Abstract

Wearable sensors are revolutionizing personal healthcare by enabling continuous, real-time monitoring of vital physiological signals, which supports early diagnosis, disease management, and improved quality of life. MXenes, a novel class of two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides, have emerged as promising materials for next-generation wearable sensors due to their exceptional electrical conductivity, mechanical flexibility, hydrophilicity, and versatile surface chemistry. These unique properties enable high sensitivity, fast response, and robust multifunctionality necessary for detecting a wide range of physiological parameters, including pressure, strain, temperature, humidity, and biochemical markers. Recent breakthroughs in MXene-based wearable devices demonstrate their capability for multimodal sensing, self-powered operation, and seamless integration with flexible substrates. This review provides a comprehensive overview of structural and functional features of MXenes relevant to sensing devices. Despite significant progress, challenges such as biocompatibility, environmental stability, and scalable manufacturing remain critical. In future, advances in MXene composites, hybrid sensor platforms, and AI-driven data analytics hold great promise to drive MXene wearable sensors toward widespread clinical and commercial adoption for personalized healthcare.

1 Introduction

Over the past century, rapid technological and economic advancements have significantly transformed the quality of life and lifestyle across the globe (Tricoli et al., 2017; Trung and Lee, 2016). These developments have played an essential role in improving daily living conditions, with one of the most notable outcomes being the dramatic increase in life expectancy, from less than 50 years at the beginning of the century to over 80 years in many developed countries today (Mathers et al., 2015; Bor et al., 2013). This rise in life expectancy can be attributed to several key factors, including enhanced food security and breakthroughs in healthcare. Innovations such as the mass production of essential medications, the development of advanced medical technologies and procedures (e.g., keyhole surgery, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography) have revolutionized medical care (Mathers et al., 2015; Bor et al., 2013). These advancements continue to accelerate, now enabling the design and commercialization of synthetic organs that mimic the function of natural ones, once considered a distant possibility. Despite global recognition of these medical innovations, many underdeveloped countries still face life expectancies between 50 and 60 years (Bor et al., 2013). The financial burden on developing nations to access these technologies, coupled with systemic challenges in underdeveloped regions, emphasize the urgent need for alternative, economically sustainable healthcare solutions (Bor et al., 2013). Preventive and personalized healthcare approaches offer promising solutions to these challenges (Tricoli et al., 2017).

Early disease detection facilitates timely and cost-effective treatment, while continuous monitoring of key biomarkers and proactive interventions can help prevent the progression of chronic illnesses. Large-scale screening has proven effective in combating diseases such as prostate and breast cancer (Tricoli et al., 2017). However, the high costs associated with traditional diagnostic methods limit their applicability for broader disease screening. This has led to a paradigm shift toward novel wearable electronic technologies that support lifestyle monitoring and health diagnostics (Tricoli et al., 2017; Trung and Lee, 2016; Kim and Shin, 2015; Carpenter and Frontera, 2016). Initially designed for personal data tracking, many of these devices are now capable of collecting and correlating health data across millions of users, offering valuable insights into individual and population-level health trends (Kim and Shin, 2015; Carpenter and Frontera, 2016; Ioannidis et al., 2019). Such data-driven approaches enable early detection, prevention, and treatment of complex diseases at a fraction of the traditional cost (Ioannidis et al., 2019). The development of miniaturized, flexible, and reliable wearable devices has become a driving force in the resurgence of sensor-based analytical chemistry. This shift has moved the field beyond traditional chemical and process engineering into the realms of biotechnology and commercial electronics. Nanotechnology plays a central role in this transformation, enabling the fabrication of highly sensitive sensing devices with enhanced detection limits, improved selectivity, and reduced energy consumption (Ndlovu et al., 2024; Miya et al., 2023; Ambaye et al., 2024; Mhlanga et al., 2024). These nanomaterials have been successfully applied in disease detection, such as glucose monitoring, transitioning from invasive electrochemical sensors to non-invasive methods like breath analysis (Mhlanga et al., 2024). For example, nanostructured materials capable of detecting acetone, a key biomarker for glucose, in human breath at parts-per-billion levels have been developed (Mhlanga et al., 2024; Ju et al., 2015). Innovations also include flexible polymer lenses for real-time tear analysis (Chu et al., 2011) and ingestible gas-sensing capsules (Kalantar-Zadeh et al., 2016) that monitor digestive biomarkers, offering new insights into metabolic processes and disorders. Such successes have spurred further research into expanding the range of detectable biomarkers and improving sensing technologies for various diseases. The continued evolution of these approaches holds great promise for advancing personalized and preventive medicine, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Two-dimensional (2D) nanostructured materials received a lot of attention because of their unique features, such as surface-to-volume ratio, good flexibility, tunable electronic structure and excellent mechanical robustness (Naguib et al., 2023; Su et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2026; Wu et al., 2025). These characteristics make them ideal building blocks for the development of advanced technologies aimed at addressing challenges in healthcare and related fields. Amongst them, MXenes, known as 2D transition-metal carbides/nitrides, have gained a lot of attention, especially for the fabrication of novel flexible sensing devices (Pei et al., 2021; Riazi et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). These materials possess remarkable thermal conductivity, tunable bandgap, good mechanical strength, and a hydrophilic tunable surface, making them an ideal platform for developing advanced sensing devices. MXenes consists of transition metals (M) separated by certain number (n) of nitrogen or carbon layers (X), and terminated with surface functionalities (Tx) such as -F, -OH and -O. These materials are typically derived from MAX phases, which follow the general formula Mn+1AXn, through various synthesis methods that influence the resulting surface functionalities. The chemical formula of MXenes is generally represented as Mn+1XnTx, where n can be 1, 2, 3, or 4. For readers interested in recent advances in the synthesis and characterization of MXenes, several comprehensive reviews have been published (Yang et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2022; Kota et al., 2024; Borah et al., 2025; Sultana et al., 2025; Babar et al., 2025; Antony Jose et al., 2025; Elsa et al., 2025; Munir and Khalid, 2025; Hsu et al., 2025). Recently, number of reviews dedicated to MXene-based sensors have been published. Kota et al. (2024) reviewed the use of MXenes their application in electrochemical sensor and glucose, Hsu et al. (2025) reviewed the use of MXene for pesticides detection and electrochemical sensors, Pengsomjit et al. (2024) investigated the use of MXene-based miniaturized sensors environmental analysis and monitoring, Hussain et al. (2024) reviewed the use of Ti3C2Tx MXene electrochemical sensor with a section highlighting wearable sensors. However, dedicated reviews focusing on MXenes in sensor applications, particularly wearable sensors for healthcare, remain limited (Mohanapriya et al., 2024). Given their unique combination of properties including tunable surface functionalities, exceptional electrical conductivity, robust mechanical performance, excellent hydrophilicity, and biocompatibility, MXenes have emerged as highly promising materials for wearable healthcare sensors. These attributes make them ideal for biosensing, diagnostics, therapeutic interventions, and antibacterial applications, with hybrid systems integrating MXenes and other functional nanostructures further enhancing multifunctionality in health monitoring platforms. Despite a growing body of research on MXene manufacturing, the literature lacks a comprehensive synthesis of recent advances, particularly regarding their application in wearable devices for real-time analysis and monitoring. This review addresses these gaps by highlighting the latest progress in MXene synthesis and discussing emerging developments in wearable healthcare sensor applications.

2 MXenes structure, properties and synthesis

2.1 Structure of MXenes

Since the groundbreaking discovery of graphene in 2004, there has been a growing interest in synthesizing 2D materials with exceptional functional and physicochemical properties (Jarillo-Herrero, 2024; Bisht et al., 2024). This has led to the development of a diverse range of 2D materials, including germanene, graphitic carbon nitride, metal dichalcogenides, phosphorene, and metal oxides, all of which hold great promise for transforming technologies and improving human life (Bisht et al., 2024). Technological advances have further accelerated the search for novel 2D materials to keep pace with emerging demands. This pursuit culminated in the discovery of MXenes in 2011, and since then, more than 100 MXene variants have been reported in the scientific literature (Yang et al., 2024; Naguib et al., 2021; Lipatov et al., 2016). Among these various MXenes, Ti3C2 and Ti2C are among the most extensively studied. MXenes are synthesized from the Mn+1AXn (MAX) phases, where M is a transition metal (such as Mo, Nb, Ti, Cr, V, etc.), A is an element from group 13 or 14 (such as Al, Si, Ge, Ga, etc.), and X represents either carbon or nitrogen. The M-A bond is metallic in nature, making it resistant to mechanical breakdown. In contrast, the M-X bond exhibits a combination of ionic, metallic, and covalent characteristics, which makes it more susceptible to mechanical exfoliation and easier to break down during processing. MXenes are often synthesized by selectively etching the A-layer from MAX phase precursors. This process typically involves the use of hydrofluoric acid (HF) or in situ generated HF, which effectively removes the A element, as illustrated in Equation 1:

Following etching, the resulting product is sonicated to yield exfoliated MXene nanosheets. However, due to the hazardous nature of fluorine-based etchants, research efforts have intensified to develop safer, fluorine-free synthesis methods (Li et al., 2019a), as discussed in the next section.

2.2 Synthesis

MXenes can be attained through two main processes, viz either top down or bottom-up approach (Lipatov et al., 2016). MXenes nanosheets are generally attained from top-down approach by etching MAX phases.

In top-down synthesis of MXenes, HF etching remains the most commonly employed method (Anasori et al., 2016). This process involves the selective removal of the ‘A’ element from the MAX phase, followed by a delamination step. During etching, the dense, solid MAX transforms into loosely packed, accordion-like multilayered MXenes, necessitating exfoliation to isolate monolayers. Exfoliation is typically facilitated by intercalants; large organic molecules that insert between the layers; followed by mechanical agitation such as sonication. The etching process is kinetically controlled, with several parameters influencing the final MXene product, including etching time, temperature, and etchant concentration. Generally, MAX phases with a lower ‘n’ value in the formula Mn+1AXn require shorter etching durations and lower temperatures.

Although HF is widely used, its toxicity has prompted the development of safer alternatives. One such approach involves the in situ generation of HF by reacting hydrochloric acid (HCl) with fluoride salts. Lipatov et al. (2016) demonstrated this method by dissolving LiF in 6M HCl at room temperature, followed by the addition of Ti3AlC3 (LiF:MAX ratio of 5:1). The mixture was stirred at 35 °C for 24 h, maintaining a neutral pH. After washing and drying, the material was sonicated in deionized water under inert conditions. In a similar experiment, a higher LiF:MAX ratio of 7.5:1 was used, but without the sonication step. This resulted in MXenes of higher quality and larger size, attributed to the increased availability of Li+ ions, which intercalated between the layers and facilitated Al removal, eliminating the need for mechanical exfoliation (Lipatov et al., 2016).

Another safer and milder etchant, ammonium bifluoride (NH4HF2), has also been reported (Halim et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2017). Halim et al. (2014) used a 1M NH4HF2 solution to, etch MAX phases, optimizing reaction parameters to enhance performance. The etching successfully removed Al, enlarging the interlayer spacing and introducing functional groups such as NH4+, F−, OH−, and = O. SEM and TEM images confirmed the exfoliation of Ti3AlC2 into Ti3C2 after 8 h of treatment at 60 °C (see Figure 1). Post-thermal treatment could further expand the interlayer spacing, and the resulting MXenes (Halim et al., 2014). Such process is reported to afford nanosheets intercalated with various species, including NH3 and NH4+ species. When compared to HF-etched MXenes, those etched with NH4HF2 exhibited a 25% increase in the c-lattice parameter (approximately 25 Å), along with improved transparency and electrical resistivity (Halim et al., 2014). Despite these differences, the nominal thickness remained consistent, and the materials retained metallic conductivity down to 100 K.

FIGURE 1

SEM and TEM images of MAX and MXene (a) SEM of MAX phase; (b) SEM image of the resulting MXene; (c) TEM of MAX phase; and (d) TEM of the MXene. Images reproduced with permission from (Feng et al., 2017).

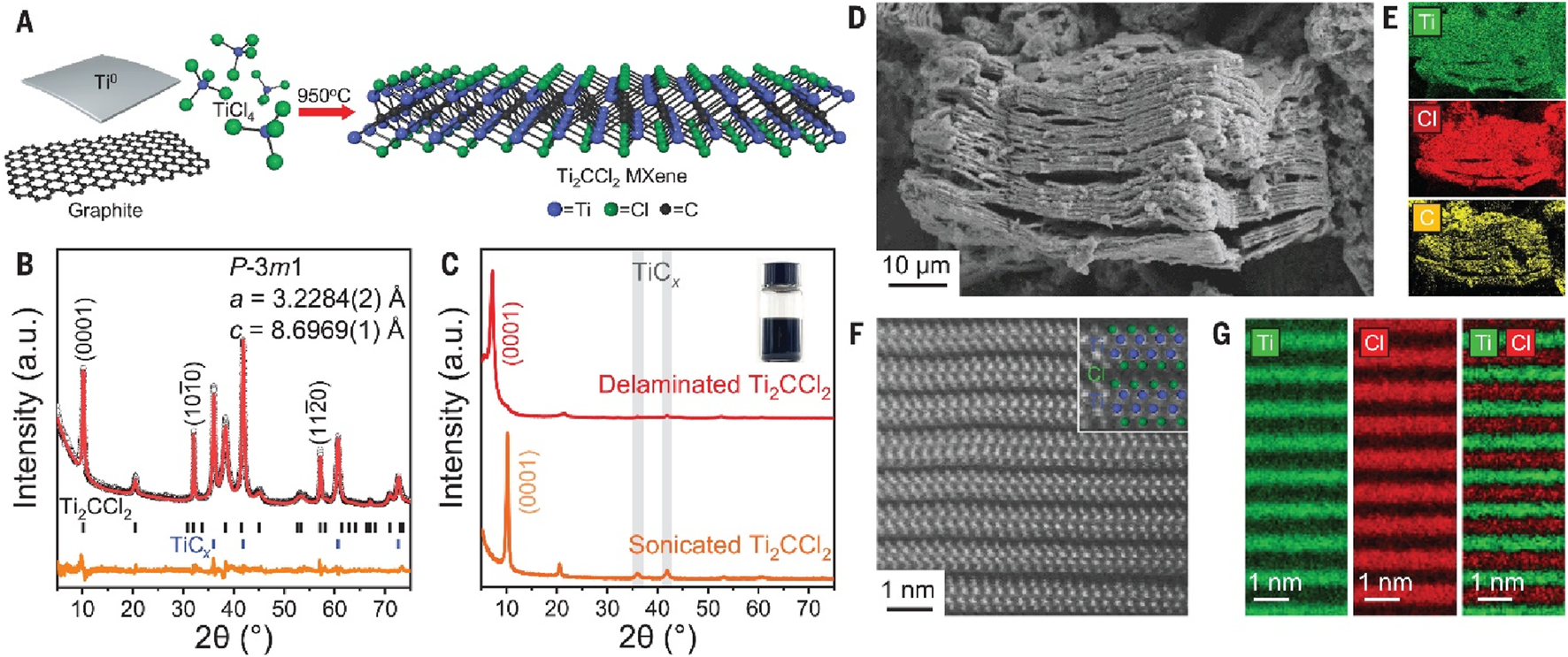

Beyond the top-down approach, the bottom-up strategies have been utilized to produce high quality and large surface area MXenes (Xu et al., 2015). Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) has been employed to synthesize various MXenes, including Mo2C (Xu et al., 2015), TaN (Wang et al., 2017), Ti2CCl2 (Wang et al., 2023) and ReC (Qi et al., 2017). Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2023) successfully synthesized Ti2CCl2 via a high-temperature reaction involving titanium, graphite, and titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4), as illustrated in Figure 2A. Finely ground titanium and graphite powders were combined with 1:1 M equivalents of TiCl4, sealed in a quartz ampoule, and heated to 950 °C within 20 min. The reaction was maintained at this temperature for 2 h. The formation of MXene was confirmed through X-ray diffraction (XRD) and structural analysis using Rietveld refinement, which revealed the presence of the Ti2CCl2 phase with lattice parameters of a = 3.2284 (2) Å and c = 8.6969 (1) Å (Figure 2B). The cubic structure was preserved during delamination, whether performed via ultrasonication in propylene carbonate or using n-butyllithium (Figure 2C). As shown in Figure 2D, SEM images revealed the characteristic accordion-like morphology similar to that observed in HF-etched MXenes. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) elemental mapping confirmed the successful synthesis of Ti2CCl2 MXene (Figures 2E–G). The resulting nanosheets exhibited a near-ideal atomic ratio of titanium to chlorine (Ti:Cl = 49.9:50.1), indicating a stoichiometry close to 1:1.

FIGURE 2

Direct synthesis and characterization of MXene. (A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis process. (B) X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern and Rietveld refinement of MXene synthesized via high-temperature reaction of Ti, graphite, and TiCl4 at 950 °C. (C) XRD patterns of delaminated and sonicated MXenes. (Inset) Colloidal dispersion of the delaminated MXene. (D) SEM image and (E) EDX elemental mapping of a MXene stack. (F) High-resolution HAADF image and (G) EELS atomic column mapping showing the layered structure of MXene. Reproduced with permission from (Wang et al., 2023).

Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2017) demonstrated the synthesis of ultrathin tantalum-based MXenes (carbide, nitride, and boride) by heating a tantalum-copper bilayer in the presence of specific precursors tailored to the desired composition. The process involved two immiscible metals, Ta and Cu, heated to 1,077 °C under acetylene, ammonia, or boron atmospheres to enable 2D growth of single-crystal tantalum carbide, nitride, and boride, respectively. This approach not only facilitates the controlled production of MXenes but also enhances their resistance to oxidation and wear.

Several studies have shown that alternative strategies beyond conventional fluorine-based acid etching can be employed to synthesize high-quality MXenes (Li et al., 2019a; Li et al., 2018; Pang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2026). These include alkali treatment (Li et al., 2018; Urbankowski et al., 2016), electrochemical methods (Pang et al., 2019), and the Lewis acid molten salt approach (Li et al., 2019a; Li et al., 2020). Materials produced through these techniques exhibit tunable surface chemistry, excellent optical characteristics, and outstanding electrical conductivity and mechanical strength. A recent study introduced a fluorine-free etching strategy for MXene synthesis, enabling simultaneous removal of the A-site element and in situ elemental functionalization (Ma et al., 2026). In this method, MAX phase Ti3AlC2 was mixed with tellurium powder in a 1:3 stoichiometric ratio using ethanol as a dispersant, followed by solvent evaporation. The mixture was then heated to 700 °C for 1 h and cooled to room temperature. Subsequent washing with 1 M HCl removed residual impurities, followed by rinsing with deionized water and drying to yield Te-functionalized MXenes. This approach successfully produced Te-modified MXenes, including Ti3C2Tex, V2CTex, Ti2CTex, and Nb2CTex, demonstrating a controllable, scalable, and straightforward route for synthesizing diverse MXenes without relying on conventional etching processes.

It can be noticed that recent advancements in MXene synthesis have focused on simplifying production processes and reducing toxicity, aiming to make these materials safer and more environmentally friendly. Innovative synthetic approaches have been developed to produce high-quality MXenes that retain their intrinsic properties while minimizing negative environmental impacts. These improvements support the integration of MXenes into the design and development of wearable sensing devices, where material performance and safety are critical. However, despite these promising developments, challenges related to scalability, process consistency, and reproducibility remain. Addressing these issues is essential to ensure reliable large-scale production and to fully realize the potential of MXenes in practical, real-world applications.

2.3 Environmental impacts and concerns of MXene synthesis

Although numerous studies have explored the synthesis of MXenes for a wide range of applications, there remains a significant gap in research concerning the scalability of these materials. On the other hand, the use of harsh chemicals and high temperatures are also issues that need to be resolved. These pose concerns with regard health and safety risks. For instance, traditionally strong acids such as HF are preferred to, etch A layer from MAX and produce MXenes. HF is a highly corrosive and toxic that pose risk to human and environment. The high energy used also contributes to increase in overall MXene production costs as well as adverse effects on the environment. For instance, Dadashi Firouzjaei et al. (2023) conducted a life-cycle assessment (LCA) focusing on the cumulative energy demand (CED) and environmental impacts associated with the lab-scale synthesis of Ti3C2Tx MXene. The study compared the environmental footprint of MXene production at both Gram and kilogram scales with that of commonly used electromagnetic shielding materials such as aluminium and copper. The findings revealed that electricity consumption accounted for approximately 70% of the total environmental impact. Specifically, the production of 1 kg of aluminium and copper resulted in 23 kg and 8.8 kg of CO2 emissions, respectively, whereas synthesizing 1 kg of MXene released a significantly higher amount, i.e., 428 kg of CO2. The study concluded that chemical usage had a relatively lower environmental impact compared to energy consumption, suggesting that the adoption of renewable energy sources in the synthesis process could substantially improve the sustainability of MXene production. These gaps highlight the need for further investigation into alternative synthesis methods that are not only more environmentally friendly but also scalable for industrial applications. Advancing such methods could pave the way for broader adoption of MXenes in sustainable technologies.

2.4 Properties of MXenes

The properties of MXenes are strongly influenced by their composition, stacking sequence, and lateral dimensions (Pan et al., 2025). These materials exhibit unique characteristics, such as distinctive morphology, versatile surface chemistry, excellent electrical conductivity, and biocompatibility, making them ideal platforms for advanced sensor development (Pan et al., 2025; Feng et al., 2025). Understanding their structure is therefore essential, as MXenes are primarily derived from MAX phases by selectively etching out the A element. Common structures include M2X, M3X2, and M4X3 (Gogotsi and Anasori, 2019). Due to the weaker metallic M–A bonds compared to the strong covalent M–X bonds, selective etchants can effectively remove the A layer, exposing the transition metal surface. This surface is readily terminated with electronegative groups such as–F, –OH, and–O, which impart hydrophilicity and enable strong interactions with water and various semiconductors in aqueous systems.

2.4.1 Stability of MXenes

MXenes are highly susceptible to oxidation, which can lead to their transformation into oxides in the presence of heat (Naguib et al., 2014). For instance, Ti3C2Tx has been shown to convert into TiO2 and carbon sheets after annealing at 1,150 °C in air for just 30 s (Naguib et al., 2014). As illustrated in Figure 3A, the as-prepared MXene exhibited an exfoliated layered structure, while flash oxidation for 30 s resulted in nanocrystal growth between and along the layer edges (Figure 3B). TEM images further revealed nanocrystals embedded within thin sheets (Figure 3C). Raman, EDX, and EDS analyses confirmed the presence of Ti and O, along with amorphous carbon. These findings highlight the vulnerability of MXenes in oxidative environments, despite their stability under inert conditions at temperatures up to 1,200 °C (Wang et al., 2016). Additionally, MXenes can readily oxidize in aqueous media containing dissolved oxygen, forming titanium hydroxide (Mashtalir et al., 2014). Given that wearable sensors typically operate at body-safe temperatures not exceeding 45 °C, as higher temperatures can pose serious health risks such as brain damage, and the degradation temperatures of MXenes are significantly higher than those encountered in practical applications (Suchard, 2007). To improve stability and wearability, a variety of polymers such as polyurethane (PU), thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) have been employed as supporting materials (Shao et al., 2024). These polymers are lightweight, flexible, and easy to process, and they serve to protect MXenes from environmental degradation, thereby enhancing the overall performance and durability of wearable sensor devices.

FIGURE 3

Characterization of MXene Before and After Flash Oxidation: (A) SEM image of a typical multilayered as-synthesized MXene. (B) SEM image after flash oxidation, with inset showing a different region. (C) TEM image of oxidized MXene, with inset highlighting high-resolution anatase nanocrystals embedded within amorphous carbon. Images reproduced with permission from (Naguib et al., 2014).

2.4.2 Mechanical and electrical properties of MXenes

The mechanical and electrical properties of MXenes have been extensively studied through theoretical and experimental approaches. Density functional theory (DFT) predicts that 2D transition metal carbides exhibit high in-plane stiffness and excellent electrical conductivity (Kurtoglu et al., 2012). Classical molecular dynamics simulations by Borysiuk et al. (2015) estimated tensile moduli of 502 GPa, 597 GPa, and 534 GPa for Ti3C2, Ti2C, and Ti4C3, respectively, with modulus strongly dependent on layer thickness. Failure mechanisms varied: thinner Ti2C and Ti3C2 fractured from the edges inward, accompanied by folding and crumpling, whereas thicker Ti4C3 developed central cracks under stress. Examples of the experimental data obtained by various researchers are tabulated in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Formulation | Preparation methods | Thickness (µm) | MXene content | Mechanical strength (MPa) | Electrical conductivity (S cm-1) | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti3C2Tx | Blade coating | 0.2 | 100 | - | 15100 ± 160 | By adjusting the film thickness, it is possible to achieve tailored mechanical and electrical properties, allowing for the customization of MXene-based materials to meet specific performance requirements in various applications | Zhang et al. (2023) |

| 0.9 | | 568 24 | 13200 ± 130 | ||||

| 2.4 | | 480 35 | 10500 ± 240 | | |||

| Ti3C2Tx | HCl treated followed by Vacuum | 6–8 | | 112 | 10400 | Acid treatment enhances the interlayer interactions between MXene sheets, resulting in superior mechanical and electrical properties due to more efficient stress transfer and improved structural cohesion | Chen et al. (2020) |

| 10 | 4,620 | ||||||

| Ti3C2Tx | Vacuum-assisted filtration | | | | 4,600 ± 1,100 | Eliminating the sonication-based delamination step during MXene synthesis has been shown to yield high-quality MXene, resulting in enhanced material properties. This streamlined approach reduces structural damage and preserves the integrity of the MXene flakes, contributing to improved performance | Lipatov et al. (2016) |

| Ti3C2Tx | Vacuum filtration | 1 | 100 | - | 14000 | Careful control of nitrogen flow during the etching process has been shown to significantly enhance the quality of MXene, resulting in exceptional electrical conductivity due to reduced defects and improved structural integrity | Mirkhani et al. (2019) |

| Ti3C2Tx | Vacuum assisted filtration | 6 | 100 | - | 5,857 ± 680 | Introducing nitrogen bubbling during the etching process has been shown to produce high-quality MXene, which in turn enhances its electrical conductivity. This approach helps control the etching environment, contributing to better structural integrity and fewer defects in the resulting material | Jolly et al. (2021) |

| Ti3AlC2 | Vacuum filtration | - | - | - | 4.5 ×106 | Using graphite, rutile, and aluminium powders as precursors has been shown to yield MXenes of comparable quality to those synthesized from Ti3AlC2, with the choice of precursor playing a significant role in determining the final material properties | Li et al. (2016) |

| Ti3C2Tx | | 2.6 × 106 | |||||

| PVA/Ti3C2Tx | Vacuum filtration | 3.9 | 90 | 30 | 224 | The strong interaction between polymer PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) and MXene is primarily facilitated by the presence of hydroxyl groups, which promote effective bonding at the interface. This enhanced interaction leads to improved mechanical performance, as it enables more efficient stress transfer between the polymer matrix and the MXene filler | Ling et al. (2014) |

| Ti3C2Tx/Metal porphyrin frameworks | | 16–29 | 50–89 | | 10–1,238 | Hydrogen bonding between MXene flakes and 2D metal-porphyrin frameworks effectively mitigates the issue of restacking, promoting better dispersion and structural stability and thus better properties | Zhao et al. (2019) |

| Ti3C2Tx/Cellulose nanofibers | Vacuum filtration | 20 | - | 0.64–89.5 | 52–1990 Sm-1 | Mechanical treatment of MXene and cellulose enhances the exfoliation of MXene sheets, allowing for better dispersion within the matrix. This process facilitates the formation of a homogeneous and well-aligned structure, which in turn leads to improved material properties, particularly in terms of mechanical performance and electrical properties. These properties can be controlled through number of milling as well as the griding clearance | Feng et al. (2022) |

| MXene/PVA | Solution casting | | | 37–112 | 71–428 Sm-1 | Wet mechanical grinding facilitates the exfoliation of MXene into single or few-layer sheets, which can be uniformly dispersed within the PVA matrix. This process promotes the formation of an orderly assembled MXene structure within the polymer, significantly enhancing both mechanical and electrical properties of the resulting composite material | Yi et al. (2022) |

| Ti3C2Tx/Cellulose nanofibers | Vacuum-assisted filtration followed by vacuum pressing | 6–50 | 20–95 | 53–340 | 1.12 × 105 S m−1–2.95 × 104 S m−1 | The effective dispersion of MXene and its strong interfacial interaction with cellulose nanofibers play a crucial role in enhancing both mechanical and electrical properties of the composite material. These interactions facilitate better stress transfer and uniform distribution, contributing to improved structural integrity and functional performance | Tian et al. (2019) |

| PVA/Ti3C2Tx/Montmorillonite | Layer-by-layer | 2.7–8.2 | 45.5 | 138–225 | 0.53–1.25 | By fine-tuning the thickness of MXene-based films, it is possible to tailor their mechanical and electrical properties to meet specific application requirements. This level of control enables the design of materials with optimized performance for targeted uses, such as flexible electronics and wearable sensors | Lipton et al. (2019) |

Summary of selected studies of electrical and mechanical properties of MXenes.

The quality of MXenes, which is strongly influenced by both the synthesis method and the source material, plays a critical role in determining their mechanical and electrical properties (Mirkhani et al., 2019). Higher-quality MXenes, those with fewer structural defects, exhibit superior properties (Mirkhani et al., 2019). Therefore, careful consideration of the synthesis route and precursor quality is essential. For example, the minimally invasive layer delamination (MILD) method, using in situ HF without a separate delamination step and under nitrogen flow during etching, produced high-quality MXene, resulting in enhanced electrical conductivity (Mirkhani et al., 2019). This method has minimal impact on the intrinsic properties of MXene, as it introduces fewer defects on the MXene sheets Additionally, post-etching treatments can significantly affect the final properties of MXenes by influencing the intrinsic interactions between individual sheets (Jolly et al., 2021).

The method used to fabricate MXene films also impacts their performance. For example, the introduction of a non-reactive acid has been shown to induce planar stacking of MXene layers, resulting in enhanced mechanical and electrical properties (Jolly et al., 2021) (see Table 1). Furthermore, films produced via blade coating demonstrated markedly better mechanical strength compared to those prepared by vacuum filtration, even when using flakes of the same size. Notably, blade-coated films achieved a tensile strength of approximately 568 MPa, which is 15 times higher than that of vacuum-filtered films (∼40 MPa), as tabulated in Table 1.

Polymer reinforcement significantly enhances MXene mechanical performance (Zhao et al., 2019). For example, Ti3C2Tx films exhibit ∼22 MPa tensile strength and ∼3.52 GPa modulus, which increase to ∼91 MPa and ∼4% elongation-at-break with PVA incorporation. Rolled Ti3C2Tx cylinders supported loads up to 4,000× their weight (∼1.3 MPa), rising to 15000× (∼2.9 MPa) with 90% PVA. Electrical conductivity (∼240 S/m for pristine MXene) decreases with polymer content, dropping from 22 S/m to ∼0.04 S/m as MXene loading decreases. In general, improvements in the mechanical performance of MXene-based materials are largely attributed to enhanced interactions between MXene sheets, which are often promoted by the incorporation of secondary materials. These interactions help mitigate issues such as sheet restacking and contribute to better structural integrity and functional performance. Table 1 summarizes selected studies in which MXenes were integrated into other material systems to enhance their properties, demonstrating their potential in diverse applications ranging from wearable sensors to biomedical devices (Ling et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2022; Yi et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2019; Lipton et al., 2019).

Surface terminations critically influence electronic properties (Naguib et al., 2023). Theoretical studies show that -F and -OH groups can convert Ti3C2 from metallic to semiconducting (Naguib et al., 2023; Khazaei et al., 2013), and their spatial arrangement further modulates conductivity (Tang et al., 2012). Strategies such as annealing to remove surface groups and controlling exfoliation/intercalation (e.g., H2O, TBA+) offer additional tuning of MXene electronic behaviour (Wang et al., 2020; Hart et al., 2019). Like mechanical properties, the electrical conductivity of MXenes is significantly influenced by factors, such as material quality, film thickness, and the fabrication method (Lipatov et al., 2016). The highest reported electrical conductivity of approximately 15,000 S cm-1 was achieved using blade coating, a scalable technique that offers advantages over traditional methods such as vacuum filtration, spin-casting, solution casting and spray-coating (Zhang et al., 2023). Additionally, acid treatment has been shown to enhance electrical conductivity compared to untreated MXene films (Chen et al., 2020). These improvements are largely attributed to how these parameters affect the interactions between MXene sheets. This underscores the importance of carefully controlling any factor that influences interlayer interactions to optimize electrical performance. Moreover, defects introduced during synthesis play a critical role in determining the final properties of MXene-based materials. Excessive defects can significantly degrade performance, making it essential to select synthesis methods that minimize structural imperfections in the resulting MXene sheets.

2.4.3 Strategies for controlling the termination groups on the surface of MXenes

MXenes have highly adjustable surface chemistries, with–O, –OH, and–F being the most common terminations introduced during the selective etching of MAX phases (Khanal and Irle, 2023). Controlling these termination groups can be achieved through several methods. Etching conditions, such as the choice of etchant, concentration, temperature, and duration, significantly influence the proportions of each termination (Tang et al., 2022; Mozafari and Soroush, 2021). Milder approaches like LiF/HCl tend to reduce excessive–F coverage compared to direct HF etching (Mozafari and Soroush, 2021). Fluoride-free techniques, such as molten-salt etching, allow for the synthesis of MXenes mainly terminated with–O and halide groups, which offer improved electrical and chemical properties (Kruger et al., 2024). Post-treatment methods, including thermal annealing, remove volatile groups like–F and–OH, stabilizing more desirable–O terminations (Rau and Lu, 2025). Chemical substitution with nucleophilic reagents or halide salts further enables selective replacement of surface groups, while electrochemical treatments can dynamically adjust–O/–OH ratios through surface redox reactions (Tang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). These termination groups are fundamental in defining MXene performance in sensing applications. –O terminations enhance chemical stability and provide strong surface binding sites; –OH terminations offer better electrical conductivity, hydrophilicity, and functionalization potential; conversely, high levels of–F termination usually impede conductivity and ion access, making them generally undesirable for chemiresistive or electrochemical sensors (Rems et al., 2024; Mehdi Aghaei et al., 2021; Cai and Kim, 2025). In practice, most MXenes display mixed terminations, which yield averaged properties but can cause variability, making control over termination crucial for reproducible and optimized sensor performance. Table 2 lists the different MXene termination groups, their key properties and their effect in sensing performance.

TABLE 2

| Termination group |

Key properties | Effect on sensing performance |

|---|---|---|

| –O | High chemical stability; strong binding sites; moderate conductivity (Khanal and Irle, 2023; Rau and Lu, 2025) | Enhances sensor durability and stability; improves binding with analytes and functional molecules |

| –OH | Highest conductivity among common terminations; hydrophilic; reactive surface sites; lowers work function (Khanal and Irle, 2023) | Improves electrical signal strength; facilitates surface functionalization; enhances sensitivity and charge transfer |

| –F | Low conductivity; reduced ion accessibility; hydrophobic (Khanal and Irle, 2023; Zhang et al., 2022) | Generally undesirable for chemiresistive/electrochemical sensors due to poor charge transport, but may aid hydrophobic analyte selectivity |

| Mixed (–O/–OH/–F) | Most realistic state; averaged electronic and chemical behaviour (Ibragimova et al., 2019) | Offers balanced properties but may introduce batch-to-batch variations; optimization is important for reproducibility |

| Halides (Cl, Br, I) | Unique electronic effects; improved interlayer spacing; moderate stability (Zhang et al., 2022) | Useful for tailoring work function, tunable interlayer spacing, and potential selectivity improvements in gas sensing |

Effect of MXenes termination groups on the sensing performance.

3 MXene-based wearable sensor for health monitoring

The growing demand for innovative diagnostic tools, particularly those that are accessible, user-friendly, and suitable for decentralized healthcare settings, has driven the development of biosensors (Turner, 2013; Yan et al., 2022). These personalized sensing devices empower individuals, whether patients or healthy users, to monitor health conditions, enable early disease detection, and maintain overall wellness. A deeper understanding of the material science and biological interactions of MXenes and their composites presents a valuable opportunity to develop technologies with strong potential for clinical translation. As previously mentioned, MXenes possess a unique combination of properties that make them highly suitable for advancing a wide range of sensing platforms aimed at health monitoring. These properties include tunable surface chemistry, excellent electrical conductivity, biocompatibility, and distinctive morphologies. Table 3 provides a summary of recent advancements in the development of wearable sensors for health monitoring applications (Rakhi et al., 2016; Myndrul et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Zahed et al., 2022; Alanazi et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023).

TABLE 3

| Pathway | MXene | Etchant | Composition | Biomarker | Linear range | Sensitivity | Detection limit | Sensor technology | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | Ti3C2 | | Ni/Samarium-modified Ti3C2 | | 00.1–0.1 mM | 1,673.54 μA mM−1 | 0.24 µM | Non-enzymatic | Gilnezhad et al. (2023) |

| | | | | | 0.25–7.5 mM | 1,519.09 μA mM−1 | | | |

| Skin perspiration | Ti3C2Tx | LiF/HCl | MXene/Pt | Glucose | 0–1 mM | 3.43 μA mM–1 cm–2 | 29.15 µmolL-1 | Non-enzymatic Electrochemical | Li et al. (2023) |

| - | - | HF | MXene/rGO/CuO2 aerogel | Glucose | 0.1–14 mM | 264.521 μA cm–2 mM–1 | 1.1 µm | Non-enzymatic Electrochemical | Alanazi et al. (2023) |

| - | 15–40 mM | 137.95 μA cm–2 mM–1 | |||||||

| Skin perspiration | NiCo2O4/Ti2NbC2 | HF | NiCo2O4/Ti2NbC2 | Glucose | 0.02–1.0 mM | 425.6 μA mM−1cm−2 | 0.298 mM | Non-enzymatic | Subramania et al. (2023) |

| Skin perspiration | Ti3C2Tx | LiF/HCl | PtNPs/Nanoporous carbon (NPC)@MXene | Glucose | 0.003–1.5 mM | 100.85 μA mM–1 cm–2 | 7 µm | Enzymatic electrochemical | Zahed et al. (2022) |

| 0.003–21 mM | 82.68 μA mM–1 cm–2 | ||||||||

| | Ti3C2Tx | HF | Gox/MXene | Glucose | 0.1–10 mM | 93.75 μA mM–1 cm–2 | 12.1 µM | Enzymatic | Huang et al. (2022) |

| Skin perspiration | Ti3C2Tx | LiF/HCl | ZnO tretrapods/MXene/GOx | Glucose | 0.05–0.7 mM | 29.88 ± 2.4 μA mM−1 cm−2 | 21 ± 1.1 μM | Enzymatic | Myndrul et al. (2022) |

| Skin perspiration | Ti3C2Tx | HF | GOx/Au/MXene/Nafion | | 0.1–18 mM | 4.2 μAmM−1 cm−2 | 5.9 μM | Enzymatic | Rakhi et al. (2016) |

| Skin perspiration | Ti3C2Tx | HF | MXene/PU | Lactate | 0.001–50 mM | 2.5 μA mM-1 | - | Enzymatic Electrochemical |

Xiao et al. (2025) |

| Skin perspiration | Ti3C2Tx | LiF/HCl | CNTs/Ti3C2Tx/PB/CFMs | Lactate | 0 × 10−3 M - 22 × 10−3 M | 11.4 μA mm−1 cm−2) | 0.67 × 10−6 M | Enzymatic Electrochemical |

Lei et al. (2019b) |

| Physiological signals/Remote respiration | Ti3C2Tx | LiF/HCl | MTP | Respiratory rates | | 509.5 kPa-1 | ̴1 Pa | Piezoresistive | Yang et al. (2021) |

Comparison of MXene-based sensors developed for health monitoring applications.

3.1 Body fluid-based sensing devices

Among emerging technologies, wearable electrochemical sensors have gained attention as non-invasive tools that utilize body fluids such as saliva, sweat, and tears to provide real-time metabolic feedback (Tricoli et al., 2017). However, these devices still face several challenges, such as instability of biomolecules and enzymes during repeated use, narrow detection ranges, limited sensitivity, and reduced durability. These limitations have prompted researchers to explore novel materials, such as MXenes to enhance sensor performance. The incorporation of MXenes plays a vital role in enhancing both the electrical conductivity and hydrophilicity of the sensor. Improved conductivity significantly enhances the electron transport rate, which in turn contributes to the overall enhanced performance of the sensing device.

In a notable study, Lei et al. (2019a) demonstrated the integration of MXene nanosheets with Prussian blue to create a biosensor capable of detecting biomarkers in sweat, including glucose and lactate. The sensor featured a working electrode composed of MXene and Prussian blue on a hydrophobic substrate, forming a solid/liquid/air interface. The superhydrophobic carbon-based three-phase interface significantly improved the performance of the device and stability by protecting internal connectors from corrosion. The biosensor exhibited high sensitivities of approximately 35 μA mm-1·cm-2 for glucose and 11 μA mm-1·cm-2 for lactate, along with excellent repeatability. These results highlight the role of MXene nanosheets in enhancing the overall functionality of enzymatic wearable devices, marking a significant step toward the realization of personalized health monitoring technologies.

Inal and associates (Lei et al., 2019b) designed disposable glucose sensor using nitrogen-doped laser-scribed graphene (N-LSG) by mixing MXene and Prussian blue, as illustrated in Figure 4. The N-LSG was produced using lignin as a precursor, which was processed via CO2 laser scribing to create a porous, binder-free, hierarchical, and highly conductive graphene electrode. This structure exhibited excellent electrochemical activity and a high heterogeneous electron transfer rate, resulting in a conductivity of 2.3 Ω/sq. The prepared electrode was functionalized with a MXene/PB composite through a spray-coating technique, followed by the immobilization of catalytic enzymes specific to glucose, lactate, and alcohol. The MXene/PB composite demonstrated superior sensing performance compared to carbon nanotube/PB and graphene/PB systems, attributed to its distinct morphology and exceptional conductivity. For glucose detection, the sensor was modified with glucose oxidase (GOx), which significantly improved its selectivity and sensitivity. It achieved a linear detection range from 10 µM to 5.3 mM, with a detection limit of 0.3 µM and a sensitivity of 49 μA mM-1·cm-2. For lactate sensing, the electrode was functionalized with lactate oxidase, yielding a linear range of 0–20 mM, a detection limit of 0.5 µM, and a sensitivity of approximately 22 μA mM-1·cm-2. In the case of alcohol detection, alcohol oxidase was used, resulting in a sensitivity of ∼6.0 μA mM-1·cm-2 across a linear range of 0–50 mM.

FIGURE 4

Schematic illustration of the direct-write laser scribing process. (i) Deposition of a lignin-PVA-urea film onto a substrate using the doctor blading technique. (ii) Laser scribing to fabricate nitrogen-doped laser-scribed graphene (N-LSG). (iii) Pattern formation of the laser-scribed N-LSG electrodes. (iv) Functionalization of the electrodes with MXene/Prussian Blue via spray coating. (v) Removal of uncarbonized film using a water lift-off method. (vi) Immobilization of specific enzymes onto the electrode surface. Reproduced with permission from (Lei et al., 2019b).

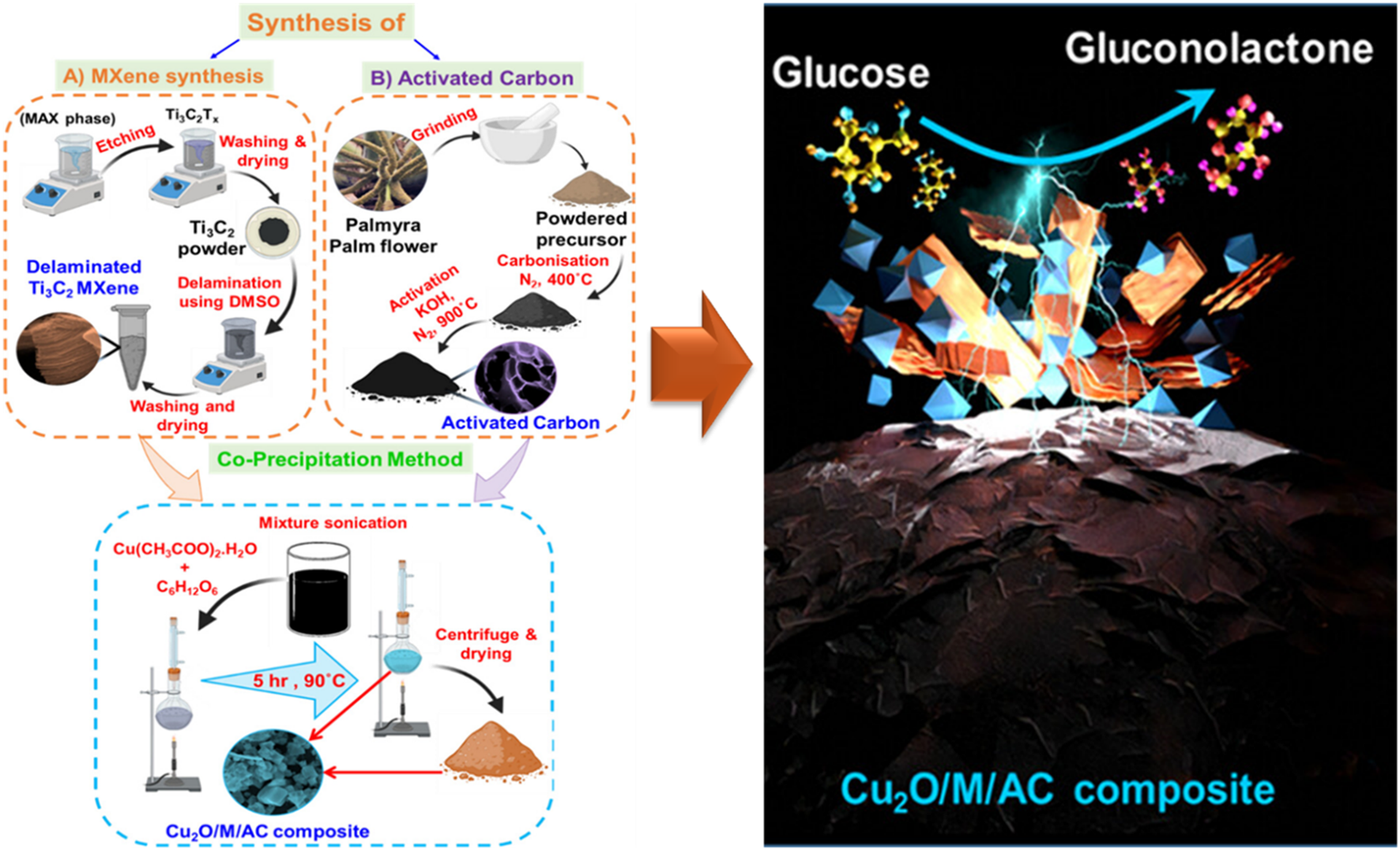

While enzyme-based sensors for glucose detection offer excellent electrochemical responses and high selectivity, they are often associated with high analytical costs (Li et al., 2019b). This is primarily due to the sensitivity of enzyme activity to environmental factors such as pH and temperature. As a result, there has been growing interest in developing non-enzymatic sensors to address the limitations of enzyme-based systems. In one study, few-layered Ti3C2 MXene was synthesized via HF etching at room temperature, followed by exfoliation using DMSO, to serve as the foundation for a non-enzymatic glucose sensor (Li et al., 2019b). The researchers introduced Nickel-Cobalt layered double hydroxide (NiCo-LDH) nanosheets onto the MXene surface through an in situ hydrothermal method, forming a 3D porous composite. This structure exhibited a high electron transfer rate and a large surface area, which significantly improved the performance of the sensor in terms of selectivity, reproducibility, and stability. The sensor demonstrated a wide linear detection range from 0.002 mM to 4.096 mM, with a detection limit of 0.53 µM, sensitivity of ∼65 µAmM-3cm-2 and a rapid response time of less than 3 s. The enhanced performance was attributed to the synergistic effect between MXene and NiCo-LDH, which provided a large active surface, efficient electron transport, and facilitated electrolyte diffusion, thereby boosting overall conductivity. This indicates such materials can be used as a foundation for developing sensors that can be used in wearable for continuous monitoring for disease control. Selvi Gopal et al. (2024) also synthesized Ti3C2Tx MXene via HF etching, followed by DMSO-assisted exfoliation, for use in a non-enzymatic glucose sensor. In this study, a composite comprising MXene, activated carbon, and CuO was developed and evaluated for glucose sensing, as illustrated in Figure 5. The resulting sensor demonstrated impressive performance, with a detection limit of 1.96 µM, and sensitivities of approximately 430 μA cm-2 within the range of 0.0004–13.3 mM, and 241 μA cm-2 for the range 15.3–28.4 mM. The sensor was also successfully applied for real-time analysis of serum samples, achieving a recovery rate of ∼99%. The enhanced performance was attributed to the abundance of active sites for glucose adsorption and oxidation, which resulted from both the materials used and the fabrication approach. The synergistic interaction between activated carbon and MXene contributed to exceptional hydrophilicity, conductivity, and a large surface area. Additionally, the porous structure of activated carbon facilitated the formation of CuO nanoparticles on the composite surface, leading to a heterostructure material that promoted rapid electron transfer between the electrode and electrolyte during glucose oxidation.

FIGURE 5

Schematic illustration of the synthesis process for CuO2 nanoparticles/MXene/activated carbon composite for glucose sensing applications. Reproduced with permission from (Selvi Gopal et al., 2024).

Li et al. (2023) developed a flexible, wearable, non-enzymatic glucose sensor designed for sweat-based monitoring. In their approach, Ti3C2Tx MXene was synthesized using in situ HF, generated from a mixture of LiF and HCl as the etchant, followed by hybridization with Pt nanoparticles. This hybridization resulted in a highly active catalyst with a wide linear glucose detection range of 0–8 mmol L-1. To optimize the performance of the sensor, it was integrated with a microfluidic patch for efficient collection of sweat. The final device successfully tracked glucose fluctuations in response to energy consumption and replenishment. In vivo testing demonstrated the potential of the sensor for continuous glucose monitoring, which is essential for effective treatment and management of glucose-related conditions.

3.2 Skin-based monitoring devices

Flexible, skin-adherent wearable sensors have gained significant attention in recent years due to their potential in continuous healthcare monitoring (Yan et al., 2022; Li et al., 2019b; Selvi Gopal et al., 2024). These devices offer durability, stability, and reliability, which are essential as society increasingly relies on technology for real-time health insights. Capable of recording high-quality electrophysiological signals, such as electrocardiograms (ECG), electromyograms (EMG), electrooculograms (EOG), and electroencephalograms (EEG), over extended periods and under challenging conditions, these sensors play a vital role in diagnosing and managing cardiac, neurological, and muscular disorders, as well as assessing skin impedance and hydration levels. Key challenges in real-time health monitoring include ensuring signal accuracy, minimizing motion artifacts, and maintaining long-term stability in various environments, including water-rich conditions. These challenges have driven research into advanced electrophysiological electrodes, such as electronic tattoos (Yan et al., 2022; Nawrocki et al., 2016; Nawrocki et al., 2018; Ershad et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Kabiri Ameri et al., 2017) designed for direct skin application. Among these, ultrathin flexible electrodes have garnered particular interest due to their intimate skin contact, which enhances mechanical and electrical stability and enables prolonged, high-fidelity signal acquisition.

Driscoll et al. (2021) demonstrated the development of flexible multichannel electrode arrays using Ti3C2 MXene as the foundational material. These electrodes were designed in a planar configuration for direct application to human skin, enabling electroencephalography for brain activity monitoring, electromyography (EMG) for muscle activity, electrocardiography (ECG) for heart monitoring, and electrooculography (EOG) for tracking eye movement. The fabrication process involved laser patterning on a porous substrate, followed by infusion with Ti3C2 ink, and encapsulation with flexible elastomeric films. The presence of MXene contributed significantly to the bioelectronic performance, offering low impedance and exceptional charge delivery, which are critical for high-resolution sensing. These properties helped overcome limitations typically associated with gel-free epidermal electrodes. Furthermore, the electrodes exhibited high charge storage capacity (CSC) and charge injection capacity (CIC), indicating their potential as efficient stimulation electrodes with enhanced charge transfer and lower power consumption. Such devices show strong promise for use in clinical applications, particularly in epidermal sensing and neuromodulation, and represent a significant advancement in healthcare diagnostics, monitoring, and therapeutic technologies.

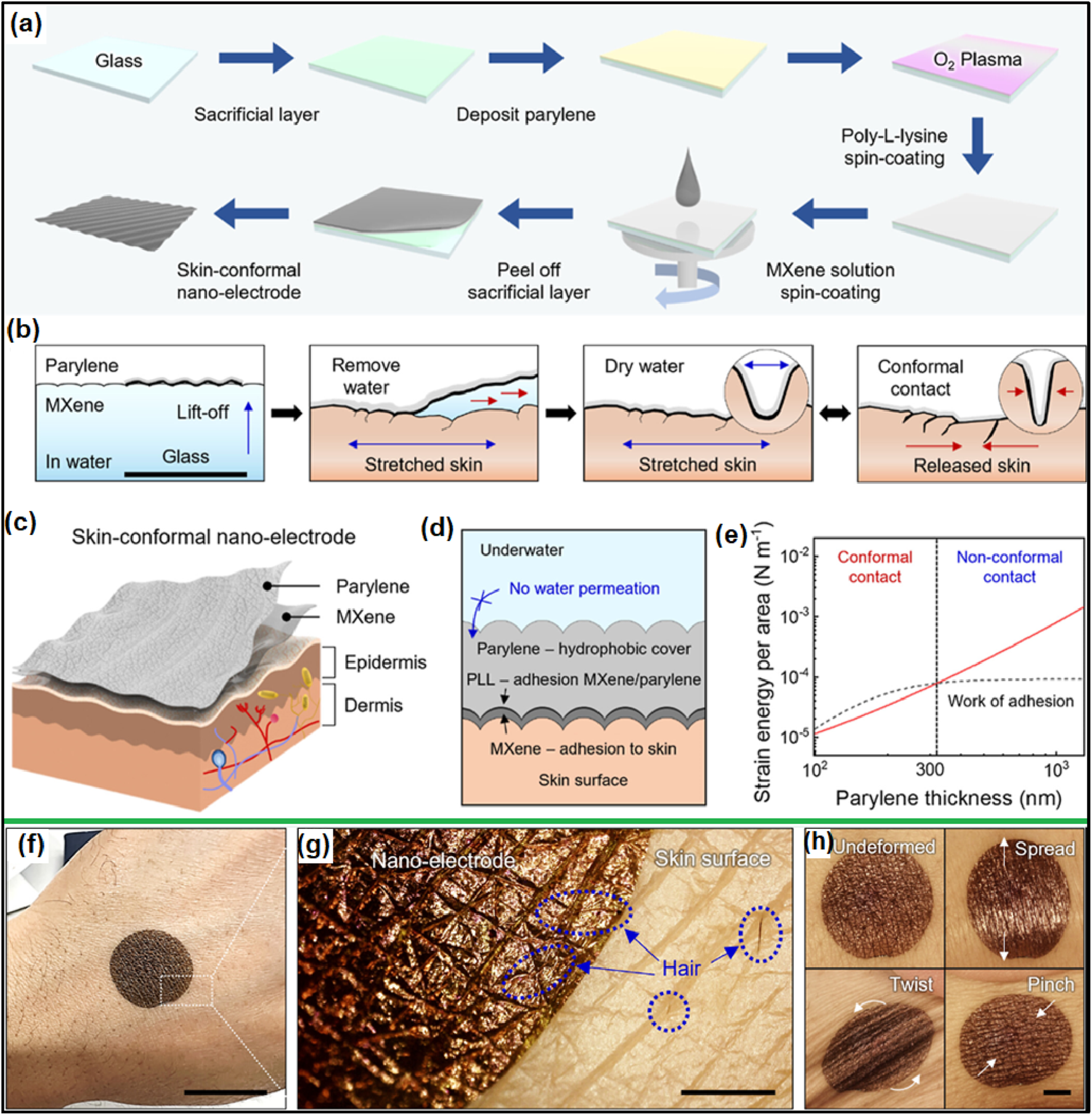

Kim et al. (2025) reported the development of a skin-conformal nano-electrode composed of Ti3C2Tx, a poly-L-lysine adhesive layer, and an ultrathin crosslinked parylene film. The fabrication process involved depositing a sacrificial layer on a glass substrate, followed by CVD of parylene, spin-coating of MXene, and peeling off the ultrathin electrode. As shown in Figure 6, the electrode adhered seamlessly to the skin and remained stable under typical skin deformations such as stretching, pinching, and twisting, ensuring consistent signal acquisition with minimal motion artifacts. The electrode exhibited a flexural rigidity of 2.1 × 10−12 Nm, significantly lower than human skin (3.8 × 10−5 Nm), which is critical for conformal contact with the skin’s natural topography. Its water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) of 3.3 mg cm-2·h-1 was comparable to medical-grade dressings, and cytotoxicity tests showed 94% cell viability after 6 days, indicating excellent comfort and suitability for prolonged wear. Electrically, the electrode achieved low skin interfacial impedance in the 20–100 kHz range, with a value of 32.3 kΩ at 100 kHz, and maintained impedance stability over 4 hours due to its high conformability. Underwater testing confirmed stable impedance in both air and submerged conditions, attributed to the dual hydrophobic/hydrophilic nature of the parylene and MXene layers, which ensured robust skin-electrode interface performance. Mechanical durability was demonstrated through 5,000 bending cycles, resulting in only a 1% change in relative resistance. The electrode also showed a high signal-to-noise ratio, low baseline noise, and strong resistance to motion artifacts in demanding environments such as saunas and pools. Furthermore, it enabled simultaneous EMG and ECG monitoring with high stability and accurate detection of complex muscle activities. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of the MXene-based nano-electrode as a sustainable, long-term bioelectronic platform for continuous mobility monitoring and real-time healthcare diagnostics.

FIGURE 6

(a) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process for the skin-conformal nano-electrode: (i) Deposition of a sacrificial layer onto a clean glass substrate. (ii) Formation of a parylene substrate via chemical vapor deposition (CVD), creating the desired structural layer. (iii) Surface treatment using oxygen plasma to enhance adhesion. (iv) Sequential spin-coating of poly-L-lysine (PLL) and MXene onto the treated substrate. (v) Peeling off the nano-electrode, followed by dissolution of the sacrificial layer in water to release the flexible electrode. (b) Schematic representation of the electrode transfer process onto human skin. (c) Illustration of the skin-conformal nature of the electrode, highlighting its adaptability to skin topography. (d) Depiction of the water-resistant properties of the electrode, enabled by its dual hydrophilic/hydrophobic interface. (e) Evaluation of the optimal parylene thickness required for conformal contact, as a function of electrode thickness and the skin’s work of adhesion. (f) Pictures of the skin-conformal nanoelectrodes applied to human skin. (g) An enlarged view displying the interface between the skin and the nanoelectrodes. (h) Pictures of the nanoelectrodes under different mechanical deformations, i.e. undeformed, stretched, pinched, and twisted. Reproduced with permission from (Kim et al., 2025).

Zheng et al. (2021) developed a multifunctional textile-based sensor using scalable spray-coating and dip-coating techniques. The used techniques afforded the fabrication of the fabric coated with rGO/MXene. The resulting sensor possessed good flexibility, breathability, hydrophilicity and exceptional electrical conductivity. This sensor was investigated as a suitable product for monitoring human motions including bending fingers, elbow, and knee as well as swallowing. There were significant changes in resistance, resulting in high sensitivity. For instance, the resistance decreased with the finger bending reaching ∼ -86% when the finger was bent from 0° to 90°, indicating that the resultant sensor can be utilized to analyse and monitor human motions as wearable electronic or multifunctional garments for healthcare.

3.3 Other biomedical sensors

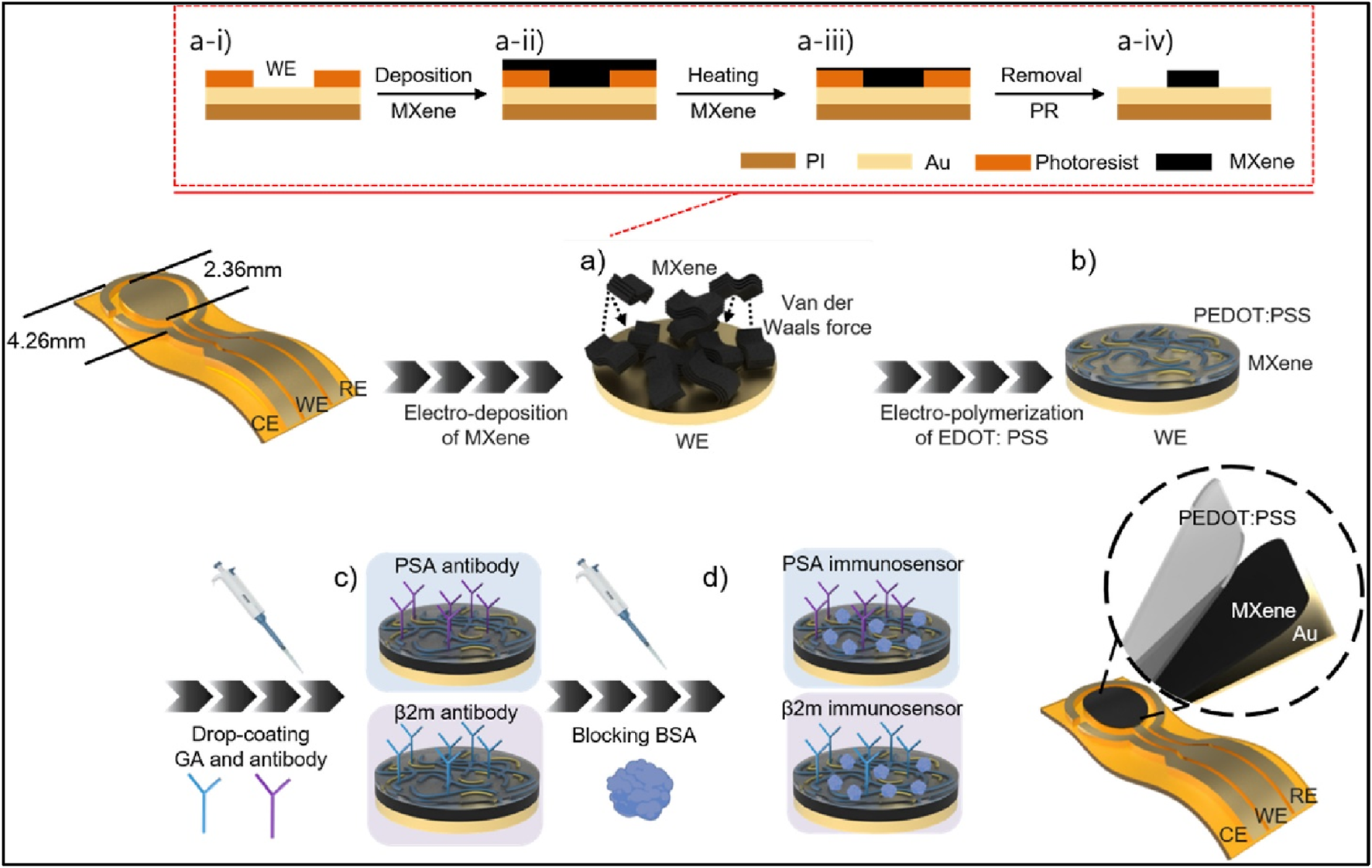

A recent study by Feng et al. (2025) demonstrated that MXene-based composites significantly enhance the specificity of immunosensors for prostate cancer detection. The non-invasive sensor design utilized a gold electrode modified with MXene, followed by electropolymerization of PEDOT:PSS on the MXene surface. This was subsequently functionalized with antibodies, viz. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and β-2-microglobulin (β2m), as illustrated in Figure 7. The resulting electrode exhibited highly sensitive detection capabilities via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, achieving detection limits of approximately 4.96 × 10−5 ng/mL for PSA and 1.1 × 10−4 ng/mL for β2m. A broad linear detection range of 0.001–600 ng/mL was observed for both biomarkers in urine samples. The sensor demonstrated excellent selectivity, reproducibility, and stability, effectively distinguishing between prostate cancer (PCa) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), underscoring its potential for real-world clinical applications. Thermal treatment post-MXene deposition was found to enhance the mechanical stability and adhesion of the sensing layer. Moreover, the MXene/PEDOT:PSS interface contributed to improved conductivity and increased surface area for antibody immobilization, further supporting the sensor’s practical utility. These findings highlight the promise of MXene-based platforms in developing reliable, accurate, and non-invasive tools for early prostate cancer diagnosis. Elsewhere, a photoelectrochemical sensor was developed by hybridizing MXene with Ag2S as photoactive materials (Huang et al., 2023). This hybrid structure exhibited a broad light absorption range and generated a strong photocurrent signal. The sensor demonstrated excellent specificity and stability, achieving an impressive detection limit of 34 a.m. for miRNA-141, which highlights its potential for early and highly sensitive disease diagnostics. To further enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of MXene-based sensing devices for cancer diagnostics, researchers developed a heterostructure composed of TiO2/MXene/CdS as a photoelectrochemical sensing platform for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) detection (Shi et al., 2023). The sensor exhibited a linear increase in photocurrent quenching percentage with CEA concentrations ranging from 1 fg/mL to 10 ng/mL, achieving an impressive detection limit of 0.24 fg/mL. In addition to its high stability, excellent selectivity, and good reproducibility, this device demonstrated strong potential for clinical applications in detecting CEA and other tumour biomarkers. CEA, a glycoprotein tumour marker, is commonly associated with various cancers, including breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, pancreatic, and gastric tumours.

FIGURE 7

(a) Electro-deposition of MXene: (a-i) Patterning of photoresist (PR) to enable selective deposition of MXene. (a-ii) Electro-deposition of MXene onto the patterned substrate. (a-iii) Thermal treatment to enhance material properties. (a-iv) Removal of the photoresist to reveal the deposited MXene. (b) Electro-polymerization of EDOT:PSS on the MXene surface. (c) Drop-coating of graphene aerogel (GA) and specific antibodies (PSA and β2m) onto the MXene/EDOT:PSS working electrode. (d) Blocking with bovine serum albumin (BSA) to prevent non-specific binding. Reproduced with permission from (Feng et al., 2025).

Zhang et al. (2021) developed a dual-mode electrochemical sensor by using MXene as an anchoring substrate for CuAu-layered double hydroxide (LDH). The primary objective was to overcome the inherent insulating nature of LDH, which often limits its catalytic performance. Incorporating MXene effectively addressed this challenge by providing high conductivity and facilitating the anchoring of metal ions as well as the nucleation of LDH. This synergistic design resulted in outstanding sensing properties for CEA, including a wide linear detection range of 0.0001–80 ng/mL and an ultra-low detection limit of 33.6 fg/mL using square wave voltammetry. Such improvements highlight the potential of MXene-based composites for highly sensitive and reliable electrochemical biosensing applications.

Zhang et al. (2020) demonstrated the application of an electrochemical sensor for detecting M. tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) by leveraging the conductive properties of Ti3C2 MXene. In their approach, a fragment of 16S rDNA from the M. tuberculosis H37Ra strain served as the biomarker, while peptide nucleic acid (PNA) was employed as the capture probe. Ti3C2 MXene functioned as the signal amplification and transduction material, significantly enhancing sensor performance. The resulting sensor exhibited excellent specificity, enabling detection within 2 hours, with a linear detection range of 108–102 CFU/mL and a detection limit as low as 20 CFU/mL. These advancements highlight the potential of MXene-based technologies to accelerate the development of innovative solutions, including wearable protective clothing integrated with real-time pathogen detection capabilities. In another study by Zhao et al. (2020), they functionalized cellulose fiber nonwoven fabric with Ti3C2Tx MXene to create a multifunctional wearable sensing device. This device demonstrated exceptional sensitivity and a reversible humidity response to water, making it suitable for monitoring breathing patterns. Additionally, its rapid and stable electrothermal response upon water removal enables its use in low-voltage hyperthermia platforms for real-time therapeutic monitoring. Elsewhere, a Kevlar/Ti3C2Tx-based wearable textile was developed, which can be integrated into various fabrics and products for advanced sensory systems (Cheng and Wu, 2021). An intelligent mask was showcased for precise monitoring of human respiratory activity, offering potential applications in disease detection and remote health diagnostics. Furthermore, a smart temperature-responsive glove was introduced to predict and prevent hazardous situations by sensing environmental dangers in advance. Benefiting from an ultra-fast response time of 90 m, resilience of 110 m, and high-pressure sensitivity, these MXene-based wearable systems provide comfortable and convenient solutions for respiratory health monitoring and hazard detection through touch sensing.

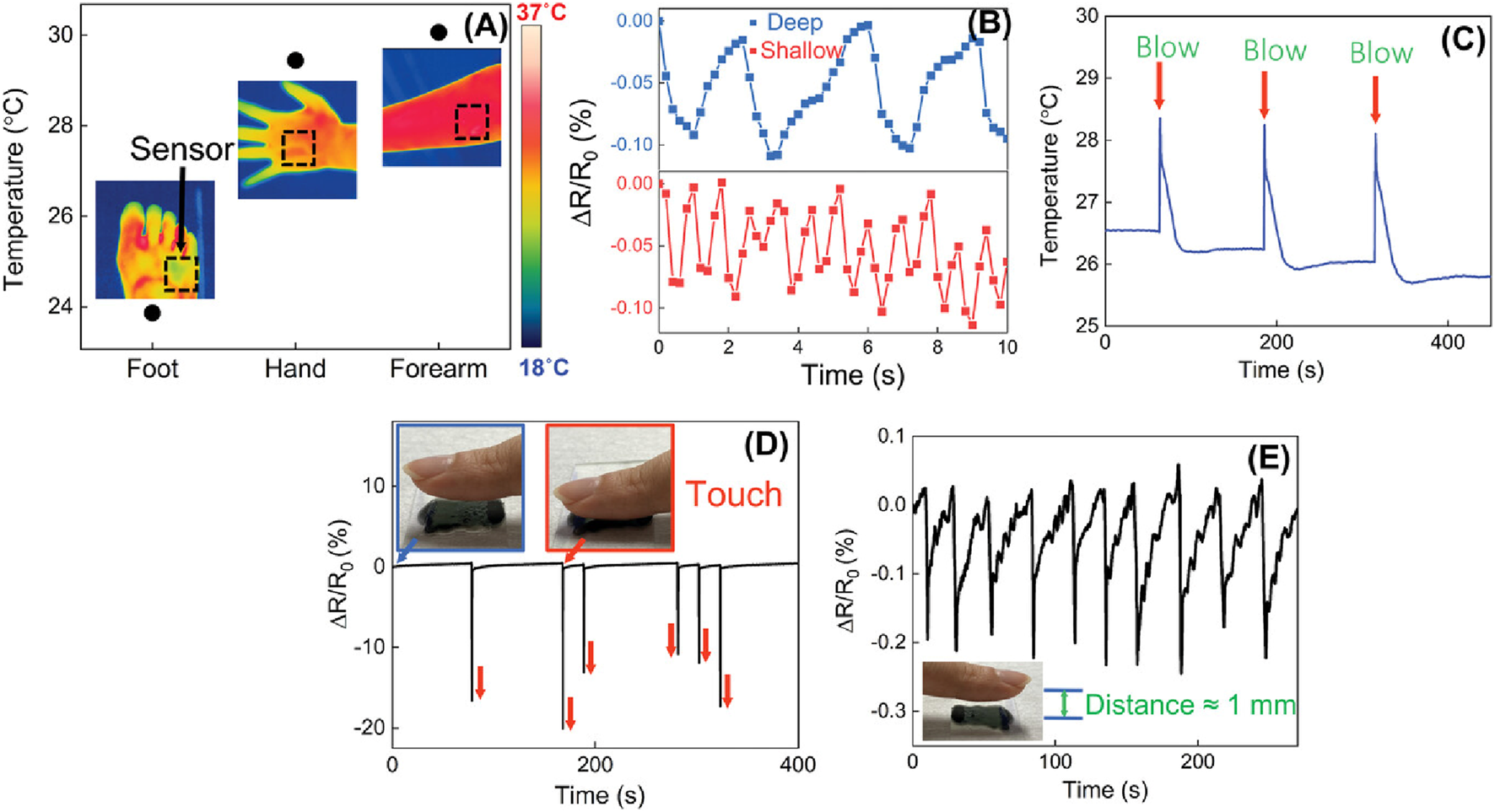

Mohapatra et al. (2023) employed atomic layer deposition to develop both contact and non-contact modes of real-time temperature sensing. In their work, V-MXene was modified with ruthenium (Ru) to enhance its electronic properties and improve electron transport channels within the layered MXene structure. When the sensor was attached to different parts of the human body, it successfully monitored temperature variations, providing insights into blood circulation. As shown in Figure 8, temperature readings varied across body regions: approximately 24 °C for the foot, ∼29 °C for the hand, and ∼30 °C for the forearm. The relatively lower temperature of the foot suggests reduced blood circulation in the extremities. Additionally, breathing and blowing monitoring was demonstrated by positioning the temperature sensor near the nostrils. The sensor detected temperature differences between inhaled and exhaled air, with exhalation being warmer in healthy individuals. This temperature variation caused measurable resistance changes, enabling real-time assessment of respiratory health. A similar concept was applied to blowing, where exhaled air exhibited higher temperatures. The sensor also responded effectively to touch, showing resistance changes of −10% to −20% when a warm finger approached. Furthermore, non-contact detection was achieved through proximity sensing, where resistance variations indicated the presence of nearby objects (Figure 8E). These capabilities highlight the versatility of MXene-based sensors for comprehensive health monitoring and interactive applications.

FIGURE 8

Ru-ALD engineered DM-V2CTx MXene enables real-time detection of skin temperature, breathing, blowing, touch, and proximity. (A) Practical measurements of human skin temperature alongside corresponding infrared images. (B) Breathing patterns: deep breathing (top, blue) and rapid/shallow breathing (bottom, orange). (C) Blowing test response. (D) Contact-based fingertip touch detection. (E) Non-contact proximity sensing. Reproduced from (Mohapatra et al., 2023).

Sleep is a vital component of human health, and inadequate quality or quantity of sleep can lead to serious adverse effects (Fobiri et al., 2025; Adepu et al., 2021). Sahatiya et al. (Adepu et al., 2021) demonstrated a MXene-based hybrid sensor (Ti3C2Tx/NiSe2) designed to monitor sleep patterns. The sensor was integrated into a bed to track breathing rates during sleep and detect various body postures, offering significant potential for personalized healthcare applications. Similarly, Pu et al. (2019) developed a posture-monitoring sensor composed of an AgNW/waterborne polyurethane (WPU) multilayer combined with MXene, fabricated using a layer-by-layer approach. This sensor exhibited outstanding sensitivity with a gauge factor (GF) greater than 100, a wide strain detection range of 0%–100%, and excellent durability over 100 cycles, along with a rapid response time of 344 m. Leveraging these properties, the sensor was incorporated into clothing to monitor body posture, analyze alignment, and provide corrective feedback. These advancements demonstrate that wearable sensors can significantly enhance individual wellbeing by enabling affordable, reliable, and real-time monitoring solutions using advanced materials, such as MXene.

4 Positioning MXenes among 2D materials for wearable sensor applications

Compared to other commonly used 2D nanomaterials, MXenes offer distinct advantages, particularly their exceptionally high electrical conductivity, which extends from single layers to multilayered structures, as well as their tunable surface area and surface functionalities. These properties make MXenes highly versatile and attractive for emerging applications in the health sector, especially in the development of wearable sensors. Their mechanical robustness and hydrophilicity further support their integration into flexible, real-time health monitoring systems powered by artificial intelligence and emerging technologies.

4.1 Performance, cost and scalability considerations

As tabulated in Table 4, MXenes, like other 2D nanomaterials such as graphene and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), face several key challenges, including industrial scalability, consistency in material quality, and the tendency of nanosheets to re-stack, all of which can hinder their performance and reproducibility in practical applications. However, MXenes stand out due to their exceptionally high electrical conductivity, which is retained across both single-layer and multilayer structures. This property, combined with their excellent mechanical strength, hydrophilicity, and surface tunability, makes them particularly attractive for the development of wearable sensors that require flexibility, durability, and real-time responsiveness. Graphene, while also highly conductive, shows a significant drop in performance when transitioning from single-layer to bulk films (often 2-3 orders of magnitude). Its properties are highly sensitive to the number of layers, structural defects, and synthesis methods, making standardisation difficult. Moreover, scalable production of high-quality graphene remains complex and costly. In the case of graphitic g-C3N4, this material offers advantages such as low-cost synthesis, biocompatibility, and easy surface modification through doping and defect engineering. However, its electrical conductivity is relatively lower than MXenes and graphene, and surface modifications may compromise its long-term biosafety. Additionally, green and scalable synthesis routes for g-C3N4 are still under development.

TABLE 4

| Materials | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| MXene |

|

|

| Graphene |

|

|

| g-C3N4 |

|

|

Comparison between MXenes and other 2D nanomaterials.

MXenes also show promise in real-time health monitoring when integrated with AI and emerging technologies, but their susceptibility to oxidation and the lack of comprehensive toxicity and biosafety studies remain barriers to widespread adoption. Therefore, further research is needed to develop MXene-based sensors that are environmentally stable, biocompatible, and scalable, ensuring their successful deployment in diverse regions and climates.

4.2 Current challenges and future perspectives

Despite their potential, MXenes face several critical challenges that must be addressed to enable their successful transition from laboratory research to real-world applications. One major hurdle is the scalability of MXene production with precision, which remains in its early stages. Conventional synthesis methods often rely on toxic and corrosive acids, such as HF, raising concerns about safety, environmental impact, and waste management (Ullah et al., 2025). Although alternative synthesis routes, such as LiF/HCl etching, molten ZnCl2 treatment, electrochemical methods, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD), are being explored to mitigate these issues, MXenes produced via these methods often lack the surface functionalities typically achieved through HF-based synthesis. This highlights the urgent need for flexible, environmentally friendly, and scalable synthesis techniques that can produce MXenes with desirable properties while minimizing health and environmental risks (Jolly et al., 2021).

Additionally, MXenes are susceptible to oxidation in aerated water environments, which compromises their long-term stability and performance, particularly in wearable devices exposed to varying climatic conditions, humidity, and temperature. The limited understanding of MXenes stability under such oxidative conditions remains a significant barrier to their practical deployment. Furthermore, while MXenes are considered highly promising for revolutionising materials science, comprehensive toxicity and long-term biosafety studies are still lacking, which is essential for their safe use in biomedical and consumer technologies. Therefore, continued research and development are crucial to engineer MXenes-based sensors that are environmentally resilient, biocompatible, and scalable, ultimately enhancing their global adoption and impact.

The majority of studies have focused primarily on Ti3C2Tx MXene, indicating that further investigation is needed to explore the properties and potential applications of other MXene compositions, particularly in the development of wearable devices. While it may be assumed that the knowledge gained from Ti3C2Tx can be directly transferred to other MXenes, this is not necessarily the case. Each MXene variant may exhibit distinct structural, chemical, and functional behaviours, requiring dedicated research to fully understand and optimize their performance. Therefore, the same level of systematic study and characterization applied to Ti3C2Tx should be extended to other MXenes to unlock their full potential across diverse applications.

5 Conclusion

In this review, we have comprehensively discussed the synthesis strategies and unique properties of MXenes that underpin their growing application in wearable sensors for health monitoring. To date, chemical etching; particularly using HF or in situ generated HF; remains the most widely adopted method for MXenes synthesis. However, this approach presents significant challenges, including toxicity, limited scalability, and inconsistent surface functionalities. Consequently, alternative synthesis routes, such as fluorine-free etching, molten salt methods, and bottom-up techniques including chemical vapor deposition are being actively explored to overcome these limitations. MXenes possess a suite of advantageous properties; high electrical conductivity, mechanical flexibility, hydrophilicity, and tunable surface chemistry; that make them ideal candidates for integration into wearable biosensors. These sensors offer non-invasive, real-time monitoring of critical biomarkers, enabling early diagnosis and personalized healthcare. Recent advancements have demonstrated MXene-based devices capable of multimodal sensing, enhanced sensitivity, and seamless skin integration. Despite these promising developments, several challenges remain. The transition from laboratory-scale synthesis to industrial-scale production is hindered by issues such as control over defect density, surface terminations, and reproducibility across different research groups. Most published studies rely on in-house MXene synthesis tailored to specific applications, resulting in limited cross-comparability and standardization. Moreover, the use of hazardous chemicals in conventional etching processes raises concerns about environmental and user safety. Nonetheless, the recent successes in MXene-enabled wearable sensors highlight their transformative potential. These devices offer flexibility, biocompatibility, and continuous monitoring capabilities, making them well-suited for tracking essential health indicators. Continued research into scalable synthesis, surface engineering, and integration strategies will be crucial to unlocking the full potential of MXenes in next-generation healthcare technologies.

Statements

Author contributions

KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. TM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors acknowledge the NRF Thuthuka grant (TTK230508103666), University of the Witwatersrand and Mintek for financial support.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adepu V. Kamath K. Mattela V. Sahatiya P. (2021). Development of Ti3C2Tx/NiSe2 nanohybrid‐based large‐area pressure sensors as a smart bed for unobtrusive sleep monitoring. Adv. Mater. Interfaces8, 2100706. 10.1002/admi.202100706

2

Alanazi N. Selvi Gopal T. Muthuramamoorthy M. Alobaidi A. A. E. Alsaigh R. A. Aldosary M. H. et al (2023). Cu2O/MXene/rGO ternary nanocomposites as sensing electrodes for nonenzymatic glucose sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.6, 12271–12281. 10.1021/acsanm.3c01959

3

Ambaye A. D. Mamo M. D. Zigyalew Y. Mengistu W. M. Fito Nure J. Mokrani T. et al (2024). The development of carbon nanostructured biosensors for glucose detection to enhance healthcare services: a review. Front. Sensors5, 1456669. 10.3389/fsens.2024.1456669

4

Anasori B. Shi C. Moon E. J. Xie Y. Voigt C. A. Kent P. R. et al (2016). Control of electronic properties of 2D carbides (MXenes) by manipulating their transition metal layers. Nanoscale Horizons1, 227–234. 10.1039/c5nh00125k

5

Antony Jose S. Ralls A. M. Kasar A. K. Antonitsch A. Neri D. C. Image J. et al (2025). MXenes: manufacturing, properties, and tribological insights. Materials18, 3927. 10.3390/ma18173927

6

Babar Z. U. D. Iannotti V. Rosati G. Zaheer A. Velotta R. Della Ventura B. et al (2025). Supplementary information MXenes in healthcare: synthesis, fundamentals, and applications.

7

Basivi P. K. Selvaraj Y. Perumal S. Bojarajan A. K. Lin X. Girirajan M. et al (2025). Graphitic carbon nitride (g–C3N4)–Based Z-scheme photocatalysts: innovations for energy and environmental applications. Mater. Today Sustain.29, 101069. 10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.101069

8

Bisht N. Jaiswal S. Vishwakarma J. Gupta S. K. Yeo R. J. Sankaranarayanan S. et al (2024). MXene enhanced shape memory polymer composites: the rise of MXenes as fillers for stimuli-responsive materials. Chem. Eng. J.498, 155154. 10.1016/j.cej.2024.155154

9

Bor J. Herbst A. J. Newell M. Bärnighausen T. (2013). Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science.339, 961–965. 10.1126/science.1230413

10

Borah A. J. Natu V. Biswas A. Srivastava A. (2025). A review on recent progress in synthesis, properties, and applications of MXenes. Oxf. Open Mater. Sci.5, itae017. 10.1093/oxfmat/itae017

11

Borysiuk V. N. Mochalin V. N. Gogotsi Y. (2015). Molecular dynamic study of the mechanical properties of two-dimensional titanium carbides Tin+1Cn (MXenes). Nanotechnology26, 265705. 10.1088/0957-4484/26/26/265705

12

Cai Z. Kim H. (2025). Recent advances in MXene gas sensors: synthesis, composites, and mechanisms. Npj 2D Mater. Appl.9, 66. 10.1038/s41699-025-00586-w

13

Carpenter A. Frontera A. (2016). Smart-watches: a potential challenger to the implantable loop recorder?Europace18, 791–793. 10.1093/europace/euv427

14

Chakraborty M. Hashmi M. S. J. (2018). “Graphene as a material – an overview of its properties and characteristics and development potential for practical applications,” in Anonymous reference module in materials science and materials engineering (Elsevier).

15

Chen H. Wen Y. Qi Y. Zhao Q. Qu L. Li C. (2020). Pristine titanium carbide MXene films with environmentally stable conductivity and superior mechanical strength. Adv. Funct. Mater.30, 1906996. 10.1002/adfm.201906996