- 1University of Amsterdam, Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Departamento de Empresa, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

- 3Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 4Department of Economics, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

There are many competing visions regarding what a circular economy transition entails and how it would transform our social, economic, environmental, technological, and political systems. This paper sheds light on these different circular discourses by asking the following research questions: what future would different circularity discourses envision for 2050? To answer this question, this paper uses scenario planning methods to explore how four circular discourses developed in a 2x2 typology of circularity thinking would imagine the future. Results examine how these four discourses would organise and operationalise circular transport, energy, agriculture, and industrial systems in 2050. Results also explore the political systems and governance processes they would establish and the type of society, culture, worldview and lifestyles they would create. Moreover, the paper analyses each scenario’s desirability (in terms of their potential to foster socio-ecological well-being) and ecological plausibility, as well as the level of societal change potentially needed to bring them about. The paper concludes that there is a real danger in following growth-based circular discourses and scenarios because their visions cannot be implemented within the biophysical boundaries of the Earth. Indeed, over 50 years of academic research have demonstrated that decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation fast enough to prevent climate breakdown and biodiversity collapse is impossible. On the other hand, degrowth-oriented approaches to circularity might shed light on circular futures that can allow all present and future generations to live a good life within the ecological boundaries of the Earth. This research recommends fostering democratic transformations such as citizen assemblies, participatory budgeting and worker-owned non-profit cooperatives as potential avenues to more inclusive, sustainable and socially just futures. This paper is thereby valuable to researchers, citizens and practitioners who seek to better understand the socio-ecological implications of different circular futures and envision desirable and viable alternatives.

1 Introduction

In the past decade, the circular economy (CE) rose from a niche concept in the sustainable production and consumption literature to become a major component of any business, government, or civil society discourse on sustainability (Deutz et al., 2024). A Google search for “circular economy” in 2012 would lead to around 80 thousand results; the same search now leads to over 80 million. However, the CE is nothing new; the metaphor of a circle to represent a sustainable economy has existed at least since the 1970s with Barry Commoner’s magnum opus, “The Closing Circle” (Commoner, 1971). The idea of a society that works in harmony with the natural cycles of the Earth can be traced even further back to the ancestral worldviews and ways of life of Indigenous peoples throughout the globe (Kothari et al., 2019). The current definition and forms of implementation of CE are very diverse and still very much contested, with many different actors proposing different visions and discourses of CE, depending on their socio-economic perspectives and interests (Korhonen et al., 2018b; Repo et al., 2018; Vermeulen et al., 2024).

While some CE futures, discourses, and narratives have been explored and analysed by academic literature (e.g., Bauwens et al., 2020; Calisto Friant et al., 2020; Leipold et al., 2023; Marjamaa and Mäkelä, 2022; Yalçın et al., 2023), there is a lack of research visioning how different visions of CE may play out in the future. This is particularly problematic as visioning and futuring can enable us to better understand and address the multidimensional and interrelated social, technological, political, and economic implications of a CE transition. It can thus help academics and practitioners better comprehend the diversity of potential circular futures that exist and how desirable alternatives might be democratically chosen and fostered. Moreover, futuring is also a performative act (Oomen et al., 2022); by visioning different circular futures and exploring their socio-ecological implications, we are contributing to building the academic and societal discourse on circularity and fostering a more comprehensive understanding of what different circular discourses and visions entail.

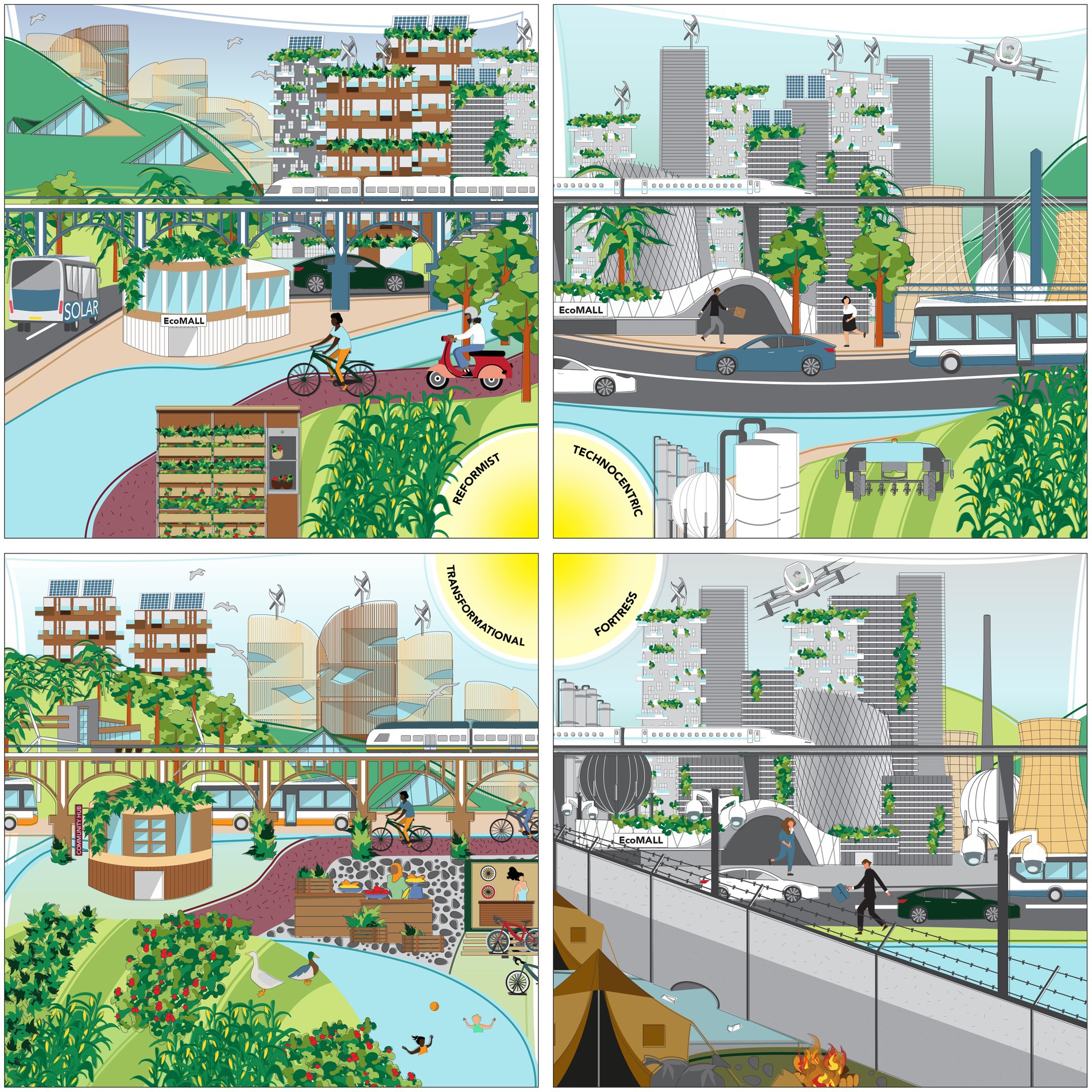

This paper seeks to shed light on different circular futures and scenarios by asking the following research questions: what future would different circularity discourses envision for 2050? To answer this question, this paper unpacks the four circular discourses developed by Calisto Friant et al. (2020) to explore how these different approaches to circularity imagine the future. It does so by following scenario planning methods from future studies literature to explore what these four competing circularity discourses propose for the future of our transport, energy, agriculture, industry, social, cultural, and political systems. The paper also analyses the desirability of each scenario in terms of their potential to foster socio-ecological well-being, as well as their ecological plausibility and the level of societal change potentially needed to bring them about. In addition to this, a collaboration with an artist led to the illustration of images that visually represent the futures that each of the four discourse types envisions by 2050.

This paper is thus the result of a “futuring” thought experiment, where we unpack and draw out four circular discourses into the near future and critically engage with their sustainability implications. This paper can help academics and practitioners better understand the different visions of circularity competing in the discursive debate and better grasp their key implications for human planetary well-being.

After explaining the methods and conceptual framework (section 2), the article explores the four possible futures that each of these discourse types would envision by 2050 (section 3). Section 4 investigates which of these visions currently dominates the discursive debate on CE and discusses the sustainability implications of each of these futures. We conclude with final reflections and avenues for further research.

2 Methods and conceptual framework

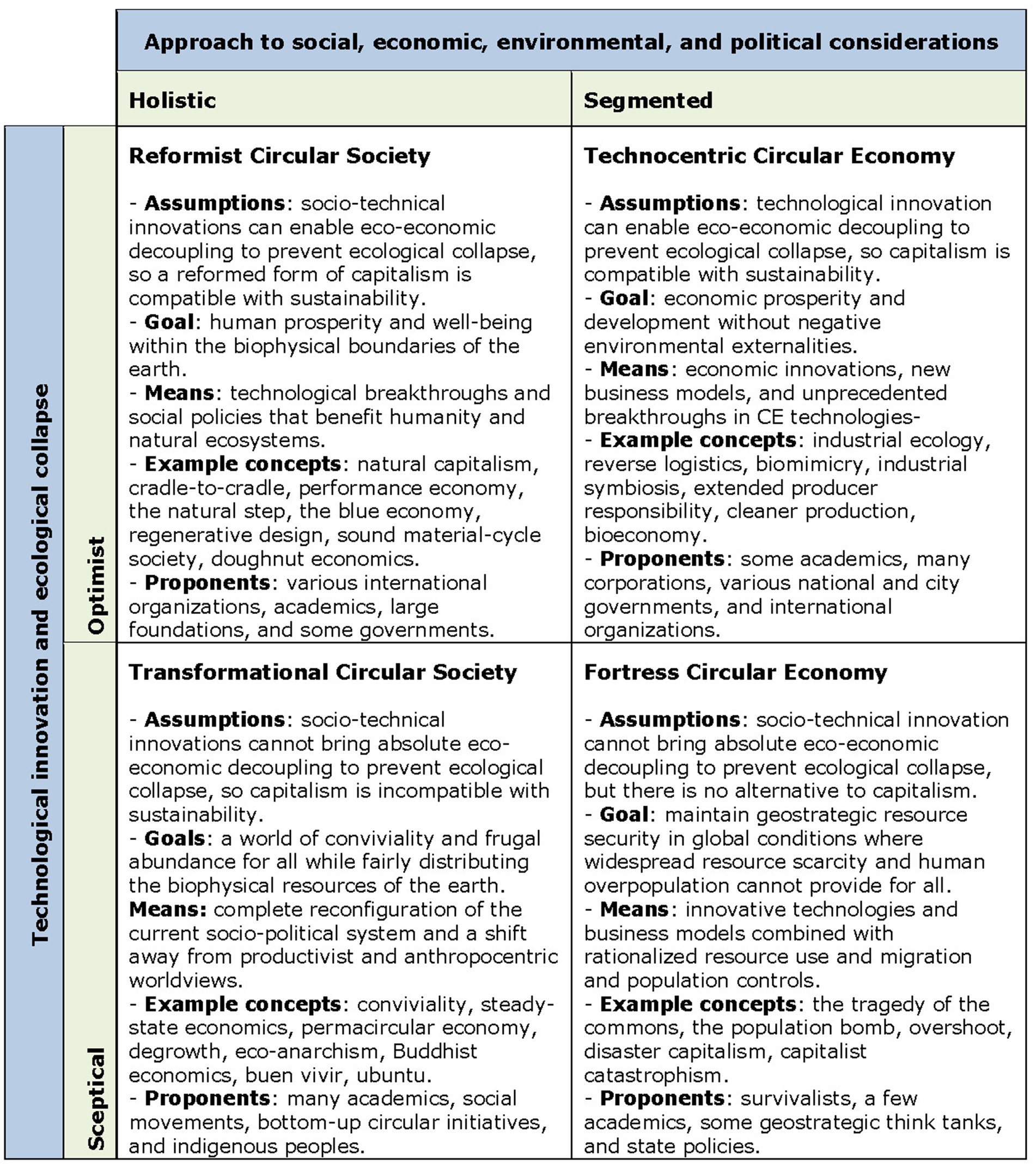

The typology of circularity discourses developed by Calisto Friant et al. (2020) was chosen as the conceptual framework for this article as it is a typology that has been widely used by other academics for discourse and policy analysis on the topic (e.g., Arai et al., 2023; Melles, 2021; Ortega Alvarado et al., 2021; Palm et al., 2021). The framework is based on a comprehensive literature review of CE and all its related concepts, including both ideas from the Global North and South. It is thus a broad and plural typology that embraces many different approaches to the topic. It is particularly useful to this paper’s research aims, as the typology can help us envision the complexity and diversity of futures that different CE proposals entail. It can thereby serve as the foundation to build 4 potential CE scenarios for 2050, which are based on current divergent discourses, vision, assumptions, and propositions for a CE transition.

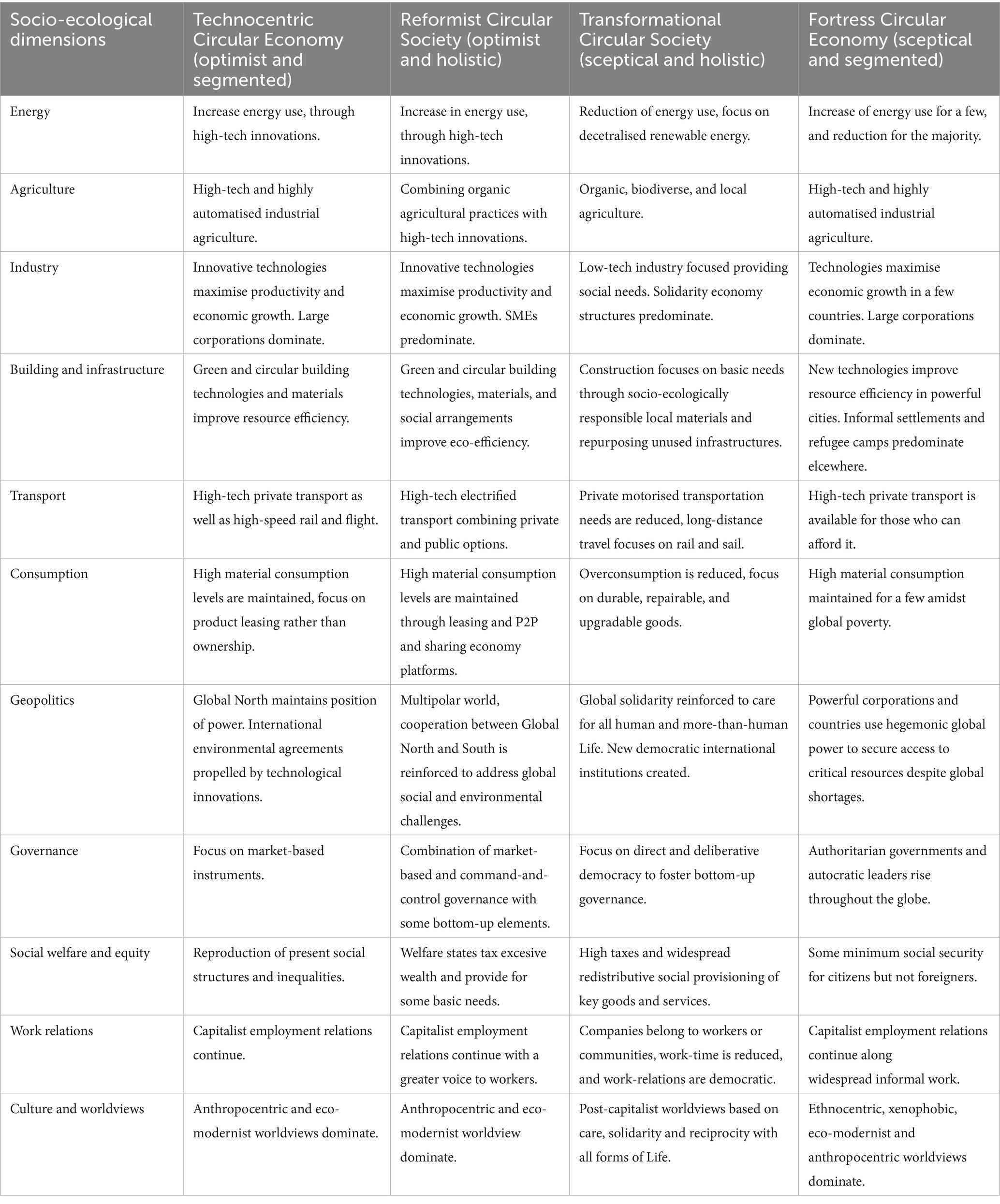

The 2×2 typology differentiates CE discourses based on two criteria. First, whether discourses are optimist or sceptical regarding the possibility that economic growth can be decoupled from environmental degradation fast enough to prevent a socio-ecological collapse (eco-economic decoupling). Second, whether discourses are holistic by including social justice and political empowerment considerations or segmented by focusing on resource efficiency alone. This differentiation leads to 4 broad circularity discourse types: Technocentric Circular Economy (optimist and segmented), Reformist Circular Society (optimist and holistic), Transformational Circular Society (sceptical and holistic), and Fortress Circular Economy (sceptical and segmented) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Circularity discourse typology (adapted from Calisto Friant et al., 2020).

To develop each scenario, this paper follows the scenario planning methods from future studies literature (Bengston, 2019; Börjeson et al., 2006; Polak, 1973) by engaging in an act of open imagination about what different CE futures might bring about. To do so, this paper takes the four circular discourse types presented earlier as the starting point and asks what future would different circularity discourses envision for 2050.

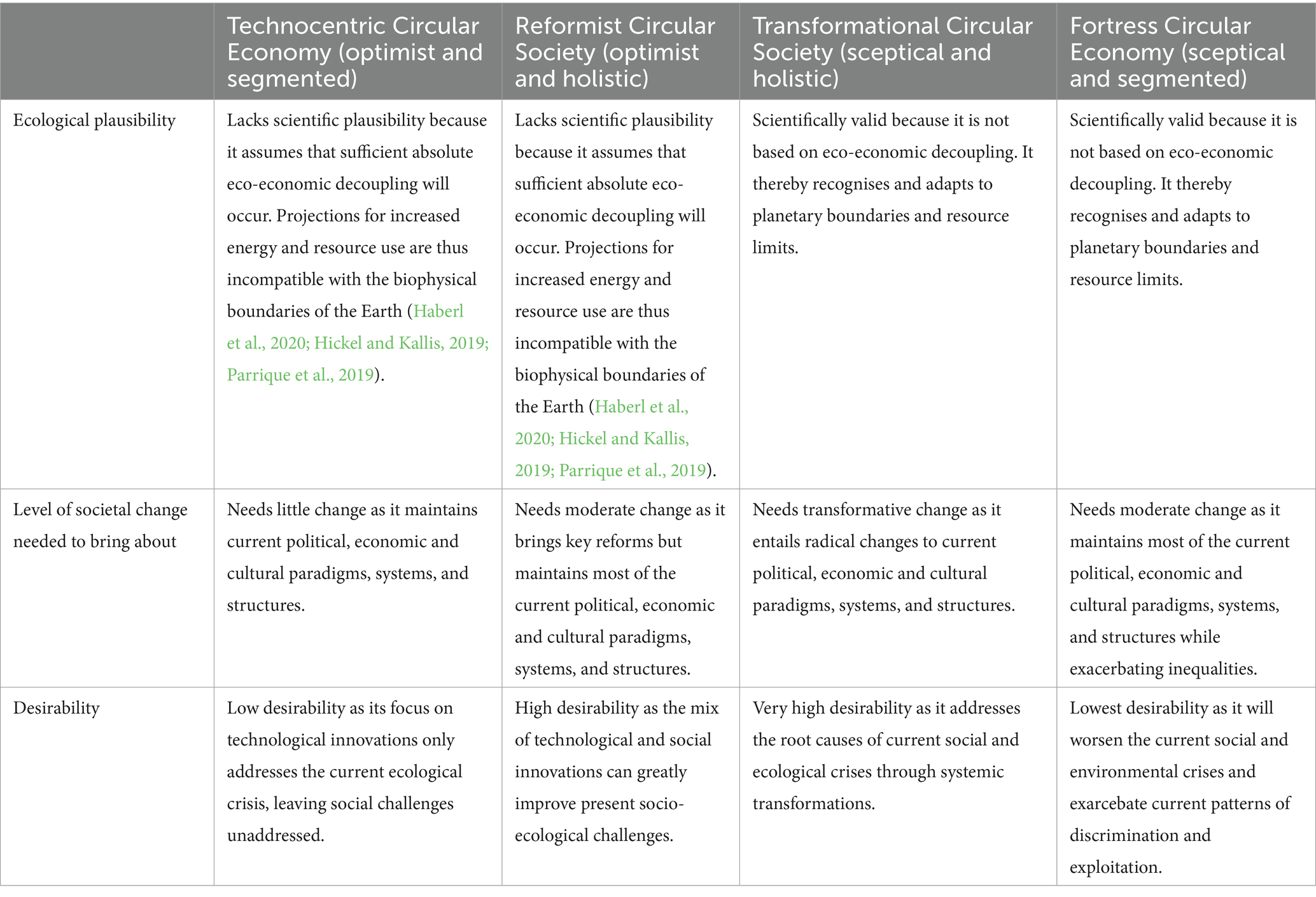

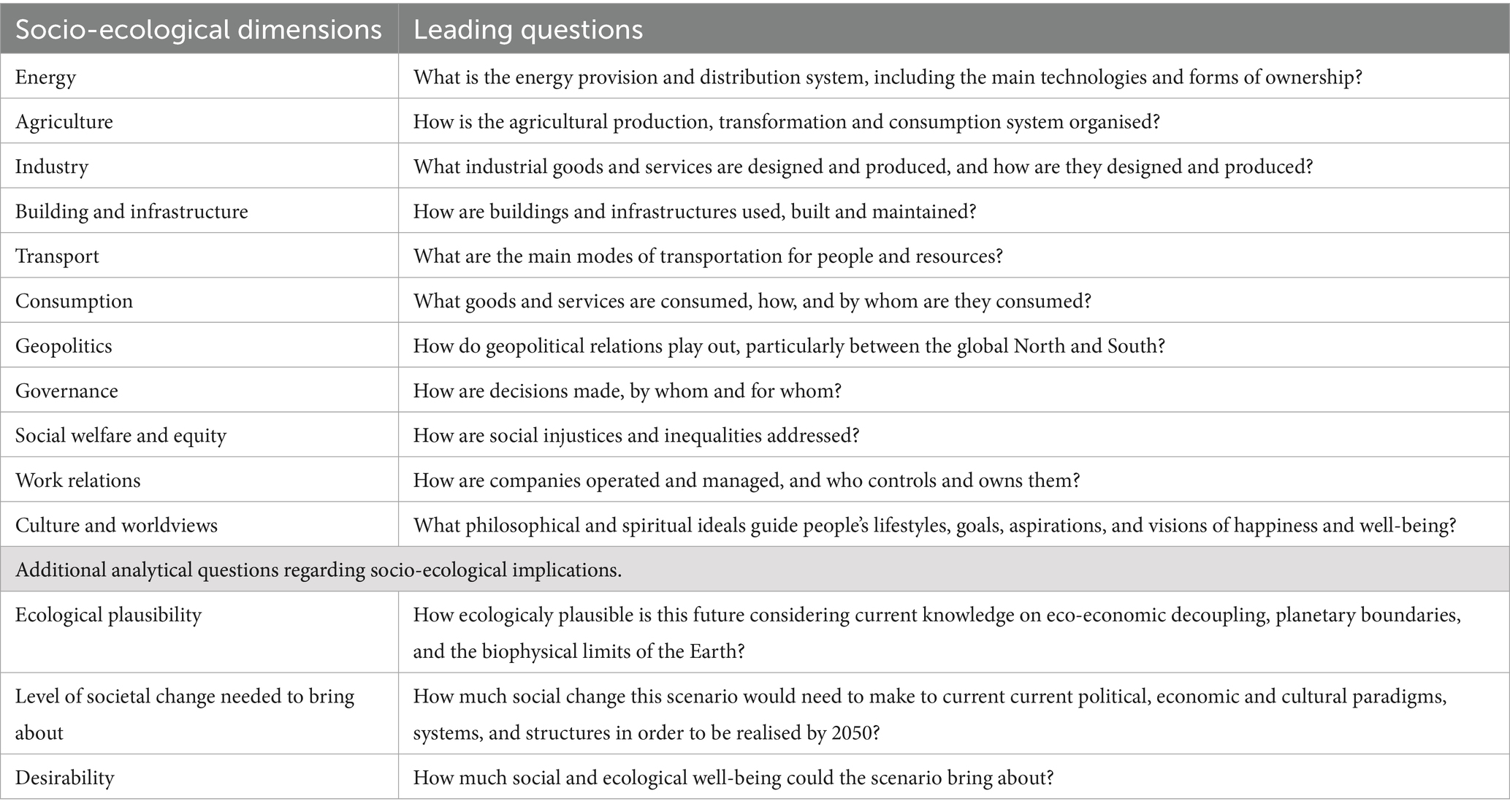

To help imagine and develop each scenario, a set of 11 dimensions was established to have a list of essential features that should be conceptualised for each CE future (see Table 1). This list was developed by the authors in an iterative process while building each scenario and was used to help structure the analysis and the construction of each scenario. This list includes key questions on the future political, social, cultural, economic and technological systems that should be imagined within each scenario and thereby ensures that the four scenarios incorporate the full complexity of a CE transition and its multiple, interrelated and interconnected socio-ecological components. While creating these 11 dimensions, the authors focused on having a comprehensive set of questions and components that would enable holistic and systemic development of each future scenario.

Table 1. Essential socio-ecological dimensions and questions considered in the development and analysis of each scenario.

In addition to this, three analytical questions were added regarding the ecological plausibility and level of societal change potentially needed to bring about each scenario as well as their socio-ecological desirability. Since the latter do not relate to the actual vision of the future that is proposed by each discourse type but rather bring a critical analytical lens regarding their social implications, they will be addressed and explored in the discussion rather than the results section.

While developing the 4 future scenarios, the authors drew inspiration from literature on the typology and its application in various contexts. This helped obtain an in-depth understanding of each discourse type and how it is presently implemented and conceptualised. The reviewed literature includes works applying typology (e.g., Arai et al., 2023; Hermann et al., 2022; Palm et al., 2021) and literature on the various concepts related to each circular discourse type (e.g., Felber, 2015; Kothari et al., 2014; Latouche, 2009). To complement this, we also drew inspiration from past literature on circular futures, discourses, and narratives (e.g., Bauwens et al., 2020; Leipold et al., 2023; Yalçın et al., 2023), as well as research proposing alternative visions of a sustainable circular economy and/or society (e.g., Calisto Friant et al., 2024; Genovese and Pansera, 2021; Suárez-Eiroa et al., 2021). This review helped in the conceptualisation of each discourse type and the understanding of how they would imagine the future in 2050.

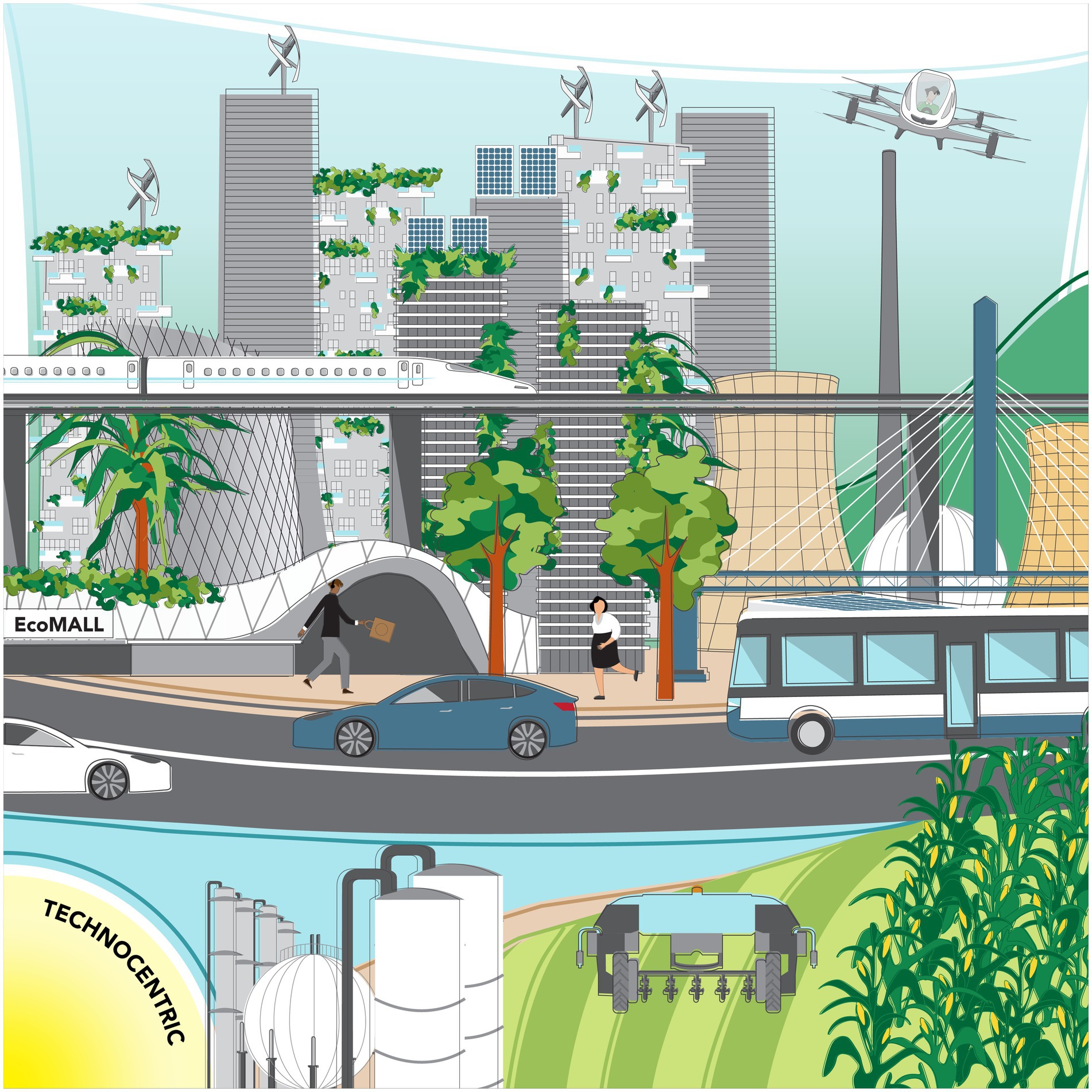

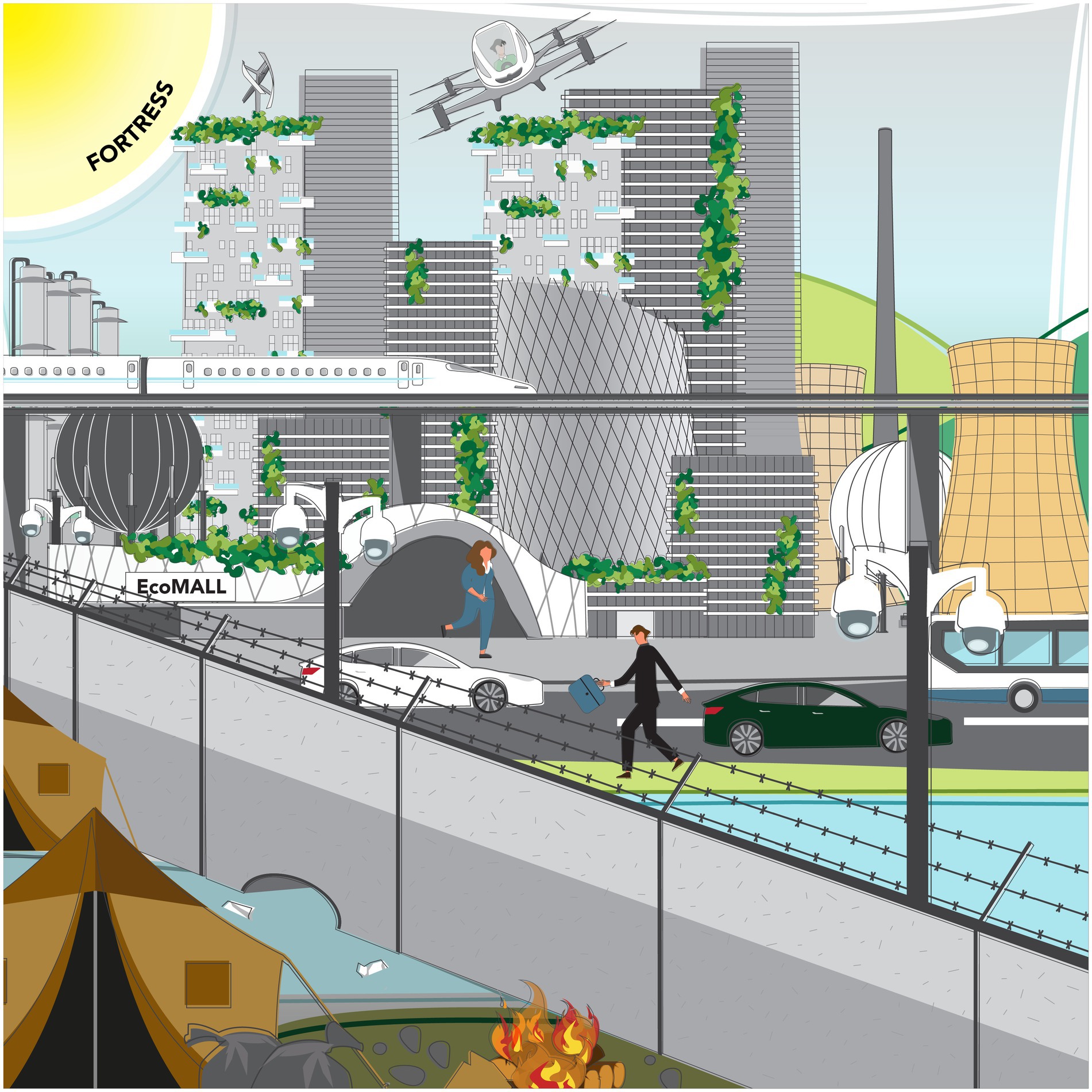

Moreover, the authors developed a visual representation of the four discourse types and their proposed futures by working with an artist and designer, Anke Muijsers. Through a series of collaborative sketching exercises, we drew out an illustration of each of these futures (see Figures 2–6). This involved the elaboration and revision of various drafts with the authors and the designer until the final visions included key defining characteristics of each discourse type. The authors particularly focused on detailing the different mix of agricultural, industrial, housing, energy, consumption, and transport systems each of these 4 different discourses would imagine for 2050. For example, they all showcase a different mix of transport systems, with some focusing on public and active transport, others on high-tech private transport, and others on a mix of these. While building them, we sought to create visual representations that are both complete and comprehensive, as well as clear, simple, and easy to understand, so they could be used as educational and workshop materials for citizens, researchers, practitioners, students, and other actors. They complement the article by showcasing the type of future and socio-economic system that each circularity discourse type imagines for 2050. Moreover, the sketching exercises helped the authors explore and develop the description of each future scenario, as they enabled key reflections and debates on the future of CE to emerge.

Figure 2. Visual representation of the circularity discourse typology (Calisto Friant, 2022).

Figure 3. Visual representation of a Technocentric Circular Economy future (Calisto Friant, 2022).

Figure 4. Visual representation of a Reformist Circular Society future (Calisto Friant, 2022).

Figure 5. Visual representation of a Transformational Circular Society future (Calisto Friant, 2022).

Figure 6. Visual representation of a Fortress Circular Economy future (Calisto Friant, 2022).

Each scenario developed in this paper is ultimately a thought experiment that not only builds on the abovementioned methods but also on over 6 years of readings, reflections and discussions on CE between the authors and countless other people. They are, hence, inevitably subjective and biased projections regarding how the future may play out. They are neither models nor predictions of the future but rather open explorations of what different circular discourses propose, what type of society they might engender, and what the socio-ecological implications of these futures might be. The resulting future visions thus best serve as starting points for further discussions on the potential sustainability and social justice impacts of different circular economy discourses and what kind of future we would like to foster.

3 Results: four different visions of a circular future

This section describes the 4 scenarios developed by the authors, exploring how each of the 4 circularity discourses presented in the previous section would envision the future and what this would entail for the 11 dimensions outlined in Table 1. Figure 2 presents four illustrations of these scenarios developed through the sketching exercise, which complements the description of the four futures. The following sub-sections will describe and explore each one of these in detail.

3.1 The Technocentric Circular Economy future

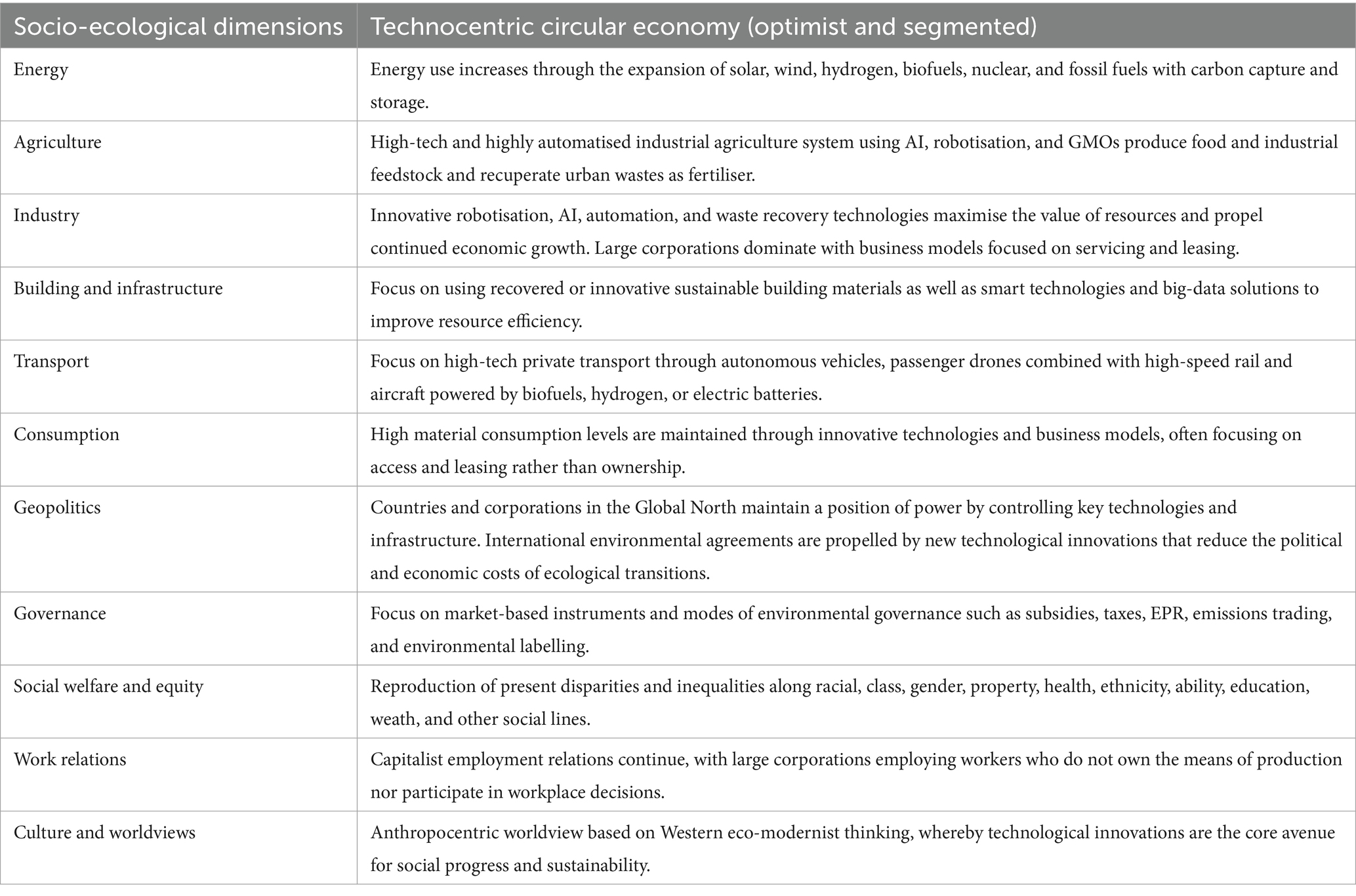

Technocentric Circular Economy (TCE) discourses are optimist about the capacity of technology to prevent socio-ecological collapse and are segmented as they do not include social justice and political empowerment considerations (see Figure 3 and Table 2). These discourses seek to reconcile economic development with ecological sustainability through innovative business models and technological breakthroughs, especially in resource recovery, biotechnology, and renewable energy.

In a TCE future, industrial output and energy production continue to grow by using many different sources of energy, including solar panels, wind turbines, hydrogen, biofuels, nuclear, and even fossil fuels when combined with carbon-capture and storage technologyies.

Agriculture is highly efficient and automatised and uses artificial intelligence (AI), robotisation, biotech and genetically modified organisms (GMOs) to increase resilience and productivity. This industrial agriculture system thereby supplies food for human consumption and as industrial feedstock to produce biofuels and advanced biomaterials (such as bioplastics), all while recuperating organic wastes from urban areas through bio-digestion and waste-water recycling.

Transport systems include high-tech innovations such as autonomous vehicles, high-speed rail, and passenger drones, as well as green aircraft powered by biofuels, hydrogen, or electric batteries. Buildings are made from recovered or innovative sustainable materials and are packed with smart technologies, which allow energy-efficient housing, malls, and offices to rise surrounded by green walls, wind turbines and solar panels.

New recovery technologies and businesses flourish in this society, with myriad innovations to recycle all types of waste and repair, remanufacture or refurbish disused products. Many industries switch from selling specific goods like cars, smartphones, and washing machines to providing services like transportation, cleaning, lighting, or computing (so-called product-service systems). Automation, machine learning, and robotisation greatly enhance the quality and efficiency of industrial processes, from extraction to production, use, and recovery, and they enable innovative forms of remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling. Industries also start producing closer to consumption markets. This allows new forms of symbiosis between and within urban and industrial clusters, whereby wastes from production or consumption processes are recuperated to manufacture new products.

TCE visions do not address socio-political considerations, so current capitalist, modernist and anthropocentric social relations, worldviews, and working practices remain broadly unchanged. Socially and geopolitically, it is thus a future that is not too different from the present, with its winners and its losers. Present inequalities thus persist along different social lines such as class, race, ethnicity, gender, ability, origin, education etc. Large international corporations continue to dominate the economic system as they control the patents, data, and infrastructure related to key technologies (particularly in IA, robotisation, renewable energy, automation, and biotechnology). Moreover, powerful countries from the Global North, where these corporations are often based, are able to maintain their geopolitical power by controlling and investing in these new technologies.

International agreements on climate change and other global environmental challenges are expected to be concluded thanks to the rise of new technologies, which make renewable energy and clean production practices cheaper. Technological transformations are thus seen as the key drivers that make both international and local agreements on ecological matters politically possible. This also means that governance of CE transformations is generally left to market-based instruments and modes of environmental governance. Subsidies, taxes, emissions trading schemes, extended producer responsibility systems (EPR), and environmental labelling requirements are thus prioritised to nudge the adoption of new technologies.

Culturally, Western eco-modernist visions of progress continue to dominate. Anthropocentric worldviews, which see humans as separate and superior to nature, thus fuel a future where technological change, efficiency and productivism are the core means to social prosperity and environmental sustainability.

3.2 The Reformist Circular Society future

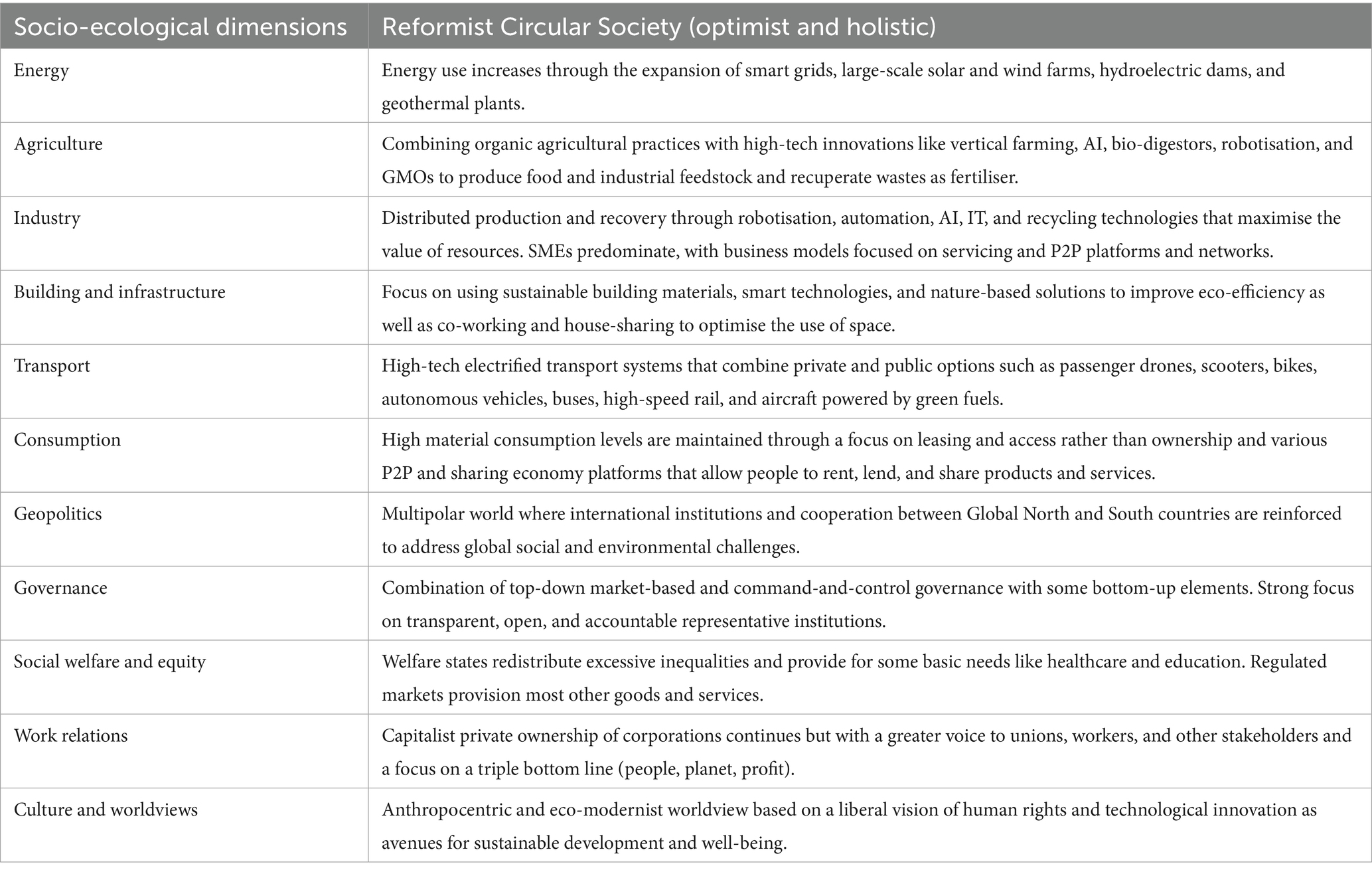

Reformist Circular Society (RCS) discourses are optimist about the capacity of technology to prevent socio-ecological collapse and holistic as they integrate many social justice and political empowerment considerations (see Figure 4 and Table 3). These discourses seek to create a sustainable circular future through a combination of innovative business models, social policies, and technological breakthroughs. RCS visions thus add a social justice lens to the many technical and business innovations of TCE visions.

An RCS society combines high-tech innovations and industrial processes with greater care for workers’ well-being and respect for human rights. It is a society where technology has brought nature closer to humans with a myriad of nature-based solutions like green walls and parks that mitigate heat waves and floods. It is a future where industrial processes operate like natural ecosystems, sharing resources between localised manufacturing hubs and cities to continuously re-use wastes for the production of new goods. Innovative technologies like robotisation, 3D printing, chemical recycling, big data, and AI enable the re-localisation of industrial processes and the mining of urban areas for secondary materials. This is all powered by abundant renewable energy from large-scale solar and wind farms, hydroelectric dams, and geothermal plants. This smart energy grid also provides power for an electrified transport system combining high-speed rail, autonomous vehicles, and passenger drones with electric scooters, buses, bikes, and aeroplanes.

Buildings are constructed with recovered resources and sustainable bio-sourced materials. Urban spaces are optimised, renovated, insulated, and greened as much as possible. The need for offices and housing is reduced thanks to co-working and house-sharing platforms. A myriad of sharing economy activities emerge thanks to new information technology (IT) and peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms enabling people to rent, lend, and share tools, knowledge, work, cars, bikes, resources, and much more. In this distributed and networked economy, people become less inclined to own products and rather seek access to their transportation, cleaning, computing and other needs. Companies thereby switch from selling goods to providing product-service systems.

Agriculture systems are also transformed by combining organic agricultural practices with high-tech innovations like vertical farming, aquaponics, hydroponics, autonomous tractors, and genetic engineering. This enables the provision of diverse diets of fresh produce for humans, the production of biofuels for energy use, and the supply of biomaterials for industrial applications (such as bioplastics). Moreover, bio-digestors and waste-water recovery systems enable the efficient re-utilisation of urban organic waste as fertilisers.

Environmental governance operates through a mix of top-down market-based mechanisms and command-and-control instruments. In addition, some bottom-up participatory mechanisms are encouraged (such as participatory budgeting), and transparent, open, and accountable representative institutions are fostered to ensure “good governance.” Collaboration between private, public, and civil society organisations is thus at the heart of the CE transition.

International organisations are empowered to address global sustainability challenges such as climate change, poverty reduction, and biodiversity protection. Geopolitical cooperation between Global North and South countries is hence strengthened to foster a more balanced and multipolar international system.

Privately owned corporations and capitalist market structures continue to dominate the provision of most goods and services. However, a greater voice is given to unions, workers, and stakeholders on business boards. A triple bottom line of profit, planet, and people thus guide corporations and help create more socially and environmentally responsible business models. Moreover, government regulation and intervention are seen as essential to ensure the well-functioning of markets, prevent monopolies, and support SMEs. The welfare state is thereby reinforced to redistribute excessive inequalities while ensuring access to some basic services, such as education, healthcare, and social security.

Culturally, anthropocentric, eco-modernist and liberal worldviews predominate and guide social practices. Socio-technical innovation, economic prosperity, and human rights are thus seen as the avenues to achieve sustainable development and well-being.

3.3 The Transformational Circular Society future

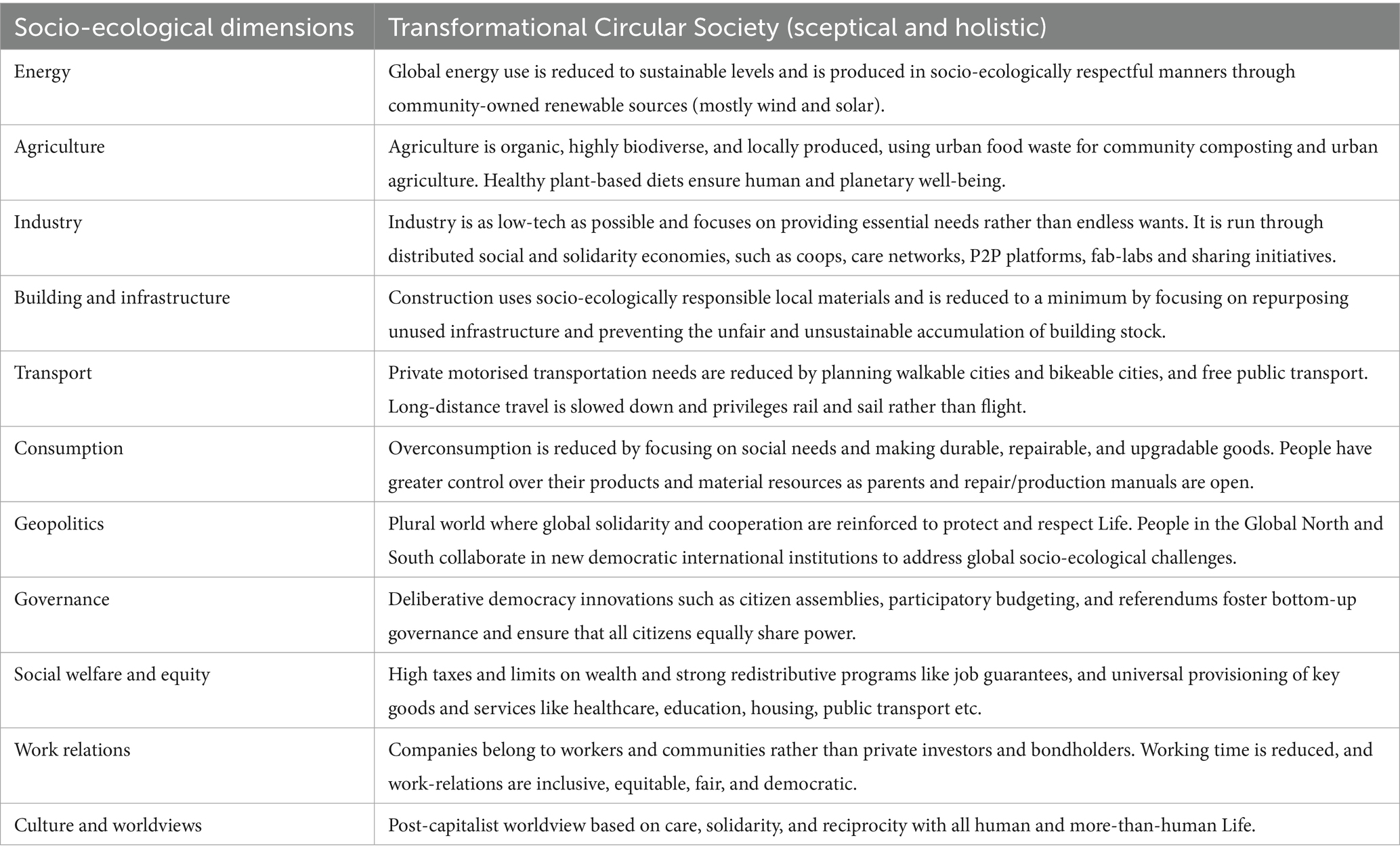

Transformational Circular Society (TCS) discourses are sceptical about the capacity of technology to prevent socio-ecological collapse and holistic as they integrate social justice and political empowerment considerations (see Figure 5 and Table 4). These discourses seek to create a fair, democratic, de-colonial, and sustainable post-capitalist future by re-localising and redistributing power, wealth, and knowledge.

It is a future where industry belongs to workers, democratic public institutions, and communities rather than private investors and bondholders. Profit motives and endless economic growth imperatives thus no longer dictate economic and political decisions. It is a society where power is equally shared, thanks to a plurality of deliberative democracy innovations such as citizen assemblies of randomly selected citizens, participatory budgeting processes, referendums, and citizen initiatives. It is an economy that redistributes wealth and resources from those who have the most to those who have the least, thanks to high taxes on wealth and a diversity of social justice programs like job guarantees, universal healthcare, public childcare, free education, abundant social housing, social security, and universal basic income and services etc.

The economy is run through social and solidarity economy practices of care, reciprocity, and solidarity and linked through non-profit P2P networks. There is, hence, an abundance of economic and social initiatives that care for human and more than-human Life, such as repair cafés, community gardening, fab-labs, cooperative firms, support groups, sharing initiatives, convivial biodiversity conservation and ecosystem regeneration projects, etc. Working time is reduced to allow people to be involved in all the above community activities or any personal, artistic, spiritual, relational, or family project. Productive work, personal achievement and competition are no longer the foremost goals in Life, allowing for slower, more meaningful, and convivial forms of existence. Moreover, sufficiency and well-being through non-material aspirations replace the endless race for more things and more money. Citizens thereby gain a renewed sense of freedom and control over their time and the meaning they wish to give to their lives.

Industrial and manufacturing systems are as low-tech as possible and focus on providing for key social needs rather than endless artificial wants. Open-source technologies like 3D printing, P2P networks, and free software allow the creation of distributed economies, where ideas and innovations are openly shared, adapted and upgraded and can be autonomously produced anywhere. Products are highly durable, easily repairable, and upgradable. Patents and product manuals are open and free to facilitate modularity and innovation. People hence partake in a plurality of do-it-yourself production, repair, repurpose and upgrade activities that give them tangible control over their products and resources.

Global energy use is reduced to sustainable levels for the biosphere and is shared to ensure enough energy is available for everyone. Moreover, energy is produced in a socio-ecologically respectful manner thanks to decentralised energy grids of community-owned renewable sources like wind turbines, geothermal plants, and solar panels.

All agriculture is organic, highly biodiverse, and as local as possible, utilising urban food waste for community composting and urban agriculture. Cooking and food preparation are cherished activities, with deep care and appreciation for diverse, seasonal, healthy, plant-based ingredients that ensure human and planetary well-being.

Transportation needs are reduced as much as possible by planning inclusive walkable cities with easy access to local goods and services, thanks to accessible sidewalks, bike lanes, flourishing green spaces, and free public transport. This leads to convivial cities and neighbourhoods with access to local markets, parks, communal spaces, gardens, and public services for everyone, regardless of class, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, race, (dis)ability or age. Long-distance travel is reduced to a minimum, and when necessary, it happens by train or sailboat and supports community tourism that respects local cultures and ecosystems.

The construction of additional buildings is reduced to a minimum by focusing instead on repurposing unused or under-used buildings and preventing the unfair and unsustainable accumulation of building stock. When infrastructure construction is necessary to meet social needs, it focuses on using local materials and socio-ecologically responsible building practices. Biodiversity is cherished by protecting ecosystems, prioritising green infrastructure, and replacing unnecessary parking, roads and highways with green belts and roofs.

Global cooperation and solidarity are fostered and reinforced through the democratisation of international institutions like the UN and the creation of new organisations to democratically and inclusively manage planetary commons. Countries in the Global North open their borders and support the Global South through new forms of technology transfer, financial aid, and technical assistance. There is a shared feeling of common belonging and responsibility for Life on Earth beyond cultural differences and ethnocentric and anthropocentric ideas. This creates a pluriversal world where all forms of Life are seen as sacred, and nature is given internationally recognised rights. Global social and environmental challenges like climate change, poverty, inequality and biodiversity loss are thus addressed with deep recognition of past responsibilities and injustices.

3.4 The Fortress Circular Economy future

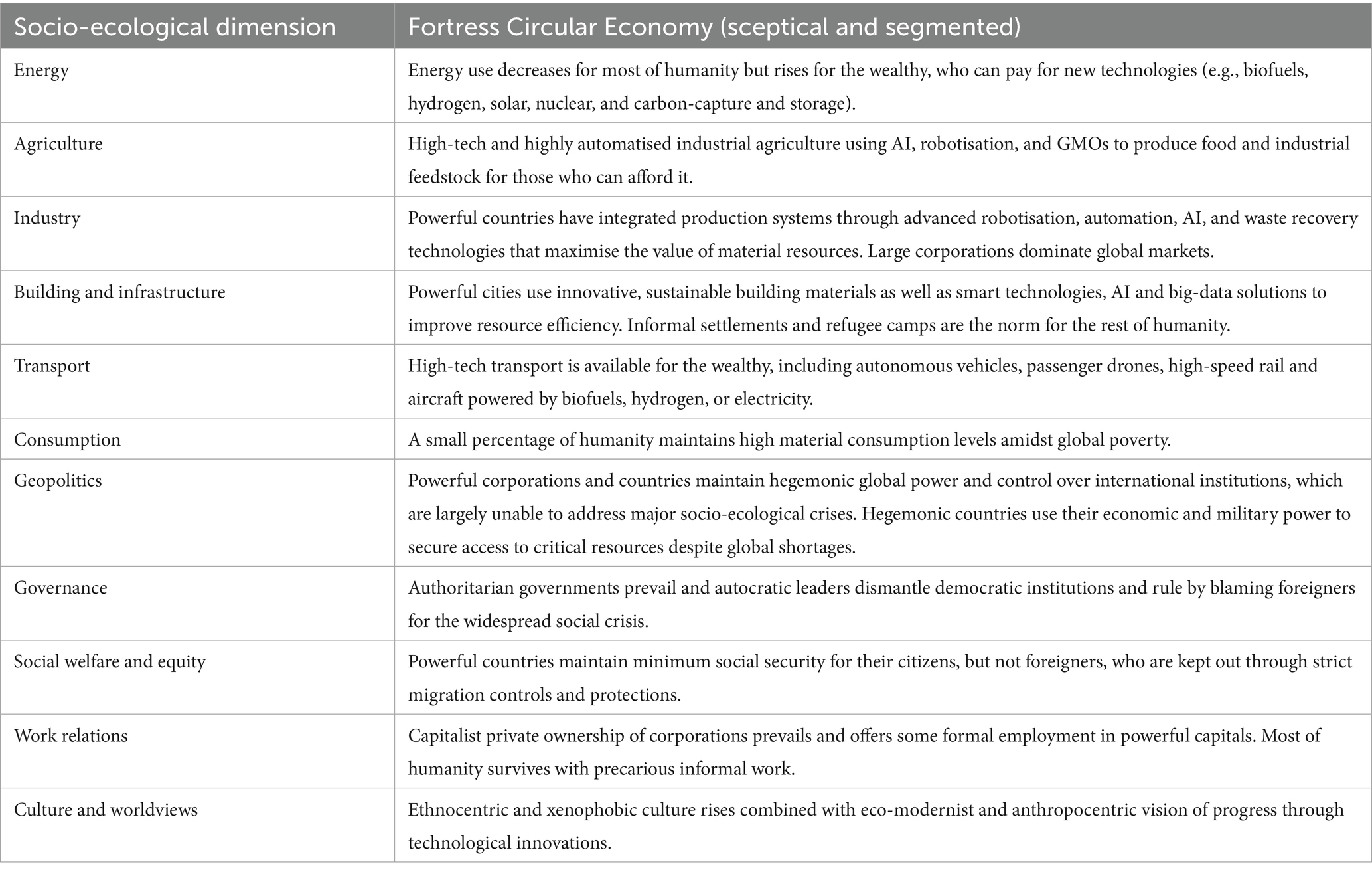

Fortress Circular Economy (FCE) discourses are sceptical about the capacity of technology to prevent socio-ecological collapse and segmented as they do not include social justice and political empowerment considerations (see Figure 6 and Table 5). They describe a future in which biophysical stability is severely weakened and geostrategic resource security is sought through technological innovations and top-down controls on people and resources. FCE discourses are concerned about the tangible shortages caused by overpopulation and the overconsumption of natural resources. Yet, instead of envisioning a utopic vision to solve these socio-ecological challenges and prevent planetary overshoot, they see climate breakdown and ecological collapse as inevitable due to the entrenched nature of capitalist power relations and a generally negative vision of human nature. Therefore, rather than attempting to describe the world as it should be, FCE discourses focus on describing the world as it will most likely be if current unsustainable socio-ecological trends continue.

FCE discourses thus see a future where people seek to protect themselves and maintain access to resources despite the surrounding collapse. Protection from mass climate-induced migration is intensified with heavy security apparatuses such as militarised frontiers, surveillance, policing and migration controls. Military and economic domination and coercion are used to secure access to critical resources and build high-tech industrial societies. Minerals for wind turbines and solar panels, uranium for nuclear power plants, and land for bio-fuels are thus obtained throughout the globe by some countries despite global shortages that prevent others from accessing these resources. The conservation of specific ecosystems is imposed by some countries through military and police power, often displacing Indigenous peoples living there. This secures ecosystem services for some privileged citizens while excluding others.

The above neo-colonial and imperial practices create islands of material wealth and abundance amidst a sea of shortages and scarcity. It allows some societies to maintain high-speed rail networks, autonomous vehicles, passenger drones and malls filled with consumer goods for the wealthy few. Climate engineering, autonomous tractors, AI, GMOs, and biotechnology maintain a limited supply of foods and industrial feedstock for those who can pay the price. Water scarcity and pollution are rampant due to constant droughts, floods, and heatwaves, but new water-saving, decontamination and desalination technologies provide water access for those who can afford them.

The most powerful countries and cities have highly efficient and interconnected buildings and urban systems thanks to big data, AI, and the internet of things, which ensure the effective use of limited resources. Innovative recovery technologies and strong integration between powerful consumption and production centres ensure the efficient recovery, remanufacture, refurbishment, and recycling of waste materials. Some nations use high-tech robotisation, automatisation, bioengineering, and machine learning technologies to create eco-industrial systems with optimum labour, energy, and material efficiency. However, these industrial tools and resources remain inaccessible to most of the Earth’s population. In fact, for most of humanity, informal settlements are the norm, and people undertake multiple informal activities (such as waste picking and scavenging) to make a living due to widespread job scarcity. Moreover, refugee camps are set up all over the world due to widespread climate change impacts and climate-induced migrations.

In an FCE future, current disparities along racial, class, gender, property, health, ethnic other social lines are reinforced and exacerbated as those with historical power are able to maintain access to the limited resources that remain. Powerful multinational corporations and countries thereby replicate their hegemonic position through their control of critical technologies, infrastructures and resources. This allows a minority of people in a few countries to secure a relative material abundance amidst a heavily degraded planetary system with strong resource constraints for most of humanity. It is a future where circularity and sustainability exist only for those who can afford it, while imposed sufficiency is the reality for everyone else.

In these conditions, authoritarian leaders become increasingly popular. They often use racist and xenophobic discourses to blame foreigners for the widespread social and economic issues that people face. As far-right populists rise to power, democratic institutions are severely weakened throughout the globe. This climate of fear, climate breakdown and resource shortages leads to increasing international tensions, conflicts and even wars. Moreover, global treaties and international institutions merely replicate unequal power relations and are largely unable to prevent conflicts and address crucial socio-environmental challenges. An FCE future is thus a world where socio-ecological crisis has become the new normal.

4 Discussion

The 4 circular futures explored in this paper help understand the core differences between circularity discourses and the potential future they seek to create (see Table 6 with a summary of each scenario). Of the four resulting futures, the TCE and RCS futures represent the “business as usual” scenarios, which require the least societal change to bring about (see Table 7). However, they lack ecological plausibility as they are based on continuing economic growth despite mounting evidence that decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation fast enough to prevent climate breakdown and biodiversity collapse is not happening nor likely to ever happen due to the intrinsic relationship between natural resource use and GDP (Haberl et al., 2020; Hickel and Kallis, 2019; Jackson, 2016; Parrique et al., 2019; Wiedenhofer et al., 2020). The FCE scenario is ecologicaly plausible and will not bring about much change to current social structures except for an exacerbation of present patterns of exploitation. It is thus highly undesirable as it is a future characterised by widespread resource shortages and social injustices. The final scenario, TCS, is ecologicaly plausible as it envisions a post-capitalist system that can operate without economic growth and is also highly desirable as it could bring about the greatest improvements to social and planetary well-being. However, it is the one that requires the greatest social transformations to our current socio-political systems to bring about. It is thus hard to envision how such a scenario could become reality by 2050 as it requires nothing short of a widespread global revolution.

The above analysis helps us understand the strengths and weaknesses of each scenario. RCS and TCE visions may place too much hope on technological innovations and economic growth to improve and address present socio-ecological challenges. Yet the idea that technologies could bring about perfectly circular resource cycles is simply biophysically impossible. Indeed, materials inevitably degrade and dissipate each time they are cycled (Korhonen et al., 2018a; Zink and Geyer, 2017). Moreover, in a growing economy, recovered materials can only provide a fraction of our resource needs. More natural resource extraction and environmental degradation will thus remain necessary as long as economic growth continues, so the TCE and RCS visions of a perfect regenerative economy are impossible in the present growth-dependent capitalist system (Genovese and Pansera, 2021; Giampietro and Funtowicz, 2020).

On the other hand, TCS discourses can be criticised for lacking an explanation of how all the actions to increase socio-ecological justice could together reduce humanity’s overshoot of planetary boundaries. By providing the basic needs for the least well-off people on Earth, one could indeed expect a general increase in global resource consumption and extraction. Recent research has pointed out that humanity could, in fact, secure decent living standards for 8,5 billion people with just 30% of current global resource and energy use (Hickel and Sullivan, 2024). This will require a complex mix of top-down and bottom-up provisioning strategies, as well as global solidarity, in line with the TCS scenario we describe above. Yet our scenario is just a thought experiment, and much further research is needed to better define, model and explore what a post-capitalist world could look like and how it can be implemented.

In addition to this, TCS discourses could be criticised for being too optimistic about the possibility of transforming current capitalist social structures and power relations. Envisioning a post-growth society, and thus, a post-capitalist future, does seem like a far shot, especially in a discursive landscape that makes many people believe that “there is no alternative” and think that “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism” (Fisher, 2009). Yet, as Christian Felber puts it, “there are plenty of alternatives” (Felber, 2015) thanks to a rich history of social movements and ideas from the Global North and South alike that have proposed and enacted radically different ways of living and flourishing (like degrowth, buen vivir, ecological swaraj, steady-state economics, economy for the common good, the Zapatistas in Mexico etc.). Moreover, as Deutz rightly points out, “social and environmental crises are symptoms of capitalism and need to be acknowledged as such” (Deutz, 2023); we thus desperately need more research on CE visions and imaginaries that go beyond capitalism. A major question remains: how can these visions be brought to life in a world marked by the rise of far-right populism and regressive movements? Further research on strategies for transformation at local and global scales is thus needed to address this.

One final criticism that can be made regarding the TCS scenario is the concern that decreasing GDP in the Global North would be at odds with the social welfare, well-being, and happiness of people in those regions. While this is a crucial concern, it is also true that continued growth in the countries of the Global North is likely to remain slow or stagnant due to rising resource scarcity and continued climate breakdown (Jackson, 2021). In addition to this, it is worth mentioning that many countries, like Costa Rica, Algeria, Moldova, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam, are able to achieve high social welfare outcomes with low levels of GDP per capita and environmental overshoot (Fanning et al., 2021; Hickel, 2019). Similarly, research in Japan has found that despite seeing decreasing incomes and GDP since 1995, Japanese people have reported increased levels of happiness and life satisfaction as well as a move away from individualistic and consumeristic aspirations and towards collective and non-materialist aspirations, especially among younger people (Komatsu et al., 2022). It is clear that Japan and the other abovementioned countries are not examples of post-growth societies as their economic conditions are not due to democratically decided societal choices. However, the above research demonstrate that carefully planned and democratic transitions to post-capitalist degrowth societies could be carried out without jeopardising social welfare, well-being, and happiness.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, FCE discourses place no hope neither on technological innovations nor on fair societal transformations. Instead, they rationally, and perhaps cynically, describe the future of humankind and planet Earth if nothing is done to reverse current unsustainable trends. Yet, it is also clear that this is not a world where anyone would like to live, except perhaps a few wealthy people who own crucial technologies and industries and could thus maintain and grow their positions of power.

One thing is certain, humanity lives on a finite and fragile planet with key boundaries and limits, and if we it keeps overshooting them, the Earth’s climate and ecosystems will inevitably break down and collapse, and critical resources will be exhausted. If serious transformations are not undertaken to reverse this trend, then we are likely to see crucial planetary functions fail before our eyes. Choosing circular futures focused on technological innovations and eco-economic decoupling alone will not suffice. However, if we foster more holistic and diverse post-capitalist futures that can operate beyond economic growth, humanity has a much better chance of overcoming the present crisis. The real choice might thus not be between a TCE, RCS, TCS and FCE society but actually between a TCS and FCE society because those are the only discourses that take the very real material limits of our planet into account. To paraphrase Rosa Luxemburg, we are faced with a choice not just between “socialism or barbarism” but between “degrowth or barbarism”.

By “barbarism,” here, we mean the exacerbation of present inequalities and the creation of a world of haves and have-nots where only a few people are able to live a materially comfortable life while the rest of humanity is faced with climate catastrophes, sea level rise, displacement, war and widespread resource shortages. In contrast to this “barbarism,” it is worth remembering that there are a plurality of circular visions and ideas from the Global North and South that have developed and implemented a wide range of post-capitalist and post-growth societal visions (and TCS discourses described above are just the tip of the iceberg). They can help humanity build innovative and democratic strategies to overcome the socio-ecological challenges of the 21st century (for an account of the diversity of alternatives see: D’Alisa et al., 2014; Kothari et al., 2019).

Unfortunately, these alternatives are currently not being fully explored as research on CE has found that TCE is currently, by far, the most dominant discourse in public and private institutions (Arai et al., 2023; Berry et al., 2021; Calisto Friant et al., 2021, 2022a, 2023; Campbell-Johnston et al., 2020; Melles, 2021; Ortega Alvarado et al., 2021; Palm et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2022). CE debates and implementation to date have thus not sufficiently addressed the socio-political implications of a circularity transition and the biophysical limits to economic growth. But what would most people prefer when envisioning a circular future?

There is little research on CE perceptions; two studies of civil society and citizen perceptions of CE in the EU show that a more holistic and socially inclusive approach to CE is preferred (Lazarevic and Valve, 2017; Repo et al., 2018). Three recent surveys also suggest that citizens would prefer TCS discourses. The first survey found that 54.6% of French people prefer a socially inclusive degrowth-oriented ecological transition compared to a growth and technology-oriented neoliberal utopia (15.9%) or a conservative traditionalist utopia (29.5%) (Observatory of Utopic Perspectives, 2019). The second survey found that 74% of people in G20 countries believed that governments should move beyond focusing on economic growth and profits and instead focus more on human well-being and ecological protection (Gaffney et al., 2021). The third survey found that 60.5% of people in 34 European countries favour post-growth values such as environmentalism, collectivism and altruism as opposed to neoliberal capitalist values like hierarchy, individualism, and materialism (Paulson and Büchs, 2022).

Moreover, a recent survey on CE perceptions around the world by Utrecht University and Revolve Circular found that holistic circular society discourses (TCS and RCS) were preferred compared to segmented discourses (FCE and TCE) (51.6% vs. 48.4%) and that respondents placed a high degree of importance to social justice concerns and consumption/production reduction imperatives (Calisto Friant et al., 2022b).

The abovementioned research suggests that the TCE discourse, which dominates the current debate on circularity, does not align with what citizens would prefer when asked to imagine a circular future. Survey responses and citizen preferences do not tell us the whole picture and their results are often a far shot away from political choices and government decisions on sustainability (Duvic-Paoli, 2022; Repo et al., 2018). On the other hand, many other studies find that when citizens openly and freely deliberate in a well-informed, inclusive, and democratic environment, they tend to make significantly more sustainable decisions than politicians (e.g., Cabannes, 2018; Calisto Friant, 2019; Dryzek et al., 2019). For instance, the policies proposed by the randomly selected climate citizens’ assemblies in France and the UK were far ahead in social and ecological aspects compared to what politicians advocated (Duvic-Paoli, 2022; Galván Labrador and Zografos, 2024). Research even finds that, in a democratic context, citizens choose to forgo personal gains for the benefit of future generations (Hauser et al., 2014).

A deliberative governance process that hands decision-making power to citizens could help co-design and implement fair and sustainable circularity policies that subordinate economic growth to planetary boundaries and social justice imperatives (Calisto Friant et al., 2024). This democracy is also needed in the workplace by fostering non-profit cooperatives owned and managed democratically by workers for the benefit of their socio-ecological communities (Pansera et al., 2024; Villalba-Eguiluz et al., 2023). Indeed, shareholder capitalist corporate structures, whereby business decisions are taken in a top-down manner, are often at odds with key social needs and environmental imperatives as corporations must focus on maximising profit growth for their stock-owners rather than socio-ecological benefits (Hankammer et al., 2021; Hinton, 2021).

All in all, a more diverse, democratic, and inclusive construction of a circular future in both the political and economic spheres is needed to better include the plurality of citizens’ discourses and perspectives on circularity.

This research also has limitations. Our description of 4 circular futures is an inevitable subjective simplification of complex visions. While the authors and the peer review process helped refine the quality of the results and limit excesive bias, these visions are ultimately the result of a subjective though experiment that inevitably simplifies complex systemic transformations. The main objective and value of this paper is thus to help understand the core differences between circularity discourses and help foresee possible future transformations so we may better prepare and plan for them. Nonetheless, the actual future of our planet is complex and unpredictable and will depend on how we address present challenges today.

5 Conclusion

This paper explored 4 CE futures and their key sustainability implications. Our insights suggest that the hegemonic and growth-focused TCE discourse is more a “fairy tale” of technological innovation and competitiveness than a feasible circular transition for all humanity. This TCE future will likely provide many benefits for a few leading businesses, industries, countries, and economic actors but will also most certainly be unable to ensure the provision of basic needs for everyone while reversing the overshoot of planetary boundaries. In fact, such a future might worsen the unsustainable extraction of natural resources from the Global South and could end up exacerbating current patterns of neo-colonial discrimination and exploitation along gender, race, class, and ethnic lines. The TCE vision may have become the hegemonic CE discourse precisely because it ignores these social and political implications. It is, hence, a depoliticised discourse that seeks to create a CE transition that does not challenge the current growth-dependent capitalist system of endless expansion and commodification of Life. In this vision, transition “from linear to circular” means better resource efficiency and recovery technologies rather than addressing the systemic causes of our current socio-ecological crisis. It is thus unsurprising that such a discourse gained so much traction in the policy and business arena, as it promises that a circular flow of materials could allow capitalist economies and businesses to continue growing.

Yet, this TCE discourse is in no way the only vision of a circular future. There are many different circular visions that subordinate economic growth and profits to social and ecological imperatives. We explored these in the TCS future, and as mentioned above, various surveys suggest that citizens actually prefer a more transformative and socially inclusive circularity transition. More inclusive and participatory development of circularity policies, where citizens can openly deliberate and decide on the course of the circularity transition in an informed and democratic manner, could thus help overcome current lock-ins and path dependencies. Hence, we, first and foremost, call for democratic practices that empower people through randomly selected citizen councils, non-profit cooperatives, and other institutions that can break powerful interests and lead the way to a socially legitimate and ecologically feasible circularity transition.

Beyond its findings and proposals, our paper has its limitations. The qualitative and descriptive nature of each scenario is inevitably subjective as it relies on the imagination and reflections of the authors. To address these limitations, future studies can use transdisciplinary workshops, surveys, and other participatory methods to develop future CE transition scenarios. Moreover, quantitative modelling could be used to quantify key social, ecological and economic variables for each scenario. In addition to this, this paper has not looked at how a desirable circularity transition may be achieved by 2050. Further research could thus explore the potential pathways to realising desirable CE futures.

More research is also needed to gain a better picture of what circularity discourses people find most appealing and what circular economy and society policies they would choose in a democratic context. Further research on circular futures and citizen perspectives and preferences on circularity could help plan and envision a desirable circular transition that actually brings about improvements in human and planetary well-being. In doing so, our paper and our illustrations of the four different futures can help visualise the diversity of existing circularity visions, with their key differences and commonalities. It can also help imagine a plurality of solutions, practices, and policies that can be developed using different circularity approaches. Finally, it can help in transdisciplinary research activities and participatory workshops to define democratic agreements and common visions regarding the shape and type of circularity transition that people can aspire to co-design and co-create.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WV: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RS: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme grant agreements nos. 765198 and 101003491. Previous versions of this paper were published as a blog post on CircularConversations.com and as a chapter in Deliverable 1.1 of the Just2CE project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arai, R., Calisto Friant, M., and Vermeulen, W. J. V. (2023). The Japanese circular economy and sound material-cycle society policies: discourse and policy analysis. Circ. Econ. Sust. 4, 619–650. doi: 10.1007/s43615-023-00298-7

Bauwens, T., Hekkert, M., and Kirchherr, J. (2020). Circular futures: what will they look like? Ecol. Econ. 175:106703. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106703

Bengston, D. N. (2019). Futures research methods and applications in natural resources. Soc. Nat. Resour. 32, 1099–1113. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2018.1547852

Berry, B., Farber, B., Rios, F. C., Haedicke, M. A., Chakraborty, S., Lowden, S. S., et al. (2021). Just by design: exploring justice as a multidimensional concept in US circular economy discourse. Local Environ. 27, 1225–1241. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2021.1994535

Börjeson, L., Höjer, M., Dreborg, K.-H., Ekvall, T., and Finnveden, G. (2006). Scenario types and techniques: towards a user’s guide. Futures 38, 723–739. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2005.12.002

Cabannes, Y. (2018). The contribution of participatory budgeting to the achievement of the sustainable development goals: lessons for policy in commonwealth countries. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 21. doi: 10.5130/cjlg.v0i21.6707

Calisto Friant, M. (2019). Deliberating for sustainability: lessons from the Porto Alegre experiment with participatory budgeting. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 11, 81–99. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2019.1570219

Calisto Friant, M. (2022). From circular economy to circular society: analysing circularity discourses and policies and their sustainability implications. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Utrecht University.

Calisto Friant, M., Lakerveld, D., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Salomone, R. (2022a). Transition to a sustainable circular plastics economy in the Netherlands: discourse and policy analysis. Sustain. For. 14. doi: 10.3390/su14010190

Calisto Friant, M., Reid, K., Boesler, P., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Salomone, R. (2023). Sustainable circular cities? Analysing urban circular economy policies in Amsterdam, Glasgow, and Copenhagen. Local Environ. 28, 1331–1369. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2023.2206643

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W., Bernal, L., and Bauer, S. (2022b). How do you imagine a circular economy? Survey report. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Utrecht University & Revolve Circular.

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Salomone, R. (2020). A typology of circular economy discourses: navigating the diverse visions of a contested paradigm. Resour. Conserv. Recycling 161:104917. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104917

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Salomone, R. (2021). Analysing European Union circular economy policies: words versus actions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 27, 337–353. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2020.11.001

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Salomone, R. (2024). Transition to a sustainable circular society: more than just resource efficiency. Circ. Econ. Sust. 4, 23–42. doi: 10.1007/s43615-023-00272-3

Campbell-Johnston, K., Calisto Friant, M., Thapa, K., Lakerveld, D., and Vermeulen, W. J. V. (2020). How circular is your Tyre: experiences with extended producer responsibility from a circular economy perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 270:122042. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122042

D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., and Kallis, G. (2014). Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era. London: Routledge.

Deutz, P. (2023). Exploring the limitations of a circular economy under capitalism and raising expectations for a sustainable future. J. Circul Econ. 1. doi: 10.55845/HEML8087

Deutz, P., Vermeulen, W. J. V., Baumgartner, R. J., Ramos, T. B., and Raggi, A. (Eds.) (2024). Circular economy realities: Critical perspectives on sustainability. London: Routledge.

Dryzek, J. S., Bächtiger, A., Chambers, S., Cohen, J., Druckman, J. N., Felicetti, A., et al. (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science 363, 1144–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2694

Duvic-Paoli, L.-A. (2022). Re-imagining the making of climate law and policy in citizens’ assemblies. Transnatl. Environ. Law 11, 235–261. doi: 10.1017/S2047102521000339

Fanning, A. L., O’Neill, D. W., Hickel, J., and Roux, N. (2021). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nature Sustainability 5, 26–36. doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00799-z

Felber, C. (2015). Change everything: Creating an economy for the common good. London, UK: ZED Books.

Gaffney, O., Jacobson, L., Boehm, S., Barthel, S., Hahn, T., Jacobson, L., et al. (2021). Global commons survey: attitudes to planetary stewardship and transformation among G20 countries. Ny, USA: Global Commons Alliance.

Galván Labrador, A., and Zografos, C. (2024). Empowerment and disempowerment in climate assemblies: the French citizens’ convention on climate. Environ. Policy Gov. 34, 414–426. doi: 10.1002/eet.2093

Genovese, A., and Pansera, M. (2021). The circular economy at a crossroads: technocratic eco-modernism or convivial Technology for Social Revolution? Capital. Nat. Social. 32, 95–113. doi: 10.1080/10455752.2020.1763414

Giampietro, M., and Funtowicz, S. O. (2020). From elite folk science to the policy legend of the circular economy. Environ. Sci. Pol. 109, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.012

Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Brockway, P., et al. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights. Environ. Res. Lett. 15. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

Hankammer, S., Kleer, R., Mühl, L., and Euler, J. (2021). Principles for organizations striving for sustainable degrowth: framework development and application to four B corps. J. Clean. Prod. 300:126818. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126818

Hauser, O. P., Rand, D. G., Peysakhovich, A., and Nowak, M. A. (2014). Cooperating with the future. Nature 511, 220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature13530

Hermann, R. R., Pansera, M., Nogueira, L. A., and Monteiro, M. (2022). Socio-technical imaginaries of a circular economy in governmental discourse and among science, technology, and innovation actors: a Norwegian case study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 183:121903. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121903

Hickel, J. (2019). Is it possible to achieve a good life for all within planetary boundaries? Third World Q. 40, 18–35. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2018.1535895

Hickel, J., and Kallis, G. (2019). Is green growth possible? New Polit. Econ. 25, 469–486. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

Hickel, J., and Sullivan, D. (2024). How much growth is required to achieve good lives for all? Insights from needs-based analysis. World Dev. Perspect. 35:100612. doi: 10.1016/j.wdp.2024.100612

Hinton, J. (2021). Five key dimensions of post-growth business: putting the pieces together. Futures 131:102761. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2021.102761

Jackson, T. (2016). Prosperity without growth: Foundations for the economy of tomorrow. London: Routledge.

Komatsu, H., Rappleye, J., and Uchida, Y. (2022). Is happiness possible in a degrowth society? Futures 144:103056. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2022.103056

Korhonen, J., Honkasalo, A., and Seppälä, J. (2018a). Circular economy: the concept and its limitations. Ecol. Econ. 143, 37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.06.041

Korhonen, J., Nuur, C., Feldmann, A., and Birkie, S. E. (2018b). Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 544–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.111

Kothari, A., Demaria, F., and Acosta, A. (2014). Buen Vivir, degrowth and ecological Swaraj: alternatives to sustainable development and the green economy. Development 57, 362–375. doi: 10.1057/dev.2015.24

Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., and Acosta, A. (2019). Pluriverse: a post-development dictionary. Tulika Books, New Delhi, India.

Lazarevic, D., and Valve, H. (2017). Narrating expectations for the circular economy: towards a common and contested European transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 31, 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.006

Leipold, S., Petit-Boix, A., Luo, A., Helander, H., Simoens, M., Ashton, W. S., et al. (2023). Lessons, narratives, and research directions for a sustainable circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 27, 6–18. doi: 10.1111/jiec.13346

Marjamaa, M., and Mäkelä, M. (2022). Images of the future for a circular economy: the case of Finland. Futures 141:102985. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2022.102985

Melles, G. (2021). Figuring the transition from circular economy to circular society in Australia. Sustain. For. 13:10601. doi: 10.3390/su131910601

Observatory of Utopic Perspectives (2019). L’Observatoire des Perspectives Utopiques, Rapport d’analyse. Paris, France: Observatory of Utopic Perspectives.

Oomen, J., Hoffman, J., and Hajer, M. A. (2022). Techniques of futuring: on how imagined futures become socially performative. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 25, 252–270. doi: 10.1177/1368431020988826

Ortega Alvarado, I. A., Sutcliffe, T. E., Berker, T., and Pettersen, I. N. (2021). Emerging circular economies: discourse coalitions in a Norwegian case. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 26, 360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2020.10.011

Palm, E., Hasselbalch, J., Holmberg, K., and Nielsen, T. D. (2021). Narrating plastics governance: policy narratives in the European plastics strategy. Environ. Polit. 31, 365–385. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2021.1915020

Pansera, M., Barca, S., Martinez Alvarez, B., Leonardi, E., D’Alisa, G., Meira, T., et al. (2024). Toward a just circular economy: conceptualizing environmental labor and gender justice in circularity studies. Sustainability 20:2338592. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2024.2338592

Parrique, T., Barth, J., Briens, F., Kerschner, C., Kraus-Polk, A., Kuokkanen, A., et al. (2019). Decoupling debunked: evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. Brussels: European Environmental Bureau.

Paulson, L., and Büchs, M. (2022). Public acceptance of post-growth: factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 143:103020. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2022.103020

Repo, P., Anttonen, M., Mykkänen, J., and Lammi, M. (2018). Lack of congruence between European citizen perspectives and policies on circular economy. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 7, 249–264. doi: 10.14207/ejsd.2018.v7n1p249

Suárez-Eiroa, B., Fernández, E., and Méndez, G. (2021). Integration of the circular economy paradigm under the just and safe operating space narrative: twelve operational principles based on circularity, sustainability and resilience. J. Clean. Prod. 322:129071. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129071

Vermeulen, W. J. V., Calisto Friant, M., Campbell-Johnston, K., and Klein, N. (2024). Navigating diverse understandings of a circular economy, in: circular economy realities: critical perspectives on sustainability : Routledge, 45–63.

Villalba-Eguiluz, U., Sahakian, M., González-Jamett, C., and Etxezarreta, E. (2023). Social and solidarity economy insights for the circular economy: limited-profit and sufficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 418:138050. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138050

Walker, A. M., Opferkuch, K., Roos Lindgreen, E., Raggi, A., Simboli, A., Vermeulen, W. J. V., et al. (2022). What is the relation between circular economy and sustainability? Answers from frontrunner companies engaged with circular economy practices. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2, 731–758. doi: 10.1007/s43615-021-00064-7

Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Streeck, J., Pichler, M., et al. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part I: bibliometric and conceptual mapping. Environ. Res. Lett. 15. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab8429

Yalçın, N. G., Paredis, E., and Jaeger-Erben, M. (2023). Contested discourses of a circular plastics economy in Europe: prioritizing material, economy, or society? Environ. Polit. 33, 219–239. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2023.2192145

Keywords: circular economy, circular society, future studies, sustainability, degrowth, post-growth, just transition, socio-ecological transition

Citation: Calisto Friant M, Vermeulen WJV and Salomone R (2025) Degrowth or barbarism? An exploration of four circular futures for 2050. Front. Sustain. 6:1527052. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1527052

Edited by:

Frieder Rubik, Institute for Ecological Economy Research, GermanyReviewed by:

Melanie Jaeger-Erben, Chair Sociology of Technology and the Environment Brandenburg University of Technology, GermanyUlrich Petschow, Institute for Ecological Economy Research, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Calisto Friant, Vermeulen and Salomone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Calisto Friant, bS5jYWxpc3RvLmZyaWFudEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Martin Calisto Friant

Martin Calisto Friant Walter J. V. Vermeulen

Walter J. V. Vermeulen Roberta Salomone

Roberta Salomone