- Department of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

Background: Fatigue constitutes a highly prevalent symptom within the cancer patient population, exerting a profound and multifaceted impact on their quality of life. Within the specific context of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), a therapeutic modality associated with significant physiological and psychological stressors, the manifestation and determinants of fatigue remain inadequately characterized. The present study was therefore designed to systematically assess the prevalence of fatigue among HSCT recipients and identify key factors influencing its occurrence.

Methods: This cross-sectional study encompassed HSCT recipients treated at our hospital from November 2023 to November 2024. Fatigue levels were assessed using the Revised Piper Fatigue Scale. Data were collected during outpatient follow-up visits, which occurred at least 1 month after HSCT to ensure stabilization of physical and psychological status.

Results: A total of 214 HSCT recipients were enrolled in the analysis. Among them, 88 patients reported fatigue, yielding a prevalence rate of 41.12%. Bivariate correlation analysis revealed statistically significant associations between fatigue and four variables: age (r = 0.530), gender (r = 0.509), per capita monthly household income (r = 0.552), and number of transplantation attempts (r = 0.602), with all correlation coefficients reaching significance at p < 0.05. Further logistic regression analysis confirmed these variables as independent associated factors of fatigue in HSCT recipients: age (OR = 2.410, 95% CI: 2.015–3.104), gender (OR = 2.504, 95% CI: 2.113–2.866), per capita monthly household income (OR = 3.218, 95% CI: 2.830–3.885), and number of transplantation attempts (OR = 3.652, 95% CI: 2.965–4.124), with all predictors demonstrating statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Conclusion: HSCT recipients exhibit a high prevalence of fatigue, with emotional and sensory dimensions emerging as its primary characteristics. These findings underscore the imperative for healthcare practitioners to design and execute targeted interventions grounded in the identified risk factors, thereby effectively alleviating fatigue in this patient population.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) involves the infusion of autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells to reconstitute recipients’ hematopoietic and immune systems (1). As a well-established therapeutic modality, HSCT is widely utilized in managing hematological malignancies, solid tumors, and immunological disorders (2). Since the 1950s, HSCT technology has advanced rapidly, with approximately one million procedures successfully performed globally to date (3). Despite its therapeutic efficacy, HSCT is associated with severe complications that induce significant patient suffering and contribute to persistent, debilitating fatigue—an outcome that substantially impairs quality of life (4, 5). This underscores the urgency of investigating the pathogenesis of post-HSCT complications and optimizing strategies for holistic physical and mental health management to enhance post-transplant survival and quality of life.

Fatigue, a subjective experience characterized by its multifactorial, multidimensional, and nonspecific nature, lacks a universally accepted definition due to incomplete mechanistic understanding (6). In oncology populations, cancer-related fatigue affects up to 40% of patients at diagnosis and persists across the entire disease trajectory, rather than being confined to end stages (7). For HSCT recipients, the procedure exerts profound physical and psychological impacts: studies indicate heightened fatigue scores in emotional and sensory domains, which correlate strongly with prevalent anxiety (8, 9). Anxiety, reported in 44.60–78.15% of HSCT recipients, stems from concerns such as disease recurrence or progression, fear of new malignancies, body image disturbances, financial strain, social isolation, and employment challenges (10–12). These psychological stressors exacerbate emotional and sensory fatigue, further compromising quality of life and hindering recovery. Moreover, fatigue impairs physical function, potentially worsening disease progression and prognosis while delaying post-transplant rehabilitation (13, 14). Given the incomplete characterization of factors influencing fatigue in HSCT recipients, this study aims to investigate the current status of fatigue in this cohort and conduct an in-depth analysis of its determinants. The findings will provide a scientific foundation for developing targeted interventions and nursing strategies to mitigate fatigue in HSCT recipients.

Methods

Ethical consideration

This study adopted a cross-sectional design. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the hospital’s ethics committee (approval no. 20251138), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with ethical standards.

Sample size consideration

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.7. Based on a previous study (15) reporting a fatigue prevalence of 45% in cancer patients, a significance level (α) of 0.05, power (1-β) of 0.90, and an effect size (w) of 0.15, the minimum required sample size was 198. We enrolled 214 patients to account for potential attrition, exceeding the calculated minimum to ensure statistical robustness.

Study population

Participants were patients who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) at our institution between November 2023 and November 2024. Inclusion criteria were (1): receipt of autologous or allogeneic HSCT at our hospital (2); age ≥18 years (to ensure adequate cognitive capacity for informed participation); (3) ≥1 month post-HSCT (to allow stabilization of physical and psychological status, facilitating accurate assessment of post-transplant outcomes); and (4) voluntary consent to participate with signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: (1) disease recurrence or concurrent malignancies (to avoid confounding by complex comorbidities); (2) patients with mental illness or consciousness disorders were excluded to ensure reliable data reporting); and (3) refusal to participate (to uphold patient autonomy).

Data collection

Data were collected during outpatient follow-up visits, which occurred at least 1 month after HSCT to ensure stabilization of physical and psychological status. Demographic and clinical variables were collected, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), diagnosis, educational level, marital status, per capita monthly household income, transplant type, employment status, number of transplantation attempts (The total number of HSCT procedures received by the patient, including primary transplantation (1st attempt) and secondary transplantation (2nd or more attempts) for disease relapse.), and transplant-related complications (Clinically confirmed conditions occurring within 1 month post-HSCT, including infection (bacterial, viral, or fungal), acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD), organ dysfunction (liver, kidney, or cardiac), and severe mucositis).

Fatigue was assessed using the Revised Piper Fatigue Scale (RPFS), a validated instrument revised by Piper et al. (1998) to address the limitations of the original 1990 version (which included 7 dimensions and 82 items, posing high participant burden) (16, 17). The RPFS focuses on current fatigue, comprising 22 items across 4 dimensions: behavioral, affective, sensory, and cognitive. It demonstrates excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.97). Each item is rated on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = no fatigue, 10 = severe fatigue), with total scores calculated as the mean of all items: 1–4 (mild), 5–<7 (moderate), and 7–10 (severe). The Chinese version of the RPFS, validated in HSCT populations (test-retest reliability = 0.98; Cronbach’s α = 0.91), was used (18–20).

Trained investigators conducted face-to-face data collection. Participants received standardized explanations of the study before providing consent. Questionnaires were completed independently, with investigators assisting those unable to do so and verifying data completeness on-site to ensure accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0. Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (normal distribution) or median (interquartile range) (non-normal distribution). Qualitative data were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons used χ² tests or rank-sum tests, as appropriate. Associations between participant characteristics and fatigue were analyzed via Pearson or Spearman correlation. The primary dependent variable was fatigue severity, an ordinal variable classified into mild (1–4), moderate (5–<7), and severe (7–10) based on the Revised Piper Fatigue Scale (RPFS) total score. Variables included in the ordinal logistic regression model were selected based on bivariate correlation results (p < 0.05) and clinical relevance: age, gender, per capita monthly household income, and number of transplantation attempts. The proportional odds assumption for ordinal logistic regression was tested using the Brant test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 256 patients were screened during the study period. Of these, 32 were excluded (18 due to disease recurrence/concurrent malignancies, 7 with mental illness/consciousness disorders, and 7 who refused participation), and 214 eligible patients provided signed informed consent and were included in the final analysis. No participants were excluded due to missing data, as on-site verification ensured questionnaire completeness. Among the included 214 HSCT recipients, 88 (41.12%) patients reported experiencing fatigue. As summarized in Table 1, to address the reviewer's comments, we conducted non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U for binary variables and Kruskal-Wallis H for categorical variables with more than two levels) to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without fatigue. Significant differences were observed in age, gender, per capita monthly household income, and number of transplantation attempts (all p < 0.05). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were noted for body mass index (BMI), disease diagnosis, educational level, marital status, transplant type, employment status, or transplant-related complications (all p > 0.05).

Table 1. The characteristics of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (n=214).

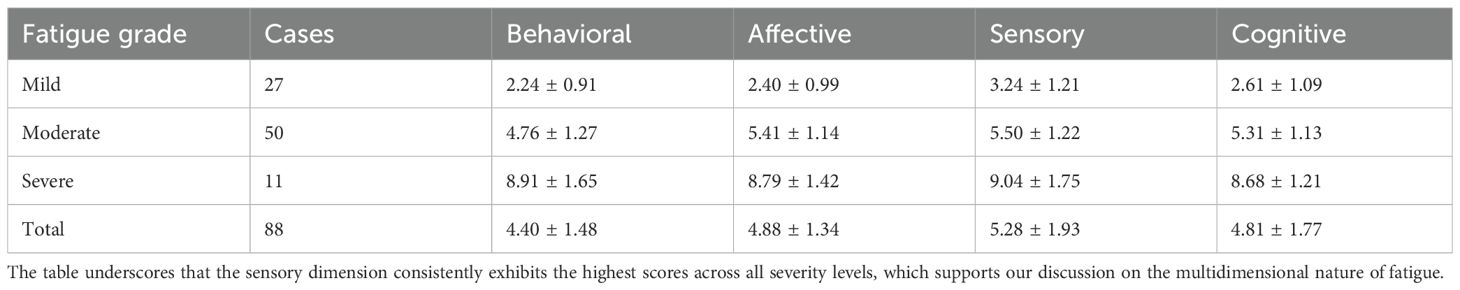

Among the 88 patients with fatigue, the mean fatigue score was 4.79 ± 1.92, with varying severity levels (Table 2). Specifically, 27 patients (30.7%) exhibited mild fatigue, 50 (56.8%) had moderate fatigue, and 11 (12.5%) experienced severe fatigue. Consistent with our initial findings, scores across all four dimensions of the RPFS – behavioral, affective, sensory, and cognitive – demonstrated a clear and significant increase with the escalation of fatigue severity. Notably, the sensory dimension had the highest mean score (5.28 ± 1.93) across all fatigue grades, followed by the affective dimension (4.88 ± 1.34), which aligns with our discussion on the multidimensional nature of fatigue in this population.

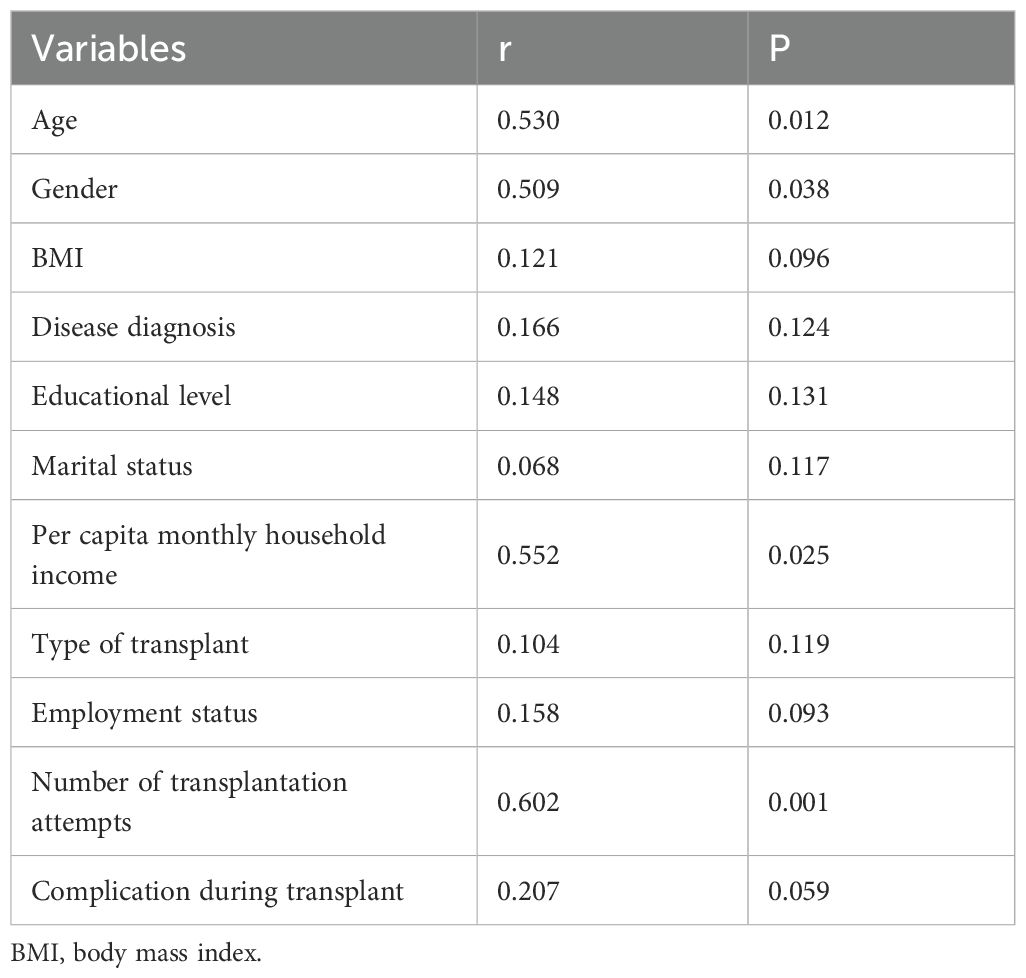

Correlation analyses (Table 3) using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient revealed positive associations between fatigue and age (r = 0.530), gender (r = 0.509), per capita monthly household income (r = 0.552), and number of transplantation attempts (r = 0.602), with all correlations reaching statistical significance (all p < 0.05).

Table 3. Correlation analysis on the fatigue and characteristics of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients.

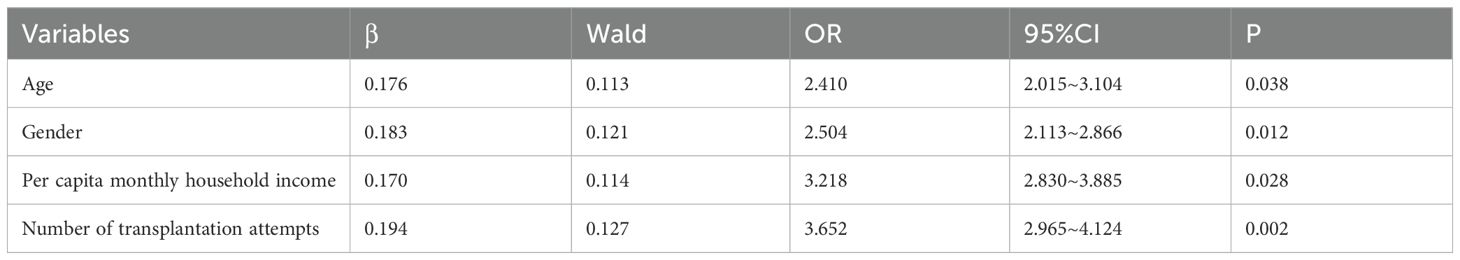

Finally, an ordinal logistic regression analysis (Table 4) identified four independent factors associated with fatigue in HSCT patients: number of transplantation attempts (OR = 3.652, 95% CI: 2.965–4.124), per capita monthly household income (OR = 3.218, 95% CI: 2.830–3.885), gender (OR = 2.504, 95% CI: 2.113–2.866), and age (OR = 2.410, 95% CI: 2.015–3.104), all of which were statistically significant (all p < 0.05). The results indicated no violation of the assumption (χ² = 6.23, p = 0.183), confirming the appropriateness of the model.

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis on the influencing factors of fatigue in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the incidence of fatigue among patients who underwent HSCT was 41.12%, which is consistent with previous related research reports. With the rapid development of the economy and society, there has been a significant improvement in people’s material and spiritual lives, which has alleviated the long-term fatigue levels of HSCT recipients to some extent (21, 22). In recent years, China has gradually strengthened long-term follow-up guidance and comprehensive nursing measures for the long-term prognosis of HSCT recipients, leading to a downward trend in patients’ self-perceived fatigue levels. Meanwhile, medical staff have increasingly paid attention to the issue of fatigue in HSCT recipients, and research on the related factors of fatigue in this patient group has been growing (23). Correspondingly, targeted intervention measures have been gradually implemented, thereby improving patients’ fatigue conditions to a certain extent. Therefore, further in-depth research is still needed to develop a systematic intervention process and long-term management plan for fatigue in HSCT recipients.

At present, the pathophysiological mechanism of fatigue has not been fully elucidated. In clinical practice, drug treatment for fatigue mainly focuses on medications targeting potential causes, and there is still a lack of specific drugs for treating fatigue (24). The data from this study show that among HSCT recipients with fatigue, the proportion of those with moderate fatigue is the highest, while the proportions of those with mild and severe fatigue are relatively low. This result conforms to the general normal distribution rule and also suggests that medical staff should focus on patients with moderate fatigue as key intervention targets, and develop targeted goals, forms, and content of intervention plans for patients with different degrees of fatigue. For example, for patients with moderate fatigue, there is a possibility of reversing the degree of fatigue. If effective interventions can reduce their fatigue level to mild or even no fatigue, it will greatly improve the overall fatigue level of HSCT recipients, thereby enhancing their quality of life and long-term prognosis.

The results of this study indicate that patients who underwent HSCT exhibited relatively high fatigue scores in the emotional and sensory dimensions, a finding that aligns with previous related research. Among the HSCT patient population, a pervasive sense of worry was observed, with an incidence rate as high as 84.16%. The primary concerns included anxiety about disease recurrence or deterioration, fear of new tumor development, apprehensions regarding one’s physical appearance, financial stress, social barriers, and employment issues (25, 26). These factors collectively intensify fatigue in the emotional and sensory domains. Furthermore, while current clinical treatment and nursing practices prioritize physical function recovery and quality of life enhancement, they relatively overlook psychological and social stressors (27), which exacerbate perceived fatigue in emotional and sensory dimensions (28). These findings highlight the need to prioritize psychological support for HSCT recipients, involving medical staff, families, and communities in establishing a tripartite support network (hospital-home-community) to deliver comprehensive psychological care.

This study identified that younger age was associated with a higher probability of fatigue, consistent with previous research. Physiologically, despite their stronger physical recovery capacity, the complex stress response and recovery process induced by HSCT may elicit more pronounced fatigue (29). Additionally, younger patients typically have higher activity demands, which may be unmet due to physical limitations and treatment side effects during transplantation, inducing fatigue. Psychologically, they may experience heightened stress related to future prospects, disease recurrence, and body image, exacerbating fatigue. Their relatively weaker coping abilities and lack of effective strategies also increase susceptibility to fatigue during transplantation challenges (30). Socially, insufficient social support, inadequate family and community resources, and disruptions to life responsibilities and social activities due to transplantation restrictions contribute to combined psychological and physical fatigue (31). In nursing practice, psychological support is paramount: medical staff should conduct regular psychological assessments for younger HSCT recipients to promptly identify and address issues (32). alongside providing professional counseling (individual or group-based) to manage anxiety and depression during transplantation.

This study observed higher fatigue levels in female HSCT recipients, corroborating previous findings and necessitating exploration of underlying causes to inform clinical interventions. Physiologically, inherent structural and hormonal differences between genders may influence HSCT tolerance and recovery. Hormonal fluctuations during menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause affect females’ physical and emotional states, increasing fatigue (33). Post-HSCT, females may face additional physiological challenges such as gynecological inflammation, HPV infections, and cervical lesions, exacerbating fatigue (34). Psychologically, females’ greater emotional sensitivity was associated with higher fatigue levels by impairing sleep and daily functioning (35). Pressure from social roles and family responsibilities may further hinder their adaptation to HSCT. In terms of social support, females may differ in constructing and utilizing support networks; research links inadequate social support to higher fatigue levels. Females’ cautiousness in expressing needs and seeking help, coupled with barriers to accessing support due to multiple family and social roles, intensify fatigue (36). A collaborative hospital-family-community support network is crucial to facilitating female patients’ post-transplant adaptation, reducing fatigue, and improving quality of life and long-term prognosis (37).

This study found that HSCT recipients with lower per capita monthly household income was associated with higher fatigue severity, consistent with previous research (38), warranting further investigation into underlying mechanisms for clinical intervention. Lower-income patients may experience heightened financial stress from treatment costs, income loss due to illness, and declining family financial status. Such stress induces psychological distress (anxiety and depression), impairing sleep and daily functioning and indirectly increasing fatigue (39, 40). Additionally, limited access to social support and medical resources exacerbates fatigue (41). Healthcare providers should develop personalized care plans considering financial constraints, including exploring financial aid options, adjusting treatment schedules to minimize work and daily life disruptions, and providing information on community support resources (42, 43).

This study identified that the number of HSCT procedures significantly influences patient fatigue. Post-transplant relapse is a leading cause of death in HSCT recipients, accounting for 42.9% of fatalities, with secondary transplantation being an effective treatment for relapse (44). In this study, four patients who underwent secondary transplantation exhibited more severe fatigue. Secondary transplantation imposes substantial physical, psychological, and financial burdens on patients and their families, increasing physiological and psychological stress and exacerbating fatigue (45). Thus, healthcare professionals should actively implement relapse prevention measures to reduce secondary transplantation rates. Key factors influencing post-transplant relapse include conditioning regimen intensity, immunosuppression strength and duration for graft-versus-host disease prevention, post-transplant maintenance therapy, and donor lymphocyte infusions (46). However, relapse rates remain high, with many patients experiencing severe fatigue after secondary transplantation. Consequently, the medical team should emphasize comprehensive care and long-term follow-up for these patients to minimize fatigue (47).

Notably, our analysis revealed that certain variables—including BMI, disease diagnosis, educational level, marital status, transplant type, employment status, and transplant-related complications—did not demonstrate significant correlations with fatigue in HSCT recipients. This lack of association warrants careful consideration within the broader context of cancer-related fatigue research. For BMI, these findings align with studies suggesting that the relationship between body mass index and fatigue in hematological populations is often confounded by factors such as treatment-induced metabolic changes and varying activity levels during recovery, which may obscure straightforward correlations (48, 49). Similarly, the absence of association with educational level contrasts with some oncology literature but aligns with research specific to HSCT, where the intensity of treatment experiences may overshadow socioeconomic gradients in fatigue perception (24, 50). The non-significant findings regarding disease diagnosis—with no substantial differences observed between acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and other hematological conditions—suggest that fatigue may operate as a transdiagnostic symptom in this patient population, driven more by the shared physiological and psychological burdens of HSCT itself than by disease-specific characteristics. This interpretation is supported by studies indicating that transplant-related stressors, including conditioning regimens and post-transplant immune dysfunction, often exert a more profound influence on fatigue than underlying malignancy type (51, 52). These non-significant associations serve to highlight the distinctive nature of the four identified independent predictors: age, gender, per capita monthly household income, and number of transplantation attempts. Their consistent significance across both bivariate and regression analyses underscores their particular relevance in shaping fatigue experiences in this cohort. Collectively, these findings emphasize that while fatigue in HSCT recipients arises from a complex interplay of factors, certain variables emerge as particularly critical targets for clinical attention and intervention development.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the single-center design with a relatively small sample size constrains generalizability, as the narrow sampling framework may not reflect the diverse characteristics of HSCT populations across different regional and clinical contexts, potentially introducing sampling or population bias that limits broader applicability. Second, the study's focus on fatigue levels outpatient follow-up period provides only a snapshot view, failing to capture the dynamic nature of post-transplant fatigue—a complex physiological and psychological state shaped by multiple, evolving factors across different recovery stages. This reliance on cross-sectional outpatient follow-up period data impedes a comprehensive understanding of fatigue trajectories, recovery patterns, and their determinants over time. Additionally, variables such as hydration status, albumin levels, nutritional support, physical rehabilitation, and psychological support were not evaluated. These factors may confound the relationships between fatigue and age, gender, or income: for example, lower-income patients may have limited access to nutritional support or psychological counseling, which could independently exacerbate fatigue; younger patients may engage in more physical activity post-transplant, potentially modifying the association between age and fatigue. Future studies should include these variables to disentangle their mediating or moderating effects. We also did not include the MELD score, which is primarily used for assessing liver function and less relevant to our study population with hematological malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. These unmeasured variables represent important gaps that could further contextualize our findings. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to track fatigue periodically throughout the post-HSCT journey while incorporating assessments of these additional predictors, thereby enabling more nuanced identification of fatigue patterns, mechanisms, and targets for personalized interventions.

Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal a relatively high incidence of fatigue among HSCT recipients, with fatigue particularly pronounced in the emotional and sensory dimensions. Statistical analyses identified patient age, gender, economic status, and the number of transplantation procedures as significant associated factors of fatigue severity. In response to these observations, healthcare practitioners should prioritize these influential factors and design targeted nursing interventions tailored to their specific characteristics. Such a strategic approach is critical to effectively mitigating fatigue in this patient population, ultimately contributing to improved overall quality of life. By addressing the multifactorial nature of fatigue through personalized care, clinical practice can better align with the complex needs of HSCT recipients, fostering more favorable post-transplantation outcomes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

In this study, all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study has been reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (approval number: 20251138). Written informed consents had been obtained from all the included patients. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XW: Investigation, Writing – original draft. QX: Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BMI, body mass index; RPFS, Revised Piper Fatigue Scale.

References

1. Penack O, Marchetti M, Aljurf M, Arat M, Bonifazi F, Duarte RF, et al. Prophylaxis and management of graft-versus-host disease after stem-cell transplantation for haematological Malignancies: updated consensus recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet Haematol. (2024) 11:e147–e59. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00342-3

2. Goebel GA, De Assis CS, Cunha LAO, Minafra FG, and Pinto JA. Survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID): A worldwide review of the prognostic variables. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2024) 66:192–209. doi: 10.1007/s12016-024-08993-5

3. Ali H and Bacigalupo A. Update on allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for myelofibrosis: A review of current data and applications on risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. (2024) 99:938–45. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27274

4. Lehrnbecher T, Robinson PD, Ammann RA, Fisher B, Patel P, Phillips R, et al. Guideline for the management of fever and neutropenia in pediatric patients with cancer and hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: 2023 update. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:1774–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02224

5. Kim NV, McErlean G, Yu S, Kerridge I, Greenwood M, and Lourenco RA. Healthcare resource utilization and cost associated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A scoping review. Transplant Cell Ther. (2024) 30:542.e1–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2024.01.084

6. Vanrusselt D, Sleurs C, Arif M, Lemiere J, Verschueren S, and Uyttebroeck A. Biomarkers of fatigue in oncology: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2024) 194:104245. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104245

7. Funke M, Eveslage M, Zschuntzsch J, Hagenacker T, Ruck T, Schubert C, et al. Fatigue and associated factors in myasthenia gravis: a nationwide registry study. J Neurol. (2024) 271:5665–70. doi: 10.1007/s00415-024-12490-2

8. Alshammari B, Alkubati SA, Alrasheeday A, Pasay-An E, Edison JS, Madkhali N, et al. Factors influencing fatigue among patients undergoing hemodialysis: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Libyan J Med. (2024) 19:2301142. doi: 10.1080/19932820.2023.2301142

9. Amonoo HL, Daskalakis E, Wolfe ED, Guo M, Celano CM, Healy BC, et al. A positive psychology intervention in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivors (PATH): A pilot randomized clinical trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. (2024) 22:10–5. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2023.7117

10. Anderson LJ, Paulsen L, Miranda G, Syrjala KL, Graf SA, Chauncey TR, et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for physical function maintenance during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Study protocol. PloS One. (2024) 19:e0302970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302970

11. Trinh JQ, Nilles JD, Ellithi M, Haddadin MM, Maness-Harris L, Gundabolu K, et al. Metabolic syndrome and symptom burden in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivors. Future Oncol. (2024) 18:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14796694.2024.2431476

12. Yang D, Newcomb R, Kavanaugh AR, Khalil D, Greer JA, Chen YB, et al. Protocol for multi-site randomized trial of inpatient palliative care for patients with hematologic Malignancies undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Contemp Clin Trials. (2024) 138:107460. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2024.107460

13. Montgomery KE, Raybin JL, Powers K, Hellsten M, Murray P, and Ward J. High symptom burden predicts poorer quality of life among children and adolescents receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Cancer Nurs. (2024) 24:55–62. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000001337

14. Fu JB and Morishita S. Inpatient rehabilitation of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: managing challenging impairments and medical fragility. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2024) 103:S46–51. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000002408

15. Guo X and Chen Z. Current status of cancer-related fatigue in patients with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy and its correlation with quality of life. China Pharm Herald. (2024) 21:90–2.

16. Piper BF. Piper fatigue scale available for clinical testing. Oncol Nurs Forum. (1990) 17:661–2.

17. Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, Weiss MC, Slaughter RE, and Paul SM. The revised Piper Fatigue Scale: psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. (1998) 25:677–84.

18. So WK, Dodgson J, and Tai JW. Fatigue and quality of life among Chinese patients with hematologic Malignancy after bone marrow transplantation. Cancer Nurs. (2003) 26:211–9. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200306000-00006

19. Qiao X, Zhan Y, Li L, and Cui R. Development and validation of a nomogram to estimate fatigue probability in hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. (2024) 46:2396460. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2024.2396460

20. Xin X, Huang L, Pan Q, Zhang J, and Hu W. The effect of self-designed metabolic equivalent exercises on cancer-related fatigue in patients with gastric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. (2024) 13:e7085. doi: 10.1002/cam4.7085

21. Di Francesco G, Cieri F, Esposito R, Sciarra P, Ballarini V, Di Ianni M, et al. Fatigue as mediator factor in PTSD-symptoms after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:6–9. doi: 10.3390/jcm12082756

22. Ullrich CK, Baker KK, Carpenter PA, Flowers ME, Gooley T, Stevens S, et al. Fatigue in hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: correlates, care team communication, and patient-identified mitigation strategies. Transplant Cell Ther. (2023) 29:200.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.11.030

23. Liu S, Xing J, and Dong S. Research progress on influencing factors and intervention of fatigue in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. China Nurs Manage. (2019) 24:5–9.

24. Noyan S, Gundogdu F, and Bozdag SC. The level of fatigue, insomnia, depression, anxiety, stress, and the relationship between these symptoms following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. (2023) 31:244. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07703-9

25. Yanling S, Pu Y, Duorong X, Zhiyong Z, Ting X, Wenjun X, et al. Psychological states and needs among post-allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivors. Cancer Med. (2023) 12:16637–48. doi: 10.1002/cam4.6280

26. Almeida ACP, Azevedo VD, Alves TRM, Santos VEP, Silva G, and Azevedo IC. Common mental disorders in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: a scoping review. Rev Bras Enferm. (2023) 77:e20220581. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2022-0581

27. Nakano K, Fujii S, Fujioka A, Kimura K, Abe Y, Abe M, et al. A nursing pre-transplant intervention to reduce patients' Uncertainty about allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cell Ther. (2024) 7:14–24. doi: 10.31547/bct-2023-013

28. Dennett AM, Porter J, Ting SB, and Taylor NF. Prehabilitation to improve outcomes afteR Autologous sTem cEll transplantation (PIRATE): A pilot randomised controlled trial protocol. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0277760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277760

29. Hoogland AI, Gonzalez BD, Park JY, Small BJ, Sutton SK, Pidala JA, et al. Associations of germline genetic variants with depression and fatigue among hematologic cancer patients treated with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Psychosom Med. (2023) 85:813–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000001251

30. Boberg E, Kadri N, Hagey DW, Schwieler L, El Andaloussi S, Erhardt S, et al. Cognitive impairments correlate with increased central nervous system immune activation after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. (2023) 37:888–900. doi: 10.1038/s41375-023-01840-0

31. Morais NI, Palhares LC, Miranda EC, Lima CS, De Souza CA, and Vigorito AC. Effects of a physiotherapeutic protocol in cardiorespiratory, muscle strength, aerobic capacity and quality of life after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. (2023) 45:154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2021.08.003

32. Pirk F. Apparatus for examination of the colon by double contrast. Cesk Radiol. (1982) 36:274–6.

33. Huang Z, Min S, and Jing Y. Characteristics and influencing factors of cancer-related fatigue during chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Chin J Cancer Prev Control. (2023) 11:1513–8.

34. Zhang X and Perry RJ. Metabolic underpinnings of cancer-related fatigue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2024) 326:E290–307. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00378.2023

35. Ee C, Kay S, Reynolds A, Lovato N, Lacey J, and Koczwara B. Lifestyle and integrative oncology interventions for cancer-related fatigue and sleep disturbances. Maturitas. (2024) 187:108056. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2024.108056

36. Bower JE, Lacchetti C, Alici Y, Barton DL, Bruner D, Canin BE, et al. Management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: ASCO-society for integrative oncology guideline update. J Clin Oncol. (2024) 42:2456–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.24.00541

37. Li J, Liu S, and Hu W. Current status of fatigue in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and its influencing factors. Nurs Res. (2024) 38:67–74.

38. Liu D, Weng J, and Xi K. Correlation study on cancer-related fatigue, quality of life and pain severity in cancer patients. Int Nurs Sci. (2023) 10:111–6.

39. Schmidt ME, Maurer T, Behrens S, Seibold P, Obi N, Chang-Claude J, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: Towards a more targeted approach based on classification by biomarkers and psychological factors. Int J Cancer. (2024) 154:1011–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.34791

40. Keane KF, Wickstrom J, Livinski AA, Blumhorst C, Wang TF, and Saligan LN. The definitions, assessment, and dimensions of cancer-related fatigue: A scoping review. Support Care Cancer. (2024) 32:457. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08615-y

41. Huang J, Tian Y, and Huang M. Relationship between symptom interference and cancer-related fatigue in patients with cancer radiotherapy and chemotherapy: Mediating and regulating effects of resilience levels. Modern Prev Med. (2024) 51:10–4.

42. Forbes C, Tanner S, Engstrom T, Lee WR, Patel D, Walker R, et al. Patient reported fatigue among adolescent and young adult cancer patients compared to non-cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. (2024) 13:242–50. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2023.0094

43. Mi L, Yu J, and Wang Z. Influencing factors and nursing analysis of psychological status and cancer-related fatigue in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing chemotherapy. Integrated Traditional Chin Western Med. (2024) 10:127–9.

44. Li J, Xu S, and Hu W. Current status of fatigue in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and its influencing factors. Nurs Res. (2024) 38:67–74.

45. Liu H, Li C, and Huang H. Effect of comprehensive exercise with aerobic exercise as the core on fatigue intervention in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients:Meta analysis. Evidence-Based Nurs. (2023) 9:1331–6.

46. Xu C, Ye M, and Cao M. Review of the range of symptom clusters after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. China J Modern Nurs. (2024) 30:678–83.

47. Shang M, Chen P, and Feng D. Quality evaluation and content analysis of fatigue related management guidelines for cancer patients. Chongqing Med Sci. (2023) 52:6–9.

48. Janssen L, Blijlevens NMA, Drissen M, Bakker EA, Nuijten MAH, Janssen J, et al. Fatigue in chronic myeloid leukemia patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy: predictors and the relationship with physical activity. Haematologica. (2021) 106:1876–82. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.247767

49. Mohanraj L, Sargent L, Elswick RK Jr., Toor A, and Swift-Scanlan T. Factors affecting quality of life in patients receiving autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Nurs. (2022) 45:E552–E9. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000990

50. Abdalrahman OA, Othman EH, Khalifeh AH, and Suleiman KH. Fatigue among post-hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients in Jordan: prevalence and associated factors. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 30:7679–87. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07186-0

51. Karst JS, Hoag JA, Anderson LJ, Schmidt DJ, Schroedl RL, and Bingen KM. Evaluation of fatigue and related factors in survivors of pediatric cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J Child Health Care. (2022) 26:383–93. doi: 10.1177/13674935211014748

Keywords: fatigue, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, assessment, nursing, care

Citation: Wu X and Xu Q (2025) Cancer-related fatigue in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a cross-sectional study on prevalence and influencing factors. Front. Psychiatry 16:1681573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1681573

Received: 07 August 2025; Accepted: 07 November 2025; Revised: 07 November 2025;

Published: 08 December 2025.

Edited by:

Francisco Fernández Avilés, Hospital Clínic of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Semra Bulbuloglu, Istanbul Aydın University, TürkiyeMeryem Kocaslan Toran, Üsküdar University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Wu and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiufang Xu, ZTdyNXQ1QHNpbmEuY29t

Xia Wu

Xia Wu Qiufang Xu

Qiufang Xu