1 Introduction and related work

The quantum approximate optimization algorithm (Farhi et al., 2014)/quantum alternating operator ansatz (Hadfield et al., 2019) (QAOA) is a widely studied hybrid algorithm for approximately solving combinatorial optimization problems encoded into the ground state of a Hamiltonian. Given an objective function , the problem Hamiltonian is defined as . Thus, the ground states of correspond to the minima of the objective function. In the general framework of QAOA, a parameterized quantum state is prepared as follows:

Starting from an initial state , the algorithm alternates between applying the phase-separation operator and the mixing operator . The goal is to optimize the parameters such that is minimized.

Since the original proposal of QAOA, several extensions and variants have been introduced. One such extension is ADAPT-QAOA (Zhu et al., 2022), which iteratively adds only the terms that most contribute to lowering the expectation value. Another variant is R-QAOA (Bravyi et al., 2020), which progressively removes variables from the Hamiltonian until the reduced instance can be classically solvable. A third extension, WS-QAOA (Egger et al., 2021), incorporates solutions from classical algorithms to warm-start the QAOA process. When a given problem has constraints, the design of mixers is vital. For constrained problems, the design of mixers is crucial. A well-known example is the -mixer (Hadfield et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020), which restricts evolution to “k-hot” states. GM-QAOA (Bartschi and Eidenbenz, 2020) uses Grover-like operators for all-to-all mixing of more general feasible subsets. The mixing operator of GM comprised a circuit that prepares the uniform superposition of all feasible states, its inverse , and a multi-controlled rotational phase shift gate. Inspired by the stabilizer formalism, the LX-Mixer (Fuchs and Bassa, 2024; Fuchs et al., 2022) is a generalization of the above methods that provides a flexible framework that allows for tailored mixing within the feasible subspace.

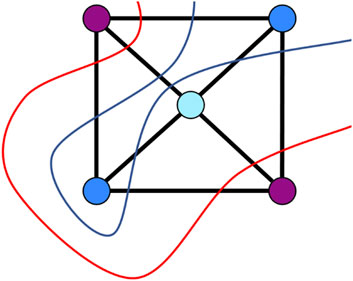

To increase the practical relevance of QAOA, encoding problems with integer values, rather than binary variables, into qubit systems is an important area of research. This process generally introduces considerable flexibility in encoding choices, affecting not only the number of qubits and controlled operations needed but also the complexity of the optimization landscape and the quality of the approximation ratios that can be achieved. In this study, we explore various encoding schemes for the MAX -CUT problem into qubit systems, building on and improving earlier research (Fuchs et al., 2021). This problem has numerous applications, including the placement of television commercials in program breaks, arrangement of containers on a ship with bays, partitioning a set of items (e.g., books sold by an online shop) into subsets, product module design, frequency assignment, scheduling, and pattern matching (Aardal et al., 2007; Ram Gaur et al., 2008). Given a weighted undirected graph , the MAX -CUT problem consists of finding a maximum-weight -cut. This involves partitioning the vertices into subsets such that the sum of the weights of the edges between vertices in different subsets is maximized (Figure 1). By assigning a label to each vertex and defining , the optimization problem for MAX -CUT can be formulated as

Here, is the weight of edge . The function is commonly referred to as the “cost function.” For , the MAX -CUT problem becomes the well-known MAX CUT problem. The MAX -CUT problem is NP-complete, and it has been demonstrated that no polynomial-time approximation scheme exists for unless P = NP (Alan and Jerrum, 1997). A randomized approximation algorithm for (1) has an approximation ratio if

where denotes an optimal solution.

Expressing the solutions as strings of -dits as in Equation 1 is a natural extension of the MAX (2-)CUT problem to . However, most quantum devices work with a two-level system, so we need to make a suitable encoding on a qubits system (Fuchs et al., 2021; Hadfield et al., 2019). One-hot encoding uses bits for each vertex, where the single bit that is 1 encodes which set/color the vertex belongs to. Using this encoding requires qubits. However, not being a power of 2 results in more computational states per vertex than there are colors. The corresponding subspaces need to be dealt with in a suitable fashion. The Grover or the LX-mixer (which becomes the XY-mixer in this case) can be readily applied. However, the ratio of the dimension of the feasible states to the system size is , which becomes exponentially small for increasing . Therefore, it is advantageous to use a binary encoding, which does not have this problem. For a given , we encode the information of a vertex belonging to one of the sets by , which requires

qubits. Here, means rounding up to the nearest integer. Binary encoding requires qubits, which is exponentially fewer than required by one-hot encoding. The resulting problem Hamiltonian can be written as the sum of local terms, that is,

where is the weight of the edge between vertices and . Furthermore, the local term can be expressed as

where is a set of index pairs representing equivalent colors under an equivalence relation. From the definition, has eigenvalue for a state if and if not. The phase separating operator differs from only by a scalar factor and a global phase, so it is sufficient to realize the latter.

More formally, an equivalence relation is defined on , where consists of all pairs such that . For example, if the equivalence relation defines the following equivalence classes: For convenience, we can work with a generating set. Suppose is a relation on the set . The equivalence relation on generated by a , denoted , is then the smallest equivalence relation on that contains , which can be obtained by the reflexive, symmetric, and transitive closure (in that order). Hence, only the non-trivial relations must be specified, and the above example can be generated by the closure of the relation which generates . The set of colors in the context of MAX -CUT is then the set of equivalence classes induced by , denoted

with each equivalence class given by

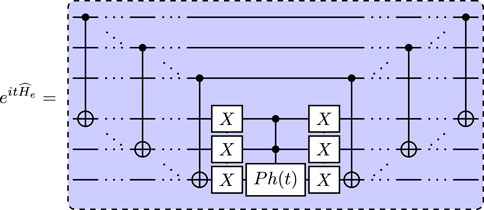

We recognize that the phase separating operator—the real time evolution of —acts by applying a phase on a specific subsets of all computational basis states. When these subsets are sparse, such unitaries can be efficiently realized (Fuchs and Bassa, 2025): let be the projector onto a subspace given by set of computational basis states . The unitary operator can be realized by a circuit for mapping the (indexed) states of to the first computational basis states, which can be achieved by where is a transposition gate. It follows directly that

Therefore, we find that from which it follows that the exponential has the form

where is a low-pass controlled phase shift gate as defined in Fuchs and Bassa (2025). For a general subspace, the overall circuit requires CX gates and T gates.

When the subspace is given by the span of a Pauli X-orbit as defined in Fuchs and Bassa (205), the overall circuit requires only CX gates and T gates. Here, is a given tolerance for approximating rotational gates. Even though might not be a Pauli X-orbit subspace, we can always decompose into a direct sum of Pauli X-orbit subspaces and apply the construction individually on the subspaces of the decomposition. We will therefore here aim to divide the subspaces such that they are Pauli X-orbit subspaces if it leads to an efficient circuit.

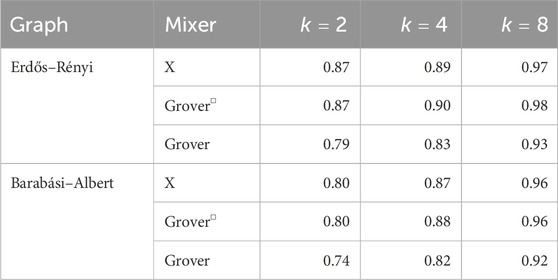

An overview of possible encoding techniques is provided in Figure 2. When is not a power of 2, we must deal with the fact that we have non-trivial equivalence classes . There are two ways to deal with this. The first is to directly implement the phase separating Hamiltonian on the full Hilbert space (Fuchs et al., 2021) or restrict the evolution onto the relevant subspace. The main contributions of this study are for the cases when is not a power of 2. We introduce:

A systematic way to implement the phase separating Hamiltonian, resulting in a reduction of the complexity of the resulting circuit using the theorems from Fuchs and Bassa (2025).

A method to directly work with a feasible subspace with a suitable state preparation and constrained mixer in Section 4.

More balanced sets of equivalent colors, which help improve the resulting cost landscape, in Section 3.

We also employ the Grover mixer to all cases, indicating that the resulting landscape might be favorable. Throughout this study, the notation means an controlled gate. For example, a Toffoli gate is , and is the controlled phase shift gate, where we mostly omit the parameter. We will make use of the following notation for multi-controlled unitary (MCU) gates

where is index control and target qubits, and specifies the control condition.

2 Binary encodings when k is a power of 2

When , the equivalence relation for the problem Hamiltonian in Equation 2 becomes trivial—that is, —and hence

By definition, is a projection operator of rank onto the subspace spanned by , consisting of all states with identical basis vectors in both registers. We notice that the set is Pauli X-orbit generated as defined in Fuchs and Bassa (2025) since it can be written as

that is, the orbit of the computational basis state under the group action of . Here, denotes the subgroup generated by a subset of the Pauli group. To construct the phase separating operator for our concrete case, we follow the proof of Theorem 3 in Fuchs and Bassa (2025) which recursively gives us the following permutation matrix in each step, , which leaves the all-zero state unchanged and maps the state to . Overall, this leads to

resulting in the following circuit:

The number of controlled gates required for realizing the mixer and phase separating operators are as follows.

Realizing through Equation 5 requires gates and 1 gate. Alternatively, we can also do a direct decomposition of in the Pauli basis and perform Pauli evolution gates with this. For , the first approach needs 2, (4 and 1 ) and (6 and 1), whereas the Pauli evolution needs 2, 10, and 34 per gate, respectively. Thus, it is better for these cases to realize the phase separation with the circuit given in Equation 5 and not through Pauli evolution.

The X mixer does not require any controlled gates, the Grover mixer needs one gate, and the needs gates, where the box product is defined in Equation 11.

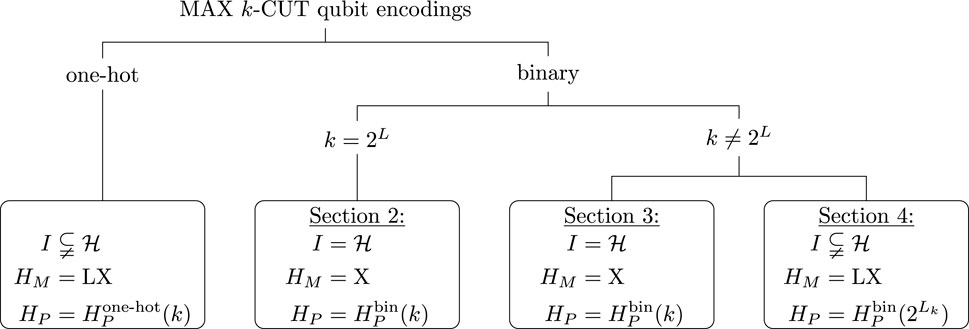

We numerically test the performance of the resulting QAOA algorithm on the same instances as in Fuchs et al. (2021), given in Supplementary Appendix A. Table 1 shows that the approximation ratios achieved are very good for all cases. An overview of the energy/approximation ratio landscapes are provided in Supplementary Appendix Table A3.

3 Binary encodings for using the full Hilbert space

When is not a power of 2, the equivalence relation for the problem Hamiltonian in Equation 2 becomes non-trivial. One way to deal with this is what we will refer to as -encoding, where we encode the color into all states with for . This gives us

Of course, in general there are many ways to define colors through an equivalence relation , which influences the cardinality of the equivalence classes. There is, however, always a way to define it such that the maximum cardinality of all equivalence classes is at most 2. In the following, we denote such a relation as . This also influences the rank of the Hamiltonian . In the following, we make a concrete construction of the Hamiltonians for .

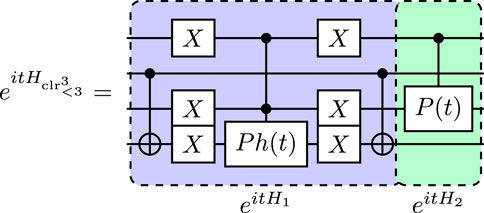

3.1 The case

For , , which means that the three colors are given by . The subspace of the projector is given by . We can realize the phase separating operator using the low-pass controlled phase shift gate in the permuted basis, as described in Fuchs and Bassa (2025). However, to reduce the circuit complexity, we can instead divide the subspace in two Pauli X-orbit generated subspaces, and , which results in the circuit

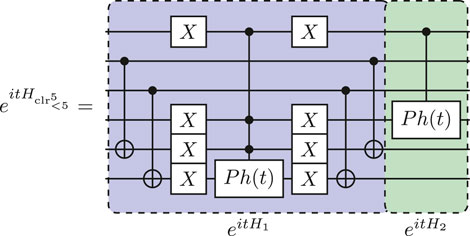

3.2 The case

For , , which means that the five colors are given by . We can divide into two Pauli X-orbit generated subspaces. The first subspace containing four states is related to the first four colors , forming the subset . The second subspace contains all states related to the last degenerated color , forming . The resulting circuit is given by.

which realizes the phase separating unitary with one single- and one triple-controlled phase shift gate.

Looking at the case for and , it becomes clear that the structure of the circuit can be generalized for with . The feasible subspace can always be divided into two Pauli X-orbit generated subspaces, , related to the first color states characterized by bitstrings , where the first digit of is always 0. The second subspace related to the degenerate color is given by . From this, we can conclude that the resulting circuit is a generalization of Equation 6, where consists of the circuit where the CX between the first and -th qubit is omitted and a phase shift gate the with target on the last qubit controlling the first and last (without the last) qubits. The circuit for is a phase shift gate with control of the first and target on the -th qubit.

A second possibility is to encode the problem so that the cardinality of the equivalence classes is minimized. This can, for instance, be achieved by . In this case, the five colors are given by and the according Pauli X-orbit generated subspaces are

The resulting circuit for the phase separating operator is

where the gates in the gray box cancel to the identity.

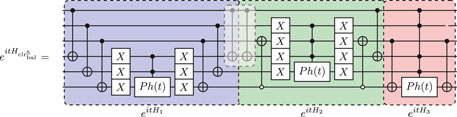

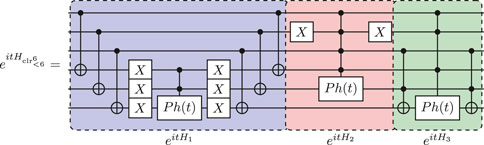

3.3 The case

For , we have that , meaning that the six colors are given by . We can divide into the following two Pauli X-orbit generated subspaces , together with , which cannot be generated by a Pauli X-orbit. The resulting circuit is given by

The circuit for the real time evolution of contains a Toffoli gate for realizing the basis change since the subspace is not Pauli X-orbit generated. In particular, the circuit for the second term can be derived considering that if we exchange the state and using a transposition gate (in this case a 5-controlled not-gate ), the new set becomes Pauli X-orbit generated. Since all the states in the subset have the bit value 1 in position 0,1,3,5 we can instead replace the use of by a Toffoli gate .

In order to encode the problem in a balanced way, we can use . Since , we can divide into the subspace and shown in Equation 7; the resulting circuit is shown in Equation 10, but the circuit for is omitted.

3.4 The case

For , , which means that the seven colors are given by . Since , we can divide into the subspace and shown in Equation 7, where the resulting circuit is shown in Equation 10, but the circuit for is omitted. Notice here too that the two adjacent gates between the circuits for and cancel.

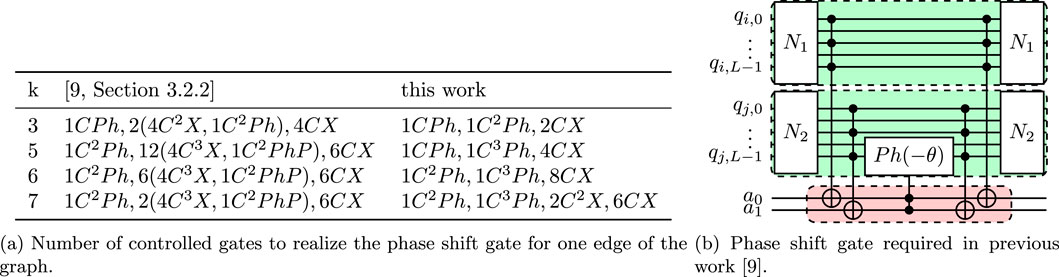

3.5 Resource analysis

When is not a power of 2, the method presented in [9, Section 3.2.2] is not optimal in terms of resource efficiency; for each edge of the graph, it requires the circuit shown in Equation 5 and times the circuit shown in Figure 3b, where . Each of these individual circuits uses four -gates, and one gate and requires the use of two ancillary qubits. Concretely, for each edge, of these circuits are needed for , respectively, with the cost shown in Figure 3a. The method derived from the theorem in Fuchs and Bassa (2025) on the other hand, requires much fewer entangling gates and does not require ancilla qubits. For a single edge, the size of the relevant subspace scales as in the encoding using and as in the encoding using . This quadratic scaling in the latter case is due to the degeneracy of the highest color level, which leads to valid computational basis states. From the theorem in Fuchs and Bassa (2025), the overall gate complexity for the two encoding strategies is as follows.

Encoding using : CNOTs and single-qubit rotations.

Encoding using : CNOTs and single-qubit rotations.

Here, we have explicitly constructed circuits for using a decomposition similar to that in Fuchs and Bassa (2025), but with a key optimization: we partitioned subspace into ad hoc sums of Pauli -orbits. This additional structure further reduces the implementation cost. See Supplementary Appendix Table A3a for a comparison.

4 Binary encodings for using subspaces

When is not a power of 2, there is an alternative to encoding the problem in the full Hilbert space as presented in Section 3. Instead, the evolution of the QAOA can be restricted to a suitably chosen subspace spanned by a set consisting of computational basis states. Consequently, we need a way to prepare an initial state in a -dimensional subspace for each vertex of the graph and a mixer constrained to this subspace. We observe that

meaning we can use the circuit for the power-of-2 case. Overall, this approach shifts complexity from the phase separating Hamiltonian to the mixer.

4.1 Initial state

For the MAX -CUT problem, one possibility is to define the subspace for each vertex through . Since the feasible bit-strings admit a Cartesian product structure, the feasible subspace becomes a tensor product of the form

An initial state can be prepared as the uniform superposition of all feasible basis states—

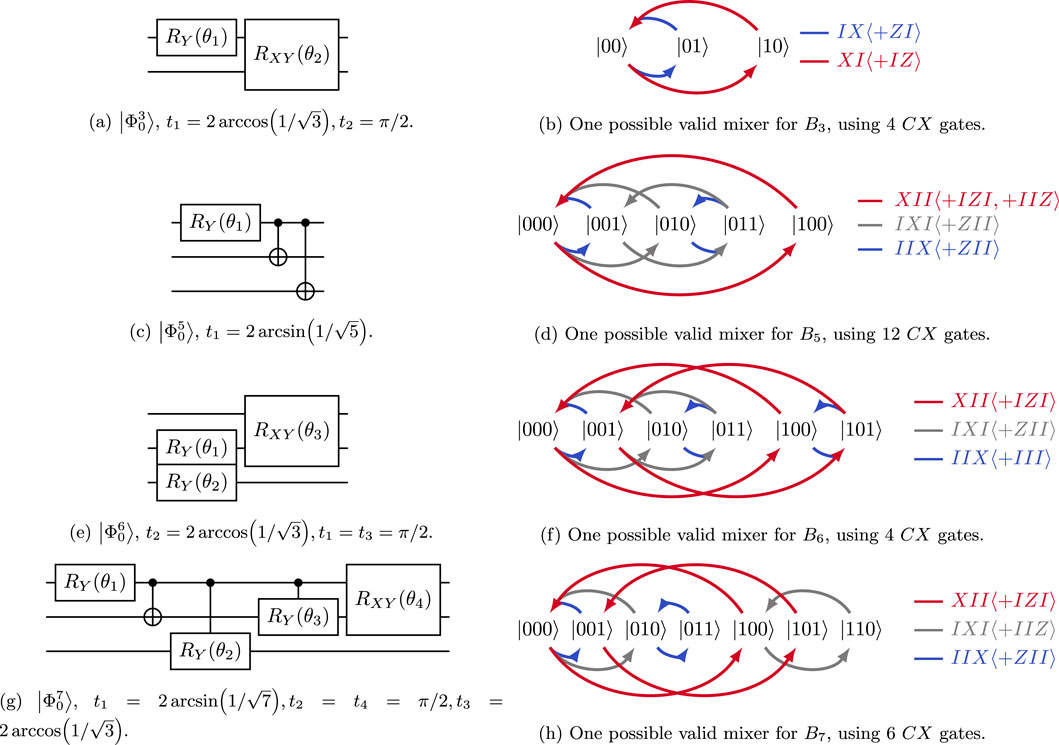

This can, in general, be efficiently prepared with a gate complexity and circuit depth of only (Shukla and Vedula, 2024). One way to realize the initial state for is shown in Figures 4a–h.

4.2 Constrained mixer

Given a feasible subspace , a mixer is then called valid (Hadfield et al., 2019) if it preserves the feasible subspace, that is,

and if it provides transitions between all pairs of feasible states, where for each pair of computational basis states there exist and , such that

Apart from the Grover mixer, we consider here constraint-preserving mixers in the stabilizer form (Fuchs and Bassa, 2024), in which case the Hamiltonian can be written as

where is a multi-index, , and is a projection onto . Furthermore, is a subspace fulfilling . The free parameter must be chosen such that we have a valid mixer. Let be a minimal generating set of the stabilizer group defining the code subspace . We can choose the projection operator to be of the form

For more details, see Fuchs and Bassa (2024). In the following, we will use the notation

Given the independence of the different color constraints for each vertex of the problem, we can then define the following LX-mixer Hamiltonian

where the Cartesian or Box product is defined as

It can be shown that if is a valid mixer, is constructed in this way (Fuchs and Bassa, 2024). Valid mixers with optimal cost in terms of gates are shown in Figure 4 for . We note that this choice is not unique and that other mixers are possible as well.

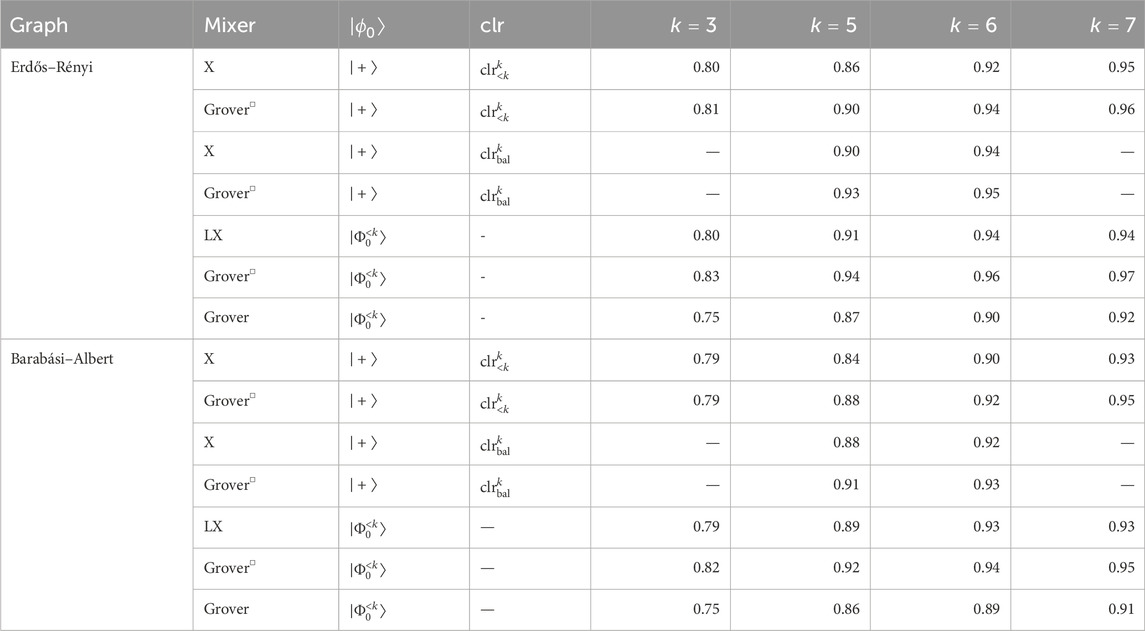

5 Simulations

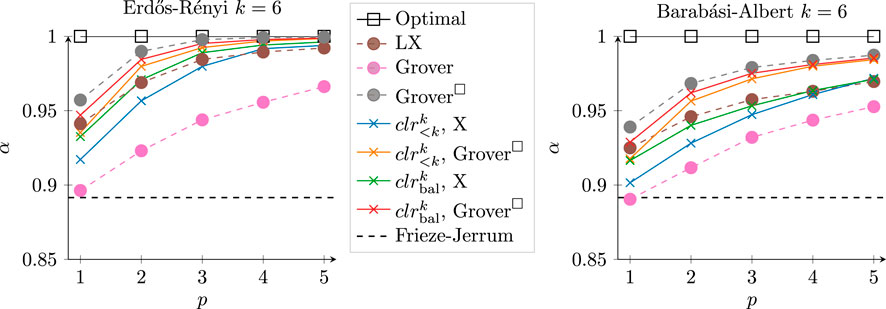

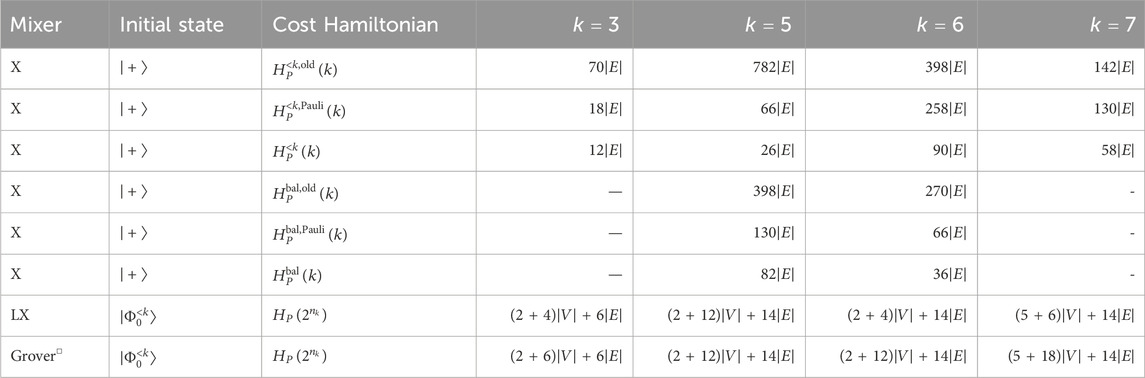

We perform numerical simulations for an unweighted Erdős–Rényi graph and a weighted Barabási–Albert graph with ten vertices (Supplementary Appendix A). Since the case where is a power of 2 is presented in Section 2, we will focus on evaluating the methods presented in Sections 3 and 4. Using an ideal simulator, we compare the results for the binary encoding with the standard -mixer and different choices of equivalence relations to encode the colors, and we compare the subspace encoding with different choices of mixers. The resulting energy landscapes are provided in Supplementary Appendix A. As expected, the landscapes are periodic in when using the - and Grover-mixer, whereas the landscape associated with the LX-mixer is generally not. The resulting approximation ratios are shown in Table 2. Overall, the subspace-encoding using the mixer achieves the highest values for these two graphs, although with only a small distance to the LX-mixer. We can also see that balancing the bin sizes for the different colors has a very positive effect on the approximation ratio when using the full Hilbert space and the X-mixer. The effect of increasing the depth is shown in Table 3, which is exemplified for . Note that the behavior for , and 7 were very similar. Overall, the achieved the best convergence for these two graphs, irrespective of whether the full Hilbert space or the subspace method was used.

We note, however, that the averaged approximation ratio achieved should be carefully considered with respect to the required circuit depth. For encoding in the full Hilbert space, we can use the X-mixer, but the phase-separation operator requires a deeper circuit. For encoding into a subspace, we can use the phase-separation operator for the power-of-2 case (leading to a more shallow circuit), but the circuit for the constrained preserving mixer is deeper. An indication of the cost is given in Table 4, where we used the compiler from qiskit, assuming full connectivity. Note that for a sparse graph and for a fully connected graph . Therefore, for graphs with sufficient connectivity, the subspace encoding uses fewer resources than the encoding into the full Hilbert space.

6 Conclusion

This study presents advances in encoding the MAX -CUT problem into qubit systems, with a focus on cases where is not a power of 2. We present new ways of encoding that significantly reduce the resource requirements compared to previous approaches. In our implementation, we compared two different encodings using the full Hilbert space. Empirically, we observed that the balanced encoding consistently produced more compact circuits and achieved higher approximation ratios across all tested circuit depths and for both graph instances. We believe that this improvement is linked to the structure of the cost Hamiltonian, specifically the reduced degeneracy induced by the balanced encoding, which may lead to a smoother optimization landscape. However, we acknowledge that we do not currently have a theoretical guarantee that the balanced encoding results in fewer barren plateaus than the encoding. While the empirical results suggest an improvement in trainability, a rigorous analysis of the gradient landscape remains an open direction for future work. Balanced color sets and constrained mixers demonstrate notable improvements in optimization landscapes and approximation ratios.

While our method is designed for digital quantum architectures, extending it to quantum annealers is possible in principle but practically nontrivial. Quantum annealing hardware is restricted to 2-local Ising Hamiltonians, whereas our encoding yields k-local PUBO terms for . Mapping these higher-order terms to 2-local form would require ancillary qubits and penalty constraints, introducing significant overhead and embedding complexity (Nagies et al., 2025) or the use of hybrid techniques as exposed in (Wurtz et al., 2024). In the future, we plan to do a careful analysis of which ansatz is preferable when is not a power of 2, using a suite of graph instances. The analysis should take into account the overall circuit depth, the achieved approximation ratio for increasing depth size, as well as if the landscape has barren plateaus or many “bad” local minima.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

FF: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Visualization, Data curation, Project administration, Formal Analysis, Methodology. RP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. FL: Writing – review and editing, Software, Data curation.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We would like to thank for funding of the work by the Research Council of Norway through project number 332023.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Terje Nilsen at Kongsberg Discovery for the access to an H100 GPU for the simulations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frqst.2025.1636042/full#supplementary-material

References

Aardal, K. I., van Hoesel, S. P. M., Koster, A. M. C. A., Mannino, C., and Sassano, A. (2007). Models and solution techniques for frequency assignment problems. Ann. Operations Res. 153 (1), 79–129. doi:10.1007/s10479-007-0178-0

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alan, F., and Jerrum, M. (1997). Improved approximation algorithms for maxk-cut and max bisection. Algorithmica 18 (1), 67–81. doi:10.1007/BF02523688

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bartschi, A., and Eidenbenz, S. (2020). “Grover mixers for qaoa: shifting complexity from mixer design to state preparation,” in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE) (IEEE), 72–82. doi:10.1109/qce49297.2020.00020

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bravyi, S., Kliesch, A., Koenig, R., and Tang, E. (2020). Obstacles to variational quantum optimization from symmetry protection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125 (26), 260505. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.260505

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Egger, D. J., Mareček, J., and Woerner, S. (2021). Warm-starting quantum optimization. Quantum 5, 479. doi:10.22331/q-2021-06-17-479

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., and Gutmann, S. (2014). A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv Prepr. arXiv:1411.4028. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1411.4028

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fuchs, F. G., and Bassa, R. P. (2024). Lx-mixers for qaoa: optimal mixers restricted to subspaces and the stabilizer formalism. Quantum 8, 1535–11. doi:10.22331/q-2024-11-25-1535

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fuchs, F. G., and Bassa, R. P. (2025). Compact circuits for constrained quantum evolutions of sparse operators. arXiv. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2504.09133

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fuchs, F. G., Kolden, H. Ø., Henrik Aase, N., and Sartor, G. (2021). Efficient encoding of the weighted MAX $$k$$-CUT on a quantum computer using QAOA. SN Comput. Sci. 2 (2), 89. doi:10.1007/s42979-020-00437-z

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fuchs, F. G., Olsen Lye, K., Nilsen, H. M., Stasik, A. J., and Sartor, G. (2022). Constraint preserving mixers for the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Algorithms 15 (6), 202. doi:10.3390/a15060202

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hadfield, S., Wang, Z., Rieffel, E. G., O’Gorman, B., Venturelli, D., and Biswas, R. (2017). “Quantum approximate optimization with hard and soft constraints,” in Proceedings of the second international workshop on post moores era supercomputing, 15–21. doi:10.1145/3149526.3149530

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hadfield, S., Wang, Z., O’Gorman, B., Rieffel, E. G., Venturelli, D., and Biswas, R. (2019). From the quantum approximate optimization algorithm to a quantum alternating operator ansatz. Algorithms 12 (2), 34. doi:10.3390/a12020034

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nagies, S., Geier, K. T., Akram, J., Bantounas, D., Johanning, M., and Hauke, P. (2025). Boosting quantum annealing performance through direct polynomial unconstrained binary optimization. Quantum Sci. Technol. 10 (3), 035008. doi:10.1088/2058-9565/adcae6

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ram Gaur, D., Krishnamurti, R., and Kohli, R. (2008). The capacitated max k-cut problem. Math. Program. 115 (1), 65–72. doi:10.1007/s10107-007-0139-z

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shukla, A., and Vedula, P. (2024). An efficient quantum algorithm for preparation of uniform quantum superposition states. Quantum Inf. Process. 23 (2), 38–1332. doi:10.1007/s11128-024-04258-4

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wang, Z., Rubin, N. C., Dominy, J. M., and Rieffel, E. G. (2020). XY mixers: analytical and numerical results for the quantum alternating operator ansatz. Phys. Rev. A 101 (1), 012320. doi:10.1103/physreva.101.012320

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wurtz, J., Sack, S. H., and Wang, S.-T. (2024). Solving non-native combinatorial optimization problems using hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. IEEE Trans. Quantum Eng. 5, 1–14. doi:10.1109/tqe.2024.3443660

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, L., Wang, S.-T., Choi, S., Pichler, H., and Lukin, M. D. (2020). Quantum approximate optimization algorithm: performance, mechanism, and implementation on near-term devices. Phys. Rev. X 10 (2), 021067. doi:10.1103/physrevx.10.021067

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhu, L., Tang, Ho L., Barron, G. S., Calderon-Vargas, F. A., Mayhall, N. J., Barnes, E., et al. (2022). Adaptive quantum approximate optimization algorithm for solving combinatorial problems on a quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Res. 4 (3), 033029. doi:10.1103/PhysRevResearch.4.033029

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Franz G. Fuchs

Franz G. Fuchs Ruben Pariente Bassa

Ruben Pariente Bassa Frida Lien2

Frida Lien2