- 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 2Global Health Working Group, Institute of Medical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Informatics, Martin-Luther University, Halle (Saale), Germany

- 3Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 4Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 5Department of Gynecology, Martin-Luther-University, Halle (Saale), Germany

Background: While psychosocial services are known to improve treatment adherence and quality of life for cancer patients by mitigating anxiety and depression, evidence from Ethiopia is limited. A recent trial introduced integrated psychosocial interventions, including counseling, group discussions, educational materials, and home visits, into routine care. The present study explores barriers and facilitators affecting psychosocial service provision in selected Ethiopian hospitals.

Method: A qualitative study was conducted at six hospitals across four regions of Ethiopia, where psychosocial support had been introduced and provided to patients with cancer. Data were collected through in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with patients diagnosed with breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer; as well as key informant interviews (KIIs) with healthcare professionals, including oncologists, gynecologists, surgeons, nurses, and health extension workers. All interviews were transcribed, translated and reviewed for completeness. To enhance data familiarity, transcripts and audio recordings were reviewed multiple times. NVivo software was used for data management and organization. Data was coded inductively while predefined themes are introduced deductively, followed by thematic analysis to identify key patterns and insights.

Result: Barriers to psychosocial support (PSS) in cancer care include limited awareness of its importance, as treatment is often considered to be purely medical. Although home visits are common in maternal health, in cancer care, they face resistance due to unfamiliarity. Disclosure challenges also persist, with providers avoiding sensitive conversations, leaving patients under-informed. Hospital leadership tends to prioritize physical care over PSS. However, survivor stories enhance patient reassurance and openness; travel reimbursements and refreshments facilitate patient participation and communication, and routine supervision of PSS activities supports provider effectiveness in PSS provision.

Conclusion: Integrating PSS into routine cancer care requires a shift in the mindset of patients, providers, and leadership, recognizing PSS as an essential component of comprehensive cancer care. Raising awareness about home visits and strengthening provider skills through targeted training on disclosure can improve patient engagement and quality of care.

Background

Cancer diagnosis and treatment often disrupt psychological and social well-being of patients, contributing to mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression and adjustment disorders (1, 2). These mental health conditions can compromise treatment adherence, diminish quality of life, and worsen clinical outcomes of patients with cancer; hence, addressing the psychosocial dimensions of cancer care is crucial to enhancing patient-centered outcomes (3).

Psychosocial support, encompassing counseling, education, coping strategies, and support groups, is increasingly recognized as a core component of oncology care in high-income countries (4), where it is routinely embedded within multidisciplinary treatment frameworks. However, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Ethiopia, such integration remains limited (5). Structural constraints, workforce shortages, and low awareness among both providers and patients hinder the availability and uptake of psychosocial services in these settings (6), with the absence of standardized service models and limited institutional support further complicating these challenges (7).

In Ethiopia, oncology services are largely centralized, and psychosocial care is rarely incorporated into routine service in cancer care (8). While isolated initiatives, such as breast cancer support groups, have demonstrated potential to foster emotional resilience and reduce stigma (9), these efforts often lack systematic evaluation. Despite the growing recognition of the importance of psychosocial support, little is known about how healthcare providers in Ethiopia navigate the practical challenges of implementing such services in resource-constrained settings. To address this gap, our previous trial investigated the implementation of psychosocial services using a Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBCC) model, incorporating counseling, informational brochures provision, support group discussions, audiovisual materials, and home visits, delivered across six hospitals to patients with breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancers (10).

The effects of the service provision on anxiety, depression, quality of life, and treatment adherence were evaluated. However, several barriers emerged, hindering the effective provision of these services. Therefore, as a continuation of the prior trial, the present study aims to explore the facilitators and barriers that hinder the provision of psychosocial services in the implementation hospitals. Identification of these factors will enhance the effective integration of these services by offering a context-specific framework for integrating psychosocial services into routine cancer care, contributing actionable insights for policy, training, and service design, ultimately enhancing patient health outcomes and quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study setting

This study was conducted at six hospitals that provide cancer treatment services and had participated in the psychosocial service provision initiative, located in four regions of Ethiopia: Southern Ethiopia, Sidama, Central Ethiopia, and Oromia. Two hospitals are located in urban settings: Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital (Addis Ababa) and Adama Hospital Medical College (Adama, southeast Ethiopia). The other four hospitals are located in semi-urban areas: Butajira General Hospital (Central Ethiopia), Nigist Eleni Mohammed Memorial Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (Central Ethiopia), St. Luke’s Catholic Hospital and College of Nursing and Midwifery (Southwest), and Assela Teaching and Referral Hospital (South-central Ethiopia).

Study design

A qualitative exploratory design was employed as a continuation of a larger cluster randomized controlled trial that integrated psychosocial service packages into routine cancer care. This follow-up qualitative study aimed to identify barriers and facilitators influencing psychosocial service provision across the six implementation hospitals involved in the prior trial.

Psychosocial service intervention

Psychosocial services, including counseling, informational brochures, audiovisual materials (such as survivor stories and educational videos), support group discussions, and periodic home visits, were provided to patients diagnosed with cancer, following comprehensive training for health professionals. Nurses and health extension workers were key implementers: nurses led counseling sessions, organized support group discussions, and distributed informational brochures, while health extension workers conducted home visits. The services were delivered as a package for six months at the selected health facilities, with weekly supervision to support providers.

Data collection and procedures

This study employed a hybrid inductive–deductive approach, which influenced the design of the interview guides and the overall data collection strategy. Deductive elements were guided by the study’s conceptual framework and existing literature on barriers and facilitators to psychosocial service provision in low-resource settings. These informed the development of core questions aligned with predefined categories such as “barriers and facilitators”. Simultaneously, the guides were designed to offer flexibility for participants to introduce emergent or unexpected insights, supporting inductive exploration. This dual approach ensured that data collection was both theory-informed and receptive to emerging perspectives.

Data were collected between August and September 2024, after the provision of the psychosocial service. The Principal Investigator (PI), fluent in Amharic and a trained facilitator fluent in both Amharic and Affan Oromo, conducted key informant interviews using tailored guides for each participant group. Interviews included thirteen (13) nurses who delivered PSS, four (4) healthcare extension workers who conducted home visits, and five (5) medical professionals (oncologists, general surgeons, and gynecologists) who were involved in the provision of PSS. Key informant interviews were conducted at healthcare facilities and offices. In-depth interviews were held with seven (7) patients who had received various PSS components, and were conducted either at healthcare facilities or participants’ homes, ensuring privacy and confidentiality. A focus group discussion was also conducted at a healthcare facility. All interviews and discussions lasted 20 to 100 minutes, and were voice-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English.

Data analysis

Data analysis employed a hybrid thematic approach that combined deductive and inductive approaches, as outlined by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (11). Analysis was captured through memo writing by the researchers and subsequently discussed within the team. Multiple reviews of transcripts and voice records were conducted to ensure familiarization with the data. All transcripts were imported into NVivo software (version 15) for qualitative data analysis and assistance with data organization. To ensure consistency and reliability in the coding process, two researchers independently coded a subset of the transcripts. Inter-rater reliability was assessed, with iterative rounds of coding and discussion to reconcile discrepancies and refine the coding scheme. Predefined themes, “barriers” and “facilitators”, were introduced deductively based on the research objectives and existing literature, providing a structural framework for organizing the data. Within these overarching categories, inductive coding was used to allow subthemes to emerge naturally from participants’ narratives. This approach enabled the research team to remain grounded in the data while also engaging with theoretical constructs relevant to the study. The decision to adopt a hybrid approach was driven by the need to both validate known challenges in psychosocial service delivery and uncover context-specific insights that may not be captured in existing frameworks. This strategy enhanced the study’s methodological rigor by ensuring both analytical depth and contextual sensitivity (12, 13). The analysis followed the steps of thematic analysis described in Braun and Clark (14) for qualitative data analysis. Data reporting followed COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) (15).

Trustworthiness

All interviews were recorded to ensure credibility and enable precise capture of participant responses (16, 17). Probing and clarification techniques were employed to enhance the trustworthiness of the data. An audit trail was maintained through systematic organization of the data and iterative refinement of the codebook (18). Dependability and confirmability were supported by consistent documentation of analytic decisions and efforts to minimize researcher bias (16). Transferability was maintained through purposive sampling, enabling meaningful interpretation across similar settings (17).

Reflexivity and positionality

During interviews and focus group discussions with cancer patients, the researcher engaged in in-depth conversations about patients’ experiences throughout their cancer treatment journey and daily lives. Due to the researcher’s empathetic nature, it was sometimes challenging to continue conversations when sensitive topics arose and, breaks were sometimes necessary during interviews to manage emotions. To mitigate this, we employed reflexive practices throughout data collection and analysis, including regular debriefing with a research assistant and external experts not involved in data collection. In addition, the researcher holds strong views on women’s rights and strongly opposes the societal expectations placed on women in Ethiopia. For example, when healthcare extension workers explained that they counseled women with cervical cancer to continue to meet their husbands’ sexual needs, despite their chronic condition, it triggered difficult emotions. Hence, the researcher had to be mindful of certain reactions in these situations. With the continuous support of an expert research assistant and experts who were not involved in data collection, we were able to reflect on the researcher’s positions and bring this perspective into the analysis in a scientific manner (19).

Ethical considerations

Participants provided written informed consent following a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures. Furthermore, to protect the confidentiality and privacy of the study participants, we pseudonymized characters that might identify the personal traits of individuals. Ethical approval for the present study was obtained from the School of Public Health, Addis Ababa University, and the institutional review board of Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, with protocol number 071/24/SPH.

Results

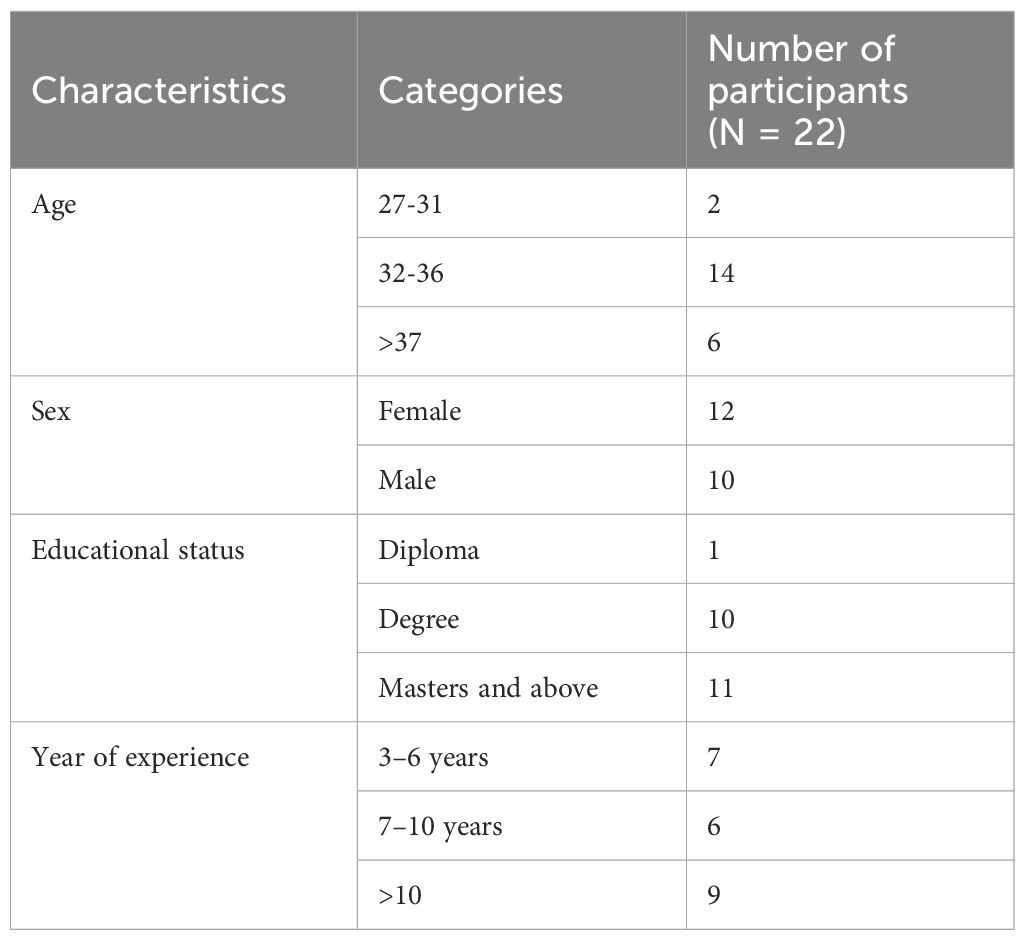

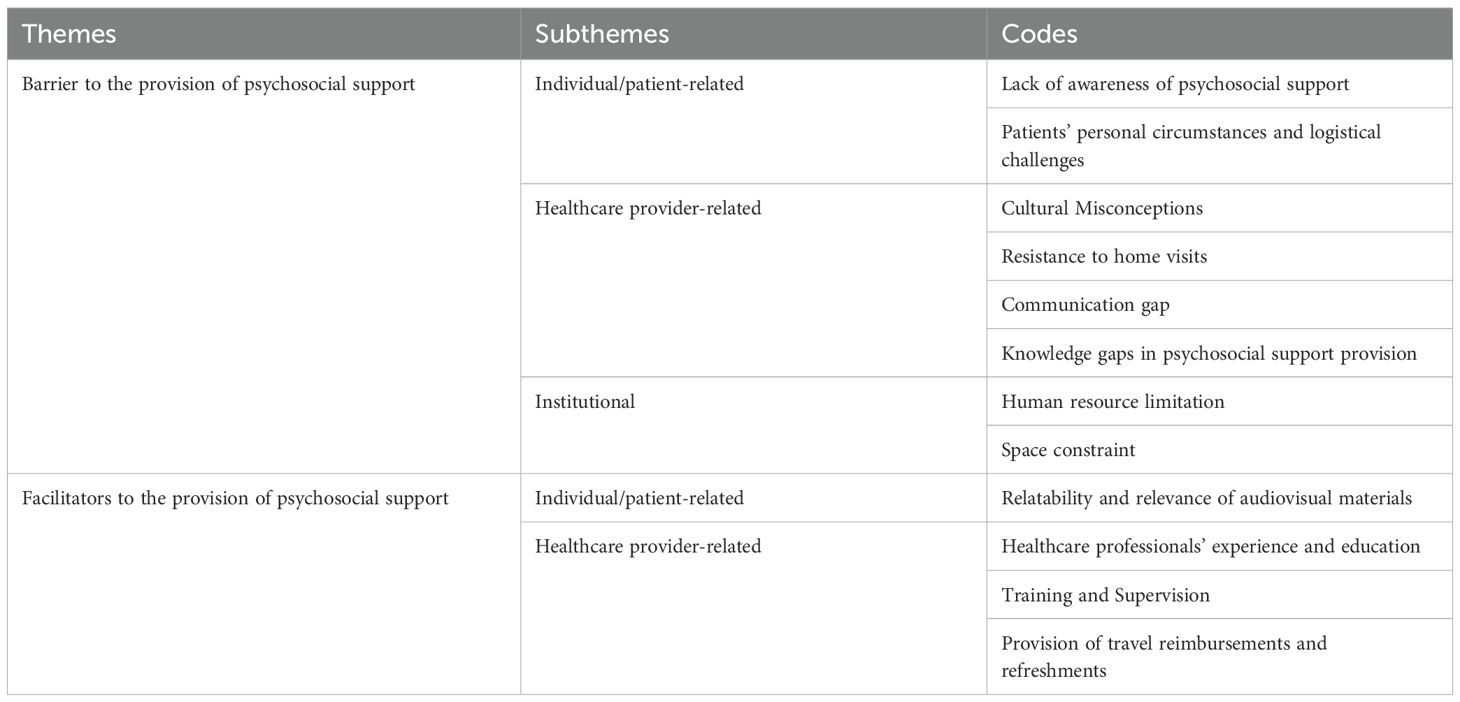

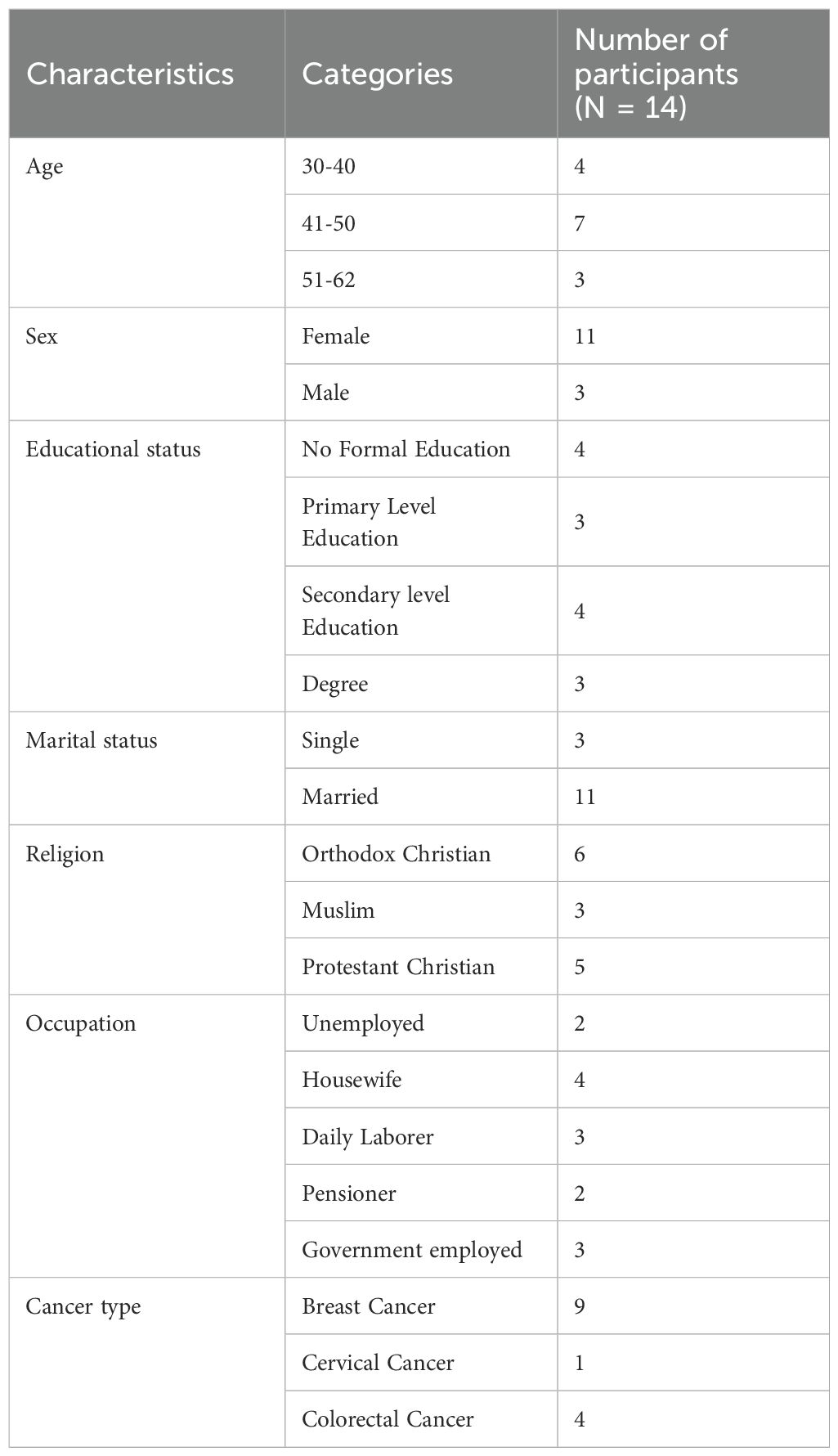

A total of 22 participants were involved in the Key Informant Interviews. Most of the participants had an educational background of at least a degree, with over 10 years of work experience (Table 1). Among the participants involved in the In-depth Interviews and Focus Group Discussion, the majority were breast cancer patients with an educational background of primary school level or highers (Table 2). Barriers and facilitators to the provision of psychosocial service were identified at different levels (Table 3).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants in the in-depth interviews and focus group discussion.

Barriers to the provision of psychosocial services

Lack of awareness about psychosocial support

Because of limited awareness of the importance of psychosocial support, cancer care is often considered to involve only medical treatments, such as chemotherapy and surgery. Consequently, the value of psychosocial support is frequently overlooked. Healthcare professionals reported that they consider medical treatments to be the sole valid approach to cancer care, while many patients were either unaware of available counseling services or believed that they were not essential.

“Due to a lack of awareness about the importance of counseling, patients are focused on completing their treatment and rushing back home, avoiding the services we provide.” (KII01, Oncology nurse)

Hospital administrations also prioritize physical treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer care over psychosocial services. Due to limited awareness of its importance, psychosocial support is frequently undervalued, rarely promoted and seen as an additional task rather than an integral part of cancer care. As a result, support activities such as group discussions are often overlooked or poorly scheduled, frequently taking place during lunch hours or other inconvenient times, placing added strain on staff and disrupting established routines.

“There is a lack of awareness among hospital management about the importance of psychosocial support. They think psychosocial support provision is an empty promise because they are too busy trying to fulfil the physical treatment needs.” (KII19, Oncologist)

“The discussions were held at lunchtime, which interfered with our routines. We had to get back to work immediately. We were often told by management to hurry up and finish quickly so that our main work wouldn’t be disrupted.” (KII02, Oncology nurse)

“Not everyone knows about the availability of such support in this setting. Several patients might have used the supportive discussions” (FGD, Colorectal cancer patient)

Professional misunderstandings regarding the purpose and scope of psychosocial support, such as counseling, have led some professionals to perceive it as an administrative duty rather than a meaningful approach to addressing patients’ emotional and psychological needs, which further contributes to its marginalization. As a result, some healthcare providers reduce psychosocial support to casual conversation, overlooking its clinical significance in comprehensive care.

“We met them because we were conducting a study at the time. We just spoke with them briefly when they visited.” (KII03, Oncology nurse)

“There is not much change we can bring by only talking if it is not backed by clinical management and treatment.” (KII16, Gynecologist)

Cultural misconceptions

Cancer is often viewed as a death sentence, shaped by limited awareness and past experiences. As a result, families tend to avoid discussing cancer or the diagnosis. Cultural misconception further discourages open dialogue, especially in semi-urban areas, where norms dictate who may speak about serious illnesses and how.

In such settings, as part of psychosocial support provision, children were sometimes expected to explain cancer-related information to their illiterate parents using brochures, but this proved difficult and was often not done.

“Despite the brochure being very helpful in explaining what cancer is and the side effects of treatments, in our culture, children often feel afraid to discuss serious matters like cancer with their parents. As a result, children did not read or discuss the informative materials with their parents.” (KII05, BSc Nurse)

Furthermore, cultural conditioning influences how men and women experience and process emotions, and affects behavior in various settings, including healthcare environments. Healthcare providers observed that women were not only more present but also more engaged during the support group discussions than men. Several factors were suggested to explain this: 1) women tend to be more sociable and open to sharing their experiences; and 2) many women expressed that their voices were not heard at home, making the group discussions a valuable space for emotional expression.

“Women were active and participated more than the men. They were sociable, laughing, sharing their experiences, and appeared to be happier. The discussion felt as lively and engaging as conversations during coffee ceremonies.” (KII13, MSc nurse)

Nurses also noted that group discussions became an emotional outlet for women participating in the study, especially those dealing with cervical cancer. They expressed feelings of embarrassment and isolation within their homes due to the symptoms of their illness, such as foul-smelling vaginal discharge, and the discussions provided them with a rare chance to voice these concerns in a supportive environment.

“Women with cervical cancer told me they felt embarrassed around their husbands due to their symptoms, because of the foul-smelling discharge. At home, they felt like their concerns were unheard, while the men’s issues are acknowledged and often amplified. In contrast, during group discussions, they found relief and communicated openly, expressing their experiences in a supportive environment.” (KII18, BSc nurse)

Resistance to home visits

Home visits play a crucial role in psychosocial support because they address patients’ needs within the comfort of a familiar environment. While patients are generally accustomed to home visits for maternal and child healthcare services, the concept of home visitations remains unfamiliar for chronic conditions such as cancer. This lack of familiarity often leads to confusion about the purpose of the visits and, in some cases, unrealistic expectations such as expecting financial aid.

Furthermore, due to the stigma associated with their illness, and because they do not want their name to be associated with the disease, some patients refused home visits even after completing medical treatment. Despite assurances of confidentiality, they consistently refused to be contacted by health extension workers (HEW) or other health professionals regarding their cancer condition. This reluctance may reflect a lack of trust in the healthcare providers’ ability to safeguard their privacy and maintain discretion.

“Because psychosocial support is a new concept for many, there was initial resistance towards NCD home visits. Patients often expected financial aid rather than medical support, leading to challenges in establishing the purpose of the visits.” (KII14, Health Extension Worker)

“Some patients insisted on avoiding any contact, determined to keep their cancer diagnosis private, even after recovery. They were afraid of breaches of confidentiality and prioritized their privacy above all else.” (KII09, BSc nurse)

Despite the fact that some patients were reluctant to accept home visits, HEWs do play a pivotal role in delivering this essential service. However, their ability to provide effective home-visit care is frequently hindered by logistical challenges, including long travel distances, inaccurate patient addresses, and limited contact details. Although HEWs reside within the community they serve and possess contextual familiarity, coverage gaps persist. In certain settings, patients live at addresses that fall beyond the urban HEWs’ designated catchment zones, while some rural HEWs had to discontinue their roles due to personal circumstances. Consequently, patients in these areas were left without adequate follow-up care.

“Locating patients’ houses was difficult. There were occasions where they pointed me in one direction, saying it was nearby, but it turned out to be far away. Even after searching for a few days, I was unable to find the house.” (KII14, Health Extension Worker)

Patients’ personal circumstances and logistical challenges

Patients have expressed that the severity of their disease takes an emotional and physical toll on them, which, along with their social responsibilities and work commitments, often makes it challenging to attend psychosocial support activities, especially group discussion sessions. These factors can make it difficult for them to prioritize participation in these sessions, since they are focused on managing their health while also juggling their daily routines and social responsibilities. Healthcare professionals have also mentioned that patients’ individual circumstances often hinder their participation in group discussion sessions.

“Personal circumstances, whether due to illness or social obligations like visiting family or attending social gatherings, can make attending support group discussions difficult.” (IDI04, Breast cancer patient)

“I have a young child who is handicapped and entirely dependent on me, as I am her sole caregiver, which makes my participation in the discussions difficult!” (FGD, cervical cancer patient)

“Some individuals were unable to attend due to their severe illness or because they went to other places for treatment or because they were visiting their children.” (KII09, BSc nurse)

Healthcare providers have also highlighted that irregular attendance, patients leaving sessions early, and lack of punctuality among patients disrupt the continuity of group discussion sessions, making it challenging to create a cohesive environment. Patients arriving late or missing sessions interrupts the flow of the discussions, reducing their effectiveness and the overall benefits of the support. Healthcare providers also face challenges as these disruptions interfere with their primary duties in busy outpatient departments, creating a conflict between their routine responsibilities and providing psychosocial support.

“Some patients missed sessions, while late arrivals disrupted group discussion sessions; and, punctuality issues clashed with our work, as we needed to return to other responsibilities” (KII02, Oncology nurse)

Irregular attendance and lack of punctuality may be due to transportation issues and challenges related to the unique complexities of rural areas, which create significant barriers that often discourage patients from attending psychosocial support sessions.

“The reason why they don’t come after saying they will is because of the issue of transportation, so if we schedule 10 people, 6 might come.” (KII03, Oncology nurse)

Communication gap

Effective communication is crucial in cancer care, because it facilitates timely decision making and more personalized patient support. Yet, delays in essential services such as radiotherapy, combined with poor communication, often leave patients unaware of alternative treatment options. This can lead to missed chances for medical intervention and disease progression that could have been prevented. Psychosocial support, including counseling about treatment choices, is frequently neglected, further contributing to patient frustration and mistrust in the system.

“I worried about delaying radiation, but after years of waiting, I considered private care. By then, three doctors told me it was too late, and the treatment wouldn’t help. I wish I had been told earlier! If I were advised about my options, I would’ve started radiation right after chemotherapy and sought private care.” (IDI01, Breast cancer patient)

Furthermore, the inability of healthcare providers to communicate in patients’ native languages, especially in referral settings, poses a significant challenge. Language barriers often lead to miscommunication, with crucial details lost in translation, leaving patients confused and unsupported throughout their cancer treatment journey. This dissatisfaction affects the quality of psychosocial support, hindering the ability of healthcare providers to address serious issues effectively and empathetically.

“I am not fluent in Afan Oromo, which hinders me from transferring information and reassuring patients. When I try to talk in Afan Oromo, it seems like I am joking or not serious, which is a huge barrier during counseling and prevents me from transmitting my message.” (KII13, MSc nurse)

Clear communication is vital to effective psychosocial support in cancer care. However, cultural norms, family pressures, and professional hesitancy around disclosure hinder open dialogue, limiting patients’ ability to cope with their cancer diagnosis and treatment. Despite training in psychosocial communication, many nurses default to routine counseling and avoid disclosing cancer diagnoses, often viewing it as outside of their professional role. This creates a significant communication gap, leaving patients uninformed about their condition, treatment expectations, and potential side effects, even while undergoing care.

“First and foremost, it is not advisable for nurses to disclose a diagnosis to the patient, but instead this should be done by the diagnosing physician; because they are the ones diagnosing the disease and have enough knowledge about the patient’s condition.” (KII02, Oncology nurse)

Although families play a crucial role in cancer care, their influence also often complicates the cancer diagnosis disclosure process. Caregivers frequently request that healthcare providers withhold diagnoses, believing that patients are too fragile to handle the emotional impact of disclosure. By restricting open discussions, patients are denied essential information about their diagnosis, treatment options, and the emotional support they need. Furthermore, healthcare providers sometimes face institutional directives to respect caregivers’ wishes regarding disclosure. Physicians often justify these decisions as part of “individualized care” for cancer treatment, where the approach to disclosure varies depending on patient and caregiver preferences. While this approach aims to prioritize patient and caregiver comfort, it frequently leads to a lack of transparency that undermines the effectiveness of psychosocial support initiatives.

“Families insist we hide the diagnosis, fearing the patient can’t handle the news. I often comply, afraid of worsening their condition if I go against their wishes.” (KII02, Oncology nurse)

“Some patients complete their treatment without even knowing their diagnosis. We have tried discussing this issue with the physician. We were told that cancer care is individualized care, and it’s not like other diseases. It varies for each individual case, and it can be very challenging. Because of that, if the family requests us not to inform the patient, we comply with that.” (KII01, Oncology nurse)

Knowledge gap in psychosocial support provision

Training in the provision of psychosocial support was generally well-received; however, some healthcare workers felt that training sessions lacked sufficient practical guidance, particularly with respect to counseling techniques. Although training covered a broad range of topics, a common criticism was that it did not offer enough detailed instruction on how to counsel patients.

“We were trained the most on the theoretical part; we did not have practical sessions with patients while receiving training on counseling.” (KII21, MSc nurse)

Healthcare providers often felt unequipped to address complex inquiries from patients, particularly health extension workers, who frequently encounter questions that exceed their training, such as survival times, treatment effectiveness, and nutritional advice. Lacking the necessary expertise, they are often left unable to provide the kind of comprehensive answers that patients desperately seek.

“When I go for a home visit, they ask about their chances of survival … I struggle to respond to that because I don’t have the knowledge to answer such inquiries.” (KII08, Health Extension Worker)

Nutrition is another critical area where healthcare providers feel unprepared to give advice. Patients frequently seek dietary advice, yet providers struggle to offer clear, evidence-based recommendations.

“They ask mostly about the recommended diet, which is important. We used to tell them what we know, but they wanted strong confirmation.” (KII03, Oncology Nurse)

Married women with cancer often face additional challenges related to sexual intimacy. Cervical cancer patients, in particular, report frustrations stemming from their husbands’ lack of understanding and continued expectations for intimacy despite the physical and emotional toll of this illness. Health extension workers frequently encounter such concerns during home visits. In many cases, health extension workers offer advice based on personal beliefs rather than evidence-based, knowledgeable guidance, emphasizing the preservation of marital relationships over patient well-being. Broader societal expectations compound the challenges faced by women with cancer. Regardless of their health status, women are expected to fulfill caregiving and traditional wifely duties. These pressures add significant emotional and physical strain, making it even harder for patients to focus on their recovery. Although health extension workers aim to support patients, they may inadvertently reinforce societal norms by advising women to prioritize their husbands’ needs, often due to limited knowledge or training.

“Beyond their illness, patients want us to listen about their lives, particularly how their condition affects their husbands. Cervical cancer patients often express frustration that men fail to understand the pain related to that area. They talk about this extensively, sometimes to the point where there is nothing left to say.” (KII11, Health extension worker)

“Mostly, when cervical cancer patients tell me about their intimacy issues with their husbands, I advise them to take care of their husbands because, after all, this is their life. So, I just advise them to suggest that their husbands search for a solution because she can’t provide what he is asking, and for her to accept that, that is how we help.” (KII17, Health extension worker)

Human resource limitations

High workloads and insufficient staffing are critical barriers to the sustainable provision of psychosocial services. As a result, despite receiving training, many healthcare providers stop offering psychosocial services due to their other overwhelming clinical responsibilities. Although healthcare professionals across various facilities received psychosocial support training, in some settings such services were discontinued shortly after training due to competing clinical duties. Healthcare professionals often find themselves juggling psychosocial support duties alongside their regular clinical responsibilities, leaving little time or energy to focus on this critical aspect of patient care. The absence of dedicated resources further compounded the issue, making it difficult to provide consistent and effective psychosocial support.

“There aren’t many dedicated resources for psychosocial support. Currently, it’s often handled by professionals who juggle it with their other routine responsibilities. Many individuals stopped working after receiving the training because of their other routine clinical responsibilities.” (KII09, BSc nurse)

In rural areas, the situation was even more pronounced. Health extension workers, who initially received training on how to conduct home visits, were often faced with increased workloads when their colleagues left for personal reasons, such as relocation or childbirth. The added responsibilities forced the remaining health extension workers to schedule home visits beyond regular working hours, to include weekends and late nights.

“Because the one working with me relocated for personal reasons, I had to work outside my regular schedule, on weekends, or after normal working hours, which makes my schedule very busy.” (KII14, Health extension worker)

In referral facilities, high patient flow and overwhelming workload presented additional challenges. Healthcare providers in these settings often struggled to find the time needed to offer psychosocial support services. Many healthcare professionals pointed out that the high volume of patients left them with little opportunity to engage with patients on a personal level. As a result, despite their training and good intentions, healthcare professionals were often unable to deliver the psychosocial care that patients needed, further highlighting the significant human resource barriers to effective provision of psychosocial services.

“Sometimes, patients might not get the chance to see us due to time constraints and routine clinical activity.” (KII04, BSc nurse)

“The high patient flow and heavy workload make it difficult to provide psychosocial support, these are our biggest challenges. (KII03, Oncology nurse)

Space constraints

Overcrowding in clinical oncology settings often limits privacy, hindering the delivery of effective psychosocial support. Shared spaces and chaotic environments force healthcare professionals to improvise, disrupting meaningful conversations and leaving both providers and patients feeling unsupported.

Another critical issue is the absence of designated counseling rooms in many facilities. In the absence of private, quiet spaces for sensitive discussions, healthcare professionals often find themselves “begging for rooms” to conduct counseling sessions. This lack of a dedicated area for psychosocial support undermines the quality of care, as counseling takes place in public or shared spaces where confidentiality is compromised. Without adequate space, meaningful, private conversations become increasingly difficult, reducing the overall effectiveness of the psychosocial care provided.

“All patients are initially checked in a single OPD, where nurses and surgeons work together. Because it’s not practical to talk to them under such conditions, I would make the patients wait until after their consultation, because of which they might have to stay until the evening to get counseling.” (KII05, BSc Nurse)

“There isn’t a designated area, so we end up talking to them wherever we can, which is challenging. Having meaningful conversations with patients in public areas like the hallway is not motivating.” (KII02, Oncology nurse)

Facilitators to the provision of psychosocial support

Training and supervision

Psychosocial support training equips providers with the means to understand and respond to the emotional dimensions of cancer care, ultimately transforming the way healthcare professionals approach patient support.

“Before the training, I had no experience in handling my patients’ emotions. But afterwards, I learned how to build strong interpersonal relationships with them and better understand the emotional burden each patient carries.” (KII18, BSc nurse)

Another crucial factor in the successful provision of psychosocial support is close supervision and support of healthcare professionals during supportive supervision. Nurses and staff members emphasized the importance of timely assistance and regular follow-ups from project implementers during support provision. When uncertainties or challenges arose, access to immediate guidance enabled healthcare providers to remain focused and maintain the necessary level of psychosocial support for patients.

“Consistent supportive follow-ups and sustainable supervision have significantly impacted my commitment and the quality of care I provide.” (KII05, BSc nurse)

Relatability and relevance of audio-visual materials

Patients expressed appreciation for survivor stories that were displayed during group discussion sessions. Audio-visual materials showcasing actual patient survivor stories and experiences are highly relatable, enhancing their appeal and the preference for such formats. Similarly, healthcare providers also noted that patients were excited while watching the survivor stories, which helped to promote more active discussions among the patients.

“I remember the video vividly … She shared her treatment journey as a cancer patient and how both her breasts were removed … Her powerful message made me see cancer as just another disease, something we shouldn’t let overwhelm us. I used to worry about my situation, but after watching her video, I learned to accept it. There are those in worse conditions, and that realization brought me peace.” (IDI02, Breast cancer patient)

Provision of travel reimbursements and refreshments

Regardless of whether they come from urban or rural areas, cancer patients face significant challenges in terms of time and financial constraints that make it more difficult to attend healthcare appointments. Travelling to health facilities for medical care often disrupts patients’ daily routines, causing stress and imposing additional costs. However, one important facilitator in overcoming these barriers is the provision of transportation reimbursements for patients as well as healthcare professionals.

“We used to compensate patients for their transportation costs after they attended support group discussions, which eased their attendance in the group discussions.” (KII12, BSc nurse)

“My transport expenses were covered when I travelled to them, or theirs will be covered when they come to us.” (KII09, BSC nurse)

Coffee ceremonies are a deeply rooted tradition in Ethiopian culture; and are regarded as a symbol of respect and hospitality, and a means of fostering meaningful connections. These ceremonies were incorporated into support-group discussions to create a culturally enriched and welcoming environment. Nurses observed that patients responded positively, expressing appreciation for the incorporation of these cultural ceremonies because they evoked a sense of home and belonging, which helped patients feel more at ease discussing emotional issues.

“What we witnessed during that time was that the tea and coffee ceremony helped us a lot with communication. People love coffee! People love ceremony! So, when you prepare things like that, people come and discussions will be easier.” (KII03, Oncology nurse)

Suggestions for improvement

Healthcare professionals reported that the training program lacked sufficient practical sessions. They suggested extending the training program to include more hands-on learning and requested additional periodic training sessions to ensure comprehensive and up-to-date knowledge.

“I don’t believe that I received extensive training, as it was for a very brief period. Additional periodic training is necessary.” (KII09, BSc nurse)

“Practical training will enable us to have a better experience in counseling and improve our understanding of the patients.” (KII21, MSc nurse)

Healthcare professionals highlighted the need for psychosocial support training to be extended across all departments involved in cancer care; and emphasized the importance of involving healthcare administration and management and helping them recognize its value and support its integration into practice.

“Involving managerial staff as well as each department in the training would further strengthen the initiative by addressing system-level issues.” (KII05, BSc nurse)

In the absence of standardized guidelines, healthcare professionals often rely on personal experience, leading to inconsistent psychosocial support provision. Providers highlighted the need for a clear manual to ensure consistent and effective psychosocial care.

“Initially, the psychosocial support provision was irregular, but through repetition, we learned the process. A manual would help us improve and stay up to date.” (KII13, MSc nurse)

Discussion

This study has identified several barriers to the provision of psychosocial support for cancer patients, including: limited awareness, cultural misconceptions, resistance to home visits, patients’ personal circumstances, logistical challenges, communication problems, and knowledge gaps. Conversely, key facilitators included: targeted psychosocial support training, relatability and relevance of audio-visual materials, distribution of travel reimbursements and refreshments, and supervision.

We found that limited awareness of the availability and significance of psychosocial support services was a key barrier to the effective provision of such support services. This finding is in agreement with previous studies, indicating that low awareness of supportive care within the healthcare setting impedes its utilization and the ability of healthcare professionals to provide psychosocial support services (20, 21). This observed awareness gap may be attributed to inadequate integration of psychosocial services in the healthcare system, and insufficient outreach activities designed to raise patient awareness and understanding regarding the availability and potential benefits of psychosocial support services in cancer care. Misconceptions about psychosocial support have emerged as a key barrier in the this study. Despite its recognized importance, psychosocial support is often given a low priority in cancer treatment settings. Consistent with this, previous research has also indicated that healthcare providers tend to place greater emphasis on medical and routine bedside care, addressing psychosocial needs only when time permits (22). The marginalization of psychosocial support in cancer care may originate from the greater emphasis placed on biomedical treatment modalities, where clinical priorities often focus solely on patients’ physical outcomes. Further, the absence of structured frameworks for psychosocial support integration hinders its systematic inclusion in oncology services, leading to its delivery being relegated to overburdened nurses or staff who often lack specialized training. Consequently, psychosocial care is frequently overlooked.

Previous studies have shown that patients often tend to avoid psychosocial support services due to lack of cultural sensitivity (23, 24). They also emphasized a need for more culturally sensitive cancer support programs, since these can increase patient engagement and service utilization (25). Similarly, in our study, cultural misconceptions and taboos were identified as barriers to the provision of psychosocial support via informational brochures, because some cultures are not accustomed to open communication between patients and their children regarding difficult conditions like cancer. In addition, this study revealed that gender stereotypes shaped by cultural norms influenced participation in supportive care activities, with men less likely than women to engage in support group discussions. This finding is in line with previous studies indicating that women are generally more comfortable expressing emotional concerns, whereas men tend to be more reserved (26, 27). Further, studies have identified that, generally, men are less likely to seek help for health issues than women (28). This also applies to receiving psychological support (29). Although there are various reasons for this, perceptions that men should be strong or that mental illness is less serious than physical illness can be mentioned (30). Such reluctance may arise from cultural notions, which are deeply rooted in communities that associate emotional expression and seeking support as female traits and portray emotional restraint as a marker of masculinity.

In our study, some participants resisted certain components of psychosocial support, such as home visits. This was due to several factors, including the social stigma surrounding their illness, reluctance to have their names associated with cancer, and lack of awareness about the purpose of the home visit. In support of this finding, previous studies on psychosocial service provision for patients and their caregivers indicated that stigma-related fears can represent a significant barrier, as patients may avoid utilizing these services to prevent being recognized as someone with the disease condition (25, 31). This resistance may arise from patients’ lack of trust in healthcare providers, as some do not believe their medical information will be safeguarded, even by professionals. Another reason may be the failure of nurses to inform patients during counseling about the planned follow-up home visits by health extension workers. Patients should be informed first before conducting home visitations, since lack of awareness and consent can lead to resistance.

Clear and effective communication between healthcare providers and patients is essential for cancer treatment. However, our study revealed that psychosocial support, including counseling about the cancer diagnosis, treatment choices and prognosis, often remains neglected, leaving patients uninformed, and resulting in frustration and mistrust in the healthcare system. Similarly, a study in Australia found that lack of communication, including healthcare providers’ reluctance to hold difficult conversations with their patients, is a major barrier to providing effective psychosocial care (32). This reluctance to share critical information with patients may result from healthcare providers’ desire to avoid the emotional burden associated with confronting issues beyond their control, such as treatment unavailability, prognosis, which falls outside of the scope of psychosocial services. Further, nurses also identified language as a barrier to the provision of psychosocial support that impedes effective communication. Similarly, previous studies have shown that when healthcare professionals do not speak the patients’ native language, significant communication challenges arise, hindering the delivery of quality psychosocial care (22, 33).

Family involvement in diagnosis disclosure was identified as a barrier to providing effective counseling services for patients. Caregivers often request that healthcare providers withhold diagnoses, because they believe that patients are too fragile to handle the emotional impact. As a result, patients remained uninformed about their condition and miss opportunities to receive psychosocial support from healthcare providers. Similarly, studies conducted in the Middle East have shown that frequent ‘do not tell’ requests from families influence the patient disclosure process, often resulting in physicians disclosing the diagnosis to family members rather than directly to the patient (34, 35). Another study focusing on family requests for nondisclosure, which focused on the case of low- and middle-income countries, indicated that families often request nondisclosure to protect patients from emotional distress, especially in cases of serious illness (36). Further, a scoping review of clinical communication in cancer care among 19 African countries reflects that cultural orientations toward communalism over individualism, which is rooted in the Ubuntu philosophy of interconnectedness, which is common across diverse African settings, indicates that open discussion about diagnosis, prognosis and end-of-life or death is taboo in many places (37). As a result, families interfere with the disclosure process, which is a common challenge in these settings (38). Moreover, a study conducted in Ethiopia on the preferences of patients, families, and the general public regarding cancer diagnosis disclosure revealed that while patients wish to be informed about their diagnosis and poor prognosis and prefer that oncologists do not withhold such information, family caregivers often prefer that this information be withheld from patients (39). Caregiver influence may stem from societal norms that support withholding serious illness-related information or bad news from affected individuals. While not universal, these norms are often rooted in a desire to shield the person from emotional distress, fear, or potential social stigma.

In this study, nurses reported feeling unprepared to respond to patients’ inquiries during psychosocial support sessions, largely due to insufficient training and limited knowledge. Similarly, a previous study indicated that healthcare providers’ ability to provide supportive care services is significantly influenced by the professionals having proper knowledge to engage in such activities (40). In addition, another study on the potential barriers to psychosocial care provision revealed that nurses’ feelings of inadequacy was another barrier that prevents the provision of psychosocial support care (22).

Moreover, heavy workloads due human resource shortages and high staff turnover were also identified as barriers to the effective provision of psychosocial support in the present study. In line with our findings, studies examining the educational needs of inpatient oncology nurses providing psychosocial care also identified heavy workloads and staff turnover as primary barriers, leaving nurses with limited time to offer psychosocial support (41–44), because busy clinical schedules often limit the ability of clinicians to engage in meaningful conversations with patients.

The lack of designated space for counseling was also reported by each of the healthcare facilities included in the present study as a critical barrier to the provision of psychosocial services. In support of this, a previous study also concluded that the lack of private space for counseling was a significant barrier (44), because confidential settings are necessary to maintain patient privacy during counseling sessions.

Our findings revealed that various factors contribute to the effective provision of psychosocial support activities. Key facilitators identified in the current study included implementation of training programs on how to provide psychosocial support, as well as the relatability and relevance of psychosocial support materials. Resources that depict real patient experiences tend to be more engaging and preferred by service users. Similarly, previous studies have shown that interventions tailored to the specific needs of the target group are widely appreciated and properly utilized by participants (45, 46). Other key facilitators the provision of psychosocial support identified in the current study include travel reimbursements for attendees, the provision of refreshments, and regular supervision for professionals. These findings are supported in the literature, where financial incentives to participants attending sessions (25), the availability of refreshments (47), and supervision (44) have all been identified as major facilitators that support the provision of psychosocial support activities.

A key strength of this study is the inclusion of both cancer patients and healthcare professionals, providing a comprehensive perspective on the barriers and facilitators of psychosocial service delivery. Furthermore, the study incorporates diverse data collection methods, verbatim transcription, and iterative review of data, which strengthen the credibility of our results. However, a notable limitation is the potential for translation bias. Transcribing and translating interviews from Amharic and Afan Oromo into English may have resulted in the loss of nuanced meanings, which could affect the depth and accuracy of our understanding of the perspectives and cultural expressions of study participants.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study identified limited awareness of psychosocial services as a key barrier to their effective provision and utilization. This finding highlights the importance of targeted outreach efforts in increasing awareness among patients and healthcare staff about the availability and benefits of cancer support services. Moreover, cultural misconceptions and taboos were found to impede supportive care, emphasizing the need to develop culturally sensitive educational materials to promote acceptance and engagement. Gender-related differences were also identified as influential factors, with stereotypical norms affecting patients’ willingness to engage in emotional communication. Supportive care programs should therefore adopt gender-sensitive approaches to enhance patient-clinician communication by recognizing these differences. Furthermore, patient resistance to home visits was linked to a lack of prior information about the visits and fear of stigma. This underscores the necessity for clear communication between healthcare providers and patients regarding the purpose and nature of the home visits. Building trust is also crucial to reassure patients that their confidentiality will be maintained. Lastly, communication gaps, especially concerning the disclosure of diagnosis, treatment options, and prognosis, were identified as barriers. This highlights the need for enhanced training in clinician–patient communication, both in professional practice and in the academic curricula. In addition, structured approaches, such as private conversations with family members, may help address the concerns of family members and support ethically sound disclosure practices within cancer care settings. Because the lack of private, designated spaces in oncology settings significantly impedes the delivery of confidential and effective psychosocial support; facilities should prioritize the establishment of dedicated counseling rooms to enhance the quality of PSS while maintaining patient dignity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Institutional review board of Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences with protocol number 071/24/SPH. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Else Kroener-Fresenius-Foundation Grant No. 2018_HA31SP. The project on which this publication is based was in part funded by the German Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) 01KA2220B to the RHISSA Programme for the NORA Consortium. This research was funded in part by Science for Africa Foundation to the Programme Del-22-008 with support from Wellcome Trust and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office and is part of the EDCPT2 programme supported by the European Union.

Acknowledgments

The research team wishes to thank all participants for generously sharing their time and experiences with us for this study. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to the School of Public Health, Addis Ababa University, and Martin Luther University for their support in completing this research project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Beatty L, Kemp E, Butow P, Girgis A, Schofield P, Turner J, et al. A systematic review of psychotherapeutic interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer: context matters. Psycho-oncology. (2018) 27:34–42. doi: 10.1002/pon.4445

2. Fox JP, Philip EJ, Gross CP, Desai RA, Killelea B, and Desai MM. Associations between mental health and surgical outcomes among women undergoing mastectomy for cancer. Breast J. (2013) 19:276–84. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12096

3. Wang Y and Feng W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen Psychiatry. (2022) 35:e100871. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100871

4. Fu WW, Popovic M, Agarwal A, Milakovic M, Fu TS, McDonald R, et al. The impact of psychosocial intervention on survival in cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Palliative Med. (2016) 5:9306–106. doi: 10.21037/apm.2016.03.06

5. Recklitis CJ and Syrjala KL. Provision of integrated psychosocial services for cancer survivors post-treatment. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:e39–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30659-3

6. Li M, Macedo A, Crawford S, Bagha S, Leung YW, Zimmermann C, et al. Easier said than done: keys to successful implementation of the distress assessment and response tool (DART) program. J Oncol practice. (2016) 12:e513–e26. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.010066

7. Grassi L, Fujisawa D, Odyio P, Asuzu C, Ashley L, Bultz B, et al. Disparities in psychosocial cancer care: a report from the International Federation of Psycho-oncology Societies. Psycho-Oncology. (2016) 25:1127–36. doi: 10.1002/pon.4228

8. Wondimagegnehu A, Abebe W, Hirpa S, Kantelhardt EJ, Addissie A, Zebrack B, et al. Availability and utilization of psychosocial services for breast cancer patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a mixed method study. Eur J Cancer Care. (2023) 2023:5543335. doi: 10.1155/2023/5543335

9. Belete NG, Bhakta M, Wilfong T, Shewangizaw M, Abera EA, Tenaw Y, et al. Exploring the impact of breast cancer support groups on survivorship and treatment decision-making in eastern Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Supportive Care Cancer. (2025) 33:419. doi: 10.1007/s00520-025-09475-w

10. Wondimagegnehu A, Zebrack B, Addissie A, and Kantelhardt EJ. Integrating Psychosocial services in routine cancer care: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Unpublished.

11. Fereday J and Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. (2006) 5:80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107

12. Swain J. A hybrid approach to thematic analysis in qualitative research: Using a practical example. SAGE Res Methods. (2018). doi: 10.4135/9781526435477

13. Bonner C, Tuckerman J, Kaufman J, Costa D, Durrheim DN, Trevena L, et al. Comparing inductive and deductive analysis techniques to understand health service implementation problems: a case study of childhood vaccination barriers. Implementation Sci Commun. (2021) 2:100. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00202-0

14. Braun V and Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

15. Tong A, Sainsbury P, and Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

17. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ information. (2004) 22:63–75. doi: 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

18. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, and Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. (2017) 16:1609406917733847. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

19. Braun V and Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res sport Exercise Health. (2019) 11:589–97. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

20. Eakin EG and Strycker LA. Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: patient and provider perspectives. Psycho-Oncology. (2001) 10:103–13. doi: 10.1002/pon.500

21. Nápoles-Springer AM, Ortíz C, O’Brien H, and Díaz-Méndez M. Developing a culturally competent peer support intervention for Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. J immigrant minority Health. (2009) 11:268–80. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9128-4

22. Chen CS, Chan SW-C, Chan MF, Yap SF, Wang W, and Kowitlawakul Y. Nurses’ perceptions of psychosocial care and barriers to its provision: A qualitative study. J Nurs Res. (2017) 25:411–8. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0000000000000185

23. Avis M, Elkan R, Patel S, Walker BA, Ankti N, and Bell C. Ethnicity and participation in cancer self-help groups. Psycho-Oncology. (2008) 17:940–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.1284

24. Paskett ED, DeGraffinreid C, Tatum CM, and Margitić SE. The recruitment of African-Americans to cancer prevention and control studies. Prev Med. (1996) 25:547–53. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0088

25. Davey MP, Kissil K, Lynch L, Harmon L-R, and Hodgson N. Lessons learned in developing a culturally adapted intervention for African-American families coping with parental cancer. J Cancer Education. (2012) 27:744–51. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0398-0

26. Cossich T, Schofield P, and McLachlan S. Validation of the cancer needs questionnaire (CNQ) short-form version in an ambulatory cancer setting. Qual Life Res. (2004) 13:1225–33. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000037496.94640.d9

27. Clarke S-A, Booth L, Velikova G, and Hewison J. Social support: gender differences in cancer patients in the United Kingdom. Cancer nursing. (2006) 29:66–72. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200601000-00012

28. Sierra Hernandez CA, Han C, Oliffe JL, and Ogrodniczuk JS. Understanding help-seeking among depressed men. Psychol Men Masculinity. (2014) 15:346. doi: 10.1037/a0034052

29. Leong FT and Zachar P. Gender and opinions about mental illness as predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Br J Guidance Counselling. (1999) 27:123–32. doi: 10.1080/03069889908259720

30. Ogueji IA and Okoloba MM. Seeking professional help for mental illness: A mixed-methods study of black family members in the UK and Nigeria. psychol Stud. (2022) 67:164–77. doi: 10.1007/s12646-022-00650-1

31. Dörr P, Führer D, Wiefel A, Bierbaum A-L, Koch G, Klitzing KV, et al. Unterstützung von Familien mit einem an Krebs erkrankten Elternteil und Kindern unter fünf Jahren–Darstellung eines Beratungskonzeptes. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie. (2012) 61:396–413. doi: 10.13109/prkk.2012.61.6.396

32. Mishra S, Bhatnagar S, Philip FA, Singhal V, Rana SPS, Upadhyay SP, et al. Psychosocial concerns in patients with advanced cancer: An observational study at regional cancer centre, India. Am J Hospice Palliative Medicine®. (2010) 27:316–9. doi: 10.1177/1049909109358309

33. Parthab Taylor S, Nicolle C, and Maguire M. Cross-cultural communication barriers in health care. Nurs Standard. (2013) 27(31):35–43. doi: 10.7748/ns2013.04.27.31.35.e7040

34. Ozdogan M, Samur M, Artac M, Yildiz M, Savas B, and Bozcuk HS. Factors related to truth-telling practice of physicians treating patients with cancer in Turkey. J palliative Med. (2006) 9:1114–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1114

35. Laxmi S and Khan JA. Does the cancer patient want to know? Results from a study in an Indian tertiary cancer center. South Asian J cancer. (2013) 2:57. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.110487

36. Taub S and Macauley R. Responding to parental requests for nondisclosure to patients of diagnostic and prognostic information in the setting of serious disease. Pediatrics. (2023) 152:e2023063754. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-063754

37. DeBoer RJ, Wabl CA, Mushi BP, Uwamahoro P, Athanas R, Ndoli DA, et al. A scoping review of clinical communication in cancer care in Africa. Oncologist. (2025) 30:oyaf039. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyaf039

38. Mulugeta T, Alemu W, Tigeneh W, Kaba M, and Haileselassie W. Breaking bad news in oncology practice: experience and challenges of oncology health professionals in Ethiopia–an exploratory qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e087977. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2024-087977

39. Abraha Woldemariam A, Andersson R, Munthe C, Linderholm B, and Berbyuk Lindström N. Breaking bad news in cancer care: Ethiopian patients want more information than what family and the public want them to have. JCO Global Oncol. (2021) 7:1341–8. doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00190

40. Vaccaro L, Shaw J, Sethi S, Kirsten L, Beatty L, Mitchell G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to community-based psycho-oncology services: A qualitative study of health professionals’ attitudes to the feasibility and acceptability of a shared care model. Psycho-oncology. (2019) 28:1862–70. doi: 10.1002/pon.5165

41. Chen CH. Educational needs of inpatient oncology nurses in providing psychosocial care. Number 1/February 2014. (2014) 18:E1–5. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.E1-E5

42. Lawless J, Wan L, and Zeng I. Patient care’rationed’as nurses struggle under heavy workloads–survey. Kaitiaki Nurs New Zealand. (2010) 16(7):16–8.

43. Troup J, Fuhr DC, Woodward A, Sondorp E, and Roberts B. Barriers and facilitators for scaling up mental health and psychosocial support interventions in low-and middle-income countries for populations affected by humanitarian crises: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health systems. (2021) 15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13033-020-00431-1

44. Upadhaya N, Regmi U, Gurung D, Luitel NP, Petersen I, Jordans MJ, et al. Mental health and psychosocial support services in primary health care in Nepal: perceived facilitating factors, barriers and strategies for improvement. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-2476-x

45. Paschen B, Saha R, Baldus C, Haagen M, Pott M, Romer G, et al. Evaluation of a preventive counselling service for children of somatically ill parents. Psychotherapeut. (2007) 52:265–72. doi: 10.1007/s00278-006-0525-7

46. Christ GH, Raveis VH, Siegel K, Karas D, and Christ AE. Evaluation of a preventive intervention for bereaved children. J Soc work end-of-life palliative Care. (2005) 1:57–81. doi: 10.1300/J457v01n03_05

Keywords: cancer, psychosocial support, barriers, facilitators, integration and routine care

Citation: Belay W, Ware FA, Kaba M, Addissie A, Kantelhardt EJ and Wondimagegnehu A (2025) Barriers and facilitators of psychosocial service provision for patients with cancer across six hospitals in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. Front. Psychiatry 16:1689641. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1689641

Received: 20 August 2025; Accepted: 27 October 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

María Cantero-García, Universidad a Distancia de Madrid, SpainReviewed by:

Mozhgan Moshtagh, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, IranElizabeth Wood, University of Notre Dame, United States

Copyright © 2025 Belay, Ware, Kaba, Addissie, Kantelhardt and Wondimagegnehu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eva Johanna Kantelhardt, ZXZhLmthbnRlbGhhcmR0QHVrLWhhbGxlLmRl

†These authors share senior authorship

‡ORCID: Finina Abebe Ware, orcid.org/0000-0003-0465-1831

Winini Belay

Winini Belay Finina Abebe Ware3‡

Finina Abebe Ware3‡ Mirgissa Kaba

Mirgissa Kaba Adamu Addissie

Adamu Addissie Eva Johanna Kantelhardt

Eva Johanna Kantelhardt