Abstract

Introduction:

Repetitive head impacts may contribute to long-term neurological disorders, including chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and mental health decline often precedes cognitive symptoms. Adolescent athletes are especially vulnerable, yet prospective data on mental health trajectory across high school athletic career are limited.

Aim:

To examine the mental health changes of high school football players across multiple seasons of participation.

Methods:

This prospective cohort study included 6 high schools across southern Indiana for 4 consecutive seasons from July 2021 to February 2025. Participants included male high school football players and noncontact athletes (ages 13-18) in tennis, cross-country, and swimming. Sensor installed mouthguards were utilized to measure head impacts and surveys were conducted pre and post season to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Results:

A total of 371 adolescent athletes participated in this longitudinal study, including 275 high school football players (mean [SD] age, 15.3 [1.2] years) and 96 non-contact control athletes (mean [SD] age, 15.9 [1.2] years), with varying lengths of participation across 4 years of study. Depression and anxiety symptoms remained consistent across 1 season (pre vs. postseason) in both groups, as illustrated by non-significant group by time interaction in PHQ-9 [b=-0.11, 95%CI(-0.98, 0.76), p=0.814] or GAD-7 [b=0.09, 95%CI(-0.62, 0.79), p=0.806]. The same pattern was observed for those who participated in 2 consecutive seasons [PHQ-9 b=-0.01, 95%CI (-0.96, 0.98), p=0.980; GAD-7 b=0.42, 95%CI(-0.43, 1.27), p=0.33]. However, among those with 3 consecutive years of participation, there was significant seasons (pre vs. post) by year (1st vs. 3rd year) interaction in depression symptoms in the football group [PHQ-9: b=1.50, 95%CI (0.32, 2.66), p=0.015], a pattern not observed in the control group.

Discussion:

Our data suggest that mental health wellbeing remain consistent across 1 to 2 years of high school sports participation, regardless of head impact exposure or types of sports they play (football or non-contact sports). However, psychological burden may accumulate over multiple years of football participation.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the potential link between repetitive head impacts and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has become a central topic in neurotrauma research and public discussion. This concern is particularly prominent in American football, where players may endure hundreds of head impacts each season, including both concussive and subconcussive head impacts (1, 2). While a concussion elicits a range of physical, mental, and cognitive symptoms, even asymptomatic head impacts can leave a biological footprint, including elevated brain-injury blood biomarkers (3–5), impairments in sensorimotor function (3, 6), and axonal microstructural damage (7, 8). While prospective longitudinal data remain scarce, retrospective research suggests that neurobiological consequences may accumulate over years of head impact exposure (9, 10). Historically, CTE research has focused on middle-aged and older adults; however, emerging evidence indicates that neurodegeneration may begin as early as in adolescence. Autopsy studies of young adults and teenagers exposed to repetitive head impacts (RHI) have identified early signs of tau tangles and neuroinflammation (11). As mental health changes often precede cognitive decline in CTE (10, 11), tracking psychological wellbeing throughout a high school football career is critical for understanding early disease progression.

The impact of concussion on mental health has been extensively studied. For example, a large-scale cohort study by Ledoux et al. (12) reported that 152, 321 children and youths with a concussion (median age: 13 years) had a 1.4-fold higher incidences of mental health disorders (e.g., anxiety, neurotic, mood disorders), self-harm, and psychiatric hospitalization compared to orthopedic injury controls (12). Furthermore, teenagers who sustain concussion are at a 3-fold increased risk of developing depression within 6 months of injury (13), and suicide attempts in high schoolers are higher among those with more than 2 concussion history (14). Such findings highlight the long-lasting mental health effects of concussion on the developing brain.

Beyond the risks of concussion, contact sport athletes experience hundreds of subconcussive head impacts, defined as impacts that do not produce overt symptoms. Using a decade of head impact sensor data, Montenigro et al. (15) demonstrated that exceeding a cumulative threshold of 1, 801 head impacts is associated with a linear, dose-dependent increase in the risk of developing depression among former high school and college football players. Moreover, a recent study of middle-aged adults with at least 10 years of contact or non-contact sport participation revealed elevated symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the contact sports group compared to the non-contact controls (16). The contact group was 2.25 times more likely to receive mental health disorder diagnoses and 1.29 times more likely to use related medications (16). However, contradictory findings exist. For example, Iverson et al. (17) reported no differences in lifetime diagnosis of depression, anxiety, panic disorders, or suicidal ideation between former high school football players and age-matched controls (17). While these studies offer valuable insights into the relationship between head impacts and mental health, many are limited by cross-sectional designs, proxy measures of cumulative head impact exposure, and reliance on diagnostic categories rather than detailed symptom scores.

These limitations underscore the need for prospective studies to clarify the temporal relationship between RHI and mental health outcomes. Our previous pilot study by Kercher et al. (18) took an initial step toward addressing this gap, reporting no significant changes in depression or anxiety scores over a single high school football season, nor any correlation between mental health outcomes and head impact kinematics measured via sensor-installed mouthguards. However, a key question remains: does mental health remain stable across multiple seasons, or does it decline with prolonged exposure to RHI?

This multisite, longitudinal cohort study spanning 4 years aimed to characterize the trajectory of mental health changes among high school football players and examine the potential modulatory role of RHI on mental health outcomes. The study was guided by two primary objectives: (1) to replicate our pilot findings by assessing mental health wellbeing over a single football season and (2) to evaluate whether the magnitude of pre- to post-season changes in depression and anxiety symptoms differs following two or three consecutive years of football participation. We hypothesized that depression and anxiety scores would remain stable across a single football season, with no significant differences between football players and non-contact sport controls. Furthermore, multiple seasons of football participation would be associated with a progressive decline in mental health among adolescent football players.

Materials and methods

Participants

This multisite, longitudinal cohort study, spanned across 4 academic school years, from July 2021 to February 2025. It included 373 adolescent male athletes, 275 football players and 98 noncontact sport athletes from across 6 high schools in the Midwest. Inclusion criteria consisted of being an active football or noncontact athlete (swimming, cross-country, and tennis), between the ages of 13 and 18, and willing to wear a sensor-installed mouthguard. Exclusion criteria included a history of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and moderate TBI/concussion with symptoms present in the past 6 months. All participants and legal guardians signed consent forms prior to each year of participation. Approval was obtained from the district school board and school stakeholders, and Indiana University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (1904461516).

Study procedures

During preseason baseline, participants completed an online questionnaire that captured demographic information, contact sport history, football-specific context, concussion history, and mental health diagnosis. Prior to each season, football participants were fitted with a sensor-installed mouthguards (Prevent Biometrics, Inc.) and wore them for all practices, scrimmages, and games until the conclusion of their season. Mental health questionnaires were administered in-person, in the presence of research staff, at both pre- and post-season each year for both football and control athletes.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess self-reported depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 consists of 9 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3), where 0 indicates “not at all”, and 3 indicates experiencing the symptom “nearly every day”. A total score ranges from 0 to 27, and higher scores represent worse depressive symptom (19). Among adolescents, the PHQ-9 has demonstrated strong internal consistency with a Chronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.82, alongside a sensitivity of 89.5% and a specificity of 77.5% for detecting youth with major depressive disorder (20).

Anxiety symptoms

The General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) is a self-administered questionnaire that assesses worry and anxiety symptoms. The GAD-7 consists of 7 questions with a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3), where 0 indicates “not at all”, and 3 indicates experiencing the symptom “nearly every day”. Total scores range from 0 to 21 with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety severity (21). In adolescents, the GAD-7 has shown a strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.91) and adequate construct validity (22).

Head impacts

This study employed the Prevent Biometrics Instrumented Mouthguard (IMM) system, which integrates a triaxial accelerometer (ADXL372) and gyroscope (BMG250) to capture six degrees of freedom in head kinematics, including both linear and rotational accelerations. When acceleration along any axis exceeds a preset threshold (5–15 g), the device initiates data recording. Each event is processed by the mouthguard’s onboard firmware and transmitted via Bluetooth to a mobile application, which subsequently uploads the encrypted data to a secure, cloud-based server. The system samples at 3.2 kHz and records 50 ms of data per event. The mouthguard’s internal memory can store up to approximately 460 impacts and contains sensors that verify proper fit and use during athletic activity. For the present analyses, only head impacts with peak linear acceleration greater than 10 g were retained to minimize inclusion of non-impact movements such as jumping or running (23, 24). Research equipment managers were onsite during every practice and game to ensure the deployment of mouthguards, sanitation, charging of mouthguards, and synching impact data. Given the significant correlations (r<0.90, p<0.0001) among head impact counts, cumulative peak linear acceleration (g), and cumulative peak rotational acceleration (krad/s2), we chose head impact counts as our predictor in the analyses. The film validation of a randomly selected 1, 785 head impacts resulted in 94% (n=1, 670) of agreement between mouthguard data and film analysis (25).

Statistical analysis

Group differences (football or control) in demographic variables were assessed with two-tailed independent samples t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squares for categorical variables. To examine changes in mental health outcomes across one season, we conducted mixed-effects regression (MRM) models on the primary outcome of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores. The primary (fixed-effect) factor was timepoint (pre- vs. post-season), group (football vs. control), and the group-by-time-interaction. Participants were treated as a random effect to account for individual differences. The model accounted for repeated measures from the same participant and included covariates of age, number of concussions, a binary variable representing if they had a mental health diagnosis (0=no diagnosis, 1=mental health diagnosis), BMI, and race. The secondary analysis focused on the football group, evaluating changes in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores across second or third consecutive seasons. Fixed effects included timepoint (pre- vs post-season) and season (first vs. second; first vs. third seasons), with the same covariates from the primary analysis. As part of a sensitivity analysis, identical MRMs were run for control athletes to determine whether observed trends were specific to football participation. Analysis for each model was summarized by providing a contrast estimate with its 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value in the following format (b estimate [95% CI, low CI, high CI], p-value). The significance level for all tests was set to 0.05. Post-hoc analyses were conducted using marginal means to examine group differences when necessary. All analyses were conducted using R, version 4.4.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing) using packages nlme and emmeans.

Results

Demographics

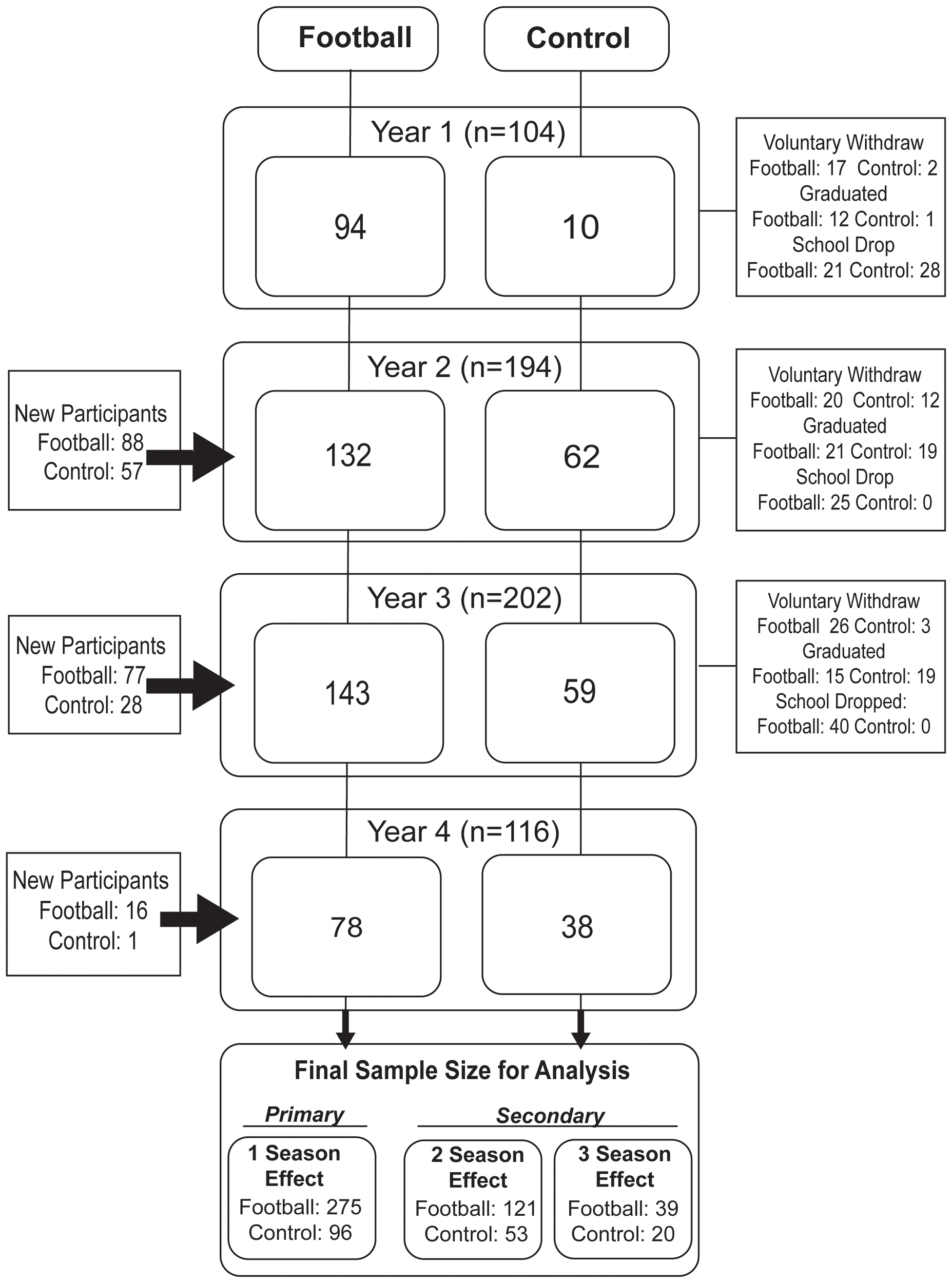

A total of 371 adolescent athletes participated in the study, including 275 high school football players (mean [SD] age, 15.3 [1.2] years) and 96 non-contact control athletes (mean [SD] age, 15.9 [1.2] years) throughout 4 years of study. Participants completed varied durations of the study (Figure 1). Sample sizes contributed to our analyses were: 1st season (n=275 football, n=96 control), 2 consecutive seasons (n=121 football, n=53 control), and 3 consecutive seasons (n=39 football, n=20 control). Given the limited sample size participating in the 4 consecutive seasons, their data up to 3 seasons were included in the analyses. Football players were slightly younger, had a higher body mass index (BMI), and more racially diverse than the control athletes. See Table 1 for demographics.

Figure 1

Study flow chart.

Table 1

| Group | Football | Control | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 275 | 96 | – |

| Sex (%) | 275 (100) | 96 (100) | – |

| Age, y | 15.3 (1.2) | 15.9 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD) | 25.9 (6.0) | 20.7 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| No. of previous concussion | 0.08 | ||

| 0, n (%) | 219 (79.6) | 86 (89.6) | – |

| 1, n (%) | 45 (16.4) | 8 (8.3) | – |

| 2, n (%) | 9 (3.3) | 1 (1.0) | – |

| 3+, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | – |

| Position, n (%)* | – | ||

| Lineman | 98 (35.6) | – | – |

| Hybrid | 73 (26.5) | – | – |

| Skill | 93 (33.8) | – | – |

| Race, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| White | 229 (83.3) | 85 (88.5) | – |

| Black/African American | 24 (8.7) | 1 (1.0) | – |

| Asian | 4 (1.5) | 5 (5.2) | – |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | – |

| Multiracial | 15 (5.4) | 4 (4.2) | – |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.61 | ||

| Not Latino/Hispanic | 261 (94.9) | 93 (96.9) | – |

| Latino/Hispanic | 14 (5.1) | 3 (3.1) | – |

| Mental Health Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.56 | ||

| Yes | 43 (15.6) | 12 (12.5) | – |

| No | 232 (84.4) | 84 (87.5) | – |

| Head Impact Frequency | |||

| Year 1, mean (SD) | 92.8 (110.8) | – | – |

| Year 2, mean (SD) | 97.2 (148.4) | – | – |

| Year 3, mean (SD) | 57.2 (77.0) | – | – |

| Year 4, mean (SD) | 110.9 (154.6) | – | – |

Group demographics at time of initial enrollment.

*Not equal to 100 due to missing positions. SD, standard deviation. y; year.

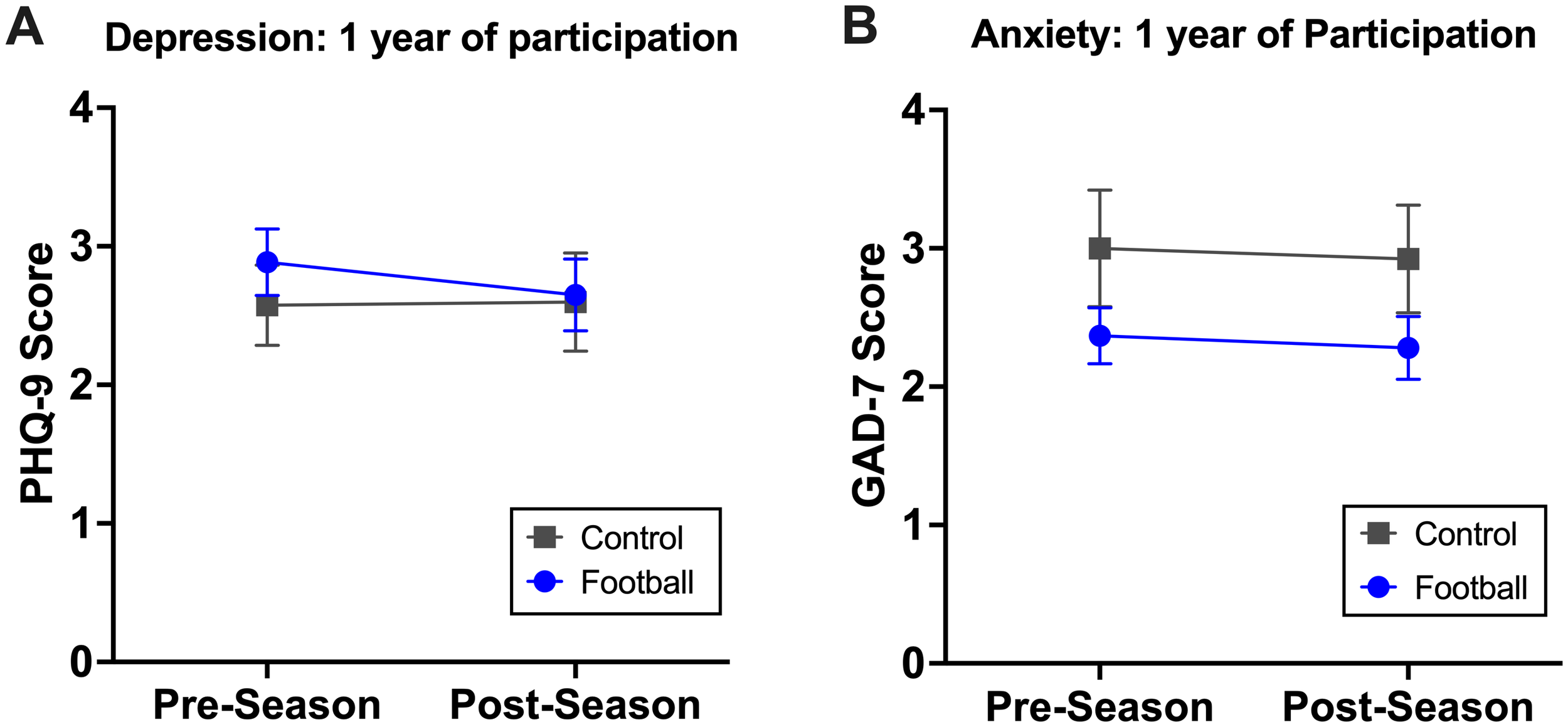

Impact of 1 football season participation on mental health outcomes

There were no significant differences in depression and anxiety scores across one season (preseason vs. postseason) or between groups, as illustrated by no significant group-by-time interaction [PHQ-9, b=-0.10, 95%CI(-0.98, 0.76), p=0.814; GAD-7, b=0.09, 95%CI(-0.62, 0.79), p=0.806; Figure 2]. More specifically, football players exhibited 2.89±3.90 in PHQ-9 score (depression) and 2.37±3.22 in GAD-7 score (anxiety) at preseason, which were comparable to their postseason (depression 2.65±4.05; anxiety 2.28±3.49), as well as those of control athletes (preseason: depression 2.57±2.81, anxiety 3.00±4.09; postseason: depression 2.60±3.39, anxiety 2.92±3.74; Supplementary Table 1). Of note, a history of mental health diagnosis was significantly associated with elevated depression and anxiety scores regardless of groups or timepoints. Conversely, there was no association between mental health outcomes and cumulative head impacts during a season [PHQ-9: b=-0.003, 95%CI(-0.008, 0.002), p= 0.201; GAD-7: b=-0.002, 95%CI(-0.006, 0.002), p=0.332].

Figure 2

A single football season effects on depression and anxiety. Among 275 football players and 96 control athletes, there were no significant changes in depression (A) or anxiety (B) across one season.

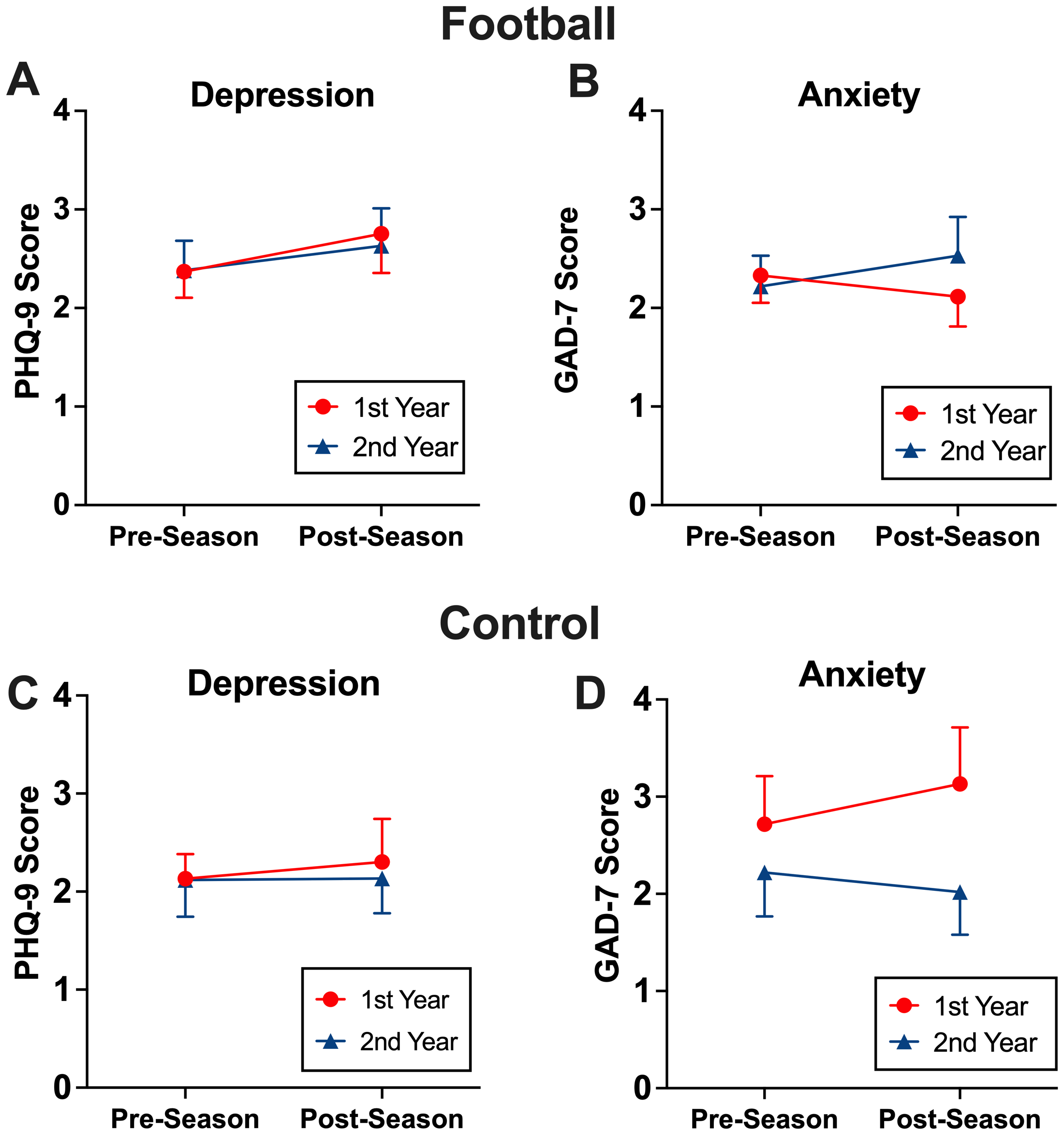

Multi-season effects on mental health outcomes

Mixed-effects regression models were used to examine associations between multiple seasons of football participation and alterations in mental health status. First, among football players participating in 2 consecutive seasons, there were no statistically significant differences in the pattern of mental health changes across 2 seasons, as evidenced by no significant season (pre vs. post) by year (1st vs. 2nd year participation) interaction [PHQ-9 b=0.01, 95%CI (-0.96, 0.98), p=0.980; GAD-7 b=0.42, 95%CI(-0.43, 1.27), p=0.33; Figure 3]. This was consistent in the control group (Figure 3). There was no association between mental health outcomes and cumulative head impacts.

Figure 3

The effects of two consecutive season on mental health. Among those who participated two consecutive seasons, football players and control athletes maintained depression (A, C) and anxiety (B, D) symptoms after the 2nd season similar to their 1st season.

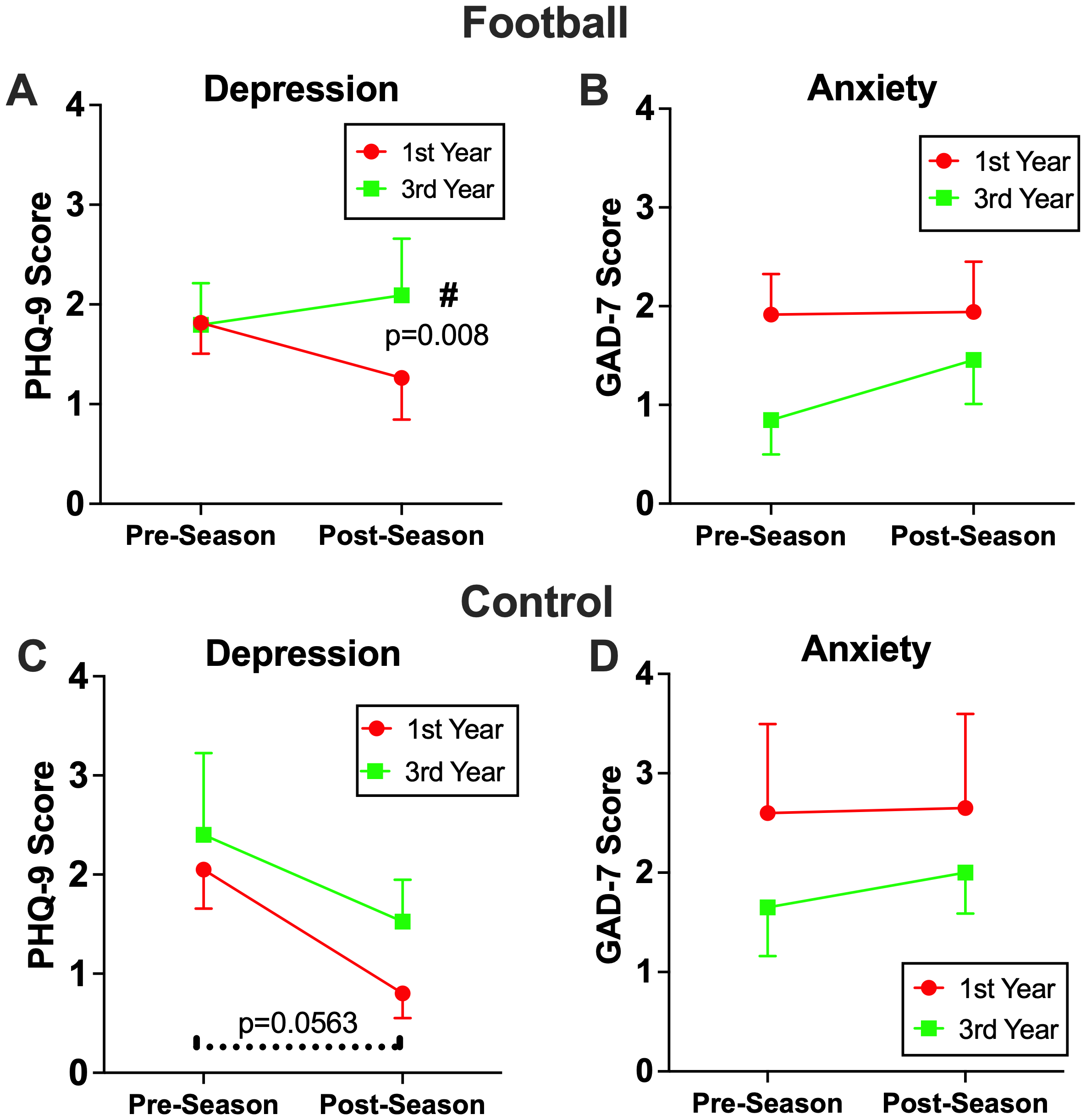

Conversely, among football players who participated in three consecutive seasons, PHQ-9 scores showed a modest but statistically significant season (pre vs. post) by year (1st vs. 3rd) interaction [PHQ-9: b=1.50, 95%CI (0.32, 2.66), p=0.015], reflecting higher postseason depressive symptom scores in the 3rd year compared with the 1st year. Post-hoc analysis also revealed that PHQ-9 scores at 3rd year postseason were significantly greater than those of the 1st year postseason [b=2.511, 95%CI (0.55, 4.47), p=0.008; Figure 4]. While control athletes did result in a significant decline in PHQ-9 scores from preseason to postseason after their first year of participation [b=-1.25, 95% CI (-2.53, 0.03), p=0.0563], score trends remained consistent across 1st and 3rd year of participation (Figure 4). Unlike PHQ-9, there were no significant multi-year effects in GAD-7 scores across seasons or between groups. There was no association between mental health outcomes and cumulative head impacts.

Figure 4

The effects of three consecutive season on mental health. Among football players who participated three consecutive seasons, significantly higher levels of depression symptoms (A), but not anxiety (B), were observed after their 3rd season compared to their 1st season (p=0.0148), which resulted in a significant group by time interaction (p=0.033). The control group exhibited decrease in depression symptoms in both their 1st and 3rd season (C), while anxiety symptoms remained consistent across both seasons remained consistent across both seasons (D).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this multisite, longitudinal study is the first to examine the relationship between RHI exposure during a high school football career and changes in mental health outcomes. The key findings were twofold: (1) consistent with our hypothesis and previous pilot study (18), a single season of football did not significantly influence depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to non-contact controls, even among players with frequent exposure to RHI; and (2) this stability in mental health persisted after two seasons in both the football and control groups; however, depressive symptoms after the third consecutive football season were significantly worse than postseason scores of their first season. This trend was absent in the control group. In line with our hypotheses, these findings suggest short-term football participation may not harm mental health, regardless of impact frequency, but prolonged exposure across seasons may contribute to cumulative psychological burden in adolescent players.

The novelty of the study findings is the emergence of depressive symptoms among adolescent football players after three consecutive seasons of participation, aligning with the notion that the effects of RHI may accumulate slowly and contribute to the progressive disturbances in mental health. For example, Guskiewicz et al. (26) conducted a cross-sectional survey study of 2, 552 retired professional football players (mean, 53.8 years) and identified elevated risks of depression diagnosis, which was modulated by lifetime concussion history, with 1 to 2 and 3 or more concussions increased likelihood of depression diagnosis by 1.5 and 3 folds, respectively. These findings were corroborated in former elite and amateur rugby players (27), former college (28), former professional (29), and active professional football players (30). In more acute settings, concussions can heighten depressive and anxiety symptoms, often manifested in a form of persistent post-concussive symptoms (PPCS) (31, 32). Upwards of 50% of adolescents experience PPCS even after 4 weeks post-concussion (31, 33), whereas 10-20% of college-aged adults and 15-30% of children have been shown to develop PPCS (34). Specifically, preteen athletes (8–12 yo) returned to sports faster (11.6 vs. 25.1 days) than teenage athletes (13–18 yo) (35), with teenagers facing 3 times higher risk of developing PPCS than preteens (36). Furthermore, teenagers who sustain concussive injuries have a 3-fold increase in the risk of developing depression and attention disorder within 5 years of injury (13). These data support that adolescence is a critical developmental window with heightened vulnerability to brain trauma. It is important to note that only a small fraction of football or control athletes (<7%) exceeded clinical thresholds (score >10) from preseason to postseason for all 3 years, suggesting that while statistically significant, most symptom fluctuations were not clinically significant.

In addition to concussive blows, researchers have begun warning the effects of subconcussive RHI in mental health. Montenigro et al. (15) proposed a threshold for lifetime RHI that can trigger mental and cognitive declines, with surpassing 1, 800 cumulative RHI being associated with a linear increase in depression risks. In seminal 2023 paper, McKee et al. (11), for the first time, illustrated that athletes exposed to RHI can develop CTE even below the age of 30. Based on informants’ data, most individuals diagnosed with CTE post-mortem exhibit increased depressive symptoms, impulsivity, and aggression before their passing (10, 11), emphasizing the importance of identifying progressive clinical symptoms early antemortem. Yet, opposing lines of research pose that the interaction between RHI and declines in mental health requires years of exposure beyond high school sports career. For example, both Iverson et al. (37) and Bohr et al. (38) found no association between contact sport participation up to high school and an increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression, suicide attempts, or cognitive decline. However, critical limitations prevail in both viewpoints surrounding contact sports participation and mental health wellbeing, where most data derived from online survey or informants’ reports in a cross-sectional design. Our data derived from one of the largest longitudinal studies in adolescent football players amalgamate previous perspectives and suggesting that high school football in short-term does not negatively impact mental health status (18), yet they may experience compounding effects over multiple seasons. While depressive symptoms appeared to increase after three consecutive football seasons, this association should be interpreted with caution. Given the observational nature of the study, causal inference cannot be established. Multiple contextual and developmental factors may also contribute to the observed pattern, including academic stress, social pressures, coaching or team changes, non-concussive injuries, and sleep disruption during adolescence. Therefore, these mental health declines in football players may have implications in their social and academic domains considering the complexity of brain development and societal demands during adolescence. Since adolescence is characterized by developmental increases in stress sensitivity and emotional fluctuation, and given evidence of generational rises in adolescent depressive and anxiety symptoms even among youth without head impact exposure (39), the control group in our study provides an essential benchmark for interpreting mental health trajectories independent of head impact exposure. Furthermore, a longitudinal survey study indicates no negative mental health implications of playing football during adolescence. However, high school football players exhibiting mental health issues were associated with an increased risk for depression diagnosis and suicidal ideation more than 20 years after their high school football career (17).

Contrary to depression, the lack of significant multi-year effects on anxiety symptoms is noteworthy. Factors such as a structured team environment, including social support from teammates and coaches, may mitigate feelings of being anxious (40). The prevalence of anxiety in adolescent athletic cohorts may be less prominent compared to depression. For example, among 471 adolescent soccer players, while mild to moderate depression were identified in 33 players (7.6%), the GAD-7 score indicated an anxiety disorder in 6 (1.4%) players. Compared to the general population, the prevalence of anxiety disorders was significantly lower in soccer players (41). Further research is warranted to clarify the differential impact of sports-related RHI on various aspects of mental health.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the cohort consisted exclusively of male athletes, which limits the generalizability to female athletes, whose responses may be moderated by anatomical, hormonal, and biomechanical differences. Second, although the sample size was robust, most participants were White and Non-Hispanic/Latino. Broader inclusion of racially and ethnically diverse individuals would enhance the generalizability of the findings. Third, concussion history, prior mental health diagnoses, and survey responses (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) were self-reported, which may introduce bias. However, the significant association between previous diagnoses and elevated scores supports the validity of the survey instruments. Fourth, the subgroup of athletes who completed three consecutive seasons was relatively small (39 football players and 20 controls), which limits statistical power to detect small changes in PHQ-9 scores and results in wide confidence intervals around our estimates. Thus, the observed increase in depressive symptoms after three seasons should be considered hypothesis-generating and preliminary. In addition, we conducted multiple mixed effects models across two correlated outcomes (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) and several time frames, which increases the risk of Type-I error. We therefore suggest appropriate caution when interpreting the three-season PHQ-9 findings, which requires replication in future studies. Lastly, a group of non-athlete controls may help untangled the potential mental health benefits of physical activity.

Conclusions

Our data support that the participation in a single football season was not associated with changes in depressive or anxiety symptoms. However, among athletes with three consecutive seasons of participation, depression symptoms were heightened after their 3rd season, compared to their 1st or 2nd season, suggesting a cumulative effect of RHI over time. The absence of similar changes in the control group reinforces the specificity of these effects to football-related participation. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring mental health across multiple seasons, as short-term assessments may not capture the gradual neuropsychological toll of continued exposure to subconcussive impacts.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Indiana University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

CB: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. GR: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. SS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. JS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Resources, Conceptualization, Investigation. GE: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. TZ: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. KK: Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. JB: Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SN: Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KK: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. All aspects of this study were supported by National Institutes of Health -National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (to K Kawata: R01NS113950). Sponsors had no role in the design or execution of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

JB reports the interest with Abbott Diagnostics research support, speaker fees and BioMerieux advisory panel, research support.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1723687/full#supplementary-material.

References

1

Crisco JJ Fiore R Beckwith JG Chu JJ Brolinson PG Duma S et al . Frequency and location of head impact exposures in individual collegiate football players. J Athl Train. (2010) 45:549–59. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.6.549

2

Broglio SP Eckner JT Kutcher JS . Field-based measures of head impacts in high school football athletes. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2012) 24:702–8. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283595616

3

Zuidema TR Bazarian JJ Kercher KA Mannix R Kraft RK Newman SD et al . Longitudinal associations of clinical and biochemical head injury biomarkers with head impact exposure in adolescent football players. JAMA Network Open. (2023) 6:e2316601. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.16601

4

Joseph JR Swallow JS Willsey K Lapointe AP Khalatbari S Korley FK et al . Elevated markers of brain injury as a result of clinically asymptomatic high-acceleration head impacts in high-school football athletes. J Neurosurg. (2018) 130:1642–48.

5

Oliver JM Anzalone AJ Stone JD Turner SM Blueitt D Garrison JC et al . Fluctuations in blood biomarkers of head trauma in NCAA football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurosurg. (2019) 130:1655–62. doi: 10.3171/2017.12.JNS172035

6

Black SE Follmer B Mezzarane RA Pearcey GEP Sun Y Zehr EP . Exposure to impacts across a competitive rugby season impairs balance and neuromuscular function in female rugby athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. (2020) 6:e000740. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000740

7

Bazarian JJ Zhu T Zhong J Janigro D Rozen E Roberts A et al . Persistent, long-term cerebral white matter changes after sports-related repetitive head impacts. PloS One. (2014) 9:e94734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094734

8

Bazarian JJ Abar B Merchant-Borna K Pham DL Rozen E Mannix R et al . A pilot study investigating the use of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein to monitor changes in brain white matter integrity after repetitive head hits during a single collegiate football game. J neurotrauma. (2024) 41:1597–608. doi: 10.1089/neu.2023.0307

9

McKee AC Stein TD Huber BR Crary JF Bieniek K Dickson D et al . Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): criteria for neuropathological diagnosis and relationship to repetitive head impacts. Acta Neuropathol. (2023) 145:371–94. doi: 10.1007/s00401-023-02540-w

10

Mez J Daneshvar DH Kiernan PT Abdolmohammadi B Alvarez VE Huber BR et al . Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of american football. Jama. (2017) 318:360–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8334

11

McKee AC Mez J Abdolmohammadi B Butler M Huber BR Uretsky M et al . Neuropathologic and clinical findings in young contact sport athletes exposed to repetitive head impacts. JAMA Neurol. (2023) 80:1037–1050. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907

12

Ledoux AA Webster RJ Clarke AE Fell DB Knight BD Gardner W et al . Risk of mental health problems in children and youths following concussion. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e221235. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1235

13

Chrisman SP Richardson LP . Prevalence of diagnosed depression in adolescents with history of concussion. J Adolesc Health. (2014) 54:582–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.006

14

Kay JJM Coffman CA Harrison A Tavakoli AS Torres-McGehee TM Broglio SP et al . Concussion exposure and suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts among US high school students. J Athl Train. (2023) 58:751–8. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0117.22

15

Montenigro PH Alosco ML Martin BM Daneshvar DH Mez J Chaisson CE et al . Cumulative head impact exposure predicts later-life depression, apathy, executive dysfunction, and cognitive impairment in former high school and college football players. J Neurotrauma. (2017) 34:328–40. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4413

16

Buddenbaum CV Recht GO Rodriguez AK Newman SD Kawata K . Associations between repetitive head impact exposure and midlife mental health wellbeing in former amateur athletes. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1383614. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1383614

17

Iverson GL Terry DP . High school football and risk for depression and suicidality in adulthood: findings from a national longitudinal study. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:812604. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.812604

18

Kercher KA Steinfeldt JA Rettke DJ Zuidema TR Walker MJ Martinez Kercher VM et al . Association between head impact exposure,Psychological needs, and indicators of mental health among U.S. High school tackle football players. J Adolesc Health. (2023) 72:502–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.11.247

19

Kroenke K Spitzer RL Williams JBW . The PHQ-9. J Gen Internal Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

20

Richardson LP McCauley E Grossman DC McCarty CA Richards J Russo JE et al . Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. (2010) 126:1117–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852

21

Spitzer RL Kroenke K Williams JB Lowe B . A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

22

Tiirikainen K Haravuori H Ranta K Kaltiala-Heino R Marttunen M . Psychometric properties of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 272:30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.004

23

Bartsch AJ McCrea MM Hedin DS Gibson PL Miele VJ Benzel EC et al . Laboratory and on-field data collected by a head impact monitoring mouthguard. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. (2019) 2019:2068–72. doi: 10.1109/EMBC43219.2019

24

Bartsch AJ Hedin D Alberts J Benzel EC Cruickshank J Gray RS et al . High energy side and rear american football head impacts cause obvious performance decrement on video. Ann BioMed Eng. (2020) 48:2667–77. doi: 10.1007/s10439-020-02640-8

25

Kercher KA Steinfeldt JA Macy JT Seo DC Kawata K . Drill intensity and head impact exposure in adolescent football. Pediatrics. (2022) 150. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057725

26

Guskiewicz KM Marshall SW Bailes J McCrea M Harding HP Jr. Matthews A et al . Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2007) 39:903–9. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180383da5

27

Hind K Konerth N Entwistle I Hume P Theadom A Lewis G et al . Mental health and wellbeing of retired elite and amateur rugby players and non-contact athletes and associations with sports-related concussion: the UK rugby health project. Sports Med. (2022) 52:1419–31. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01594-8

28

Kerr ZY Thomas LC Simon JE McCrea M Guskiewicz KM . Association between history of multiple concussions and health outcomes among former college football players: 15-year follow-up from the NCAA concussion study (1999-2001). Am J sports Med. (2018) 46:1733–41. doi: 10.1177/0363546518765121

29

Kerr ZY Marshall SW Harding HP Jr. Guskiewicz KM . Nine-year risk of depression diagnosis increases with increasing self-reported concussions in retired professional football players. Am J sports Med. (2012) 40:2206–12. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456193

30

Pryor J Larson A DeBeliso M . The prevalence of depression and concussions in a sample of active north american semi-professional and professional football players. J Lifestyle Med. (2016) 6:7–15. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2016.6.1.7

31

Ledoux AA Tang K Yeates KO Pusic MV Boutis K Craig WR et al . Natural progression of symptom change and recovery from concussion in a pediatric population. JAMA Pediatr. (2019) 173:e183820. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3820

32

Novak Z Aglipay M Barrowman N Yeates KO Beauchamp MH Gravel J et al . Pediatric emergency research Canada predicting persistent postconcussive problems in pediatrics concussion, association of persistent postconcussion symptoms with pediatric quality of life. . JAMA Pediatr. (2016) 170:e162900. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2900

33

Corwin DJ Zonfrillo MR Master CL Arbogast KB Grady MF Robinson RL et al . Characteristics of prolonged concussion recovery in a pediatric subspecialty referral population. J Pediatr. (2014) 165:1207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.08.034

34

Fried E Balla U Catalogna M Kozer E Oren-Amit A Hadanny A et al . Persistent post-concussive syndrome in children after mild traumatic brain injury is prevalent and vastly underdiagnosed. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:4364. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08302-0

35

Carson JD Lawrence DW Kraft SA Garel A Snow CL Chatterjee A et al . Premature return to play and return to learn after a sport-related concussion: physician’s chart review. Can Fam Physician. (2014) 60:e310, e312–5.

36

Purcell L Harvey J Seabrook JA . Patterns of recovery following sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila). (2016) 55:452–8. doi: 10.1177/0009922815589915

37

Iverson GL Merz ZC Terry DP . Playing high school football is not associated with an increased risk for suicidality in early adulthood. Clin J Sport Med. (2021) 31:469–74. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000890

38

Bohr AD Boardman JD McQueen MB . Association of adolescent sport participation with cognition and depressive symptoms in early adulthood. Orthop J Sports Med. (2019) 7:2325967119868658. doi: 10.1177/2325967119868658

39

Borg ME Heffer T Willoughby T . Generational shifts in adolescent mental health: A longitudinal time-lag study. J Youth Adolesc. (2025) 54:837–48. doi: 10.1007/s10964-024-02095-3

40

Reardon CL Hainline B Aron CM Baron D Baum AL Bindra A et al . Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). Br J Sports Med. (2019) 53:667–99. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715

41

Junge A Feddermann-Demont N . Prevalence of depression and anxiety in top-level male and female football players. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. (2016) 2:e000087. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000087

Summary

Keywords

brain injury, concussion, subconcussive head impacts, depression, anxiety, football

Citation

Buddenbaum CV, Recht GO, Sweeney SH, Steinfeldt JA, Ellis G, Zuidema TR, Kercher KA, Bazarian JJ, Newman SD and Kawata K (2025) Mental health trajectory throughout high school football career: a four-year prospective cohort study. Front. Psychiatry 16:1723687. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1723687

Received

12 October 2025

Revised

07 November 2025

Accepted

12 November 2025

Published

03 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Seetharaman Hariharan, The University of the West Indies St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

Reviewed by

Sharon Barak, Ariel University, Israel

Laura Gil Caselles, University of Murcia, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Buddenbaum, Recht, Sweeney, Steinfeldt, Ellis, Zuidema, Kercher, Bazarian, Newman and Kawata.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keisuke Kawata, kkawata@iu.edu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.