Abstract

Introduction:

Sustainable energy transitions have become an urgent global necessity. However, developing countries face critical challenges at the intersection of rising energy demand, inadequate infrastructure, constrained financial resources, and increasing climate commitments. Understanding how these nations navigate the shift toward sustainable energy systems is essential to accelerating global decarbonization.

Methods:

This systematic review employs the DASOBI framework to synthesize empirical evidence on energy mix transitions and decarbonization pathways in developing countries between 2010 and 2025. Research questions were developed using the PICOS model, and 17 peer-reviewed studies were identified and analyzed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines to ensure methodological rigor.

Results:

Findings reveal divergent transition trajectories among developing countries. Nations such as Morocco and Brazil demonstrate progress through effective institutions, supportive policy environments, and access to concessional financing, achieving measurable decarbonization outcomes. In contrast, countries like Nigeria and South Africa continue to encounter persistent barriers, including fossil fuel lock-in, limited governance capacity, and institutional inertia. Despite increasing technological acceptance, regulatory weaknesses, deficient sub-national capabilities, and societal resistance hinder broader systemic change.

Discussion:

This review highlights that sustainable energy transition in developing contexts remains constrained by structural and institutional barriers. Nonetheless, adaptive, inclusive, and impact-focused policy frameworks can foster long-term transformation. The findings underscore the necessity of strengthening governance, improving access to finance, and promoting collaborative frameworks to accelerate decarbonization in the Global South.

1 Introduction

The energy transition among developing countries is both rewarding and challenging (Cantarero, 2020). The countries are facing key challenges due to high industrial development, low infrastructure enhanced energy demand and net-zero carbon targets (Chu and Majumdar, 2012; Chirambo, 2024; Noorollahi et al., 2025).

In dissimilarity to developed economies, decarbonization goals and technological advances are the determinants of the energy transition (Markard and Rosenbloom, 2022; Li et al., 2022), emerging economies are largely involving a complex undertaking comprising of alleviating poverty, electrification, and institutional strengthening (Nasir et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Shittu et al., 2024). From global perspective, Literature reflects energy transition is biased in the environment of the developed countries (Bhattarai et al., 2022; Swilling et al., 2022). Although these studies give valuable insights on various priorities, they tend to ignore the position of developing economies toward decarbonization (D’Orazio and Pham, 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). They have not considered the soft socio-economic and infrastructural conditions at micro, industrial and regulatory levels.

At micro level, household energy stacking practice, poor financial systems and weak regulatory frameworks have been reported to be major constraints, which inclines developing country environments (Bajpain and Koul, 2025; Ferdoush et al., 2024). The Global South is constantly facing energy transition challenges at the nexus of poverty, energy infrastructure and climate justice (CPI, 2020). Adequate renewable sources could bring economic growth, although issues like lack of finance, socio-economic disequilibrium, manufacturing upscaling limitations (Blechinger et al., 2016).

These urgent gaps need to be addressed by developing an integrative and situational approach of analysis framework which could have the capability of crisping dynamic interaction among drivers, institutions and socio-technical barriers and variability of outcomes which come to play in slowing down the process of energy transition in developing nations (Fialho and Van Bergeijk, 2017). This review paper deployed DASOBI framework, a framework that classifies the energy transition landscape into six interdependent dimensions, that is, Drivers, Actors, Strategies, Obstacles, Benefits, and Impact (Minaya et al., 2024).

The methodology assists in relating diverse forms of evidence to demonstrate how energy flows occur in actual socio-economic context in developing nations, not as abstract history. Though alternative frameworks have been employed to the study of energy transitions, such as Multi-Level Perspective (MLP), Technological Innovation Systems (TIS), and Energy Justice, they are also likely to focus on the smaller parts of transition such as regime change, innovation pathways, or equity. In its turn, DASOBI framework provides a systematic yet flexible approach that takes into consideration drivers, actors, strategies, obstacles, benefits, impacts and enables them to synthesize in a more holistic way. This makes it particularly suitable when it comes to the analysis of the complicated existence of developing nations.

Despite the limited number of previous studies that analyzed the socio-economic or infrastructural factors, they tend to provide it separately without combining the drivers, barriers, and institutions and strategies. The present review addresses this gap in the fragmented nature of the approaches by relying on the DASOBI framework to provide a synthesized overview of the dynamics of transition in the developing countries.

To establish methodological explanations and analytical concentration on sustainable energy transitions with the view of decarbonization, this review resorts to the usage of the PICOS framework, i.e., the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes and Study Design structure to predesign the research question. The integrative research methodology differentiates the present study from previous studies, that emphasized on single perspectives viz., socio-economic, infrastructure, technology adoption. The present study confirms the transitions are evaluated as process drivers, actions plan and long-range impacts.

The study intends to address the research questions, as follows:

RQ1: What are the essential drivers, actors, and strategies determining energy transitions in developing economies?

RQ2: What are the barriers that hinder energy transition towards sustainable energy systems, what supporting ways to have been identified?

RQ3: What are the key benefits and long- range effects of energy transitions manifested across countries and regions?

In coalition with research questions, the research aims at research objectives, including:

In alignment with research questions, the key research objectives include:

RO1: To synthesize empirical evidence on drivers, actors, strategies, and their influence on energy mix evolution and decarbonization efforts in developing economies.

RO2: To recognize key barriers and enablers that are shaping transition processes across countries and regions.

RO3: To evaluate benefits and long-range effects, and to highlight key research gaps and future research opportunities for improving policy-relevance.

In this review study, DASOBI framework based structured synthesis is carried out, that aims to organize evidence but also serves literature review, while emphasizing significant research. Broadly, the study serves two purposes. First, the review focuses on global south countries where sustainable energy transition is driven by distinctive socio-economic and low institutional support. Second, using DASOBI framework, the study aims to synthesize academic literature into six major dimensions.

The structured synthesis using the DASOBI framework not only organizes evidence but also serves the role of a literature review, by highlighting where existing scholarships are fragmented or incomplete. This embedded approach avoids duplication while clearly exposing gaps in knowledge.

This review combines the rigor of PICOS with the conceptual scope of DASOBI to provide a framework for examining and advancing low-carbon energy transitions in developing economies.

Broadly this review paper brings a unique contribution from various perspectives. Firstly, the review forefronts global south countries where sustainable energy transition is driven by idiosyncratic socio-economic and institutional vulnerabilities. Secondly, the review study adapts DASOBI framework, with aim to systematize literature into six dimensions. Thirdly, the PICOS framework, that strengthens methodological strength to the review work. In combination these three aspects make the contribution unique from earlier studies those are less systematically structured.

2 Scope of the review and definitions

Energy transitions in developing countries are inherently multidimensional, involving interlocking shifts in policy, technology, finance, behavior, and institutional architecture. To capture this complexity, this review applies to the DASOBI framework to analyze sustainable energy transitions in developing countries. An analytical structure that categorizes systemic transitions across six interconnected dimensions viz., Drivers, Actors, Strategies, Obstacles, Benefits, and Impact (Minaya et al., 2024). Originally, designed within the framework of digital servitization, DASOBI provides a versatile but strict design approach to studying change within the sector, especially in the emerging economies.

DASOBI has been modified in terms of sustainable energy transition in this study with each dimension redefined to capture the particularities of developing countries in relation. Key drivers include policy-oriented and technological enablers, whereas the major actors include governmental organizations, business firms, and community-oriented organizations. Strategies include policy interventions and innovation pathways, whereas obstacles refer to the socio-economic and infrastructural obstacles that hinder progress. The envisaged outcomes are environmental and equity improvements whereas effects are related to more long-term systemic changes. This modification enables the framework to be a holistic perspective through which the discontinuous literature on transition can be put together and logically arranged.

Drivers refer to the internal and external forces that trigger energy transition agendas, which constitute the commitment to reducing climate change and achieving net zero emission, UN-SDGs, national development goals, growing energy demand, and the globalization of technology (Riahi et al., 2017; Sovacool, 2016).

These influences exert pressure on both governments and markets to embrace more sustainable, low-carbon systems. Actors include both state and non-state stakeholders involved in the transition process, such as national governments, energy regulators, state-owned enterprises, private investors, multilateral institutions, and civil society organizations (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009; Newell et al., 2021). The existing literature emphasized the importance of multi-level governance and role of local actors in ensuring successful transition. Strategies are intentional actions aimed at facilitating energy transitions. These encompass policy instruments (such as feed-in tariffs and renewable portfolio standards), technological options (including solar PV and hybrid mini-grids), financial instruments (like green bonds and concessional loans), and institutional frameworks (for instance, cross-sectoral planning and regional integration) (International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), 2022; Bazilian et al., 2012; Bhattacharyya and Palit, 2016). The barriers to the progress of transitions are called obstacles. Some of the most common obstacles include a lack of infrastructure (such as poor power networks), legal uncertainty, financial risks, limited local capacity, and social or behavioral inertia, such as energy stacking (Pachauri et al., 2013). The barriers can be recognized to understand the differences in the process of transition across various countries. The benefits refer to the quantified benefits or the fringe benefits of energy transition initiatives, such as the greater integration of renewable energy, the decrease in greenhouse gas emissions, the better access to energy, the creation of local employment, and the enhancement of energy security (International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), 2022; Sovacool, 2017). The review also focused studies that presented empirical or model evidence of these benefits only. Impact encompasses the long-term results of transitions, which include systemic resilience, institutional learning, and alignment with wider development objectives such as the SDGs (Geels et al., 2017; Ockwell and Byrne, 2016). There is dearth of literature that explores the transition stage. To confirm thematic precision, this research incorporates studies that particularly focus on the energy transition towards low-carbon sources. Although, authors have excluded studies that are unrelated to energy transition and allied area. Also, literature from developed countries that discussed comparative insights with developing countries is considered.

Based on the definition by World Bank (2023), the term “developing countries” is defined as set of low- and middle-income countries. It includes regions in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Small Island Developing States also known as SIDS. Table 1 demonstrates definitions of key concepts in energy transition literature. The definitions support DASOBI components and thus allow more comprehensive literature synthesis.

Table 1

| Term | Definition | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Energy transition | The process of shifting from fossil-based energy systems to sustainable, low-carbon, and renewable energy sources, involving changes in technology, policy, markets, and behavior. | Blazquez et al. (2020); Rabbi et al. (2022) and International Energy Agency (2021) |

| Energy mix | The relative contribution of various energy sources—fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear—to a country’s total energy supply. | Kartal (2022); Aydin et al. (2025) and IEA (2022) |

| Developing countries | Low- and middle-income nations classified by the World Bank, typically in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and SIDS. | Aydin et al. (2025) and Vázquez and Sumner (2012). |

| Renewable energy | Energy derived from natural resources that are replenished on a human timescale, such as sunlight, wind, rain, tides, and geothermal heat. | Rahman et al. (2022) and Agrawal and Soni (2021). |

| Hybrid energy systems | Integrated energy systems that combine multiple sources (e.g., solar-diesel, PV-grid-battery) to improve reliability, especially in off-grid or remote areas. | Ajiboye et al. (2022) and IEA (2023) |

| Green hydrogen | Hydrogen is produced using renewable electricity (typically via electrolysis), seen as crucial for decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors like industry and transport. | Superchi et al. (2023) and Hydrogen Council (2020) |

| Energy stacking | The practice by households of using multiple fuels simultaneously or seasonally (e.g., firewood, LPG, kerosene) rather than transitioning to a single modern energy source. | Shankar et al. (2020) |

| Policy mechanisms | Legislative, regulatory, and economic tools (e.g., feed-in tariffs, subsidies, renewable energy targets) designed to guide or accelerate transitions. | Abdmouleh et al. (2015) and Daszkiewicz (2020) |

| Concessional finance | Financing provided on terms more generous than market rates, often via multilateral or development banks to de-risk or catalyze investment in clean energy. | Matthäus and Mehling (2020) |

| Institutional reform | Changes in formal rules, governance structures, and regulatory frameworks that enable systemic energy transformation. | Monstadt (2007) |

| Energy access | The ability to access affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy services for household, community, or productive use. | Reddy (2015) |

| DASOBI framework | A six-dimensional analytical model capturing Drivers, Actors, Strategies, Obstacles, Benefits, and Impacts in transition processes. | Minaya et al. (2024) |

Definitions of key concepts in energy transition literature.

Source: Authors.

3 Methods

Systematic Literature Review (SLR) has been done to assess the overall structure, implementation challenges and key outcomes of energy transition among developing countries, while discussing the evolution of energy mix. The study adopted PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021) and discussed a multi-stage comprehensive review approach, as depicted in Figure 1. The review period for the study is from 2010 to 2025. The energy transition in developing countries began to rise only after 2010.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow and study selection process (Adapted from: Parums, 2021; Menon and Jain, 2021).

To confirm conceptual consistency, clarity and methodological accuracy, the PICOS framework was deployed as a coordinated guide to formulate research questions and developing the inclusion criteria (Amir-Behghadami and Janati, 2020; Methley et al., 2014). For this review paper, the developing countries were considered as the ‘population’, based on the world bank’s income classification to maintain consistency across the reviewed literature (World Bank, 2022). The ‘Interventiopoliciesered a wider range of energy polices, digital technologies, project finance, and strategic support, that aim to support energy transition roadmap. The ‘Comparators’ https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-209567 contrasted by research studies selected for review, as some differing in terms of policies, technologies and geographical regions considered. The ‘Outcomes’ broadly acknowledge the change in energy policies, determining barriers and enablers, identify co-benefits and evaluate long-range benefits and effects. The ‘study design’ that aims to ensure the inclusivity of the all form of documents to be included in this review, included empirical studies, review works, qualitative studies, use-cases, these sources offer diverse yet rigorous evidence-based for synthesis. The review articles were published between 2010 and 2025 and were retrieved from Scopus databases.

Keywords included combinations of “energy transition,” “renewable energy,” “developing countries,” “policy,” “barriers,” “actors,” and “energy mix.” A total of 452 articles were initially identified. After duplicate removal and title/abstract screening, 68 articles proceeded to full-text review. Of these, 17 studies met the final inclusion criteria and were selected for analysis. These studies represent a mix of national case studies (e.g., Morocco, Brazil, Nepal), cross-country comparisons, and modeling-based assessments focused on energy system transformation.

To minimize bias during selection and synthesis, multiple strategies were employed. First, the research team collaboratively refined inclusion and exclusion criteria through an iterative process. Next, each selected study was independently reviewed and coded based on the six components of the DASOBI framework. Ambiguous classifications (e.g., strategies that also function as institutional drivers) were resolved through discussion and consensus. The research studies that lack empirical basis to address energy transition were excluded. Using DASOBI, the review articles synthesize transformation process, policy perspective, mid and long-range assessment across developing countries.

3.1 Identification

Based on research questions, a structured search strategy in align with DASOBI has been developed to cover empirical, conceptual and applied research done around energy transition among developing countries. The search string includes combination of keywords viz., (“energy transition” OR “low carbon” OR “decarbonization”) AND (“developing countries” OR “Global South” OR “low-income” OR “middle-income”) AND (“renewable energy” OR “energy mix” OR “solar” OR “wind” OR “hybrid systems” OR “green hydrogen”) AND (“policy” OR “finance” OR “infrastructure” OR “actors” OR “institution” OR “barrier*” OR “impact” OR “benefit*”). Scopus has been deployed as primary database, Due to broader multi-disciplinary coverage, in the domain of energy, environmental science and social science. On the other hand, other databases including Web of Science and dimension were not considered in the review, due to the high reliability on Scopus that ensure comprehensive data coverage across all relevant disciplines (Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016; Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2020).

To capture diverse methodological insights, both qualitative and quantitative studies were included in the study. Also, region specific use-cases are added to represent developing countries and Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Following PRISMA guidelines, after applying exclusion- inclusion criteria, the 17 studies were selected for deployment of DASOBI-based coding and thematic synthesis. This approach allows a productive, multi-scaler dataset to exhibit not only the techno-economic aspect of energy transition along with institutional, behavioral, and governance perspective, that is significant for developing countries.

3.2 Screening and inclusion

TRigorous exclusion-inclusion criteria were applied to ensure thematic and methodological alignment with research objectives of the review study. The key focus of the study was to systematically evaluate the energy transition in developing countries along with them engage substantively with at least one dimension of the DASOBI framework. In screening phase, 68 documents were identified, 53 documents were excluded based on criteria, although 2 articles were included due to their strong relevance to the subject matter. Finally, 17 studies offer robust and geographically diverse insights into transition dynamics in developing countries.

3.3 Data extraction and synthesis

Adopted from Arksey and O’Malley (2005), the review study systematically reviewed and charted extensively in alignment with the DASOBI framework. Each article was coded in accordance with core variables of framework. The studies are further classified based on their focus on either of the applications including grid-connected renewables, decentralized hybrid systems, bioenergy, or hydrogen-based initiatives. Actors captured the role and agency of governments, utilities, financiers, communities, or international bodies. Strategies referred to tangible interventions like grid expansion, subsidy reforms, or national energy targets. Obstacles include financial and non-financial challenges (institutional, socio-cultural challenges) related to energy practices. Benefits explained various measures including emission reduction, job generation and enhanced access and Impact was coded when studies traced long-term or systemic effects, such as institutional reform, resilience building, or alignment with the SDGs. A combination of deductive (theoretically grounded DASOBI) and inductive (resulting out of the reading) was used to preserve both systematic and emergent insights. Where results were subtle or obscure, especially along the strategy-impact axis or in distinguishing national versus local policies as understood by teams were developed through refinement of team deliberation.

Quantitative indicators, including renewable energy adoption or GHG emission reductions, were reported under Benefits and Impact where they existed and qualitative statements by authors or respondents were reported when the statements were directly pertinent to the six DASOBI dimensions. Quantitative indicators (renewable energy adoption and GHG emission reduction) where identified as they directly pertinent to DASOBI dimensions. Studies focusing on institutional learning were clustered under Impact, while recurring challenges such as regulatory fragmentation or unreliable infrastructure were coded under Obstacles. Thematic integration ensued iteratively, acknowledging for internal consistency within each DASOBI dimension while evolving cross-cutting patterns that extent countries, technologies, and governance contexts.

3.4 Descriptive results

Figure 2 illustrates the regional distribution of the 17 studies included in this systematic review. A majority of the literature focuses on Asia (n = 9), followed by Africa (n = 6) and Latin America (n = 2). No study exclusively centered on Small Island Developing States (SIDS), although cross-regional models occasionally included island nations as part of broader energy transition scenarios. Countries such as India, Nepal, Pakistan, Malaysia, Morocco, and Brazil appeared most frequently, reflecting their proactive renewable energy policies and sustained engagement in international energy discourse.

Figure 2

Regional distribution of studies.

Research on sub-Saharan Africa tends to rely heavily on regional modeling and scenario analysis, with limited empirical data from community-level or implementation-focused projects. This points to an important evidence gap in capturing on-the-ground dynamics and real-world transition outcomes across some of the most energy-deprived contexts in the developing countries. As Figure 3 illustrates, the evidence base is heavily skewed toward quantitative methods (13 of 17 studies) principally techno-economic modelling, system-optimization routines, and scenario analyses. Only two studies adopt an explicitly qualitative method, and a further two combine approaches in a mixed-method design, generally to probe stakeholder engagement, behavioral drivers, or institutional dynamics.

Figure 3

Studies evaluated based on method used.

The methodology discussed energy-systems research, Figure 4 explained the thematic focus across DASCOBI frameworks for literature review. Finaly 17 studies are considered, wherein 16 studies discussed drivers with strong orientation towards policy and planning design. The Benefits and Obstacles are explained in 13 and 14 research studies, respectively. Similarly, 10 studies analyzed Actors, specifically focused on role of institutional agents in energy transition process. Noticeably, Impact was examined in 4 studies illuminating a critical gap in long-term outcomes, feedback loops, and real-world efficacy.

Figure 4

Distribution of studies across DASOBI components.

3.4.1 Research design and methodological approaches

Figure 3 depicts the methodology used for reviewing research documents. Quantitative studies dominate with widespread use of energy modeling tools and related techno-economic assessments frameworks to simulate policy impact and future scenarios.

3.5 Thematic emphasis across DASOBI components

As mentioned in Table 2, the review discussed various energy transition strategies that address developments in literature, emphasizing strong relationship between energy policies and pace of transition in developing countries. The challenges and barriers prominently underscore their role in energy transition. Energy transition policies are thoroughly covered in all 17 studies and consistently emerged as dominant focus. These policies include mid-and-range goals, deployment of suitable technologies to create hybrid and grid systems, financing mechanisms to build green systems (Rehan, 2024; Acheampong et al., 2022; Slimani et al., 2024). 16 studies comply with global decarbonization initiate viz., Paris agreement, SDG-7 and economic modernization rules (Clulow and Reiner, 2022; Gimba et al., 2023). Technology disruption emerged as a catalyst for energy transition that extensively reduces the solar PV costs, as evident in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Wang et al., 2023).

Energy Supply chain Actors were discussed in 11 studies, including policy makers of implementation agents. Key donors including central governments, funding institutions and international donors viz., world banks and GIZ (Acheampong et al., 2022; Nhamo et al., 2021). Although few research shows the role of local governments, community groups, or civil society actors, exposing a noteworthy representative gap (Gimba et al., 2023).

Table 2

| Authors | Drivers | Actors | Strategies | Obstacles | Benefits | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rehan (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Chatterjee et al. (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Clulow and Reiner (2022) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Plazas-Niño et al. (2022) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Slimani et al. (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Bhattarai et al. (2023) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Atchike et al. (2022) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Sadik-Zada (2021) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Medjo Nouadje et al. (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Karanfil and Omgba (2019) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Pokubo et al. (2024) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Telli et al. (2021) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Mbazima et al. (2022) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Ubaydullah and Kakinaka (2025) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Khalfaoui et al. (2025) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Montagna et al. (2023) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Thematic analysis using DASOBI framework.

Source: Authors.

Obstacles appeared in 14 studies, with recurring themes including weak infrastructure, financial risk, regulatory volatility, and social inertia (Plazas-Niño et al., 2022; Chatterjee et al., 2024). Such barriers were considered as contextual background instead of systematically examined in terms of their long-term effects, which made them less useful about adaptive planning or institutional reform. Thirteen studies gave positive outcomes (primarily, the improvement of accessibility and increased usage of renewable energy sources and economic advantages of creating jobs and decreased energy importation) (Slimani et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023). Nevertheless, a few studies examined distributional impacts including the beneficiaries of these transitions or equity-related issues are managed. Impact dimension, which was least attended, was only considered in four studies. The studies in general concentrated on the long-term or gave qualitative information about resilience and institutional change (Acheampong et al., 2022; Clulow and Reiner, 2022). Much of the literature that is available remains focused on input–output analysis rather than assessing the energy transitions as whether they lead to a systemic transformation or inclusive development.

The larger part of the literature is based on input–output analysis rather than energy transition assessment.

4 Comparative patterns across countries

The reviewed literature shows that there is dramatic disparity in how and what developing countries experience in terms of energy transition. Such differences are not only because of the economic situations or accessibility to resources, but also due to such factors as the capacity of institutions, political stability, and cross-border partnerships. This part brings together trends that are noted in various nations and reveals the systematic enablers and persistent barriers of different national settings.

4.1 Institutional strength and policy coherence

Those countries with robust governance systems and energy plans such as Brazil, India and Morocco have more predictable transition trajectories. The strategic modeling project of Morocco to achieve 92% renewable electricity by 2050 is backed by a strong government leadership and investment partnerships with other countries across the world (Slimani et al., 2024). Brazil obtains the support of the government-organized programs to coordinate the national development goals with the energy sector reforms. On the other hand, there are disconnected institutions in countries like Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Tanzania where a change of rules frequently happens and political instabilities frustrate the implementation process (Gimba et al., 2023; Acheampong et al., 2022; Nhamo et al., 2021).

4.2 Technological choice and resource endowment

Technological strategies frequently mirror geographic and natural resource endowments. Hydropower is prevalent in certain regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, whereas solar photovoltaic (PV) technology is gaining preference in South Asia and North Africa, attributed to abundant solar irradiation and decreasing costs (Rehan, 2024; Clulow and Reiner, 2022). Countries such as Nepal, Kenya, and Tanzania deploy hybrid mini-grid systems (PV-diesel or PV-battery) in off-grid rural areas to bridge access gaps (Acheampong et al., 2022; Gimba et al., 2023).

Although, overreliance on a single technology, especially solar without adequate investment in storage or grid integration creates vulnerability. For instance, some studies identify systemic reliability issues in PV-dominant systems lacking demand-side management (Wang et al., 2023).

4.3 Role of external finance and donor support

Donor support plays a central force to enable energy transition among low-income countries viz., Nepal, pacific island countries and east Africa. Besides, multi-national financial institutions including Word Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB) have played significant role in funding and consulting key projects (Gimba et al., 2023; Acheampong et al., 2022). Contrary, countries like India and Brazil are gradually mobilizing domestic financing sources to ensure endogenetic and sustainable system (Clulow and Reiner, 2022).

4.4 Inclusion and community engagement

Results show that community engagement is irregular across countries. In countries like Nepal and Kenya, community owned mini grids demonstrate high efficiency and social participation due to involvement of localized governance (Acheampong et al., 2022). These use-cases contribute to the importance of bottom-up planning and high level of adoption, that leads to sustainable ecosystems. Whereas Nigeria exemplifies a hierarchical system with minimal citizen involvement. It results in low adoption and high trust scarcity (Gimba et al., 2023). It is observed across reviewed literature that most national energy transition visions lack low representation from grassroot actors.

4.5 Operational challenges

Among developing countries, operational challenges including ineffective energy transition planning occurred due to ‘transition traps’ (Kaygusuz, 2012). In sub-Saharan Africa, insufficient grid infrastructure and limited transmission capacity impede the growth of clean energy besides to available renewable energy sources (Nhamo et al., 2021). In south Asia, due to land-use conflicts and slow policy reforms, the countries are undermining the sustainability prospects (Chatterjee et al., 2024). On the other hand, Latin America has high reliance on hydro-power systems inclined to climate variability, and frequent political changes disrupt the energy commitment (Clulow and Reiner, 2022). These transition traps differ the nation’s goal and require policy and technical solutions. In addition, there is no uniform trajectory that exists, although most of the developing countries show policy consistency, institutional convergence and strong social commitment for energy transition. Also, considering the future needs, most of the developing countries necessitate adaptive planning, courageous institutional reorganizations, and governance frameworks that are not only inclusive in theory but also truly participatory in practice. The review results confirm that financial innovation and community engagement are not just support tools but also enable critical systemic changes.

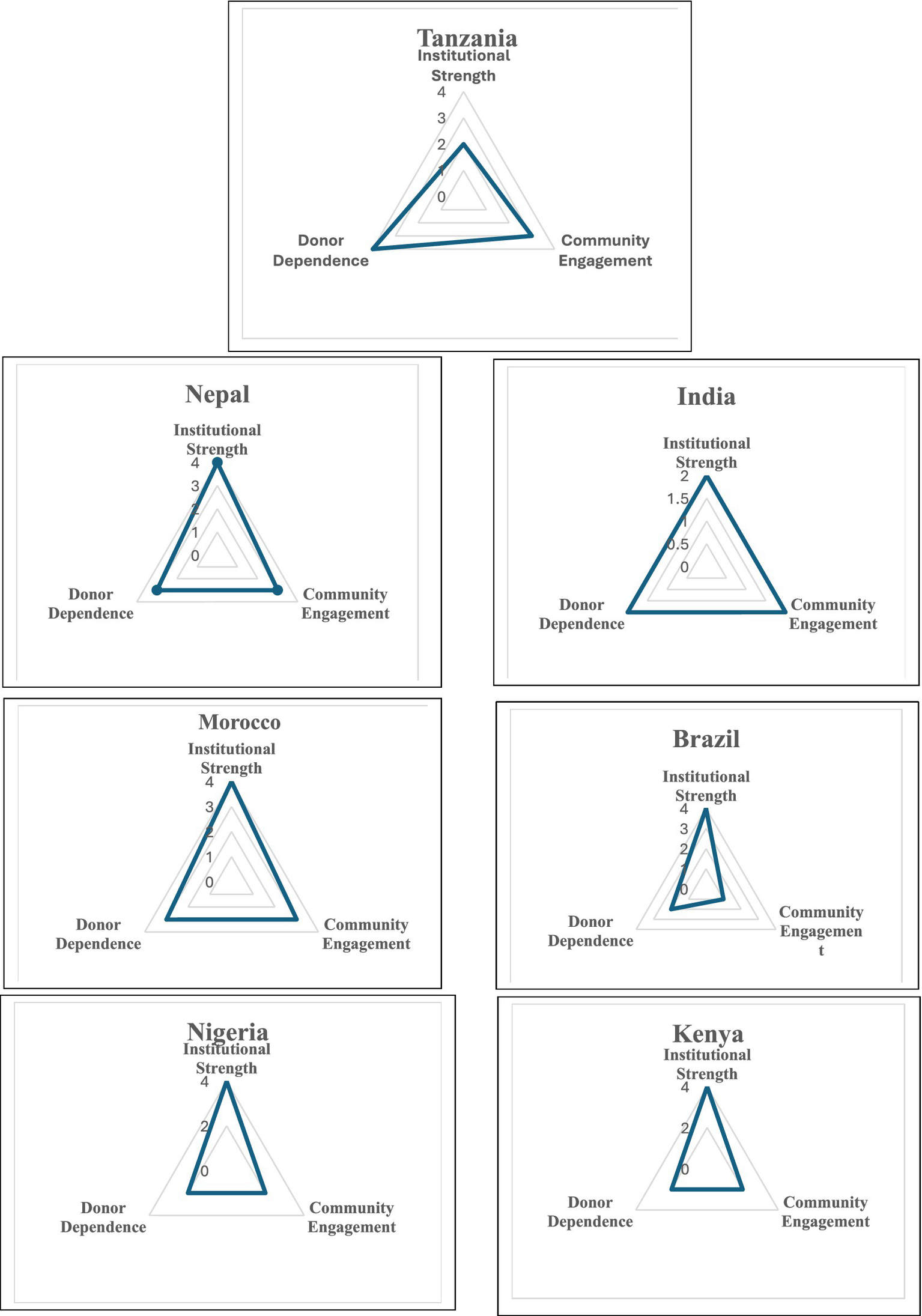

As depicted in Figure 5, the radar charts show cross-country patterns in terms of influence of institutional capacity and donor dependency and community engagement towards energy transition. Countries like Morocco and Brazil, showed significant governance structure although they lack external financing and ensure sustainable processes. India has good institutional score but low community integration. On the other hand, Nepal and Kenya present high community commitment and mini-grid deployments and collaborative planning but are also highly donor-dependence. Nigeria and Tanzania exhibit systemic weaknesses across all factors, with fragmented institutions, high donor reliance, and limited citizen involvement. These inconsistencies underline that successful transitions not only require technological readiness, but also an supported governance, local ownership, and enduring institutional ecosystems.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the differences in cross-country patterns in the influence of institutional capacity and donor dependency as well as community engagement on energy transitions are well evident in radar charts. Morocco and Brazil have developed solid governments and a lack of dependence on external financing, pointing out to more domestic and sustainable processes. India has also good institutional score but low integration in the community. At the other end, Nepal and Kenya present superb community engagement and especially in feature of mini-grid deployments and collaborative planning but are also highly donor-reliant. Nigeria and Tanzania reflect systemic weaknesses across all dimensions, with fragmented institutions, high donor reliance, and limited citizen involvement. These disparities underscore that successful transitions hinge not just on technology or capital, but on aligned governance, local ownership, and durable institutional ecosystems.

Figure 5

Comparative DASOBI dimension scores across selected countries.

5 Methodological gaps and future directions

Literature gives valuable data insights from perspective of key drivers, strategies and outcomes of energy transition, although there exist many methodological gaps.

5.1 Identified research gaps to the DASOBI framework

Drivers: the synthesis review highlights research gap in acknowledging energy transition drivers in context to developing countries, specific to socio-economic and policy making.

Actors: the previous research has lacks advocacy of role of Key actors in shaping energy transition pathways including local communities and informal institutions.

Strategies: the research also indicates review work also address gaps from strategic viewpoint, as context-definite pathways remain uncovered.

Obstacles: the review reveals persistent barriers in alignment with obstacle dimensions of DASOBI due to under analysis of institutional delicateness and financial instability in developing countries.

Benefits: the absence of significance of social justice and equity echoes a gap in the benefits dimension of DASOBI.

Impacts: the partial consideration to systemic resilience and underscores a research gap in the Impacts dimension of DASOBI.

Based on the framework developed, final sample is relatively small. This reflects both strict eligibility criteria and the limited but emerging body of peer-reviewed work focused specifically on energy transitions in the Global South.

5.2 Over-reliance on techno-economic modeling

A substantial portion of the literature is dominated by quantitative modeling approaches particularly scenario simulations and least-cost pathway analyses.

The methods used in assessed studies are primarily focused on policy designs and their implementations, although very less emphasized on political, economic and social perspectives. Thus, future works should be more emphasized on techno-economic tools using mixed-methods research that emphasized on role of institutions, individual and energy governance.

5.3 National-level bias and geographic blind spots

Due to high research dominance towards national-level transition, very less attention is given to state and province level developments, rural-urban interconnect and also to micro-level household dataset.Thus large-level data modeling is required to cater for the inequalities in energy mix, its access, affordability to masses and also the level of service quality.

Future research should be involved into data analysis at micro and macro levels and get more insights into transparent and good governance for public policy in developing countries.

5.4 Long-range strategic planning and its organizational impact

Only limited studies are focused on long-range strategic planning and interplay among key elements including organizational learning and re-instrumentation of policies and technologies.

Very few studies track long-term outcomes or feedback loops such as institutional learning, rebound effects, or path dependencies in policy and technology. Most focus on short-term outputs (e.g., MWs installed), rather than systemic shifts or unintended consequences.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs, scenario backcasting, and systems thinking to assess transition durability, scalability, and cross-sectoral impacts (e.g., water use, land rights, or employment structure).

5.5 Under-theorized role of actors and agency

Despite the DASOBI framework’s emphasis on actor dynamics, the literature often treats stakeholders as static categories (e.g., “government” or “community”) rather than relational agents embedded in power structures. There is limited theorization of how actors interact, negotiate, resist, or co-create transition pathways.

Future studies should explore actor coalitions, power asymmetries, and institutional change using political economy, transition management, or multi-level governance lenses. Special attention is needed on youth, women, and informal actors, who remain underrepresented in current research.

5.6 Gaps in evaluation of intervention effectiveness

There is a significant nonexistence of studies that evaluate impact of energy transition interventions collectively from the perspective of policy reforms, donors and technological upscaling. Although, a few studies explained national energy transition plans and underlined strategies but not implicitly evaluated their effectiveness, and socio-economic impact.

To bridge this research gap, future studies should be more focused on evaluation of related theories, quasi-experimental methodologies, and should also measure stakeholder participation in the process of energy transition to know existing practices, policy gaps and implementation challenges.

5.7 Use of single source database

A limitation of this review is that only Scopus was used as the primary database, which may have excluded some studies indexed in other repositories such as Web of Science or Dimensions. Future systematic reviews could address this by expanding database coverage to further enhance inclusiveness.

5.8 Limited-availability of peer -reviewed literature on small island developing states (SIDS)

Within its scope, the review included SIDS, although limited availability of peer-reviewed literature restricted the scope of synthesis. The future research studies could enlarge research scope on SIDS, considering their energy vulnerability and climate transitions.

6 Discussion

The results of the present review, organized in the form of the DASOBI framework, demonstrate that the energy transitions picture in the developing economies is highly fragmented, but it is evolving. Although improvement can be traced in individual examples, this situation is quite lopsided overall, with most determined by levels of institutional preparedness, feature coherence, funding scale, and social accommodation. Comparative analysis of 17 studies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, there are still bottlenecks that hamper a just and sustainable transition, despite there being positive innovations taking place. It is observed that despite their strategic relevance, the previous studies remain limited on Small Island Developing States (SIDS), that restrict the scope of evidence available for this review. SIDS are facing distinct transition challenges which include their heavy reliance on import of conventional sources of energy. Besides, they are also affected by impact caused due to climate change, low financial and institutional capacity. Although, renewable energy pilots and donor support remain prominent in SIDS. Also, their market sizes are adversely affecting their economies of scales.

Our review reinforces that beyond technology and finance, informal energy practices such as stacking, coupled with volatile financial and regulatory systems, contribute to persistent transition traps. The socio-economic perspective is often understated in reviewed studies. Although, developing countries including Morocco and Barzil are establishing the interplay between stakeholders’ expectations and policy interventions. These countries blend their energy missions, and strategic plans with UN-SDG and global renewable energy goals through robust financial and investment activities. These energy leaders are confirming the smooth energy transition through good and transparent governance mechanism.

On the other hand, there are still a lot of problems with using policies or fossil fuel lock-in or institutional rigidity in the states such as Nigeria and South Africa. The transitions in these circumstances are stagnant even after the paradigm is available as a result of the political-economy lock-in as well as fragile infrastructural systems. It confirms this hypothesis that energy transition is not merely a technology or an economic issue, but an institutional-cultural one, a regulatory stagnation possibility, and a highly uneven transcending capacity. Also revealed by the DASOBI analysis is an impressive vacuity in the perusal of the Impact and Actor dimensions. Although drivers, strategies and obstacles get intense analytical coverage, little consideration is given in most studies to long-term system impacts or diversity of actors. The community involvement, local authority, and household politics are barely placed in the national agendas. Equally, traceability of socio-technical effects in the long-term namely resiliency, adaptability, distributive justice, does not gleam conspicuously in the energy studies conducted in the Global South. What highlights is a remarkable disconnect between the policy formulation that is not reflective of the reality experienced by the energy consumers especially in areas that are marginalized or among the energy poor. Also, benefits like improvement of energy access, creation of new jobs, and reduction of emissions among others, are cited more often and they are mostly dealt with descriptively, lacking empirical follow-ups. This is a disadvantage, as it overlooks not only policy learning but also accountability of impact, or the possibility to trace how well transition proceeds over time.

Generally, the synthesis confirms that sustainable and inclusive transitions demand an entirely new way of thinking about energy systems in terms of their conceptualization and assessments. The technocratic, top-down models prevalent in most national strategies should yield to other approaches to governance that are adaptive and multilevel, and are able to respond to specific local conditions, complexity of actions, and change of systemic nature in the long-term perspective. Energy transition is not a change in supply, but it is a revolution in how societies generate, control and interact with energy.

6.1 Implications for policy and research

From the viewpoint of energy transition in developing countries, the research synthesis has significant policy implications. At policy level, the developing countries are intending to blend their national energy transition plan with local needs. It means bringing more stakeholders involvement and convergence in policy implementation. Departments concerned from key areas of concern including energy, climate, infrastructure and finance collectively enhancing the policy credibility. Also, special budgets need to be allotted for capacity building of stakeholders. From Research and Development perspective, continuous monitoring is required on evaluation framework that measures short term and long-term impact of energy transition. From Social perspective, the energy transition should be perceived from viewpoint of public benefits. Future studies should attempt in exploring and developing integrated frameworks that cover sociology, political economy, energy management, economics and business management to cater to the sustainable energy needs of the stakeholders. More insightful research brings more practical and user-focused policy formulation. Overall, these inputs can accelerate energy transition and contribute to more resilient and sustainable systems.

7 Conclusion

In developing countries, the energy transition is witnessing multi-industrial development to reduce the policy and application challenges. This research used DASOBI framework, while addressing the literature development of two and half decades into six perspectives, namely Drivers, Actors, Strategies, Obstacles, benefits and Impact. Furthermore, the analysis shows that Countries like Morocco and Brazil developed strategic alliances between the countries, marketplace and the donor that are collectively shaping the future of energy sector. In addition, research also reveals that developing countries are restricted in challenges including under-investments, high policy instability, under-developed infrastructure, that are unable pilot projects to transform into reality. While focusing on global south, the review aimed to build the context where sustainable energy transitions are becoming priority of various nations and have huge potential from policy research perspective.

The review reveals that the topic is maturing methodologically although it still lacks participatory and longitudinal insights. The studies are reflecting on strong technological perspectives but failed to contribute toward the roles of energy supply chain actors and community engagement. Impact evaluation remains sporadic, and social equity often peripheral. For energy transitions to succeed in the Global South, they must be context-sensitive, locally embedded, and socially inclusive. Future studies should highlight trust, culture, energy and climate justice. Also, future research should place more emphasis on multidisciplinary in the research domain.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SJ: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision. MS: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. AK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. TJ: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization, Resources, Software, Validation. AJ: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. MA: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The study data shall be available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abdmouleh Z. Alammari R. A. Gastli A. (2015). Review of policies encouraging renewable energy integration & best practices. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.45, 249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.01.035

2

Acheampong A. O. Opoku E. E. O. Dzator J. (2022). Does democracy really improve environmental quality? Empirical contribution to the environmental politics debate. Energy Economics109:105942. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105942

3

Agrawal S. Soni R. (2021). Renewable energy: Sources, importance and prospects for sustainable future. Energy Crises Challenges Solutions22, 131–150.

4

Ajiboye A. A. Popoola S. I. Adewuyi O. B. Atayero A. A. Adebisi B. (2022). Data-driven optimal planning for hybrid renewable energy system management in smart campus: a case study. Sustain Energy Technol Assess52:102189. doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2022.102189

5

Amir-Behghadami M. Janati A. (2020). Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in systematic reviews. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209567

6

Atchike D. W. Irfan M. Ahmad M. Rehman M. A. (2022). Waste-to-renewable energy transition: biogas generation for sustainable development. Front. Environ. Sci.10:840588. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.840588

7

Arksey H. O’malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

8

Avelino F. Rotmans J. (2009). Power in transition: an interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. Eur. J. Soc. Theory12, 543–569. doi: 10.1177/1368431009349830

9

Aydin M. Degirmenci T. Ahmed Z. Apergis N. (2025). Sustainable Development Pathways: Assessing Energy Security Risk, Information Communication Technologies, Natural Resources Rents, and Green Innovation on Environmental Quality in the United States. In Natural Resources Forum. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.70034

10

Bajpain A. Koul M. (2025). Impact of the energy transition in the electricity sector on the environment and climate change in an industrial state of Andhra Pradesh, India: a life cycle assessment approach and policy directions for developing economies. Renew. Energy246:122909. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2025.122909

11

Bazilian M. Nussbaumer P. Rogner H. H. Brew-Hammond A. Foster V. Pachauri S. (2012). Energy access scenarios to 2030 for the power sector in sub-Saharan Africa. Utilities Policy20, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2011.11.002

12

Bhattacharyya S. C. Palit D. (2016). Mini-grid based off-grid electrification to enhance electricity access in developing countries: What policies may be required?Energy Policy94, 166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2016.04.010

13

Bhattarai U. Maraseni T. Apan A. (2022). Assay of renewable energy transition: a systematic literature review. Sci. Total Environ.833:155159. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155159,

14

Bhattarai U. Maraseni T. Apan A. Devkota L. P. (2023). Rationalizing donations and subsidies: energy ecosystem development for sustainable renewable energy transition in Nepal. Energy Policy177:113570. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113570

15

Blazquez J. Fuentes R. Manzano B. (2020). On some economic principles of the energy transition. Energy Policy147:111807. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111807

16

Blechinger P. Cader C. Bertheau P. Huyskens H. Seguin R. Breyer C. (2016). Global analysis of the techno-economic potential of renewable energy hybrid systems on small islands. Energy Policy98, 674–687. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.043

17

Cantarero M. M. V. (2020). Of renewable energy, energy democracy, and sustainable development: a roadmap to accelerate the energy transition in developing countries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci.70:101716. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101716

18

Chatterjee S. Roy J. Mukherjee A. Lugovoy O. Debsarkar A. (2024). Power sector transition plan of a coal-rich region in India with high-resolution spatio-temporal data based model. Energy Sustain. Dev.83:101560. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2024.101560

19

Chirambo D. (2024). Strategies for promoting climate change transparency and inclusive growth through south-south climate change cooperation. Environ. Dev. Sustain.22, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10668-024-05198-w

20

Chu S. Majumdar A. (2012). Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature488, 294–303. doi: 10.1038/nature11475,

21

CPI (2020). Climate Policy Initiative. Available online at: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/2020-2/

22

Clulow Z. Reiner D. M. (2022). Democracy, economic development and low-carbon energy: when and why does democratization promote energy transition?Sustainability14:3213. doi: 10.3390/su142013213

23

D’Orazio P. Pham A. D. (2025). Evaluating climate-related financial policies’ impact on decarbonization with machine learning methods. Sci. Rep.15:1694. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-85127-7,

24

Daszkiewicz K. (2020). Policy and regulation of energy transition. Geopolitics Global Energy Trans.12, 203–226. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-39066-2_9

25

Ferdoush M. R. Al Aziz R. Karmaker C. L. Debnath B. Limon M. H. Bari A. M. (2024). Unraveling the challenges of waste-to-energy transition in emerging economies: implications for sustainability. Innovation Green Dev.3:100121. doi: 10.1016/j.igd.2023.100121

26

Fialho D. Van Bergeijk P. A. (2017). The proliferation of developing country classifications. J. Dev. Stud.53, 99–115. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2016.1178383

27

Geels F. W. Sovacool B. K. Schwanen T. Sorrell S. (2017). Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonization. Science357, 1242–1244. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3760,

28

Gimba O. J. Alhassan A. Ozdeser H. Ghardallou W. Seraj M. Usman O. (2023). Towards low carbon and sustainable environment: does income inequality mitigate ecological footprints in Sub-Saharan Africa?Environment, Development and Sustainability25, 10425–10445. doi: 10.1007/s10668-023-03580-8

29

Gusenbauer M. Haddaway N. R. (2020). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods11, 181–217. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1378

30

Hydrogen Council (2020). Path to hydrogen competitiveness A cost perspective. Available online at: https://hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Path-to-Hydrogen-Competitiveness_Full-Study-1.pdf

31

International Energy Agency (2021). World Energy Outlook 2021. Available online at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/4ed140c1-c3f3-4fd9-acae-789a4e14a23c/WorldEnergyOutlook2021.pdf

32

IEA (2022). World Energy Outlook 2022. IEA. Available online at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/830fe099-5530-48f2-a7c1-11f35d510983/WorldEnergyOutlook2022.pdf

33

IEA (2023). World Energy Outlook 2023. Available online at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/86ede39e-4436-42d7-ba2a-edf61467e070/WorldEnergyOutlook2023.pdf

34

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) (2022). Renewable energy statistics 2022 statistiques d’énergie renouvelable 2022 estadísticas de energía renovable 2022. Available online at: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2022/Jul/IRENA_Renewable_energy_statistics_2022.pdf

35

Karanfil F. Omgba L. D. (2019). Do the IMF’S structural adjustment programs help reduce energy consumption and carbon intensity? Evidence from developing countries. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn.49, 312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2018.11.008

36

Kartal M. T. (2022). The role of consumption of energy, fossil sources, nuclear energy, and renewable energy on environmental degradation in top-five carbon producing countries. Renew. Energy184, 871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.12.022

37

Kaygusuz K. (2012). Energy for sustainable development: a case of developing countries. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.16, 1116–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2011.11.013

38

Khalfaoui H. Guenichi H. Nabli M. A. Belghouthi H. E. Guesmi M. (2025). The threshold effect of energy transition on CO2 emissions and physical climate risk nexus: a novel perspective. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. doi: 10.1108/SASBE-09-2024-0347

39

Li K. Tan X. Yan Y. Jiang D. Qi S. (2022). Directing energy transition toward decarbonization: the China story. Energy261:124934. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2022.124934

40

Li R. Xin Y. Sotnyk I. Kubatko O. Almashaqbeh I. Fedyna S. et al . (2021). Energy poverty and energy efficiency in emerging economies. Int. J. Environ. Pollut.69, 1–21. doi: 10.1504/IJEP.2021.125188

41

Markard J. Rosenbloom D. (2022). “Phases of the net-zero energy transition and strategies to achieve it” in Routledge handbook of energy transitions. ed. AraújoK. (London: Routledge), 102–123.

42

Matthäus D. Mehling M. (2020). De-risking renewable energy investments in developing countries: a multilateral guarantee mechanism. Joule4, 2627–2645. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2020.10.011

43

Mbazima S. J. Masekameni M. D. Mmereki D. (2022). Waste-to-energy in a developing country: the state of landfill gas to energy in the Republic of South Africa. Energy Explor. Exploit.40, 1287–1312. doi: 10.1177/01445987221084376

44

Menon S. Jain K. (2021). Blockchain technology for transparency in agri-food supply chain: Use cases, limitations, and future directions. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management71, 106–120. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2021.3110903

45

Medjo Nouadje B. A. Kelly E. Tonsie Djiela R. H. Tiam Kapen P. Tchuen G. Tchinda R. (2024). Chad’s wind energy potential: an assessment of Weibull parameters using thirteen numerical methods for a sustainable development. IJAE45:2276119.

46

Methley A. M. Campbell S. Chew-Graham C. McNally R. Cheraghi-Sohi S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res.14, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

47

Minaya P. E. Avella L. Trespalacios J. A. (2024). Synthesizing three decades of digital servitization: a systematic literature review and conceptual framework proposal. Serv. Bus.18, 193–222. doi: 10.1007/s11628-024-00559-x

48

Mongeon P. Paul-Hus A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics106, 213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

49

Monstadt J. (2007). Urban governance and the transition of energy systems: institutional change and shifting energy and climate policies in Berlin. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res.31, 326–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00725.x

50

Montagna A. F. Cafaro D. C. Grossmann I. E. Ozen O. Shao Y. Zhang T. et al . (2023). Surface facility optimization for combined shale oil and gas development strategies. Optim. Eng.24, 2321–2355. doi: 10.1007/s11081-022-09775-8

51

Nasir M. H. Wen J. Nassani A. A. Haffar M. Igharo A. E. Musibau H. O. et al . (2022). Energy security and energy poverty in emerging economies: a step towards sustainable energy efficiency. Front. Energy Res.10:834614. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2022.834614

52

Newell P. Srivastava S. Naess L. O. Torres Contreras G. A. Price R. (2021). Toward transformative climate justice: An emerging research agenda. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change12:e733. doi: 10.1002/wcc.733

53

Nhamo L. Rwizi L. Mpandeli S. Botai J. Magidi J. Tazvinga H. et al . (2021). Urban nexus and transformative pathways towards a resilient Gauteng City-Region, South Africa. Cities116:103266. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2021.103266

54

Noorollahi Y. Zahedi R. Ahmadi E. Khaledi A. (2025). Low carbon solar-based sustainable energy system planning for residential buildings. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.207:114942. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2024.114942

55

Ockwell D. Byrne R. (2016). Sustainable energy for all: Innovation, technology and pro-poor green transformations: Routledge.

56

Pachauri S. van Ruijven B. J. Nagai Y. Riahi K. van Vuuren D. P. Brew-Hammond A. et al . (2013). Pathways to achieve universal household access to modern energy by 2030. Environ. Res. Lett8:024015. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024015

57

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al . (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

58

Parums D. V. (2021). Review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, and the updated preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. Med Sci Monit27, e934475–e934471. doi: 10.12659/MSM.934475

59

Plazas-Niño F. A. Ortiz-Pimiento N. R. Montes-Páez E. G. (2022). National energy system optimization modelling for decarbonization pathways analysis: a systematic literature review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.162:112406. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112406

60

Pokubo D. Pepple D. G. Al-Habaibeh A. (2024). Towards an understanding of household renewable energy transitions. J. Innov. Knowl.9:100521. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2024.100521

61

Rabbi M. F. Popp J. Máté D. Kovács S. (2022). Energy security and energy transition to achieve carbon neutrality. Energies15:8126. doi: 10.3390/en15218126

62

Rahman A. Farrok O. Haque M. M. (2022). Environmental impact of renewable energy source based electrical power plants: solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, tidal, ocean, and osmotic. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.161:112279. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112279

63

Reddy B. S. (2015). Access to modern energy services: an economic and policy framework. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.47, 198–212. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.058

64

Rehan M. A. (2024). Optimization of grid-connected hybrid renewable energy system for the educational institutes in Pakistan. E-Prime – Adv. Electr. Eng. Electr. Energy10:100781. doi: 10.1016/j.prime.2024.100781

65

Riahi K. Van Vuuren D. P. Kriegler E. Edmonds J. O’neill B. C. Fujimori S. et al . (2017). The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Global environmental change42, 153–168.

66

Sadik-Zada E. R. (2021). Political economy of green hydrogen rollout: a global perspective. Sustainability13:464. doi: 10.3390/su132313464

67

Shankar A. V. Quinn A. K. Dickinson K. L. Williams K. N. Masera O. Charron D. et al . (2020). Everybody stacks: lessons from household energy case studies to inform design principles for clean energy transitions. Energy Policy141:111468. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111468,

68

Shittu I. Saqib A. Abdul Latiff A. R. Baharudin S. A. (2024). Energy subsidies and energy access in developing countries: does institutional quality matter?SAGE Open14:21582440241271118. doi: 10.1177/21582440241271118

69

Slimani J. Kadrani A. El Harraki I. Ezzahid E. (2024). Towards a sustainable energy future: modeling Morocco’s transition to renewable power with enhanced OSeMOSYS model. Energy Convers. Manag.317:118857. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118857

70

Sovacool B. K. (2016). How long will it take? Conceptualizing the temporal dynamics of energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci.13, 202–215. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.020

71

Sovacool B. K. (2017). Contested visions of sustainability: socio-technical imaginaries and the co-production of energy policy in the United States. Soc. Stud. Sci.47, 867–897. doi: 10.1177/0306312717725767

72

Superchi F. Mati A. Carcasci C. Bianchini A. (2023). Techno-economic analysis of wind-powered green hydrogen production to facilitate the decarbonization of hard-to-abate sectors: a case study on steelmaking. Appl. Energy342:121198. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121198

73

Swilling M. Nygaard I. Kruger W. Wlokas H. Jhetam T. Davies M. et al . (2022). Linking the energy transition and economic development: a framework for analysis of energy transitions in the global south. Energy Res. Soc. Sci.90:102567. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2022.102567

74

Telli A. Erat S. Demir B. (2021). Comparison of energy transition of Turkey and Germany: energy policy, strengths/weaknesses and targets. Clean Techn. Environ. Policy23, 413–427. doi: 10.1007/s10098-020-01950-8

75

Ubaydullah M. Kakinaka M. (2025). Green finance and renewable energy mix: evidence from emerging countries. Energy Environ. doi: 10.1177/0958305X251343059

76

Vázquez S. T. Sumner A. (2012). Beyond low and middle income countries: what if there were five clusters of developing countries?IDS Work. Pap.2012, 1–40. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-0209.2012.00404.x

77

Wang Y. Wang R. Tanaka K. Ciais P. Penuelas J. Balkanski Y. et al . (2023). Accelerating the energy transition towards photovoltaic and wind in China. Nature619, 761–767. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06180-8

78

World Bank (2022). World Development Report 2022: FINANCE for an Equitable Recovery. London: World Bank. Avaialble online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2022

79

World Bank (2023). Annual Report. London: World Bank. Avaialble online at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/e0f016c369ef94f87dec9bcb22a80dc7-0330212023/original/Annual-Report-2023.pdf

80

Zhang M. Liu R. Sun H. (2025). Achieving carbon-neutral economies through circular economy, digitalization, and energy transition. Sci. Rep.15:13779. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-97810-w,

Summary

Keywords

energy transition, decarbonization, developing economies, renewable energy policy, systematic literature review

Citation

Joshi S, Sharma M, Kumar A, Joshi T, Johri A and Alfehaid M (2025) Sustainable energy transition towards decarbonization among developing countries: a systematic literature review. Front. Sustain. 6:1641299. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1641299

Received

04 June 2025

Accepted

30 September 2025

Published

10 December 2025

Volume

6 - 2025

Edited by

Long Zhang, Tianjin University of Technology, China

Reviewed by

Denzel Christopher Makepa, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe

Olaoluwa Aasa, Ardhi University, Tanzania

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Joshi, Sharma, Kumar, Joshi, Johri and Alfehaid.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sudhanshu Joshi, sudhanshujoshi@doonuniversity.ac.in

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.