- 1Research Group Marketing & Customer Experience, Utrecht University of Applied Sciences, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 3Research Centre for Environmental Economics, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

Introduction: While consumers have become increasingly aware of the need for sustainability in fashion, many do not translate their intention to purchase sustainable fashion into actual behavior. Insights can be gained from those who have successfully transitioned from intention to behavior (i.e., experienced sustainable fashion consumers). Despite a substantial body of literature exploring predictors of sustainable fashion purchasing, a comprehensive view on how predictors of sustainable fashion purchasing vary between consumers with and without sustainable fashion experience is lacking.

Methods: This paper reports a systematic literature review, analyzing 100 empirical articles on predictors of sustainable fashion purchasing among consumer samples with and without purchasing experience, identified from the Web of Science and Scopus databases.

Results: The review revealed that (I) environmental cognition, such as environmental awareness, knowledge, and perceived consumer effectiveness, occurs most frequently as significant predictors for both groups; (II) subjective norms occur more frequently as significant predictors for general consumers than for experienced consumers; (III) habits occur more frequently as significant predictors for experienced consumers compared to general consumers; and (IV) experience can shift barriers into motivators.

Discussion: This review highlights experience as a transformative factor for sustainable fashion purchasing, showing that as consumers gain experience, their attitudes evolve and influence decisions. It also emphasizes the potential of goal framing, suggesting that effective goal frames can encourage initial sustainable fashion purchases among general consumers. From a practical perspective, this review suggests that marketers and retailers should employ distinct tactics for first-time and experienced sustainable fashion consumers to effectively engage each group and enhance purchasing.

1 Introduction

From 2000 to 2015, annual clothing sales doubled from 100 to 200 billion units, while the average number of times an item was worn decreased by 36% (Lai, 2021). The surge in consumption has resulted in an alarming increase in clothing-related waste, totaling 92 million tons each year (Lai, 2021). In response, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #12, part of the Agenda 2030, prioritizes a more sustainable approach to fashion production and consumption (UNEP, 2023). Achieving SDG 12 requires a fundamental change in consumption patterns and a consumer shift toward prioritizing sustainable fashion (SF) over fast fashion (Coscieme et al., 2022; UNEP, 2023).

To motivate a shift in consumption patterns toward SF, it is crucial to understand the social-psychological predictors that influence consumer behavior (Busalim et al., 2022). Social-psychological predictors, such as attitudes and norms, play a key role in shaping behavior and offer insights for strategies aimed at increasing SF adoption (Lundblad and Davies, 2016). While numerous studies have explored these predictors and their influence on consumers' intentions to buy SF (Dabas and Whang, 2022), intentions do not always result in actual purchasing behavior—a phenomenon known as the intention-behavior gap (Dabas and Whang, 2022; McKeown and Shearer, 2019).

The transition from mere intention to actual purchasing behavior is marked by experience with SF, such as making a purchase from an SF brand or renting an outfit. It appears that experience with SF positively shifts consumer perceptions of these products and increases the likelihood of future purchases. A lack of firsthand experience often results in negative perceptions of SF (Silva et al., 2021), while experienced consumers tend to have positive perceptions, associating sustainability with style, quality, and wellbeing (Bly et al., 2015). Furthermore, experienced SF consumers are more likely to consider the entire life cycle of their purchases, while general consumers typically focus only on the initial acquisition (Lundblad and Davies, 2016). Understanding how predictors of SF purchasing differ between consumers with and without experience is essential for designing tailored strategies that effectively promote SF adoption across both groups.

Although only one empirical study has directly compared SF purchasing between general and experienced SF consumers, it shows that experienced consumers exhibit greater fashion consciousness, environmental concern, perceived consumer effectiveness, and stronger subjective norms than general consumers (Riesgo et al., 2023). Existing reviews on SF purchasing have primarily focused on specific types of SF such as collaborative consumption (Arrigo, 2021) or specific predictors like the influence of social media on SF consumption (Vladimirova et al., 2024). Notably, no review has yet examined the predictors of SF purchasing in a comparative manner between consumers with and without SF experience. Addressing this gap will deepen our understanding of SF behavior and better understand how to bridge the intention-behavior gap of SF purchasing.

This study addresses the need for a comprehensive view on predictors influencing SF purchasing, specifically distinguishing between consumers who have converted their intentions into actual purchases and those who have not. Through a systematic literature review, this study aims to answer the research question “How do the predictors of SF purchasing vary between consumers with and without experience with SF?” Utilizing descriptive and thematic analyses, this study synthesizes existing literature to enhance our understanding of these predictors, compare the two consumer groups, and propose future research directions. By identifying key predictors for both consumer groups, this study provides theoretical insights into the transformative factors encouraging SF purchasing behavior. It highlights relevant avenues for future research and provides practical recommendations for practitioners to develop targeted marketing strategies to encourage consumers to translate their intentions into actual purchases, ultimately contributing to achieving SDG 12.

2 Scope of the review and definitions

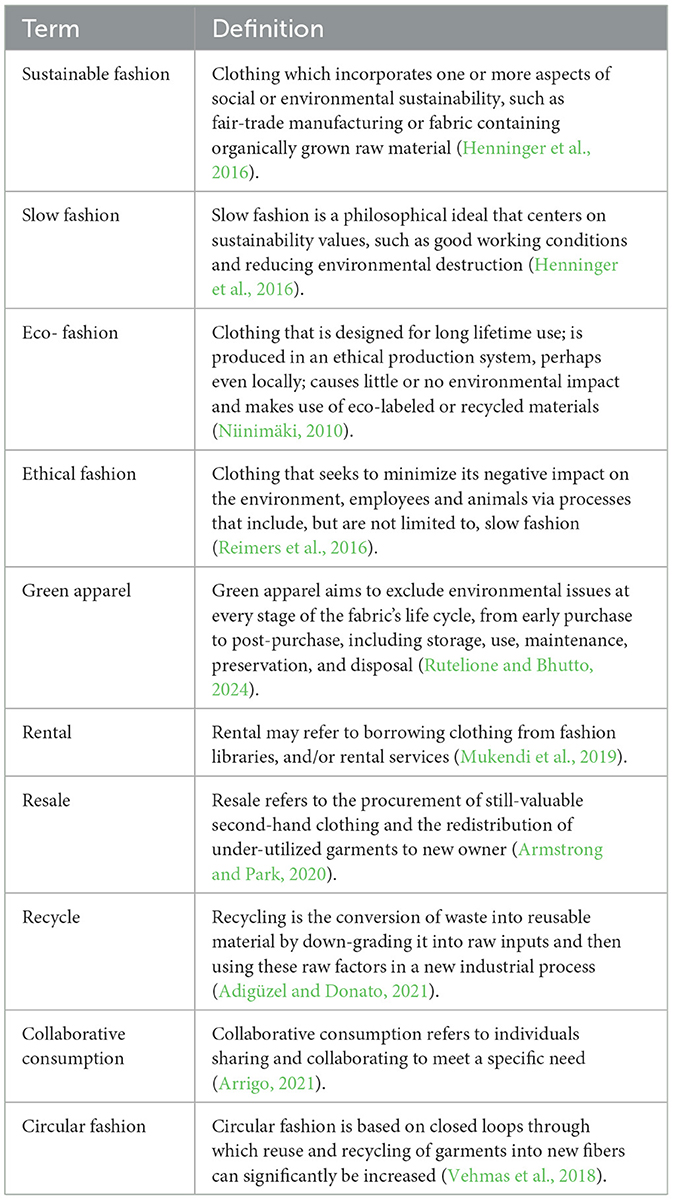

As sustainability in the fashion industry continues to evolve, exact definitions of SF remain fluid and subject to change (Vladimirova et al., 2024). Terms such as slow fashion, eco-friendly fashion, ethical fashion, and green fashion are often used interchangeably with SF, despite nuanced differences in practice (Henninger et al., 2016; Mukendi et al., 2019). Moreover, SF encompasses various consumption practices (Vladimirova et al., 2024), such as Rental (e.g., renting clothes from Rent the Runway), Resale (e.g., purchasing second-hand fashion on Vinted), and Recycling (e.g., purchasing Stella McCartney clothing made from recycled water bottles). Resale and Rental are also referred to as Collaborative consumption (Iran and Schrader, 2017), and Recycled fashion is sometimes referred to as Circular fashion (Vehmas et al., 2018).

For the purpose of this review, purchasing SF is defined as the acquisition of sustainable fashion, slow fashion, eco-friendly fashion, ethical fashion, green apparel, rented fashion, second-hand fashion, recycled fashion, collaborative consumption, circular fashion, or related concepts with similar objectives. For definitions of SF terminology in literature, see Table 1. Strategies that do not involve purchasing SF, such as Refuse or Repair, are not within the scope of this study.

3 Methods

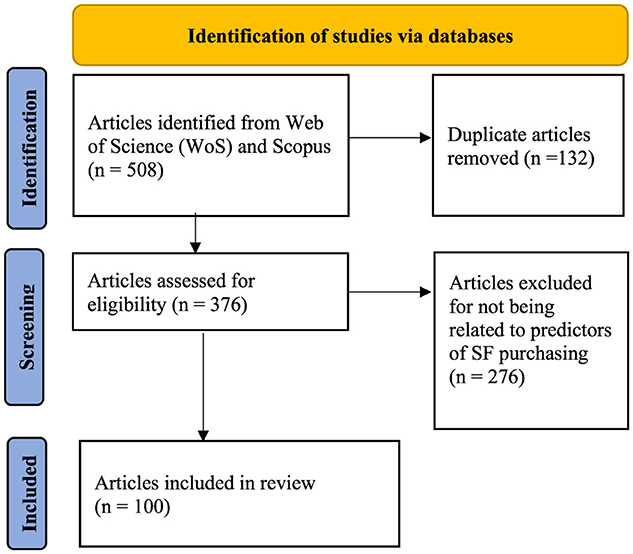

A systematic literature review was conducted to investigate the predictors of SF purchasing for consumers with and without experience. This review adheres to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). This rigorous approach is structured into stages of identification, screening and inclusion, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for this review (adapted from Moher et al., 2009).

The lead researcher's professional background in the fashion industry may have influenced initial interpretations of the data. To minimize potential bias during identification, screening, and data synthesis, several strategies were implemented. First, the research team collaboratively discussed and refined inclusion and exclusion criteria (detailed below). Next, predictors were coded using a data-driven iterative approach to reduce interpretive bias. Ambiguous cases (e.g., predictors that fit multiple codes) were resolved through team discussions, ensuring alignment with evidence rather than individual perspectives.

3.1 Identification

Based on the research question, a search string was developed, focusing on key words related to predictors to purchase SF: (“consumer”) AND (“predictor*” OR “antecedent*” OR “buy*” OR “purchase*” OR “behavior” OR “behavior”) AND (“fashion” OR “apparel” OR “cloth*”) AND (“sustain*” OR “slow” OR “eco-friendly” OR “ethical” OR “green” OR “rent*” OR “resale” OR “second-hand” OR “collaborative consumption” OR “recycled” OR “circular”). Keywords such as “motivators” or “barriers” were excluded to prevent narrowing the search scope. Additionally, we did not include “experience” as a keyword in the search string, as we aimed to categorize the research samples in the reviewed articles by experience. This approach allowed us to capture a broader and potentially richer set of articles, covering predictors to purchase SF influenced by experience without limiting the focus to experience as a central concept.

The search was conducted in January 2024 using Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, two bibliographic databases well-suited for scientific research that include high-impact peer-reviewed journals (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2020). Since 2018, SF research has expanded rapidly, with a notable shift beginning in 2019 toward understanding purchasing behaviors and exploring the intention-behavior gap (Arrigo, 2021; Busalim et al., 2022). Around this time, mainstream brands began offering sustainable alternatives that increased consumer awareness, while technological advancements and the expansion of SF options— particularly in the Resale sector—made SF more accessible (Busalim et al., 2022). Given the rapid changes in SF, it is important to recognize that predictors of SF behavior measured in earlier studies may no longer accurately reflect current trends and motivations. To provide an up-to-date analysis of predictors influencing current SF purchasing behavior, this review focuses on articles published between 2019 and 2023.

An advanced search was conducted in WoS categories Business, Environmental Sciences, Environmental Studies, Communication, Psychology, Psychology multidisciplinary, and Psychology applied. In the Scopus database a search was performed in the title, keywords, or abstracts within the categories Environmental Sciences and Psychology. These categories were selected as they encompass a wide range of disciplines that investigate social-psychological predictors. In both databases, review articles and conference papers were excluded, allowing the focus to remain solely on empirical, peer-reviewed journal articles to ensure the quality of the selected works. Quantitative research articles were included for their insights into tested effects, while qualitative research articles were incorporated for their broader and deeper perspectives on SF purchasing. This search strategy resulted in the identification of 508 articles: 223 from WoS and 285 from Scopus. After removing duplicates, 376 unique articles remained.

3.2 Screening

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to ensure the selection of articles was relevant to this review. As this review focuses on social-psychological predictors to purchase SF, the main inclusion criterion was that the study tests one or more social-psychological predictors of SF purchasing. All 376 articles were carefully reviewed, resulting in the exclusion of 276 articles that were not related to the predictors of SF purchasing. These excluded articles focused on topics such as selling second-hand luxury (Turunen et al., 2020), predictors of purchasing fast fashion (Cayaban et al., 2023), how fashion brands move toward circularity (Brydges, 2021), or how to promote repair (Laitala et al., 2021). In addition, non-empirical articles were excluded (see Figure 1). Ultimately, 100 articles were included in the final review sample.

3.3 Data synthesis

The full text of each article was read and relevant information was extracted through charting, a technique for organizing data by sifting and sorting material according to key descriptors and themes (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005). From the included articles, the following information was coded: the specific SF terminology used (e.g., SF or Rental), geographical context (where the study was conducted), the research method (e.g., quantitative or qualitative), and the dependent variable (e.g., intention or behavior). This helped us identify dominant research areas in the field and contextualize the output. Some articles did not clearly describe all these aspects, resulting in missing codes for those entries.

Next, references to experience with SF consumption were examined in the sample descriptions of the dataset to code the sample type. Articles that focused explicitly on experienced consumers were coded as such. Examples include articles on customers of second-hand clothing stores (de Groot, 2021; Lichy et al., 2023), Facebook groups for second-hand clothes (Corboş et al., 2023), or apparel consumers who participated in the study only after confirming they had purchased green apparel at least once in the previous 6 months (Tandon et al., 2023). Articles coded into the general consumer category were articles that did not explicitly define or measure prior experience with SF. These articles typically focused on the general population or specific consumer segments, for example Generation Z (Pradeep and Pradeep, 2023), without considering their history of SF purchasing. Therefore, the general consumer group likely included a mix of individuals with varying levels of SF experience, ranging from inexperienced consumers to those with some experience, although this experience was not a measured variable. It is important to note that no articles explicitly investigated inexperienced consumers as a distinct group. Articles focusing on generic, general, average, or unspecified consumers were classified as general consumer samples. For example, one study explicitly stated to target a general sample by stating “the population of interest are consumers in general, without age, sex, or specific behavior restrictions, whether they frequent second-hand stores or not” (Amaral and Spers, 2022). However, the majority focused on consumer segments without referring to experience with SF, such as potential luxury consumers (Adigüzel and Donato, 2021). Finally, three articles comparing general and experienced consumers (for e.g., Riesgo et al., 2023) included separate studies for both groups. This resulted in 103 coded studies from 100 articles. Here, “articles” denote individual publications, while “studies” represent distinct research comparisons within them. Supplementary material provides a comprehensive overview of the references for all articles included in the review, detailing the research methods employed and the characteristics of the research samples.

Subsequently, the social-psychological predictors from each article were coded. Inductive coding, a data-driven approach suitable for identifying emerging concepts (Braun and Clarke, 2013), was used. In quantitative articles, significant predictors were coded; in qualitative research articles, predictors that the authors of those articles deemed relevant or meaningful to SF purchasing, even if not statistically measured, were coded. Additionally, the evidence identified was coded as either a motivator or barrier to purchasing SF. For example, treasure hunting was coded as a motivator when mentioned as a reason for purchasing SF in the article.

Next, an iterative approach was taken to group the predictors into higher-order themes through thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2013), allowing themes to emerge and evolve throughout the process. Codes with similar semantic meanings were grouped, ensuring that the themes were mutually exclusive and reflected the predictors identified in the articles under review. For example, “price” and “willingness to pay” were categorized under the higher-order theme “economic motivations,” while “environmental awareness” and “knowledge” fell under the theme “environmental cognition.” Importantly, these themes emerged from iterative grouping based on meaning rather than solely relying on previously established classifications from the literature, even though some themes have been recognized in prior research (e.g., Ferraro et al., 2016). Three concepts were coded only once and could not be logically grouped into higher-order themes; for example, mindfulness. Therefore, they were excluded from the analysis.

Finally, the number of codes per theme of predictors was counted for both consumer groups. These counts reflect the prevalence of significant or relevant predictors in the current literature. This study interprets these counts in relative terms; a higher count for a particular theme of predictors indicates greater prevalence of significance within the context of this review.

4 Results

This section presents the results of the descriptive analysis of the articles (4.1), followed by the results of the thematic analysis (4.2).

4.1 Descriptive results

Of the articles in the review sample, (n = 81) articles focused on general consumers, while (n = 16) articles focused on experienced consumers. The difference in the number of articles created an imbalance in the amount of evidence for the two sample groups, which should be considered when interpreting the review results. Three articles in the sample contained both general and experienced consumers.

Figure 2 illustrates the SF terminology used in the articles within the review sample. Most articles involving general consumers referred to SF (n = 41), while Resale was focused on most by articles involving experienced consumers (n = 8). Two articles initially coded as Collaborative consumption were recategorized as Rental upon review, based on their research focus (Chi et al., 2023). One article reported on Rental, Recycled, and Resale (Lin et al., 2023), and these were attributed to all three SF concepts. Notably, there were no articles on experienced consumers that investigated purchasing Slow fashion, Eco-friendly fashion, Ethical fashion, Recycled fashion, or Circular fashion.

Figure 3 displays the geographical distribution of the 100 research articles included in the review across 34 countries. While it shows an acceptable distribution across most continents, research from the African continent is notably absent. The majority of articles on general consumers were conducted in the USA (n = 17), China (n = 14), Germany (n = 6), Brazil (n = 4), the UK (n = 4), and Italy (n = 4). Articles on experienced consumers were primarily conducted in the USA (n = 4), China (n = 4), and Japan (n = 2). Most articles on general consumers focused on a single country, with a smaller number conducted in two or three countries (n = 6). All articles on experienced consumers were based in a single country.

Figure 3. Geographical focus of the articles in the dataset (covering 106 countries in 100 articles).

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of research methods identified in the articles in the review sample. For both sample groups, the majority of articles employed quantitative research methods: (n = 74) articles for general consumers and (n = 10) articles for experienced consumers. Among these, surveys were frequently used, for example, to test predictors to buy on Resale platforms (Styvén and Mariani, 2020). Qualitative articles predominantly adopted interviews to explore SF purchasing behaviors, for example investigating ethical consumption among Generation Z (Djafarova and Foots, 2022). Only seven of the 100 articles employed mixed methods, for example, combining approaches such as participant observation and interviews (Waight, 2019).

Finally, in 69% of the articles on general consumers, the intention to purchase SF was investigated. For example, Abrar et al. (2021) used the Theory of Planned Behavior to study the purchase intentions among Generation Y and Z. In contrast, 63% of the articles on experienced consumers focused on SF purchasing behavior. For instance, how mothers with Resale experience buy and sell second-hand children's clothing (Waight, 2019). Additionally, five articles on general samples addressed both intention and behavior, such as qualitative research on converting purchase intention into behavior (Djafarova and Foots, 2022), and these were categorized under both intention and behavior.

4.2 Results of the thematic analysis

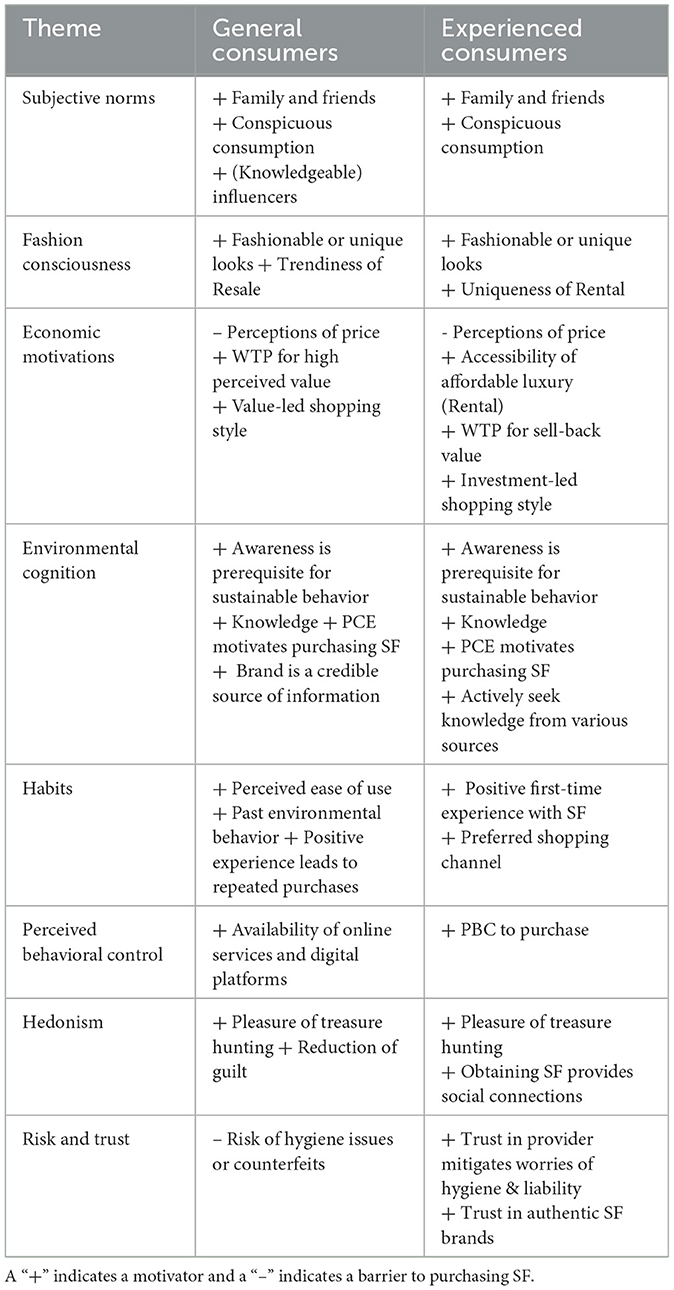

In this section, we present the results from the thematic analysis. Across the 100 articles in the review sample, we identified eight themes of social-psychological predictors of SF consumption: Subjective norms, Fashion consciousness, Economic motivations, Environmental cognition, Habits, Perceived behavioral control (PBC), Hedonism, and Risk and trust. Figure 5 illustrates the key findings: (I) environmental cognition, such as environmental awareness, knowledge, and perceived consumer effectiveness, occurs most frequently as significant predictor for both groups; (II) subjective norms occur more frequently as significant predictors for general consumers than for experienced consumers; (III) habits occur more frequently as significant predictors for experienced consumers compared to general consumers; and (IV) experience can shift barriers into motivators.

Figure 5. Overview of themes of predictors identified in this review, showing the distribution of codes for general and experienced consumer samples across these predictors. Percentages indicate the proportion of codes assigned to each theme relative to the total number of codes generated.

Table 2 provides a summary of the key social-psychological predictors for each theme, additionally indicating whether the evidence identified served as a motivator (indicated by “+”) or barrier (indicated by “–”) to purchasing SF. The predominance of motivators in the findings may reflect the literature's focus on motivators.

The following sections will define each theme and explain the significant or relevant predictors of purchasing SF among general and experienced consumers.

4.3 Subjective norms

Subjective norms, also referred to as social norms, refer to the perceived social influence or pressure from relevant others to engage in specific behaviors (La Rosa and Johnson Jorgensen, 2021). For both sample groups, subjective norms were found to influence purchasing SF (Leclercq-Machado et al., 2022; Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). Two types of subjective norms can be distinguished: descriptive norms, which refer to what others do, and injunctive norms, which pertain to behaviors that are commonly expected (i.e., approved or disapproved) (Ahn et al., 2020). Across both sample groups, the majority of the subjective norms codes focused on descriptive norms, such as how consumers are influenced by family and friends (La Rosa and Johnson Jorgensen, 2021; Zahid et al., 2021). Only articles focused on general consumers addressed the influence of social media influencers. These articles showed that influencers could significantly impact attitudes toward purchasing SF, especially when they are perceived as knowledgeable about SF (Johnstone and Lindh, 2022).

In both sample groups, articles were found referring to conspicuous consumption, which involves purchasing and displaying products to show wealth, status, or social position (Apaolaza et al., 2023; Waight, 2019). Conspicuous consumption was coded as subjective norms, as it reflects the influence of societal expectations and the desire to align with social standards. For instance, individuals may choose SF products to create and maintain a desirable public image (Lou et al., 2022) or to impress others by renting an outfit for a special event to demonstrate social status (Pantano and Stylos, 2020).

4.4 Fashion consciousness

Fashion consciousness refers to an individual's interest in, and awareness of, the latest trends and new styles in fashion (Lee et al., 2020b). Both sample groups are interested in purchasing SF products if these items are fashionable or provide unique looks, even if consumers do not prioritize sustainability in their choice for SF (Lee et al., 2020b; Riesgo et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). For example, fashion consciousness has driven general consumers to embrace Resale since it was perceived as a fashion trend (Amaral and Spers, 2022), and experienced consumers to embrace Rental due to the opportunity to enhance variety and uniqueness in their looks and the chance to never wear the same dress twice (Ruan et al., 2022; Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). In a comparison between experienced consumers and general consumers, it was found that experienced consumers demonstrate greater fashion consciousness than general consumers (Riesgo et al., 2023).

4.5 Economic motivations

In this review, economic motivations encompass price and willingness to pay (WTP). Price is a critical factor for both sample groups (Djafarova and Foots, 2022; Stolz, 2022). While both sample groups perceive SF as expensive (Lin et al., 2023; Tandon et al., 2023), they are both attracted to Resale due to the lower prices, which enable them to acquire clothing from prestigious brands at reduced costs and to increase their shopping volume (Rodrigues et al., 2023; Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). Research on general consumers has shown that price is considered more important than sustainability when purchasing SF (Helinski and Schewe, 2022; Pradeep and Pradeep, 2023).

WTP assesses the price a consumer is willing to pay relative to the perceived value of a product (Dangelico et al., 2022). Perceived value is the consumer's assessment of the benefits of a product or service, including environmental, monetary, and psychological advantages (Choi and Ahn, 2023; Pandey et al., 2020). Research on general consumers shows that they are willing to pay more for products perceived as novel (Chen et al., 2021) or scarce (Seo et al., 2023). Such WTP reflects the value, emotional appeal, and status associated with these items, suggesting a value-led shopping style. Conversely, research on experienced consumers indicated higher WTP for branded products, as these items retain their value and can be resold through online resale channels after use (Waight, 2019), indicating an investment-led shopping style.

4.6 Environmental cognition

In this review, the term Environmental cognition refers to key drivers rooted in environmental and ecological awareness, along with a commitment to critical and ethical consumption practices. It encompasses environmental awareness, knowledge, and perceived consumer effectiveness.

Firstly, environmental awareness involves understanding the social and environmental impacts of mass production and consumption (Kleinhückelkotten and Neitzke, 2019; Lee et al., 2020a). Environmental awareness is also referred to as environmental concern (Ceylan, 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2023) or environmental consciousness (Lou et al., 2022; Yoo et al., 2021). While awareness alone may be insufficient, it is often considered a prerequisite for sustainable behavior for both sample groups (Pang et al., 2022). For example, more environmentally aware consumers tend to buy less brand-new fashion, preferring alternatives such as Resale and Rental (Riesgo et al., 2023).

Secondly, knowledge encompasses a comprehensive understanding of SF. In the review sample, references were made to consumer knowledge (Lionço et al., 2019), product knowledge (Lang et al., 2019), and environmental knowledge, significantly influencing attitudes and leading to SF purchasing for both sample groups (Abrar et al., 2021; Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). For example, knowledge about which materials can be upcycled in fashion impacts the intention to purchase upcycled fashion products (Yoo et al., 2021). However, the sample groups differ in how they acquire information: general consumers may view brands as credible sources of information (Day et al., 2020), while experienced consumers actively seek sustainability knowledge from various sources (Zhang et al., 2023).

Thirdly, perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE) describes the likelihood of individuals purchasing SF when they believe their purchasing decisions can make a tangible difference (La Rosa and Johnson Jorgensen, 2021; Lionço et al., 2019). Experienced consumers were found to have higher PCE than general consumers (Riesgo et al., 2023). Moreover, experienced consumers' strong environmental concerns lead them to act positively toward sustainable purchases without needing to consider their capability to make a difference (Tandon et al., 2023).

4.7 Habits

Habits are cognitive structures that automatically guide future behavior by linking specific situational cues to behavioral patterns (Klockner and Verplanken, 2019). In this review, habits encompass past sustainable behavior and ease of purchasing. Habitual behavior requires minimal attention. However, changing habitual consumption patterns and switching to purchasing SF necessitates attention and a strong willingness to change (La Rosa and Johnson Jorgensen, 2021).

Research on general consumers showed that ease of use facilitates online SF shopping (Park et al., 2022; Shrivastava et al., 2021). While past sustainable behavior may influence the initial intention to buy SF (Chi et al., 2023), a positive SF experience often leads to repeated purchases in the future (Stolz, 2022; Styvén and Mariani, 2020). Moreover, articles on experienced consumers indicate that the first-time experience with SF is critical for customer retention (Liu et al., 2023) and establishing a new shopping routine (Dhir et al., 2021). While some experienced consumers prefer shopping second-hand in physical stores (Zhang et al., 2023), others favor shopping online, whether occasionally or frequently (Corboş et al., 2023; Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). In either case, when consumers start to engage in second-hand purchases, they often begin promoting the exchange of used clothing in others too (Machado et al., 2019).

4.8 Perceived behavioral control

Perceived behavioral control (PBC) is a concept within the Theory of Planned Behavior and refers to an individual's perception of their ability to successfully perform a particular behavior (La Rosa and Johnson Jorgensen, 2021; Lionço et al., 2019). PBC in the context of purchasing SF can be understood through factors such as availability (i.e., the availability of SF products), ability (i.e., knowing where to go), and opportunity (i.e., situational factors that enable or facilitate the purchase of SF, such as time, attention, and the absence of distractions) (Hasbullah et al., 2022).

PBC was coded as a motivator for experienced consumers, who are well-informed about SF and make informed conscious purchasing decisions (Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). They are not deterred by the usual time and cost associated with sustainable consumption. The effort they invest in researching fabrics, brands, and limited availability of natural materials, is outweighed by benefits such as unique designs, timeless cuts, higher quality, and longer-lasting textiles.

4.9 Hedonism

Hedonism reflects a care for comfort and the enjoyment of life. In the context of purchasing SF, hedonistic values manifest as self-gratification through the pleasure of shopping, fulfilling fashion desires, and exploring new clothing styles (Wang et al., 2021).

For both sample groups, hedonic value was found to positively influence purchasing SF (Lou et al., 2022; Pantano and Stylos, 2020). For example, SF shopping satisfies a recreational desire in the form of treasure hunting or, more specifically, bargain hunting or vintage shopping. Bargain hunting offers hedonic pleasure by providing opportunities to purchase rare outfits at reduced prices, while vintage shopping is associated with nostalgic pleasure and an appreciation for the history of previous owners (Styvén and Mariani, 2020).

For experienced consumers, hedonic motivations sometimes outweigh environmental benefits (Liu et al., 2023). For instance, the low price of Resale can lead to desire-driven rather than need-driven consumption (Waight, 2019). Additionally, the social value of engaging in SF, such as attending SF events, repair cafes, or swap sessions, fosters connections with like-minded people, enhancing pleasure and enjoyment of life (Machado et al., 2019).

Conversely, articles on general consumers report lower hedonic value for luxury SF products. For example, the sustainable features of luxury products may diminish consumers' pleasure, as they feel less guilt after purchasing sustainable luxury but do not necessarily experience increased pleasure (Alghanim and Ndubisi, 2022). Additionally, luxury consumers tend to be more critical about the type of SF; for instance, luxury consumers might attribute stronger feelings of pride and greater novelty to upcycled goods compared to recycled goods (Adigüzel and Donato, 2021).

4.10 Risk and trust

When purchasing SF, risk refers to the concern that the purchase may not meet expectations (Yoo et al., 2021), while trust involves believing in the other party's credibility, benevolence, or environmental responsibility (Apaolaza et al., 2023).

Research on risks primarily focused on general consumers and showed that risk perception has a negative impact on SF purchasing (Lin and Chen, 2022). Examples of perceived risks include hygiene concerns (Xu et al., 2022) and the fear of purchasing counterfeits in Resale markets (Stolz, 2022). In articles originating from the USA, risk did not affect consumers' purchasing second-hand luxury products, possibly indicating that its second-hand luxury market is well-established and that consumers can easily access and compare information to evaluate product authenticity and quality (Lou et al., 2022).

For both sample groups, trust in the SF brand or provider is a significant factor shaping SF consumption (Pang et al., 2022; Riesgo et al., 2023). Trust reduces skepticism about greenwashing practices (Apaolaza et al., 2023) and alleviates concerns about wearing used clothing and financial liability for product damage in rental scenarios (Day et al., 2020). For general consumers, the influence of sustainable aspects on purchasing decisions is minimal when trust in the brand is already high (Riesgo et al., 2023). In contrast, experienced consumers trust brands that engage in sustainability out of genuine commitment rather than for profit or other self-interested motives, valuing authenticity (Riesgo et al., 2023).

5 Discussion and proposed future research directions

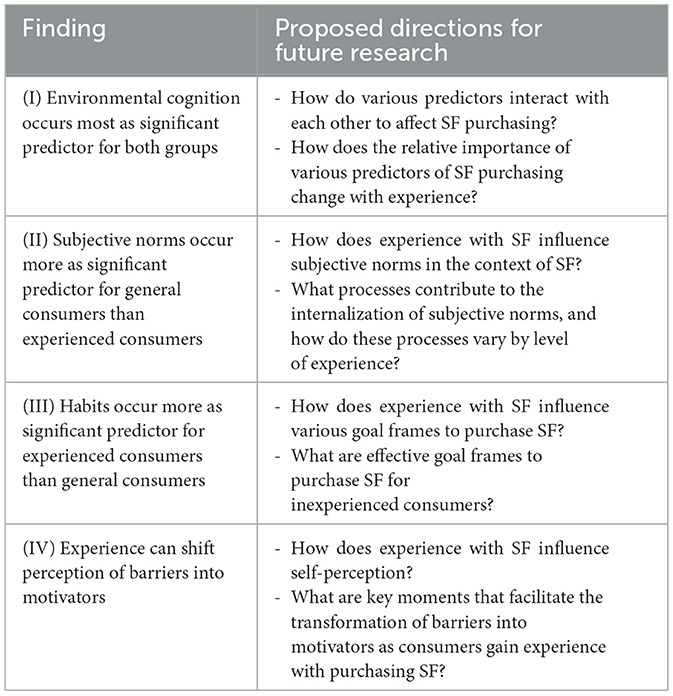

This systematic literature review aimed to investigate how the predictors of SF purchasing differ between consumers with and without SF experience. A total of 100 articles were analyzed, beginning with a descriptive analysis to provide context for the dataset. This initial analysis revealed a predominant focus on general consumers over experienced ones, and a greater emphasis on purchase intention rather than actual purchasing behavior. Next, through a thematic analysis eight themes of social-psychological predictors of SF purchasing were synthesized, allowing for a comparative examination of these predictors across the two consumer groups. This revealed that (I) environmental cognition, such as environmental awareness, knowledge, and perceived consumer effectiveness, occurs most frequently as significant predictor for both groups; (II) subjective norms occur more frequently as significant predictors for general consumers than for experienced consumers; (III) habits occur more frequently as significant predictors for experienced consumers compared to general consumers; and (IV) experience can shift barriers into motivators. These findings are discussed in greater detail below, along with proposed directions for future research, and are summarized in Table 3.

(I) Environmental cognition: The findings indicate that environmental cognition—including environmental awareness, knowledge, and perceived consumer effectiveness — occurs most as significant driver of SF purchasing among both general and experienced consumers in this review. While these motivations serve as a rational starting point for sustainable choices, it is essential to acknowledge that fashion consumption often deviates from purely rational processes. Emotional and contextual factors play a substantial role in influencing consumer choices (Busalim et al., 2022; Niinimäki, 2010). Although environmental cognition is valuable for initiating discussions around SF consumption, evidence suggests that interventions focusing solely on these aspects often overlook the complex interplay of emotional and social influences that more effectively drive actual purchasing behavior (Albarracín et al., 2024). This complexity is underscored by the diverse themes of predictors identified in this review, each supported by significant research findings. Therefore, appealing exclusively to environmental cognition may not bridge the gap between intention and actual behavior (Busalim et al., 2022). Future research should explore how other predictors operate alongside environmental cognition. Investigating various predictors simultaneously could yield a more holistic understanding of SF purchasing behavior, highlighting the relative influence of each predictor.

(II) Subjective norms: The comparison of general and experienced samples reveals that there is more significant evidence that general consumers are influenced by subjective norms, such as the perceived expectations of friends and family, than experienced consumers (Leclercq-Machado et al., 2022; Slaton and Pookulangara, 2022). This finding aligns with the sole study comparing general and experienced consumers, which showed that while experienced consumers feel pressure to act sustainably, it stems more from internal moral obligations than from external social influences (Riesgo et al., 2023). This suggests that subjective norms create external pressure on inexperienced consumers to adopt SF practices, such as purchasing SF for social approval. With experience, some of these norms may be internalized, shaping individuals' beliefs and motivations. For instance, an experienced consumer may choose to buy SF because it resonates with their personal values, rather than out of concern for social disapproval (Legros and Cislaghi, 2020). This highlights the need for research that distinguishes between general and experienced consumers regarding the internalization of subjective norms into moral obligations. Future research should consider comparing predictors across these consumer groups and may employ experimental methods to explore how subjective norms operate at different levels of experience with SF.

(III) Habits: The comparison of the two consumer groups indicates that there is more significant evidence that experienced consumers are influenced through their habits — for example, their previous engagement in environmental behavior (Stolz, 2022) and the ease of purchasing SF—than general consumers. While retaining SF consumers is essential for promoting ongoing sustainable consumption (Liu et al., 2023), it appears that after making an initial purchase, these consumers tend to develop a more positive perception of SF (Silva et al., 2021). This suggests that experience shapes how consumers frame their sustainable choices, potentially leading to different purchasing goals. Goal framing theory posits that the way goals are presented can significantly influence consumer behavior and decision-making (Lindenberg and Steg, 2007). For instance, experienced consumers who have developed habits around sustainable practices are more likely to engage in sustainable consumption as their goals to purchase SF are framed positively or as moral imperatives (Van Der Weiden et al., 2020). In contrast, inexperienced consumers may struggle to form these habits without clear and compelling goal framing, highlighting the potential of effective goal framing in promoting sustainable consumption. Therefore, future research should investigate effective goal framing strategies for inexperienced consumers to facilitate SF purchasing.

(IV) From barriers to motivators: This review revealed that certain predictors, which initially serve as barriers for general consumers, can become motivators for experienced consumers. This shift aligns with prior research (Silva et al., 2021). For example, in the context of the theme hedonism, general consumers do not expect to derive additional pleasure from purchasing SF; instead, they primarily expect to feel less guilt (Alghanim and Ndubisi, 2022). In contrast, experienced consumers report deriving greater pleasure in SF purchasing, such as through social connections formed while purchasing and trading SF (Machado et al., 2019). These findings align with self-perception theory (Bem, 1972), which posits that individuals develop attitudes and beliefs by observing their behaviors within specific contexts. As consumers engage more deeply with SF, their experiences may prompt them to reinterpret their motivations and identities, underscoring the dynamic nature of self-perception. Future research should further investigate this dynamic, focusing on the cognitive and emotional changes that occur as consumers gain experience with SF. A longitudinal study design could be particularly valuable in exploring how barriers evolve into motivators by tracking changes in self-perception over time with repeated purchases or deeper engagement with SF.

5.1 Contribution to theory and practice

This systematic literature review provides a significant theoretical contribution by elucidating what is known about the differences in predictors of SF purchasing between general consumers and those with prior experience. The key theoretical contribution is the identification of experience as a transformative factor in SF purchasing behavior. Experience acts as a tipping point in the shift from external influences to internalized motivations. As consumers gain experience, their self-perception evolves, directly impacting their purchasing behavior. This dynamic challenges the traditional Theory of Planned Behavior, which posits that attitudes influence behavior. In the context of SF purchasing, however, it is behavior that shapes attitudes. This aligns with research demonstrating that consumers' purchasing behaviors actively contribute to the formation of new attitudes, reinforcing the notion that behavior can precede and modify intent (Sommer, 2011). Furthermore, this review highlights the potential of goal framing within the context of SF. Experienced consumers develop effective goal frames that facilitate ongoing SF purchasing habits, while general consumers often lack these. Consequently, this review contributes by recommending further investigation into effective goal frames that can motivate consumers to make their initial SF purchase.

From a practical perspective, this review offers recommendations for SF marketers, communicators, and retailers. As consumer perceptions of SF change with experience, the findings suggest that distinct marketing and communication strategies should be used for first-time consumers and experienced consumers. Environmental cognition serves as key predictor for both consumer groups; however, they require different approaches to engage each consumer group. First-time consumers require clear, brand-driven education to build trust. Patagonia's Worn Wear program exemplifies this through accessible repair guides and transparent product lifecycle information, directly addressing newcomers' need for foundational knowledge (www.wornwear.patagonia.com). To standardize such efforts, EU Green Claims Directive compliance becomes essential—mandating verified sustainability labels to prevent greenwashing and enable informed comparisons. Governments could incentivize this through tax breaks for brands adopting standardized labeling aligned with Directive requirements. Experienced consumers demand depth and authenticity. Partnerships with documentary filmmakers (e.g., The True Cost screenings) can engage this group's preference for systemic analysis while fostering community. Brands could integrate Directive-compliant substantiation into these efforts, for instance, pairing film discussions with granular data on supply chain emissions reduction, verified through third-party audits.

6 Limitations

While this literature review has provided valuable insights, the study does have some limitations. The first limitation is that most articles relied on quantitative methods, particularly surveys, to examine predictors of consumer behavior. While these methods align with consumer behavior research traditions (Arrigo, 2021; Busalim et al., 2022), survey scales often employ vague frequency measures that may overstate links between motivations and behaviors (Nielsen et al., 2023). Additionally, self-reported questionnaires are susceptible to biases such as social desirability and recall issues, which can lead respondents to overstate intentions or inaccurately recall behavior (Nielsen et al., 2023). Consequently, conclusions drawn from quantitative data may not accurately reflect true intentions or behaviors. Qualitative approaches are better suited to uncover deeper social and psychological predictors, providing richer, culturally sensitive insights into the complexities and underlying motivations of SF purchasing (Lloyd and Gifford, 2024). To address this limitation, this review included both qualitative and quantitative articles on SF purchasing to provide context that surveys alone might miss. Future research should prioritize qualitative approaches, such as interviews and focus groups, to engage consumers directly and uncover the motivations and barriers shaping actual SF purchasing behavior.

A second limitation is the imbalance between articles that focus on experienced consumers and those that do not, particularly regarding how behavior is measured. For general consumers, SF purchasing is often assessed through intention, while articles on experienced consumers typically measure actual purchasing behavior, reflecting the ease of observing purchases among actively engaged consumers. This difference may confound the identified predictors for each group and skew the understanding of the true drivers behind SF purchasing, as certain predictors may be over- or underreported. To address this limitation, we propose future research that examines purchasing behavior across consumer groups using the same measures. For example, experimental research design would enable direct comparisons and allow for statistical testing of the effect of experience on SF purchasing.

A third limitation of this review is that it focused on statistically significant results. Predictors like environmental cognition are easier to measure on a large scale and thus more frequently studied and published, potentially leading to an overrepresentation of their influence in the counts. As a result, these predictors may appear more impactful, while others, like risk and trust, may be underrepresented due to less research. This could indicate publication bias stemming from the reliance on published articles (Berinsky et al., 2021). Consequently, the data presented in Figure 5 emphasize the prevalence of significance within the context of this review rather than the most essential predictors, reflecting research trends or methodological constraints instead of robust theoretical foundations. To address this limitation, we referred to predictors that “occur most as significant” rather than labeling them as the “most important.” Future research should explore a broader array of predictors simultaneously to foster a deeper understanding of the predictors genuinely driving consumer behavior in SF. Additionally, future studies could integrate insights from gray literature, such as industry reports on rental platforms, to capture up-to-date behavioral patterns of experienced consumers.

Finally, this review aimed to provide a broad view of the SF market; however, it became clear that different SF approaches (such as slow fashion, resale, and rental) exhibit distinct characteristics. For example, while new SF products are often priced higher, second-hand items typically offer lower-cost options, affecting the predictors for each purchasing decision. The resale market, in particular, is rapidly evolving, with online platforms propelling its growth and placing it in competition with ultra-fast fashion (Arrigo, 2021). To address this, we have highlighted specific SF approaches where predictors differ. Future research should focus on distinguishing strategies like resale and rental from other SF approaches, such as slow fashion, by exploring the unique consumer predictors in each. A targeted approach could help refine effective tactics for promoting SF consumption across diverse consumer segments.

7 Conclusion

In recent decades, SF consumption has garnered significant attention from researchers, leading to an increase in articles on SF consumer behavior. However, a notable research gap remains regarding the predictors influencing individuals who have not yet converted their intentions into actual purchases (i.e., general consumers) compared to those who have (i.e., experienced consumers). A total of 100 articles were investigated on predictors for purchasing SF and synthesized in eight themes of social psychological predictors that affect and hinder SF purchasing, comparing general and experienced consumers. The review revealed four pivotal insights that deepen our understanding of SF purchasing behavior. First, environmental cognition including environmental awareness, knowledge, and perceived consumer effectiveness, emerges as the most extensively researched predictors for both consumer groups. Second, compelling evidence indicates that subjective norms influence the choices of general consumers, suggesting that perceived social pressures play a crucial role in their decision-making. Third, for experienced consumers, habits are a vital factor, highlighting the importance of established behaviors in guiding their sustainable choices. Finally, experience can transform barriers into motivators. This review highlights the role of experience as a transformative factor in SF purchasing behavior, demonstrating that as consumers gain experience, their self-perception evolves and influences their purchasing decisions. Additionally, it emphasizes the potential of goal framing, suggesting that effective goal frames can encourage initial SF purchases among general consumers, who often lack these motivational frameworks. Practitioners can leverage these insights to develop tailored strategies for both first-time and experienced consumers, ultimately transforming fashion consumption patterns and supporting the fashion industry's contribution to SDG 12.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AT-W: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KB: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. TT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This open access publication was funded by HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht through its Open Access Fund, which supports researchers in making their work freely accessible.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1556835/full#supplementary-material

References

Abrar, M., Sibtain, M. M., and Shabbir, R. (2021). Understanding purchase intention towards eco-friendly clothing for generation Y & Z. Cogent Bus. Manag. 8. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2021.1997247

Adigüzel, F., and Donato, C. (2021). Proud to be sustainable: Upcycled versus recycled luxury products. J. Bus. Res. 130, 137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.033

Ahn, I., Kim, S. H., and Kim, M. (2020). The relative importance of values, social norms, and enjoyment-based motivation in explaining pro-environmental product purchasing behavior in apparel domain. Sustainability 12:6797. doi: 10.3390/su12176797

Albarracín, D., Fayaz-Farkhad, B., and Granados Samayoa, J. A. (2024). Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 3, 377–392. doi: 10.1038/s44159-024-00305-0

Alghanim, S., and Ndubisi, N. O. (2022). The paradox of sustainability and luxury consumption: the role of value perceptions and consumer income. Sustainability 14:14694. doi: 10.3390/su142214694

Amaral, J. H. G., and Spers, E. E. (2022). Brazilian consumer perceptions towards second-hand clothes regarding Covid-19. Clean. Responsible Consum. 5:100058. doi: 10.1016/j.clrc.2022.100058

Apaolaza, V., Policarpo, M. C., Hartmann, P., Paredes, M. R., and D'Souza, C. (2023). Sustainable clothing: why conspicuous consumption and greenwashing matter. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32, 3766–3782. doi: 10.1002/bse.3335

Arksey, H., and O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Armstrong, C. M. J., and Park, H. (2020). Online clothing resale: a practice theory approach to evaluate sustainable consumption gains. J. Sustain. Res. 2:e200017. doi: 10.20900/jsr20200017

Arrigo, E. (2021). Collaborative consumption in the fashion industry: a systematic literature review and conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 325:129261. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129261

Berinsky, A. J., Druckman, J. N., and Yamamoto, T. (2021). Publication biases in replication studies. Polit. Anal. 29, 370–384. doi: 10.1017/pan.2020.34

Bly, S., Gwozdz, W., and Reisch, L. A. (2015). Exit from the high street: an exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 39, 125–135. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12159

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=EV_Q06CUsXsCandpgis=1

Brydges, T. (2021). Closing the loop on take, make, waste: investigating circular economy practices in the Swedish fashion industry. J. Clean. Prod. 293:126245. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126245

Busalim, A., Fox, G., and Lynn, T. (2022). Consumer behavior in sustainable fashion: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 1–25. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12794

Cayaban, C. J. G., Prasetyo, Y. T., Persada, S. F., Borres, R. D., Gumasing, M. J. J., and Nadlifatin, R. (2023). The influence of social media and sustainability advocacy on the purchase intention of Filipino consumers in fast fashion. Sustainability 15:8502. doi: 10.3390/su15118502

Ceylan, Ö. (2019). Knowledge, attitudes and behavior of consumers towards sustainability and ecological fashion. Text. Leather Rev. 2, 154–161. doi: 10.31881/TLR.2019.14

Chen, L., Qie, K., Memon, H., and Yesuf, H. M. (2021). The empirical analysis of green innovation for fashion brands, perceived value and green purchase intention-mediating and moderating effects. Sustainability 13:4238. doi: 10.3390/su13084238

Chi, T., Adesanya, O., Liu, H., Anderson, R., and Zhao, Z. (2023). Renting than buying apparel: U.S. consumer collaborative consumption for sustainability. Sustainability 15, 4926–4942. doi: 10.3390/su15064926

Choi, T. R., and Ahn, J. (2023). Roles of brand benefits and relationship commitment in consumers' social media behavior around sustainable fashion. Behav. Sci. 13:386. doi: 10.3390/bs13050386

Corboş, R. A., Bunea, O. I., and Triculescu, S. M. (2023). Towards sustainable consumption: consumer behavior and market segmentation in the second-hand clothing industry. Amfiteatru Econ. 25, 1064–1080. doi: 10.24818/EA/2023/S17/1064

Coscieme, L., Akenji, L., Latva-Hakuni, E., Vladimirova, K., Niinimäki, K., Henninger, C., et al. (2022). Unfit, Unfair, Unfashionable: Resizing Fashion for a Fair Consumption Space. Hot or Cool Institute, Berlin.

Dabas, C. S., and Whang, C. (2022). A systematic review of drivers of sustainable fashion consumption: 25 years of research evolution. J. Global Fashion Market. 13, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/20932685.2021.2016063

Dangelico, R. M., Alvino, L., and Fraccascia, L. (2022). Investigating the antecedents of consumer behavioral intention for sustainable fashion products: evidence from a large survey of Italian consumers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 185:122010. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122010

Day, S., Godsell, J., Masi, D., and Zhang, W. (2020). Predicting consumer adoption of branded subscription services: a prospect theory perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 29, 1310–1330. doi: 10.1002/bse.2435

de Groot, J. H. B. (2021). Smells in sustainable environments: the scented silk road to spending. Front. Psychol. 12:718279. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.718279

Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Sadiq, M., Sakashita, M., and Kaur, P. (2021). Green apparel buying behaviour: a stimulus–organism–behaviour–consequence (SOBC) perspective on sustainability-oriented consumption in Japan. Bus. Strategy Environ. 30, 3589–3605. doi: 10.1002/bse.2821

Djafarova, E., and Foots, S. (2022). Exploring ethical consumption of generation Z: theory of planned behaviour. Young Consum. 23, 413–431. doi: 10.1108/YC-10-2021-1405

Ferraro, C., Sands, S., and Brace-Govan, J. (2016). The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 32, 262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.07.006

Gusenbauer, M., and Haddaway, N. R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 11, 181–217. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1378

Hasbullah, N. N., Sulaiman, Z., Mas'od, A., and Ahmad Sugiran, H. S. (2022). Drivers of sustainable apparel purchase intention: an empirical study of Malaysian Millennial consumers. Sustainability 14:8950. doi: 10.3390/su14041945

Helinski, C., and Schewe, G. (2022). The influence of consumer preferences and perceived benefits in the context of B2C fashion renting intentions of young women. Sustainability 14:9407. doi: 10.3390/su14159407

Henninger, C. E., Alevizou, P. J., and Oates, C. J. (2016). What is sustainable fashion? J. Fashion Market. Manag. 20, 400–416. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-07-2015-0052

Iran, S., and Schrader, U. (2017). Collaborative fashion consumption and its environmental effects. J. Fashion Market. Manag. 21, 468–482. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-09-2016-0086

Johnstone, L., and Lindh, C. (2022). Sustainably sustaining (online) fashion consumption: Using influencers to promote sustainable (un)planned behaviour in Europe's millennials. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 64:102775. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102775

Kleinhückelkotten, S., and Neitzke, H. P. (2019). Social acceptability of more sustainable alternatives in clothing consumption. Sustainability 11:6194. doi: 10.3390/su11226194

Klockner, C. A., and Verplanken, B. (2019). “Yesterday's Habits Preventing Change for Tomorrow? About the Influence of Automaticity on Environmental Behaviour,” in Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, 2nd Edn. Eds. L. Steg and Judith I.M. de Groot. (Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.), pp. 238–250. doi: 10.1002/9781119241072.ch24

La Rosa, A., and Johnson Jorgensen, J. (2021). Influences on consumer engagement with sustainability and the purchase intention of apparel products. Sustainability 13:10655. doi: 10.3390/su131910655

Lai (2021). What Is Fast Fashion? Earth.Org. Available online at: https://earth.org/what-is-fast-fashion/

Laitala, K., Klepp, I. G., Haugrønning, V., Throne-Holst, H., and Strandbakken, P. (2021). Increasing repair of household appliances, mobile phones and clothing: experiences from consumers and the repair industry. J. Clean. Prod. 282:125349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125349

Lang, C., Seo, S., and Liu, C. (2019). Motivations and obstacles for fashion renting: a cross-cultural comparison. J. Fashion Market. Manag. 23. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-05-2019-0106

Leclercq-Machado, L., Alvarez-Risco, A., Gómez-Prado, R., Cuya-Velásquez, B. B., Esquerre-Botton, S., Morales-Ríos, F., et al. (2022). Sustainable fashion and consumption patterns in Peru: an environmental-attitude-intention-behavior analysis. Sustainability 14:9965. doi: 10.3390/su14169965

Lee, E. J., Bae, J., and Kim, K. H. (2020a). The effect of sustainable certification reputation on consumer behavior in the fashion industry: focusing on the mechanism of congruence. J. Global Fashion Market. 11, 137–153. doi: 10.1080/20932685.2020.1726198

Lee, E. J., Choi, H., Han, J., Kim, D. H., Ko, E., and Kim, K. H. (2020b). How to “Nudge” your consumers toward sustainable fashion consumption: an fMRI investigation. J. Bus. Res. 117, 642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.050

Legros, S., and Cislaghi, B. (2020). Mapping the social-norms literature: an overview of reviews. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 62–80. doi: 10.1177/1745691619866455

Lichy, J., Ryding, D., Rudawska, E., and Vignali, G. (2023). Resale as sustainable social innovation: understanding shifts in consumer decision-making and shopping orientations for high-end secondhand clothing. Soc. Enterp. J. 1750–8614. doi: 10.1108/SEJ-01-2023-0016

Lin, C. A., Wang, X., and Yang, Y. (2023). Sustainable apparel consumption: personal norms, csr expectations, and hedonic vs. utilitarian shopping value. Sustainability 15:9116. doi: 10.3390/su15119116

Lin, P. H., and Chen, W. H. (2022). Factors that influence consumers' sustainable apparel purchase intention: the moderating effect of generational cohorts. Sustainability 14:8950. doi: 10.3390/su14148950

Lindenberg, S., and Steg, L. (2007). Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. J. Soc. Iss. 63, 117–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00499.x

Lionço, A., Ribeiro, I., Johann, J. A., Bertolini, F., and Rogis, G. (2019). Young Brazilians' purchase intention towards jeans made of Tencel® fibers. Revista Brasileira de Market. 18, 148–177. doi: 10.5585/remark.v18i3.16370

Liu, C., Bernardoni, J. M., and Wang, Z. (2023). Examining generation z consumer online fashion resale participation and continuance intention through the lens of consumer perceived value. Sustainability 15:8213. doi: 10.3390/su15108213

Lloyd, S., and Gifford, R. (2024). Qualitative research and the future of environmental psychology. J. Environ. Psychol. 97:102347. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102347

Lou, X., Chi, T., Janke, J., and Desch, G. (2022). How do perceived value and risk affect purchase intention toward second-hand luxury goods? An empirical study of U.S. consumers. Sustainability 14:11730. doi: 10.3390/su141811730

Lundblad, L., and Davies, I. (2016). The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 15, 149–162. doi: 10.1002/cb.1559

Machado, M. A. D., Almeida, S. O., de, Bollick, L. C., and Bragagnolo, G. (2019). Second-hand fashion market: consumer role in circular economy. J. Fashion Market. Manag. 23, 382–395. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-07-2018-0099

McKeown, C., and Shearer, L. (2019). Taking sustainable fashion mainstream: Social media and the institutional celebrity entrepreneur. J. Consum. Behav. 18, 406–414. .1780 doi: 10.1002/cb.1780

Moher D. Liberati A. Tetzlaff J. Altman D. G. for the PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535–b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

Mukendi, A., Davies, I., Glozer, S., and McDonagh, P. (2019). Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. Eur. J. Market. doi: 10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0132

Nielsen, K. S., Brick, C., Hofmann, W., Joanes, T., Lange, F., and Gwozdz, W. (2023). The motivation – impact gap in pro-environmental clothing consumption. Nat. Sustain. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/4qtep

Niinimäki, K. (2010). Eco-Clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustain. Dev. doi: 10.1002/sd.455

Pandey, S., Pandit, P., Pandey, R., and Pandey, S. (2020). Marketing strategies for upcycling and recycling of textile and fashion. Recycl. Waste Fashion Text. 253–275. doi: 10.1002/9781119620532.ch12

Pang, C., Zhou, J., and Ji, X. (2022). The effects of chinese consumers' brand green stereotypes on purchasing intention toward upcycled clothing. Sustainability 14:16826. doi: 10.3390/su142416826

Pantano, E., and Stylos, N. (2020). The Cinderella moment: exploring consumers' motivations to engage with renting as collaborative luxury consumption mode. Psychol. Market. 37, 740–753. doi: 10.1002/mar.21345

Park, J., Eom, H. J., and Spence, C. (2022). The effect of perceived scarcity on strengthening the attitude–behavior relation for sustainable luxury products. J. Product Brand Manag. 31, 469–483. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-09-2020-3091

Pradeep, S., and Pradeep, M. (2023). Awareness of sustainability, climate emergency, and generation Z's consumer behaviour in UAE. Clean. Respons. Consum.11:100137. doi: 10.1016/j.clrc.2023.100137

Reimers, V., Magnuson, B., and Chao, F. (2016). The academic conceptualisation of ethical clothing: could it account for the attitude behaviour gap? J. Fashion Market. Manag. 20, 383–399. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-12-2015-0097

Riesgo, S. B., Lavanga, M., and Codina, M. (2023). Drivers and barriers for sustainable fashion consumption in Spain: a comparison between sustainable and non-sustainable consumers. Int. J. Fashion Design Techn. Educ. 16, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/17543266.2022.2089239

Rodrigues, M., Proença, J. F., and Macedo, R. (2023). Determinants of the purchase of secondhand products: an approach by the theory of planned behaviour. Sustainability 15:10912. doi: 10.3390/su151410912

Ruan, Y., Xu, Y., and Lee, H. (2022). Consumer motivations for luxury fashion rental: a second-order factor analysis approach. Sustainability 14:7425. doi: 10.3390/su14127475

Rutelione, A., and Bhutto, M. Y. (2024). Exploring the psychological benefits of green apparel and its influence on attitude, intention and behavior among Generation Z: a serial multiple mediation study applying the stimulus–organism–response model. J. Fashion Market. Manag. 28. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-06-2023-0161

Seo, S., Watchravesringkan, K., Swamy, U., and Lang, C. (2023). Investigating expectancy values in online apparel rental during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: moderating effects of fashion leadership. Sustainability 15:12892. doi: 10.3390/su151712892

Shrivastava, A., Jain, G., Kamble, S. S., and Belhadi, A. (2021). Sustainability through online renting clothing: circular fashion fueled by instagram micro-celebrities. J. Clean. Prod. 278:123772. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123772

Silva, S. C., Santos, A., Duarte, P., and Vlačić, B. (2021). The role of social embarrassment, sustainability, familiarity and perception of hygiene in second-hand clothing purchase experience. Int. J. Retail. Distr Manag. 49, 717–734. doi: 10.1108/IJRDM-09-2020-0356

Slaton, K., and Pookulangara, S. (2022). The secondary luxury consumer: an investigation into online consumption. Sustainability 14:13744. doi: 10.3390/su142113744

Sommer, L. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour and the impact of past behaviour. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 10, 91–110. doi: 10.19030/iber.v10i1.930

Stolz, K. (2022). Why Do(n't) we buy second-hand luxury products? Sustainability 14:8656. doi: 10.3390/su14148656

Styvén, M. E., and Mariani, M. M. (2020). Understanding the intention to buy secondhand clothing on sharing economy platforms: the influence of sustainability, distance from the consumption system, and economic motivations. Psychol. Market. 37, 724–739. doi: 10.1002/mar.21334

Tandon, A., Sithipolvanichgul, J., Asmi, F., Anwar, M. A., and Dhir, A. (2023). Drivers of green apparel consumption: Digging a little deeper into green apparel buying intentions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32, 3997–4012. doi: 10.1002/bse.3350

Turunen, L. L. M., Cervellon, M. C., and Carey, L. D. (2020). Selling second-hand luxury: empowerment and enactment of social roles. J. Bus. Res. 116, 474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.059

Van Der Weiden, A., Benjamins, J., Gillebaart, M., Ybema, J. F., and De Ridder, D. (2020). How to form good habits? a longitudinal field study on the role of self-control in habit formation. Front. Psychol. 11:560. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00560

Vehmas, K., Raudaskoski, A., Heikkilä, P., Harlin, A., and Mensonen, A. (2018). Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. J. Fashion Market. Manage. 22, 286–300. doi: 10.1108/JFMM-08-2017-0079

Vladimirova, K., Henninger, C. E., Alosaimi, S. I., Brydges, T., Choopani, H., Hanlon, M., et al. (2024). Exploring the influence of social media on sustainable fashion consumption: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Global Fashion Market. 15, 181–202. doi: 10.1080/20932685.2023.2237978

Waight, E. (2019). Mother, consumer, trader: gendering the commodification of second-hand economies since the recession. J. Consum. Cult. 19, 532–550. doi: 10.1177/1469540519872069

Wang, P., Kuah, A. T. H., Lu, Q., Wong, C., Thirumaran, K., Adegbite, E., and Kendall, W. (2021). The impact of value perceptions on purchase intention of sustainable luxury brands in China and the UK. J. Brand Manag. 28, 325–346. doi: 10.1057/s41262-020-00228-0

Xu, J., Zhou, Y., Jiang, L., and Shen, L. (2022). Exploring sustainable fashion consumption behavior in the post-pandemic era: changes in the antecedents of second-hand clothing-sharing in China. Sustainability 14:9566. doi: 10.3390/su14159566

Yang, H., Su, X., and Shion, K. (2023). Sustainable luxury purchase behavior in the post-pandemic era: a grounded theory study in China. Front. Psychol. 14:1260537. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1260537

Yoo, F., Jung, H. J., and Oh, K. W. (2021). Motivators and barriers for buying intention of upcycled fashion products in china. Sustainability 13:2584. doi: 10.3390/su13052584

Zahid, N. M., Khan, J., and Tao, M. (2021). Exploring mindful consumption, ego involvement, and social norms influencing second-hand clothing purchase. Curr. Psychol. 42, 13960–13974. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02657-9

Keywords: consumer behavior change, sustainable fashion consumption, intention-behavior gap, prior experience, systematic literature review

Citation: Toebast-Wensink A, van den Broek KL, Timmerman T and Hekkert MP (2025) Experience matters: a systematic review and research agenda on predictors to buy sustainable fashion. Front. Sustain. 6:1556835. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1556835

Received: 10 January 2025; Accepted: 19 May 2025;

Published: 06 June 2025.

Edited by:

Elisabeth Süßbauer, Technical University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Eri Amasawa, The University of Tokyo, JapanTahira Javed, China Three Gorges University, China

Copyright © 2025 Toebast-Wensink, van den Broek, Timmerman and Hekkert. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Annuska Toebast-Wensink, YW5udXNrYS50b2ViYXN0QGh1Lm5s

Annuska Toebast-Wensink

Annuska Toebast-Wensink Karlijn L. van den Broek

Karlijn L. van den Broek Tijs Timmerman

Tijs Timmerman Marko P. Hekkert2

Marko P. Hekkert2