- 1Geography, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

- 2University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

- 3Independent Scholar, Portugal Cove, NL, Canada

- 4Independent Scholar, Helena, MT, United States

- 5Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Understanding social-ecological connection is paramount to adoption and long-term viability of nature-based solutions (NbS). Here, we describe a three-year trial of community-engaged participatory research (CBPR) through an artist commission program run by Engage with Nature-based Solutions (http://www.engagewithnbs.ca). The program has thus far commissioned twelve Canadian artists to contribute their artistic research to facilitate conversations about climate change and conceptualizations of NbS. The artists we commissioned created a piece of art for their local community on NbS and climate, facilitated a community-engaged workshop to share their research creation, and supported the development of an online toolkit meant to help other communities engage with NbS and climate change. We suggest that this commission program is a cost-effective way to: (i) reach a diversity of communities typically outside the reach of academia, (ii) enlarge audiences who are engaged with NbS, (iii) provide alternative formats and mediums for engagement and education on NbS, (iv) give credence to artistic work as climate work, and (v) provide opportunities for collaboration between the arts/sciences and community/academia.

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a collaborative approach to knowledge production that places emphasis on the active involvement of community (individuals, community groups, etc.) in addressing shared concerns (Dowling et al., 2018). At its root, CBPR strives for research that, rather than being done on a community or group, works for the community and with the community (van Blerk et al., 2023). CBPR has also, however, been the subject of increased debate as researchers look more closely at research design, questions of power and collaboration, community and academic researcher priorities, and question not just how but whether voices from the community are adequately and accurately represented (Holt et al., 2019; Wilson, 2013). Best practices include working with experts who “have an abundance of local knowledge, community ties, or the ability to inspire participation and engagement from their fellow community members” (Hardy et al., 2015).

We, like many working in the geohumanities and creative geographies, see artists and art as able to achieve best practices in CBPR (Badham et al., 2018; Cresswell, 2014; Eshun and Madge, 2012; Magrane, 2016; McLean and Leeuw, 2020). Artists are experts in their local communities and can distill and give voice to community concerns (Christensen, 2012); art can connect and create opportunities for dialogue (Grile, 2013); artists can vision and provide novel perspectives and understandings of current social challenges (Peters and Barnett, 2024). Artists are particularly key participants when addressing climate change and ecosystem degradation; as artists cultivate attention and care to complex topics, and can mitigate the “extinction of experience” in today's digital-mediated, disconnected world (Baldwin, 2018; Jacobson et al., 2016). Art can also foreground the interdependence of humans and all Earth's species and clarify the importance of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) in environmental, community-engaged work. NbS, which leverage natural systems to tackle societal and environmental challenges such as climate change, offer promising focus areas for community-engaged research. By integrating artistic practices into NbS, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) can transition to STEAM, adding the Arts as a pivotal element for creative and emotional resonance.

Overview and methods

As Hawkins argues that geography's latest “turn” pivots around creativity (Hawkins, 2019), and CBPR has seen increased interest in using creative methods to achieve impacts (Blackstone et al., 2008; Hunter et al., 2002), we have thus designed a program to add to this work and to fill a gap in creative interventions in the sciences and social sciences. Engage with Nature-Based Solutions (ENBS) (engagewithnbs.ca) is a pilot initiative that operates as a collaboration between the University of Victoria and community organizations, artists, and scientists across the country. The NbS initiative works with communities, artists and scientists, to (a) collect and collate resources, (b) produce educational modules, (c) facilitate engagement and storytelling, and (d) provide technical assistance. The initiative strives to add to work illustrating the impact and benefits of NbS in a climate-unsteady world (Cabling et al., 2024; Keesstra et al., 2018).

One aspect of this initiative includes a three-year trial of a community-engaged artist commission program. To date, ENBS has commissioned 12 artists from Canada between 2022 and 2025, with six participating artists in the 2022–2023 cycle, four in 2023–2024, and two in 2025. This cohort includes seven women and five men, including two Indigenous artists. Two of the artists (Creates and McKay) are recipients of Governor General's Awards (Canada's national arts award); several others are recipients of or have been nominated for other arts awards. Commissioned artists work in a variety of disciplines, including writing, sculpture, photography, environmental art, performance art, and graphic design. Artists were selected based on their body of work and their history of engaging in cross-disciplinary projects with focus on subjects such as climate, water, biodiversity, or the anthropocene. Each artist receives a commission fee, and retains ownership of work to ensure artistic independence; ENBS focuses on community-engaged dialogue and learning opportunities through supporting art-making and dissemination. ENBS has allocated $65K to artists since 2022.

The program has three parts. First, we ask artists to create a piece of art that aligns with the themes of engagement, learning and action related to NbS and climate change. Second, they engage their communities through a workshop or talk that situates their art and supports interdisciplinary discussions on climate change and NbS. Finally, artists develop a tool—such as a workshop template or instructional materials—to be included in ENBS' online toolkit. Resources are designed for educators and facilitators aiming to use creative methods in public engagement. The format or medium of both the art and the tool is up to the artist. Artistic outputs thus far include sculpture, writing, visual media, sound recording, GIS data visualization, community feast, and carving. Accompanying tools include writing exercises, instruction booklets, and detailed workshop guides. The commission program presents a cost-effective way of reaching diverse communities; enlarging audiences who think about and are engaged with NbS; capturing interest about these topics, of providing alternative formats and mediums (STEAM) for engagement and education; valuing artistic work as climate work, and; providing opportunity for cross-pollination and collaboration between the arts and sciences, as well as between community and academia. The ENBS toolkit as a whole includes the commission program's tools; watershed-focused educational curriculum for Grades 4–12 students; a selected resource library on topics related to NbS; and a series of ArcGIS StoryMaps and videos which serve as science storytelling and detail restoration and NbS projects across Canada (see engagewithnbs.ca).

Situating the field

Thus far, most creative production within the academy falls into three categories. One is artist production as cultural production (professional artists who work independently on projects of their own devising, to satisfy their own aims). This art may (and often does) address critical social-cultural or environmental issues, but the artist's aim is not just persuasion, but rather could equally be to inspire, to imagine, to persuade, or simply to point and praise (McKay, 2000; Zapruder, 2010). Second is art as a community-engaged method, where art is used as a tool to facilitate communication, to empower, or to represent community memory (Ballard and Saunders, 2022; Blackstone et al., 2008; Brinklow et al., 2021; Curtis et al., 2012; Duxbury et al., 2018; McLean and Leeuw, 2020; Olstad, 2018). Art produced in these cases is often completed by community or in tandem with researchers, in the service of a community-engaged research project. The practitioners/researchers may or may not be professional artists themselves, and the art produced is not expected to be of professional quality (Grile, 2013). Instead, it satisfies a research need and provides an avenue to reach broader audiences (Lancione, 2017), an opening to emotion and emotion-focused concerns (Hawkins and Kanngieser, 2017), or a method of enlivening research, a “device to engage both specialists and the general public” with geographical work (Hawkins, 2019). Third, art can be a form of research (Acker, 2020, 2022; Hawkins, 2011, 2015; Kinkaid, 2019; Peters and Barnett, 2024). Creative methods, such as poetry, drawing, photography, environmental art and more are being used within the Geohumanities and NbS to do geographical research (Alméstar et al., 2023; Lydon, 2020). Both practicing professional artists whose preoccupation centers around the environment (and who find themselves being courted by geographers) and scientists/social scientists who employ or practice art fall into this category (Creates, 2001; Robinsong, 2022). Art here functions as a way of understanding place, a response to climate change and other environmental crises, and a rethinking of human and more-than-human relationships (Magrane, 2017, 2021).

All three of these kinds of art production within the academy have their own critical frameworks, but the latter two have been of particular interest to community-based practitioners (and more recently, to NbS advocates) because of their potential to help engage, inform, or collaborate with communities (Alméstar et al., 2023; Hawkins, 2019). Hawkins (2019), however, also cautions researchers that art use within the social sciences not become “just another example of disciplinary colonialism or a fad driven by less than intellectual or creative ambitions”. We see an opportunity to diversify the inclusion of art within the social sciences, and our work aims to add to emerging work in the areas of arts-based participatory research (Mand, 2012; Vaart et al., 2018). Firstly, our work seeks to validate and respect the work of practicing artists by inviting them to add their expertise to social sciences CBPR, rather than minimizing or discounting the rigor and professionalization of artists' practice through having amateur artists use art as research or teach art-making. Secondly, by adding a community-engaged component to the work that artists do, we strive to amplify the work that art and artists do in communities, broadening their reach beyond their own artistic circles, and allowing ENBS to broaden its reach beyond traditional social science and science circles. Finally, we offer that art addresses and mitigates the complex power relationships in CPBR through its appeal to emotion, its focus on attachment to place, and its ability to transcend cultural boundaries to gesture toward the challenges of being human on an ailing planet. We add, through this program, to work inviting artists to participate in action-based research, funding visiting artists in science project and communities, and enabling artists to contribute to social and environmental challenges as respondents, collaborators, and researchers (Van Den Bergh, 2015; https://arts.cern/; https://science-art-society.ec.europa.eu/front).

Results and discussion

A unique feature of the ENBS program is its focus on collaboration with professional artists, and the production of tools by these artists for use by communities, which allows for amplification of impact and replicability of artists' processes. Participatory engagement is a consistent feature, with artists acting as bridge to community groups, allowing ENBS to amplify its reach. Direct beneficiaries of the project include over 1,500 attendees of artist shows and workshops; indirect beneficiaries stand to be significantly higher, as workshop tools are downloaded and reused in additional communities. Final numbers have yet to be determined; the project has not yet reached its conclusion. The workshops facilitated by these artists often became opportunities for interdisciplinary dialogue, bringing together scientists, educators, and local residents to discuss topics explored within NbS, such as creek restoration, stormwater management, and ecosystem resilience. Following, we detail four examples of commissions completed thus far, showing reach and impact for each, and arguing how each contributes to learning and engagement on NbS and climate, along with concurrent benefits of increased attachment to place, understanding of local ecosystems, and, in some cases, translation of experience into artistic output by community members.

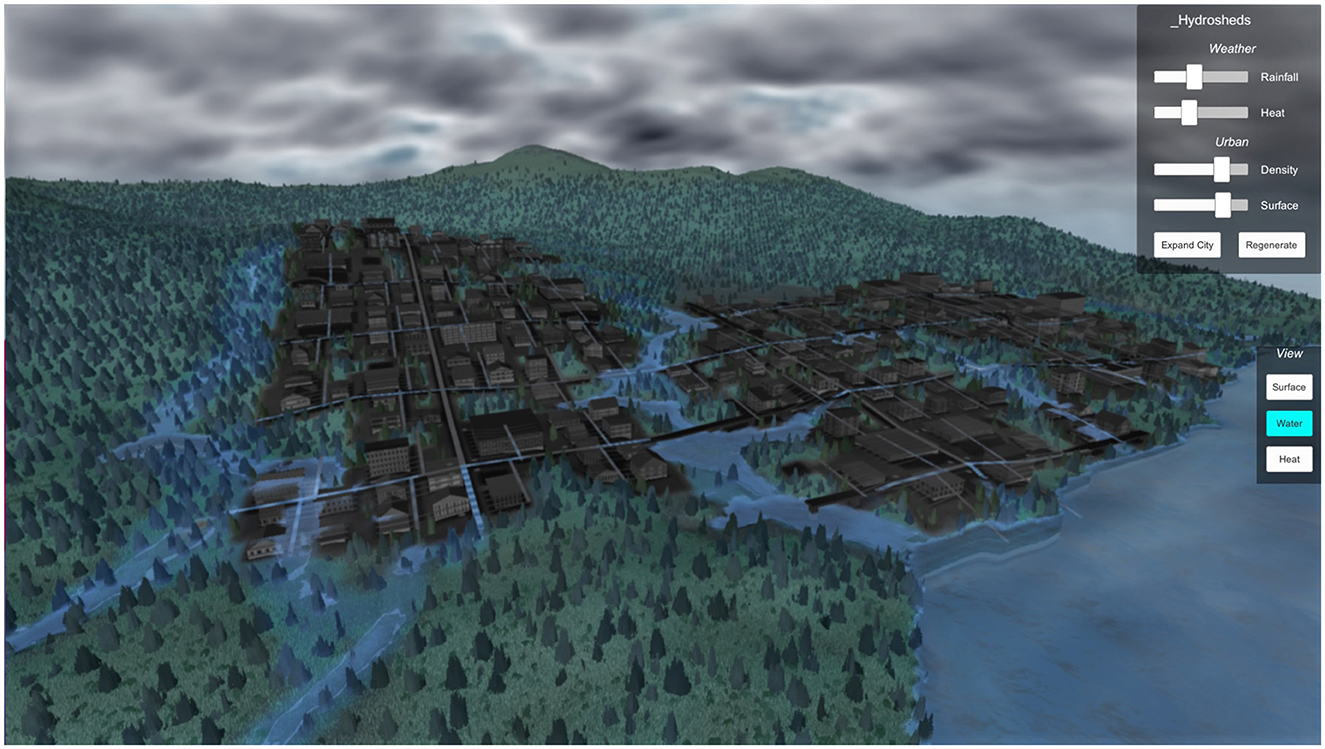

In example 1, digital artist Colton Hash created Hydrosheds, an interactive simulation that depicts landscape relationships between an urban community and its adjacent ecosystems. Hydrosheds models the effects of precipitation, temperature, and impervious surfaces in a watershed, allowing residents to modify surface conditions of an urban landscape to view the impacts of infrastructure on watershed dynamics (see Figure 1). The digital artwork was informed by urbanized watersheds around Victoria, British Columbia (BC). Hash held an artist talk and demonstration at a creekside art gallery, and then took residents on a walk along the creek to discuss NbS interventions such as watershed restoration and to share stories about the creek. Attendees included members of several NGO watershed groups, artists, scientists and community members. Conversation, as Hash noted, was wide-ranging and had a freedom and complexity that more formalized municipal meetings often lack. The event also focused attention on the pressing issues of climate and water that art openings–in his experience–do not always foreground. Hash's piece has since been exhibited in two additional gallery shows at the University of Victoria's McPherson Library and Hamilton, Ontario's Factory Media Center, with a combined reach of ~5,000 people. He has since received numerous requests from community groups and consulting organizations who are interested in creative visualization of local water systems; Hash has made Hydrosheds available by download for community outreach.

Figure 1. Still capture from Hydrosheds by Colton Hash. Viewers adjust rainfall, heat, density and imperviousness levels to see the impacts of urban development and climate change on an ecosystem.

Artist Emrys Miller, our second example, created a photography and drawing repository that includes visual storytelling techniques designed to engage communities in urban watershed understanding and stewardship—a critical element of NbS in building long-term water resilience for communities, economies and for the environment (Lydon et al., 2023). Miller's photos and sketches, which document urban stream health and challenges to aquatic health, are available for download and use by individuals and non-profit organizations; his work is also featured in ENBS's Urban Watershed curriculum, designed for Grades 6–12 students, which includes instructions on how to engage students with the natural world using art (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Urban stream sketch, part of an Intermediate BC Science 12 curriculum module, by Emrys Miller. The sketches focus on Bowker Creek, an urban salmon-bearing stream in Victoria, BC that has suffered under urbanization and is currently being restored by local grassroots environmental organizations.

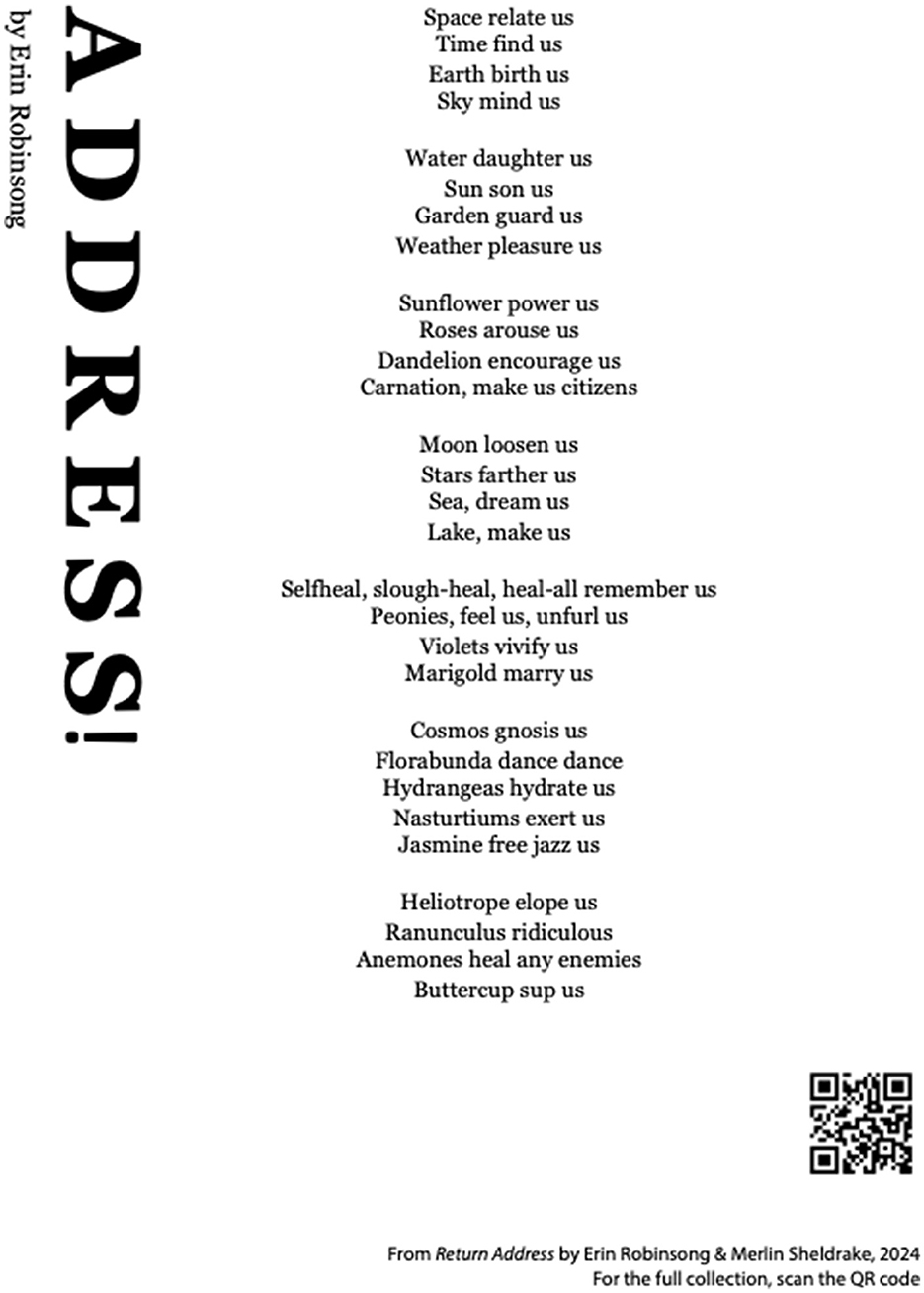

A third example features artist Erin Robinsong (Montreal) and biologist Merlin Sheldrake (United Kingdom), who produced a non-fiction/poetry chapbook (see Figure 3) and workshop focused on the concept of direct address (addressing nonhuman members of the living world in second person rather than speaking about them). They argue:

It's easy to forget that interspecies communication is a non-negotiable part of living and that our human-to-human interactions are just a tiny fraction of the vast currents of meaningful communication taking place at any one moment…Art—as a field of experiment, play, and possibility—is an ideal place to ask qualitative questions about the possibilities of inter-species communication and relation that may be difficult or taboo in the modern sciences (Robinsong and Sheldrake, 2023).

Figure 3. Broadsheet “Address” by Erin Robinsong and Merlin Sheldrake. The broadsheet is from a chapbook of poems written and published by Robinsong as a series of direct address exercises.

Sheldrake and Robinsong offered two direct address writing workshops for Cortes Island residents: one for the community at large, and one for students of Cortes Island Academy, the local high school program, where participants created their own direct-address poems to nonhuman community members they encountered during the workshop, including trees, moss, ravens, and many others. The workshop instructions are now available for download for those wishing to “respond to intersecting climate and biodiversity crises” through direct address of the more-than-human world (Acker, n.d).

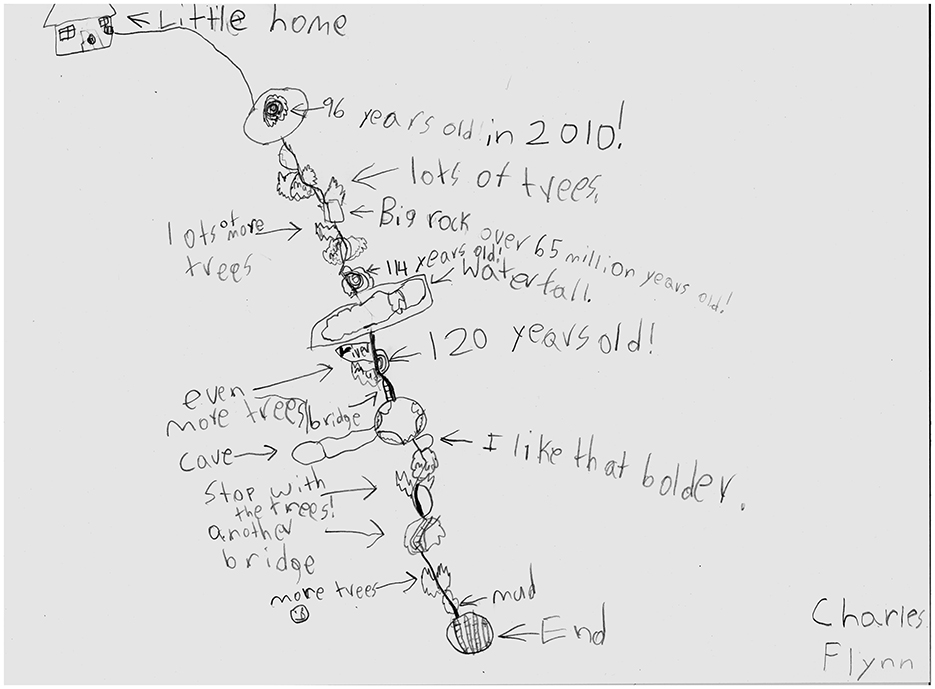

Finally, as our fourth example, Governor General's Award-winning artists Marlene Creates (environmental artist) and Don McKay (poet) gave a series of memory map drawing workshops in Creates' boreal-forested property in Portugal Cove, Newfoundland, to over 100 Grade 4 students from the local elementary school. This collaborative community project engaged school children with the local ecosystem, as Creates and McKay, along with six additional visiting artists, led guided walks in her six-acre old growth forest, and then facilitated a workshop where each student drew their own memory map to document their experience (see Figure 4). The participants' maps were then exhibited in a local cafe, including a slide show that documented their guided walks. The memory maps illustrate some of what registered in the children's memories from the terrain, and what they saw and heard during their multi-sensorial experience in the boreal forest. One participant teacher commented, “these artists helped us understand our community, the land and the animals that inhabit it.” Another said, “The event was engaging and very informative. It allowed the children to utilize their five senses and stop to think about their surroundings.” And another commented that Creates and McKay's work “allow[s] the children to be fully immersed in nature and art, completely unaware of where one ends and the other begins” (Creates, pers. comm.). One student, describing the process of drawing her memory map, said “My pencil is me. I'm walking the path. I hike my way through my imagination”.

Figure 4. Memory map by student participant Charles Flynn. Memory maps were drawn by students after a guided walking tour through a Newfoundland boreal forest with Marlene Creates and Don McKay.

Together, these productions, community gatherings and resulting toolkit elements empower other communities to replicate these engagement models for connecting art to NbS and environmental challenges, further extending the program's impact. Artistic engagement through the ENBS program has proven transformative, not only in terms of production of new work and public reach but also in its ability to foster meaningful community connections. These connections continue to spark new collaborations. Commissioned artists continue to show and disseminate their work. Creates and McKay's project will feature in a forthcoming book with Memorial University Press. ENBS also partners with the University of Victoria's Geography 380: Community Mapping class (taught by this article's first author), where cohorts of students work with local community organizations to further CBPR projects. In Fall 2024, a cohort of four students worked with MÍYEŦEN Nature Sanctuary, in Songhees Territories on Vancouver Island, BC, on the Kinship Mapping project. Students inspired by the ENBS artist-commission program worked to illustrate the potential of art to honor Indigenous Ecological Knowledge (IEK) while recognizing traditional food and medicinal systems. The students co-created a layered IEK map informed by the 13 Moon WSANÉC calendar.1 Beyond its immediate outcomes of increased engagement with local First Nations and positive impacts on the students themselves, the project also represents a step in a broader decolonial effort, demonstrating the potential of art to catalyze systemic change.

Commissioned projects for 2025 include writer Annabel Howard and performance artist Connie Morey. Howard, a Montreal-based artist and PhD candidate, will create a series of writings and run a workshop that aims to foster ecological imagination in urban environments. The workshop will use written and spoken word to facilitate artists, scientists, and community members to think together about the Commons and to forge space (physical and psychological) for ritual and reverie against the backdrop of construction noise, car fumes, and population density. Through construction of an ArcGIS StoryMap, she is also bringing attention to invasive species on the St. Lawrence River and restoration efforts underway on its banks and islands. Environmental artist Connie Morey's project asks the question, “Could individual and collective acts of listening help to heal communities and ecosystems?” Her project invites artists and members of the public to participate in a community art project that “uses listening and mending as acts of ecological solidarity and collective healing” (personal communication, Morey, n.d.).

Studies on community-engaged participatory research emphasize the role of arts-based methods in enhancing public understanding of complex issues. Curtis et al. (2012) highlight how visual and performing arts can amplify marginalized voices and foster collective action. Similarly, Evans et al. (2022) explore how art interventions create inclusive spaces for dialogue, particularly in addressing environmental challenges. Using the described commissions as examples, we argue that art can amplify and set the stage for open communication and generative discussions that crosses disciplinary boundaries and works to inform and educate across these boundaries. In Hash's workshop, for instance, participants learned about NbS restoration along the creek, but could also discuss their hopes and fears for the creek related to climate change, political shortfalls in stormwater management, and place-based stories about the watershed. Discussion included recent flooding during atmospheric river events, memories of species found in the creek in the past, and place-based connections to the creek's ecosystems. Events such as those from Hash's, Creates and McKay's, and Sheldrake and Robinsong's projects highlight the multidimensional emotional and cultural benefits of NbS, aspects often overlooked in scientific discourse. The art and associated workshops connect science (NbS) to emotion (care for the creek), and underscore research attesting to the importance of art as a connecting tool and as a valid response to current environmental challenges (de Leeuw et al., 2017; Mackay et al., 2021; McKittrick, 2021; Moore and Haverluck, 2022; Sparrow, 2006). These insights align with the outcomes of the ENBS program, where artistic practices acted as catalysts for social and ecological awareness.

The program's impact is also reflected in metrics such as social media engagement and survey feedback. The ENBS website has received 10.7K views since its launch in September 2022, with 5K unique visitors. Over 1K of these visited the artist commission pages. Facebook posts highlighting the intersection of art and NbS, as well as each artist-led workshop, garnered the highest levels of audience interaction. Informal post-workshop surveys indicate that the experience is impactful for artists and participants, fostering a deeper connection to the themes of NbS and climate action. Despite the program's modest budget, its reach and influence underscore the cost-effectiveness of integrating art into NbS initiatives. We also recognize that further impact measurement will be needed at the program's conclusion, and acknowledge the European Commission's S+T+Arts program and its work to clarify the dimensions of impact and assessment when doing work that bridges the arts and sciences (Diakou and De Rosa, 2024). Our impact measurement will include post-participation surveys for all artists, participation surveys for 2025 workshop participants, project partner interviews, website visitor analysis, and keyword analysis.

Conclusion

The ENBS artist commission program is a powerful tool for engaging communities on the topics of NbS and climate change. By humanizing the abstraction of facts and figures, art provides a resonant, emotional connection to the local impacts of climate change. It also enables meaningful dialogue across disciplines, bringing together scientists, artists, and community members to co-create solutions. Metrics such as event participation, online engagement, and artist feedback indicate the program's success. Artists themselves have informally reported significant professional and personal growth, while their communities benefited from new perspectives and tools for addressing environmental and climate challenges through different NbS interventions. The program's ability to foster continued interdisciplinary collaborations further underscores the value of integrating art into CBPR, NbS, and climate work.

Looking ahead, the ENBS model offers a compelling blueprint for future initiatives. By embracing the arts as a vital component of NbS and climate action, and by bringing professional artists as collaborators into CBPR, we can enrich public engagement, empower communities, and drive meaningful change. The lessons learned from this program highlight the need for more investment in art-based approaches, which support both the creative and scientific communities in addressing the challenges of our time. To further enhance the impact of such programs, future initiatives could incorporate longitudinal studies to measure long-term community engagement and environmental outcomes. Additionally, partnerships with community organizations both locally and globally could extend the reach of these models, fostering networks of artists, scientists, and communities dedicated to addressing climate change through innovative, creative approaches.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: engagewithnbs.ca.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CT: Writing – review & editing. GB: Writing – review & editing. MC: Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – review & editing. ER: Writing – review & editing. AH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada | Environnnement et Changement climatique Canada.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The 13 moon WSANÉC calendar is part of WSANÉC natural law, and guides cultural and economic activities for the WSANÉC peoples on Southern Vancouver Island.

References

Acker, M. (2020). “Lyric geography,” in Geopoetics in Practice, eds. E. Magrane, L. Russo, S. de Leeuw, and C. S. Perez (London: Routledge), 131–162. doi: 10.4324/9780429032202-12

Acker, M. (n.d.). Engage with Nature-Based Solutions: Erin Robinsong & Merlin Sheldrake: Return Address. Available online at: https://engagewithnbs.ca (accessed April 24, 2025).

Alméstar, M., Romero-Muñoz, S., Mestre, N., Fogué, U., Gil, E., and Masha, A. (2023). (Un)Likely connections between (un)likely actors in the Art/NBS co-creation process: application of KREBS cycle of creativity to the cyborg garden project. Land 12:6. doi: 10.3390/land12061145

Badham, M., Garrett-Petts, W. F., Jackson, S., Langlois, J., and Malhotra, S. (2018). “Creative cartographies: a roundtable discussion on artistic approaches to cultural mapping,” in Artistic Approaches to Cultural Mapping (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315110028-17

Baldwin, L. K. (2018). Drawing care: the illustrated journal's “path to place”. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 18, 75–93. doi: 10.1080/15313220.2017.1404723

Ballard, S., and Saunders, J. (2022). Art writing and coastal change: story-telling in the blue economy. GeoHumanities 8, 462–481. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2022.2094280

Blackstone, M., Given, L., Lévy, J., McGinn, M., O'Neill, P., Palys, T., et al. (2008). “Research Involving Creative Practices: A Chapter for Inclusion in the TCPS,” in The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Ethics Special Working Committee (SSHWC): A Working Committee of The Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics (PRE).

Brinklow, L., Marshall, R., and Whiteway, B. (2021). “Exploring climate change through the language of art,” in Handbook of the Changing World Language Map, eds. S. D. Brunn and R. Kehrein (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73400-2_230-1

Cabling, L. P. B., Dubrawski, K. L., Acker, M., and Brill, G. (2024). Harnessing community science to support implementation and success of nature-based solutions. Sustainability. 16:23. doi: 10.3390/su162310415

Christensen, J. (2012). Telling stories: exploring research storytelling as a meaningful approach to knowledge mobilization with Indigenous research collaborators and diverse audiences in community-based participatory research. Can. Geographer 56, 231–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00417.x

Creates, M. (2001). The distance between two points is measured in memories: Labrador 1988 - ProQuest. Queen's Quart. 108, 539–548.

Cresswell, T. (2014). Geographies of poetry/poetries of geography. Cult. Geograph. 21, 141–146. doi: 10.1177/1474474012466117

Curtis, D. J., Reid, N., and Ballard, G. (2012). Communicating ecology through art: what scientists think. Ecol. Soc. 17:3. doi: 10.5751/ES-04670-170203

de Leeuw, S., Parkes, M. W., Morgan, V. S., Christensen, J., Lindsay, N., Mitchell-Foster, K., et al. (2017). Going unscripted: a call to critically engage storytelling methods and methodologies in geography and the medical-health sciences: going unscripted. Can. Geographer 61, 152–164. doi: 10.1111/cag.12337

Diakou, S., and De Rosa, S. (2024). Assessing the impact of the S+T+ARTS framework. Main evidence and reflections to inform the community and policymakers for supporting artistic research. Eur. J. Cult. Managem. Policy 14:13063. doi: 10.3389/ejcmp.2024.13063

Dowling, R., Lloyd, K., and Suchet-Pearson, S. (2018). Qualitative methods III: Experimenting, picturing, sensing. Prog. Human Geog. 42, 779–788. doi: 10.1177/0309132517730941

Duxbury, N., Garrett-Petts, W. F., and Longley, A. (2018). Artistic Approaches to Cultural Mapping: Activating Imaginaries and Means of Knowing (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

Eshun, G., and Madge, C. (2012). “Now let me share this with you”: exploring poetry as a method for postcolonial geography research. Antipode 44, 1395–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00968.x

Evans, R., Kurantowicz, E., and Lucio-Villegas, E. (2022). Remaking Communities and Adult Learning: Social and Community-based Learning, New Forms of Knowledge and Action for Change. Leiden: BRILL. doi: 10.1163/9789004518032

Grile, C. (2013). Creating Art That Truly Reflects The Community: An Exploration Into Facilitation Of Devised, Community-engaged Performance (Electronic Theses and Dissertations). Available online at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2932 (accessed April 24, 2025).

Hardy, L. J., Hughes, A., Hulen, E., Figueroa, A., Evans, C., and Begay, R. C. (2015). Hiring the experts: best practices for community-engaged research. Qual. Res. 16, 592–600. doi: 10.1177/1468794115579474

Hawkins, H. (2011). Dialogues and doings: sketching the relationships between geography and art. Geog. Compass 5, 464–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00429.x

Hawkins, H. (2015). Creative geographic methods: knowing, representing, intervening. On composing place and page. Cult. Geograph. 1474474015569995. doi: 10.1177/1474474015569995

Hawkins, H. (2019). Geography's creative (re)turn: toward a critical framework. Prog. Human Geog. 43, 963–984. doi: 10.1177/0309132518804341

Hawkins, H., and Kanngieser, A. (2017). Artful climate change communication: overcoming abstractions, insensibilities, and distances. WIREs Climate Change 8:e472. doi: 10.1002/wcc.472

Holt, L., Jeffries, J., Hall, E., and Power, A. (2019). Geographies of co-production: learning from inclusive research approaches at the margins. Area 51, 390–395. doi: 10.1111/area.12532

Hunter, A., Lusardi, P., Zucker, D., Jacelon, C., and Chandler, G. (2002). Making meaning: the creative component in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 12, 388–398. doi: 10.1177/104973202129119964

Jacobson, S. K., Seavey, J. R., and Mueller, R. C. (2016). Integrated science and art education for creative climate change communication. Ecol. Soc. 21:26269971 doi: 10.5751/ES-08626-210330

Keesstra, S., Nunes, J., Novara, A., Finger, D., Avelar, D., Kalantari, Z., et al. (2018). The superior effect of nature based solutions in land management for enhancing ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environm. 610–611, 997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.077

Kinkaid, E. (2019). Experimenting with creative geographic methods in the critical futures visual archive. Cultural Geograph. 26, 245–252. doi: 10.1177/1474474018808640

Lancione, M. (2017). The ethnographic novel as activist mode of existence: translating the field with homeless people and beyond. Soc. Cult. Geography 18, 994–1015. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1231336

Lydon, P. M. (2020). “Urban ecology: art and the cultivation of ecological mindsets,” in The Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology (2nd ed.) (London: Routledge).

Lydon, P. M., Maddox, D., Lasser, R., Ribeiro, B., and Vitantonio, C. (2023). Chapter 15: 1 + 1 = 3: Stories of Imagination and the Art of Nature-Based Solutions. Available online at: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap-oa/book/9781800376762/book-part-9781800376762-27.xml (accessed April 24, 2025).

Mackay, S., Klaebe, H., Hancox, D., and Gattenhof, S. (2021). Understanding the value of the creative arts: Place-based perspectives from regional Australia. Cultural Trends 30, 391–408. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2021.1889343

Magrane, E. (2016). A poem is its own animal: poetic encounters at the arizona-sonora desert museum. Ecotone 11, 96–104. doi: 10.1353/ect.2016.0021

Magrane, E. (2017). Creative Geographies and Environments: Geopoetics in the Anthropocene. University of Arizona.

Magrane, E. (2021). Climate geopoetics (the earth is a composted poem). Dial. Human Geograph. 11, 8–22. doi: 10.1177/2043820620908390

Mand, K. (2012). Giving children a ‘voice': Arts-based participatory research activities and representation. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 15, 149–160. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2012.649409

McLean, H., and Leeuw, S. (2020). “Enacting radical change: Theories, practices, places and politics of creativity as intervention,” in Handbook on the Geographies of Creativity. Available online at: http://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781785361630/9781785361630.00028.xml (accessed April 24, 2025).

Moore, K. D., and Haverluck, B. (2022). Orion Magazine—How Art Can Help Defend the Natural World. Orion Magazine. Available online at: https://orionmagazine.org/article/art-nature-activism/ (accessed November 23, 2022).

Morey, C. (n.d.). The Body Listens. The Body Listens. Available online at: https://thebodylistens.weebly.com/the-body-listens.html (accessed April 24, 2025).

Olstad, T. A. (2018). Art as a tool for wilderness management: stewardship and sense of place in Misty Fiords National Monument, Alaska. GeoHumanities 4, 249–261. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2017.1415157

Peters, S., and Barnett, T. (2024). Preparing artists to save the world: community-engaged arts practice as critical pedagogy. Crit. Arts 38, 159–174. doi: 10.1080/02560046.2024.2338355

Sparrow, V. (2006). Telling Stories About Places for Sustainability: A Case Study of the Islands in the Salish Sea Community Mapping Project. Kelowna, BC: University of British Columbia.

Vaart, G., van der, Hoven, B., and van, Huigen, P. P. P. (2018). Creative and arts-based research methods in academic research. lessons from a participatory research project in the Netherlands. Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 19:2. doi: 10.17169/fqs-19.2.2961

van Blerk, L., Hunter, J., Shand, W., and Prazeres, L. (2023). Creating stories for impact: Co-producing knowledge with young people through story mapping. Area 55, 99–107. doi: 10.1111/area.12816

Van Den Bergh, H. (2015). “Art for the Planet's Sake (fresh perspectives on arts and environment, p. 37),” in International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts. Available online at: https://www.ietm.org/en/system/files/publications/ietm-art-for-the-planets-sake_jan2016.pdf (accessed April 24, 2025).

Wilson, R. (2013). Commentary 2: the state of the humanities in geography – a reflection. Prog. Human Geog. 37, 310–313. doi: 10.1177/0309132513475754a

Keywords: nature-based solutions (NbS), art, climate change, artists, community-engaged research, participatory research, artist commissions, arts-based research

Citation: Acker M, Dubrawski KL, Tremblay C, Brill G, Creates M, Hash C, Robinsong E and Howard A (2025) Commissioning community-based art projects to support engagement with nature-based solutions. Front. Sustain. 6:1592706. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1592706

Received: 13 March 2025; Accepted: 14 April 2025;

Published: 07 May 2025.

Edited by:

Christos S. Akratos, Democritus University of Thrace, GreeceReviewed by:

Stella Diakou, T6 Ecosystems, ItalyMei-Hsin Chen, University of Navarra, Spain

Callie Chappell, Stanford University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Acker, Dubrawski, Tremblay, Brill, Creates, Hash, Robinsong and Howard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maleea Acker, bG1hY2tlckB1dmljLmNh; Kristian Lukas Dubrawski, a2R1YnJhd3NraUB1dmljLmNh

Maleea Acker

Maleea Acker Kristian Lukas Dubrawski

Kristian Lukas Dubrawski Crystal Tremblay1

Crystal Tremblay1 Gregg Brill

Gregg Brill