- 1Department of Sustainable Biomaterials, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, United States

- 2Department of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Lyngby, Denmark

- 3IIIEE, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Alternative Economic Models (AEMs) are theoretical frameworks that, if implemented, could fundamentally transform economic systems by aligning financial objectives with sustainability goals. Conducting rigorous research on future-oriented AEMs and other complex sustainability systems presents challenges, particularly due to the exploration of largely unverifiable future possibilities. Qualitative models can enhance the completeness, insights, and communications of such research. However, the absence of comprehensive guidelines for ensuring and assessing the quality of future-oriented qualitative models raises concerns about their reliability. The aim of this paper is to improve the quality of qualitative models used in future- and sustainability-focused AEM research by defining three key aspects of model quality: (1) scientific validity; (2) scientific usefulness; and (3) practical usefulness. Drawing on diverse fields, including futures studies, modeling methodologies, and the philosophy of science, we identify 11 Model Quality Considerations (MQCs). These MQCs are tested and refined through two AEM model case applications. We propose a framework for model developers and evaluators to understand their roles and the interactions among MQCs. Our analysis reveals that some MQCs are inherently incompatible, making it impractical to fully satisfy all considerations in a single model. Instead, developing high-quality models requires strategically prioritizing quality aspects, based on the model’s intended purpose. The paper concludes by outlining directions for future research.

1 Introduction

Alternative Economic Models (AEMs), such as Degrowth and the Circular Economy, have emerged in response to escalating concerns about environmental degradation and social inequality associated with prevailing growth-oriented paradigms (Hickel, 2021; Kirchherr et al., 2023). However, the broader sustainability transition often suffers from a disconnect between aspirational goals (e.g., what policymakers and the public envision for the future) versus concrete understandings of the practical measures needed to achieve such futures, including policy decisions and behavioral changes (Richert et al., 2017). To address this disconnect, researchers have sought to move beyond abstract ideals by developing more concrete notions of realized sustainable AEM futures (e.g., Calisto Friant et al., 2025; Zagonari, 2024; Voulvoulis, 2022). Such future-oriented knowledge offers valuable insights and guidance on complex and uncertain challenges, thereby supporting informed decision-making and the development of shared understandings (Section 2.1). In essence, a deeper grasp of potential futures and pathways toward sustainability facilitates a more dynamically consistent understanding of present actions required for transformative change—supporting the definition of goals and helps prevent the repetition of the shortcomings inherent in the current unsustainable economic model (Bell, 2017; Richert et al., 2017; Quist, 2016; Raudsepp-Hearne et al., 2020). To accomplish this, it is essential to strengthen foresight capacities—referring to the quality of foresights—to better capture and evaluate sustainability-oriented AEMs in their realized forms, such as a Circular Economy (Weigend Rodríguez et al., 2020).

When evaluating AEMs, it is crucial to adopt a broader systemic perspective to ensure that they can produce genuinely environmental, economic, and social sustainability outcomes (Hassan and Faggian, 2023). Qualitative models play a crucial role in this context, as they can capture the complexity of ideas and systems, making the underlying propositions of AEMs more accessible for study and communication (Hanger-Kopp et al., 2024; van Gigch, 1991, p. 176; Moon and Browne, 2021; Checkland, 1995). This capacity likely explains their widespread use and significant influence on both policy and research (e.g., Cairney, 2020).

In this paper, qualitative “model” is broadly defined as encompassing all graphic depictions, including frameworks and diagrams, which have different purposes (e.g., to frame the research process vs. illustrate findings) and characteristics (i.e., capturing only structure vs. structure and relations) (Varpio et al., 2020; Partelow, 2023; McLean and Shepherd, 1976). Common across these models is their capacity to, through simplification and abstraction (Section 2.2), replace the need for large extents of text that would otherwise be required to communicate the information conveyed in the model (Wilson, 1984, p. 10). In addition, the use of qualitative models, primarily for grounding the research, have the ability to: (1) open up the study for inspection of the research process and assumptions made (i.e., increase transparency objectivity), and; (2) increase the accuracy or completeness (i.e., internal validity) of the results (Sale and Carlin, 2025; Gbededo and Liyanage, 2020; Gray, 2018). As such, qualitative models have the capacity to improve the quality of future-oriented AEM research, hence strengthen foresight capacity.

Qualitative models are common in future-oriented sustainability [e.g., the three pillars of sustainability (Purvis et al., 2019)] and AEM research, such as the “Doughnut Economy” (Raworth, 2017)—which we refer to as future-oriented AEM qualitative models (Fo-AEM-QM). These models largely consist of propositions that are yet—or never—to be realized. As such, the claims of “truth” of these models make validation challenging; while some Fo-AEM-QMs are applied to contemporary contexts (e.g., Bocken et al., 2016) as a form of validation, such applications only prove that the model may be useful in the current state, not that it is a valid (e.g., complete and correct) representation of a “nonexistent and nonevidential” (Bell, 2017, p. 191) future realized state of the AEM.

The quality of these models is crucial (see Bell, 2017, pp. 191ff) to avoid compromising “the integrity of science by misusing unvalidated models” (Scholz and Wellmer, 2021, p. 2069; see also Giannetti et al., 2021). However, concrete, comprehensive quality guidelines (e.g., criteria for validity and usefulness) applicable to Fo-AEM-QM models are currently missing.

This quality gap is particularly concerning given the potential influence of Fo-AEM-QMs on contemporary decision-makers and research discourses (e.g., Biermann et al., 2022). Consequently, while Fo-AEM-QM can strengthen research on future-oriented or conceptual AEMs, these models lack explicit considerations for quality. To remedy this, quality assurances relevant for qualitative future-oriented models are needed, which can be achieved by incorporating guidance from different methods, e.g., Futures Studies “as a complementary discipline” (Weigend Rodríguez et al., 2020, p. 529) into the AEM in question to strengthen its foresight capacity. No single set of existing quality considerations is deemed sufficient on its own (see Section 4.1 for the literature review).

This paper aims to advance the quality, and thereby the use, of qualitative models in future- and sustainability-oriented AEM research by providing guidance to model developers and evaluators alike. Thus, the research question consists of defining what “quality” means for Future-oriented Alternative Economic Models Qualitative Models (Fo-AEM-QM). To accomplish this, we first define Fo-AEM-QM quality as consisting of three aspects (i.e., scientific usefulness, practical usefulness, and scientific validity), a concept used to identify eleven (11) model quality considerations (MQCs). Based on these, a Practical MQC Framework is proposed, offering a comprehensive view of how the MQCs interact and what Fo-AEM-QM quality entail for model developers versus evaluators/users. The MQCs and the Framework are the main outcome of a deductive theory-building process, based on: (1) a range of fields and approaches addressing qualitative modeling and model quality, such as soft systems modeling and interdisciplinary research methods; and (2) two case applications (Section 3).

This paper starts by clarifying the importance of future-oriented knowledge, the role of qualitative models in AEM research, and elaborates on fundamental considerations for model quality in qualitative models (Section 2) and then devises a research approach for designing the MQCs (Section 3). The resulting literature review findings are presented (Section 4.1), along with the case application results and the 11 MQCs (Section 4.2). Next, we propose a practical framework on the interrelations between the MQCs and the different implications for model developers versus evaluators/users (Section 5.1). We discuss what the findings mean for Fo-AEM-QM quality (Section 5.2) and conclude with a future outlook (Section 6).

2 Background

First, we explain the characteristics of future-oriented knowledge and how it contrasts with other temporal research approaches (Section 2.1). Next, we examine the nature, development process, and quality challenges associated with qualitative models (Section 2.2).

2.1 On future-oriented knowledge

Studies of AEMs can be divided into five categories: (1) the inevitability of, and need for, making changes related to a particular AEM, based on contemporary challenges related to the economic system (see Klitgaard and Krall, 2012 on the AEM Degrowth); (2) investigations into the current state and identification of barriers and enablers (see, e.g., Camacho-Otero et al., 2019 on user acceptance of Circular Economy consumption practices); (3) investigations into past and contemporary examples to demonstrate viability of the particular AEM (see Kallis et al., 2012 on Degrowth); (4) the formulation of critique of a particular AEM proposition (see, e.g., Corvellec et al., 2022 on the weaknesses in the Circular Economy), and; (5) theoretical or conceptual investigations into what defines the economic model (Morseletto, 2022), and what it might entail in its implemented form (e.g., Degrowth scenarios Svenfelt et al., 2019; Otero et al., 2024; see also Calisto Friant et al., 2025).

Studies pertaining to categories 4 and 5 are purely theoretical, or conceptual, investigations into a future, realized state of an AEM (i.e., fully implemented and normalized)—they are what is referred to in this paper as “future-oriented.” This type of research—along with any type of Futures Studies—cannot make use of empirical observation to test and validate the findings; there are no “truths” or “facts” to discover about a future-oriented AEM, only various forms of possibilities or probabilities to identify, explore, and evaluate (Bell, 2017, p. 148ff). Possibilities in Futures Studies are likened to “dispositionals,” such as the breaking of a glass, were it to be dropped; “The fact that it could be broken remains a real present possibility for its future” (Bell, 2017, p. 76). As such, possibilities are important to identify and plan for to offer relevant guidance to contemporary decision-makers on the issue at hand (Chugh, 2021; Schwarz et al., 1982, p. 6; Wilkinson, 2017; Ramirez et al., 2015). To this end, Futures Studies knowledge is sometimes referred to as “knowledge surrogates” due to its capacity to: “… substitute for the unattainable knowledge of the future that is needed for competent and intelligent action” (Bell, 2017, p. 226). Given how such images of the future are known to impact actors’ aspirational decisions and actions today (Bell, 2017, pp. 84, 142ff), they must be of high quality.

2.2 On models, modeling and quality of qualitative models

While AEMs can constitute a form of theory or concept in that it seeks to explain how an economic system might work under alternative principles, a model seeks to represent the AEM (Bhattacherjee, 2012). As such, qualitative modeling is a process of conceptualization, consisting of simplification or abstractions through which complexity may be “‘hidden from view’, but not eliminated (van Gigch, 1991, pp. 3, 19). In this sense, higher-level abstraction constitutes “aggregated complexity” (van Gigch, 1991, p. 241). The object of study, such as a certain system or part thereof, constitutes an abstract construct (e.g., the “Doughnut Economy”; Raworth, 2017) that is specified into more clearly defined concepts that permit it to be studied by focusing on key system variables, aspects or elements (e.g., actors) and relations, rather than the whole system (Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 12ff; Sale and Carlin, 2025; van Gigch, 1991; Checkland and Poulter, 2006; LeFebvre, 2017). As such, “abstraction” often consists of the “… choice to conceptualize something in a specific way” (Cornelissen et al., 2021, p. 4). To this end, modeling involves the development of artificial replications of the system under study, such that it functions as a “stand-in” for the study (Grüne-Yanoff, 2009) through the use of assumptions as experimental controls (Mäki, 2005). Due to these limiting assumptions and concepts (i.e., abstraction and simplification), a conceptual model is not “a description of what exists,” but “a view of what exists” (Wilson, 1984 p. 31), or put into other words; the model is not of X but “relevant to debate about” X (Checkland, 1995, p. 47); the model has become “a new reality” (Bell, 2017, p. 215) more amenable to being studied. To this end, the use of models comes with the risk of oversimplifying the issue and limiting the research endeavor, hence, caution and reassessment of the model throughout the research process are necessary (Sale and Carlin, 2025).

The use of qualitative models can present a struggle regarding transparency, both in terms of their development and what constitute suitable applications (Partelow, 2023). Moreover, guidance on what makes qualitative models “good” is scattered (Jakeman et al., 2006; Sale and Carlin, 2025). This is not unique to modeling; in qualitative research overall, there is a lack of a commonly agreed upon definition of scientific validity (Gray, 2018; Rolfe, 2006; Lincoln and Guba, 1986). In addition, the unique characteristics of a system model—which an AEM model inevitably is—put into question the scientific demands on exactness, neutrality, and objectivity of the model; to this effect, social sciences at large, and system modelers in particular, must develop their own “yardstick for rigor” (van Gigch, 1991, p. 12f) or “strategies of acceptance”—referring to ways to ensure and assess the quality of qualitative models (see Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 24).

System modelers are often proponents of “rigorous testing” of the model’s accuracy and usefulness (see, e.g., Jakeman et al., 2006; van Gigch, 1991). In the case of Fo-AEM-QMs this may be done externally (van Gigch, 1991; Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 24), e.g., by using expert interviews or a Delphi study. Such practices can be used to gauge the extent to which the model fulfills its purpose (Gbededo and Liyanage, 2020) and is deemed credible (Grüne-Yanoff, 2009, p. 95). A model’s value can also be demonstrated by it being utilized or applied to a specific purpose (Ling and Leng, 2018), such as to develop scenarios (e.g., Svensson-Hoglund et al., 2022). However, the objectives, content, and methods for such testing, particularly for Fo-AEM-QMs, are currently missing in the literature, which reinforces the need for further exploration.

3 Methods

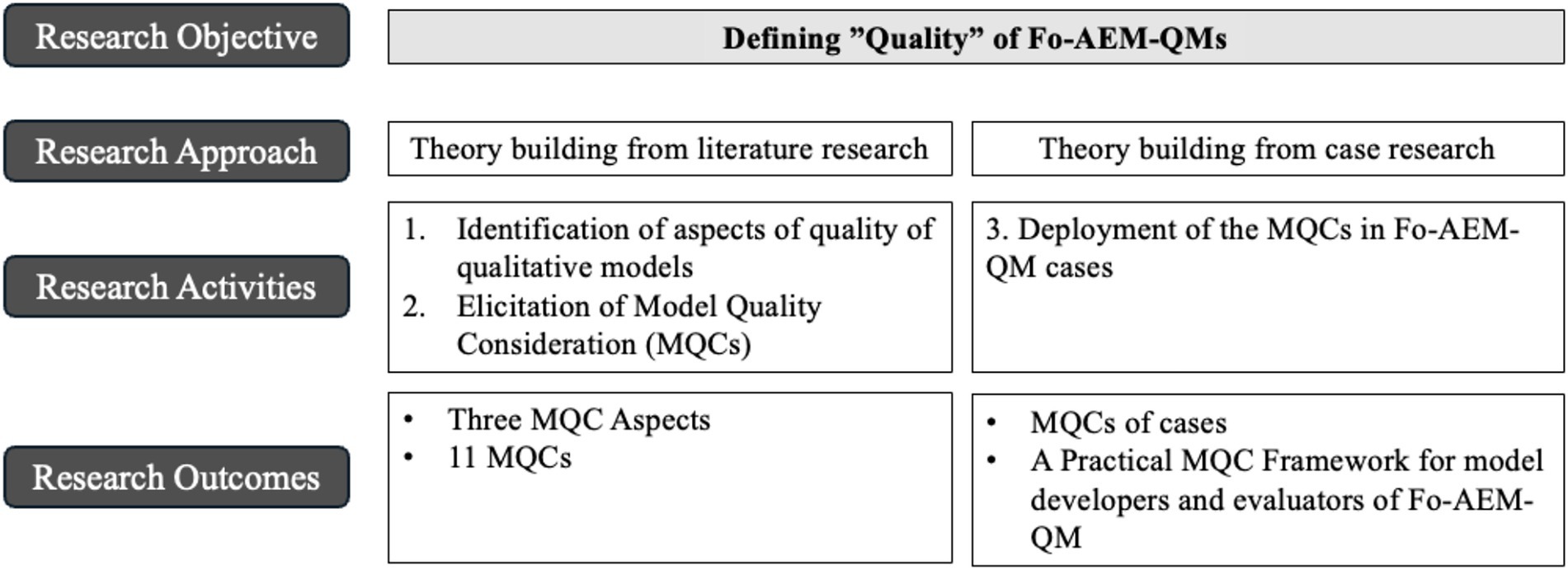

This research follows a deductive theory building approach consisting of three research activities (Figure 1). Starting with the development of a general lens to Fo-AEM QM quality (Section 3.1) used to conduct the literature review (Section 3.2), the findings were tested in two case applications (Section 3.3).

3.1 Three aspects of model quality: a conceptual framework

The quality of a Fo-AEM-QM adheres to its claims on what the modeled AEM may possibly entail in its realized state. A Fo-AEM-QM can show such possible outcomes regarding: (1) the selected system aspect (e.g., system boundaries); (2) based on the premises and assumptions (e.g., of actor rationality) of the modeling, and; (3) the selected components and relations (e.g., actors, settings or more abstract) (see van Gigch, 1991; Ling and Leng, 2018; Checkland and Poulter, 2006; Grüne-Yanoff, 2009; Mäki, 2005). As such, the claims of “truth” that a Fo-AEM-QM may make relate to possibilities, applicable only within the boundaries of the model parameters (i.e., the abstraction of complexity; van Gigch, 1991), which we refer to as “conditioned possibilities” of the AEM, such as “a CE may be X, assuming Y and Z.” This claim is what the quality assurance and evaluation centers on.

Relevant aspects of model’s quality include the scientific validity (i.e., degree of accuracy), scientific usefulness (i.e., novelty and knowledge-enhancement), and practical usefulness (i.e., for contemporary decision-makers, such as policymakers or practitioners) (Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020; Gray, 2018; Miles et al., 2014; Repko and Szostak, 2021; Figure 2).

Figure 2. A framework of three aspects of Fo-AEM-QM quality, consisting of scientific validity, and scientific usefulness and practical usefulness (adapted from Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020; Miles et al., 2014; Gray, 2018; Repko and Szostak, 2021).

3.2 A selected literature review for identifying model quality considerations

To populate the three aspects of model quality (Figure 2) with Model Quality Considerations (MQCs), and, as such, develop a “yardstick” (van Gigch, 1991) of Fo-AEM-QM quality, we built upon a range of disciplines and schools of thought. On their own, these sources and traditions do not offer adequate guidance on how to ensure or assess Fo-AEM-QM quality; together, however, they provide more comprehensive guidance. General research methods were used to create a solid foundation (e.g., Miles et al., 2014), along with interdisciplinary research methods (Repko and Szostak, 2021), given the oftentimes interdisciplinary nature of AEM research (e.g., sociology, economics and environmental impact). In addition, literature on a range of qualitative modeling methods was reviewed for applicable MQCs. The literature was selected and reviewed considering conditioned possibilities (Section 3.1). Also, for specific guidance on how to consider the quality of future-oriented models, we consulted principles of Futures Studies (e.g., Bell, 2017) and philosophy of science (e.g., Fumagalli, 2016).

3.3 Case application

To test the resulting MQCs, we applied them to two existing Fo-AEM-QM: the “Butterfly Diagram” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013a); and Bocken et al.’s (2016) “Framework of Linear and Circular Approaches for Reducing Resource Use”—both depicting the AEM of a “Circular Economy” (CE). The Butterfly Diagram (at the time titled: “The Circular Economy”) was introduced in volume 1 in a series of 3 reports. The model is used in all three reports (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013a, 2013b, 2014). However, only volume 1 is referenced in the case application (Section 4.2) as no additional details relevant to the model quality could be identified in the other two volumes.

These two models were selected due to being highly influential on the CE concept (Velenturf et al., 2019), and distinctly different; while Bocken et al. (2016) introduces a theoretical vocabulary for how a CE works, the Ellen Macarthur Foundation (EMF) model (2013a) depicts a CE system in terms of how products and resources flow and who/what is involved. As such, these two models provide a distinct comparative testing ground for the MQCs.

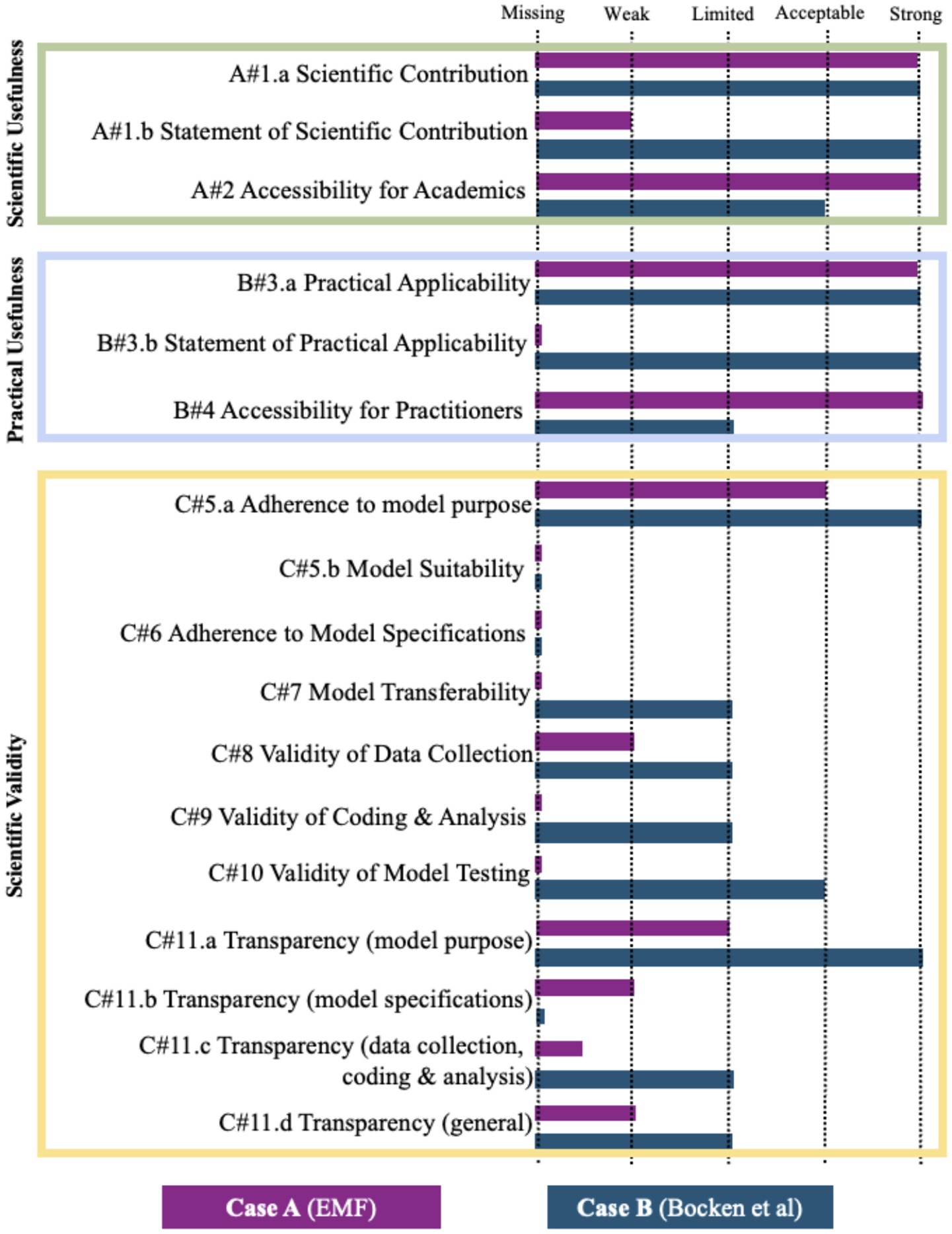

Both models were evaluated based on their performance against the MQCs, using categories of “missing,” “weak,” “limited,” “acceptable” or “strong” performance.

The findings of this paper are limited to the three aspects of quality (Figure 2), which could have been more granularly defined, such as by splitting accuracy and transparency. However, for their interrelated relationship, see Section 5. Also, different case studies may have produced different refinement of the 11 MQCs, which is why we, in Section 6, encourage future research involving further testing of the considerations to ensure relevance.

4 Results

4.1 Considerations for quality in the literature

In this section, the findings from the review on the three aspects of quality (Figure 2) are presented: scientific usefulness (Section 4.1.1), practical usefulness (Section 4.1.2), and scientific validity (Section 4.1.3).

4.1.1 Scientific usefulness considerations

Scientific usefulness refers to scientific (i.e., theoretical or conceptual) understanding and expansion of knowledge, while practical usefulness (Section 4.1.2) entails guidance on how to address a particular issue (i.e., applicability) (see Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 24). These two quality aspects (Figure 2) overlap in how they relate to whether the research: “…provides some useful way of describing or coping with the world…” (Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 24)—referred to as “adequacy” in Futures Studies (Schwarz et al., 1982, p. 6), “progress” in general method studies (Nicholson et al., 2018), and model “relevance” in Soft System Methodology (Checkland, 1995).

We propose that there are two sides to scientific usefulness—the (novel) contribution and its accessibility. First, as to the contribution, it should be knowledge-enhancing or novel, which entails novel connections between multiple key concepts of the AEM (see Morgan, 2018; Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020). For this, model developers must specify the learnings that can be derived from the model and under what conditions those apply (Fumagalli, 2016)—the “conditioned possibilities” (Section 3.1). Such explicitness is aligned with Fawcett’s (2005) criteria of “significance,” meaning that it must be made clear what it is that the model adds to the current AEM understanding or theory. To this end, the modeler needs to position the contribution in existing research, e.g., by conducting a sufficient literature review or grounding of the model in existing work. This overlaps with “validity” (Section 4.1.3) in terms of correctness of the model (i.e., not having overlooked existing knowledge).

Scientifically useful research, unlike practically useful, can consist of a theoretical or conceptual thought experiment or theory exploration, such as envisioning what a realized AEM entails (e.g., Svenfelt et al., 2019), with little to no explicit guidance for decision-makers today on how to approach the AEM transition (see Repko and Szostak, 2021, p. 367ff). To this end, while abstract ideas and patterns can be knowledge-enhancing, practitioners require more concrete applicability (Cornelissen et al., 2021).

The second aspect of scientific usefulness is scientific accessibility, or ease of use of the model primarily for other academics as model users (e.g., the degree of time and effort needed for the model to be understandable) (see Gbededo and Liyanage, 2020). “Parsimony” or “conciseness” refers to the inclusion of as few concepts as possible to achieve the model’s purpose, since overly complicated models might obscure the results and thereby dilute the learnings (Fawcett, 2005). To this end, scientific accessibility requires of the modeler to only include concepts and relations needed to fulfill the model’s purpose (Fawcett, 2005) (i.e., overlapping with model relevance as part of model validity, see 4.1.3). Also, scientific accessibility can also depend on the availability of resources and explanations for understanding the model (see Gbededo and Liyanage, 2020; Fawcett, 2005), such as a glossary. Scientific accessibility expectations depend on the model’s audience, which might vary, i.e., consisting of a smaller group of interdisciplinary experts versus a wider, interdisciplinary community, who will require different levels of explanations.

4.1.2 Practical usefulness considerations

Practical usefulness emphasizes the degree of applicability and practical guidance offered by the model to inform contemporary AEM transition or implementation activities (see Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 24; Checkland, 1995 on model “relevance”), such as clarifying possible and desirable futures to a (particular) audience, inviting them to reflect on those futures to get short-term insight, and potentially modifying practitioners’ short and long-term behavior in ways that enable achievement of that desirable future (Bell, 2017, pp. 84, 142ff). Such “pragmatic adequacy” (Fawcett, 2005), “effectiveness” or clarity of the model is increased through the explicit outline of practical implications, such as recommendations, based on the model findings, for specific contemporary stakeholders. Relevance for the current state can also apply to academics researching this issue (i.e., non-future-oriented aspects of the AEM), such as the AEM’s implication for business models and product design (Bocken et al., 2016) and can therefore overlap with scientific usefulness (Section 4.1.1).

Another aspect of practical usefulness is the degree of practical accessibility of the model, such as the extent to which practitioners must possess specific knowledge or skills, go through training and/or access to specialized resources before they can effectively interact with the model (Gbededo and Liyanage, 2020; Fawcett, 2005). The practical accessibility expectation entails refraining from being overly abstract or theoretical and instead spelling out any practical implications for different audiences. To this end, ensuring practical accessibility likely varies between audiences, such as academics in the application space (e.g., business models) vs. practitioners in a narrower space, such as product design.

4.1.3 Scientific validity considerations

Scientific validity relates to “the question of the goodness—the quality…” (Miles et al., 2014, p. 276); the higher the validity, the stronger the scientific claim (Miles et al., 2014, p. 300). A distinction can be made between scientific usefulness (Section 4.1.1) and validity in that research can be scientifically valid without furthering the state of knowledge about an AEM (i.e., not being novel). However, invalid research cannot expand upon the existing body of knowledge.

In understanding the validity of conditioned possibilities (Section 3.1) in Fo-AEM-QMs, we focus on: (1) internal validity (i.e., the accuracy of the results) (Section 4.1.3.1); (2) objectivity (i.e., transparency) (Section 4.1.3.2), and; (3) external validity (i.e., generalizability) (Section 4.1.3.3) (Gray, 2018).

4.1.3.1 Internal validity

Internal validity relates to the ability of the method to produce findings in accordance with the model’s purpose, that are accurate and/or representative of the AEM (Thomas and Magilvy, 2011; Gray, 2018, p. 153). As such, the model must be credible (see Lincoln and Guba, 1986) and fulfill its purpose (e.g., as stated in the research question); “In the absolute, a model is neither true nor false, but simply more or less well-suited to a given set of questions” (David, 2001 p. 463). This pertains to model relevance (Checkland, 1995).

In Futures Studies, imagination and creativity are strongly encouraged to facilitate breaking away from contemporary perspectives (Corazza, 2024): “lt involves not only asking what is, but also asking what could be” (Bell, 2017, p. 76). The strength of the possibility depicted by the model (i.e., that it is “presumptively” true) is done by testing the logic of the model (see Bell, 2017, p. 150). In this context, model “correctness” (Gbededo and Liyanage, 2020) can be defined as “internal consistency,” meaning that the model and its elements are congruent and consistent (i.e., logical) (Fawcett, 2005; van Gigch, 1991). Given the conditioned possibilities in a Fo-AEM-QM for a state not realized, such logic assessment can be challenging. However, the qualification of the model to make valid inferences about an AEM relies upon the “conditional credibility judgments” of the audience interacting with the model (i.e., model users and evaluators) (Grüne-Yanoff, 2009, p. 95). Such judgements are based on adherence to stipulated assumptions, theories, and other models that are used, making the model “believable” (or not), e.g., in the ways that a fictional narrative may make sense, based on the premises of the story (Grüne-Yanoff, 2009, p. 95). This sentiment is echoed by Miles et al. (2014, p. 313) on qualitative research in general: “The account rings true, makes sense, seems convincing or plausible and enables a vicarious presence for the reader.” Also, van Gigch (1991) refers to the logic of the model as a subjective impression. As such, a model is credible given that it corresponds to its “theoretical hypothesis” (Grüne-Yanoff, 2009, p. 98) or the “additional information or presuppositions “(Fumagalli, 2016, p. 434), also referred to as the model specifications (Mäki, 2005). The level of adherence to the specifications upon which a model is built is referred to as model defensibility (Checkland, 1995 p. 47, 52f).

Model quality is also an outcome of the quality of the modeling process, referring to the gathering of data used to populate the model (i.e., data collection), the quality of analysis (e.g., coding), and the model testing or application (Ling and Leng, 2018; Gray, 2018, p. 181ff). This requires transparency (objectivity; Section 4.1.3.2), and as such, the line between assessing the modeling process vs. the product (i.e., the model itself) is not always clear (Jakeman et al., 2006). Data gathering in Futures Studies often involve transdisciplinary actors engaging in so-called “participatory foresight” (i.e., involvement of a range of actors in the futuring exercise). This interactive approach is fundamental for mitigating blind spots, which contributes to increased accuracy and/or completeness of the results (Nikolova, 2014; Bell, 2017, p. 155).

4.1.3.2 Objectivity

Traditionally, the expectation of objectivity entails the absence of influence by the researcher to separate out any elements of subjectivity, requiring both transparency and replicability of the method (Gray, 2018, p. 182, 185f). Further, there must be some “corresponding external representation” that can be assessed, and even repeated, by others (Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 27). Regarding replicability and developing a replicable methodology, Thomas and Magilvy (2011, p. 151) find that “qualitative rigor” constitutes: “… an oxymoron, considering that qualitative research [in general] is a journey of exploration and discovery that does not lend to stiff boundaries.” Instead, to meet the demands of objectivity, researchers engaged in qualitative modeling may focus on presenting the methodology in a way that lends itself to “inspection” or “confirmability” rather than replication (Gray, 2018 p. 182; Lincoln and Guba, 1986 p. 76f.). This is similar to an interpretivist view of validity, which entails the provision of: (1) clear explanations of the ways in which the data has been interpreted (i.e., data collection, coding and analysis), and; (2) access to the raw data in some form, such as using quotes (e.g., Rice and Ezzy, 1999). To this end, biases are unavoidable and must be explicitly stated (Miles et al., 2014, p. 311), particularly with regards to the model specifications (Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 27f).

Objectivity can also be achieved by sharing rival conclusions and assessing their plausibility (Miles et al., 2014, p. 312). To this end, objectivity may be tested by assessing implicit (i.e., non-disclosed) biases and value-laden assumptions through internal review (van Gigch, 1991), as well as through external expert consultation. Also, in Futures Studies, it is important to disclose any uncertainties about the future state and the assumptions that were made to accommodate said uncertainties (Rinaldi, 2023; Bell, 2017, p. 148ff).

In all, objectivity relates to the ability to assess elements of subjectivity in the model and, as such, the ability to assess the model development process, e.g., for the choices and assumptions made (i.e., model specifications). Achieving the necessary transparency requires: (1) a gradual (i.e., step-by-step) model development, with clearly defined activities, assumptions and outcomes at each step, and; (2) the research process documentation, which must be transparent to enable “inspection” of choices and assumptions (Gray, 2018, p. 182; van Gigch, 1991, p. 92), both of which allow for assessment of accuracy or credibility (i.e., internal validity; Section 4.1.3.1).

4.1.3.3 External validity

External validity concerns the applicability or transferability to contexts beyond the modeled one. However, it is the nature of qualitative research in general, and models in particular, to be “context-bound” (Lincoln and Guba, 1986, p. 75; Gray, 2018, p. 185). The model has, after all, been developed for a particular purpose (see above on model “relevance” and “defensibility”; Checkland, 1995). Accordingly, the external validity of a model pertaining to a specific AEM arguably consists of its degree of transferability to other parts/aspects of the AEM (e.g., normalized sharing vs. repair in a CE), and the transferability of findings to other AEMs (e.g., normalized sharing in a CE vs. a Doughnut Economy). As such, the demonstration of external validity consists of examples of other suitable applications of the model (i.e., transferability) outside the model purpose (see Jakeman et al., 2006; van Gigch, 1991; Botha, 1989; Lincoln and Guba, 1986).

Overall, the test of scientific validity will depend on the precise discipline(s), or more specifically, the ontology under which a Fo-AEM-QM has been developed (e.g., sociology vs. economics). On this note, from a Future Studies perspective, a model can be considered “justified” if it is not deemed false or illogical, making it “worthy of belief” (Bell, 2017 p. 210f). According to this perspective, assuring model validity consist of formulating considerations capable of disqualifying a model.

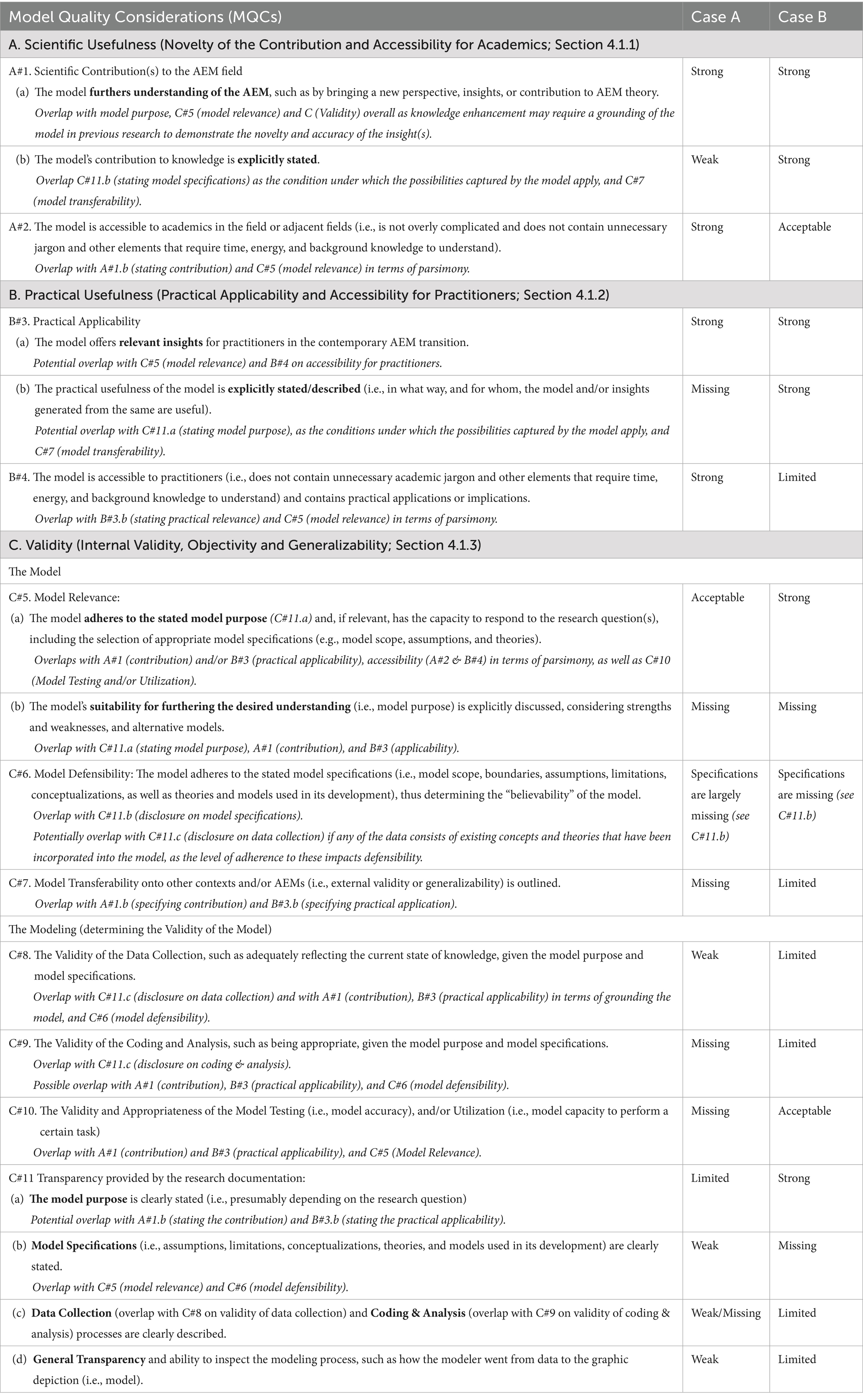

This literature review is synthesized into the resulting 11 MQCs (Table 1).

Table 1. The result of model applications for the “Butterfly Diagram” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013a) (Case A), and “Linear and Circular Approaches for Reducing Resource Use” (Bocken et al., 2016) (Case B).

4.2 Case applications of the MQCs

The case study results are presented below in Table 1, together with the refined MQCs in Column 1. The MQCs are numbered #1–11, with the letter of the quality aspect they pertain to (i.e., A—Scientific Usefulness, B—Practical Usefulness, and C—Scientific Validity). References across MQCs (i.e., overlaps) are denoted in italic.

The performance assessment of the case models included model content (i.e., visual depiction), as well as manuscript text.

The two case applications (Table 1) performed rather differently across the MQCs (Figure 3), speaking to their differing natures and purposes.

See Appendix A for detailed case application results, including motivations for model performance assessment, and an outline of the resulting refinements to the MQCs (Column 1; Table 1) following the case applications.

5 Discussion

In this section we propose a framework on the interrelations between the MQCs and their different implications for model developers versus evaluators/users (Section 5.1). Next, we discuss what the findings mean for Fo-AEM-QM quality (Section 5.2).

5.1 Proposition of a MQC framework for Fo-AEM-QM

The MQC Framework for Fo-AEM-QM developers and evaluators/users (Figure 4) capture the interrelations between the MQCs (Table 1), and the different implications for model developers versus evaluators/users.

The 11 MQCs (Table 1) are categorized into two overarching types: Information MQCs and Performance MQCs (left hand side; Figure 4).

Information MQCs pertain to the disclosure and communication of information within the model or accompanying text. They are divided into “transparency,” which involves revealing the modeling process (e.g., data collection methods; C#11.c), and “explicitness,” which concerns clearly communicating the model’s qualities (e.g., statements about the model’s knowledge contribution; A#1.b). For model developers, these MQCs imply that they must provide this information (i.e., meet the information MQCs). Model evaluators/users, on the other hand, verify its presence in the model and manuscript.

Performance MQCs address actual outcomes of the model or modeling process, such as the validity of the data and analysis (C#8 and C#9) and accessibility of the model to practitioners (B#4). While related, Information and Performance MQCs serve distinct roles; for example, transparency with regards to the data collection process (C#11.c) may be high, while the validity of that data (C#8) is low. Similarly, a well-articulated knowledge contribution statement (A#1.b) (i.e., high explicitness) might contain overstatements of the model’s actual impact (A#1.a). This interplay illustrates the synergy between objectivity (i.e., information MQCs) and internal validity (i.e., some of the performance MQCs), discussed in Section 4.1.3.

To understand the implications for model developers and evaluators/users in the context of performance MQCs, we organize the performance MQCs on a spectrum from “basic” to “complex,” based on technical difficulty, measurability, and the need for subject-matter expertise, and interconnections of the MQCs (Figure 4). Technical validity criteria tend to be clearer and more objective in their measurement, while elements, such as knowledge contribution and model accessibility, demand nuanced, qualitative judgment. Also, more basic MQCs (e.g., the validity of the data collection) typically requires general research skills, whereas complex MQCs (e.g., assessing knowledge impact) often necessitate deeper subject-matter expertise. This may include familiarity with the model type (e.g., dynamic systems modeling; de Gooyert et al., 2024), the AEM, and its domain (e.g., governance or lifestyles). Also, the employment of complex and/or less well-known modeling methods (e.g., to test the model) may also increase the complexity of a MQC. Also, interdependencies between MQCs amplify complexity, such as how achieving knowledge contribution (A#1.a) depends on validity and transparency criteria (C#5–11). Thus, success in one MQC may rely on others—complicating quality assurance.

Blended Performance MQCs (Figure 4) contain both basic and complex elements. For example, validity and appropriateness of model testing (C#10) comprise general methodological components and specialized subject-matter considerations (e.g., practitioner involvement), all of which vary in complexity. Some MQCs (e.g., adherence to model purpose; C#5.a) critically depend on corresponding transparency MQCs (statement on model purpose; C#6).

Depending on their position along the complexity span, performance MQCs demand varying effort from model developers to deliver and evaluators to ascertain. More basic MQCs (e.g., valid data analysis; C#9), require developers to ensure outcomes and evaluators to assess results, based on provided research documentation and standard research principles. More complex MQCs (e.g., model applicability; B#3) necessitate developers’ higher achievement efforts and evaluators’ estimations in the form of demanding judgments and interpretations.

The relative complexity of each performance MQC is indicated in Figure 4, though this placement is context-dependent. Well-documented modeling processes (C#11.d) facilitate quality evaluations, while insufficient information provisioning increases complexity, hence shift validity MQCs toward increased estimation effort. Explicitness MQCs support model evaluators or users in making informed estimations; for example, explicit statements about a model’s knowledge contribution (A#1.b) assist model evaluators and users in estimating its novelty (A#1.a). Nevertheless, these claims require critical evaluation rather than acceptance at face value, hence they remain rather complex. Consequently, the degree to which model developers adhere to transparency and explicitness MQCs can either simplify or complicate model evaluators’/users’ evaluation of their performance MQC counterparts. Also, the inclusion of any needed background information (e.g., on the aspect of the AEM being modeled), or at least references to the same, may boost the subject-matter knowledge of the model evaluator, and shift the MQC towards the left (Figure 4).

While insufficient adherence to information MQCs may deter accessibility (A#2 and B#4) by increasing user effort and required expertise, excessive provision of information may overwhelm evaluators with superfluous information, thus decrease accessibility. To balance accessibility and the provision of information, it may be worthwhile to only include model-relevant information in the manuscript (i.e., explicitness MQCs) and put documentation related to transparency MQCs (i.e., the modeling process) in a supplementary material. Also, the MQCs may need to be prioritized based on the specific model purpose, thus the quality profile of the model (see Section 5.2 for more on this).

In summary, the Framework’s (Figure 4) categorization of MQCs into information and performance, and the organization of the performance MQCs on a complexity spectrum, clarifies how information MQCs support their performance counterparts; transparency MQCs support more basic performance MQCs, while explicitness MQCs support the more complex MQCs. The Framework also clarifies the implications of the 11 MQCs for model developers (i.e., to provide quality-related information and ensure versus achieve model quality outcomes) and evaluators/users (i.e., to verify the presence of quality information and assess versus estimate model quality outcomes). The Framework particularly emphasizes the role that model developers play in model evaluators’/users’ evaluation, and points at some of the trade-offs and priorities model developers may consider. We discuss this more in Section 5.2.

5.2 The meaning of model quality for Fo-AEM-QMs

To understand what might constitute relevant MQCs for a Fo-AEM-QM, it is helpful to consider the intersections between the three aspects of model quality and the model’s contribution(s) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A framework of three aspects of Fo-AEM-QM quality, considering the intersections between the aspects and various combinations of quality emphasis within the triangle.

Each of the intersections—or bridging spaces—in which the three model quality aspects are combined constitute different “quality profiles” of Fo-AEM-QMs (Figure 5), depending on the model purpose. These zones consist of possible methodological synergies, as well as tension, that must be intentionally navigated.

Any scientific and/or practical usefulness that may be derived from a Fo-AEM-QM has limited explanatory powers due to the intrinsic limitations of models in general, and of future-oriented AEMs in particular (i.e., “conditions possibilities; Section 3.1). To this point, the claims on scientific and/or practical usefulness (i.e., the proposition articulated by the model) constitute the primary subject of to the scientific validity assessment. As such, particularly if scientific validity constitutes a goal, it is important to clearly state what the “claim of truth” consists of (e.g., Fumagalli, 2016). As such, the limitations of the model should be acknowledged, not minimized. This is important, not least, to avoid giving rise to distorted and reductionist conclusions (Botha, 1989), but also to focus the quality efforts of the modeler and facilitate, or target, the model evaluators efforts.

“(Novel) Scientific Contribution” bridges the intersection of scientific validity and scientific usefulness aspects (yellow and green; Figure 5). Herein, scientific validity is an expectation of, and precursor to, scientific usefulness—hence, in this regard, the aspects are synergistic. First of all, a model’s ability to contribute to the AEM field or theory (i.e., theory building) (A#1.a) is determined by the gap on which the model’s purpose is based; this may be the same as the research question, or may serve a narrower purpose (see, e.g., Bocken et al., 2016). Naturally, the model must also be relevant, meaning that it adheres to its purpose and is suited, compared to other models, to make this contribution (C#5.b).

A further synergy between scientific usefulness and validity lies in the models’ degree of alignment with, or adherence to, relevant conceptual definitions related to the AEM being modeled (e.g., CE and/or degrowth), without which the model can hardly make claims on knowledge-enhancement, let alone theory building (A#1.a). This concerns the selection of appropriate model specifications (e.g., model scope, assumptions, and theories; C#5.a). An example of such a specification in the development of a model of a CE pertains to the chosen definition of a CE, for instance, whether it is conceptualized as incorporating principles of degrowth (e.g., Schröder et al., 2019) or decoupled growth (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015). Also, validity in terms of model defensibility (i.e., actual adherence to model specifications; C#6) determines the scientific contribution. Lastly, assessing the accuracy of the model and its contribution to knowledge requires the appropriate model testing or utilization (C#10), transparency, and validity (#8–9 & 11), as dictated by the model’s purpose. Consequently, scientific usefulness and validity are highly synergistic.

“Valid Practical Application” bridges the intersection of practical usefulness and scientific validity (blue and yellow; Figure 5), evaluating the extent to which a model offers contextualized, applied, and concrete guidance to decision-makers, whilst being scientifically valid (i.e., transparent reasoning and methodological soundness). A Fo-AEM-QM of such a quality profile is unlikely to be stand-alone; instead, it relies on further model analysis, application or utilizing (C#10), such as employing the model in backcasting (Quist and Vergragt 2006) to understand ways to reach (or avoid) the future-oriented modeled state (i.e., the practical guidance; B#3.a).

Solid grounding of the model in previous research (i.e., through a review of existing knowledge) can improve its scientific validity as it ensures that no relevant existing knowledge is overlooked, thus affirming model accuracy and completeness (c.f. Nicholson et al., 2018). Such an outcome also has the benefit of ensuring that the guidance derived from the model to policymakers and strategic foresight practitioners is correct, based on the conditioned possibilities of the model. In this regard, practical usefulness and scientific validity are synergistic. However, especially a large amount of transparency information (C#11) (Figure 4) to support model validity may decrease practical accessibility (B#4), thus lower wider applicability of the model (B#3.a) outside of any practical insights explicitly stated by the modeler (B#3.b)—representing a tension between the two quality aspects (Figure 5). However, certain model formats (e.g., visuals, interactive tools, and summaries) may allow for high model accessibility, without compromising validity, similar to the appending of transparency information (Figure 4) in supplementary material (Section 5.1).

A “(Novel) Practically Useful Contribution” bridges the intersection of scientific and practical usefulness (blue and green; Figure 5). This type of contribution can be seen in Case #B (Table 1) as the clarification of (conceptual) CE vocabulary (i.e., scientifically useful), which was then used to formulate strategies for practitioners (i.e., practically useful). The value of this model for practitioners is likely to be derived from applications of the model, similar to the model quality profile of “Valid Practical Application” discussed above.

Practical usefulness is often the strength, and some may even say the very purpose, of Futures Studies in terms of the generation of ideas about the future with the purpose of supporting contemporary decision-makers (Bell, 2017; Schwarz et al., 1982; Chugh, 2021; Ramirez et al., 2015). This type of contribution prioritizes “learning” (i.e., creating a common understanding) among academics and practitioners, which is less concerned with validity. On this note, while Case #A was found to lack validity (Table 1), that model was used in the report to create a common point of reference regarding what a CE consists of, and was used throughout the report series to illustrate practical implications of a CE, such as employment effects (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013a, p. 69), and was also partially unpacked (see, e.g., Figure 14 zooming in on the biological material “wing” of the Butterfly; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013a, p. 52). This is a form of model use in which conceptual clarity is refined through the translation of abstract knowledge into operational or policy language—representing the synergistic nature between scientistic usefulness (i.e., theory) and practical usefulness (i.e., practice).

Nonetheless, tension may arise between these two aspects, as theoretical work tends to seek generalizability, whereas practice demand more contextual specificity (Sections 4.1.1 and 4.1.2). In this regard, the modeler must decide which aspects to prioritize or strike a balance between them. An illustrative example of the latter is a model of a common language for both academics and practitioners around “CE Loop Strategies.” This model does not necessarily offer a novel theoretical perspective on a CE, but instead established a common language for academics and practitioners to describe material loops in a realized CE (Svensson-Hoglund et al., under review).

As to validity in the context of modeling focusing on scientific and practical usefulness, model specifications (e.g., clear delimitations and scope) (C#5.a) and other validity MQCs may defeat the purpose of keeping the model “open” for further exploration and applications—as was done by Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013a, 2013b, 2014)—and ensure high model transferability (C#7). Nevertheless, to effectively use a model as a foundation or framing in this way, the scientific and practical usefulness of the future-oriented research overall (i.e., beyond the model) is arguably increased through the (explicit) specification of what the research framing consists of (i.e., model specifications; C#11.b). Also, to ensure the targeted quality outcome of practical and scientific usefulness, the model should preferably be appropriately tested (C#10), e.g., in a Delphi study with both academics and practitioners (Svensson-Hoglund et al., under review), which brings us to the center of Figure 5.

“(Novel) Practically Useful and Valid Contribution” (center of Figure 5) target all 11 MQCs (Table 1) across the three aspects. Although such a model may demonstrate high “utility” (Jaccard and Jacoby, 2020, p. 35), which all models should ideally aim for, the model case applications (Section 4.2) and the Practical MQCs Framework (Section 5.1) reveal that achieving such an all-encompassing quality profile is unrealistic. This is due to how, as discussed above, the three quality aspects might not always be compatible with one another, and some MQCs are contradictory, such as the inclusion of a detailed description of the knowledge contribution (A#1.b), the specification (C#11.b), as well as the modeling process (C#11.c–d), whilst also ensuring model accessibility (A#2 & B#4). Publication word limits may also constrain the extent of transparency that is possible to include in a publication, especially in combination with a detailed discussion on model applications. In addition, some models are intended to be quite general (i.e., have a more all-encompassing AEM scope), making it less relevant to specify which type of practitioner the model is useful for (B#3.b), or the specific conditions under which the scientific usefulness is applicable (A#1.b, based on C#11.b—model specifications). These tensions constitute fundamental challenges for researchers seeking to design rich, yet accessible models.

As it is improbable that a model could fully address all MQCs, the design and assessment of Fo-AEM-QM quality inevitably requires trade-offs, such as the choice between having a model that is detailed (i.e., valid) versus accessible (i.e., scientifically and especially practically useful). The center space of Figure 5 should therefore be regarded as emphasizing the three aspects to a varying degree. A model combining practical usefulness with scientific usefulness (green and blue; Figure 5) may settle on introducing a novel perspective of the AEM (i.e., weaker novelty; A#1.a) that is informative to practitioners (B#3.a), not develop the underlying AEM theory (i.e., stronger novelty; A#1.a)—all the while ensuring the appropriate validity to support such a claim. A model focusing on scientific usefulness and validity (green and yellow; Figure 5) is unlikely to have word space to thoroughly demonstrate practical usefulness; instead, the authors may choose to only lightly address practical usefulness by outlining a few sentences on “practical implications” in the conclusion section. On the other hand, a model with a quality profile emphasizing practical usefulness, combined with validity (blue and yellow; Figure 5), would, instead, devote a substantial portion of its content to the elaboration of the practical implications of the work, for instance, by discussing how policy frameworks and business strategies can be formulated to achieve specific objectives (see Bocken et al., 2016).

In summary, the quality aspect constellation of any F-AEM-QM (Figure 5) should be strategically considered, depending on the model developer’s goal and model purpose (i.e., the model’s quality profile), and communicated to model evaluators and users to set the right expectations. More research is needed on model quality profiles.

Overall, the 11 MQCs (Table 1), the Practical MQCs Framework (Figure 4), and the analysis of overlaps and quality profiles (Figure 5 and Section 5.2) advance existing knowledge by consolidating scattered quality considerations (Section 4.1) into comprehensive, structured, and purpose-driven quality guidance (cf. Mäki, 2005; Checkland, 1995; Gray, 2018). The considerations are specifically designed to address the complexities of future-oriented qualitative modeling of alternative economic models, systematically and strategically integrating scientific validity, scientific usefulness, and practical usefulness.

The limitations include the select literature review (Section 4.1) conducted by the authors based on relevance, which may have excluded other valuable quality guidance unknown to the authors that could enhance future-oriented qualitative models. Additionally, context-specific factors may affect the applicability of the proposed considerations. Furthermore, the framework’s focus on purposeful, strategic quality profiles might constrain exploratory or innovative modeling approaches that fall outside established considerations. Lastly, the potential for flexibility in quality emphasis, based on the model’s quality profile, particularly in future-oriented qualitative modeling (Figure 5), may complicate the use of the MQCs when a model may need to be disqualified, e.g., as being unworthy of belief, as it could invite grey zones and subjective judgment. Nevertheless, the MQCs, particularly the three aspects, provide a thoughtful and beneficial starting point. Further research is necessary to test, validate, and refine the considerations (Table 1) and frameworks (Figures 4, 5) presented. Future research is discussed below.

6 Conclusion

This paper set out to advance the quality, and thereby the use, of qualitative models in future- and sustainability-oriented AEM research, considering the quality guidance needs of both model developers and evaluators/users. The research question consisted of defining what “quality” means for Future-oriented Alternative Economic Models Qualitative Models (Fo-AEM-QM). This was accomplished by: (1) Defining three key aspects of qualitative model quality—scientific usefulness, practical usefulness, and scientific validity; (2) Introducing 11 Model Quality Considerations (MQCs) that act as a practical checklist and guidance tool for model developers and evaluators/users; (3) Outlining how the MQCs relate to one another and the implications for model developers and evaluators, captured in a Practical Framework for Fo-AEM-QM developers and evaluators (Section 5.1); (4) Emphasizing the need for model developers to strategically prioritize which quality aspects to emphasize depending on the model’s purpose, thereby promoting intentional and transparent modeling choices; and (5) Encouraging model evaluators to critically assess model quality using the MQCs, while recognizing the need for model developers’ to purposefully mange trade-offs and strategically prioritize quality outcomes, rather than expecting all quality criteria to be met.

Overall, this work advances the use of qualitative models in future- and sustainability-oriented Alternative Economic Models (Fo-AEM-QMs) research by providing practical, purpose-sensitive guidance for both model development and evaluation. This is crucial for making qualitative models more reliable and trustworthy for scientific and practical applications and guidance, such as policymaking, education and business development.

Future research should explore the implications of model quality as it depends (or not) on the model’s purpose or quality profile, such as for framing research scope versus illustrating research findings, as well as for theory-building versus practical usefulness. To this end, in addition to testing the MQCs on diverse types of qualitative AEM models to facilitate further refinement or adaptation and to ensure relevance of the MQC, future research should explore the role of Fo-AEM-QMs in AEM theory development and the implications for the MQCs. Finally, as model quality requires the formulation of a plan made up of concrete measures, we recommend the development of step-by-step modeling approaches in which the application of the MQCs may be systematically incorporated.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SS-H: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. DG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Supervision. JRu: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JRi: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Open access funding provided by Lund University. SS-H was funded by the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Sciences (ICTAS) at Virginia Tech.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsus.2025.1687585/full#supplementary-material

References

Bell, W. (2017). Foundations of futures studies: history, purposes, and knowledge. 1st Edn: Routledge.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: principles, methods, and practices : Global Text Project.

Biermann, F., Hickmann, T., Sénit, C.-A., Beisheim, M., Bernstein, S., Chasek, P., et al. (2022). Scientific evidence on the political impact of the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 5, 795–800. doi: 10.1038/s41893-022-00909-5

Bocken, N. M. P., de Pauw, I., Bakker, C., and van der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 33, 308–320. doi: 10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124

Botha, E. M. (1989). Theory development in perspective: the role of conceptual frameworks and models in theory development. J Adv. Nurs. 14, 49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03404

Cairney, P. (2020). Understanding public policy: theories and issues. 2nd Edn. London: Macmillan International Higher Education Red Globe Press.

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W. J. V., and Salomone, R. (2025). Degrowth or barbarism? An exploration of four circular futures for 2050. Front. Sustain. 6:1527052. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1527052

Camacho-Otero, J., Boks, C., and Pettersen, I. N. (2019). User acceptance and adoption of circular offerings in the fashion sector: insights from user-generated online reviews. J. Clean. Prod. 231, 928–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.162

Checkland, P. (1995). Model validation in soft systems practice. Syst. Res. 12, 47–54. doi: 10.1002/sres.3850120108

Chugh, A. (2021). What is “futures studies” and how can it improve our world? World Economic Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/10/what-is-futures-studies-and-how-can-it-improve-our-world/

Corazza, G. E. (2024). “Creativity and futures studies” in Handbook of futures studies (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing), 131–144.

Cornelissen, J., Höllerer, M. A., and Seidl, D. (2021). What theory is and can be: forms of theorizing in organizational scholarship. Organ. Theory 2:26317877211020328. doi: 10.1177/26317877211020328

Corvellec, H., Stowell, A. F., and Johansson, N. (2022). Critiques of the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 26, 421–432. doi: 10.1111/jiec.13187

David, A. (2001). Models implementation: a state of the art. J. Oper. Res. 134, 459–480. doi: 10.1016/S0377-2217(00)00269-1

de Gooyert, V., Awan, A., Gürsan, C., Swennenhuis, F., Janipour, Z., and Gonella, S. (2024). Building on and contributing to sustainability transitions research with qualitative system dynamics. Sustain. Sci. 19, 1949–1962. doi: 10.1007/s11625-024-01548-9

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013a). Towards the circular economy: economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition, Vol. 1. Available online at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2013b). Towards the circular economy: economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition, Vol. 2. Available online at: https://content.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/m/50c85a620a58955/original/Towards-the-circular-economy-Vol-2.pdf?_gl=1*1txktho*_gcl_au*MTMwNjU5Mjk1LjE3NDQxMzI3Mzk.*_ga*NDg4ODEyNDA5LjE3NDQxMzI3MjI.*_ga_V32N675KJX*MTc0NDI5MzQzNC41LjEuMTc0NDI5NDQ0MS41OS4wLjA

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2014). Towards the circular economy: economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition, Vol. 3. Available online at: https://content.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/m/6a11c4eb28e1f628/original/Towards-the-circular-economy-Vol-3-Accelerating-the-scale-up-across-global-supply-chains.pdf?_gl=1*uzjabg*_gcl_au*MTMwNjU5Mjk1LjE3NDQxMzI3Mzk.*_ga*NDg4ODEyNDA5LjE3NDQxMzI3MjI.*_ga_V32N675KJX*MTc0NDI5MzQzNC41LjEuMTc0NDI5Mzk4OS41OC4wLjA

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2015). Growth within: a circular economy vision for a competitive Europe. Cowes, UK: Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Fawcett, J. (2005). Criteria for evaluation of theory. Nurs. Sci. Q. 18, 131–135. doi: 10.1177/0894318405274823,

Fumagalli, R. (2016). Why we cannot learn from minimal models. Erkenntnis 81, 433–455. doi: 10.1007/s10670-015-9749-7

Gbededo, M. A., and Liyanage, K. (2020). Descriptive framework for simulation-aided sustainability decision-making: a Delphi study. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 22, 45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2020.02.006

Giannetti, B. F., Fonseca, T., Almeida, C. M. V. B., de Oliveira, J. H., Valenti, W. C., and Agostinho, F. (2021). Beyond a sustainable consumption behavior: what post-pandemic world do we want to live in? Front. Sustain. 2:635761. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2021.635761

Grüne-Yanoff, T. (2009). Learning from minimal economic models. Erkenntnis 70, 81–99. doi: 10.1007/s10670-008-9138-6

Hanger-Kopp, S., Lemke, L. K.-G., and Beier, J. (2024). What qualitative systems mapping is and what it could be: integrating and visualizing diverse knowledge of complex problems. Sustain. Sci. 19, 1065–1078. doi: 10.1007/s11625-024-01497-3

Hassan, H., and Faggian, R. (2023). System thinking approaches for circular economy: enabling inclusive, synergistic, and eco-effective pathways for sustainable development. Front. Sustain. 4:1267282. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2023.1267282

Hickel, J. (2021). What does degrowth mean? A few points of clarification. Globalizations 18, 1105–1111. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2020.1812222

Jaccard, J., and Jacoby, J. (2020). Theory construction and model-building skills: a practical guide for social scientists. Second Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Jakeman, A. J., Letcher, R. A., and Norton, J. P. (2006). Ten iterative steps in development and evaluation of environmental models. Environ. Model. Softw. 21, 602–614. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2006.01.004

Kallis, G., Kerschner, C., and Martinez-Alier, J. (2012). The economics of degrowth. Ecol. Econ. 84, 172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.017

Kirchherr, J., Yang, N.-H. N., Schulze-Spüntrup, F., Heerink, M. J., and Hartley, K. (2023). Conceptualizing the circular economy (revisited): an analysis of 221 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 194:107001. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107001

Klitgaard, K. A., and Krall, L. (2012). Ecological economics, degrowth, and institutional change. Ecol. Econ. 84, 247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.11.008

LeFebvre, L. (2017). “Variables, conceptualization” in The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.).

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1986). “But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation” in Naturalistic evaluation: new directions for program evaluation. ed. D. D. Williams, vol. 30 (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass).

Ling, G. H. T., and Leng, P. C. (2018). Ten steps qualitative modelling: development and validation of conceptual institutional-social-ecological model of public open space (POS) governance and quality. Resources 7:62. doi: 10.3390/resources7040062

Mäki, U. (2005). Models are experiments, experiments are models. J. Econ. Methodol. 12, 303–315. doi: 10.1080/13501780500086255

McLean, M., and Shepherd, P. (1976). The importance of model structure. Futures 8, 40–51. doi: 10.1016/0016-3287(76)90095-1

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Third Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Moon, K., and Browne, N. K. (2021). Developing shared qualitative models for complex systems. Conserv. Biol. 35, 1039–1050. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13632,

Morgan, D. L. (2018). Themes, theories, and models. Qual. Health Res. 28, 339–345. doi: 10.1177/1049732317750127,

Morseletto, P. (2022). Environmental principles for modern sustainable economic frameworks including the circular economy. Sustain. Sci. 17, 2165–2171. doi: 10.1007/s11625-022-01208-w

Nicholson, J. D., LaPlaca, P., Al-Abdin, A., Breese, R., and Khan, Z. (2018). What do introduction sections tell us about the intent of scholarly work: a contribution on contributions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 73, 206–219. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.02.014

Nikolova, B. (2014). The rise and promise of participatory foresight. Eur. J. Futures. Res. 2:33. doi: 10.1007/s40309-013-0033-2,

Otero, I., Rigal, S., Pereira, L., Kim, H., Gamboa, G., Tello, E., et al. (2024). Degrowth scenarios for biodiversity? Key methodological steps and a call for collaboration. Sustain. Sci. doi: 10.1007/s11625-024-01483-9

Partelow, S. (2023). What is a framework? Understanding their purpose, value, development and use. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 13, 510–519. doi: 10.1007/s13412-023-00833-w

Purvis, B., Mao, Y., and Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 14, 681–695. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

Quist, J., and Vergragt, P. (2006). Past and future of backcasting: the shift to stakeholder participation and a proposal for a methodological framework. Futures. 38, 1027–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.010,

Quist, J. (2016). “Backcasting” in Foresight in organizations. ed. P. van der Duin. 0th ed. (New York, NY: Routledge), 125–144.

Ramirez, R., Mukherjee, M., Vezzoli, S., and Kramer, A. M. (2015). Scenarios as a scholarly methodology to produce “interesting research”. Futures 71, 70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2015.06.006

Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Peterson, G. D., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Norström, A. V., Pereira, L., et al. (2020). Seeds of good anthropocenes: developing sustainability scenarios for northern Europe. Sustain. Sci. 15, 605–617. doi: 10.1007/s11625-019-00714-8

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Repko, A. F., and Szostak, R. (2021). Interdisciplinary research: process and theory. Fourth Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Rice, P. L., and Ezzy, D. (1999). Qualitative research methods: a health focus. South Melbourne, VIC: Oxford University Press.

Richert, C., Boschetti, F., Walker, I., Price, J., and Grigg, N. (2017). Testing the consistency between goals and policies for sustainable development: mental models of how the world works today are inconsistent with mental models of how the world will work in the future. Sustain. Sci. 12, 45–64. doi: 10.1007/s11625-016-0384-2

Rinaldi, P. N. (2023). Dealing with complex and uncertain futures: glimpses from transdisciplinary water research. Futures 147:103113. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2023.103113

Rolfe, G. (2006). Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: quality and the idea of qualitative research. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03727.x,

Sale, J. E. M., and Carlin, L. (2025). The reliance on conceptual frameworks in qualitative research – a way forward. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 25:36. doi: 10.1186/s12874-025-02461-0,

Scholz, R. W., and Wellmer, F. W. (2021). Endangering the integrity of science by misusing unvalidated models and untested assumptions as facts: general considerations and the mineral and phosphorus scarcity fallacy. Sustain. Sci. 16, 2069–2086. doi: 10.1007/s11625-021-01006-w,

Schröder, P., Bengtsson, M., Cohen, M., Dewick, P., Hofstetter, J., and Sarkis, J. (2019). Degrowth within – aligning circular economy and strong sustainability narratives. Resour. Conserv. Recycling 146, 190–191. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.038

Schwarz, B., Svedin, U., and Wittrock, B. (1982). Methods in futures studies: problems and applications. Available online at: https://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9780429716805

Svenfelt, Å., Alfredsson, E. C., Bradley, K., Fauré, E., Finnveden, G., Fuehrer, P., et al. (2019). Scenarios for sustainable futures beyond GDP growth 2050. Futures 111, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2019.05.001

Svensson-Hoglund, S., Laurell Thorslund, M., Luth Richter, J., Richter Olsson, A., Jensen, C., Quist, J., et al. (2022). Futures of fixing: exploring the life of product users in circular economy repair society scenarios. Lund: IIIEE, Lund University.

Svensson-Hoglund, S., Russell, J.D., Richter, J.L., Dewick, P., Milios, L., Calisto Friant, M., et al. (under review). Advancing our understanding of CE loop strategies: a synthesizing framework for durable consumer products

Thomas, E., and Magilvy, J. K. (2011). Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research: scientific inquiry. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 16, 151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00283.x,

Varpio, L., Paradis, E., Uijtdehaage, S., and Young, M. (2020). The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad. Med. 95, 989–994. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075,

Velenturf, A. P. M., Archer, S. A., Gomes, H. I., Christgen, B., Lag-Brotons, A. J., and Purnell, P. (2019). Circular economy and the matter of integrated resources. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.449,

Voulvoulis, N. (2022). Transitioning to a sustainable circular economy: the transformation required to decouple growth from environmental degradation. Front. Sustain. 3:859896. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.859896

Weigend Rodríguez, R., Pomponi, F., Webster, K., and D’Amico, B. (2020). The future of the circular economy and the circular economy of the future. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 10, 529–546. doi: 10.1108/BEPAM-07-2019-0063

Keywords: conceptual modeling, qualitative modeling method, framework, alternative economic model, alternative economic system, futures studies

Citation: Svensson-Hoglund S, Guzzo D, Russell JD and Richter JL (2025) Strengthening the quality of qualitative models: a quality framework for future-oriented sustainability research. Front. Sustain. 6:1687585. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1687585

Edited by:

Idiano D'Adamo, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Giacomo Di Foggia, University of Milano-Bicocca, ItalyDimitrios Nalmpantis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Copyright © 2025 Svensson-Hoglund, Guzzo, Russell and Richter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jessika Luth Richter, amVzc2lrYS5yaWNodGVyQGlpaWVlLmx1LnNl

Sahra Svensson-Hoglund

Sahra Svensson-Hoglund Daniel Guzzo2

Daniel Guzzo2 Jennifer D. Russell

Jennifer D. Russell Jessika Luth Richter

Jessika Luth Richter