- 1Graduate Program of Resource and Environmental Economics, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia

- 2Department of Agricultural Socioeconomics, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

- 3Department of Agronomy, Unversity of Andalas, Padang, Indonesia

- 4Agricultural Economics and Rural Development, Faculty of Agriculture - Omdurman Islamic University, Khartoum, Sudan

- 5Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Negeri Makassar, Makassar, Indoensia

- 6Faculty of Agriculture, University of Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jawa Timur, Surabaya, Indonesia

This study examines the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain as an integrated rural system in which economic, cultural, and environmental sustainability are closely intertwined. Using a qualitative case study approach, we conducted 21 semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations with diverse actors including farmers, farmer groups, cooperatives, traders, processors, coffee shop owners, extension agents, government officials, and input suppliers. The data were thematically coded and interpreted through institutional, economic, and cultural lenses, with triangulation across methods, sources, and theories applied to strengthen credibility. The findings reveal that farmers face weak bargaining power in markets dominated by middlemen, whereas cooperative leaders struggle with governance and limited resources. Inconsistent postharvest practices and inadequate infrastructure further compromise product quality, and many farmers have voiced concerns about the erosion of cultural traditions linked to coffee rituals. Addressing these challenges requires strengthening cooperatives to improve bargaining power, upgrading infrastructure to ensure quality consistency, and promoting certification schemes and storytelling to valorize ecological stewardship and cultural identity. This study highlights the need for sustainability-oriented interventions that strengthen cooperatives, improve infrastructure and market access, promote postharvest innovations, and expand certification frameworks, demonstrating how value chains can be harnessed as pathways for inclusive and sustainable rural development.

1 Introduction

Indonesia is one of the world's leading coffee producers, with Arabica coffee contributing significantly to its national output (Jha, 2020). Among the country's diverse regions, Toraja in South Sulawesi stands out for producing high-quality Arabica beans grown in volcanic highlands under traditional shade-grown agroforestry systems (Tscharntke et al., 2011). Renowned for its distinctive flavor, cultural heritage, and environmental sustainability, Arabica coffee from Toraja has secured a premium position in international specialty markets, particularly in Japan, Europe, and the United States (Rahardjo et al., 2020; Rico et al., 2024a; Rombe et al., 2021; Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). Beyond its economic contribution, Toraja coffee sustains rural livelihoods, helps preserve biodiversity, and maintains cultural traditions, making it an exemplary case for exploring the intersection of economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of a global value chain.

The strong national and international potential of Arabica coffee from Toraja is rooted in its unique geography, volcanic soils, and cool climate, which produce premium quality beans with a distinctive taste. The rising global demand has driven production growth from approximately 2,110 tons in 2015 to more than 9,000 tons in 2024 (BPS Sulawesi Selatan, 2024), creating both livelihood opportunities and cultural pride for farming households. Traditional agroforestry systems continue to sustain biodiversity and soil health (Vaast and Somarriba, 2014).

Expansion has been supported by government and private initiatives that have encouraged the conversion of less-profitable crops. With an estimated 42,000 ha of additional suitable land, North Toraja retains significant potential to strengthen farmer welfare and Indonesia's global competitiveness (Haverhals et al., 2016; Rico et al., 2024b). At the same time, coffee remains deeply embedded in Toraja's cultural and ceremonial life, featured in events such as Rambu Solo' and Rambu Tuka', where it symbolizes identity, hospitality, and unity (Bigalke, 2006; Rahardjo et al., 2020; Rombe et al., 2021). Beyond its economic role, it fosters cultural preservation and social bonding (Irmayani and Ambar, 2024; Neilson, 2008). Its Geographical Indication status enhances its market value and underscores the need to safeguard its authenticity and tradition (Giovannucci et al., 2012; Rombe et al., 2022; Wahyudi and Jati, 2012).

Despite its strengths, the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain faces serious sustainability challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, limited technology adoption, and socioeconomic inequalities that restrict farmer benefits (Sia et al., 2025). Farmers often lack bargaining power, with profits largely captured by intermediaries and processors (Devaux et al., 2018; Salam et al., 2021). Interventions to address these issues have often been constrained by the complex realities of smallholder livelihoods and cultural dynamics (Leakey, 2014).

Addressing these barriers requires a comprehensive framework that integrates economic, technological, institutional, and cultural approaches. Strategies such as improved post-harvest practices, certification schemes, and organic methods can expand access to premium markets (Dekens and Bagamba, 2014; Musa et al., 2020; Salam et al., 2021), whereas stronger cooperatives and institutions can improve coordination and equity (Addoah et al., 2025; Sia et al., 2025). Importantly, interventions must respect local livelihoods and cultural values to remain sustainable and inclusive (Neilson and Shonk, 2014; Rombe et al., 2021). Together, these approaches highlight the interplay between ecological, economic, social, and cultural objectives, positioning the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain as a catalyst for inclusive rural development (Horton et al., 2023).

Research on the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain highlights its importance for smallholder livelihoods, poverty reduction, and biodiversity conservation through shaded systems (Jha, 2020; Neilson and Shonk, 2014; Sia et al., 2025). Studies also emphasize its cultural significance in rituals and identity (Bigalke, 2006; Irmayani and Ambar, 2024; Rahardjo et al., 2020; Rombe et al., 2021) and its potential in the global market (Haverhals et al., 2016). However, persistent inequities limit farmer benefits, with intermediaries and processors capturing higher margins, while infrastructure, technology adoption, and access to capital remain weak (Devaux et al., 2018; Roldan et al., 2013; Salam et al., 2021; Sia et al., 2025). Prior studies often address economic, environmental, or cultural aspects in isolation, without examining how these dimensions interact within the value chain (Leakey and Van Damme, 2014; Rico et al., 2024b; Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). This gap underscores the need for an integrated analysis of how poverty alleviation, environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and export performance converge to shape inclusive and sustainable rural development in Toraja, Indonesia.

This study examines the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain as an integrated system that contributes to poverty alleviation, environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and export competitiveness in the country. It analyzes how these dimensions are embedded in production, processing, and marketing, while also assessing the synergies and trade-offs that emerge across the chain. By adopting a holistic perspective, this study offers insights into strategies that align economic, ecological, cultural, and market goals with sustainable development.

Simultaneously, this study situates Toraja coffee within the broader sustainability debate, where agricultural value chains are viewed as critical pathways toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Toraja illustrates how ecological knowledge, cultural traditions, and global market linkages intersect to create outcomes that extend beyond the local economy. By framing coffee as both a livelihood and a cultural–ecological system, this study highlights the importance of integrating environmental stewardship, cultural preservation, and inclusive growth when designing strategies for rural sustainability.

2 Methods

2.1 Research design

This study adopted a qualitative case study approach to capture the depth and complexity of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain, focusing on its economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of it. This design was chosen because it allows for nuanced insights into actor interactions, cultural meanings, institutional dynamics, and sustainability challenges that are not easily revealed through quantitative instruments. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, expert interview guides, and direct field observations, complemented by secondary data from statistical reports, academic publications, policy documents and existing value chain analyses.

Key informants, including farmers, cooperatives, traders, processors, coffee shop operators, extension agents, and government officials, were purposively selected to ensure diverse representation across both upstream and downstream actors. By integrating multiple stakeholder perspectives with secondary evidence, this design provides an in-depth understanding of how local livelihoods, traditional practices, ecological sustainability, and global specialty markets intersect, while highlighting actionable pathways toward sustainability.

2.2 Study site

The study was conducted in North Toraja Regency, South Sulawesi, Indonesia—a region known for high-quality Arabica coffee, recognized with Geographical Indication (GI) status. Located approximately 300 kilometers north of Makassar, North Toraja encompasses an area of about 1,151 square kilometers, characterized by mountainous terrain, fertile volcanic soils, and altitudes ranging from 600 to 1,500 meters above sea level. These unique agro-ecological conditions—cool climate, diverse microclimates, and rich soil—produce Arabica coffee with a distinctive flavor profile that is highly valued in domestic and international specialty markets, particularly in Japan, Europe, and the United States.

Beyond its economic significance, coffee in North Toraja holds profound cultural value, interwoven with local rituals and traditions such as Rambu Solo' and Rambu Tuka'. Despite its advantages, the region faces persistent challenges including aging plantations and low productivity (Neilson, 2008; Wahyudi and Jati, 2012), weak farmer bargaining power and limited access to premium markets (Devaux et al., 2018; Horton et al., 2023; Roldan et al., 2013), and environmental pressures from climate variability and land degradation (Vaast and Somarriba, 2014). These dynamics make North Toraja an ideal site to examine the integrated economic, cultural, and environmental sustainability of specialty coffee production.

2.3 Data collection

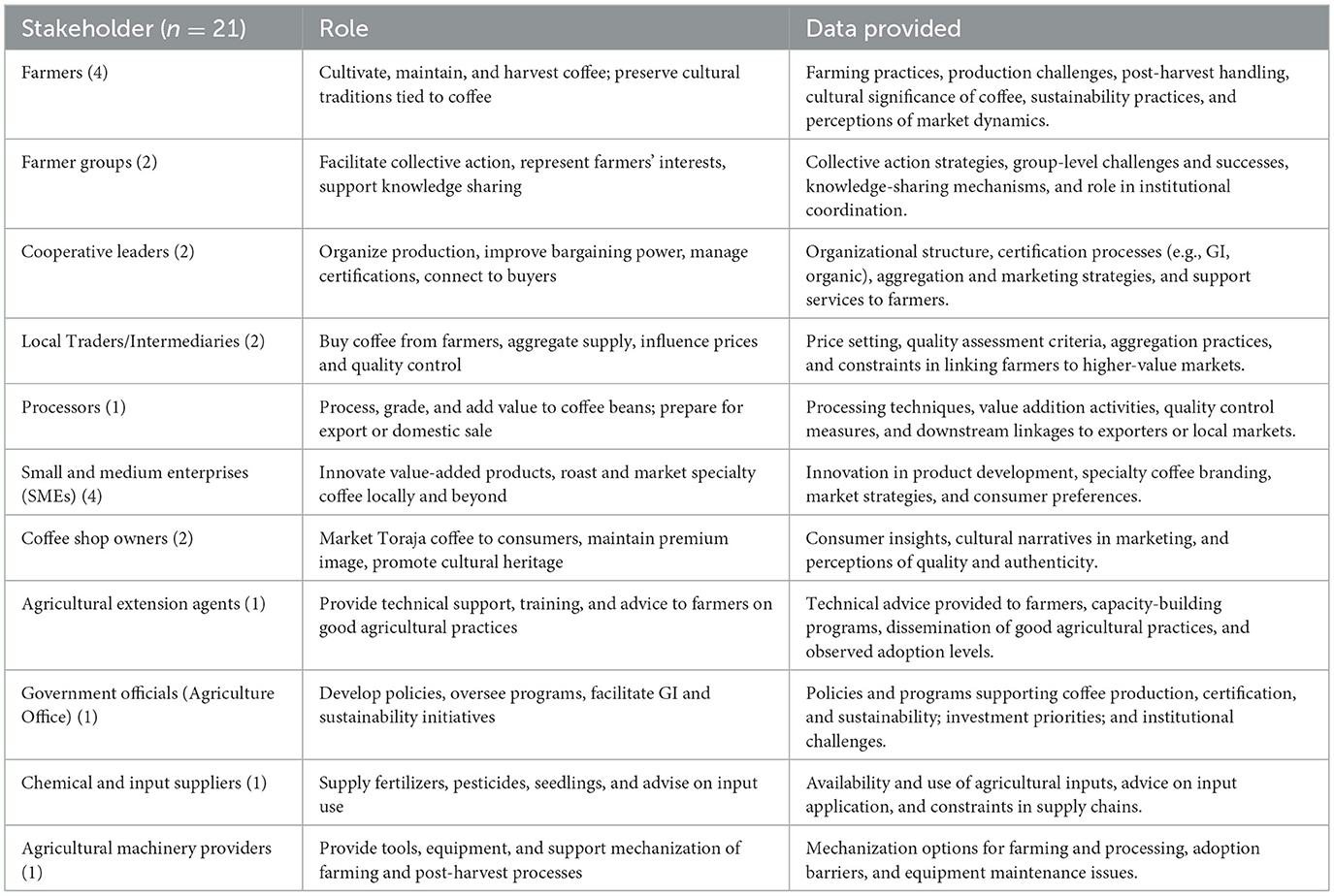

This study employed a combination of primary and secondary data-collection methods to capture the multifaceted economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain. Primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), expert questionnaires, and direct field observations. Informants were purposively selected to capture diverse perspectives across the Toraja coffee value chain, including farmers, farmer groups, cooperatives, and SMEs (traders, processors, retailers, and coffee shop operators), as well as extension agents and government officials. The selection of informants was based on their expertise, institutional roles, and active involvement in the coffee sector, ensuring meaningful insights from both the upstream and downstream actors (Table 1).

To enhance the validity of our findings, we applied triangulation through three complementary strategies. First, methodological triangulation was implemented by combining semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations, allowing insights from one method to be cross-checked with others. Second, data source triangulation was achieved by purposively selecting respondents from different categories of stakeholders—farmers, cooperatives, traders, processors, government officials, extension agents, and input providers—ensuring perspectives were captured from both upstream and downstream segments of the value chain. Third, theoretical triangulation was employed by interpreting the data through institutional, economic, and cultural lenses, which provided a richer and more balanced understanding of the sustainability challenges. Together, these strategies strengthened the credibility and trustworthiness of the study by minimizing bias and confirming the consistency of findings across methods, sources, and perspectives.

In total, 21 respondents were purposively selected to reflect the diversity of actors in the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain, including farmers, farmer groups, cooperative leaders, traders, processors, coffee shop operators, extension agents, government officials, and input and machinery suppliers. The selection was guided by their institutional roles, expertise, and active involvement in the sector, ensuring representation from both upstream and downstream perspectives of the sector. Although modest in number, this sample was sufficient in qualitative terms, as adequacy is determined by the concepts of information power (Malterud et al., 2016) and theoretical saturation (Guest et al., 2006), where richness and diversity of insights are prioritized over numerical size. This approach provides a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the social, economic, cultural, and environmental dynamics shaping the Toraja coffee value chain while maintaining methodological rigor.

All participants in this study, including those in focus group discussions (FGDs) and interviews, provided informed consent prior to participation. At the outset of each session, they were briefed on the study's purpose, procedures, and their rights, including the option to withdraw at any time without any consequences. Participation was voluntary. To maintain confidentiality, the responses were anonymized and reported in aggregate form, with no personal identifiers collected or disclosed. Access to contact information was limited to the principal investigator for coordination purposes.

To comprehensively examine the economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain, this study employed multiple qualitative and secondary data-collection methods. Each method captures unique aspects of stakeholder perspectives, institutional dynamics, sustainability practices, and cultural contexts, providing a holistic understanding of the value chain. The table below summarizes the types of data collected according to each method, illustrating how the complementary approaches contributed to a rich and nuanced analysis (Table 2).

Secondary data were gathered from statistical reports, academic literature, government policy documents, and previous research in the Toraja coffee sector. These sources provide a valuable context for production trends, export performance, institutional arrangements, and environmental conditions. Combining these methods allowed the study to triangulate the findings and build a comprehensive, evidence-based understanding of the complex interrelations within the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain.

To enhance the validity of our findings, we applied triangulation using three complementary strategies. First, methodological triangulation was implemented by combining semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations, allowing insights from one method to be cross-checked with those from others. Second, data source triangulation was achieved by purposively selecting respondents from different categories of stakeholders—farmers, cooperatives, traders, processors, government officials, extension agents, and input providers—ensuring that perspectives were captured from both upstream and downstream segments of the value chain. Third, theoretical triangulation was employed by interpreting the data through institutional, economic, and cultural lenses, which provided a richer and more balanced understanding of sustainability challenges. Together, these strategies strengthened the credibility and trustworthiness of the study by minimizing bias and confirming the consistency of findings across methods, sources, and perspective.

2.4 Data analysis

Data collected through semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), expert interview guides, direct field observations, and secondary sources were analyzed using a qualitative, interpretive approach to uncover the interrelations between the economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain. Interviews and FGD transcripts were organized, transcribed, and thematically coded, beginning with open coding to identify recurring ideas and concepts, which were then grouped into broader categories that reflected stakeholder roles, sustainability challenges, cultural significance, market constraints, and potential interventions.

To strengthen reliability, the coding decisions were collaboratively reviewed by the research team, and differences in interpretation were discussed until a consensus was reached. Reflexivity was maintained through detailed note-taking and peer debriefing, which reduced potential bias and ensured that the interpretations remained grounded in the data. Field observation notes and photographs were interpreted alongside the coded transcripts to contextualize and validate the emerging themes. Secondary data from reports and policy documents were used to corroborate the findings and situate them within the wider regional and global contexts. This triangulated, multi-method analysis enhanced the credibility and trustworthiness of the study, enabling a robust and holistic understanding of how economic opportunities, cultural heritage, and environmental stewardship converge in the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain, and providing evidence to propose targeted strategies for enhancing sustainability and inclusivity.

3 Results

The findings from our fieldwork confirm that sustaining the Toraja Arabica value chain requires simultaneously addressing weak farmer bargaining power, inconsistent product quality, cultural erosion, and infrastructural gaps. Interviews and FGDs revealed that farmers experience low returns due to middlemen-dominated trade, while cooperative leaders struggle with governance and coordination. Farmers also described the importance of coffee in Tongkonan rituals, reinforcing how cultural practices influence production and marketing choices. By linking these local insights to the wider literature, this study demonstrates how multi-method triangulation can generate robust conclusions on the interconnected economic, socio-cultural, and environmental aspects of sustainability.

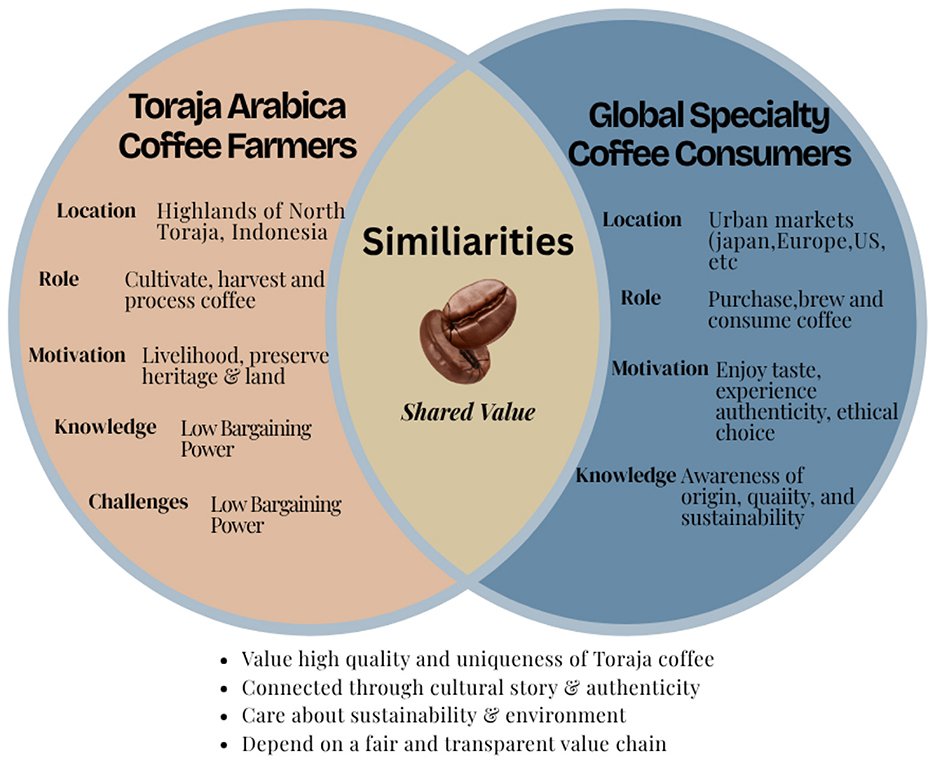

3.1 Toraja Arabica coffee farmers and global consumers

Farmers in Toraja view coffee as both a livelihood and heritage crop. They described limited bargaining power in markets dominated by middlemen and frequent price volatility, which complicates household planning. Cooperative leaders also pointed to governance and trust challenges that reduced their ability to consistently support members. Simultaneously, coffee is closely tied to rituals and land stewardship, reflecting its dual cultural and economic significance.

On the consumer side, demand in Japan, Europe, and North America highlights the preferences for authenticity, traceability, and sustainability. Certifications and Geographical Indication status offers a chance to enhance farmers' livelihoods while safeguarding Toraja's cultural and environmental heritage.

Geographical Indication (GI) labeling help Toraja coffee reach these markets but also impose administrative and financial costs on smallholders. As a result, while farmers face uncertainty and structural constraints, consumers largely experience Toraja coffee as a premium product associated with taste, identity, and ethical considerations.

Both groups depend on a transparent value chain; however, their positions are unequal. Narrowing this gap through stronger cooperatives, institutional support, and more direct farmer–consumer connections is essential for building a fairer and more resilient Toraja coffee system that benefits all stakeholders.

Figure 1 depicts the diagram of Toraja Arabica coffee farmers, and global specialty coffee consumers highlight their connections, similarities, and contrasts within the value chain. Toraja farmers in South Sulawesi grow high-quality Arabica coffee using traditional agroforestry, which supports biodiversity, soil health, and cultural heritage. For them, coffee was both a livelihood and a symbol of identity, woven into rituals, hospitality, and land stewardship. Meanwhile, consumers in markets such as Japan, Europe, and North America value their unique tastes, authentic stories, and sustainable production, seeking ethical, traceable products that link them to the farmers and landscapes behind each cup. Despite differences in roles, knowledge, and power, both groups shared a commitment to quality, authenticity, and sustainability. Strengthening connections through fair pricing, better infrastructure, certifications, and direct trade can create a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable coffee value chain.

Figure 1. Characteristics and connections between Toraja Arabica coffee farmers and global specialty coffee consumers.

3.2 Structure of the value chain

The Toraja Arabica coffee value chain exemplifies how a local agricultural product can combine economic, cultural, environmental, and export values. From the highlands of North Toraja, coffee grown by smallholder farmers moves through complex production, processing, and marketing stages to reach specialty markets in Japan, Europe, and North America. This process supports rural incomes while preserving cultural heritage and environmental sustainability.

The upstream stage is characterized by smallholder production on fragmented plots, where aging trees and low yields are recurring problems. Despite some training from PT Toarco Jaya and cooperatives, farmers noted that access to quality inputs remained limited. Midstream, most farmers continue traditional practices such as wet-hulling and sun drying, although inconsistent methods and inadequate infrastructure reduce quality reliability. Downstream, middlemen still dominate trade, lowering farmgate prices, while PT Toarco Jaya plays a crucial role in quality grading, branding, and exporting coffee to specialty markets.

At the midstream stage, postharvest handling and processing combine traditional and modern methods. Farmers harvest cherries by hand, wet-hull the beans, and dry them in the sun. Although training from PT Toarco Jaya and cooperatives has improved quality, inconsistent practices and poor infrastructure still lead to variability in product quality.

Finally, the downstream stage links farmers to local and international markets. Middlemen dominate local trade, often lowering farmgate prices and reducing transparency. PT Toarco Jaya plays a key role in aggregating, grading, branding, and exporting Toraja coffee to premium markets, with Geographical Indication (GI) status boosting its reputation and competitiveness abroad.

Figure 2 illustrates the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain illustrates the journey of coffee from smallholder farmers in North Toraja to specialty consumers worldwide, structured into the upstream, midstream, and downstream stages. Farmers grow coffee on small plots using traditional shade-grown agroforestry that preserves biodiversity and culture, although they face challenges such as low productivity, aging trees, and limited inputs, despite some cooperative support. At the midstream stage, farmers, processors, and PT Toarco Jaya handle postharvest activities, but inconsistent practices and poor infrastructure still affect quality. Downstream, PT Toarco Jaya, middlemen, and retailers manage branding, certification, and exports to premium markets, where consumers value their unique flavors, cultural stories, and sustainability. Strengthening transparency and equity across this chain can enhance the quality, identity, and benefits for both farmers and consumers.

Figure 2. Stages of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain: from farmers to global specialty markets.

3.3 Roles of key actors

Farmers remain custodians of both ecological knowledge and cultural heritage, but their capacity to influence prices is minimal. The cooperative representatives interviewed emphasized the importance of strengthening organizational capacity to increase bargaining power, although they acknowledged governance challenges. PT Toarco Jaya was recognized by farmers as both a source of training and a gatekeeper to premium market. Government officials noted efforts to expand certification and infrastructure; however, stakeholders across the chain described such support as uneven and fragmented. Consumers and retailers abroad complete the chain by rewarding authenticity and sustainability with premium prices, but these benefits often fail to trickle back to farmers in full.

Figure 3 shows the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain brings together diverse actors who sustain its production, processing, and marketing while preserving its cultural, economic, and environmental value. Farmers, as the foundation, grow coffee using traditional agroforestry that protects biodiversity and cultural heritage, but faces challenges such as limited inputs, training, and fair market access. Cooperatives help by organizing farmers, improving practices, and facilitating access to markets, although they struggle with weak governance and resources. PT Toarco Jaya connects local coffee to global specialty markets by ensuring quality, offering support, and managing branding and certification. Local governments and institutions provide policies, infrastructure, and certification, but their fragmented and underfunded support limits their impact. Ultimately, buyers value Toraja coffee's flavor, authenticity, and sustainability, and their willingness to pay a premium offers farmers better returns if the value chain ensures consistency, traceability, and fairness.

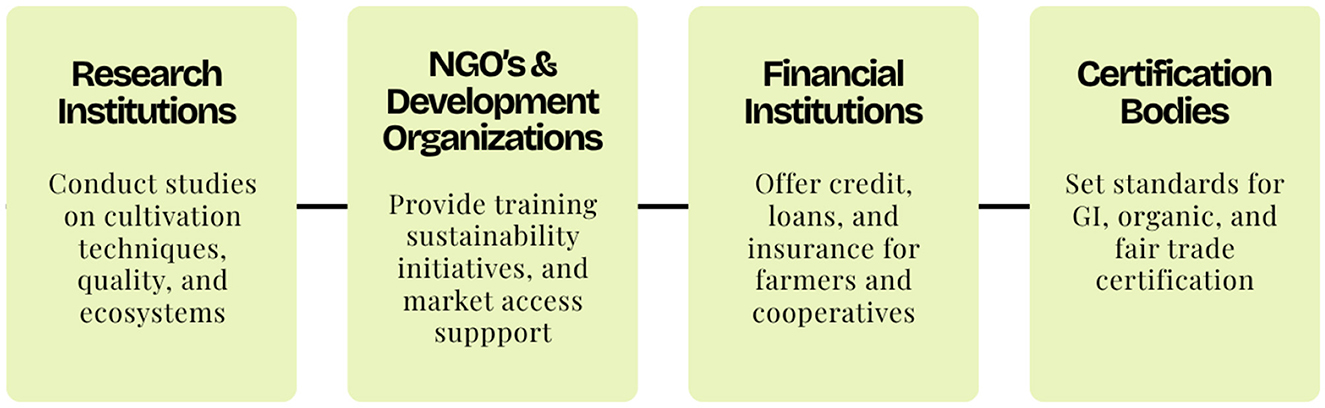

Supporting organizations play a crucial role in strengthening the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain by addressing its structural, social, and environmental challenges. Research institutions develop knowledge and innovations to improve farming practices, while NGOs and development agencies provide training, promote sustainability, and expand market access. Financial institutions offer credit and insurance to support investments, and certification bodies uphold quality and sustainability standards. Together, these actors bridge gaps in resources and coordination, fostering stronger connections across the chain and helping preserve the coffee's economic, cultural, and ecological value.

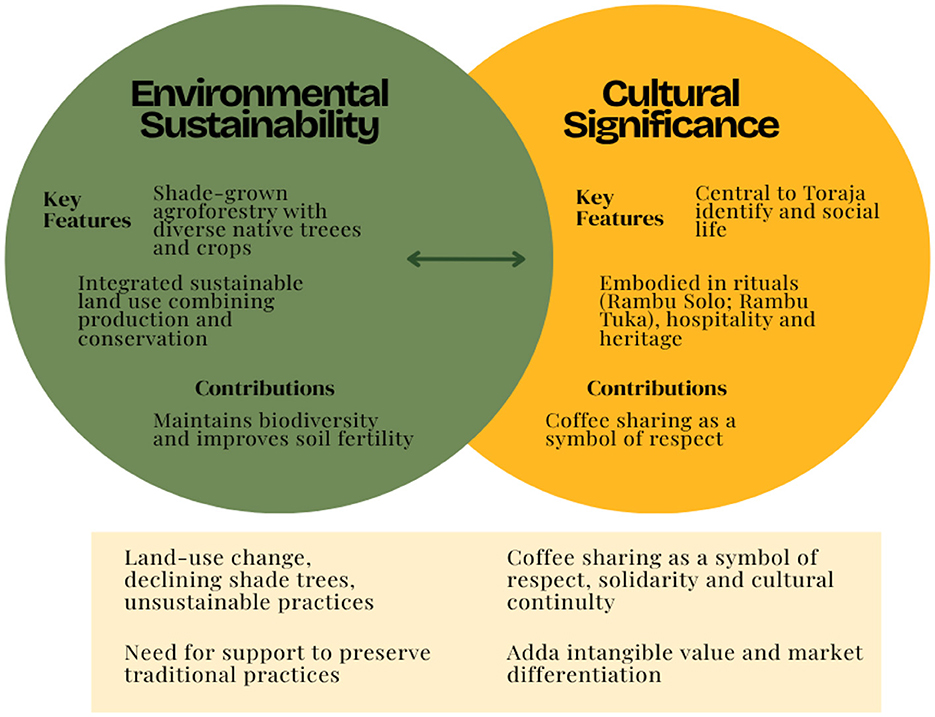

Figure 4 reflects the sustainability and cultural dimensions of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain reflect its strong ties to the environment and community. When grown in traditional agroforestry systems alongside native shade trees and crops, coffee supports biodiversity, soil fertility, water conservation, and climate resilience. However, land use changes and unsustainable practices threaten these benefits, underscoring the need to protect traditional methods. Culturally, coffee is central to Toraja's identity, featuring rituals, hospitality, and community bonds, symbolizing respect, solidarity, and heritage. However, commercialization risks eroding this cultural richness, making it crucial to balance modernization while preserving the environmental and cultural legacies that define Toraja coffee.

3.4 Environmental sustainability and cultural significance

The Toraja Arabica coffee value chain demonstrates the depth to which its sustainability and cultural dimensions are rooted in the environment and community. Traditional agroforestry systems support biodiversity, soil health, water conservation, and climate resilience, although these benefits are increasingly threatened by land-use changes and unsustainable practices. At the same time, coffee is a vital part of Toraja's identity, embedded in rituals, hospitality, and social ties as a symbol of respect, heritage, and solidarity. To sustain coffee's value and distinctiveness, it is essential to carefully balance modernization with the preservation of its environmental and cultural foundations.

The production of Toraja Arabica coffee contributes significantly to environmental sustainability through its traditional agroforestry systems. Coffee is cultivated under the shade of diverse tree species, which helps to maintain biodiversity, protect soil fertility, and regulate water cycles in the highland ecosystem. These practices also enhance resilience to climate variability by reducing erosion, moderating microclimates, and sustaining ecological functions essential for long-term productivity. The integration of coffee with native trees and other crops exemplifies a sustainable land-use strategy that aligns economic activity with conservation goals, demonstrating how agricultural production can coexist with environmental stewardship.

Culturally, Toraja Arabica coffee remains deeply intertwined with the identity and social fabric of the Toraja people. Beyond its economic value, coffee plays a central role in traditional rituals, such as the Rambu Solo' (funeral ceremonies) and Rambu Tuka' (thanksgiving rituals), where it symbolizes hospitality, respect, and communal solidarity. Sharing coffee is a customary practice in social gatherings, strengthening interpersonal ties and reinforcing cultural heritage. The unique sensory qualities of Toraja coffee—along with its association with ritual and identity—contribute to its cultural richness and market differentiation. However, increasing commercialization poses challenges to the preservation of these cultural practices, highlighting the need for strategies that protect and promote the intangible cultural heritage embedded in the coffee value chain.

Figure 5 highlights two critical dimensions of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain: environmental sustainability and cultural significance. Under environmental sustainability conditions, traditional shade-grown agroforestry systems with diverse native trees and crops contribute to biodiversity conservation, soil fertility, water regulation, and climate resilience. However, these benefits face challenges from land use change, declining shade cover, and the risk of unsustainable practices, underscoring the need to preserve traditional methods. On the cultural side, coffee remains central to Toraja's identity and social life, symbolized through rituals, hospitality, and shared heritage. It adds intangible value and market differentiation but is vulnerable to erosion as commercialization intensifies. The table thus illustrates how both dimensions enrich the value chain while also presenting challenges that must be carefully managed to maintain the Toraja coffee's unique ecological and cultural legacy.

Figure 5. Environmental sustainability and cultural significance of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain.

3.5 Challenges and constraints

The Toraja Arabica coffee value chain faces several persistent challenges that undermine its sustainability, inclusivity, and competitiveness. Farmers remain in a weak bargaining position, largely dependent on intermediaries to sell their coffee. This dependence often leaves them vulnerable to exploitative pricing and limits their ability to negotiate fair terms. The absence of strong, direct linkages with buyers in premium markets further exacerbates this issue, preventing farmers from capturing the full value of their high-quality beans.

Price instability is another major constraint. The lack of stable and equitable markets exposes farmers to fluctuations in global coffee prices and local market distortions. This volatility discourages investment in farm improvements and weakens long-term income security, making livelihoods precarious. Farmers often have little access to price information and limited capacity to hedge against these risks (Figure 6).

Quality inconsistency is also a significant issue, stemming from inadequate infrastructure and uneven adoption of best agricultural and postharvest practices. Many farmers still rely on traditional methods without sufficient training or access to improved facilities, resulting in variable bean quality that can tarnish the reputation of Toraja coffee in premium markets. Upgrading infrastructure and promoting standardized practices are critical to addressing this problem.

Environmental threats further complicate the situation. Soil degradation, caused by erosion and nutrient depletion, alongside increasing climate variability, threatens productivity, and farm resilience. Additionally, the gradual decline of shade tree cover undermines the ecological sustainability of the agroforestry systems that have traditionally supported both high-quality coffee production and biodiversity conservation.

Finally, the institutional landscape remains fragmented, with limited coordination among stakeholders. Local government, cooperatives, private companies, and certification bodies often work in silos, leading to inefficiencies and missed opportunities for synergy. Strengthening institutional support and fostering better collaboration are essential for addressing these structural weaknesses and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain.

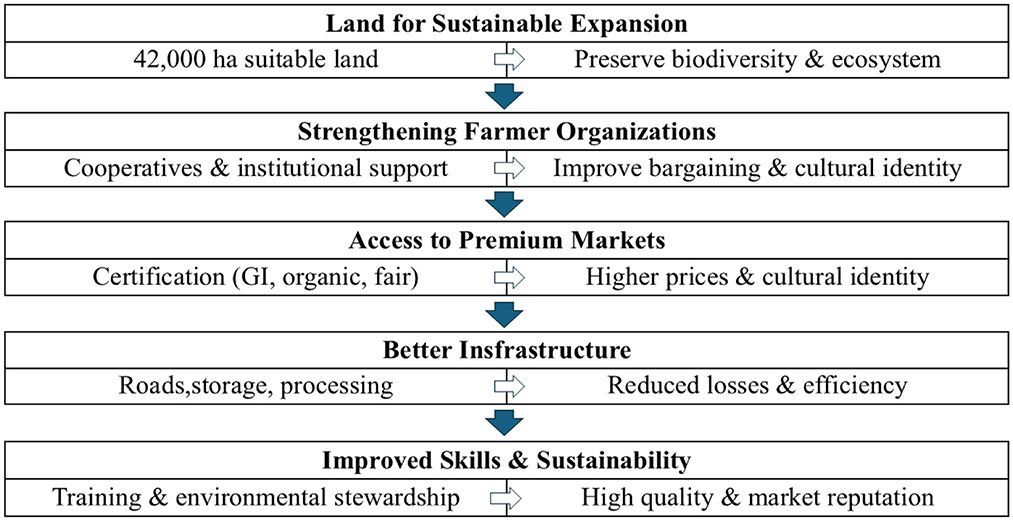

3.6 Opportunities and leverage points

The key opportunities and strategic leverage points for strengthening the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain. Despite ongoing challenges such as weak bargaining power, inconsistent quality, and fragmented institutional support, North Toraja holds significant untapped potential, with about 42,000 hectares of additional land suitable for Arabica cultivation. Managed through sustainable agroforestry, this land offers an opportunity to expand production while preserving environmental integrity and biodiversity. Strengthening farmer cooperatives and institutional support have emerged as crucial leverage points, as better-equipped cooperatives can improve aggregation, training, access to inputs, and farmers' bargaining power. Enhanced stakeholder coordination is essential to ensure consistent quality and fair value distribution. Certification schemes such as Geographical Indication (GI) and organic and fair trade present further opportunities by differentiating products, commanding higher premiums, and reinforcing Toraja's cultural and ecological identity. Direct marketing and storytelling can deepen the connections between farmers and consumers, fostering loyalty and willingness to pay. Finally, investments in infrastructure, training, and sustainable practices are vital to reducing postharvest losses, enhancing quality, and maintaining Toraja coffee's standing in global markets. Together, these opportunities provide a roadmap for unlocking the full potential of the value chain as a model of inclusive and sustainable rural development.

Figure 7 reveals the key opportunities and strategic leverage points for strengthening the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain. Despite ongoing challenges such as weak bargaining power, inconsistent quality, and fragmented institutional support, North Toraja holds significant untapped potential, with about 42,000 hectares of additional land suitable for Arabica cultivation. Managed through sustainable agroforestry, this land offers an opportunity to expand production while preserving environmental integrity and biodiversity. Strengthening farmer cooperatives and institutional support have emerged as crucial leverage points, as better-equipped cooperatives can improve aggregation, training, access to inputs, and farmers' bargaining power. Enhanced stakeholder coordination is essential to ensure consistent quality and fair value distribution. Certification schemes such as Geographical Indication (GI) and organic and fair-trade present further opportunities by differentiating products, commanding higher premiums, and reinforcing Toraja's cultural and ecological identity. Direct marketing and storytelling can deepen the connections between farmers and consumers, fostering loyalty and willingness to pay. Finally, investments in infrastructure, training, and sustainable practices are vital to reducing postharvest losses, enhancing quality, and maintaining Toraja coffee's standing in global markets. Together, these opportunities provide a roadmap for unlocking the full potential of the value chain as a model of inclusive and sustainable rural development.

These findings demonstrate that Toraja Arabica coffee is embedded in multiple sustainability pathways. Ecological pathways are evident in traditional agroforestry systems, which sustain biodiversity and regulate ecosystem services. Social pathways are reinforced through rituals, hospitality, and community cohesion, tied to coffee cultivation and consumption. Economic pathways have emerged through certification, branding, and global market integration. These pathways interact, at times, producing synergies—for example, when cultural identity enhances market appeal—and at other times creating tensions, such as when commercialization risks undermine cultural practices. Identifying these dynamics illustrates how agrifood value chains can advance sustainability transitions while highlighting the need for careful management of trade-offs.

4 Discussion

4.1 From local heritage to global sustainability lessons

Fieldwork revealed that farmers consistently described coffee as both a livelihood and cultural inheritance. Interviews and FGDs highlighted how rituals, such as Rambu Solo' and Rambu Tuka', directly shaped farming choices and reinforced the symbolic role of coffee in identity and respect. Farmers also emphasized that agroforestry practices are not only ecological traditions but also strategies to ensure soil fertility and resilience. These findings show that coffee is simultaneously economic, cultural, and ecological, confirming that Toraja's distinctiveness lies in its deliberate integration of heritage with environmental stewardship. Previous studies have noted similar dynamics in niche markets (Bigalke, 2006; Rombe et al., 2022; Vaast and Somarriba, 2014), but our results illustrate how they converge within a single value chain.

This unique combination of ritual significance, agroecological practices, and premium market potential distinguishes Toraja coffee from other specialty coffees. The volcanic soils and high-altitude agroforests of Toraja provide both distinctive flavor profiles and repositories of biodiversity and cultural knowledge (Lisnawati et al., 2017; Rico et al., 2024b). The embeddedness of coffee in ceremonies such as Rambu Solo' and Rambu Tuka' adds intangible value that resonates with consumer demand for authenticity and ethical sourcing (Bigalke, 2006; Rombe et al., 2022). While prior studies have often examined these dimensions separately, focusing on marketing challenges (Neilson and Shonk, 2014), the ecological benefits of shade-grown systems (Vaast and Somarriba, 2014), or cultural significance (Rombe et al., 2021), this study demonstrates how they converge within a single value chain. This offers a holistic perspective that highlights the need for sustainable value chain interventions to integrate economic, ecological, and cultural goals as mutually reinforcing sources of resilience and differentiation (Giovannucci et al., 2012; Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). Toraja coffee is distinguished from other specialty coffees by the combination of ritual significance, agroecological practices, and premium market potential. The volcanic soils and high-altitude agroforests of Toraja produce a distinctive flavor that appeals to global consumers while serving as repositories of biodiversity and cultural knowledge (Lisnawati et al., 2017; Rico et al., 2024a). Prior research has usually examined these aspects separately, focusing on the economic challenges of marketing (Neilson and Shonk, 2014), environmental benefits of shade-grown systems (Vaast and Somarriba, 2014), or cultural importance of coffee (Rombe et al., 2021). This study integrates these perspectives to demonstrate how they interact within a single value chain (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019), thereby providing a holistic contribution that is both academically significant and practically relevant for designing interventions that strengthen all three dimensions without compromising any of them.

4.2 Economic outcomes and challenges

Farmers and cooperative leaders we interviewed repeatedly stressed weak bargaining power and dependence on middlemen, which limited returns and discouraged investment in the sector. While cooperatives were seen as potential solutions, governance challenges reduced their effectiveness in addressing the issues. Farmers also pointed to certification (GI, organic, fair trade) as both an opportunity and a burden: it could secure premiums, but the administrative and financial costs were high. These findings highlight that market access improvements require stronger cooperative capacity and better infrastructure, echoing and extending earlier analyses (Musa et al., 2020; Neilson and Shonk, 2014). Rather than treating these issues in isolation, our evidence shows how certification costs, governance weaknesses, and infrastructural gaps interact to constrain premium market participation.

This structural asymmetry exposes farmers to exploitative pricing practices and limits their capacity to invest in quality improvement (Rico et al., 2024a). Such findings align with those of prior studies (Devaux et al., 2018; Musa et al., 2020; Roldan et al., 2013). That have documented how weak institutional arrangements and lack of direct access to markets undermine farmers' economic outcomes. By situating these constraints within the broader dynamics of global specialty markets, this study underscores the urgent need to rebalance power relationships in the chain to ensure equitable benefits for producers (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019).

4.3 Economic outcomes and challenges

To address these challenges, this study examines how institutional innovations, such as cooperatives, certification schemes, and direct marketing, can improve farmers' equity and profitability. Well-managed cooperatives can aggregate production, enhance bargaining power, provide technical support, and connect farmers to higher value markets (Addoah et al., 2025; Amoah and Addoah, 2021). Certification programs, including Geographical Indication (GI), organic, and fair trade, not only signal quality and authenticity, but also allow farmers to capture price premiums and reinforce Toraja's cultural and ecological identity (Giovannucci et al., 2012; Rombe et al., 2021; Wahyudi and Jati, 2012). Direct marketing and storytelling further bridge farmers and consumers, creating loyalty and willingness to pay for authentic and sustainably produced coffee (Rico et al., 2024a). Nonetheless, this study also highlights market volatility and infrastructure gaps as major obstacles to sustainable economic gains. Price fluctuations discourage investment and undermine income stability, whereas inadequate roads, storage, and processing facilities contribute to post-harvest losses and quality inconsistencies (Roldan et al., 2013; Salam et al., 2021; Sia et al., 2025). Unlike earlier studies that considered these issues in isolation, this study integrates them to show how systemic weaknesses in market structure, institutional support, and infrastructure interact to constrain farmers' economic potential (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). By illuminating these interconnections, this study contributes a holistic perspective to the literature and identifies pathways to enhance farmers' participation and capture value in global markets.

4.4 Cultural significance and risks

Farmers highlighted coffee's central role in social cohesion, describing its place in ceremonies and everyday hospitality as integral to the Toraja identity. However, many expressed concern that commercialization could reduce it to a mere commodity, stripping away its cultural meaning. This tension between modernization and heritage preservation underscores the need for strategies to protect authenticity. Approaches such as culturally sensitive branding and Geographical Indication (GI) certification can valorize cultural heritage while meeting consumer demand for authenticity and maintaining local integrity (Giovannucci et al., 2012; Rombe et al., 2022) Such practices imbue Toraja coffee with an intangible value that extends beyond its economic worth, resonating with global preferences for culturally rooted products (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). While previous research has documented the cultural role of coffee in Toraja life (Neilson and Shonk, 2014; Rombe et al., 2021), this study advances these insights by situating cultural preservation within the broader value chain and demonstrating how it intersects with economic and environmental dimensions to sustain both identity and livelihoods (Muhammad et al., 2020).

However, this study also highlights the tension between modernization and the preservation of cultural heritage, a theme less explored in earlier works. While commercialization and integration into global markets offer economic opportunities, they also risk commodifying traditions and diluting their meanings (Toledo and Moguel, 2012). Practices such as standardized branding and mass production may undermine the cultural narratives that differentiate Toraja coffee (Neilson and Shonk, 2014; Wienhold and Goulao, 2023). However, this study shows that interventions such as storytelling, Geographical Indication (GI) certification, and culturally sensitive branding can help valorise cultural values without eroding their integrity. By embedding stories of heritage, rituals, and places in the marketing of Toraja coffee, these strategies enhance market appeal and price premiums (Giovannucci et al., 2012; Rombe et al., 2022). This integrative perspective advances beyond prior studies by demonstrating that cultural preservation and economic modernization can be mutually reinforced when carefully managed, providing a pathway for sustainable and inclusive development that respects the unique identity of Toraja coffee (Hakim, 2021).

4.5 Environmental sustainability

Farmers consistently described shade-based agroforestry as central to protecting soils, biodiversity, and microclimates, whereas observations confirmed that mixed cropping systems help buffer against erosion and climate variability. However, they also noted that land expansion and declining shade cover are emerging threats. These insights reinforce the wider debates on how smallholder systems balance intensification with ecological conservation (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019; Tscharntke et al., 2011). In Toraja, however, ecological stewardship is not an external agenda but a lived practice embedded in the farming traditions and local knowledge.

The Toraja Arabica coffee value chain illustrates how economic, cultural, and ecological dimensions intersect to sustain smallholder livelihoods and enhance specialty market competitiveness. Similar to smallholder chains in Africa and Latin America, challenges such as weak bargaining power and environmental risks persist; however, Toraja stands out for its integration of cultural heritage and agroecological stewardship. Coffee provides a vital source of income in highland areas (Rico et al., 2024a) and serves as a symbol of identity, hospitality, and heritage embedded in rituals and social life (Bigalke, 2006; Rahardjo et al., 2020; Rombe et al., 2021). Traditional shade-grown agroforestry not only preserves biodiversity and supports climate resilience (Agnoletti et al., 2022; Sudomo et al., 2023; Toledo and Moguel, 2012) and enhances bean quality, which attracts premium prices (Giovannucci et al., 2012) (Musa et al., 2020). These interdependencies demonstrate that sustainable interventions must go beyond productivity gains and protect the cultural and ecological assets that underpin resilience and differentiation in global markets.

However, the study also identified growing threats to these environmental benefits, including land-use change, declining shade tree cover, and unsustainable practices. As farmers seek to expand production or adopt intensive methods to meet global demand, they reduce tree diversity, overexploit soils, and undermine the ecological integrity of agroforests (Leakey and Van Damme, 2014; Neilson and Shonk, 2014; Wienhold and Goulao, 2023). These trends mirror the concerns raised in earlier research on the trade-offs between intensification and cisbronservation in tropical agroecosystems (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019; Tscharntke et al., 2011; Vaast and Somarriba, 2014). This study contributes to the literature by emphasizing the need to balance productivity gains with ecological stewardship, highlighting how policies and interventions that support traditional practices, such as promoting sustainable shade management, providing incentives for biodiversity-friendly practices, and strengthening local knowledge, can sustain environmental and economic outcomes (Lisnawati et al., 2017). By situating Toraja coffee within the dual challenge of intensification and conservation, this study underscores the value of maintaining agroecological approaches as a foundation for resilient and sustainable value chains (Rombe et al., 2022).

4.6 Roles and interactions of key actors

The interviews underscored PT Toarco Jaya's dual role: while it provides farmers with training and access to international markets, it also acts as a gatekeeper that controls quality and branding. Farmers appreciated this support but voiced concerns regarding dependence. Although limited by resources and governance challenges, cooperatives remained central to aspirations for stronger bargaining power. Government officials emphasized the importance of certification and infrastructure but admitted that initiatives were fragmented. Supporting actors, such as NGOs, research institutions, and financial providers, were also recognized as important but inconsistent in their engagement. This fragmentation reinforces earlier critiques of institutional silos and highlights the need for stronger coordination to achieve inclusive development (Siems et al., 2023).

The findings further show that farmers, cooperatives, companies, and consumers interact to create both synergies and tensions. Opportunities identified in the field, such as sustainable land use, stronger cooperative capacity, infrastructure upgrades, and culturally rooted branding, are best pursued as interconnected strategies rather than isolated interventions. Mechanisms such as storytelling and direct farmer–consumer links were repeatedly described in interviews as key to building trust and loyalty, illustrating how local aspirations align with global market preferences.

Therefore, the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain is shaped by the interdependent roles of its actors. Farmers form the backbone of production, cultivating coffee while sustaining its ecological and cultural heritage (Irmayani and Ambar, 2024) however, their ability to capture value is often constrained by limited resources and market access (Rico et al., 2024a). Cooperatives act as intermediaries by organizing production, facilitating training, and supporting certification, although resource shortages and governance issues reduce their effectiveness PT Toarco Jaya bridges local production and international markets through quality control, branding, and exports. However, its dominance can restrict farmer autonomy (Paitung et al., 2025; Salam et al., 2021). Government institutions contribute through policies, infrastructure, and certification support; however, their impact remains limited by underfunding and program fragmentation (Sia et al., 2025; Uria, 2021). Finally, consumers in Japan, Europe, and North America drive the demand for high-quality, sustainable, and culturally authentic coffee, incentivizing premium pricing and ethical practices (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). While previous studies have noted these individual roles (Neilson and Shonk, 2014), this study shows how their interactions collectively shape the inclusivity and sustainability of the value chain.

Beyond these primary actors, supporting stakeholders, such as research institutions, NGOs, and financial institutions, complement and strengthen the chain. Research institutions generate knowledge and innovations to improve cultivation, processing, and ecological management (Leakey and Van Damme, 2014; Millang et al., 2024). NGOs and development organizations promote sustainability programs, provide farmer training, and facilitate market access (Rombe et al., 2022), whereas financial institutions provide much-needed credit, insurance, and investment for farm improvements (Devaux et al., 2018; Horton et al., 2023). Together, these actors help to bridge resource gaps and foster innovation across chains. However, this study also underscores the institutional fragmentation that hampers effective coordination among these actors. Stakeholders often operate in silos, resulting in duplicated efforts, inefficiency, and missed opportunities for synergy (Mahadi, 2019; Sia et al., 2025). This finding aligns with earlier critiques of weak institutional frameworks in coffee-producing regions but contributes to a more nuanced understanding by identifying specific opportunities for collaboration and alignment (Siems et al., 2023). Strengthening networks, improving communication, and fostering shared goals among actors can enhance the resilience, equity, and competitiveness of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain.

4.7 Opportunities and strategic leverage points

The findings of this study reveal several actionable pathways to strengthen the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain, ensuring its sustainability and inclusivity, while enhancing farmers' participation in premium markets. One clear opportunity lies in the expansion of sustainable land use, as approximately 42,000 ha of suitable land is available for Arabica cultivation under environmentally friendly agroforestry (Lisnawati et al., 2017; Millang et al., 2024; Sia et al., 2025). Appropriate management can increase production without sacrificing biodiversity or ecosystem services (Hakim, 2021; Toledo and Moguel, 2012). Similarly, strengthening cooperatives and institutional support emergedrges as a critical leverage point, as better-organized cooperatives can improve farmers' bargaining power, coordinate quality standards, and facilitate access to inputs, training, and certifications (Busthanul et al., 2023; Musa et al., 2020; Panggabean et al., 2022; Salam et al., 2021). Investments in infrastructure, such as improved roads, storage, and processing facilities, can reduce post-harvest losses and enhance quality (Husain and Umami, 2023). Ongoing skill development in sustainable farming and post-harvest handling is essential to maintaining Toraja coffee's distinctive quality and reputation in global markets (Panggabean et al., 2022; Rico et al., 2024b). Certification schemes, including Geographical Indication (GI), organic, and fair trade, not only differentiate products, but also align with consumer preferences for authentic, ethical, and environmentally sustainable coffee, allowing farmers to capture higher value (Giovannucci et al., 2012; Marie-Vivien et al., 2014; Wahyudi and Jati, 2012).

Beyond these internal improvements, this study underscores the potential of direct farmer–consumer connections to deepen loyalty and improve value capture. Mechanisms such as storytelling, transparent branding, and direct trade relationships strengthen the emotional and ethical connections between producers and consumers, and foster willingness to pay premium prices for culturally rich and sustainably produced coffee (Connell et al., 2008; Rombe et al., 2022; Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). Unlike previous studies, which often examined these strategies in isolation, this study positions them as mutually reinforcing elements within an integrated value chain strategy (Rombe et al., 2021; Youngs, 2003). Finally, this study highlights the importance of aligning investments and interventions across actors, including farmers, cooperatives, private companies, governments, NGOs, and consumers, to enhance inclusivity and resilience. Coordinated efforts, rather than fragmented initiatives, can maximize synergies, avoid duplication, and ensure that economic, cultural, and environmental objectives are simultaneously addressed (Devaux et al., 2018; Learson, 2019; Sia et al., 2025; Siems et al., 2023; Well and Carrapatoso, 2017). By framing these opportunities as interconnected leverage points, this study extends existing literature by presenting a holistic roadmap for transforming the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain into a more equitable, sustainable, and competitive system.

4.8 Implications for policy and practice

This study underscores the importance of designing integrated strategies that simultaneously advance the economic, cultural, and environmental objectives of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain. While earlier studies tend to focus on singular aspects, such as improving farmers' income through certifications (Giovannucci et al., 2012), conserving biodiversity through agroforestry (Toledo and Moguel, 2012; Vaast and Somarriba, 2014), and documenting the cultural significance of coffee in Torajan rituals (Bigalke, 2006; Rombe et al., 2022), this study contributes a more holistic perspective, showing how these dimensions are interdependent and must be addressed collectively (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). Policymakers and practitioners promote initiatives that enhance livelihoods by strengthening cooperatives, upgrading infrastructure, and building farmers' skills, while at the same time safeguarding biodiversity and valorizing cultural heritage through storytelling and certifications (Rombe et al., 2022). Such strategies align with global consumer preferences for authentic, ethical, and environmentally sustainable products, and can enhance both the resilience and competitiveness of the value chain (Hakim, 2021).

Policy frameworks play a pivotal role in enabling cooperation among actors, facilitating certification, and protecting cultural heritage. Building on prior insights (e.g., Devaux et al., 2018; Siems et al., 2023; Wahyudi and Jati, 2012). This study shows how government agencies can foster inclusive development by investing in cooperatives and infrastructure, promoting Geographical Indication (GI) and fair-trade certifications, and safeguarding the intangible cultural practices embedded in Toraja coffee production. Integrated policies that align economic, ecological, and cultural priorities help reduce fragmentation and strengthen the incentives of stakeholders (Roldan et al., 2013). Approaches such as participatory planning, culturally informed branding, and agroecological knowledge can reconcile global market demands with local realities (Wienhold and Goulao, 2023).

However, the realization of these strategies faces structural obstacles. Farmer cooperatives often struggle with weak governance and limited managerial capacity, which constrains their ability to coordinate marketing or certification schemes. Smallholders encounter financial barriers, as the costs of certification, post-harvest improvements, or tree replanting often exceed their resources. Although government support is present, it remains uneven and fragmented, reducing policy coherence. Without addressing these institutional and financial constraints, sustainability initiatives risk remaining partial or short-lived, thereby limiting their transformative impact on the Toraja coffee value chain.

4.9 Limitation of the study

This study is limited by its qualitative, cross-sectional design, which while providing a rich and integrated understanding of the economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain, does not capture how these dynamics evolve over time. Building on previous studies that often examined these aspects in isolation (Rombe et al., 2021; Vaast and Somarriba, 2014), this study offers a more holistic perspective but remains context-specific and descriptive (Ros-Tonen et al., 2019). Future research should employ longitudinal and mixed-methods approaches to track the changing interactions among farmers, institutions, markets, and consumers, and explore how strategies that align global demands with local knowledge and traditions can be sustained and replicated in other coffee-producing regions (Mahadi, 2019; Wienhold and Goulao, 2023). As this study relied on self-reported data from interviews and FGDs, there is a potential for recall or social desirability bias; however, ethical safeguards, including confidentiality assurances and voluntary participation, were applied to minimize these risks.

5 Conclusion and policy recommendation

This study demonstrates that the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain operates as an integrated system in which economic, cultural, and environmental dimensions are closely interwoven. Field evidence revealed persistent challenges including weak farmer bargaining power, quality inconsistencies, limited infrastructure, and risks of cultural and ecological erosion. At the same time, the study highlights opportunities for strengthening sustainability through cooperatives, certification schemes, agroforestry practices, cultural storytelling, and improved market linkages. Beyond these empirical findings, the research offers new scientific contributions by advancing a holistic analytical framework that explicitly integrates the economic, cultural, and environmental aspects of a value chain rather than treating them as separate domains. Methodologically, the application of triangulation across data sources, methods, and theoretical perspectives provides robust validation and a richer understanding of how sustainability challenges and opportunities manifest across multiple stakeholders. By affirming the interdependence of these dimensions, the study contributes to sustainability science and agrifood value chain research, while offering practical insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking inclusive and culturally grounded pathways for rural development.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon reasonable request and without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

All participants involved in this study, including those in the focus group discussions (FGDs) and interviews, provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Author contributions

RAz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. RD: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. AA: Data curation, Visualization, Software. SS: Data curation, Visualization, Software. MK: Writing – review & editing, Validation. HA: Writing – review & editing, Validation. RAm: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Project administration. PA: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the village head and staff of Desa Ampekale, who facilitated the FGD, and to all individuals and groups who contributed valuable insights and information to this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used generative AI tools to enhance the clarity and readability of the text. These tools were employed solely to improve language and presentation. All AI-assisted content was carefully reviewed, edited, and validated by the author(s) to ensure accuracy, completeness, and alignment with the research objectives. The author(s) accept full responsibility for the originality, accuracy, and integrity of the final work.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Addoah, T., Lyons-White, J., Cammelli, F., Kouakou, K. M. P., Carodenuto, S., Thompson, W. J., et al. (2025). Is the implementation of Cocoa Companies' forest policies on track to effectively and equitably address deforestation in West Africa? Sustain. Dev. 33, 5197–5213. doi: 10.1002/sd.3380

Agnoletti, M., Pelegrín, Y. M., and Alvarez, A. G. (2022). The traditional agroforestry systems of Sierra del Rosario and Sierra Maestra, Cuba. Biodivers. Conserv. 31, 2259–2296. doi: 10.1007/s10531-021-02348-8

Amoah, A., and Addoah, T. (2021). Does environmental knowledge drive pro-environmental behaviour in developing countries? Evidence from households in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 2719–2738. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00698-x

Bigalke, T. W. (2006). Review of ‘Tana Toraja: A Social History of an Indonesian People'. D. ROTH Published by: Brill Stable, 162.

Busthanul, N., Demmallino, E. B., Sultani, H. R., Lampe, M., Ismail, A., Yassi, A., et al. (2023). Ecological adaptation of smallholders to tropical climate change in the highland zone of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 24, 5328–5335. doi: 10.13057/biodiv/d241014

Connell, D. J., Smithers, J., and Joseph, A. (2008). Farmers' markets and the good “food” value chain: a preliminary study. Local Environ. 13, 169–185. doi: 10.1080/13549830701669096

Dekens, J., and Bagamba, F. (2014). Promoting an Integrated Approach to Climate Adaptation?: Lessons From the Coffee Value Chain in Uganda. Climate and Development Knowledge Network; International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Devaux, A., Torero, M., Donovan, J., and Horton, D. (2018). Agricultural innovation and inclusive value-chain development: a review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 8, 99–123. doi: 10.1108/JADEE-06-2017-0065

Giovannucci, D., Josling, T. E., Kerr, W. A., O'Connor, B., and Yeung, M. T. (2012). Guide to geographical indications: linking products and their origins (summary). SSRN Electron. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1736713

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Hakim, L. (2021). Coffee: ethnobotany, tourism and biodiversity conservation in East Java. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 743:12063. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/743/1/012063

Haverhals, M., Ingram, V., Elias, M., Basnett, B. S., and Petersen, S. (2016). Exploring Gender and Forest, Tree and Agroforestry Value Chains: Evidence and Lessons From a systematic Review. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 1–6. doi: 10.17528/cifor/006279

Horton, D., Devaux, A., Bernet, T., Mayanja, S., Ordinola, M., and Thiele, G. (2023). Inclusive innovation in agricultural value chains: lessons from use of a systems approach in diverse settings. Innov. Dev. 13, 517–539. doi: 10.1080/2157930X.2022.2070587

Husain, A. S., and Umami, L. (2023). Competitiveness of Toraja specialty coffee in the global market: porters diamond model. E3S Web Conf. 444:14. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202344402037

Irmayani, I., and Ambar, A. A. (2024). Strengthening local values of Arabica Coffee Farming in the Rural Area of Mount Latimojong, South Sulawesi. J. AGRIKAN 17, 330–338. doi: 10.52046/agrikan.v17i2.2272

Jha, A. (2020). Global goals and local institutions: understanding PRIs in the context of sustainable development goals. SOCRATES 8, 18–24. doi: 10.5958/2347-6869.2020.00003.5

Leakey, R., and Van Damme, P. (2014). The role of tree domestication in green market product value chain development. Forests Trees Livelihoods 23, 116–126. doi: 10.1080/14728028.2014.887371

Leakey, R. R. B. (2014). The role of trees in agroecology and sustainable agriculture in the tropics. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 52, 113–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045838

Learson, E. M. (2019). Civic and religious education in Manado, Indonesia: ethical deliberation about plural coexistence. Sustainability 11, 1–14. Available online at: https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/f59c816a-cdc9-37c6-92e1-c82f721be5af/

Lisnawati, A., Lahjie, A. M., Simarangkir, B. D. A. S., Yusuf, S., and Ruslim, Y. (2017). Agroforestry system biodiversity of Arabica coffee cultivation in North Toraja district, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 18, 741–751. doi: 10.13057/biodiv/d180243

Mahadi, R. (2019). The role and the process of institutional entrepreneurship in the implementation of accrual accounting by the Malaysian Federal Government. Sustainability 11.

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., and Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 26, 1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444

Marie-Vivien, D., Garcia, C. A., Kushalappa, C. G., and Vaast, P. (2014). Trademarks, geographical indications and environmental labelling to promote biodiversity: the case of agroforestry coffee in India. Dev. Policy Rev. 32, 379–398. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12060

Millang, S., Yuniati, E., Paembonan, S. A., Arty, B., and Makkasau, A. R. (2024). Ethnobotany of the Kombong Agroforestry System and Tongkonan conservation in the Toraja Tribe, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. For. Soc. 8, 271–295. doi: 10.24259/fs.v8i1.31156

Muhammad, H., Prasuri, K., and Masdiana, M. (2020). Toraja Coffee as Tourism Identity: Perception of Foreign Tourists. International Trade Center. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1736713

Musa, Y., Darma, R., and Panggabean, Y. B. S. (2020). Strategy to increase selling price of organic Toraja Arabica coffee at farmers levels in International Markets. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 473:12043. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/473/1/012043

Neilson, J. (2008). Global private regulation and value-chain restructuring in Indonesian smallholder coffee systems. World Dev. 36, 1607–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.09.005

Neilson, J., and Shonk, F. (2014). Chained to development? Livelihoods and global value chains in the coffee-producing Toraja region of Indonesia. Aust. Geograph. 45, 269–288. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2014.929998

Paitung, R. V. P., Saleh, M. Y., and Said, M. (2025). Pengaruh Harga, Volume Produksi Dan Kualitas Ekspor Terhadap Daya Saing Kopi Toraja Pada PT Toarco Jaya. J. Econ. Bus. Dev. 3, 118–126. doi: 10.56326/jebd.v3i1.2669

Panggabean, Y. B. S., Arsyad, M., and Mahyuddin, Nasaruddin. (2022). Sustainability agricultural supply chain in improving the welfare of North Toraja Arabica coffee farmers. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 1107:12065. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1107/1/012065

Rahardjo, B., Akbar, B. M. B., Iskandar, Y., and Shalehah, A. (2020). Analysis and strategy for improving Indonesian coffee competitiveness in the international market. BISMA 12:154. doi: 10.26740/bisma.v12n2.p154-167

Rico, D. R., and Salman, D.. (2024a). Examining the effect of agribusiness actors' performance on the performance of Arabica Coffee Agribusiness Subsystem in North Toraja Regency. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 19, 1471–1484. doi: 10.18280/ijsdp.190424

Rico, D. R., and Salman, D.. (2024b). The performance of Arabica coffee agribusiness actors in North Toraja Regency, Indonesia. Cogent Food Agric. 10:2363002. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2024.2363002

Roldan, M. B., Fromm, I., and Aidoo, R. (2013). From producers to export markets: the case of the Cocoa value chain in Ghana. J. Afr. Dev. 15:121. doi: 10.5325/jafrideve.15.2.0121

Rombe, O. S. C., Ching, G. H., and Ali, Z. M. (2021). A sustainable value of vernacular architecture and coffee culture for coffee value chain with case study Toraja. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 794:12189. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/794/1/012189

Rombe, O. S. C., Goh, H. C., and Ali, Z. M. (2022). Toraja cultural landscape: Tongkonan vernacular architecture and Toraja coffee culture. ETropic 21, 99–142. doi: 10.25120/etropic.21.1.2022.3822

Ros-Tonen, M. A., Bitzer, V., Laven, A., Ollivier de Leth, D., Van Leynseele, Y., and Vos, A. (2019). Conceptualizing inclusiveness of smallholder value chain integration. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 41, 10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.08.006

Salam, M., Viantika, N. M., Amiruddin, A., Pinontoan, F. M., and Rahmatullah, R. A. (2021). Value chain analysis of Toraja coffee. IOP Con. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 681:12115. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/681/1/012115

Sia, R., Darma, R., Salman, D., and Riwu, M. (2025). Sustainability assessment of the Arabica coffee agribusiness in North Toraja: insight from a multidimensional approach. Sustainability 17:2169. doi: 10.3390/su17052167

Siems, E., Seuring, S., and Schilling, L. (2023). Stakeholder roles in sustainable supply chain management: a literature review. J. Bus. Econ. 93, 747–775. doi: 10.1007/s11573-022-01117-5

Sudomo, A., Leksono, B., Tata, H. L., Rahayu, A. A. D., Umroni, A., Rianawati, H., et al. (2023). Can agroforestry contribute to food and livelihood security for Indonesia's smallholders in the climate change era? Agriculture 13:1896. doi: 10.3390/agriculture13101896

Toledo, V. M., and Moguel, P. (2012). Coffee and sustainability: the multiple values of traditional shaded coffee. J. Sustain. Agric. 36, 353–377. doi: 10.1080/10440046.2011.583719

Tscharntke, T., Clough, Y., Bhagwat, S. A., Buchori, D., Faust, H., Hertel, D., et al. (2011). Multifunctional shade-tree management in tropical agroforestry landscapes - a review. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 619–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01939.x

Uria, D. (2021). Index Kepuasan Bermitra Petani Kopi Arabika di Desa Uma, Kabupaten Toraja Utara. Sosio Agri Papua 10, 96–101. doi: 10.30862/sap.v10i1.124

Vaast, P., and Somarriba, E. (2014). Trade-offs between crop intensification and ecosystem services: the role of agroforestry in cocoa cultivation. Agrofor. Syst. 88, 947–956. doi: 10.1007/s10457-014-9762-x

Wahyudi, T., and Jati, M. (2012). Challenges of Sustainable Coffee Certification in Indonesia. London: ICO Seminar on the Economic ICO Seminar.

Well, M., and Carrapatoso, A. (2017). REDD+ finance: policy making in the context of fragmented institutions. Clim. Policy 17, 687–707. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2016.1202096

Wienhold, K., and Goulao, L. F. (2023). The embedded agroecology of coffee agroforestry: a contextualized review of smallholder farmers' adoption and resistance. Sustainability 15:6827. doi: 10.3390/su15086827

Keywords: Toraja coffee, coffee certification, sustainable value chains, smallholder resilience, agroecology

Citation: Azkar R, Darma R, Amir AA, Syam SH, Kasim M, Bakheet Ali HN, Amandaria R and Astaman P (2025) Sustainability of the Toraja Arabica coffee value chain in Indonesia: economic, cultural, environmental, and certification dimensions. Front. Sustain. 6:1691977. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1691977

Received: 25 August 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Accepted: 11 November 2025; Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Lipan Feng, South China University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Noel Kishaija, University of West Hungary, HungarySupramono Supramono, Satya Wacana Christian University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Azkar, Darma, Amir, Syam, Kasim, Bakheet Ali, Amandaria and Astaman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rahim Darma, cmRhcm1hQHVuaGFzLmFjLmlk

Riad Azkar1

Riad Azkar1 Rahim Darma

Rahim Darma