- Department of Accounting and Finance, University of West Attica, Ancient Olive Grove Campus, Egaleo, Greece

Background: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has evolved from a peripheral philanthropic activity into a strategic necessity, particularly in recovering economies where social trust and consumer confidence are fragile. Generation Z, shaped by economic turbulence and heightened social awareness, increasingly demands transparency and ethical integrity from corporations. Yet, despite growing CSR awareness, little is known about how communication and trust translate that awareness into ethical consumer behavior in such contexts.

Objective: This study aimed to examine how CSR awareness, communication, and trust influence the ethical consumerism of Generation Z in a recovering economy, focusing on the mechanisms through which awareness transforms into loyalty and advocacy.

Methods: A quantitative research design was employed using a structured questionnaire administered to 322 Generation Z consumers in Greece. Descriptive and inferential analyses, including exploratory factor analysis and multiple regression models, were conducted to evaluate the relationships among CSR awareness, communication, trust, and ethical purchasing behavior. The study integrated the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Social Identity Theory (SIT) to interpret how attitudes, social norms, and identity alignment shape consumer choices.

Results: Findings reveal that while CSR awareness among Generation Z is moderate, participation in formal CSR education is low. Despite this limited depth of knowledge, respondents strongly perceive CSR as beneficial to society and the. Regression analyses demonstrate that CSR awareness significantly predicts consumer, while communication positively influences trust and transparency reinforced through NGO partnerships enhances credibility. Simplified CSR messaging also contributes to ethical consumerism by improving comprehension.

1 Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has evolved from peripheral philanthropic activity to a strategic imperative, reflecting shifting societal expectations and increasing demands for corporate accountability (Carroll, 2008; Werther and Chandler, 2011; Banerjee, 2008). In recovering economies, where financial constraints, institutional fragility, and socio-political uncertainty exacerbate consumer skepticism, CSR assumes a heightened role in rebuilding trust and fostering sustainable relationships between firms and consumers (Skouloudis et al., 2011; Ringov and Zollo, 2007). Within this environment, Generation Z emerges as a transformative consumer group whose purchasing behavior is deeply shaped by digital connectivity, social values, and demands for authenticity in corporate communication (Chatzopoulou, 2020; McKinsey & Company, 2022; Deloitte, 2021).

Generation Z holds a dual identity: as a vulnerable cohort shaped by global crises and economic turbulence, and as a socially conscious group capable of reshaping market dynamics through values-driven consumption (Harrison et al., 2020; Kagaba, 2025). Research indicates that they are more likely to support firms whose CSR aligns with their ethical beliefs while showing low tolerance for superficial or inconsistent messaging (Sen and Bhattacharya, 2001; Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2009). In recovering economies such as Greece, where austerity and declining purchasing power have altered consumer priorities, examining CSR awareness, communication, and trust becomes vital to understanding the mechanisms that drive ethical consumerism (Skouloudis et al., 2011; Pomering and Dolnicar, 2009).

This study employs Ajzen's (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Tajfel and Turner's (1979) Social Identity Theory (SIT) as complementary frameworks. TPB posits that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control determine behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Armitage and Conner, 2001). In CSR contexts, favorable attitudes toward CSR, coupled with social norms and perceived consumer efficacy, increase the likelihood of ethical purchasing (Rozenkowska, 2023; Djafarova and Foots, 2022). Extensions of TPB incorporating moral norms and identity show that ethical consumption is also values-driven (Carrington et al., 2010; Gregory-Smith et al., 2013). This is especially relevant for Generation Z, whose consumer identity is grounded in environmentalism, social justice, and inclusivity (Heim, 2022; Kozlowski et al., 2020).

SIT, meanwhile, emphasizes that individuals derive self-concepts from social group memberships and reinforce them through consumption (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Brown and Dacin, 1997). Brands thus act as identity markers, and CSR initiatives signal alignment with group values (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2004; Guzmán and Davis, 2017). When CSR resonates with consumer identities, it fosters trust, advocacy, and consumer–company identification (Huang et al., 2017; Agyei et al., 2021). For Generation Z, this process is magnified through digital ecosystems where identity-driven brand associations are cultivated (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010; Etter et al., 2019).

The convergence of TPB and SIT underscores the mediating role of trust and authenticity in translating CSR awareness into consumer behavior. Trust reduces uncertainty about CSR claims (Swaen and Chumpitaz, 2008; Fatma et al., 2015), while authenticity reinforces symbolic alignment with consumer identities (Afzali and Kim, 2021; Safeer and Liu, 2023). Studies confirm that insincere CSR—often dismissed as greenwashing—erodes credibility (Delmas and Burbano, 2011; Lyon and Montgomery, 2015), whereas transparency and third-party verification strengthen trust (Parguel et al., 2011; Marschlich and Hurtado, 2025).

In recovering economies, these dynamics are amplified. Economic instability heightens skepticism and constrains ethical choices, prioritizing affordability (Nakagawa and Shaw, 2004; Min and Arif, 2022). For Generation Z, CSR thus serves both as a symbolic resource affirming identity and as a practical framework reducing uncertainty in decision-making (Mohr et al., 2005; Šálková et al., 2023). Yet, research indicates that awareness often remains superficial, limiting CSR's influence on behavior (Pomering and Dolnicar, 2009; Wekesa, 2024). This elevates the role of communication strategies: simplified and relatable messaging enhances comprehension (Morsing and Schultz, 2006; Wan Afandi et al., 2021), while partnerships with credible stakeholders reinforce authenticity (Du et al., 2010; Taofeek, 2024).

Accordingly, this study investigates how CSR awareness, communication, and trust shape Generation Z's ethical consumerism in recovering economies. By combining descriptive statistics and regression analysis, it examines how awareness evolves into advocacy and purchasing, and how communication mediates this process. Conceptually, the integration of TPB and SIT shows that CSR awareness offers the evaluative foundation, communication activates engagement, and trust validates authenticity and identity alignment. Practically, CSR awareness alone is insufficient—transparent, credible, and accessible communication is essential to foster ethical consumerism (Ali et al., 2023; Deep, 2023). The study contributes by situating ethical consumption within post-crisis contexts and identifying Generation Z as both a driver and a filter of responsible corporate behavior.

2 Materials and methods

The methodology of this study was designed to systematically examine the relationship between CSR awareness, communication, and trust, and their influence on the ethical consumerism of Generation Z within the context of a recovering economy. A quantitative research approach was employed, using a structured questionnaire as the primary instrument for data collection. The questionnaire was administered to a sample of 322 respondents belonging to Generation Z in Greece, a demographic chosen for its distinct social consciousness and growing importance as a consumer group in shaping responsible market practices. This context was considered particularly relevant given the increasing role of CSR in rebuilding trust and consumer engagement in post-crisis economies.

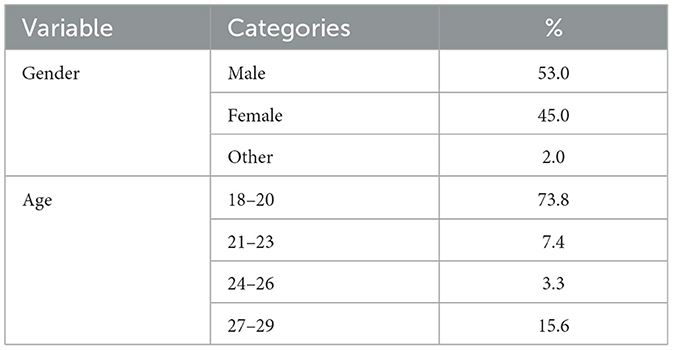

The questionnaire was structured into multiple sections in order to capture a wide range of data. The first section gathered demographic information, including age, gender, and education, in order to situate consumer patterns within socio-economic profiles. Subsequent sections explored CSR awareness, familiarity with CSR principles and certifications, and engagement with CSR-related educational initiatives. Additional sections focused on consumer perceptions of CSR's social and environmental impacts, trust in corporate initiatives, and behavioral outcomes such as product choices, loyalty, and advocacy. A combination of closed-ended and Likert-scale questions was used to ensure both categorical and scaled responses, thereby enabling descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. Participants were assured of the voluntary nature of participation and guaranteed anonymity, resulting in a balanced and diverse sample.

Data were initially processed using Microsoft Excel for organization and cleaning, while IBM SPSS Statistics was used to conduct the statistical analysis. Reliability and validity were ensured through the application of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and Cronbach's alpha, which confirmed the internal consistency of the constructs. Factor structures were further validated through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity. Following the extraction of factors, regression models were employed to test hypotheses concerning the impact of CSR awareness, communication, and transparency on trust, loyalty, and ethical consumerism. For example, regression analyses explored how simplified communication strategies enhanced comprehension, how NGO partnerships reinforced perceived authenticity, and how CSR awareness directly influenced consumer loyalty.

In addition to regression analysis, descriptive statistics were used to capture overall trends in CSR awareness and engagement, while inferential statistics provided insights into the strength and direction of the relationships between constructs. The statistical significance threshold was set at p ≤ 0.05, and only results meeting this criterion were considered in the final interpretation. This systematic and rigorous methodological approach ensured the reliability of the study and enabled the identification of the mechanisms through which CSR awareness, communication, and trust shape the ethical consumerism of Generation Z in a recovering economy.

The empirical results provide an in-depth understanding of how CSR awareness, communication, and trust shape the ethical consumerism of Generation Z in the context of a recovering economy. The demographic composition of the sample (Table 1) underscores the relevance of this cohort: with nearly three-quarters of respondents aged 18–20, the data represent the youngest segment of Generation Z, whose consumer behavior is still forming but already deeply influenced by social and environmental concerns. The predominance of younger respondents also amplifies the importance of CSR communication strategies, as this demographic is more digitally connected and more responsive to corporate transparency compared to older generations.

2.1 CSR awareness and education

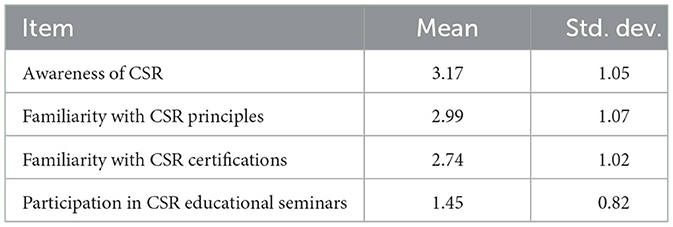

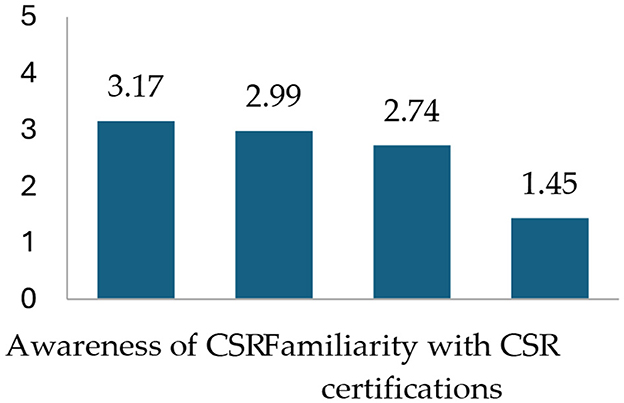

The results concerning CSR awareness reveal a contradictory situation. While participants report a moderate familiarity with CSR (mean = 3.17), deeper knowledge of CSR principles (mean = 2.99) and international certifications (mean = 2.74) remains limited (Table 2). The exceptionally low rate of participation in CSR-related educational seminars (mean = 1.45) suggests that awareness is largely derived from informal sources such as digital media and peer networks rather than structured educational programs. From an analytical perspective, this gap is critical: CSR awareness functions as a necessary but not sufficient condition for ethical consumerism. Without systematic educational engagement, awareness risks remaining superficial, unable to consistently translate into informed consumer action.

2.2 Perceived impact of CSR on society and environment

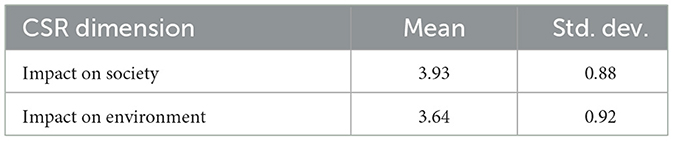

Despite the limitations of formal education, the data indicate that Generation Z strongly perceives CSR as a force for positive change. As shown in Table 3, the perceived social benefits of CSR (mean = 3.93) outweigh environmental contributions (mean = 3.64). This discrepancy reflects the socio-economic realities of recovering economies: immediate concerns about social justice, employment, and equity take precedence over long-term ecological issues. The visual distribution of these perceptions is illustrated in Figure 1, which highlights that while environmental awareness remains significant, social impact is perceived as more immediate and meaningful among respondents.

2.3 Consumer engagement and advocacy

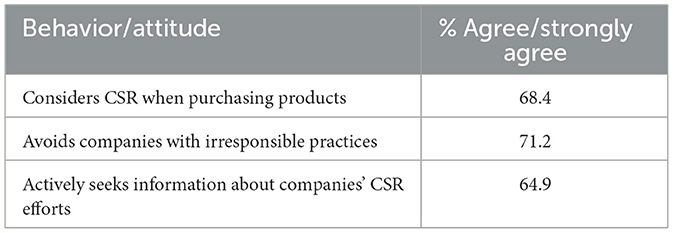

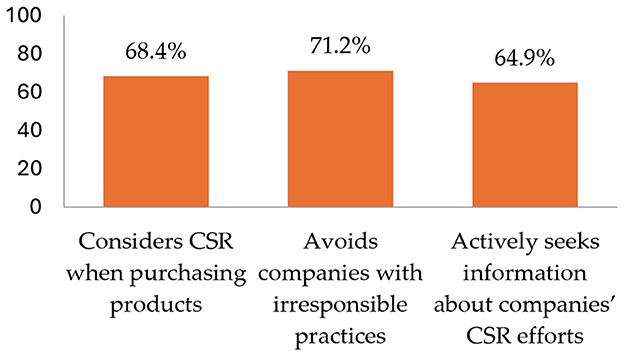

The behavioral findings (Table 4) provide evidence that CSR awareness extends beyond passive recognition to active consumer choices. More than two-thirds of respondents report considering CSR in their purchasing decisions, while a similar proportion actively avoid companies with irresponsible practices. This behavioral tendency is clearly depicted in Figure 2, which demonstrates the extent to which Generation Z consumers translate CSR awareness into practical engagement. The high level of interest in accessing CSR information underscores the demand for transparency and confirms that ethical engagement is not merely attitudinal but behaviorally enacted in purchasing contexts. This pattern demonstrates that Generation Z not only perceives CSR as relevant but also implements it in market behavior. Importantly, the high level of interest in accessing CSR information underscores the demand for transparency.

2.4 Regression analysis: the mediating role of communication and trust

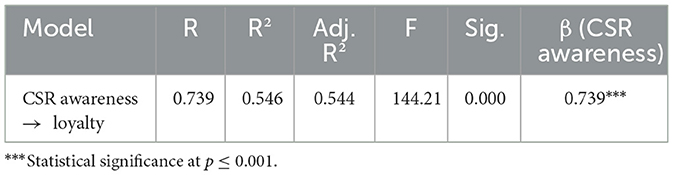

The regression results provide robust evidence that CSR awareness, communication, and trust are not independent variables but parts of an interconnected system that drives ethical consumerism among Generation Z. The first model (Table 5) demonstrates the direct influence of CSR awareness on loyalty and ethical orientation, with an exceptionally high standardized coefficient (β = 0.739) and variance explained (R2 = 0.546). This result confirms that awareness alone is a powerful predictor of consumer loyalty, validating the Theory of Planned Behavior's proposition that attitudes directly shape behavioral intentions. However, the magnitude of this effect also suggests that awareness functions as a foundational construct: it equips consumers with the evaluative framework through which they interpret corporate practices, but it does not fully account for the processes that translate intention into consistent action.

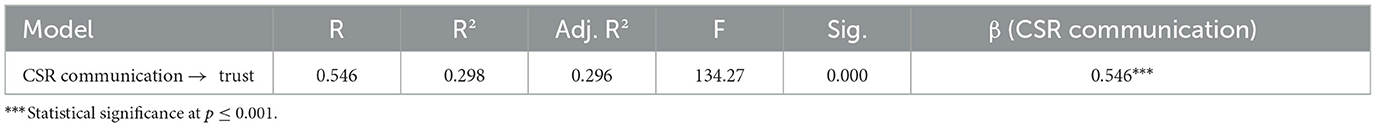

The subsequent models illuminate these mediating processes. CSR communication (Table 6) significantly predicts trust (β = 0.546, R2 = 0.298), highlighting communication as more than an informational conduit. Effective communication strategies create meaning, enhance transparency, and foster emotional resonance, which in turn consolidate trust. In recovering economies, where consumer skepticism is heightened due to corporate misconduct and financial instability, communication becomes a decisive factor in transforming awareness into confidence. The relatively lower R2 compared to the awareness model also suggests that communication alone cannot drive consumer outcomes without the groundwork of prior awareness, but it is indispensable in strengthening relational trust.

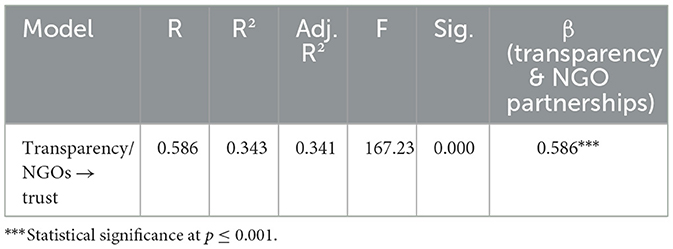

Trust is further reinforced through credibility mechanisms such as transparency and partnerships with NGOs (Table 7). The positive and significant association (β = 0.586, R2 = 0.343) demonstrates that external validation is critical in contexts where authenticity is questioned. NGO partnerships serve as third-party endorsements, mitigating concerns about “greenwashing” and aligning corporate initiatives with socially trusted actors. This finding resonates with Social Identity Theory, as external validation strengthens the symbolic alignment between consumer identity and corporate values, thereby reinforcing consumer–company identification.

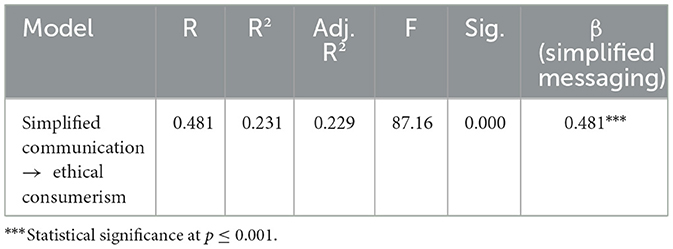

Finally, simplified CSR messaging emerges as a practical enabler of behavioral change (Table 8). While its explanatory power (R2 = 0.231) is lower than that of awareness or credibility mechanisms, its role should not be underestimated. By reducing cognitive barriers and enhancing comprehension, simplified communication increases perceived behavioral control—a key determinant in the Theory of Planned Behavior. This indicates that consumers are more likely to act on their ethical preferences when CSR information is clear, accessible, and framed in relatable terms.

The comparative visualization (Figure 3) illustrates these dynamics. CSR awareness exerts the strongest direct influence on loyalty, but communication, trust, and simplified messaging each play complementary roles that amplify and sustain ethical consumerism. Together, these findings point to a layered process: awareness establishes the evaluative foundation, communication shapes trust, credibility mechanisms authenticate corporate claims, and simplified messaging empowers consumers to act. Without this sequence, awareness risks remaining superficial, communication risks being perceived as rhetoric, and trust risks erosion. With these mediators in place, however, CSR becomes not only an attitudinal preference but a driver of concrete consumer behavior in recovering economies.

3 Discussion

The findings of this study confirm the centrality of CSR awareness, communication, and trust in shaping the ethical consumerism of Generation Z in a recovering economy. What emerges is not only a descriptive account of attitudes and behaviors but also a theoretical clarification of how psychological mechanisms and identity-based processes interact in the domain of ethical consumption. The results provide strong support for the predictive capacity of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) while also affirming the explanatory value of Social Identity Theory (SIT), particularly in clarifying the symbolic and relational dimensions of CSR.

From a TPB perspective, the significant association between CSR awareness and both ethical standards and brand loyalty highlights the role of attitudes as determinants of behavioral intention. Generation Z respondents who report higher levels of awareness also display a stronger commitment to socially responsible brands, thereby aligning with Ajzen's (1991) proposition that favorable attitudes increase the likelihood of corresponding behavior. Furthermore, the emphasis on communication as a determinant of trust and engagement reinforces the importance of subjective norms. Communication does not merely convey information but also signals social approval, shaping consumers' perception of what is expected by their peer group and society at large. Finally, the finding that simplified messaging enhances comprehension points to the importance of perceived behavioral control. When CSR information is accessible and relatable, consumers feel more capable of acting on their ethical preferences, reducing the intention–behavior gap that often undermines socially responsible consumption.

SIT enriches this analysis by demonstrating how CSR functions as an identity resource for Generation Z. The positive association between CSR awareness, advocacy, and purchasing behavior indicates that CSR is more than an evaluative criterion; it is a marker of self-concept and group belonging. By avoiding products from irresponsible companies and actively seeking CSR information, consumers affirm their identification with values such as fairness, sustainability, and accountability. This resonates with Tajfel and Turner's (1979) argument that group membership shapes self-definition and behavior. CSR activities that align with Gen Z's values serve to strengthen consumer–company identification, fostering loyalty and advocacy. Conversely, when CSR communication lacks transparency or authenticity, identification is weakened, and trust collapses, reflecting the fragility of brand–consumer relationships in the presence of perceived inconsistency.

The integration of TPB and SIT is particularly useful in explaining the mediating role of trust. From the standpoint of TPB, trust reduces uncertainty and increases perceived control, encouraging consumers to act in line with their ethical attitudes. From the SIT perspective, trust validates the alignment between consumer identity and corporate values, reinforcing the symbolic link that underpins loyalty and advocacy. The regression results that emphasize the importance of NGO partnerships and transparent communication confirm this dual role: by providing external validation, NGOs enhance perceived control over consumption decisions and simultaneously reinforce the identity alignment between consumer values and brand practices.

The study's findings also advance the broader discourse on CSR in recovering economies. Previous literature has often assumed that CSR models developed in affluent markets are universally applicable. However, the evidence here suggests that in contexts marked by economic insecurity, CSR perceptions are filtered through a heightened sensitivity to authenticity and a stronger emphasis on immediate social issues relative to long-term environmental concerns. The finding that respondents rated CSR's societal impact higher than its environmental contribution illustrates how socio-economic realities shape the salience of CSR dimensions. For Generation Z in recovering economies, ethical consumerism is not a luxury but a means of affirming collective resilience and social justice in contexts of structural vulnerability.

These insights also highlight the paradox of Generation Z consumer behavior: while awareness and advocacy are strong, participation in formal CSR education remains low, and affordability constraints continue to moderate actual purchasing behavior. This paradox underscores the persistent intention–behavior gap noted in the literature (Mohr et al., 2005; Bhattacharya and Sen, 2004). The present analysis suggests that the gap can be narrowed not only through better education but also through communication strategies that enhance trust and simplify CSR narratives. In this sense, the results lend empirical support to recent arguments that communication is not peripheral to CSR but constitutive of its impact (Pomering and Johnson, 2009).

In sum, the discussion confirms that Generation Z is both a driver and a filter of CSR in recovering economies. They are drivers because their expectations and behaviors compel companies to integrate CSR authentically into their strategies. They are filters because their skepticism and demand for transparency force companies to demonstrate credibility before trust is granted. The combination of TPB and SIT provides a comprehensive framework for explaining this dual role, demonstrating that ethical consumerism is shaped by the interplay of attitudes, norms, control perceptions, and identity processes, all mediated by the trustworthiness of corporate communication.

4 Theoretical and practical implications

The study offers valuable insights into the relationship between CSR awareness, communication, and trust among Generation Z in a recovering economy, yet it is not without limitations. On the theoretical level, the research primarily draws upon the Theory of Planned Behavior and Social Identity Theory, both of which provide a strong explanatory framework for ethical consumerism but remain somewhat constrained in capturing the broader socio-economic and cultural complexities that influence consumer decisions in post-crisis contexts. While these models highlight attitudes, perceived control, and identity alignment, they do not fully account for structural factors such as unemployment, inflation, or institutional trust deficits, which may significantly shape consumer behavior in recovering economies. Moreover, the study's reliance on self-reported perceptions and intentions introduces the well-documented intention–behavior gap, leaving open the possibility that actual purchasing practices diverge from stated preferences due to affordability constraints or market availability. Another theoretical limitation lies in the treatment of CSR as a relatively uniform construct; although the paper distinguishes between awareness, communication, and trust, it does not deeply interrogate how different dimensions of CSR—such as environmental vs. social initiatives—may carry unequal weight across varying economic and cultural conditions (Skordoulis et al., 2020, 2024, 2025).

On a practical level, the study is limited by its methodological scope and sample design. The research draws exclusively on a survey of 322 respondents from Generation Z in Greece, which, while valuable for understanding this demographic in a specific recovering economy, limits the broader applicability of findings to other age groups, cultural contexts, or economies with different recovery trajectories. The predominance of respondents aged 18–20 further narrows the perspective to the youngest segment of Generation Z, potentially overlooking variations in attitudes and behaviors among older members of the cohort. Additionally, the reliance on quantitative measures, though effective for identifying statistical relationships, restricts the depth of understanding that could be achieved through qualitative insights such as interviews or focus groups, which might reveal nuanced motivations, contradictions, or lived experiences behind consumer choices. Practical constraints are also evident in the study's treatment of CSR education: while low participation in formal training is identified, the research does not explore in detail the structural barriers—such as accessibility, availability, or interest—that explain this gap. Finally, the focus on consumer perspectives without integrating the corporate side of CSR communication strategies risks presenting a one-dimensional view of the issue, leaving unaddressed how firms themselves perceive, design, and implement CSR in recovering economies.

5 Limitations of the work

This study, while offering significant insights into the role of CSR awareness, communication, and trust in shaping Generation Z's ethical consumerism in a recovering economy, is not without limitations. On a theoretical level, the analysis relies heavily on the Theory of Planned Behavior and Social Identity Theory, which, although effective in explaining attitudinal and identity-based mechanisms, do not fully capture the broader socio-economic and institutional conditions that affect consumer decision-making in post-crisis contexts. Structural factors such as unemployment, affordability constraints, and institutional credibility may moderate consumer behavior in ways that extend beyond the explanatory power of these frameworks. Furthermore, CSR is treated as a relatively cohesive construct, with limited differentiation between its social and environmental dimensions, even though the findings suggest that these may carry unequal significance for consumers in different contexts.

From a methodological perspective, the study is constrained by its reliance on a single-country sample drawn exclusively from Greece. While this context is particularly relevant to recovering economies, it limits the broader applicability of the results to other cultural and economic settings. The predominance of younger respondents within the sample, particularly those aged 18 to 20, narrows the scope further by emphasizing perspectives from the earliest segment of Generation Z, potentially overlooking differences among older members of the cohort. The use of self-reported survey data also introduces the possibility of social desirability bias and does not fully address the gap between stated intentions and actual consumer behavior, which may be shaped by financial limitations or market constraints (Ntanos et al., 2018a,b). In addition, the quantitative design, though valuable in establishing statistical relationships, restricts the exploration of deeper motivations, lived experiences, and contradictions that might be better captured through qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups.

Finally, the study approaches CSR predominantly from the consumer perspective and does not incorporate the corporate side of communication practices. This one-dimensional focus limits the understanding of how firms themselves design and implement CSR strategies in recovering economies, and how these align—or fail to align—with consumer expectations. Addressing these limitations in future research would allow for a more holistic and context-sensitive understanding of the dynamics that underpin CSR, trust, and ethical consumerism.

6 Potential areas of future study

Building on the findings and limitations of this work, several potential areas for future research emerge. One promising direction is the exploration of how structural and macroeconomic conditions, such as unemployment rates, inflation, and institutional trust, interact with individual attitudes and identities to shape ethical consumerism in recovering economies. Such an approach would extend the current theoretical reliance on behavioral and identity-based models by integrating broader socio-economic factors that may constrain or facilitate responsible consumption. Another avenue lies in a more nuanced examination of CSR dimensions, particularly the varying weight consumers assign to social vs. environmental initiatives. Comparative studies across different industries or cultural contexts could shed light on how these dimensions are prioritized and how firms might tailor their CSR strategies accordingly.

Future research could also benefit from broadening the demographic scope beyond Generation Z and beyond Greece. Cross-generational comparisons would reveal whether the patterns identified here are unique to younger consumers or represent broader societal shifts, while cross-national studies could test the applicability of these findings in diverse cultural and economic environments. In addition, longitudinal studies would be valuable in assessing whether CSR awareness and advocacy among Generation Z translate into consistent ethical purchasing as this cohort matures and gains greater purchasing power.

Methodologically, the integration of qualitative approaches could provide richer insights into the motivations, contradictions, and lived experiences behind consumer choices. In-depth interviews, focus groups, or ethnographic studies would complement quantitative findings and capture nuances that survey instruments may overlook. Finally, incorporating the corporate perspective into future work would provide a more balanced understanding of CSR communication. Examining how firms design, implement, and evaluate their CSR strategies in recovering economies, and how these strategies align with consumer expectations, would offer critical insights for both scholars and practitioners seeking to bridge the gap between corporate intentions and consumer perceptions.

7 Conclusion

This study set out to investigate how CSR awareness, communication, and trust influence the ethical consumerism of Generation Z in the context of a recovering economy. The findings underscore that Generation Z, despite limited formal education on CSR, demonstrates heightened sensitivity to corporate responsibility, perceiving its role in advancing social welfare and environmental protection as integral to responsible business practice. Their engagement extends beyond passive recognition to active advocacy, including the willingness to avoid irresponsible companies and to seek transparent information about CSR initiatives. In this way, Generation Z emerges as a decisive force shaping the future of ethical consumption in markets still grappling with economic recovery.

The results confirm that CSR awareness is a powerful predictor of consumer loyalty and ethical orientation, but awareness alone is insufficient to close the persistent intention–behavior gap. Communication and trust operate as critical mediators, transforming knowledge into action. Simplified and relatable CSR messaging increases comprehension, while transparent practices and partnerships with credible organizations such as NGOs strengthen authenticity, mitigating skepticism and reinforcing brand–consumer identification. These dynamics align with the explanatory power of the Theory of Planned Behavior, which emphasizes the importance of attitudes, norms, and perceived control, and with Social Identity Theory, which highlights the symbolic role of CSR in affirming consumer values and self-concept.

Importantly, the study highlights the context-specific nature of CSR in recovering economies. The prioritization of social over environmental impacts reflects the immediate challenges faced by consumers navigating conditions of economic insecurity. Ethical consumerism in such contexts is not merely a matter of lifestyle preference but part of a broader expression of resilience, fairness, and community values. This insight calls into question the universal applicability of CSR models designed in affluent markets and reinforces the need for strategies that are sensitive to local realities.

For businesses operating in recovering economies, the implications are clear. CSR must be embedded authentically in core strategy, communicated with clarity and simplicity, and validated through transparent reporting and stakeholder engagement. Generation Z will reward these efforts with loyalty and advocacy, but they will equally penalize insincerity with disengagement and distrust. By recognizing this generation as both a catalyst for change and a demanding filter of authenticity, companies can align their practices with evolving expectations and contribute to the consolidation of ethical consumerism even under challenging economic conditions.

In conclusion, the study demonstrates that CSR in recovering economies is not a peripheral exercise but a strategic necessity, driven by a generation that insists on accountability and transparency. The integration of theoretical and empirical evidence confirms that CSR awareness, communication, and trust are not isolated elements but interdependent forces that together shape consumer behavior. As such, Generation Z represents both an opportunity and a challenge for businesses: an opportunity to cultivate loyalty through responsible practices, and a challenge to consistently meet the heightened standards of authenticity and impact that this cohort demands.

The findings of this study underline that CSR should be regarded as a core strategic function rather than an ancillary activity, particularly for managers aiming to engage Generation Z in recovering economies. Awareness of CSR among this demographic is evident but remains fragmented, presenting an opportunity for businesses to transform familiarity into deeper understanding through accessible, engaging, and digital-first communication. Simplified narratives, visual storytelling, and emotionally resonant messages—especially on social media—can bridge the gap between abstract principles and tangible impact, thereby strengthening consumer confidence. At the same time, CSR communication must go beyond promotional rhetoric to highlight authenticity and purpose, clearly linking corporate initiatives to broader social and environmental issues that matter to younger consumers.

Equally important is the central role of trust in converting awareness into ethical consumerism. This requires the adoption of credibility mechanisms such as third-party certifications, NGO partnerships, and transparent reporting, which reduce skepticism and reinforce legitimacy. For firms in recovering economies, CSR strategies must also reflect local priorities by emphasizing immediate social impacts such as fairness, inclusivity, and community development while balancing global sustainability commitments. Generation Z acts simultaneously as a driver, pushing companies to adopt responsible practices, and as a filter, critically evaluating authenticity and consistency. Businesses that embed CSR authentically, communicate it effectively, and reinforce it with trust-building mechanisms will not only secure loyalty but also gain competitive advantage as leaders of ethical consumerism in challenging economic contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

A-EP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. NS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Special Account for Research Grants (SARG) of the University of West Attica.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor MS declared a past co-authorship with the author PA.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afzali, H., and Kim, S. S. (2021). Consumers' responses to corporate social responsibility: the mediating role of CSR authenticity. Sustainability 13:2224. doi: 10.3390/su13042224

Agyei, J., Sun, S., Penney, E. K., Abrokwah, E., and Ofori-Boafo, R. (2021). Linking CSR and customer engagement: the role of customer-brand identification and customer satisfaction. SAGE Open 11:21582440211040113. doi: 10.1177/21582440211040113

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ali, I., Naushad, M., and Alasmri, H. J. (2023). Effect of CSR activities on customers' purchase intention: the mediating role of trust. Innov. Mark. 19, 155–169. doi: 10.21511/im.19(2).2023.13

Armitage, C. J., and Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 40, 471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: the good, the bad and the ugly. Crit. Sociol. 34, 51–79. doi: 10.1177/0896920507084623

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., and Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 59, 46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.01.001

Bhattacharya, C. B., and Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: when, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 47, 9–24. doi: 10.2307/41166284

Brown, T. J., and Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 61, 68–84. doi: 10.1177/002224299706100106

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., and Whitwell, G. J. (2010). Why ethical consumers don't walk their talk: towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 97, 139–158. doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0501-6

Carroll, A. B. (2008). “A history of corporate social responsibility: concepts and practices”, in The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, eds. A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, and D. S. Siegel (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 19–46.

Chatzopoulou, E. (2020). Millennials' evaluation of corporate social responsibility: the wants and needs of the largest and most ethical generation. J. Consum. Behav. 20, 181–193. doi: 10.1002/cb.1882

Deep, G. (2023). The influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 9, 72–77. doi: 10.30574/msarr.2023.9.2.0162

Delmas, M. A., and Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 54, 64–87. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

Deloitte. (2021). The Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey: A call for accountability and action. Deloitte South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.deloitte.com/za/en/about/people/social-responsibility/millennialsurvey-2021.html

Djafarova, E., and Foots, S. (2022). Exploring ethical consumption of Generation Z: theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 21, 5–19. doi: 10.1108/YC-10-2021-1405

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., and Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): the role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 12, 8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00276.x

Etter, M., Ravasi, D., and Colleoni, E. (2019). Social media and the formation of organizational reputation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 44, 28–52. doi: 10.5465/amr.2014.0280

Fatma, M., Rahman, Z., and Khan, I. (2015). Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: the mediating role of trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 33, 840–856. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-11-2014-0166

Gregory-Smith, D., Smith, A., and Winklhofer, H. (2013). Emotions and dissonance in ‘ethical' consumption choices. J. Mark. Manag. 29, 1201–1223. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2013.796320

Guzmán, F., and Davis, D. F. (2017). The impact of corporate social responsibility on brand equity: consumer responses to two types of fit. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 26, 435–446. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-06-2015-0917

Heim, H. (2022). Change of mind: marketing social justice to the fashion consumer. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 11, 138–152. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.2405

Huang, M.-H., Cheng, Z.-H., and Chen, I.-C. (2017). The importance of CSR in forming customer–company identification and long-term loyalty. J. Serv. Mark. 31, 63–72. doi: 10.1108/JSM-01-2016-0046

Kagaba, A. G. (2025). Ethical consumption: the role of consumers in corporate responsibility. Eurasian Exp. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 1, 1–15.

Kaplan, A. M., and Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 53, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Kozlowski, A., Searcy, C., and Boucher, J. (2020). The role of sustainable practices in fashion industry consumer behavior. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 13, 93–105.

Lyon, T. P., and Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and end of greenwashing. Organ. Environ. 28, 223–249. doi: 10.1177/1086026615575332

Marschlich, S., and Hurtado, E. (2025). The effect of third-party certifications on corporate social responsibility communication authenticity and credibility. Corp. Commun. 30, 1–20. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-01-2024-0015

McKinsey & Company (2022). The state of consumerism: millennials and Gen Z at the forefront of ethical consumption. New York, NY: McKinsey & Company.

Min, Y. Q., and Arif, A. M. M. (2022). The influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer purchasing behaviour. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 12, 2323–2336. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i12/16022

Mohr, L. A., Webb, D. J., and Harris, K. E. (2005). Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 35, 45–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00102.x

Morsing, M., and Schultz, M. (2006). Corporate social responsibility communication: stakeholder information, response, and involvement strategies. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 15, 323–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00460.x

Nakagawa, Y., and Shaw, R. (2004). Social capital: A missing link to disaster recovery. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters. 22, 5–34. doi: 10.1177/028072700402200101

Ntanos, S., Kyriakopoulos, G., Chalikias, M., Arabatzis, G., and Skordoulis, M. (2018a). Public perceptions and willingness to pay for renewable energy: a case study from Greece. Sustainability 10:687. doi: 10.3390/su10030687

Ntanos, S., Skordoulis, M., Kyriakopoulos, G., Arabatzis, G., Chalikias, M., Galatsidas, S., et al. (2018b). Renewable energy and economic growth: evidence from European countries. Sustainability 10:2626. doi: 10.3390/su10082626

Parguel, B., Benoît-Moreau, F., and Larceneux, F. (2011). How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing': a closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 102, 15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0901-2

Pomering, A., and Dolnicar, S. (2009). Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR implementation: are consumers aware of CSR initiatives? J. Bus. Ethics 85, 285–301. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9729-9

Pomering, A., and Johnson, L. W. (2009). Advertising corporate social responsibility initiatives to communicate corporate image: Inhibiting scepticism to enhance persuasion. Corp. Commun. 14, 420–439. doi: 10.1108/13563280910998763

Ringov, D., and Zollo, M. (2007). Corporate responsibility from a socio-institutional perspective: the impact of national culture on corporate social performance. Corp. Gov. 7, 476–485. doi: 10.1108/14720700710820551

Rozenkowska, K. (2023). Theory of Planned Behavior in consumer behavior research: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 47, 2670–2700. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12970

Safeer, A. A., and Liu, H. (2023). Role of corporate social responsibility authenticity in developing perceived brand loyalty: a consumer perceptions paradigm. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 32, 330–342. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-01-2022-3807

Sen, S., and Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 38, 225–243. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.38.2.225.18838

Skordoulis, M., Kavoura, A., Stavropoulos, A. S., Zikas, A., and Kalantonis, P. (2025). Financial stability and environmental sentiment among millennials: a cross-cultural analysis of Greece and the Netherlands. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 13:64. doi: 10.3390/ijfs13020064

Šálková, D., Maierová, O., Kvasnicková Stanislavská, L., and Pilar, L. (2023). The relationship between “zero waste” and food: insights from social media trends. Foods. 12, 3280. doi: 10.3390/foods12173280

Skordoulis, M., Ntanos, S., and Arabatzis, G. (2020). Socioeconomic evaluation of green energy investments: analyzing citizens' willingness to invest in photovoltaics in Greece. Int. J. Energ. Sect. Manag. 14, 871–890. doi: 10.1108/IJESM-12-2019-0015

Skordoulis, M., Panagiotakopoulou, K., Manolis, D., Papagrigoriou, A., and Kalantonis, P. (2024). Perceptions of environmental sustainability and luxury: influences on organic food buying behavior among Millennials and Generation Z in Greece. Global NEST J. 26:06067. doi: 10.30955/gnj.006067

Skouloudis, A., Evangelinos, K., Nikolaou, I., and Leal Filho, W. (2011). An overview of corporate social responsibility in Greece: perceptions, developments and barriers to overcome. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 20, 205–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2011.01619.x

Swaen, V., and Chumpitaz, R. (2008). Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust. Rech. Appl. Mark. 23, 7–33. doi: 10.1177/205157070802300402

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict”, in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds. W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

Taofeek, A. (2024). The Role of Transparent CSR Communication in Building Long-term Brand Trust. Res. Gate Preprint. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392626119 (Accessed September 25, 2025).

Wagner, T., Lutz, R. J., and Weitz, B. A. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy: overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 73, 77–91. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.6.77

Wan Afandi, W. N. H., Jamal, J., and Mat Saad, M. Z. (2021). The role of CSR communication in strengthening corporate reputation. Int. J. Modern Trends Soc. Sci. 4, 43–53.

Wekesa, J. (2024). Impact of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) on consumer behavior. Int. J. Mark. Strateg. 6, 35–45. doi: 10.47672/ijms.2132

Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Generation Z, ethical consumerism, communication, trust

Citation: Papadopoulos A-E, Arsenos P, Sykianakis N and Stavroulakis D (2025) CSR awareness, communication, and trust: how Generation Z shapes ethical consumerism in recovering economies. Front. Sustain. 6:1699052. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2025.1699052

Received: 04 September 2025; Accepted: 25 September 2025;

Published: 28 October 2025.

Edited by:

Michalis Skordoulis, University of West Attica, GreeceReviewed by:

Miltiadis Chalikias, University of West Attica, GreeceEvangelos Chytis, University Research Centre of Ioannina (URCI), Greece

Copyright © 2025 Papadopoulos, Arsenos, Sykianakis and Stavroulakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Panagiotis Arsenos, cGFyc2Vub3NAdW5pd2EuZ3I=

Angelis-Evangelos Papadopoulos

Angelis-Evangelos Papadopoulos Panagiotis Arsenos

Panagiotis Arsenos