- 1Quantum Technology Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

- 2Department of Physics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

- 3DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory, Adelphi, MD, United States

- 4Element Six Global Innovation Centre, Didcot, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom

- 5Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

- 6Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, United States

Ensembles of nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond are versatile quantum sensors with broad applications in the physical and life sciences. The concentration of neutral substitutional nitrogen (

1 Introduction

Nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond are a leading quantum sensing platform due to favorable optical and electronic spin properties (Barry et al., 2020), with wide-ranging applications, including in condensed matter physics (Ku et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Rovny et al., 2024), electronics systems (Turner et al., 2020; Garsi et al., 2024), geoscience (Glenn et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2023), and life science (Barry et al., 2016; Aslam et al., 2023; Schirhagl et al., 2014). Extensive research has focused on magnetic sensing and imaging using ensembles of NV centers. However, experimentally realized sensitivities remain several orders of magnitude below the fundamental spin-projection limit (Hart et al., 2021; Barry et al., 2024). A recent review (Barry et al., 2020) highlights strategies for further improving sensitivity, including extending spin coherence times through advanced pulse sequences and targeted material engineering.

A key material engineering parameter affecting NV ensemble magnetic sensing performance is the concentration of neutral substitutional nitrogen (

In prior work (Edmonds et al., 2021), we synthesized chemical vapor deposition (CVD) diamonds with relatively high

Figure 1. (a) NV ensemble DC magnetic field sensitivity estimated using the simplified metric

Realizing these sensing advantages with low-nitrogen diamond materials necessitates careful control of other material parameters. These include 12C isotopic purification to minimize 13C nuclear spin noise, optimization of growth conditions to reduce strain and other unwanted defect densities, and controlled irradiation and annealing processes to achieve high

In this work, we report the synthesis and characterization of low-

2 Material and experimental methods

2.1 Parameters relevant to sensitivity

The photon shot-noise-limited magnetic sensitivity of an NV ensemble Ramsey-based DC magnetometry protocol is given by:

where

The first two terms represent the spin-bath noise from substitutional nitrogen and residual 13C in the diamond lattice, with their contributions scaling directly with respective concentrations. The third term accounts for NV–NV dipolar interactions, which can be significant in high NV density samples created by irradiation and annealing. The last two terms account for spatial variation (inhomogeneity) in lattice strain and the applied bias magnetic field. Quantification of

The NV optical excitation intensity further affects the photon-shot-noise-limited sensitivity by modifying the

2.2 Diamond synthesis and treatment

The diamond samples studied here are grown on a diamond substrate by Element Six using microwave-plasma-assisted chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Nitrogen-doped CVD diamond materials can exhibit an increased fraction of positively charged substitutional nitrogen (

Crystal strain in CVD-grown diamond layers is strongly influenced by the dislocation density, and dislocations typically propagate along the growth direction (Martineau et al., 2004; Gaukroger et al., 2008). Key sources of dislocations include those nucleated at the substrate–growth interface due to substrate polishing damage, and dislocations threading from the substrate into newly grown layers. Additionally, mismatches in nitrogen concentration between the substrate and growth layers can induce bulk stress due to lattice mismatch (Friel et al., 2009). Thus, careful selection and preparation of substrates is critical.

The substrates are CVD single-crystal diamonds with low nitrogen content (

Following processing, electron irradiation and annealing is performed to convert grown-in

2.3 Wide-field strain mapping

Strain variations across each NV-diamond sample are mapped using CW-ODMR in a wide-field imaging configuration, as previously described in Ref. Roncaioli et al. (2024). Briefly, a 532 nm laser beam (

A bias magnetic field

2.4 Confocal spin and charge characterization

NV spin dephasing times

To achieve uniform optical NV excitation, the 532 nm laser beam is focused to a waist diameter of about 15

Microwave pulses for NV spin-state manipulation are delivered via a coaxial loop near the diamond surface, achieving Rabi frequencies

For NV charge-state determination, PL emission is collected through a multimode optical fiber coupled to a spectrometer. Recorded emission spectra are decomposed into

3 Results

3.1 Synthesized diamonds

We first study ten low-

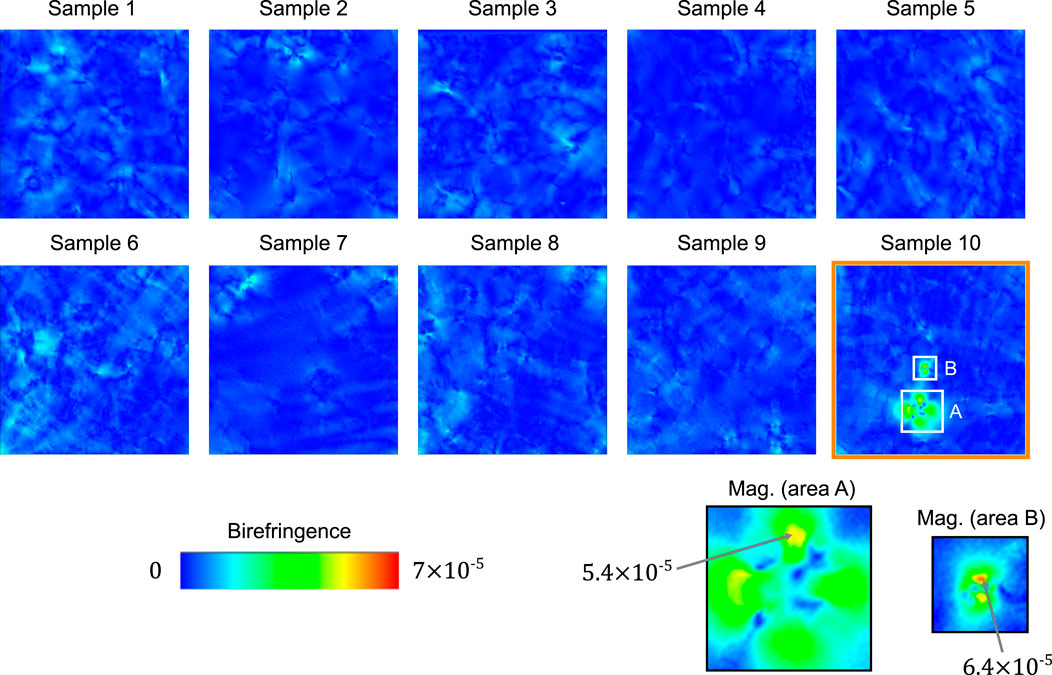

Figure 2. Optical birefringence images of ten low-

For subsequent characterizations (described below and in the Supplementary Material) we study sample 10, as this sample exhibits higher levels of birefringence from this growth process in certain spatially restricted regions, allowing us to examine both typical behavior for the low-

The main factors governing NV ensemble Ramsey dephasing time

3.2 NV spin dephasing time and strain contribution

Confocal Ramsey measurements of the single-quantum (SQ) NV ensemble spin dephasing time at three representative low-birefringence locations within sample 10 (Figures 3a,b) yield an average value

Figure 3. Single-quantum (SQ) Ramsey measurements on diamond sample 10, far from the high birefringence regions. (a) Ramsey measurements performed at three representative locations of low strain, overlaid on the birefringence image from Figure 2. (b) Ensemble NV spin dephasing at location 2. Here the microwave frequency is detuned from the center of the hyperfine-split NV spin transitions, allowing the decay envelope to be separated from hyperfine-induced beating. The extracted ensemble NV dephasing time is

Figure 4a shows the strain-induced frequency shifts

Figure 4. Wide-field imaging of diamond strain for sample 10. (a,b) Spatial maps of strain-induced frequency shifts in NV spin transitions across the entire diamond sample and within a selected sub-area. Strain fields shown are projections onto one NV crystallographic orientation. Each spatial map is mean-subtracted so that the global average is zero, emphasizing relative strain variations relevant to NV spin dephasing. (c,d) Histogram distributions of the strain-induced frequency shifts extracted from the maps in (a) and (b), respectively. Lorentzian fits to the histograms are also shown, from which linewidths (FWHM)

To evaluate the feasibility of scaling sensor sizes for bulk NV magnetometry, we analyze how strain-induced linewidth broadening changes with sensing region size

Figure 5. (a) Lorentzian-fitted FWHM

To illustrate how size-dependent strain-induced dephasing affects NV ensemble sensor performance, we compute an effective Ramsey DC magnetometry sensitivity metric

3.3 Photoluminescence contrast, overhead time, and charge fraction

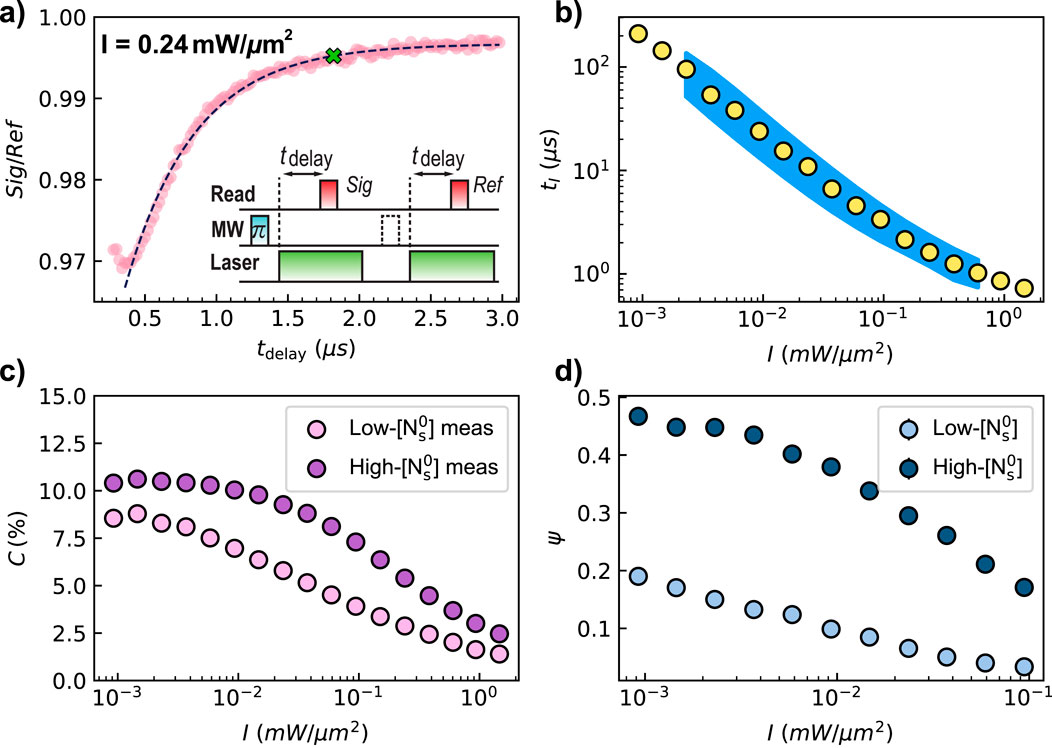

We characterize NV photoluminescence (PL) spin-state contrast

Figure 6. NV spin polarization dynamics, initialization time, PL contrast, and charge fraction as functions of laser excitation intensity. (a) Measured NV spin polarization dynamics and schematic measurement protocol (inset). A 1-ms laser pulse (not shown) initializes the NV ensemble into the

Observed PL contrast degradation at higher optical intensities (Figure 6c) is primarily attributed to increased

4 Discussion

The availability of low-

Figure 7 summarizes volume-normalized DC sensitivity estimates for both diamond types, effectively replacing the

Figure 7. Estimated volume-normalized photon shot-noise limited DC magnetic field sensitivity for low- and high-

Double-quantum (DQ) Ramsey protocols applied to NV ensembles typically provide DC magnetic field sensitivity enhancement via a doubled effective gyromagnetic ratio (

We note that diamond sample 10 examined in this study (Figure 2) exhibited the highest level of birefringence among the ten low-

Our comprehensive assessment of NV PL contrast, charge fraction, spin dephasing time, and photon-shot-noise-limited sensitivity provides guidance to the community in selecting suitable NV-diamond materials for specific sensing applications and operational regimes. In particular, since the low-

5 Conclusion

We synthesized and systematically characterized low-

These findings provide practical benchmarks and guidance for selecting NV-diamond sensors based on available optical power and application-specific requirements. Specifically, low-

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JT: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. CR: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AE: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AD: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. CH: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing – review and editing. MM: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review and editing. RW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by, or in part by, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, under Contract No. W911NF2420143; the U.S. Army Research Office, under Grant No. W911NF2120110; and the University of Maryland Quantum Technology Center.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Ang and Smriti Bhalerao for their help in setting up a birefringence microscope; and Mason Camp for initial characterization measurements on a second low-nitrogen diamond used in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT, OpenAI) was used only for language editing and polishing of the manuscript. All scientific content, data, analysis, and figures were generated and verified by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frqst.2025.1701548/full#supplementary-material

References

Alsid, S. T., Barry, J. F., Pham, L. M., Schloss, J. M., O’Keeffe, M. F., Cappellaro, P., et al. (2019). Photoluminescence decomposition analysis: a technique to characterize N-v creation in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044003. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.12.044003

Arunkumar, N., Olsson, K. S., Oon, J. T., Hart, C. A., Bucher, D. B., Glenn, D. R., et al. (2023). Quantum logic enhanced sensing in solid-state spin ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 100801. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.100801

Aslam, N., Waldherr, G., Neumann, P., Jelezko, F., and Wrachtrup, J. (2013). Photo-induced ionization dynamics of the nitrogen vacancy defect in diamond investigated by single-shot charge state detection. New J. Phys. 15, 013064. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/15/1/013064

Aslam, N., Zhou, H., Urbach, E. K., Turner, M. J., Walsworth, R. L., Lukin, M. D., et al. (2023). Quantum sensors for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 157–169. doi:10.1038/s42254-023-00558-3

Aude Craik, D., Kehayias, P., Greenspon, A., Zhang, X., Turner, M., Schloss, J., et al. (2020). Microwave-assisted spectroscopy technique for studying charge state in nitrogen-vacancy ensembles in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 014009. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.14.014009

Barry, J. F., Turner, M. J., Schloss, J. M., Glenn, D. R., Song, Y., Lukin, M. D., et al. (2016). Optical magnetic detection of single-neuron action potentials using quantum defects in diamond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14133–14138. doi:10.1073/pnas.1601513113

Barry, J. F., Schloss, J. M., Bauch, E., Turner, M. J., Hart, C. A., Pham, L. M., et al. (2020). Sensitivity optimization for NV-diamond magnetometry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 015004. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.92.015004

Barry, J. F., Steinecker, M. H., Alsid, S. T., Majumder, J., Pham, L. M., O’Keeffe, M. F., et al. (2024). Sensitive ac and dc magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy-center ensembles in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 044069. doi:10.1103/physrevapplied.22.044069

Bauch, E., Hart, C. A., Schloss, J. M., Turner, M. J., Barry, J. F., Kehayias, P., et al. (2018). Ultralong dephasing times in solid-state spin ensembles via quantum control. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031025. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.8.031025

Edmonds, A. M., Hart, C. A., Turner, M. J., Colard, P.-O., Schloss, J. M., Olsson, K. S., et al. (2021). Characterisation of CVD diamond with high concentrations of nitrogen for magnetic-field sensing applications. Mater. Quantum Technol. 1, 025001. doi:10.1088/2633-4356/abd88a

Eisenach, E., Barry, J., Pham, L., Rojas, R., Englund, D. R., and Braje, D. (2018). Broadband loop gap resonator for nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 89, 094705. doi:10.1063/1.5037465

Friel, I., Clewes, S., Dhillon, H., Perkins, N., Twitchen, D., and Scarsbrook, G. (2009). Control of surface and bulk crystalline quality in single crystal diamond grown by chemical vapour deposition. Diam. Relat. Mater. 18, 808–815. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2009.01.013

Fu, R. R., Maher, B. A., Nie, J., Gao, P., Berndt, T., Folsom, E., et al. (2023). Pinpointing the mechanism of magnetic enhancement in modern soils using high-resolution magnetic field imaging. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 24, e2022GC010812. doi:10.1029/2022GC010812

Fujita, N., Jones, R., Öberg, S., and Briddon, P. (2009). Large spherical vacancy clusters in diamond – origin of the brown colouration? Diam. Relat. Mater. 18, 843–845. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2008.10.061

Garsi, M., Stöhr, R., Denisenko, A., Shagieva, F., Trautmann, N., Vogl, U., et al. (2024). Three-dimensional imaging of integrated-circuit activity using quantum defects in diamond. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 014055. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.21.014055

Gaukroger, M., Martineau, P., Crowder, M., Friel, I., Williams, S., and Twitchen, D. (2008). X-ray topography studies of dislocations in single crystal cvd diamond. Diam. Relat. Mater. 17, 262–269. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2007.12.036

Glazer, A., Lewis, J., and Kaminsky, W. (1996). An automatic optical imaging system for birefringent media. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 452, 2751–2765. doi:10.1098/rspa.1996.0145

Glenn, D. R., Fu, R. R., Kehayias, P., Le Sage, D., Lima, E. A., Weiss, B. P., et al. (2017). Micrometer-scale magnetic imaging of geological samples using a quantum diamond microscope. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18, 3254–3267. doi:10.1002/2017GC006946

Glover, C., Newton, M. E., Martineau, P., Twitchen, D. J., and Baker, J. M. (2003). Hydrogen incorporation in diamond: the nitrogen-vacancy-hydrogen complex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 185507. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.185507

Glover, C., Newton, M. E., Martineau, P. M., Quinn, S., and Twitchen, D. J. (2004). Hydrogen incorporation in diamond: the vacancy-hydrogen complex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 135502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.135502

Graziosi, T., Rathmill, A., Patel, R. L., Palmer, N., Edmonds, A. M., Markham, M. L., et al. (2023). Control of strain in thin diamond nitrogen-vacancy layers for magnetometry applications. Quantum sensing, imaging, and precision metrology. Editors J. Scheuer, and S. M. Shahriar (Bellingham, WA United States: International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE)), 12447. doi:10.1117/12.2649676

Hart, C. A., Schloss, J. M., Turner, M. J., Scheidegger, P. J., Bauch, E., and Walsworth, R. L. (2021). N-V–diamond magnetic microscopy using a double quantum 4-ramsey protocol. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 044020. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.044020

Hartland, C. B. (2014). A study of point defects in CVD diamond using electron paramagnetic resonance and optical spectroscopy. Ph.D. thesis, Coventry, United Kingdom: University of Warwick.

Hird, J. R., and Field, J. E. (2004). Diamond polishing. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 460, 3547–3568. doi:10.1098/rspa.2004.1339

Hounsome, L. S., Jones, R., Martineau, P. M., Fisher, D., Shaw, M. J., Briddon, P. R., et al. (2006). Origin of brown coloration in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 73, 125203–125208. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.125203

Kehayias, P., Turner, M. J., Trubko, R., Schloss, J. M., Hart, C. A., Wesson, M., et al. (2019). Imaging crystal stress in diamond using ensembles of nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. B 100, 174103. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.100.174103

Khan, R. U. A., Martineau, P. M., Cann, B. L., Newton, M. E., and Twitchen, D. J. (2009). Charge transfer effects, thermo- and photochromism in single crystal cvd synthetic diamond. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 364214. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/21/36/364214

Khan, R., Martineau, P., Cann, B., Newton, M., Dhillon, H., and Twitchen, D. (2010). Color alterations in cvd synthetic diamond with heat and uv exposure: implications for color grading and identification. Gems & Gemology 46, 18–26. doi:10.5741/gems.46.1.18

Ku, M. J., Zhou, T. X., Li, Q., Shin, Y. J., Shi, J. K., Burch, C., et al. (2020). Imaging viscous flow of the dirac fluid in graphene. Nature 583, 537–541. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2507-2

Laissue, P. P., Alghamdi, R. A., Tomancak, P., Reynaud, E. G., and Shroff, H. (2017). Assessing phototoxicity in live fluorescence imaging. Nat. Methods 14, 657–661. doi:10.1038/nmeth.4344

Mamin, H., Sherwood, M., Kim, M., Rettner, C., Ohno, K., Awschalom, D., et al. (2014). Multipulse double-quantum magnetometry with near-surface nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 030803. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.030803

Manson, N., and Harrison, J. (2005). Photo-ionization of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Diam. Related Materials 14, 1705–1710. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2005.06.027

Martineau, P. M., Lawson, S. C., Taylor, A. J., Quinn, S. J., Evans, D. J. F., and Crowder, M. J. (2004). Identification of synthetic diamond grown using chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Gems. Gemmol. 40, 2–25. doi:10.5741/gems.40.1.2

Przybylski, A., Thiel, B., Keller-Findeisen, J., Stock, B., and Bates, M. (2017). Gpufit: an open-source toolkit for gpu-accelerated curve fitting. Sci. Reports 7, 15722. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15313-9

Roncaioli, C., Hart, C. A., Walsworth, R., and Fahey, D. P. (2024). All-in-one quantum diamond microscope for sensor characterization. AVS Quantum Sci. 6, 044403. doi:10.1116/5.0222809

Rovny, J., Gopalakrishnan, S., Jayich, A. C. B., Maletinsky, P., Demler, E., and de Leon, N. P. (2024). Nanoscale diamond quantum sensors for many-body physics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 753–768. doi:10.1038/s42254-024-00775-4

Schirhagl, R., Chang, K., Loretz, M., and Degen, C. L. (2014). Nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: nanoscale sensors for physics and biology. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 65, 83–105. doi:10.1146/annurev-physchem-040513-103659

Schloss, J. M. (2019). Optimizing nitrogen-vacancy diamond magnetic sensors and imagers for broadband sensitivity. Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge, MA United States: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Schuelke, T., and Grotjohn, T. A. (2013). Diamond polishing. Diam. Relat. Mater. 32, 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2012.11.007

Turner, M. J., Langellier, N., Bainbridge, R., Walters, D., Meesala, S., Babinec, T. M., et al. (2020). Magnetic field fingerprinting of integrated-circuit activity with a quantum diamond microscope. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 014097. doi:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.14.014097

Keywords: quantum sensing, nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers, magnetic sensing, precision measurement, chemical vapor deposition (CVD)

Citation: Tang J, Roncaioli CA, Edmonds AM, Davidsson A, Hart CA, Markham ML and Walsworth RL (2025) Characterization of low-nitrogen quantum diamond for pulsed magnetometry applications. Front. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4:1701548. doi: 10.3389/frqst.2025.1701548

Received: 08 September 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Jean-Philippe Tetienne, RMIT University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Lillian B. Hughes, University of California-Santa Barbara, United StatesMichal Kern, University of Stuttgart, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Tang, Roncaioli, Edmonds, Davidsson, Hart, Markham and Walsworth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ronald L. Walsworth, d2Fsc3dvcnRoQHVtZC5lZHU=

Jiashen Tang

Jiashen Tang Connor A. Roncaioli

Connor A. Roncaioli Andrew M. Edmonds4

Andrew M. Edmonds4 Ronald L. Walsworth

Ronald L. Walsworth