- 1University of Kentucky, Substance Use Priority Research Area, Lexington, KY, United States

- 2College of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

- 3Voices of Hope, Lexington, KY, United States

- 4College of Medicine, Center on Drug and Alcohol Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

- 5Department of Behavioral Science, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

- 6College of Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

- 7Arthur Street Hotel, Louisville, KY, United States

Introduction: Medication treatment for opioid use disorder (MOUD) decreases opioid overdose risk and is the standard of care for persons with opioid use disorder (OUD). Recovery coach (RC)-led programs and associated training curriculums to improve outcomes around MOUD are limited. We describe our comprehensive training curriculum including instruction and pedagogy for novel RC-led MOUD linkage and retention programs and report on its feasibility.

Methods–pedagogy and training development: The Kentucky HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Communities Study (HCS) created the Linkage and Retention RC Programs with a local recovery community organization, Voices of Hope-Lexington. RCs worked to reduce participant barriers to entering or continuing MOUD, destigmatize and educate on MOUD and harm reduction (e.g., safe injection practices), increase recovery capital, and provide opioid overdose education with naloxone distribution (OEND). An extensive hybrid (in-person and online, both synchronous and asynchronous), inclusive learning-focused curriculum to support the programs (e.g., motivational interviewing sessions, role plays, MOUD competency assessment, etc.,) was created to ensure RCs developed the necessary skills and could demonstrate competency before deployment in the field. The curriculum, pedagogy, learning environment, and numbers of RCs trained and community venues receiving a trained RC are reported, along with interviews from three RCs about the training program experience.

Results: The curriculum provides approximately 150 h of training to RCs. From December 2020 to February 2023, 93 RCs and 16 supervisors completed the training program; two were unable to pass a final competency check. RCs were deployed at 45 agencies in eight Kentucky HCS counties. Most agencies (72%) sustained RC services after the study period ended through other funding sources. RCs interviewed reported that the training helped them better explain and dispel myths around MOUD.

Conclusion: Our novel training and MOUD programs met a current unmet need for the RC workforce and for community agencies. We were able to train and deploy RCs successfully in these new programs aimed at saving lives through improving MOUD linkage and retention. This paper addresses a need to enhance the training requirements around MOUD for peer support specialists.

1 Introduction

1.1 Opioid use disorder and medication for opioid use disorder

The opioid epidemic is a public health crisis with over 100,000 opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States in 2021, representing a 59% increase from 2019 (1). Kentucky had the fourth-highest state overdose death rate in 2021 (55.6 deaths per 100,000) (2). Improving access to and retention on Food and Drug Administration-approved medication treatments for opioid use disorder (MOUD), specifically methadone and buprenorphine, is critical because they decrease the risk of overdose and all-cause mortality (3). Further, treatment retention is critical because opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic relapsing disorder.

Despite the effectiveness of MOUD, they remain underutilized (4) often due to lack of access, misinformation, and stigma. Transportation is also a major barrier, particularly for methadone among individuals living in rural and small urban communities where there are fewer programs and longer drive times (5). Further, systemic barriers to MOUD remain pervasive in many areas of health care and the criminal legal system (6). For example, the criminal legal system has not routinely allowed persons with OUD to continue MOUD upon incarceration, a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (7).

1.2 Recovery coaching and OUD

Interventions are needed to reduce barriers to MOUD, including improving community health literacy and addressing misinformation and stigmatizing beliefs about MOUD. People who use drugs may prefer to work with peer workers (i.e., people with lived experience) versus non-peer workers (8). Individuals who choose to initiate methadone or buprenorphine often learn about them from others with OUD and report becoming interested due to their success (9). The association between shared positive lived experience on MOUD and treatment uptake, as well as frequent need for assistance navigating structural barriers to MOUD, highlight the need for a formalized recovery coach workforce with training programs emphasizing linking to MOUD and facilitating retention.

Recovery Coaches (RC; a type of peer worker) are individuals with lived experience with substance use disorder who are in remission and recovery and whose job entails performing non-clinical recovery support services, such as facilitating goal setting with participants, making resource referrals, and inspiring hope that remission and recovery are possible (10). Evidence suggests (11) RC programs can improve outcomes such as decreasing substance use (12) and increasing employment (13).

The evidence for RC-led interventions tailored to individuals with OUD, however, is limited. A randomized controlled trial of individuals (n = 80) treated for opioid overdose found that participants receiving RC phone support were significantly less likely to report another opioid overdose compared to participants receiving usual care (i.e., overdose education and naloxone distribution; OEND) (14). RCs also show promise in facilitating screening for illicit opioid use and interest in linkage to buprenorphine within the emergency department (15). A recent review of peer-led services for individuals with OUD identified 12 interventions, with nearly all focused on linkage to treatment (16). No studies focused on MOUD retention or RC training programs for peers working specifically with persons with OUD (16), though recent focus groups with opioid treatment program patients and staff, including RCs, demonstrated acceptability of using RCs to improve methadone retention (17). Current RC training is often limited to participation in statewide peer support certification programs and broadly described “periodic trainings” on topics like motivational interviewing (MI) and boundaries (18)–with largely absent descriptions of curriculum, instruction, and pedagogy.

1.3 Study overview and recovery community organizations

The HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Communities Study (HCS) is a four-state (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio) parallel group cluster randomized controlled trial aiming to reduce opioid overdose deaths by 40% (19). The HCS intervention, Communities that Heal (CTH), seeks to implement evidence-based practices (EBPs) to reduce opioid overdose through community engaged, coalition-led efforts in each study community. EBPs focus on OEND, effective delivery of MOUD (with emphasis on linkage to and retention on buprenorphine and methadone), and safer opioid prescribing and dispensing (20). Eight Kentucky counties were randomized to receive the CTH intervention (January 2020 to June 2022) and eight counties were randomized to a waitlist control period, and later received the CTH intervention (July 2022 to December 2023) (19).

The HCS-Kentucky (HCS-KY) research team, recognizing the growing evidence around peer support to engage persons in treatment to promote remission and recovery, along with community interest in peer services, searched for existing training relevant to MOUD linkage and retention. After an extensive literature review and contacting national and state stakeholder groups, it was determined there was a dearth of training curriculums and resources tailored specifically to RCs around MOUD. Additionally, as only a small minority of individuals with OUD ever receive MOUD (3), many individuals entering the peer workforce do not have personal experience with or education on MOUD. To address these gaps, the KY team created two novel peer-led programs, one for linkage and one for retention, with associated comprehensive training curriculum and instruction.

The programs’ workforce was built utilizing current Kentucky state-certified Peer Support Specialists (PSSs) hired by a local recovery community organization, Voices of Hope-Lexington (VOH). Recovery community organizations are non-profit organizations that provide a breadth of recovery services, such as peer recovery support, harm reduction education, and mutual aid meetings (21). Recovery community organizations are typically independent agencies with common core values including valuing all pathways of recovery (22), allowing recovery community organizations to engage individuals in active use and across all stages of treatment readiness, remission, and recovery (23). For RC positions, VOH hired individuals who were eligible to complete the Kentucky Adult Peer Support Specialist certification (i.e., self-report being in recovery from a substance use disorder and having a GED or higher level of education). After completing the training program described below, RCs were deployed in the field as linkage and/or retention RCs as part of the EBPs chosen by the HCS-KY coalitions (24).

The purpose of this paper is to describe: (1) the development of a training curriculum for the HCS/Voices of Hope (HCS-VOH) Linkage and Retention RC Programs; (2) the HCS-VOH training curriculum contents and structure including pedagogical framework, core competencies, and learning environment; and (3) three RC case studies reporting about their training experiences along with the number of RCs trained and deployed.

2 Methods–program overview, pedagogical framework and principles, underlying competencies, and trainee experience collection

2.1 Overview of HCS-VOH linkage and retention RC programs

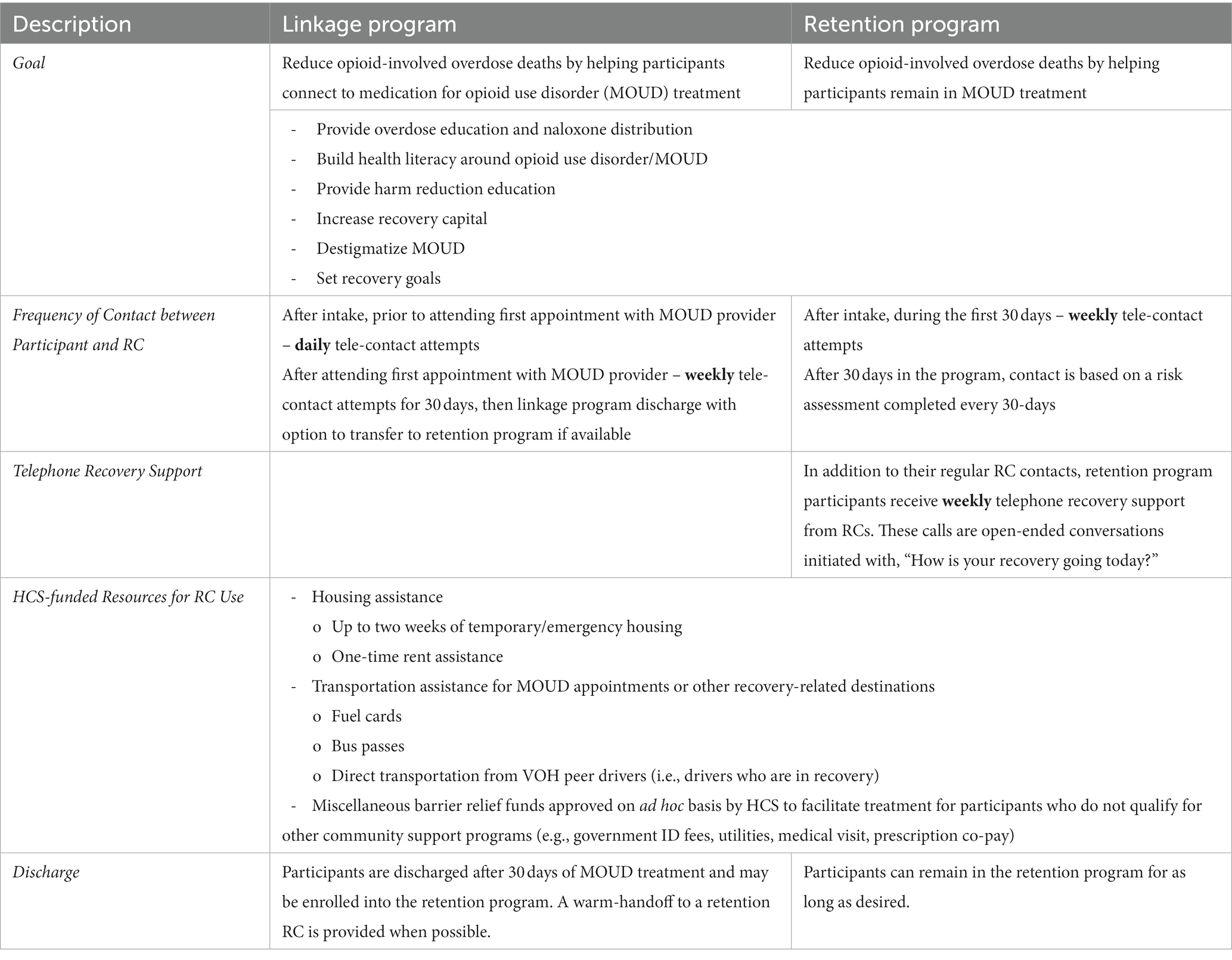

The overarching goals of the HCS-VOH Linkage and Retention RC Programs (see Table 1) are to reduce opioid-involved overdose deaths by helping participants enter and remain in MOUD treatment, respectively, with active assistance in addressing barriers to these goals. In both programs, RCs aim to build health literacy around OUD and MOUD, destigmatize MOUD, increase recovery capital, and set recovery goals alongside providing OEND and harm reduction education. Linkage RCs are deployed in community settings to enroll individuals at high risk for opioid overdose (e.g., syringe service programs, criminal legal system venues such as detention centers, etc.). During initial visits, RCs educate participants about Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for OUD and address common misconceptions about being on MOUD. RCs attempt ongoing daily contact with participants until they successfully attend a first appointment with a MOUD provider, after which point the RC attempts weekly contact.

Table 1. Description of HEALing Communities Study (HCS)–Voices of Hope (VOH) linkage and retention recovery coaching (RC) program.

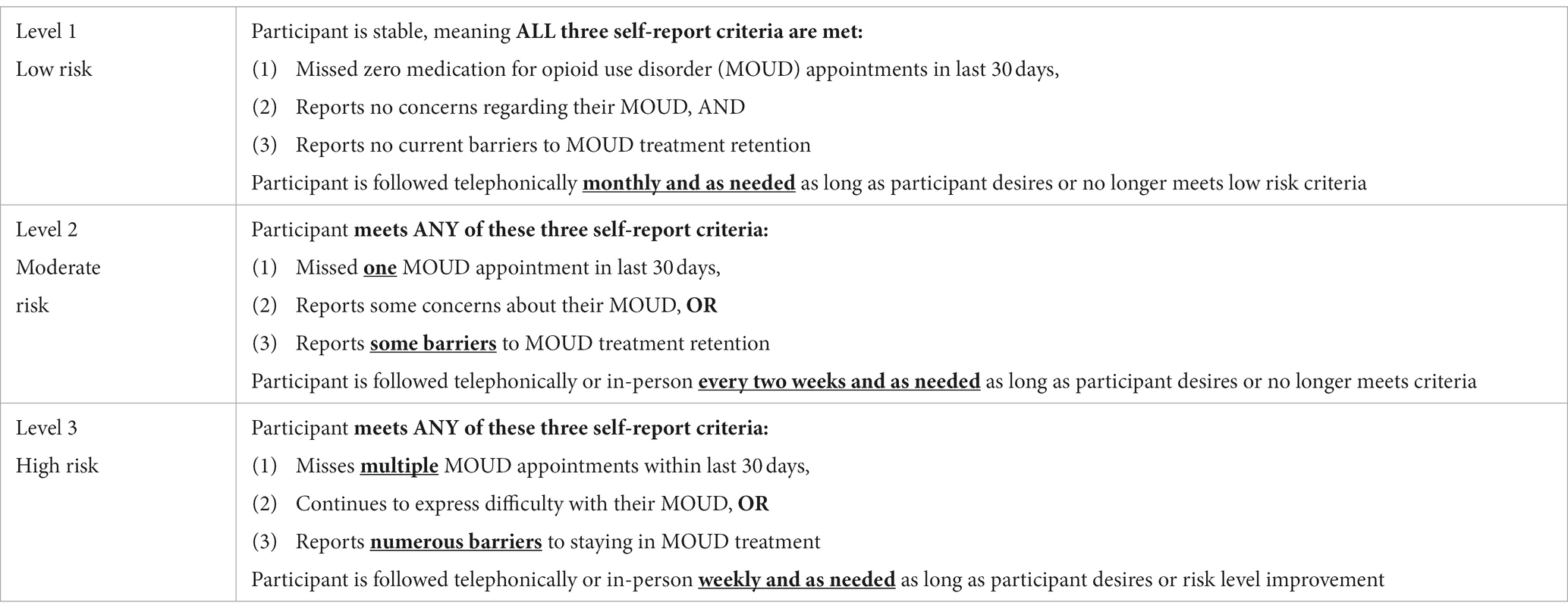

Retention program RCs focus on increasing recovery capital and addressing barriers and concerns that may adversely affect participants’ retention in MOUD treatment and are predominantly embedded in community MOUD provider agencies, though some are also deployed in probation and parole programs to help retain those who are already on MOUD. During the initial intake, RCs focus on understanding participant concerns and barriers to staying in MOUD treatment and complete a recovery capital assessment to learn about participants’ potential supports and recovery goals. RCs contact participants at least weekly during the first 30 days to address retention barriers such as transportation, housing, employment, insurance, obtaining government identification, etc. Subsequently, RCs complete a risk assessment every 30 days to inform the recommended frequency of RC-participant contact based upon potential risk for treatment discontinuation (Table 2). Regardless of risk level, participants receive weekly RC telephone recovery support calls designed to provide connection to resources, non-judgmental social support, and growth of the recovery support network (25). RCs rotate making telephone recovery support calls and contact all enrolled participants. RCs in both the Linkage and Retention programs can also access the study’s barrier relief fund to assist with participants’ barriers to starting or continuing MOUD. These miscellaneous requests are approved by HCS on an ad hoc basis to facilitate treatment, such as providing a phone or paying for a government ID, utilities, medical visit, or prescription co-pays.

The HCS protocol (Pro00038088), which includes the HCS-VOH Linkage and Retention RC Programs, was approved by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study single Institutional Review Board (IRB). Written informed consent for all individuals receiving HCS services, (e.g., linkage and retention program participants) was waived by the IRB.

2.2 Training curriculum development

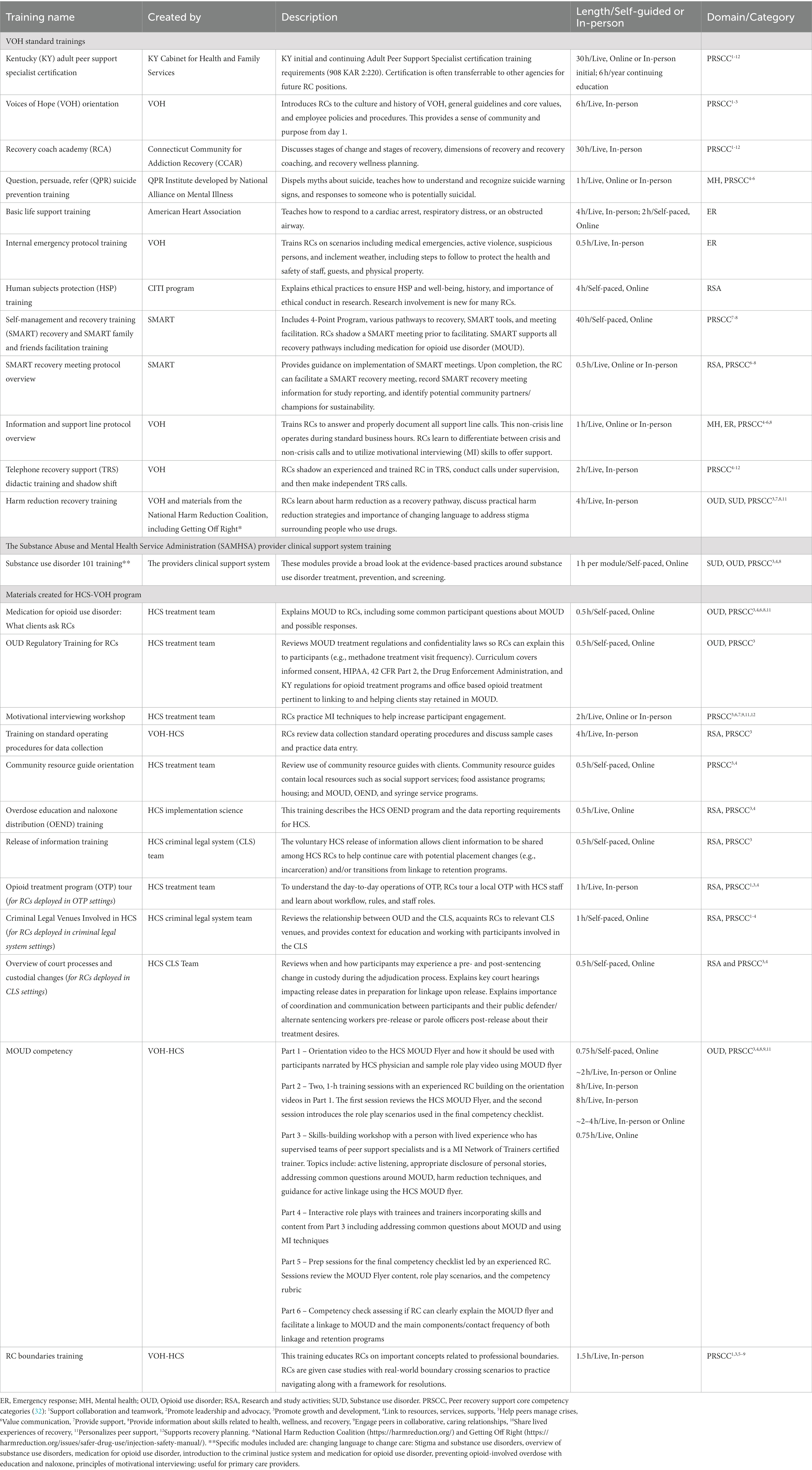

After an extensive literature review and contacting key stakeholder groups including the SAMHSA-funded Providers Clinical Support System (26) and Opioid Response Network, and Kentucky’s Department for Behavioral Health, Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities, it was determined there was a dearth of training resources tailored specifically to RCs around MOUD. As a result, the HCS-KY team, including physicians who are board-certified in addiction medicine, and Voices of Hope iteratively built the training curriculum beginning with an initial version used at the start of the study’s intervention period (January 2021). As the linkage and retention programs grew and more RCs were hired, the group, whose members had expertise in MOUD treatment, recovery support services, implementation science, and the criminal legal system, worked collaboratively to assess the training curriculum’s needs and adjusted accordingly. Weekly meetings were held with HCS and VOH leadership in which cases and/or issues from the field were discussed. Based on these discussions and the training curriculum’s learning objectives, changes and additions were made to the curriculum and the programs’ standard operating procedures. The final version of the training curriculum is ~150 h (Table 3) though some placements require extra training. For instance, RCs deployed to detention centers or specialty courts have additional training specific to these venues. The detailed training manual is provided in the Supplementary Material (Data Sheet 1) and available online.1

RCs begin by completing Kentucky state-certified Adult Peer Support Specialist (PSS) training. Supplementing the Kentucky PSS program was important given its brevity (30 required hours) and the cursory teachings of essential topics such as MOUD, substance use disorder, effective listening skills, and principles of recovery. Next, RCs complete VOH’s harm reduction training and an array of nationally recognized trainings, such as SMART Recovery (27) and several Provider Clinical Support System Substance Use Disorder 101 training modules (26). We also created training on topics such as MI skills, boundaries, and OUD/MOUD because RCs often have limited experience with MOUD and may hold stigmatizing views toward MOUD, and many agencies are not familiar with the RC-role and may ask RCs to perform tasks that are outside their scope of work (i.e., boundary violations). All RCs attend weekly team supervision with their program coordinators, receive additional supervision as needed, and regularly review the programs’ Standard Operating Procedures. RCs are required to participate in weekly sessions of the Kentucky Overdose Prevention Education Network, a series of HCS-created live virtual didactics covering relevant topics such as trauma and suicide prevention.

2.3 Pedagogical framework and principles

To build an RC workforce competent and comfortable discussing MOUD with potential and current participants, our training curriculum employs a variety of pedagogical methods. The breadth of methods provides trainees multiple opportunities to demonstrate their understanding of critical concepts (e.g., MOUD, motivational interviewing) in active learning formats. Because a major focus of the training is supporting all recovery pathways, including MOUD treatment, it was crucial that our pedagogy aligned with an inclusive teaching approach for our training. Inclusive teaching pedagogy recognizes the diverse lived experiences of learners and leans into the many beliefs individuals bring to the learning environment (28). Trainees may bring past experiences of MOUD or hold conscious or unconscious stigmatizing beliefs about MOUD (e.g., “Taking MOUD is trading one drug for another”) as they begin their training. Our inclusive approach recognized these experiences and beliefs and, rather than invalidate their lived experience, invited trainees to build skills and knowledge necessary to support others with different recovery pathways (MOUD, specifically).

The breadth of the training’s inclusive pedagogical methods is most apparent in the summative assessment, the MOUD Competency, a six-part, ~23-h training and evaluation. In Parts 1 and 2, trainees are introduced to and review with an experienced RC the HCS MOUD flyer (Supplementary Image 1), which was created by the 4-state HCS Consortium and covers terminology like remission and recovery, understanding opioids, how each of the three MOUD work, and common questions (e.g., MOUD effects on opioid withdrawal and cravings). In Part 3, trainees are introduced to motivational interviewing (MI) by a nationally certified Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers facilitator. The facilitator collaboratively establishes ground rules with trainees, an important step in creating a positive classroom climate (29), and engages trainees in active learning through discussion and retrieval practice. Formative assessments, those that encourage active participation from trainees (30), are held through informal role plays throughout Parts 2 and 3.

Part 4 of the MOUD Competency focuses on using MI skills with in-depth role plays (~30 min each) of a coach-participant interaction in Linkage and Retention programs. In line with a transparent assignment design (31), trainers share: (1) the purpose of the role plays (i.e., transferability to real-world participant interactions), (2) the description of the role-play activity and what is expected from trainees, and (3) a rubric with criteria by which trainees are graded and required to pass before deployment. The role-play scenarios and rubric mirror the summative assessment, giving trainees a clear understanding of what will be expected. A checklist outlining required competencies (e.g., describe OUD as a chronic illness) is provided for each role play. During role plays, coaches practice MI skills, share their lived experience with discretion to inspire hope, review the MOUD flyer, and answer questions drawing on their knowledge of harm reduction and MOUDs. RCs are taught to use their MI skills to guide how they share their story for the participants’ benefit as well as respond to participant questions and concerns. The same two trainers (AFB, JB) led Parts 4 and 5 throughout the program’s duration. During Part 5, RCs are given additional practice opportunities and time to prepare for the competency check with an experienced RC.

The training’s summative assessment, Part 6, is a ~ 45-min competency check led by a RC supervisor alongside a study physician to support and clarify questions as needed. The RC supervisor asks trainees questions to demonstrate proficiency and comfort in explaining the MOUD flyer and using its information to address frequently asked questions (e.g., “Do I have to go through withdrawal to start MOUD?”). Trainees also role play one of three scenarios answering common participant questions while demonstrating their MI skills and knowledge of linkage and retention programs. The physician and RC supervisor are together responsible for passing or requiring the RC, per the grading rubric (Supplementary Image 2), to have more training before reassessing competency for field deployment. The same study physician (ML) led Part 6 throughout the program’s duration.

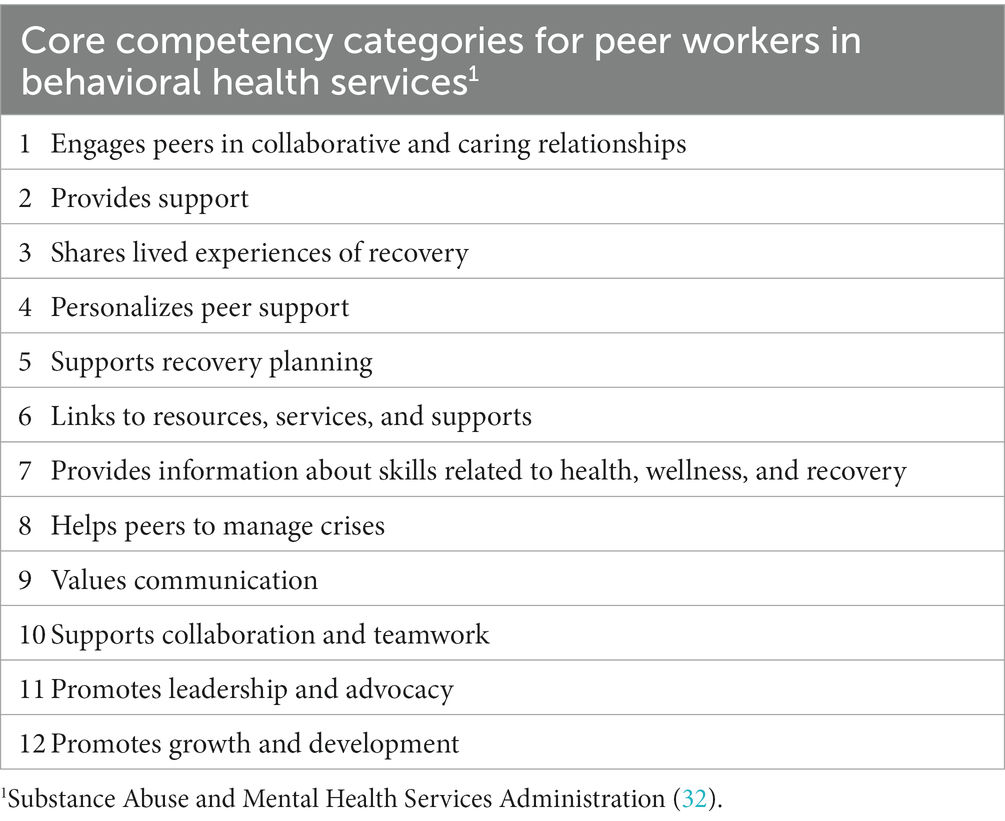

2.4 Underlying competencies

Our training curriculum aligns with the core competency categories for peer workers in behavioral health services established by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (32) (see Table 4). Kentucky’s peer support specialist certification, which all trainees are required to complete, aligns with all 12 core competencies, as does the Recovery Coach Academy developed by the Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery (33). The rest of the trainings meet at least one core competency category or are intended to supplement typical RC training for working on a research study or in the field (e.g., human subjects protection training or basic life support training). Specific core competency categories met by each training are listed in Table 3.

2.5 Collecting trainee experiences

To inform curriculum modification and improvement, we interviewed three RCs referred by RC supervisors who had been placed at their sites for at least 6 months. To maintain confidentiality, one team member (TM) without a RC supervisory role reviewed the referrals, chose three RCs with diverse agency placements, including experience with linkage and retention programs, and conducted the interviews. RCs data were de-identified, summarized, and shared for their review for accuracy prior to team dissemination. Questions included general impressions of the training, how it prepared them (or not), how it changed their views on MOUD (or not), and how the MOUD flyer was used in their work (Supplementary Table 1). IRB approval to collect case studies was received prior to interviewing RCs.

3 Learning environment and learning objectives

3.1 Learning environment

The curriculum is a hybrid design with a blend of in-person, asynchronous online, and synchronous online training. In-person training emphasize active learning through interactive components like the discussion and role plays in the Recovery Coach Academy and MOUD Competency. Using asynchronous online instruction for several introductory trainings helped reduce the burden on training staff and promoted inclusivity for RCs who had different paces of learning. Online training, both asynchronous and synchronous, were also beneficial as trainees were spread across several counties in Kentucky. All trainings were completed during normal work hours (i.e., compensated time) and, for online training, on work-issued computers. Lengthier in-person training (e.g., Recovery Coach Academy and Parts 3 and 4 of the MOUD Competency), were scheduled once per month so that several RCs could attend at once. Larger groups attending these training helped to both reduce trainer burden and encourage active discussions. RC supervisors assisted trainees in scheduling required in-person training offsite (i.e., Kentucky state-certified Adult Peer Support Specialist and Basic Life Support Training).

3.2 Learning objectives

The training program’s learning objectives were defined and outlined for trainees in the MOUD Competency rubric (See Supplementary Image 2). By the end of the training program, trainees should be able to: (1) explain key principles from the HCS MOUD Flyer (e.g., each MOUD mechanism of action, how to access MOUD, effects of each MOUD), (2) successfully demonstrate MI skills by using open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries while discussing MOUD, (3) provide important information on harm reduction and related resources to participants (e.g., overdose education, naloxone access, safe injection, syringe service programs), and (4) explain the linkage and retention programs (e.g., purpose of each program, frequency of contact).

4 Results and coach experiences

4.1 Descriptive quantitative results

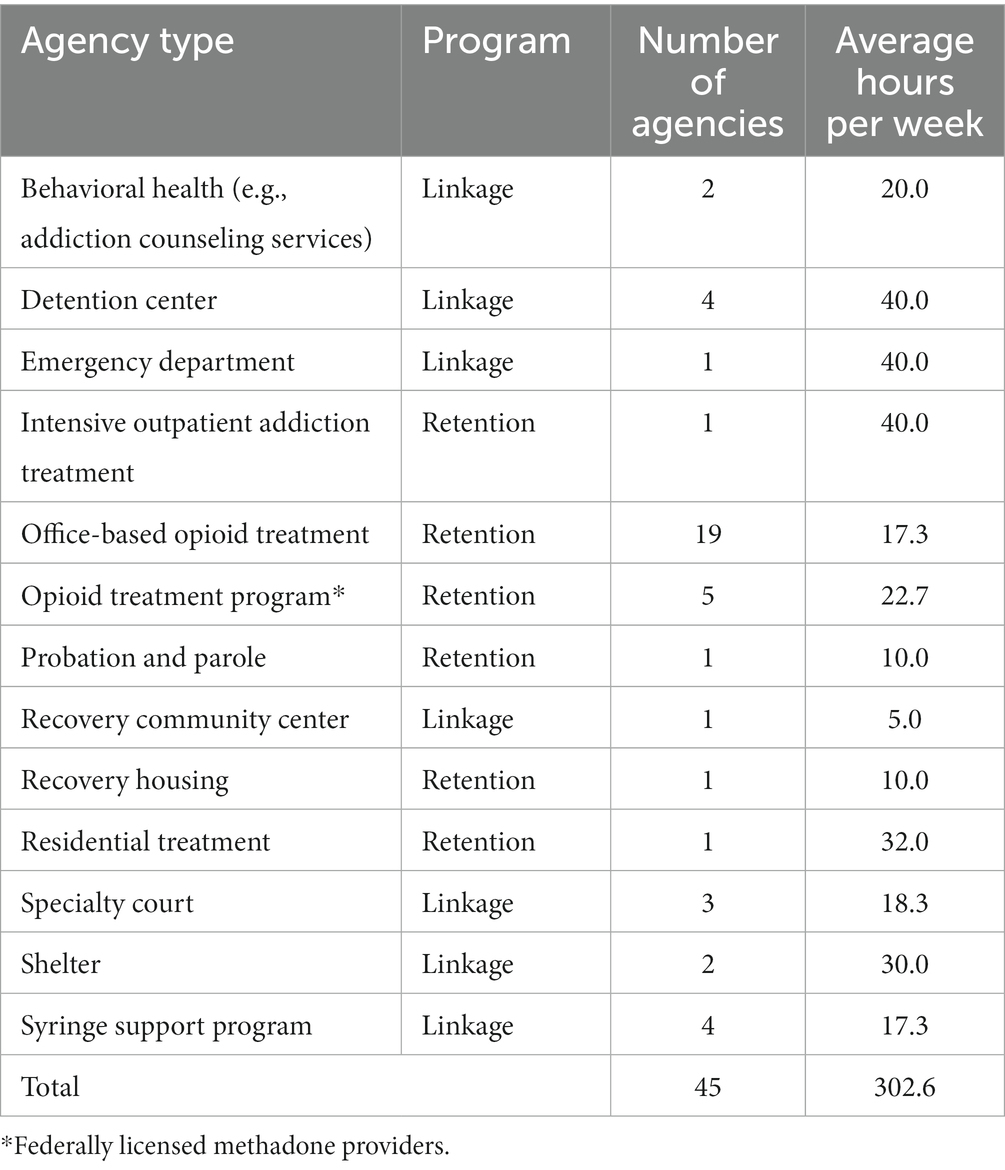

From December 2020 to February 2023, 93 RCs and 16 RC supervisors completed the training program. Two individuals completed the MOUD Competency evaluation twice before passing, and two ultimately failed and were not able to be placed within an agency. Both individuals who failed were not able to complete the final competency assessment due to personal reasons and did not participate in re-training. RCs were deployed at 45 agencies in linkage and retention programs across the eight initial counties from December 2020 through December 2022 at varying effort levels determined based upon agency need (Table 5). Most agencies (n = 31, 72%) chose to sustain the programs’ RC services through a state-funded grant after December 2022. The training materials developed by HCS, including a detailed training manual (see Supplementary Material (Data Sheet 1)), have been provided to VOH for continued internal use to enhance sustainability. Currently, there are 24 agencies within the second set of communities randomized to the intervention where HCS RCs are deployed.

4.2 Recovery coach training program experiences

Two RCs commented that the training program was unlike any other training experience, specifically the number of interactive portions and emphasis on skills-building. RC #2 described the interactive components (e.g., role plays in the MOUD Competency) as, “the best [training] experience at any job I’ve ever had… a lot of workplaces will throw you in, but having one-on-one [role plays to practice] was very helpful.” RC #3 explained that the MI skill building was noticeably different from trainings at previous jobs: “in other recovery jobs you are taught to be their friend and have to adapt skills on your own… this training taught me a whole other way to talk to people.”

RCs were also asked how the training program did or did not prepare them to help participants with MOUD linkage and/or retention. RC #1 commented that the MOUD Competency process was especially helpful in addressing misconceptions or stigma: “It’s stigmatized… [potential participants] say ‘you are not really sober if you are on these medications’… now I can explain the difference between opioid [physical] dependence and opioid use disorder… it’s good we go over it in detail like we do.” RC #3 reported hearing similar stigma at their linkage site (“you are trading one drug for another”) and shared that the HCS MOUD Flyer helped educate an individual who “was intrigued but wanted a better understanding” of how MOUD works. At their retention site, RC #2 was able to use their training and explain how buprenorphine works including the ceiling effect as a partial agonist to a participant who was still confused, “when she took buprenorphine why she was wasn’t getting the same effects [as the opioid she had been using].”

Finally, RCs were asked if the training challenged any previous views they had around MOUD and harm reduction. Two RCs came from a 12-step background and reported that the training program challenged their views around abstinence and MOUD. RC #2 reported that after completing the training program their “whole perspective has changed. I understand addiction better, understand chronic illness better, the disease process, how the medications work, and see how they help people live successful lives.” RC #1 explained that previously they viewed many harm reduction components as “enabling,” but was challenged during the Harm Reduction as a Recovery Pathway Training: “[the trainer] asked me ‘Well do you want [people in active opioid use] to die?’ and I said ‘No’… so it opened my eyes to look at it in a different light.”

5 Discussion and lessons learned

5.1 Discussion

We described the development of the novel training curriculum for the HCS-VOH Linkage and Retention RC Programs that provided education and skill-building for discussing MOUD with potential and enrolled participants. The training program supplemented the state-level peer support specialist certification with more in-depth education on topics such as MOUD, substance use disorder as a chronic disease, harm reduction, boundaries in peer support, and human research ethics. Specific skills-development training utilized role plays and allowed for demonstration of competencies and feedback in MI, OEND, and data collection. RCs demonstrated both their skills and knowledge in a final MOUD Competency evaluation.

The training curriculum is novel in two important ways. First, it focused on building a robust RC workforce aimed at addressing the opioid epidemic, specifically by increasing RC health literacy around MOUD and focusing on linkage to and retention on MOUD. Previous RC interventions that focused on OUD and MOUD outcomes were limited to linkage, did not address MOUD retention (16), or assure adequate RC health literacy around MOUD. Training RCs only for linkage to MOUD and not for retention leaves a critical gap in the continuum of care (18), and our retention program addresses this gap. This gap could also be addressed at the policy level by state-level stakeholders responsible for peer support specialist certification who could enhance competency requirements around MOUD.

Second, our training program addresses the dearth of comprehensive, standardized training for RCs in peer-based OUD interventions in the literature (11, 34). Training RCs to address MOUD misconceptions was especially important in addressing stigma in the community as evidenced by our case studies (“whole perspective has changed” RC#2) and emerging research on MOUD stigma (35, 36). We created components (e.g., MOUD Competency) so that all RCs would have the same, standardized training for discussing MOUD with participants, improving on previous studies that did not report extensive MOUD-specific training for their RCs (13, 37). Building this knowledge base around MOUD is critical for the RC workforce as more RC-led interventions are deployed for OUD.

Knowledge competency and skill-based learning are crucial components for workforce development for RCs. Currently, Kentucky peer support certification training is minimal (~30 h). This is likely inadequate to help all clients with recovery needs and could potentially cause unintentional harm. A minority of individuals with OUD have experience with MOUD (38). Thus, RCs without an evidence-informed understanding of MOUD may perpetuate stigma and negative opinions around MOUD to their clients, driving them away from linking to and staying retained in MOUD. Our results demonstrate the importance of assessing competence as some RCs need additional assistance to pass competency checks.

5.2 Lessons learned

There are prevalent myths and misconceptions around MOUD and harm reduction that change over time (e.g., Are fentanyl test strips legal to possess?), as well as periodic updates to best practice recommendations and misunderstandings from agencies about the role of the RC (e.g., They are not “sponsors” or “therapists”). Therefore, it is important to have continuing education and regularly scheduled check-ins during supervision. Also, there was a need for training to be continually offered due to the rapid turnover in the RC workforce.

6 Limitations

The case studies are a representative snapshot of the RC training experience and may not be generalizable to other settings. Future studies could systematically evaluate knowledge and attitudes toward MOUD and efficacy of the material pre- and post-training and deployment from a larger, more geographically diverse sample. Final data are not yet available on the effectiveness of the linkage and retention program, but we are encouraged by over 70% of the agency sites wanting to continue RC services after the HCS study intervention period. Additionally, while the programs are designed to reduce barriers to beginning or continuing MOUD, many of which are caused by structural barriers such as poverty and racism, the training curriculum does not explicitly address health equity. We plan to add trainings on these topics in the future, especially given the increasing disparities in MOUD access in Kentucky (39).

7 Conclusion

The HCS-VOH Linkage and Retention RC training curriculum was created specifically to reduce opioid-involved overdose deaths by developing an RC workforce to assist individuals with OUD to begin and/or continue MOUD. Our novel training equipped RCs with a foundational knowledge of MOUD and skills to address stigma and misconceptions around MOUD. Our training model shows promise as illustrated by the presented case studies and majority of venues across several settings (e.g., syringe service programs, detention centers, and MOUD clinics) desiring to continue employing RCs after the study period ended. Building a well-trained, evidence-informed RC workforce to help support those with OUD entering and continuing in MOUD treatment is critical to ending the opioid epidemic.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The HCS protocol (Pro00038088), which includes the HCS-VOH Linkage and Retention RC Programs, was approved by Advarra Inc., the HEALing Communities Study single Institutional Review Board (IRB). Written informed consent for all individuals receiving HCS services, (e.g., linkage and retention program participants) was waived by the IRB.

Author contributions

TM: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AF-B: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CC: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AR: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MG: Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JL: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. JB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PW-C: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration through the NIH HEAL (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Initiative under award numbers UM1DA049394 and UM1DA049406, (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04111939). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or the NIH HEAL InitiativeSM.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the recovery coaches and supervisors at Voices of Hope for their work in operating the linkage and retention programs and co-facilitating portions of the training program. The authors also wish to acknowledge the study’s implementation facilitators for their work in coordinating the recovery coaches’ agency placements. The authors also wish to acknowledge the participation of the HEALing Communities Study communities, community coalitions, Community Advisory Boards, agency partners, and state government officials who partnered with us on this study.

Conflict of interest

AF-B is a co-founder of Voices of Hope. JB is a contracted trainer for Voices of Hope and employed by Arthur Street Hotel, a non-profit harm reduction informed housing program for marginalized populations. SW has served as a scientific advisor/consulting related to novel MOUD development to Astra Zeneca, Cerevel, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and Braeburn Pharmaceuticals. ML has served as a research consultant to Berkshire Biomedical, Braeburn, Journey Colab and Titan Pharmaceuticals in the last 3 years.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1334850/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

RC, Recovery coach; VOH, Voices of Hope; HCS, HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-termSM) Communities Study.

Footnotes

1. ^ https://healingstudy.uky.edu/sites/default/files/2023-11/HCS-VOH%20RC%20Manual%20FINAL%2011.6.23.pdf

References

1. Ahmad, FB, Cisewski, JA, Rossen, LM, and Sutton, P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023).

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose mortality by state. (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm.

3. Wakeman, SE, Larochelle, MR, Ameli, O, Chaisson, CE, McPheeters, JT, Crown, WH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

4. Krawczyk, N, Rivera, BD, Jent, V, Keyes, KM, Jones, CM, and Cerdá, M. Has the treatment gap for opioid use disorder narrowed in the U.S.?: a yearly assessment from 2010 to 2019. Int J Drug Policy. (2022) 110:103786. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103786

5. Pasman, E, Kollin, R, Broman, M, Lee, G, Agius, E, Lister, JJ, et al. Cumulative barriers to retention in methadone treatment among adults from rural and small urban communities. Addict Sci Clin Pract. (2022) 17:35. doi: 10.1186/s13722-022-00316-3

6. Madden, EF, Prevedel, S, Light, T, and Sulzer, SH. Intervention stigma toward medications for opioid use disorder: a systematic review. Subst Use Misuse. (2021) 56:2181–201. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1975749

7. Sinkman, DH, and Dorchak, G. Using the Americans with disabilities act to reduce overdose deaths. Dept Just J Fed L Pract. (2022) 70:113.

8. Bardwell, G, Kerr, T, Boyd, J, and McNeil, R. Characterizing peer roles in an overdose crisis: preferences for peer workers in overdose response programs in emergency shelters. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2018) 190:6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.023

9. Randall-Kosich, O, Andraka-Christou, B, Totaram, R, Alamo, J, and Nadig, M. Comparing reasons for starting and stopping methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone treatment among a sample of white individuals with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med. (2020) 14:e44–52. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000584

10. Jack, HE, Oller, D, Kelly, J, Magidson, JF, and Wakeman, SE. Addressing substance use disorder in primary care: the role, integration, and impact of recovery coaches. Subst Abus. (2018) 39:307–14. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2017.1389802

11. Eddie, D, Hoffman, L, Vilsaint, C, Abry, A, Bergman, B, Hoeppner, B, et al. Lived experience in new models of Care for Substance use Disorder: a systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1052. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01052

12. O'Connell, MJ, Flanagan, EH, Delphin-Rittmon, ME, and Davidson, L. Enhancing outcomes for persons with co-occurring disorders through skills training and peer recovery support. J Ment Health. (2020) 29:6–11. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1294733

13. Cos, TA, LaPollo, AB, Aussendorf, M, Williams, JM, Malayter, K, and Festinger, DS. Do peer recovery specialists improve outcomes for individuals with substance use disorder in an integrative primary care setting? A program evaluation. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. (2020) 27:704–15. doi: 10.1007/s10880-019-09661-z

14. Winhusen, T, Wilder, C, Kropp, F, Theobald, J, Lyons, MS, and Lewis, D. A brief telephone-delivered peer intervention to encourage enrollment in medication for opioid use disorder in individuals surviving an opioid overdose: results from a randomized pilot trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2020) 216:108270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108270

15. Gertner, AK, Roberts, KE, Bowen, G, Pearson, BL, and Jordan, R. Universal screening for substance use by peer support specialists in the emergency department is a pathway to buprenorphine treatment. Addict Behav Rep. (2021) 14:100378. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2021.100378

16. Gormley, MA, Pericot-Valverde, I, Diaz, L, Coleman, A, Lancaster, J, Ortiz, E, et al. Effectiveness of peer recovery support services on stages of the opioid use disorder treatment cascade: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 229:109123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109123

17. Kleinman, MB, Anvari, MS, Bradley, VD, Felton, JW, Belcher, AM, Seitz-Brown, CJ, et al. "sometimes you have to take the person and show them how": adapting behavioral activation for peer recovery specialist-delivery to improve methadone treatment retention. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2023) 18:15. doi: 10.1186/s13011-023-00524-3

18. Magidson, JF, Regan, S, Powell, E, Jack, HE, Herman, GE, Zaro, C, et al. Peer recovery coaches in general medical settings: changes in utilization, treatment engagement, and opioid use. J Subst Abus Treat. (2021) 122:108248. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108248

19. Walsh, SL, El-Bassel, N, Jackson, RD, Samet, JH, Aggarwal, M, Aldridge, AP, et al. The HEALing (helping to end addiction long-term SM) communities study: protocol for a cluster randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2020) 217:108335. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108335

20. Winhusen, T, Walley, A, Fanucchi, LC, Hunt, T, Lyons, M, Lofwall, M, et al. The opioid-overdose reduction continuum of care approach (ORCCA): evidence-based practices in the HEALing communities study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2020) 217:108325. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108325

21. Ashford, RD, Brown, A, Canode, B, Sledd, A, Potter, JS, and Bergman, BG. Peer-based recovery support services delivered at recovery community organizations: predictors of improvements in individual recovery capital. Addict Behav. (2021) 119:106945. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106945

22. Association of Recovery Community Organizations. National standards of best practices for recovery community organizations (RCOs). (2022). Available at: https://facesandvoicesofrecovery.org/rco-best-practices/.

23. Feld, H, Elswick, A, Goodin, A, and Fallin-Bennett, A. Partnering with recovery community centers to build recovery capital by improving access to reproductive health. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2022) 55:692–700. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12836

24. Chandler, R, Nunes, EV, Tan, S, Freeman, PR, Walley, AY, Lofwall, M, et al. Community selected strategies to reduce opioid-related overdose deaths in the HEALing (helping to end addiction long-term SM) communities study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2023) 245:109804. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109804

25. Elswick, A, and Fallin-Bennett, A. Voices of hope: a feasibility study of telephone recovery support. Addict Behav. (2020) 102:106182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106182

26. Providers Clinical Support System. (2023). SUD 101 core curriculum (2023). Available at: https://pcssnow.org/education-training/sud-core-curriculum/ (Accessed November 7, 2023).

27. SMART Recovery. SMART recovery: Life beyond addiction. (2023). Available at: https://www.smartrecovery.org (Accessed November 7, 2023).

28. Gale, T, Mills, C, and Cross, R. Socially inclusive teaching. J Teach Educ. (2017) 68:345–56. doi: 10.1177/0022487116685754

29. Ambrose, SA, Bridges, MW, DiPietro, M, Lovett, MC, and Norman, MK. How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. New York: John Wiley and Sons (2010).

30. Ntim, WN, Annan-Brew, RK, Asamoah-Gyimah, K, Owusu-Amoako, J, Adzrolo, B, and Adobah, E. Handling formative assessment and learning: the role of classroom teachers. Psychology. (2023) 14:1260–7. doi: 10.4236/psych.2023.148069

31. Winkelmes, MA, Boye, A, and Tapp, S. Transparent design in higher education teaching and leadership: A guide to implementing the transparency framework institution-wide to improve learning and retention. New York: Taylor and Francis (2023).

32. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Core competencies for peer Workers in Behavioral Health Services Bringing Recovery Supports to scale technical assistance center strategy (BRSS TACS). (2015).

33. Connecticut Community for Addiction Recovery (CCAR). Recovery coach academy. (2023). Available at: https://addictionrecoverytraining.org/training-products/ (Accessed October 24, 2023).

34. Satinsky, EN, Kleinman, MB, Tralka, HM, Jack, HE, Myers, B, and Magidson, JF. Peer-delivered services for substance use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Drug Policy. (2021) 95:103252. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103252

35. Connolly, CM, and Milbourne, CC. Medication assisted treatment of opioid addiction: a qualitative review of program challenges. J Ethnogr Qual. Res. (2021) 16:1–17.

36. Witte, TH, Jaiswal, J, Mumba, MN, and Mugoya, GCT. Stigma surrounding the use of medically assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. Subst Use Misuse. (2021) 56:1467–75. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1936051

37. Dahlem, CHG, Scalera, M, Anderson, G, Tasker, M, Ploutz-Snyder, R, McCabe, SE, et al. Recovery opioid overdose team (ROOT) pilot program evaluation: a community-wide post-overdose response strategy. Subst Abus. (2021) 42:423–7. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1847239

38. Mauro, PM, Gutkind, S, Annunziato, EM, and Samples, H. Use of medication for opioid use disorder among US adolescents and adults with need for opioid treatment, 2019. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e223821. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3821

Keywords: medication for opioid use disorder, peer support, opioid use disorder treatment, recovery coach, peer recovery, training

Citation: Moffitt T, Fallin-Bennett A, Fanucchi L, Walsh SL, Cook C, Oller D, Ross A, Gallivan M, Lauckner J, Byard J, Wheeler-Crum P and Lofwall MR (2024) The development of a recovery coaching training curriculum to facilitate linkage to and increase retention on medications for opioid use disorder. Front. Public Health. 12:1334850. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1334850

Edited by:

Marc N. Potenza, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Cosmas Zyambo, University of Zambia, ZambiaAnnabelle (Mimi) Belcher, University of Maryland, United States

Copyright © 2024 Moffitt, Fallin-Bennett, Fanucchi, Walsh, Cook, Oller, Ross, Gallivan, Lauckner, Byard, Wheeler-Crum and Lofwall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Trevor Moffitt, trevor.moffitt@uky.edu

Trevor Moffitt

Trevor Moffitt Amanda Fallin-Bennett2,3

Amanda Fallin-Bennett2,3 Sharon L. Walsh

Sharon L. Walsh Christopher Cook

Christopher Cook Molly Gallivan

Molly Gallivan Phoebe Wheeler-Crum

Phoebe Wheeler-Crum Michelle R. Lofwall

Michelle R. Lofwall