- School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Department of Sociology, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden

This study examines the meanings and practices of ethical consumption in Iran, enriching dominant narratives that link ethical consumption primarily to institutional frameworks or environmental discourses. It argues that ethical considerations are instead embedded in local cultural, spiritual, and social norms. The research draws on 19 in-depth qualitative interviews with urban residents in the midsized city of Urmia. A thematic analysis was employed to understand participants' practices across three stages of consumption: pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption. In the pre-consumption stage, structural constraints—such as limited access to reliable information and economic precarity—define the boundaries of ethical choices. The consumption stage is primarily influenced by sufficiency-oriented ethic through the avoidance of heyf-o-meyl (wastefulness and unnecessary consumption), reflecting values rooted in traditional and cultural teachings. In the post-consumption stage, the practice of ehsan kardan (acts of care and generosity) emerged as a key form of ethical divestment that minimizes waste and supports others in need. The study reveals that participants conceptualize ethical consumption through human-centered values—such as care, responsibility, and generosity—rather than through environmentalism or formal regulation. The results contribute to the literature on sustainable consumption by highlighting culturally embedded, locally meaningful forms of ethical engagement that constitute a moral micro-economy.

1 Introduction

Ethical consumption refers to everyday practices aimed at minimizing harm and promoting care for people, resources, society, and the environment (Yang and Cayla, 2025; Ariztia et al., 2018; Summers, 2016). It is a complex and multifaceted subject. For instance, consumption is dependent on infrastructures of provision (Shove, 2003) and is deeply embedded in social relations, norms, and institutional structures (Princen, 1999; Boström, 2023); and the “ethical” is inherently relative, taking on diverse forms across different contexts and often motivated by varying moral, cultural, political and institutional stimuli (Garlet et al., 2024; Trnka and Trundle, 2014). As societies evolve, so too do the meanings and practices associated with ethical consumption, making it increasingly challenging to determine what it means to consume ethically and how to do so in practice (Newholm et al., 2015). These challenges highlight the need to understand ethical consumption within specific contexts and to explore how it is practically interpreted and enacted in everyday life.

The phenomenon has gained significant visibility in the Global North, where both its conceptual foundations and practical expressions are deeply rooted in historical trajectories of modernity, liberal market institutions, and individualistic moral frameworks. Within these contexts, ethical consumption often intersects with other emerging forms of consumption, such as conscious consumption (Carfagna et al., 2014; Foti and Devine, 2019), sustainable consumption (Geiger et al., 2018), green consumption (Connolly and Prothero, 2008), and voluntary simplicity (Rebouças and Soares, 2021). These recently developed consumption practices are supported by a combination of civil society engagement, policy innovation, and consumer movements, all of which are grounded in values of individual autonomy and market liberalism. Consumers in these settings are regularly exposed to a wide and evolving array of information encouraging lifestyle change, typically framed in terms of market-based choices. As a result, ethical consumption is often expressed through institutionalized forms of consumer activism: buying Fairtrade or eco-labeled products, supporting ethical fashion, or participating in targeted boycotts. Across these practices, personal responsibility is emphasized as the primary mechanism for achieving social and environmental change (see Ariztia et al., 2018; Connolly and Prothero, 2008; Carfagna et al., 2014; Foti and Devine, 2019; Lekakis, 2012).1

However, framing ethical consumption primarily through market-based mechanisms risks overlooking alternative forms of ethical engagement that are embedded in social relations, communal obligations, and cultural-religious norms (Karimzadeh and Boström, 2024; Ariztia et al., 2018; Carrier and Wilk, 2012). Importantly, the notion of “the market” is not universally applicable: markets can take various forms, including globalized supply chains, informal community exchanges, barter networks, or state-regulated economies. When ethical consumption is narrowly defined through practices such as Fairtrade certification or consumer boycotts— markers rooted in Northern consumer cultures—it promotes a deficit narrative. This narrative mistakenly portrays communities outside these frameworks as disengaged from ethical concerns (Ariztia et al., 2015).

This narrative also contributes what decolonial scholars describe as epistemic privilege: the tendency to universalize Northern, white, and affluent understandings of “ethical” behavior while marginalizing or erasing alternative subjectivities and practices (see Escobar, 2018). Ethical frameworks rooted in colonial histories and liberal moral philosophies often fail to account for how people in the Global South, or in economically marginalized regions more generally, navigate ethical decisions within contexts of structural constraint and material precarity. In this sense, the concept of ethics itself is not ideologically neutral; rather, it is historically and culturally produced and often aligned with Eurocentric narratives of progress, transition and sustainability (cf. Hickel, 2020).

This calls for a rethinking of ethical consumption—one that recognizes how it is narrated and enacted differently across cultural, material, and historical contexts. It also raises several critical questions: How does ethical consumption take shape in communities with varying forms of market or civil society infrastructure? What values—spiritual, relational, or cultural—guide consumption choices in these settings? And how are ethical concerns articulated when conventional sustainability mechanisms are absent or inaccessible?

2 Context and contribution

Ethical consumption is widely recognized as a phenomenon shaped by specific cultural, institutional, and socio-economic environments (Karimzadeh and Boström, 2023; Boström et al., 2018; Shaw et al., 2016; Newholm et al., 2015). Despite this recognition, the literature has predominantly focused on Global North contexts and market-based possibilities such as Fairtrade, eco-labeling, and consumer boycotts (Connolly and Prothero, 2008; Ghali, 2021). These frameworks tend to assume the presence of liberalized market economies, strong civil society institutions, consumer sovereignty, and regulatory infrastructures—conditions that are not universally applicable. In contexts like Iran, where prolonged economic sanctions and political isolation have significantly shaped the economy, such assumptions do not hold. Limited access to certified ethical goods, coupled with constrained institutional support and consumer advocacy, poses a distinct set of challenges for practicing ethical consumption (Kahalzadeh, 2023). While some recent work has begun to address ethical consumption in non-Western and marginalized contexts (Kutaula et al., 2024; Karimzadeh and Boström, 2024; Ariztia et al., 2018), much remains unexplored. This study contributes to this growing body of literature by examining ethical consumption in Urmia, a mid-sized city in northwestern Iran, where individuals negotiate ethical concerns in ways that reflect local constraints, cultural norms, and everyday lived realities.

Urmia, a city marked by ethnic and linguistic diversity, accommodating a variety of cultural traditions and social networks that shape everyday life, including consumption. Despite its growing urbanization, it retains many features of a tightly knit community where family and friendship networks, cultural customs, and informal exchange relationships play a strong role in daily life. Such social ties often influence where people shop, who they trust, and how they interpret responsibility and care in everyday consumption. However, these local dynamics must be situated within the broader national context. Its production system operates within a complex framework shaped by prolonged economic sanctions and political isolation, leading to partial integration with global supply chains. While Iran maintains trade relations with selected countries, particularly within Asia and the Global South, it remains largely excluded from global ethical production circuits commonly associated with certifications like Fairtrade, organic labeling, or international labor standards. As a result, Iranian consumers have limited access to globally recognized ethically certified goods. The country lacks strong consumer advocacy groups, independent labor unions, and functioning civil society organizations that might otherwise support ethical or sustainable consumption. Civil society actors operate under tight regulatory oversight (Bayat, 2013), and there are no nationally recognized ethical labeling schemes or certification mechanisms like Fairtrade.

Consumer agency in markets depends on the availability of [ethical] alternatives (Casais and Faria, 2022)—yet in Iran, such options are often absent, particularly for products like organic foods or ethically sourced textiles. Consequently, even consumers with strong ethical intentions may find it difficult to act on their values, leading to a cycle of frustration and disengagement. Nevertheless, informal economies including street vendors, small-scale traders, and traditional bazaars (Pourjafar et al., 2014; Moosavi, 2005) continue to play a vital role in integrating different forms of ethical values in everyday practices. Recent research highlights diverse and often contradictory consumption patterns emerging in Iran, reflecting the country's complex socio-political context. For example, Rahmanian (2023) examines how consumers resist the authoritarian regime through deliberate consumption choices, while Karimzadeh (2022) explores unsustainable consumption practices driven by widespread social discontent. On the other hand, Iran and Müller (2020) emphasize the potential of grassroots initiatives in Tehran to foster sustainable consumption, though they note the critical need for institutional support to amplify their impact. Karimzadeh and Boström (2024) discuss that in the absence of institutional support and despite economic hardship, tradition and cultural values continue to motivate ethical consumption among Iranians. Accordingly, ethical consumption in Iran is most likely shaped by cultural norms, religious duty, and personal interpretations of care, philanthropy, and sufficiency, rather than by formal certifications or structured consumer movements.

This study contributes to redefining ethical consumption as a pluralistic concept, advocating for more inclusive understandings of consumption beyond Global North contexts. Focusing on the city of Urmia, it offers nuanced insights into how ethical consumption is understood, negotiated, and practiced within a landscape shaped by material constraints, moral frameworks, and cultural traditions. By centering local voices and everyday practices the research challenges universalizing accounts of ethical consumption. Drawing on empirical data, the study shows that ethical action in this context is rarely institutionalized or driven solely by individual choice; rather, it is frequently improvised, relational, and collective. These situated practices reveal ethical consumption as a lived, contextually embedded phenomenon shaped by structural limitations and cultural specificities.

3 Integerating ethics in consumption

Consumption cultures and social contexts have long influenced one another, shaping practices and norms over time. Ethical considerations in consumption, although prominently discussed from the latter half of the twentieth century onwards, have deeper historical roots illustrating the intrinsic relationship between societal upheavals and changes in consumption practices (Smith and Johns, 2020). Events such as the Richmond Bread Riots in 1863, the British boycott of slave-produced sugar in the late 18th century, boycotts against South African products during the apartheid era, and the 1890 Tobacco Protest in Qajar-era Iran, illustrate how social movements have significantly impacted consumption practices locally and internationally (Carrier, 2012; Newholm et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2016; Boström et al., 2018). Historically, working-class participation was central to these movements, driven by varied motivations, including both ethical concerns and self-interest (Newholm et al., 2015; Stolle and Micheletti, 2005).

According to the literature, ethical consumption encompasses three dimensions: political, social, and environmental which manifest either through consumption refinement (e.g., buying ethically certified products) or consumption reduction (e.g., minimalism, voluntary simplicity) or a combination of both (Isenhour, 2012). Consumption refinement involves deliberate choices to avoid products deemed unethical due to their social or environmental impact, while consumption reduction implies decreasing overall consumption motivated by ethical, social, or ecological concerns (Li et al., 2020). However, the effective realization of these ethical dimensions depends on diverse factors such as supportive policies, infrastructural availability, and cultural and social contexts. Consequently, ethical consumption is inherently multidimensional and context-dependent, making clear distinctions challenging yet necessary for understanding varied societal contexts (Newholm and Shaw, 2007; Orlando, 2012; Summers, 2016).

Despite its perceived promise, its actual impact on environmental and social protection often remains limited or unfulfilled. For example, research indicates materialistically oriented consumers frequently purchase ethical products for self-benefit rather than altruistic motivations (Ryoo et al., 2020). Additionally, ethical consumption is often accessible predominantly to economically privileged individuals (Carrington and Chatzidakis, 2018; Chatzidakis et al., 2016). Also, it is frequently framed in political and market-driven terms, emphasizing consumer choices as a mechanism for expressing political agency through actions such as boycotting and buycotting (Beck and Ladwig, 2021; Davies et al., 2012; Hassan et al., 2023; Jung et al., 2016; O'Connor et al., 2017). Such framings carry three limitations: they confine ethical consumption studies to predetermined manifestations (e.g., boycotts, Fairtrade); geographically limit them to contexts with liberal market infrastructures; and imply that ethical consumption is exclusively a modern phenomenon, overlooking historical evidence of pre-modern ethical consumption practices (Berlan, 2012; Carrier, 2012) as well as its different manifestations. Accordingly, the market-mediated understanding of ethical consumption has faced significant criticism (Ariztia et al., 2018; Pellandini-Simányi, 2014), prompting a broader conceptualization that integrates notions of care and sufficiency (Godin et al., 2025; Callmer and Boström, 2024; Karimzadeh and Boström, 2023; Godin and Langlois, 2021).

Another critical challenge in integrating ethical consumption to everyday life is determining what constitutes a genuinely “ethical” practice, as seemingly ethical actions often entail unintended unethical consequences. For instance, purchasing products labeled Fairtrade is frequently identified as ethical consumption due to its emphasis on improving conditions for producers in developing countries. Yet, the same action can inadvertently create negative impacts, such as the environmental harm caused by long-distance transportation and packaging, or economic disadvantages for local producers unable to compete with imported Fairtrade goods (Berlan, 2012; Lyon, 2006). Moreover, practices labeled as ethical consumption, embedded within existing market logics, often serve dual purposes of promoting social responsibility and securing market profitability (Goodman, 2010; Fridell, 2007). Ethical labeling and certification schemes may reinforce consumerism rather than challenging the systemic issues that underpin inequality and environmental degradation (Barnett et al., 2011). These contradictions prompt consideration of alternative frameworks that might be more comprehensively understood through the lens of localized, seasonal, and informal market practices, where relationships between consumers and producers are direct and community oriented.

4 Method and materials

To explore the meanings and practices of ethical consumption, I adopted an exploratory qualitative design and conducted nineteen semi-structured, audio-recorded interviews with economically independent adults (aged 18 and over) residing in Urmia, Iran, between May and September 2022. Interviews lasted 17–75 min, were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and data collection ceased once thematic saturation was evident in the nineteenth transcript. Participants were recruited initially through purposive outreach to my community network, a strategy intended to build rapport and create a secure environment for open dialogue on topics (ethical consumption in this case) that may include sensitive issues (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2015; Atkinson and Flint, 2001). It was combined by snowball sampling to access participants beyond my immediate circles. Both sampling strategies carry inherent risks; recruiting from known networks, while facilitating trust and richer disclosures, may limit the diversity of perspectives captured. Similarly, snowball sampling can reinforce existing social similarities, potentially constraining the range of experiences discussed. Nevertheless, these recruitment strategies were supplemented by deliberate efforts to ensure demographic heterogeneity: the final sample included ten women and nine men, aged between 22 and 62 years, with education levels ranging from secondary school (n = 1) and diploma (n = 3) to associate degree (n = 1), bachelor's degree (n = 6), master's degree (n = 5), and doctoral degree (n = 3). While the study does not claim statistical generalizability, the purposive pursuit of information-rich cases, the attainment of thematic saturation, and the provision of thick descriptive data support the study's credibility and facilitate analytic transferability to other underexplored settings in the ethical consumption literature.

Participants were asked questions structured around three stages of consumption: pre-consumption (decision-making and selection of goods), consumption (purchasing and actual usage), and post-consumption (disposal, reuse, or reflection). At each stage, follow-up probes explored ethical considerations indirectly to avoid bias; the explicit term ethical consumption was not mentioned. Instead, ethical dimensions were elicited by prompting participants to reflect on how “other-oriented” factors—such as concern for family, community, future generations, or environmental impacts—shaped their everyday consumption practices. In the pre-consumption stage, participants discussed conditions and considerations influencing their routine decisions, such as purchasing food, clothing, and other consumer goods. Specific probes included their thoughts on the production processes behind products they regularly consume, the potential impacts of their shopping decisions on broader society, and whether concerns about product origin, materials, or the quantity purchased influenced their choices. They were further asked how contextual factors (such as cultural norms, regulatory frameworks, available infrastructure, technological opportunities, and social expectations) enable or constrain their integration of ethical considerations. At the consumption stage, questions explored participants' opinions on the volume consumed, especially within private or social contexts (e.g., family gatherings), and whether they actively tried to reduce their consumption, including reasons and strategies for doing so. Finally, during the post-consumption stage, participants described their practices related to disposal, recycling, reuse, and redistribution (e.g., via second-hand stores, sharing, or gifting), explaining the motivations and processes underlying these practices.

The data analysis followed a two-stage thematic process. It began with initial (open) coding, in which broad patterns and categories were identified, followed by focused coding to refine these into more specific subthemes (Mason, 2017; Braun and Clarke, 2006). The analysis adopted a combined deductive and inductive reasoning which allowed for a dynamic interplay between theory and empirical observation (Timmermans and Tavory, 2012). The deductive phase involved examining pre-existing conceptual categories commonly associated with ethical consumption such as boycotting and fair trade, though with sensitivity toward their varied interpretations and manifestations within the studied context. Simultaneously, the inductive dimension facilitated the identification of emergent themes, particularly those capturing how ethical consumption is shaped by local, cultural, and social factors. The iterative movement between theory and data allowed for both the recognition of globally circulated categories and the discovery of locally meaningful expressions of care, restraint, and responsibility in everyday consumption.

5 Results

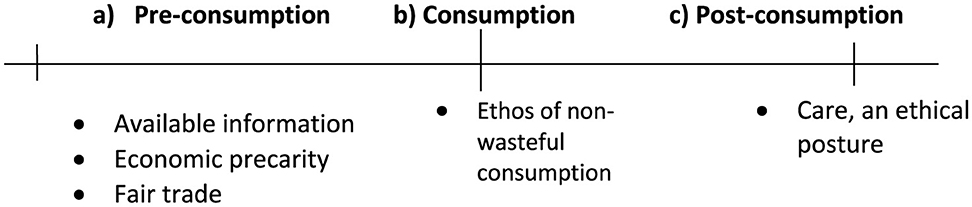

The findings are structured across a three-phase consumption spectrum: pre-consumption, consumption, and post-consumption (Figure 1). Each phase highlights distinct dynamics, challenges, and practices related to ethical consumption, reflecting individuals' subjective understandings of ethics, their practical enactments, and the barriers or opportunities they encounter given the available resources.

In the pre-consumption stage, three critical factors influencing ethical purchasing decisions are identified: difficulty accessing reliable information, economic adversity, and considerations of fair trade. In the consumption stage, I analyze a culturally embedded belief and enact: the notion that caring for one's belongings is a personal and moral responsibility. This cultural logic reframes ethical consumption as the act of maintaining and preserving possessions rather than prioritizing the ethical sourcing of goods. Finally, the post-consumption stage explores an Iranian tradition that, while not originally motivated by environmental concerns, inadvertently promotes sustainable practices such as sharing and donating.

By interpreting ethical consumption through the lens of local culture and tradition, this analysis shows how context-specific norms can support broader environmental objectives and extend the scope of sustainable practices accordingly. Together, these stages reveal a multifaceted portrait of ethical consumption, where cultural values, individual agency, and structural constraints intersect—sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in tension.

5.1 Pre-consumption stage

5.1.1 Difficulty accessing reliable information

A lack of credible and clear information is one of the most consistent barriers to ethical consumption (Casais and Faria, 2022; Ghali, 2021; Wiederhold and Martinez, 2018). The missing data span the entire value chain—from the origin of raw materials to wages, working hours and workplace safety—leaving consumers unable to judge whether a product accords with their values. According to Osburg et al. (2017), information must be credible (they trust the source), meaningful (it relates directly to their concerns) and easy to understand if it is to trigger ethical purchasing. This study shows that all three criteria are largely unmet in the studied context. Participants specifically mentioned difficulties reaching trustworthy information on working conditions, wages or the origin of raw materials. As Mahi (47, female) put it:

“I personally know many workers who are working in horrible situations. Can you study them?... there is no organized information about it.”

Several interviewees doubted the truthfulness of official statements. Behnam (42, male) explained:

“We don't have time to hunt for evidence, and I don't trust formal reports. Factories here pay minimum wages, use short contracts and keep everything hidden. I only see the final product, never the process.”

A Retailer raised similar doubts:

“Responsible consumer is linked to a responsible producer. You cannot be a responsible consumer unless the producer is also responsible. Environmental issues or labour conditions are not at all a concern for producers.” (Emad, 62, male)

Despite a widespread belief among participants that many goods are produced under unfair conditions, no one mentioned ceasing to buy specific products on this basis.

“I don't remember I have done something like boycotting. The market is the same everywhere. There is no alternative. I recently bought a car which I know damages the environment, has low quality but I still buy it. There is no other choice for us or if there is they are very expensive.” (Ali, 29, male)

From his point of view, those living in such a situation feel confined by external forces that significantly limit their freedom of choice and impose unwanted circumstances upon them. He ended his response by saying that “… we can't do what we want to do”. Instead of boycotting a particular product they are favoring local and seasonal farm markets. Given the context, these settings are perceived as more transparent, closer to the consumer, and more trustworthy. While occasional objectionable actions may surface among individual consumers (Rahmanian, 2023), these behaviors are typically transient and fail to yield the desired impact as they are provisional. However, this mirrors evidence that, when formal certification is weak, consumers fall back on relational cues to infer ethical production (Johnstone and Tan, 2015).

Interestingly, a clear divergence emerged when participants discussed services such as insurance companies compared to physical goods like food or clothing. In contrast to product purchases, respondents were far more willing to boycott service providers.

“…I look for fair services… for example, I boycotted some insurance companies because of the damage that they cause to the environment. When I was in their offices, I learned they use a lot of paper for their paperwork, I saw it… and it really bothers me.” (Mehrdad, 31, male)

This discrepancy reflects key differences between services and material goods. Services are delivered in real time and often involve face-to-face interaction. This proximity gives consumers more direct exposure to the provider's behavior and values, making ethical judgments more immediate and tangible. As Princen (1997, 1999) argues, modern consumption is often shaped by processes of distancing—where the social and environmental consequences of consumption are physically and psychologically removed from the consumer—and shading, in which ethically relevant information is obscured or selectively presented. These mechanisms tend to reduce the visibility of harm or exploitation, particularly in globalized supply chains. Service transactions in this case minimize both distancing and shading. Because interactions occur in person, consumers observe and assess the provider's actions directly, without relying on third-party narratives or certifications. As a result, ethical decisions are more often grounded in immediate experiences. In such cases, the primary factor influencing whether individuals choose to boycott or disengage from a service provider is how that provider treats its customers. When companies are also perceived to be affiliated with the state—a common suspicion in Iran—these individual refusals can escalate into collective acts of consumer resistance (Rahmanian, 2023).

In the context studied, boycotting is not a widely accepted or practiced mode of (material) market communication. This aligns with Katz's (1996) assertion that when outcomes are uncertain or unlikely, people often find it more acceptable to endure the consequences of inaction than to risk the potential fallout of taking ineffective action. In contrast, taking an ethical stand—such as boycotting products—entails financial, emotional, and social costs that many participants are unwilling or unable to bear without a clear sense of impact. This rationalization reflects cognitive strategies identified in the literature on consumer ethics. Concepts such as “willful ignorance” (Ehrich and Irwin, 2005) and “intentional ignorance” (Mackendrick and Stevens, 2016) describe situations in which individuals deliberately avoid seeking additional information about the ethical implications of their consumption choices. They do so not because they are indifferent, but because they anticipate that such knowledge would create a moral obligation to act; an obligation they feel structurally unable to meet. However, when conditions of visibility, support, and responsiveness are present, they are more likely to mobilize even if only selectively (through acts like service boycotts).

5.1.2 Dealing with economic precarity

Economic precarity is a significant barrier to ethical consumption, and it consistently appears in literature as a determinant of limited or compromised consumer agency (Huddart Kennedy et al., 2019; Isenhour, 2010; Orlando, 2012). In contexts of economic instability, individuals often prioritize survival over values-based purchasing, not because they are indifferent to ethical concerns, but because the costs—both material and symbolic—are too high to bear. This tension emerged clearly in the data. Participants frequently described how high inflation, insecure employment, and limited purchasing power forced them to deviate from their ideals.

“The main concern is how to make money. Your job might completely damage the environment, but what you think about is how to feed your family. Our priority is surviving.” (Arman, 29, male)

This remark illustrates how survival needs displace environmental and ethical considerations. For many, the ethics of consumption are not dismissed outright, they are simply subordinated to more immediate and pressing concerns. Dana (40, male), a factory worker, echoed this sentiment:

“I am a worker. Everything that I buy, I think about workers' conditions. But there is something here. I am still struggling to meet my basic needs, then I cannot do anything. I cannot even express it [my environmental concerns] to my wife or my kids. It looks very nonsense to them.” (Dana, 40, male)

In such contexts, ethical consumption is perceived as a form of privilege, a luxury afforded only to those with a buffer from economic hardship. Many participants described boycotts and ethical purchasing not as irrelevant, but as actions that require a threshold of material security. This finding supports results in other global studies (Shaw et al., 2005), particularly where ethical acts are tied to more expensive alternatives or information-intensive decision-making. Amin (35, male) commented on this disparity:

“… these ideas work better in EU countries and so on which have access to brands and then they have more options.” (Amin, 35, male)

This notion of “having options” was central. Without affordable and accessible alternatives, making ethical choices becomes not only difficult but emotionally burdensome. Ethical ideals may even provoke guilt or frustration in those who cannot act on them:

“… People shouldn't be blamed for their wrong behaviour if they aren't given better options. When they are soaked with many other problems in their daily life, taking care of the environment goes to the end of their [to-do] list. They are not the right people to think about the future generation. Don't forget social dissatisfaction on top of it as well. I am sure it is not just about Iranian citizens. If Russia keeps continuing this war and people in Europe lack gas, what do they do? If you stuck in a war situation, which one do you prefer? To stay in the cold or to cut the trees to keep your room warm… we struggle to keep ourselves alive, their [people in welfare societies] stomach is full, and their money is in their pockets… Of course, we all are responsible for the future, but we should be able to live first.” (Arman, 29, male)

This framing moves beyond simple economic logic to a more existential rationale: when basic needs are unmet, ethical consumption becomes morally deferred rather than rejected. Ethical behavior, in this view, requires structural support: access to options, consumer protection, economic stability, and trust in institutions. This dynamic reflects ethical elasticity, a strategy that individuals adjust their ethical behaviors in relation to perceived necessity and available resources (Barnett et al., 2011). Under conditions of hardship, the ethical horizon narrows, and long-term concerns (e.g., environmental protection, intergenerational justice) are displaced by short-term needs. In such cases, ethical action is not absent, but reframed around immediate responsibility—for family, survival, and daily functionality. Maintaining existing consumption patterns, especially when they are more financially viable and socially normalized, offers a form of psychological comfort and economic pragmatism. Participants in this study frequently expressed this dual consciousness: as citizens, they are deeply worried about environmental degradation and social injustice; as consumers, they feel largely powerless to respond through the collective choices. Therefore, ethical inaction in this context might be interpreted not as complacency, but as a form of constrained agency. People are not ignoring the problem; they are navigating it with limited tool and limited hope that their individual choices can contribute to small-scale changes.

5.1.3 Fair trade in Iran

Fair trade—whether defined as a formal certification system (Fairtrade) or as a broader commitment to socially just and equitable trading practices—has long been viewed as a cornerstone of ethical consumption (Carrier, 2012; Brinkmann and Peattie, 2008). Varul (2009) argues that the realization of global Fairtrade schemes depends on three preconditions: a functioning global market, a consumer culture based on individual choice, and a moral ideology that fosters recognition of distant others (p. 184). Yet, these assumptions do not easily map onto every context.

Findings from this study suggest that localized forms of fair trade exist in Iran, shaped not by certification or formal systems, but by informal, value-driven economic relationships rooted in cultural and social obligations. Notably, none of the participants were familiar with the term Fairtrade as a global brand or certification. However, many are engaged in practices that align with the ethical logics of fair trade—particularly by choosing to buy from local vendors, farmers, peddlers, and independent artisans.

“… I try to find old sellers [in terms of age] and far-away shops. I know they need money, and I see it as a responsibility to support them.” (Nasim, 36, female)

“…I try to buy some time from local shops, retailers, child workers2 and so on to help them [to earn money for food].” (Nazanin, 22, female)

Buying from these sellers primarily revolves around monetary transactions between the buyer and seller, with little intention of fulfilling needs rather more benevolence. A similar content but in a different form:

“… I try to buy from local shops… especially from those who are new in the area and have younger sellers. I like to support them. I also introduce them to others and encourage other people to support them.” (62, female)

These actions reflect a relational, care-oriented approach to consumption, motivated less by material necessity than by a sense of attentiveness to others. In this context, purchasing becomes a means of expressing solidarity, addressing social inequalities, and supporting economic survival within the community. As Selma (41, female) noted:

“… think about how these big supermarkets have ruined, the local economy and individual sellers' lives. But chain markets by doing deceptive advertising trick people. It is a sort of unethical business. As much as I can, I try to buy from local retailers and independent sellers. Sometimes I don't even need what I buy, but that is the only thing they sell.” (Selma, 41, female)

The other one with some concerns about the economic growth in the country mentioned:

“Local businesses are very important to me because I think they have the main role in our economy in this situation. We don't have a growth plan like other countries. So, I value them a lot. I support them in my living neighbourhood.” (Arman, 29, male)

One particularly notable practice involves direct trade, where middlemen are bypassed, and ethical value is derived from personal connection and community benefit:

“…my mother lives in a village. She helps link farmers to city people so they can trade directly. She also helps people to exchange home furniture.” (Dana, 42, male)

This echoes what Lekakis (2012) describes as decommodification where market exchanges are reframed as social relationships rather than impersonal transactions. Similarly, Carrier (2012) emphasizes how direct trade reduces the anonymity of market objects, enhancing the ethical value of consumption by restoring a connection between buyer and producer.

Participants in this study demonstrate that socially embedded forms of trade ethics can flourish through informal, culturally resonant practices. These local strategies prioritize proximity, trust, and care, even if they sacrifice product variety or convenience. This localized ethical practice aligns with research suggesting that consumer morality is often shaped by immediate social experiences, rather than abstract global narratives (Orlando, 2012; Hassan et al., 2016). Rather than viewing fairtrade as a matter of individual choice within affluent markets, the Iranian case illustrates how people adapt moral economies to survive economic pressure while maintaining social values. Here, fair trade is not about labels but about sustaining community, and care in the face of economic adversity.

5.2 Consumption stage: ethos of non-wasteful consumption

In the consumption stage my focus is on how ethical considerations can influence consumption act in terms of form or volume. Data showcase that the participants' ethical concerns are manifested in a form of conscientious consumption drawing on an Iranian culture avoiding heyf-o-meyl (حیف و میل). Literally, heyf (حیف) means “a pity (a shame or loss)” and meyl (میل) can imply “to consume or appropriate for oneself.” In Persian usage, the compound phrase heyf-o-meyl kardan حیف و میل کردن means to squander or misappropriate something of value, whether through neglect or selfish misuse. The term carries ethical and even spiritual weight. Wasting food, money, or any blessing is seen not just as imprudent but as morally wrong—a point reinforced by religious teachings that condemn wastefulness. Thus, heyf-o-meyl signifies more than just “waste” in a technical sense; it invokes a value-laden stance that one should not carelessly and unnecessarily let useful things go to waste or misuse what one has. This concept is deeply ingrained in Iranian popular ethics and forms a key part of what is considered proper, responsible consumption in everyday life. One could say it is ingrained cultural ethic.

It is utilized in many different contexts to indicate that something which might be material such as natural resources, food, goods and commodities, or non-material such as time, feeling, emotions, youth and so on, is not being used or treated appropriately. This insight is rooted in the belief that belongings inherit value, as they encompass resources such as human ideas and labor, natural resources, and divine blessings, as well as economic investment and monetary worth. In essence, every object holds significance, hence recognizing and cherishing this value is a demonstration of being responsible and considerable human, citizen and consumer. When you are doing heyf-o-meyl, you use things carelessly and irresponsibly, you neglect proper care and squander them. The closest term in the English vocabulary might be mindful consumption however, it exclusively focuses on material aspects of consumption and therefore is not as comprehensive as the Iranian version. When participants were asked about their consumption patterns, they mainly referred to this concept: “I have learned not to heyf-o-meyl.” Arman, a 29-year-old man continued:

“…I take care of my stuff as much as possible. Materials are valuable to me… when something is not consumable anymore, I give it to people who make money from them. When you consume carefully, it is not just taking benefit from that stuff, you save your time as well because you don't spend time looking for new ones, you can put that time into other activities, and you can even make money from this saved time. Time, energy, money, and everything should be considered in the consumption process.” (Arman, 29, male).

The other participant mentioned:

“…I wear clothes as long as possible. Electronic devices as well. I don't change them just to have a new one. No!” (Behnam, 42, male)

For older participants, especially more religious ones, heyf-o-meyl is associated with a kind of “sin” and violating your responsibility in relation to “God”. They believe that everything bears the face of the creator, in their case, God, therefore, human beings should act extremely careful not to distort this face with wrong consumption forms. One can believe heyf -ing is not ethically acceptable because:

“Many people are injured in the production process. Every single grain of rice has a huge effort behind it. Have you ever seen those women who are working on rice farms? So, it brings responsibility to us. I try not to throw things away easily. I believe by making even a small [unnecessary] piece of waste we throw away the efforts that labours have put into the goods. I believe our consumption put this pressure on them.” (Mahi, 47, female)

Obviously, the concept involves various motivations related to reducing consumption volume, but it doesn't necessarily originate from modern environmental concerns aiming to minimize consumers' negative impacts on the environment and mitigate climate change. Rather, it adheres to the idea that human beings are an integral part of nature and should live in harmony with it. This way of thinking is transmitted from one generation to another through everyday life habits, norms, and informal education, and can therefore be considered as their habitus, in Bourdieusian term (Bourdieu, 1977). Inheriting the culture, an Iranian consumer may avoid waste almost automatically due to habitual values, rather than through the self-conscious reflection implied by mindfulness. Moreover, heyf-o-meyl carries a collective and spiritual connotation—it is tied to communal norms and religious teachings about not wasting divine blessings. The fundamental significance embedded in this concept revolves around its impact on minimizing consumption. Practicing restraint—not-“heyf-o-meyl-”ing—used to be considered as a positive character, and is still practiced, clearly not due to environmental concerns, but because it is a moral duty to consume responsibly, within limits that safeguard both human life and the environment as a God creature. One participant described the transition like this:

“…I have treated my kids in a way that they take good care of their stuff. I don't need to be worried about this anymore. Now they know the value of things.” (Saba, 34, female)

“… I think my parents had a big impact on the creation of my view in relation to consumption. My father used to tell us buying is very easy, but good taking care of things is important. So I have learnt it.” (Mahi, 47, female)

The sufficiency-oriented nature of this culture does not suggest that it is primarily common among low-income groups as a strategy for managing daily expenses, which Korsnes and Solbu (2024) refer to as 'sufficiency as a necessity. In the Iranian case, individuals are socialized to this practice regardless of their economic status. This culture has extended its influence into realms beyond mere individual lifestyle choices. Until recently, a well-known phrase, particularly within the clothing market, was “Beshoor-o-Bepoosh” signifying “wash and wear” [as much as you want], highlighting the durability of products that could serve you for an extended period. In this ethos, the value of long-lasting items was recognized, and consumers were incentivized to invest their money in acquiring such goods. While this motto may not hold the same prominence in today's market, its legacy persists among the majority of elderly people.

5.3 Post-consumption stage: care as an ethical posture

The post-consumption stage generally includes practices such as divestment, waste sorting, recycling, sharing, handing things over to other people, or to antique shops (second-hand shops are not common in the studied context) (Karimzadeh and Boström, 2023). Among these, the practice of sharing or shared usage (e.g., borrowing tools, appliances, or clothing) is relatively uncommon in everyday Iranian life, except in situations of necessity. For many participants, sharing recalls earlier periods of hardship—particularly the Iran–Iraq war (1980–88)—when families were compelled to share resources due to scarcity. While some older participants associate sharing with care and solidarity, others viewed it as a sign of material instability rather than ethical preference.

“… if you live a decent life, why sharing? It is okay to donate your stuff but not accept donation.” (Behnam, 42, male)

This perspective reflects a status-based discomfort with reciprocal sharing, where giving is seen as generous, but receiving is stigmatized. Sharing, in this case, does not reflect ethical mutuality, but a class-coded act tied to need.

Despite the growing global emphasis on household waste sorting out as a hallmark of sustainable post-consumption, in Iran this practice remains limited due to infrastructural and institutional shortcomings. Recent data show that over 80% of household waste is sent to landfills, with < 6% recycled and fewer than 20% of households engaged in sorting waste (Mir Mohamad Tabar et al., 2024). As a result, participants often perceived household waste segregation as ineffective from an environmental standpoint. However, rather than abandoning the practice entirely, some individuals engaged in it for alternative ethical reasons—specifically, to assist economically vulnerable individuals who collect recyclables for resale (Karimzadeh and Boström, 2024). This shift in motivation—from environmental protection to humanitarian support—reveals an important link to the broader moral economy evident in post-consumption practices in Iran. Waste sorting can become an act of compassion, performed not for planetary gain, but for the direct benefit of others. Although sorting out lacks systemic support, the ethical impulse to care for others remains a unifying thread across post-consumption behaviors, even when those actions diverge from formal sustainability frameworks.

The most prominent ethical practice in the post-consumption stage is a cultural tradition called ehsan kardan (احسان کردن), which loosely translates as “acts of generosity” or benevolent giving. Ehsan kardan involves giving goods, often clothing, food, household items, or money to those in need, not out of transactional obligation but as a caring and spiritual gesture. In many cases, the donor is motivated by both compassion and religious belief.

“…I give many of my clothes and stuff to people who need them. Years ago, I was a teacher in a school in a very deprived district. I still contact some of my former students and let them know I have packages for them.” (Shoja, 36, female)

Ehsan can also be performed on behalf of deceased loved ones. In lieu of buying flowers or holding elaborate grave ceremonies, families may donate useful items to others in memory of the deceased. This not only benefits recipients but also imbues the act with spiritual significance.

“…I used to live with my mother-in-law. After she passed away, I donated her home stuff, while I could use them myself, to many of those families who needed those things. Instead of buying flowers for her grave, which fades quickly, I give that money to help others. That feels more meaningful.” (Mahi, 47, female)

Considering these quotes, ethical consumption can be translated into an action that helps other people meet their basic needs and brings blessings to the donor and the family. In this form of consumption-related activities, the emphasis is on the positive emotions experienced by the individual engaging in such actions. Ehsan also strengthens one's symbolic capital since generosity is a virtue deeply embedded in both traditional teachings and everyday cultural norms.

6 Conclusion

The objective of this study was to understand the interplay of local and cultural factors, and ethical consumption. It draws on a small, non-representative sample encompassing Iranian consumers to offers in-depth insight into how a diverse group of urban residents in an understudied context make sense of and enact ethical consumption. Despite the structural conditions, and the challenges discussed in different stages on consumption process, ethical considerations in the studied context still play a role in fulfilling various drivers. The findings suggest that ethical consumption in this setting is shaped less by institutional structures and more by informal, traditional, and culturally embedded practices. These include values passed on sustaining communities through care (local fair trade), deeply rooted moral frameworks related to caring (ehsan kardan) and anti-wastefulness (heyf-o-meyl). Such motivations reflect ethical concerns that are integrated into daily life, even in the absence of systemic incentives or organized civil society efforts. Combination of mindful consumption, compassion, generosity, and care reflect the essence of ethical consumption among participants. On one hand, when you avoid heyf-o-meyl you manage your resources thoughtfully (avoiding excess consumption), while through ehsan kardan, you assist to those who are underconsumption to meet their needs, at least for a short period of time. Living an everyday life like this, ethical consumption flows in all pillars of life.

Indeed, one of the core global challenges today is the coexistence of overconsumption by some and underconsumption by others, which highlights enduring inequalities and ecological injustice. Being an ethical takes place by controlling overconsumption through non-wasteful and reducing underconsumption through wisely allocating available resources within the planetary boundaries and consumption corridors (Fuchs et al., 2021). While this remains a significant global ambition, the practices observed in this study, though local, informal, and often unrecognized, align in spirit with these principles. Recognizing and reinforcing these ethical traditions—through scholarship, policy, and community engagement—may offer not only a corrective to global imbalances but a culturally resonant pathway toward more just and sustainable forms of consumption.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical approval from Swedish Ethical Review Authority was obtained for the project on April 14, 2022 (Dnr 2022-01430-01). To be able to obtain our ethical approval from Swedish Ethical Review Authority, by providing the requested forms and information we committed to protecting personal information based on Swedish Ethical Review Act and Örebro University regulations. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101022789 titled “Social (im)possibilities of the formation of ethical consumption: A comparative study of Sweden and Iran.” The funder has no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all the individuals who assisted me during the interview process, with special appreciation to the participants who generously dedicated their time and shared their insights. I am also deeply grateful to Professor Magnus Boström, whose guidance throughout the broader research project of which this paper is a part has been invaluable.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used for language editing.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^To further understand to what extent the neoliberal market can provide possibilities to consume “ethically”, see “Critical Perspectives on Ethical Consumption” written by Carrington and Chatzidakis (2018).

2. ^Child labour, as referred to in this context, pertains to children engaged in street peddling.

References

Ariztia, T., Agloni, N., and Pellandini-Simányi, L. (2018). Ethical living: relinking ethics and consumption through care in Chile and Brazil. Br. J. Sociol. 69, 391–411. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12265

Ariztia, T., Kleine, D., Bartholo, R., Brightwell, G., Agloni, N., and Afonso, R. (2015). Beyond the ‘deficit discourse': mapping ethical consumption discourses in Chile and Brazil. Environ. Plann. A 48, 891–909. doi: 10.1177/0308518X16632757

Atkinson, R., and Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: snowball research strategies. Soc. Res. Update 33, 1–4.

Barnett, C., Cloke, P., Clarke, N., and Malpass, A. (2011). Globalizing Responsibility: The Political Rationalities of Ethical Consumption. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bayat, A. (2013). Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, 2nd Edn. Redwood, CA: Stanford University Press.

Beck, V., and Ladwig, B. (2021). “Ethical consumerism: veganism,” in Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, Vol. 12, Issue 1 (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.), e689. doi: 10.1002/wcc.689

Berlan, A. (2012). “Good chocolate? An examination of ethical consumption in cocoa,” in Ethical Consumption: Social Value and Economic Practice, 1st Edn. eds J. G. Carrier, and P. G. Luetchford (Berghahn Books), 43–59. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qcmfw.6 (Accessed June 17, 2023).

Boström, M. (2023). The Social Life of Unsustainable Mass Consumption. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

Boström, M., Micheletti, M., and Oosterveer, P., (eds.). (2018). “Studying political consumerism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism (Oxford University Press), 1–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190629038.013.44

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice, Vol. 16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brinkmann, J., and Peattie, K. (2008). “Consumer ethics research: reframing the debate about consumption for good,” in Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies, Vol. 13. Available online at: http://ejbo.jyu.fi/ (Accessed September 27, 2022).

Callmer, Å., and Boström, M. (2024). Caring and striving: toward a new consumer identity in the process of consumption reduction. Front. Sustain. 5:1416567. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2024.1416567

Carfagna, L. B., Dubois, E. A., Fitzmaurice, C., Ouimette, M. Y., Schor, J. B., Willis, M., et al. (2014). An emerging eco-habitus: the reconfiguration of high cultural capital practices among ethical consumers. J. Cons. Cult. 14, 158–178. doi: 10.1177/1469540514526227

Carrier, J. G. (2012). “Introduction,” in Ethical Consumption: Social Value and Economic Practice, 1st Edn, eds J. G. Carrier, and P. G. Luetchford (Berghahn Books), 1–36. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qcmfw.4 (Accessed June 17, 2023).

Carrier, J. G., and Wilk, R. (2012). “Conclusion,” in Ethical Consumption: Social Value and Economic Practice, 1st Edn, eds J. G. Carrier, and P. G. Luetchford (Berghahn Books), 217–228. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qcmfw.16 (Accessed June 17, 2023).

Carrington, M., and Chatzidakis, A. (2018). “Critical perspectives on ethical consumption,” in The Routledge Companion to Critical Marketing, eds. M. Tadajewski, M. Higgins, J. Denegri-Knott, and R. Varman (London: Routledge), 256–270. doi: 10.4324/9781315630526

Casais, B., and Faria, J. (2022). The intention-behavior gap in ethical consumption: mediators, moderators and consumer profiles based on ethical priorities. J. Macromarket. 42, 100–113. doi: 10.1177/02761467211054836

Chatzidakis, A., Carrington, M., and Shaw, D. (2016). “Conclusion,” in Ethics and Morality in Consumption, eds D. Shaw, A. Chatzidakis, and M. Carrington (New York, NY: Routledge), 281–290.

Connolly, J., and Prothero, A. (2008). Green consumption: life-politics, risk and contradictions. J. Cons. Cult. 8, 117–145. doi: 10.1177/1469540507086422

Davies, I. A., Lee, Z., and Ahonkhai, I. (2012). Do consumers care about ethical-luxury? J. Bus. Ethics 106, 37–51. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1071-y

Ehrich, K. R., and Irwin, J. R. (2005). Willful ignorance in the request for product attribute information. J. Market. Res. 42, 266–277. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.2005.42.3.266

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Foti, L., and Devine, A. (2019). High Involvement and ethical consumption: a study of the environmentally certified home purchase decision. Sustainability 11:5353. doi: 10.3390/su11195353

Fridell, G. (2007). Fair Trade Coffee: The Prospects and Pitfalls of Market-Driven Social Justice. University of Toronto Press.

Fuchs, D., Sahakian, M., Gumbert, T., Di Giulio, A., Maniates, M., Lorek, S., et al. (2021). Consumption Corridors: Living a Good Life Within Sustainable Limits (London: Routledge), 112.

Garlet, T. B., de Medeiros, J. F., Ribeiro, J. L. D., and Perin, M. G. (2024). Understanding ethical products: definitions and attributes to consider throughout the product lifecycle. Sustain. Prod. Consumpt. 45, 228–243. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2024.01.010

Geiger, S. M., Fischer, D., and Schrader, U. (2018). Measuring what matters in sustainable consumption: an integrative framework for the selection of relevant behaviors. Sustain. Dev. 26, 18–33. doi: 10.1002/sd.1688

Ghali, Z. Z. (2021). Motives of ethical consumption: a study of ethical products' consumption in Tunisia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 12883–12903. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-01191-1

Godin, L., and Langlois, J. (2021). Care, gender, and change in the study of sustainable consumption: a critical review of the literature. Front. Sustain. 2:725753. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.725753

Godin, L., Smetschka, B., and Wahlen, S. (2025). Sustainable consumption and care. Front. Sustain. 6:1568396. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1568396

Goodman, M. K. (2010). The mirror of consumption: celebritization, developmental consumption and the shifting cultural politics of fair trade. Geoforum 41, 104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.08.003

Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., and Shaw, D. (2016). Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 136, 219–236. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2440-0

Hassan, S., Wooliscroft, B., and Ganglmair-Wooliscroft, A. (2023). Drivers of ethical consumption: insights from a developing country. J. Macromarket. 43, 175–189. doi: 10.1177/02761467231168045

Huddart Kennedy, E., Baumann, S., and Johnston, J. (2019). Eating for taste and eating for change: ethical consumption as a high-status practice. Soc. Forces 98, 381–402. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy113

Iran, S., and Müller, M. (2020). Social innovations for sustainable consumption and their perceived sustainability effects in Tehran. Sustainability 12:7679. doi: 10.3390/su12187679

Isenhour, C. (2010). On conflicted Swedish consumers, the effort to stop shopping and neoliberal environmental governance. J. Cons. Behav. 9, 454–469. doi: 10.1002/cb.336

Isenhour, C. (2012). “On the challenges of signalling ethics without the stuff: tales of conspicuous green anti-consumption,” in Ethical Consumption: Social Value and Economic Practice, 1st Edn, eds J. G. Carrier, and P. G. Luetchford (Berghahn Books), 164–180. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qcmfw.13 (Accessed June 17, 2022).

Johnstone, M. L., and Tan, L. P. (2015). Exploring the gap between consumers' green rhetoric and purchasing behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 132, 311–328. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2316-3

Jung, H. J., Kim, H. J., and Oh, K. W. (2016). Green leather for ethical consumers in China and Korea: facilitating ethical consumption with value–belief–attitude logic. J. Bus. Ethics 135, 483–502. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2475-2

Kahalzadeh, H. (2023). Civilian Pain Without a Significant Political Gain: An Overview of Iran's Welfare System and Economic Sanctions. Washington, DC: Johns Hopkins University.

Karimzadeh, S. (2022). Reflexive Consumption: A Study on Morality in Consumption. (1 Edn.). Teesa Publication, Iran.

Karimzadeh, S., and Boström, M. (2023). Ethical consumption in three stages: a focus on sufficiency and care. Environ. Sociol. 10, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2023.2277971

Karimzadeh, S., and Boström, M. (2024). Cross-cultural perspectives on ethical consumption: a study of Swedish and Iranian citizens. J. Cons. Cult. 0. doi: 10.1177/14695405241290920

Katz, L. (1996). Ill-Gotten Gains: Evasion, Blackmail, Fraud, and Kindred Puzzles of the Law. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Korsnes, M., and Solbu, G. (2024). Can sufficiency become the new normal? Exploring consumption patterns of low-income groups in Norway. Consump. Soc. XX, 1–18. doi: 10.1332/27528499Y2024D000000009

Kutaula, S., Gillani, A., Gregory-Smith, D., and Bartikowski, B. (2024). Ethical consumerism in emerging markets: opportunities and challenges. J. Bus. Ethics 191, 651–673. doi: 10.1007/s10551-024-05657-4

Kvale, S., and Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lekakis, E. J. (2012). Will the fair trade revolution be marketised? Commodification, decommodification and the political intensity of consumer politics. Cult. Org. 18, 345–358. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2012.728392

Li, Y., Wei, L., Zeng, X., and Zhu, J. (2020). Mindfulness in ethical consumption: the mediating roles of connectedness to nature and self-control. Int. Market. Rev. 38, 756–779. doi: 10.1108/IMR-01-2019-0023

Lyon, S. (2006). Evaluating fair trade consumption: Politics, defetishization and producer participation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 30, 452–464.

Mackendrick, N., and Stevens, L. M. (2016). “Taking back a little bit of control”: managing the contaminated body through consumption. Sociol. For. 31, 310–329. doi: 10.1111/socf.12245

Mason, J. (2017). Qualitative Researching, Qualitative Researching, 3rd Edn. Manchester University Press (MUP).

Mir Mohamad Tabar, S. A., Briscoe, M. D., and Sohrabi, M. (2024). Waste separation behavior in Iran: an empirical test of the theory of planned behavior using SEM. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 26, 1042–1055. doi: 10.1007/s10163-023-01881-8

Moosavi, M. S. (2005). “Bazaar and its role in the development of Iranian traditional cities,” in Conf. Proc. 2005 IRCICA Int. Conf. Islamic Archeology.

Newholm, T., Newholm, S., and Shaw, D. (2015). A history for consumption ethics. Bus. Hist. 57, 290–310. doi: 10.1080/00076791.2014.935343

Newholm, T., and Shaw, D. (2007). Studying the ethical consumer: a review of research. J. Cons. Behav. 6, 253–270. doi: 10.1002/cb.225

O'Connor, E. L., Sims, L., and White, K. M. (2017). Ethical food choices: examining people's fair trade purchasing decisions. Food Qual. Prefer. 60, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.04.001

Orlando, G. (2012). “Critical consumption in palermo: imagined society, class and fractured locality,” in Ethical Consumption: Social Value and Economic Practice, 1st Edn, eds J. G. Carrier, and P. G. Luetchford (Berghahn Books), 142–163. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qcmfw.12 (Accessed June 17, 2023).

Osburg, V. S., Strack, M., Conroy, D. M., and Toporowski, W. (2017). Unveiling ethical product features: the importance of an elaborated information presentation. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 1582–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.112

Pellandini-Simányi, L. (2014). “Ethical Consumerism and Everyday Ethics,” in Consumption Norms and Everyday Ethics (Palgrave Macmillan), 140–165. doi: 10.1057/9781137022509_6

Pourjafar, M., Amini, M., Varzaneh, E. H., and Mahdavinejad, M. (2014). Role of bazaars as a unifying factor in traditional cities of Iran: The Isfahan bazaar. Front. Architect. Res. 3, 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foar.2013.11.001

Princen, T. (1997). The shading and distancing of commerce: when internalization is not enough. Ecol. Econ. 20, 235–253. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(96)00085-7

Princen, T. (1999). Consumption and environment: some conceptual issues. Ecol. Econ. 31, 347–363. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00039-7

Rahmanian, E. (2023). Us and them! Consumer resistance as an act of antistate opposition in Iran. J. Cons. Behav. 23, 1478–1492. doi: 10.1002/cb.2284

Rebouças, R., and Soares, A. M. (2021). Voluntary simplicity: a literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Cons. Stud. 45, 303–319. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12621

Ryoo, Y., Sung, Y., and Chechelnytska, I. (2020). What makes materialistic consumers more ethical? Self-benefit vs. other-benefit appeals. J. Bus. Res. 110, 173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.019

Shaw, D., Chatzidakis, A., and Carrington, M. (2016). Ethics and Morality in Consumption. London: Routledge.

Shaw, D., Grehan, E., Shiu, E., Hassan, L., and Thomson, J. (2005). An exploration of values in ethical consumer decision making. J. Cons. Behav. 4, 185–200. doi: 10.1002/cb.3

Shove, E. (2003). Comfort, Cleanliness, and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality. Oxford: Berg.

Smith, A., and Johns, J. (2020). Historicizing modern slavery: free-grown sugar as an ethics-driven market category in nineteenth-century Britain. J. Bus. Ethics 166, 271–292. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04318-1

Stolle, D., and Micheletti, M. (2005). What Motivates Political Consumers? Forschungsjournal Neue Soziale Bewegungen 18, 41–52.

Summers, N. (2016). Ethical consumerism in global perspective: a multilevel analysis of the interactions between individual-level predictors and country-level afuence. Soc. Probl. 63, 303–328. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spw009

Timmermans, S., and Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociol. Theory 30, 167–186. doi: 10.1177/0735275112457914

Trnka, S., and Trundle, C. (2014). Competing responsibilities: moving beyond neoliberal responsibilisation. Anthropol. For. 24, 136–153. doi: 10.1080/00664677.2013.879051

Varul, M. Z. (2009). Ethical selving in cultural contexts: fairtrade consumption as an everyday ethical practice in the UK and Germany. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 33, 183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00762.x

Wiederhold, M., and Martinez, L. F. (2018). Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: the attitude-behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int. J. Cons. Stud. 42, 419–429. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12435

Keywords: care, mindful consumption, Iran, local moralities, everyday ethics

Citation: Karimzadeh S (2025) Consuming with care: insights into ethical consumption in Iran. Front. Sustain. 6:1540113. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1540113

Received: 05 December 2024; Accepted: 24 June 2025;

Published: 14 July 2025.

Edited by:

Elisabeth Süßbauer, Technical University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Alice Dal Gobbo, University of Trento, ItalyMarlyne Sahakian, University of Geneva, Switzerland

Copyright © 2025 Karimzadeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sara Karimzadeh, c2FyYS5rYXJpbXphZGVoQG9ydS5zZQ==

†ORCID: Sara Karimzadeh orcid.org/0000-0003-0154-7502

Sara Karimzadeh

Sara Karimzadeh