- 1Jiangxi Institute of Fashion Technology, Nanchang, China

- 2Faculty of Business and Communication, INTI International University, Nilai, Malaysia

- 3Faculty of Management, Shinawatra University, Pathum Thani, Thailand

- 4Wekerle Business School, Budapest, Hungary

Introduction: Fashion rental is advanced as a pathway for the circular economy that addresses sustainability concerns while meeting demand for fashion variety, yet the evidence base on consumer adoption remains fragmented. This study synthesizes prior research and develops an integrative conceptual framework for why and how consumers adopt fashion rental.

Methods: We conducted a systematic literature review of 68 peer-reviewed articles indexed in Web of Science and Scopus and published between 2015 and 2024. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, studies were screened, selected, and thematically synthesized to map the state of knowledge and to construct an integrative Stimulus–Organism–Response framework.

Results: Research output has risen rapidly since 2019, with a concentration in sustainability and consumer behavior journals and a geographic focus on the United States and China. The synthesis identifies three categories of external stimuli (product attributes; platform design and service features; marketing and social cues), three types of internal psychological processes (cognitive appraisal; emotional responses; normative considerations), and two forms of behavioral outcomes (intentions; actual behaviors). The relationships from external stimuli to internal processes and onward to behavioral outcomes are significantly moderated by demographic characteristics, psychological traits, and situational factors.

Discussion: The review consolidates a fragmented literature and proposes an integrative Stimulus–Organism–Response framework that offers a more nuanced foundation than prior models by holistically incorporating external cues, a fuller spectrum of consumer psychology, and critical moderating variables. The framework advances theoretical understanding and provides actionable guidance for the design and management of fashion rental platforms, while limitations related to English-language coverage and the exclusion of grey and non-English sources are acknowledged.

1 Introduction

The escalating global environmental crisis, marked by climate change and resource depletion, has intensified the urgency for sustainable practices across all industries (Sarja et al., 2020). The fashion sector, in particular, has been scrutinized for its significant environmental impact, reportedly responsible for up to 10% of global carbon emissions and 20% of global wastewater (Abbate et al., 2023; Gazzola et al., 2020). This impact is primarily driven by the linear “take-make-dispose” model of fast fashion, which caters to the modern consumer’s desire for variety and novelty (Biyase et al., 2023). In response to these pressing challenges, the concept of a circular economy has gained significant traction, promoting business models that extend product lifecycles and minimize waste (Aus et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Hultberg and Pal, 2021; Ly, 2021). Within this paradigm, fashion rental has emerged as a disruptive and promising alternative (Monticelli and Costamagna, 2022). By offering consumers temporary access to garments rather than permanent ownership, fashion rental platforms cater to the modern consumer’s desire for variety and novelty, presenting a viable pathway toward a more sustainable and resource-efficient fashion system (Arrigo, 2021a, 2021b). This model’s potential to decouple economic growth from resource consumption signals a fundamental shift in how fashion is produced, consumed, and valued.

The growing significance of fashion rental has led to increased academic inquiry aimed at understanding the consumer adoption process. Existing literature has begun to investigate the entire consumer journey, examining how external stimuli—such as product attributes, platform features, and marketing content—trigger a series of internal evaluations within the consumer (Arrigo, 2021a, 2021b; Charnley et al., 2022; Das et al., 2022; Ramtiyal et al., 2023). These internal states, or organism variables, encompass a wide range of cognitive responses (e.g., perceived risk, perceived value), emotional reactions (e.g., pleasure, satisfaction), and the formation of attitudes and social norms (Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b; Hochreiter et al., 2023; Kim and Jin, 2019; Zhao et al., 2025). Subsequently, these internal states influence behavioral responses, from rental intentions to actual usage and word-of-mouth. However, despite these valuable contributions, the current body of research remains notably fragmented. Studies often focus on a narrow subset of these variables or are conducted from singular theoretical viewpoints, lacking a holistic perspective. This fragmentation hinders the accumulation of knowledge, making it difficult for researchers and practitioners to grasp the complete picture of the adoption process. While a few valuable reviews on sustainable fashion and rental services exist, they often focus on broader business models or specific consumer segments. A systematic, integrative synthesis of the diverse factors influencing individual consumer adoption of fashion rental, from external cues to internal psychological states, is still needed. This study aims to fill that void.

To address this fragmentation, which represents a significant gap in the literature, this study adopts a systematic literature review (SLR) approach to consolidate and synthesize the existing knowledge on consumer fashion rental behavior. Our objective is to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research and develop an integrative framework that elucidates the key determinants of consumer adoption. By doing so, we aim not only to map the existing intellectual territory but also to build a conceptual bridge that connects disparate streams of research. Specifically, this paper seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the fashion rental consumer behavior literature’s publication trends and primary disciplinary outlets?

RQ2: What are the major theoretical foundations used to explain consumer behavior in fashion rental?

RQ3: What research methods are employed in previous consumer fashion rental studies?

RQ4: What are the sample characteristics and research contexts that appear in the literature?

RQ5: Based on the S–O–R framework, how can the key factors influencing consumer behavior toward fashion rental be synthesized and integrated into a unified conceptual model?

This study offers significant contributions to both theory and practice. Theoretically, it provides a comprehensive mapping of the intellectual structure of the field of fashion rental consumer behavior. Our primary contribution is the development of a comprehensive, integrative framework that synthesizes diverse factors from the existing literature. This framework moves beyond single-theory explanations to better understand the interplay between stimuli, multi-faceted consumer psychology (cognitive and affective), and behavioral outcomes. Unlike earlier reviews of fashion rental and collaborative consumption that relied heavily on rational choice models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and therefore focused almost exclusively on cognitive antecedents, our integration of the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) paradigm explicitly incorporates emotional reactions (e.g., enjoyment and trust) and moderators (e.g., demographics, psychological traits and situational factors). By doing so, we extend the explanatory scope beyond where the TPB leaves off, providing a more nuanced theoretical contribution. For practical purposes, our findings offer actionable insights for fashion rental platforms and brand managers. By systematically identifying the key levers—from website design and product assortment to social media messaging—our research equips managers with the knowledge to design more effective marketing strategies, optimize service offerings, and enhance user engagement, ultimately fostering the growth of the circular fashion ecosystem.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we outline the rigorous and systematic methodology for conducting a literature search, screening, and analysis. We then present the descriptive and thematic results in response to our research questions. Subsequently, we discuss the findings, present the proposed integrative framework, and elaborate on its theoretical and practical implications. We conclude with a summary of the study’s limitations and a clear agenda for future research.

2 Conceptual background

The discourse on sustainable consumption has increasingly shifted towards the principles of a circular economy (CE), a paradigm designed to counteract the wasteful “take-make-dispose” trajectory of traditional linear models (Huynh, 2021). Central to the CE is the transition from product ownership to service-based access, often realized through Product-Service Systems (PSS) (Johnson and Plepys, 2021; Khitous et al., 2022). Fashion rental is a prominent example of a PSS within the apparel industry, embodying circular economy (CE) principles by extending garment lifecycles and promoting access over ownership (Armstrong et al., 2014; Fani et al., 2022; Johnson and Plepys, 2021). For this review, fashion rental is defined as a commercial transaction for temporarily using a fashion item, distinguishing it from adjacent concepts. Unlike second-hand shopping, rental does not involve the permanent transfer of ownership. It also differs from non-commercial clothing swapping by its requirement for monetary exchange, and from many “try-before-you-buy” subscription boxes, where the ultimate goal remains product sales rather than temporary access (Mobarak et al., 2025).

The fashion rental market is not monolithic, operating through several distinct models that shape consumer behavior and motivations. A primary distinction lies in the product’s source, which can be either a Business-to-Consumer (B2C) or a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) model (Arrigo, 2021a, 2021b). In the B2C model, exemplified by platforms like Rent the Runway, a company manages its inventory, offering centralized quality control and service assurances (Tang, 2022). Conversely, the P2P mode, utilized by platforms such as By Rotation, facilitates transactions between individual users, emphasizing community and access to personal closets (Marth et al., 2022). Another key dimension is the rental arrangement, which can be a one-off rental for a specific occasion or a subscription-based service offering a rotating selection of garments for a recurring fee (Kim and Jin, 2020). These different operational contexts—B2C versus P2P, and one-off versus subscription—create varied consumer experiences and are critical for understanding the nuances within the body of research on fashion rental behavior. This conceptual foundation is essential for systematically analyzing the literature and interpreting the findings within their appropriate contexts. The significant and growing market for fashion rental underscores the importance of this research. While estimates vary, recent reports place the global apparel rental market size at approximately $2.24 billion to $6.2 billion in 2023, with projections indicating a strong growth trajectory (GlobalData, 2024). This growth is driven by a confluence of factors, including increased consumer awareness of sustainability issues, a desire for affordable access to a broader range of fashion options, and the influence of digital platforms that have made renting more convenient and accessible. Understanding the drivers of consumer adoption is therefore not only of academic interest but also of critical practical importance for a market poised to become a more significant component of the circular economy.

To build a holistic understanding of fashion rental adoption, this review adopts the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S–O–R) framework (Jacoby, 2002) as its theoretical backbone. The S–O–R framework posits that environmental cues (Stimuli) trigger internal processes and states within an individual (Organism), which in turn lead to behavioral responses (Response). We chose this framework for several compelling reasons. First, its structure is inherently integrative, providing a scaffold to systematically organize the diverse and fragmented factors identified in the literature—from external service features (Stimuli) to consumers’ complex internal evaluations (Organism) and their final actions (Response). Second, unlike models such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which have been criticized for a heavy cognitive bias, the S–O–R framework explicitly accommodates a fuller spectrum of organismic states, including both cognitive and affective responses (e.g., enjoyment, trust). This allows for a more nuanced understanding of consumer psychology. As noted by Linder et al. (2021), applying the S–O–R framework enables a structured analysis of influencing factors without prematurely inferring causality, which is particularly suitable for a literature review, given that most studies employ correlational designs. By applying this framework, we can synthesize existing research in a novel way, moving beyond the description of isolated factors to present an integrated model of the consumer adoption journey.

3 Methodology

This study employs a systematic literature review (SLR), a rigorous and transparent method for synthesizing research findings (Tranfield et al., 2003). To ensure methodological transparency and comprehensive reporting, our review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021). It is essential to distinguish between SLR as a methodological approach and PRISMA as a reporting guideline that structures the presentation of our methods and findings. The review process consists of two primary stages: (1) a systematic literature search and screening process, and (2) a detailed data extraction and analysis phase.

3.1 Literature search and screening

The process of identifying relevant literature began with a comprehensive search of two leading academic databases: Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus. These databases were selected for their extensive coverage of high-quality, peer-reviewed social science journals, ensuring the academic credibility of the literature pool. A broad search string was meticulously designed to capture all relevant studies, structured around three key concepts: (1) Product Context (“Fashion” OR “Apparel” OR “Textile” OR “Garment” OR “Cloth”); (2) Business Model (“Rent”); and (3) Consumer Behavior (e.g., “behav*,” “intention*,” “attitude*,” “adoption*”). We acknowledge that our search string for the business model did not include synonyms such as “leasing,” which may represent a minor limitation of the search scope. This initial database search yielded 483 records (WOS: n = 183; Scopus: n = 300).

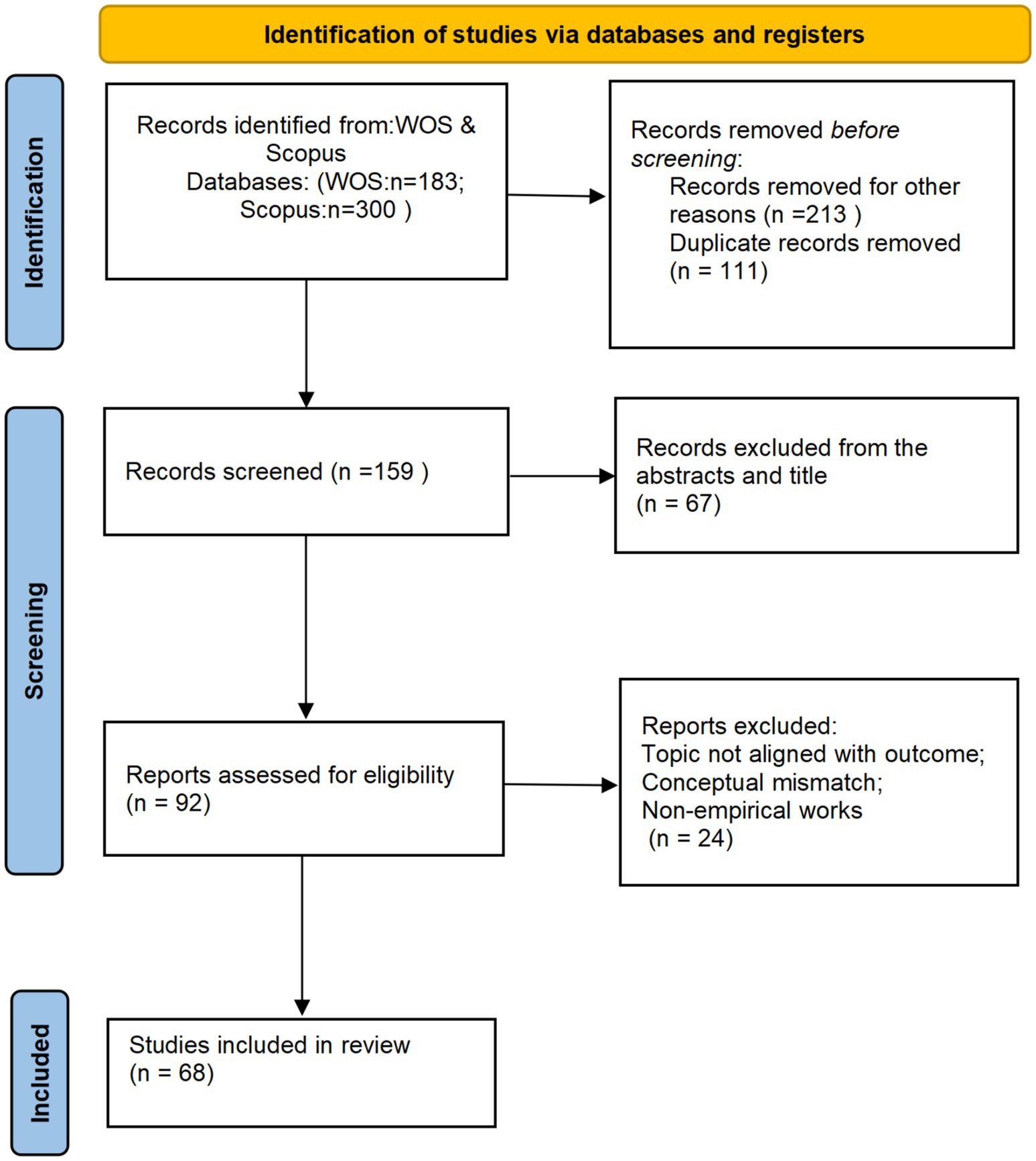

Following the initial search, a multi-step screening process was executed, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). First, we filtered the 483 records based on publication year, document type, and language. The scope was limited to articles published between January 2015 and December 2024, with a focus on the most recent research. The document type was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles to ensure academic quality, and the language was limited to English. This step narrowed the pool to 270 articles. These records were combined, and all duplicates were removed, resulting in 159 unique articles that proceeded to the thematic screening phase.

For screening these 159 articles, a precise set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was applied. Inclusion criteria required an article: (1) to be an empirical study with data analysis, and (2) to have consumer behavior in the context of fashion rental as its central theme. Exclusion criteria were used to remove articles that: (1) focused on non-consumer perspectives (e.g., supply chain, business models); (2) investigated related but distinct concepts (e.g., second-hand purchasing, non-commercial swapping); or (3) were non-empirical works (e.g., reviews, editorials, conceptual papers).

Two researchers independently applied these criteria to the titles and abstracts of the 159 articles. This process led to the exclusion of 67 studies. Any discrepancies in judgment between the researchers were resolved through discussion to achieve a consensus. The full texts of the remaining 92 articles were then retrieved and thoroughly assessed for final eligibility. In this final step, 24 articles were excluded as they did not fully meet the inclusion criteria upon detailed reading. This rigorous procedure resulted in a final sample of 68 articles deemed suitable for in-depth analysis.

3.2 Data extraction and analysis

We developed a structured data extraction form to synthesize the findings from the 68 selected articles. The following information was systematically coded from each article: (1) Bibliometric Information: authors, publication year, journal title, and primary discipline; (2) Theoretical Foundations: explicitly stated theories, models, or frameworks; (3) Research Methodology: research approach and specific methods; (4) Sample and Context: sample characteristics and study context; and (5) Key Factors: all investigated variables, constructs, and themes related to consumer behavior.

The analysis of the extracted data was conducted in two parts. First, a descriptive analysis was performed using frequency counts and summary statistics to address RQ1 through RQ4. Specifically, we analyzed bibliometric data to map publication trends and identify primary disciplinary outlets (RQ1). We summarized the coded theoretical foundations to reveal the major theories used in the field (RQ2). We profiled the methodological information to outline the dominant research methods (RQ3). Finally, we synthesized the sample and context data to describe the typical characteristics of the samples and research contexts (RQ4). Second, to answer RQ5, a thematic analysis was employed. This involved an iterative process of identifying all influential factors from the articles, coding them, and categorizing them into broader themes (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2019). To synthesize the findings and build a coherent model, the thematic analysis was guided by the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S–O–R) framework. We applied this framework to categorize the identified factors and construct a comprehensive, integrative conceptual model that illustrates the interplay between external stimuli, consumers’ internal states, and their behavioral responses in the context of fashion rental.

4 Results

This section presents the findings derived from the systematic analysis of the 68 selected articles. We provide a descriptive overview of the research trends, including publication trajectory, primary disciplinary outlets, and geographical distribution, to address Research Question 1. Subsequently, we will detail the theoretical foundations (RQ2), research methodologies (RQ3), and sample/context characteristics (RQ4) of the existing literature.

4.1 Overview of research trends

Our analysis of the bibliometric data from the 68 selected articles reveals a rapidly growing and geographically concentrated field of study. The findings highlight three key trends concerning the publication trajectory, the primary disciplinary outlets, and the geographical focus of the research.

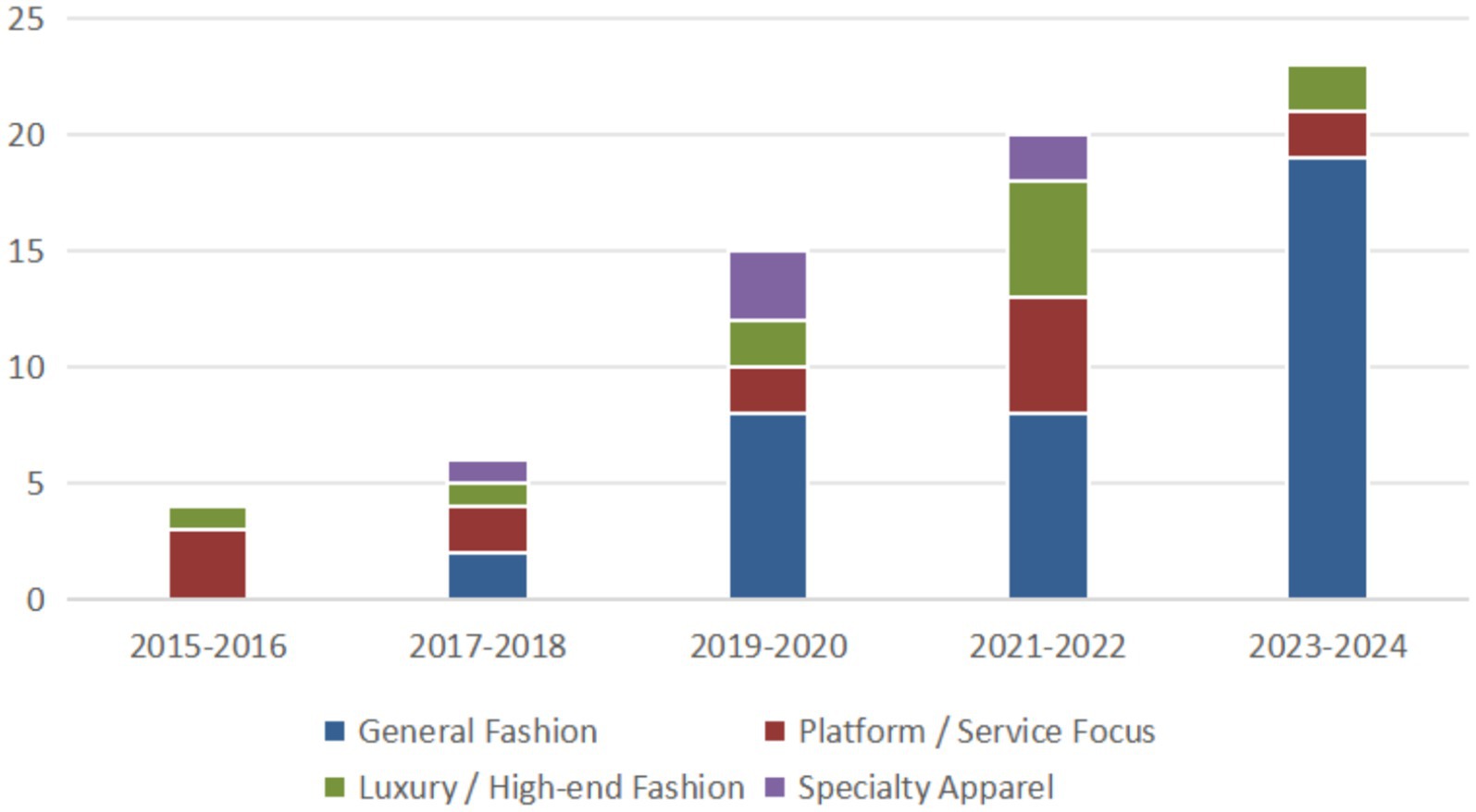

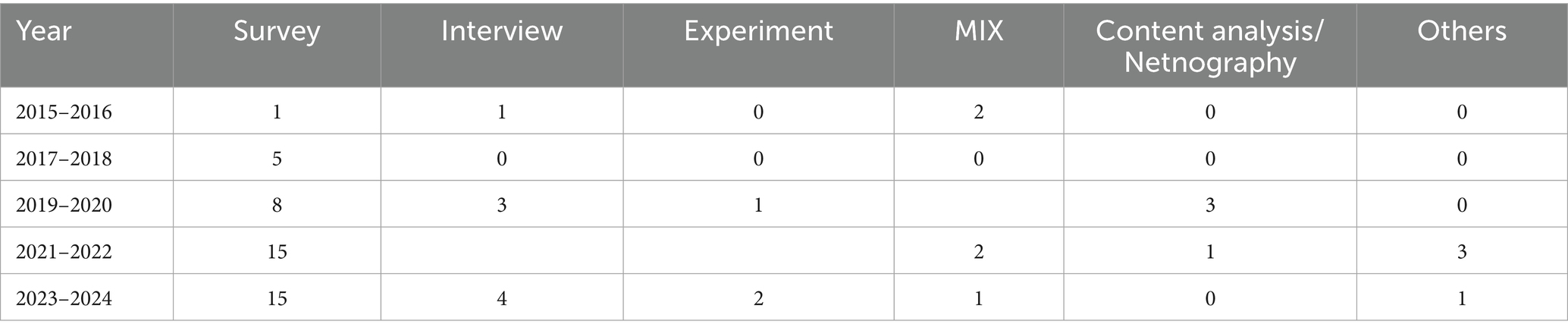

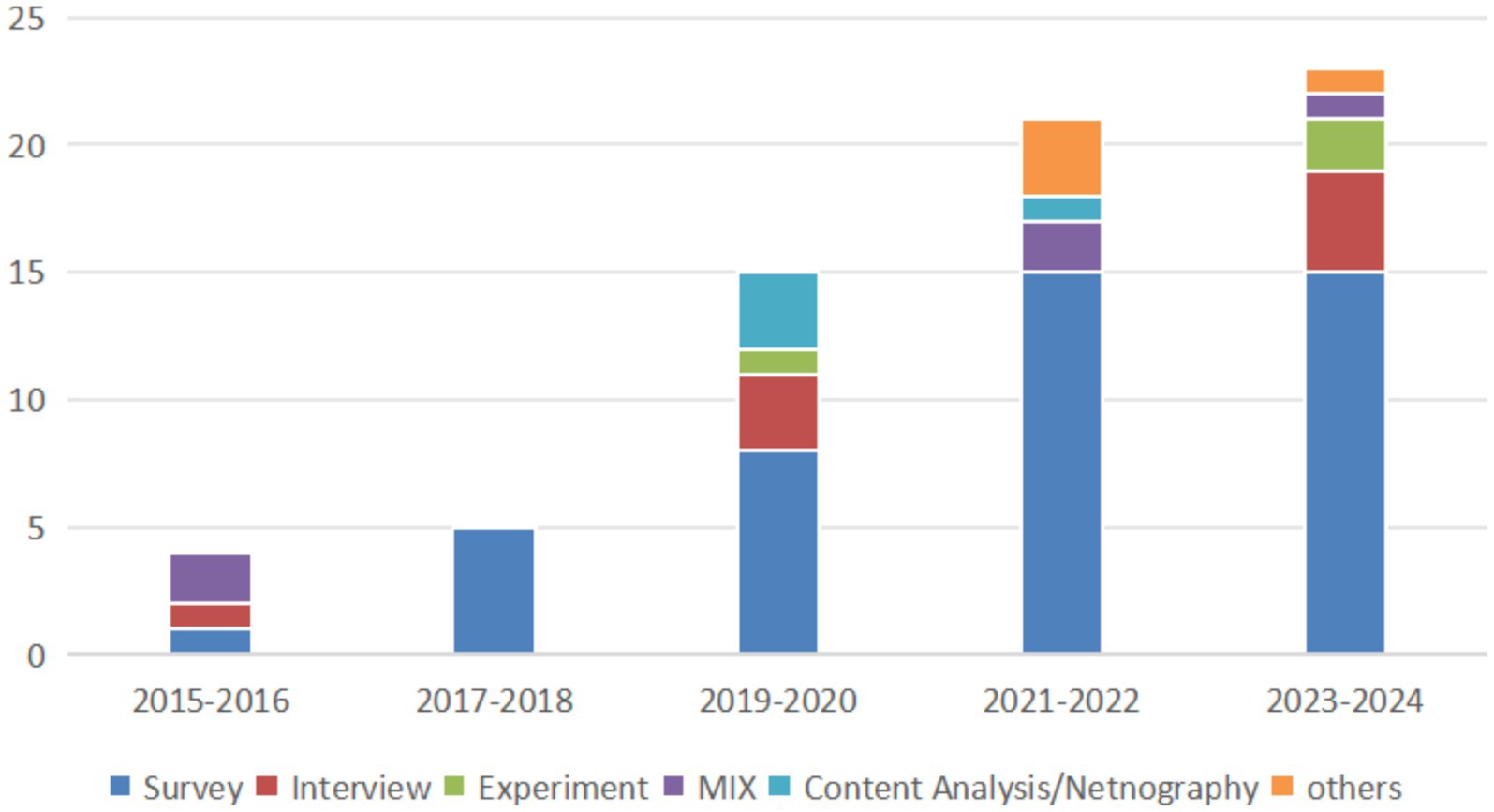

First, examining the publication timeline indicates a significant and accelerating growth in academic interest in fashion rental over the past decade. As illustrated in Figure 2, the research volume has shown a steep upward trend. The period between 2015 and 2018 saw a nascent exploration stage, with only a handful of studies published. However, the field experienced a watershed moment starting in the 2019–2020 period, with the number of publications more than doubling from the previous two-year interval. This growth continued, culminating in a dramatic increase in 2023–2024, which alone accounts for nearly half of the total literature in our sample. This rapid expansion likely reflects the increasing market relevance of fashion rental platforms and the growing urgency of sustainable consumption issues in both public and academic discourse.

The analysis also reveals a shifting focus within the research domain. While early studies (2015–2018) were more evenly distributed between general fashion contexts and a focus on rental platforms, later research shows a pronounced emphasis on “General Fashion” contexts. This suggests a maturation of the field, moving beyond initial, platform-centric questions of ‘if’ and ‘how’ consumers rent, towards a more nuanced, holistic understanding of ‘why’ this behavior is integrated into their broader consumption lifestyles. Notably, research on “Luxury / High-end Fashion” rental has also gained steady traction, particularly from 2021 onwards, indicating a growing interest in this market segment.

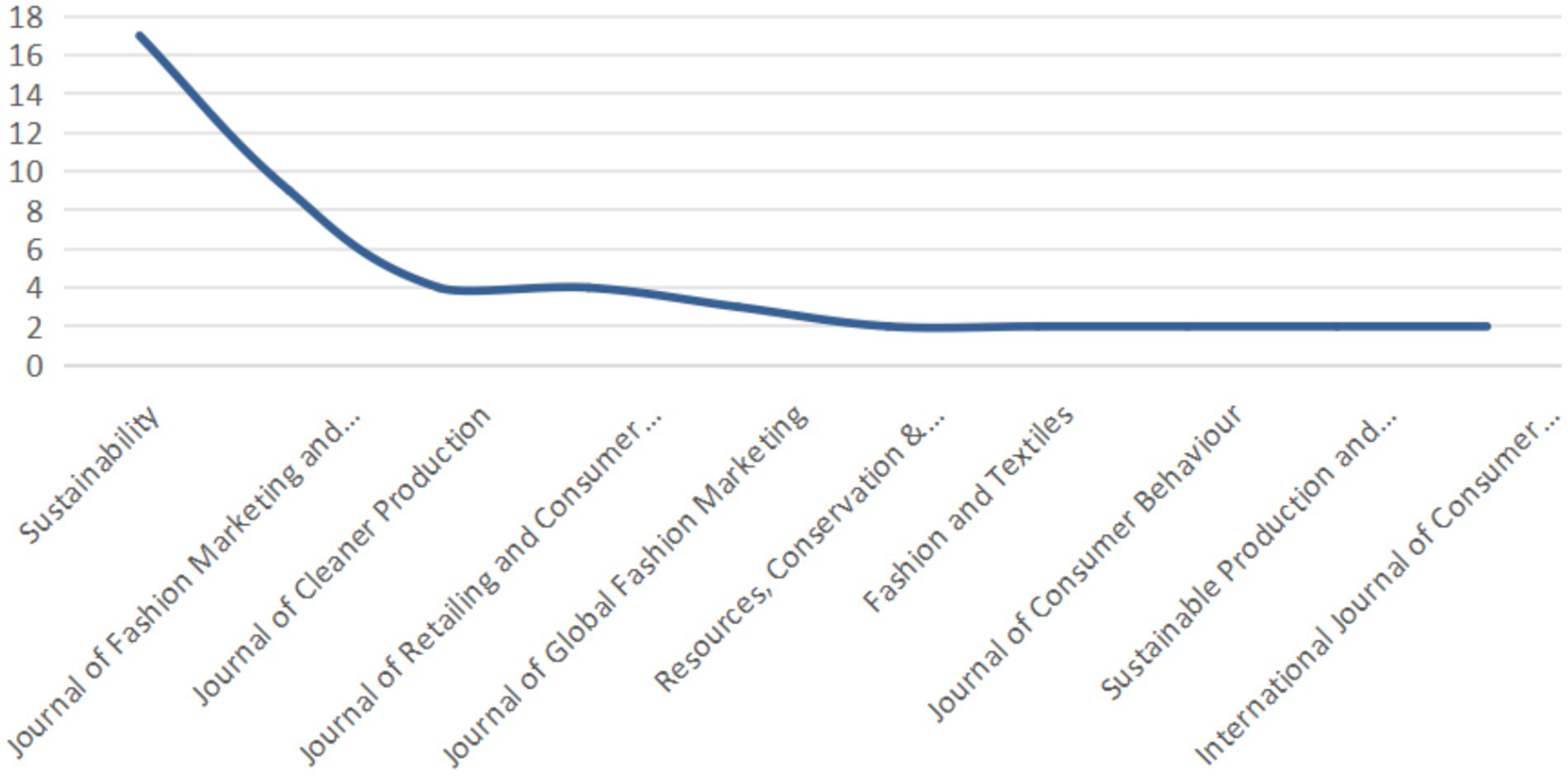

Second, regarding the primary disciplinary outlets for this research, our analysis identifies a clear concentration in journals at the intersection of sustainability, business, and consumer studies. As shown in Figure 3, the journal Sustainability emerges as the leading outlet, having published 17 of the 68 articles in our sample. This underscores the central role of environmental concerns in driving the fashion rental research agenda. The Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management (n = 9), the Journal of Cleaner Production (n = 4), and the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services (n = 4) are also significantly behind, but still notable. The prominence of these journals suggests that fashion rental research is primarily framed within the context of sustainable business management, fashion marketing, and consumer behavior studies.

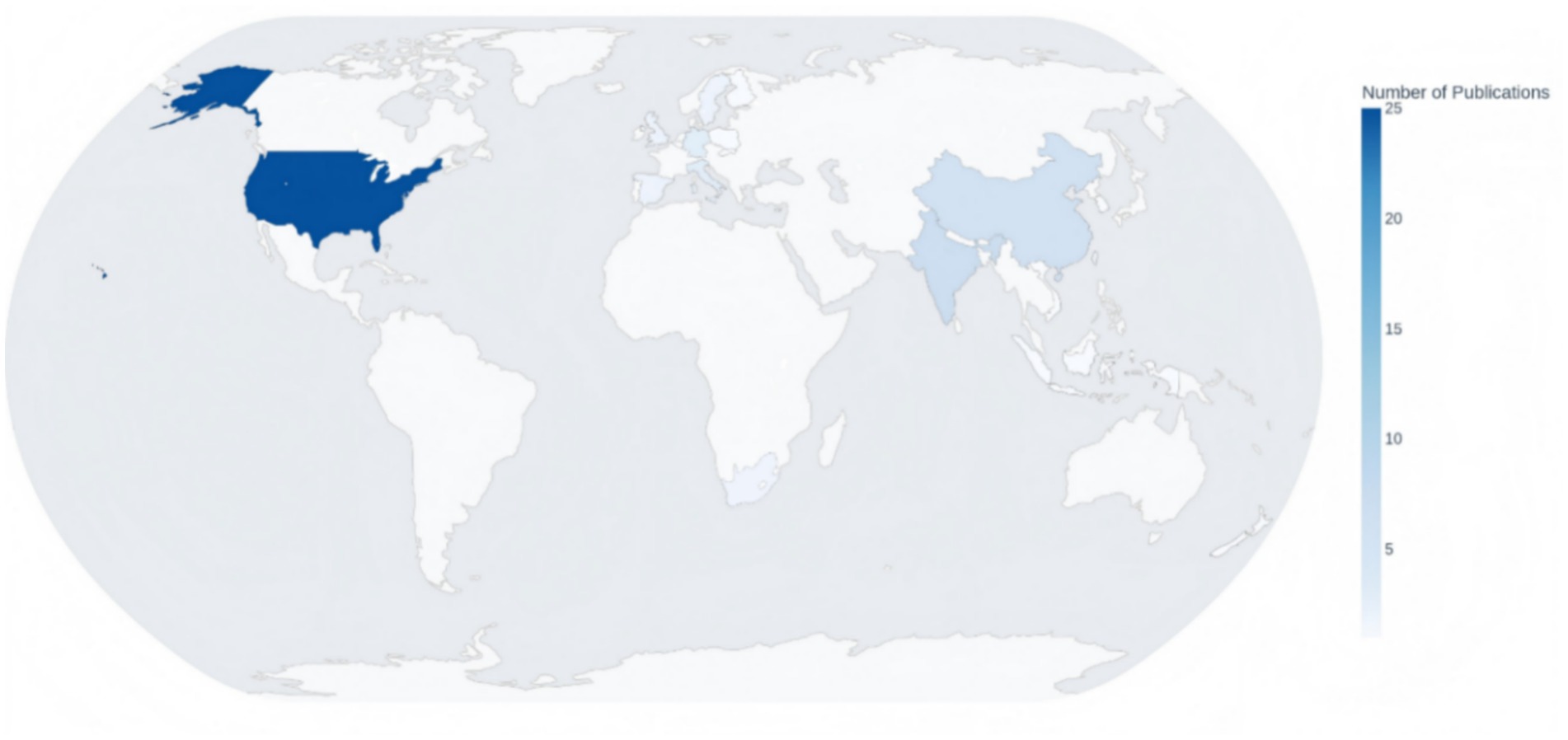

Finally, our analysis of the geographical distribution of research reveals a significant concentration of scholarly output in two major economic regions: North America and Asia. As detailed in Figure 4 and the accompanying data, the United States is the most prolific contributor, accounting for 25 of the 68 articles (36.8%) in our sample. This academic dominance likely reflects the country’s pioneering role in the fashion rental market, driven by the early emergence and significant market presence of platforms like Rent the Runway, which have become benchmark case studies (Armstrong and Park, 2019). Following the US, a notable cluster of research originates from Asia, with India (7 articles, 10.3%) and China (6 articles, 8.8%) being the next most significant contributors. The rise of research from these nations, particularly China, corresponds with the region’s expanding economic influence and its rapid adoption of innovative digital business models, especially in the sharing and e-commerce sectors (Zhang et al., 2025). European countries also make significant contributions, led by Germany and Italy (with three articles each), and the United Kingdom and Sweden (with two articles each), although their collective output is less than that of the US alone. This distinct geographical clustering strongly suggests that the current global understanding of fashion rental behavior is predominantly shaped by consumer experiences within the specific cultural and market contexts of North America and, increasingly, Asia.

4.2 Overview of theoretical foundations

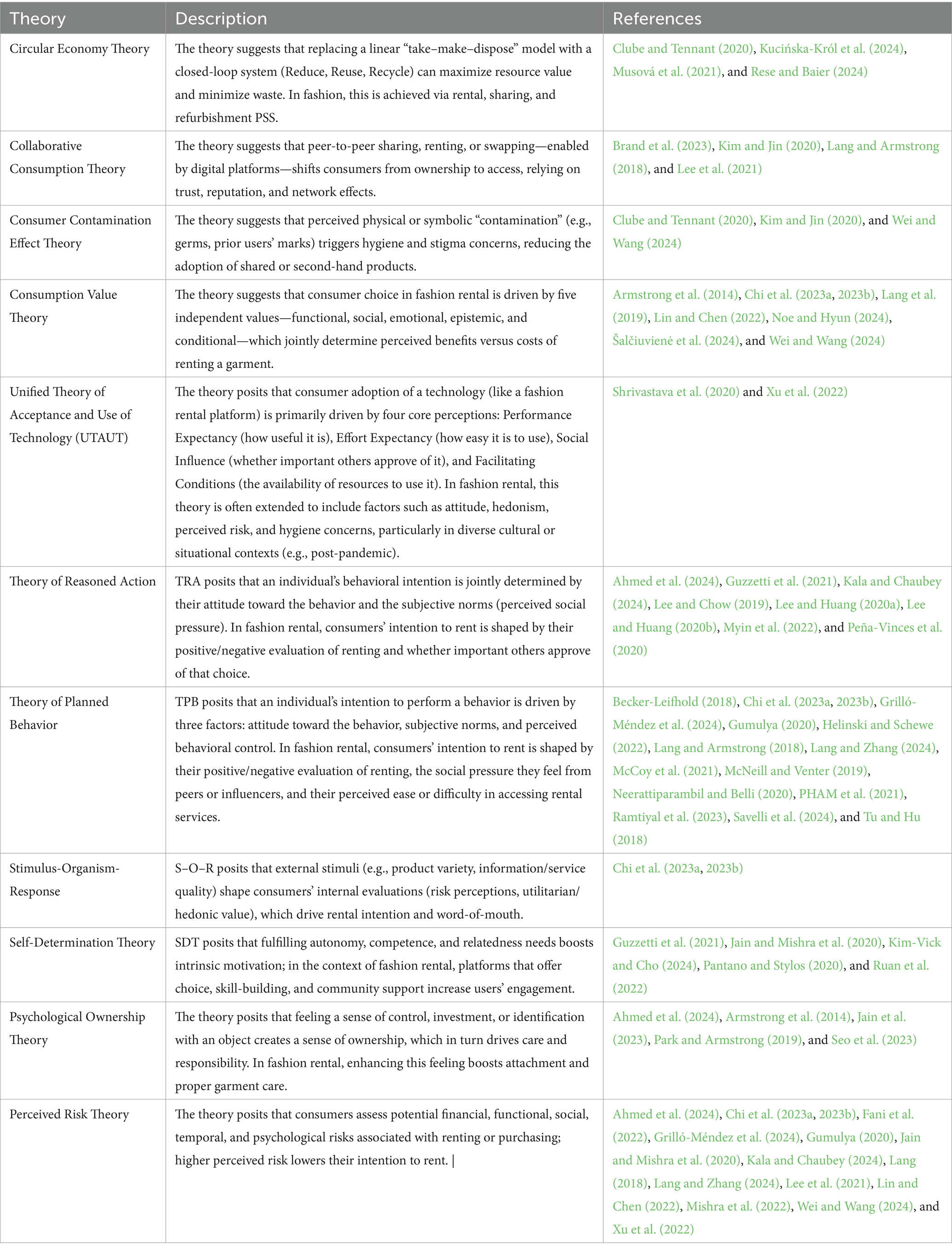

Table 1 summarizes the theoretical frameworks employed in the existing literature to explain fashion rental consumer behavior. Our analysis identifies a clear hierarchy and several thematic clusters among the theories used. At the forefront are intention-based behavioral models, with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Becker-Leifhold, 2018; Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b; Grilló-Méndez et al., 2024; Gumulya, 2020; Helinski and Schewe, 2022; Lang, 2018; Lang et al., 2019; Lang and Armstrong, 2017; Lang and Zhang, 2024; McCoy et al., 2021; McNeill and Venter, 2019; Neerattiparambil and Belli, 2020; PHAM et al., 2021; Ramtiyal et al., 2023; Savelli et al., 2024; Tu and Hu, 2018) and its predecessor, Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ahmed et al., 2024; Guzzetti et al., 2021; Kala and Chaubey, 2024; Lee and Chow, 2019; Lee and Huang, 2020a; Lee and Huang, 2020b; Mishra et al., 2020, 2022; Myin et al., 2022; Peña-Vinces et al., 2020), being the most frequently applied frameworks, highlighting the field’s strong focus on rational, cognitive antecedents like attitudes and subjective norms. This is complemented by a second prominent cluster of theories centered on value and technology adoption, where the Consumption Value Theory (Armstrong et al., 2014; Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b; Lin and Chen, 2022; Noe and Hyun, 2024; Seo et al., 2023; Wei and Wang, 2024) is used to unpack the multi-faceted benefits of renting, and the Use of Technology (UTAUT)(Shrivastava et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2022) is applied to frame rental platforms as a technology. A third group of theories delves into the unique psychological and contextual factors of access-based consumption; these include frameworks exploring barriers, such as the Perceived Risk Theory (Ahmed et al., 2024; Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b; Fani et al., 2022; Grilló-Méndez et al., 2024; Gumulya, 2020; Jain and Mishra, 2020; Kala and Chaubey, 2024; Lang, 2018; Lang et al., 2019; Lang and Zhang, 2024; Lee et al., 2021; Lin and Chen, 2022; Mishra et al., 2020; Wei and Wang, 2024; Xu et al., 2022) and the Consumer Contamination Effect Theory (Clube and Tennant, 2020; Kim and Jin, 2019; Wei and Wang, 2024), as well as those investigating nuanced drivers like Psychological Ownership Theory (Ahmed et al., 2024; Park and Armstrong, 2019; Seo et al., 2023) and Self-Determination Theory Self-Determination Theory (Jain and Mishra, 2020; Kim-Vick and Cho, 2024; Mishra et al., 2020; Pantano and Stylos, 2020; Ruan et al., 2022). The entire research stream is often situated within the broader paradigms of the Circular Economy Theory (Kucińska-Król et al., 2024; Musová et al., 2021; Papamichael et al., 2024; Rese and Baier, 2024) and Collaborative Consumption (Brand et al., 2023; Kim and Jin, 2019; Lang and Armstrong, 2017; Lee et al., 2021), which provide the overarching conceptual context. While only one study in our sample explicitly used the Stimulus-Organism-Response framework (Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b), its underlying logic—that external cues are associated with internal states which relate to behavioral outcomes—is implicitly present in many studies. This observation supports our choice to use S–O–R as an overarching structure to synthesize the fragmented findings.

4.3 Overview of research methods

Table 2 and Figure 5 illustrate the research methods employed to study consumer behavior in the fashion rental industry over the past decade. The field has evolved, with specific research approaches gaining popularity at different times. Surveys have been the most common method for understanding consumer opinions and intentions. Qualitative research, like interviews, has also been used to gain in-depth insights. Experimental research, which tests cause-and-effect relationships, is becoming increasingly common. Some studies employ a combination of methods to obtain a more comprehensive picture. This gradual diversification suggests the field is maturing, though surveys remain the dominant approach. The vast majority of survey-based studies employ cross-sectional designs rather than longitudinal approaches.

4.4 Overview of research sample and context

Our analysis of the 68 selected articles reveals distinct patterns in the research samples and contexts used to study fashion rental behavior. The findings highlight a significant focus on specific demographic groups, particularly female and young consumers, and a predominant reliance on online, B2C rental platforms as the primary research context.

First, an overwhelming majority of the studies focused on female consumers. Of the articles that specified gender, a substantial portion exclusively sampled women or had a sample heavily skewed towards female participants (e.g., 88% female, “majority female”). This pronounced gender bias suggests that fashion rental is predominantly viewed through the lens of female consumption patterns. While some studies did include balanced gender samples or specifically targeted male consumers, they represent a small fraction of the overall literature. This focus is likely driven by the market reality that women are the primary target audience for most major fashion rental services.

Second, the research has a strong inclination towards sampling younger consumer cohorts, specifically Millennials (Gen Y) and Generation Z. Many studies explicitly defined their samples as “Millennials,” “Gen Z,” “university students,” or used age brackets like “18–35” or “20–49.” This emphasis on younger generations is logical, as they are often considered early adopters of digital innovations and are typically more engaged with the sharing economy and sustainability movements. In contrast, research on older consumer groups, such as Gen X, was markedly less common, and studies including senior consumers were virtually absent.

Third, in terms of geographical and cultural context, the samples were predominantly drawn from developed economies, with a significant number of studies focusing on consumers in the United States and China. European countries (e.g., Germany, Italy, the UK, Finland) and other major Asian markets (e.g., India, South Korea) were also frequently represented. This geographical concentration aligns with the publication trends identified in section 4.1, indicating that Western and East Asian consumer perspectives largely shape the current body of knowledge. Studies from other regions, such as Africa, South America, or Oceania, were rare, with only a few exceptions noted (e.g., South Africa, New Zealand).

Finally, the dominant research context was the Business-to-Consumer (B2C) online rental platform. Many studies recruited participants through major rental websites (e.g., Rent the Runway), used online platform reviews as data, or presented hypothetical scenarios based on a typical B2C service model. This includes one-off rental services for special occasions (e.g., “formal wear rental”) and subscription-based models to a lesser extent. In contrast, research examining the Peer-to-Peer (P2P) rental context, where consumers rent from each other, was significantly less frequent. Similarly, studies investigating offline, brick-and-mortar rental services, such as local “fashion libraries,” were also in the minority. This indicates that the literature has, to date, prioritized understanding consumer interactions with large, centralized, online rental companies over other emerging models.

5 A classification framework for fashion rental adoption

As highlighted in the previous sections, numerous studies have drawn upon the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to investigate consumer intentions in the context of fashion rental. This is likely because the TPB provides a robust structure for assessing how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control shape behavioral intentions. However, while studies employing the TPB have been invaluable in identifying key psychological antecedents, they often focus on a specific set of cognitive predictors. The broader range of external stimuli (such as specific platform features or marketing communications) and the full spectrum of consumers’ internal responses (including cognitive and emotional reactions) are frequently under-examined or treated as isolated external variables rather than integral parts of a cohesive system. To develop a more comprehensive framework that explores the complex interplay between the external cues of rental services, the consumer’s internal evaluation processes, and their ultimate behavioral outcomes, this study adopts the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S–O–R) framework. Initially developed in environmental psychology (Mehrabian and Russell, 1974), this framework has been widely and effectively applied to examine consumer experience and behavior in various service and retail contexts, including online environments (Eroğlu et al., 2001; Jacoby, 2002).

Within this framework, stimulus refers to a trigger that arouses a consumer’s cognitive and affective reactions. In the context of fashion rental, this includes platform-related stimuli (e.g., product variety, service quality) and marketing-related stimuli (e.g., influencer content, social media communication). An organism refers to the internal states and evaluative processes within the consumer that are aroused by the stimuli, encompassing a wide range of cognitive responses (e.g., perceived value, perceived risk, psychological ownership) and emotional responses (e.g., enjoyment, trust, satisfaction). Finally, response refers to the final behavioral outcome resulting from the internal evaluation, which includes consumers’ behavioral intentions (e.g., intention to rent, willingness to pay) and their actual behaviors (e.g., rental usage, word-of-mouth).

We extracted all the variables examined in the 68 identified studies and classified them based on the S–O–R framework to explore their interrelationships. An iterative process was employed to categorize the variables, ensuring a systematic and coherent classification across the Stimulus, Organism, and Response components.

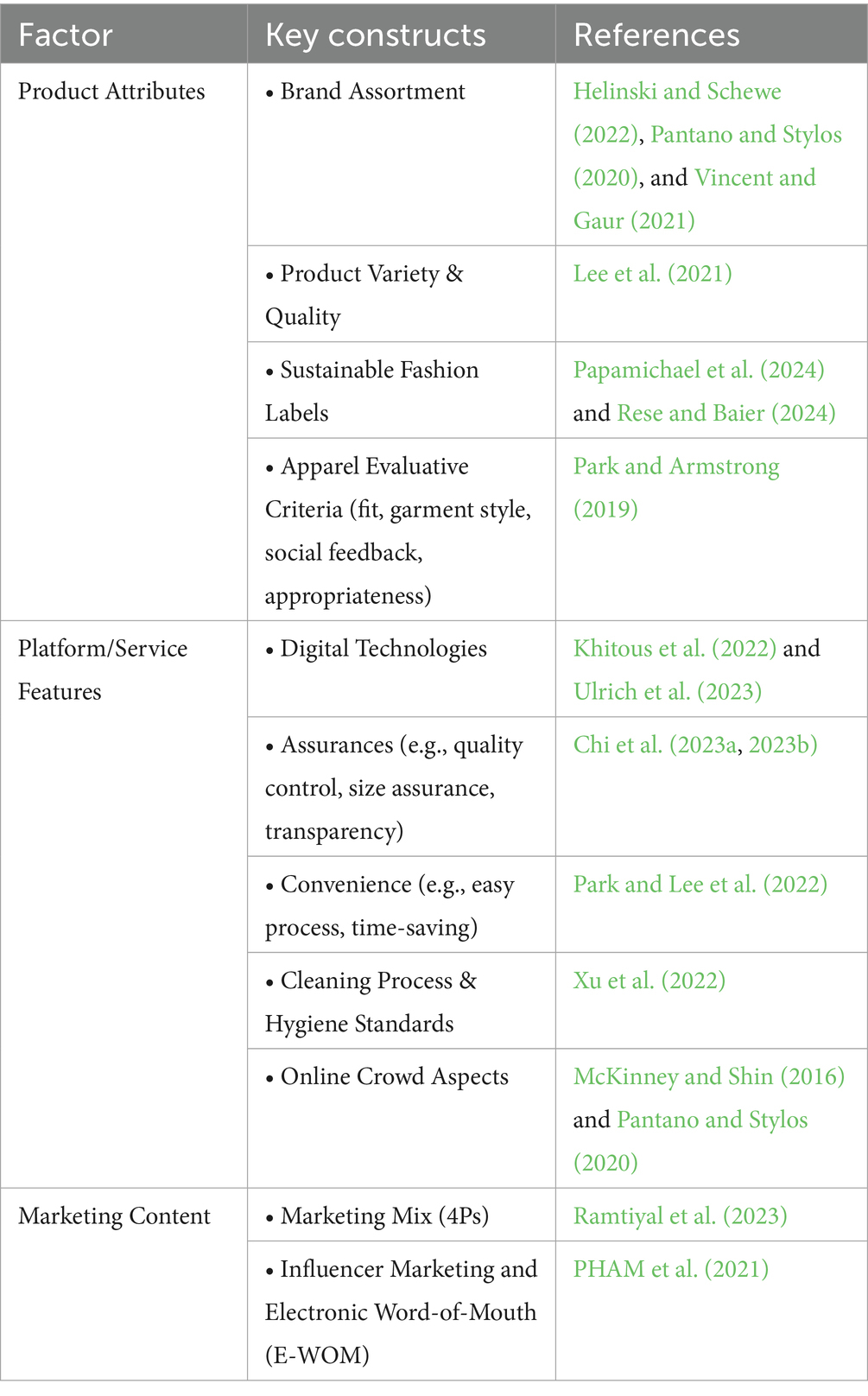

5.1 Stimuli in fashion rental adoption

The stimuli in the context of fashion rental are the various external cues provided by the rental service or the surrounding market environment that initiate the consumer’s evaluation process. Our analysis of the literature, summarized in Table 3, identifies three primary categories of stimuli: product attributes, platform/service features, and marketing content.

Product attributes encompass the essential, tangible, and intangible characteristics of garments (Lichtenthal and Goodwin, 2006). Research indicates that product variety and quality are key stimuli in attracting consumers (Lee et al., 2021). A diverse brand assortment, potentially including luxury or niche brands, can significantly motivate initial adoption (Helinski and Schewe, 2022). Moreover, sustainable fashion labels are increasingly salient for environmentally conscious consumers (Rese and Baier, 2024). Finally, consumers evaluate apparel based on garment style, fit, and occasion appropriateness, all of which are crucial stimuli in assessing the suitability of a rental service (Park and Armstrong, 2019).

Platform/Service Features encompass the functional and operational aspects of the rental service that shape the user experience (McKinney and Shin, 2016). Convenience, defined by an easy process and time-saving features, is a cornerstone of a successful rental platform (Park and Lee, 2022). Assurances regarding quality control, size accuracy, and transparency are crucial for building consumer trust. Given the nature of shared clothing, the cleaning process and hygiene standards have emerged as a particularly potent stimulus, with the power to either attract or deter consumers (Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b). Integrating digital technologies, such as advanced personalization algorithms, and managing online crowd aspects, like reviews and ratings, also act as significant stimuli influencing consumer perceptions (Pantano and Stylos, 2020; Ulrich et al., 2023).

Marketing content encompasses the communicative and promotional strategies employed by rental platforms to convey their message and effectively promote their services. Influencer marketing and electronic word-of-mouth constitute significant stimuli that shape consumer attitudes and norms by leveraging social proof to encourage adoption (Fani et al., 2022). The comprehensive marketing mix, including pricing strategies and promotional activities, represents a crucial stimulus influencing consumer responses (Ramtiyal et al., 2023).

5.2 Organism: the consumer’s internal state

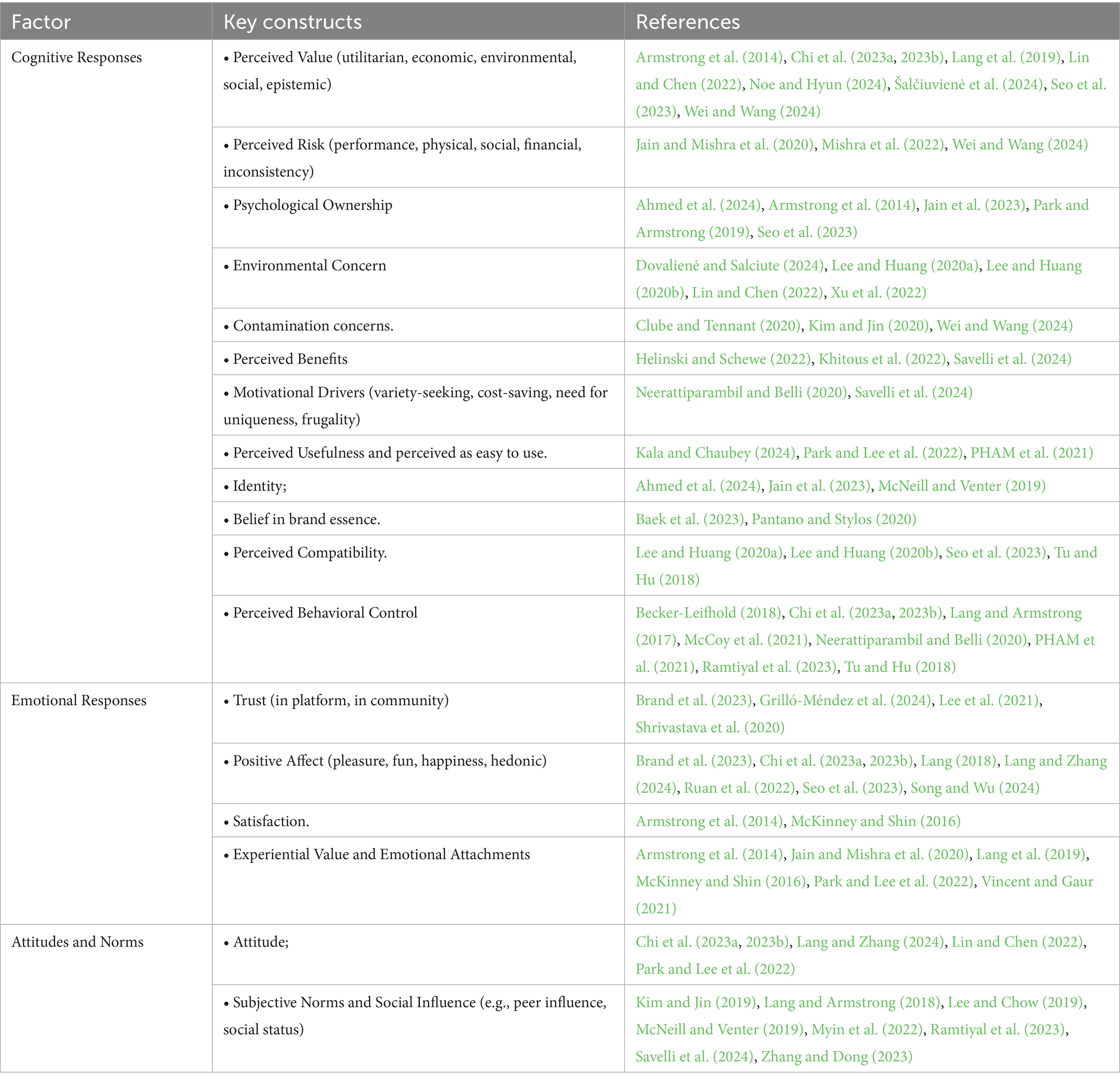

The ‘organism’ component of the S–O–R framework represents the consumer’s internal, evaluative processes triggered by the external stimuli. If stimuli are the external triggers, the ‘organism’ represents the internal world of the consumer, where these triggers are processed (Zhang et al., 2022). As shown in Table 4, the literature reveals that this internal processing is a complex interplay of ‘thinking’ (Cognitive Responses), ‘feeling’ (Emotional Responses), and the resulting ‘judging’ (Attitudes and Norms).

Cognitive responses encompass rational evaluations rooted in beliefs (Bettiga et al., 2023). Consumers engage in a central cognitive process that involves a cost–benefit analysis, weighing the perceived value against potential downsides. A significant downside is perceived risk, including performance, social, and financial uncertainties. In the sharing context, contamination concerns—the cognitive appraisal of hygiene and prior user contact—present another notable obstacle. Conversely, consumers assess perceived benefits and motivational factors, such as cost savings, variety-seeking, or the pursuit of uniqueness. Additional cognitive factors include psychological ownership, reflecting a sense of attachment to a rented item, environmental concern, aligning with personal green values, and identity. Furthermore, perceived usefulness and ease of use are crucial for evaluating the rental platform’s functionality, aligning with technology adoption models.

Emotional responses, representing the consumer’s affective reactions, are also vital (Hur et al., 2012). Frequently examined is positive affect, encompassing pleasure, enjoyment, and hedonic gratification derived from the rental experience. Trust in both the platform and its community fosters engagement by diminishing uncertainty. Satisfaction, an emotional outcome, signifies a favorable evaluation of the post-consumption experience. Experiential value and emotional attachments to the service are also noteworthy. A consumer’s conviction in a brand’s core values cultivates a robust emotional bond with the brands offered via the rental service, thereby bolstering loyalty and engagement.

Attitudes and norms, which are significantly shaped by the Theory of Planned Behavior, represent an advanced level of evaluation. A consumer’s attitude toward renting reflects their comprehensive evaluation of rental behavior, influenced by cognitive and emotional responses (McCoy et al., 2021). Subjective norms and social influence, reflecting perceived social pressures from peers, family, or influencers, consistently shape rental intentions, particularly in collectivistic societies (Lee and Huang, 2020a; Lee and Huang, 2020b). The response is the ultimate and observable result of a consumer’s interaction with stimuli and their subsequent internal evaluations.

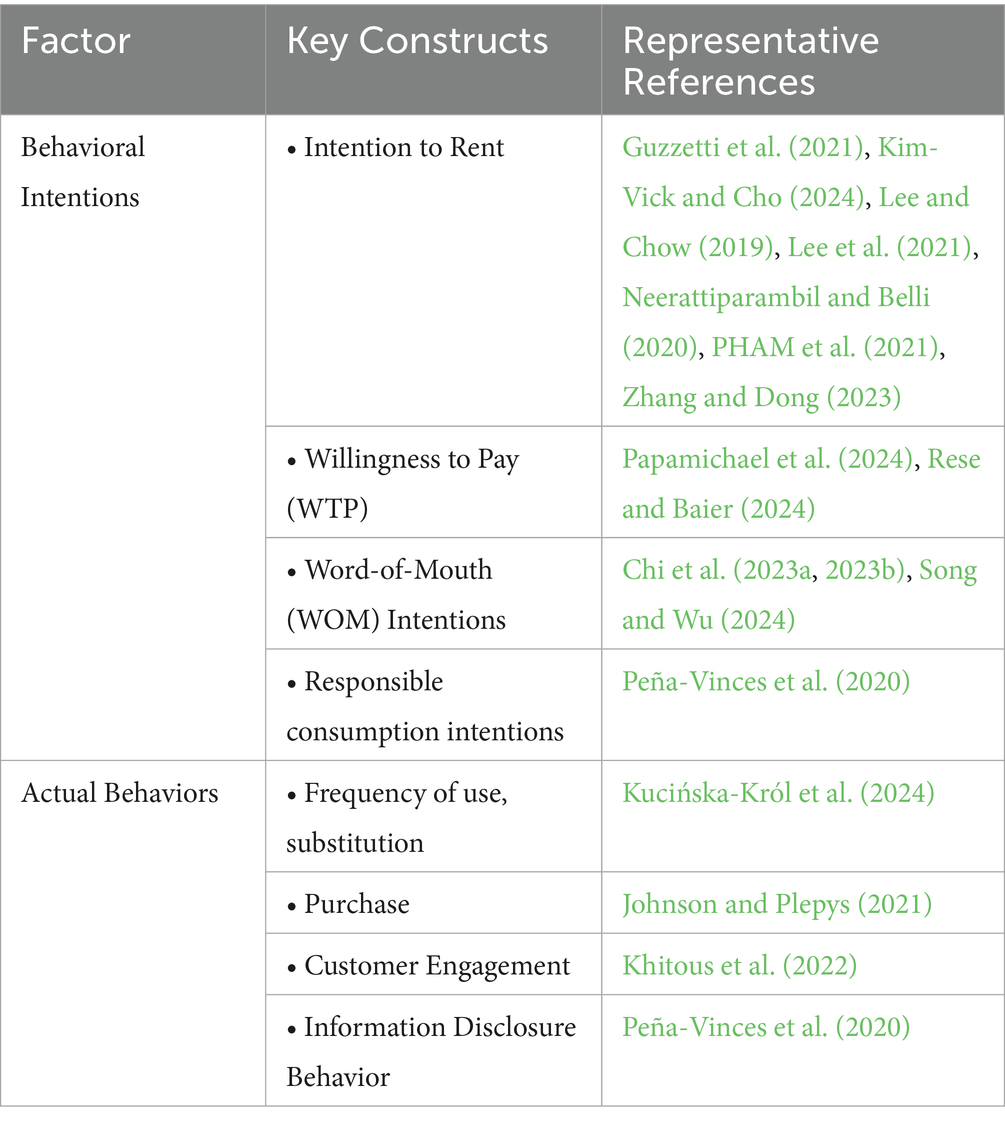

5.3 Response: behavioral outcomes

The response is the final, observable outcome of the consumer’s interaction with the stimuli and their subsequent internal evaluation. As summarized in Table 5, these outcomes can be divided into behavioral intentions and actual behaviors.

Behavioral intentions are the most commonly measured outcome variable in the reviewed literature. These intentions can be multifaceted, including the intention to rent, the intention to continue using the service (continuance intention), and the intention to recommend the service to others (word-of-mouth intention). While frequently measured as a proxy for action, it is important to acknowledge the commonly observed ‘intention-behavior gap,’ where intentions do not always translate into actual behavior.

Actual behaviors, though less frequently studied due to data collection challenges, offer definitive evidence of adoption. These encompass the frequency of use and the substitution rate of rental, indicating the extent to which renting replaces new purchases. Moreover, customer engagement with the platform and information disclosure behavior are critical behavioral outcomes that support the rental platform’s ecosystem.

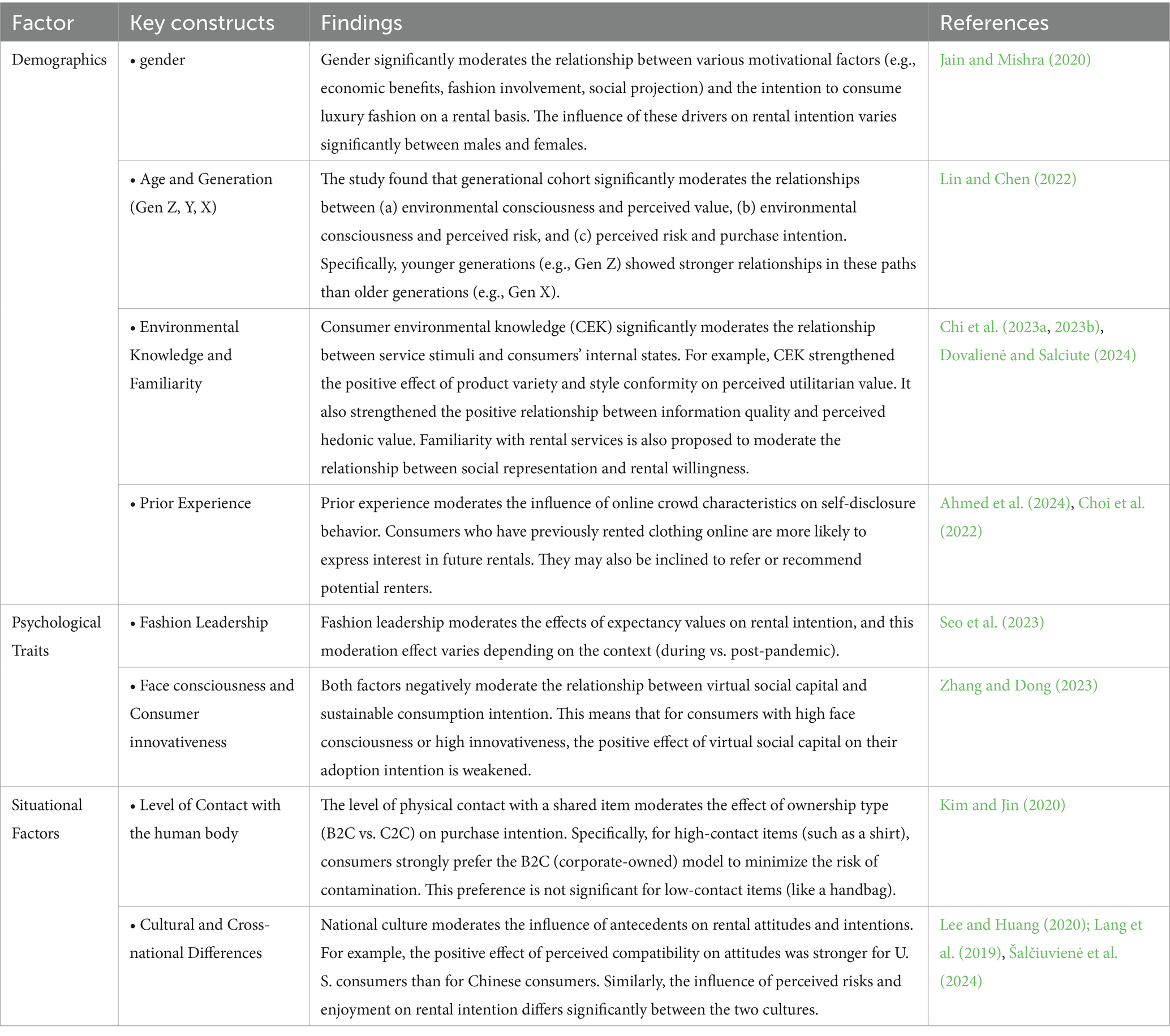

5.4 The role of moderating factors

A crucial finding from our systematic review is that the relationships within the S–O–R framework are not universal but are often moderated by a range of individual and situational factors, as detailed in Table 6. These moderators explain why different consumers react differently to the same stimuli.

Demographics, such as gender and age/generation, have been shown to alter consumer responses significantly. For instance, the drivers of rental intention can vary significantly between males and females, as well as younger generations, such as Gen Z, who perceive environmental consciousness and perceived risk differently than older cohorts (Plepy, 2021).

Psychological Traits play a profound moderating role. A consumer’s level of environmental knowledge can strengthen the effect of service features on their internal value perceptions. Prior experience with renting weakens the influence of social norms, as experienced users tend to rely more on their own judgment. Similarly, personality traits such as fashion leadership, face consciousness, and consumer innovativeness determine how susceptible a consumer is to social influence and how readily they adopt novel consumption models. Face consciousness refers to an individual’s concern with maintaining social image and status in front of others, while consumer innovativeness captures the tendency to adopt new products or services quickly. Another moderating construct, virtual social capital, reflects the trust, reciprocity, and network resources that consumers accumulate in online communities; this social currency can strengthen or weaken the effect of social norms on rental intention.

Finally, Situational Factors, including the level of physical contact with the garment and the overarching cultural context, are powerful moderators. The preference for a professionally managed (B2C) versus a peer-to-peer (C2C) model is strongly influenced by whether the item is high-contact (such as a shirt) or low-contact (like a handbag). Moreover, cross-national studies consistently find that the influence of factors such as perceived compatibility and social norms on rental intentions differs significantly between cultures, including the U. S. and China, highlighting the importance of cultural adaptation for rental platforms. Understanding these moderating effects is critical for firms aiming to personalize their marketing strategies and product offerings.

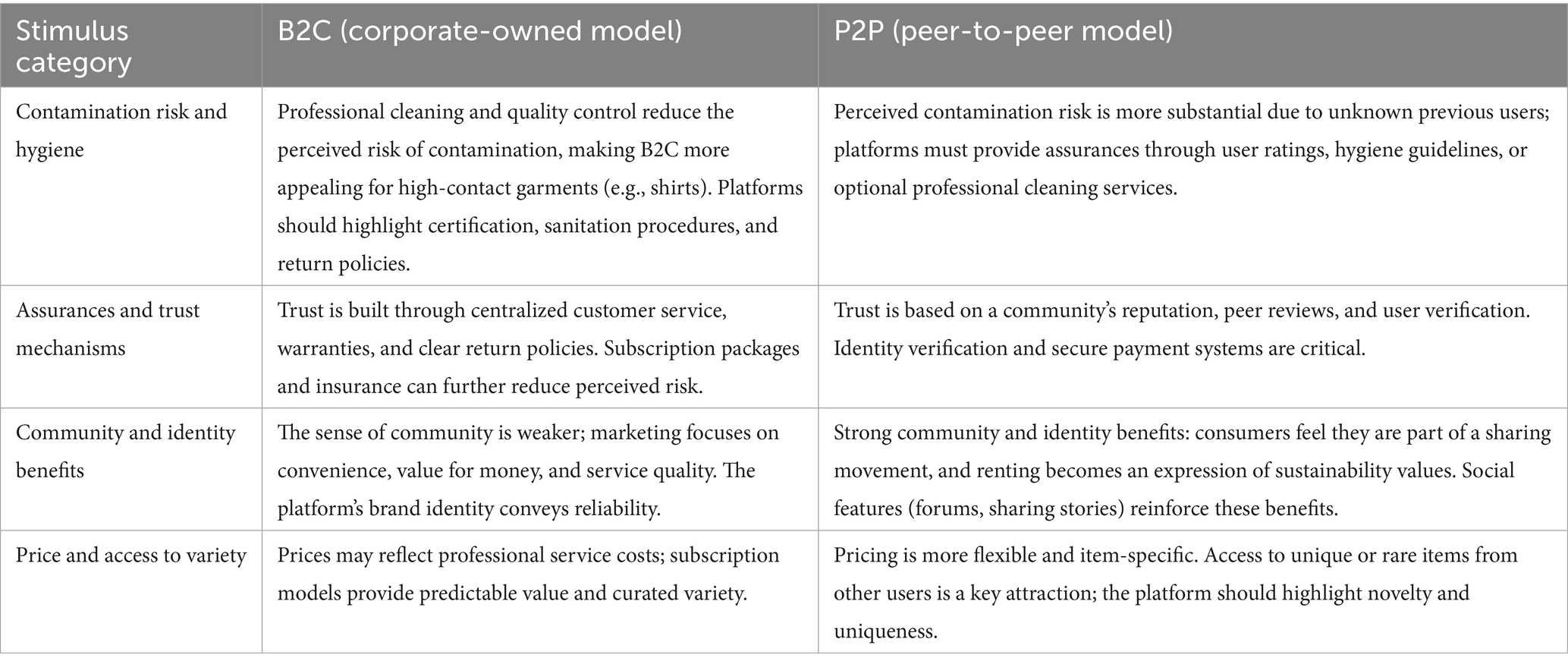

5.5 Contextual differences between B2C and P2P models

While the integrative S–O–R framework captures the general adoption process, our review also indicates that the same stimuli can have markedly different effects depending on the operational model used. Business-to-consumer (B2C) platforms manage inventory centrally and thus offer professional assurances and standardized services, whereas peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms facilitate exchanges between individuals and rely more on community dynamics. Table 7 summarizes how key stimuli operate differently across these models. Understanding these nuances helps to tailor strategies to the appropriate context.

In addition to these differences, the level of physical contact interacts with the model type. For high-contact items (e.g., blouses), contamination risk can outweigh other benefits, making B2C more attractive, whereas for low-contact items (e.g., handbags), community and identity cues in P2P can be more persuasive.

6 A framework for fashion rental adoption

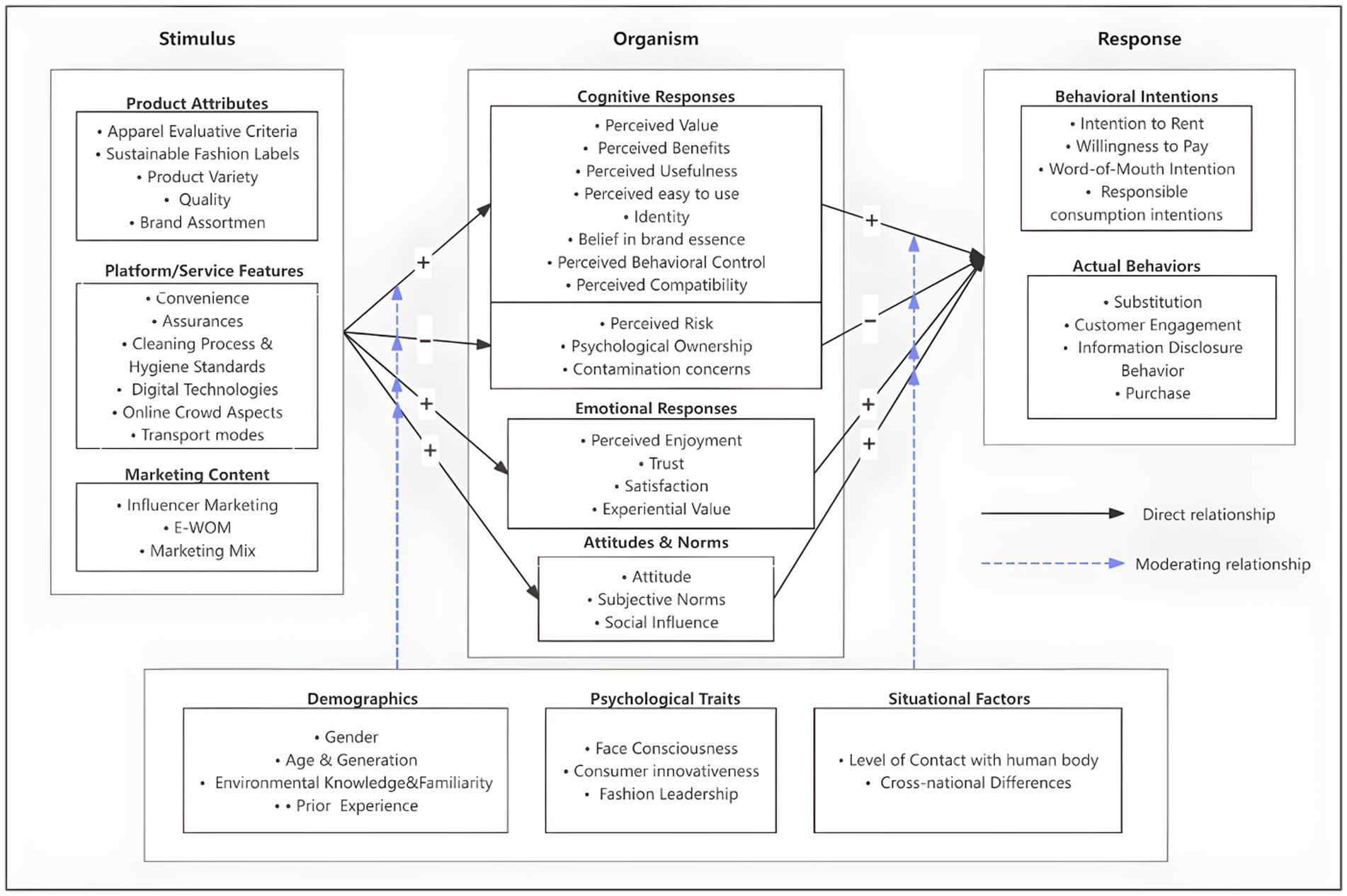

Although previous studies have examined diverse aspects of fashion rental adoption, the current review reveals that no comprehensive framework has been employed to explore the intricate relationships between these factors. This includes the interplay among service stimuli (e.g., product attributes, platform features), the consumer’s internal organismic states, cognitive responses, emotional reactions, overarching attitudes and norms, and the resulting behavioral responses. By acknowledging the research gaps in the existing literature, this study builds on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S–O–R) paradigm to propose an integrative framework for consumer adoption of fashion rental, as illustrated in Figure 6. Our literature analysis revealed that service stimuli, encompassing tangible attributes, intangible features, and marketing content, have a significant influence on consumers’ cognitive and affective reactions. Our findings underscore the importance of comprehensively understanding the various types of stimuli that elicit these internal responses. The fit between the service stimuli and the marketing content should be carefully considered when developing a fashion rental platform to provide consumers with an engaging and trustworthy experience. Our literature analysis also reveals that prior research has not sufficiently emphasized the direct relationship between service stimuli and consumer behavioral outcomes. Instead, studies have consistently shown that service stimuli lead to behavioral outcomes primarily by mediating consumers’ cognitive and affective reactions (Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b; Lee and Huang, 2020a; Lee and Huang, 2020b).

Accordingly, the framework posits that service stimuli (Stimulus) influence consumers’ cognitive and affective reactions (Organism), which in turn influence the behavioral outcomes of fashion rental adoption (Response). Drawing on the findings from our systematic review, the framework further posits that individual and situational differences play a crucial moderating role. These moderators, which include demographics, psychological traits, and situational factors, influence the strength or direction of the relationships (1) between the service stimuli and consumers’ internal states and (2) between consumers’ internal states and their behavioral outcomes. Solid lines represent the direct relationships in the framework, while the moderating effects are depicted by dotted lines in the illustration of this framework (see Figure 6).

To enhance testability, Figure 6 explicitly indicates the hypothesized direction of each relationship. Stimuli that increase perceived value, trust, enjoyment, or subjective norms are labeled as “+” (facilitating). Stimuli that heighten perceived risk, anxiety, or effort are labeled as “–” (inhibiting). Cognitive states exert “+” or “–” effects on attitudes depending on the balance between value and risk, whereas positive affect (e.g., trust, enjoyment, satisfaction) exerts “+” effects. Solid arrows denote direct effects; dashed arrows represent moderating influences of demographics, psychological traits, and situational factors (e.g., B2C vs. P2P, contact level).

7 Discussion

The growing interest in fashion rental as a key strategy for the circular economy is evident in both academic and practitioner discourse (Bodenheimer et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2020). However, our systematic review reveals a critical paradox: while interest is high, the theoretical foundation remains surprisingly fragmented. The literature is characterized by a mosaic of studies examining specific drivers or barriers in isolation, often relying on singular cognitive models, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Arrigo, 2021a, 2021b; Jain et al., 2021). As our analysis reveals, this piecemeal approach has hindered the development of a comprehensive understanding of the consumer adoption process.

In response to this fragmentation, our study makes a pivotal contribution by developing a comprehensive classification framework grounded in the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S–O–R) paradigm. This moves the field beyond mere description of isolated factors. Unlike prior models, often criticized for their heavy cognitive bias, our S–O–R framework explicitly integrates external stimuli (e.g., platform features), a fuller spectrum of organismic states (including crucial emotional responses like enjoyment and trust), and critical moderating variables. Doing so provides a more robust and dynamic theoretical platform for future research, allowing scholars to test, verify, and ultimately revise our collective understanding of this emerging consumption model. The remainder of this discussion will elaborate on the theoretical and practical implications of this integrative work before outlining a clear agenda for future research.

7.1 Theoretical implications

This study offers several significant theoretical implications for the field of sustainable consumption.

First, by systematically mapping the intellectual structure of fashion rental research, we provide a comprehensive overview of this burgeoning domain. Our findings confirm that the field is rapidly expanding, highlighting a concentration in specific theoretical and geographical contexts, echoing similar maturity assessments in adjacent fields, such as general collaborative consumption (Ertz and Leblanc-Proulx, 2018). This mapping is a crucial baseline for future scholars to identify under-explored areas and position their contributions.

Second, our primary contribution is the development of an Integrative Framework for Fashion Rental Adoption based on the S–O–R model that moves beyond mere description of isolated factorsWhile established theories like TPB and TRA provide valuable foundations, our framework synthesizes and organizes factors from across different theoretical approaches in a new way, explicitly integrating external stimuli (e.g., platform features), a fuller spectrum of organismic states (including crucial emotional responses like enjoyment and trust), and critical moderating variables. This provides a more comprehensive and nuanced theoretical foundation for understanding the adoption of fashion rental. By organizing the existing literature within this framework, we bring coherence to a fragmented field and provide a clear path for the development of cumulative knowledge.

Third, our framework highlights the importance of moderators, adding theoretical nuance. We demonstrate that the relationships between stimuli, organism, and response are not universal across all contexts. For example, our review reveals that cultural context significantly moderates consumer responses (Lang et al., 2019; Lee and Huang, 2020a; Lee and Huang, 2020b), and psychological traits, such as fashion leadership, influence the impact of marketing stimuli (Seo et al., 2023). This provides a theoretical basis for moving from universal models to more context-sensitive, contingent theories of fashion rental adoption.

Finally, by explicitly incorporating moderating variables, our framework introduces a new layer of theoretical nuance. We demonstrate that the relationships between stimuli, organism, and response are not universal. For example, our review reveals that cultural context significantly moderates consumer responses (Lang et al., 2019; Lee and Huang, 2020a; Lee and Huang, 2020b), and psychological traits, such as fashion leadership, influence the impact of marketing stimuli (Seo et al., 2023). This provides a theoretical basis for moving from universal models to more context-sensitive, contingent theories of fashion rental adoption. Our synthesis highlights boundary conditions for S–O–R generalizability. Evidence skews toward young, female samples in Western/East Asian markets and B2C contexts, indicating scope conditions for observed links. Value–risk trade-offs vary by demographics, B2C vs. P2P, and contact level, affecting attitudes, norms, and intentions. We recommend: (1) stratified, diverse samples with multi-group tests; (2) designs contrasting B2C and P2P with contact manipulations; and (3) moderators including face consciousness, innovativness, and environmental knowledge. Treating these as boundary conditions clarifies the reach of our propositions.

7.2 Practical implications

The proposed framework offers actionable insights for fashion rental platform managers, brand strategists, and marketers.

For platform managers, the framework acts as a strategic dashboard. It highlights that success depends on holistically managing all three S–O–R components. It is not enough to have a good product assortment (Stimulus); platforms must also manage the entire user experience to foster positive internal states (Organism). Our findings on the importance of ‘Assurances’ and ‘Hygiene Standards’ as key stimuli confirm the critical need to mitigate perceived risks, a well-documented barrier in the sharing economy (Chi et al., 2023a, 2023b). Therefore, managers should invest in superior cleaning processes and transparently communicate these processes to build trust.

For marketers, our framework underscores the power of targeted communication. The ‘Marketing Content’ stimulus is highly effective, particularly influencer marketing and e-WOM. This confirms the findings of studies on the influence of social media in fashion (Lee et al., 2022; Pham et al., 2021). However, our model suggests a more nuanced approach: marketing messages should be tailored to trigger specific cognitive (e.g., highlighting economic value) and emotional (e.g., showcasing the joy of variety) responses. Furthermore, understanding the role of moderators is key. For instance, knowing that younger consumers (Gen Z) are more influenced by sustainability claims (Lin and Chen, 2022) allows marketers to create more resonant and effective campaigns for that segment.

For brand strategists, the framework reveals the importance of managing the brand’s perceived essence and the consumer’s psychological ownership. The finding that ‘Belief in brand essence’ and ‘Psychological Ownership’ are key organismic states suggests that rental should not feel like a sterile, transactional service. Brands can foster a sense of temporary ownership or ‘stewardship’ through personalization and community-building features, a strategy that has proven effective in other access-based models (Fritze et al., 2020). This can transform a simple rental into a meaningful brand experience, fostering long-term loyalty and customer satisfaction.

7.3 Environmental implications and sustainability considerations

Although rental services are often portrayed as a circular solution, our review indicates that their environmental impacts vary widely depending on operational practices. Transportation emissions and cleaning processes can offset the benefits of extending garment life. For example, a recent life-cycle assessment study found that transportation emissions play a significant role in the overall carbon footprint of fashion rental models—so significant, in fact, that buying and discarding a pair of jeans may be less carbon-intensive than renting one. There is also the environmental cost of dry cleaning or laundering clothing after each rental; common solvents, such as perchloroethylene, are associated with water, soil, and air contamination and pose risks to human health.

Recent life-cycle assessments provide a nuanced picture. When rental meaningfully extends garment use and substitutes new purchases, and when reverse logistics and cleaning are efficient, rental can lower impacts relative to ownership—e.g., case studies on formalwear show reductions per use as the number of wears increases (Monticelli and Costamagna, 2022; Johnson and Plepys, 2021). Conversely, when transportation distances are high, packaging is intense, or garments are frequently dry-cleaned, the gains can be eroded. In jeans scenarios, an ERL study finds that rental can even exceed ownership in global warming potential under assumptions of car-based pickups and frequent cleaning (Levänen et al., 2021). Taken together, the sustainability of rental is conditional on (i) high utilization (many wears per item), (ii) optimized reverse logistics (local hubs, consolidated routes), and (iii) low-impact cleaning (wet/CO₂ cleaning, home laundering where appropriate). These parameters should be treated as boundary conditions when interpreting environmental claims and when designing rental operations.

These findings highlight that rental schemes only achieve environmental benefits when garments are used frequently (high use density) and logistics are optimised. Use-density thresholds should be established, and platforms should minimize travel distances by offering local pickup points and encourage the bundling of deliveries and returns. Investing in greener cleaning technologies and encouraging home laundering where appropriate can further reduce impacts. Future research should quantify these thresholds under different scenarios and integrate environmental metrics into behavioral models.

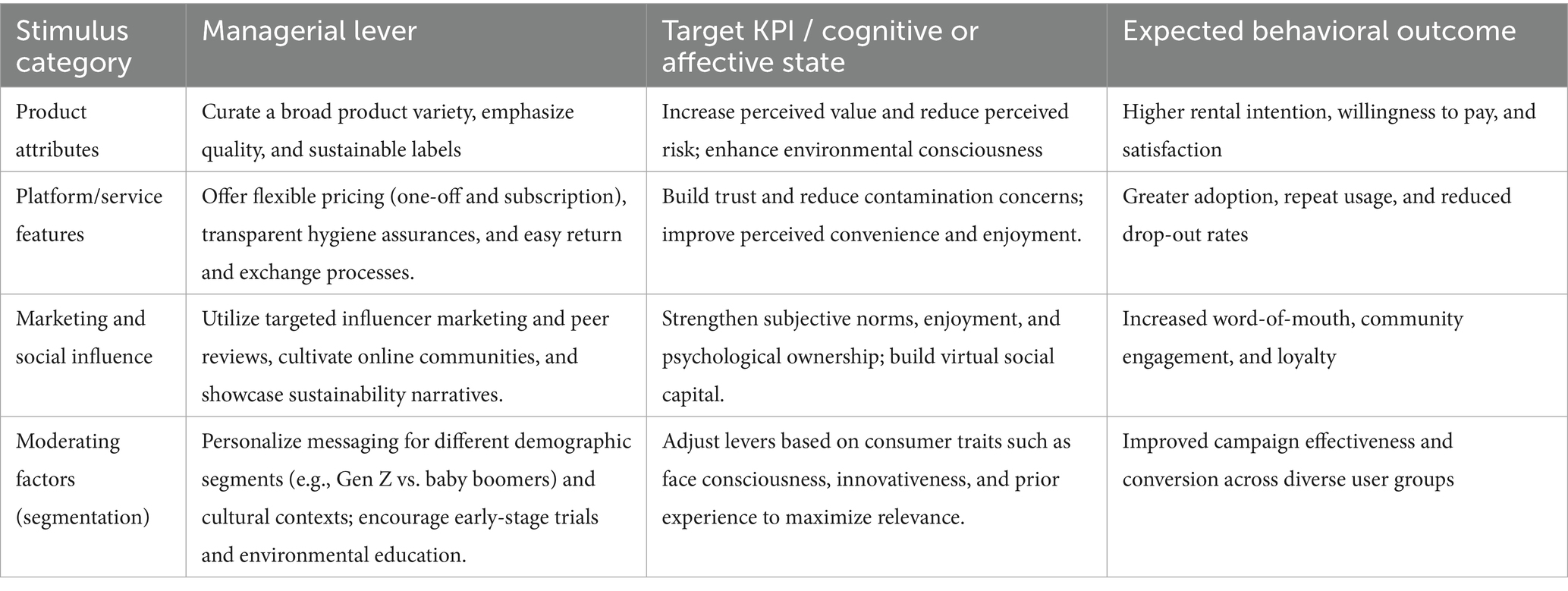

To translate the integrative S–O–R framework into actionable guidance, Table 8 provides a checklist that maps stimuli to concrete managerial levers, the key performance indicators (KPIs) they influence, and the expected effects on consumer psychology and behavior. This mapping clarifies how managers can design interventions that target specific cognitive or emotional responses, thereby driving the adoption of rental services.

7.4 Limitations and future research agenda

While this study provides a comprehensive framework, several limitations must be acknowledged, each of which, in turn, opens up important avenues for future research. First, our review was restricted to English-language peer-reviewed journal articles indexed in Web of Science and Scopus. This strategy enhances quality control but may have excluded relevant grey literature (e.g., industry white papers, theses, technical reports) and non-English scholarship that could shift effect sizes or reveal context-specific mechanisms. Future reviews could broaden the database scope (e.g., ProQuest Dissertations, Google Scholar, regional indexes) and include multilingual searches with transparent screening protocols. Second, as the field matures and more studies employ comparable measures, future research could build on our framework to conduct a quantitative meta-analysis, which represents a promising avenue for further investigation. Third, our review highlights several promising areas for future inquiry. There is a clear need for more research on the role of negative emotions (e.g., guilt, anxiety about hygiene) and how platforms can mitigate them. Further investigation into the long-term behavioral impacts of fashion rental, such as its effect on overall consumption patterns and the potential for a ‘rebound effect,’ is also crucial. Furthermore, additional cross-cultural research is necessary to validate the generalizability of our framework beyond the dominant US and Asian contexts. Finally, future studies should explore the ‘dark side’ of fashion rental. This requires investigating whether consumer perceptions of logistical and environmental trade-offs (e.g., awareness of CO2 emissions from delivery) act as cognitive or emotional barriers to adoption, and under what conditions fashion rental might create a ‘sustainability paradox’ with higher net environmental impact than other consumption modes.

Building on these limitations and the gaps identified throughout our review, we propose a clear research agenda to guide the field toward a more mature and nuanced understanding of the topic. This agenda moves beyond simple descriptions to pose critical questions for future inquiry. A primary direction is to deepen the understanding of context-specific stimuli. For instance, future research should investigate how different communication strategies for hygiene—a critical stimulus—differentially impact consumers’ perceived risk of contamination and their willingness to pay a premium for it. Another crucial area is elaborating on psychological ownership in an access-based context. Here, the key challenge is to explore how digital interventions, such as gamification or personalized impact tracking, can be designed to foster a sense of ‘stewardship’ rather than frustrating a desire for permanent ownership.

Furthermore, it is important to investigate the interplay and fit between stimuli. Future work could explore the extent to which exceptional service quality can compensate for a negative brand experience, or whether a “luxury” product stimulus requires a congruent “premium” service to be effective. To diversify methodological approaches and capture the lived experience, longitudinal and qualitative studies are urgently needed to answer questions about how consumers’ motivations evolve over a long-term subscription and what key trigger points lead to churn. The field must also critically examine the sustainability narrative of renting. This requires a challenging but essential question: under what conditions, such as user density or logistics efficiency, does fashion rental create a ‘sustainability paradox,’ resulting in a higher net environmental impact than other consumption modes?

Finally, there is a pressing need for diversifying samples and contexts beyond the dominant Western, female, and youth focus. Future research should explore how cultural values, like individualism versus collectivism, moderate the influence of key drivers in emerging markets, or what unique trust-building mechanisms differentiate successful Peer-to-Peer (P2P) platforms from centralized Business-to-Consumer (B2C) models. Pursuing these questions will be essential for developing a truly global and inclusive understanding of the fashion rental phenomenon.

8 Conclusion

This systematic literature review synthesizes the current state of research on consumer adoption of fashion rental, a key pillar of the emerging circular fashion economy. Our analysis of 68 articles reveals a rapidly growing field, rich with insights but lacking a unified theoretical structure. By applying the S–O–R framework, we developed an integrative model that organizes the key stimuli, organismic states, and behavioral responses, while also accounting for critical moderating factors. This framework not only brings coherence to a fragmented literature but also provides a robust foundation for future research and actionable insights for practitioners. Given that access-based consumption is expected to become more widespread, understanding the nuances of the consumer adoption journey is more critical than ever. Our study represents a significant step in this direction, offering a comprehensive map of the current landscape and a clear agenda for the road ahead.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MS: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. YX: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. AS: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. XY: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 20252BAC200296). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT (Version 4, OpenAI) to brainstorm for the research framework, refining the manuscript’s structure, polishing the language, and checking for compliance with the journal’s formatting guidelines. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbate, S., Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., Nadeem, S. P., and Riccio, E. (2023). Sustainability trends and gaps in the textile, apparel, and fashion industries [review of sustainability trends and gaps in the textile, apparel, and fashion industries]. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26:2837. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02887-2

Ahmed, B., El-Gohary, H., Khan, R., Gul, M. A., Hussain, A., and Shah, S. M. A. (2024). The influence of behavioral and ESG drivers on consumer intentions for online fashion renting: a pathway toward sustainable consumption in China’s fashion industry. Sustainability 16:9723. doi: 10.3390/su16229723

Armstrong, C. M., Niinimäki, K., Kujala, S., Karell, E., and Lang, C. (2014). Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 97:30. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.046

Armstrong, C. M., and Park, H. (2019). “Exploring Consumer Motivation for Apparel Renting: Insights from Interviews with Renters,” in International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings. Iowa State University Digital Press.

Arrigo, E. (2021a). Digital platforms in fashion rental: a business model analysis. J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 26, 1–20. doi: 10.1108/jfmm-03-2020-0044

Arrigo, E. (2021b). Collaborative consumption in the fashion industry: a systematic literature review and conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 325:129261. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129261

Aus, R., Moora, H., Vihma, M., Unt, R., Kiisa, M., and Kapur, S. (2021). Designing for circular fashion: integrating upcycling into conventional garment manufacturing processes. Fash. Text. 8:262. doi: 10.1186/s40691-021-00262-9

Baek, E., Park, E., and Oh, G. (2023). Understanding the relationship between the material self, belief in brand essence, and luxury fashion rental. J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 29, 1–19. doi: 10.1108/jfmm-06-2023-0149

Becker-Leifhold, C. (2018). The role of values in collaborative fashion consumption - a critical investigation through the lenses of the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 199, 781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.296

Bettiga, D., Yacout, O. M., and Noci, G. (2023). Editorial: emotions as key drivers of consumer behaviors: a multidisciplinary perspective. Front. Commun. 8:1158942. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1158942

Biyase, N., Mason, R. B., and Corbishley, K. M. (2023). Drivers and barriers of fast fashion implementation in south African retail. Available online at: https://marketing.expertjournals.com/ark:/16759/EJM_1115mason201-224.pdf (accessed April 23, 2023).

Bodenheimer, M., Schuler, J., and Wilkening, T. (2022). Drivers and barriers to fashion rental for everyday garments: an empirical analysis of a former fashion-rental company. Sustain Sci Pract Policy 18:344. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2022.2065774

Brand, S., Jacobs, B., and Taljaard, H. (2023). I rent, swap, or buy second-hand – comparing antecedents for online collaborative clothing consumption models. Int. J. Fashion Des. Technol. Educ. 16:275. doi: 10.1080/17543266.2023.2180541

Charnley, F., Knecht, F., Muenkel, H., Pletosu, D., Rickard, V., Sambonet, C., et al. (2022). Can digital technologies increase consumer acceptance of circular business models? The case of second hand fashion. Sustainability 14:4589. doi: 10.3390/su14084589

Chen, X., Memon, H. A., Wang, Y., Marriam, I., and Tebyetekerwa, M. (2021). Circular economy and sustainability of the clothing and textile industry. Mat. Circular Econ. 3:12. doi: 10.1007/s42824-021-00026-2

Chi, T., Adesanya, O., Liu, H., Anderson, R., and Zhao, Z. (2023a). Renting than buying apparel: U.S. consumer collaborative consumption for sustainability. Sustainability 15:4926. doi: 10.3390/su15064926

Chi, T. T., Gonzalez, V. R. A., Janke, J., Phan, M., and Wojdyla, W. (2023b). Unveiling the soaring trend of fashion rental services: a U.S. consumer perspective. Sustainability 15:4338. doi: 10.3390/su151914338

Choi, H. S., Oh, W., Kwak, C., Lee, J., and Lee, H. (2022). Effects of online crowds on self-disclosure behaviors in online reviews: a multidimensional examination. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 39:218. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2021.2023412

Clube, R. K. M., and Tennant, M. (2020). Exploring garment rental as a sustainable business model in the fashion industry: does contamination impact the consumption experience? J. Consum. Behav. 19, 359–370. doi: 10.1002/cb.1817

Das, M., Jebarajakirthy, C., and Achchuthan, S. (2022). How do consumption values and perceived brand authenticity inspire fashion mass market purchases? An investigation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 68:103023. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103023

Dovalienė, A., and Salciute, L. (2024). An investigation of circular fashion: antecedents of consumer willingness to rent clothes online. Sustainability 16:3862. doi: 10.3390/su16093862

Eroğlu, S., Machleit, K. A., and Davis, L. (2001). Atmospheric qualities of online retailing. J. Bus. Res. 54:177. doi: 10.1016/s0148-2963(99)00087-9

Ertz, M., and Leblanc-Proulx, S. (2018). Sustainability in the collaborative economy: a bibliometric analysis reveals emerging interest. J. Clean. Prod. 196, 1073–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.095

Fani, V., Pirola, F., Bindi, B., Bandinelli, R., and Pezzotta, G. (2022). Design product-service systems by using a hybrid approach: the fashion renting business model. Sustainability 14:5207. doi: 10.3390/su14095207

Feng, Y., Tan, Y., Duan, Y., and Bai, Y. (2020). Strategic analysis of a luxury fashion rental platform in the sharing economy. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 142:102065. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2020.102065

Fritze, M. P., Marchand, A., Eisingerich, A. B., and Benkenstein, M. (2020). Access-based services as substitutes for material possessions: the role of psychological ownership. J. Serv. Res. 23, 368–385. doi: 10.1177/1094670520907691

Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R., and Grechi, D. (2020). Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: a gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 12:2809. doi: 10.3390/su12072809

GlobalData (2024). Apparel rental market size, share, trend analysis, and forecasts to 2027. London: GlobalData.

Grilló-Méndez, A.-J., Navarro, M. M., and Iglesias, M. P. (2024). Risks associated by consumers with clothing rental: barriers to being adopted. J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 28:1135. doi: 10.1108/jfmm-02-2023-0043

Gumulya, D. (2020). The role of perceived enjoyment in people’s attitude to accept toy and equipment renting for children: a comparative study between people who have been using the service versus those who have never used the rental service. Manag. Sci. Lett. 10, 2119–2130. doi: 10.5267/J.MSL.2020.1.017

Gusenbauer, M., and Haddaway, N. (2019). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 11:181. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1378

Guzzetti, A., Crespi, R., and Belvedere, V. (2021). Please don’t buy! consumers' attitude to alternative luxury consumption. Strateg. Change 30:67. doi: 10.1002/jsc.2390

Helinski, C., and Schewe, G. (2022). The influence of consumer preferences and perceived benefits in the context of B2C fashion renting intentions of young women. Sustainability 14:9407. doi: 10.3390/su14159407

Hochreiter, V., Benedetto, C. A. D., and Loesch, M. (2023). The stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) paradigm as a guiding principle in environmental psychology: comparison of its usage in consumer behavior and organizational culture and leadership theory. J. Entre. Bus. Dev. 3:7. doi: 10.18775/jebd.31.5001

Hultberg, E., and Pal, R. (2021). Lessons on business model scalability for circular economy in the fashion retail value chain: towards a conceptual model. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 28:686. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.033

Hur, W., Kim, Y., and Park, K. (2012). Assessing the effects of perceived value and satisfaction on customer loyalty: A ‘green’ perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manage. 20, 146–156. doi: 10.1002/csr.1280

Huynh, P. H. (2021). Enabling circular business models in the fashion industry: the role of digital innovation. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 71:870. doi: 10.1108/ijppm-12-2020-0683

Jacoby, J. (2002). Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: an evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 12, 51–57. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1201_05

Jain, R., Jain, K., Behl, A., Pereira, V., Giudice, M. D., and Vrontis, D. (2021). Mainstreaming fashion rental consumption: a systematic and thematic review of literature. J. Bus. Res. 139:1525. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.071

Jain, S., and Mishra, S. (2020). Luxury fashion consumption in sharing economy: a study of Indian millennials. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 11:171. doi: 10.1080/20932685.2019.1709097

Jain, R., Singh, G., Jain, S., and Jain, K. (2023). Gen Xers: perceived barriers and motivators to fashion renting from the Indian cultural context. J. Consum. Behav. 22:1128. doi: 10.1002/cb.2189

Johnson, E., and Plepys, A. (2021). Product-service systems and sustainability: analysing the environmental impacts of rental clothing. Sustainability 13:2118. doi: 10.3390/su13042118

Kala, D., and Chaubey, D. S. (2024). Exploring the determinants of fashion clothing rental consumption among young Indians using the extended theory of reasoned action. Global Knowledge Mem. Commun. 22:501. doi: 10.1108/gkmc-12-2023-0501

Khitous, F., Urbinati, A., and Verleye, K. (2022). Product-service systems: a customer engagement perspective in the fashion industry. J. Clean. Prod. 336:130394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130394

Kim, N., and Jin, B. (2019). Why buy new when one can share? Exploring collaborative consumption motivations for consumer goods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 44, 122–130. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12551

Kim, N., and Jin, B. (2020). Addressing the contamination issue in collaborative consumption of fashion: does ownership type of shared goods matter? J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 25, 242–256. doi: 10.1108/jfmm-11-2019-0265

Kim-Vick, J., and Cho, E. (2024). Gen Z consumers’ intention to adopt online collaborative consumption of second-hand luxury fashion goods. J. Glob. Fashion Mark. 15, 440–458. doi: 10.1080/20932685.2024.2339230

Kucińska-Król, I., Festinger, N., Walawska, A., and Kulczycka, J. (2024). Study of Lodz society’s knowledge of the circular economy in the textile and clothing industry. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 32:10. doi: 10.2478/ftee-2024-0015

Lang, C. (2018). Perceived risks and enjoyment of access-based consumption: identifying barriers and motivations to fashion renting. Fash. Text. 5:139. doi: 10.1186/s40691-018-0139-z

Lang, C., and Armstrong, C. M. (2017). Collaborative consumption: the influence of fashion leadership, need for uniqueness, and materialism on female consumers’ adoption of clothing renting and swapping. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 13:37. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2017.11.005

Lang, C., and Armstrong, C. M. (2018). Fashion leadership and intention toward clothing product-service retail models. J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 22, 571–587. doi: 10.1108/jfmm-12-2017-0142

Lang, C., Seo, S., and Liu, C. (2019). Motivations and obstacles for fashion renting: a cross-cultural comparison. J. Fashion Mark. Manag. 23, 519–536. doi: 10.1108/jfmm-05-2019-0106

Lang, C., and Zhang, R. (2024). Motivators of circular fashion: the antecedents of Chinese consumers’ fashion renting intentions. Sustainability 16:2184. doi: 10.3390/su16052184

Lee, S., and Chow, P. (2019). Investigating consumer attitudes and intentions toward online fashion renting retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 52:101892. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101892

Lee, S. H., and Huang, R. (2020). Exploring the motives for online fashion renting: insights from social retailing to sustainability. Sustainability 12:7610. doi: 10.3390/SU12187610

Lee, S., and Huang, R. (2020b). Consumer responses to online fashion renting: exploring the role of cultural differences. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 49:187. doi: 10.1108/ijrdm-04-2020-0142

Lee, S. E., Jung, H. J., and Lee, K. (2021). Motivating collaborative consumption in fashion: consumer benefits, perceived risks, service trust, and usage intention of online fashion rental services. Sustainability 13:1804. doi: 10.3390/su13041804

Lee, H., Sakamoto, Y., and Yoshizawa, Y. (2022). Sustainable clothing consumption: an empirical analysis on purchasing quantities and clothing utilization. Int. J. Sustainability Policy Practice 18, 1–13. doi: 10.18848/2325-1166/cgp/v18i01/1-13

Levänen, J., Uusitalo, V., Härri, A., Kareinen, E., and Linnanen, L. (2021). Innovative recycling or extended use? Comparing the global warming potential of different ownership and end-of-life scenarios for textiles. Environ. Res. Lett. 16:054069. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/abfac3

Lichtenthal, J. D., and Goodwin, S. A. (2006). Product attributes for business markets: implications for selling and sales management. Psychol. Mark. 23, 225–251. doi: 10.1002/mar.20097

Lin, P., and Chen, W.-H. (2022). Factors that influence consumers’ sustainable apparel purchase intention: the moderating effect of generational cohorts. Sustainability 14:8950. doi: 10.3390/su14148950

Linder, N., Giusti, M., Samuelsson, K., and Barthel, S. (2021). Pro-environmental habits: an underexplored research agenda in sustainability science. Ambio 51, 546–556. doi: 10.1007/s13280-021-01619-6

Ly, B. (2021). Competitive advantage and internationalization of a circular economy model in apparel multinationals. Cogent Bus Manag 8:4012. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2021.1944012

Marth, S., Hartl, B., and Penz, E. (2022). Sharing on platforms: reducing perceived risk for peer-to-peer platform consumers through trust-building and regulation. J. Consum. Behav. 21, 1255–1267. doi: 10.1002/cb.2075

McCoy, L., Wang, Y.-T., and Chi, T. (2021). Why is collaborative apparel consumption gaining popularity? An empirical study of US gen Z consumers. Sustainability 13:8360. doi: 10.3390/su13158360