- College of Policy Science, Ritsumeikan University, Ibaraki, Osaka, Japan

The escalating global volume of electronic waste (e-waste), coupled with low recycling rates, poses a significant environmental and public health challenge. This necessitates a deeper understanding of individual disposal behaviors, as e-waste is predominantly a problem due to the low level of individual engagement in the appropriate disposal of these materials. Individual engagement in pro-environmental behavior is as essential as technology implementation in managing the e-waste crisis, as changes in individual behavior could significantly influence environmental outcomes. This study takes a robust cross-cultural approach, surveying a sample of 2,450 university students, including 950 from Vietnam and 1,500 from Japan, who are frequent users of personal electronic devices and generally have high environmental awareness. By integrating the value-belief-norm model, valence theory, and drivers from reverse logistics concepts, this research explores how students in two distinct cultural contexts assess and act regarding e-waste disposal and recycling. Furthermore, this research pioneers the use of the Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire to measure values associated with environmental actions and attitudes in e-waste recycling. Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), the findings demonstrate that recycling inclinations were influenced by personal norms, regulation drivers, economic drivers, ascription of responsibility, and perceived benefits and risks toward e-waste recycling. Among them, regulation drivers had the largest impact in both countries (β = 0.331, p < 0.001, Vietnam; β = 0.344, p < 0.001, Japan). Furthermore, the model is promising for adoption in the field of e-waste recycling in other countries, as indicated by its good model fit (i.e., the root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] < 0.08; NFI, CFI, TLI > 0.9). These discoveries would be helpful for policymakers and researchers in both countries aiming to understand the factors driving students' decisions to recycle e-waste.

1 Introduction

Owing to increasing industrialization and urbanization (Borthakur and Govind, 2018), significant growth of the electronics and electrical sectors has led to a global problem of increased electronic waste (e-waste). E-waste is defined as various kinds of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) waste, including their components disposed of and not intended for reuse (Parajuly et al., 2019). Notably, e-waste contains not only valuable elements such as gold (Au) and silver (Ag) but also hazardous compounds such as lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg) (Nadarajan et al., 2023).

Careless disposal of e-waste can result in the release of toxic substances, which can contaminate soil and water sources, causing extreme environmental and human health damage (Thakur and Kumar, 2022). Furthermore, generated e-waste is estimated to increase to ~82 million tons by 2030 (Statista, 2024). This massive increase in e-waste volume has led to a waste administration issue that poses significant environmental threats and human health-related challenges (Wang et al., 2016; Nadarajan et al., 2023).

This global trend is mirrored at the national level, where countries like Vietnam are experiencing similar challenges with e-waste generation and management. In Vietnam, e-waste has emerged as a significant environmental crisis, with a staggering growth in the consumption of electronic products over the past decade (Nguyen et al., 2019). Vietnam produced ~0.3 million metric tons of e-waste domestically in 2017, and it is projected to increase by 21% by 2030 (Nguyen et al., 2019). Additionally, the unauthorized transportation of electronic waste across borders from nearby nations, also known as “transboundary movement,” leads to a significant amount of e-waste being discarded into landfills (Tran and Salhofer, 2018, p.4). Vietnam still relies heavily on an informal system that focuses on dismantling or refurbishing discarded appliances over recycling them (Tran and Salhofer, 2018). Unused parts are disposed of in landfills (Hai et al., 2017). Furthermore, Vietnam lacks formal legislation on the issue of e-waste (Tran and Salhofer, 2018), which leads to widespread improper disposal and recycling practices.

To promote the recycling of electronic devices, Japan has implemented legal frameworks and laws, such as the “Home Appliance Recycling Law (2001)” and “Small Home Appliance Recycling Law (2013)” (Itoh, 2014, p.2). Researchers have also been designing effective recycling systems for small devices (Torihara et al., 2015). Despite legislation and facilitated institutions aimed at promoting recycling, Japan is struggling to keep pace with its e-waste generation. The country now generates ~2,579 thousand tons annually, but its collection and recycling rate remains low at 23% (OECD, n.d.).

Despite the urgent need for effective e-waste management, a major problem persists: individual engagement in responsible e-waste disposal and recycling remains insufficient, even in countries with existing policies and awareness efforts. This lack of individual participation is particularly concerning among university students, who are frequent users of electronic devices (Zhang et al., 2019) and represent a critical demographic for future e-waste generation.

Individual engagement in pro-environmental behavior is an important factor in managing the e-waste crisis (Yuriev et al., 2018; Dhir et al., 2021), as changes in individual behavior can significantly influence environmental outcomes (Yadav et al., 2022). While previous studies have examined residents' e-waste recycling intentions (Nguyen et al., 2019; Dhir et al., 2021; Nadarajan et al., 2023), few studies have discussed students' perceptions and behavioral intentions toward e-waste recycling. University students can be considered one of the most influential groups in studying the usage and disposal of electronic devices for several reasons. First, personal electronic devices have become universal within the demographic (Kobus et al., 2013), with studies indicating that students possess more electronic devices on average than other population segments (Zhang et al., 2019; Adeel et al., 2023). This high consumption rate positions them as a critical source of future e-waste generation, making their disposal awareness and practices essential to investigate. Second, these students typically exhibit a greater awareness of global resource limitations and environmental issues and a greater openness to exploring novel solutions (Calculli et al., 2021). Finally, targeting students directly addresses a well-defined gap in the literature, which has often focused on the general public data. By concentrating on students, this study can provide in-depth results that are beneficial for forming targeted policies on young consumers, especially in developing nations like Vietnam.

Additionally, there is a lack of research comparing awareness levels between developed and developing countries, which differ in various aspects. The selection of Vietnam and Japan is based on several reasons. Firstly, both nations share a broadly collectivistic Asian cultural foundation (Shwalb et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the two nations represent opposite ends of the economic and regulatory spectrum. While Vietnam was a lower-middle-income country with a GDP per capita of 4.17 thousand dollars in 2022, Japan was roughly eight times higher than that at 34.07 thousand dollars (World Bank, n.d.). Moreover, while Vietnam has no official law on e-waste, Japan has enacted legislature since the 2000s. This shared cultural context (e.g., social harmony), yet significant differences in terms of systemic conditions make it meaningful to compare how core values and norms function in both societies when other external factors (e.g., regulation, economy) are involved.

Secondly, Vietnam's rapid economic growth and surging demand for electronic devices (Nguyen et al., 2019) make e-waste a pressing issue comparable to Japan. Alongside, despite Japan's advanced technology and legal framework, its e-waste recycling rate is considerably low (OECD, n.d.), pointing to a crucial gap between policy and individual psychology. Investigating the underlying causes is therefore essential, allowing our study not only to uncover the psychological drivers among students in both nations but also to position Japan's experience as an empirical case study that can proactively inform Vietnam as it develops e-waste management frameworks. This leads to the central research question of this study:

RQ: What are the key psychological and contextual determinants shaping e-waste recycling intentions among university students in different national settings of Vietnam and Japan?

To answer this question, this study explicitly focused on five high-tech electronic devices with short lifecycles: smartphones, laptops, tablets, digital cameras, and headphones/earphones (Zhang et al., 2019). We examine the intentions of Vietnamese and Japanese students by employing an integrated theoretical framework that combines the value-belief-norm (VBN) model with key factors from valence theory (VT) and the reverse logistics (RL) concept. By integrating these theoretical perspectives, this study aims to advance the understanding of the drivers shaping students' intentions to recycle e-waste across cultures. This research will not only uncover key determinants of recycling behavior but also provide actionable insights for designing more effective interventions and policies to promote sustainable e-waste management among young consumers.

2 Conceptual framework and hypotheses development

2.1 VBN model

Stern et al. (1999) argued that the VBN model may serve to holistically comprehend and reliably predict individuals' pro-environmental behavior. As fundamental principles in human life, values can directly and indirectly influence people's decision to engage in sustainable behaviors (Stern and Dietz, 1994; Verma et al., 2019), instilling confidence in the VBN model's ability to predict people's behavioral intentions.

Stern and Dietz (1994) indicated that a strong value orientation toward the environment would likely lead individuals to selectively seek and accept information on environmental issues (i.e., environmental concerns, ECs). According to Schwartz (1977), once these individuals recognize that their (in)actions impact other people and the environment, they start to develop such awareness of consequences (AC). This awareness leads them to attribute accountability for the outcomes of those behaviors (i.e., ascription of responsibility, AR). As a result, they develop a personal sense of moral obligation, or personal norms that motivate them to act in environmentally friendly ways Stern et al., (1999), such as recycling e-waste.

VBN theory has been applied globally, with studies exploring its implications in various contexts, such as green hotel visit intention (Wang et al., 2023; Dong et al., 2024), sustainable tourism (Park et al., 2022) and green energy adoption (Fornara et al., 2016). However, its application in e-waste recycling is emerging (Wang et al., 2018; Sari et al., 2021; Nguyen, 2023) and should be further investigated.

2.1.1 Altruistic-biospheric values

Values can be defined as the beliefs upon which individuals predict their actions and assess specific situations (De Groot and Steg, 2008). Those with strong altruism prioritize others' well-being, whereas those who prioritize biospheric values demonstrate concern about the impact of their behaviors on the environment and ecosystem (Stern et al., 1999). (Stern et al. 1999) proposed a positive correlation between environmental beliefs and altruistic and biospheric values, the importance of which previous studies have highlighted in influencing sustainable actions (Dong et al., 2024).

Altruistic and biospheric values are measured as a single construct in this study based on empirical, methodological, and cultural grounds. In the original VBN theory, the distinction between altruistic and biospheric values is unclear, leading to the amalgamation of altruistic-biospheric value orientation into a single variable (Stern et al., 1995). From a methodological standpoint, this high degree of empirical overlap would likely create significant problems with discriminant validity if treated as separate constructs, as they would fail to demonstrate statistical uniqueness (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Additionally, this approach is further supported by the cultural contexts of Vietnam and Japan. In many Easter and collectivism cultures, the Western distinction between society (altruism) and nature (biospherism) is less pronounced, with worldviews often emphasizing the harmony and interconnectedness of the surroundings (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). Therefore, treating these values as one construct would be beneficial for creating a more culturally and statistically robust measurement. According to VBN theory, human values are anticipated to influence beliefs. Consequently, the following hypothesis is formulated:

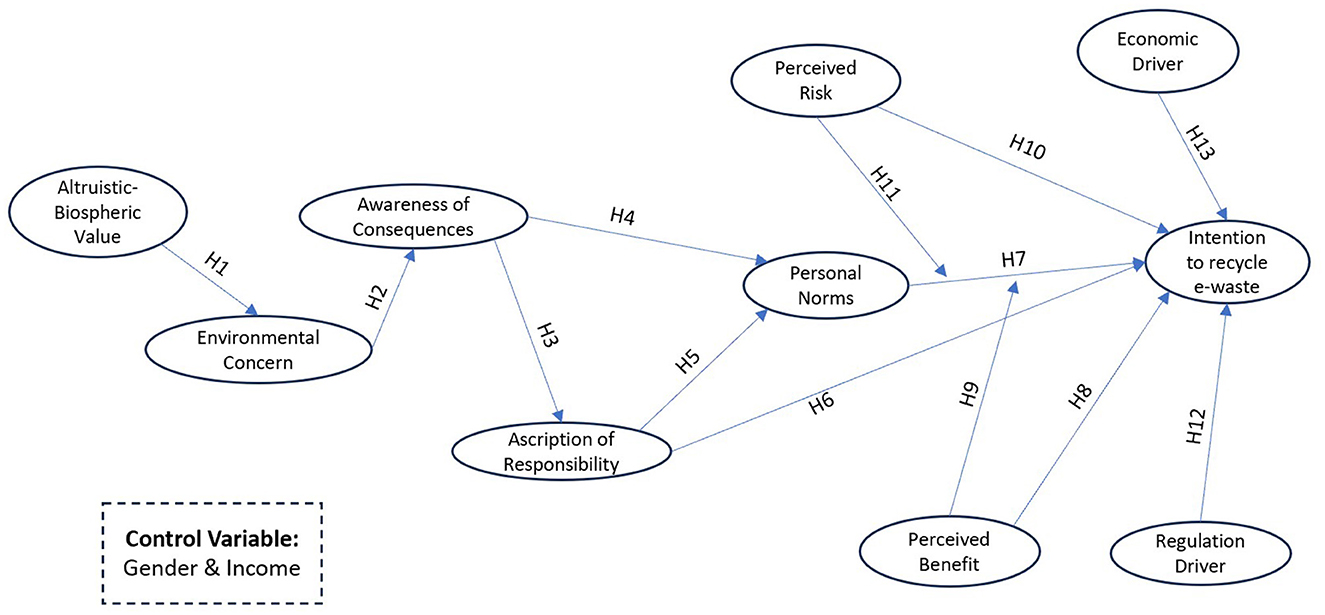

H1: Altruistic-biospheric values positively affect students' ECs about e-waste recycling.

2.1.2 Impact of beliefs-norms on intentions

Regarding the belief-norm component of VBN theory, EC positively affects AC (Stern and Dietz, 1994; Hein, 2022). Previous research has demonstrated that AC positively affects PN regarding sustainable acts such as public transit usage (Harland et al., 2007) and adopting electric vehicles (He and Zhan, 2018). Previous studies have also demonstrated the importance of AR in pro-environmental behaviors (Dong et al., 2024) and investigated the mediation of PNs on the correlation between attributed responsibility and behavioral intentions (Dong et al., 2024). Finally, PN is an essential indicator of behavioral intentions (He and Zhan, 2018; Rahman et al., 2020). VBN theory suggests that people with high EC are likely to have a higher AC, which leads to increased AR and, subsequently, heightened PN, which ultimately predicts environmental intention and behaviors (Schwartz, 1977; Stern et al., 1999). This sequence is supported by studies with empirical evidence from different contexts, such as green energy adoption intentions (Fornara et al., 2016), municipal solid water separation (Li et al., 2018), car use and policy pricing (Hiratsuka et al., 2018), and e-waste recycling (Wang et al., 2018). Accordingly, the subsequent hypotheses are presented:

H2: ECs positively affect student awareness of adverse consequences of e-waste recycling.

H3: AC positively affects students' AR in an e-waste recycling context.

H4: AC positively affects PNs in an e-waste recycling context.

H5: AR positively affects PNs in an e-waste recycling context.

H6: AR positively affects students' intention to recycle e-waste.

H7: PNs positively affect students' intention to recycle e-waste.

2.2 VT

With roots in economics and psychological science, VT highlights perceived benefits (PBs) and perceived risks (PRs) as central components influencing decision-making processes (Peter and Tarpey Sr, 1975). Thus, VT could contribute to tackling the Theory of Planned Behavior's shortcomings in identifying how users make compromises when PBs and PRs are involved in the evaluation (Peter and Tarpey Sr, 1975). Therefore, VT would adequately and effectively account for a more significant variance in consumer intentions than independent models that focus solely on PRs or PBs (Dhir et al., 2021).

VT has become a theoretical foundation for adopting pro-environmental behavior because of its integrated evaluation of favorable and unfavorable perceptions. For instance, Xiao et al. (2021) studied negative and positive valence in the context of online health services, approval of mobile payment (Ozturk et al., 2017), and e-waste recycling (Dhir et al., 2021; Nadarajan et al., 2023).

2.2.1 PB

Individuals' perceptions of certain actions might be positively influenced by perceived advantages (Peter and Tarpey Sr, 1975). Improper disposal of obsolescent devices or their sale to informal collectors and second-hand vendors might lead to several detrimental effects, encompassing risks to the well-being of individuals and environmental dangers (Dwivedy and Mittal, 2013). Hence, safeguarding the ecosystem and alleviating health concerns caused by illicit e-waste disposal might incentivize consumers to recycle e-waste (Dhir et al., 2021). Additionally, factors including self-determined demands, contentment, and internal motivation positively predict people's intent to partake in e-waste recycling (Gilal et al., 2019) and purchase of green vehicles (Wang et al., 2024), implying that PBs significantly influence individuals' intentions toward pro-environmental behavior.

Reportedly, the recognition of advantages forecasted PNs related to the willingness to engage in behaviors (De Groot and Steg, 2010). In this study, we posit that PBs exert a direct impact and are incorporated to measure the moderating impact, thereby modifying the relationship between PNs and students' behavioral intentions. Hence, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H8: PB positively affects students' intention to recycle e-waste.

H9: PB positively moderates the association between PNs and the intention to recycle e-waste.

2.2.2 PR

Perceived drawbacks can negatively influence students' intentions to recycle e-waste (Peter and Tarpey Sr, 1975) and people who perceive greater risks have a lower probability of engaging in a particular behavior (Dhir et al., 2021). Researchers in diverse disciplines have indicated the importance of risk perceptions when studying pro-environmental behavior, electric vehicle purchases (He et al., 2018), and green smartphone purchases (Raj et al., 2023). Within the realm of e-waste disposal and recycling, people perceive potential risks associated with the theft of private data, wasted time and effort, and financial loss. Notably, perceived economic loss negatively affects e-waste recycling intentions through online platforms (Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, as recycling inconvenience increases, the intention to recycle decreases (Nguyen et al., 2019).

Additionally, people's propensity toward nuclear energy is guided by their PNs, which are predicted by their risk perceptions (De Groot and Steg, 2010). Similarly, Pangaribuan et al. (2022) proposed that the connection between personal beliefs and voluntary participation weakens when PR increases. Thus, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H10: PR negatively affects students' intentions to recycle e-waste.

H11: PR negatively moderates the association between PNs and the intention to recycle e-waste.

2.3 RL

RL factors, including economic drivers, regulation drivers, and corporate citizenship (Akdogan and Coşkun, 2012), were preliminarily tested to effectively anticipate consumers' intentions to engage in e-waste recycling initiatives (Sari et al., 2021). This study adopted economic and regulatory drivers to predict university students' intentions to recycle e-waste.

2.3.1 Regulation drivers

Regulation drivers encompass regulatory measures or initiatives undertaken by government authorities to minimize the environmental impact of end-of-life products (Sari et al., 2021). Nguyen et al. (2019) suggested that regulations positively affect residents' willingness to recycle e-waste. Furthermore, the enactment and dissemination of laws have enhanced eco-consciousness among residents, thereby increasing their readiness to recycle e-waste (Wang et al., 2016). Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested:

H12: Regulation drivers positively affect students' intention to recycle e-waste.

2.3.2 Economic drivers

Economic drivers, which focus on encouraging consumers to return and recycle products and materials (Sari et al., 2021), have been studied (e.g., “cost of recycling”; see Nguyen et al., 2019, p.6). Wang et al. (2016) demonstrated that people may feel reluctant to recycle e-waste if the costs are high. Furthermore, Sari et al. (2021) indicated that incentives and penalties in financial terms are necessary to align motivations in the intended direction. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H13: Economic drivers positively affect students' intention to recycle e-waste.

2.4 Control variables

This study employed gender and income as control variables. Gender plays a significant role in e-waste recycling. Women are more likely than men to embrace recycling and sustainable acts (Milovantseva and Saphores, 2013; Echegaray and Hansstein, 2017).

The intention to act sustainably has also been found to be impacted by income. Low-income people are more inclined to keep outdated electronics than to recycle them (Milovantseva and Saphores, 2013). Contrarily, others claimed that people with lower wages are more inclined to recycle e-waste, noting a decrease in their willingness to recycle as their income increases (Echegaray and Hansstein, 2017).

While VT effectively examines behavioral aspects, it overlooks individuals' subjective psychological perceptions, as their values encapsulate (Dhir et al., 2021). The VBN model could fulfill this aspect by providing well-constructed variables for measuring students' values, beliefs, and norms. Furthermore, two factors from RL drivers could provide insights into how contextual factors (i.e., regulation and economic drivers) impact behavioral intentions. Hence, this research integrates VT, VBN theory, and RL drivers to investigate university students' e-waste recycling intentions. Figure 1 portrays the research model.

3 Method

3.1 Measurement and questionnaire

We formulated a questionnaire based on a thorough literature review. In the introduction, we explicitly underscored the significance of accurate data collection to minimize response inaccuracies. Additionally, we assured the respondents that the collected data would be solely utilized for scientific purposes and that their personal information would remain confidential. We explained that there is no (in)correct answer and the importance of honest answers, to reduce social desirability bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To ensure that the measurement items fit the study context, we conducted qualitative interviews with five and three university students from Vietnam and Japan, respectively. These interviews aimed to discover their understanding of the field and other possible factors to consider when constructing a survey. We eventually added one item to measure PBs: “I feel satisfied when I recycle e-waste” after the interview, with careful information selection, making it a total of 50 questionnaire items. This aligns with previous studies regarding the impact of satisfaction and self-determined factors on pro-environmental intentions (Gilal et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2024). We then translated the survey into Vietnamese and Japanese and pilot-tested it with the same two groups of Vietnamese and Japanese students for comprehensive checking through the focus groups. This pilot testing resulted in improvements to the items for language and guaranteed that the survey instruments function well in different languages.

The main body of the questionnaire was separated into two parts. The first part included demographic questions such as gender, enrolment year, and monthly income. We then provided respondents with a definition of e-waste and the target devices, followed by open-ended questions about whether the university students acknowledged e-waste recycling methods. We also asked questions about the number of unused obsolete electronic devices belonging to our research targets and how they are currently being treated.

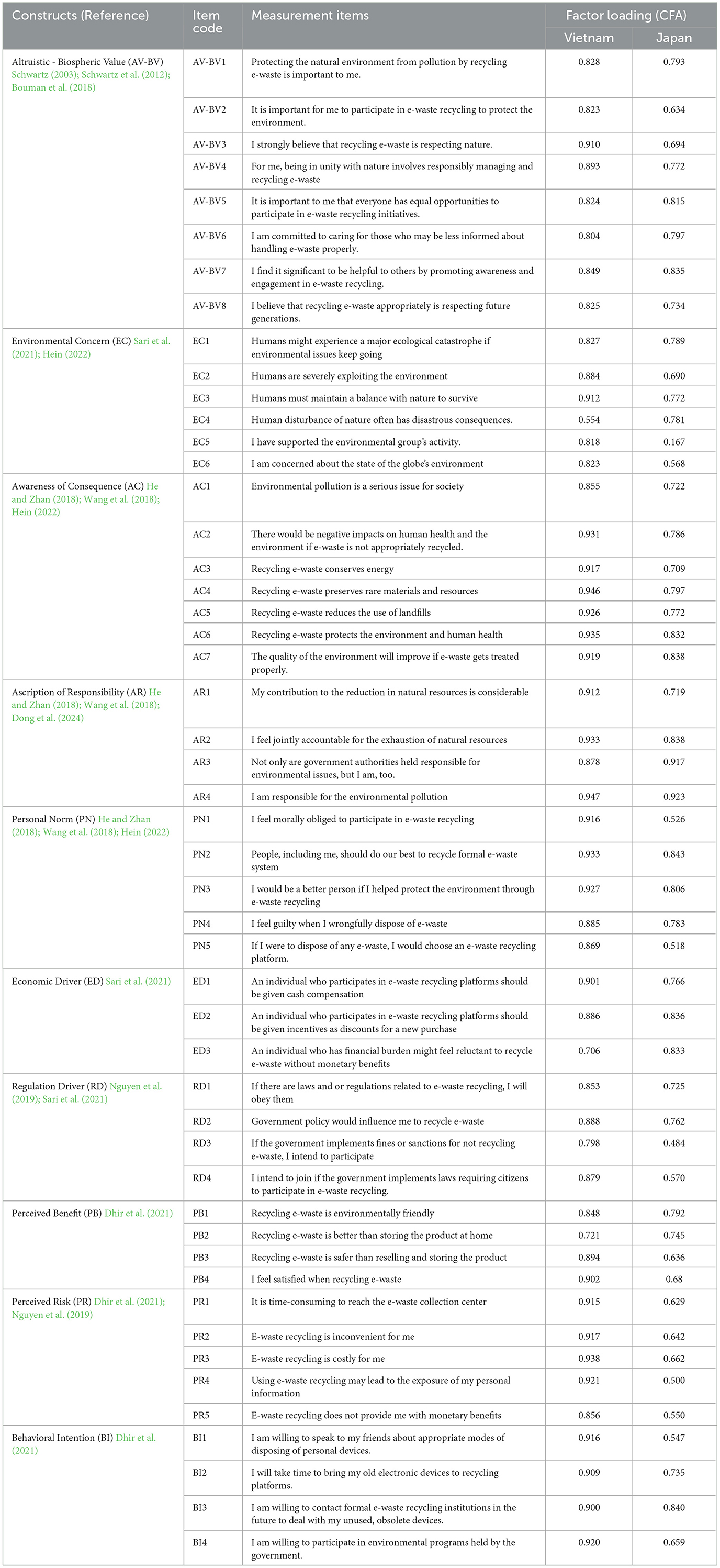

The second part of the survey focused on measuring the constructs and hypotheses. Utilizing a 5-point Likert scale for all items, participants were requested to indicate their degree of agreement with each item (i.e., “strongly disagree” = 1 point; “strongly agree” = 5 points). We judged the 5-point Likert scale was favorable as both Vietnam and Japan shared cultural characteristics, where values of social harmony and modesty often lead to a preference for moderate expression by people in surveys (Heine et al., 2002). Wakita et al. (2012) implied that respondents generally feel comfortable answering through a 5-point scale, resulting in more valid responses. Additionally, we intentionally included two trap questions to ensure the quality of the response. We screened the questionnaires under rigorous standards: respondents who failed to answer two trap questions (e.g., Please choose “4. Agree” for this question) or provided identical answers for all questions (indicating inattentive participation) were eliminated. All the items, including the response scale, are provided in Table 1.

Developed initially by Schwartz (1994), after being modified and extended by Stern et al. (1998) and Steg et al. (2014), the Environment Schwartz Value Survey (E-SVS) was primarily adopted to study people's biospheric and altruistic values. Despite its robust validation, participants often need clarification to answer questions, particularly those from non-Western communities (Bouman et al., 2018). Therefore, the Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (E-PVQ) (Schwartz, 2003; Schwartz et al., 2012) was proposed as a more accessible alternative (Bouman et al., 2018). Respondents in our qualitative interviews also found the E-PVQ items to be more comprehensible. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine these items within the context of e-waste and, thus, has pioneered the use of the E-PVQ to measure values associated with environmental actions and attitudes in e-waste recycling.

3.2 Data collection and sampling

In Vietnam, convenience stratified sampling—dividing a readily available population (i.e., Thai Nguyen Medical and Pharmaceutical University's students) into distinct year levels (e.g., undergraduate 1st year, Master's program 2nd year) and selecting participants from each stratum—was utilized. One of Vietnam's most developed cities, Thai Nguyen, is an industrial hub that is home to Samsung Electronics, which operates two electronic factories. While the city does not yet have a certified formal e-waste recycling institution, growth in investment and the necessity for sustainable development will soon prompt the establishment of such institutions. This indicates the importance of studying how consumers, particularly Thai Nguyen students, behave toward this issue. Moreover, Thai Nguyen has the largest university system in the northern midlands and mountainous regions, attracting numerous students from areas surrounding the city. Therefore, it was selected as the research target area, to better understand students' perceptions and behavioral intentions, which will help implement policies in Thai Nguyen and all cities in Vietnam.

The survey was distributed to students of all grades using Zalo—a popular communication platform in Vietnam, with the assistance of the Office of Student Affairs at Thai Nguyen Medical and Pharmaceutical University. To maximize participation, biweekly reminders were sent to students (focusing on first through fourth-year) for a month. Data were collected between February and March, 2024 using Google Forms. To prevent item-level missing data, all questions in the survey were set as mandatory. Google Forms did not allow participants to proceed to the next page or submit the final form without providing an answer to every question. Thus, for those who dropped out in the middle of the survey, their responses were not saved or counted. Moreover, the survey was configured to “Limit to 1 response” per Google account. This required respondents to be signed into a Google account, providing a technical barrier against single users submitting multiple forms. The survey reached 3500 students who majored in General Medicine. A total of 1008 respondents were included in this study, reflecting a 28.8% response rate. 36 responses were eliminated due to inattentive participation and failing to answer the trap questions. A total of 972 valid responses were obtained (recovery rate = 96%).

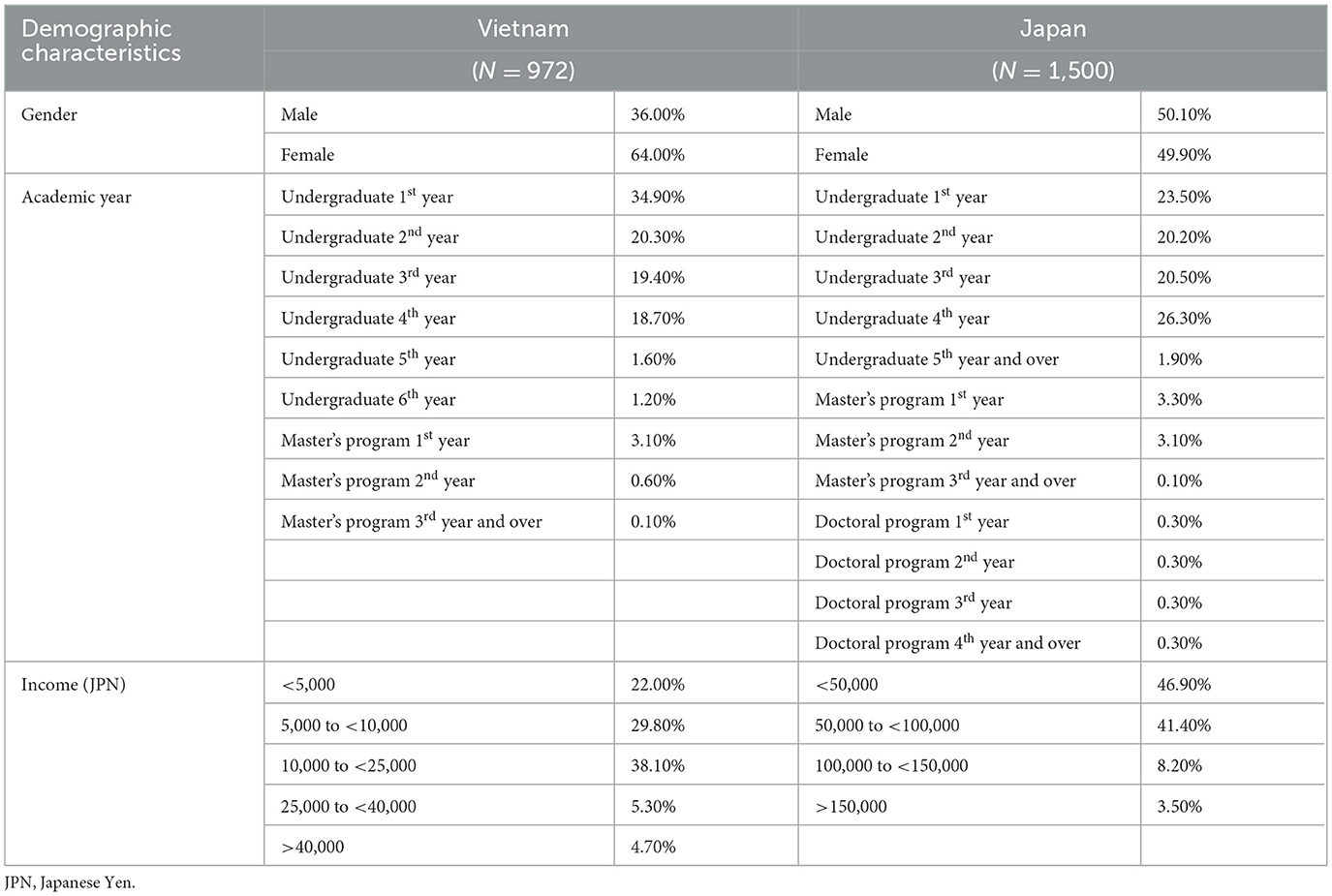

For Japan, data were collected by Cross Marketing (2024), a prominent survey marketing firm that boasts a user base exceeding 2.2 million registered individuals in Japan. Stratified sampling was used to recruit university students across the country, with the sample stratified by gender, geographical region, and academic year. Geographically, respondents were categorized by all 47 prefectures, ensuring a nationwide spread of data. The questionnaire was administered online, requiring the completion of all items to avoid unfinished answers and data gaps. Similar to the survey distributed to Vietnamese students, two trap questions were used to identify and eliminate inattentive respondents. A total of 1,500 questionnaires were administered. Demographic information is presented in Table 2.

3.3 Data analysis

Both datasets were subjected to normality tests before further analysis. Following the guidelines recommended by Hair et al. (2010), skewness and kurtosis were evaluated, with skewness values should be within the ±2 range and kurtosis values within the ±7 range. For the Vietnam data, skewness values ranged from −0.800 to −0.075 and kurtosis values ranged from −0.678 to 1.896. For the Japan data, skewness values ranged from −0.887 to 0.063 and kurtosis values ranged from −0.223 to 1.345. As all values for both datasets fell well within the acceptable thresholds, the data were considered approximately normally distributed and suitable for subsequent SEM analysis. Additionally, following Tabachnick and Fidell's (2012) guideline that Z-scores exceeding 3.29 indicate outliers, 22 outliers were identified and removed from the Vietnam dataset, leaving 950 samples for analysis. No outliers were detected in the Japan dataset, allowing all 1,500 responses to be included. In addition, Cook's Distance was calculated to identify potential influential observations (Cook, 1977). For the Vietnam dataset, values ranged from 0 to 0.17, and for Japan, from 0 to 0.029, both well below the threshold of 1. These results confirmed that neither dataset contained significant outliers nor influential points, and no further adjustments were necessary. Finally, a test for multicollinearity was conducted by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for all predictor variables.

The statistical evaluation process comprised three stages. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) evaluated the theoretical framework's validity and reliability. The criteria were determined employing a set of statistical assessments suggested in previous research (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010). To ensure content validity of the questionnaire items, they were drawn from the body of current research on recycling e-waste and individual attitudes. Pilot study results confirmed face validity. Finally, convergent validity was assessed by examining the factor loading estimates, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE).

Second, after establishing the validity of the measurement models, we utilized Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) to validate the formulated hypotheses. This approach was chosen because the primary objective of this study is theory testing and confirmation, a goal for which CB-SEM is deemed to be the most appropriate method (Dash and Paul, 2021; Usakli and Rasoolimanesh, 2023).

In our study, all latent constructs were conceptualized as reflective. In a reflective model, the latent construct is considered a manifestation of the underlying latent variable; therefore, changes in the latent construct are reflected in changes in all indicators. This approach is appropriate because our constructs (e.g., Personal Norms) are theorized to cause the observed indicators, which are expected to be highly correlated (Usakli and Rasoolimanesh, 2023). This contrasts with the formative model, where constructs are indices formed by their measures. Given this factor-based measurement philosophy, CB-SEM is the optimal analytical tool because of its capacity to assess the congruence between the observed covariance of the reflective indicators and the relationships proposed by the theory. To ensure rigorous evaluation, we assessed the model's goodness of fit using both standard thresholds (Hu and Bentler, 1999) and the most recent methodological advances in dynamic fit criteria by generating dynamic cut-offs for model fit indices. This analysis was conducted in RStudio (version 2024.12.1+563) (Posit Team, 2025), following the approach outlined by McNeish and Wolf (2023), using the R package dynamic version 1.1.0 (Wolf and McNeish, 2022).

Given the cross-cultural nature of this study, a formal test of measurement invariance was conducted to ensure that the constructs were measured equivalently across the Vietnamese and Japanese samples. Following a hierarchical procedure (Putnick and Bornstein, 2016), we tested for configural and metric invariance using SPSS AMOS. After establishing measurement invariance, a multi-group analysis (MGA) of the structural paths was performed to formally test for significant differences in the hypothesized relationships between the two countries.

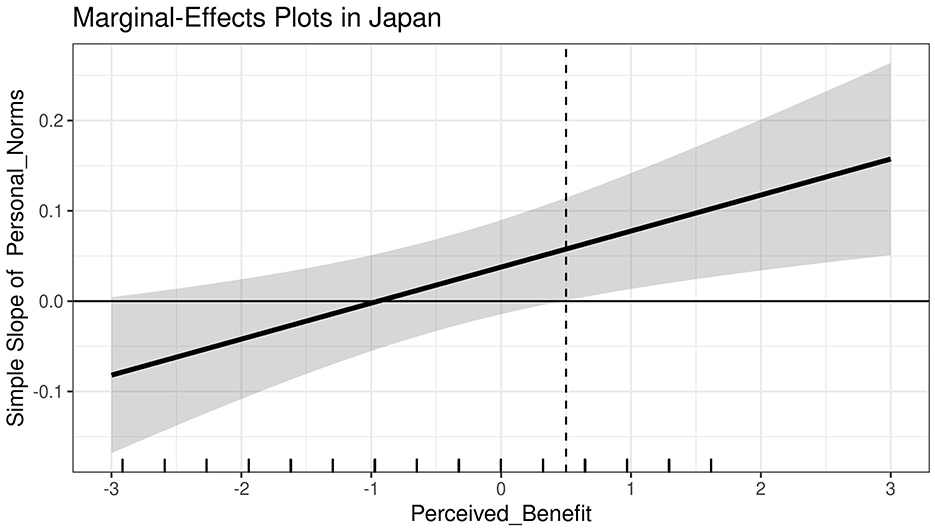

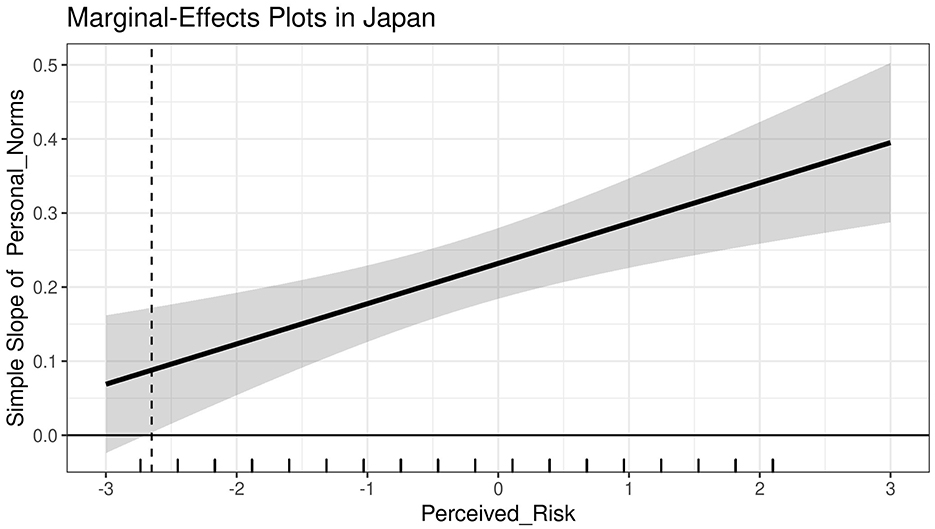

Finally, the proposed moderating effects in the theoretical framework were tested. AMOS (version 28.0) was used for CFA and SEM. Moderation analysis for hypotheses H9 and H11 was conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (version 28.0), and marginal-effects plots were generated with the interActive tool provided by McCabe et al. (2018).

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive results

Regarding the number of obsolete devices per student in both countries, students usually had more than one smartphone, laptop, and headphones/earphones. Specifically, 39.4% of Vietnamese students and 34.8% of Japanese students owned one unit of an obsolete smartphone. Similarly, for headphones/earphones, 33.6% of Vietnamese students owned one unit and 14.1% owned two units, whereas 25.7% of Japanese students owned only one unit and 14.2% owned two units. In both categories, Vietnamese students owned more devices than Japanese students, regardless of the gaps in the two countries' income and economic backgrounds.

Typically, students in both countries were more likely to store these obsolete devices at home. However, ~20% of students in Vietnam dispose of these devices by selling them to a second-hand store, except for headphones/earphones, at 14.8%. This number is relatively low in Japan, with only 9.5% for smartphones and < 6% for all other devices. Notably, in both countries, ~11% of the students indicated that they discarded their headphones/earphones in regular trash. This value is significantly higher than that of other devices (between 0.4% and 1.7 %). This matches our expectations, as headphones/earphones are relatively small compared with other devices.

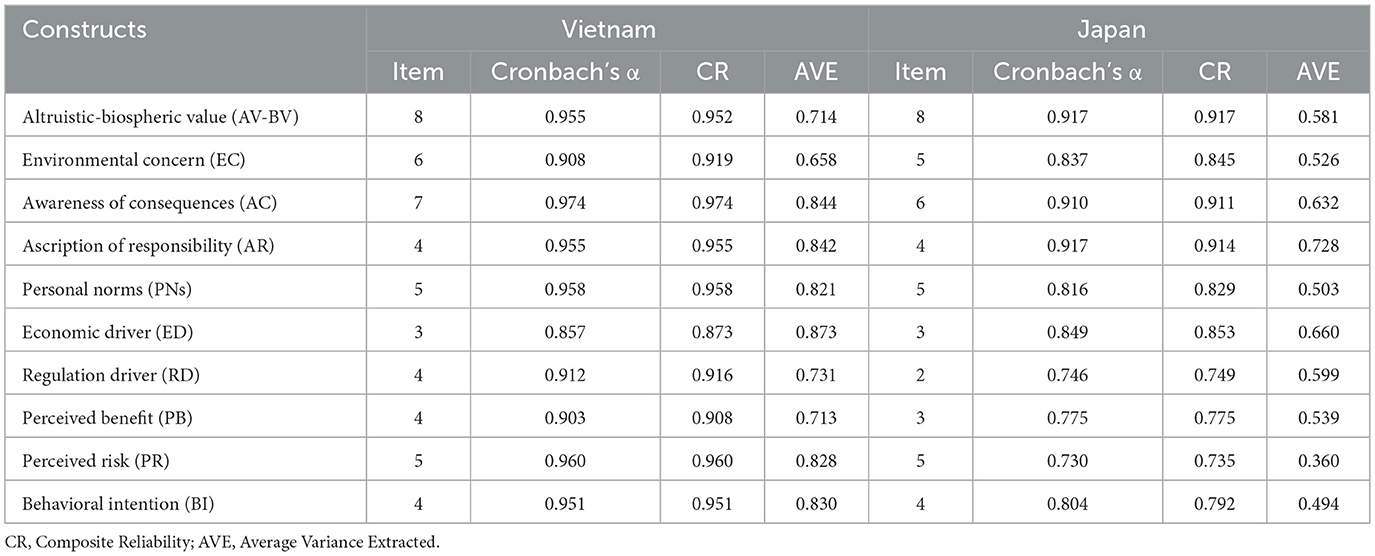

4.2 Validity and reliability

For Vietnam's data, all item factor loadings surpassed 0.50; Cronbach's α-value was above 0.70 (cut-off value for Cronbach's α), and CR and AVE values for all variables were above 0.70 and 0.50 (cut-off values for CR and AVE), respectively. Conversely, in Japan, the EC5 and RD3 indicators were discarded from the SEM analysis because of low factor loadings (i.e., < 0.50). AC1, RD4, and PB4 were removed because of model fit discrepancies (i.e., inflating the chi-square). Furthermore, although all the constructs had a Cronbach's α-value larger than 0.70 and CR values were >0.70, AVE values for PR and BI constructs were lower than the threshold of 0.50, at 0.36 and 0.494, respectively. However, Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggested that if AVE is < 0.5, but CR is >0.7, the convergence of the construct is considered adequate. Thus, both the Vietnamese and Japanese survey instruments are judged to have well-established validity and reliability. For detailed values of each construct, see Table 3.

4.3 Measurement model

Before testing the measurement model with AMOS, to ensure the stability and the reliability of the estimates of the model, an assessment for multicollinearity was conducted. We calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all predictor variables for both the Vietnamese and Japanese datasets.

The VIF values ranged between 1.891 and 2.783 in Vietnam, and between 1.210 and 2.600 in Japan. As all VIF values for both countries were found to be substantially below the 5.0 threshold (James et al., 2013), we judged that multicollinearity is not a concern in this study, and confirmed the suitability of the data for SEM analysis.

After testing the measurement model with various model fit indices, it was determined that certain fitting indicators required modifications. Minor adjustments were made by connecting the error terms of indicators within the same constructs to enhance the goodness of fit for both Vietnam's and Japan's models. For Vietnam, the chi-square value was χ2 (1,127, n = 950) = 4,782.586, p < 0.001, while for Japan, it was χ2 (896, n = 1,500) = 4,399.189, p < 0.001. The significant p-values for χ2 in both models suggest that the alignment between the hypothesized models and the sample data was insufficient. However, Rigdon (1995) noted that the χ2 statistic is sensitive to sample size and model complexity, making it less reliable for large samples like those in this study.

The incremental fit measures in Vietnam (NFI = 0.919, CFI = 0.937, and TLI = 0.931) and Japan (NFI = 0.902, CFI = 0.920, and TLI = 0.912) all exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.9 (Hair et al., 2010). Additionally, the RMSEA values were 0.058 for Vietnam and 0.051 for Japan, both below the maximum acceptable value of 0.08.

The Dynamic Fit Index (DFI) analysis was conducted to provide a more nuanced understanding of model fit. The DFI results revealed areas of misspecification in both models. For Vietnam, while the SRMR = 0.042 aligns with the Level 2 cutoffs (SRMR ≤ 0.045), the RMSEA and CFI fall between Level 6 (RMSEA ≤ 0.054, CFI ≥ 0.952) and Level 7 (RMSEA ≤ 0.064, CFI ≥ 0.932) thresholds. These findings suggest that while residual errors were reasonably well-captured, some model refinement may still be needed. For Japan, although the RMSEA remains within Level 6 (RMSEA ≤ 0.051), the SRMR = 0.061 and CFI fail to meet the Level 9 cutoff (SRMR ≤ 0.059, CFI ≥ 0.922), indicating notable residual discrepancies. McNeish and Wolf (2023) stated that a model with misspecification might still be valuable, thus, there are merits in investigating both models, particularly given their complexity and the insights offered by large sample sizes.

4.4 Structural model

Before examining the proposed hypotheses through SEM, the structural model's fit indices were assessed. The chi-square value for the structural model in Vietnam was χ2(1,239, n = 950) = 5,469.246, while in Japan, it was χ2(920, n = 1,500) = 5,979.047. The incremental fit indices were good for Vietnam, with NFI = 0.908, CFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.922, and RMSEA = 0.06. For Japan, NFI = 0.866, CFI = 0.884, TLI = 0.875, and RMSEA = 0.061. A full discussion of the marginal fit for the Japanese sample is provided in the Discussion section. Path coefficients were estimated in the following step, and their impact was evaluated.

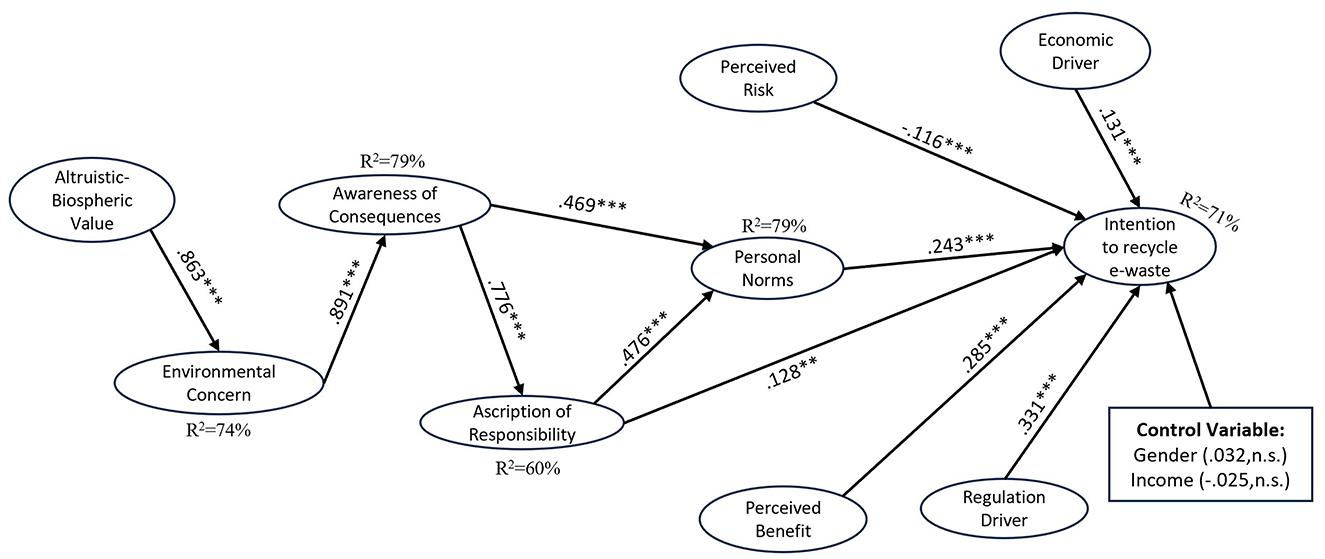

4.4.1 Direct effects analysis

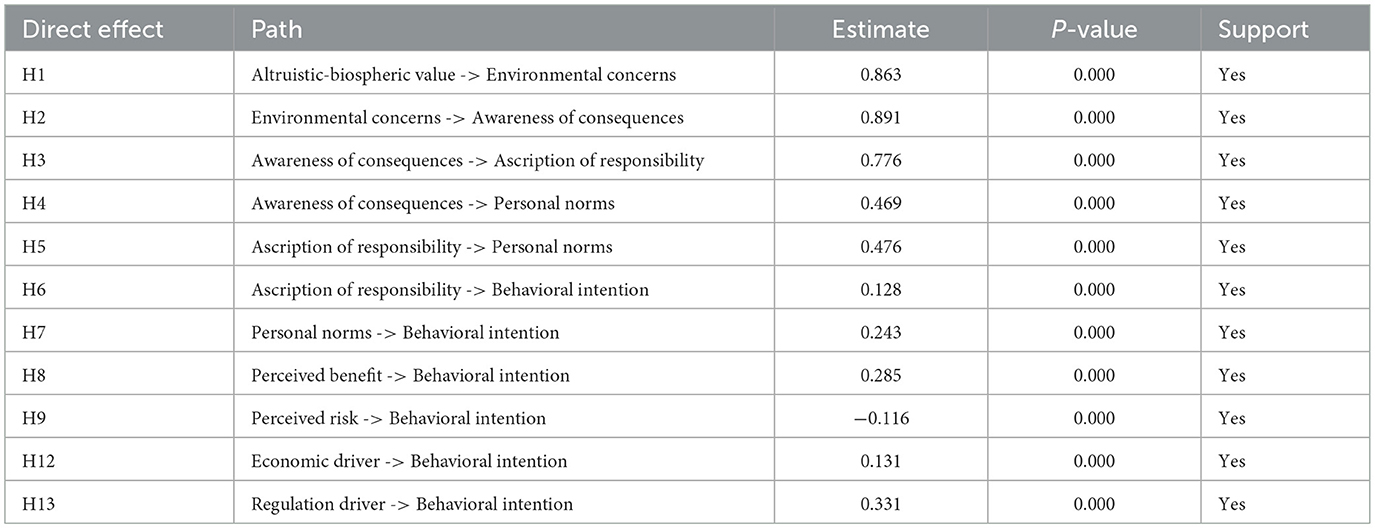

For Vietnam, the VBN model sequences were validated: altruistic-biospheric values positively influenced EC (p < 0.001), which positively impacted AC (p < 0.001), leading to a high AR (p < 0.001), which then activated PNs p < 0.001), ultimately affecting the intention to recycle p < 0.001). This implies that H1, H2, H3, H5, and H7 were supported. Direct effects also showed significant associations between AC and PNs (p < 0.001) and AR and intention to recycle (p < 0.001); thus, H4 and H6 were supported. H8 and H10 indicated a substantial correlation between PB and PR with recycling intentions (both with p < 0.001). Regulation and economic drivers positively influenced recycling intentions, with regulation showing a stronger effect (p < 0.001) than economic factors (p < 0.001). These factors explained 71% of the variance in recycling intentions, as indicated by the R2 = 0.71 (Figure 2). For the path coefficient estimation results, see Table 4.

Figure 2. Testing results of the research model in Vietnam. This figure shows the results of hypothesis testing in Vietnam using the SEM framework. The effect size of each construct on intentions to recycle e-waste was calculated and R-squared was also included. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01: ***p < 0.001; n.s., non-significant. The figure illustrates the hypothesis outcomes within the SEM framework. The solid lines signify that the hypothesis is supported, indicating a statistically significant relationship or effect within the model.

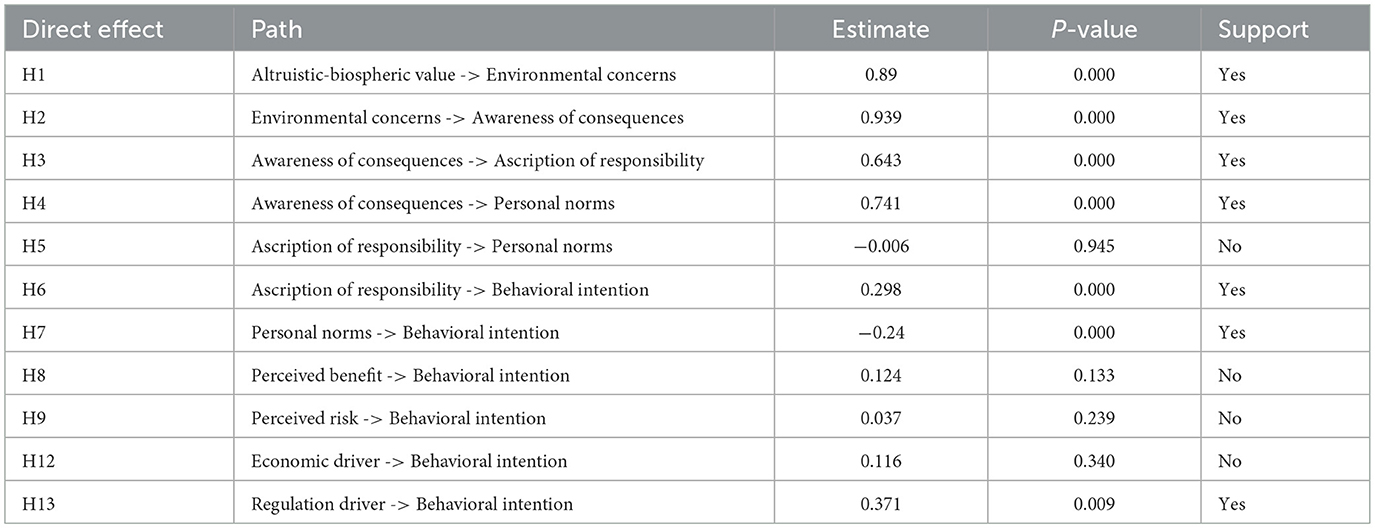

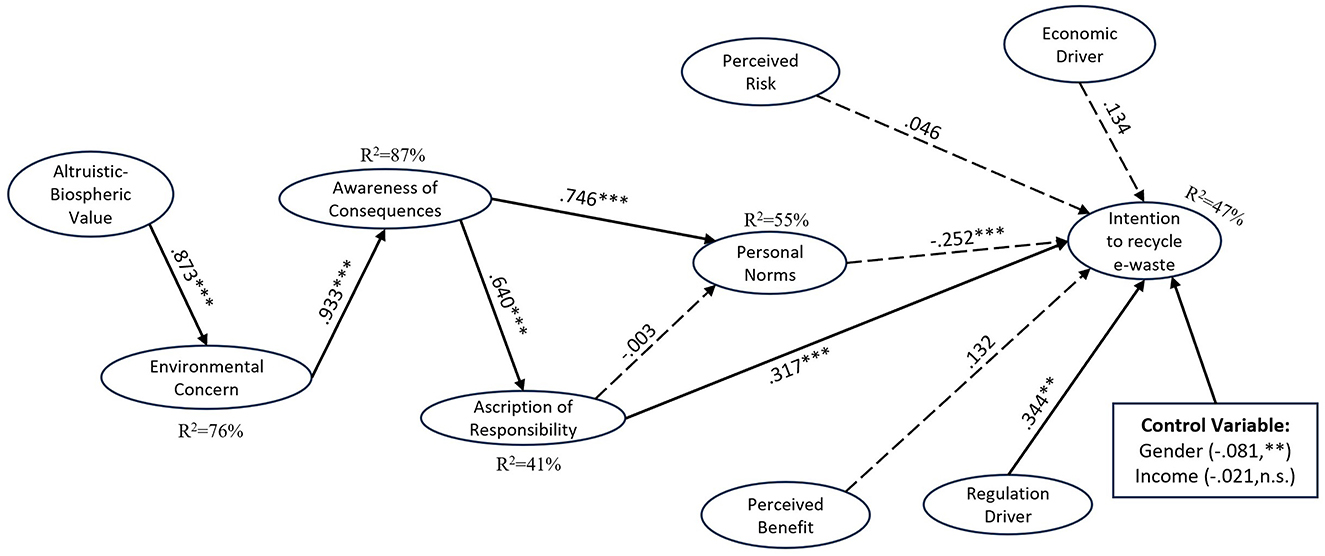

Conversely, Japan's VBN model (See Figure 3) showed that while altruistic-biospheric values positively influenced EC (p < 0.001), and EC positively affected AC (p < 0.001), the sequence broke down with AR, showing no impact on PNs (n.s.), and PNs negatively affecting recycling intentions (β = −0.253, p < 0.001). The direct effects between AC and PNs (p < 0.001) and AR and intention to recycle (p < 0.001) were significant. However, PBs and PRs were not significantly associated with recycling intentions (both indicating n.s.). Regulation positively influenced recycling intentions (p < 0.001), while economic factors did not (n.s.). These factors explained 47% of the variance in recycling intention in Japan, as indicated by the R2 = 0.47 (Figure 3). For the path coefficient estimation results, see Table 5.

Figure 3. Testing results of the research model in Japan. This figure shows the results of hypothesis testing in Japan using the SEM framework. The effect size of each construct on intentions to recycle e-waste was calculated and R-squared was also included. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s., non-significant. The figure illustrates two types of lines representing different hypothesis outcomes within the SEM framework. The solid lines signify that the hypotheses are supported, indicating a statistically significant relationship or effect within the model. The dashed lines indicate that the hypotheses are rejected, meaning the data does not provide significant support for the hypothesized relationship.

While no substantial differences were noted in Vietnam, the control variables had important impacts in Japan, with gender significantly influencing intentions to recycle e-waste, whereas income was insignificant.

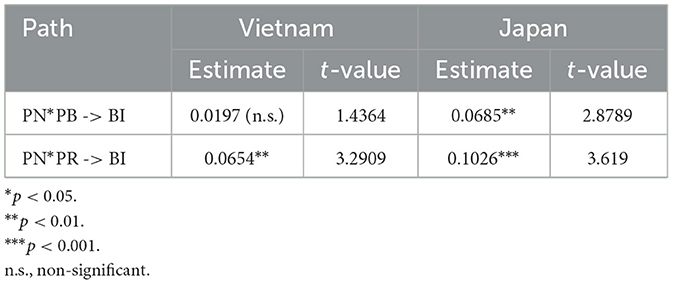

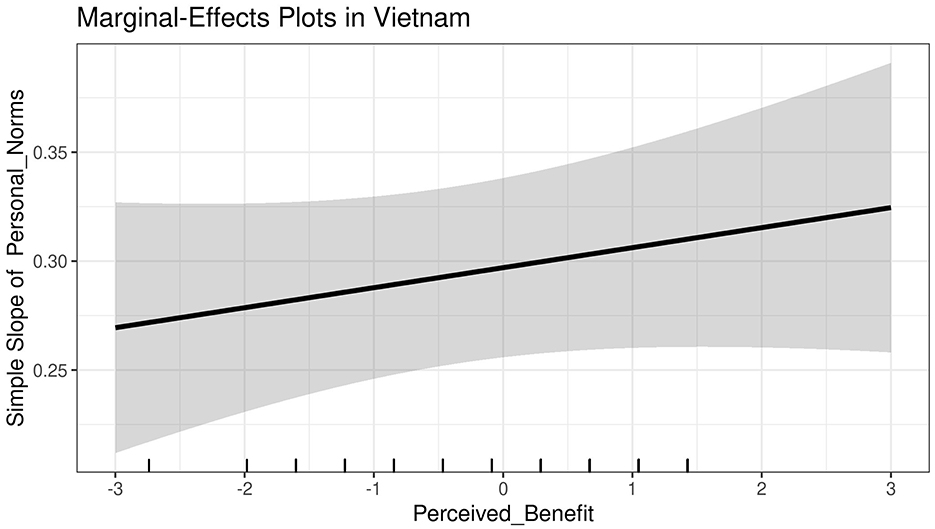

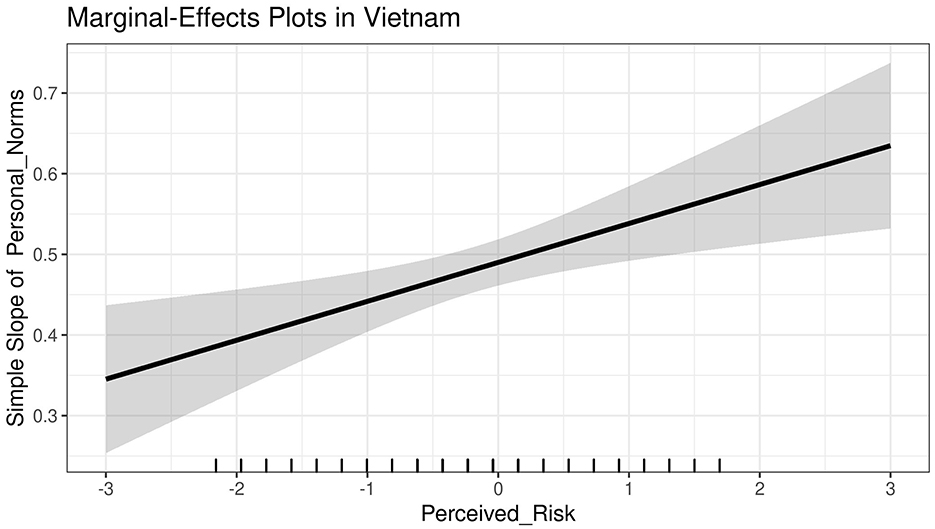

4.4.2 Moderation effect analysis

In examining the moderating effects of PBs and PRs on the relationship between personal norms (PNs) and students' intentions toward e-waste recycling, the analysis utilized the Johnson-Neyman (J-N) technique alongside marginal-effects plots (See Figures 4–7) to explore these interactions in Vietnam and Japan (McCabe et al., 2018). The results indicate that in Japan, PBs significantly enhance the association between PNs and recycling intentions, as evidenced by a significant interaction effect (See Table 6). This suggests that beyond a certain threshold of PBs, there is a meaningful increase in the predictive power of PNs on recycling intentions. Conversely, in Vietnam, the influence of PBs was found to be non-significant.

Figure 4. The graph provides a marginal effects display for the interaction effect in Vietnam, examining the relationship between PNs and the intention to recycle e-waste across various levels of PB.

Figure 5. The graph provides a marginal effects display for the interaction effect in Vietnam, examining the relationship between PNs and the intention to recycle e-waste across various levels of PR.

Figure 6. The graph provides a marginal effects display for the interaction effect in Japan, examining the relationship between PNs and the intention to recycle e-waste across various levels of PB.

Figure 7. The graph provides a marginal effects display for the interaction effect in Japan, examining the relationship between PNs and the intention to recycle e-waste across various levels of PR.

Furthermore, PRs displayed a significant positive moderating effect on the PN-intention relationship in both countries. In Vietnam, this effect was significant (Estimate = 0.0654, p < 0.01), while in Japan, it was even more pronounced (Estimate = 0.1026, p < 0.001). The J-N technique identified regions of significance for PRs, demonstrating that as PRs increase, so does the strength of the relationship between PNs and intentions across both cultural contexts. This finding challenges the initial hypothesis (H11) by indicating that higher PRs actually bolster the motivational role of PNs in promoting e-waste recycling intentions.

4.5 Measurement invariance testing

To ensure the validity of the cross-cultural comparison, a multi-group analysis was conducted to test for measurement invariance between the Vietnamese and Japanese samples (Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). This procedure assesses whether the measurement model is understood and interpreted equivalently across both groups. After initial tests revealed significant non-invariance, three problematic items were removed: AC1, EC5, and RD3. This resulted in a final, cross-culturally stable measurement model.

First, a baseline configural model (Model 1), which specifies the same factor structure for both groups, was tested on this revised set of items. This model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 8,979.441, df = 1,968, CFI = 0.929, RMSEA = 0.038), establishing a valid baseline for invariance testing.

Next, we tested for metric invariance (Model 2) by constraining all factor loadings in the revised model to be equal across the two groups. A comparison of this more constrained model (χ2 = 9,882.447, df = 2,015, CFI = 0.921, RMSEA = 0.040) against Model 1 was performed. The chi-square difference test was statistically significant (Δχ2(47) = 903.006, p < 0.001). However, with large sample sizes, the chi-square difference test is often overly sensitive to trivial, non-substantive differences between groups (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002).

Therefore, we followed the recommended best practice of evaluating the change in alternative fit indices. The change CFI was 0.008, and the change in RMSEA was 0.002, which were less than the recommended threshold of 0.01 and 0.015, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that practical metric invariance is supported (Cheung and Rensvold, 2002; Putnick and Bornstein, 2016). This finding demonstrates strong evidence that the factor loadings are equivalent across the Vietnamese and Japanese samples. In other words, the constructs have the same meaning for students in both countries, allowing for a valid and meaningful comparison of the structural path coefficient (Leitgöb et al., 2023).

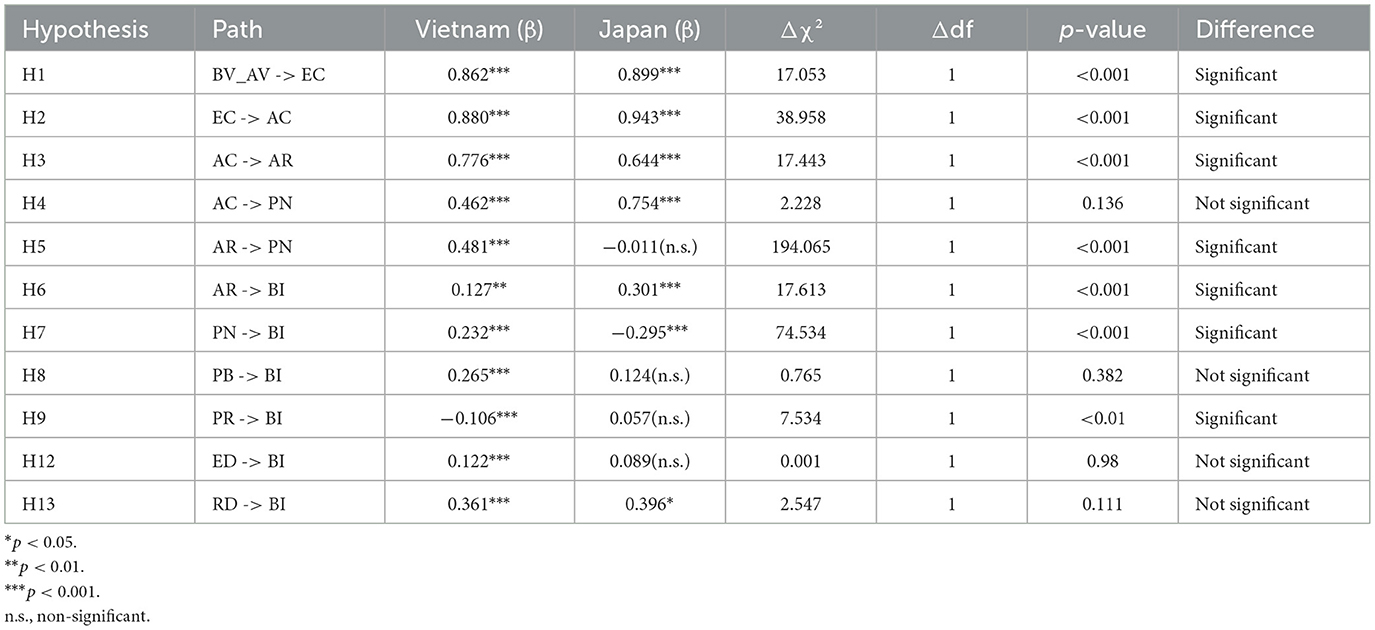

4.6 Multi-group analysis

Following the confirmation of measurement invariance across the Vietnamese and Japanese samples, an MGA was conducted to formally test for significant differences in path coefficients between the two groups. In this analysis, a series of chi-square difference tests was performed to evaluate whether the relationships among key constructs were equivalent or varied across the national contexts.

The results (see Table 7) reveal a nuanced pattern of both similarities and divergences in the psychological and contextual drivers of e-waste recycling intentions. For certain paths, including H4, H8, H12, and H13, no significant differences were observed. This indicates that these theoretical relationships are statistically invariant between Vietnamese and Japanese students.

However, several other key relationships demonstrated significant differences between groups. In particular, the initial value-belief chain (H1, H2, and H3) and the direct effects on intentions to recycle (H6 and H9) exhibited significant variation. The most substantial differences emerged within the core VBN pathway, specifically for the links from AR to PN (H5; Δχ2 = 194.065, p < 0.001) and PN to BI (H7; Δχ2 = 74.534, p < 0.001). These findings indicate that while some drivers of recycling intention are consistent across groups, the overall model operates in a structurally different manner in each national context.

5 Discussion

This study aims to explain e-waste recycling intentions by integrating three distinct theoretical streams in a cross-cultural context. The research model combines the causal chain of the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory with key predictors from Valence Theory (VT) and the Reverse Logistics (RL) concept.

This study found that the model fit between the two national samples was different due to the respondents' characteristics. While the model demonstrated a good fit in the homogeneous Vietnamese sample, the fit for the Japanese data was marginal, with NFI, TLI, and CFI values falling below the conventional 0.90 threshold. A plausible explanation for this weaker fit lies in the inherent heterogeneity of the Japanese sample. Our data for Japan were collected from a nationwide, cross-disciplinary student population. This diversity likely introduces significant unobserved variance; for instance, students from different academic fields may weigh the adversity of e-waste issues differently (Fytopoulou et al., 2023), and regional variations in recycling infrastructure could influence their attitudes and intentions (He et al., 2011). This diversity might have added complexity and variance that the current model cannot fully capture, thus reducing the overall model fit. This suggests the need to interpret the results cautiously in Japan.

5.1 Impacts of VBN

The findings show that altruistic-biospheric values significantly influence ECs in both countries, indicating that Vietnamese and Japanese students who emphasize the environment's and others' well-being while valuing ecological sustainability are more likely to develop concerns that align with environmental protection. Additionally, ECs were found to be positively associated with AC. This indicates that, as students become more concerned about environmental issues, they tend to become more aware of the consequences of their actions. However, the MGA revealed that the strength of this relationship was significantly greater in Japan. This can be attributed to the impact of environmental education between the two nations. While Japan has a more comprehensive and participatory program for the younger generation to connect with nature (Kodama, 2017), Vietnam is struggling with vague and a lack of integration policy (Pham, 2023). The transition from AC to AR was significant in both countries, underscoring the role of awareness in fostering a sense of responsibility toward the environmental issues around them. This effect was stronger in Vietnam. Despite the development of environmental policies in recent years, Vietnam is facing challenges in effective implementation, which leaves several environmental problems visible and pressing (Do and Ta, 2023). In such an environment, students may feel personally responsible for contributing to solutions, as institutional responses may be perceived as insufficient. A key difference emerges regarding the impact of AR on PNs, confirmed as highly significant by the MGA. While this relationship was positive and significant in Vietnam, it was not significant in Japan. A plausible explanation for the non-significant relationship between ascription of responsibility (AR) and personal norms (PN) in Japan lies in its unique socio-technical context. Japan's recycling system is one of the world's most advanced and highly regulated, framing recycling as a formal civic duty governed by strict rules (Mekonnen and Tokai, 2020). This systemic structure is powerfully reinforced by a cultural emphasis on social compliance (Kitamura, 2000) and interdependence, where individuals are motivated to align with the behavior of others (Markus and Kitayama, 1991).

Consequently, the responsibility for e-waste management is effectively externalized from the individual to the system itself (Pellizzoni, 2004; Fahlquist, 2009). Therefore, the primary task for a student is, perhaps, to correctly comply with established procedures. This focus on rule-following and social conformity diminishes the role of an internal moral compass, rendering the psychological link AR to PN weak or redundant. In this context, the key driver for action might be social compliance, not individual moral activation. This finding indicates that in Japan, the influence of personal responsibility is likely overridden by the dominant roles of social norms and trust in the systemic infrastructure, and would require further investigation. Finally, PNs positively influenced students' e-waste recycling intentions in Vietnam. This result reveals that (i) Vietnamese university students may internalize a robust sense of personal accountability toward environmental issues related to e-waste, which could directly influence their intentions to engage in a prosocial manner. Nguyen et al. (2019) reported that social pressure is a significant indicator of Vietnamese people's intentions to recycle e-waste; thus, (ii) students' moral obligations seem to align with this social norm in Vietnam. These findings indicate that Vietnam's model aligns with the initial mediating structure of VBN theory (Stern et al., 1999; Stern, 2000) and previous studies (Dong et al., 2024).

Conversely, an unexpected result was found in Japan: PNs negatively affected recycling intentions. A possible explanation is that Japan is an interdependent cultural nation in which people are highly aware of the expectations of others and the community (Ando et al., 2007). Hence, (i) PNs may not be a powerful indicator of the intention to recycle compared to subjective norms in Japan. Furthermore, AR did not influence PNs. Therefore, (ii) it is possible that Japanese students lack a sense of responsibility regarding e-waste recycling and environmental issues related to e-waste, which could hinder the development of personal obligations toward e-waste recycling. This suggests that feelings of responsibility are crucial in enhancing the sense of moral duty to act prosocially (De Groot and Steg, 2009). (iii) Students' moral obligations toward e-waste recycling may conflict with prevailing social norms in Japan, where the emphasis on e-waste recycling remains limited (Dhir et al., 2021). This contradicts De Groot et al. (2021) findings, indicating that people with stronger PNs are swayed less by normative messages about pro-environmental behavior than those with weaker PNs. However, it is noteworthy that previous studies were conducted with Western samples (i.e., Dutch), with a much stronger independent culture that emphasizes uniqueness to others and self-boundaries (Ando et al., 2007). Therefore, further investigations are crucial for understanding how PNs are performed in interdependent nations such as Japan and what factors could possibly influence the intention to recycle e-waste there.

Both countries exhibited notable direct effects from AC to PNs and AR on students' intentions to recycle e-waste. This aligns with He and Zhan's (2018) findings, suggesting that (i) improving AC can lead to a higher moral obligation toward prosocial behavior, and (ii) AC can be a crucial indicator for measuring PNs alongside AR. Additionally, the results confirmed the direct effects between ascribed responsibility and e-waste recycling intentions, demonstrating the significance of an individual's sense of accountability toward environmental conservation via recycling e-waste. This aligns with the findings of Dong et al. (2024).

5.2 Impacts of VT and RL

PB and PR were significant predictors of recycling intention in Vietnam but were insignificant in Japan. These findings are consistent with prior studies (Dhir et al., 2021; Nadarajan et al., 2023), indicating that (i) students may hold favorable perceptions toward e-waste recycling and perceive personal benefits and (ii) the positive environmental and individual outcomes from recycling e-waste can foster robust intentions to recycle among Vietnamese students. Additionally, aligning with previous studies, PRs negatively impacted students' intentions to recycle e-waste (Wang and Hazen, 2016; Kaur et al., 2020). This might be primarily owing to the lack of formal recycling institutions in Thai Nguyen, the survey area, which led to students' perceived inconvenience and increased time consumption. Furthermore, cybersecurity and personal privacy theft remain significant issues in Vietnam (Mai and Tick, 2021), which might trigger students' PRs. This study underscores the complex role of PR in shaping individuals' intentions to participate in e-waste recycling. In Vietnam, PR significantly influenced recycling intentions, whereas in Japan, it did not, reflecting variability in its impact across different cultural contexts. This variability is consistent with the findings of Puzzo and Prati (2024), which revealed heterogeneity in PR's effect on behavioral intentions in their meta-analysis. Despite the challenges in consistently detecting the influence of PR, particularly in e-waste recycling, as Puzzo and Prati (2024) suggested, people tend to consider benefits more than risks. The findings highlight the importance of continued research to uncover the conditions under which PR affects recycling behaviors. Such insights are crucial for developing effective intervention strategies to promote sustainable e-waste management.

Conversely, the findings for Japan contradict those of Dhir et al. (2021), indicating that Japanese consumers are inclined to recycle e-waste if they perceive that doing so brings benefits. This could be because Japanese students might not usually handle discarded devices directly. This was discussed during our qualitative interviews, during which the students responded that they left obsolescent devices for their parents to discard. Consequently, they may not feel self-satisfaction when recycling e-waste, which serves as an important indicator of PB (Gilal et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2024). Therefore, they may not perceive recycling as beneficial. Moreover, Japanese students did not perceive the risks of e-waste recycling, as supported by Dhir et al. (2021) and Nadarajan et al. (2023), underscoring the need for further investigation. According to Dhir et al. (2021), Japanese consumers do not perceive e-waste recycling as a risk. A plausible rationale for this is that Japan has successfully implemented a robust framework for e-waste recycling, instilling a sense of trust and peace of mind in its citizens.

Regulatory drivers demonstrated a significant positive relationship with recycling intentions in both countries. This aligns with the findings of Nguyen et al. (2019) and Sari et al. (2021), demonstrating the vital role of regulations and laws in students' intentions to recycle e-waste. Unlike Japan, where laws on e-waste recycling have been enacted since the early 2000s, Vietnam has not yet established official laws in this context. Therefore, it is crucial to establish laws that clearly outline residents' obligations regarding e-waste recycling. Economic drivers were significant in Vietnam, indicating that compensation and incentives for recycling e-waste can positively increase students' intentions to recycle e-waste. This aligns with the findings of Helinski et al. (2024), who suggested that financial incentives are a more significant indicator motivating people to return end-of-life cosmetic products than sustainable incentives or no incentives at all. This result also reflects why Vietnamese students tend to sell more obsolescent devices to second-hand shops, as they can thus obtain more monetary benefits, as shown in our descriptive results. In contrast, economic drivers were statistically insignificant in Japan, implying that Japanese students do not consider economic incentives to be essential for recycling e-waste. A plausible explanation may be that (i) e-waste recycling is mandated in Japan; thus, students are likely to follow regulations even without financial incentives. Moreover, Japanese culture is highly long-term oriented and values perseverance (Hofstede et al., 2010), suggesting that (ii) individuals in these societies are more inclined to endorse policies aimed at a superior future, even if it entails personal sacrifices such as the cost associated with e-waste recycling.

The findings revealed that PBs positively moderated the association between PNs and e-waste recycling intentions in Japan, but not in Vietnam. This suggests that if Japanese students with higher personal standards perceive substantial advantages, they are more inclined to recycle e-waste. Perceived disadvantages positively moderate the correlation between moral obligations and e-waste recycling intentions in both countries. This contradicts the findings of Pangaribuan et al. (2022) and De Groot and Steg (2010), indicating that a higher PR might weaken the impact of personal obligations on the inclination to engage in actions related to voluntourism and nuclear energy. One potential justification for this phenomenon is the prevailing moral responsibility felt by students in both nations to actively participate in preserving the environment, which may surpass their concerns about the potential risks.

5.3 Theoretical implications

This study integrates VT, the VBN model, and regulatory and financial contexts from RL to establish a comprehensive model for gauging recycling intentions. Additionally, it emphasizes the moderating impact of PBs and PRs on the relationship between PNs and recycling intentions, enhancing the theoretical framework's complexity and predictive capability. It also contributes to comprehending how AC influences PNs and how AR impacts pro-environmental intentions, thereby supporting Schwartz's (1977) position and addressing gaps in existing research on the effect of responsibility on behavior.

Another key theoretical contribution of this study is the finding that perceived risk positively moderates the relationship between personal norms and behavioral intention. Our results indicate that when recycling is perceived as costly or difficult, a strong personal norm may provide the necessary “moral conviction” to overcome these barriers (Skitka et al., 2005), leading to a more robust and resilient behavioral intention. This highlights that the strength of a personal norm might become most critical when self-interested concerns are present, adding empirical evidence to support theories on moral identity and its role in motivating prosocial behavior (Aquino and Americus, 2002; Skitka et al., 2005). Thus, this result provides a potential path for future study to consider moral conviction as a factor for pro-environmental behavior.

This study involved the first empirical application of the E-PVQ to assess altruistic and biospheric values in the context of e-waste recycling. With strong factor loading estimates from the CFA, the findings suggest that the E-PVQ could serve as a reliable tool for future research on pro-environmental behaviors.

Finally, the robustness and applicability of the model across two culturally distinct countries where students' values are in harmony with pro-environmental behavior encourage further investigation into factors that amplify normative influence.

5.4 Practical implications

Considering that regulation drivers are significant positive predictors of recycling intention, regulatory frameworks with clear instructions to address e-waste issues need to be implemented alongside promoting student involvement in e-waste recycling in Vietnam. Establishing and enforcing laws and regulations that outline the responsibilities of relevant departments (e.g., Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment) and stakeholders (e.g., manufacturers, retailers, and consumers) are essential for developing an effective e-waste recycling and administrative system. For example, consumers must pass over discarded devices and pay recycling fees and manufacturers should be responsible for constructing recycling facilities. They can offer assurances such as information cleaning services, which help delete information stored in old devices before recycling to ensure students do not perceive risk. Furthermore, manufacturers should collaborate with universities to establish collection spots within or near the university to reduce the inconvenience of recycling, which has been shown to significantly impact recycling intentions (Wang et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2019). Leading retailers such as NTT Docomo and Yodobashi in Japan or FPT in Vietnam should be role models in implementing schemes to motivate young consumers to bring back their products for secure e-waste treatment because they are the main distributors of these devices. These schemes could include offering discount coupons, organizing lucky draws, and trade-in programs, which would improve the influence of economic drivers on students' intentions to recycle e-waste. Besides financial benefits, schemes such as environmental protection souvenirs can provide recognition and enhance students' perception of the benefits of recycling.

As VBN model variables also positively influence students' recycling intentions, organizations and governments should convey knowledge and information on how recycling e-waste aligns with people's values (i.e., environment protection, facilitating others' well-being, and raising awareness about the detrimental impacts of unauthorized e-waste disposal). Finally, spreading knowledge and advertising activates students' moral norms and enhances their intention to recycle e-waste. Related policies must be implemented in collaboration with universities as they are closely connected with students.

6 Limitations and future work

Although the study identified five focal target electronic devices, each item was not investigated separately. To overcome this generalization of e-waste items, future research should explore e-waste disposal behaviors based on specific items, employing methods such as discrete choice experiment. This approach would present students with realistic scenarios involving different product types, conditions, and collection or disposal attributes (Hoyos, 2010), which could help stakeholders design tailored e-waste collection interventions that provide positive experiences for people.

This study measured altruistic and biospheric values as variables that significantly affect ECs. Separating these two values and including egoistic values in future studies may provide further insights regarding model development and related findings (De Groot and Steg, 2008; Rahman and Reynolds, 2016). We utilized behavioral intentions to examine students' e-waste recycling behavior, which is a strong predictor of actual behavior, but may not fully represent it. Hence, future research could focus on investigating recycling behavior, by adopting the space repetition method in which they first measure students' recycling intentions at Time 1, and follow up several months later at Time 2 to measure the actual disposal behaviors during that period. This may provide crucial insights into what factors motivate or prevent students from recycling.

In Japan, the model failed to meet the traditional fit indices cutoffs proposed by previous studies (Hu and Bentler, 1999). This implies that other factors that contribute to e-waste recycling intentions in Japan should be explored. Thus, future research can further develop and modify the model for better model fit and capture the recycling intentions holistically. In addition, future research could adopt latent class analysis to identify unobserved heterogeneity, which might provide a more nuanced understanding of how different segments of the population form their recycling intentions.

This study employed a cross-sectional online questionnaire, which relied exclusively on self-reported data. This method is susceptible to potential normative response bias, where students may have over-reported their pro-environmental intentions and beliefs to align with socially desirable norms, rather than reflecting their true attitudes or behaviors. Additionally, an inconsistent survey method was adopted. In Vietnam, we adopted convenience stratified sampling at the Thai Nguyen University of Medicine and Pharmacy from the General Medicine program, whereas in Japan, we adopted stratified sampling through a survey company to collect student data nationwide. Therefore, the sample from Vietnam may have been homogeneous, with students sharing similar backgrounds and beliefs. Thus, the results are limited to being generalized to the broader population of university students nationally. Finally, considering cultural differences, the study's findings might have generalizability issues in Western countries. However, considering the model's good fit, it can be adopted in research across countries with different economic statuses and cultural backgrounds using a consistent sampling method.

7 Conclusions

This study developed an integrated model combining the Value-Belief-Norm theory, Valence Theory, and Reverse Logistics concepts to provide a comprehensive, cross-cultural investigation of students' intentions regarding e-waste recycling. Our findings demonstrate that while recycling inclinations are shaped by factors, including personal norms, regulation, economic drivers, responsibility, and perceived risks and benefits, their specific impact varies significantly between Vietnam and Japan. The multi-group analysis confirmed that while students in both nations share certain perspectives, the key drivers influencing their final intentions differ due to distinct cultural, regulatory, and economic contexts. Ultimately, this research offers a nuanced understanding of e-waste recycling intentions among university students in Vietnam and Japan.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DDT: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software. RS: Project administration, Validation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. A research support fund from the Ritsumeikan University Policy Science Association was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeel, S., Nayab, A., Qureshi, M. U., and Channa, K. A. (2023). University students' awareness of e-waste and its disposal practices in Pakistan: a construction of the conceptual framework. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 25, 2457–2470. doi: 10.1007/s10163-023-01707-7

Akdogan, M. S., and Coşkun, A. (2012). Drivers of reverse logistics activities: an empirical investigation. Procedia 58, 1640–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1130

Ando, K., Ohnuma, S., and Chang, E. C. (2007). Comparing normative influences as determinants of environmentally conscious behaviours between the USA and Japan. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 10, 171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00223.x

Aquino, K., and Americus, R. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 1423–1440. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423

Borthakur, A., and Govind, M. (2018). Public understandings of e-waste and its disposal in urban India: from a review towards a conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 1053–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.218

Bouman, T., Steg, L., and Kiers, H. A. L. (2018). Measuring values in environmental research: a test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 9:564. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00564

Calculli, C., D'Uggento, A. M., Labarile, A., and Ribecco, N. (2021). Evaluating people's awareness about climate changes and environmental issues: a case study. J. Clean. Prod. 324:129244. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129244

Cheung, G. W., and Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Cook, R. D. (1977). Detection of influential observation in linear regression. Technometrics 19, 15–18. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1977.10489493

Cross Marketing (2024). Cross Marketing, Inc. Available online at: https://www.cross-m.co.jp/en/ (accessed January 1, 2024).

Dash, G., and Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 173:121092. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

De Groot, J. I. M., Bondy, K., and Schuitema, G. (2021). Listen to others or yourself? The role of personal norms on the effectiveness of social norm interventions to change pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 78:101688. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101688

De Groot, J. I. M., and Steg, L. (2008). Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior. Environ. Behav. 40, 330–354. doi: 10.1177/0013916506297831

De Groot, J. I. M., and Steg, L. (2009). Morality and prosocial behavior: the role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 149, 425–449. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449

De Groot, J. I. M., and Steg, L. (2010). Morality and nuclear energy: perceptions of risks and benefits, personal norms, and willingness to take action related to nuclear energy. Risk Anal. 30, 1363–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01419.x

Dhir, A., Malodia, S., Awan, U., Sakashita, M., and Kaur, P. (2021). Extended valence theory perspective on consumers' e-waste recycling intentions in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 312:127443. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127443

Do, T. N., and Ta, D. T. (2023). “Vietnam's environmental policy: a 30-year critical review,” in World Scientific Series Volume III: Environment, Sustainability, and Human Security, ed. Z. Zhu (World Scientific Publishing).

Dong, Z., He, C., Hu, T., and Jiang, T. (2024). Integrating values, ascribed responsibility and environmental concern to predict customers' intention to visit green hotels: the mediating role of personal norm. Front. Psychol. 14:1340491. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1340491

Dwivedy, M., and Mittal, R. K. (2013). Willingness of residents to participate in e-waste recycling in India. Environ. Dev. 6, 48–68. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2013.03.001

Echegaray, F., and Hansstein, F. V. (2017). Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: the case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 142, 180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.064

Fahlquist, J. N. (2009). Moral responsibility for environmental problems - individual or institutional? J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 22, 109–124. doi: 10.1007/s10806-008-9134-5

Fornara, F., Pattitoni, P., Mura, M., and Strazzera, E. (2016). Predicting intention to improve household energy efficiency: the role of value-belief-norm theory, normative and informational influence, and specific attitude. J. Environ. Psychol. 45, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.11.001

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Fytopoulou, E., Karasmanaki, E., Tampakis, S., and Tsantopoulos, G. (2023). Effects of curriculum on environmental attitudes: a comparative analysis of environmental and non-environmental disciplines. Educ. Sci. 13:554. doi: 10.3390/educsci13060554

Gilal, F. G., Zhang, J., Gilal, N. G., and Gilal, R. G. (2019). Linking self-determined needs and word of mouth to consumer e-waste disposal behaviour: a test of basic psychological needs theory. J. Consum. Behav. 18, 12–24. doi: 10.1002/cb.1744

Hai, H. T., Hung, H. V., and Quang, N. D. (2017). An overview of electronic waste recycling in Vietnam. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 19, 536–544. doi: 10.1007/s10163-015-0448-x

Hair, J. F. Jr, Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Harland, P., Staats, H., and Wilke, H. A. M. (2007). Situational and personality factors as direct or personal norm mediated predictors of pro-environmental behavior: questions derived from norm-activation theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 323–334. doi: 10.1080/01973530701665058

He, X., Hong, T., Liu, L., and Tiefenbacher, J. (2011). A comparative study of environmental knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among university students in China. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 20, 91–104. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2011.564783

He, X., and Zhan, W. (2018). How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 3546–3556. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.05.088

He, X., Zhan, W., and Hu, Y. (2018). Consumer purchase intention of electric vehicles in China: the roles of perception and personality. J. Clean. Prod. 204, 1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.260

Hein, N. (2022). Factors influencing the purchase intention for recycled products: integrating perceived risk into value-belief-norm theory. Sustainability 14:3877. doi: 10.3390/su14073877

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Peng, K., and Greenholtz, J. (2002). What's wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: the reference-group effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 903–918. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.903