Abstract

Background:

Depression is highly prevalent among nursing students (28.7%–30%). Although previous studies have identified multiple influencing factors, the lack of systematic prioritization hinders targeted intervention in resource-limited contexts. This study employed XGBoost and SHAP values to identify and prioritize key risk factors, thereby establishing a data-driven framework to assist educational administrators in optimizing resource allocation and facilitating early detection and personalized support.

Methods:

This multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted from September to December 2024 among nursing students recruited from ten universities in Shandong, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Sichuan provinces. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire comprising a demographic characteristics form, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS). Data cleaning was performed in Excel, and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 27.0 and Python 3.9.

Results:

The incidence of depression among nursing students is 28.60%. According to the random forest model, the order of depression predicted by this study from high to low is Sleep Condition, Social anxiety, Mother's Educational Level, Sexual Orientation, Smoking, and Household composition.

Conclusion:

Depression is highly prevalent among nursing students, representing a significant challenge to both student well-being and the future healthcare workforce. This study identified and prioritized key determinants of depression, including poor sleep quality, social anxiety, low maternal education, sexual minority status, smoking, and single-parent family background. These findings can provide a basis for nursing administrators and educators to develop targeted and personalized intervention strategies.

Introduction

A recent report by the World Health Organization highlights a worrying trend: around 14% of adolescents worldwide are affected by mental disorders, with depression being the leading cause of mental health conditions and health burden in this population (1).

This issue is particularly acute in higher education settings, where current data indicate that the prevalence of depression among college students is 17.3% (2), posing a serious challenge to these institutions (3). Furthermore, a high prevalence of depression is particularly evident among nursing students. Due to various stressors they encounter during their college years, they are more prone to depression (4, 5). The academic literature increasingly recognizes depression as a significant barrier to educational achievement in the university environment (6). Nursing students shoulder the heavy responsibility of saving the dead and healing the wounded (7). They are under pressure to acquire theoretical knowledge and professional skills (7). In addition, the pressures of clinical training experience represent a significant risk factor for psychological issues, with depression being the most common manifestation (8). Previous studies have confirmed that nursing students have a higher incidence of depression (9–11). A meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence of depression among nursing students as high as 34.0%, with a notably higher prevalence of 43.0% in Asian subgroups (12). A study conducted in China reported a prevalence of 28.7% among nursing students (13). The detrimental impact of depression on nursing students' health extends to patient care, as it can hinder effective communication and patient engagement, thereby compromising care quality (11). Therefore, it is of great significance to identify the factors that affect nursing students' depression. While previous studies using traditional logistic regression have identified factors associated with depression in nursing students (14, 15), this method cannot quantify their relative importance or model complex interactions, limiting its utility for prioritizing interventions. To address this, our study employs the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm. XGBoost enhances predictive performance by integrating weak learners through structured loss function optimization and techniques like pre-sorting and weighted quantiles, which also prevent overfitting and improve generalization (16). Crucially, its built-in feature importance metrics provide an initial risk ranking. Furthermore, we integrate the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) framework to conduct an interpretability analysis. SHAP quantifies the direction and magnitude of each feature's impact on individual predictions (17), providing personalized insights. Therefore, by combining XGBoost's predictive power with SHAP's interpretability, this study aims to identify, prioritize, and interpret the key factors influencing depression among nursing students. The aim of this study is to provide nursing educators with a transparent, data-driven framework for the early identification of at-risk students and the formulation of targeted prevention strategies.

Methods

Participants

A multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted from September to December 2024 using a convenience sampling method. The study recruited 2,044 nursing students from ten universities across five provinces in China (Shandong, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, and Sichuan). Inclusion criteria were (1): enrollment as a nursing student and (2) provision of informed consent. The exclusion criterion was a clinical diagnosis of any mental health condition, regardless of medication status. We have supplemented the flowchart. For details, please refer to Appendix Figure 1.

Data collection

The electronic questionnaire was distributed to potential participants through nursing faculty at each participating university.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Institute of Technology (Approval No. QIT-2024-0081). Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants before they could proceed to the survey questions. The survey was anonymous, and participation was voluntary.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the rule of thumb of having at least 10 events per variable (EPV) (18). With 19 variables anticipated for inclusion in the model, a minimum of 190 events was required. Considering an estimated depression prevalence of approximately 28.7% and a potential loss-to-follow-up rate of 20%, the initial target sample size for model development was calculated to be 238 participants. Furthermore, as the modeling sample typically constitutes 70% of the total dataset (with the remaining 30% reserved for validation), the total minimum sample size required was 340 participants. A total of 2,044 students completed the survey. After excluding respondents who answered in too short or too short, valid data were obtained for 2,024 participants, with an effective recovery rate of 99.022%.

Measurement tools

Demographic characteristics

Based on a review of relevant literature (11, 19, 20) and consultations with field experts, we developed a demographic characteristics questionnaire. The questionnaire encompassed the following items: gender, age, ethnicity, educational level, school type, residence, household composition, household monthly income (¥), father's educational level, and mother's educational level.

Assessment of depression

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), developed in 1977, is a widely used instrument for screening depressive symptoms (21). There are 20 items on the scale, graded 0-3, with a total score of 0–60 points. The assessment is conducted according to the actual situation in the latest week. No more than 1 day, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, and 5–7 days correspond to "no or almost no," "rarely," "often," and "almost always," respectively. The scale includes four dimensions: depressive mood, positive mood, physical disorder, and interpersonal relationship. A score of ≥16 indicates the presence of depressive symptoms (21). This scale has excellent reliability and validity (22, 23). In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the sample was 0.964.

Assessment of social anxiety

Social anxiety was evaluated using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS), compiled by Leary (24), the scale has a total of 15 items, and a single dimension is used to assess the tendency of subjective social anxiety experience independent of behavior. Using a 5-point scale, from "1" = "not at all" to "5" = "very consistent". The score ranges from 15 to 75 points, and 45 points are generally used as the standard for detecting social anxiety symptoms (25). In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the sample was 0.828.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS27.0 software. Count data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Univariate analysis was performed using the χ2 test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study adopted Pandas, NumPy, and XG Boost libraries in the Python 3.9 environment for data entry, cleaning, transformation, and analysis. The dataset contains 2024 records with a total of 18 variables. All variables are of integer type (int64), and no missing values exist. During the modeling process, based on the variables extracted by single-factor analysis, the xg boost library was used to construct an Extreme Gradient Boosting Tree model to predict the degree of social fattening. This model is trained by integrating multiple gradient-boosting trees. The core hyperparameters include the maximum depth of the tree (max_depth), the number of trees (n_estimators), and the learning rate (learning_rate, with a default value of 0.1). The remaining parameters all use the default hyperparameters encapsulated in the xgboost library. To balance the computational cost of the model and the prediction performance, hyperparameter optimization is achieved through the Grid Search CV tool combined with 5-fold cross-validation, with specific ranges of max_depth (1 to 20) and n_estimators (5 to 50). Taking the Accuracy of the test set as the evaluation criterion, the optimal parameter combination is screened. Furthermore, the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method is utilized to conduct an interpretability analysis of the model. The optimal feature subset is screened by combining feature importance ranking and cross-validation to enhance the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the model.

Results

General characteristics of the participants

A total of 2,024 nursing students were investigated in this study, including 406 males and 1,618 females. Among them, 28.60% of the people were rated as depressed. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the depression group and the non-depression group. The Household composition, Household Monthly Income, Mother's Educational Level, Sleep Condition, Smoking, Alcohol drinking, Social anxiety, and Sexual Orientation of the two participant groups were evaluated, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 1

| Variables | Total | Depression | χ² | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1445) | Yes (N = 579) | ||||

| Gender | 3.793 | 0.051 | |||

| Male | 406 | 274(18.96%) | 132 (22.80%) | ||

| Female | 1618 | 1171(81.04%) | 447 (77.20%) | ||

| Age(Years) | 0.354 | 0.838 | |||

| <20 | 1448 | 1029(71.21%) | 419 (72.37%) | ||

| 20-23 | 553 | 400(27.68%) | 153 (26.42%) | ||

| ≥24 | 23 | 16(1.11%) | 7 (1.21%) | ||

| Ethnic Group | 0.001 | 0.997 | |||

| Han Chinese | 2003 | 1430(98.96%) | 573 (98.96%) | ||

| Ethnic Minority | 21 | 15(1.04%) | 6 (1.04%) | ||

| Educational Level | 0.070 | 0.792 | |||

| Associate Degree or Below | 1093 | 783(54.19%) | 310(53.54%) | ||

| Undergraduate Degree | 931 | 662(45.81%) | 269(46.46%) | ||

| School type | 0.076 | 0.782 | |||

| Public School | 962 | 684(47.34%) | 278(48.01%) | ||

| Private School | 1062 | 761(52.66%) | 301(51.99%) | ||

| Clinical Practicum | 2.693 | 0.101 | |||

| Yes | 752 | 892(61.73%) | 380(65.63%) | ||

| No | 1272 | 553(38.27%) | 199(34.37%) | ||

| Residence | 0.540 | 0.462 | |||

| Urban Area | 1148 | 827(57.23%) | 321(55.44%) | ||

| Rural Area | 876 | 618(42.77%) | 258(44.56%) | ||

| Household composition | 12.866 | <0.001*** | |||

| Two-parent family | 1914 | 1383(95.71%) | 531(91.71%) | ||

| Single-parent family | 110 | 62(4.29%) | 48(8.29%) | ||

| Household Monthly Income(¥) | 7.339 | 0.025* | |||

| ≥5000 | 641 | 483(33.46%) | 158(27.29%) | ||

| 2000-4000 | 861 | 602(41.66%) | 259(44.73%) | ||

| <2000 | 522 | 360(24.91%) | 162(27.97%) | ||

| Father's Educational Level | 1.217 | 0.544 | |||

| Higher Education | 307 | 219(15.16%) | 88(15.20%) | ||

| High School | 455 | 334(23.11%) | 121(20.90%) | ||

| Junior High School or Below | 1262 | 892(61.73%) | 370(63.90%) | ||

| Mother's Educational Level | 9.616 | 0.008** | |||

| Higher Education | 262 | 187(12.94%) | 75(12.95%) | ||

| High School | 336 | 263(18.20%) | 73(12.61%) | ||

| Junior High School or Below | 1426 | 995(68.86%) | 431(74.44%) | ||

| Singleton | 2.199 | 0.138 | |||

| Yes | 466 | 320(22.15%) | 146(25.22%) | ||

| No | 1558 | 1125(77.85%) | 433(74.78%) | ||

| Sleep Condition | 136.418 | <0.001*** | |||

| Excellent | 1222 | 968(66.99%) | 254(43.87%) | ||

| Fair | 627 | 408(28.24%) | 219(37.82%) | ||

| Poor | 175 | 69(4.77%) | 106(18.31%) | ||

| Smoking | 18.559 | <0.001*** | |||

| Yes | 75 | 37(2.56%) | 38(6.56%) | ||

| No | 1949 | 1408(97.44%) | 541(93.44%) | ||

| Alcohol drinking | 13.288 | <0.001*** | |||

| Yes | 202 | 122(8.44%) | 80(13.82%) | ||

| No | 1822 | 1323(91.56%) | 499(86.18%) | ||

| Religious Belief | 1.664 | 0.197 | |||

| Yes | 128 | 85(5.88%) | 43(7.43%) | ||

| No | 1896 | 1360(94.12%) | 536(92.57%) | ||

| Social anxiety | |||||

| Yes | 521 | 308(21.31%) | 213(36.79%) | 51.772 | <0.001*** |

| No | 1503 | 1137(78.69%) | 366(63.21%) | ||

| Sexual Orientation | 14.798 | <0.001*** | |||

| Heterosexual | 1878 | 1361(94.19%) | 517(89.29%) | ||

| sexual minority | 146 | 84(5.81%) | 62(10.71%) | ||

| Academic Year | 9.260 | 0.055 | |||

| Secondary Vocational School | 84 | 64(4.43%) | 20(3.45%) | ||

| Freshman | 1082 | 765(52.94%) | 317(54.75%) | ||

| Sophomore | 133 | 83(5.74%) | 50(8.64%) | ||

| Junior | 248 | 176(12.18%) | 72(12.44%) | ||

| Senior | 477 | 357(24.71%) | 120(20.72%) | ||

General characteristics of the participants.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis

Logistic regression analysis revealed that Mother's Educational Level (Higher Education) (OR = 0.718, P = 0.030, 95%CI:0.532 to 0.968), Sleep status (Excellent) (OR = 0.215, P<0.001, 95%CI: 0.152 to 0.305)) is a protective factor for depression among nursing students. Smoking (OR = 2.673, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 1.682 to 4.249), sexual minority (OR = 1.943, P <0.001, 95%CI: 1.378 to 2.739), single-parent family(OR = 2.016, P<0.001, 95%CI: 1.365 to 2.978) and social anxiety (OR = 2.148, P < 0.001, 95%CI: 1.740 to 2.652) are risk factors for depression among nursing students, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Risk factor | Reference factor | B | SE | Waldx2 | P | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's Educational Level | Junior High School or Below | ||||||

| Higher Education | -0.332 | 0.152 | 4.731 | 0.030 | 0.718 | 0.532 to 0.968 | |

| Household composition | Two-parent family | ||||||

| Single-parent family | 0.701 | 0.199 | 12.430 | <0.001 | 2.016 | 1.365 to 2.978 | |

| Sleep Condition | Poor | ||||||

| Excellent | -1.535 | 0.177 | 75.021 | <0.001 | 0.215 | 0.152 to 0.305 | |

| Fair | -0.890 | 0.181 | 24.043 | <0.001 | 0.411 | 0.288 to 0.586 | |

| Smoking | No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.983 | 0.236 | 17.292 | <0.001 | 2.673 | 1.682 to 4.249 | |

| Sexual Orientation | Heterosexual | ||||||

| Sexual minority | 0.664 | 0.175 | 14.371 | <0.001 | 1.943 | 1.378 to 2.739 | |

| Social anxiety | No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.765 | 0.107 | 50.615 | <0.001 | 2.148 | 1.740 to 2.652 | |

| Constant | 2.587 | 0.390 | 44.014 | <0.001 | 13.296 |

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of depression in nursing students.

XG boost modeling results

Feature selection

Taking depression among nursing students (classified outcome) as the dependent variable, the regression analysis included Mother's Educational Level, Household composition, Sleep Condition, Smoking, Sexual Orientation and Social anxiety (P < 0.05) were included in the model.

Optimal subset

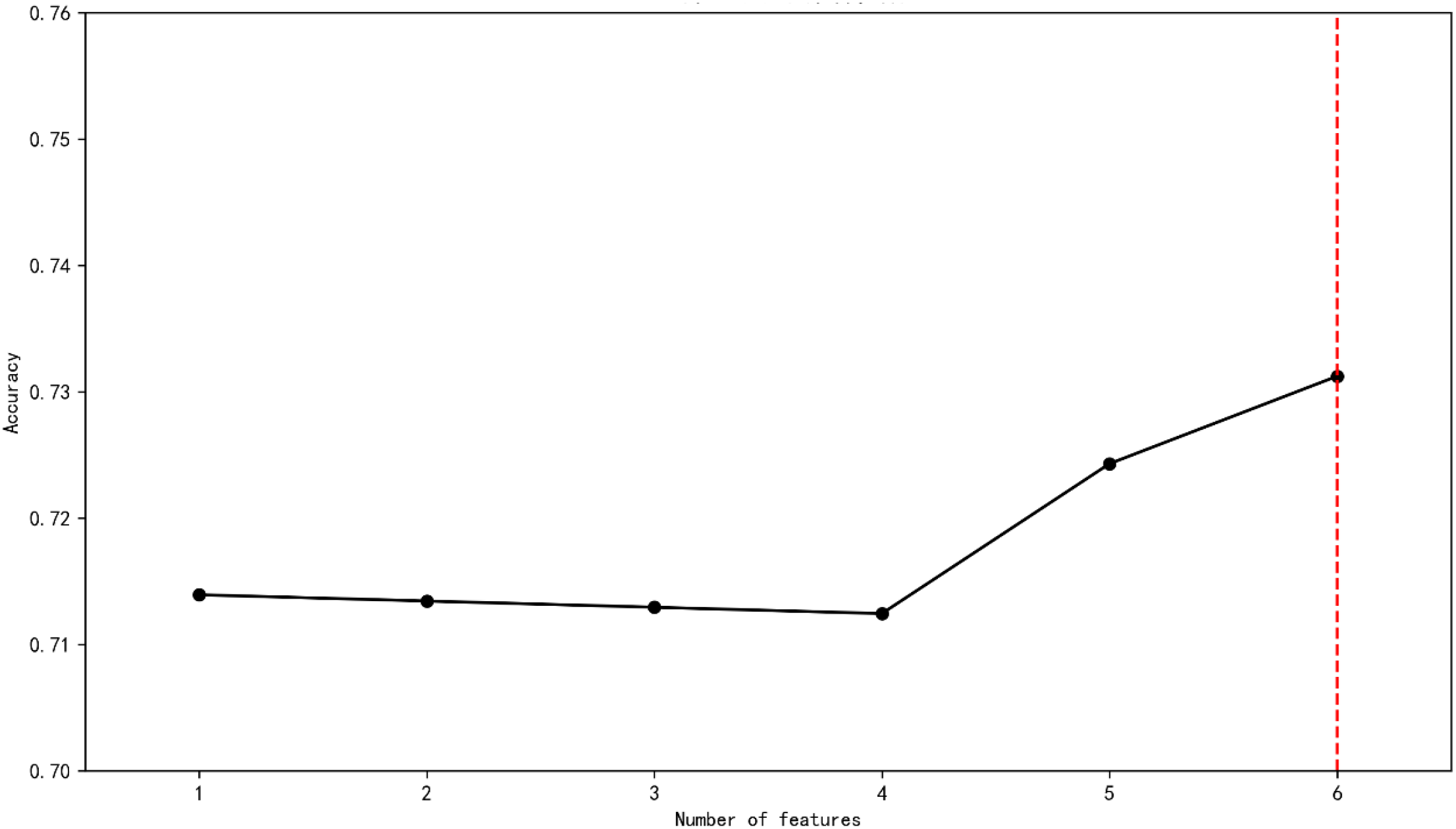

To evaluate the model performance and screen the optimal feature subset(the features were derived from CES-D), 5-fold cross-validation (5-CV) is adopted to evaluate the classification accuracy under different numbers of features. The results show that when the number of features is 6, the cross-validation accuracy reaches the maximum value of 0.731 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Screening the optimal feature subset.

Analysis of model performance and SHAP interpretability

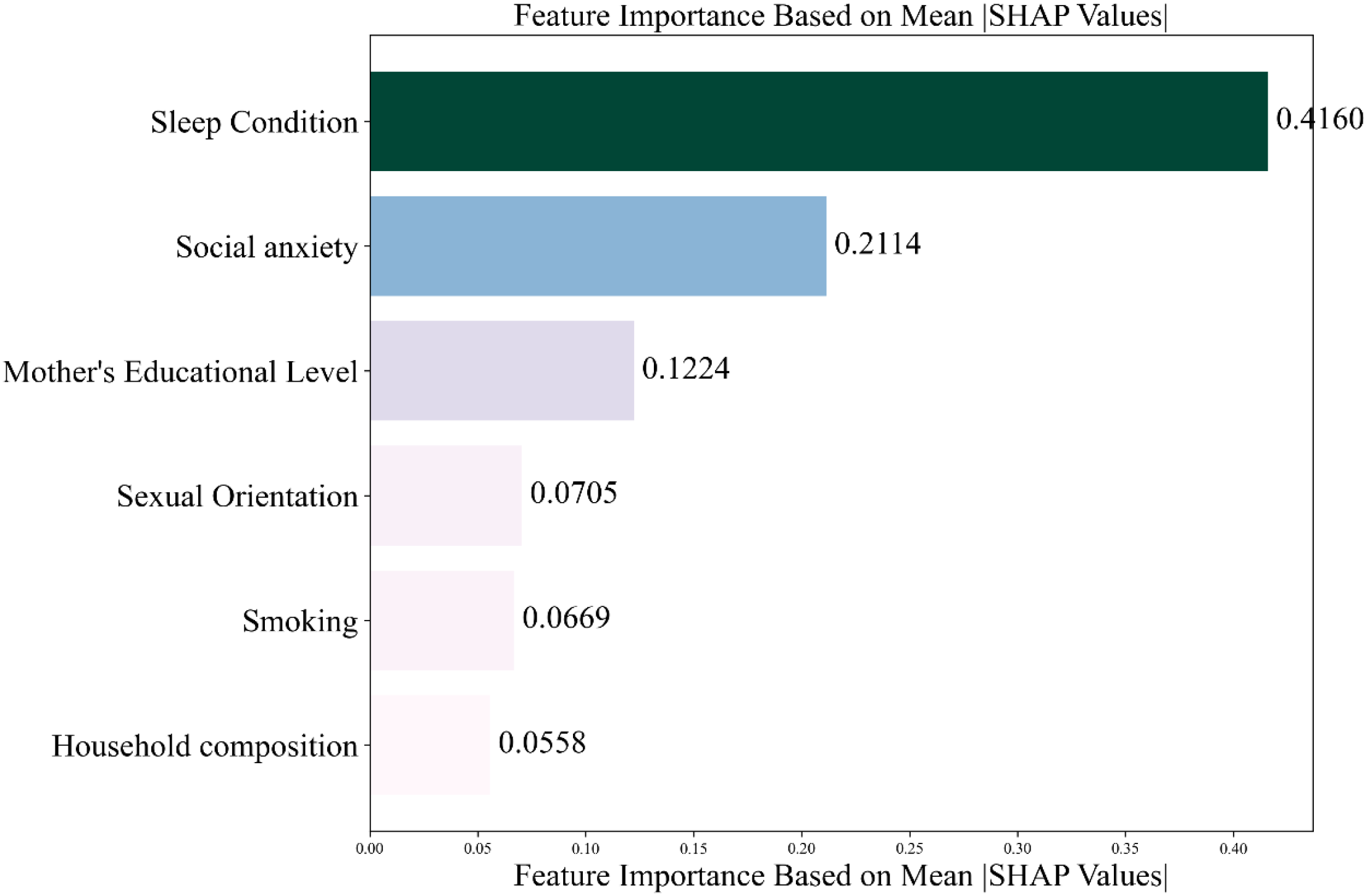

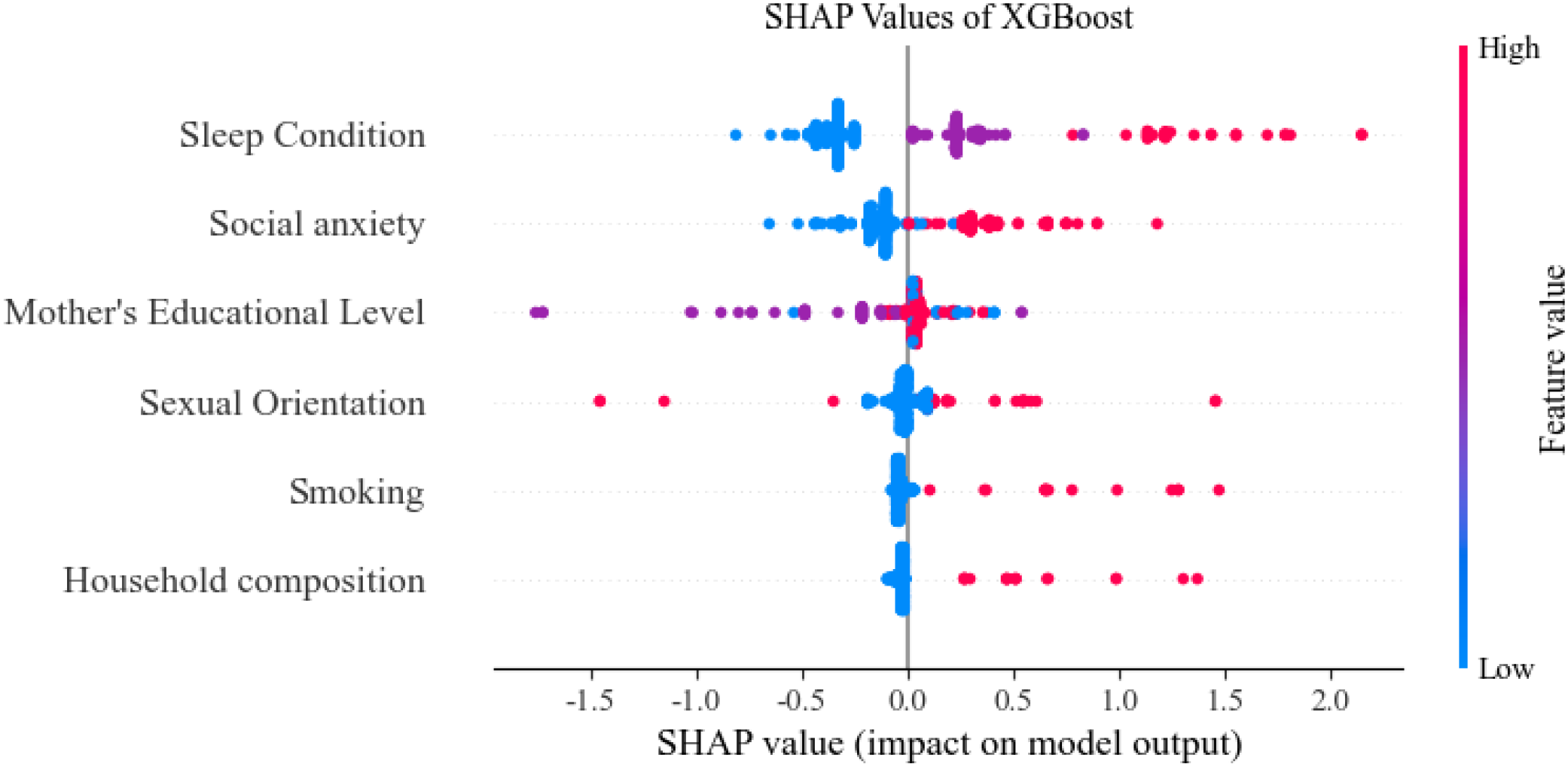

Based on the optimal feature subset, the training set (1619 records) and the test set (405 records) were divided in an 8:2 ratio to construct the optimized XG Boost classification model. The optimal parameters are max_depth = 20 and n_estimators = 50. The accuracy rate of the training set is 0.7431 and that of the test set is 0.7580. SHAP analysis was used to reveal the contribution of characteristics to the prediction of depression among nursing students. The SHAP feature importance bar chart (see Figure 2) shows that the average absolute SHAP values from high to low((see Figure 3).

Figure 2

Feature importance ranking.

Figure 3

SHAP value (impact on model output).

Discussion

The study revealed a depression prevalence of 28.60% among nursing students. Univariate regression analysis, using a statistical significance threshold of P < 0.05, initially identified several factors associated with depression: mother’s educational level, household composition, sleep condition, smoking, sexual orientation, and social anxiety. To further quantify the relative influence of these predictors, an XGBoost model was trained and evaluated using built-in feature importance scores and SHAP values. The results indicated that the key factors, ranked in descending order of association with depression, were: sleep condition, social anxiety, mother’s educational level, sexual orientation, smoking, and household composition.

This study investigated 2,024 nursing students and found a depression prevalence of 28.60%. Nursing is a discipline with substantial theoretical and practical demands. Nursing students must undertake clinical practice, skill-based operations, and theoretical examinations, resulting in a heavier academic burden—a factor identified as increasing the risk of depression (12, 26). Furthermore, trainee nurses frequently interact with patients and their families in clinical settings and are required to respond to unexpected clinical situations with timely judgment and scientifically sound solutions. For those newly entering clinical practice, these demands can disrupt the learning process and contribute to the development of negative emotions (27).The observed prevalence rate of 28.60% in our study is lower than the 39.5% reported by Ji et al. (28)among medical students in Anhui Province, but higher than the 21.0% reported by Chen et al. (29) among university students in Wuhan. These disparities may be partially attributable to differences in study populations and regional contexts. Nevertheless, the relatively high prevalence of depressive symptoms among nursing students in our sample underscores the importance of early identification of relevant influencing factors and implementation of targeted interventions to reduce depression rates and promote psychological well-being in this population.

Household composition is an influential factor in the occurrence of depressive symptoms among nursing students, ranking second in importance in this study. Those from single-parent families are at a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms, which aligns with previous research findings (30–32). Family structure plays a significant role in adolescent development, and the family function and environment of nursing students can directly affect their psychological well-being (33). Studies have shown that adolescents from single-parent families often experience a lack of parental care, family support, and companionship. When facing challenges, they are more likely to feel isolated and helpless, and the lack of emotional support makes them reluctant to communicate about their problems. Prolonged exposure to such conditions can lead to the emergence of negative psychological behaviors such as depression and anxiety (34).

Multiple studies have indicated that individuals with diverse sexual orientations have a higher tendency to develop depression (35–37). One possible explanation may be rooted in socio-cultural contexts. Influenced by traditional values, same-sex relationships have not yet gained widespread acceptance in broader Chinese society, which may contribute to a climate of relatively low social recognition for diverse sexual orientations. Furthermore, these individuals may encounter limited understanding and acceptance from their families and communities. The persistent perception of inadequate support could adversely affect psychological adjustment, potentially predisposing individuals to depressive symptoms. Therefore, nursing students from single-parent families and those with same-sex partners require stronger social support and psychological resilience. Schools and families should provide greater care to reduce the incidence of depressive symptoms and improve their overall mental health.

Better sleep quality (rated as excellent or fair) showed a significant inverse association with depressive symptoms among nursing students in this cross-sectional analysis, which is consistent with the findings of Roberts (38)and Raudsepp (39). In our study, sleep conditions ranked first among all influencing factors. Research indicates that chronic sleep deprivation can disrupt the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and dysregulation of this axis is associated with the development of depression (40). Furthermore, poor sleep quality may impair positive emotional response, mood regulation, short-term memory, and attention, while also reducing levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor—thereby contributing to the onset of depression (41–43). Therefore, educational institutions should pay greater attention to the sleep conditions of nursing students and strive to provide a favorable sleep environment (44). In addition, nursing students themselves should also prioritize maintaining regular sleep patterns to enhance their mental health and reduce the risk of depression (44).

This study found that nursing students who smoke exhibit a higher risk of depressive symptoms, which aligns with previous research (45, 46). Mechanistically, long-term nicotine intake from smoking alters neurotransmitter activity in the brain, leading to impaired emotional regulation and deficits in memory and executive function (47, 48). Furthermore, smoking can disrupt the HPA axis, resulting in excessive cortisol secretion and subsequent neurobiological dysregulation, ultimately contributing to emotional disorders and negative affective states (49). Therefore, it is recommended that educational institutions and families provide tailored smoking cessation interventions for nursing students who smoke, along with training in emotional management and stress coping strategies, to mitigate depression risk. In this study, a significant inverse association was observed between mother's higher education and depression in nursing students. Higher maternal educational attainment is associated with more scientific parenting philosophies and enhanced mental health literacy. These attributes predispose individuals to adopt rational cognitive reappraisal and adaptive emotion regulation strategies (50), which collectively exert a positive influence on nursing students' psychological well-being and consequently reduce the incidence of depression (51). Family support serves as a crucial psychological resource in preventing and alleviating depression among nursing students. We recommend cultivating a positive and communicative family atmosphere, strengthening parent–child communication, attentively listening to academic and internship challenges, and providing constructive guidance rather than excessive criticism, which may otherwise exacerbate self-isolation and depressive symptoms (52).

Social anxiety was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among nursing students, a finding consistent with the research by Flynn et al. (53). Social anxiety is a common anxiety disorder primarily characterized by excessive worry and fear of negative evaluation by others in social or interpersonal contexts (54). Individuals with social anxiety tend to engage in negative self-evaluation during social interactions, leading to impaired emotion regulation ability (55). The mood-congruence effect also suggests that individuals in negative emotional states prioritize negative information. Thus, social anxiety can induce an attentional bias toward depressive emotional stimuli, thereby exacerbating the development of depression (56). It is recommended that nursing students engage in rational self-assessment, overcome feelings of inferiority and timidity, and acquire specific psychological coping strategies to enhance psychological resilience and promote mental health. Furthermore, nursing students should strengthen interpersonal communication skills, learn social techniques, improve team collaboration awareness, and establish positive interpersonal relationships. These measures can help reduce negative emotional experiences, maintain a positive mood, and prevent the occurrence of social anxiety.

The occurrence of depressive symptoms in nursing students can impair their cognitive functioning and empathic abilities, thereby compromising clinical judgment (14, 57, 58). This not only poses potential risks to patient safety but may also exacerbate the nursing workforce shortage (59). Furthermore, persistent depression can erode nursing students' professional identity and vocational commitment, thereby diminishing career satisfaction and impeding long-term professional development (58). The current nursing education environment, characterized by heavy academic pressure, a competitive job market, and frequent neglect of students' emotional needs, may inadvertently contribute to the development of depressive symptoms (60). Therefore, it is recommended that nursing educators and administrators implement systematic screening to comprehensively assess students’ mental health status and provide early interventions targeting identified risk factors.

Strengths & limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first application of the XGBoost algorithm to predict depression risk among nursing students. The use of XGBoost offers distinct advantages, including its ability to handle complex nonlinear relationships, mitigate overfitting through regularization, and provide interpretable feature importance rankings, thereby enhancing the robustness and clinical relevance of our predictive model. Furthermore, this multicenter, large-sample survey encompassing 2,024 nursing students improves the generalizability and statistical power of our findings compared to single-center studies. Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference among the variables. Future cohort or longitudinal studies are warranted to explore causal relationships and dynamic changes in depression among nursing students over time. Second, although predictor variables were selected based on a literature review, their scope may be limited, and important psychological or contextual factors could have been omitted. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce recall or social desirability bias, and the geographical restriction of sampling may affect the extrapolation of results to other regions. Third, while this study ranked the importance of influencing factors, it did not explore potential interactions, mediating mechanisms, or specific pathways among variables. Although beyond the scope of this study, future research could address these aspects using methods such as path analysis or structural equation modeling. Nevertheless, future studies encountering more substantial missing data should employ more sophisticated methods, such as multiple imputation, to verify the robustness of their findings. The study utilized a convenience sample of nursing students from multiple universities. Due to the relatively homogeneous nature of this population, the generalizability of the findings to students of other majors or broader populations requires further verification. Finally, the results of our post hoc subgroup analyses are exploratory. Not corrected for multiple testing, and some subgroups may have had limited statistical power; therefore, these findings are hypothesis-generating and require cautious interpretation and external validation.

Conclusion

This study adopted the XG Boost model to analyze the depression-related factors of 2024 nursing students. The key factors include Sleep Condition, Social anxiety, Mother's Educational Level, and Sexual Orientation Smoking. And Household composition. These research results indicate that nursing educators regularly screen for depression among nursing students, consider implementing supportive measures, provide psychological counseling promptly, improve the risk factors for the occurrence of depression among nursing students, and reduce the occurrence of depression. Future studies should explore the effectiveness of these intervention measures and investigate other factors influencing depression among nursing students.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Studies involving human subjects were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Qilu Institute of Technology (Approval No. QIT-2024-0081). Patients/participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. We confirm that all the experiment is in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations such as the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YYL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BS: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YCL: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Construction and Practice of the “435 Nursing Curriculum System Based on the Concept of Life-Cycle Health Services (Shandong Province Undergraduate Teaching Reform Research Project M2023161)”.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1696139/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Organization WH . WHO highlights urgent need to transform mental health and mental health care (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

2

Wang C Chen H Shang S . Association between depression and lung function in college students. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1093935. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1093935

3

Dessauvagie AS Dang HM Nguyen TAT Groen G . Mental health of university students in southeastern asia: A systematic review. Asia Pac J Public Health. (2022) 34:172–81. doi: 10.1177/10105395211055545

4

Ching SSY Cheung K Hegney D Rees CS . Stressors and coping of nursing students in clinical placement: A qualitative study contextualizing their resilience and burnout. Nurse Educ Pract. (2020) 42:102690. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102690

5

Zheng YX Jiao JR Hao WN . Stress levels of nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e30547. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000030547

6

Jiang Z Jia X Tao R Dördüncü H . COVID-19: A source of stress and depression among university students and poor academic performance. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:898556. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.898556

7

Wang Y . Nursing students’ experiences of caring for dying patients and their families: a systematic review and meta-synthesis†. Front Nursing. (2019) 6:261–72. doi: 10.2478/FON-2019-0042

8

Mao Y Zhang N Liu J Zhu B He R Wang X . A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:327. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1744-2

9

Stubin CA Hargraves JD . Faculty supportive behaviors and nursing student mental health: a pilot study. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. (2022) 19. doi: 10.1515/ijnes-2022-0044

10

Kupcewicz E Mikla M Kadučáková H Grochans E Valcarcel MDR Cybulska AM . Correlation between positive orientation and control of anger, anxiety and depression in nursing students in Poland, Spain and Slovakia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:2482. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042482

11

Aloufi MA Jarden RJ Gerdtz MF Kapp S . Reducing stress, anxiety and depression in undergraduate nursing students: Systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. (2021) 102:104877. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104877

12

Tung YJ Lo KKH Ho RCM Tam WSW . Prevalence of depression among nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. (2018) 63:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.009

13

Zeng Y Wang G Xie C Hu X Reinhardt JD . Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety and symptoms of stress in vocational college nursing students from Sichuan, China: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Health Med. (2019) 24:798–811. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1574358

14

Curcio F de Pinho LG Rago C Bartoli D Pucciarelli G Avilés-González CI . Symptoms of anxiety and depression in italian nursing students: prevalence and predictors. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12:2154. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12212154

15

Alreshidi S Rayani A Aboshaiqah A Aljaloud A Ghulman S Alotibi A . Prevalence and associations of depression among saudi college nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12:1316. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12131316

16

Hakkal S Lahcen AA . XGBoost to enhance learner performance prediction. Comput Education: Artif Intelligence. (2024) 7:100254. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100254

17

Malakouti SM . Leveraging SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and fuzzy logic for efficient rainfall forecasts. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:36499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-22081-4

18

Ogundimu EO Altman DG Collins GS . Adequate sample size for developing prediction models is not simply related to events per variable. J Clin Epidemiol. (2016) 76:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.02.031

19

Ramón-Arbués E Gea-Caballero V Granada-López JM Juárez-Vela R Pellicer-García B Antón-Solanas I . The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress and their associated factors in college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7001. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197001

20

Ramón-Arbués E Sagarra-Romero L Echániz-Serrano E Granada-López JM Cobos-Rincón A Juárez-Vela R et al . Health-related behaviors and symptoms of anxiety and depression in Spanish nursing students: an observational study. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1265775. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1265775

21

Radloff LS . The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl psychol Measurement. (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

22

Blodgett JM Lachance CC Stubbs B Co M Wu YT Prina M et al . A systematic review of the latent structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) amongst adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:197. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03206-1

23

Niu L He J Cheng C Yi J Wang X Yao S . Factor structure and measurement invariance of the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale among undergraduates and clinical patients. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:463. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03474-x

24

Leary MR . Social anxiousness: the construct and its measurement. J Pers Assess. (1983) 47:66–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4701_8

25

Meijia L . Secondary vocational school students interpersonal trust, social anxiety status and their relationship. ChinaJournal Health Psychol. (2014) 22:1721–3. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2014.11.048

26

Ren L Wang Y Wu L Wei Z Cui LB Wei X et al . Network structure of depression and anxiety symptoms in Chinese female nursing students. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:279. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03276-1

27

Juan G Zhengwen P Annuo L Hongying Z Yan J Guiyue Z et al . A typical correlation analysis of anxiety, depression and professional adaptability among 799 undergraduate nursing students. J Nursing(China). (2020) 27:70–3. doi: 10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2020.02.070

28

Wenping J Hongyan Z Yinghan T Cheng Y Song W Yudong S et al . Association of depressive symptoms, Internet addiction and insomnia among medical students in Anhui Province. Chin J Sch Health. (2023) 44:1174–7+81. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2023.08.012

29

Lecheng C Yusha G Yujiao Y Xianhua W Dongmei Z Jishan W et al . Relationship among childhood trauma, parent-child attachment, resilience andDepressive symptoms of college students in wuhan. Acta Med Univ Sci Technol Huazhong. (2023) 52:54–9. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1672-0741.2023.01.010

30

Park H Lee KS . The association of family structure with health behavior, mental health, and perceived academic achievement among adolescents: a 2018 Korean nationally representative survey. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:510. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08655-z

31

Chaoyi Z Peirong G Jianping H Jie Y Qingyun L . Relationship between family structures and adolescents' mental health and health-associated behaviors. Chin JSch Health. (2023) 44:715–9.

32

Parikka S Mäki P Levälahti E Lehtinen-Jacks S Martelin T Laatikainen T . Associations between parental BMI, socioeconomic factors, family structure and overweight in Finnish children: a path model approach. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:271. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1548-1

33

Hong L Qiankun H Shengli T . Effects of family function and stress feeling on the mental health of adoleseents. Chin J Child Health Care. (2022) 30:1380–4. doi: 10.11852/zgetbjzz2021-1701

34

Chao T . The relationship between family factors and non-suicidal self-injury behaviorof adolescents with depressive disorder. Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (2022).

35

Bostwick WB Hughes TL Everett B . Health behavior, status, and outcomes among a community-based sample of lesbian and bisexual women. LGBT Health. (2015) 2:121–6. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0074

36

Marmorstein NR von Ranson KM Iacono WG Malone SM . Prospective associations between depressive symptoms and eating disorder symptoms among adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. (2008) 41:118–23. doi: 10.1002/eat.20477

37

Yin WL Changmian D Meng-lan G Li-qing W Chen-chang X Hong Y et al . Depression status and its influencing factors of lesbians in China. Chin J Dis Control Prev. (2021) 25:1393–7. doi: 10.16462/j.cnki.zhjbkz.2021.12.006

38

Roberts RE Duong HT . The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. Sleep. (2014) 37:239–44. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3388

39

Raudsepp L . Brief report: Problematic social media use and sleep disturbances are longitudinally associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents. J Adolesc. (2019) 76:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.005

40

Lippman S Gardener H Rundek T Seixas A Elkind MSV Sacco RL et al . Short sleep is associated with more depressive symptoms in a multi-ethnic cohort of older adults. Sleep Med. (2017) 40:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.09.019

41

Vriend JL Davidson FD Corkum PV Rusak B Chambers CT McLaughlin EN . Manipulating sleep duration alters emotional functioning and cognitive performance in children. J Pediatr Psychol. (2013) 38:1058–69. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst033

42

Zhang JC Yao W Hashimoto K . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-trkB signaling in inflammation-related depression and potential therapeutic targets. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2016) 14:721–31. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666160119094646

43

Schmitt K Holsboer-Trachsler E Eckert A . BDNF in sleep, insomnia, and sleep deprivation. Ann Med. (2016) 48:42–51. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1131327

44

Wang W Scott PW Kelly SH Sherwood PR . Factors associated with sleep quality among undergraduate nursing students during clinical practicums. Nurse Educ. (2024) 49:E175–e9. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001596

45

Wang Q Du W Wang H Geng P Sun Y Zhang J et al . Nicotine's effect on cognition, a friend or foe? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2023) 124:110723. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2023.110723

46

Bonevski B Regan T Paul C Baker AL Bisquera A . Associations between alcohol, smoking, socioeconomic status and comorbidities: evidence from the 45 and Up Study. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2014) 33:169–76. doi: 10.1111/dar.12104

47

Melamed OC Walsh SD Shulman S . Smoking behavior and symptoms of depression and anxiety among young adult backpackers: Results from a short longitudinal study. Scand J Psychol. (2021) 62:211–6. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12699

48

Ranjit A Buchwald J Latvala A Heikkilä K Tuulio-Henriksson A Rose RJ et al . Predictive association of smoking with depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study of adolescent twins. Prev Sci. (2019) 20:1021–30. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01020-6

49

Badrick E Kirschbaum C Kumari M . The relationship between smoking status and cortisol secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2007) 92:819–24. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2155

50

Demenescu LR Stan A Kortekaas R van der Wee NJ Veltman DJ Aleman A . On the connection between level of education and the neural circuitry of emotion perception. Front Hum Neurosci. (2014) 8:866. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00866

51

Li Z Fei L Ruan-he M . Influence of parental education level on anxiety emotion among middle school students. Chin JPublic Health. (2013) 29:1176–8.

52

Ghezelbash S Rahmani F Peyrovi H Inanlou M . Study of social anxiety in nursing students of tehran universities of medical sciences. Res Dev Med Education. (2015) 4:85–90. doi: 10.15171/rdme.2015.014

53

Flynn MK Bordieri MJ Berkout OV . Symptoms of social anxiety and depression: Acceptance of socially anxious thoughts and feelings as a moderator. J Contextual Behav Science. (2019) 11:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.12.002

54

Rose GM Tadi P . Social anxiety disorder. In: StatPearlsTreasure island (FL). StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025 StatPearls Publishing LLC (2025).

55

Nordahl H Nordahl HM Vogel PA Wells A . Explaining depression symptoms in patients with social anxiety disorder: Do maladaptive metacognitive beliefs play a role? Clin Psychol Psychother. (2018) 25:457–64. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2181

56

Juan H Yingge Z Xiaoyi F . Mobile phone addiction and Depression: The Multiple Mediating Effects of Social Anxiety and Negative Emotional Information Attention Bias. Acta Psychologica Sinica. (2021) 53:362–73.

57

Yüksel A Bahadir-Yilmaz E . Relationship between depression, anxiety, cognitive distortions, and psychological well-being among nursing students. Perspect Psychiatr Care. (2019) 55:690–6. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12404

58

Hon K Hamamura T Lim E Goh YSS . Nursing students' empathy in response to biological and psychosocial attributions of depression: A vignette-based cross-cultural study. Nurse Educ Today. (2024) 141:106309. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106309

59

Nway NC Phetrasuwan S Putdivarnichapong W Vongsirimas N . Factors contributing to depressive symptoms among undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Practice. (2023) 68:103587. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103587

60

Cañadas GR Membrive-Jiménez MJ Martos-Cabrera MB Albendín-García L Velando-Soriano A Cañadas-De la Fuente GA et al . Burnout and Professional Engagement during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Nursing Students without Clinical Experience: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:5144. doi: 10.3390/jcm12155144

Summary

Keywords

nursing students, depression, extreme gradient boosting, XGBoost, nursing education

Citation

Li Y, Sun B, Wu X and Li Y (2025) An explainable analysis of depression status and influencing factors among nursing students. Front. Psychiatry 16:1696139. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1696139

Received

31 August 2025

Revised

10 November 2025

Accepted

11 November 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Sawsan Abuhammad, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan

Reviewed by

Maria Efstathiou, University of Ioannina, Greece

Amat-Alkhaleq Mehrass, Thamar University, Yemen

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li, Sun, Wu and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanchun Li, liyanchun@qlmu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.