- School of Basic and Applied Sciences, K.R. Mangalam University, Gurugram, Haryana, India

Coal-fired thermal power plants remain the primary electricity source in much of the developing world, generating vast quantities of fly ash (FA) as a solid waste by-product. This ultrafine particulate contains heavy metals and, in some cases, radioactive elements, creating disposal challenges and raising concerns about environmental contamination, bioaccumulation, and human health risks. At the same time, fly ash is rich in plant-essential nutrients such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, and trace elements, and its application as a soil amendment can improve physical structure, nutrient availability, and biological activity. Research indicates that, when applied judiciously, fly ash can enhance plant growth, chlorophyll synthesis, phenolic compound content, and crop yield, including in medicinal species. However, the potential for toxic element transfer through the food chain necessitates rigorous risk assessment and management strategies. This study examines both the hazards and agronomic opportunities of FA, highlighting the importance of balancing environmental safety with the potential for sustainable agricultural use.

1 Introduction

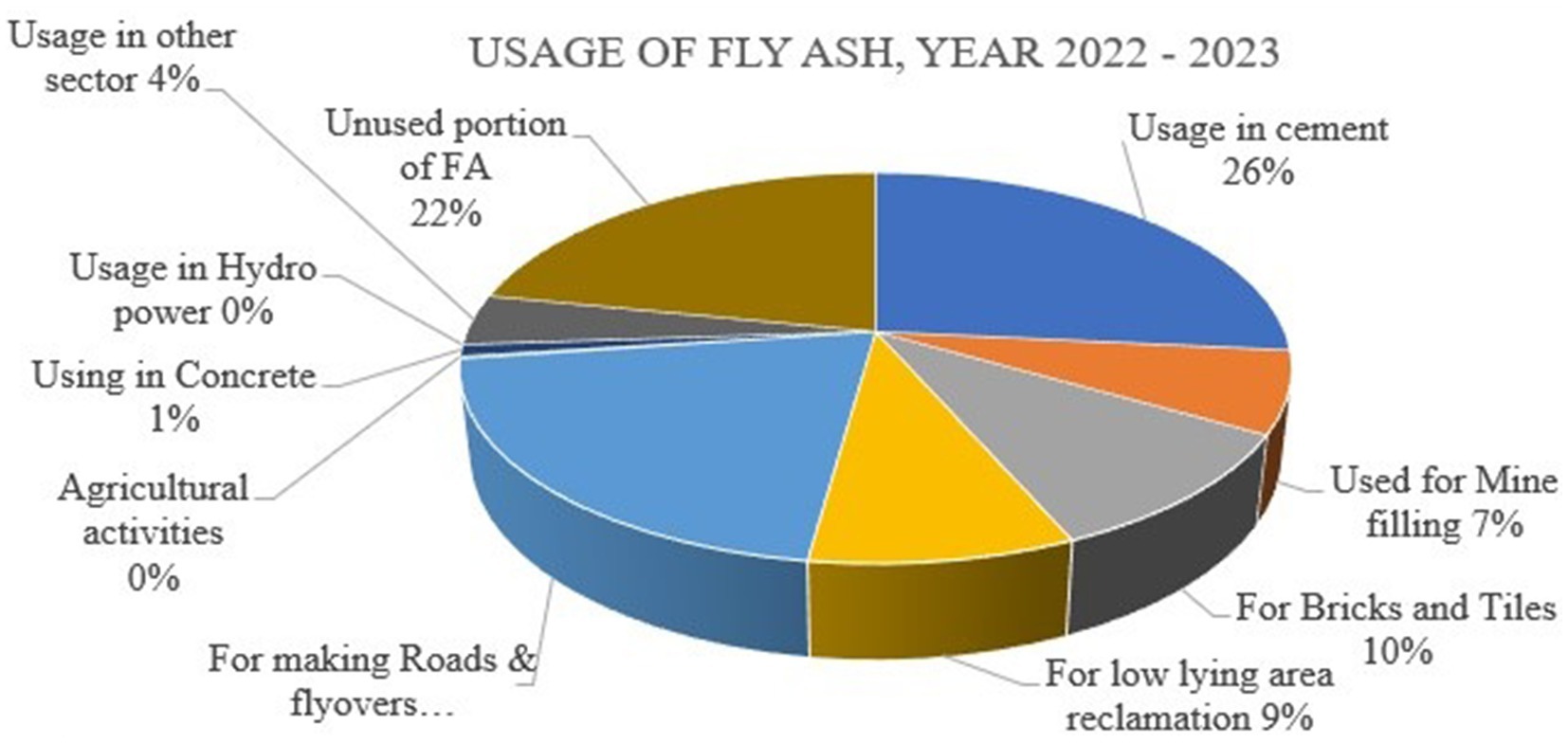

Coal is used extensively worldwide as the primary source of energy for power generation. In the thermal power station, electricity is produced by coal combustion, and as a product, FA is produced (Rusănescu and Rusănescu, 2023; Basu et al., 2009; Patil et al., 2013; Kuznia, 2025). In India, thermal power plants account for over 70% of total electricity production and generate substantial quantities of FA. National data for 2022–23 indicate that approximately 140 million tonnes of FA were produced, with only about 60% effectively utilized Figure 1 (Central Electricity Authority, 2023).

The Basel Convention has considered FA as a waste of the green list. However, it is worthwhile to note that many countries are still treating this only as waste and are not able to re-utilize it. Only few developed countries are able to reuse ~100% (Italy, Denmark and Netherlands); while other countries (west Germany, France) reuse ~85%; whereas reuse in India is very low, increased during year 1990 (3%) to year 2005 (38%; Kishor et al., 2010; Bhattacharjee and Kanpal, 2002) further enhanced to 78% including significant use of 26% in cement, 21% in roads and flyovers, 10% in bricks and tiles, 9% for reclamation of low lying area and 7% in mine filling (Central Electricity Authority, 2023; Jeyarajp and Sankararajan, 2024). The main factor responsible for this less-utilized proportion of FA is the involvement of more costly and less efficient technology. It can be stated that consumption is lower than the production rate. The quantity of water, energy, and land area required for the efficient dumping of FA is significant. FA from coal-based thermal power plants is managed through a range of disposal and reuse strategies. Historically in India, wet disposal was the predominant method, where FA was mixed with water and stored in lined or unlined ponds, a practice that consumes significant land and water resources and carries risks such as groundwater contamination and embankment failure. In recent years, there has been a shift towards dry disposal methods—such as lined engineered landfills and dry stacking—where FA is handled in dry form to minimize environmental hazards, particularly the risk of leachate infiltration into groundwater. Reuse options are also expanding, with FA being incorporated into products like cement, concrete, bricks, blocks, and materials for road construction and mine filling, helping reduce landfill demand. India’s regulatory framework mandates complete FA utilization, and progress towards this target has been notable. Advanced applications, such as geopolymer binders and alkali-activated materials, are emerging globally, offering higher-value uses. Furthermore, stabilization and encapsulation processes, which involve binding FA with other materials to reduce contaminant mobility or embedding it in dense matrices to limit dust and pollutant release, provide additional pathways for its safe management. Even after this significant volume of FA remains unutilized, and due to the fine nature of particles and content of heavy metals, its throwing is always reported as a liability to the environment, causing soil degradation (Budania and Dahiya, 2018; McBride and West, 2005; Mittra et al., 2003; Montes-Hernandez et al., 2009; Arivazhagan, 2011).

FA contains toxic heavy metals (e.g., As, Pb, Cd, Cr). The adverse impact of FA is associated with the leaching of these lethal elements from FA to soils, ultimately affecting underground water, which leads to a change of elemental composition in plants as well as accelerating the introduction of these toxic elements via the food chain (Carlson and Adriano, 1993). Due to the fineness of particles, even after using emission control devices, power plant units are not able to fully control the leakage of FA in air which is affecting human health. Due to prolong exposure to FA, irritation affected various organs, e.g., eyes, lungs fibrosis, skin, pneumonitis and bronchitis (Carlson and Adriano, 1993). Dry FA is a fine, powder-like material obtained from the flue gases of coal-fired thermal power plants. It forms as a byproduct during coal combustion and is composed mainly of non-combustible mineral constituents such as silica, alumina, and iron oxide, along with small amounts of unburned carbon. FA Considering its fine nature, handling of it is a serious concern and intensify the environmental pollution (air pollution, water pollution and soil pollution), tremendously affecting the ecology and cultivation, disintegrate the structural surfaces (Pujari and Dash, 2006). FA particles size is in the range of silt and during mild breeze (6–10 km/h), dry form can be get lifted and travels for several hundred meters downwind direction. To manage such a huge amount of FA, for stabilization against wind and water erosion, it is recommended to start vegetation on the landfill, promoting and providing shelter and creating habitat for wildlife which ultimately leads to form a more aesthetically delightful landscape (Adriano et al., 1980). FA changes the properties of the soil (physical and chemical), impacting plant existence and its growth, hence progress on revegetation process of these impacted locations proceed very slowly.

In India, construction and biomass generation are the major areas for FA utilization, year 2022–2023 (Central Electricity Authority, 2023). Utilization in construction area includes various activities, e.g., production of cement, manufacturing of brick and road embankments (Jeyarajp and Sankararajan, 2024). While various areas included in biomass production are agricultural, floriculture, and forestry. However, most FA utilization in forestry is established for growing few economically important trees, e.g., timber wood, biodiesel crops, firewood, plywood trees, paper tree. Therefore, FA application for biomass generation is very important strategies having economic importance as well as to protect environmental degradation (Panday et al., 1985, 2009a,b; Sajwan, 1995, Sao et al., 2007; Schnappinger, et al., 1975; Sharma et al., 2001; Sharma and Uma Singh, 2007; Siddiqui et al., 2022).

2 Physico-chemical characteristics of FA

Physico-chemical attributes of FA depend up on various factors, e.g., coal origin (anthracite, lignite, bituminous and sub-bituminous) and chemical composition, combustion conditions and heating values, emission control, handling and storage techniques (Chakraborty et al., 2025; Abhishek et al., 2025).

2.1 Physical properties

Composition and physical characteristics of FA depends upon various facts, e.g., nature and type of coal, type of boiler and combustion conditions, content of ash in coal, control on emission, conditions associated with storage, handling procedure and collector set up. The empty sphere of FA is filled by small amorphous particles and crystals. Due to the presence of porous particles and other carbonaceous nature units, FA has light texture properties and relatively higher surface area. Few particles of FA are small in size and spherical in shape while some are of large size, as a result different forms of FA present with wide range of properties (Natusch and Wallace, 1974) e.g. mean particle density (2.7 to 3.4 g cm-1), bulk density (1 to 1.8 g cm-1), moisture retention range (6.1 to 13.4%), water holding capacity (49 to 66%) and specific gravity (2.1 to 2.6 g cm-1) (Abhishek et al., 2025; Chakraborty et al., 2025).

2.2 Chemical properties

The components which are accountable for the observed differences in the physical characteristics of FA, also affecting the chemical attributes. FA is broadly categorized into Class F and Class C based on its chemical composition and the type of coal from which it originates, as outlined in ASTM C618. Class F FA is typically derived from the combustion of bituminous or anthracite coals and is rich in silica and alumina, with the combined content of silica (SiO₂), alumina (Al₂O₃), and iron oxide (Fe₂O₃) generally exceeding 70%. It contains low calcium oxide (CaO), usually less than 10%, and exhibits pozzolanic properties, requiring the presence of an activator such as lime or cement to form cementitious compounds. In contrast, Class C FA is produced from the combustion of sub-bituminous or lignite coals and contains a higher proportion of calcium oxide, often in the range of 15–30%, with the combined (SiO₂ + Al₂O₃ + Fe₂O₃) typically between 50 and 70%. This higher calcium content imparts both pozzolanic and self-cementing characteristics, enabling it to harden upon contact with water without additional activators. The distinction between these classes is significant, as it governs the material’s reactivity, strength development potential, durability performance, and its suitability for various applications in construction, soil stabilization, and other engineering uses (Abhishek et al., 2024; Chakraborty et al., 2024).

The chemical composition of FA is largely determined by the type of coal burned and the combustion process, with major constituents typically including silicon dioxide (20–60%), aluminium oxide (5–35%), and iron oxide (4–40%), along with variable amounts of calcium oxide (1–40%) and minor oxides such as magnesium, potassium, and sodium, generally below 10%. When in contact with water, FA can produce leachates with pH values ranging from acidic to strongly alkaline (approximately 4–12), depending on the mineral phases present and their buffering capacity. Electrical conductivity (EC) values commonly vary between 1.6 and 24 mS cm−1, reflecting the concentration of dissolved salts. In terms of nutrient content, FA may supply macronutrients such as calcium (5–177 g kg−1), magnesium (5–61 g kg−1), and potassium (2–35 g kg−1), as well as micronutrients including boron, copper, manganese, zinc, and molybdenum. However, it also contains potentially toxic trace elements, with reported ranges (mg kg−1) for arsenic at 0.5–279, lead at 0.4–252, chromium at 3.4–437, cadmium at 0.1–18, mercury at 0.005–4.2, selenium at 0.08–19, boron at 10–1,300, nickel at 1.8–258, and zinc at 4–2,300. The solubility and environmental mobility of these elements are influenced by factors such as pH, redox conditions, and particle surface chemistry, making detailed chemical and leachate analysis essential for evaluating the reuse potential and environmental implications of FA (Adriano et al., 1980; Goetz, 1983). All the elements similar to soil are present in FA, except carbon and nitrogen (Kumar et al., 2000). It is well known that higher content of aluminium is organically toxic while in FA aluminium is present in the form of aluminosilicate structure which has very less toxicity (Page et al., 1979). Due to the presence of these elements, variance is observed in the chemical properties of FA, e.g., colour variation is due to Iron oxide, for the range of pH content with sulphur present in the coal used is responsible (Matti et al., 1990). Which means high Sulphur content in coal will produce acidic ash whereas alkaline ash is produced by low Sulphur content.

2.3 Mineralogical properties

FA is predominantly composed of both amorphous (glassy) aluminosilicate phases and various crystalline minerals formed during coal combustion. The amorphous glassy fraction often comprising 70–90% of the material, is created by rapid quenching of molten silicate particles and largely governs FA’s pozzolanic reactivity. Common crystalline constituents identified via XRD include mullite (3Al₂O₃·2SiO₂) and quartz (SiO₂), typically deriving from the thermal transformation of aluminosilicate sources and residual siliceous grains, respectively. Iron oxide phases such as hematite (Fe₂O₃) and magnetite (Fe₃O₄) are frequently observed, sometimes as surface inclusions on glassy spherules. Studies on FA from power plants in Poland reported precisely these phases as mullite, quartz, and iron oxides embedded in glass spheres with hematite and magnetite especially enriched on particle surfaces. Similarly, investigations of FA from Vietnam indicated that magnetic fractions are rich in magnetite and hematite, whereas non-magnetic components primarily consist of quartz and mullite.

In addition, high-calcium (Class C) FA may contain anhydrite (CaSO₄), free lime (CaO), periclase (MgO), calcite (CaCO₃), and cement-like silicate phases such as di-calcium silicate and tri-calcium silicate, reflecting the presence of calcium-bearing minerals in the feed coal. The mineralogical mix and relative abundances are influenced by variables such as coal type, combustion temperature, and cooling rate—factors which determine how much of the original mineral assemblage is retained in crystalline form versus converted to glass. Overall, FA’s reactivity, density, and applicability in cementitious, ceramic, or geopolymeric materials are strongly controlled by this interplay between the reactive amorphous matrix and embedded crystalline phases (Hodgson and Holliday, 1966; Chakraborty et al., 2024; Chakraborty et al., 2025).

3 Improvement in soil potency

Numerous research has been already accomplished by studying the FA impact on soil. Application of FA to soil can induce significant changes in its physical and chemical environment due to the ash’s mineral composition, alkalinity, and fine particle size. One of the most pronounced effects is on soil pH. Most FA, particularly Class C types with higher calcium oxide content, exhibits an alkaline reaction (pH often > 9), and when applied to acidic soils, it can raise the pH, thereby reducing exchangeable acidity and enhancing base saturation. This liming effect can improve nutrient availability for certain crops but may also increase the solubility of some oxyanion-forming trace elements (e.g., As, Mo, Se) under strongly alkaline conditions. Soil productiveness improved significantly with use of FA as an agronomical adjustor (Rajakumar and Patil, 2019). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) may be altered indirectly. FA itself has limited inherent CEC compared to clay minerals, but its fine texture and amorphous aluminosilicate glass can contribute to additional exchange sites over time as weathering releases secondary minerals (e.g., smectite, allophane). The dissolution of FA also supplies soluble bases (Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+) that occupy exchange sites in the soil, potentially displacing acidic cations (H+, Al3+) and improving nutrient-holding capacity in the short term. In sandy or degraded soils, FA particles can physically fill pore spaces, reduce bulk density, and improve moisture retention, which may indirectly influence nutrient retention and CEC dynamics (Ghodrati et al., 1995; Capp, 1978; Buck et al., 1990; Kene et al., 1991; Khan and Khan, 1996; Singh and Siddiqui, 2003; Jala and Goyal, 2006; Rautaray et al., 2003; Phung et al., 1979; Gupta et al., 1990; Gupta et al., 2007; Lau and Wong, 2006; Abhishek et al., 2024; Abhishek et al., 2025). FA contains higher concentration of CaO and can be used as alternative of lime. Hence, remediation of soil can be achieved by using FA which also improves the soil fertility, improvise the nutrient status which ultimately resulting in the increase of crop yield (Wong and Wong, 1986; Schutter and Fuhrmann, 2001; Sarangi et al., 2001; Christensen, 1987; Jiang et al., 1999). Various research studies identified that crop plants of some families are most tolerant to FA, e.g., Brassicaceae, Fabiaceae and Poaceae. While it has been observed that Acacia sp. and Leucaena leucocephala can tolerate higher content and positive survival ratio in dull, deserted, and areas contaminated with metals (Cheung et al., 2000).

Microbial activity in FA amended soils often shows an initial decline, particularly when high application rates elevate pH beyond the optimal range for native microbial communities or when soluble salts raise electrical conductivity to inhibitory levels. However, as the soil-ash system equilibrates, microbial biomass and enzymatic activity may recover or even surpass baseline levels, aided by improved nutrient availability (e.g., B, Mo, P, Ca) and enhanced moisture conditions. The response varies with FA composition, application rate, soil type, and management practices; in neutral or slightly acidic soils, moderate FA additions can stimulate microbial processes linked to nutrient cycling, whereas in highly alkaline environments, sensitive microbial taxa may be suppressed. In addition, nitrogen content of infertile soils can be improved by the planting legume plants and using bacteria well known symbiotic nitrogen-fixing relationship (Vajpayee et al., 2000). On FA amended soils, leguminous plants grow well and demonstrate absence of any injury symptoms (Singh S. N. et al., 1997; Singh A. K. et al., 1997; Ahmad and Alam, 1997). Overall, FA acts as a soil amendment with both corrective and disruptive potential (Narayanasamy, 2002; Narayanasamy, 2003). Its capacity to modify pH, supply base cations, and influence CEC can benefit certain soils, but the associated shifts in microbial community structure and function require careful management to avoid adverse ecological effects. Long-term monitoring of chemical equilibria and biological indicators is therefore essential for sustainable application (Jones and Lewis, 1960).

4 Improving crop growth and yield

Due to presence of hydroxide and carbonate, FA has unique chemical characteristics to neutralize acidity in soils (Matsi and Keramidas, 1999). Soil amendment using FA is well known for changing the pH and improvement in texture of soil, also to provide essential plant nutrients which results in the increase of crop production (Pandey, 2008). Several field studies as well as greenhouse experiments confirm about the positive impact of FA on plant growth and ability to enhance the agronomic capacity of soil due to chemical constituents of FA (Wong and Wong, 1989; Singh and Singh, 1986; Inam, 2007).

FA contains substantial concentration of Calcium, Phosphorous, Magnesium, Potassium and Sulphur. Therefore, supplemental supply of FA leads to enhancement of nutrient uptake and causes significant progress in plant growth (Kalra et al., 1997), ultimately results in increase of crop yield (Basu et al., 2007). Increase in the accessibility of Sulphur content from FA is the main factor behind this increase of crop yield. In agronomic crops, e.g., barley and B. grass (Page et al., 1979), FA addition up to 8% w/w concentration results in the considerable increment. FA application enhances the growth, improves the metabolic rate and leads to higher photosynthetic pigmentation as observed in maize and soybean (Mishra and Shukla, 1986). By using the FA in a concentration up to 40%, yield of tomatoes increased by 81% (Khan and Khan, 1996), while using FA in concentration of 25% w/w, various vegetables obtained in higher yield, e.g., brinjal, tomato, cabbage (Goyal et al., 2002). Also, by applying low concentration of FA, i.e., 5%, rate of seed germination increases as well as lettuce root length amplified (Lau and Wong, 2006; Ou et al., 2020).

To establish the effect of FA on the productivity and growth of Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri L.; Panda et al., 2020), FA used for soil amendments and studied in a pot culture experiment. B. monnieri seedlings cultivated using different concentration of FA for 90 days. It has been observed that using amended soil (FA 25%), in comparison with garden soil (control) and extra FA treatments, significantly improvise the tolerance index (>100%), growth in plant biomass and essential oil content. In comparison with seedlings which are grown on garden soil, no change observed in the content of chlorophyll in leaf and photosynthetic parameters when 25% of FA uses as medium. However, observed that higher concentration of FA adversely impacts these parameters and content declines significantly. Uses of higher concentration of FA results in the oxidative damage and also induce some anti-oxidative enzymes activities in B. monnieri indicating about the capability of plant to withstand oxidative stress and its tolerance. Research study demonstrated that for cultivation of B. monnieri L, soil can be amended with FA (25%) which results in enhancement of plant biomass along with production of essential oil (Panda et al., 2020).

Similarly, FA effects studied on the growth of medicinal plant Withania somnifera L. (Dunal), also known as ashwagandha (Kumar et al., 2017). Various parameters, e.g., effect on seed germination, plant height, leaf area per leaf, total leaf area per plant, plant fresh weight, chlorophyll a & b, carotenoids. Due to increasing concentration of FA, most of the studied parameter shows positive impact and enhancement up to the use of FA concentration (10–15%). Further using high concentration of FA, observed a decline in the growth parameters. Thus, for growth of medicinal plant Withania somnifera, 10–15% FA incorporation in soil is suitable (Kumar et al., 2017).

Using pot culture conditions, impact of FA application studied on Calendula officinalis (Varshney et al., 2021). Under different composition of FA in soil (% ration as Control, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100% of FA), impact studied on biochemical parameters (nitrate and nitrate reductase, soluble protein and reducing sugar), photosynthetic pigments including carotenoids, chlorophyll (both a and b) and total chlorophyll, metal accumulation (Cadmium, Cobalt, Chromium, Copper, Iron, Manganese, and Zinc) and antioxidant defense activity. The results of this study indicated that physico-chemical properties of soil significant improvised with the addition of FA (40%) in soil. Beneficial impact also observed in various other biochemical parameters of plants along with enhancement in photosynthetic pigment. However, observed that under high FA applications these parameters declined. While contrary to this, with increasing FA application, antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD & CAT and Peroxidase) increase to prevent the heavy metal stress due to uptake from FA. Also, levels of antioxidant enzyme increased in leaves at high FA applications indicating heavy metal stress as well as mitigation of reactive oxygen species (Varshney et al., 2021).

Other experiments using FA has been executed which shows significant and strong positive relationships with suitability of various concentration of FA (Kumar and Patra, 2012). To evaluate the impact of increasing composition of FA (from control soil, i.e., 0 to 100%) along with Garden soil (GS), study related with Mentha piperita has been conducted on different parameters of plant. During the study, parameters related with plant growth responses and elemental accumulation, composition of volatile oil and overall yield studied. It is observed that in experiments having concentration of FA at level of ≤50% results in better growth of plant, composition of oil and its yield; whereas with application of FA at composition more than 50%, results in the diminished growth of plant, composition of oil and its yield. Content of essential oil, i.e., Menthol, methyl acetate and menthofuran are changing with the compositional change of FA in soil. In this study, concentrations of Cd, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Zn in Mentha piperita roots and shoots exhibited significant positive correlations with fly ash (FA) application. Correlation coefficients indicated greater accumulation of Mn and Zn in roots (r = 0.997 and 0.993, respectively) compared with shoots (r = 0.989 and 0.914). Similarly, higher regression coefficients for Fe and Ni in roots (0.982 and 0.989, respectively) confirmed preferential root accumulation, whereas Cu and Cr were more strongly associated with shoots (0.999 and 0.995, respectively) than roots (0.954 and 0.989). Comparable patterns were reported by Singh S. N. et al. (1997) and Singh A. K. et al. (1997) in Vicia faba, where Cr accumulated primarily in shoots, and by Singh and Agarawal (2010), who suggested that detoxification mechanisms at the root level restrict metal translocation. Collectively, these results indicate that most metals are preferentially sequestered in roots, with only partial transfer to above ground tissues (Kumar and Patra, 2012; Singh S. N. et al., 1997; Singh A. K. et al., 1997; Singh and Agarawal, 2010).

Study related with Coleus forskohlii found that value of chlorophyll a and b content is directly related with enhancement of FA concentration in soil (Sinha et al., 2013). In normal soil, C. forskohlii has 2.7 mg/g chlorophyll a, whereas for FA in soil (5 and 10%) chlorophyll a level improved to 2.9 and 3.0 mg/mL, respectively. Similarly, chlorophyll b content was 0.5 mg/g in normal soil while using 5 and 10% FA this content increased to 0.6 & 0.45 mg/g, respectively. Study also shows that phenolic component significantly increased in FA containing soil. Phenolic component in C. forskohlii in normal soil is 1.2 mg/100 mg whereas in 5 and 10% FA soil this increased to 1.6 mg/100 mg and 2.2 mg/100 mg, respectively.

In a study related with Jatropha curcas, pot culture experiments have been performed to study the impact of varying composition of FA with soil on biodiesel plant growth (Raj and Mohan, 2014). Mixture with soil prepared by adding FA in the range from control, i.e., 0 to 100%. Various growth and morphological parameters have been studied including total nitrogen and protein content, plant height, pigment content and number of leaves. During the study of Jatropha curcus it has been observed that all the growth parameters are best in pot having FA concentration of 25% whereas after 1.5 years of seed sowing in 100% FA growth parameters deteriorate significantly. For photosynthesis, primary part of plant is Leaves and to all parts of plant leave food perform the function of metabolic fuel. Therefore, the overall status of plant growth performance and metabolic activities are represented by the foliar response. Average plant height achieved is 92.7 cm, while healthy leaves are in average number of 63, average content of pigment is 0.95 mg/g, total nitrogen content in average is 5.8 mg/g and average content of protein is 38.4 mg/g. Therefore, it is concluded that low dose of FA in soil is suitable for all the growth parameters which represents a step forward in the most suited and environmentally responsive utilization of waste for growth of biodiesel plant.

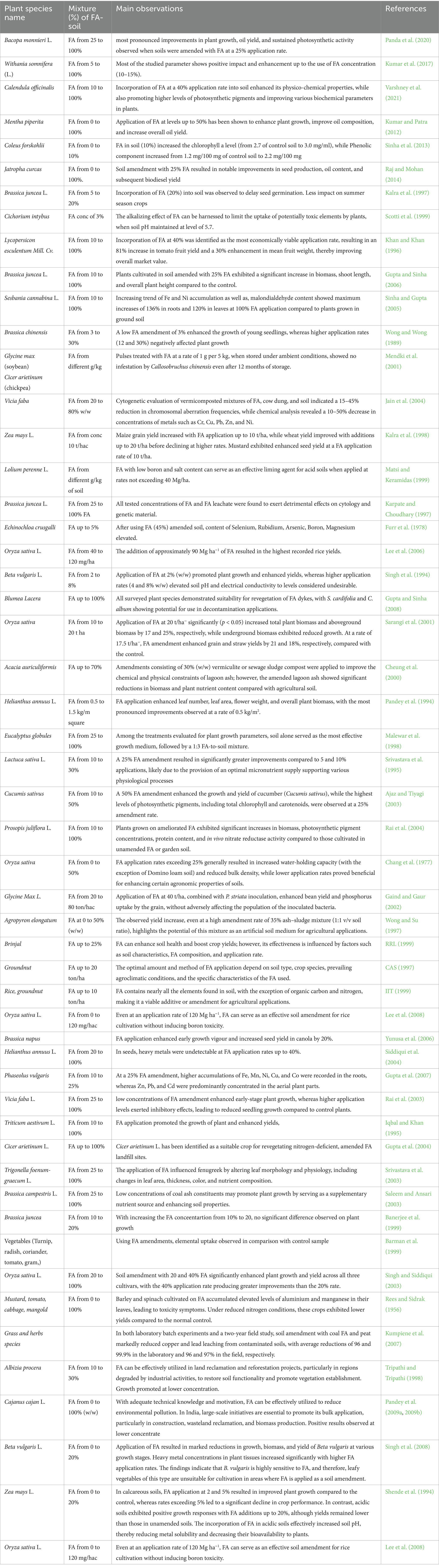

At thermal power plants, nitrogen is oxidized into gaseous compounds during combustion, which explains its absence in FA. Consequently, the use of FA in landfills can inhibit plant growth due to nitrogen deficiency. Compared with soils, FA contains a higher concentration of phosphorus; however, interactions with aluminum, iron, and calcium in the ash render this phosphorus unavailable to plants (Adriano et al., 1980). To address nitrogen deficiency in FA, leguminous plants capable of utilizing atmospheric nitrogen should be cultivated, as they host symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria (Bhattacharya and Chattapadhyaya, 2004). The use of blue-green algae further enhances soil fertility and improves physicochemical properties such as cation exchange capacity, pH, and electrical conductivity while increasing organic matter, total nitrogen, and phosphorus content. Additionally, the concentrations of metals such as copper, manganese, zinc, nickel, and iron in FA can be reduced through bioaccumulation in the tissue of the alga, Anabaena doliolum (Rai et al., 2000). FA, both individually and in combination with cyanobacteria, has been studied as a green compost for the cultivation of B. juncea, resulting in the production of adequate oil yields (Banerjee et al., 1999). Researchers have also recommended various FA-tolerant species—such as Blumea lacera, Cassia tora, and Sida cardifolia—for effective revegetation of designated landfills and lagoons (Gupta and Sinha, 2008), as listed in Table 1.

5 Reduction in chemical fertilizer usage through FA amendment

To establish the effect of using FA on the biochemical and morphological parameters of J. curcas, similar experiments performed. Study carried out using increasing FA composition in soil from 0 to 50%, observed that at 25% of FA plants grown showed much better growth in term of height, leaves area and corresponding number. Leaves of plant grown on 25% FA has higher content of nitrogen 11.73 mg/g, Protein 62.08%, carotenoids 0.27 mg/g, chlorophyll-A (0.52 mg/g), chlorophyll-b (0.41 mg/g) and total chlorophyll content 0.93 mg/g, sulphur 0.15%, sugar 1230.59 μg/g. At two stages, absorption of metals by J. curcas plants (Calcium, Cadmium, Copper, Magnesium, Lead, Iron, Manganese, Nickel and Zinc) were considered. By evaluating the metal concentration, relationship between metal uptake and plant growth evaluated, which confirmed the significant impact of metal uptake on growth of plant (Raj and Mohan, 2014).

It is observed that with the increase of composition of FA in soil, bulk density declines from 1.22 gm/ml to 0.91gm/ml, while decrease in the pH value also from 9.2 to 8.0, respectively. Further using in-vitro study, ethanolic extracts of Jatropha curcas used for antibacterial activity on Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumonia. Study results indicate broad antimicrobial activity in samples where extracts obtained from leaf samples of plants which are grown on 25 and 50% FA.

Numerous studies have documented improvements in plant dry matter accumulation, photosynthetic pigment levels, protein content, and overall growth performance at low to moderate FA concentrations (10 to 40%; Mishra et al., 2007; Panda et al., 2020; Kumar et al., 2017; Varshney et al., 2021; Kumar and Patra, 2012; Sinha et al., 2013; Raj and Mohan, 2014; Khan and Khan, 1996; Malewar et al., 1998; Wong and Su, 1997; RRL, 1999; Srivastava et al., 2003; Iqbal and Khan, 1995; Tripathi and Tripathi, 1998; Pandey et al., 2009a, 2009b; Dwivedi et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2021; Thetwar et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 1982; Tripathi et al., 2004; Khan et al., 1997).

6 Conclusion

The synthesis of research findings demonstrates that soil amendment with FA can substantially enhance crop growth and yield when applied at appropriate rates. However, elevated application rates (≥50%) have been consistently associated with reductions in growth parameters, likely due to changes in soil chemistry and potential accumulation of toxic elements. These findings emphasize the necessity of optimizing amendment rates to leverage the agronomic benefits of FA while minimizing adverse impacts on plant performance.

With the expansion of coal-based thermal power generation to meet rising industrial energy demands, the production of FA is projected to increase proportionally, intensifying concerns over its disposal. Strategic utilization of FA in agriculture, particularly for the reclamation of degraded or marginal soils, offers a viable pathway to improve soil physico-chemical properties and fertility while enhancing crop yields. This approach, however, must be guided by site-specific application thresholds to avoid excessive accumulation of heavy metals in plants and soils, ensuring that concentrations remain within safe limits for human health.

Future research should focus on establishing region-specific guidelines for FA application in agriculture, coupled with long-term monitoring of soil micronutrient and trace metal status. Such measures will enable the sustainable integration of FA into agricultural systems, balancing waste management imperatives with the need to maintain soil health, protect environmental quality, and support food security.

Author contributions

JS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support received from the leadership and management of K.R. Mangalam University, Gurugram, Haryana, India.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abhishek, S., Ghosh, A., and Pandey, B. (2024). A comprehensive review on phytoremediation of fly ash and red mud: exploring environmental impacts and biotechnological innovations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 1–28. doi: 10.1007/s11356-024-35217-2

Abhishek, S., Ghosh, A., Singh, A. A., and Pandey, B. (2025). Identification of metal-tolerant herbaceous species for phytostabilization and ecological restoration of fly ash dumpsites. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 31, 1719–1738. doi: 10.1007/s12298-025-01612-3

Adriano, D. C., Page, A. L., Elseewi, A. A., Chang, A. C., and Straugham, I. (1980). Utilization and disposal of Fly ash and coal residue in terrestrial ecosystem: a review. J. Environ. Qual. 9, 333–344. doi: 10.2134/jeq1980.00472425000900030001x

Ahmad, A., and Alam, M. M. (1997). Utilization of flyash and Paecilomyces lilacinus for the control of meloidogyne incognita. Int. J. Nematol (Int J. Nematol) 7, 162–164.

Ajaz, S., and Tiyagi, S. (2003). Effect of different concentrations of fly-ash on the growth of cucumber plant, Cucumis sativus. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 49, 457–461. doi: 10.1080/03650340310001596428

Arivazhagan, K. (2011). Effect of coal fly ash on agricultural crops. Denver, USA: World of coal ash.

Banerjee, M., Thomas, T., and Abraham, S. (1999). "use of environmentally hazardous flyash in combination with cyanobacteria as a green manure for cultivation of Brassica juncea." ecology. Environ. Conserv. 5, 107–110.

Barman, S. C., Kisku, G. C., and Bhargava, S. K. (1999). Accumulation of heavy metals in vegetables, pulse and wheat grown in fly-ash amended soil. J. Environ. Biol. 20, 15–18.

Basu, M., Bhadoria, P. B. S., and Mahapatra, S. C. (2007). Role of soil amendments in improving groundnut productivity of acid lateritic soil. Int. J. Agric. Res. 2, 87–91. doi: 10.3923/ijar.2007.87.91

Basu, M., Pande, M., Bhadoria, P. B. S., and Mahapatra, S. C. (2009). Potential fly ash utilization in agriculture: a global review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 19, 1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.12.006

Bhattacharjee, U., and Kanpal, T. C. (2002). Potential of Fly ash utilization in India. Energy 27, 151–166. doi: 10.1016/S0360-5442(01)00065-2

Bhattacharya, S. S., and Chattapadhyaya, G. N. (2004). Transformation of nitrogen during vermicomposting of Fly ash. Waste Manag. Res. 22, 488–491. doi: 10.1177/0734242X04048625

Buck, J. K., Honston, R. J., and Beimborn, W. A., (1990). "Direct seedling of anthracite refuge using coal flysha as a major soil amendment: Proceeding of the mining and reclamation." Charleston, west Virginia: Conference and Exhibition.

Budania, H. S., and Dahiya, Y. K. (2018). Prospects of Fly ash application in agriculture: a global review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 7, 397–409. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.710.043

Capp, J. P. (1978). Power plant Fly ash utilization for land reclamation in the eastern United States. Reclam. Drast. Disturb. Lands, 339–353.

Carlson, C. L., and Adriano, D. C. (1993). Environmental impacts of coal combustion residues. J. Environ. Qual. 22, 227–247. doi: 10.2134/jeq1993.00472425002200020002x

Central Electricity Authority (2023). Report on fly ash generation at coal/lignite based thermal power stations and it’s utilization in the country for the 1st half of the year 2022–2023. New Delhi: Central Pollution Control Board.

Chakraborty, P., Singh, S., Hazra, B., Majumdar, A. S., and Kumari, J. (2024). Spatial distribution, source apportionment, and health risks assessment of trace elements in pre-and post-monsoon soils in the coal-mining region of north Karanpura basin, India. Sci. Total Environ. 955:177173. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177173

Chakraborty, P., Singh, S., Wood, D. A., Hazra, B., Kumar, P., and Kumar, P. V. (2025). Spatio-temporal variation, integrated quantification of source attribution, and health risk assessment of metal trace element contamination in coal mining soils of the eastern Raniganj basin, India. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13:116567. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2025.116567

Chang, A. C., Lund, L. J., Page, A. L., and Warneke, J. E. (1977). Physical properties of fly ash amended soils. J. Environ. Qual. 6, 267–270. doi: 10.2134/jeq1977.00472425000600030007x

Cheung, K. C., Wong, J. P. K., Zhang, Z. Q., Wong, J. W. C., and Wong, M. H. (2000). Revegetation of lagoon ash using the legume species Acacia auriculiformis and Leucaena leucocephala. Environ. Pollut. 109, 75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00235-3

Christensen, G. L. (1987). “Lime stabilization of waste water sludge” in Lime for Environmental Uses, vol. 155:88–104. (ASTM digital library).

Dwivedi, S., Tripathi, R. D., Srivastava, S., Mishra, S., Shukla, M. K., Tiwari, K. K., et al. (2007). Growth performance and biochemical responses of three rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars grown in fly-ash amendment soil. Chemosphere 67, 140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.012

Furr, A. K., Parkinson, T. F., Gutenmann, W. H., Pakkala, I. S., and Lisk, D. J. (1978). Elemental content of vegetables, grains and forages field-grown on fly-ash amended soil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 26, 357–359. doi: 10.1021/jf60216a058

Gaind, S., and Gaur, A. C. (2002). Impact of fly ash and phosphate solubilising bacteria on soybean productivity. Bioresource Technol. 85, 313–315. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00088-3

Ghodrati, M., Sims, J. T., and Vasilas, B. S. (1995). Enhancing the benefits of fly ash as a soil amendment by preleaching. J. Water Soil Air Pollut. 81, 244–252.

Goetz, L. (1983). Radiochemical techniques applied to laboratory studiespf water leaching of heavy metals from coal flyash. Water Sci. Technol. 15, 25–47. doi: 10.2166/wst.1983.0075

Goyal, D., Kaur, K., Garg, R., Vijayan, V., and Nanda, S. K. (2002). Industrial fly ash as a soil amedment agent for raising forestry plantations. Fundam. Adv. Mat. Energy Conv., 251–260.

Gupta, A. K., Dwivedi, S., Sinha, S., Tripathi, R. D., Rai, U. N., and Singh, S. N. (2007). Metal accumulation and growth performance of Phaseolus vulgaris grown in fly-ash amended soil. Bioresour. Technol. 98, 3404–3407. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.08.016

Gupta, G. S., Prasad, G., and Singh, V. H. (1990). Removal of chrome dye from aqueous solutions by mixed absorbant: flyash and coal. Water Res. 24, 45–50. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(90)90063-C

Gupta, D. K., Rai, U. N., Sinha, S., Tripathi, R. D., Nautiyal, B. D., Rai, P., et al. (2004). Role of Rhizobium (CA-1) inoculation in increasing growth and metal accumulation in Cicer arietinum L. growing under fly-ash stress condition. Bull. Environ. Contamin. Toxicol. 73, 424–431. doi: 10.1007/s00128-004-0446-5

Gupta, A. K., and Sinha, S. (2006). Role of Brassica juncea L. Czern. (var. vaibhav) in the phytoextraction of Ni from soil amended with fly-ash: selection of extractant for metal bioavailability. J. Hazardous Mat. 136, 371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.12.025

Gupta, A. K., and Sinha, S. (2008). Decontamination and/or revegetation of fly ash dykes through naturally growing plants. J. Hazardous Mat. 153, 1078–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.09.062

Hodgson, D. R., and Holliday, R. (1966). The agronomic properties of pulverized fly ash. Chem. Ind. 20, 785–790.

IIT (1999). Utilization of Fly ash and organic wastes in restoration of crop land ecosystem. Kharagpur: Fly Ash Mission.

Iqbal, J., and Khan, M. W. (1995). Effect of fly-ash on plant growth, yield and leaf pigment of wheat. Indian J. Plant Pathol. 13, 20–25.

Jain, K., Singh, J., Chauhan, L. K. S., Murthy, R. C., and Gupta, S. K. (2004). Modulation of fly- ash-induced genotoxicity in Vicia fava by vermicomposting. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 59, 89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2004.01.009

Jala, S., and Goyal, D. (2006). Fly ash as a soil ameliorant for improving crop production-a review. Bioresour. Technol. 97, 1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.09.004

Jeyarajp, N. J., and Sankararajan, V. (2024). Study on the characterization of fly ash and physicochemical properties of soil, water for the potential sustainable agriculture use – a farmer’s perspectives. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 15, 95–106. doi: 10.1556/1848.2023.00661

Jiang, R. F., Yang, C. G., and Su, D. C. (1999). Coal Fly ash and lime stabilized biosolids as an ameliorant for boron deficient soils. Environ. Technol. 20, 645–659. doi: 10.1080/09593332008616860

Jones, L. H., and Lewis, A. V. (1960). Weathering of flyash. Nature 185, 404–405. doi: 10.1038/185404a0

Kalra, N., Jain, M. C., Joshi, H. C., Choudhary, R., Harit, R. C., Vatsa, B. K., et al. (1998). Fly-ash as a soil conditioner and fertilizer. Bioresour. Technol. 64, 163–167. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(97)00187-9

Kalra, N., Joshi, H. C., Chaudhary, A., Chaudhary, R., and Sharma, S. K. (1997). Impact of flyash incorporation in soil on germination of crops. Bioresour. Technol. 61, 39–41. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(97)84696-2

Karpate, R. R., and Choudhary, A. D. (1997). Effect of thermal power station’s waste on wheat. J/. Environ. Biol. 18, 1–10.

Kene, D. R., Lanjewar, S. A., and Ingole, B. M. (1991). Effect of application of Fly ash on physico-chemical properties of soils. J. Soils Crops 1, 11–18.

Khan, M. R., and Khan, M. W. (1996). The effect of Fly ash on plant growth and yield of tomato. Environ. Pollut. 92, 105–111. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(95)00098-4

Khan, N. R., Khan, M. W., and Singh, K. (1997). Management of root-knot disease of tomato by the application of flyash in soil. Plant Pathol. 46, 33–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.1997.d01-199.x

Kishor, P., Ghosh, A. K., and Kumar, D. (2010). Use of Fly ash in agriculture: a way to improve soil fertility and its productivity. Asian J. Agric. Res. 4, 1–14. doi: 10.3923/ajar.2010.1.14

Kumar, V., Mathur, M., and Sharma, P. K. (2000). Fly ash management: Vision for the new millennium. New Delhi: FAM & CBIP.

Kumar, K. V., and Patra, D. D. (2012). Alteration in yield and chemical composition of essential oil of Mentha piperita L. plant: effect of fly ash amendments and organic wastes. Ecol. Eng. 47, 237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.06.019

Kumar, T., Prasad, S. V. K., and Kanungo, V. K. (2017). Impact of coal Fly ash on growth of Withania somnifera (Linn.) Dunal. Indian J.Sci.Res. 13, 25–28. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14146/3795

Kumpiene, J., Lagerkvist, A., and Maurice, C. (2007). Stabilization of Pb- and cu- contaminated soil using coal fly ash and peat. Environ. Pollut. 145, 365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.01.037

Kuznia, M. (2025). A review of coal Fly ash utilization: environmental, energy and material assessment. Energies 18:52. doi: 10.3390/en18010052

Lau, S. S. S., and Wong, J. W. C. (2006). Toxicity evaluation of weathered coal fly ash amended manure compost. Water Air Soil Pollut. 128, 243–254. doi: 10.1023/A:1010332618627

Lee, H., Ha, H. S., Lee, C. H., Lee, Y. B., and Kim, P. J. (2006). Fly-ash effect on improving soil properties and rice productivity in Korean paddy soils. Bioresour. Technol. 97, 1490–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.06.020

Lee, S. B., Lee, Y. B., Lee, C. H., Hong, C. O., Kim, P. J., and Yu, C. (2008). Characteristics of boron accumulation by fly ash application in paddy soil. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 5928–5932. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.11.022

Malewar, G. U., Adsul, P. B., and Ismail, S. (1998). Effect of different combinations of fly-ash and soil on growth attributes of forest and dryland fruit crops. Indian J. Forest. 21, 124–127. doi: 10.54207/bsmps1000-1998-V5650X

Matsi, T., and Keramidas, V. Z. (1999). Fly-ash application on two acid soils and its effect on soil salinity, pH, B, P, and on ryegrass growth and composition. Environ. Pollut. 104, 107–112. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00145-6

Matti, S. S., Mukhopadhyay, T. M., Gupta, S. K., and Banerjee, S. K. (1990). Evaluation of Fly ash as a useful material in agriculture. J. Ind. Soc. Soil Sci 38, 342–344.

McBride, A. C., and West, T. O. (2005). Estimating net CO2 emission from agricultural lime applied to soil in the US. Proceedings of the fall meeting. Durham, NC, USA: American Geophysical Union.

Mendki, P. S., Maheshwari, V. L., and Kothari, R. M. (2001). Fly-ash as a post-harvest preservative for five commonly utilized pulses. Crop Protect. 20, 241–245. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00141-1

Mishra, M., Sahu, R. K., and Padhy, R. N. (2007). Growth, yield and elemental status of rice (Oryza sativa) grown in fly ash amended soils. Ecotoxicology 16, 271–278. doi: 10.1007/s10646-006-0128-7

Mishra, L. C., and Shukla, K. N. (1986). Effects of fly ash deposition on growth, metabolism and dry matter production of maize and soyabean. Environ. Poll. Series Ecol. Biol. 42, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/0143-1471(86)90040-1

Mittra, B. N., Karmakar, S., and Swaine, D. M. (2003). Fly ash a potential source of soil amendment and component of integrated plant nutrient supply system. Fuel 84, 1447–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2004.10.019

Montes-Hernandez, G., Pérez-López, R., Renard, F., Nieto, J. M., and Charlet, L. (2009). Mineral sequestration of CO2 by aqueous carbonation of coal combustion flyash. J. Hazard. Mater. 16, 1347–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.104

Narayanasamy, P. (2002). Lignite fly ash as eco-friendly insecticides. Proceedings of the Second National Seminar on Fly-ash. Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar, pp. 42–50.

Narayanasamy, P. (2003). Flly ash in the plant protection scenario of agriculture. New Delhi: Goverment of India.

Natusch, D. F. S., and Wallace, J. R. (1974). Urban aerosol toxicity: the influence of particle size. Science 186, 695–699. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4165.695

Ou, Y., Ma, S., Zhou, X., Wang, X., Shi, J., and Zhang, Y. (2020). The effect of a Fly ash-based soil conditioner on corn and wheat yield and risk analysis of heavy metal contamination. Sustainability 12:7281. doi: 10.3390/su12187281

Page, A. L., Elseewi, A. A., and Straughan, I. R. (1979). Physical and chemical properties of fly ash from coal fired power plants with reference to environmental impacts. Residue Rev. 71, 83–120.

Panda, D., Barik, J. R., Barik, J., Behera, P. K., and Dash, D. (2020). Suitability of Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri L.) cultivation of Fly ash amended soil for better growth and oil content. Int. J. Phytoremed., 1–9. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2020.1791052

Panday, K. K., Prasad, G., and Singh, V. N. (1985). Copper (II) removal from aqueous solution by flyash. Water Res. 19, 869–873. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(85)90145-9

Pandey, V. C. (2008). “Studies on some leguminous plants under the stress of Fly-ash and coal residues Released from National Thermal Power Corporation Tanda” in Studies on some leguminous plants under the stress of Fly-Avadh University Faizabad, India. Ph.D. thesis. Dr. R.M.L. Avadh University. Faizabad, India: National Digital Library of India.

Pandey, V. C., Abhilash, P. C., and Singh, N. (2009a). The Indian perspective of utilizing fly ash in phytoremediation, phytomanagement and biomass production. J. Environ. Manag. 90, 2943–2958. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.05.001

Pandey, V. C., Abhilash, P. C., Upadhyay, R. N., and Tewari, D. D. (2009b). Application of fly ash on the growth performance and translocation of toxic heavy metals within Cajanus cajan L.: implication for safe utilization of fly ash for agricultural production. J. Hazard. Mat. 255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.11.016

Pandey, V., Mishra, J., Singh, S. N., Singh, N., Yunus, M., and Ahmad, K. J. (1994). Growth response of Helianthus annuus L. grown on fly-ash amended soil. J. Environ. Biol. 15, 117–125.

Patil, S. N., Sanap, S. R., Wagh, M. A., Patil, N. P., Bhagmare, H. M., Solanki, P. V., et al. (2013). Utilization of coal fly ash as a fertilizer for cash crop plants and check its effect on the growth of Methi, spinach, Dhania. J. Environ. Sci. 6, 23–25.

Phung, H. T., Lam, H. V., Lund, H. V., and Page, A. L. (1979). "the practice of leaching boron and salts from fly ash amended soil." water. Water Air Soil Pollut 12, 247–254. doi: 10.1007/BF01047127

Pujari, G. K., and Dash, P. M. (2006). Fly ash problem and management aspect. Environ. Newsl. Centre Environ. Stud. 3, 1–8.

Rai, U. N., Gupta, D. K., Akhtar, M., and Pal, A. (2003). Performance of seed germination and growth of Vicia faba L. in fly-ash amended soil. J. Environ. Biol. 24, 9–15

Rai, U. N., Pandey, K., Sinha, S., Singh, A., Saxena, R., and Gupta, D. K. (2004). Revegetating fly-ash landfills with Prosopis juliflora L.: impact of different amendments & Rhizobium inoculation. Environ. Int. 30, 293–300. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00179-X

Rai, U. N., Tripathi, R. D., Singh, N., Kumar, A., Ali, M. B., Pal, A., et al. (2000). Amelioration of fly-ash by selected nitrogen fixing blue green algae. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 64, 294–301. doi: 10.1007/s001289910043

Raj, S., and Mohan, S. (2014). Approached for improved plant growth using fly ash amended soil. Inter. J. of Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 4, 1–6.

Rajakumar, G. R., and Patil, S. V. (2019). Effect of Fly ash on growth and yield of crops with special emphasis on. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 8, 127–137. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2019.808.016

Rautaray, S. K., Ghosh, B. C., and Mittra, B. N. (2003). Effect of fly ash, organic wastes and chemical fertilizers on yield, nutrient uptake, heavy metal content and residual fertility in a rice mustard cropping sequence under acidlateritic soils. Bioresour. Technol. 90, 275–283. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(03)00132-9

Rees, W. J., and Sidrak, G. H. (1956). Plant nutrition on fly-ash. Plant Soil 8, 141–159. doi: 10.1007/BF01398816

Rusănescu, C. O., and Rusănescu, M. (2023). Application of Fly ash obtained from the incineration of municipal solid waste in agriculture. Appl. Sci. 13:3246. doi: 10.3390/app13053246

Sajwan, K. S. (1995). The effect of flyash/sewage sludge mixtures and application rate on biomass production. J. Environ. Sci. Health 30, 1327–1337. doi: 10.1080/10934529509376267

Saleem, S., and Ansari, A. A. (2003). Effect of aqueous coal-ash leachate on growth and yield of Brassica campestris L. cv. Kranti Chapka. Int. J. Plant Res. 16, 77–80.

Sao, S., Gothalwal, R., and Thetwari, L. K. (2007). Effects of flyash and plant hormones treated soil on the increased protein and amino acid contents in the seed of ground nut. Asian J. Chem. 19, 1023–1026.

Sarangi, P. K., Mahakur, D., and Mishra, P. C. (2001). Soil biochemical activity and growth response of rice Oryza sativa in fly ash amended soil. Bioresour. Technol. 76, 199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00127-9

Schnappinger, M. F., Martens, D. C., and Plank, C. D. (1975). Zinc availability as influenced by applicationof flyash to soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 9, 258–261. doi: 10.1021/es60101a009

Schutter, M. E., and Fuhrmann, J. J. (2001). "soil microbial community response to Fly ash amendment as revealed by analysis of whole soils and bacterial isolates." soil biology and biochemistry (soil biol). Biochemist 33, 1947–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00123-7

Scotti, A., Silva, S., and Botteschi, G. (1999). Effect of fly ash on the availability of Zn, cu, Ni and cd to chicory. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 72, 159–163. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(98)00170-4

Sharma, M. P., Tanu, U., and Adholeya, A. (2001). “Growth and yield of Cymbopogon martini as influenced by flyash, AM fungi inoculation and farmyard manure application” in 7th international symposium on soil and plant analysis (Edmonton, AB, Canada).

Sharma, Y. C., and Uma Singh, S. N. (2007). Fly ash for the removal of Mn(II) from aqueous solutions and wastewaters. Chem. Eng. J. 132, 319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2007.01.018

Shende, A., Juwarkar, A. S., and Dara, S. S. (1994). Use of fly ash in reducing heavy metal toxicity to plants. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 12, 221–228. doi: 10.1016/0921-3449(94)90010-8

Siddiqui, S., Ahmad, A., and Hayat, S. (2004). The fly ash influenced the heavy metal status of the soil and the seeds of sunflower – a case study. J. Environ. Biol. 25, 59–63

Siddiqui, Z. A., Khan, M. R., and Ahamad, L. (2022). Effects of fly ash on growth, productivity, and diseases of crop plants. Alīgarh, India: Elsevier.

Singh, R. P., and Agarawal, M. (2010). Effect of different sewage sludge applications on growth and yield of Vigna radiata L. field crop: metal uptake by plant. Ecol. Eng. 36, 969–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2010.03.008

Singh, I., Dhillon, B. S., and Kaur, M. (2021). Effect of Fly ash and phosphorus on growth and yield of Bt cotton (Gossypium hirustum L.). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 10, 2601–2609. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2021.1001.303

Singh, S. N., Kulshreshtha, K., and Ahmad, K. J. (1997). Impact of fly ash soil amendment on seed germination, seedling growth and metal composition of Vicia faba L. Ecol. Ecol. Eng. 9, 203–208. doi: 10.1016/S0925-8574(97)10004-0

Singh, A., Sharma, R. K., and Agrawal, S. B. (2008). Effects of fly ash incorporation on heavy metal accumulation, growth and yield responses of Beta vulgaris plants. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 7200–7207. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.12.064

Singh, L. P., and Siddiqui, Z. A. (2003). Effects of fly-ash and Helminthosporium oryzae on growth and yield of three cultivars of rice. Bioresour. Technol. 86, 73–78. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00111-6

Singh, N. B., and Singh, M. (1986). Effect of fly-ash application on saline soil and on yield components, yield and uptake of NPK of rice and wheat at varying fertility levels. Ann. Agric. Res. 7, 245–257.

Singh, A. K., Singh, R. B., Sharma, A. K., Gauraha, R., and Sagar, S. (1997). Response of fly-ash on growth of Albizia procera in coal mine spoil and skeletal soil. Environ. Ecol. 15, 585–591.

Singh, N., Singh, S. N., Yunus, M., and Ahmad, K. J. (1994). Growth response and elemental accumulation in Beta vulgaris L. raised in fly-ash amended soil. Ecotoxicology. 3, 287–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00117993

Sinha, S., and Gupta, A. K. (2005). Translocation of metals from fly-ash amended soil in the plant of Sesbania cannabina L. Ritz: effect on antioxidants. Chemosphere 61, 1204–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.063

Sinha, D., Sharma, S., and Dwivedi, M. K. (2013). The impact of fly ash on photosynthetic activity and medicinal property of plants. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2, 382–388.

Srivastava, S., Ansari, A. A., Hashmi, F., and Khatoon, A. (2003). Effect of fly-ash on leaf traits of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.). Int. J. Plant Res. 16, 73–76.

Srivastava, K., Farooqui, A., Kulshrestha, K., and Ahmad, K. J. (1995). Effect of amendment soil on growth of Lactuca sativa. J. Indust. Pollut. Control 16, 93–96.

Thetwar, I. K., Sahu, D. P., and Vaishnava, M. M. (2006). Analysis of Sesamum indicum seed oil from plants grown on flyash amended acidic soil. Asian J. Chem. 18, 481–484.

Tiwari, K. N., Sharma, D. N., and Sharma, V. K. (1982). Evaluation of flyash and pyrite for sodic soil rehabilitation in UP, India. Arid Soil Res. Rehabil. 6, 117–126.

Tripathi, S., and Tripathi, A. (1998). Impact of flyash, light and shade environments on growth and chemical response of Albizia procera and Acacia nilotica. J. Environ. Biol. 19, 33–41.

Tripathi, R. D., Vajpayee, P., Singh, N., Rai, U. N., Kumar, A., Ali, M. B., et al. (2004). Efficacy of various amendments for amelioration of fly-ash toxicity: growth performance and metal composition of Cassia siamea Lamk. Chemosphere 54, 1581–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.09.043

Vajpayee, P., Rai, U. N., Choudhary, S. K., Tripathi, R. D., and Singh, S. N. (2000). Management of fly-ash landfills with Cassia surattensis Burm: a case study. Bull. Environ. Contamin. Toxicol. 65, 675–682. doi: 10.1007/s0012800176

Varshney, A., Dahiya, P., and Mohan, S. (2021). Effects of Fly ash amended soil on biochemical attributes and antioxidant responses of medicinally potent plant Calendula Officinalis. Res. Square 1, 1–16. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-174780/v1

Wong, J. W. C., and Su, D. C. (1997). The growth of Agropyron elongatum in an artificial soil mix from coal fly-ash and sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 59, 57–62. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(96)00126-5

Wong, M. H., and Wong, J. W. C. (1986). Effects of fly ash on soil microbial activity. Environ. Pollut. 40, 127–144.

Wong, M. H., and Wong, J. W. C. (1989). Germination and seedling growth of vegetable crops in fly-ash amended soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 26, 23–25. doi: 10.1016/0167-8809(89)90035-2

Keywords: agriculture, coal, fly ash, solid waste, waste management, soil health, crop yield

Citation: Singh J, Raj S and Kaur DP (2025) Exploration of the utilization of fly ash in medicinal plant cultivation. Front. Sustain. 6:1661849. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1661849

Edited by:

Ales Lapanje, Institut Jožef Stefan (IJS), SloveniaReviewed by:

Shubham Abhishek, Central Institute of Mining and Fuel Research, IndiaCopyright © 2025 Singh, Raj and Kaur. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seema Raj, c2VlbWFyYWoxOTgwQHlhaG9vLmNvLmlu

Joginder Singh

Joginder Singh Seema Raj

Seema Raj Dilraj Preet Kaur

Dilraj Preet Kaur