of childhood trauma on suicidal ideation of 0.10, accounting for 20% of the total effect (0.50). This mediation comprised three significant pathways: Path 1: Childhood trauma → Alexithymia → Suicidal ideation (Indirect effect = 0.05, 10% of total effect). Path 2: Childhood trauma → Psychological resilience → Suicidal ideation (Indirect effect = 0.02, 4% of total effect). Path 3: Childhood trauma → Alexithymia → Psychological resilience → Suicidal ideation (Indirect effect = 0.03, 6% of total effect). All pathways showed statistically significant mediation (95% CIs excluded zero). In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis stratified by gender to further validate the robustness of the mediation pathway (Supplementary Materials). The results demonstrate that childhood trauma not only directly predicts suicidal ideation in university students but concurrently exerts significant indirect predictive effects through the partial mediation of alexithymia or psychological resilience and the chained mediation effect of alexithymia and psychological resilience.

Table 3. The mediating role of alexithymia and resilience in the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation.

Due to the cross-sectional design of this study and reliance on self-assessment scale data, it may introduce selection bias, recall bias, sampling bias. We have taken corresponding measures to address these biases, for example, statistical test power, scale validity testing, and rigorously designed sampling standards, to achieve good control effects.

4 Discussion

This study elucidates the impact of childhood trauma on suicidal ideation in medical students and its underlying mechanisms. Correlation analyses demonstrated significant positive intercorrelations among childhood trauma, alexithymia, and suicidal ideation, while all three variables showed significant negative correlations with psychological resilience. Regression analyses revealed that after accounting for mediators, childhood trauma maintained a significant direct positive prediction of suicidal ideation. The significant direct effect of childhood trauma on suicidal ideation suggests the existence of other key mechanistic pathways. Future research should prioritize investigating neurobiological dysregulation (e.g., altered stress response in the HPA axis, epigenetic changes, brain structural abnormalities) and psychosocial factors (e.g., prolonged social isolation, fatigue, or frustrated academic achievement) as potential mediating variables (32, 33). Integrating multi-level data, including biomarker testing and detailed social network analysis, is crucial to uncovering the complex etiology of suicide risk in individuals with childhood trauma. Simultaneously, both alexithymia and psychological resilience functioned as partial mediators in the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation, while they additionally operating through a chained mediation pathway whereby childhood trauma influenced suicidal ideation via alexithymia’s impact on psychological resilience. These findings collectively establish alexithymia and psychological resilience as critical bridging factors linking childhood trauma to suicidal ideation in medical students.

Childhood trauma influences medical students’ suicidal ideation through the mediating role of alexithymia. According to the Emotion Processing Model, individuals with a history of childhood trauma tend to adopt avoidant emotion-processing strategies to avoid overwhelming negative emotions triggered by traumatic experiences. While such strategies may provide short-term relief from distress, chronic avoidance can lead to unconscious emotional disengagement and suppression of affect. This process impedes the ability to identify internal emotional states and describe feelings accurately, instead promoting externally oriented thinking, which are the core features of alexithymia (34). Previous studies confirm that childhood trauma functions as a chronic stressor and constitutes a significant etiological factor for alexithymia (35). Alexithymia subsequently increases susceptibility to psychological disorders and maladaptive behaviors (36), with elevated suicide risk (13). Aligned with our findings, medical students exposed to childhood trauma exhibit heightened alexithymia. This emotional avoidance prevents adequate processing of trauma-related negative emotions, thereby amplifying suicidal ideation through blocked emotional expression and feedback.

Our study identified psychological resilience as a significant mediator in the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation among medical students. Specifically, individuals with traumatic histories exhibit reduced psychological resilience, which in turn increases vulnerability to suicidal ideation. This finding aligns with established research demonstrating that psychological resilience functions as a protective factor capable of mitigating the adverse effects of negative life events (37) and reducing susceptibility to suicidal ideation (18) while enhancing adaptive functioning. Concurrently, childhood trauma negatively impacts the development of psychological resilience (19, 38). Chronic exposure to trauma fosters maladaptive cognitive patterns wherein individuals increasingly interpret adverse events through negative schemas, gradually internalizing dysfunctional self-perceptions. This process diminishes self-confidence during stressful encounters, promotes passive coping strategies, and ultimately compromises resilience capacity, thereby precipitating mental health deterioration. These findings suggest that psychological resilience may play a crucial mediating role in the pathway linking childhood trauma to suicidal ideation among medical students.

Mediation analysis revealed that childhood trauma additionally influences medical students’ suicidal ideation through the sequential mediating pathway of alexithymia and psychological resilience. Individuals with alexithymia experience chronic impairment in identifying, describing, and processing emotional states, preventing timely resolution of psychological distress. Prolonged emotional dysregulation may induce sensitization effects, thereby diminishing psychological resilience (39) and eventually increase vulnerability to suicidal ideation (13). These findings corroborate Martin and Pihl’s (1985) stress-alexithymia hypothesis (40), which posits that deficient emotional self-awareness—manifested as confusion or inability to recognize one’s emotions—compromises stressor identification and impedes adaptive coping. Consequently, alexithymic individuals exhibit maladaptive responses to adverse events, characterized by reduced implementation of active strategies such as social support seeking (41, 42). Thus, childhood trauma predisposes individuals to alexithymia, which subsequently impairs resilience development, promotes passive coping strategies during adversities, and ultimately elevates risk for suicide-related outcomes including suicidal ideation. In addition, the mechanism of how affective temperament affects suicidal ideation and resilience needs to be further explored, and its mediating or moderating effect on the onset of affective disorders needs to be further explored (30). Incorporating the assessment of temperament traits into the multidimensional psychiatric diagnostic process can optimize treatment and prognosis estimation.

It is worth noting that this study was carried out in a specific socio-cultural context in China, especially for the Chinese medical student population. China has a unique cultural background, such as an emphasis on academic achievement, filial piety, and a special attitude towards mental health and suicide. These factors may affect the manifestation of childhood trauma, the expression of alexithymia, and the formation of suicidal ideation. Therefore, the strength of association observed in our model and the proposed mediating paths may not be directly generalized to Western cultures or other different cultural contexts. In addition, on sensitive topics such as childhood trauma, the self-reports of the study subjects are affected by recall bias. At the same time, this paper uses a cross-sectional study, which cannot make any definite causal inference about the relationship between variables. Therefore, we have avoided making statements about causality in the text to enhance the rigor of the article.

Finally, we propose corresponding limitations and future research directions. For example, longitudinal design is used to determine time series and causal relationships, combined with multiple methods to evaluate results, reduce dependence on self-reported data and recall bias, conduct cross-cultural reproduction studies, and test the universality of the model. In the future, experiments can also be conducted to test the hypothesis that reducing alexithymia and enhancing psychological toughness can effectively reduce the risk of suicide in students with a history of childhood trauma. Furthermore, future research could inform the development of targeted interventions to address emotional processing deficits and emotional dysregulation—such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and emotion-focused therapy. Structured intervention programs could include resilience training, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and the promotion of peer support groups within medical schools. These interventions should be integrated into medical school curricula to proactively address their psychological needs.

5 Conclusion

This cross-sectional study demonstrates that greater exposure to childhood trauma is significantly associated with an elevated risk of suicidal ideation among adolescents. Specifically, alexithymia and resilience may function as critical mediating factors in the pathway linking childhood trauma to suicidal ideation. Psychological resilience can be enhanced through targeted interventions targeting its key constituent components, thereby mitigating suicidal ideation among medical students.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Committee of the Anhui Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XG: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. SM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. PL: Resources, Writing – review & editing. WW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XH: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. PW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by Anhui Medical University Quality Engineering Project: “Research on Collaborative Construction of the First, Second, and Third Classrooms for Medical Humanities Education in Local Universities in the Context of New Medicine” (2024xjxm34). Postgraduate Party Building and Ideol ogical and Political Innovation Project of Anhui Medical University (2024yjsdjcxxm11).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the participating medical school for granting permission to conduct this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1675266/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. (2016) 316:2214–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324

2. Sinval J, Oliveira P, Novais F, Almeida CM, and Telles-Correia D. Exploring the impact of depression, anxiety, stress, academic engagement, and dropout intention on medical students’ academic performance: A prospective study. J Affect Disord. (2025) 368:665–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.09.116

3. Seoane HA, Moschetto L, Orliacq F, Orliacq J, Serrano E, Cazenave MI, et al. Sleep disruption in medicine students and its relationship with impaired academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2020) 53:101333. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101333

4. McKerrow I, Carney PA, Caretta-Weyer H, Furnari M, and Miller Juve A. Trends in medical students’ stress, physical, and emotional health throughout training. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1709278. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2019.1709278

5. Wang J, Liu M, Bai J, Chen Y, Xia J, Liang B, et al. Prevalence of common mental disorders among medical students in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1116616. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1116616

6. Krause KJ, Shelley J, Becker A, and Walsh C. Exploring risk factors in suicidal ideation and attempt concept cooccurrence networks. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. (2022) 2022:644–52.

7. Stanton KJ, Denietolis B, Goodwin BJ, and Dvir Y. Childhood trauma and psychosis: an updated review. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2020) 29:115–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2019.08.004

8. Badr HE, Naser J, Al-Zaabi A, Al-Saeedi A, Al-Munefi K, Al-Houli S, et al. Childhood maltreatment: A predictor of mental health problems among adolescents and young adults. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 80:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.011

9. Maydom JK, Blackwell C, and O’Connor DB. Childhood trauma and suicide risk: Investigating the role of adult attachment. J Affect Disord. (2024) 365:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.005

10. John OP and Gross JJ. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J Pers. (2004) 72:1301–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

11. Pape M, Reichrath B, Bottel L, Herpertz S, Kessler H, and Dieris-Hirche J. Alexithymia and internet gaming disorder in the light of depression: A cross-sectional clinical study. Acta Psychol (Amst). (2022) 229:103698. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103698

12. Şenkal İ and Işıklı S. Childhood traumas and attachment style-associated depression symptoms: the mediator role of alexithymia. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. (2015) 26:261–7.

13. Iskric A, Ceniti AK, Bergmans Y, McInerney S, and Rizvi SJ. Alexithymia and self-harm: A review of nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112920. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112920

14. Cerutti R, Zuffianò A, and Spensieri V. The role of difficulty in identifying and describing feelings in non-suicidal self-injury behavior (NSSI): associations with perceived attachment quality, stressful life events, and suicidal ideation. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:318. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00318

15. Kušević Z, Ćusa BV, Babić G, and Marčinko D. Could alexithymia predict suicide attempts - a study of Croatian war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Danub. (2015) 27(4):420–3.

16. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, and Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. (2000) 71:543–62. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

17. Richardson GE. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J Clin Psychol. (2002) 58:307–21. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020

18. Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. (2012) 38:661–71. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs050

19. LeMoult J, Humphreys KL, Tracy A, Hoffmeister JA, Ip E, and Gotlib IH. Meta-analysis: exposure to early life stress and risk for depression in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 59:842–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.10.011

20. Sousa LRM, Leoni PHT, Carvalho RAG, Ventura CAA, Silva A, Reis RK, et al. Resilience, depression and self-efficacy among Brazilian nursing professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cien Saude Colet. (2023) 28:2941–50. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320232810.09852023

21. Liu WJ, Zhou L, Wang XQ, Yang BX, Wang Y, and Jiang JF. Mediating role of resilience in relationship between negative life events and depression among Chinese adolescents. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2019) 33:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2019.10.004

22. Sher L. Resilience as a focus of suicide research and prevention. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2019) 140:169–80. doi: 10.1111/acps.13059

23. Stark L, Seff I, Yu G, Salama M, Wessells M, Allaf C, et al. Correlates of suicide ideation and resilience among native- and foreign-born adolescents in the United States. J Adolesc Health. (2022) 70:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.012

24. Lui SSY, Wong YL, Huang YH, Chau BCL, Cheung ESL, Wong CHY, et al. Childhood trauma, resilience, psychopathology and social functioning in schizophrenia: A network analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. (2024) 101:104211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2024.104211

25. Zhang B, Zhang W, Sun L, Jiang C, Zhou Y, and He K. Relationship between alexithymia, loneliness, resilience and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depression: a multi-center study. BMC Psychiatry. (2023) 23:445. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-04938-y

26. Maack DJ, Tull MT, and Gratz KL. Examining the incremental contribution of behavioral inhibition to generalized anxiety disorder relative to other Axis I disorders and cognitive-emotional vulnerabilities. J Anxiety Disord. (2012) 26:689–95. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.05.005

27. Zhou Y and Miao H. Relationship between pain resilience and pain catastrophizing in older patients after total knee arthroplasty: Chain-mediating effects of cognitive emotion regulation and pain management self-efficacy. Geriatr Nurs. (2024) 59:571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2024.08.011

28. Romano L, Buonomo I, Callea A, and Fiorilli C. Alexithymia in Young people’s academic career: The mediating role of anxiety and resilience. J Genet Psychol. (2019) 180:157–69. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2019.1620675

29. Morice-Ramat A, Goronflot L, and Guihard G. Are alexithymia and empathy predicting factors of the resilience of medical residents in France? Int J Med Educ. (2018) 9:122–8. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5ac6.44ba

30. Favaretto E, Bedani F, Brancati GE, De Berardis D, Giovannini S, Scarcella L, et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J Affect Disord. (2024) 362:406–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.07.011

31. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

32. Sher L and Oquendo MA. Suicide: an overview for clinicians. Med Clin North Am. (2023) 107:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2022.03.008

33. van Ballegooijen W, Rawee J, Palantza C, Miguel C, Harrer M, Cristea I, et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts after direct or indirect psychotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. (2025) 82:31–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.2854

34. Dennis JA, Khan O, Ferriter M, Huband N, Powney MJ, and Duggan C. Psychological interventions for adults who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) 12:Cd007507. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007507.pub2

35. Terock J, Frenzel S, Wittfeld K, Klinger-König J, Janowitz D, Bülow R, et al. Alexithymia is associated with altered cortical thickness networks in the general population. Neuropsychobiology. (2020) 79:233–44. doi: 10.1159/000504983

36. Zakiei A, Ghasemi SR, Gilan NR, Reshadat S, Sharifi K, and Mohammadi O. Mediator role of experiential avoidance in relationship of perceived stress and alexithymia with mental health. East Mediterr Health J. (2017) 23:335–41. doi: 10.26719/2017.23.5.335

37. Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, McLaughlin KA, Wall MM, Grant BF, et al. Childhood maltreatment and the structure of common psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry. (2012) 200:107–15. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.093062

38. McLaughlin KA, Colich NL, Rodman AM, and Weissman DG. Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Med. (2020) 18:96. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01561-6

39. Franco-Rubio L, Puente-Martínez A, and Ubillos-Landa S. Factors associated with recovery during schizophrenia and related disorders: A review of meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. (2024) 267:201–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2024.03.021

40. Martin JB and Pihl RO. The stress-alexithymia hypothesis: theorectical and empirical considerations. Psychother Psychosom. (1985) 43:169–76. doi: 10.1159/000287876

41. Parker JD, Taylor GJ, and Bagby RM. Alexithymia: relationship with ego defense and coping styles. Compr Psychiatry. (1998) 39:91–8. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90084-0

Keywords: childhood trauma, suicidal ideation, alexithymia, resilience, medical students

Citation: Gao X, Mu S, Zhang D, Li P, Wang W, Hu X and Wang P (2025) The association between childhood trauma and suicidal ideation in medical students: the role of alexithymia and resilience. Front. Psychiatry 16:1675266. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1675266

Received: 29 July 2025; Accepted: 18 September 2025;

Published: 09 October 2025.

Edited by:

Liana Romaniuk, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomReviewed by:

Vassilis Martiadis, Asl Napoli 1 Centro, ItalyQiaoling Wang, Yantai Vocational College, China

Copyright © 2025 Gao, Mu, Zhang, Li, Wang, Hu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng Wang, d2FuZ3BlbmdkZXZAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Xiaomei Gao

Xiaomei Gao Siqi Mu

Siqi Mu Daofen Zhang1

Daofen Zhang1 Wanrong Wang

Wanrong Wang Peng Wang

Peng Wang