- Sustainable Manufacturing Systems Centre, Cranfield University, Cranfield, United Kingdom

Introduction: Limited research and knowledge have tackled the facilitators and hindrances contributing to the integration of circular economy (CE) and renewable energy (RE) in the manufacturing sector. The primary goal of the current investigation is to build a holistic system that explains why and how manufacturers adopt and implement CE and RE integrations.

Methods: The analysis utilized a mixed-methods research design that began with reviewing 107 peer-reviewed articles published between 2018 and 2023 and soliciting 10 experts' opinions through two focus group sessions held in 2024 with stakeholders in the manufacturing sector. The review and focus groups generated a list of 22 facilitators and barriers distributed across six themes: (a) regulations, (b) institutions, (c) stakeholders, (d) finance and economics, (e) infrastructure, and (f) technology. The 22 factors informed the construction of the system model using causal loop diagram (CLD).

Results: The analysis produced an integration system comprised of 11 feedback loops, indicating the intersectionality and dynamism of CE and RE integration. Network analysis demonstrated that strong government support, technical research and development, human capital technology programs, consultancy services, and cost were the most influential factors in the integration model.

Discussion: The present analysis contributes to the ongoing debate on how CE and RE are integrated into manufacturing facilities to decrease waste at all levels.

1 Introduction

Waste refers to undesirable material generated throughout production or after consumption (Zhang et al., 2022). Manufacturers, governments, and organizations all struggle in addressing waste (Guo and Chen, 2022). In 2024, The United Nations Environment Program report concluded that the world produced 1.05 billion metric tons of food waste (United Nations Environment Programme, 2024). Ruiz (2024) suggested that the world generates about 92 million tons of textiles waste a year.

The United Nations Institute for Training and Research stated that 22% of the 62 million tons of electronic waste generated in 2022 went through recycling or reuse processes (United Nations Institute for Training Research, 2024). Waste has seriously damaged the environment (Liu et al., 2021). For instance, marine life in oceans suffered in numerous ways because of the 11 million tons of plastics disposed of them annually (Dey et al., 2024). Food waste alone accounts for approximately 10% of greenhouse gasses emissions every year contributing to global warming (Dey et al., 2024; Waste Resources Action Programme, 2023).

Circular economy (CE) offers one of the practical solutions to the waste problem facing humanity today (United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 2024; Yang et al., 2023). CE is a paradigm shift from the end-of-life concept to the regenerative system of reducing, reusing, recycling, and recapturing of resources throughout all prediction and consumption phases of products (Yang et al., 2023). CE manifests in a variety of forms in the manufacturing sector including industrial symbiosis, recycling facilities, reverse logistics operations, environmental design protocols, green suppliers' selection, and many representations of the 4Rs guiding the implementation of CE (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and Recover) (Belhadi et al., 2022; Sanjaya and Abbas, 2023; Ünal and Shao, 2019; Wrålsen and O'Born, 2023).

One of the increasingly adopted manifestations of CE in the manufacturing sector is the use of renewable energy (Mutezo and Mulopo, 2021; Niyommaneerat et al., 2023). Integration of CE practices and renewable energy minimizes the environmental impact of waste (Khan et al., 2022; Niyommaneerat et al., 2023). Likewise, integration reduces the carbon footprint of operations through innovative measures such as the use of electric vehicles in reverse logistics (Azadnia et al., 2021; Richnák and Gubová, 2021). Powering manufacturing processes with solar and wind energy not only decreases utility bills or usage but also facilitates the adoption of new green practices such as waste-to-energy in-house operations (Haleem et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2018; Chowdhury et al., 2020; Duran et al., 2022).

While the literature on CE and renewable energy integration is still emerging, the conventional wisdom points to the colossal benefits for improving and refining the integration to maximize gains on all levels (Islam et al., 2021a; Mutezo and Mulopo, 2021). The literature on CE practices and renewable energy integration suffers from a series of problems.

First, much of the writing considers a single practice, as well as one renewable energy source in a particular operation resulting in a large number of case studies lacking theoretical or conceptual structure (Niyommaneerat et al., 2023). Second, the integration of literature is bereft from clear conceptual frameworks that explain how such integration originates, evolves, develops, and matures given the complex environments surrounding the manufacturing environment (Mulvaney et al., 2021). Third, most studies documenting the success story of a manufacturer integrating CE practices and renewable energy consider one domain of key factors while ignoring others in the system (Hassan et al., 2023; Mendoza et al., 2022). For instance, a study class is concerned with institutional and management variables without paying adequate attention to technological trends or regulatory environments making the inferences questionable or the findings impractical for real-world applications (Buchmann-Duck and Beazley, 2020; D'Amato and Korhonen, 2021; Mutezo and Mulopo, 2021; Mendoza et al., 2022).

A few studies addressed the integration of circular economy and renewable energy to achieve sustainable development. Klemeš et al. (2023) argued that updating energy infrastructures and technology requirements is the most important facilitator leading to integration. In a different analysis, Safarzynska et al. (2023) argued that investments in human capital, research and development and training programs constitute the primary drivers of integration for circular economy and renewable energy.

Mutezo and Mulopo, 2021 encouraged future researchers to perform more holistic reviews considering more than a single domain of factors contributing to the integration of CE with RE in emerging economies. The reasoning behind such a recommendation is that most researchers target one theme of variables like technological requirements while ignoring other important facilities such as cultural or organizational factors affecting the integration framework (Onyeka and Emeka, 2025).

The primary aim of the paper is to design a system model that explains manufacturers' integration of CE practices and renewable energy. A secondary goal is to uncover the salient facilitators and barriers within the literature and among experts that define the integration system. Thus, a thorough review of the recent literature, as well as two focus groups provided the list of important factors informing the system model. The factors extracted from the literature and experts provided the input for the system modeling analysis (i.e., causal loop diagrams and network analysis).

After reviewing 107 papers and meetings with 10 experts, a list of 22 facilitators and barriers informed the underlying process of how manufactures adopt and implement integration of CE practices and renewable energy sources. The 22 factors represent 6 distinct themes (a) regulations, (b) institutions, (c) stakeholders, (d) finance and economics, (e) infrastructure, and (f) technology. The CLD analysis generated 11 feedback loops structuring manufacturers' decisions regarding integration. Based on the network analysis, strong government support, technical research and development, human capital technology programs, consultancy services, and cost appeared to be the most influential factors in the system.

The current manuscript offers several contributions to scholars and manufacturers interested in circular economy integration with renewable energy. First, the paper orients the attention of practitioners to 22 key variables distributed on 6 themes when initiating plans of integration. Prior to the findings of the current review, no manufacturer interested in integrating CE and RE did not have a ready clear-cut map similar to the CLD presentation in the current manuscript. Second, scholars and manufacturers have access to how the 22 key variables interact with each other according to real-world case studies from the literature and a number of experts in the field.

Previously, manufacturers knew how one variable could influence another or two but did not have access to a more holistic picture similar to the 11 feedback loops. Government stakeholders interested in making manufacturing leaner and greener could focus their attention on (a) regulations, (b) institutions, (c) stakeholders, (d) finance and economics, (e) infrastructure, and (f) technology as the network analysis indicated in the analysis. Fourth, future researchers interested in conducting systematic reviews or comprehensive studies on CE and RE are encouraged to utilize a number of qualitative and quantitative methods similar to the methodology of the present analysis.

2 Materials and methods

A mixed-methods research design guided the analysis. Systematic literature review and focus group methods were used to construct a table of facilitators and barriers affecting the integration of circular economy and renewable energy. The final table (i.e., Table 2) representing shared facilitators and barriers was used as the data for constructing the causal loop diagram and network analysis output. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize a few key trends in the systematic review and focus groups data.

2.1 Research design

The present investigation employs mixed-methods research design to understand the relationships between the facilitators and barriers of circular economy and renewable energy integration in the manufacturing sector (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). The mixed methods used in the analysis featured a few qualitative data analysis techniques, as well as a number of quantitative procedures. The qualitative methods included causal loop diagrams (CLDs), networks, and focus groups (Binder et al., 2004; Lamé, 2019; McKim, 2017). The quantitative methodologies entailed the use of frequencies and descriptive statistical techniques to summarize data. Prior to the use of the mixed methods, a comprehensive literature review and detailed focus groups guided the selection of variables that constituted the input for both the qualitative and quantitative data.

Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) informed part of the qualitative analysis aiming to summarize dynamics underlying variables leading to the integration of circular economy and renewable energy (Lin et al., 2020; Uleman et al., 2024). The CLDs were the products of an extensive literature review on the global scholarship investigating integration trends, as well as in-depth focus groups with key stakeholders in the manufacturing sector. Note that CLDs provide maps of dynamic relationships summarizing the system (Crielaard et al., 2024). In this investigation, the system is the drivers of CE and renewable energy integration in the manufacturing sector.

CLDs offer an appropriate method for the current manuscript because the technique enables the researchers to build visual systems showcasing relationships among key variables. The purpose of the research is to understand how CE and RE integration plays out in the manufacturing sector. CLD allows the researchers to identify key variables in the system and map simplified interactions in an intuitive manner communicating complex information in simplified graphs. Additionally, CLDs present readers with how each variable interacts with other variables in loops demonstrating sub-systems within the larger system of variables explaining the phenomenon of interest, CE and RE integrations within the manufacturing sector. Thus, CLDs were selected by the authors to conduct the present analysis as the appropriate modeling technique.

Expert opinions provided real-world data that assisted in verifying evidence extracted from the extant literature (Picardi and Masick, 2013). Network analysis also provided another method enriching the understanding between variables leading to integration within the manufacturing sector (Borgatti et al., 2009). Descriptive statistics based on the quantitative content analysis of the focus group information provided the quantitative phase of the mixed-methods study.

2.2 Systematic literature review

A comprehensive systematic literature review identifying the barriers and facilitators leading to the integration of circular economy and renewable energy in manufacturing was conducted. A total of 107 peer-reviewed papers published in 60 different journals were extracted and analyzed by two independent authors autonomously. The papers originated from 41 countries covering more than 10 industrial domains. To retrieve the facilitators and barriers, the two researchers thoroughly read every paper listing the factors affecting integration (Kitchenham et al., 2009; Kraus et al., 2020).

Two databases provided the peer-reviewed articles for the research. The databases were Web of Science and Scopus. Both databases feature a great number of journals publishing papers on circular economy practices as well as renewable energy within the manufacturing sector. Three keywords combinations constituted the search strategy in this research. The keywords combinations were (1) “renewable energy” AND “circular economy” AND “manufacturing”, (2) “sustainable development” AND “circular economy” AND “manufacturing”, (3) “sustainability” AND “circular economy” AND “manufacturing.” Figure 1 presents the total number of studies included in this research after the elimination of the irrelevant articles identified in the search process.

The total of all initially identified studies was 5210. There were 3226 duplicates among them. After eliminating these records, the total number of screened studies was 1984. The primary criteria for eligibility were the application of at least one circular economy practice as well as a renewable energy source within the manufacturing sector. Many studies did not feature a concrete implementation of CE practices or RE sources which rendered them ineligible for inclusion in the review. According to these studies, 1,012 of them were eliminated due to being irrelevant, thus, the number of records sought for retrieval was 972. Out of these studies, 236 of them were not retrieved because they were inaccessible. The remaining number studied was 736. Many of these studies lacked clear integration or were repeated as well as not used validated concepts, resulting in 107 studies included for the review.

For each included article, a thorough reading by each author identified the list of facilitators and barriers facing CE and RE integration manufacturing. Furthermore, each author examined the articles to identify explicit links between facilitators and barriers. Each author prepared a separate list of facilitators, barriers as well as their relationships. Three separate sessions were convened to discuss the findings of the authors. The final list of facilitators and barriers as well as their relationships was prepared after the conclusion of the third session with the unanimous agreement of all authors.

2.3 Focus groups with expert opinions

Two focus groups with stakeholders in the manufacturing sector possessing real-world expertise with circular economy practices application and renewable energy implementation provided the information to validate the literature based on CLD. Two distinct focus group sessions were held with five individuals each. One focus group included manufacturing facilities owners and operations managers while the other focus group included academic and government experts on the integration of circular economy and renewable energy. Both focus group sessions were held in Saudi Arabia in 2024 face-to-face.

The Cranfield University Research Ethics committee approved the research (i.e., CURES/17446/2022). All procedures followed the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki ethics protocols. Informed consent was obtained in writing prior to the commencement of the focus groups. The language of the focus groups was Arabic because participants were all working in Saudi Arabia.

Ten experts were selected for the entire focus groups portion of the research to satisfy the principle of saturation in qualitative research (Hennink et al., 2019). Saturation refers to the sufficiency of information to cover the universe of knowledge on a particular subject (Guest et al., 2017). In other words, does the inclusion of 10 experts lead to saturation? Objectively, there is no magic number that leads to such an unobserved state of knowledge (Morgan, 1997). Nevertheless, researchers recommended different numbers of participants where some concluded that less than 10 in new topics are enough while others preferred more than 15 individuals (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021; Guest et al., 2017). Given the novelty of the area under study and limited real-world manifestations of circular economy integration with renewable energy, 10 individuals who possess expertise on the subject were sufficient to provide valuable insights. Relatedly, each focus group featured five individuals consistent with the focus group number of participants recommendations in the literature (Hennink et al., 2019). Five individuals have the opportunity to offer in-depth information assisting the researchers in identifying systems of relationships (Hennink et al., 2019).

Saturation refers to the fulfillment of potential answers from a set of participants in qualitative research. Once answers begin to be repetitive, researchers achieve a degree of saturation. Repeated studies in many fields concluded that 9–20 participants provided sufficient information satisfying saturation especially in niche subjects (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022; Wutich et al., 2024). This analysis used 10 participants to be consistent with the qualitative research recommendations fulfilling saturation.

Each focus group lasted about 2 h. The sessions moderator was one of the researchers who is from Saudi Arabia and worked in the energy sector for over 10 years. A facilitator assisted the moderator throughout the session by taking notes and recording responses. Note that each participant signed a consent form allowing recording. The focus group sessions covered the same style, as well as topics.

Semi-structured focus groups guided the gathering of expert opinions on the integration of circular economy and renewable energy. Each focus group featured six main questions (see Table 1 for the list of the questions) that structured the answers of respondents. The moderator asked every participant to share an opinion or experience on every question. Discussions between participants ensued based on the responses provided by their peers. Such a style invoked illustrations and examples clarifying some of the points voiced throughout the sessions. Additionally, every participant offered a note on each question asked providing researchers with further information that helped in validating the CLD.

2.4 Causal loop diagram development

CLDs are visual representations of systems (Haraldsson, 2004). A CLD presents an image of various components of a system depicting relationships among the variables comprising the entire system (Barbrook-Johnson and Penn, 2022; Crielaard et al., 2024). CLDs are system design or thinking techniques that simplify a given phenomenon (Dhirasasna and Sahin, 2019). In manufacturing and systems engineering, authors have used CLDs to present how variables are interconnected to construct a specific system underlying a trend or behavior (Aikenhead et al., 2015). In the present research, CLDs were used to represent the variables facilitating and hindering the integration of circular economy and renewable energy.

A CLD presents a set of variables underlying the system in question. The variables are connected to each other using arrows. Each arrow is equivalent to a correlation (Sherwood, 2011). On each arrow, the direction of the correlation is indicated with either positive (+) or negative (–) sign. The sign represents the direction of the relationship. Arrows are single headed representing one-directional orientation connecting one variable to another (Proust and Newell, 2020)

Loops form when a series of arrows return to the point of origin (Dhirasasna and Sahin, 2019). A sequence of relationships oftentimes represents a circular system, which is referred to as a feedback loop in CLD's literature (Proust and Newell, 2020). Feedback loops could be reinforcing denoted by (R) or Balancing represented by (B). Reinforcing loops are characterized by similar signs connecting the variables while balancing loops feature different signs within the loop (Sherwood, 2011). One rule that helps researchers identify the type of loops is counting the number of negative signs (-). If the number of negative signs is odd, then the loop is balancing and if they are even, then the loop is reinforcing (Uleman et al., 2024).

2.5 Network analysis

To further validate the CLDs, network analysis provided a way for testing the structure and dynamics of constructed CLDs. Network analysis supply researchers with real-world representations of systems similar to CLDs methods (Crielaard et al., 2024; Knoke and Yang, 2008). Network analysis helps identify central or key variables in the system (Knoke and Yang, 2008). Such centrality tests assist in verifying whether variables with more arrows in CLDs are truly essential in the system or not.

Unlike CLDs, Network Analysis allows the inspection of key variables to the system. For instance, network maps permit researchers to estimate radiality scores indicating the centrality of each variable in the system (Khameneh et al., 2024). Further, Network Analysis demonstrates peripheral variables, as well as central factors, which is a different display from the CLDs that tend to showcase loops on a single canvas.

2.6 Descriptive quantitative analysis

A number of descriptive statistical procedures guided the analysis of the reviewed literature and experts' opinions. On the one hand, frequency distributions summarized each factor's occurrence in the literature, as well as among experts. On the other hand, bar charts and pie charts described the frequency of themes underlying manufacturers' decisions to adopt and implement CE practices with renewable energy.

2.7 Qualitative thematic analysis

A thematic analysis of the systematic review and focus group qualitative data guided this investigation. Brown and Clarke's (2006) six steps provided the authors with a comprehensive way of performing the thematic analysis. The six steps were: (a) familiarizing yourself with your data, (b) generating initial codes, (c) searching for themes, (d) reviewing themes, (e) Defining and naming themes, and (f) producing the report. Each author familiarized himself with the data independently from other authors by reading the final list of facilitators and barriers as well as their links more than once. Each author generated a list of themes based on the facilitators and barriers independently. Note that each facilitator or barrier constituted a different code. A code is an idea that is part of a larger theme. The authors met once to finalize the labels of the final themes reached to summarize the qualitative data prior to writing up the report.

To enhance credibility, each author independently analyzed the information extracted from the reviewed articles and the focus group responses. As indicated earlier, agreement was reached unanimously in joint sessions between the authors that resolved any differences. Such a process improved the credibility of the coding procedures, as well as the output of the analysis.

3 Results

The results section begins with the descriptive analysis of the literature, as well as experts. Then, based on the identified data, the CLD map presents the system model explaining the integration decision. Within the CLD's section, a comprehensive overview of all feedback loops within the system is detailed. Following the CLD analysis, Network Analysis output demonstrates the radiality and influence of each factor within the system.

3.1 Systematic review and focus groups results

Figure 2 presents the most commonly mentioned facilitators and barriers in the literature, as well as the focus group discussions concerning circular economy practices integration with renewable energy sources. A total of 22 barriers and facilitators emerged as important factors affecting integration. The figure shows the frequency of each factor with respect to the number of studies and experts mentioning it. Note that strong government support was highlighted by all 10 experts in the focus groups and 82 studies. The least frequent factor in the literature was policy variance with 22 papers referring to it. Note that a factor was considered common if at least 20 articles mentioned it, and two experts directly referred to it.

Table 2 presents a heuristic distribution of facilitators and barriers based on six themes connecting the factors. The six themes were (a) regulations, (b) institutions, (c) stakeholders, (d) finance and economics, (e) infrastructure, and (f) technology. Each theme represents at least three related factors. The table also demonstrates how many of each factor, as well as its theme, were mentioned by the experts, as well as authors in the literature.

To clarify some terminology in the labeling of the facilitators and barriers, a number of terms have been defined as follows. Cost refers to the financial investment and monetary resources required to integrate circular economy with renewable energy. Collaboration refers to the exchange of resources, knowledge and manpower between institutions aiming to facilitate the integration of circular economy with renewable energy. Resistance to change refers to the refusal of managers and employees to adopt new training or workplace practices conducive to the integration of CE and RE.

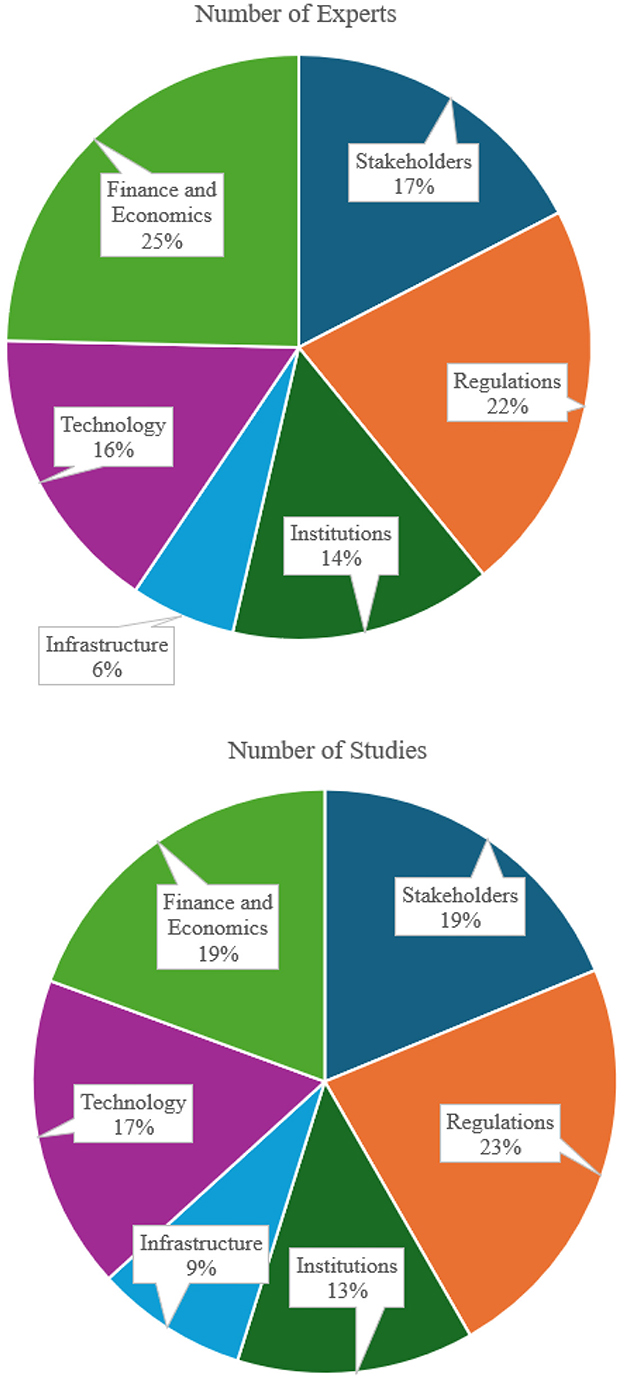

Figure 3 shows the salient of themes in literature, as well as the views of experts. The pie charts indicate the percentage of each theme given all mentions with respect to the number of studies and experts. With regards to experts, financial and economic factors constituted 25% of all facilitators and barriers mentioned. Regulation factors comprised 22% of all mentions. The least emphasized theme was infrastructure with a total of 6% mentions.

In reference to the literature, regulation factors assumed the highest frequency with 23% out of all mentions. Financial and economic factors, as well as stakeholders' variables comprised 19% each of the total mentions of facilitators and barriers in the literature. Infrastructure factors featured the least emphasized category of factors with a 9% rate of mentions considering all themes.

3.2 Causal loop diagram of circular economy and renewable energy integration

A total of 11 feedback loops with 22 variables define the underlying system explaining the integration of circular economy and renewable energy in manufacturing. There are six reinforcing loops and five balancing loops. Figure 4 represents the underlying causal loop diagram explaining the relationships between circular economy and renewable energy integration facilitators and barriers. Note that some variables are present in more than a subsystem such as strong government support that appeared in institutional, as well as financial realms. Additionally, some variables reflect more interconnection compared to others given their varied consequences such as resistance to change. There are six subsystems structuring the variables in the CLD. The integration of renewable energy sources with circular economy principles represents a fundamental shift in manufacturing paradigms (Ali et al., 2022; Alshammari, 2020; Borowski, 2022; Finn et al., 2020; Ishaq et al., 2022; Yildizbasi, 2021).

The first reinforcing loop (R1) reflects the institutional subsystem (Green Color) in the CLD diagram. The loop begins with manufacturers' innate nature for resisting change. Such resistance generates a slow and inconsistent environment for strong government support given industries and policy divisions over the type and extent of Demir and Aktan (2016), Evans and Britt (2023), and (Ritchie, 2014). Once government support is offered to manufacturers for integration purposes, collaboration among various stakeholders in the sector increases (Wanna, 2008). In turn such collaboration clashes with continued resistance for change or accepting the type of government support (Evans and Britt, 2023; Xue et al., 2024). Such a loop represents the primary institutional subsystem (Bui et al., 2022; Janik et al., 2020; Lim et al., 2023; Ogunmakinde et al., 2022; Pukšec et al., 2019; Ratner et al., 2020; Zvirgzdins and Linkevics, 2020).

The first balancing loop (B1) represents a larger variation of R1 with the addition of 2 variables: duplicate efforts and strong regulations. Like R1, B1 begins with the negative effect of resistance to change on strong government support. Similarly, the loop also transitions from government support to its positive effect on collaboration. Once collaboration among stakeholders becomes institutionalized in the forms of knowledge sharing and partnerships, strong government regulations become more likely (Demir and Aktan, 2016; Evans and Britt, 2023; Ritchie, 2014). Regulations negatively affect manufacturers' duplicate efforts in integration through a variety of channels such as the provision of shared resources or access to digital or physical infrastructures (Mutezo and Mulopo, 2021). Duplicate efforts lead manufacturers to lower resistance to change patterns since owners and operators imitate each other's endeavors giving a sense of perceived assurance of following industry patterns (Kumar et al., 2019).

The second reinforcing loop features the intersection of institutional and financial support (red color) (R2). The loop begins with government support that translates into further fiscal incentives boosting CE practices integration with renewable energy sources (Bolger and Doyon, 2019; Wasserbaur et al., 2022). The presence of fiscal incentives leads to legislative public funding backing for integration initiatives, especially public-private partnerships. In turn, public funding leads to more government support (Mutezo and Mulopo, 2021; Onder and Abduljaber, 2025a).

The second balancing loop (B2) concerns the intersection of institutional variables and regulatory measures (yellow color in the lower left corner). The loop starts with manufacturers' duplicate efforts of integrating CE practices with renewable energy sources leading to fragmented ad hoc set of regulations (Klemeš et al., 2023, 2019). The need for strong regulations translates into the presence of inconsistent standards in the integration process. Inconsistent standards are associated with pervasive policy variance in governing integration initiatives. When policy variance exists in markets, actors duplicate efforts to achieve the same outcomes. Such an environment is characterized with uncertainty leading to each actor attempting to accomplish integration on its own resulting in doing similar or the same endeavors by many actors within a single industry (Chishti et al., 2023).

The loops were derived based on the inferences made by authors in the literature and experts in the focus groups. After each of the 22 key variables was identified, a reading of all included papers focused on how each variable relates to others. Each paper was read and if a relationship was identified by the researchers, it was recorded. Similarly, the focus group discussions involved direct references to relationships among the key 22 variables. Whenever a reference was made in the focus group concerning a variables interaction with others, it was recorded. The references were arranged in Table S1 showing the relationships and loops constructing the CLD.

The third reinforcing loop (R3) represents stakeholders' variables (blue color). The loop begins with consumer awareness and training that results in more collaborations and partnerships leading to integration. Public-private partnerships result from further consumer engagement generating more interactions with expert consultancy services that guide the integration process or initiatives. When consultancy services perform education and training programs, consumers' awareness about integration increases.

The fourth reinforcing loop (R4) covers the technology variables domain (purple color). The loop begins with the investment in human technology programs that lead to further use and implementation of Artificial Intelligence technology in integration initiatives. The utilization of AI applications and platforms transforms into more technology research and development (Danish and Senjyu, 2023; Shahbaz et al., 2025) Investing in R&D programs is associated with further human capital training on technology and technical systems involved in the integration process (Shahbaz et al., 2025).

The third balancing loop (B3) pertains to the regulations subsystem (yellow color in the lower left corner). The prevalent policy variance leads to the generation of inconsistent standards regulating the integration of CE practices into renewable energy. Inconsistent standards also result in lower levels of sectoral collaboration among stakeholders (Domenech and Bahn-Walkowiak, 2019; Grafström and Aasma, 2021). Lack of collaboration translates into fragmented policy initiatives generating high levels of regulatory and legislative variance (Domenech and Bahn-Walkowiak, 2019).

The fifth reinforcing loop (R5) represents an intersection between technology and stakeholders' variables. The loop begins with human capital technology investment that leads to collaborations with consultancy services (Klemeš et al., 2019). More consultancy services in turn translate into public-private partnerships. By the same token, further partnerships generate more research and development across all integration domains, specifically technology. Likewise, technical training and research improves human capital technology awareness and education (Klemeš et al., 2019; Mendoza et al., 2022).

The fourth balancing loop (B4) demonstrates the interconnectedness of public financing and cost variables. The loop begins with public financial backing generating further grants and subsidies for integration. Grants manifest into the costs spent on integration initiatives. Grants also lead to a set of private costs like matching funds for improving integration. With increasing costs dedicated to integration, uncertain return on investments decreases since the costs incurred throughout integration address uncertainty problems thereby providing more investment clarity (Aranda-Usón et al., 2019). In the case of the presence of an uncertain return on investment, fiscal incentives decrease, avoiding potential losses from integration initiatives. On the contrary, if fiscal incentives exist and are strong. Public financial backing to integration projects increases (Kandpal et al., 2024).

The fifth balancing loop (B5) represents the infrastructure variables domain. The loop begins with the lack of technical support that keeps outdated facilities without appropriate upgrades handling integration needs (Mendoza et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2015). The presence of outdated facilities testifies to the existence of limited logistics networks capable of addressing research and development needs crucial for updating physical and digital systems. Absence of digital systems also notes the lack of proper technical support necessary to address integration requirements (Pagoropoulos et al., 2017).

The sixth reinforcing loop (R6) covers the interdependence of technology and cost variables (red color). On the one hand, the absence of technical support for teams generates more grants and funding to close such a crucial gap. Evidently, grants incur further investment costs in the promotion of integration within manufacturing. The implementation of artificial intelligence lowers investment costs in the long run. Technical research and development increase the amount of technical support.

3.3 Network analysis of variable influence and interconnectivity

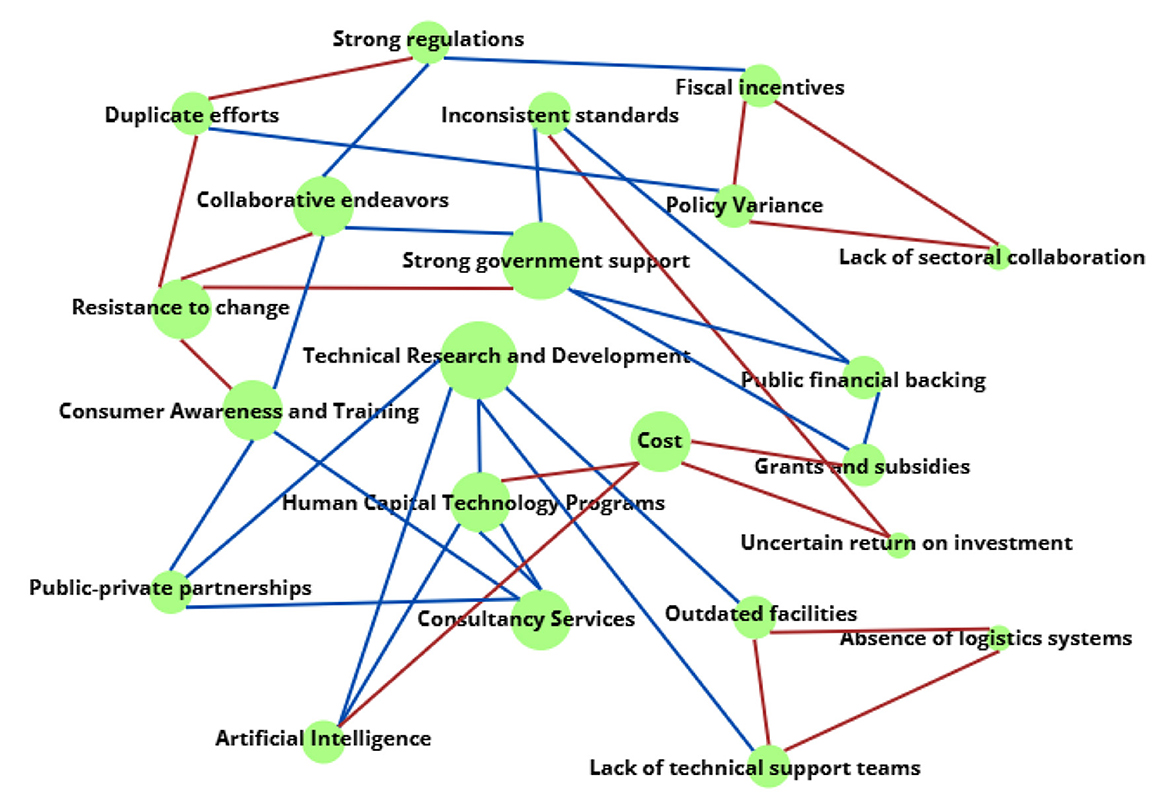

Figure 5 presents the network analysis demonstration of the circular economy practices integration process with renewable energy sources in the manufacturing sector. Unlike CLDs that showcase systems and cause-effects interconnection, network analysis diagrams demonstrate the influence of variables within systems. Networks depictions represent mathematical predictions concerning variables' effects across systems. The representations are scale-free and indicate the predictive strength of each variable within the system.

The network diagram presents variables' nodes indicating their influence (radiality). Centric nodes possess higher radiality compared to peripheral nodes. Note that the network diagram differs from the CLD visualization. Within the CLD, variables are organized in subsystems while in the network analysis, each variable predictive power is indicated by its radiality. Both pieces of information supplement each other in providing a better understanding to the circular economy practices integration into renewable energy. The most important variables in the network analysis are centrically placed including strong government support, technical research and development, human capital technology programs, consultancy services, and cost. See Table 3 for more information.

Figure 6 demonstrates the radiality (influence) of factors affecting the circular economy and renewable energy integration. Cytoscape software provided the tool for constructing the network diagram in the analysis. The network analysis generated in the program was scale-free and did not specify preprepared weights. The software generated a random structure placing the variables with more importance (influence) at the center of the diagram. An excel sheet with polarity scores and the number of connections for each facilitator or barriers or its combination constituted the input data for Cytoscape. Radiality is calculated by measuring the distance of each node from other nodes. Higher radiality scores correspond to more influence. Note that the facilitators or barriers with more connections possessed higher radiality scores. Financial and economic factors alongside regulations and stakeholders' variables appeared to be more influential compared to others. Strong regulations and costs were the most influential factors affecting integration. Infrastructure-related factors were the least influential factors.

4 Discussion

This investigation reported the importance of 22 facilitators and barriers distributed on 6 themes. The themes affecting the integration of CE practices and renewable energy sources were (a) regulations, (b) institutions, (c) stakeholders, (d) finance and economics, (e) infrastructure, and (f) technology. Among the themes, financial and economic variables, as well as regulatory factors appeared to be the most important elements influencing the integration. The CLD analysis showed the presence of loops underlying the integration system defining the relationships between the 22 variables. Noticeably, institutional and regulatory factors intersected with financial elements formulating interdependent subsystems. The network analysis concluded that strong government support, technical research and development, human capital technology programs, consultancy services, and cost possessed the highest amount of influence on integration indicated by their radiality scores.

The current investigation highlighted the dynamic interconnectedness of the subsystems leading to circular economy and renewable energy integration. A cursory examination of the network analysis (see Figure 5) suggests that regulations, institutions, financial institutions, and technology subsystems are closely related to forming a compelling force facilitating integration. Grants, fiscal incentives, and strong government support lead to investments in technological upgrades and development, which also includes human capital training, and collaboration among all actors leading to integration (Islam et al., 2021b). Such integration is positively moderated by the presence of a highly standardized and clear policy environment, as well as the presence of expert consultancy services. Thus, the analysis shows how each variable and subsystem act as a mediator and moderator simultaneously (Cho et al., 2022).

A strength of the present study is the coverage of various countries, economy types, and varying pathways to integration. On the one hand, the literature review covered all research on circular economy practices and renewable energy sources regardless of the geographic setting. On the other hand, experts came from an emerging economy, Saudi Arabia, adding a comparative element to the research. Much of the existing research in the field cover a single case or one country (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2022; Roleders et al., 2022). Further, this research surveyed manufacturing frontiers across all industries rather than concentrating on a single realm. One of the outcomes of such an approach is the production of highly complex systems leading to integration (Paul et al., 2021; Shaffril et al., 2021).

4.1 Relevance to past research

The present research demonstrated that circular economy integration into renewable energy is a complex and dynamic process transcending multiple domains of factors regardless of the manufacturing setting. Unlike prior studies that only concentrated on either technical or technology related variables affecting integration, the current investigation highlighted the significance of six distinct subsystems as the CLD map shows (see Figure 4). Not only is the integration process convoluted, but also the subsystems are interconnected leading to further interactions within the entire system. For instance, the reinforcing loops R1, R3, and R4 suggest the intrusion of one subsystem into others. Thus, any stakeholder interested in the implementation of integration needs to consider all the subsystems at play rather than a single system (Abduljaber and Onder, 2024; Al Shehri et al., 2023; Awan and Sroufe, 2022; Islam et al., 2021b; Khajuria et al., 2022; Ogunmakinde et al., 2022; Tapaninaho and Heikkinen, 2022).

Historically, much of the research on the integration of circular economy practices and renewable energy followed a siloed approach. Authors typically focused on single practice and one or two energy sources. Recycling appeared to be the most studied circular economy practice and its integration with solar, or wind energy implementation appears to be the most common integration in the manufacturing sector. One of the reasons that explains such a pattern of research is the case study design, which is common in this area of research (Abduljaber, 2018, 2020). Authors tend to study one factory or an integration episode in a specific context forcing them to concentrate on one or two practices or sources (Shahbazbegian et al., 2020). While such an approach is rewarding in providing rich information on integration, it failed to supply readers with systematic overviews of the holistic system of integration (Cho et al., 2022). Typically, one sub-system is highlighted, and others are not discussed, which presents a skewed view of the integration process (Roleders et al., 2022).

4.2 Practical implications

The integration of circular economy practices into renewable energy integration at manufacturing facilities is increasingly taking momentum among manufacturers interested in applying sustainable production and waste management models (Roleders et al., 2022; Awan and Sroufe, 2022). Most manufacturers in emerging economies like Saudi Arabia are unfamiliar with integration and how to proceed even if they are serious about implementing the concept on their operations (Abduljaber et al., 2025; Onder, 2021, 2023; Al Shehri et al., 2023). One of the practical implications of the current research is building familiarity and awareness concerning integration and its various subsystems. Manufacturers could learn about the different upgrades needed to be achieved prior to integration such as education and awareness, government funding or the necessary technology requirements (Chen et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2023, 2024; Hidalgo-Crespo et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2021; Munir et al., 2021; Onder, 2022; Onder and Abduljaber, 2025b; Trowell et al., 2020; Yousef et al., 2025). While some manufacturers may have a basic idea on one or two subsystems, they are likely oblivious to another or more subsystem(s). Thus, the present research serves as a starting point for building easy-to-follow road maps leading to interested manufacturers throughout their integration journeys.

The underlying system of circular economy practices integration with renewable energy sources highlights the tension between government's interest in enhancing sustainability and manufacturers' need to grow economically and financially (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2022). On the one hand, investing in integration is exorbitant and does not lead to immediate savings, at least for large scale manufacturers. On the other hand, integration is a long-term process that takes time to realize its sustainable and economic benefits (Mendoza et al., 2022). Thus, cost, uncertain returns on investment and funding become crucial factors within the underlying integration system (Shahbazbegian et al., 2020). Policymakers could encourage healthy integration through responsible legislative behavior. For instance, in Saudi Arabia, the government invested heavily in renewable energy public projects such as solar and wind generation sites throughout the kingdom providing affordable services to manufacturers switching energy sources (Al Shehri et al., 2023). Further, the country's leaders offered large low-interest loans for manufacturers' expansions compliant with sustainable production and logistics guidelines. The government partnered with many expert consultancy groups in the sustainability sector upgrading large scale publicly owned manufacturing structures paving the way to private actors to imitate the shift (Abduljaber et al., 2025). The collection of all such endeavors aligns with the Circular Carbon Economy paradigm (Al Shehri et al., 2023).

Policymakers could invest in research and development programs facilitating CE and RE integration (Dennison et al., 2024). On the one hand, a grants-based program could stimulate research in educational institutions with partnerships with manufacturers. On the other hand, policymakers may partner with consultancy services directly to generate a step-by-step framework to be required from new market entrants for increasing integration. Most importantly, policymakers could pass tax exemptions for businesses that implement integration with clear output.

4.3 Future research directions

One of the most echoed concerns of circular economy integration with renewable energy is cost manifested in a variety of forms such as uncertain return on investments or hefty financial commitments to upgrade technological or logistical systems (Pan et al., 2015; Islam et al., 2021a). All experts highlighted the long-term positive impact of integration on efficiency savings, however most experts indicated that becoming fully integrated is not an economically viable option at the present moment (Molano et al., 2022). Consistent with such an observation, many authors in the literature called on governments to subsidize research and development programs that facilitate integration (Shahbazbegian et al., 2020). One of the potential future research directions is the design of affordable integration patterns that help manufacturers achieve economic efficiency while improving sustainability simultaneously (Wang et al., 2022). The literature on circular economy integration with renewable energy is still at the developing stage, and documentation of success stories in the manufacturing sector are likely to increase. Future authors are urged to search for critical success narratives of integration to publicize the idea that integration could be achieved in affordable ways (Aldhafeeri and Alhazmi, 2022; Balzani, 2019; Cho et al., 2022; Dagiliene et al., 2021; Ghimire et al., 2021; Kiviranta et al., 2020; Mathur et al., 2020; Priyadarshini and Abhilash, 2020; Puntillo, 2023; Rada, 2019; Ralph, 2021; Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2022).

One of the least investigated areas in the circular economy and renewable energy integration discipline is education and training programs or initiatives (Roleders et al., 2022). Authors have neglected the present human capital aspect of integration. Little emphasis in the literature has covered existing workshops, modules, or organizational professional development programs aimed at integration awareness or growth (Stewart and Niero, 2018). Future researchers may either concentrate on formal education programs or informal knowledge sharing endeavors organizations implement to improve integration. Likewise, future researchers may focus on the curriculum of such programs documenting the various modules and content present in the programs (Awan and Sroufe, 2022).

With the proliferation of quantitative research in the integration of circular economy and renewable energy discipline, researchers are urged to heed best practices in statistical modeling. The present analysis highlighted the importance of many variables determining integration. In the name of parsimony, many researchers may choose to omit some key factors thereby constructing easy to understand or implement models. Such practice, however, runs the risk of generating biased coefficients or estimates because of errors in models' specifications or omitted variables biases (Hassan et al., 2023). Thus, quantitative researchers are recommended to fit a variety of models in a single study to compare the varying measures of strength, explanatory power or goodness of fit (Abduljaber et al., 2025; Almadhi et al., 2023; Barros et al., 2020; Ghisellini et al., 2016; Govindan, 2018; Ioannidis et al., 2023; Milousi and Souliotis, 2023; Mohajan, 2021; Onder, 2019; Pintilie, 2021; Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2023).

Future researchers may utilize longitudinal analysis following a set of manufacturers that implemented integration plans. Such a methodology allows researchers to identify common real-world facilitators and barriers overtime and across cases. Similarly, future researchers may apply agent-based modeling or participatory research to learn insider knowledge on what transpired from the point of origin when a manufacture determines investing in integration to the output, results of integration.

4.4 Limitations

The experts had limited time to share their reflections on the factors facilitating or hindering integration. Thus, they could have covered more variables if the time of the focus group sessions had been extended. Relatedly, focus group discussions are affected by the responses provided throughout the session by participants. Therefore, if the discussions within the sessions featured other topics, more or fewer variables could have emerged affecting the CLD map, network analysis or the most frequently mentioned variables (Islam et al., 2021a).

Experts highlighted a lower number of facilitators and barriers to the integration of circular economy practices into renewable energy. They also emphasized a lower number of connections among the variables compared with the overall literature. A potential explanation is the context. On the one hand, all experts came from Saudi Arabia, which is an emerging economy requiring more infrastructure, technology and human capital upgrades compared with developed economies in North America, Western Europe, and East Asia (Al Shehri et al., 2023). Further, the literature review covered a wide range of geographic areas providing more information from many contexts. Thus, when qualitative research is implemented, researchers need to be cautioned concerning the transferability of the findings in the analysis (Roleders et al., 2022).

One of the crucial limits of the present study plagues the qualitative research paradigm. Causal loop diagrams tend to be highly subjective, complex and dependent on researchers' expertise, biases, as well as reflexivity. As evident in the CLD of the present research, the underlying system of integration is highly complex and relied on experts' coverage, as well as a comprehensive review of the literature. If a different group of researchers conducted the same research, results would be slightly varying given the qualitative nature of the study. Therefore, results and inferences from the research must be considered like any other qualitative finding. Likewise, the expertise and backgrounds of experts affected the type and quality of information used to construct key elements of the analysis. If another panel of experts participated in the research, slight variations would have occurred generating differing findings. Such facts are endemic to qualitative research, and any remedy would fail to uproot their effects on the findings (Rodríguez-Antón et al., 2022; Awan and Sroufe, 2022).

One of the limitations of the analysis is that all focus group participants were from Saudi Arabia. While respondents' answers to the sessions' questions were comprehensive, the content of the responses would have indeed differed if participants came from other countries. Much of the illustrations and examples originated from the Saudi manufacturing sector, as well as environment. Thus, solar power emerged as one of the dominant renewable energy sources when experts provided examples since that is the most prevalent source of clear power in the country.

5 Conclusions

The present analysis reviewed 107 peer-reviewed papers published in English between 2018 and 2023 addressing the integration of CE practices and RE sources. Additionally, the investigation summarized the responses of 10 experts on CE and RE integration in the manufacturing sector who participated in 2 focus group sessions held in 2024 featuring facilities owners, as well as researchers. Based on the mixed methods analytics approach, the papers and focus groups generated a list of 22 facilitators and hindrances (Table 2). The factors represented six distinct themes: (a) regulations, (b) institutions, (c) stakeholders, (d) finance and economics, (e) infrastructure, and (f) technology.

Using the factors and the themes, the researchers constructed a model summarizing the underlying process of CE and RE integration. The CLD map (Figure 4) presents 11 feedback loops organizing the CE and RE integration system. The loops highlight the dynamic structure of integration and the intersectionality of facilitators and hindrances. Network analysis demonstrated that strong government support, technical research and development, human capital technology programs, consultancy services, and cost represented the most important factors in the system.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Cranfield University Research Ethics System (CURES) (i.e., CURES/17446/2022). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MA: Resources, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation, Supervision, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology. MA-S: Data curation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1655375/full#supplementary-material

References

Abduljaber, M. (2018). The dimensionality, type, and structure of political ideology on the political party level in the Arab world. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 3, 464–494. doi: 10.1007/s41111-018-0101-7

Abduljaber, M. (2020). A dimension reduction method application to a political science question: Using exploratory factor analysis to generate the dimensionality of political ideology in the Arab world. J. Inf. Knowl. Manage. 19:2040002. doi: 10.1142/S021964922040002X

Abduljaber, M., Onder, M., and Aljadaan, R. (2025). Perceptions of democracy within the Middle East and North Africa. J. Int. Stud. 18, 86–100. doi: 10.14254/2071-8330.2025/18-1/4

Abduljaber, M. F., and Onder, M. (2024). When we can't see the wood for the trees: the lurking effect of sustainability on corruption. Cogent. Soc. Sci. 10:2318859. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2024.2318859

Aikenhead, G., Farahbakhsh, K., Halbe, J., and Adamowski, J. (2015). Application of process mapping and causal loop diagramming to enhance engagement in pollution prevention in small to medium-size enterprises: case study of a dairy processing facility. J. Clean. Prod. 102, 275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.069

Al Shehri, T., Braun, J. F., Howarth, N., Lanza, A., and Luomi, M. (2023). Saudi Arabia's climate change policy and the circular carbon economy approach. Clim. Policy 23, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2070118

Aldhafeeri, Z. M., and Alhazmi, H. (2022). Sustainability assessment of municipal solid waste in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in the framework of circular economy transition. Sustainability 14:5093. doi: 10.3390/su14095093

Ali, A. O., Elmarghany, M. R., Abdelsalam, M. M., Sabry, M. N., and Hamed, A. M. (2022). Closed-loop home energy management system with renewable energy sources in a smart grid: a comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 50:104609. doi: 10.1016/j.est.2022.104609

Almadhi, A., Abdelhadi, A., and Alyamani, R. (2023). Moving from linear to circular economy in Saudi Arabia: Life-cycle assessment on plastic waste management. Sustainability 15:10450. doi: 10.3390/su151310450

Alshammari, Y. M. (2020). Achieving climate targets via the circular carbon economy: the case of Saudi Arabia. C 6:54. doi: 10.3390/c6030054

Aranda-Usón, A., Portillo-Tarragona, P., Marín-Vinuesa, L. M., and Scarpellini, S. (2019). Financial resources for the circular economy: a perspective from businesses. Sustainability 11:888. doi: 10.3390/su11030888

Awan, U., and Sroufe, R. (2022). Sustainability in the circular economy: Insights and dynamics of designing circular business models. Appl. Sci. 12:1521. doi: 10.3390/app12031521

Azadnia, A. H., Onofrei, G., and Ghadimi, P. (2021). Electric vehicles lithium-ion batteries reverse logistics implementation barriers analysis: a TISM–MICMAC approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 174:105751. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105751

Balzani, V. (2019). Saving the planet and the human society: Renewable energy, circular economy, sobriety. Substantia, 3, 9–15. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-581

Barbrook-Johnson, P., and Penn, A. S. (2022). Systems Mapping: How to Build and Use Causal Models of Systems. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Barros, M. V., Salvador, R., De Francisco, A. C., and Piekarski, C. M. (2020). Mapping of research lines on circular economy practices in agriculture: from waste to energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 131:109958. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.109958

Belhadi, A., Kamble, S. S., Jabbour, C. J. C., Mani, V., Khan, S. A. R., Touriki, F. E., et al. (2022). A self-assessment tool for evaluating the integration of circular economy and industry 4.0 principles in closed-loop supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 245:108372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108372

Binder, T., Vox, A., Belyazid, S., Haraldsson, H., and Svensson, M. (2004). “Developing system dynamics models from causal loop diagrams,” in Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference of the System Dynamics Society (Albany, NY: System Dynamics Society), 1–21.

Bolger, K., and Doyon, A. (2019). Circular cities: Exploring local government strategies to facilitate a circular economy. Eur. Plann. Stud. 27, 2184–2205. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1642854

Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., and Labianca, G. (2009). Network analysis in the social sciences. Science 323, 892–895. doi: 10.1126/science.1165821

Borowski, P. F. (2022). Production processes related to conventional and renewable energy in enterprises and in the circular economy. Processes 10:521. doi: 10.3390/pr10030521

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health, 13, 201–216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Buchmann-Duck, J., and Beazley, K. F. (2020). An urgent call for circular economy advocates to acknowledge its limitations in conserving biodiversity. Sci. Total Environ. 727:138602. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138602

Bui, T-. D., Tseng, J-. W., Tseng, M-. L., and Lim, M. K. (2022). Opportunities and challenges for solid waste reuse and recycling in emerging economies: a hybrid analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 177:105968. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105968

Chen, T-. L., Kim, H., Pan, S-. Y., Tseng, P-. C., Lin, Y-. P., Chiang, P-. C., et al. (2020). Implementation of green chemistry principles in circular economy system towards sustainable development goals: Challenges and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 716:136998. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136998

Chishti, M. Z., Dogan, E., and Zaman, U. (2023). Effects of the circular economy, environmental policy, energy transition, and geopolitical risk on sustainable electricity generation. Util. Policy 82:101585. doi: 10.1016/j.jup.2023.101585

Cho, N., El Asmar, M., and Aldaaja, M. (2022). An analysis of the impact of the circular economy application on construction and demolition waste in the United States of America. Sustainability 14:10034. doi: 10.3390/su141610034

Chowdhury, M. S., Rahman, K. S., Chowdhury, T., Nuthammachot, N., Techato, K., Akhtaruzzaman, M., et al. (2020). An overview of solar photovoltaic panels' end-of-life material recycling. Energy Strategy Rev. 27:100431. doi: 10.1016/j.esr.2019.100431

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crielaard, L., Uleman, J. F., Châtel, B. D. L., Epskamp, S., Sloot, P., Quax, R., et al. (2024). Refining the causal loop diagram: a tutorial for maximizing the contribution of domain expertise in computational system dynamics modeling. Psychol. Methods 29, 169–183. doi: 10.1037/met0000484

Dagiliene, L., Varaniute, V., and Bruneckiene, J. (2021). Local governments' perspective on implementing the circular economy: a framework for future solutions. J. Cleaner Prod. 310:127340. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127340

D'Amato, D., and Korhonen, J. (2021). Integrating the green economy, circular economy and bioeconomy in a strategic sustainability framework. Ecol. Econ. 188:107143. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107143

Danish, M. S. S., and Senjyu, T. (2023). Shaping the future of sustainable energy through AI-enabled circular economy policies. Circular Econ. 2:100040. doi: 10.1016/j.cec.2023.100040

Demir, I., and Aktan, C. C. (2016). Resistance to change in government: actors and factors that hinder reform in government. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Stud. 8, 226–245.

Dennison, M. S., Bhuvanesh Kumar, M., and Jebabalan, S. K. (2024). Realization of circular economy principles in manufacturing: Obstacles, advancements, and routes to achieve a sustainable industry transformation. Discover. Sustain. 5:438. doi: 10.1007/s43621-024-00689-2

Dey, S., Veerendra, G. T. N., Anjaneya Babu, P. S. S., Phani Manoj, A. V., and Nagarjuna, K. (2024). Degradation of plastics waste and its effects on biological ecosystems: a scientific analysis and comprehensive review. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2, 70–112. doi: 10.1007/s44174-023-00085-w

Dhirasasna, N., and Sahin, O. (2019). A multi-methodology approach to creating a causal loop diagram. Systems 7:42. doi: 10.3390/systems7030042

Domenech, T., and Bahn-Walkowiak, B. (2019). Transition towards a resource-efficient circular economy in Europe: policy lessons from the EU and the member states. Ecol. Econ. 155, 7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.11.001

Duran, A. S., Atasu, A., and Van Wassenhove, L. N. (2022). Cleaning after solar panels: Applying a circular outlook to clean energy research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 60, 211–230. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2021.1990434

Evans, M. I., and Britt, D. W. (2023). Resistance to change. Reprod. Sci. 30, 835–853. doi: 10.1007/s43032-022-01015-9

Finn, J., Barrie, J., João, E., and Zawdie, G. (2020). A multilevel perspective of transition to a circular economy with particular reference to a community renewable energy niche. Int. J. Technol. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 19, 195–220. doi: 10.1386/tmsd_00022_1

Ghimire, U., Sarpong, G., and Gude, V. G. (2021). Transitioning wastewater treatment plants toward circular economy and energy sustainability. ACS Omega 6, 11794–11803. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c05827

Ghisellini, P., Cialani, C., and Ulgiati, S. (2016). A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Cleaner Prod. 114, 11–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007

Govindan, K. (2018). Sustainable consumption and production in the food supply chain: a conceptual framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 195, 419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.03.003

Grafström, J., and Aasma, S. (2021). Breaking circular economy barriers. J. Cleaner Prod. 292:126002. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126002

Guest, G., Namey, E., and McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods 29, 3–22. doi: 10.1177/1525822X16639015

Guo, S., and Chen, L. (2022). Why is China struggling with waste classification? A stakeholder theory perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 183:106312. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106312

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Singh, R. P., Suman, R., and Qadri, M. A. (2023). A pervasive study on green manufacturing towards attaining sustainability. Green Technol. Sustain. 1:100018. doi: 10.1016/j.grets.2023.100018

Haraldsson, H. V. (2004). Introduction to system thinking and causal loop diagrams. Lund: Department of Chemical Engineering, Lund University.

Hassan, S. T., Baloch, M. A., Bui, Q., and Khan, N. H. (2024). The heterogeneous impact of geopolitical risk and environment-related innovations on greenhouse gas emissions: the role of nuclear and renewable energy in the circular economy. Gondwana Res. 127, 144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2023.08.016

Hassan, S. T., Wang, P., Khan, I., and Zhu, B. (2023). The impact of economic complexity, technology advancements, and nuclear energy consumption on the ecological footprint of the USA: towards circular economy initiatives. Gondwana Res. 113, 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2022.11.001

Hennink, M., and Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., and Weber, M. B. (2019). What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qual. Health Res. 29, 1483–1496. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692

Hidalgo-Crespo, J., Moreira, C. M., Jervis, F. X., Soto, M., Amaya, J. L., Banguera, L., et al. (2022). Circular economy of expanded polystyrene container production: environmental benefits of household waste recycling considering renewable energies. Energy Rep. 8, 306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2022.01.071

Ioannidis, F., Kosmidou, K., and Papanastasiou, D. (2023). Public awareness of renewable energy sources and circular economy in Greece. Renew. Energy. 206, 1086–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2023.02.084

Ishaq, M., Ghouse, G., Fernández-González, R., Puime-Guillén, F., Tandir, N., Santos, d. e., Oliveira, H. M., et al. (2022). From fossil energy to renewable energy: Why is circular economy needed in the energy transition? Front. Environ. Sci. 10:941791. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.941791

Islam, K. N., Sarker, T., Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., Chowdhury Atri, A., and Alam, M. S. (2021a). Renewable energy generation from livestock waste for a sustainable circular economy in Bangladesh. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 139:110695. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110695

Islam, M. T., Nizami, M. S. H., Mahmoudi, S., and Huda, N. (2021b). Reverse logistics network design for waste solar photovoltaic panels: a case study of New South Wales councils in Australia. Waste Manag. Res. 39, 386–395. doi: 10.1177/0734242X20962837

Janik, A., Ryszko, A., and Szafraniec, M. (2020). Greenhouse gases and circular economy issues in sustainability reports from the energy sector in the European Union. Energies 13:5993. doi: 10.3390/en13225993

Jiang, S., Wang, P., Mei, Z., Wang, W., and Xu, D. (2021). A variable inductor based harmonic filter design for multi-phase renewable energy systems with double closed-loop control. Energy 236:121522. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.121522

Kandpal, V., Jaswal, A., Santibanez Gonzalez, E. D. R., and Agarwal, N. (2024). “Sustainable investment strategies for renewable energy and circular economy projects,” in Sustainable Energy Transition: Circular Economy and Sustainable Financing for Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practices (Berlin: Springer Nature), 201–216.

Khajuria, A., Atienza, V. A., Chavanich, S., Henning, W., Islam, I., Kral, U., et al. (2022). Accelerating circular economy solutions to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals. Circ. Econ. 1:100001. doi: 10.1016/j.cec.2022.100001

Khameneh, R. T., Rezaeian, O., and Mansouri, M. (2024). “A systems dynamic approach to evaluate disruptions in large-scale transit systems: a case study of PATH,” in 2024 19th Annual System of Systems Engineering Conference (SoSE) (Piscataway, NJ: IEEE), 321–326.

Khan, S., Haleem, A., and Fatma, N. (2022). Effective adoption of remanufacturing practices: a step towards circular economy. J. Remanuf. 12, 167–185. doi: 10.1007/s13243-021-00109-y

Kitchenham, B., Brereton, O. P., Budgen, D., Turner, M., Bailey, J., Linkman, S., et al. (2009). Systematic literature reviews in software engineering—A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 51, 7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2008.09.009

Kiviranta, K., Thomasson, T., Hirvonen, J., and Tähtinen, M. (2020). Connecting circular economy and energy industry: a techno-economic study for the Åland Islands. Appl. Energy 279:115883. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115883

Klemeš, J. J., Foley, A., You, F., Aviso, K., Su, R., Bokhari, A., et al. (2023). Sustainable energy integration within the circular economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 177:113143. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.113143

Klemeš, J. J., Varbanov, P. S., Walmsley, T. G., and Foley, A. (2019). Process integration and circular economy for renewable and sustainable energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 116:109435. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.109435

Knoke, D., and Yang, S. (2008). Social Network Analysis (No. 154). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kraus, S., Breier, M., and Dasí-Rodríguez, S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrepreneur. Manage. J. 16, 1023–1042. doi: 10.1007/s11365-020-00635-4

Kumar, V., Sezersan, I., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Gonzalez, E. D. R. S., and Al-Shboul, M. A. (2019). Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: benefits, opportunities and barriers. Manag. Decis. 57, 1067–1086. doi: 10.1108/MD-09-2018-1070

Lamé, G. (2019). “Systematic literature reviews: an introduction,” in Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design (Vol. 1) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1633–1642.

Lim, J., Ahn, Y., and Kim, J. (2023). Optimal sorting and recycling of plastic waste as a renewable energy resource considering economic feasibility and environmental pollution. Process Safety Environ. Protect. 169, 685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2022.11.027

Lin, G., Palopoli, M., and Dadwal, V. (2020). “From causal loop diagrams to system dynamics models in a data-rich ecosystem,” in Leveraging Data Science for Global Health (Berlin: Springer International Publishing), 77–98.

Liu, C., Dong, H., Cao, Y., Geng, Y., Li, H., Zhang, C., et al. (2021). Environmental damage cost assessment from municipal solid waste treatment based on LIME3 model. Waste Manage. 125, 249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2021.02.051

Mathur, N., Singh, S., and Sutherland, J. W. (2020). Promoting a circular economy in the solar photovoltaic industry using life cycle symbiosis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 155:104649. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104649

McKim, C. A. (2017). The value of mixed methods research: A mixed methods study. J. Mix. Methods Res. 11, 202–222. doi: 10.1177/1558689815607096

Mendoza, J. M. F., Gallego-Schmid, A., Velenturf, A. P. M., Jensen, P. D., and Ibarra, D. (2022). Circular economy business models and technology management strategies in the wind industry: sustainability potential, industrial challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 163:112523. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112523

Milousi, M., and Souliotis, M. (2023). A circular economy approach to residential solar thermal systems. Renew Energy 207, 242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2023.02.109

Mohajan, H. K. (2021). Cradle to cradle is a sustainable economic policy for the better future. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 21, 569–582.

Molano, J. C., Xing, K., Majewski, P., and Huang, B. (2022). A holistic reverse logistics planning framework for end-of-life PV panel collection system design. J. Environ. Manage. 317:115331. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115331

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus Groups as Qualitative Research (Vol. 16). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Mulvaney, D., Richards, R. M., Bazilian, M. D., Hensley, E., Clough, G., Sridhar, S., et al. (2021). Progress towards a circular economy in materials to decarbonize electricity and mobility. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 137:110604. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110604

Munir, M. T., Ahmad Mohaddespour, A. T., Nasr, T., and Carter, S. (2021). Municipal solid waste-to-energy processing for a circular economy in New Zealand. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 145:111080. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111080

Mutezo, G., and Mulopo, J. (2021). A review of Africa's transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy using circular economy principles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 137:110609. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110609

Niyommaneerat, W., Suwanteep, K., and Chavalparit, O. (2023). Sustainability indicators to achieve a circular economy: A case study of renewable energy and plastic waste recycling corporate social responsibility (CSR) projects in Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 391:136203. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136203

Ogunmakinde, O. E., Egbelakin, T., and Sher, W. (2022). Contributions of the circular economy to the UN sustainable development goals through sustainable construction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 178:106023. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.106023

Onder, M. (2019). Regime type, issue type and economic sanctions: the role of domestic players. Economies 8:2. doi: 10.3390/economies8010002

Onder, M. (2021). Economic sanctions outcomes: an information-driven explanation. J. Int. Stud. 14, 38–57. doi: 10.14254/2071-8330.2021/14-2/3

Onder, M. (2022). Consequences of economic sanctions on minority groups in the sanctioned states. Digest Middle East Stud. 31, 201–227. doi: 10.1111/dome.12268

Onder, M. (2023). “Overview of secondary sanctions: Turkey under the ghost of Western economic sanctions,” in The Routledge Handbook of the Political Economy of Sanctions (England: Routledge), 260–273.

Onder, M., and Abduljaber, M. (2025b). A novel legal approach for justifying economic sanctions and tariffs: a semiotic analysis of the second trump administration position. Int. J. Semiotics Law 1– 22. doi: 10.1007/s11196-025-10339-z

Onder, M., and Abduljaber, M. F. (2025a). Predicting democracy support in the Middle East and North Africa. World Affairs 188:e70010. doi: 10.1002/waf2.70010

Onyeka, N. C., and Emeka, N. (2025). Circular economy and zero-energy factories: a synergistic approach to sustainable manufacturing. J. Res. Eng. Appl. Sci. 10, 829–835.

Pagoropoulos, A., Pigosso, D. C. A., and McAloone, T. C. (2017). The emergent role of digital technologies in the circular economy: a review. Procedia CIRP 64, 19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.procir.2017.02.047