- Sustainable Manufacturing Systems Centre, Cranfield University, Cranfield, United Kingdom

The fashion industry faces significant challenges due to its linear systems and environmental impact. As sustainability gains priority among consumers, especially Generations Y and Z, the industry is urged to transition towards a circular economy. Despite this, the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’ persists, indicating minimal impact on consumer behaviour. This study explores factors influencing consumer behaviour towards circular fashion, focusing on Generations Y and Z. Nine hypotheses were developed, exploring relationships among environmental awareness, circular fashion awareness, willingness to change, willingness to pay a premium, and circular behaviour. Online surveys yielded 408 responses from participants from developing and developed countries. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used for hypothesis testing. Results show consumer behaviour is influenced by environmental awareness and circular fashion awareness, and willingness to change. Additionally, purchasing decisions are driven by product quality and durability. The findings assist fashion businesses in aligning strategies with consumer perception among Generations Y and Z.

1 Introduction

The fashion industry is not only about aesthetics and clothing; it plays a significant role in shaping the global economy, culture, and society. The fashion industry employed a substantial portion of the worldwide workforce, exceeding 300 million employees in 2017 (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017), and it has been consistently expanding ever since. Statista estimates that by the end of 2023, the world’s apparel market will reach $1.7 trillion, up from approximately $1.5 trillion in 2022 (Smith, 2023). Hence, the fashion industry contributes over 2% to the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Papamichael et al., 2023). Its extensive scale positions it among the most resource-demanding and environmentally impactful industries.

A primary issue in the fashion industry is its enduring adoption of the linear model, following the ‘take-make-dispose’ approach (Ki et al., 2021; Abdelmeguid et al., 2022). Niinimäki et al. (2020) estimate that the fashion industry accounts for 20% or so of global water waste (equivalent to 190,000 tonnes annually) due to the dyeing and finishing processes of textiles. Moreover, it contributes 8–10% of the world’s carbon emissions, amounting to 4–5 billion tonnes per year, and generates a substantial 92 million tonnes of waste annually. Moreover, about 73% of total textiles are subjected to incineration, with a mere 12% repurposed to create new products or recycled (Camacho-Otero et al., 2019). However, as much as 95% of textile waste has the potential to be reintegrated into circulation through strategies such as reuse, repair, or recycling (Henninger et al., 2019). This is in addition to the presence of the fast fashion phenomenon and its continuous growth among the industry players, which is associated with rapid shifts in trends and styles, an increased frequency of collections per year, and a decline in prices (Vehmas et al., 2018). This encourages consumers to purchase clothing items more frequently and keep them for shorter periods, contributing to the culture of ‘buy-and-dispose’ (Musova et al., 2021). Consequently, over the last 20 years, the industry has doubled production, yet clothing usage has dropped by at least 40% (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).

Fast fashion, coupled with rising living standards, has also led to significant increases in clothing consumption, particularly in developed countries (Cruz and Rosado da Cruz, 2023). This rise has contributed to a substantial increase in textile waste across developed countries (Piippo et al., 2022). However, the absence of regulatory measures on textiles, coupled with a domestic waste crisis, results in large-scale exportation of used apparel and textile waste to developing countries (Piller, 2023). This practice not only undermines local production in the fashion industry but also relocates environmental problems to other regions. Moreover, fast fashion shortens the product lifespan, leading to a quick transition from usage to waste. The lifespan of three everyday clothing items (T-shirts, woven pants, and knit collared shirts) across six countries (UK, USA, Italy, Germany, China, and Japan) typically ranges from 3.1 to 3.5 years per item, displaying notable variations among nations (Daystar et al., 2019). These figures may fluctuate based on clothing types or cultural context (Piippo et al., 2022). Thus, the fashion industry contributes significantly to global waste production at an increasing rate.

The significant environmental concerns associated with fast fashion gave rise to the emphasis on comprehending and advocating for sustainable practices. As a result, the circular economy is emerging as a sustainable alternative to traditional linear economies (de Aguiar Hugo et al., 2023). A circular economy is defined by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2012) as ‘the principles of designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems.’ Moreover, the circular economy implements practical measures in pursuit of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations (UN), with particular emphasis on SDG 12 ‘Responsible Consumption and Production’ (Vehmas et al., 2018; Gabriel and Luque, 2020). ‘Circular Fashion’ refers to integrating a circular economy into the fashion industry. Based on Niinimäki (2017), it is intended that this approach will assist in establishing closed-loop systems, sustaining the clothing items’ value for as long as possible, and extending the lifespan of these items.

Circular economy and circular fashion concepts share interconnected principles. However, in the fashion industry, a circular economy comprises three main principles: (1) reduce (i.e., using fewer natural and non-renewable resources and energy resources and energy, and decreasing the waste produced by the industry and consumers waste through actions like owning fewer fashion items), (2) reuse (i.e., prolonging the effective use of a fashion item either by its owner or another individual while it remains in good condition), and (3) recycle (i.e., the process involves obtaining materials of either the same or lower quality) (Morseletto, 2020; Papamichael et al., 2023). Circular economy principles should be incorporated into the waste hierarchy to align with the 4Rs framework—reduce, reuse, recycle, and recover—indicating their specific ranking or order (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Potting et al., 2017). Most of the circular economy literature emphasises recycling while overlooking the more desirable and highest-priority elements of the waste hierarchy of reduce and reuse, necessary for a successful circular system (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Hence, repair is also an essential aspect of circular fashion since it sustains the prioritised waste hierarchy elements of reduce and reuse (McQueen et al., 2022).

The growing environmental consciousness and sustainability interest among consumers, especially among younger generations, have prompted the fashion industry to adopt a circular economy approach (Liu et al., 2023). However, there is still minimal impact on actual consumer demand and consumer behaviour, referred to as the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’ (Auger and Devinney, 2007; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Therefore, fashion businesses and brands must understand the factors influencing consumer behaviour and reassess their strategies to address the current gap. (Musova et al., 2021; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Previous research highlights the relationship between environmental awareness and purchasing intentions (Park and Lin, 2020), as well as recognises the attitude-behaviour gap. It has also been shown that younger generations are more drawn to and more likely to engage with circular practices (Gazzola et al., 2020; Lin and Chen, 2022; Liu et al., 2023). However, limited research investigates the factors that drive consumers’ behaviour towards circularity.

This study aims to explore the factors influencing consumers’ behaviour towards circular fashion, explicitly focusing on Generation Y, also known as Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996), and Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012) (Dimock, 2019). These specific cohorts were selected due to their higher engagement levels with sustainability issues, significant influence on market trends, and their pivotal role as early adopters of innovative practices (Gazzola et al., 2020). These generational cohorts, often characterised by their enhanced environmental consciousness and tech-minded nature, hold significant influence over market trends (Lin and Chen, 2022). Although including older generations could enhance generalisability, focusing on Millennials and Generation Z offers targeted insights due to their distinct consumer behaviours and strategic importance for future sustainability transitions. Understanding their attitudes and behaviours towards circular fashion is vital in fostering sustainable and circular practices, as well as achieving broader SDGs. To achieve this aim, the relationships between key variables, including environmental awareness, circular fashion awareness, consumers’ circular behaviour, willingness to pay a premium, and willingness to change, are explored within the context of circular fashion. Therefore, to gain a deeper understanding of the consumer behaviour towards circular fashion, the study addresses the following research questions:

1. What are the key factors shaping consumer behaviour towards circular fashion, particularly among Generations Y and Z?

2. What factors most significantly influence purchasing decisions for fashion products among Generations Y and Z?

By exploring these connections, the complexity surrounding consumer behaviour towards the adoption of circular fashion practices will be better understood. Importantly, our research aligns with several SDGs, with notable contributions to SDG 9 ‘Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure’ and SDG 13 ‘Climate Action’. Most significantly, our focus on ‘Sustainable Production and Consumption’ directly corresponds to the objectives outlined in SDG 12.

The following sections of this study are structured to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of our research process: (1) Introduction provides a context for the study, (2) Literature Review demonstrates existing research on consumer behaviour towards circular fashion, (3) Hypotheses development to explore the factors that impact consumer behaviour within the realm of circular fashion. These hypotheses will also be demonstrated in a conceptual framework that serves as the foundation for empirical investigation and in-depth analysis, (4) Methodology outlines our approach using surveys for data collection and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) for testing the hypotheses formulated, (5) Results and Discussion section demonstrates our findings, the developed model, and the practical implications drawn from our study. Finally, (6) Conclusion provides key insights, as well as highlights the limitations of the study and proposes recommendations for future research. Through this structured exploration, the study aims to contribute valuable knowledge to fashion businesses and brands surrounding consumer behaviour towards circular fashion practices and the factors affecting their behaviour.

2 Literature review

Consumers are identified as the main actors in facilitating the shift towards circular fashion (Zhang, 2021). Thus, consumers’ awareness is perceived as the first step and main driver to shifting towards circular fashion and applying its principles (Aramendia-Muneta et al., 2022). In this context, environmental awareness, reflecting consumers’ understanding of ecological issues and the negative environmental impact of their consumption, plays a critical role in shaping their purchasing and usage behaviours (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2025). However, despite growing attention to sustainability, consumers still face an attitude-behaviour gap in circularity (Abdelmeguid et al., 2023). Research suggests that bridging this gap involves not only fostering environmental concern but also increasing circular fashion awareness, which refers to consumers’ knowledge of sustainable fashion alternatives and the core principles of the circular economy (Colucci and Vecchi, 2021; Aramendia-Muneta et al., 2022). Circular fashion awareness is considered critical for translating positive attitudes into tangible behaviours. While consumers exhibit favourable positive trends in their interests and attitudes regarding sustainability and circular fashion, a significant gap exists between these attitudes and purchasing, usage, and disposal behaviour (Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Previous research has indicated that a primary factor for the gap is a lack of consumer awareness regarding circular fashion, limiting their ability to act on their attitudes and translate them into action (Dissanayake and Weerasinghe, 2021). Therefore, fashion businesses and brands need to communicate their circular strategies to promote awareness among consumers and encourage them to adopt circular fashion practices and change their behaviours (Kumar P. et al., 2021; Abdelmeguid et al., 2023). This aligns with stakeholder theory, highlighting the mutual relationships between firms and their stakeholders (Meherishi et al., 2019). Stakeholder theory emphasises how effective communication and alignment of interests among stakeholders, such as consumers, are essential to achieving organisational goals and sustainable outcomes (Kumar Mangla et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). However, businesses must also navigate conflicting stakeholder interests, such as between price-sensitive and environmentally conscious consumers, which challenges aligning these interests towards a common goal.

Studies have highlighted that environmental knowledge shapes consumers’ purchasing and usage behaviour (Ertz et al., 2016). Therefore, consumers who have good ecological understanding and awareness of the drawbacks associated with the linear fashion system are less inclined to participate in fast fashion, as well as adopt sustainable and circular practices such as buying sustainable products, conserving energy, and recycling (Ertz et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021). Environmental awareness is also significantly positive with the consumers’ disposal behaviour of fashion products (Wai Yee et al., 2016). Conversely, there is a significant proportion of consumers who still lack a comprehensive understanding of circular fashion concepts and principles (Hugo et al., 2021).

Previous studies have shown that various variables could also impact consumers’ behaviour in a circular fashion (Auger and Devinney, 2007). For instance, some argue that behaviours are predominantly driven by personal interests and values (Lundblad and Davies, 2016), while other studies say that behaviours are driven by external factors such as product characteristics, culture, social influence, and economic context (Wiederhold et al., 2018). Recent research by Falcone and Fiorentino (2025) further emphasises the role of behavioural interventions, specifically nudging techniques, in shaping consumer behaviour towards circular practices in fashion. Their findings highlight that psychological factors, especially consumer awareness and environmental responsibility, significantly impact consumers’ engagement with circular practices. In addition, willingness to change, referring to consumers’ openness to adopting new habits and shifting away from linear consumption patterns, has been identified as an important factor contributing to engagement in sustainable behaviour (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023). Willingness to pay a premium, which reflects consumers’ readiness to spend more for circular or sustainable fashion products, has been associated with higher environmental and circular fashion awareness as well as positive attitudes towards behavioural change (D’Adamo and Lupi, 2021; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Therefore, willingness to change describes consumers’ openness to adopting new habits or modifying existing behaviours in support of circular fashion, such as buying second-hand or repairing clothes, while willingness to pay a premium captures consumers’ readiness to spend additional money for circular or sustainable fashion products (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023; D’Adamo and Lupi, 2021). These constructs are conceptually distinct, as one reflects behavioural flexibility and intent to act, and the other represents financial commitment.

Contingency theory provides a framework for understanding these variations by emphasising that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to stakeholder engagement, including consumers (Kumar A. et al., 2021). Contingency theory emphasises tailoring organisational strategies based on diverse specific contexts, which include both internal factors such as organisation culture and size, and external factors such as economic constraints, competition, market conditions, regulatory changes, and societal pressures (Chen et al., 2018; Cardoni et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2021). For instance, different consumer segments, such as Generation Y and Generation Z, are influenced by various external factors, including technology, social norms, and cultural context, which require targeted and context-specific strategies.

Previous studies show differences in behaviours between different generations of consumers regarding various decision-making processes due to having distinct backgrounds (Lin and Chen, 2022). In addition, circular behaviour encompasses consumer actions such as reducing, reusing, recycling, repairing, and choosing sustainable or second-hand fashion items (Wiederhold et al., 2018; Park and Lin, 2020; Abdelmeguid et al., 2024). Generational cohorts are groups of individuals born within similar time frames who share common historical experiences and social influences, significantly affecting their consumer behaviours and preferences (Dimock, 2019; Lin and Chen, 2022). Consumers, particularly younger generations such as Generation Y and Generation Z, are becoming more conscious of the environmental and societal impact of linear fashion practices (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau, 2020; Liu et al., 2023). Given that Generation Y is recognised as digital natives seamlessly integrating technology into their daily routines, and Generation Z has grown up with the internet, social media, and mobile technologies, this technological familiarity plays a crucial role in enhancing their awareness of environmental issues (Lin and Chen, 2022).

According to Johnstone and Lindh (2022), Generation Y is commonly considered the largest, most influential, and most fashion-conscious, making this generation the key consumer segment since a significant portion of their available income is allocated to fashion expenditures. Recent studies have demonstrated that Generation Z also shows a keen interest in circularity in fashion and exerts notable influence on the buying choices made by their families (Francis and Hoefel, 2018). Moreover, Generation Z is gaining more attention in the recent literature since the older members of this generation are entering today’s labour market, thereby having higher importance in the consumer market (Gazzola et al., 2020). Institutional theory can help explain how societal and institutional forces shape consumer attitudes and behaviours towards circular fashion. This framework, emphasising regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive pillars, explains how established rules, norms, and beliefs influence social behaviour and consumer preferences for circular fashion (Ranta et al., 2018; Bag et al., 2021b). Additionally, this theory highlights the impact of external pressures, such as shifting social norms and environmental regulations, on organisational decision-making and sustainable practices (Caldera et al., 2019; Meherishi et al., 2019).

Besides the age group, some other demographic variables influence purchasing and consumption decisions, including gender, income, educational level, and country of residence (Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Demographic variables represent measurable characteristics of populations used to segment markets and understand consumer behaviour patterns. For example, previous studies indicate that women are more likely to engage in environmentally responsible behaviour due to their higher environmental consciousness than men (Liobikienė et al., 2017; Kumar and Yadav, 2021; Musova et al., 2021). Furthermore, the country of residence influences consumers’ purchasing and consumption choices of sustainable products, not only because of the economic situation of the country but also due to cultural and legal differences (Bucic et al., 2012). Contingency theory also provides a relevant framework to understand how these demographic variables, along with external factors like societal norms and economic conditions, shape consumer decisions (Ali et al., 2021; Kumar A. et al., 2021). By recognising these factors, businesses can better tailor their strategies to different demographic segments.

When it comes to fashion, various factors influence consumers’ buying decisions. According to Berberyan et al. (2018), factors are associated with product elements such as price, quality, product design and style, product availability and accessibility, and details on ethical sourcing. On the other hand, factors are linked to consumers such as individual interests and perception, convenience, norms and habits, values, and social desirability. Consumers usually prioritise the price of a product as the initial factor influencing their purchasing decision. Therefore, if fashion products aligned with circular strategies are more expensive, it will likely affect consumers’ willingness to buy negatively, irrespective of other factors (Hina et al., 2022). The price increase is termed ‘the circular premium’, representing an additional amount above the regular price to account for the increased expenses associated with redesign or recycling procedures or the different circular principles integrated into the products (D’Adamo and Lupi, 2021). For fashion businesses, circular premium poses a dilemma, since it requires them to decide if they are prepared to accept the possibility of losing some existing customers in exchange for the chance of gaining future customers willing to invest in circular products. For instance, Generation Z is generally more price-conscious and buys second-hand fashion items instead of new or recycled products from fashion businesses or brands, allowing them to be more environmentally friendly while saving money on clothing purchases (Liu et al., 2023). Therefore, understanding consumers’ perception of circular fashion, as well as the factors that influence the consumers’ purchasing and consumption behaviour, is crucial for shaping all decisions of businesses in the fashion industry and achieving positive environmental outcomes (Vehmas et al., 2018; Wiederhold et al., 2018).

2.1 Hypotheses development

The variables included in this study, including environmental awareness, circular fashion awareness, willingness to change, willingness to pay a premium, and circular behaviour, were selected based on their demonstrated significance in prior research examining sustainable consumption and circular fashion practices. Environmental awareness has consistently been linked to sustainable behaviour and intentions (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2025). Circular fashion awareness is increasingly recognised as a driver for engaging in circular practices economy (Colucci and Vecchi, 2021; Aramendia-Muneta et al., 2022). Willingness to change and willingness to pay a premium, although related, represent different aspects of consumer engagement. Willingness to change reflects a consumer’s openness to adopting new behaviours (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023), whereas willingness to pay a premium highlights the extent of their financial commitment to sustainability (D’Adamo and Lupi, 2021; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Finally, circular behaviour represents the actual adoption of practices such as reducing, reusing, and recycling (Wiederhold et al., 2018; Park and Lin, 2020; Abdelmeguid et al., 2024). Together, these variables provide a comprehensive framework for analysing how awareness and willingness translate into action within the context of circular fashion. The selection of these variables is grounded in stakeholder theory, contingency theory, and institutional theory, which highlight the importance of understanding the factors driving consumer behaviour and the contextual variables that shape sustainable fashion choices.

This section establishes the underlying hypotheses for this study. These hypotheses are developed through a comprehensive literature review and relevant research findings. They serve as the foundational framework for investigating the intricate relationships between environmental awareness, circular fashion awareness, behaviour, willingness to pay a premium, and willingness to change behaviour within the context of circular fashion.

Numerous studies have highlighted a growing global concern for environmental issues and a parallel increase in consumer interest in sustainable and circular practices, particularly in the context of fashion consumption (Kumar and Yadav, 2021; Musova et al., 2021; de Aguiar Hugo et al., 2023). These findings suggest a possible relationship between individuals’ environmental awareness and their level of consciousness regarding circular fashion practices. As consumers grow increasingly conscious of the ecological consequences of their decisions, it is suggested that their awareness extends to the circular fashion paradigm, encompassing practices such as reducing, reusing, repairing, and recycling. Therefore, the following hypothesis has been developed:

H1: Environmental awareness influences consumers’ circular fashion awareness.

Existing literature consistently highlighted the rising global consciousness regarding environmental issues and the shift in consumer preferences towards sustainable practices (Ertz et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2023). These findings suggest a possible link between individuals’ environmental awareness and their engagement in circularity practices such as reducing, reusing, repairing, and recycling, as well as adopting sustainable consumption patterns (Ertz et al., 2016; Wai Yee et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021). Thus, suggesting that an increased environmental consciousness can potentially drive consumers towards more circular and eco-friendly behaviours in various aspects. Based on these findings, the following hypothesis has been formulated:

H2: Environmental awareness influences consumers’ circular behaviour.

Studies consistently highlight the influence of awareness regarding circular fashion in shaping consumer attitudes and behaviours (Aramendia-Muneta et al., 2022). These findings suggest a logical link between the level of circular fashion awareness among consumers and the adoption of circular practices in their purchasing, usage, and disposal behaviour patterns (Dissanayake and Weerasinghe, 2021; Kumar P. et al., 2021). This lies in the understanding that individuals who are knowledgeable about the circular economy and its practices may actively seek out sustainable fashion alternatives, leading to behaviours such as repairing, recycling, and favouring second-hand options (Abdelmeguid et al., 2023). By addressing the environmental impact of fashion choices, it is argued that consumers can play a meaningful role in adopting a circular economy. In this context, a hypothesis has been constructed.

H3: Circular fashion Awareness influences consumer Circular behaviour.

Building on the foundation of suggesting that consumers with enhanced environmental awareness are inclined towards sustainable choices (Ertz et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021), it is recommended that those consumers are likely to translate their commitment into financial support for circular fashion items, even if it involves paying a premium. This connection is reinforced by studies indicating that consumers with strong environmental consciousness may view the additional cost as an investment in promoting sustainable practices (Angel et al., 2018). However, it is essential to acknowledge the challenging nature of consumer responses to price premiums. Studies suggest that despite a positive attitude towards sustainability, price is a major influential factor for consumers, and a significant premium may risk losing existing customers (D’adamo and Lupi, 2021; Abdelmeguid et al., 2022; Hina et al., 2022). Our research aspires to empirically validate these relationships and contribute to an understanding of the complex link between environmental consciousness and pricing dynamics within the fashion landscape. Here, the developed hypothesis is introduced.

H4: Consumers with higher levels of environmental awareness are more willing to pay a premium for circular fashion items.

Based on the existing research that consistently demonstrates a positive correlation between the depth of individuals’ circular fashion awareness and their inclination to adopt sustainable and circular practices (Kumar P. et al., 2021; Abdelmeguid et al., 2023), it is suggested that consumers with an increased level of circular fashion awareness are more likely to allocate added value to items aligning with circular principles. Thus, demonstrating a greater willingness to pay a premium. However, as previously mentioned, the literature also highlights a potential challenge in price sensitivity among consumers (Abdelmeguid et al., 2022; Hina et al., 2022). Therefore, existing literature argues that significant price increases could lead to the potential loss of existing customers (D’adamo and Lupi, 2021). Our research seeks to interpret the economic complexities of circular fashion awareness, providing a holistic perspective on how consumer consciousness interfaces with their financial choices within the circular fashion landscape. Subsequently, the hypothesis at hand is articulated.

H5: Consumers’ circular fashion awareness positively correlates with their willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion items.

Building upon the previous insights, suggesting that individuals with a greater willingness to adopt change are more likely to exhibit positive attitudes towards sustainable practices (Blas Riesgo et al., 2023), a positive correlation is proposed between consumers’ willingness to change and their willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion items. This suggests that individuals open to change are more likely to perceive the added value in circular fashion items, recognising the importance of investing in sustainable practices. However, the literature introduces a potential challenge, which is the impact of higher price tags on consumer willingness to buy (Hina et al., 2022). While consumers may express a general desire to change, existing studies argue that this openness might be undermined when circular fashion items are priced at a premium (D’adamo and Lupi, 2021). Price sensitivity remains a significant factor that can negatively influence consumers’ decisions to embrace circular fashion, even if they are generally willing to change. Our research seeks to contribute to the understanding of the complex relationship between consumers’ desire to change and their financial choices within the context of circular fashion. Following this, a hypothesis has been constructed.

H6: Willingness to change positively correlates with willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion items.

Research consistently highlights a global trend towards enhanced environmental awareness, accompanied by consumers increasingly recognising the ecological impact of their choices (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau, 2020; Liu et al., 2023). The literature suggests enhanced environmental awareness often aligns with greater openness to adopt sustainable and environmentally friendly behaviours (Wai Yee et al., 2016). Therefore, this indicates that consumers with a strong environmental consciousness tend to exhibit more proactive attitudes towards changing their purchasing, usage, and disposal behaviour patterns, reducing waste, and embracing sustainable alternatives (Ertz et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021). Based on that, the following hypothesis has been developed:

H7: Consumers with higher levels of environmental awareness are more willing to change their behaviour.

The growing global awareness of circular fashion principles indicates an increased understanding of the environmental implications of the current linear fashion system (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau, 2020; Liu et al., 2023). Existing studies suggest that increased circular fashion awareness is often linked to greater interest in behavioural change, as consumers become more aware of the benefits of circular practices such as reducing, reusing, repairing, recycling, upcycling, and sustainable production (Ertz et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021). Consumers familiar with circular fashion concepts may be more open to altering their behaviour patterns in favour of sustainable and circular choices within the fashion context. Following this, the subsequent hypothesis has been formulated:

H8: Consumers with higher levels of circular fashion awareness are more willing to change their behaviour.

Studies underscore a global shift in consumer attitudes, indicating an increasing willingness to embrace change, particularly in adopting circular fashion practices. The literature suggests that consumers who express a general openness to change may be more inclined to incorporate circular behaviours (Ertz et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021; Liu et al., 2023). However, it is essential to note the opposing research that suggests an attitude-behaviour gap, where the expressed willingness to change does not always translate into corresponding actions (Abdelmeguid et al., 2023; Auger and Devinney, 2007; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023; Musova et al., 2021). Some studies indicate that despite positive intentions, individuals may face barriers in translating their willingness to change into actual circular behaviour, indicating the complexities inherent in circular consumer practices (Park and Lin, 2020). The research seeks to interpret these complexities, providing an understanding of the correlation between willingness to change and circular behaviour. Presented next is the developed hypothesis.

H9: Consumers’ willingness to change positively correlates with their circular behaviour.

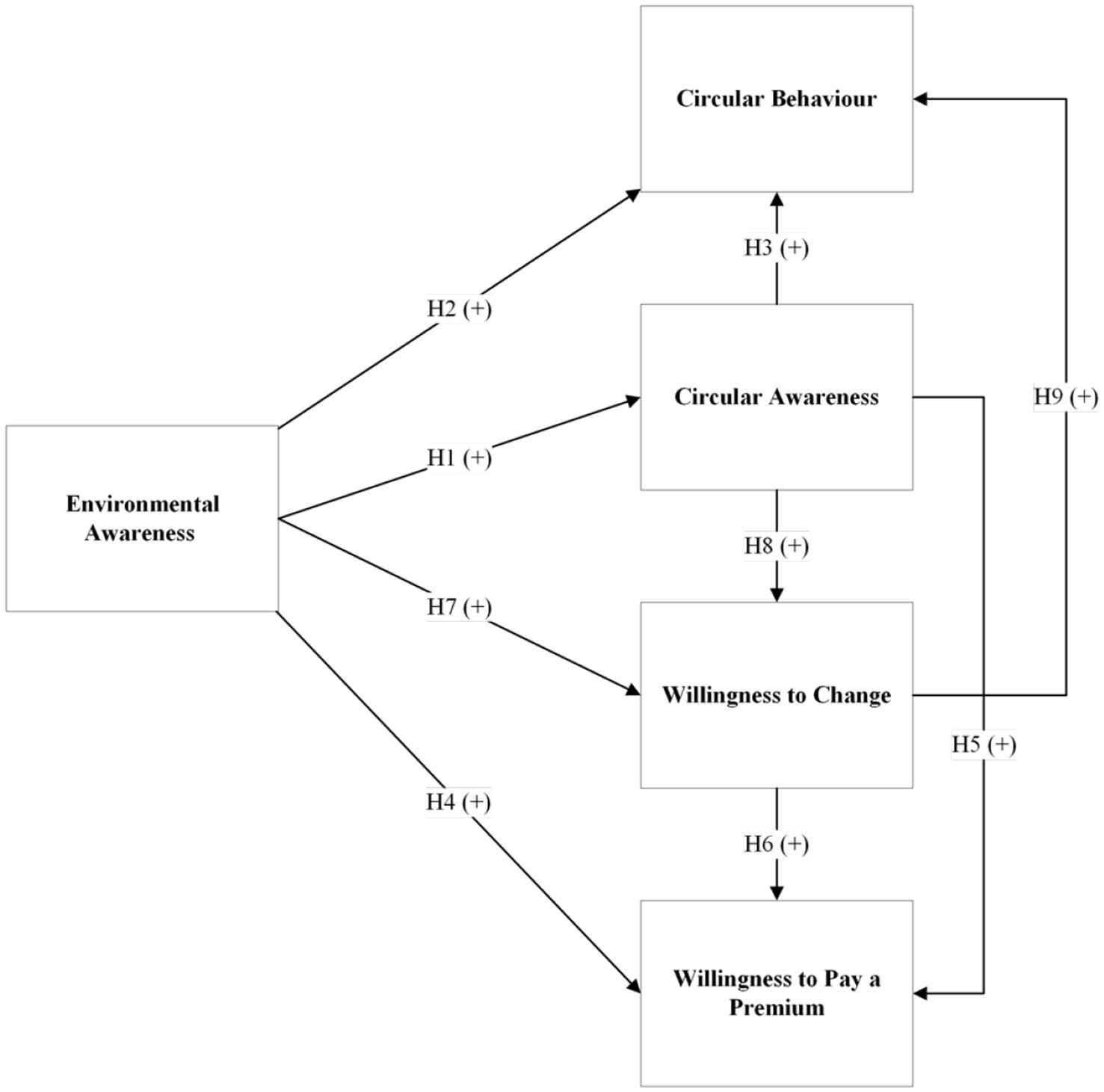

2.2 Conceptual framework

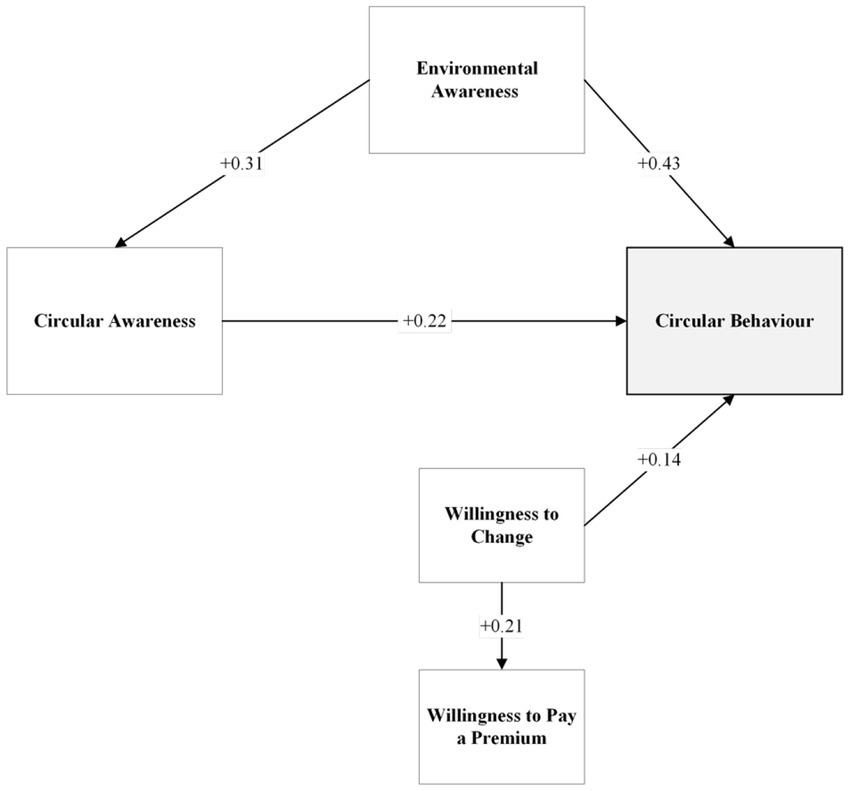

The hypotheses developed establish the foundation for the study and guide the empirical analysis to reveal the complex dynamics in the field of circular fashion. The proposed conceptual framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

This framework is built on three theoretical foundations. First, stakeholder theory highlights the role of consumers as central stakeholders whose awareness, preferences, and behaviours such as environmental awareness, circular fashion awareness, and willingness to change influence and are influenced by brands’ circular strategies (Kumar Mangla et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Second, contingency theory provides the rationale for considering contextual and demographic factors, recognising that the relationships among these constructs may vary according to different consumer segments, market contexts, or socio-cultural environments (Chen et al., 2018; Kumar A. et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2021). Third, institutional theory explains how external pressures, including changing social norms, regulations, and cultural expectations, shape variables such as willingness to change and willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion (Ranta et al., 2018; Bag et al., 2021b).

As shown in Figure 1, the conceptual framework suggests that environmental awareness influences circular fashion awareness (H1), circular behaviour (H2), willingness to pay a premium (H4), and willingness to change (H7). The framework also suggests that circular fashion awareness relates to circular behaviour (H3). Then, models the correlation between circular fashion awareness and willingness to pay a premium (H5). Moreover, the framework illustrates the positive impact of willingness to change on the desire to pay a premium (H6), as well as the positive effects of circular fashion awareness on the desire to change (H8). Finally, the framework shows that willingness to change positively correlates with circular behaviour (H9).

By integrating stakeholder theory, contingency theory, and institutional theory, the conceptual model not only explains the core relationships among awareness, willingness, and behaviour, but also situates these constructs within the broader system of stakeholder influences, contextual variability, and institutional pressures. This multi-theoretical approach ensures a robust explanation of the factors shaping circular fashion engagement.

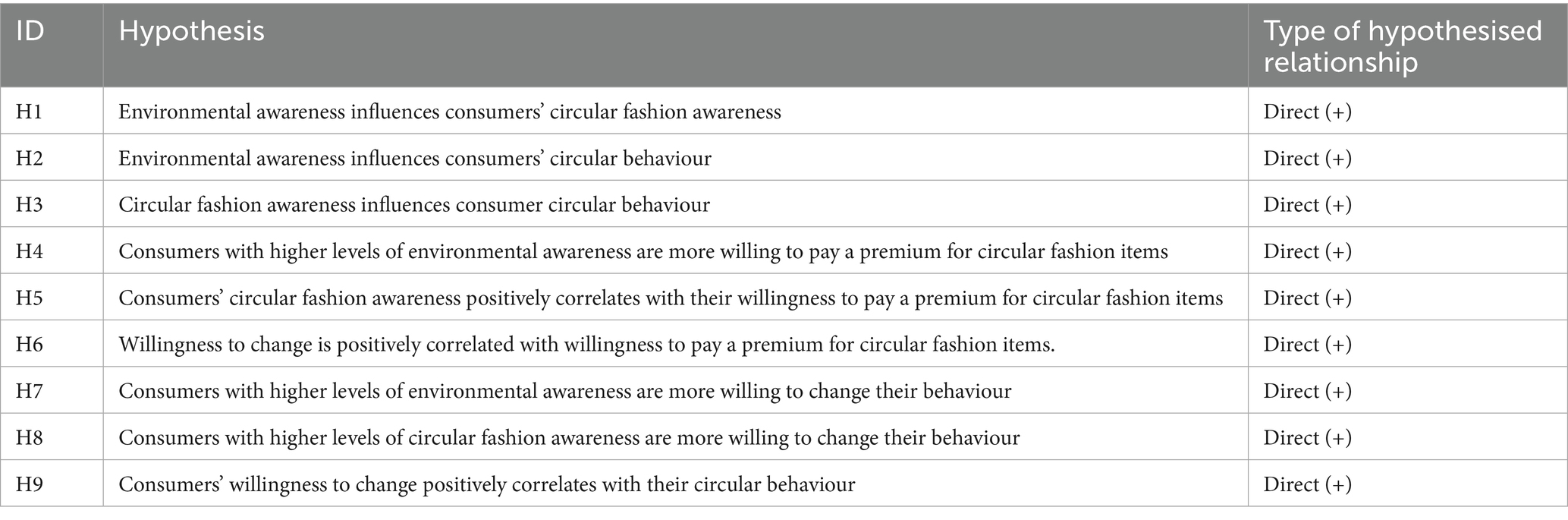

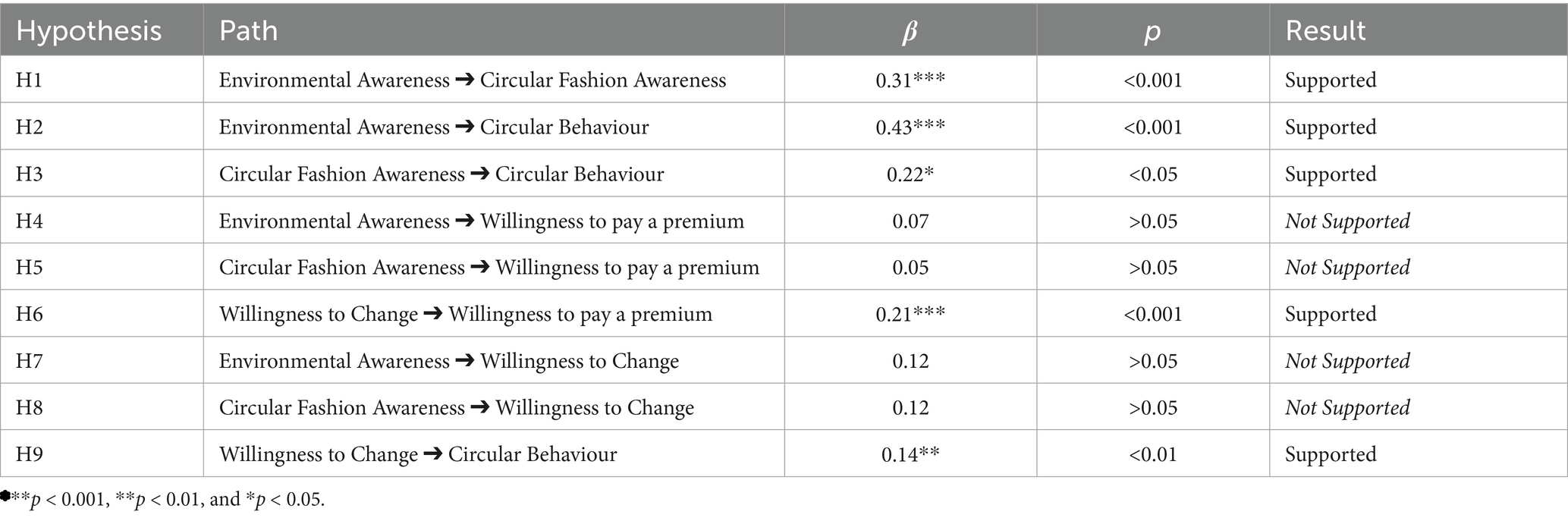

Table 1 shows a summary of the hypotheses developed.

3 Methods

The philosophical stance used to guide this study is positivism since it advocates that reality exists independently of human perception and can be studied through scientific, empirical, observable, and measurable phenomena, focusing on objectivity and generalisation of findings (Saunders et al., 2019). Moreover, the research follows a deductive approach as the hypotheses developed are derived from established theories and previous research findings (Bell et al., 2019). Therefore, the survey questions are designed, and the data is collected to test these pre-defined hypotheses to confirm or refute existing theories or predictions. Furthermore, the research strategy employed in this study is a mono-method utilising online surveys as the primary data collection method. This survey aims to assess the consumers’ behaviours and attitudes towards circular fashion, as well as to explore the factors that influence consumers’ circular behaviour.

3.1 Pilot testing

Prior to the survey administration, a pilot test was conducted involving 30 participants. The pilot test aimed to evaluate the clarity, flow, relevance, flow, and practicality of the survey questions, as well as to observe the adequacy of the instructions and identify the problems with the questions (Bryman, 2012). Additionally, the data collected during the pilot testing was used to run preliminary analyses to confirm the relevance and adequacy of the collected data. Following the outcome of the pilot testing, minor modifications were implemented to improve the research instrument’s reliability and validity.

3.2 Data collection

The survey was designed and administered using Qualtrics, an online platform, where the survey link was shared with approximately 1,000 potential participants. The survey intentionally targeted consumers from Generation Z and Generation Y (Millennials), without imposing any geographical restrictions. This focus stems from recognising that previous research findings suggest these younger generations are more environmentally conscious and are more likely to engage with circularity practices globally (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau, 2020; Liu et al., 2023), underlining the rationale for specifically targeting them. In selecting participants for this study, ethical considerations played a pivotal role in determining the eligibility criteria. Thus, Generation Z consumers born between 1997 and 2005 were a target population of interest due to their relevance to the research topic. However, it was deemed ethically appropriate to exclude individuals under the age of 18 from participation, ensuring that participants are fully able to provide their informed and valid consent without the need for a parent or guardian’s consent. Therefore, the online survey targets explicitly those between the ages of 18 and 42.

The survey encompassed a comprehensive set of 13 questions (Appendix A) distributed across eight sections: (1) Demographic variables, (2) Environmental awareness, (3) Circular Fashion Awareness, (4) Key information, where participants are provided with the definitions of Circular Fashion and its four practices used in throughout the survey including reduce, reuse, repair and recycle, (5) Circular Behaviour, (6) Willingness to Change, (7) Willingness to pay a premium, and finally (8) Drivers to Purchasing decisions.

The research involves the utilisation of non-probability sampling since participants were not selected at random and the survey link was shared on social media, where individuals who are readily available or easily accessible volunteer to take part in the survey, which makes it a form of convenience sampling (Bryman, 2012). Furthermore, this is cross-sectional research, where the data collection period spanned August 2023. In adherence to ethical considerations, participants in this research were ensured complete voluntary participation and were allowed to withdraw at any time before survey submission. The survey was conducted anonymously, upholding the participants’ privacy, and all collected data was kept confidential. Furthermore, explicit consent was obtained from participants, confirming their understanding of the research description and their agreement to its terms.

3.3 Data analysis

A total of 415 survey responses were received. However, after removing the incomplete surveys and the responses with potential bots, a total of 408 valid survey responses were included in the analysis. This represents a response rate of around 40.8%. The data collected from the valid responses are exported to SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) to analyse the demographic variables, the variance in Generation Z and Generation Y responses, and the moderation effects. Furthermore, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was employed, using the software AMOS, as the statistical technique to test the hypotheses formulated from the existing literature. SEM allows for the examination of complex structural relationships between measured and latent variables and is particularly suitable in analysing and modelling behavioural and social sciences data (Hair et al., 2014). In this study, latent variables such as consumer willingness to change and pay a premium, and environmental and circular fashion awareness are not directly observed or measured. Still, they are concluded from the survey results (Thakkar, 2020). SEM enables a structured approach to confirm these latent variables and examine their interconnections with greater accuracy, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing consumer behaviour.

While alternative methods such as Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) approaches, Factor Score Path Analysis, and Partial Least Squares (PLS) were considered, SEM was chosen for the advantages of hypothesis testing in behavioural research. MCDM methods are valuable when the primary goal is to rank or prioritise options based on multiple criteria and are most appropriate for decision-making scenarios (Zavadskas and Turskis, 2011; Kumar et al., 2017) rather than for testing theoretical models or examining the linear relationships among variables (Sadaa et al., 2023). In contrast, SEM is specifically designed to evaluate complex relationships between both observed and latent constructs, making it ideal for studies that seek to confirm hypothesised pathways within a conceptual framework (Hair et al., 2014; Thakkar, 2020). Additionally, unlike Factor Score Path Analysis, which primarily focuses on factor loadings, SEM incorporates fit indices (e.g., Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) to evaluate how well the model aligns with the data, while also providing a more robust assessment of model validity through significance tests (Kline, 2023). Given the large sample size of 408 responses, SEM’s covariance-based approach provides more accurate parameter estimates than PLS, which is typically preferred for smaller sample sizes or less-developed theoretical frameworks, particularly when the focus is on exploring causal relationships rather than hypothesis testing or model confirmation (Hair et al., 2014; Thakkar, 2020). These capabilities make SEM a highly suitable choice for this study’s analysis of behaviour towards circular fashion.

4 Results and discussion

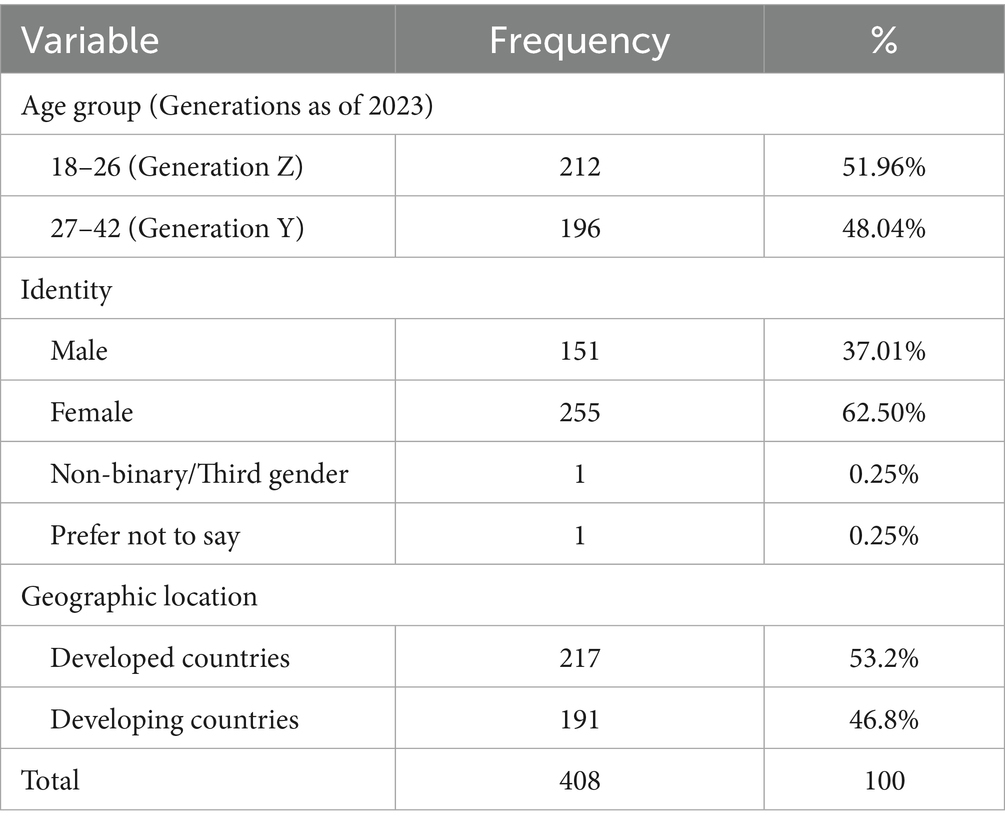

4.1 Sample demographic profile

The demographic variables composition of the sample is presented in Table 2. Of the 408 participants, the sample size for both generations is nearly equal. Regarding the identity of participants, as seen in Table 2, the majority of the participants were females. Furthermore, the geographical diversity of the sample was evident in the broad spectrum of the participants’ countries of residence including, but not limited to, countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, Greece, Thailand, India, Egypt, and United Arab of Emirates. Based on The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2023), the countries of residence of the participants were categorised into developed and developing countries to enhance the generalisation and relevance of our study. Regarding sample sizes, the participants residing in developing and developed countries are relatively similar since the difference between the two groups is not substantial, allowing for a fairly balanced representation. Therefore, this demographic profile sets the foundation for a thorough analysis of the research findings, considering the diversity of perspectives and backgrounds present in the sample.

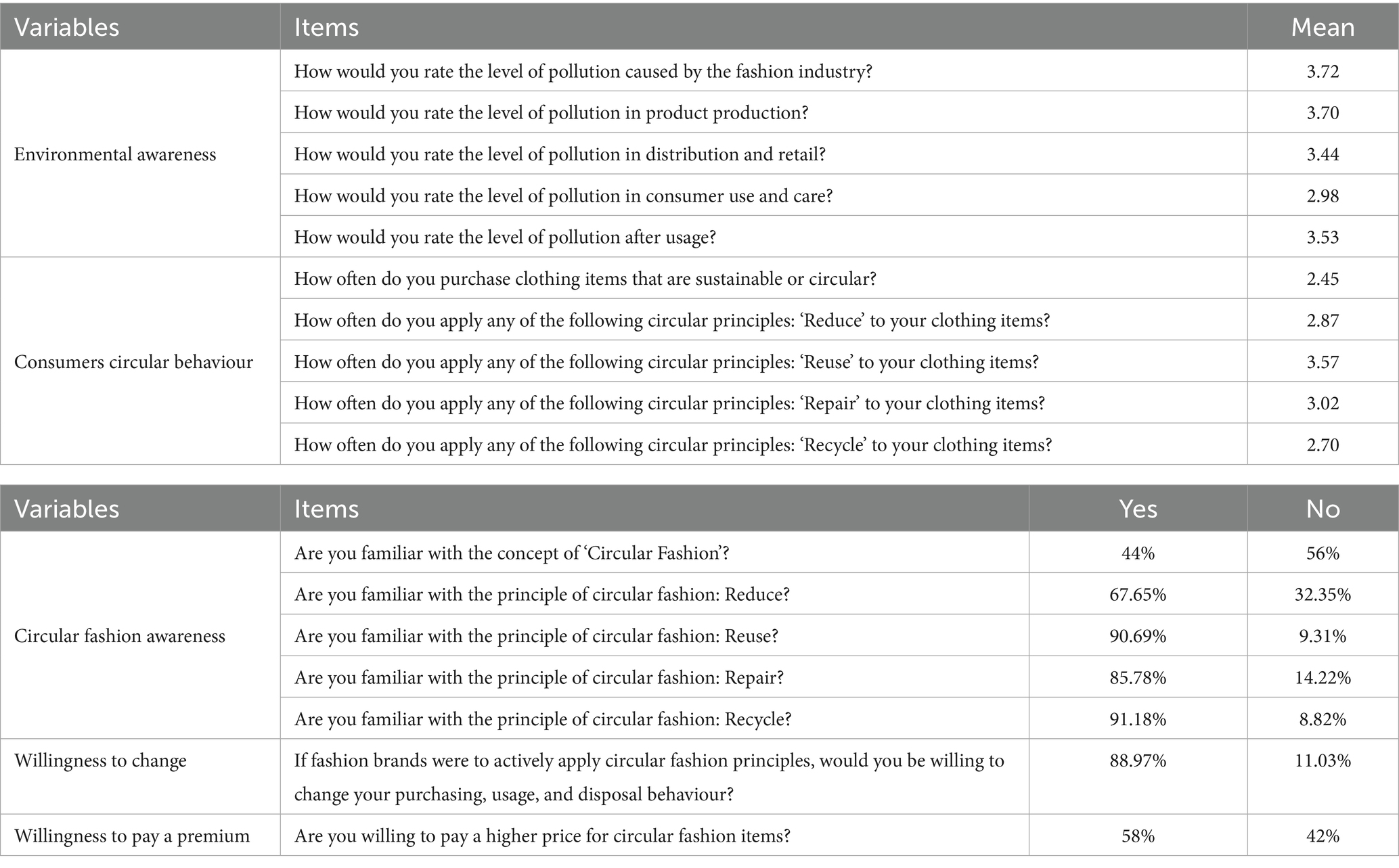

4.2 Descriptive analysis

The summary of statistics used in the descriptive analysis is shown in Table 3. In this study, a five-point scale ranging from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High) was used to measure perceptions and behaviours. This type of scale is commonly used in consumer research because it is straightforward for respondents, captures degrees of opinion or frequency, and enables clear comparisons across items (Joshi et al., 2015). Calculating mean scores is also a standard approach in the literature, as it provides a simple way to summarise overall patterns and identify which factors are seen as more or less significant (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023). While other scaling or ranking methods exist, this approach was chosen for its ease of interpretation and consistency with previous studies on sustainable fashion and consumer attitudes (Blas Riesgo et al., 2023; de Aguiar Hugo et al., 2023; Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2023).

The calculated mean for the respondents’ perception of the level of pollution generated by the fashion industry was found to be 3.72 on a scale ranging from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High). This mean value suggests that, on average, consumers tend to agree that the fashion industry’s impact on pollution is ‘High.’ Similarly, participants were asked to rate the pollution level in each of the four stages of the fashion product life cycle. The findings provide insights into participants’ perceptions of pollution levels at different stages of the fashion product life cycle. The mean scores suggest that, on average, participants suggest the highest pollution levels occur in the production and after-usage phases, while the pollution levels occurring across distribution and retail, and consumers’ use and care phases are moderate. This ranking aligns with industry data and emphasises the importance of addressing environmental concerns in the production and after-usage phases. This supports the institutional theory, which suggests that organisations must respond to societal expectations and environmental pressures to gain legitimacy in the market (Ranta et al., 2018; Bag et al., 2021a). Contingency theory also applies, emphasising that businesses need to adapt their strategies based on factors such as consumer demand for sustainability (Kumar P. et al., 2021), particularly among younger generations, to remain competitive in the evolving market (Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau, 2020; Liu et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the study assessed participants’ familiarity with ‘Circular Fashion.’ The results revealed that 44% of the respondents answered ‘Yes’, indicating familiarity with the concept. In contrast, 56% of the participants responded ‘No’, suggesting that they were not familiar with the idea. These findings provide an understanding of the level of awareness among the surveyed individuals regarding the ‘Circular Fashion.’ In assessing participants’ awareness of circular fashion principles, it is evident that some principles possess more recognition than others. The majority of participants, with 91.18% familiarity, indicated their awareness of the principle of ‘Recycle’. This principle emerged as the most familiar among respondents. Following closely, 90.69% of participants indicated their familiarity with the principle of ‘Reuse’, and 85.78% reported their familiarity with the ‘Repair’ principle. Lastly, 67.65% of respondents indicated their familiarity with the ‘Reduce’ principle. This is probably due to the focus of existing literature and research on recycling while possibly neglecting the preferable and higher-priority elements of the waste hierarchy, such as reduce and reuse, in the pursuit of effective circular systems (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Consumers’ circular fashion awareness is affected by the knowledge promoted to them.

Interestingly, while most participants were aware of the environmental issues associated with the fashion industry, they displayed limited awareness of the circular fashion concept. However, most participants demonstrated good knowledge of the various principles of the circular economy, including reduce, reuse, repair, and recycle. This indicates that consumers may have a general understanding of circular practices without necessarily associating them with the term ‘circular fashion.’ Our findings offer a subtle perspective that partially aligns with prior research, which suggests consumers’ limited understanding of circular fashion (Hugo et al., 2021). It is worth noting a distinction within our study’s participants, as they demonstrated a lack of awareness of the term ‘circular fashion’ while simultaneously displaying an awareness of the underlying principles associated with circularity.

Furthermore, the results revealed distinct patterns in the application of these principles. Based on the mean scores, the application of these principles can be ranked in descending order as follows: (1) Reuse, (2) Repair, (3) Reduce, and lastly (4) Recycle. Based on these results, two interesting findings emerged. Firstly, while ‘Recycle’ emerged as the most recognised principle among respondents, it appears to be the least implemented in practice. This suggests that there may be external factors negatively impacting consumers’ engagement in recycling practices. This could indicate a lack of facilitation by fashion businesses and brands, such as the absence of convenient recycling drop-off points. However, this issue may not be as critical as it seems, as recycling ranks lower in preference within the waste hierarchy due to its higher resource and energy consumption when compared to other principles (Kirchherr et al., 2017). Secondly, consumers exhibit a greater tendency to reuse or repair their clothing items compared to reducing the number of purchases or owned clothing items, even though reducing should ideally hold the highest implementation efforts due to having the highest priority in the waste hierarchy (McQueen et al., 2022).

Moreover, on average, participants reported a mean score of 2.45 when asked about the frequency of purchasing clothing items that are sustainable or circular. This mean score suggests that, on average, respondents indicated a relatively low frequency of such purchases. This suggests a misalignment between consumer awareness of fashion industry pollution and their actual purchasing behaviour. This aligns with previous research indicating the existence of an attitude-behaviour gap, which remains a primary challenge consumers encounter (Abdelmeguid et al., 2023; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023).

Additionally, participants’ willingness to embrace circular fashion practices and change their behaviour and purchasing choices was assessed in the study. A substantial majority of respondents, representing around 89% of the participants, expressed their willingness to change their purchasing, usage, and disposal behaviour if fashion businesses and brands were to apply circular fashion principles actively. Conversely, approximately 11% of the participants were reluctant to change their behaviour under these circumstances. This implies that it is more about what is offered to consumers by fashion businesses and brands.

Furthermore, when the participants’ willingness to pay higher prices for circular fashion items was examined, 58% of the participants expressed their willingness to pay higher prices, and 42% of the participants were unwilling to pay higher prices for such items. The participants who expressed their willingness to pay higher prices for circular fashion items were then asked to maximum percentage of price increase they would be willing to accept. Therefore, the average response from the participants indicated that, on average, they were willing to take a price increase of nearly 30%. Therefore, these findings present an opportunity for businesses and policymakers to leverage this willingness to facilitate the transition to circular fashion whilst considering the challenge of price premiums.

4.3 Survey insights on purchasing decisions drivers

Participants were asked to rank the factors that most influence their purchasing decisions, using a scale from 1 (most influential) to 10 (least influential). Figure 2 represents the ranking of factors in ascending order based on the mean scores obtained from their responses.

The top-ranking factor, product quality and durability, demonstrates the importance of longevity and value in clothing choices. This finding aligns with the broader sustainability and circularity perspectives, highlighting the desire for clothing items that last longer and reduce the need for frequent replacements. This finding links directly to stakeholder theory, where consumer preferences shape business strategies, and companies must adapt to meet those expectations (Meherishi et al., 2019). Price and affordability, the second most influential factor, reflect the economic realities that often direct consumer purchasing decisions (Hina et al., 2022). Therefore, balancing circularity and affordability becomes a critical challenge for consumers and the fashion industry (Abdelmeguid et al., 2022). Those two top-ranked factors are product-related factors, suggesting the significant influence that fashion businesses and brands have over consumers’ purchasing decisions (Berberyan et al., 2018). Moreover, personal interests are the third-ranked factor, arguing that consumers’ purchasing decisions are highly subjective and have an individualised nature of fashion preferences (Lundblad and Davies, 2016).

Furthermore, brand reputation and trustworthiness also hold a significant influence over consumers, stressing the importance of ethical practices in building consumer trust. Thus, it represents another factor aligned with product-related attributes and encompasses broader sustainability considerations (Berberyan et al., 2018; Abdelmeguid et al., 2022). These findings align with contingency theory, as it suggests that businesses must adapt their strategies based on both external consumer demand and internal brand values (Cardoni et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2021). Companies need to align their practices with evolving consumer expectations for sustainability and ethical standards, ensuring that they remain competitive in a shifting market environment.

Environmental sustainability and eco-friendliness have been ranked as the seventh factor influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions. This relatively lower ranking suggests that while sustainability is a consideration, it may not consistently take priority over other factors in purchasing decisions. Additionally, the least influential factor in participants’ rankings is transparency about the brand’s production processes. This suggests that while transparency is vital for some consumers, it may not be a primary concern for the majority when making fashion purchases. However, this could also suggest a lack of transparency regarding the brand’s production processes, which may not be readily available or clear to consumers at the point of sale, such as through labels or QR codes. Consequently, it may not be a factor consumers can consider when purchasing.

4.4 Structural Equation Modelling results

The SEM model tests the hypotheses formulated in this study and was assessed for its goodness of fit using several fit indices, including the chi-squared statistic, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The chi-squared evaluates the difference between the covariance matrices observed in the data and those predicted by the model (Kline, 2023). The chi-square value of 151.6 with 99 degrees of freedom had an extremely low p-value of 0.001, which is less than the threshold of 0.05, indicating an excellent fit of the model to the data (Kline, 2023). It is important to note that the chi-squared statistic can be sensitive to sample size, and its interpretation should be considered alongside other fit indices. The TLI, a goodness-of-fit index that compares the fit of the hypothesised model to a null model, has a value of 0.942 (Schumacker and Lomax, 2016). This value exceeds the threshold of 0.90, suggesting an acceptable fit of the model to the data (Whittaker, 2016). Similarly, the CFI, another measure of model fit that compares the target model to the null model, has a value of 0.958, suggesting a superior model fit (Byrne, 2011). The RMSEA, a measure of the discrepancy between the hypothesised model and the population model, has a value of 0.036 (Thakkar, 2020). With an RMSEA value below the threshold of 0.05, the model demonstrates a good fit for the data (Thakkar, 2020). Overall, the fit indices collectively indicate a good fit of the SEM model to the observed data, providing empirical support for testing the hypotheses derived from the theoretical framework.

4.5 Hypotheses testing

A path analysis was performed to test the hypotheses, and considering a 95% confidence level, the results were found to support 5 out of the 9 hypotheses, as shown in Table 4.

Firstly, H1 was supported (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), indicating that higher environmental awareness is positively associated with increased circular fashion awareness among consumers. This finding agrees with prior research suggesting that environmental consciousness plays a crucial role in promoting an understanding of circular fashion (Abdelmeguid et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023). H2 was also supported (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), indicating that higher environmental awareness positively influences the adoption of circular behaviour among consumers. Consistent with existing research, the results supported this hypothesis, indicating that individuals with higher environmental awareness are more likely to engage in circular fashion practices (Ertz et al., 2016; Zhang, 2021). This emphasises the critical role of environmental consciousness as a driving factor for consumers to embrace circular behaviours within the fashion industry. Likewise, H3 was supported (β = 0.22, p < 0.05), confirming that higher circular fashion awareness is positively associated with increased adoption of circular behaviour among consumers, such as purchasing second-hand fashion items (Aramendia-Muneta et al., 2022). This presents an opportunity for education and communication efforts and initiatives to bridge this awareness gap and promote the relevance of circular fashion principles among consumers, as suggested by Dissanayake and Perera (2016).

Furthermore, H4 was not supported (β = 0.07, p > 0.05), indicating no statistically significant relationship between environmental awareness and willingness to pay a premium. This finding suggests that while environmental awareness may drive awareness and adoption of circular fashion practices among consumers from Generations Y and Z, it may not necessarily translate into a willingness to allocate financial resources to purchase circular fashion items. This aligns with contingency theory, which suggests that businesses need to adapt their strategies, such as pricing models, to meet the demands and limitations of the current consumer market, including price sensitivity and economic factors (Kumar P. et al., 2021).

Similarly, H5 was not supported (β = 0.05, p > 0.05), indicating no statistically significant relationship between awareness of circular fashion practices and the willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion items. This implies that familiarity with circular principles does not necessarily translate into a desire to pay a premium for such items. This highlights the challenge for fashion businesses to balance consumer demand for sustainable or circular fashion with price consciousness, as addressed by contingency theory and stakeholder theory, which emphasise the need to adapt to economic conditions and consumer preferences (Jabbour et al., 2018; Meherishi et al., 2019). As highlighted in existing literature, this challenge requires fashion businesses and brands to assess whether they are prepared to assume the risk of losing some of their current consumers in exchange for the possibility of attracting future customers who are willing to pay a circular premium (D’adamo and Lupi, 2021). Alternatively, it underlines the need for fashion businesses and brands in the fashion industry to find ways to make their products more accessible and affordable to a broader consumer base.

Moreover, H6 was supported (β = 0.21, p < 0.001), confirming the positive relationship between willingness to change and paying a premium. Therefore, as suggested in existing literature, individuals more open to changing their behaviour are willing to invest in circular fashion products (Francis and Hoefel, 2018; Gazzola et al., 2020). This highlights the importance of consumer attitudes and their willingness to shape consumers’ purchasing decisions, reinforcing the connection with stakeholder theory.

Controversially, H7 was not supported (β = 0.12, p > 0.05), indicating that there is no statistically significant relationship between environmental awareness and the willingness to change behaviour among consumers. This suggests that while environmental awareness may influence awareness and adoption of circular fashion, it may not directly impact consumers’ readiness to change their behaviour. One possible reason for this non-significant result is that environmental awareness alone may not be sufficient to overcome established habits or practical barriers to behaviour change (Blas Riesgo et al., 2023). Factors such as perceived inconvenience, lack of alternatives, or social and cultural norms may play a stronger role in shaping willingness to change (Musova et al., 2021). Additionally, previous research indicates that the translation from awareness to action is often mediated by other variables, such as perceived value and risk, social influence, behaviour control, or emotional engagement, which were not directly measured in this study (Lin and Chen, 2022; Blas Riesgo et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023). It is also possible that the frequent exposure to environmental messages among Generation Y and Z has led to greater scepticism, particularly in light of concerns about greenwashing or a perceived lack of real impact. At the same time, other practical and personal priorities may take priority, making it less likely that awareness alone will drive meaningful behavioural change.

Interestingly, H8 was not supported (β = 0.12, p > 0.05), revealing no statistically significant relationship between circular fashion awareness and the willingness to change behaviour among consumers. This result suggests that being aware of circular fashion concepts does not automatically translate into a personal motivation or readiness to change established consumption patterns. Practical constraints limited perceived impact, or scepticism about the effectiveness of individual action could be contributing factors. It may also reflect that awareness of principles like recycling or repair is widespread, but a willingness to make the required effort or adopt new routines depends on additional drivers, such as rewards and incentives, peer behaviour, or supportive infrastructure (Cruz and Rosado da Cruz, 2023; Liu et al., 2023). These findings emphasise the importance of moving beyond informational campaigns to address practical, social, and psychological barriers to change in future research and policy interventions.

Finally, H9 was supported (β = 0.14, p < 0.01), confirming that a higher willingness to change behaviour is positively associated with increased adoption of circular behaviour among consumers. Hence, individuals who are more willing to change their purchasing, usage, and disposal behaviours are more likely to engage in circular practices, such as reducing their new clothing purchases or repairing clothing items (Kumar P. et al., 2021). This aligns with institutional theory, as the increasing consumer willingness to change behaviours reflects broader societal pressures that encourage sustainability (Bag et al., 2021a).

4.6 Structural Equation Modelling framework

A SEM framework was developed to illustrate the relationships among key variables in our study based on the hypothesis results (Figure 3). The SEM framework incorporates several crucial pathways, each representing the standardised coefficients indicating the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables. A higher standardised coefficient indicates a more substantial impact, and the positive or negative sign indicates the direction of the influence. A higher standard deviation also shows that the variable is more reliably measured and contributes more strongly to the overall framework.

Figure 3. Structural Equation Modelling framework showing relationships between key factors influencing consumer circular behaviour based on hypothesis results.

Our findings demonstrate that when environmental awareness goes up by 1 standard deviation, circular behaviour goes up by 0.43 standard deviation, and circular fashion awareness goes up by 0.31. These coefficients signify the strength and direction of the linear relationship between environmental awareness and the respective outcomes. Similarly, as circular fashion awareness increases by 1 standard deviation, circular behaviour increases by 0.22 standard deviation. This coefficient signifies the positive impact that awareness of circular fashion practices has on shaping individuals’ behaviours within the context of circular fashion. Finally, the influence of willingness to change is highlighted in the framework, with a standardised path coefficient of 0.14 for circular behaviour and 0.21 for willingness to pay a premium. These coefficients show the impact of willingness to change on circular behaviour and its effect on the desire to pay a premium for circular fashion items and practices. Therefore, our findings demonstrate that environmental awareness exerts the highest impact within the framework, emphasising its pivotal role, while willingness to change, though influential, has the least impact on shaping consumers’ behaviour towards circular fashion.

4.7 Practical implications

This study has a few practical contributions to the field of circular fashion. Firstly, it can be a guideline for fashion businesses, brands, and policymakers to understand the factors that positively influence consumers’ circular behaviour among Generation Y and Generation Z. For example, our findings underscore the significant impact of environmental and circular fashion awareness on consumer behaviour. As a result, businesses and brands are urged to ensure widespread access to relevant information, promoting awareness that encourages sustainable development and aligns with the natural consumers’ lifestyles (SDG12). This is consistent with stakeholder theory, which stresses the importance of addressing the interests of key groups, including consumers, in strategic decision-making. Moreover, the study advocates for actions aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG13), emphasising the necessity to enhance education and raise awareness of climate change and early warnings.

Secondly, providing insights into the ranking of factors driving consumers’ purchasing decisions can be highly valuable to fashion industry players looking to align their strategies with consumer preferences amongst Generation Y and Generation Z. Additionally, reducing waste generation through various options, such as prevention, reusing, and recycling, aligns with SDG12. These recommendations reflect institutional theory, highlighting the role of regulatory and societal pressures in shaping industry behaviour. Our findings demonstrate that fashion businesses and brands actively incorporating these practices positively impact consumers’ readiness for change. This willingness to change, in turn, exhibits a positive correlation with positively influencing consumer behaviours towards sustainability and circularity, as well as a higher willingness to pay premium prices. However, strategically considering pricing to retain existing customers without losing them to circular premiums (SDG12) and exploring alternative revenue streams to offset pricing impacts is equally important.

Therefore, our findings demonstrate the importance of specific variables to bridge the attitude-behaviour gap and align industry practices with consumer perceptions and preferences. These insights will be invaluable in guiding stakeholders towards facilitating the implementation of circular fashion practices and positively influencing individuals’ behaviour in the context of circular fashion. Consequently, adapting industries for sustainability and clean and environmentally friendly industrial processes to enhance the efficiency of using resources aligns with SDG9, encouraging meaningful and impactful change actions in the fashion industry in all countries, per the respective capabilities of each country.

5 Conclusion

This study aimed to explore the factors influencing consumers’ circular behaviour, specifically focusing on Generation Y and Generation Z cohorts. Employing surveys as the primary data collection tool and utilising the analytical power of SPSS for descriptive and comparative analysis. SEM was employed to test the hypotheses formulated from the existing literature and prior research findings.

Five out of the nine hypotheses were supported by empirical evidence, revealing significant insights into the complex relationships of environmental consciousness, circular fashion awareness, willingness to pay a premium, and the willingness to change behaviour among both generations. A concise summary of our key findings is as follows. Firstly, there is a statistically positive relationship between environmental awareness and consumers’ circular fashion awareness (H1). Secondly, the three variables that influence consumer behaviours are environmental awareness (H2), circular fashion awareness (H3), and willingness to change (H9). Finally, there is a positive correlation between the willingness to change and the willingness to pay a premium price for circular fashion items (H6). However, our study also revealed situations where the data did not support the formulated hypotheses. For example, there is no statistically significant relationship between environmental awareness and the consumers’ willingness to change their behaviour (H7) or their willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion items (H4). Similarly, there is no statistically significant relationship between circular fashion awareness and consumers’ willingness to change their behaviour (H8) or their willingness to pay a premium for circular fashion items (H5).

In addition to testing these hypotheses, our study revealed critical insights into the awareness and behaviours of the participants. Notably, the majority of participants exhibited an awareness of the fashion industry’s high pollution levels. However, it is intriguing to note that most of them were not yet familiar with the circular fashion concept, although they demonstrated awareness of the different principles of circularity. Furthermore, the findings showed that most participants rarely purchased circular or sustainable clothing items. This emphasises the existing gap between awareness and buying behaviour in this domain. However, a very high percentage of the participants expressed a willingness to change their behaviour to be more supportive of circularity, suggesting the growing interest in circular fashion practices. Nevertheless, the majority of participants are not willing to pay a circular premium. Finally, when participants were asked to rank the factors that matter most in their purchasing decisions, some clear trends emerged. At the top of their list were factors like product quality and durability, followed closely by price and affordability. Personal interests, brand reputation, and the latest fashion trends also played significant roles in their choices. Interestingly, environmental sustainability and eco-friendliness were important but fell a bit lower on the list, indicating a potential area for growth in consumer awareness and preferences.

Despite the significant contributions of this study, it features a few limitations. Firstly, the study uses convenience sampling, which is a non-probability sampling method, due to the availability and accessibility restrictions encountered. This sampling method does not provide a random representation of the entire population, making it challenging to generalise findings to the broader population. Since individuals are not selected randomly, a selection bias may occur, where certain groups within the population are underrepresented or overrepresented in the sample. Thus, to ensure an unbiased and representative sample, future research should explore a wider range of sampling techniques. Secondly, this study collected data from consumers using surveys with closed-ended questions. Closed-ended questions, while efficient, limit participants’ responses to predefined choices and may not capture the full spectrum of participant perspectives. Future research could consider collecting data using qualitative methods or surveys with open-ended questions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of consumer behaviours. Moreover, while our survey offers valuable insights into the perspectives of Generation Y and Generation Z globally, it’s important to note that the data represents both developing and developed countries without further analysis. Given that this wasn’t the primary focus of our research, a recommendation for future studies is to conduct a more detailed examination to determine trends specific to different socio-economic contexts, enhancing the depth of our understanding. Finally, although this study focused on Generations Y and Z, it did not conduct a direct comparison of behavioural differences between these cohorts. Future research is encouraged to analyse and compare the specific behavioural patterns and attitudes of Generation Y and Generation Z, which could provide further insight into generational influences on circular fashion adoption.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AA: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. MA-S: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. KS: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants who took part in the survey, contributing valuable insights and making this research possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1630453/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdelmeguid, A., Afy-Shararah, M., and Salonitis, K. (2022). Investigating the challenges of applying the principles of the circular economy in the fashion industry: a systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consumpt. 32, 505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2022.05.009

Abdelmeguid, A., Afy-Shararah, M., and Salonitis, K. (2023). Mapping of the circular economy implementation challenges in the fashion industry: a fuzzy-TISM analysis. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 4, 585–617. doi: 10.1007/s43615-023-00296-9

Abdelmeguid, A., Afy-Shararah, M., and Salonitis, K. (2024). Towards circular fashion: management strategies promoting circular behaviour along the value chain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 48, 143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2024.05.010

Ali, S. S., Ersöz, F., Kaur, R., Altaf, B., and Weber, G. W. (2021). A quantitative analysis of low carbon performance in industrial sectors of developing world. J. Clean. Prod. 284:125268. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125268

Angel, M., Subramanian, G., and Muthu, S. (2018). Environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes sustainable luxury cases on circular economy and entrepreneurship. Available online at: http://www.springer.com/series/13340 (Accessed July 5, 2023).