- Department of Nursing, Mianzhu People’s Hospital, Deyang, Sichuan, China

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is increasingly recognized as a systemic disorder associated with heightened risk of cognitive impairment, including mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. Epidemiological studies indicate COPD patients face a 1.74-fold higher risk of cognitive decline, with deficits predominantly affecting attention, memory, and executive functions, impairing daily living and increasing mortality risk. This review synthesizes factors linking COPD to cognitive impairment, including systemic inflammation (via proinflammatory cytokines and blood-brain barrier disruption), hypoxemia/hypercapnia (inducing oxidative stress and neuronal damage), acute exacerbations (exacerbating inflammation and persisting deficits), and comorbidities like obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), cerebral microbleeds, and depression. Smoking’s role remains paradoxical, with neurotoxicants potentially counteracted by nicotine’s neuroprotective effects. Assessment relies on neuropsychological tools (e.g., MoCA, MMSE), neurophysiological measures (P300 ERP), and neuroimaging, though limitations persist. Interventions focus on non-pharmacological strategies: pulmonary rehabilitation (improving cognition via enhanced cerebral perfusion), cognitive training (targeting memory/attention), and long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT, reducing decline in hypoxemic patients). Critical gaps include unclear mechanisms and the need for personalized interventions. Addressing these may improve clinical outcomes and quality of life in COPD patients.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a preventable and treatable respiratory disorder characterized by persistent, progressive airflow limitation. Beyond its primary pulmonary manifestations, COPD is increasingly recognized as a systemic disease associated with a spectrum of extrapulmonary comorbidities, including ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome. Among these, cognitive impairment has emerged as a significant and underappreciated extrapulmonary complication, drawing growing attention in recent clinical and research endeavors (1).

Epidemiological evidence consistently demonstrates that individuals with COPD face a substantially elevated risk of cognitive impairment compared to those without the disease (2). A longitudinal study involving 9,765 community-dwelling older adults in China revealed that the incidence of cognitive impairment over a 3-year follow-up was 21.7% in COPD patients, significantly higher than the 16.2% observed in their non-COPD counterparts (3). Furthermore, after adjusting for confounding variables such as age and educational attainment, COPD patients were found to have a 1.74-fold increased risk of developing cognitive impairment (4). The cognitive domains most frequently affected in COPD include attention, memory, and executive functions, which are pivotal for maintaining independent daily living.

In COPD, cognitive impairment primarily affects the domains of attention, memory, and executive function (5). Studies show that attention deficits are particularly prevalent in COPD patients, leading to difficulties in focusing and sustaining attention during daily activities. Memory problems, especially in working memory and episodic memory, are commonly observed, which significantly impact the ability to recall important information and perform tasks that require remembering sequences or details (6). Additionally, executive function, including skills like planning, problem-solving, and decision-making, is often impaired, particularly in more severe stages of COPD. These cognitive deficits, especially in attention, memory, and executive function, are associated with poorer functional outcomes, including increased dependence on others and a lower quality of life (7). In contrast, dementia is a syndrome marked by progressive, acquired cognitive decline that severely compromises daily living, learning, and social interaction capacities. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains the most extensively studied subtype of dementia (8).

The occurrence of cognitive impairment in COPD patients has profound clinical implications, including reduced self-care capacity, diminished quality of life, and increased risks of hospitalization and mortality (9). Given these adverse outcomes, early identification and assessment of cognitive function in COPD patients are of paramount importance to mitigate the risk of cognitive decline (10). However, the underlying mechanisms linking COPD to cognitive impairment remain incompletely elucidated (2). Although several reviews have explored the relationship between COPD and cognitive impairment, this review provides a more comprehensive analysis, integrating the latest research findings to delve into the multifactorial pathophysiological mechanisms of cognitive impairment in COPD patients. Furthermore, this review places particular emphasis on the application of non-pharmacological intervention strategies and offers specific recommendations that incorporate nursing practice, aiming to fill the gaps in the existing literature. This mini-review aims to synthesize current knowledge on the epidemiology, associated factors, and intervention strategies for cognitive impairment in COPD, with the goal of providing insights to inform clinical practice and improve patient outcomes.

Methods

This review systematically examined literature on cognitive impairment in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). We included peer-reviewed studies published in English that focused on the relationship between COPD and cognitive decline, particularly mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science using keywords such as “COPD,” “cognitive impairment,” “mild cognitive impairment,” “dementia,” “systemic inflammation,” and “interventions.

Inclusion criteria were (1): studies on adults aged 40+ with diagnosed COPD (2), studies investigating the impact of COPD on cognitive function, and (3) studies addressing both pathophysiological mechanisms and non-pharmacological interventions. Studies were excluded if they (1) did not focus on cognitive outcomes in COPD, (2) were not peer-reviewed, or (3) were not original research (e.g., reviews, editorials).

Eligible studies were assessed for relevance, quality, and methodology. Data were synthesized to provide an overview of the current state of research on COPD-related cognitive impairment, including contributing factors, assessment methods, and intervention strategies.

Factors associated with cognitive impairment in COPD patients

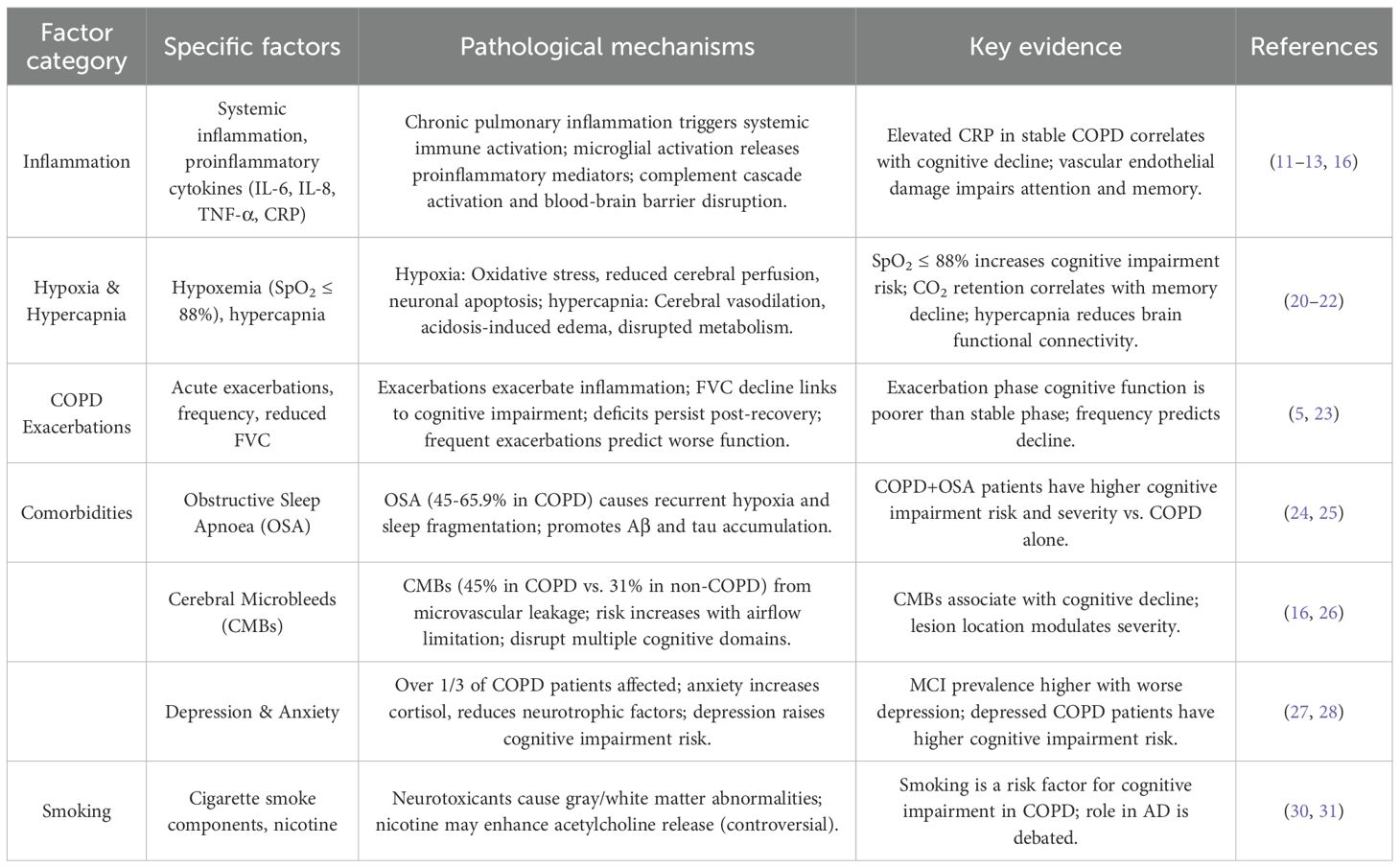

Cognitive impairment in COPD arises from a complex interplay of multiple factors, including inflammation, hypoxemia, hypercapnia, acute exacerbations, comorbidities (obstructive sleep apnoea, cerebral microbleeds, anxiety, and depression), and smoking (11).

Inflammation

Chronic pulmonary inflammation in COPD disrupts the balance between immune system-mediated damage and repair mechanisms (12). Inflammatory mediators from the airways enter systemic circulation, triggering a systemic inflammatory response that compromises the structure and function of extrapulmonary organs (13). This systemic inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment through mechanisms such as microglial activation, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, complement cascade activation, and blood-brain barrier disruption—processes also implicated in the development of AD (14, 15). Activated microglia release a spectrum of proinflammatory mediators, including neutrophils, macrophages, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), which collectively impair cognitive function (11). In stable COPD patients, elevated CRP levels—attributed to chronic inflammation—have been associated with cognitive decline, though no significant correlations between IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and cognitive performance have been identified. Long-term inflammatory stimulation damages vascular endothelium, disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity, and alters cerebrovascular structure, leading to impairments in attention and memory (16). These findings underscore inflammation as a key driver of cognitive impairment in COPD through multifaceted pathological pathways (17).

Hypoxemia and hypercapnia

Alveolar hypoventilation in COPD frequently results in hypoxemia and hypercapnia, both of which contribute to cognitive decline (18). Hypoxia induces oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, directly damaging neurons and reducing the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters involved in acetylcholine metabolism—critical for cognitive processes such as memory and attention (19). Sustained hypoxia also reduces cerebral perfusion, diminishes neuronal activity, and promotes neuronal apoptosis (20). Additionally, hypoxia-driven overproduction of reactive oxygen species exacerbates neuronal injury, further impairing cognitive function. A longitudinal study demonstrated that COPD patients with oxygen saturation ≤88% face a higher risk of cognitive impairment, highlighting the dose-dependent relationship between hypoxemia and cognitive decline (21).

Hypercapnia, often severe in advanced COPD (as indicated by higher GOLD stages), exerts deleterious effects on the central nervous system. Elevated carbon dioxide levels cause cerebral vasodilation, increasing cerebral blood volume and intracranial pressure, which exacerbates brain injury (22). Acidosis (secondary to hypercapnia) increases vascular permeability, leading to cerebral edema, while elevated cerebrospinal fluid H+ concentrations disrupt cellular metabolism and suppress cortical activity (20). Concomitant acidosis, edema, and hypoxia enhance glutamate decarboxylase activity in neurons, further impairing cellular function. Functional connectivity—assessed via resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging— is compromised in hypercapnic patients, representing a potential neurobiological substrate for cognitive decline. Moreover, the severity of carbon dioxide retention correlates with memory impairment, solidifying hypercapnia as an independent risk factor for cognitive dysfunction in COPD (22).

Acute exacerbations of COPD

Acute exacerbations of COPD—defined as acute worsening of respiratory symptoms beyond daily variability, requiring treatment adjustments—significantly impact cognitive function. The severity of COPD correlates with cognitive performance, with exacerbations mediating cognitive decline through heightened inflammation and reduced pulmonary function (23). Inflammatory markers inversely correlate with cognitive scores during exacerbations. Pulmonary function indices, particularly forced vital capacity (FVC), decline with increasing airflow limitation and strongly associate with cognitive impairment, whereas forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) shows no consistent relationship (5). A 3-month cohort study revealed that cognitive function is significantly poorer during exacerbations compared to stable phases, with deficits persisting even after clinical recovery (21). After adjusting for age, education, and smoking, frequent exacerbations independently predict cognitive decline, with higher exacerbation frequency correlating with more severe cognitive impairment, positioning exacerbation history as a prognostic indicator for cognitive outcomes in COPD.

Obstructive sleep apnoea

OSA is highly prevalent in COPD, with reported comorbidity rates ranging from 45% to 65.9% in clinical cohorts. OSA-induced recurrent nocturnal hypoxia and sleep fragmentation directly impair cognitive function, particularly memory (24). Sleep architecture disruption in OSA promotes pathological accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau proteins—hallmarks of AD—while increasing central nervous system oxidative stress and blood-brain barrier permeability. Cross-sectional studies demonstrate that COPD patients with comorbid OSA exhibit a higher risk and greater severity of cognitive impairment compared to those without OSA (25). Both OSA and COPD independently impair attention, memory, executive function, psychomotor speed, and language, with additive effects observed in comorbid patients, underscoring OSA as a critical modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline in COPD.

Cerebral microbleeds

CMBs—small, hemosiderin-laden lesions resulting from microvascular leakage—are a common cerebral small vessel disease in COPD. Longitudinal data indicate that 45% of COPD patients develop CMBs, compared to 31% of non-COPD individuals, with risk increasing alongside airflow limitation and dyspnea severity (16). CMBs disrupt multiple cognitive domains, including orientation, attention, calculation, and delayed recall, with the severity of cognitive impairment inversely correlating with lesion burden. The anatomical distribution of CMBs further modulates cognitive outcomes, with region-specific effects on memory and executive function (26). These findings establish CMBs as a key neurovascular mediator of cognitive decline in COPD.

Depression and anxiety

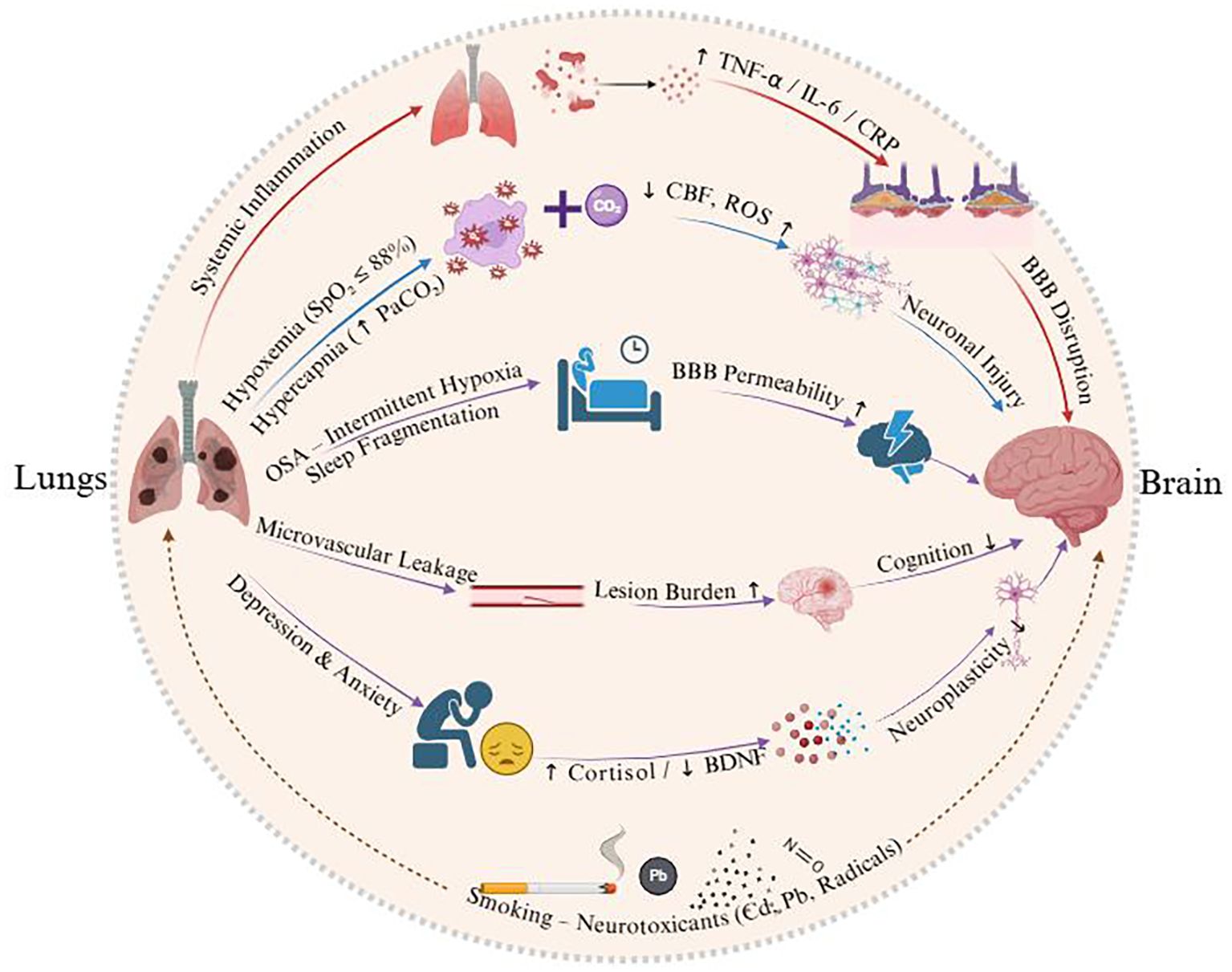

Over one-third of COPD patients experience comorbid depression and anxiety, which exacerbate cognitive impairment. Chronic respiratory dysfunction, physical inactivity, and social isolation in COPD contribute to negative affect, while anxiety-induced elevations in cortisol and reductions in brain-derived neurotrophic factor directly impair neuronal plasticity and cognitive performance (27). Epidemiological data show a stepwise increase in MCI prevalence with increasing depression severity: 10.0% in non-depressed patients, 13.3% in mild depression, and 19.7% in moderate-to-severe depression (28). Depressed COPD patients face a higher risk of cognitive impairment compared to their non-depressed counterparts, highlighting the bidirectional relationship between mood disorders and cognitive decline in COPD (29). Figure 1 illustrates the pathway by which COPD is linked to cognitive impairment through pulmonary dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and comorbid factors.

Figure 1. Schematic illustrating the pathways linking COPD to cognitive impairment via pulmonary dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and comorbid factors.

Smoking

Smoking is a dual risk factor for COPD and cognitive impairment, though its net effect remains contentious. Cigarette smoke contains neurotoxicants such as cadmium, nitric oxide, lead, and free radicals, which alter gray and white matter volumes and impair cognitive function. Observational studies identify smoking as a risk factor for cognitive impairment in COPD (30). Although nicotine—a constituent of tobacco—has been hypothesized to exert short-term neuroprotective effects by enhancing acetylcholine release and transiently improving attention or information processing (31), current large-scale cohort studies and meta-analyses indicate that these potential benefits are outweighed by the substantial neurovascular and oxidative harms of chronic smoking. Moreover, smoking cessation, rather than reduction, is associated with improved cognitive outcomes and reduced dementia risk in the general population and COPD cohorts (32). Therefore, the overall evidence supports that the detrimental effects of smoking on cognition far outweigh any transient or theoretical neuroprotective benefits of nicotine, underscoring the importance of smoking cessation as a critical preventive strategy for cognitive decline in COPD patients (33) (Table 1).

Pharmacotherapy-Related Factors

Medications used in COPD management may contribute to cognitive decline, as high anticholinergic burden is associated with an increased risk of dementia in older adults (34). Systemic corticosteroid use has also been linked to memory impairment and other cognitive deficits (35). Careful prescription using the lowest effective dose, shortest duration, and monitoring cumulative burden may help mitigate these risks.

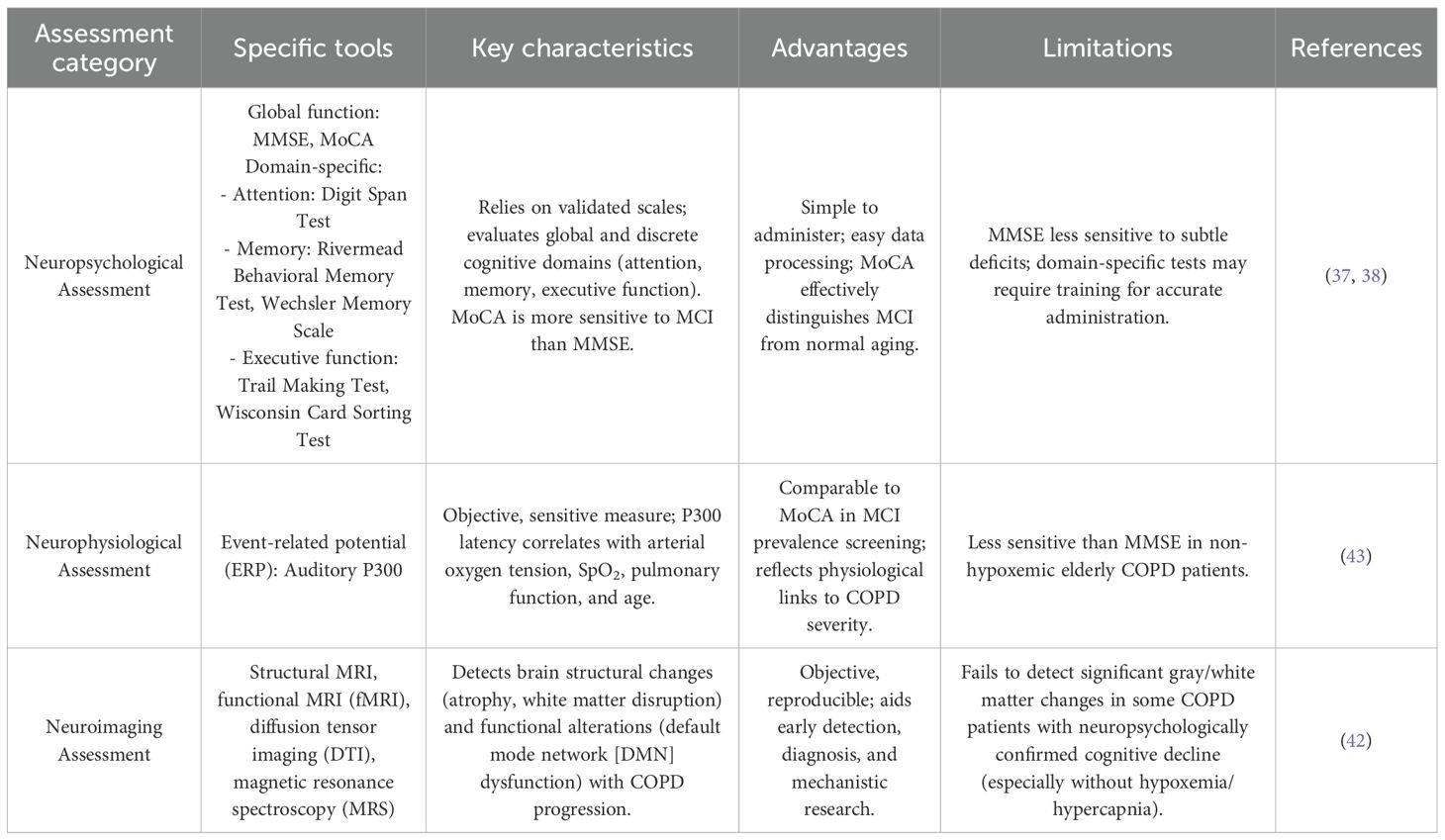

Assessment methods for MCI in COPD

The accurate evaluation of cognitive function in COPD patients with MCI is critical, given that their cognitive profiles may differ from those with age-related MCI (36). A comprehensive understanding of available assessment tools—encompassing neuropsychological, neurophysiological, and neuroimaging approaches—is essential to guide clinical practice and research.

Neuropsychological assessment

Neuropsychological tests, primarily relying on validated scales, are valued for their simplicity and ease of data processing. They are categorized into two main types:

1. Global cognitive function assessments: The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) are the most widely used. The MMSE, available in multiple language versions, remains a cornerstone for cognitive screening in clinical, research, and community settings due to its broad applicability (37). The MoCA, however, demonstrates superior sensitivity and specificity for detecting MCI, effectively distinguishing mild cognitive decline from normal age-related memory changes. For clinical interpretation, a score below 24/30 on the MMSE typically suggests cognitive impairment. The MoCA demonstrates superior sensitivity for detecting MCI, with a standard cut-off score of <26/30; one point is added for individuals with ≤12 years of education to correct for bias. Its enhanced ability to identify subtle deficits in executive function and visuospatial skills makes it more robust than the MMSE for early MCI detection (38).

2. Domain-specific assessments: These target discrete cognitive domains frequently impaired in COPD:

1. Attention: Tests such as the Digit Span Test (simple and widely used) consistently reveal lower scores in COPD patients compared to age-matched controls, indicating attention deficits (39).

2. Memory: The Wechsler Memory Scale (40), Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test (41), and Clinical Memory Scale assess memory function. The Rivermead scale is particularly useful for evaluating episodic memory and tracking changes in memory performance before and after interventions.

3. Executive function: The Trail Making Test and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test are validated tools. The Trail Making Test, with strong construct validity and test-retest reliability, is commonly employed for early screening of MCI in COPD due to its sensitivity to executive dysfunction (42).

Neurophysiological assessment

Neurophysiological methods offer objective, sensitive measures of cognitive function, with event-related potentials (ERPs) and evoked potentials being the primary modalities. The auditory ERP component P300 has emerged as a valuable adjunct in early MCI diagnosis (43). Its latency correlates with arterial oxygen tension, oxygen saturation, pulmonary function severity, and age, reflecting the interplay between systemic and cognitive impairment in COPD. While both MMSE and MoCA are useful for cognitive screening, previous studies generally suggest that MoCA shows higher sensitivity than MMSE in detecting mild cognitive impairment, including in COPD patients (44).

Neuroimaging assessment

Neuroimaging techniques, including structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy, provide objective, reproducible data to support early MCI detection, diagnosis, and mechanistic research. Structural MRI reveals progressive brain atrophy and white matter tract disruption with advancing COPD severity, while functional MRI identifies alterations in default mode network (DMN) connectivity—key neural substrates of cognitive function (42).

However, limitations exist: some COPD patients with overt cognitive deficits (documented via neuropsychological tests) show minimal changes in gray or white matter volume, particularly in the absence of hypoxemia or hypercapnia (45). This dissociation underscores the inability of current neuroimaging modalities to fully capture the neurobiological basis of cognitive impairment in COPD, emphasizing the need for multimodal assessment strategies.

Other assessment and evaluation methods

In addition to the neuropsychological and neurophysiological methods described above, other cognitive assessment tools and biomarkers are gaining attention in predicting the risk of MCI or dementia in COPD patients. For example, tools like the Clock Drawing Test (CDT) and Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination (ACE) are sensitive to subtle cognitive deficits in other populations, though studies in COPD patients are limited (46). These tools may require adaptation for COPD-specific cognitive profiles, including adjustments for education and COPD-related pathologies (e.g., hypoxemia, inflammation). Emerging biomarkers, such as amyloid-beta, tau imaging, and inflammatory markers like CRP and IL-6, may provide insight into cognitive decline mechanisms in COPD, but further research is needed to confirm their predictive value for MCI and dementia in COPD (47, 48). Digital health tools, such as CANTAB and wearable devices monitoring cognitive and physiological data, could offer real-time monitoring for early cognitive decline detection (49). These tools are still being evaluated but may become valuable for longitudinal tracking of cognitive changes in COPD. Given these promising directions, further large-scale, multi-center studies are needed to validate these tools’ effectiveness in predicting cognitive decline in COPD (Table 2).

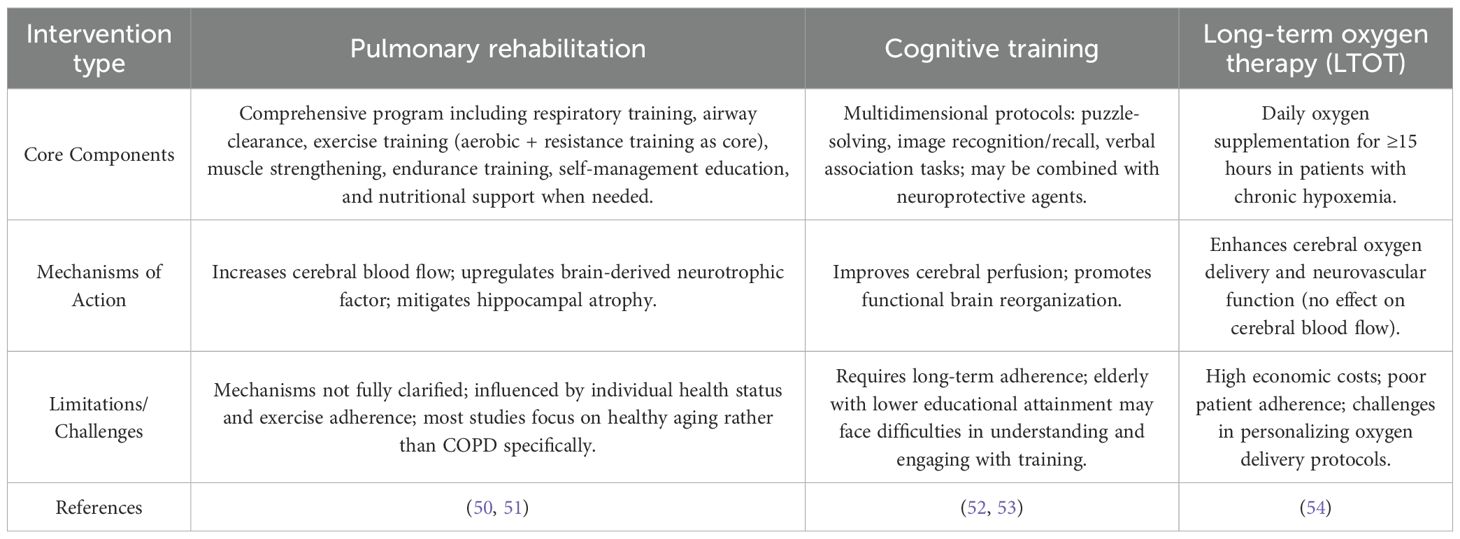

Intervention strategies for cognitive impairment in COPD

To date, no pharmacological agents have been specifically approved for treating cognitive impairment in COPD, making non-pharmacological interventions the mainstay of management. These strategies primarily include pulmonary rehabilitation, cognitive training, and long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), each with distinct mechanisms and clinical implications.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive, individualized intervention program developed following a thorough patient assessment, encompassing respiratory training, airway clearance techniques, and exercise training—with exercise as its core component (24). Mechanistic studies suggest that exercise exerts neuroprotective effects by increasing cerebral blood flow, upregulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and mitigating hippocampal atrophy, thereby reducing the risk of cognitive decline (50).

Clinical evidence supports its efficacy: combined aerobic and resistance training has been shown to significantly improve cognitive domains such as intelligence, attention, and reasoning in older COPD patients. A structured 8-week pulmonary rehabilitation program (3 sessions/week), incorporating respiratory exercises, muscle strengthening, endurance training, self-management education, and nutritional support when needed, not only acutely improves cognitive function in COPD patients with MCI but also maintains these benefits for up to 3 months post-intervention. However, the precise mechanisms linking exercise to cognitive enhancement in COPD remain incompletely understood, partly due to confounding variables such as individual health status and exercise adherence, and the paucity of studies focusing specifically on COPD rather than healthy aging populations (51).

Cognitive training

Cognitive training aims to enhance cognitive function by improving cerebral perfusion and promoting functional brain reorganization. Multidimensional training protocols—including puzzle-solving, image recognition and recall, and verbal association tasks—have demonstrated efficacy: a 12-week program (1 session/week) significantly improves global cognitive function, memory, attention, and spatial orientation in MCI patients (52). Additionally, combining cognitive training with neuroprotective agents (e.g., herbal extracts) has shown synergistic benefits in improving cognitive performance in COPD patients with cognitive impairment (53).

Challenges persist, however: long-term adherence is required for sustained benefits, and elderly individuals with lower educational attainment may face barriers in understanding and engaging with training protocols, necessitating tailored approaches to optimize compliance.

Long-term oxygen therapy

LTOT, defined as daily oxygen supplementation for ≥15 hours in patients with chronic hypoxemia, is a cornerstone of COPD management, with established benefits in improving survival. Its role in preserving cognitive function is increasingly recognized: LTOT reduces the risk of cognitive impairment in hypoxemic COPD patients. A randomized controlled trial comparing 45 COPD patients with and without LTOT demonstrated significantly worse cognitive outcomes in the non-oxygenated group, confirming a protective effect (54). Mechanistically, while LTOT does not alter cerebral blood flow, it enhances cerebral oxygen delivery and neurovascular function—key pathways linking oxygen supplementation to reduced risks of stroke, MCI, and dementia.

Despite its efficacy, LTOT is limited by high economic costs, poor patient adherence, and challenges in personalizing oxygen delivery protocols, highlighting the need for strategies to optimize its implementation in clinical practice.

Nursing role in non-pharmacological interventions

Nurses are essential in implementing non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive impairment in COPD patients. Pulmonary rehabilitation, for example, often requires nursing support in educating patients about the benefits of physical activity and monitoring exercise regimens (55). Nurses can provide tailored guidance based on the patient’s physical and cognitive abilities (56). Cognitive training programs, designed to target memory and attention, can be integrated into routine nursing care, with nurses offering structured sessions and feedback (57). Nurses also assist in managing LTOT by ensuring proper adherence, adjusting oxygen levels as needed, and providing emotional support to patients (58). In addition, nurses integrate behavioral and psychosocial interventions, such as motivational interviewing, psychoeducation for emotional symptoms, and managing treatment plans. Involving caregivers and family members in the patient’s care process improves the effectiveness and long-term success of these interventions. The nursing team plays an integral role in enhancing self-management skills and maintaining patient motivation, ensuring that these interventions are both effective and sustainable (Table 3).

Table 3. Non-pharmacological intervention strategies for cognitive impairment in COPD: core components, mechanisms, and limitations.

CPAP therapy for OSA in COPD patients

For COPD patients with comorbid obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) who do not require long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) therapy has proven beneficial in reducing cognitive impairment (59). CPAP treatment, especially when used for over 4 hours per night, alleviates the intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation characteristic of OSA (60). This has been shown to significantly improve cognitive performance, particularly in domains such as memory, attention, and executive function. Studies have demonstrated that CPAP can enhance the quality of life by improving sleep quality, reducing daytime sleepiness, and protecting against cognitive decline, even in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia associated with OSA (61).

Conclusion

COPD is strongly associated with an elevated risk of cognitive impairment, encompassing MCI and, in severe cases, progression to dementia. This relationship is driven by a complex interplay of pathological factors: systemic inflammation—mediated by proinflammatory cytokines, microglial activation, and blood-brain barrier disruption—contributes to neurocognitive decline, while hypoxemia and hypercapnia induce oxidative stress, neuronal damage, and functional brain connectivity deficits. Acute exacerbations of COPD further exacerbate cognitive impairment, with frequent exacerbations serving as a reliable predictor of poorer cognitive outcomes, likely through amplified inflammation and reduced pulmonary function (notably forced vital capacity). Comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), cerebral microbleeds, and mood disorders (anxiety and depression) synergistically increase cognitive risk, while smoking exerts dual, poorly understood effects—neurotoxicity via heavy metals and free radicals versus potential neuroprotective properties of nicotine.

Current interventions for cognitive impairment in COPD focus on non-pharmacological strategies. Pulmonary rehabilitation, incorporating aerobic and resistance training, enhances cognitive domains such as attention and executive function through increased cerebral perfusion and neurotrophic factor upregulation, with benefits sustained post-intervention. Cognitive training, via structured tasks targeting memory and reasoning, promotes functional brain reorganization, though long-term adherence and accessibility for elderly patients with limited education remain challenges. LTOT reduces cognitive decline risk in hypoxemic patients by improving cerebral oxygen delivery and neurovascular function, despite barriers of cost and adherence.

Nursing care plays a pivotal role in the management of cognitive impairment in COPD patients. Nurses are at the forefront of monitoring cognitive function, using tools such as the MoCA and MMSE for early detection. They are also critical in implementing non-pharmacological interventions, including pulmonary rehabilitation, cognitive training, and ensuring proper adherence to LTOT. Through their ongoing interaction with patients, nurses provide essential education, emotional support, and motivation, which are key to enhancing self-management and sustaining the benefits of these interventions.

Although several studies have explored the relationship between COPD and cognitive impairment, there are some limitations in the existing research. Some studies have small sample sizes and fail to account for multiple comorbidities, affecting the generalizability and reliability of the results. Additionally, most studies focus on individual factors, such as hypoxemia or inflammation, without a comprehensive analysis of how these factors interact. And the precise mechanisms linking COPD to cognitive impairment require clarification, and optimized, personalized interventions—addressing variability in patient adherence, comorbidity profiles, and disease severity—are needed. Further research into the neurobiological substrates of COPD-related cognitive decline and the development of targeted, scalable interventions will be pivotal to mitigating cognitive risk, enhancing self-care capacity, and reducing the disease burden for COPD patients. Additionally, further nursing research is needed to explore tailored interventions that can improve cognitive outcomes, enhance self-management, and ultimately improve quality of life for COPD patients.

Author contributions

YJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Wang J, Li X, Lei S, Zhang D, Zhang S, Zhang H, et al. Risk of dementia or cognitive impairment in COPD patients: A meta-analysis of cohort studies, Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:962562. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.962562

2. Simargi Y, Mansyur M, Turana Y, Harahap AR, Ramli Y, Siste K, et al. Risk of developing cognitive impairment on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Medicine. (2022) 101:e29235 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029235

3. Yin P, Ma Q, Wang L, Lin P, Zhang M, Qi S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment in the Chinese elderly population: a large national survey. Int J Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Dis. (2016) 11:399–406. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S96237

4. Zu B, Wang N, Fan L, Huang J, Zhang Y, Tang M, et al. Cognitive impairment influencing factors in the middle-aged and elderly population in China: Evidence from a National Longitudinal Cohort Study. PloS One. (2025) 20:e0324130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324130

5. Siraj RA. Comorbid cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): current understanding, risk factors, implications for clinical practice, and suggested interventions. Med (Kaunas Lithuania). (2023) 59:732. doi: 10.3390/medicina59040732

6. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment–beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. (2004) 256:240–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x

7. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, and Fratiglioni L. Introduction: Mild cognitive impairment: beyond controversies, towards a consensus. J Intern Med. (2004) 256:181–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01382.x

8. Querfurth HW and LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. New Engl J Med. (2010) 362:329–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142

9. Wang T, Mao L, Wang J, Li P, Liu X, and Wu W. Influencing factors and exercise intervention of cognitive impairment in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Interventions aging. (2020) 15:557–66. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S245147

10. Higbee DH and Dodd JW. Cognitive impairment in COPD: an often overlooked co-morbidity. Expert Rev Respir Med. (2021) 15:9–11. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1811090

11. Dodd JW, Getov SV, and Jones PW. Cognitive function in COPD. Eur Respir J. (2010) 35:913–22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00125109

12. von Siemens SM, Perneczky R, Vogelmeier CF, Behr J, Kauffmann-Guerrero D, Alter P, et al. The association of cognitive functioning as measured by the DemTect with functional and clinical characteristics of COPD: results from the COSYCONET cohort. Respir Res. (2019) 20:257. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1217-5

13. Gao C, Jiang J, Tan Y, and Chen S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2023) 8:359. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01588-0

14. Bayraktaroglu I, Ortí-Casañ N, Van Dam D, De Deyn PP, and Eisel ULM. Systemic inflammation as a central player in the initiation and development of Alzheimer’s disease. Immun Ageing. (2025) 22:33. doi: 10.1186/s12979-025-00529-5

15. Ebrahimi R, Shahrokhi Nejad S, Falah Tafti M, Karimi Z, Sadr SR, Ramadhan Hussein D, et al. Microglial activation as a hallmark of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Metab Brain Disease. (2025) 40:207. doi: 10.1007/s11011-025-01631-9

16. Lahousse L, Vernooij MW, Darweesh SKL, Akoudad S, Loth DW, Joos GF, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cerebral microbleeds. Rotterdam Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2013) 188:783–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0455OC

17. Miao J, Ma H, Yang Y, Liao Y, Lin C, Zheng J, et al. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease: pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic potentials. Front Aging Neurosci. (2023) 15:1201982. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1201982

18. Dobric A, De Luca SN, Spencer SJ, Bozinovski S, Saling MM, McDonald CF, et al. Novel pharmacological strategies to treat cognitive dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Ther. (2022) 233:108017. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.108017

19. Areza-Fegyveres R, Kairalla RA, Carvalho CRR, and Nitrini R. Cognition and chronic hypoxia in pulmonary diseases. Dementia neuropsychologia. (2010) 4:14–22. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642010DN40100003

20. Yu X, Xiao H, Liu Y, Dong Z, Meng X, and Wang F. The lung-brain axis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-associated neurocognitive dysfunction: mechanistic insights and potential therapeutic options. Int J Biol Sci. (2025) 21:3461–77. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.109261

21. Chen X, Yu Z, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Li S, and Wang L. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respir Res. (2024) 11. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2023-001709

22. Beaudin AE, Raneri JK, Ayas NT, Skomro RP, Smith EE, and Hanly PJ. Contribution of hypercapnia to cognitive impairment in severe sleep-disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med. (2022) 18:245–54. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9558

23. Mermit Çilingir B, Günbatar H, and Çilingir V. Cognitive dysfunction among patients in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Effects of exacerbation and long-term oxygen therapy. Clin Respir J. (2020) 14:1137–43. doi: 10.1111/crj.13250

24. Alharbi AM, Alotaibi N, Uysal ÖF, Rakhit RD, Brill SE, Hurst JR, et al. Cognitive outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/OSA overlap syndrome compared to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) alone: a systematic review. Sleep breathing = Schlaf Atmung. (2025) 29:275. doi: 10.1007/s11325-025-03426-9

25. Olaithe M, Pushpanathan M, Hillman D, Eastwood PR, Hunter M, Skinner T, et al. Cognitive profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: a cluster analysis in sleep clinic and community samples. J Clin Sleep Med. (2020) 16:1493–505. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8564

26. Badr MY, Elkholy AA, Shoeib SM, Bahey MG, Mohamed EA, and Reda AM. Assessment of incidence of cerebral vascular diseases and prediction of stroke risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients using multimodal biomarkers. Clin Respir J. (2023) 17:211–28. doi: 10.1111/crj.13587

27. Peiffer G, Underner M, Perriot J, and Fond G. COPD, anxiety-depression and cognitive disorders: Does inflammation play a major role]? Rev Des maladies respiratoires. (2021) 38:357–71. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2021.03.004

28. Martínez-Gestoso S, García-Sanz M-T, Carreira J-M, Salgado F-J, Calvo-Álvarez U, Doval-Oubiña L, et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on the prognosis of copd exacerbations. BMC Pulmonary Med. (2022) 22:169. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-01934-y

29. Yohannes AM, Murri MB, Hanania NA, Regan EA, Iyer A, Bhatt SP, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with COPD: A network analysis. Respir Med. (2022) 198:106865. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106865

30. Zeng F, Hong W, Zha R, Li Y, Jin C, Liu Y, et al. Smoking related attention alteration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-smoking comorbidity. BMC Pulm Med. (2022) 22:182. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-01964-6

31. Calakos KC, Hillmer AT, Anderson JM, LeVasseur B, Baldassarri SR, Angarita GA, et al. Cholinergic system adaptations are associated with cognitive function in people recently abstinent from smoking: a (-)-[(18)F]flubatine PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology: Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. (2023) 48:683–9. doi: 10.1038/s41386-023-01535-1

32. Green HJ, O’Shea OK, Cotter J, Philpott HL, and Newland N. An exploratory, randomised, crossover study to investigate the effect of nicotine on cognitive function in healthy adult smokers who use an electronic cigarette after a period of smoking abstinence. Harm Reduction J. (2024) 21:78. doi: 10.1186/s12954-024-00993-0

33. Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, Costafreda SG, Selbæk G, Alladi S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet. (2024) 404:572–628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0

34. Coupland CAC, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R, Moore M, and Hippisley-Cox J. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the risk of dementia: A nested case-control study. JAMA Internal Med. (2019) 179:1084–93. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0677

35. Prado CE and Crowe SF. Corticosteroids and cognition: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Review. (2019) 29:288–312. doi: 10.1007/s11065-019-09405-8

36. Torres-Sánchez I, Rodríguez-Alzueta E, Cabrera-Martos I, López-Torres I, Moreno-Ramírez MP, and Valenza MC. Cognitive impairment in COPD: a systematic review. Jornal Brasileiro Pneumologia. (2015) 41. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132015000004424

37. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatrics Society. (2005) 53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

38. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, and McHugh PR. Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. (1975) 12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

39. Kendig H, Byles JE, O’Loughlin K, Nazroo JY, Mishra G, Noone J, et al. Adapting data collection methods in the Australian Life Histories and Health Survey: a retrospective life course study. BMJ Open. (2014) 4:e004476. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004476

40. Chlebowski C. Wechsler memory scale all versions. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, and Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. Springer New York, New York, NY (2011). p. 2688–90.

41. Kurtz MM. Rivermead behavioral memory test. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, and Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. Springer New York, New York, NY (2011). p. 2184–5.

42. Pastuch-Gawołek G, Malarz K, Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz A, Musioł M, Serda M, Czaplinska B, et al. Small molecule glycoconjugates with anticancer activity. Eur J medicinal Chem. (2016) 112:130–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.061

43. Patti F, Ciancio MR, Cacopardo M, Reggio E, Fiorilla T, Palermo F, et al. Effects of a short outpatient rehabilitation treatment on disability of multiple sclerosis patients–a randomised controlled trial. J neurology. (2003) 250:861–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1097-x

44. Jia X, Wang Z, Huang F, Su C, Du W, Jiang H, et al. A comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:485. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03495-6

45. He M, Liu Y, Guan Z, Li C, and Zhang Z. Neuroimaging insights into lung disease-related brain changes: from structure to function. Front Aging Neurosci. (2025) 17. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1550319

46. Panda S, Freedman M, and Abdellah E. Clock drawing as a tool for diagnosis of dementia and mild cognitive impairment a retrospective chart review study. J Neurological Sci. (2023) 455. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2023.121436

47. Rowley PA, Samsonov AA, Betthauser TJ, Pirasteh A, Johnson SC, and Eisenmenger LB. Amyloid and tau PET imaging of alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative conditions. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. (2020) 41:572–83. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2020.08.011

48. Mekhora C, Lamport DJ, and Spencer JPE. An overview of the relationship between inflammation and cognitive function in humans, molecular pathways and the impact of nutraceuticals. Neurochemistry Int. (2024) 181:105900. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2024.105900

49. Coutu F-A, Iorio OC, and Ross BA. Remote patient monitoring strategies and wearable technology in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Med. (2023) 10. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1236598

50. Bahrami-Ahmadi A, Mortazavi SA, Soleimani R, and Nassiri-Kashani MH. The effect of work- related stress on development of neck and shoulder complaints among nurses in one tertiary hospital in Iran. Med J Islamic Republic Iran. (2016) 30:471.

51. Park SY and Kim IS. Stabilin receptors: role as phosphatidylserine receptors. Biomolecules. (2019) 9. doi: 10.3390/biom9080387

52. Chen S and Bell SP. CDK prevents Mcm2–7 helicase loading by inhibiting Cdt1 interaction with Orc6. Genes Dev. (2011) 25:363–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.2011511

53. Barnett ML and Huskamp HA. Telemedicine for mental health in the United States: making progress, still a long way to go. Psychiatr Serv (Washington DC). (2020) 71:197–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900555

54. Ridley PD and Braimbridge MV. Thoracoscopic debridement and pleural irrigation in the management of empyema thoracis. Ann Thorac surgery. (1991) 51:461–4. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)90866-O

55. Aranburu Imatz A, López-Carrasco J, Moreno-Luque A, Jiménez-Pastor J, Valverde-León M, Rodríguez Cortés F, et al. Nurse-led interventions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:9101. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159101

56. Zhang M, Mao X, Li F, and Xianyu Y. The effects of nurse-led family pulmonary rehabilitation intervention on quality of life and exercise capacity in rural patients with COPD. Wiley. (2023) 10:5606–15. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1804

57. Salvado S, Grilo E, Henriques H, Ferraz I, Gaspar F, and Baixinho C. Pulmonary rehabilitation nursing interventions promoting self-care in elderly people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (At home). Healthcare. (2025) 13:2176. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13172176

58. Morris JR, Harrison SL, Robinson J, Martin D, and Avery L. Non-pharmacological and non-invasive interventions for chronic pain in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review without meta-analysis. Respir Med. (2023) 211:107191. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107191

59. Jiang X, Wang Z, Hu N, Yang Y, Xiong R, and Fu Z. Cognition effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure treatment in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients with cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Exp Brain Res. (2021) 239:3537–52. doi: 10.1007/s00221-021-06225-2

60. Benkirane O, Mairesse O, and Peigneux P. Impact of CPAP therapy on cognition and fatigue in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea: A longitudinal observational study. Clocks Sleep. (2024) 6:789–816. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep6040051

Keywords: COPD, cognitive impairment, associated factors, intervention strategies, systemic inflammation

Citation: Jing Y and Mao S (2026) COPD and cognitive impairment: a review of associated factors and intervention strategies. Front. Psychiatry 16:1714708. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1714708

Received: 28 September 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 18 November 2025;

Published: 19 January 2026.

Edited by:

Ephrem Tesfaye Mihretie, Madda Walabu University, EthiopiaReviewed by:

Suikriti Sharma, Himalayan Pharmacy Institute, IndiaAhmed Ezzat, Sohag University, Egypt

Pedro Emanuel Alexandre-Sousa, Escola Superior de Saúde - Politécnico de Leiria ESSLEI, Portugal

Copyright © 2026 Jing and Mao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuling Jing, eXVsaW5najQyM0AxNjMuY29t

Yuling Jing

Yuling Jing Shuixiang Mao

Shuixiang Mao