Abstract

Background:

Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), also known as long COVID, are characterized by persistent symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, and reduced functional capacity. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is recommended for chronic respiratory conditions, but its effectiveness in PASC, particularly across different delivery modes, remains uncertain.

Objective:

To assess the impact of PR, including telerehabilitation and in-person modalities, on physical function, dyspnea, pulmonary function, fatigue, and quality of life in patients with PASC.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science from inception to March 25 for controlled clinical trials assessing the effects of PR in PASC patients. Two independent reviewers performed study selection and data extraction. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, and data were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.4.1. Effect sizes were reported as mean differences (MD) or standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results:

Ten randomized controlled trials involving 673 participants were included. Most studies were judged to have a moderate risk of bias. Compared with usual care, PR significantly improved six-minute walk distance (MD: 76.85 meters; 95% CI: 57.35–96.36; p < 0.001), maximal inspiratory pressure (MD: 17.63 cmH₂O; 95% CI: 4.50–30.76; p = 0.009), fatigue (SMD: −1.15; 95% CI: −1.83 to −0.48; p < 0.001), and quality of life (SMD: 1.73; 95% CI: 0.56–2.91; p = 0.004). No statistically significant improvement was found for dyspnea (MD: −0.41; 95% CI: −1.51 to −0.68; p = 0.46). Subgroup analyses showed no significant differences between telerehabilitation and in-person PR across all outcomes, including exercise capacity (p = 0.84), dyspnea (p = 0.86), fatigue (p = 0.93), and quality of life (p = 0.44).

Conclusions:

PR improves physical and functional outcomes in patients with PASC. Telerehabilitation offers a clinically equivalent alternative to in-person PR, supporting its broader implementation.

1 Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected over 510 million individuals and caused more than 6.2 million deaths globally (1). A significant proportion of those infected develop persistent symptoms beyond 12 weeks, known as Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC). These symptoms may appear as early as the fourth week post-infection and are not fully explained by alternative diagnoses such as cardiovascular, respiratory, or neurological disorders (2). The estimated global prevalence of PASC is around 43%, suggesting that more than 300 million people may be affected worldwide (3).

PASC is a heterogeneous condition characterized by more than 200 reported symptoms. Patients with symptoms persisting beyond six months frequently report a median of 14 concurrent symptoms (4), with fatigue and dyspnea being the most prevalent and debilitating. These symptoms often co-occur with anxiety, depression, and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL), lasting for months or even years (5–7). The complex and overlapping nature of PASC manifestations contributes substantially to the long-term burden on healthcare systems, accounting for up to 30% of COVID-19-related healthcare utilization (3). Without targeted intervention, spontaneous recovery is uncommon, and many patients experience long-term functional impairment and disability (4).

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), an evidence-based intervention combining supervised exercise training, education, and psychological support, has been widely recommended to address the multifaceted needs of patients with chronic respiratory diseases. In the context of PASC, PR has demonstrated potential in improving exercise tolerance, pulmonary function, fatigue, mood symptoms, and overall quality of life (8–10). Studies in both chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and COVID-19 populations support the efficacy of PR in restoring physical function and reducing psychological burden (11, 12).

Functional limitations are common among PASC patients. One study found that nearly 70% of COVID-19 survivors had six-minute walk distances (6MWD) below predicted values one year after discharge (13), while others reported a 33% reduction in 6MWD compared to healthy controls during 2–6 months of follow-up (14, 15). Moreover, up to 56% of patients with severe initial infection show impaired lung diffusing capacity lasting up to a year. These physical impairments are often accompanied by psychological distress, such as anxiety and depression, in approximately 23% of patients (6, 7), significantly reducing their HRQoL. In response to pandemic-related restrictions and resource constraints, telerehabilitation, the remote delivery of PR via digital platforms, has emerged as a practical alternative to traditional face-to-face programs (16). Preliminary evidence suggests that telerehabilitation may achieve similar outcomes in improving exercise capacity, symptom burden, and quality of life in PASC patients, with additional benefits in accessibility and safety (17, 18). However, the current body of evidence remains limited, heterogeneous, and inconclusive regarding the relative effectiveness of telerehabilitation versus in-person PR.

Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in improving physical and psychological outcomes in patients with PASC and to compare the clinical benefits of telerehabilitation and in-person PR delivery models.

2 Methods

The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis Protocols checklist (19), the detailed was in Supplementary Table S2. The review was not registered.

2.1 Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic literature search was conducted in four major electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The search covered studies published from database inception through March 2025. To ensure both sensitivity and specificity, the search strategy incorporated a combination of controlled vocabulary [Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for PubMed and Emtree terms for Embase] and free-text keywords. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to combine terms across three core conceptual domains: the target condition [Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (PASC)], the intervention [pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) and its variants], and the study design (randomized controlled trials).

Terms representing the disease condition included “post COVID-19 syndrome,” “long COVID,” “post-acute COVID-19 syndrome,” “chronic COVID syndrome,” “post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection,” “long haul COVID,” “post COVID-19 condition,” “persistent COVID symptoms,” and “PASC.” Terms related to the intervention included “pulmonary rehabilitation,” “respiratory rehabilitation,” “breathing training,” “respiratory muscle training,” “inspiratory muscle training,” “expiratory muscle training,” “breathing exercise,” “airway clearance technique,” “respiratory therapy,” “physical therapy modalities,” and “exercise therapy.” Terms used to define eligible study designs included “randomized controlled trial,” “randomised controlled trial,” “randomized trial,” “clinical trial,” and “RCT.”

No restrictions were placed on language or publication status. The detailed search strategy was in Supplementary Table S1. To supplement the electronic database search, the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews were screened manually to identify additional eligible articles not captured by the database queries.

2.2 Study selection and eligibility criteria

All retrieved records were imported into EndNote X9 reference management software for deduplication. After the removal of duplicates, two independent reviewers conducted a two-stage screening process. First, titles and abstracts of all identified articles were screened to exclude irrelevant publications. Next, full-text versions of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and reviewed in detail according to pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion, and if consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted to adjudicate.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria. The population of interest comprised adult participants (aged 18 years or older) diagnosed with PASC, long COVID, or a similar condition defined as persistent symptoms following laboratory-confirmed or clinically suspected COVID-19 infection. The intervention had to be a structured PR or breathing exercises (exercises to strengthen respiratory muscles, breathing control exercises, airway clearance techniques, or thoracic expansion, etc.), multicomponent exercises (integrated of aerobic, strength, resistance, or endurance exercises, etc.), and Comprehensive PR (both breathing exercises and multicomponent exercises).Both in-person(face-to-face) and telerehabilitation formats were considered eligible. The comparator could be usual care, a sham intervention, or no intervention. Eligible studies had to report at least one quantitative outcome, such as physical function [e.g., six-minute walk distance (6MWD)], dyspnea, pulmonary function parameters [e.g., maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP)], fatigue, or health-related quality of life. Only studies employing an RCT design were included.

Studies were excluded if they were non-randomized designs, included pediatric populations, lacked a comparator group, did not include PR as the primary intervention, or did not provide extractable data for meta-analysis. Conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries, and narrative reviews were also excluded.

2.3 Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Two independent reviewers extracted data using a standardized form. Extracted variables included first author, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, participant demographics, timing of PR initiation, intervention duration and modality, comparator type, outcome measures, and results. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool version 2.0 (RoB 2), which evaluates bias across domains including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. Each domain was rated as “low,” “some concerns,” or “high.” Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

2.4 Outcome measures and statistical analysis

The primary outcome was exercise capacity, assessed by the 6MWD. Secondary outcomes included dyspnea measured using the mMRC scale, fatigue assessed through standardized fatigue-related scales, health-related quality of life evaluated via instruments such as EQ-5D or SF-36, and pulmonary function measured by MIP. Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.4. Continuous outcomes were pooled using either mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Values of I2 greater than 50% were considered indicative of substantial heterogeneity, in which case a random-effects model was used. Pre-specified subgroup analyses were performed to compare the effects of telerehabilitation and face-to-face PR. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Include studies

The literature search initially retrieved 1,766 records. After removing 899 duplicates, 867 unique records remained. Title and abstract screening led to the exclusion of 844 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. A total of 55 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 45 were excluded due to reasons such as non-randomized study design, ineligible population, lack of pulmonary rehabilitation as a primary intervention, or insufficient outcome data. Finally, 10 randomized controlled trials evaluating the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation in individuals with PASC met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Literature screening flowchart.

3.2 Summary of main results

Tables 1–3 includes descriptive information for the 10 studies included in the systematic review. The studies were performed in China (1), Iran (1), Spain (2), and Egypt (2). UK (1), Turkey (2), and the United States of America (1). All studies were published from 2021 to 2025. Including a total of 673 participants, the ages of the included participants ranged between 23 and 55 years. The participants studied for an average duration of 3 months after COVID-19. The primary symptoms reported by the studies were dyspnea, fatigue, 6MWD, and quality of life. Each study used a different protocol for PR. Face-to-face PR was conducted in a hospital or clinic in 3 RCTs (20, 22, 27) and telerehabilitation PR (e.g., via telerehabilitation tools, videoconference, or phone call) was conducted in 7 RCTs (17, 21, 23–26, 28). Telerehabilitation models were unsupervised home-based (17, 24) or tele-supervised home-based models (21, 23, 25, 26, 28). In total, 5 RCTs (17, 21, 25, 26, 28) included patients previously hospitalized due to COVID-19 infection. One RCT (27) included patients who had not been hospitalized following COVID-19 infection. 4 RCTs (20, 22–24) included a mixed population of both patients. 7 studies (17, 20, 22, 24–26, 28) showed that the included subjects had dyspnea. Among them, six studies (17, 20, 22, 25, 26, 28) used the MMRC scale for grading, and most of the included subjects had a dyspnea degree of grade II∼III. One study (24) adopted the K-BILD questionnaire for assessment, but did not specifically describe the degree of dyspnea in the patients.

Table 1

| Study | Group | Age | Sex | BMI | Smoker | Former smoker | Days in hospital | Clinical course | Dyspnea | Cough | Fever | Fatigue | Brain fog | Myalgia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M/F) | (n,%) | (n,%) | Mild (n,%) | Moderate (n,%) | Severe (n,%) | (n,%) | (n,%) | (n,%) | (n,%) | (n,%) | (n,%) | |||||

| del Corral et al. (20) | Intervention | 49.0 ± 10.4 | 12/20 | 28.08 (6.3) | 10 (31) | 4 (12) | - | 11 (34) | 15 (47) | 6 (19) | 32 (100) | 32 (100) | 20 (62) | 22 (69) | ||

| Control | 51.4 ± 10.6 | 11/21 | 28.7 (5.2) | 11 (34) | 6 (19) | - | 8 (25) | 15 (47) | 9 (28) | 32 (100) | 32 (100) | 31 (66) | 19 (59) | |||

| Deldar et al. (21) | Intervention | 54.5 ± 12.0 | - | 28.1 (5.2) | 4 (13.3) | 6.6 (2.8) | ||||||||||

| Control | 50.4 ± 12.3 | - | 27.6 (3.8) | 1 (3.3) | 6.5 (2.9) | |||||||||||

| Elyazed et al. (22) | Intervention | 49.17 ± 10.75 | 27/32 | 30.1 (0.83) | 30 (100) | |||||||||||

| Control | 52.03 ± 11.10 | 26/34 | 29.1 (4.4) | 30 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Alsharidah et al. (23) | Intervention | 23.33 ± 2.71 | 0/24 | 22.11 (2.66) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 22.58 ± 2.51 | 0/24 | 21.65 (2.73) | |||||||||||||

| McNarry et al. (24) | Intervention | 46.76 ± 12.03 | 2/35 | 27.64 (6.80) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 46.13 ± 12.73 | 16/95 | 27.81 (5.83) | |||||||||||||

| Pehlivan et al. (25) | Intervention | 52.77 ± 13.91 | 14/3 | 27.98 (21–36) | 7 (41) | 10 (59) | 12 (71) | 6 (35) | ||||||||

| Control | 44.45 ± 13.36 | 11/6 | 27.43 (19–36) | 4 (24) | 11 (65) | 7 (41) | 5 (29) | |||||||||

| Okan et al. (26) | Intervention | 48.85 ± 10.85 | 15/11 | 31.14 (4.18) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (15.4) | 9 (0–15) | |||||||||

| Control | 52.19 ± 14.84 | 12/14 | 31.31 (4.36) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (7.7) | 9.5 (5–13.75) | ||||||||||

| Almazán et al. (27) | Intervention | 44.6 ± 9.9. | 13/6 | 19 (100) | 11 (57.9) | 3 (15.8) | 4 (21.1) | 16 (84.2) | 11 (61.1) | 8 (42.1) | ||||||

| Control | 46.0 ± 9.5 | 16/4 | 20 (100) | 12 (60.0) | 3 (15.0) | 3 (15.0) | 16 (80.0) | 10 (50.0) | 10 (50.0) | |||||||

| Capin et al. (28) | Intervention | 52 ± 10 | 13/15 | 34 (9) | 5 (3) | 7 (25) | ||||||||||

| Control | 54 ± 10 | 5/8 | 36 (11) | 8 (9) | 2 (15) | |||||||||||

| Li et al. (17) | Intervention | 49.17 ± 10.75 | 27/32 | 9 (15.3) | ||||||||||||

| Control | 52.03 ± 11.1 | 26/34 | 6 (10.0) | |||||||||||||

Demographic details of the included studies.

Table 2

| Study | Participants | Intervention type | Timing of PR initiation | Supervision | Dyspnea severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| del Corral et al. (20) | Had been diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and presented with long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms, including fatigue and dyspnea | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | >3 months post-infection | Supervised | Dyspnea was inclusion criteria. Severity not numerically specified. |

| Deldar et al. (21) | With a definite diagnosis of COVID-19 and a positive COVID test showing lung lesions (confirmed by radiographic report or CT scan by an infectious disease specialist), were included. | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | 1–3 months post-infection | Remote Supervised | – |

| Elyazed et al. (22) | Diagnosed and confirmed via COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test within the last three months, either hospitalized or receiving home treatment but not needing ICU admission; discharged at least one month of acute phase recovery with post COVID-19 fatigue, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | 1–3 months post-infection | Supervised | Assessment of dyspnea by mMRC |

| Alsharidah et al. (23) | Diagnosis of COVID-19;included mild to moderate post-COVID-19 survivors, COVID-19 severity was classified into three categories mild to moderate (outpatients with a flu-like condition or probable pneumonia), severe (hospitalized patients treated in hospital wards), and critical (patients treated in an intensive care unit) | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | >3 months post-infection | Supervised | – |

| McNarry et al. (24) | 9.0 ± 4.2 months post-acute COVID-19 self-reported COVID-19 infection | Inspiratory Muscle Training (IMT) | <1 month post-infection | Unsupervised | (K-BILD) questionnaire Severity not numerically specified. |

| Pehlivan et al. (25) | Diagnosed with COVID-19 and discharged after treatment, still in the first 4 weeks after discharging, described by regression in physical functions after discharge compared to preillness, | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | 1–3 months post-infection | Remote Supervised | Assessment of dyspnea by mMRC ranged from 0 to 2 |

| Okan et al. (26) | Received treatment for Covid-19, completed 2months after treatment and presented to the Chest Diseases Outpatient Clinic with dyspnea. | Breathing exercises only | Unspecified | Remote Supervised | Assessment of dyspnea by mMRC ranged from 0 to 4 |

| Almazán et al. (27) | Confirmed microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 by SARS-CoV2 reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction on an oropharyngeal–nasopharyngeal swab or a positive rapid antigen test, who presented a chronic symptomatic phase, lasting >12weeks from the onset of symptoms, and had not been hospitalized because of the acute COVID-19 infection. | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | 1–3 months post-infection | Supervised | – |

| Capin et al. (28) | Confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection defined by positive PCR testing, completed a hospitalisation that was at least 24 h | App-based multimodal programs | 1–3 months post-infection | Supervised | Not quantitatively reported MRC dyspnea Score |

| Li et al. (17) | Discharged from one of the participating hospitals after inpatient treatment for COVID-19 | Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) | <1 month post-infection | Unsupervised | mMRC dyspnea score of 2–3. (exact score range not reported) |

PR details of the included studies.

Table 3

| Study characteristics | Intervention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Year | Sample | Site | Delivery mode | Frequency | Weeks | Experimental group | Control group | Outcomes |

| del Corral et al. (20) | 2025 | 64 (32/32) | Hospital | In-person | 3 times/w | 8w | Respiratory muscle training two 20-min sub-sessions,; Aerobic exercise (5-min warm-up, 28-min interval AE training on bicycle ergometer, 8-min cool-down and 10-min stretching exercise) | AE | ④⑤ |

| Deldar et al. (21) | 2024 | 60 (30/30) | Home | Telerehabilitation | 4 times/w | 4w | Telerehabilitation PR (Respiratory rehabilitation exercises 30-minute session per day) | A training booklet an incentive spirometer |

①③④⑤ |

| Elyazed et al. (22) | 2024 | 68 (34/34) | Hospital | In-person | 5times/w | 12w | PR (Respiratory muscle training: 10–15 min, twice per day, daily for 3 months + Resisted training: 3 sets of 10 repetitions, twice a day, 5–7 days a week + Regular walking for 30–60 min, 5 days a week, at a normal pace for 3 months) | No exercise | ①③④② |

| Alsharidah et al. (23) | 2023 | 48 (24/24) | Home | Telerehabilitation | 3 times/w | 6w | Telerehabilitation PR (breathing exercises and chest expansion, including diaphragmatic breathing exercise, chest mobility for 15 min, Aerobic activity for 20 to 30 min; resistance training for 30 min.) | Written instructions | ① |

| McNarry et al. (24) | 2022 | 148 (111/37) | Home | Telerehabilitation | 3 times/w 2 sessions/d |

8w | Telerehabilitation (Breathing exercises at 80% of maximal inspiratory pressure with an inspiratory flow device.) | Waitlist. | ④⑤ |

| Pehlivan et al. (25) | 2022 | 34 (17/17) | Home | Telerehabilitation | 3 times/w | 6w | Telerehabilitation PR (patient education, paced running/self-walking on the corridor, breathing exercises, active cycle of breathing technique, range of motion exercise, and standing squat) | Exercise training, similar exercise as the TeleGr by smartphone | ②③④ |

| Okan et al. (26) | 2022 | 52 (26/26) | Home | Telerehabilitation | _ | 5w | Telerehabilitation Breathing Exercises (Respiratory control, pursed lip breathing, and diaphragmatic breathing exercises) + aerobic exercise (mild-intensity walking) | Usual care | ①② |

| Almazán et al. (27) | 2022 | 39 (19/20) | Medical center | In-person | 3 times/w | 8w | The resistance training, intensity, and intra-set volume were kept constant throughout the training, and a weekly linear volume was varied. | Support for Rehabilitation | ②③ |

| Capin et al. (28) | 2022 | 41 (28/13) | Home | Telerehabilitation | _ | 6w | Telerehabilitation PR (breathing and clearance techniques, high-intensity strength training,16 aerobic and cardiovascular exercise, balance exercises, functional activities, stretching) | Educational handout, safety monitoring, physical activity, | ② |

| Li et al. (17) | 2021 | 119 (59/60) | Home | Telerehabilitation | 3∼4 times/w | 6w | Telerehabilitation PR: Breathing and thoracic expansion, aerobic exercise and LMS exercises (Aerobic exercise was based on HR reserve determined by Karvonen's formula.) | Short educational instructions at baseline. | ① |

PR details of the included studies.

① six-minute walk test (6-MWT); ② Dyspnea (mMRC,); ③ Fatigue (fatigue related scale); ④ Qualify of life (qualify of life related scale); ⑤ MIP.

The interventions and controls were shown in Table 1. The duration of PR ranged from 4 weeks to 12 weeks, 1 RCT (21) had a duration ⩽4 weeks, 8 RCTs (17, 20, 23–28) had a duration with 4–8 weeks, 1 RCT (22) had a duration of >8 weeks. The timing of PR initiation in 2 RCTs (20, 23) was 3 months after infection,5 RCTs (21, 22, 25, 27, 28) was 1–3 months post-infection,2 RCTs (17, 24) was <1 month post-infection, In addition, 1 RCT (26) was not described. Breathing exercises were performed in 1 RCT (26), Inspiratory Muscle Training were performed in 1 RCT (24), Comprehensive PR (aerobic + resistance + breathing) were performed in 7 RCTs (17, 20–23, 25, 27) and App-based multimodal programs were performed in 1 RCT (28). PR programs varied in the number of sessions and intervention approaches employed. The control group received usual care, no treatment, was given an educational brochure explaining breathing exercises and self-management guidelines, or used a sham device.

3.3 Risk of bias in included studies

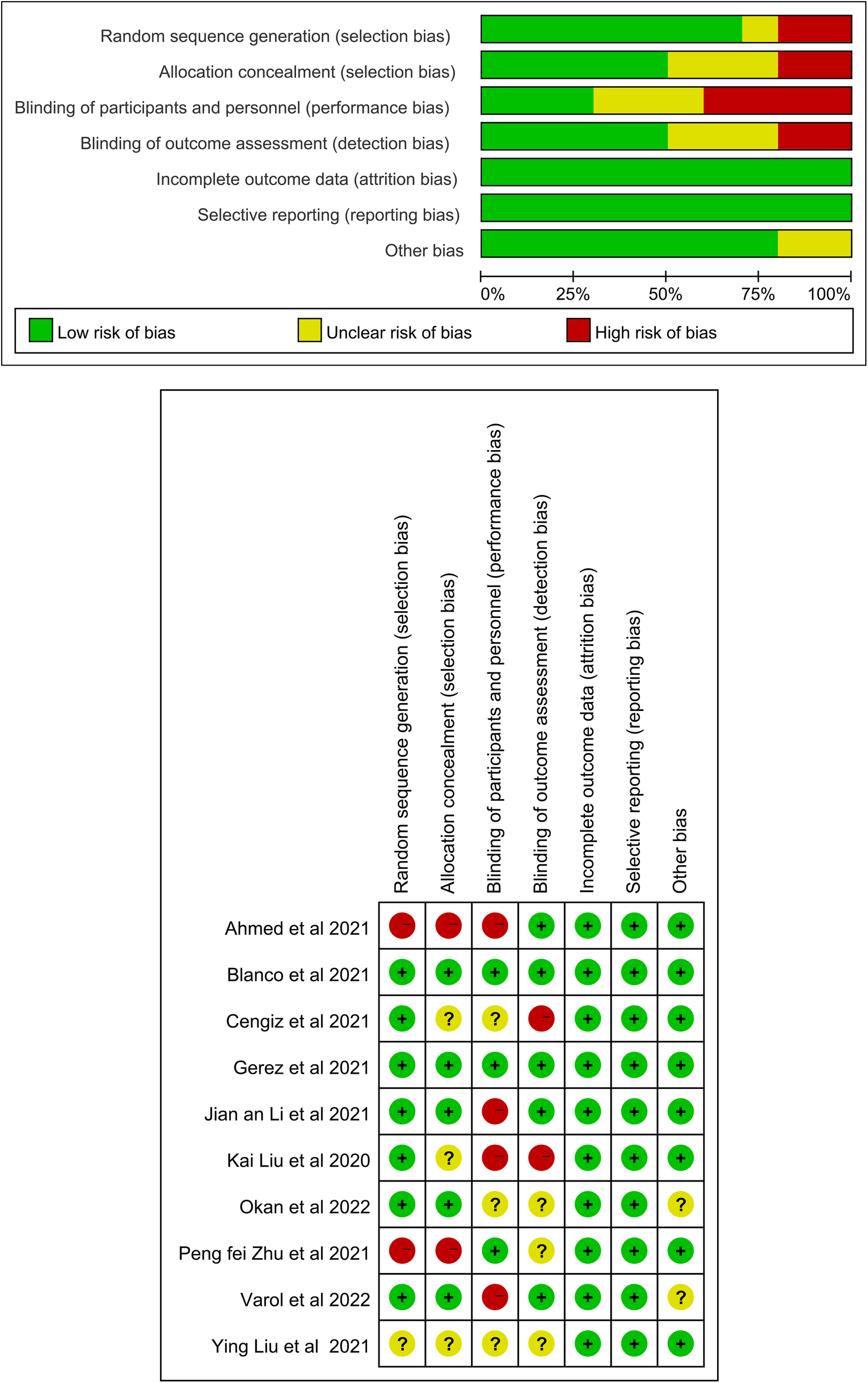

The quality evaluation results of the RCTs are showed, 6 RCTs (17, 22, 24–26, 28) showed a high risk of bias, 2 (23, 27) showed some concern, and 2 (20, 21) had a low risk of bias. Among the included RCTs, 3 RCTs (20, 21, 23) were performed with double blinding, and the others were performed with single blinding, no blinding, or had an unclear design.

The risk of bias across studies was generally moderate. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and personnel was not feasible in most trials, potentially introducing performance bias. In addition, blinding of outcome assessment was inconsistently reported, which may have contributed to detection bias. Overall, methodological limitations were noted primarily in the domains of blinding. Blinding participants and therapists is inherently a challenge in rehabilitation research. The detailed risk of bias assessments are shown in Figures 2.

Figure 2

Risk of bias assessment for the randomized trials included in the meta-analysis. (A) Risk of bias summary; (B) Risk of bias graph. Symbols. (+): low risk of bias; (?): unclear risk of bias; (–): high risk of bias.

3.4 Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation compared with usual care

Five studies assessed exercise capacity using the 6MWD. Meta-analysis showed that PR significantly improved 6MWD distance compared to usual care, with a mean difference of 76.85 meters (95% CI: 57.35–96.36, p < 0.001). Heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 68%). The observed effect exceeded the minimal important difference of 30 meters, suggesting both statistical and clinical relevance (29, 30) shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation vs. control on exercise capacity (measured by 6-MWT).

Dyspnea was evaluated using the mMRC scale in four studies. The pooled mean difference favored PR but was not statistically significant (MD: −0.41, 95% CI: −1.51 to 0.68, p = 0.46). Heterogeneity was considerable (I2 = 96%). One additional study reported a statistically significant within-group improvement in dyspnea (p < 0.008) but could not be included in the meta-analysis due to untransformable data (22) shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation vs. control on dyspnea (measured by mMRC).

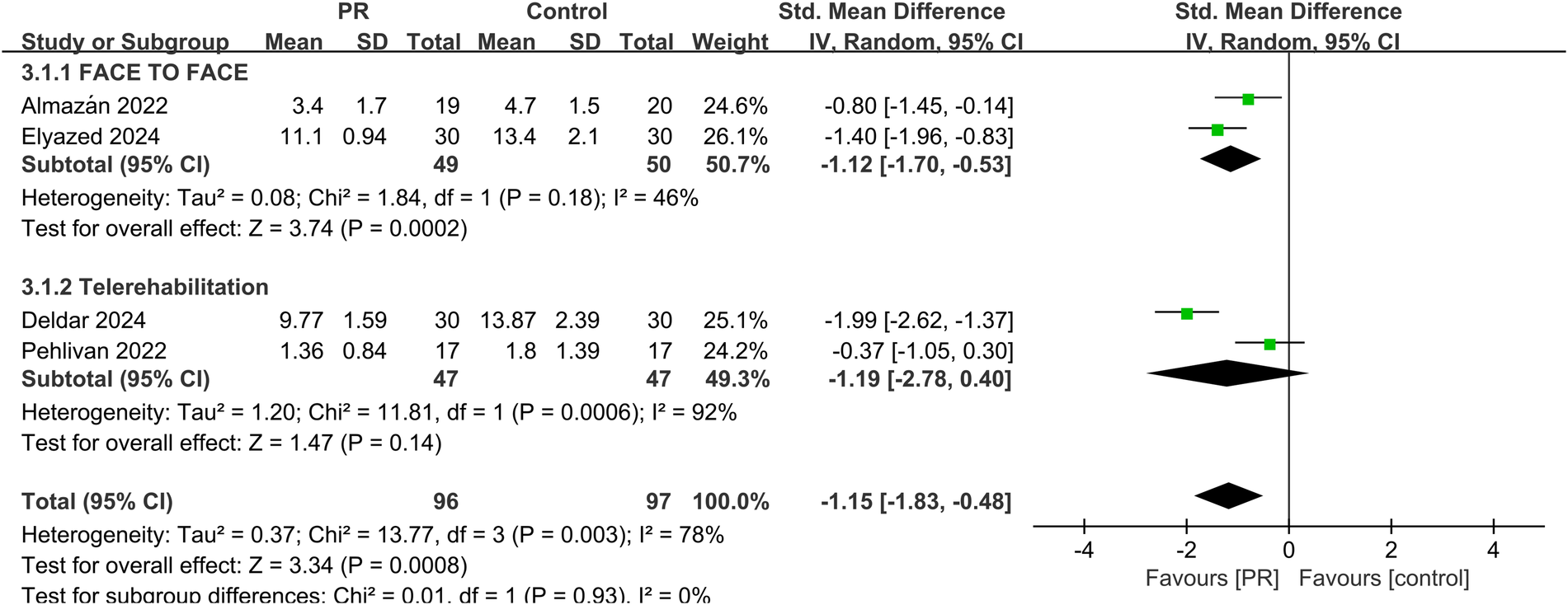

Fatigue was assessed in four studies using validated scales. Meta-analysis showed a significant reduction in fatigue among patients receiving PR (SMD: −1.15, 95% CI: −1.83 to −0.48, p < 0.001), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 78%) shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation vs. control on fatigue.

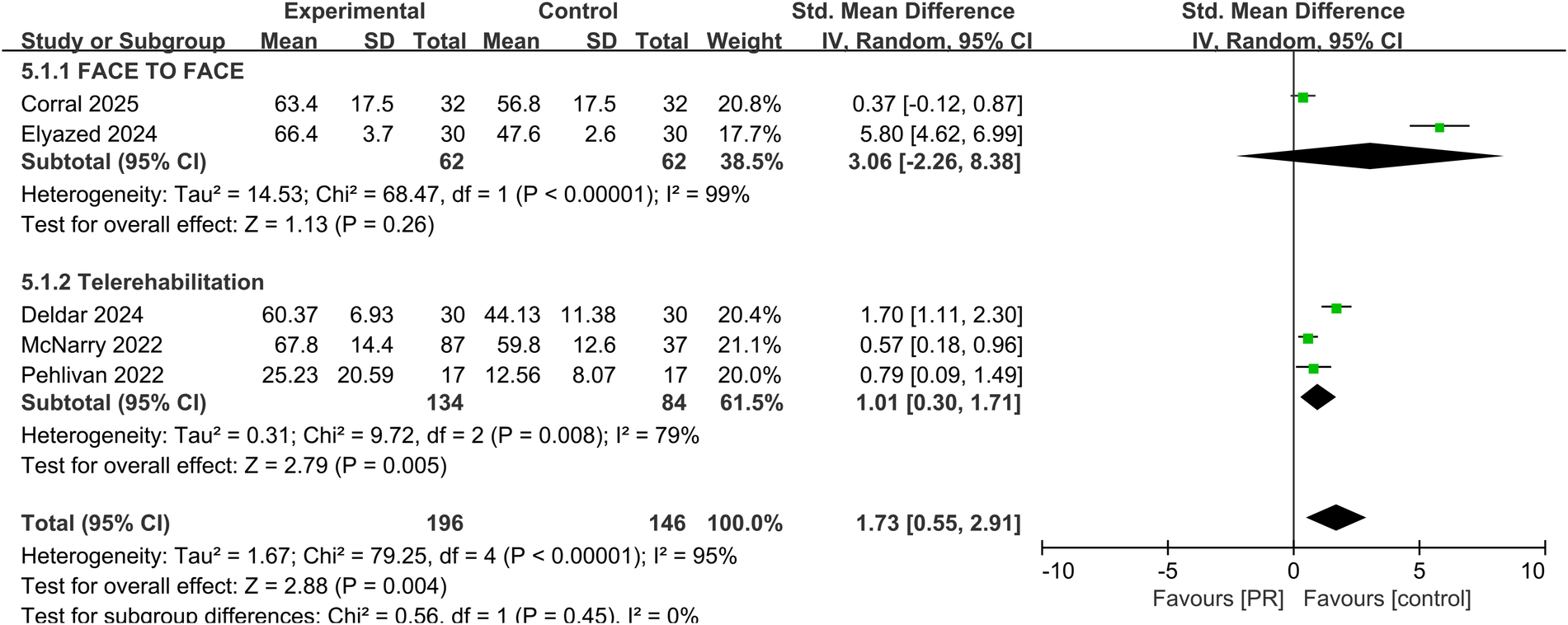

Five studies assessed health-related quality of life using instruments such as the EQ-5D and SF-36. Pooled analysis demonstrated a significant improvement following PR (SMD: 1.73, 95% CI: 0.55–2.91, p = 0.004), though heterogeneity remained high (I2 = 95%) shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation vs. control on the quality of life.

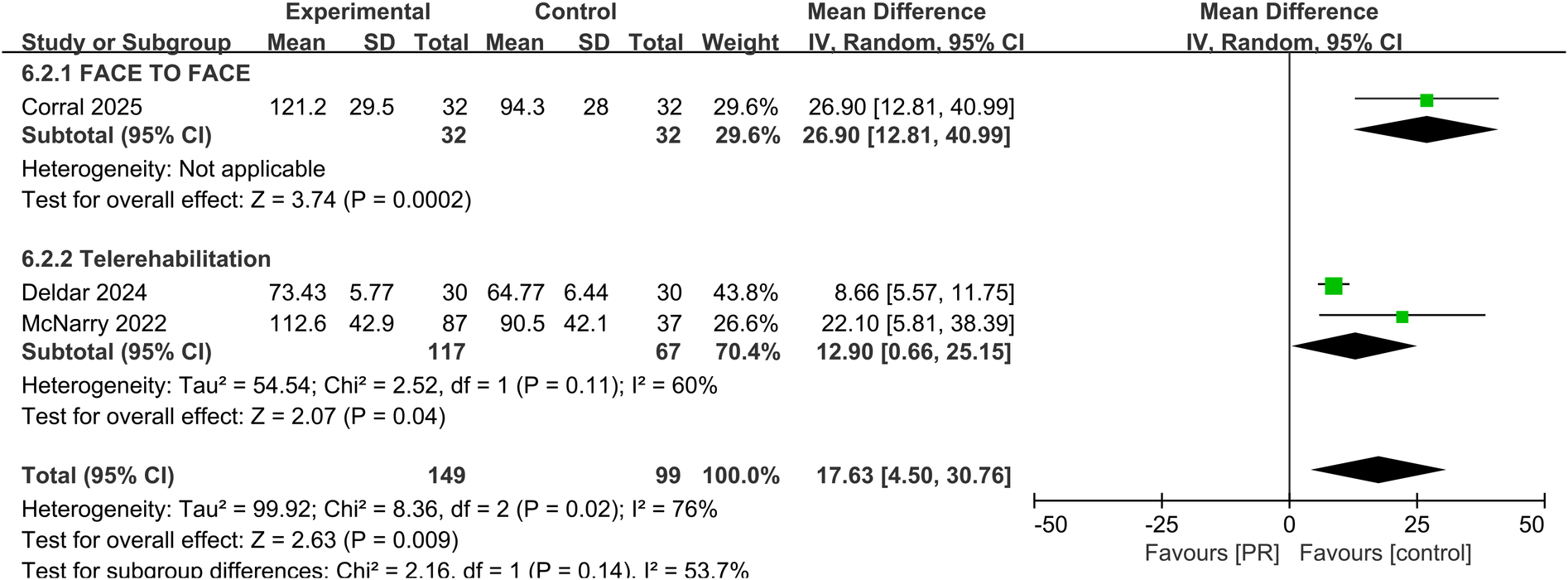

Pulmonary function was evaluated in three studies using MIP. The pooled results showed a significant improvement in MIP in the PR group compared to controls (MD: 17.63 cmH2O, 95% CI: 4.50–30.76, p = 0.009), with moderate-to-substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 76%) showed in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation vs. control on MIP.

3.5 Comparison between telerehabilitation and face-to-face pulmonary rehabilitation

Subgroup analyses comparing telerehabilitation and face-to-face PR revealed no statistically significant differences in clinical outcomes. For exercise capacity, the between-group p-value was 0.84; for dyspnea, p = 0.86; for fatigue, p = 0.93; and for health-related quality of life, p = 0.44. In the analysis of pulmonary function, no heterogeneity was observed among face-to-face PR studies (I2 = 0%), whereas telerehabilitation studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 76%) shown in Figure 7.

4 Discussion

The ten studies included in this review utilized respiratory muscle training or combined endurance-based PR protocols. Comprehensive meta-analytic data demonstrated that PR significantly improved exercise capacity, as measured by the 6MWD, and enhanced pulmonary function, as indicated by MIP. Despite heterogeneity in the assessment tools used across studies for dyspnea, fatigue, and HRQoL, pooled analyses suggested that PR had favorable effects on all three domains. These findings align with prior studies on PR in patients with chronic respiratory diseases and in those recovering from acute COVID-19 infection (12, 31).

Jenkins et al. reported that PR was associated with a reduced risk of hospital readmission in patients with COPD (odds ratio 0.48, 95% CI: 0.30–0.77), as well as improved 6MWD (mean difference 57 m), HRQoL, fatigue, and dyspnea scores (31). Additional studies have confirmed that PR reduces post-discharge morbidity and mortality in COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases (32). The benefits of PR have also been documented in interstitial lung disease, pulmonary nodular disease, and pulmonary hypertension (33, 34).

PR improves overall cardiopulmonary fitness by enhancing the functional performance of respiratory and peripheral muscles, increasing respiratory compliance, reducing the work of breathing, and facilitating the clearance of inflammatory or fibrotic pulmonary lesions (35–38). Notably, the present review found a pooled improvement in 6MWD of 76.85 meters in patients with PASC, which is substantially greater than the average 40-meter improvement typically reported in patients with chronic lung disease (11, 39). These findings not only meet but exceed the minimal important difference threshold of 30 m in 6MWD seen in patients with COPD or interstitial lung disease, underscoring the clinical relevance of PR for patients with PASC.

With respect to fatigue, our findings indicate that PR is effective in reducing fatigue symptoms. However, emerging literature suggests that patients with severe fatigue may benefit most from individualized, multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs combining cardiorespiratory training with psychosocial support (40, 41). Clinicians should therefore approach PR in PASC with careful clinical characterization, standardized symptom assessments, and biopsychosocial profiling to optimize therapeutic benefit and minimize risks.

Although our analysis found a non-significant reduction in dyspnea as measured by the mMRC scale, this is consistent with findings from Oliveira et al. who also reported no significant improvement (mean difference −0.57; 95% CI: −1.32 to 0.17) (42). Several methodological and clinical factors may account for this observation. First, a floor effect may have influenced the detectability of change. In multiple included trials, participants presented with relatively low baseline levels of dyspnea, often reflected by mMRC scores of ≤1, which limits the measurable scope for further improvement. This effect is particularly relevant when sample sizes are modest or variability is high (43). Second, heterogeneity in dyspnea assessment tools represents a significant methodological limitation. Across studies, dyspnea was evaluated using different instruments, including the mMRC, Borg CR10, and visual analogue scales. These tools differ in their psychometric properties, sensitivity to change, and the dimension of breathlessness they capture (e.g., exertional vs. perceived dyspnea), thus reducing outcome comparability and potentially attenuating pooled effect sizes (Martins et al., 2024). In addition, the timing of rehabilitation initiation and the complex etiology of post-COVID dyspnea, which may involve pulmonary, cardiovascular, neuromuscular, and psychological components, further complicate both measurement and intervention response. Hence, the absence of statistically significant improvement in dyspnea likely reflects a confluence of factors, including baseline symptom intensity, tool heterogeneity, and underlying pathophysiology. Future trials should stratify patients by initial dyspnea severity, employ standardized and multidimensional dyspnea assessment instruments, and consider adjunctive therapies such as breathing retraining, inspiratory muscle training, or cognitive-behavioral interventions to more directly address dyspnea mechanisms in PASC populations.

As PR evolves, telerehabilitation has emerged as an increasingly relevant model. It involves digital delivery of supervise exercise, monitoring, and patient engagement through online platforms. It offers logistical advantages, particularly for individuals with limited access to transportation or care facilities (44). Studies have demonstrated that telerehabilitation can incorporate pre- and post-intervention assessments conducted in clinical settings while enabling real-time exercise sessions through videoconferencing (45, 46). Furthermore, telerehabilitation has the potential to reduce costs, increase patient autonomy, and serve as a maintenance strategy for patients with chronic respiratory diseases (47, 48). Diverse models have been applied, including wearable device–integrated platforms and asynchronous video-based monitoring. Despite this variability, high adherence rates and positive user satisfaction have been consistently reported, supporting telerehabilitation as a practical alternative to traditional center-based PR.

To further contextualize these findings, it is important to consider the unique challenges and opportunities associated with implementing telerehabilitation, particularly in rural or resource-constrained settings. In such environments, conventional PR programs are often inaccessible due to infrastructure limitations, workforce shortages, and geographic barriers. The transition to remotely delivered, home-based PR offers a scalable and adaptable solution that may broaden access, particularly during public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (17, 28, 43). However, its successful deployment relies heavily on stable internet infrastructure, patient digital literacy, and supportive policy environments, factors that may be insufficient in low- and middle-income regions. Moreover, our review highlights substantial heterogeneity across studies in terms of rehabilitation modalities (e.g., aerobic, resistance, or inspiratory muscle training), intervention duration, intensity, supervision, and outcome measures. This variability hinders data synthesis and limits the generalizability of findings. The development of standardized, evidence-based PR protocols tailored to PASC is urgently needed. Such protocols should include core components, delivery frameworks, and validated outcome measures to facilitate both clinical implementation and comparative research (49, 50). Finally, while the short-term benefits of PR, including improvements in exercise capacity, fatigue, and quality of life, have been consistently demonstrated, evidence on its long-term effectiveness remains limited. Most included studies had follow-up durations ranging from 6 to 12 weeks, with few assessing outcomes beyond this timeframe. Longitudinal studies with extended follow-up (≥6 months) are critically needed to evaluate the durability of PR benefits, monitor potential relapse in functional status, and assess cost-effectiveness in diverse healthcare systems (51, 52).

In addition, while PR demonstrates clinical benefit for many individuals recovering from PASC, it may not be universally applicable. Post-COVID-19 condition represents a heterogeneous syndrome, encompassing a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes involving respiratory, cardiovascular, neurological, musculoskeletal, and psychological domains (53, 54). A uniform rehabilitation approach risks overlooking subgroups whose predominant manifestations—such as cognitive impairment (“brain fog”), autonomic dysfunction, or post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), may not only fail to benefit from traditional aerobic-based PR but may even deteriorate (4, 55). For these individuals, rehabilitation strategies incorporating symptom pacing, neurocognitive support, and energy-conserving physical activity plans may be more appropriate. Despite these distinctions, most current PR trials do not stratify interventions based on patient phenotype or baseline functional status. Moreover, a lack of consensus on standardized rehabilitation protocols and core outcome sets reduces reproducibility and limits clinical generalizability (56). Long-term evidence is also sparse; only a few studies have assessed sustained outcomes beyond 12 weeks, with limited data on relapse, work reintegration, mental health, or healthcare utilization (51). To optimize post-COVID rehabilitation, future research should focus on identifying the subpopulations most likely to benefit from PR, developing flexible yet standardized intervention frameworks, and evaluating long-term efficacy, adherence, and implementation feasibility within real-world healthcare systems.

There is some variability in the telerehabilitation models used across studies, with some researchers incorporating wearable devices synchronized to online platforms, while others used video-based systems to monitor and record patient performance asynchronously. Despite these differences, patient adherence rates were generally high, and most studies reported favorable feedback regarding accessibility and satisfaction with the telerehabilitation format. This supports telerehabilitation as a feasible alternative to in-person PR, though future research is needed to establish optimal delivery protocols and long-term outcomes.

This study performed subgroup analyses stratified by in-person and remote rehabilitation modalities; however, the results continued to exhibit high heterogeneity. The underlying causes may be linked to variations in patient characteristics, assessment tools, intervention timing, and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) protocols. First, while the baseline characteristics of the included patients did not show statistically significant differences, subgroup analyses based on symptom profiles revealed disparities in responsiveness to PR. Research has demonstrated that PR models focused on respiratory rehabilitation yield superior efficacy in subgroups primarily presenting with dyspnea and cardiopulmonary sequelae (57). In contrast, greater heterogeneity and inconsistent effectiveness were observed in subgroups dominated by primary fatigue and neurocognitive sequelae. This phenomenon may be attributed to the lack of targeted functional exercise interventions for these specific symptoms in existing PR protocols (57, 58). Second, intervention timing constitutes another source of heterogeneity, as the duration of illness and stage of recovery influence PR outcomes. PR interventions produce more consistent effects during the early phase of post-COVID syndrome, where sequelae are often associated with acute-phase physical deconditioning. In the late phase, however, outcomes become more variable. This variability may stem from the complexity of the underlying mechanisms in late-stage sequelae, such as persistent immune dysregulation and autonomic dysfunction (42). Additionally, comorbidities among the included patients may contribute to heterogeneity. Patients with pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular conditions derive more consistent benefits from PR (59), whereas those with metabolic comorbidities exhibit greater variability in outcomes. This discrepancy could arise because comorbidities affect the body's tolerance of and adherence to PR interventions. Furthermore, differences in intervention protocols contribute to heterogeneity. Variations in intervention combinations, exercise intensity, and frequency all lead to divergent results. In the context of remote PR, disparities in technical support—such as real-time physiological monitoring and dynamic protocol adjustments using smart wearable devices in some studies vs. fixed exercise guidance via video alone in others—directly impact intervention effectiveness due to differing levels of technological empowerment. Moreover, variations in assessment tools represent a source of heterogeneity. Fundamental differences exist in tool focus, scoring methodologies, and measurement dimensions, which may introduce heterogeneity when aggregating results.

All included studies in this research are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), each employing randomization and allocation concealment procedures. However, unmeasured confounding factors persist in group assignment. For instance, clinicians may be more inclined to allocate patients with better baseline exercise capacity or stronger social support to the PR intervention group. Such biases could influence unmeasured variables affecting outcomes, such as treatment adherence. When allocation bias is present, statistical adjustments often fail to account for imbalances in key variables, including symptom severity, comorbidity burden, or prior rehabilitation experience. These residual confounding factors obscure the true effectiveness of PR, leading to either overestimation or underestimation of its efficacy in specific post-COVID syndrome subgroups. Notably, allocation bias and heterogeneity are interconnected: biased allocation may exaggerate outcome differences between subgroups and mask the genuine effects of PR.

In conclusion, clarifying the boundaries of heterogeneity shaped by symptom subgroups, timing of intervention, and comorbidities helps us understand when and for which patients pulmonary rehabilitation models are most effective in post-COVID syndrome. Addressing allocation bias through rigorous randomization, transparent reporting of allocation methods, and robust adjustment for confounding factors is crucial for enhancing the external validity of pulmonary rehabilitation research across diverse populations.

This review has several limitations. First, there was substantial heterogeneity in intervention protocols, duration, and outcome measurement tools across studies, which limits the precision of effect estimates. Second, the overall number of eligible RCTs remains limited, and many included studies had small sample sizes. Third, due to variability in terminology and symptom classification, some potentially relevant studies may have been missed despite comprehensive search efforts. Finally, the included trials lacked long-term follow-up data, making it difficult to assess the sustainability of PR benefits in patients with PASC.

5 Conclusion

PR significantly improves exercise capacity, pulmonary function, fatigue, and quality of life in patients with PASC. Although the improvement in dyspnea was not statistically significant, the direction of effect remained favorable. Telerehabilitation appears to be a promising alternative to face-to-face PR, offering comparable clinical benefits while improving accessibility. Future high-quality RCTs with standardized protocols and long-term follow-up are warranted to optimize PR strategies and delivery models in this growing patient population.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

YY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XH: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. LD: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. QA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JG: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 82560660), the Scientists Fund of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University, China (Grant no. ldyyyn2021-132), the Gansu Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant no.24JRRA1073), and WU JIEPING MEDICAL FOUNDATION (Grant no.6750.2022-02-8). Jing Gao was supported by Karolinska Institutet Research Foundation Grants (2022-02329) and the Scientists Fund of the Gansu Provincial Hospital of China (Grant no. 2024KYQDJ-A-2; no. 24GSSYA-9). The funder has no role in the data collection, data analysis, preparation of manuscript and decision to submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2025.1634351/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online at:https://covid19.who.int (Accessed April 27, 2022).

2.

Chen C Haupert SR Zimmermann L Shi X Fritsche LG Mukherjee B . Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. (2022) 226:1593–607. 10.1093/infdis/jiac136

3.

Parums DV . Editorial: long COVID, post-COVID syndrome, and the global impact on health care. Med Sci Monit. (2021) 27:e933446. 10.12659/MSM.933446

4.

Davis HE Assaf GS McCorkell L Wei H Low RJ Re'em Y et al Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. (2021) 38:101019. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

5.

Rodriguez-Morales AJ Cardona-Ospina JA Gutiérrez-Ocampo E Villamizar-Peña R Holguin-Rivera Y Escalera-Antezana JP et al Clinical, laboratory, and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2020) 34:101623. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623

6.

Rodríguez Ledo P Armenteros del Olmo L Rodríguez Rodríguez E Gomez Acebo F . Description of the 201 symptoms of multi-organ involvement produced in patients affected by persistent COVID-19. Med Gen Fam. (2021) 10:60–8. 10.24038/mgyf.2021.016

7.

Premraj L Kannapadi NV Briggs J Seal SM Battaglini D Fanning J et al Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. (2022) 434:120162. 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120162

8.

Chen H Shi H Liu X Sun T Wu J Liu Z . Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 9:837420. 10.3389/fmed.2022.837420

9.

Fugazzaro S Contri A Esseroukh O Kaleci S Croci S Massari M et al Rehabilitation interventions for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5185. 10.3390/ijerph19095185

10.

Shah W Hillman T Playford ED Hishmeh L . Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19: summary of NICE, SIGN, and RCGP rapid guideline. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n136. 10.1136/bmj.n136

11.

McCarthy B Casey D Devane D Murphy K Murphy E Lacasse Y . Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) (2):CD003793. 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3

12.

Ahmed I Mustafaoglu R Yeldan I Yasaci Z Erhan B . Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation approaches on dyspnea, exercise capacity, fatigue, lung functions, and quality of life in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2022) 103(10):2051–62. 10.1016/j.apmr.2022.06.007

13.

Torres-Castro R Núñez-Cortés R Larrateguy S Alsina-Restoy X Barberà JA Gimeno-Santos E et al How is the appropriate test chosen to assess exercise capacity in post-COVID-19 patients? Life (Basel). (2023) 13(3):621. 10.3390/life13030621

14.

Modi P Kulkarni S Nair G Kapur R Chaudhary S Langade D et al Evaluation of post-COVID functional capacity and oxygen desaturation using the 6-minute walk test—an observational study. Eur Respir J. (2021) 58:3162. 10.1183/13993003

15.

Chaiwong W Deesomchok A Pothirat C Liwsrisakun C Duangjit P Bumroongkit C et al The long-term impact of COVID-19 pneumonia on pulmonary function and exercise capacity. J Thorac Dis. (2023) 15(9):4725–35. 10.21037/jtd-23-514

16.

Brennan K Curran J Barlow A Jayaraman A . Telerehabilitation in neurorehabilitation: has it passed the COVID test?Expert Rev Neurother. (2021) 21(8):833–6. 10.1080/14737175.2021.1958676

17.

Li J Xia W Zhan C Liu S Yin Z Wang J et al A telerehabilitation programme in post-discharge COVID-19 patients (TERECO): a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. (2022) 77(7):697–706. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217382

18.

Pleguezuelos E Del Carmen A Moreno E Serra-Prat M Serra-Payá N Garnacho-Castaño MV . Telerehabilitation improves cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness and body composition in older people with post-COVID-19 syndrome. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. (2024) 15(5):1785–96. 10.1002/jcsm.13530

19.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

20.

Del Corral T Fabero-Garrido R Plaza-Manzano G Izquierdo-García J López-Sáez M García-García R et al Effect of respiratory rehabilitation on quality of life in individuals with post-COVID-19 symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2025) 68(1):101920. 10.1016/j.rehab.2024.101920

21.

Deldar K Khodabandeloo F Kargar N Basiri R Froutan R RezaMazlom S . Effect of respiratory telerehabilitation on pulmonary function parameters and quality of life in patients with COVID-19: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. (2024) 11(1):2345–5756. 10.5812/jnms-144234

22.

Elyazed TIA Alsharawy LA Salem SE Helmy NA El-Hakim AAEA . Effect of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation on exercise capacity in post-COVID-19 patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. (2024) 21(1):1743-0003. 10.1186/s12984-024-01340-x

23.

Alsharidah AS Kamel FH Alanazi AA Alhawsah EA Alharbi HK Alrshedi ZO et al A pulmonary telerehabilitation program improves exercise capacity and quality of life in young females post-COVID-19 patients. Ann Rehabil Med. (2023) 47(6):502–10. 10.5535/arm.23060

24.

McNarry MA Berg RMG Shelley J Duckers J Lewis K Davies GA et al Inspiratory muscle training enhances recovery post-COVID-19: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. (2022) 60(4):2103101. 10.1183/13993003.03101-2021

25.

Pehlivan E Palali I Atan SG Turan D Çinarka H Çetinkaya E . The effectiveness of POST-DISCHARGE telerehabilitation practices in COVID-19 patients: tele-COVID study-randomized controlled trial. Ann Thorac Med. (2022) 17(2):110–7. 10.4103/atm.atm_543_21

26.

Okan F Okan S Duran Yücesoy F . Evaluating the efficiency of breathing exercises via telemedicine in post-COVID-19 patients: randomized controlled study. Clin Nurs Res. (2022) 31(5):771–81. 10.1177/10547738221097241

27.

Jimeno-Almazán A Franco-López F Buendía-Romero Á Martínez-Cava A Sánchez-Agar JA Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez BJ et al Rehabilitation for post-COVID-19 condition through a supervised exercise intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2022) 32(12):1791–801. 10.1111/sms.14240

28.

Capin JJ Jolley SE Morrow M Connors M Hare K MaWhinney S et al Safety, feasibility, and initial efficacy of an app-facilitated telerehabilitation (AFTER) programme for COVID-19 survivors: a pilot randomised study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12(7):e061285. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061285

29.

Singh SJ Puhan MA Andrianopoulos V Hernandes NA Mitchell KE Hill CJ et al An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. (2014) 44:1447–78. 10.1183/09031936.00150414

30.

Bohannon RW Crouch R . Minimal clinically significant difference for change in 6-minute walk test distance of adults with pathology: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. (2017) 23:377–81. 10.1111/jep.12629

31.

Jenkins AR Burtin C Camp PG Lindenauer P Carlin B Alison JA et al Do pulmonary rehabilitation programmes improve outcomes in patients with COPD posthospital discharge for exacerbation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. (2024) 79(5):438–47. 10.1136/thorax-2023-220333

32.

Lindenauer PK Stefan MS Pekow PS Mazor KM Priya A Spitzer KA et al Association between initiation of pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalization for COPD and 1-year survival among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. (2020) 323(18):1813–23. 10.1001/jama.2020.4437

33.

Alsina-Restoy X Torres-Castro R Caballería E Gimeno-Santos E Solis-Navarro L Francesqui J et al Pulmonary rehabilitation in sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. (2023) 219:107432. 10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107432

34.

Reina-Gutiérrez S Torres-Costoso A Martínez-Vizcaíno V Núñez de Arenas-Arroyo S Fernández-Rodríguez R Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP . Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in interstitial lung disease, including coronavirus diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2021) 102(10):1989–1997.e3. 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.03.035

35.

Rochester CL Vogiatzis I Holland AE Lareau SC Marciniuk DD Puhan MA et al ATS/ERS Task Force on Policy in Pulmonary Rehabilitation, et al. An official American thoracic society/European respiratory society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2015) 192(11):1373–86. 10.1164/rccm.201510-1966ST

36.

Zeng B Chen D Qiu Z Zhang M Wang G Rehabilitation Group of Geriatric Medicine branch of Chinese Medical Association et al Expert consensus on protocol of rehabilitation for COVID-19 patients using framework and approaches of WHO international family classifications. Aging Med (Milton). (2020) 3(2):82–94. 10.1002/agm2.12120

37.

Cui L Liu H Sun L . Multidisciplinary respiratory rehabilitation combined with non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in treating elderly patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pak J Med Sci. (2019) 35(2):500–5. 10.12669/pjms.35.2.459

38.

Rochester CL Spruit MA Holland AE . Pulmonary rehabilitation in 2021. JAMA. (2021) 326(10):969–70. 10.1001/jama.2021.6560

39.

Dowman L Hill CJ May A Holland AE . Pulmonary rehabilitation for interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021) 2:CD006322. 10.1002/14651858.CD003200.pub9

40.

Larun L Brurberg KG Odgaard-Jensen J Price JR . Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 10:CD003200. 10.1002/14651858

41.

Bansal R Gubbi S Koch CA . COVID-19 and chronic fatigue syndrome: an endocrine perspective. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. (2022) 27:100284. 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100284

42.

Oliveira MR Hoffman M Jones AW Holland AE Borghi-Silva A . Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on exercise capacity, dyspnea, fatigue, and peripheral muscle strength in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2024) 105(8):1559–70. 10.1016/j.apmr.2024.01.007

43.

Martins RL Monteiro EDSS de Lima AMJ Santos ADC Brasileiro-Santos MDS . Effect of telerehabilitation on pulmonary function, functional capacity, physical fitness, dyspnea, fatigue, and quality of life in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and metanalysis. Telemed J E Health. (2024) 30(8):e2256–86. 10.1089/tmj.2023.0653

44.

Mukaino M Tatemoto T Kumazawa N Tanabe S Katoh M Saitoh E et al Staying active in isolation: telerehabilitation for individuals with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2020) 99(6):478–89. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001441

45.

Zanaboni P Hoaas H Aarøen Lien L Hjalmarsen A Wootton R . Long-term exercise maintenance in COPD via telerehabilitation: a two-year pilot study. J Telemed Telecare. (2017) 23:74–82. 10.1177/1357633X15625545

46.

Hansen H Bieler T Beyer N Godtfredsen N Kallemose T Frølich A . COPD online-rehabilitation versus conventional COPD rehabilitation – rationale and design for a multicenter randomized controlled trial study protocol (CORe trial). BMC Pulm Med. (2017) 17:140. 10.1186/s12890-017-0488-1

47.

Burge AT Holland AE McDonald CF Abramson MJ Hill CJ Lee AL et al Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD using minimal resources: an economic analysis. Respirology. (2020) 25(2):183–90. 10.1111/resp.13667

48.

Malaguti C Dal Corso S Janjua S Holland AE . Supervised maintenance programmes following pulmonary rehabilitation compared to usual chronic obstructive pulmonary disease care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021) 8(8):CD013569. 10.1002/14651858.CD013569.pub2

49.

Spruit MA Holland AE Singh SJ Tonia T Wilson KC Troosters T . COVID-19: interim guidance on rehabilitation in the hospital and post-hospital phase from a European Respiratory Society- and American Thoracic Society-coordinated international task force. Eur Respir J. (2020) 56(6):2002197. 10.1183/13993003.02197-2020

50.

Holland AE Cox NS Houchen-Wolloff L Rochester CL Garvey C ZuWallack R et al Defining modern pulmonary rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2021) 18(5):e12–29. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202102-146ST

51.

Daynes E Gerlis C Chaplin E Gardiner N Singh SJ . Early experiences of rehabilitation for individuals post-COVID to improve fatigue, breathlessness exercise capacity and cognition - a cohort study. Chron Respir Dis. (2021) 18:14799731211015691. 10.1177/14799731211015691

52.

Barker-Davies RM O'Sullivan O Senaratne KPP Baker P Cranley M Dharm-Datta S et al The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med. (2020) 54(16):949–59. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596

53.

Soriano JB Murthy S Marshall JC Relan P Diaz JV . WHO clinical case definition working group on post-COVID-19 condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. (2022) 22(4):e102–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9

54.

Huang C Huang L Wang Y Li X Ren L Gu X et al 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. (2021) 397(10270):220–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

55.

Komaroff AL Bateman L . Will COVID-19 lead to myalgic encephalomyeli-tis/chronic fatigue syndrome?Front Med (Lausanne). (2021) 7:606824. 10.3389/fmed.2020.606824

56.

Evans RA McAuley H Harrison EM Shikotra A Singapuri A Sereno M et al PHOSP-COVID Collaborative Group, et al. Physical, cognitive, and mental health impacts of COVID-19 after hospitalisation (PHOSP-COVID): a UK multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. (2021) 9(11):1275–87. 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00383-0

57.

Szarvas Z Fekete M Horvath R Shimizu M Tsuhiya F Choi HE et al Cardiopulmonary rehabilitation programme improves physical health and quality of life in post-COVID syndrome. Ann Palliat Med. (2023) 12(3):548–60. 10.21037/apm-22-1143

58.

Cordani C Young VM Arienti C Lazzarini SG Del Furia MJ Negrini S et al Cognitive impairment, anxiety and depression: a map of cochrane evidence relevant to rehabilitation for people with post COVID-19 condition. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2022) 58(6):880–7. 10.23736/S1973-9087.22.07813-3

59.

Timoteo EF Silva DF Oliveira TM José A Malaguti C . Real-time telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease and post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. (2025) 31(7):991–1004. 10.1177/1357633X241241572

Summary

Keywords

pulmonary rehabilitation, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, telerehabilitation, fatigue, exercise capacity

Citation

Yue Y, Han X, Chen Q, Dai L, Ai Q, Zhang Z, Ma F and Gao J (2025) The effect of pulmonary rehabilitation for post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 6:1634351. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2025.1634351

Received

27 May 2025

Accepted

30 September 2025

Published

31 October 2025

Volume

6 - 2025

Edited by

Christina May Moran de Brito, Hospital Sirio Libanes, Brazil

Reviewed by

Enrico M. Clini, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy

Guido Levi, ASST Spedali Civili, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yue, Han, Chen, Dai, Ai, Zhang, Ma and Gao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Zhigang Zhang zzg3444@163.com Jing Gao jing.gao@ki.se Fangli Ma fang.mary@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.