- 1TU Berlin/Chair of Economic Education and Sustainable Consumption, ConPolicy and Technical University Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2TU Berlin/Chair of Economic Education and Sustainable Consumption, Technical University Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 3ConPolicy, Berlin, Germany

Popular literature and guidebooks on minimalism and decluttering have brought the idea of “less is more” into the mainstream. Although decluttering constitutes a central household chore in consumer societies, it is rarely communicated as work within the current popular minimalism discourse, but rather as an expression of self-care. Whether and to what extent this “lifestyle minimalism” can contribute to sustainable consumption has – with a few exceptions – not yet been studied in detail. In this article, decluttering is first conceptualized in between housework and self-care. Based on this work, potentials and limits for the promotion of sustainable consumption are outlined. Finally, initial insights from an ongoing citizen science project on decluttering in Germany are presented. The qualitative results from two workshops and two reflection exercises show that the main motivation for participants is the dissatisfaction with their multitude of possessions and the desire for fewer material possessions in the future. The decision to declutter can be understood as a window of opportunity in which individuals are willing to reflect on and realign their possessions and desires for goods. Thus, we argue that decluttering can be a relevant starting point for changing consumption behavior toward (more) sustainable consumption. At the same time, it remains unclear whether and to what extent the participants' willingness to change regarding possessions and consumption actually leads to more sustainable consumption behavior after decluttering. It is even conceivable that the newly gained space will stimulate additional consumption. Decluttering would then rather function as a catalyst for further consumption (and would have no or rather a negative contribution to sustainability goals). Further research is needed to shed light on this.

Introduction

Modern consumer societies are characterized by households that are filled to the brim with products and goods (Baudrillard, 2018). Consumers accumulate things–they collect, store and stow them away (Belk, 1982). However, hardly anyone knows the total number of goods or can remember every single thing in their possession. As Belk (1988, p. 160) points out “we are what we have and […] [this is the] most basic and powerful fact of consumer behavior.” In most households, however, the spatial capacities for storing goods and things are limited. To address this issue, people either try to gain additional storage space (e.g., through purchasing additional wardrobes) or they start to declutter. Such practices enable them to continue consuming regularly and to actively take part in consumer society.

Sorting out and decluttering goods are central household tasks in consumer societies. In recent years, decluttering has increasingly received attention, especially through the publications of Marie Kondo (Kondo, 2014) and numerous follow-up self-help and guidebooks, blogs and magazine articles on this topic. In popular literature however, decluttering is no longer pictured as simple housework, but rather as an expression of self-care (Lee H.-H., 2017; Ludwigsen, 2019; Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021). Even though concepts and movements such as voluntary simplicity or minimalism have been known for decades (Etzioni, 1999), this so-called “lifestyle minimalism” (Meissner, 2019) of Marie Kondo and Co has brought the idea of “living with less” into the mainstream. The central promise of “lifestyle minimalism” is that having less possessions promotes well-being. In recent years, numerous researchers have examined the link between minimalism and well-being (for an overview see e.g., Hook et al., 2021). However, whether and to what extent the practice of decluttering, as a specific method to achieve a minimalist life, can contribute to more sustainable consumption in the long term has not yet been sufficiently explored. In a study on the KonMari method Chamberlin and Callmer (2021) provide initial promising qualitative evidence that decluttering can have positive effects on sustainable consumption. They show, for instance, that practitioners of the KonMari method reflect on their goods and the question of what satisfaction they experience from their material possessions. They also show that the practitioners express less interest in new acquisitions. Building on these initial results, a further consideration – both conceptually and empirically – of possible potentials and limitations of decluttering for sustainable consumption is considered important.

On the one hand, it can be argued that decluttering guidebooks provide diverse impulses for reflection and learning that might help consumers question their needs, existing possessions, and the necessity of new acquisitions. Decluttering guides often describe methods for decluttering very clearly and give concrete suggestions for implementation. The resulting positive effects of “liberation from excess” (Paech, 2012) can be experienced directly after decluttering and might motivate people to own fewer things in the long term. Further, communicating decluttering as a form of self-care can potentially help to promote a positive perception of living with reduced possessions and thereby attract new target groups for sustainable consumption (even if unintentionally). On the other hand, decluttering is focused at getting rid of as many goods as possible in the shortest feasible timeframe. Since sustainability-oriented practices of passing on goods, reselling or repairing them are rather slow and time-consuming, they can hardly be implemented in the rather fast approach of decluttering. Also, decluttering guides usually only address so-called “peanuts” of sustainable consumption, but rarely the most environmentally relevant areas of consumption [e.g., space and heating, mobility, meat consumption (Bilharz and Schmitt, 2011; Geiger et al., 2018)]. In addition, there is a certain risk of relapse into old consumption patterns, as the newly created space might stimulate new purchases.

Against this background, the article at hand takes a close look at the phenomenon of decluttering, illustrates its characteristics within general household work, discusses its potentials and limits for sustainable consumption and presents initial results of participatory research components from an ongoing research project. Firstly, the article describes how the cultural practice and meaning of decluttering has changed in recent years. We thereby shed light on the emergence of decluttering as a method within the framework of “lifestyle minimalism” and locate decluttering in between the spectrum of housework and (self-)care. Secondly, we develop our reflections and conceptual considerations on potentials and limits of decluttering for the promotion of sustainable consumption. Thirdly, we present first qualitative results from our ongoing citizen science research project. To be able to better classify the results, we first explain our participatory research approach. Then we present the results of two workshops and the evaluation of two reflection exercises, which have been answered by the citizen scientists. In doing so, we provide first qualitative evidence from a selected group of citizens in Germany for the discussion on potentials and limits of decluttering for sustainable consumption.

Decluttering: A method for lifestyle minimalism and household work

In a first step, we outline the development of minimalism as a lifestyle concept and decluttering as a central method to achieve a minimalist life. In a second step, we show that this lifestyle-related, pop-cultural understanding of decluttering is closely related to a reframing of housework as self-care.

The evolution of minimalism as lifestyle concept and the role of decluttering

Looking at human history, various cultures and religious communities (e.g., Hinduism and Buddhism) have associated a “good life” with limiting possessions or avoiding excessive consumption. However, these historical movements were not concerned with a reduction of possessions in the context of affluence, but rather with a forward-looking avoidance of “too much” as well as an adequate use of resources that were perceived as limited for each individual. During recent decades, terms such as voluntary simplicity, simple life, minimalism, or anti-consumption have been used to describe lifestyles that focus on reduction of material possession (Rebouças and Soares, 2021). Etzioni (1998, p. 620) for example, describes voluntary simplicity as “the choice out of free will [...] to limit expenditure on consumer goods and services, and to cultivate non-materialistic sources of satisfaction and meaning.” Alexander and Ussher (2012, p. 66) understand “the Voluntary Simplicity Movement […] as a diverse social movement made up of people who are resisting high consumption lifestyles and who are seeking, in various ways, a lower consumption but higher quality of life alternative.” So-called voluntary simplifiers usually reflect on the influence of overconsumption and/or overwork on their personal wellbeing and “prefer to determine what is enough for themselves and earn only what they need to get by” (Grigsby, 2012, p. 1). Besides, the process of downshifting can be seen as an act toward voluntary simplicity (Aidar and Daniels, 2020), which aims at increasing one's well-being by decreasing work-load, income, and the total consumption level (Tan, 2000; Schor, 2008; Chhetri et al., 2009). All these downshifting practices within the context of voluntary simplicity, simple life or minimalism have the potential to contribute to sufficiency. Sufficiency is considered a key sustainability strategy – which, unlike consistency and efficiency – is behaviorally oriented and focusses on the absolute reduction of resource consumption (Schneidewind and Zahrnt, 2014).

Even though there was and is a lot of scientific interest in downshifting concepts and their potential for reduced consumption, they remain niche phenomena in Western consumer societies. Much has been written about it, but the actual implementation of a minimalist life is more imagination than reality for the majority. However, it seems that this has changed to some extent with the great popularity of Marie Kondo in the public (Kondo, 2014). Her reception of minimalism and especially the combination with “decluttering” has brought the vision of “happiness through less” into the mainstream. Vladimirova (2021, p. 112) argues that the success of the method of decluttering was not accidental, but rather timely: “The book appeared exactly at the moment when the disorder caused by excessive consumption, including fast fashion, reached a new peak”. Khamis (2019) describes Marie Kondos KonMari method as part of a broader trend of minimalism and alternative consumption that emerged after the global financial crisis in 2008 and the growing awareness of the negative effects of capitalism.

A closer look at Marie Kondos approach reveals that it is not only a guide for clearing out and decluttering. Rather, it promises nothing less than a life-changing impact (Kondo, 2014). As Marie Kondo writes in the introduction of her work (Kondo, 2014, 2/3): “A dramatic reorganization of the home causes corresponding dramatic changes in lifestyle and perspective. It is life transforming.” Based on the “life-changing” perspective on the benefits of decluttering and the holistic approach, numerous guidebooks, blogs, video-blogs (vlogs) and magazine features emerged in the following years. In contrast to earlier (scientific) publications on the topic of minimalism, voluntary simplicity or sufficiency, these guidebooks are characterized by being practical and easy to understand. They contain concrete suggestions that seem to fit well into everyday lives of consumers and convey the feeling that anyone can use the method and start immediately. Further, simple and minimalistic designs are used to showcase content and exercises. The suggested techniques, tips and exercises are comprehensive and versatile. They do not only cover decluttering and tidying up the house, but also, for example, the reorganization of communication and work routines (Meissner, 2019).

Lifestyle minimalism and decluttering are characterized by a central “promise of happiness”: In contrast to the basic assumption of consumer society (more goods make happy), the opposite assumption is propagated (fewer goods make happy) (Biana, 2020). This promise corresponds with a contemporary mindset in which exhaustion and overload due to consumerism and over-consumption are widespread in the mainstream of society. Studies also confirm the negative effects of overconsumption and clutter on well-being (Roster et al., 2016; Swanson and Ferrari, 2022) while showing clearly positive effects of decluttering on well-being (Hook et al., 2021). However, the political, economic, and cultural framework conditions that cause or contribute to the accumulation of clutter and the corresponding exhaustion are hardly even considered within decluttering guides (which in turn comes along with the positive observed effect of simplified content that reaches a larger target group). The focus of lifestyle minimalism and decluttering lies on the “aestheticization of individual restrain” within the existing economic system (Khamis, 2019). Since the focus is to achieve more joy, happiness, and well-being through decluttering, the “work character” of decluttering is concealed. Decluttering as a central household task, however, is much older than the lifestyle trend of minimalism and decluttering suggests. In the following, we will therefore elaborate on decluttering in the context of household work.

Decluttering as housework and care

Even though the available living space has steadily increased in Western countries over the past decades (e.g., in Germany alone between 1995 and 2004 an increase by about 13% even with a stagnating population, trend is still upwards, UBA [German Federal Environment Agency], 2010), space for the accumulation and storage of goods is finite. Similar to the “scarcity of time” due to an increase in time-consuming activities (Rosa, 2003), space in flats and houses is limited and can only be expanded very slowly, if at all. Practices of sorting out, decluttering, giving away and disposing of goods are accordingly regular and necessary activities to continue to take active part in consumer society. It is therefore almost surprising that companies that make a big advertising effort to sell new products do not offer much advice and support for consumers in getting rid of things. Furthermore, it is remarkable that decluttering is a rather “young phenomenon” (see The evolution of minimalism as lifestyle concept and the role of decluttering) and not an established issue in research on household work. One reason for this might be the limited recognition of consumption work as household work.

With the emergence of consumer societies in the mid-20th century, consumer work became central tasks of households (Glucksmann, 2016; Wheeler and Glucksmann, 2016). Contrary to what the term suggests, consumption is always productive and thus involves work. Consumption work can be defined as “all work necessary for the purchase, use, re-use and disposal of consumption goods and services” (Glucksmann, 2016, p. 881). Consumption work is necessary because the mere acquisition of consumer goods is rarely sufficient to completely satisfy consumer needs. Goods must be adapted and further processed to be individually valuable (e.g., a pleasant dinner requires not only the purchase of food, but also, for example, cooking and table setting). Many of these consumption-related activities are usually understood as household work. However, they are not sufficiently linked to the conditions and challenges of a consumer society yet. Research on household work still has a strong focus on the social recognition of unpaid household work and its gender-specific distribution (Thébaud et al., 2021). Moreover, there is an emphasis on the variety, quantity, and duration of household work, but less on individual, selected activities. The causes, functions, and conditions of individual household activities in the context of a consumer society play a subordinate role. This becomes particularly obvious with the example of decluttering. To the best of our knowledge, sorting out and decluttering activities, hardly play a role in the analysis of household work (Sweet, 1988; Keith Bryant et al., 2004; Eichler, 2008; Moreno-Colom, 2017).

In the following, we therefore aim to bring in an alternative understanding of decluttering as household work. According to Eichler (2008, p. 15) “[h]ousehold work consists of the sum of all physical, mental, emotional and spiritual tasks that are performed for one's own or someone else's household and that maintain the daily life of those for whom one has responsibility.” Household work thus always has two dimensions: an activity- and thing-related dimension (housework) and a more relationship-related dimension (care) (Eichler, 2008). Both dimensions are directly linked to each other.

Before decluttering becomes relevant and necessary, sorting, organizing, and storing goods are the preceding central household tasks. As Collins and Stanes (2021, p. 4) point out, storage is a “central routine practice in the organization of everyday life […] [and] presents a range of practical solutions to managing material accumulations.” Cwerner and Metcalfe (2003, p. 229) illustrate, that storage is the “key to understanding how people create order in the home” and even in their life. The authors argue that storage is much more than the simple physical-material arrangement of things but in fact an expression of caring for people and goods (Cwerner and Metcalfe, 2003; Collins and Stanes, 2021). There are various forms and ways of storing and the “right degree of tidiness” is a very subjective one. Nevertheless, it can be argued that there are strong cultural notions and implicit norms about how “filled with things” a home should be. The impact of these implicit norms is particularly evident in the social exclusion and devaluation of so-called hoarders (Newell, 2018). Hoarders are characterized by owning more things than they can adequately store and the inability to let things go. They overcrowd their houses with things that–according to current norms-belong in storage or in the garbage. This makes hoarders “reclassified as belonging to the ‘outside' of deviancy, as someone incapable of maintaining themselves” (Newell, 2018, p. 4). Within the tension of successful, almost invisible storage on the one side and hoarding on the other side, the need to declutter arises. The practice of decluttering thus serves the central function of preservation and regeneration in households. Assuming the continuous accumulation of goods, and at some point, a filled storage space, practices of decluttering enable households to repeatedly acquire and successfully store goods. Even if it seems obvious and rather simple to get rid of things, when the quantity of goods becomes too much, decluttering often poses a great challenge. As Lee H.-H. (2017, p. 454) illustrates, “consumers often attribute the cause of having ‘too much' to the overall volume rather than specific objects, which makes it hard to choose what to discard.” In addition, many things are not “neutral,” but people have multiple emotional ties with them.

Apart from the analysis of specific decluttering methods such as KonMari (Lee H.-H., 2017; Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021), there is–to the best of our knowledge–still a lack of research on the frequency, arrangement and gender-specific distribution of decluttering as a task of household work. It can be assumed that there is a wide range of decluttering practices that people use. While some people might repeatedly sort out single things at short time intervals, others might take more time to dispose of a larger number of things and do this at larger time intervals. Even if people declutter in short intervals, decluttering is not a daily chore. With regard to the different types and frequency of housework (daily housework includes e.g., food preparation, dish washing or laundry; occasional housework includes e.g., construction and repairs, gardening or shopping) decluttering can be understood as occasional housework (Moreno-Colom, 2017). From research on housework it is well known that women are more involved in daily housework, while men are more likely to do the occasional chores (Moreno-Colom, 2017). Whether and to what extent this is transferable to decluttering is not yet known.

Decluttering as housework involves a variety of mental and physical activities. As Roster (2001) already shows for the disposal of goods, the psychological “process of dispossession” can be rather complex. Moreover, different notions of tidiness and cleanliness might influence the decluttering process (Dion et al., 2014). In a first step of the decluttering process, even if only for a few seconds, goods are selected, examined, and reflected upon in terms of their usefulness and (personal) value. In this step, it is often necessary to consider the value of goods for other members of the household. This can be accompanied by negotiation processes about whether to keep things or not. In a second step, some of the goods are removed from their usual place of storage, while others are put back. Often, the returned goods are then re-sorted and re-ordered. After this selection process, the phase of disposal or transfer takes place as a third step. While a large part of the goods will probably be disposed of, it is also conceivable that goods are resold or given away. It can be assumed that there are very different contexts and situations in which decluttering takes place. However, unlike other occasional household chores, decluttering seems to have some frequent overriding occasions, such as the change of seasons, moving house or redecorating the home. In this respect, too, empirical data would be fruitful.

While decluttering is hardly considered as housework work in both scientific research literature and the decluttering guidebooks, the second dimension of household work, namely (self-)care, is emphasized to a large extent (Ludwigsen, 2019; Casey and Littler, 2021; Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021). This raises the question of how consumption and care are generally connected. As Godin and Langlois (2021) discuss, consumption often implies multiple care-giving activities for oneself and others within households. With reference to various studies, they illustrate how consumption activities often involve anticipating the needs and preferences of others. In addition to regular care activities through consumption (e.g., cooking, laundry etc.), there are numerous consumption practices that express caring also on a symbolic level (such as cooking soup for the sick, ironing a shirt for a spouse's important appointment, leaving lights on for family members coming home late) (Godin and Langlois, 2021). In the context of care and sustainable consumption, gender inequalities always become apparent. As still more women carry out care-giving activities in the household (as just mentioned, e.g., cooking), women are also more likely to practice more sustainable forms of these activities (e.g., buying organic food for cooking) (Bloodhart and Swim, 2020).

The analysis of consumption activities regarding their care dimensions can also be applied to decluttering. From this perspective, decluttering can be understood as a care-giving activity as it ensures the (re)production of a well-organized and pleasant home. Decluttering ensures that the household is not filled to overflowing, that household members feel comfortable, that household members save time looking for their goods, and finally, that the routine consumption practices can continue.

Decluttering, however, is mostly not communicated or marketed as care in general, but as self-care and self-help (Lee H.-H., 2017; Ludwigsen, 2019; Meissner, 2019; Ouellette, 2019; Casey and Littler, 2021; Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021). The WHO [World Health Organization] (2018) defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider.” Self-care includes a comprehensive set of different activities that can entail both therapeutic (e.g., medication administration) and personal care (e.g., daily living activities such as bathing, eating, exercise) (Godfrey et al., 2010). Decluttering as self-care assumes that clutter has certain negative psychological and even physical implications (e.g., stress, discomfort, and overload). These negative effects–so the assumption–can be reduced by liberating the home, and even the whole life, from too much stuff and clutter. Decluttering as a process of reducing (material) possessions might therefore help to increase well-being, balance, and happiness (Kondo, 2014; Lee H.-H., 2017; Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021). Accordingly, decluttering techniques (and also other cleaning and tidying “lifehacks”) are not only seen as “a quicker route to completing mundane drudgery, but a means of achieving a better emotional and affective state” (Casey and Littler, 2021, p. 10). Following this understanding, decluttering is not only an externally directed, thing-related activity, but also has a strong introspective meaning. “Tidying [and also decluttering] is [presented as] a dialogue with oneself. Through one's possessions, one is actually conversing with oneself. What one wants to own is how one wants to live life” (Biana, 2020, p. 83). Regardless of the question of how much decluttering can actually contribute to successful self-care and well-being (Roster et al., 2016; Swanson and Ferrari, 2022), there are numerous critical assessments of the concept from a socio-economic perspective. Casey and Littler (2021), for instance, see the interpretation of decluttering, contributing to women continuing and willingly taking on the greater share of housework. Ouellette (2019) argues similarly and understands decluttering as a “neoliberal technique” that depends in particular on work by women. She argues that the “happiness-promise” of the KonMari-method is problematic as it obscures structural problems of the consumer society and the distribution of housework. Meissner (2019, p. 193) criticizes that the understanding of decluttering as a form of self-help highlights the current shift of societal responsibility to individual self-responsibility and encourages “entrepreneurial practices of self-development and ‘life-maximization”'.

Building on this understanding (and critique) of decluttering as housework and self-care, the following section will outline possible chances and risks decluttering entails for the promotion of sustainable consumption.

Potentials and limits of decluttering for sustainable consumption

Sustainable consumption can be defined as “individual acts of satisfying needs in different areas of life by acquiring, using and disposing goods and services that do not compromise the ecological and socio-economic conditions of all people (currently living or in the future) to satisfy their own needs” (Geiger et al., 2018, p. 20). Sustainable consumption combines all three sustainability strategies (consistency, efficiency, and sufficiency), which are often not clearly separable from each other in everyday consumption practices. Sufficient consumption, however, takes on a prominent role in the realization of sustainable consumption (Schneidewind and Zahrnt, 2014; Gossen et al., 2019). Only if resource consumption is significantly reduced in absolute quantities, consumption styles of the Western hemisphere will be transferable to all currently living and future generations. This also leads to the conclusion that the focus on individual products and individual areas of consumption obscures the fact that sustainability can only be achieved if societal consumption patterns and lifestyles as a whole are taken into account. At the same time, it is valid, that not all consumption activities are equally relevant for an effective reduction of negative environmental (and social) impacts. There are specific consumption areas (housing, mobility, nutrition) and selected measures in these areas that have a significantly greater environmental impact than others (Bilharz and Schmitt, 2011; Geiger et al., 2018). To promote sustainable lifestyles, it is thus important to focus on the most relevant measures in the most relevant consumption areas.

Sufficient consumption can be realized through three different types of action, which are ideally combined with each other: (i) number: absolute reduction of the number of purchases of new products; (ii) dimension: use and purchase of (smaller) products with lower resource intensity (iii) frequency of usage: less frequent use of resource-intensive products and services (Jenny, 2016; Gossen et al., 2019). Regardless of which “reduction practice” is applied, it is important for sufficient consumption to achieve an absolute reduction in resource consumption without replacement. That means that rebound effects are avoided, in which financial resources saved in one area of consumption are used for more purchases in another area. This also means that short-term abstinence or temporary reductions in consumption are not sufficient. Rather, consumption routines and practices need to stabilize in the long-term in order to be qualified as sustainable.

Potentials for sustainable consumption

Decluttering and minimalism guides–as shown already–are characterized by being very practical and concrete. They are so-called “self-help books” (Lee M., 2017; Ludwigsen, 2019). Most of them explain step-by-step how to reduce one's possessions. The guides often include exercises, tips, and practical examples. These concrete instructions and their high practical relevance make it easy for anyone to get started. It seems advantageous here that the focus lies on what already exists, namely on the possessions in one's own home. Thus, the central aim of decluttering is not to think about and reduce diffuse, future consumption, but to start in the “here and now.” The so-called “liberation from excess” (Paech, 2012) becomes concrete through the practice of decluttering. This also has the advantage that positive effects of decluttering can be directly observed and experienced in the present and can possibly motivate to own fewer things in the future (e.g., direct relief from having to take care of fewer things, more clarity and order). A potential perceived increase in overall well-being (Roster et al., 2016; Swanson and Ferrari, 2022) might also have a positive influence on owning fewer things in the future. Following studies on the relationship between perceived self-efficacy and sustainable consumption (Hanss and Böhm, 2010), it can also be argued that the experience of successfully decluttering in one's own household can have positive effects on future sufficient consumption activities.

Furthermore, decluttering exercises are often combined with self-tests and reflection tasks that encourage the reflection on material possessions and consumption practices. One exercise that is suggested before actually sorting out goods, for example, instructs people to first estimate the quantity of the goods owned and to then count the actual number. This stocktaking exercise encourages people to closely look at their own possessions. Other frequently suggested exercises address the question of what is important in life or to what extent material goods are important (Morgan, 2017; Madsen, 2021). Reflection can also be stimulated during the decluttering process itself. The KonMari method, for example, is characterized by taking each object into one's hands and evaluating it in terms of the resulting feeling of happiness (Kondo, 2014). We argue that these reflection exercises can help people to develop reflection competencies and stimulate awareness and insights into existing needs and preferences, which then become relevant for starting the change process toward more sustainable consumption patterns. Competencies to reflect individual needs and cultural orientations are understood as key competencies for sustainable consumption (including knowledge of how preferences are culturally contextualized, ability to critically engage with commodification processes and willingness to explore and scrutinize one's own aspirations, wants and needs) (Fischer and Barth, 2014; Frank et al., 2019). These reflection competencies are typically conveyed in an educational context. Recently, the importance of mindfulness training for sustainable consumption has been discussed in particular (Fischer et al., 2017; Stanszus et al., 2017; Frank et al., 2019; Geiger et al., 2020). Mindfulness and decluttering are both techniques that are advocated in the context of self-help and self-care. Both promote introspection and reflection on needs. Building on existing studies on mindfulness and sustainable consumption, it can therefore be argued that decluttering likely contributes positively to establishing more sustainable consumption patterns.

Research shows that individuals do not necessarily decide to apply decluttering methods (such as KonMari) for ecological or ethical reasons, but rather for egoistic ones (Vladimirova, 2021). This is likely promoted by the fact that decluttering is communicated as a form of self-care and a variety of ego-related benefits are emphasized (see Decluttering as housework and care). However, this could also be seen as an unintentional way toward promoting sufficient consumption (Callmer, 2019; Kang et al., 2021). While, for instance, sufficient consumption is still perceived as a loss or a restriction by many population groups, decluttering and lifestyle minimalism guides shift the feeling of guilt or loss and promote the idea of enjoyment in the process of reducing material possession instead (Chamberlin and Callmer, 2021). Chamberlin and Callmer (2021, p. 25) “suggest that the increased focus on people's feelings about their material environment and its impact on their well-being can be associated with the unintentional slowing down of consumption among participants and that this, in turn, could provide an important way to engage mainstream consumers with a sufficient circular economy.” In sum, it becomes clear that there are relevant chances for sustainable consumption.

Limits for sustainable consumption

However, some risks and limits of decluttering for sustainable consumption are to be mentioned.

Kondo (2014) proudly mentions the number of belongings that her clients discarded as a sign of success for her method. “The number of things my clients have discarded, from clothes and undergarments to photos, pens, magazine clippings, and makeup samples, easily exceeds a million items. […]. I have assisted individual clients who have thrown out two hundred 45-liter garbage bags in one go” (Kondo, 2014, p. 2). Most consumers might want to see such quick results in their homes with the help of decluttering guidebooks. As already explained, a central chance of decluttering is that the associated measures can be implemented directly, and success becomes immediately visible. However, this also implies that there is a certain interest in implementing decluttering as quickly as possible. It's about achieving quick results and getting rid of stuff. This focus on speed stands in conflict with the necessary management of goods after sorting out, which can be very time-consuming when sustainability aspects are considered. Instead of just throwing things away quickly, it is of relevance to pass goods on and thereby give them a new purpose (Cooper, 2005). Passing on goods, e.g., to charities, second-hand shops, or simply other private individuals, however, often requires time and effort. In case goods are not passed on, but are disposed of in a sustainable way, they need to at least be appropriately separated and recycled. However, as Cooper (2005) shows, consumers often lack interest in investing time in the care and repair of goods in the use phase. Also, recycling, for example, is perceived as work. It is therefore hardly plausible to assume that decluttering promotes a sustainable after-use-phase. Instead, it can be assumed that decluttering simply results in the disposal of many goods that could still be used.

It seems that decluttering as an activity is mostly done at a specific time-period and does not require a fundamental change in the daily lifestyle of individuals. For instance, it does not imply a change in their commute to work or a change in location for grocery shopping. Therefore, it is usually seen as a (fun) project to do now and then and not as a demanding lifestyle-change toward sustainable consumption (which–as described already–also represents an opportunity). Adding to this, it is currently simply fashionable to choose minimalist consumption options. As Schneidewind and Zahrnt (2014, p. 146) state: “A new purism is taking hold in many areas of life, from single speed bikes to minimalist interior décor.” But this does not necessarily imply any changes in consumption routines. Besides, unless consumers become aware of the (mental, ecological, or financial) benefits of having and keeping a minimalistic lifestyle in the long term, they are unlikely to contribute to sustainable consumption at the end.

Decluttering primarily addresses the reduction in quantity of goods but does not necessarily touch on the reduction of regular consumer goods (e.g., food) or goods and services that induce particularly high resource consumption. Further, highly relevant consumption areas are often not targeted (e.g., space and type of heating, mobility, animal products), (Geiger et al., 2018) and resource-intensive activities and services remain unconsidered (e.g., holiday trips). Accordingly, “frequency of use” and “dimension” (i.e., two of the three action types for sufficient consumption) may not be promoted by decluttering at all. Regarding the third dimension of decluttering, “absolute reduction of new purchases,” even the opposite effect may occur. As decluttering reduces possessions, new space is created for new consumption. Decluttering would then rather be an accelerator or catalyst for further consumption rather than contributing to a reduction in new purchases. In decluttering guides, consumption practices after decluttering receive little attention. Even though some guides provide suggestions and exercises on how to prevent new purchases and consume less overall (e.g., through so-called no-shopping lists, avoidance of advertising, etc.). However, in our view, the difficulty of reducing consumption in the long term is not sufficiently considered. Even though Chamberlin and Callmer (2021) show that participants following the KonMari method no longer had the wish to purchase goods, it is unclear whether this effect holds in the long-term. Since it is plausible and obvious that the newly won space motivates to be filled again and consumers are tied into long practiced routines of consumption, this presents a central risk for sufficient lifestyles.

This possible relapse into old consumption patterns is closely linked to the previously discussed criticism of decluttering as a “(neo-)liberal, capitalist method” for more growth and acceleration (Meissner, 2019; Ouellette, 2019). Accordingly, the recommendations to reduce possessions on the one hand and the stimulation of further consumption actions on the other are not contradictory, but rather mutually dependent. Households can only consume new goods through the newly created space. As Meissner (2019, p. 186) argues, “growth hegemony remains largely unchallenged” […] [and] shows capitalism's tendency to appropriate and commodify its own counter-culture.

Research approach and initial qualitative insights into decluttering motives

In the following, we aim to shed light on motives for decluttering and associated reflections of wishes and needs by presenting first insights into the results of an ongoing citizen science research project from Germany. The project1 addresses the question of whether and to what extent decluttering practices can help to promote sustainable consumption and at the same time avoid the unwanted return to old patterns of consumption and accumulation after decluttering. To be able to better classify the initial research results presented below, our research approach will be illustrated in the next step. Afterwards the selected methods and the results will be presented. Finally, a discussion and presentation of the limitations and an outlook on further research will follow.

Exploring consumer behavior and decluttering in the context of citizen science

There are numerous definitions and interpretations of citizen science. However, at its core it always involves an active participation of the public in scientific research (Haklay et al., 2021). This means, that volunteers can take part in all phases of a research process, starting with the development of the research design, data collection, data evaluation and the derivation of recommendations for action.

While citizen science is particularly widespread in the natural sciences, there are fewer examples of consumption research by citizen science (Hielscher and Jaeger-Erben, 2021). From our point of view, the participation of citizen scientists in investigating the relationship between decluttering and sustainable consumption offers three key advantages: (i) Through open exchange and collaboration with citizen scientists, the research field can be broadly explored. This is valuable as there is rather little empirical evidence on our research question to build on. (ii) Secondly, the citizen scientists are very interested in finding out more about themselves and their relationship to their goods and are therefore motivated to provide insights into their consumption practices and decluttering experiences by using the cultural probes provided in the project. (iii) Thirdly, the citizen scientists have easy access to their peers to interview others about their decluttering and consumption experiences in a confidential and protected setting.

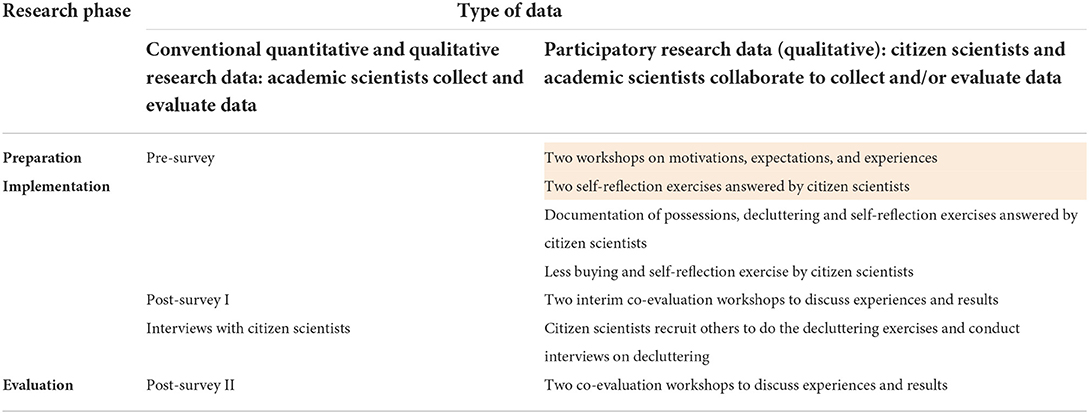

The research process is also characterized by the fact that, in addition to the collection of “conventional” quantitative and qualitative data by the academic scientists of the project, we collect and evaluate different streams of qualitative data together with the citizen scientists. Over the course of the whole project, this participatory, qualitative data consists of (i) six workshops, which take place at three different points in the course of the project, (ii) a set of cultural probes (Gaver et al., 1999), which consist of different (reflection) exercises and suggestions for reflecting, documenting and decluttering as well as for avoiding additional consumption, (iii) semi-structured interviews conducted by the citizen scientists with their peers about the experiences and effects of decluttering. The three phases of our research process and the different types of data collection streams are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Course of the research process and type of data collection (The highlighted data are presented in this article).

In the following we only focus on the results of the first two workshops (of the six workshops in total) and the results of the first two reflection exercises (as part of the cultural probes set) (displayed in color in the table).

Participation in the project was advertised online and offline through various communication channels. The main online communication channels were the mailing list of an NGO providing information on energy saving and climate protection (co2 online) and the mailing list of an NGO on sustainable fashion (Fashion Revolution Germany). Offline, the project was advertised via posters in a university and supermarkets. In total, more than 1,000 participants from all over Germany were recruited. Citizen scientists had to be 18 years old or above and live in Germany, in order to be qualified for participation.

Description of selected methods

As shown above, the project took up a mixed methods approach in combining conventional quantitative and qualitative methods together with a participatory research approach, that closely involved citizen scientists in collecting data. In the following, we present selected methodologies from only the participatory research, i.e., (i) the first two online workshops and (ii) two first reflection exercises, which are part of a larger cultural probes set developed as an intervention for the citizen scientists–and later–the larger public. The two workshops took place as online-workshops via Zoom in total with 51 citizen scientists (36 female, 15 male) in March 2022. Apart from gender, no other socio-demographic data was collected from the workshop participants. Each workshop was 2 h long. One workshop took place in the afternoon and one in the evening, to allow for flexible participation. Each workshop was moderated by one of the researchers and supported by another project team member. The workshops focused on the motivation and expectations of the citizen scientists for decluttering and offered an interactive exchange between citizen scientists. In the first part of the workshops, citizen scientists were intended to get to know each other in a round of speed dates and shortly reflect on the reasons for participation in the project.

In the second part of the workshops, citizen scientists were asked to engage in an exchange on the challenges and desires in dealing with possessions in more depth. The workshops explored three key questions in particular: (i) Why do participants want to declutter? (motivations); (ii) What do participants expect from decluttering? (expectations) and (iii) What experiences do the participants already have with decluttering? (experiences). We asked participants to elaborate on these key questions in three smaller subgroups and documented the key workshop results on a digital whiteboard. The outcomes of the discussion then provided valuable insights for the development and design of intervention materials (cultural probes set) of the project.

The two reflection exercises–as the first part of the cultural probes set–were carried out by the citizen scientists in April 2022. By using the information gathered in the first accompanying online survey (see Table 1), the participants who completed the reflection exercises can be characterized as follows: A total of 426 citizen scientists filled out the two reflection exercises. Among them, around 30% were male, while around 70% were female. Besides, more than half of the participants (59%) were between 51 and 70 years old, indicating that rather older generations participate in the project. Most of the participants were holding a university degree (70%), followed by 17% that had high school degree. Almost half of the participants (52%) who completed the reflection exercises were employed at a company and around 22% were already in retirement.

The first reflection exercise of the cultural probes set focused on peoples' general wishes in life. Participants could add up to five aspects (material or immaterial things) for each question and write down their answers in an unstructured manner. Participants received the following questions and sub questions to reflect upon:

1. What do you really want in life?

1a. What would you like to have more of in your life?

1b. And what would you like to have less of?

The second reflection exercise of the cultural probes set focused on selected goods from five household areas that people could claim to value the most. Participants received the following questions, that they could answer in an unstructured manner:

2. What Is “your thing”?

2a. Which goods in your household have a special value for you?

2b. Why are these goods important to you?

The questions for reflection in the cultural probes set were stated open and therefore participants were free to interpret them individually and add aspects that deemed important to them. The qualitative results of this reflection exercise were then analyzed with a software tool for qualitative content analysis (MAXQDA). For the analysis of the first exercise, a list of broad categories and identifiers for analysis were determined by using guiding literature (YouGov., 2015; Statista., 2021) to define the most important wishes in life. The initial set of themes for the first exercise was: relationships and love, health, money, recreation, experiences, success, creativity, and spirituality. The themes were applied to the material in a deductive manner. The raw data set was then coded by using this scheme. Later on, the category system was back-tested based on the concrete material in an inductive manner and categories were summarized and refined. Since the second exercise entailed quite specific questions, that could not be related to a theory, themes were developed only by proceeding in an inductive manner. We generally followed content-analytical procedures suggested by Mayring (2019) to analyze results and work out recurring patterns of answers and structures of meaning. The results were lastly interpreted in the light of the main research questions. In the following, results are presented mainly by referring to overarching themes that were mentioned. Additionally, the results are illustrated by using selected direct quotes of citizen scientists. Hereby, citizen scientists are cited by using an abbreviation and their unique ID (e.g., CS 1).

Results

Results from the workshops

Motivations

In both workshops, participants mentioned the problem of overcrowded houses. On the one hand, they report that this state of abundance (coupled with disorder) makes it difficult to find things that they need, but also constantly confronts them with objects that are not actively used anymore. Participants also expressed the desire to have more space in their home as well as achieve more clarity, order, and fixed places for the goods in their household. In the long run, participants mentioned that they hope to limit the number of objects they own, and thereby create a clearly arranged living environment. On the other hand, participants explain that the mere visibility of physical clutter in households puts mental load and a sense of stress on them. Adding to this, they mention that the number of goods even increases over time in most households, which may cause a feeling of loss of control over the situation. Against this backdrop, participants clearly articulate the need to find ways to reduce their stress, possibly by finding a long-term solution to better manage the number of goods they own.

Expectations

The participants mentioned that they seek mental freedom, peace of mind and psychological relief by decluttering. Also, simply having more time for other important things in their lives is a main reason for people participating in this project to start decluttering.

Experiences

Workshop participants mentioned to already have experience with decluttering, however, not necessarily by using a specific method to declutter. Although this task is regarded important in order to keep an overview and create a comfortable home by the participants, decluttering is described as being quite challenging in the past. One of the reasons for this mentioned is that a lot of objects have a strong emotional value for people, making it hard to let them go. Also, the participants report about the fact that decluttering objects with an emotional value in a shared household often involves negotiation processes with other family members, that people do not know how to approach. In other cases, participants illustrate that they are uncertain about whether they will still need particular everyday objects again in the future. They therefore seek specific evaluation and prioritization methods, to learn what is important to them, what they really need and how to clean out. Furthermore, participants mention their strong retention to clean things out because they don't want to just throw them away. The question of how to reuse decluttered items in a useful manner is mentioned as a major challenge in the application of decluttering methods.

Results from the first two reflection exercises

In the first reflection exercise of the project, participants were asked to think about what they really want in life. More specifically, they had to reflect what they wish for in life and what they wish less of. The main interest behind this reflection exercise was, firstly, to find out to what extent people focus on non-material or material things, and secondly, to what extent they reflect or problematize their own material possessions and consumption behavior.

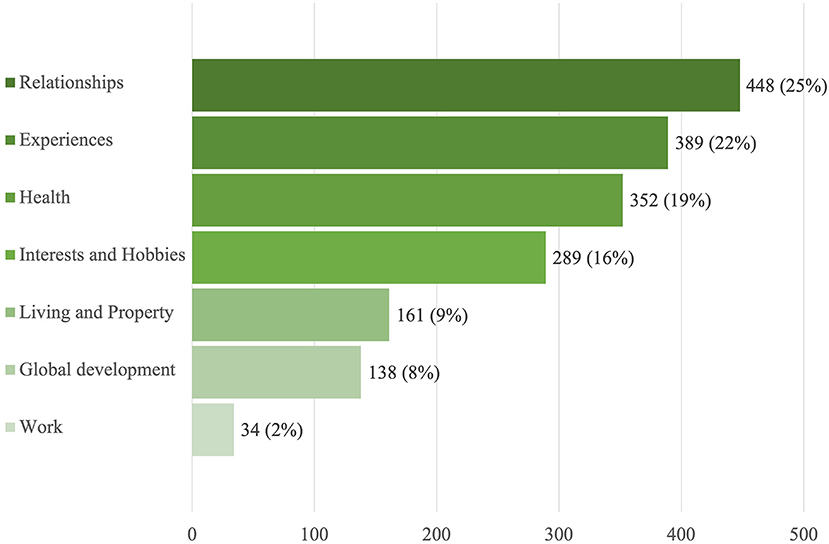

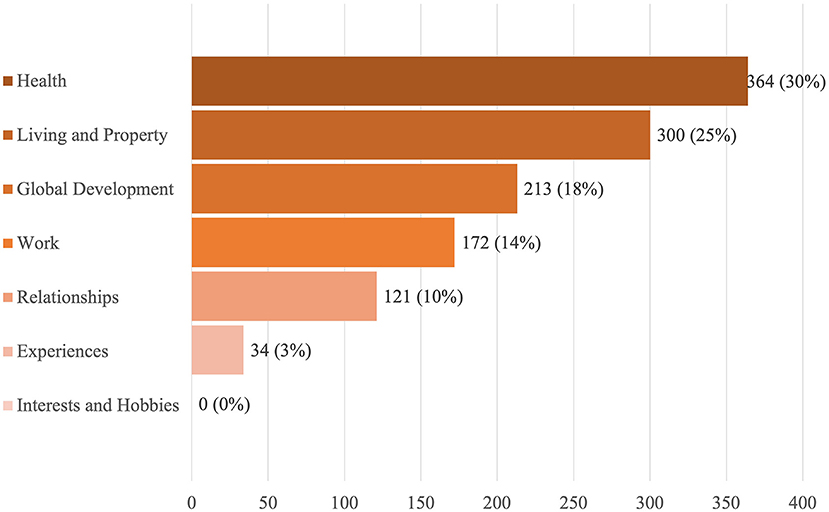

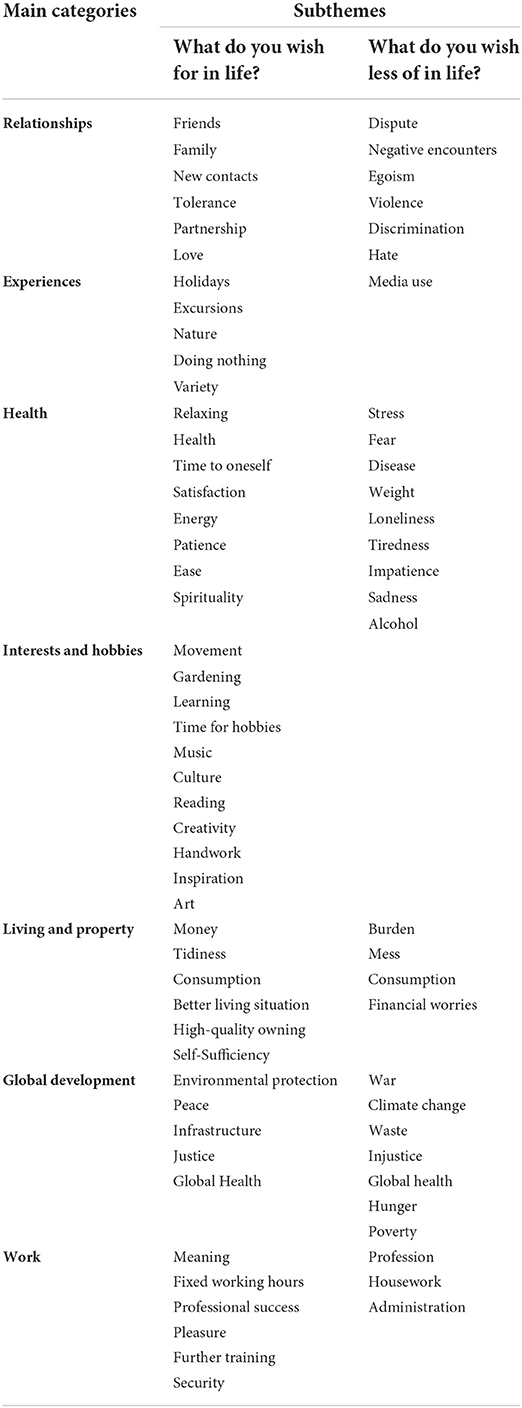

A graphical overview of the overarching results, showing the main themes and the frequencies of terms mentioned in that categories are displayed in Figures 1, 2. The same main themes were identified and used for the two sub questions, however, for the first sub question the themes refer to positive aspects, while for the second sub question themes refer to negative aspects. Figure 1 displays the most important themes participants wish for in life, while Figure 2 displays the most important themes participants wish less of in life, both sorted in descending order. Further, Table 2 displays a list of the main themes with corresponding subthemes for each question in ascending order of frequency.

Table 2. Overview of main categories and corresponding subthemes identified in reflection exercise 1.

The results show that citizen scientists participating in the project most frequently mention good “relationships” as an overarching theme that they wish for in life (25% of all mentions, see Figure 1). More specifically, they mention the wish to have time to maintain and cultivate their relationships with friends and family. One citizen scientist desired “moments of connectedness with my friends” (CS 360) while another person wished for more “time for our son and grandchildren” (CS 69). The citizen scientists further long for safety and love, but also wish to establish new contacts and get to know people. In contrast, negative aspects of “relationships” (10% of all mentions, see Figure 2) that participants wish to avoid are mentioned, such as dispute and trouble with friends, family, and neighbors, but also societal issues such as selfishness, discrimination, hate and violence. For example, one citizen scientist called for “less violence against children (CS 298).

An aspect that is also mentioned frequently as a wish in life is the interest in “experiences” (22%), such as traveling, excursions, spending time in nature but also having sufficient un-scheduled moments for doing nothing or enjoying free time. One citizen scientist expressed the wish to “travel by motorcycle-individually or in groups” (CS20). For quite some participants, having more time to pursue one's own “interests and hobbies” is also one of the wishes for the future (16%). The “interests and hobbies” mentioned by the citizen scientists include, inter alia, sports, gardening, learning new skills, listening to and making music. For example, having “time for practical music exercise” (CS 422) was mentioned by one person. Other citizen scientists sought to be creative, and thus hoped for “more time and space for creative activities” (CS 295) or “time for my artistic work” (CS 389). Additionally, the wish for time to enjoy arts and culture is expressed, for example, one citizen scientist would like to “visit cultural events” (CS 407). For some, having more time for experiences and time to pursue interests goes hand in hand with spending less time on “work,” which is gainful employment and housework (14%). Citizen scientists, for example, demanded “less physically poor working conditions” (CS 280) and hoped for less “duties (cleaning, tidying, organizing, etc.)” (CS 45).

Furthermore, participants reflect on their physical and psychological “health” when it comes to the question of what they want in life (19%, see Figure 1). The desire for more rest and relaxation was mentioned particularly often, followed by the wish for better mental and physical health both for themselves and those close to them. Other frequent wishes relate to improved life satisfaction, more time for themselves and increased energy. For instance, one citizen scientist longed for “energy to consistently implement a health exercise program” (CS 28) and another mentioned the wish for “inner peace and serenity for some issues that upset me” (CS414). Conversely, poor “health” and especially stress and mental load, illness, anxiety, fear, and loneliness as well as body weight, are mentioned as the most prevalent things worrying people (29%, see Figure 2). One citizen scientist communicated “I would like to have less stress at work” (CS 351)) and another person lamented the “feeling of being isolated” (CS 258).

Compared to the most frequently mentioned terms, material needs (mentioned within the theme “living and property”), such as money and financial security, an organized, big and nice-looking living space, and consuming high-quality objects (e.g., a new car or high-quality clothing) are not among the most important wishes for citizen scientists in this project, but they are still mentioned by a few (9%, see Figure 1). Exemplary for the theme “living and property” is the wish by one citizen scientist for a “stylish apartment with seating outside” (CS 81). In contrast, it becomes clear that the load of unused clutter and disorder in the living space (mentioned within the theme “living and property”) burdens many of the citizen scientists that take part in the project (25%, see Figure 2). One citizen scientist, for example, reported about “mountains of stuff lying around everywhere and constricting the usable living space” (CS 28), someone else felt the “burden of inherited goods from parents and grandparents” (CS 47). Some participants explicitly want to spend less time searching for items in their household and taking care of them. Many participants indicate that they have already identified an area in which they own too many things, such as clothing, paperwork, or electronic items, they want to get rid of. Furthermore, some participants problematized current consumer society and the resulting constant temptations coaxing them into consuming more goods, that later often turn out to be mispurchases or items they do not really need. Therefore, some citizen scientists expressed the wish for less pursuit of possession.

Lastly, participants addressed issues of politics and “global development.” Primary concerns that they wish less of in life, referred to war, social inequality, climate change and waste issues as well as issues relating to global health and the pandemic (18%, see Figure 2). For instance, one citizen scientist criticized the “destruction of nature for so many unnecessary things that are manufactured” (CS 27). On the positive side within the theme of “global development” participants stated the wish for more environmental protection, peace, and social equality as well as the improvement of infrastructure in their surroundings (e.g., improvement of bike lanes) (8%, see Figure 1).

In the second reflection exercise in the project, citizen scientists were asked to reflect their possessions and think about their favorite goods in different household areas that they use and value the most and about the function the good serves for them. The questions were assigned to four separate domains in which individuals tend to accumulate the most things, clothing, stationary, kitchen items, and technology. The main interest looking at the results of this exercise was to shed light on the unique relationship people have with their goods and the reasons people decide to keep (or even accumulate) things.

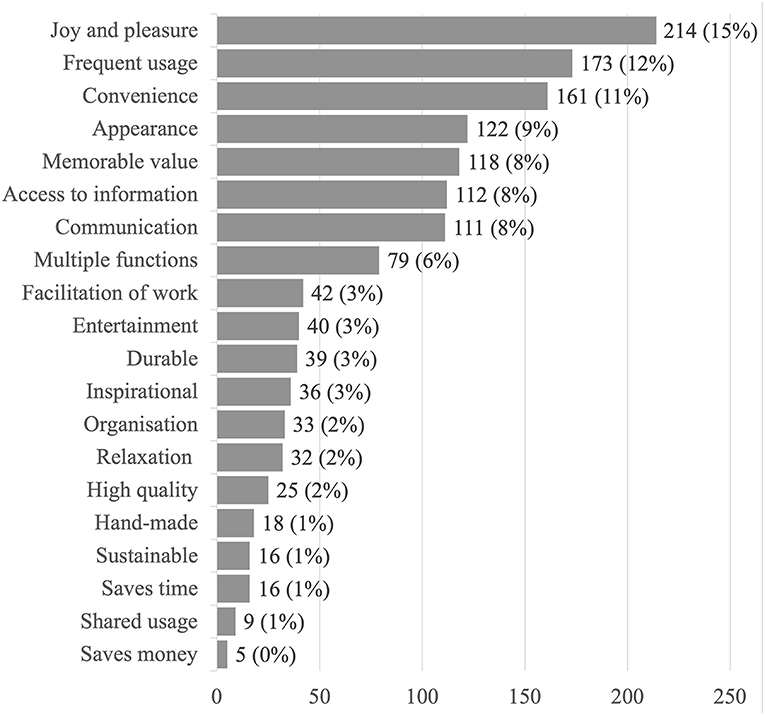

The main reasons mentioned by participants for why these goods are important to them are summarized in a graphical overview in Figure 3.

Figure 3. What makes the good important to you? (percentage refers to mentions of terms in each category in relation to the total number of mentions).

In summary, the results show, that participants often value objects because they serve a particular function or because objects have a particular trait that makes them valuable (see Figure 3). The most often mentioned functional value of goods relate to “convenience” (12%), that is goods that make everyday life more comfortable and easier. For example, people appreciate their goods because they help them simplify daily tasks such as cooking or cleaning. Further, people mention access to “information” (8%), “communication” (8%), “facilitation of work” and organization (2%), or an “entertainment” purpose (3%). Beyond the merely functional aspect, superficial or emotional properties make the goods stand out for participants. The most often stated reason for valuing goods related to goods giving “joy and pleasure” (15%). Further, some were said to have a particularly nice “appearance” (8%), some have been gifted or inherited and possess a “memorable value” (8%). Further aspects, that were mentioned less often, are displayed in Figure 3.

Discussion

These preliminary results from the ongoing research project give first indications for the discussion about potentials and limits of decluttering for sustainable consumption.

We have shown in our previous chapters that decluttering and minimalism are very much considered in the context of promoting well-being and quality of life so far (Roster et al., 2016; Hook et al., 2021; Swanson and Ferrari, 2022). Looking at selected decluttering methods (such as KonMari method), one can observe their emphasis on achieving happiness and satisfaction through decreasing the amount of material possessions (Kondo, 2014). The findings from the two workshops conducted within the project clearly demonstrate similar insights. Here, participants also associated decluttering with the hope of relief and increased well-being. This is further supported and supplemented by the results of the reflection exercises that show that people tend to not want more material goods, but rather wish for enriching relationships, fulfilling experiences and improved health and well-being in their life. Only very few mention the wish to acquire high-quality goods.

Moreover, we conceptually deduced that decluttering, on the one hand, is hardly considered in the discourse on consumer work and household work. On the other hand, decluttering is mainly communicated and marketed as a form of self-care (Ludwigsen, 2019; Ouellette, 2019; Casey and Littler, 2021), rather than work. Our results from the two workshops show that participants perceive decluttering as demanding and difficult. Participants are looking for help and support in implementing decluttering practices. Even though the participants do not explicitly refer to decluttering as work, it is nevertheless apparent from their comments that they perceive decluttering as a necessary form of effort. In addition, the results show that decluttering often requires coordination and exchange with other household members–which clearly highlights the care dimension of decluttering. Also, the perception of decluttering as a form of self-care is evident in various statements made by participants, such as when they articulate that they hope to achieve more mental freedom, peace of mind and psychological relief by decluttering.

We conceptually elaborated in our paper that decluttering can provide an opportunity to reflect on previous consumption patterns and potentially realign them in the future. Following studies on mindfulness (Frank et al., 2019; Geiger et al., 2020)–we have argued–methods used for decluttering could also be an appropriate opportunity for introspection and reflection. Looking at the empirical findings, they confirm that decluttering can be an opportune time for realignment. Participants in the project mentioned to associate negative feelings with the multitude of things they own and feel burdened by unused clutter. They have already realized for themselves that the promise of happiness through more consumption no longer works for them. Some actively problematize consumer society that constantly induces them to buy more. The second reflection exercise shed light on the reasons why people value and keep things, i.e., goods that simplify their life, enable them to get information, communicate with each other or have a specific emotional value. It can be assumed, that learning to consider the functional and emotional properties of goods in future consumption decisions, can prevent people from buying new (unnecessary) things. Whether the reflection and decluttering exercises offered in the project actually provide the desired solution and help to limit consumption, is still to be shown during the ongoing research within the citizen science project.

Although the participants of the workshop have not yet practiced decluttering methods at that point in time, they have already shown similar attitudes and perceptions as described in the study by Chamberlin and Callmer (2021). Participants showed a high awareness of the problem and expressed the willingness to change something in dealing with possessions and consumption. They felt a lot of problem pressure and were looking for practical ways to relieve it. Thus, it can be argued that participants have already taken the first step in the direction of sustainable consumption. Participants are looking for change and are interested in solutions. Accordingly, it could be assumed that it is not so much about the actual implementation of decluttering. Rather, it could be concluded that people who are interested in decluttering may be particularly open to changes in the way they deal with possessions.

The special composition of the project participants in terms of age, gender and education is on the one hand certainly related to the pre-selected communication channels used to advertise the project. On the other hand, it shows that highly educated, older women seem to have a particularly pronounced interest in the topic. The greater participation of women in the project may indicate that, overall, more women than men are interested in decluttering. This fits with the observation that women continue to do more household work than men (Moreno-Colom, 2017). Also, women seem to be particularly receptive for content about decluttering that is marketed as self-care (Ludwigsen, 2019; Ouellette, 2019; Casey and Littler, 2021). As discussed before, this bears the risk of women being pushed back into traditional roles (Ouellette, 2019). In this regard, our research contributes to current research on gender and care. Furthermore, the age of the participants seems especially interesting to us and is a fruitful complement to other research looking at the effects of clutter and decluttering in different age groups (Swanson and Ferrari, 2022). It can certainly be assumed that older people have more time to actively participate in such a research project and generally for decluttering. However, older age could also indicate that the pressure of suffering from too many possessions increases with age. On the one hand, this assumption is contrary to the results of Swanson and Ferrari (2022) that show that clutter has stronger negative effects on younger adults than on older adults. On the other hand, the following arguments seem also plausible to us: More and more things are accumulated with advancing age, which might increase the problem pressure. Furthermore, a “sandwich effect” might occur at the ages of 50 and above. While the children of the 50-year-olds slowly move out and leave many things behind in the parental household, the households of the senior parents often must be dissolved because of their moves to retirement homes or deaths. Besides, in some categories the number of accumulated things is simply so high that this age group might feel overwhelmed and in need of specific methods for decluttering. There may therefore be a particularly big need for decluttering in this age group.

Limitations and future research

As already mentioned, the results presented here are part of an ongoing research project. They will be supplemented by further qualitative and quantitative data in the near future. In particular, we will take a closer look at the effects occurring after participants used decluttering methods. While qualitative data on a population sample may not be generalizable, it does provide relevant insights into a specific sample. In this case, these are adults from Germany who voluntarily participate as citizen scientists in an online participatory project. For recruiting participants various platforms of NGOs who are active in the sustainability areas have been used. Besides, offline advertisement (e.g., using flyers and posters in the neighborhoods, etc.) was employed to attract more diverse citizens for this project. However, the researchers of this study need to highlight the fact that at the end no representative sampling could be achieved for this project. As already shown, the sample is characterized by the fact that the participants tend to be older, more highly educated and more likely to be female. Further research should therefore focus on other population groups. Regarding the gender-specific unequal distribution of housework and (self-)care, possible gender differences in the topic of decluttering should also be looked at more closely. It could also be interesting to compare different age groups in order to be able to better understand whether and to what extent perceptions of overload due to the presence of too many possessions increase with age or not.

Citizen science and transdisciplinary research always face the challenge of balancing practicality on the one hand and accuracy in the scientific approach on the other. This challenge was also evident in our project. Thus, the workshops at the start of the project were primarily intended to be enjoyable for the participants and to promote exchange. At the same time, we wanted to collect initial data on motivations and expectations. Accordingly, the data collected is not as detailed as we would have liked.

Both the workshops and the reflection exercises are based on self-reported assessments and wishes of the citizen scientists. As the citizen scientists were aware of the link between decluttering and sustainable consumption and knew the objectives of the project, it cannot be excluded that they were influenced by this in their answers. Further research could therefore contribute by looking – without knowing the research context – at problem perception before decluttering and (long-term) consumption effects after decluttering. In particular, the possible discrepancy between stated attitudes and behavioral intentions and actual behavior should be considered. This could be done in particular through participatory observation in the households.

Conclusions

This article has illustrated decluttering as being a cultural practice between household work and self-care and has discussed the potential of decluttering methods for promoting sustainable consumption. We showed that decluttering has hardly been considered in research on household work so far, although decluttering is a basic prerequisite for being able to consume continuously in view of limited spatial capacities of households. However, while the work character of decluttering is hardly mentioned, decluttering is mainly communicated as a form of self-care. The central promise is that fewer possessions contribute to greater well-being and happiness. In addition to this promise of happiness, there are other features of decluttering guides that may contribute to promoting sustainable consumption. These include, for example, simple language and a non-political framing. On the other hand, there may also be relevant risks or limits for the promotion of sustainable consumption. It can be assumed, for example, that decluttering guides promote a throwaway culture and even faster-moving consumption cycles. Empirical evidence on the effects of decluttering on sustainable consumption is still scarce. First results of a citizen science research project show that people are interested in decluttering because they feel weariness and discomfort due to the excessive accumulation of goods. This leads to the conclusion that decluttering can be a window of opportunity for people to reflect on their consumption behavior and make it more sustainable in the long term.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethics review and approval/written informed consent was not required as per local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The research on which this article is based was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Funding Program Citizen Science) under the funding codes 01BF2111B and 01BF2111C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nora Elena Borse for her great support in analyzing the data of the reflection exercises.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The project “Mein Ding-Ich bin, was ich (nicht) habe“ (My Thing-I am what I (don't) have) is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

References

Aidar, L., and Daniels, P. (2020). A critical review of voluntary simplicity: definitional inconsistencies, movement identity and direction for future research. J. Soc. Sci. 1–14. doi: 10.1080/03623319.2020.1791785

Alexander, S., and Ussher, S. (2012). The voluntary simplicity movement: a multi-national survey analysis in theoretical context. J. Consum. Cult. 12, 66–86. doi: 10.1177/1469540512444019

Baudrillard, J. (2018). “On consumer society,” in Rethinking the Subject (London: Routledge), 193–203. doi: 10.4324/9780429497643-14

Belk, R. W. (1982). Acquiring, possessing, and collecting: fundamental processes in consumer behavior. Marketing theory: Philosophy of science perspectives, 185−190.

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 15, 139–168. doi: 10.1086/209154

Biana, H. T. (2020). Philosophizing about clutter: marie kondo's the life-changing magic of tidying up. Cultura. 17, 73–86. doi: 10.3726/CUL012020.0005

Bilharz, M., and Schmitt, K. (2011). Going big with big matters. The key points approach to sustainable consumption. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society. 20, 232–235. doi: 10.14512/gaia.20.4.5

Bloodhart, B., and Swim, J. K. (2020). Sustainability and consumption: what's gender got to do with it? J. Soc. Issues. 76, 101–113. doi: 10.1111/josi.12370

Callmer, Å. (2019). Making Sense of Sufficiency: Entries, Practices and Politics. Stockholm: KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Casey, E., and Littler, J. (2021). Mrs Hinch, the rise of the cleanfluencer and the neoliberal refashioning of housework: Scouring away the crisis? Sociol. Rev. 70, 489–505. doi: 10.1177/00380261211059591

Chamberlin, L. C. J., and Callmer, Å. (2021). Spark joy and slow consumption: an empirical study of the impact of the konmari method on acquisition and wellbeing. Sustain. Environ. Res. 3, e210007. doi: 10.20900/jsr20210007

Chhetri, P., Stimson, R. J., and Western, J. (2009). Understanding the downshifting phenomenon: a case of South East Queensland, Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues. 44, 345–362. doi: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.2009.tb00152.x

Collins, R., and Stanes, E. (2021). Ambivalent storage, multi-scalar generosity, and challenges of/for everyday consumption. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2021.1975166

Cooper, T. (2005). Slower consumption reflections on product life spans and the “throwaway society”. J. Ind. Ecol. 9, 51–67. doi: 10.1162/1088198054084671

Cwerner, S. B., and Metcalfe, A. (2003). Storage and clutter: discourses and practices of order in the domestic world. J. Des. Hist. 16, 229–239. doi: 10.1093/jdh/16.3.229

Dion, D., Sabri, O., and Guillard, V. (2014). Home sweet messy home: Managing symbolic pollution. J. Consum. Res. 41, 565–589. doi: 10.1086/676922

Eichler, M. (2008). Integrating carework and housework into household work: A conceptual clarification. J. Motherhood Initiat. Res. Commun. Involv. 10, 9–19. Available online at: https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/view/16326

Etzioni, A. (1998). Voluntary simplicity: characterization, select psychological implications, and societal consequences. J. Econ. Psychol. 19, 619–643.

Etzioni, A. (1999). “Voluntary simplicity: characterization, select psychological implications, and societal consequences,” in Essays in Socio-Economics (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 1–26. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-03900-7_1

Fischer, D., and Barth, M. (2014). Key competencies for and beyond sustainable consumption an educational contribution to the debate. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society. 23, 193–200. doi: 10.14512/gaia.23.S1.7

Fischer, D., Stanszus, L., Geiger, S., Grossman, P., and Schrader, U. (2017). Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 544–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.007

Frank, P., Sundermann, A., and Fischer, D. (2019). How mindfulness training cultivates introspection and competence development for sustainable consumption. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 20, 1002–1021. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-12-2018-0239

Gaver, B., Dunne, T., and Pacenti, E. (1999). Design: cultural probes. Interactions. 6, 21–29. doi: 10.1145/291224.291235