- 1Aachen-Maastricht Institute for Biobased Materials (AMIBM), Maastricht University, Geleen, Netherlands

- 2Faculty of Engineering, Mondragón Unibertsitatea, Arrasate, Mondragón, Spain

- 3Henning4future, Aachen, Germany

Introduction: This study employed a systems thinking approach to explore the complex and dynamic interactions between sustainability initiatives, and employees' subsequent perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. It aims to address limitations in existing literature, arising from methodological approaches that fail to capture the nuances in employees' responses, and a lack of knowledge integration.

Methods: Insights from neo-institutional theory, sensemaking, and attribution theory were integrated with findings from 46 previous studies and 50 empirical qualitative data points though Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) to reveal feedback mechanisms and temporal dynamics that potentially shape employees' responses to sustainability initiatives.

Results and discussion: Two main reinforcing feedback loops were identified: one supporting continued engagement and implementation of sustainability initiatives, and another hindering initiatives through negative perceptions. A balancing loop revealed how increasing employee knowledge, experience and scrutiny can lead to more critical perceptions over time. The analysis suggests that more symbolic sustainability initiatives can foster initial employee engagement and support for future sustainability implementation in the early stages of a sustainability journey. However, this initial positive momentum can be fragile and transition into a "vulnerability period", where initial enthusiasm may transition to frustration if perceived impacts do not meet employees' growing expectations. This potential progression follows a “Fixes that Fail” systems archetype.

Conclusion: In this study, the use of CLDs provides a more temporally-bound and integrated understanding of employees' responses to sustainability initiatives. Therefore, this study challenges the simplistic dichotomy of positive versus negative effects of sustainability initiatives, revealing a more nuanced interplay between individual differences and organizational factors in shaping progressive employee (dis)engagement. Ultimately, the findings suggest that symbolic initiatives are not inherently bad, but sustaining employee engagement requires organizations to “walk their talk” by implementing consistent initiatives whose perceived impact can withstand increasing employee scrutiny.

1 Introduction

Employees play a vital role in advancing an organization's commitment to the environment and society. They not only help to implement and advocate for sustainability initiatives but also encourage future efforts. Frequently, they also experience the impacts and changes these initiatives bring or the consequences of the their absence (Süßbauer et al., 2019; Onkila and Sarna, 2022). This dual role of employees as both drivers and recipients of sustainability efforts highlights their significance as key internal stakeholders in driving change toward sustainability and fostering a culture of environmental and social responsibility within the workplace. The growing recognition of the importance of employees in an organization's sustainability journey has led to increasing research focused on exploring how employees affect and are affected by sustainability initiatives (Onkila and Sarna, 2022; Aguinis et al., 2024).

A growing body of research focuses on understanding the effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives on employees' outcomes (Donia et al., 2017; De Roeck and Maon, 2018; Glavas and Kelley, 2014). Current studies have investigated an impressive number of variables, broadly categorized into employees' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward CSR, which are influenced by individual, organizational, and system-level factors (Aguinis et al., 2024; De Roeck and Maon, 2018). Two recent review papers provide a detailed overview of the topic, including the limitations of this body of research (Yassin and Beckmann, 2024; Aguinis et al., 2024).

Despite the acknowledged complexity of employees' responses to sustainability initiatives, limitations in methodology and knowledge integration continue to exist (Rupp et al., 2024). Most studies in the field of micro-CSR have investigated this topic using a linear approach, mainly quantitatively and through a cross-sectional design (Akhouri and Chaudhary, 2019; Onkila and Sarna, 2022). According to a recent literature review, approximately 80% of the studies in the field were based on quantitative or mixed methods in 2023 (Yassin and Beckmann, 2024). Additionally, studies that employ such a research approach tend to investigate relationships between variables that represent either positive or negative employees' responses toward CSR, with a predominant focus on variables that represent positive, or highly valued, attitudes and behaviors. This poses important challenges to academic understanding for two reasons. First, although cross-sectional studies often generate repetitive and comparative findings, the results provide a one-time snapshot of the moment of measurement, thus failing to capture the nuances and changes in employees' perceptions (Akhouri and Chaudhary, 2019; Yassin and Beckmann, 2024; Onkila and Sarna, 2022). Second, the literature often overlooks negative outcomes, with most previous studies investigating and interpreting employees' responses to sustainability initiatives as either positive or negative (Aguinis et al., 2024). This approach fails to recognize the complexity and potential nuances involved in the process, resulting in a limited and unrealistic understanding about the impacts of sustainability-oriented initiatives on employees' perceptions and outcomes (Babu et al., 2020; Yassin and Beckmann, 2024).

To address these gaps associated with methodology and knowledge integration, this study employs systems thinking lenses and tools to integrate insights and capture the dynamic complexity of the relationships between employees and sustainability initiatives. By doing so, this study provides a more temporally bound, nuanced, and integrated understanding of the topic. Based on 50 empirical data points obtained through semi-structured interviews and qualitative survey (QS) responses, and supported by 46 previously published research papers, this study answers the following research question: how can employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviors regarding sustainability-oriented initiatives evolve over time?

This paper is structured as follows: subsection 1.1 outlines the theoretical framework of the study. Section 2 details the research methods employed, while section 3 presents the results. Section 4 offers a discussion and situates the findings within the context of existing research, providing insights to practitioners. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper with an overview of the results, their main contributions, limitations and suggestions for future research. It is important to note that while existing literature predominantly explores employees' perceptions of CSR (i.e., micro-CSR), this research adopts a broader lens by considering any sustainability initiative that aimed at improving a company's environmental or social outcomes (hereafter also referred to as “sustainability initiatives” or “sustainability practices”). This focus applies regardless of their implementation approach (top-down or bottom-up), alignment with organizational goals, or level of complexity.

1.1 Theoretical foundation

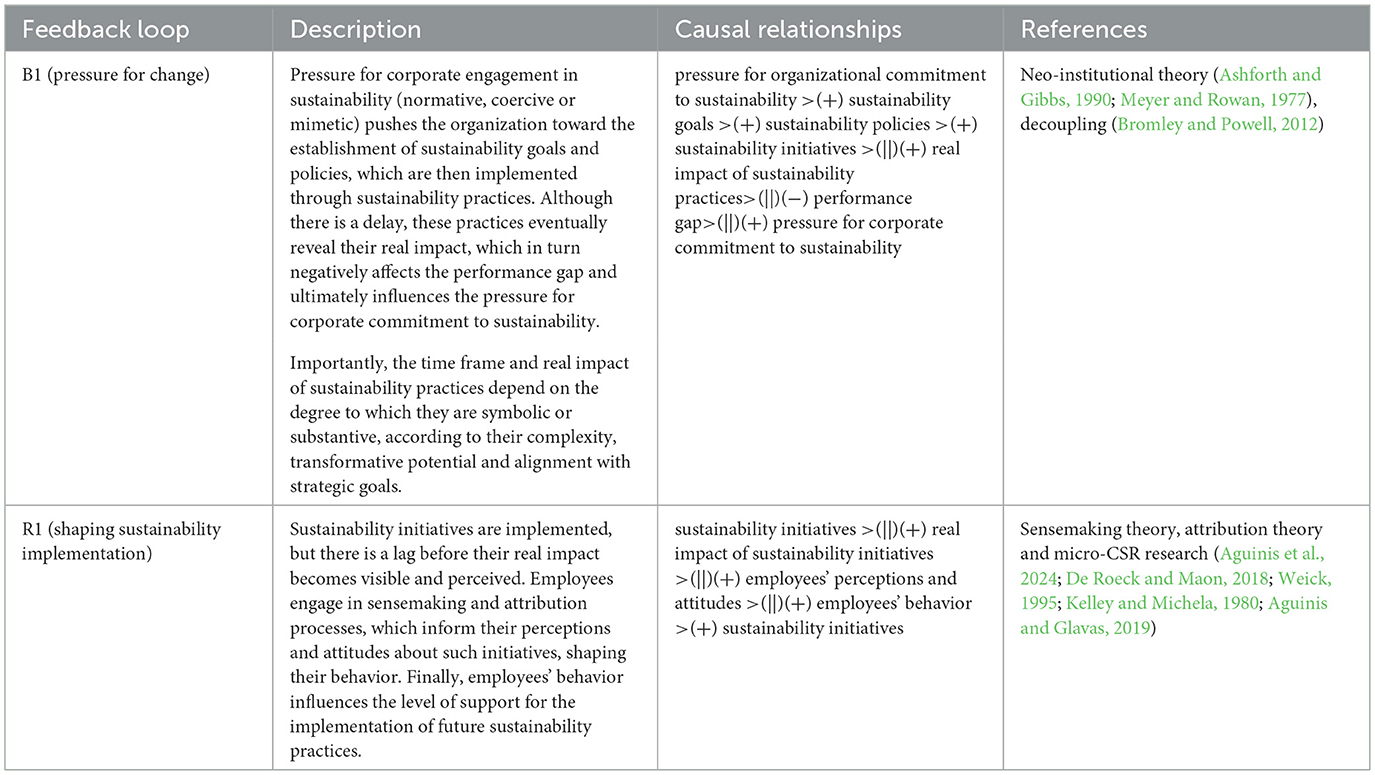

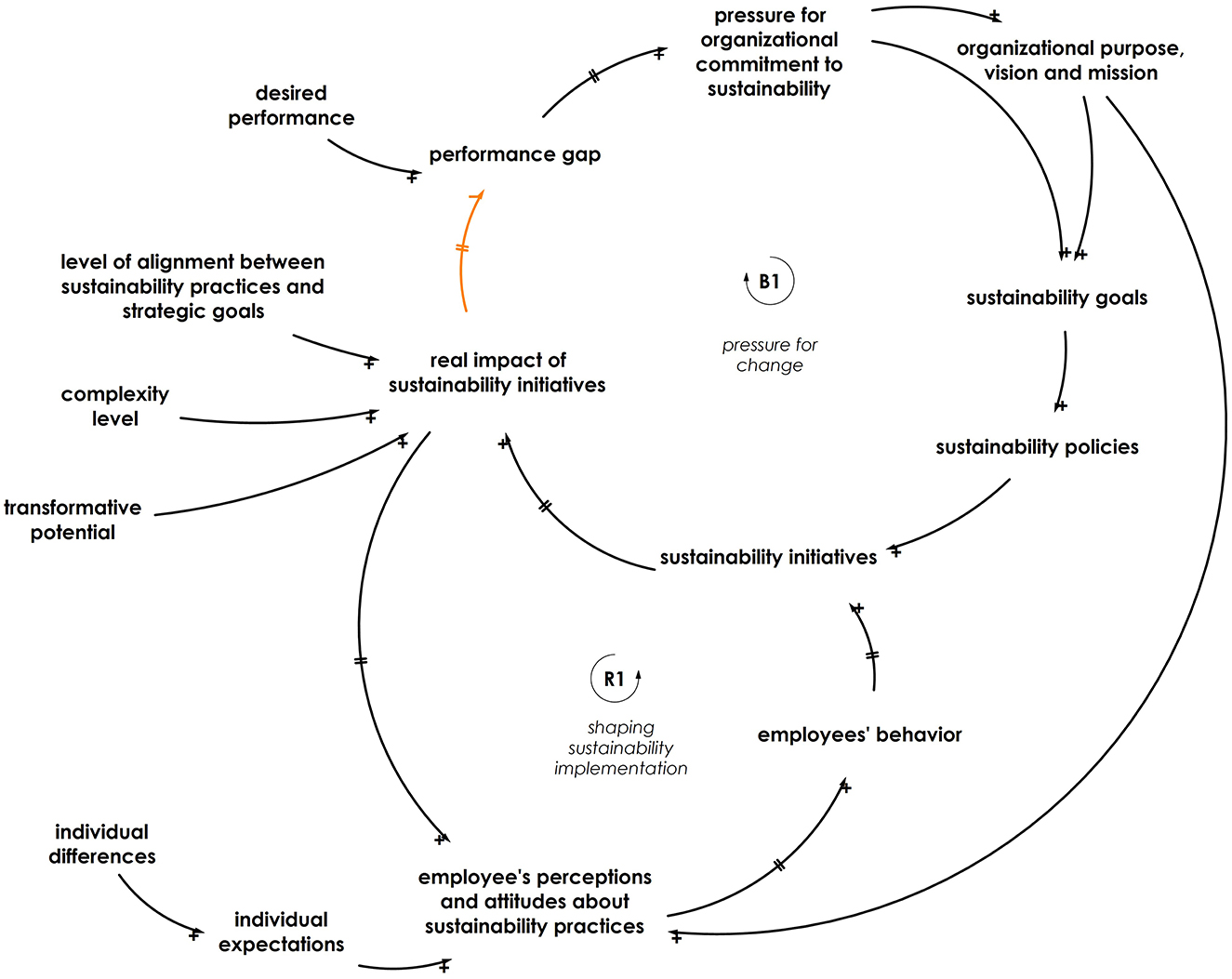

The theoretical framework of this study, illustrated in Figure 1, presents an overview of the interplay between external pressures, organizational responses and employees' outcomes through a systems thinking approach. Therefore, in this section, the rationale that guided the development of the theoretical framework will be outlined. First, basic concepts, tools and notations related to systems thinking are explained, thereby justifying the use of such approach in this research. Then, to guide the readers through the theoretical framework depicted in Figure 1, key insights from neo-institutional theory, attribution theory and micro-CSR literature are gradually elucidated and cross-referenced in both Figure 1 and Table 1.

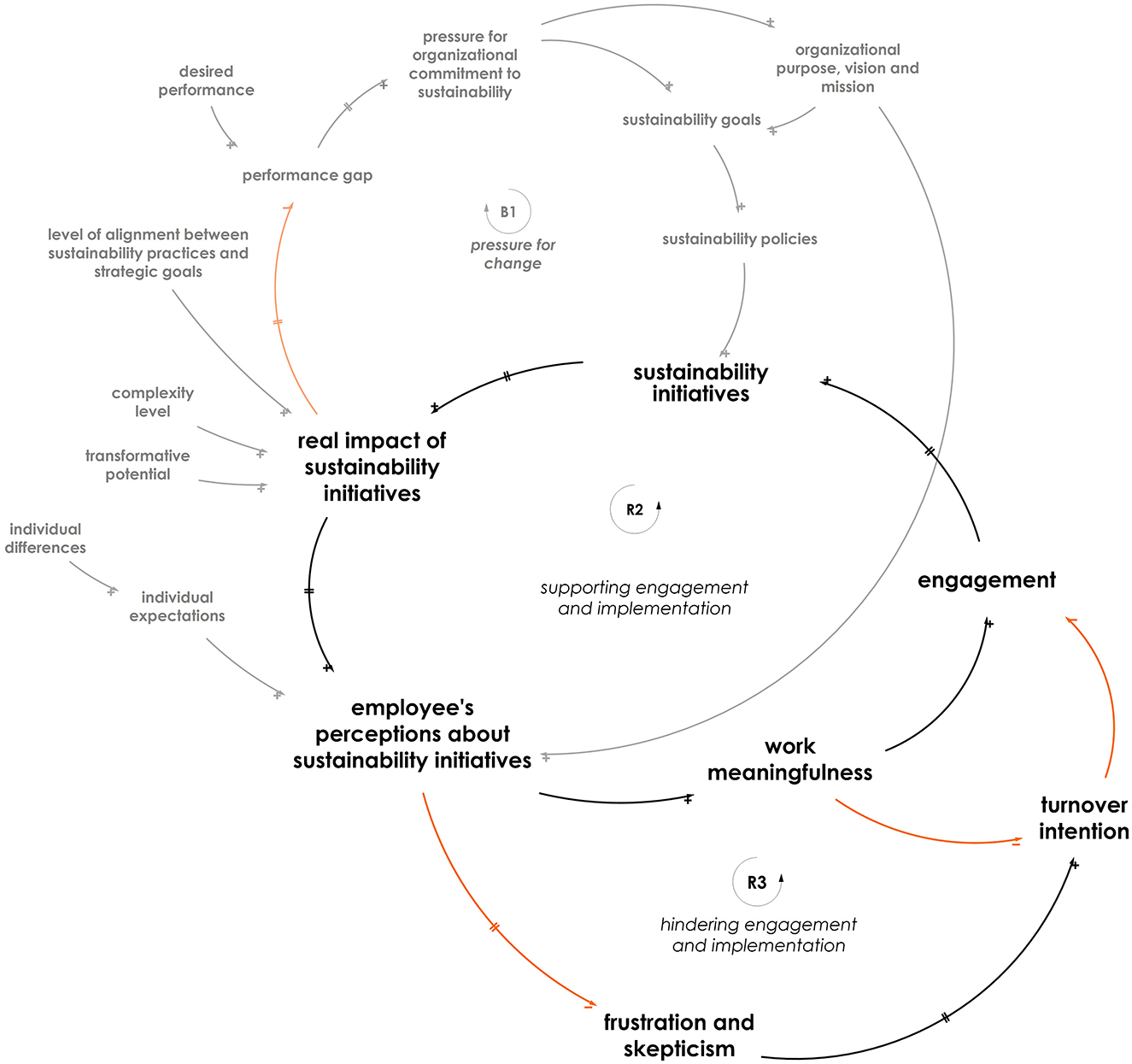

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of this study. The link polarity indicates how two variables change in relation to each other, i.e., a positive (“+”) polarity means that the variables change in the same direction, while a negative (“−”) polarity denotes the opposite. Red arrows highlight negative polarity. Double lines perpendicular to the arrows indicate a substantial time delay in that causal relationship.

1.1.1 Systems thinking as the integrative framework

Despite the intricate dynamics between sustainability initiatives, and employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviors, this phenomenon has not yet been explored through more integrative, methodological approaches, such as systems thinking. Systems thinking is an interdisciplinary approach that offers insights into how various elements of a system interact with each other over time, instead of focusing on the analysis of individual and isolated elements (Kim, 2000; Richardson, 1995). Consequently, systems thinking approaches are increasingly employed by practitioners and researchers in diverse fields of knowledge to tackle “wicked problems”, such as those related to sustainable development, where trade-offs between economic, environmental and social aspects need to be managed (Williams et al., 2017; Grewatsch et al., 2021). In organizational contexts, systems thinking enables companies to guide organizational transformations in complex environments and anticipate unintended consequences (Bansal and Birkinshaw, 2025; Grewatsch et al., 2021). In research, his approach allows the integration of findings derived from different theories and levels of analysis, accounts for temporal aspects, and illustrates potential behavioral changes over time in the system or problem under investigation. Given these advantages systems thinking serves as a valuable framework to better comprehend interconnected factors influencing employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviors triggered by sustainability initiatives in the workplace.

Rooted in systems thinking, causal loop diagrams (CLDs) are dynamic thinking tools that visually communicate the dynamic complexity of a problem or system (Kim, 2000; Sterman, 2000). CLDs consist of variables (i.e., dynamic elements) connected by links that represent hypothetical causal connections between variables, which often stem from the mental model of various stakeholders (e.g., employees, managers, and domain experts) and are supported by different degrees of scientific evidence (Sterman, 2000; Uleman et al., 2024). Each causal link is represented by arrows, indicating the direction of the effect, while the link polarity shows how two variables change in relation to each other: a positive (“+”) polarity means that the variables change in the same direction, while a negative (“−”) polarity indicates the opposite. Other important notations in CLDs are delays (||), which represent the relevant time lags in specific links. Additionally, feedback loops are a crucial feature of CLDs, describing sequences of cause-effect relations that begin and end with the same variable, resulting in either reinforcing (“R”) or balancing (“B”) patterns of behavior. Therefore, feedback loops are basic building blocks of dynamic systems (Sterman, 2000; Kim, 2000; Uleman et al., 2024). In this study, CLDs enable the integration of insights from neo-institutional, sensemaking and attribution theories into a unified framework.

Having established the basic concepts of systems thinking and CLD notations, the relevant theories and concepts integrated into the theoretical framework of this study (Figure 1) are presented. First, the nature of sustainability initiatives in organizations is presented, based on insights from neo-institutional theory. Subsequently, the focus shifts to the individual level of analysis, highlighting sensemaking and individual processes, such as motive attributions, that occur when employees are affected by sustainability initiatives.

1.1.2 Balancing external pressure through sustainability initiatives

The current environmental, economic and societal challenges intensify pressures on organizations to commit to principles that embrace not only economic prosperity, but also environmental and social responsibility (Helmig et al., 2016; Lubin and Esty, 2010). According to insights from neo-institutional theory, such pressures stem from coercive, mimetic or normative forces (Di Maggio and Powell, 1983; Bhuiyan et al., 2025). Coercive forces refer to regulations or laws imposed by powerful institutions that force firms to conform to certain standards. Mimetic pressures are related to the firms' inclination to imitate practices of legitimate and successful competitors (e.g., creating sustainability departments). Normative pressures are related to professionalization, and the broadly expected standards, such as international practices or norms on environmental behavior (Di Maggio and Powell, 1983).

To navigate such pressures and maintain legitimacy, companies can adapt their corporate purpose, vision, mission, goals, policies and practices with sustainability principles. However, the character of such actions can range from symbolic to substantive (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Ashforth and Gibbs, 1990; Bromley and Powell, 2012). More symbolic actions are legitimacy-seeking. They primarily offer ceremonial signs of corporate engagement with sustainability in short term and are decoupled from strategic goals; therefore, they fail to promote the deep organizational change needed to address pressing sustainability challenges (Truong et al., 2021; Schons and Steinmeier, 2016). Oppositely, more substantive efforts are highly aligned with strategic goals, requiring significant investments of time, resources and organizational commitment. Driven by efficiency and adaptation purposes, such efforts aim to drive meaningful changes in organizational practices. Given the higher level of complexity, the impacts of more substantial actions are delivered in the longer term, gradually decreasing the pressure for corporate engagement with sustainability (Hyatt and Berente, 2017; Ashforth and Gibbs, 1990; Schons and Steinmeier, 2016). The specific characteristics of sustainability initiatives depend on the time horizon over which their impacts are realized, their transformative potential and their degree of strategic alignment.

In the theoretical framework that guided this study, neo-institutional theory informs about the generic external pressures that drive organizations to invest in sustainability initiatives. The organizational responses to increasing pressures are captured in the balancing feedback B1 (pressure for change), as shown in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 1. Starting with the variable “pressure for organizational commitment with sustainability,” Figure 1 illustrates that, as the pressure for change increases, the organization ideally aligns its purpose, vision and mission more closely with sustainability principles. This drives the establishment of sustainability goals and policies which, in turn, lead to the implementation of sustainability initiatives. The real impact of such initiatives depends on the nature of the sustainability initiatives themselves: the higher the complexity and alignment with strategic goals, the greater their impact. Importantly, while more substantial initiatives are more complex and lead to higher impact, their outcomes take longer to be manifested. In contrast, the symbolic initiatives provide quick wins, but are usually less impactful. This is represented in Figure 1 as a delay (||) between the variables “sustainability initiatives” and “real impact of sustainability initiatives,” and by the variable “transformative potential.” As the impact of sustainability initiatives manifests, the performance gap begins to narrow. In turn, this gradually decreases the pressure for organizational commitment to sustainability, bringing the system to a state of reduced pressure. Ultimately, based on insights from neo-institutional theory, this process demonstrates how organizations respond to pressures and alleviate demands through the implementation of sustainability actions.

1.1.3 Employees' perceptions shape and are shaped by sustainability initiatives

Regardless of the degree of alignment with strategic goals, the successful implementation of sustainability initiatives relies on the active support of individual employees (Süßbauer et al., 2019). Employees—even those whose roles are not explicitly linked to sustainability topics—are increasingly recognized as key internal stakeholders for sustainability implementation, since they can act as implementers, ambassadors or recipients of corporate sustainability practices (Süßbauer et al., 2019). However, the way employees respond to sustainability initiatives depends not only on the practices themselves, but on how employees perceive and interpret them, including the motives attributed to their implementation (Aguinis et al., 2024; Akremi et al., 2018; Vlachos et al., 2017). To express these dynamics, we draw on sensemaking and attribution theories, since both provide interconnected insights and highlight the importance of perception and interpretation in shaping behaviors and decisions (Babu et al., 2020; Kelley and Michela, 1980; Weick, 1995).

Due to the intrinsic complexity and unavoidable tradeoffs associated with sustainability-related topics, sustainability initiatives often trigger sensemaking processes (Aguinis and Glavas, 2019; Hahn et al., 2010; Babu et al., 2020). According to sensemaking theory, when individuals are confronted with complex or ambiguous situations, they engage in sensemaking to understand such events and decrease uncertainty (Weick, 1995). This process happens collectively and individually, in an iterative and retroactive fashion, when employees actively interpret cues from their environment and draw on their previous experiences, social interactions and organizational context to create a coherent comprehension of what happened (Glavas, 2016; Weick, 1995). Informed by such sensemaking process and its consequent narratives, individuals make attributions about the motives behind organizational policies and practices, distinguishing between genuine (i.e., substantial, internally motivated, cause-serving) and self-serving (i.e., symbolic, externally motivated, self-serving) motives (Babu et al., 2020; Kelley and Michela, 1980).

The resulting attributions, narratives and perceptions (hereafter referred to as perceptions) influence employees' attitudes, which refer to negative or positive emotions and beliefs triggered by sustainability initiatives. In turn, the resulting employees' perceptions and attitudes lead to specific behaviors toward sustainability initiatives, including engagement, participation and proactivity (Aguinis et al., 2024). For instance, a time-lagged empirical study demonstrated that positive outcomes for employees occur only when they perceive CSR actions in their organizations as being driven by genuine motives (Donia et al., 2019). Importantly, a myriad of external and individual factors, along with information provided by the organizational context (such as its purpose, vision and mission), influence employees' perceptions of sustainability initiatives. This explains why, inside the same company, employees display varying opinions about such initiatives, which may change over time as new information becomes available or the context changes (Aguinis and Glavas, 2019; Gond et al., 2017).

In summary, employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviors shape and are shaped by sustainability efforts that take place in their work environment (Aguinis et al., 2024). This interplay between organizational factors and employees' responses is depicted in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 1. Beginning with the variable “real impact of sustainability practices,” the reinforcing feedback loop R1 (shaping sustainability implementation) demonstrates how the real impact of sustainability practices influences employees' perceptions and attitudes toward such practices, thereby shaping their behavior and ultimately impacting the implementation of future sustainability initiatives. Specifically, when the impact of sustainability initiatives is positively perceived, employees' attitudes and behaviors become more supportive, fostering a virtuous cycle that encourages further implementation of sustainability initiatives. Oppositely, negative perceptions lead to attitudes and behaviors that hinder sustainability implementation, creating a vicious cycle that reduces impact and increases pressure for change. Therefore, the feedback loop R1 (shaping sustainability implementation) depicts the self-amplifying role of employees in shaping the success or failure of an organizations' sustainability journey.

2 Methods

This research builds on observations from an in-depth single case study conducted by some of the authors of this paper (CBV, KH, YVM). Designed according to best practices available in literature (Yin, 2018), this case study primarily explored barriers to the implementation of sustainability-oriented projects within a multinational corporation (MNC) involved in the life sciences industry, focusing on the perspectives of employees from enabling functions. Detailed information about the company, sample and context are available in Supplementary material, Section S1, and in Bettker Vasconcelos et al. (2025). The methods employed in this study are presented in the following subsections.

2.1 Primary data collection and description

The collection of primary data involved a multimethod qualitative approach, including semi-structured interviews alongside a qualitative survey (QS) (Das et al., 2022; Mik-Meyer, 2020). This strategy facilitates the exploration of a specific phenomenon from multiple perspectives, minimizing the risk of over-representing the views of a few participants. It also allows researchers to confront and complement the findings from semi-structured interviews. The initial data collection phase, which included semi-structured interviews and a qualitative survey, took place from October to December 2022. Additional semi-structured interviews were conducted between August 2023 and November 2024 to validate and expand findings. This approach enabled the researchers to confirm, expand, and evaluate the temporal consistency of their preliminary findings. The semi-structured interview plans and QS details are available in Supplementary material, Section 1.

The empirical dataset comprised 50 data points, including 9 exploratory semi-structured interviews, 33 valid survey responses and 8 validation interviews. The sample was diverse regarding the participants' roles within the company, their areas of expertise, and years of experience within the organization. Detailed information regarding participants' details is available in Supplementary Table S1. To ensure anonymity, participants' current positions were not revealed. This rich empirical dataset has also supported the development of a separate study (Bettker Vasconcelos et al., 2025). Importantly, research questions, theoretical lenses, and methodologies of these studies are entirely distinct, thereby ensuring the originality and unique contribution of their findings. Additionally, while both studies share part of the empirical dataset, this study also builds on secondary data, as described in the following subsection.

2.2 Secondary data collection and description

A systematic literature review was conducted to validate and complement the primary data. Secondary data was obtained based on the following search string on Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY (employee* AND perception OR attribution OR sensemaking OR meaning OR interpretation AND “corporate sustainability” OR “corporate social responsibility” OR “csr” OR “esg” OR “environmental performance” OR “sustainability initiatives” AND symbolic OR substantial OR genuine OR self-serving OR intrinsic OR extrinsic OR greenwashing). The initial search generated a total of 70 results. The exclusion criteria eliminated studies focused on stakeholders other than employees, specific sectors (hotels, public sector and educational institutions), external communication (e.g., reporting), green HR practices, non-empirical research, and those not examining employee perceptions or interpretations of sustainability initiatives. After applying exclusion criteria and reviewing titles, keywords, and abstracts, 37 papers were selected. Additional papers were included through snowball sampling, resulting in a total of 46 studies. An overview of the selected papers is available in Supplementary material, Section 2.1.

2.3 Data analysis

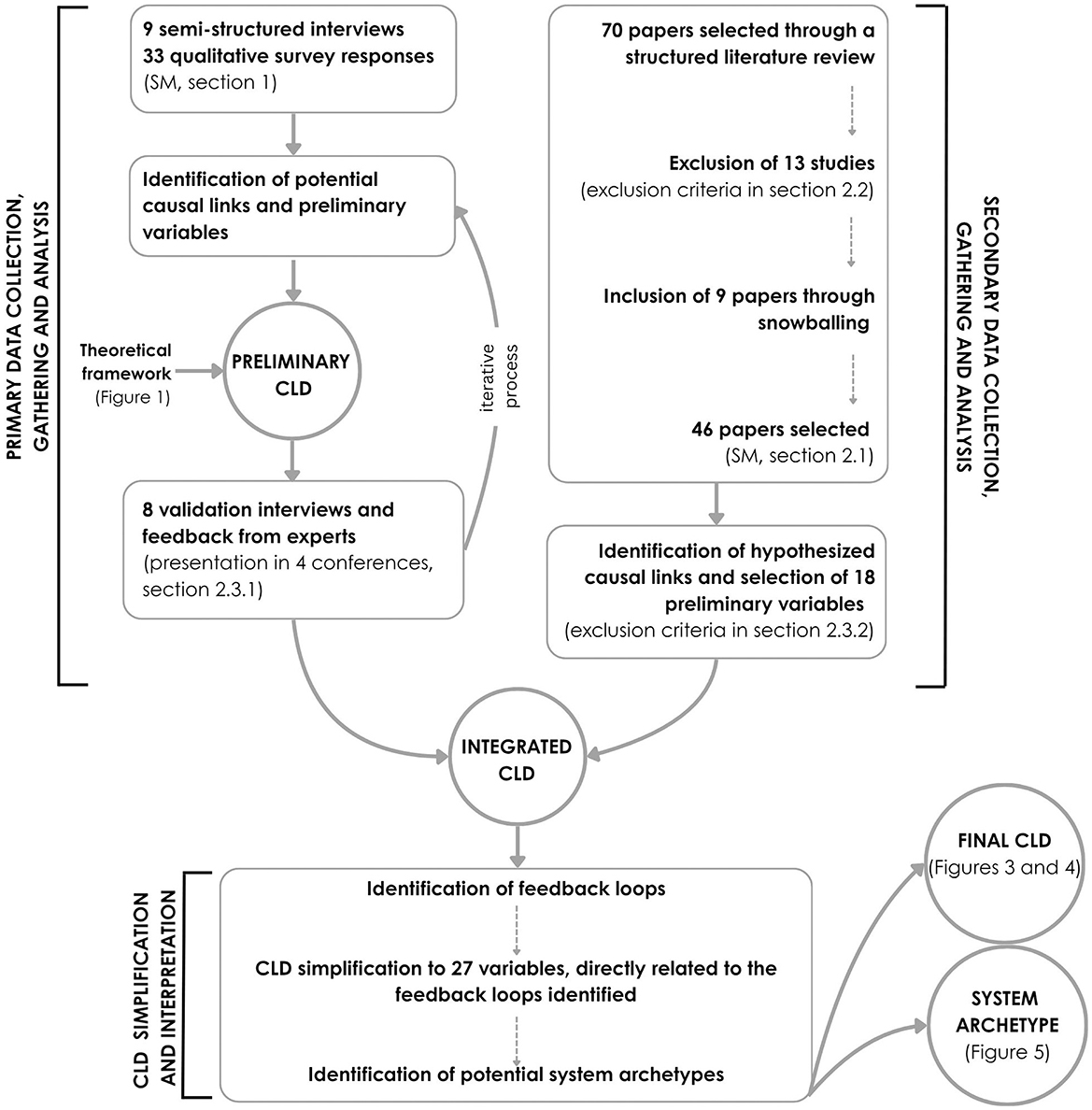

This section describes the gathering and analysis of both primary and secondary data. Figure 2 illustrates the main steps of this process.

Figure 2. Diagram representing iterative data analysis and validation process. CLD, Causal loop diagram; SM, Supplementary material.

2.3.1 Primary data

Data gathering, analysis and validation were performed iteratively, as demonstrated in Figure 2. First, primary data obtained through semi-structured interviews and QS responses was analyzed through an inductive approach inspired by Kim and Andersen (2012). Each participants' sentences that suggested causal relationships were inductively coded in the software MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2021). Based on the coded textual data, variables representing hypothetical causes and effects were identified, and the polarity of such relationships was also documented. Then, the identified causal links were added to the theoretical framework of this study (Figure 1). This process was performed using the software Vensim® PLE 10.2.1. The resulting Preliminary CLD was refined and iteratively validated throughout 8 validation interviews, as mentioned in Section 2.1. Additionally, such preliminary versions were presented in four distinct scientific events, namely: International Conference on New Business Models (July 2024, Donostia/San Sebastian, Spain); International System Dynamics Conference 2024 (August 2024, Bergen, Norway); 4th Maastricht Observatory on Responsible, Resilient and Sustainable Societies, Economies and Enterprises (MORSE) Academic Conference 2024 (October 2024, Maastricht, Netherlands); 3rd Learning and Innovation for Resilience and Sustainability Symposium (November 2024, Heerlen, Netherlands). Feedback from experts across various disciplines contributed to the validation and the conceptual significance of this study, while experts in SD provided substantial methodological support.

2.3.2 Secondary data

While iteratively refining and validating the preliminary versions of the CLD, the analysis of the 46 selected scientific papers was conducted, with a focus on identifying variables and their relationships. To ensure representativeness and avoid redundancy in literature-derived data, only variables supported by at least two distinct references or associated with at least three other variables were selected for the following data analysis step. In addition, variables expressing similar concepts were merged into a single variable. This process led to the selection of 18 variables and their hypothetical relationships, which were subsequently integrated into the validated version of the Preliminary CLD. This process not only expanded the results of this research but also provided additional validation for some empirically identified causal links, leading to the generation of an Integrated CLD, as mentioned in Figure 2. At this stage, each causal link was associated with its respective source reference, following recommendations available in the literature (Jalali and Beaulieu, 2024).

2.3.3 CLD simplification and interpretation

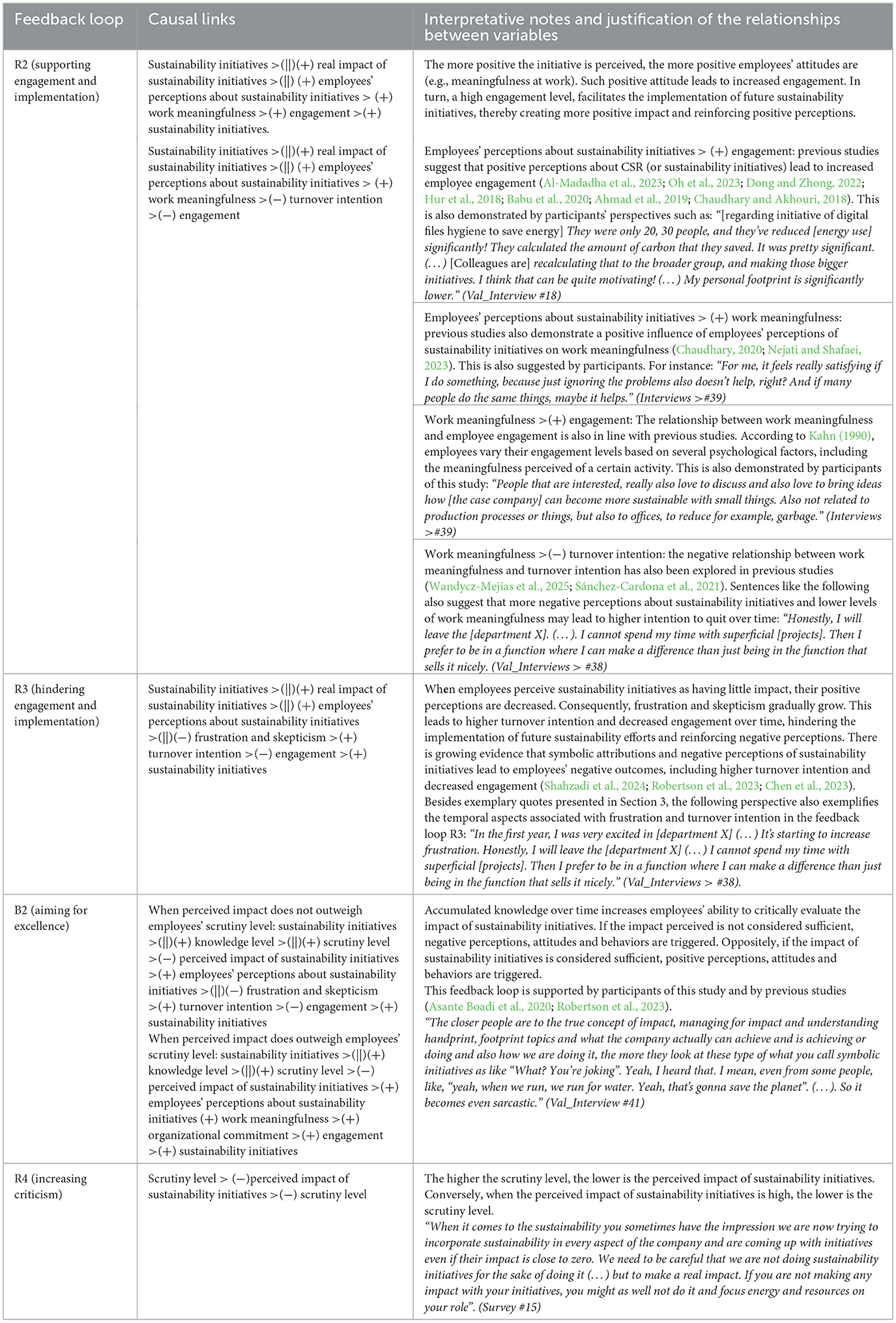

The Integrated CLD was analyzed with the aid of the software Vensim® PLE 10.2.1, and feedback loops were identified. Each feedback loop was analyzed using an approach inspired by Tomoaia-Cotisel et al. (2021). During this process, the researchers gathered supporting quotes and previous studies that assisted the comprehension of each feedback loop identified, while also indicating relevant temporal aspects. The researchers' reasoning and interpretation were systematically documented to increase the credibility and reproducibility of causal links and feedback loops, thus ensuring a transparent interpretative process. Following the identification and interpretation of feedback loops, variables not associated with these loops were removed from the final diagram to facilitate readability and focus on the main dynamics of the phenomenon under investigation. This process generated the final CLD presented in this study (Figures 3, 4), which was assessed for the identification of system archetypes, i.e., recurring structures responsible for patterns of behavior over time, especially counterintuitive behaviors (Kim, 2000; Wolstenholme, 2003).

Figure 3. Sustainability initiatives shape and are shaped by employees' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors, generating feedback loops that either support (R2) or hinder (R3) further sustainability implementation. The link polarity indicates how two variables change in relation to each other. Orange arrows highlight negative polarity. Gray text and arrows refer to the theoretical framework of this study. Double lines perpendicular to the arrows (||) indicate a substantial time delay in that causal relationship.

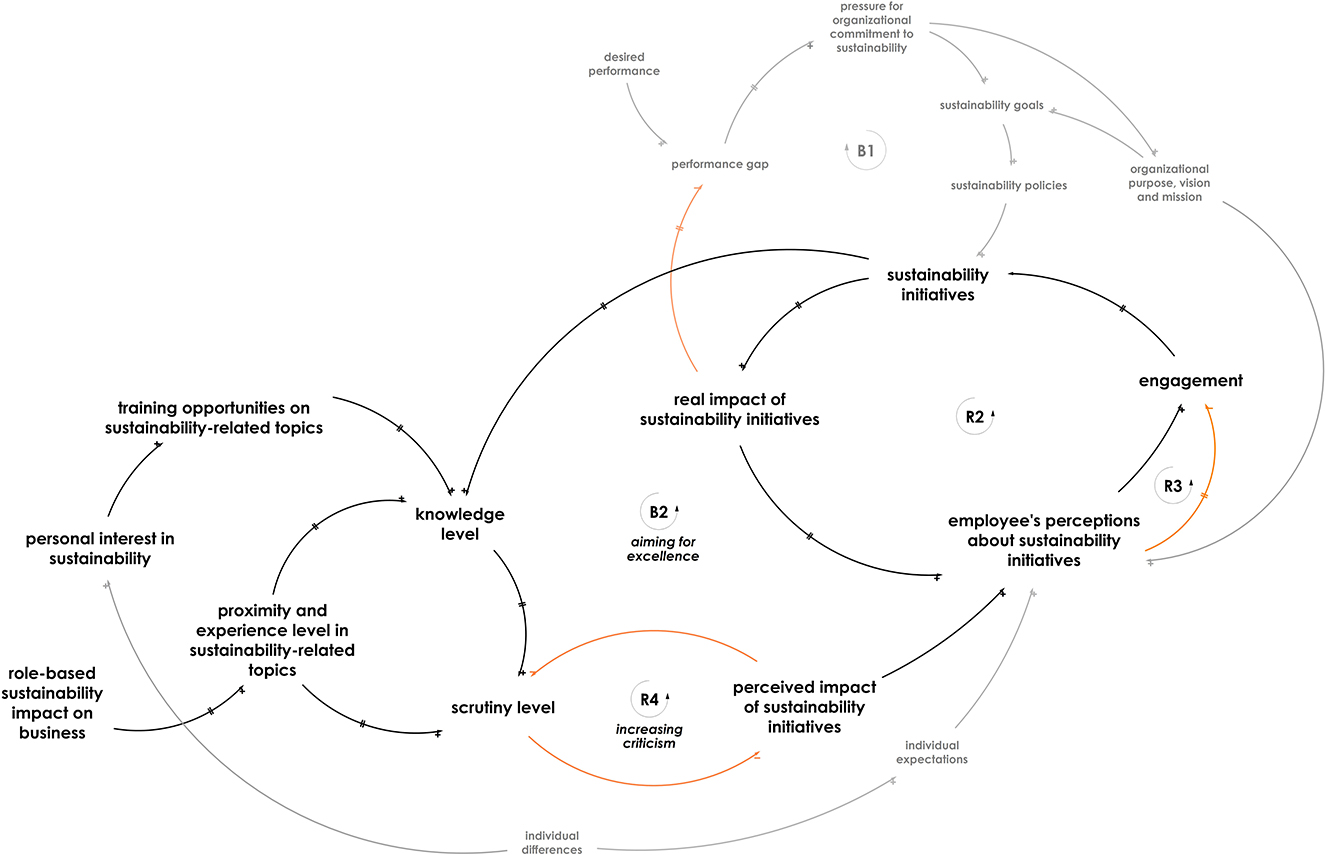

Figure 4. Deeper knowledge in sustainability-related topics increases scrutiny and leads to more critical perceptions of sustainability efforts (feedback loops B2 and R4). The link polarity indicates how two variables change in relation to each other. Orange arrows highlight negative polarity. Gray text and arrows refer to the theoretical framework of this study. Double lines perpendicular to the arrows (||) indicate a substantial time delay in that causal relationship.

3 Results

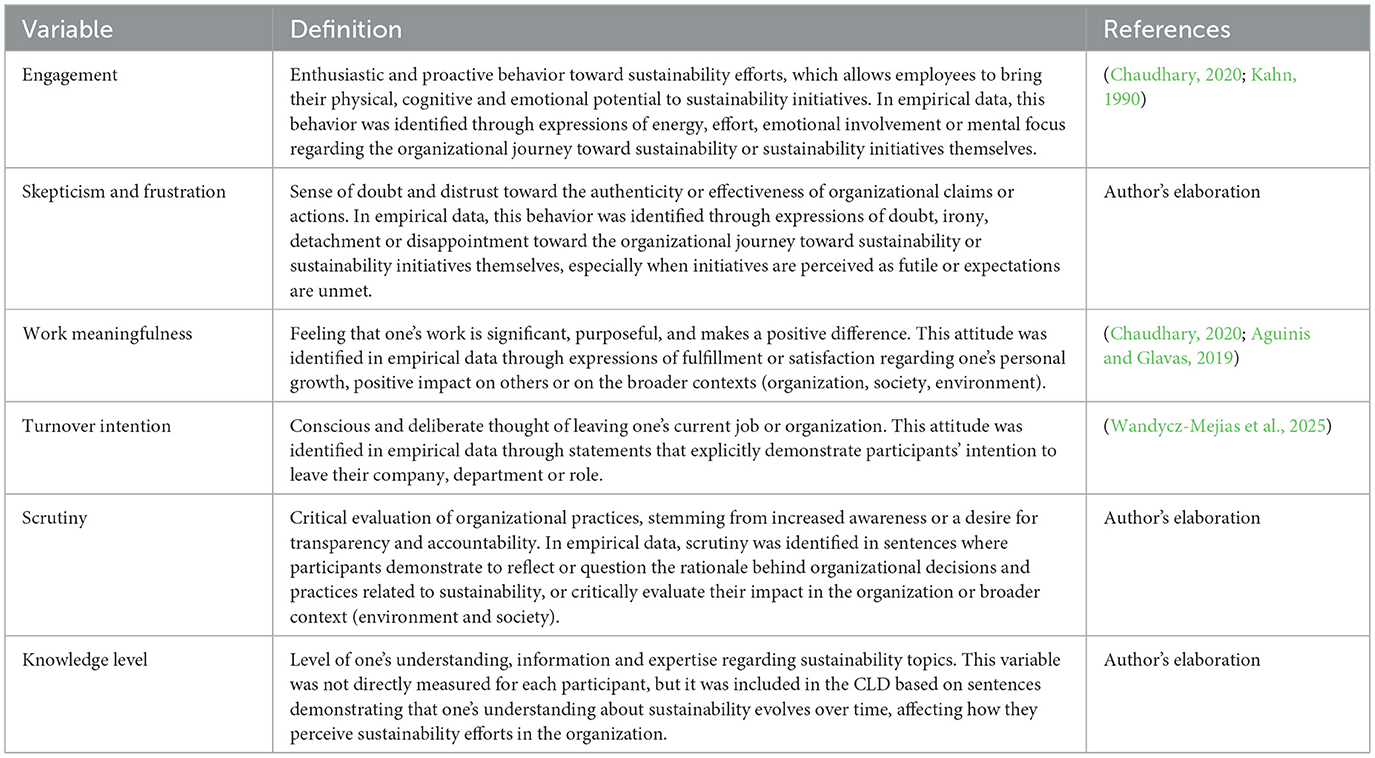

This section presents the main findings of this study, which result from the integration of insights obtained through semi-structured interviews, QS and systematic literature review into the theoretical framework of this study (Section 1.1, Figure 1). Table 2 lists key variables presented in Figures 3, 4. A detailed description of each variable presented in this paper is available in Supplementary material, Section 3, Supplementary Table S2. Additionally, a summary of each feedback loop is provided in Table 3, containing exemplary quotes and supporting studies.

The analysis of the CLD, derived from the integration of empirical data and prior research findings, reveals the existence of two main reinforcing feedback loops. As depicted in Figure 3, the feedback loop R2 (supporting engagement and implementation) shows that when employees display more positive perceptions about sustainability initiatives their sense of work meaningfulness and engagement increase. This, in turn, increases the implementation of future sustainability practices within the organization and increasing their chances of success. Oppositely, the reinforcing feedback loop R3 (hindering initiatives through negative perceptions) shows that negative perceptions about sustainability initiatives potentially reduce sustainability implementation. The findings indicate that there is an increase in frustration and skepticism when employees perceive sustainability practices more negatively (i.e., initiatives are perceived as symbolic, hypocritical, or having low impact). According to empirical data, this process occurs gradually, as indicated by a delay sign between the variables “employees' perceptions about sustainability initiatives” and “frustration and skepticism” (Figure 3). The data also show, these negative attitudes lead to higher turnover intention and lower employee engagement. Decreased employee engagement, in turn, reduces the implementation of sustainability practices, reinforcing negative perceptions and completing the reinforcing loop. The perspective of a participant illustrates this dynamic:

“Lack of focus on topics where they can create significant and sustained impact, in line with company priorities, tends to proliferate actions, reduce impact and hence create frustration and hinder longer term employee engagement.” (Survey #6)

The analysis of the resulting CLD also reveals variables that influence the dynamics of feedback loops R2 (supporting engagement and implementation) and R3 (hindering initiatives through negative perceptions), such as knowledge level regarding sustainability. The data show that, over time, employees increase their expertise about sustainability through training opportunities, direct engagement with sustainability initiatives or role-related involvement. This increase in knowledge and experience levels lead to higher scrutiny of sustainability initiatives, thereby reducing the perceived impact of these initiatives. As a result of the diminishing levels of perceived impact, employees' perceptions gradually become more negative. Therefore, unless employees perceive the impacts of sustainability initiatives as significant or satisfactory, negative perceptions will rise, fostering negative attitudes and behaviors associated with feedback loop R3 (hindering initiatives through negative perceptions) in a reinforcing manner. This overall dynamic is represented in Figure 4, specifically in the balancing loop B2 (aiming for excellence) and R4 (increasing criticism) (Table 3). The viewpoint of a participant in this study illustrates this finding:

“When it comes to sustainability, you sometimes have the impression we are now trying to incorporate sustainability in every aspect of the company and are coming up with initiatives even if their impact is close to zero. We need to be careful that we are not doing sustainability initiatives for the sake of doing it (….). If you are not making any impact with your initiatives, you might not do it and focus energy and resources on your role.” (Survey > #15)

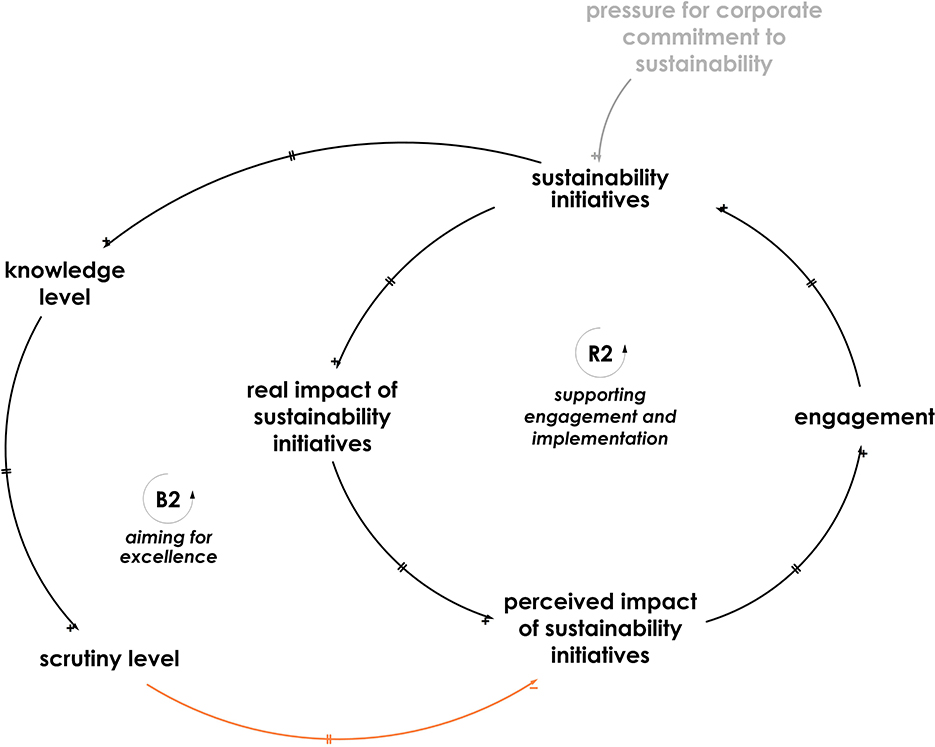

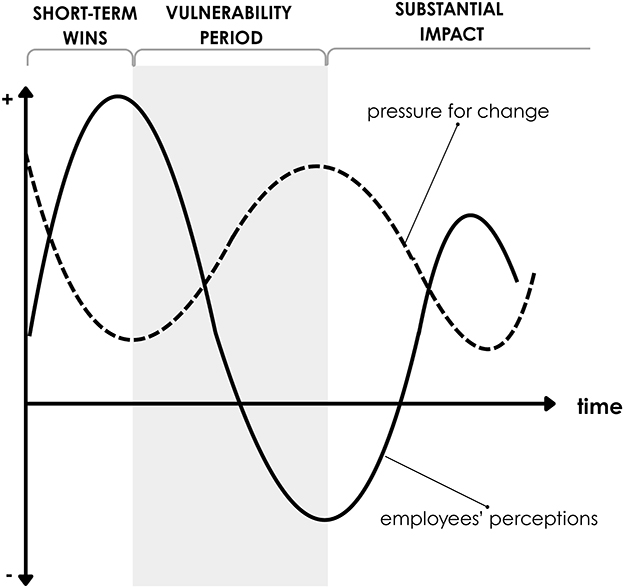

To summarize these dynamics, Figure 5 depicts the interaction pattern between the feedback loops B2 (aiming for excellence) and R2 (supporting engagement and implementation). It shows that the implementation of sustainability initiatives increases employees' engagement (short-term effect), while simultaneously increasing employees' knowledge and experience in sustainability topics. However, higher knowledge and experience levels increase scrutiny regarding the impact of sustainability initiatives, which can unintentionally decrease employees' engagement when the impact of sustainability initiatives is not considered satisfactory (long-term effect).

Figure 5. Fixes that fail: Although more symbolic sustainability initiatives initially boost employee engagement (R2), increasing knowledge and skepticism (B2) can unintentionally decrease engagement if the perceived impact of these initiatives does not outweigh the growing scrutiny. Orange arrows highlight negative polarity.

4 Discussion

Based on the interdisciplinary and integrative perspective of systems thinking, this study relies on the development of CLDs to explore the complex and dynamic relationships between sustainability initiatives and employees' perceptions, attitudes and behavior. To develop the theoretical framework of this study, a CLD was developed to integrate insights from neo-institutional theory, attribution theory and micro-CSR research. The theoretical framework, illustrated in Figure 1, provided a dynamic perspective into the topic and depicted the interplay between external pressures, organizational responses and individual reactions. To address the research question of this study, insights obtained from semi-structured interviews, QS responses, and prior studies were integrated into the theoretical framework (Figure 1), generating the CLD depicted in Figures 3, 4.

The results presented in Figures 3, 4 reveal complex interconnections among the variables and feedback loops associated with employees' responses to sustainability efforts in the workplace (Table 3). The feedback loop R2 (supporting engagement and implementation) represents the virtuous cycle of continued support for sustainability implementation, where employees with positive perceptions about sustainability initiatives support continuous sustainability implementation within the organization, potentially generating more impact and positive perceptions (Figure 3). Oppositely, R3 (hindering initiatives through negative perceptions) demonstrates a vicious cycle of continuous negative perceptions and decreased engagement in sustainability implementation (Figure 3). Additionally, in Figure 4, the feedback loop B2 (aiming for excellence) illustrates how the gradual accumulation of key variables, such as knowledge and experience levels, influences the dynamic interactions between feedback loops R2, R3, and B1.

The interdependencies among these feedback structures, as shown in Figures 3, 4, suggest the existence of a coupled feedback system, where the loops are structurally connected through shared variables, mutually influencing their activation and dominance patterns. Therefore, the system behavior over time depends on which of the feedback loops is more dominant (Richardson, 1995; Sterman, 2000). When examining these findings through the integrated perspective of neo-institutional, sensemaking and attribution theories, it can be suggested that the feedback loop R2 (supporting engagement and implementation) is dominant in the early stages of an organization or individual's sustainability journey. According to neo-institutional theory, more symbolic sustainability initiatives are typically simpler to execute and manifest their effects quickly, allowing companies to manage their legitimacy at short term (Di Maggio and Powell, 1983; Schons and Steinmeier, 2016). At this stage, the implementation of simpler sustainability initiatives, along with limited employee expertise, creates a straightforward environment, in which fewer contradictions and trade-offs are noticed. This can create a temporary sense of achievement among employees, especially those whose roles offer limited involvement with sustainability practices (Sancak, 2023; Stouten et al., 2018). In this context, more uncritical narratives about sustainability initiatives are generated, providing a favorable context for individual attribution processes (e.g., employees are more likely to attribute genuine motives to sustainability initiatives) (Babu et al., 2020). This leads to more positive perceptions, increasing employee engagement, and enhancing their support toward additional sustainability initiatives.

However, the findings suggest that this initial positive momentum is fragile and can transition into a “vulnerability period” (Figure 6). The “vulnerability period” represents a challenging phase, when initial enthusiasm and engagement may decrease while pressure for change increases., In other words, it can be suggested that the dominance of the feedback loop R2 (supporting engagement and implementation) decreases, while there is an increase in the dominance of B1 (pressure for change) (Figure 6). According to this study's findings, the gradual accumulation of employees' knowledge and experience in sustainability efforts is crucial in triggering a transition toward the “vulnerability period.” The “vulnerability period” marks a phase where employees gradually become aware of the potential disconnect between their organization's policies or ceremonial actions (“talk”) and the daily practices that promote substantial progress toward sustainability (“walk”) (Schons and Steinmeier, 2016). As shown in the balancing feedback loop B2 (aiming for excellence) (Figures 4, 5), as employees gradually accumulate knowledge and experience in sustainability-related areas, they tend to perceive the impact of sustainability initiatives with greater scrutiny, being able to identify potential inconsistencies and shortcomings. If there is a perception of disconnection, or if the impacts of more substantial sustainability changes are not yet apparent, employees may engage in collective sensemaking processes to make sense of such a discrepancy. This heightened scrutiny potentially increases ceremonial or external attributions toward sustainability efforts (Lauriano et al., 2022; Babu et al., 2020). Consequently, negative perceptions arise, gradually increasing the dominance of the feedback loop R3 (hindering initiatives through negative perceptions) and leading to a decline in employee engagement. Ultimately, this decline in engagement hinders the overall implementation of sustainability initiatives and reinforces the pressure for organizational commitment with sustainability (B1, pressure for change), as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Potential dynamic behavior over time. The shaded gray background represents the “vulnerability” period, a critical phase where employees' perceptions, attitudes and behavior regarding sustainability initiatives are prone to shifting toward more negative states. This is a conceptual figure.

This dynamic can also be comprehended through the system archetype “Fixes that Fail” (Figure 5), which illustrates that while certain solutions may be effective in the short term, they can lead to unintended long-term consequences (Senge, 2006; Kim, 2000). In this scenario, the long-term negative effects of more symbolic sustainability initiatives can exacerbate pressure for organizational commitment to sustainability. The outcome of this period can influence the sustainability implementation trajectory, leading to either significant improvements in the quality and impact of sustainability initiatives or cycles of diminishing returns and increasing scrutiny (Wolstenholme, 2003).

Interestingly, the “vulnerability period” can also reflect the complexity of implementing more substantial sustainability initiatives. As organizations transition from simpler and short-term solutions to more substantial sustainability changes, employees confront the inherent difficulties associated with the implementation of substantial sustainability changes. This critical period has been acknowledged in the change management literature. Since a sustainability transformation in organizations is a long-term process, previous studies claim that focusing on short-term wins is fundamental for obtaining employees' initial support (Sancak, 2023; Kotter, 2007). However, it is easy to get stuck in this initial stage, since the relative ease and low cost of more symbolic efforts may be prioritized over deeper and more complex ones (Riemer et al., 2025). Consequently, overreliance on short-term wins can lead to misunderstandings that undermine change initiatives (Stouten et al., 2018). Therefore, as the severity and length of this period are context-dependent, it is critical to raise awareness about the differences between short-term wins and long-term expectations to avoid getting trapped into a “Fixes that Fail” dynamics (Sancak, 2023; Senge, 2006). Clear and transparent internal communication is key for maintaining engagement, readjusting trust and aligning expectations among employees (Robertson et al., 2023).

Overall, the findings of this study align with previous research that demonstrates the importance of perceived impact and authenticity of sustainability-focused actions in shaping employees' attitudes and behaviors (Donia et al., 2017). For instance, this study's results resonate with previous work demonstrating that genuine, substantial attributions of CSR are associated with employee engagement, whereas ceremonial attributions trigger negative outcomes, such as cynicism (Shahzadi et al., 2024). However, this research expands on this understanding by suggesting that employees' perceptions may gradually change over time. In this study, the findings indicate that such changes result from the accumulation of knowledge, experience, and subsequent heightened scrutiny levels. This demonstrates the importance of considering temporal aspects, individual and contextual changes when investigating employees' responses to sustainability initiatives.

Additionally, the findings also contribute to the literature by challenging the traditional dichotomy between the positive and negative effects of sustainability initiatives on employees. Instead, this study uncovers a more nuanced interplay between individual processes and organizational factors in shaping progressive (dis)engagement in sustainability. This finding is in line with Hejjas et al. (2019), who suggest employee engagement in CSR as a spectrum rather than a binary state. Similar to their findings, this research acknowledges the individual differences among employees, highlighting that, in certain contexts or at early stages, initiatives perceived as “symbolic” or “ceremonial” by some employees may still generate positive outcomes for others, especially those who are still developing their understanding of sustainability topics or cannot directly work in sustainability through their formal roles. Importantly, this study also highlights the importance of knowledge and experience accumulation in changing employees' perceptions about sustainability initiatives. This finding corroborates previous results of Robertson et al. (2023), who demonstrated the important role of environmental education in mediating turnover intentions resulting from perceived greenwashing. Finally, this study's methodological approach is novel. By integrating insights from neo-institutional, sensemaking and attribution theories into CLDs, this study provides a multilevel perspective on the dynamics of sustainability implementation, therefore providing the foundation for future interdisciplinary and integrative research.

This study also has valuable implications for practitioners, since its findings depict the complexity of implementing sustainability initiatives in organizational contexts while managing stakeholders' expectations and responses. First, practitioners must acknowledge the dual nature of short-term wins, or symbolic sustainability initiatives. This study's findings reveal that while such efforts might be relevant to employees who are not formally involved in sustainability topics through their roles, they potentially hinder the engagement of more critical and more experienced employees. Therefore, consistent, impactful and authentic efforts are necessary to maintain employees' engagement and support in the longer term (Sancak, 2023). Additionally, understanding the dynamic nature of employees' perceptions is key to effective sustainability implementation. The shift in engagement during the “vulnerability period” is a critical phase for management. To navigate this phase, transparent and consistent communication is crucial for realigning expectations and reinforcing trust (Robertson et al., 2023; Sancak, 2023). Finally, the findings of this study also suggest that employees' vigilance and scrutiny are not only a challenge for sustainability implementation, but also an asset to the organization. Creating formal channels for feedback and participation can assist managers in better understanding employees' perspectives. This can serve as valuable input for continuous improvement, and potentially encouraging more plural perspectives about corporate sustainability in organizations (Hahn and Aragón-Correa, 2015).

5 Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the complex dynamics between sustainability initiatives and employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviors in organizational settings. By applying systems thinking lenses and tools, this research reveals a critical “Fixes that Fail” archetype that can undermine sustainability changes in organizational settings. The findings demonstrate that while simple sustainability initiatives, or short-term wins can boost employee engagement and support for future sustainability implementation, this initial enthusiasm can turn into frustration and skepticism as employees become more knowledgeable and critical over time. This creates a “vulnerability period,” where maintaining employees' engagement and support becomes challenging if the perceived impact of sustainability initiatives does not consistently outweigh their growing scrutiny. These dynamics demonstrate that employees' vigilance is a powerful force for pushing an organization toward excellence in its sustainability efforts.

Additionally, this study's findings also provide a more nuanced perspective on more symbolic sustainability initiatives. Results suggest that these symbolic initiatives are not inherently bad. At early stages, initiatives perceived as “symbolic” or “ceremonial” by some employees may still generate positive outcomes for others, especially those seeking meaningful work and engagement in sustainability, but who cannot achieve this directly through their roles. However, to sustain long-term engagement and avoid falling into the “Fixes that Fail” archetype, organizations must deliver consistent, impactful and authentic efforts whose perceived impact withstand increasing employees' scrutiny. Ultimately, if companies fail to deliver substantial sustainability impact, which is in line with their long-term sustainability strategy and goals, initial employee engagement may give way to skepticism and disengagement. This could not only hinder specific sustainability initiatives but also undermine employee trust in the company's commitment to sustainability, potentially leading to systemic failure in achieving broader sustainability objectives. Therefore, this study also corroborates the importance of companies “walking” their “talk.” In summary, it contributes to academia and practice by demonstrating possibly unexpected consequences of sustainability initiatives, challenging traditional dichotomies and providing a more nuanced understanding of progressive employee (dis)engagement. It also addresses literature gaps by adopting a multi-level and integrative systems perspective, taking into account temporal aspects, interconnections and feedback loops.

This research also has limitations, mainly regarding the generalizability of the findings and methodological constraints. While the sample of 42 participants and previous 46 studies is adequate for qualitative analysis, the results obtained cannot be generalized to organizations, regardless of their size and sector. Additionally, the exclusion criteria applied for the selection of secondary data has left important variables out of the CLD presented in Figure 4. Moreover, the CLDs presented in this study did not account for the external context in which the case organization or individuals are situated. Such simplification limits the interpretation of this study's findings. Finally, given the diverse definitions of sustainability initiatives and CSR, participants might have interpreted such terms differently.

Despite these limitations, this study offers prospects for future interdisciplinary research. Future studies could build on the CLD presented in Figure 4 and integrate other theoretical perspectives, additional empirical data and macro-level variables. Analyzing how variables at macro level influence employees' perceptions could substantially expand the current academic understanding of the topic. Additionally, future research could explore how the implementation approach (top-down or bottom-up) influences employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviors. Finally, researchers are invited to formulate and test simulation models based on the dynamic hypothesis (CLDs) presented in this paper (Sterman, 2000). This would allow for a more rigorous and predictive analysis of feedback loops dominance and behavior over time.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Maastricht University Data Protection Officer (DPO). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS-Z: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Marie Skolodowska-Curie grant agreement ID: 956621.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the participants who generously allocated their time to this research and shared their insights. We also thank all experts who provided feedback and assistance during the research design phase, data analysis and interpretation of results, especially Dr. Daniel Guzzo and those engaged with the Systems Dynamics Society.

Conflict of interest

KH was employed by Henning4future.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1666622/full#supplementary-material

References

Aguinis, H., and Glavas, A. (2019). On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 45, 1057–1086. doi: 10.1177/0149206317691575

Aguinis, H., Rupp, D. E., and Glavas, A. (2024). Corporate social responsibility and individual behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 219–227. doi: 10.1038/s41562-023-01802-7

Ahmad, I., Donia, M. B. L., and Shahzad, K. (2019). Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employees' creative performance: the mediating role of psychological safety. Ethics Behav. 29, 490–509. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2018.1501566

Akhouri, A., and Chaudhary, R. (2019). Employee perspective on CSR: a review of the literature and research agenda. J. Glob. Responsib. 10, 355–381. doi: 10.1108/JGR-11-2018-0057

Akremi, A. E., De Roeck, K., and Igalens, J. (2018). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Dev. Valid. Multidimens. Corp. Stakeholder Responsib. Scale 44, 619–657. doi: 10.1177/0149206315569311

Al-Madadha, A., Shaheen, F., Alma'ani, L., Alsayyed, N., and Adwan, A. A. L. (2023). Corporate social responsibility and creative performance: the effect of job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior. Organizacija 56, 32–50. doi: 10.2478/orga-2023-0003

Asante Boadi, E., He, Z., Bosompem, J., Opata, C. N., and Boadi, E. K. (2020). Employees' perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its effects on internal outcomes. Serv. Indus. J. 40, 611–632. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2019.1606906

Ashforth, B. E., and Gibbs, B. W. (1990). The double-edge of organizational legitimation. Organiz. Sci. 1, 177–194. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1.2.177

Babu, N., De Roeck, K., and Raineri, N. (2020). hypocritical organizations: implications for employee social responsibility. J. Business Res. 114, 376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.034

Bansal, T., and Birkinshaw, J. (2025). Why You Need Systems Thinking Now. Harvard Business Review. Available online at: https://hbr.org/2025/09/why-you-need-systems-thinking-now (Accessed August 14, 2025).

Bettker Vasconcelos, C., Henning, K., and van der Meer, Y. (2025). Unlocking sustainability impact: a systems thinking approach to identifying intraorganizational barriers. Clean. Prod. Lett. 9:100105. doi: 10.1016/j.clpl.2025.100105

Bhuiyan, F., Adu, D. A., Ullah, H., and Islam, N. (2025). Employee organisational commitment and corporate environmental sustainability practices: mediating role of organisation innovation culture. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 34, 4485–4506. doi: 10.1002/bse.4200

Bromley, P., and Powell, W. W. (2012). Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 6, 483–530. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2012.684462

Chaudhary, R. (2020). Authentic leadership and meaningfulness at work: role of employees' csr perceptions and evaluations. Manag. Decis. 59, 2024–2039. doi: 10.1108/MD-02-2019-0271

Chaudhary, R., and Akhouri, A. (2018). Linking corporate social responsibility attributions and creativity: modeling work engagement as a mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 190, 809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.187

Chen, X., Hansen, E., Cai, J., and Xiao, J. (2023). The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attribution on job satisfaction and turnover intention. Business Ethics Environ. Respons. 32, 1233–1246. doi: 10.1111/beer.12572

Das, A., Konietzko, J., and Bocken, N. (2022). How do companies measure and forecast environmental impacts when experimenting with circular business models? Sust. Prod. Consumpt. 29, 273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.10.009

De Roeck, K., and Maon, F. (2018). Building the theoretical puzzle of employees' reactions to corporate social responsibility: an integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Business Ethics 149, 609–625. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3081-2

Di Maggio, P. J., and Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 48, 147–160. doi: 10.2307/2095101

Dong, W., and Zhong, L. (2022). How and when responsible leadership facilitates work engagement: a moderated mediation model. J. Manag. Psychol. 37, 545–558. doi: 10.1108/JMP-06-2021-0366

Donia, M. B. L., Ronen, S., Sirsly, C.-A. T., and Bonaccio, S. (2019). CSR by any other name? The differential impact of substantive and symbolic CSR attributions on employee outcomes. J. Business Ethics 157, 503–523. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3673-5

Donia, M. B. L., Sirsly, C. A. T., and Ronen, S. (2017). Employee attributions of corporate social responsibility as substantive or symbolic: validation of a measure. Appl. Psychol. 66, 103–142. doi: 10.1111/apps.12081

Glavas, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: an integrative review. Front. Psychol. 7:144. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00144

Glavas, A., and Kelley, K. (2014). The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Business Ethics Quart. 24, 165–202. doi: 10.5840/beq20143206

Gond, J. P., El Akremi, A., Swaen, V., and Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: a person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 38, 225–246. doi: 10.1002/job.2170

Grewatsch, S., Kennedy, S., and Bansal, P. (2021). Tackling wicked problems in strategic management with systems thinking. Strat. Organiz. 21, 721–732. doi: 10.1177/14761270211038635

Hahn, T., and Aragón-Correa, J. A. (2015). Toward cognitive plurality on corporate sustainability in organizations: the role of organizational factors. Organiz. Environ. 28, 255–263. doi: 10.1177/1086026615604446

Hahn, T., Figge, F., Pinkse, J., and Preuss, L. (2010). Editorial trade-offs in corporate sustainability: you can't have your cake and eat it. Business Strat. Environ. 19, 217–229. doi: 10.1002/bse.674

Hejjas, K., and Scarles, C. (2019). ‘It's like hating puppies!' employee disengagement and corporate social responsibility. J. Business Ethics 157, 319–337. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3791-8

Helmig, B., Spraul, K., and Ingenhoff, D. (2016). Under positive pressure: how stakeholder pressure affects corporate social responsibility implementation. Business Soc. 55, 151–187. doi: 10.1177/0007650313477841

Hur, W. M., Moon, T. W., and Ko, S. H. (2018). How employees' perceptions of csr increase employee creativity: mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. J. Business Ethics 153, 629–644. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3321-5

Hyatt, D. G., and Berente, N. (2017). Substantive or symbolic environmental strategies? Effects of external and internal normative stakeholder pressures. Business Strat. Environ. 26, 1212–1234. doi: 10.1002/bse.1979

Jalali, M. S., and Beaulieu, E. (2024). Strengthening a weak link: transparency of causal loop diagrams - current state and recommendations. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 40, 1–18. doi: 10.1002/sdr.1753

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.2307/256287

Kelley, H. H., and Michela, J. L. (1980). Attribution theory and research. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 31, 457–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002325

Kim, D. H. (2000). Systems Thinking Tools: A User's Reference Guide, 2nd Edn. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications, INC.

Kim, H., and Andersen, D. F. (2012). Building confidence in causal maps generated from purposive text data: mapping transcripts of the federal reserve. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 28, 311–328. doi: 10.1002/sdr.1480

Lauriano, L. A., Reinecke, J., and Etter, M. (2022). When aspirational talk backfires: the role of moral judgements in employees' hypocrisy interpretation. J. Business Ethics 181, 827–845. doi: 10.1007/s10551-021-04954-6

Lubin, D. A., and Esty, D. C. (2010). The Sustainability Imperative. Harvard Business Review. Available online at: https://hbr.org/2010/05/the-sustainability-imperative (Accessed December 12, 2023).

Meyer, J., and Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 340–363. doi: 10.1086/226550

Mik-Meyer, N. (2020). Multimethod Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research. London: SAGE Publications.

Nejati, M., and Shafaei, A. (2023). Why do employees respond differently to corporate social responsibility? A study of substantive and symbolic corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 30, 2066–2080. doi: 10.1002/csr.2474

Oh, S. H., Hur, W. M., and Kim, H. (2023). Employee creativity in socially responsible companies: moderating effects of intrinsic and prosocial motivation. Curr. Psychol. 42, 18178–18196. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02852-2

Onkila, T., and Sarna, B. (2022). A systematic literature review on employee relations with csr: state of art and future research agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 29, 435–447. doi: 10.1002/csr.2210

Richardson, G. P. (1995). Loop polarity, loop dominance, and the concept of dominant polarity 1984. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 11, 67–88. doi: 10.1002/sdr.4260110106

Riemer, M., Marcus, J., Reimer-watts, B. K., Carrubbo, L., and El Bedawy, R. (2025). Organizational journeys toward strong cultures of sustainability : a qualitative Inquiry. Front. Psychol. 6:1508818. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1508818

Robertson, J. L., Montgomery, A. W., and Ozbilir, T. (2023). Employees' response to corporate greenwashing. Business Strat. Environ. 32, 4015–4027. doi: 10.1002/bse.3351

Rupp, D., Aguinis, H., Siegel, D., Glavas, A., and Aguilera, R. (2024). Corporate social responsibility research: an ongoing and worthwhile journey. Acad. Manag. Collect. 3, 1–16. doi: 10.5465/amc.2022.0006

Sancak, I. E. (2023). Change management in sustainability transformation: a model for business organizations. J. Environ. Manag. 330:117165. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.117165

Sánchez-Cardona, I., Vera, M., and Marrero-Centeno, J. (2021). Job resources and employees' intention to stay: the mediating role of meaningful work and work engagement. J. Manag. Organiz. 930–46. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2021.10

Schons, L., and Steinmeier, M. (2016). Walk the talk? How symbolic and substantive csr actions affect firm performance depending on stakeholder proximity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 23, 358–372. doi: 10.1002/csr.1381

Senge, P. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Crown Business

Shahzadi, G., John, A., Qadeer, F., Jia, F., and Yan, J. (2024). CSR beyond symbolism: the importance of substantive attributions for employee CSR engagement. J. Clean. Prod. 436:140440. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140440

Sterman, J. D. (2000). Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. Boston, MA: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Stouten, J., Rousseau, D. M., and Cremer, D. (2018). Successful organizational change integrating the management practice and scholarly literatures. Acad. Manag. Ann. 12, 752–788. doi: 10.5465/annals.2016.0095

Süßbauer, E., Maas-Deipenbrock, M. A., Friedrich, S., Kreß-Ludwig, M., Langen, N., and Muster, V. (2019). Employee roles in sustainability transformation processes. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 28((Suppl. 1), 210–217. doi: 10.14512/gaia.28.S1.7

Tomoaia-Cotisel, A., Allen, S. D., Kim, H., Andersen, D., and Chalabi, Z. (2021). Rigorously interpreted quotation analysis for evaluating causal loop diagrams in late-stage conceptualization. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 38, 41–80. doi: 10.1002/sdr.1701

Truong, Y., Mazloomi, H., and Berrone, P. (2021). Understanding the impact of symbolic and substantive environmental actions on organizational reputation. Indus. Market. Manag. 92, 307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.006

Uleman, J. F., Stronks, K., Rutter, H., Arah, O. A., and Rod, N. H. (2024). Mapping complex public health problems with causal loop diagrams. Int. J. Epidemiol. 53:91. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyae091

Vlachos, P. A., Panagopoulos, N. G., Bachrach, D. G., and Morgeson, F. P. (2017). The effects of managerial and employee attributions for corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Organ. Behav. 38, 1111–1129. doi: 10.1002/job.2189

Wandycz-Mejias, J., Salgueiro, J. L. R., and Lopez-Cabrales, A. (2025). Analyzing the impact of work meaningfulness on turnover intentions and job satisfaction: a self-determination theory perspective. J. Manage. Organ. 31, 384–407. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2024.42

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Found. Org. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Williams, A., Kennedy, S., Philipp, F., and Whiteman, G. (2017). Systems thinking: a review of sustainability management research. J. Clean. Prod.148, 866–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.002

Wolstenholme, E. F. (2003). Towards the definition and use of a core set of archetypal structures in system dynamics. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 19, 7–26. doi: 10.1002/sdr.259

Yassin, Y., and Beckmann, M. (2024). CSR and employee outcomes: a systematic literature review. Manag. Rev. Quart. 75, 595–641. doi: 10.1007/s11301-023-00389-7

Keywords: sustainability initiatives, corporate social responsibility (CSR), stakeholder engagement, sustainability implementation, micro-CSR, causal loop diagrams, systems thinking, employees' perception

Citation: Bettker Vasconcelos C, Sanchez-Zeziaga A, Henning K and van der Meer Y (2025) Evolving (dis)engagement: analyzing employees' responses to sustainability initiatives through causal loop diagrams. Front. Sustain. 6:1666622. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1666622

Received: 15 July 2025; Accepted: 17 October 2025;

Published: 21 November 2025.

Edited by:

Maria Alzira Pimenta Dinis, University Fernando Pessoa, UFP, PortugalReviewed by:

Jawad Asif, University of Gujrat, PakistanSerap Kalfaoğlu, Selçuk University, Türkiye

Manuel Do Carmo, Academia Militar - Campus da Amadora, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Bettker Vasconcelos, Sanchez-Zeziaga, Henning and van der Meer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yvonne van der Meer, eXZvbm5lLnZhbmRlcm1lZXJAbWFhc3RyaWNodHVuaXZlcnNpdHkubmw=

Carolina Bettker Vasconcelos

Carolina Bettker Vasconcelos Ane Sanchez-Zeziaga2

Ane Sanchez-Zeziaga2 Yvonne van der Meer

Yvonne van der Meer