Abstract

Insecurity, violence, and xenophobia manifest at different geographic scales of the South African landscape threatening to compromise, reverse, derail, and contradict the envisaged democratic processes and gains in the country. Since the dawn of the new democracy in 1994, the South African landscape has witnessed surges of different scales of violence, protests, riots, looting, criminality, and vigilantism in which question marks have been raised with respect to the right to the city or urban space and the right to national resources and opportunities, i.e., access, use, distribution and spread of social, economic, environmental, and political resources and benefits. Louis Trichardt is a small rural agricultural town located in the Makhado municipality of Vhembe District in Limpopo Province, South Africa. In the study, this town is used as a securityscapes lens of analysis to explore urban conflict and violence. The relative importance index (RII) was used to measure the barriers and solutions to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in the study area. In this way, issues influencing the performance of reconfigured securityscapes in Louis Trichardt were explored by highlighting how new town neighborhood securityscape initiatives and activities are contributing to space, place, and culture change management transitions. The discussion pressure and pain points revolve around the widening societal inequalities, deepening poverty, influx of (ll)legal migrants and migrant labor, lingering xenophobia, and failure to embrace the otherness difficulties in the country. Findings highlight the options for urban (in)security, social (in)justice, and (re)design in post-colonies possibilities, limitations, and contradictions of securityscapes in (re)configured spaces of Louis Trichardt. Policy and planning proposals to improve safety and security spatial logic and innovation are explored. The critical role of community and local neighborhood watch groups in complementing state security and private registered security systems is one way of tackling this matter.

1. Introduction and background

In South Africa and with respect to decolonized African architecture and engineering feats in the built environment, ancient, indigenous, and vernacular architecture and designs highlight that historically and traditionally, the South African home has always been heavily securitized enclosures and developments, i.e., in terms of livestock (e.g., kraal and laager), symbolic of identity, territoriality, protection, pride, wealth, and investment among other considerations. This is not surprising as since civilization began, human beings have always been concerned about safety, security, and, by extension, crime. This was either in the form of defining space as a home—be it a cave or an enclosure—or a shelter structure constructed of either wood, grass, mud, or stone. This phenomenon has not completely disappeared but still exists in advanced forms of human livingscapes as reflected in modern and advanced construction and building forms and architectural styles. In a rapidly urbanizing world, there is a growth in concerns about a perceived deterioration in the sense of community due to a heightened fear of crime and violence (Agbola, 1997; Owusu et al., 2015; Frimpong, 2016; Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016). A discernible twist in the urbanization processes and identifiable trends in the Global South is the portrait of segmentation and fragmentation that is mirrored in terms of uneven allocation, distribution, and access to housing, infrastructure, transportation, and opportunities in space, time, and scale. This (sub)structure creates vulnerabilities and cracks that act as urban dividend platforms for safety, security, and crime from both positive and negative perspectives. The interplay of these realities and conditions presents challenging crime, safety, and security matters for post-apartheid South African cities and towns, which have been labeled “divided,” “fragmented,” and “broken” (Todes et al., 2002; Harrison and Huchzermeyer, 2003; Watson, 2009; Nightingale, 2012; Turok, 2013; Van Wyk and Oranje, 2014; Nel, 2016; Chakwizira et al., 2018a,b, 2021; Bank, 2019; Potts, 2020). As a sequel to these underlying spatial structure and organization inefficiencies, different sectors of the city are occupied by different social status groups that exhibit differences and diversity in livelihood styles, including the quality of urban environments (Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016).

In both developed and developing countries, such as South Africa, the safety and security narrative is a priority action area (Jürgens and Gnad, 2002; Landman and Koen, 2003; Snyders and Landman, 2018). One response to this phenomenon has been the emergence and rise of “gated communities” and “enclosed neighborhood” as a mechanism to prevent and control crime, violence, and incivility (Landman, 2000; Landman and Koen, 2003; Lemanski, 2006; Dlodlo et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016, 2019; Breetzke, 2018; Pridmore et al., 2019). These responses are partly explained by inadequate state and safety systems in place meant to protect property and citizens (Atkinson and Flint, 2004; Blandy, 2018; Branic and Kubrin, 2018; Atkinson and Ho, 2020; Ehwi, 2021; Morales et al., 2021). In these neighborhoods and precincts, the urban residents redefine urban spatial structure from territorial inclusion to controlled territories of exclusion, segregation, fragmentation, and gentrification. The steering mechanisms used to achieve the needs and aspirations of the “new enlarged homes and communities” are neighborhood enclosures, neighborhood patrol, vigilantes, private security or corporate guards, installation of closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras, mob action, and “jungle justice” (Karreth, 2019; Kurwa, 2019; Landman, 2020; Makinde, 2020; Quraishi, 2020; Smith and Charles, 2020; Thuku, 2021). Ballard (2005) argued that individuals, groups, and communities can respond through either alone or a combination of assimilation, emigration, semigration, or integration. In criticism, the author has labeled this as the privatization of apartheid and the “diabolical project of creating Europe in Africa” (Ballard, 2005; Furtado, 2022). In Durban, Kalina et al. (2019) highlighted the phenomenon of securitization as a tool for the on-going privatization of public space, which is done at the expense of excluding urban poor citizens. This worldwide phenomenon is not only peculiar to South Africa (Frühling and Cancina, 2005; Lemanski, 2006; Maguire et al., 2017; Rukus et al., 2018; Adugna and Italemahu, 2019; Karreth, 2019; Thuku, 2021). Indeed, urban space is a contested space, and if one adds the right to the city discourse, crime, safety, security, and, at times, violence are used as the instruments in (re)producing and (co)production of spatial enclaves of crime, safety, and security. A subtle but significant characteristic of urban areas is that the demographic density of cosmopolitan people and cultures creates an urban mesh environment in which the (in)visibility and mobility of human and spatial impact of crime, safety, and violence is high, complex, and difficult to extricate (Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016). Crime, safety, (in)security, and violence have been picked in literature as a “system of systems” in urban spatial (re)differentiation and (re)stigmatization in which poverty, exclusion, urban deprivation, and cultural “othering” feature strongly but acknowledgment is provided that these matters represent hard and difficult conversation areas (Leeds et al., 2008; Davis, 2012; Millie, 2012; Milliken, 2016; Salahub et al., 2018). Navigating these urban spatial (re)production, environmental design, and planning matters requires an expanded window of understanding, including exploring the changing and shifting nature of urbanscapes, streetscapes, and neighborhoodscapes if sustainable, comprehensive, and integrated solutions are to be attempted.

While many studies exist from across Africa and South Africa that investigated the social, economic, political, environmental, and physical narrative on safety, security, and crime in urban neighborhoods, no study to date has sought to explore how securityscapes have evolved and (re)shaped neighborhoods in small rural agricultural towns as represented by Louis Trichardt, Limpopo province, South Africa. Generally, the most prevalent crimes are contact crimes (assault), shoplifting, and commercial crime. In residential and industrial neighborhoods, the most reported crimes are burglary and stock theft. These crimes happen within a context in which there are several police stations and satellite stations in Makhado local municipality, namely, Police Stations (Louis Trichardt), South African Police Service (SAPS)—Saamboubrug, SAPS—Makhado, Vleifontein Police Station, SAPS—Dzanani, SAPS—Mara, SAPS—Levubu, SAPS—Watervaal, SAPS—Vuwani, SAPS—Tshitale, SAPS—Tshilwavhusiku, and SAPS—Waterpoort. Although this study acknowledges the contributions thereof of previous studies in terms of the architecture of fear, the creation of “walled cities and neighborhoods,” “enclosures within enclosures,” “perpetuation of gentrification and socio-economic spatial fragmentation,” and “the conceptual understanding and application of the framework of crime prevention through environmental design” (CPTED), the full-cycle application and context issues analysis can never be exhausted in addition to this being limited in the proposed study area (Agbola, 1997; Coetzer, 2003, 2011; Makinde, 2014, 2020; Glebbeek and Koonings, 2016; Landman, 2020). Consequently, studies that seek to further contribute to the changing and shifting urban landscape as motivated by society's response to safety, security, and crime threats and risks in terms of architectural home (re)design, information communication technologies (ICT) and standard engineering and construction safety systems, gated communities, and semi-public spaces are very important (Makinde, 2020). This study, therefore, sought to achieve the following objectives: (1) to understand the knowledge of the crime, safety, and security in Louis Trichardt, a new town as perceived and described by the people who live in the area; (2) to discuss the crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in the study area; and (3) to explore solutions of advancing safe crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes in Louis Trichardt town.

Located 113 km from the Beitbridge border post, the town offers a hedge against border town constraints but at the same time is not immune from the border post geography securityscapes issues of crime and security, cross-border trading (in)formalities, and (in)competitiveness discourses. Table 1 presents a trend analysis of crime statistics in Louis Trichardt (Makhado), during the period 2006–2020.

Table 1

| Crime type | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robbery common | 99 | 69 | 65 | 62 | 42 | 59 | 47 | 59 | 77 | 53 | 56 | 37 | 48 | 50 | 26 | 849 | 56.60 |

| Malicious damage to property | 197 | 152 | 127 | 104 | 93 | 69 | 112 | 113 | 100 | 93 | 121 | 151 | 128 | 88 | 69 | 1,717 | 114.47 |

| Total property-related crimes | 642 | 523 | 384 | 383 | 480 | 455 | 642 | 671 | 727 | 776 | 976 | 815 | 655 | 480 | 522 | 9,131 | 608.73 |

| Burglary residential - High density areas | 156 | 118 | 109 | 129 | 118 | 113 | 169 | 167 | 173 | 205 | 240 | 208 | 190 | 106 | 92 | 2,293 | 152.87 |

| Burglary residential - Low and medium density areas | 266 | 222 | 159 | 154 | 204 | 191 | 232 | 307 | 282 | 316 | 454 | 352 | 269 | 229 | 302 | 3,939 | 262.60 |

| Theft of motor vehicle and motorcycle | 18 | 21 | 26 | 17 | 26 | 30 | 27 | 20 | 29 | 27 | 35 | 36 | 34 | 24 | 21 | 391 | 26.07 |

| Theft out of or from motor vehicle | 195 | 154 | 79 | 74 | 110 | 99 | 178 | 152 | 200 | 188 | 215 | 196 | 140 | 106 | 89 | 2,175 | 145.00 |

| Illegal possession of firearms and ammunition | 9 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 30 | 22 | 11 | 21 | 27 | 24 | 200 | 13.33 |

| Drug-related crime | 68 | 51 | 47 | 63 | 44 | 66 | 106 | 136 | 136 | 229 | 277 | 376 | 356 | 252 | 20 | 2,227 | 148.47 |

| General theft | 567 | 488 | 403 | 409 | 365 | 343 | 433 | 482 | 428 | 408 | 429 | 450 | 378 | 312 | 330 | 6,225 | 415.00 |

| Commercial crime | 101 | 125 | 72 | 80 | 94 | 74 | 84 | 94 | 117 | 135 | 158 | 196 | 155 | 106 | 108 | 1,699 | 113.27 |

| Shoplifting | 276 | 243 | 209 | 276 | 219 | 192 | 263 | 209 | 169 | 120 | 163 | 144 | 133 | 112 | 147 | 2,875 | 191.67 |

| Robbery carjacking | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 71 | 4.73 |

| Robbery track hijacking | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0.40 |

| Robbery residential | 1 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 13 | 5 | 23 | 38 | 53 | 22 | 37 | 22 | 23 | 274 | 18.27 |

| Robbery business | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 15 | 26 | 17 | 38 | 34 | 24 | 29 | 20 | 239 | 15.93 |

| Kidnapping | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 34 | 2.27 |

| Total | 2,602 | 2,188 | 1,699 | 1,771 | 1,832 | 1,716 | 2,325 | 2,445 | 2,497 | 2,652 | 3,254 | 3,039 | 2,578 | 1,949 | 1,798 | 3,4345 | 2,289.67 |

| Mean | 153.06 | 128.71 | 99.94 | 104.18 | 107.77 | 100.94 | 136.77 | 143.82 | 146.88 | 156.00 | 191.41 | 178.77 | 151.65 | 114.65 | 105.77 | 2,020.30 | 134.69 |

Trend analysis of crime in Makhado (2006–2020).

Source: ISS Crime Hub, Accessed 3 March 2022. https://issafrica.org/crimehub/facts-and-figures/local-crime.

A spatial increase and spike in crime have been witnessed in Louis Trichardt (refer to Table 1). This is perceived as partly linked to an increase in “illegal” migrants, inadequate employment, entrepreneurship, and job opportunities, as well as the spatial geography, environmental design, and planning inequalities in the town, thus creating tensions and contradictions to safe streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes with implications for spatial land-use securityscapes in the town.

2. Research methods

This qualitative study is based on a case study of a new town residential suburb, Louis Trichardt, Limpopo Province, South Africa. This section covers the description of the case study; qualitative research method, questionnaire structure, and analysis procedure; data sources accessed and analyzed; and data analysis and method procedure.

2.1. Description of case study

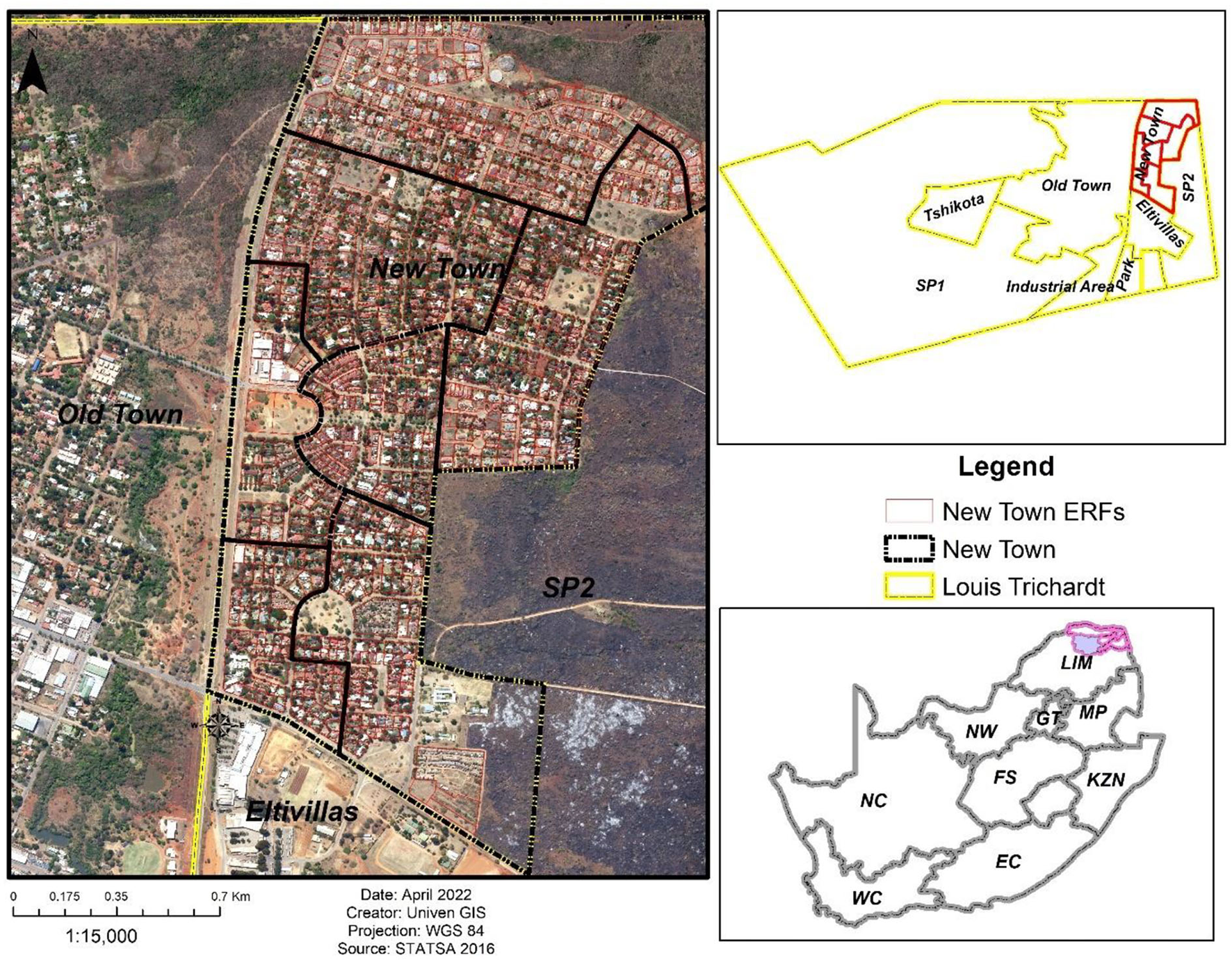

Louis Trichardt town is a small rural agricultural town that is well-known for agricultural products such as litchis, bananas, mangoes, and nuts. The town is located at the foot of the Soutpansberg mountain range, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Louis Trichardt is the center of the Makhado Local Municipality, occupying a land area of ~7,605.06 km2 (or 760,506 hectares) and is populated by ~516,031 residents. The national road (N1) cuts through the town. Louis Trichardt is located 437 km from Johannesburg and 113.3 km from the Zimbabwean border at Beitbridge. The major residential suburbs that surround Louis Trichardt are Vleifontein, Elim, Tshikota, Madombidzha, and Makhado Park. Figure 1 presents the study location map.

Figure 1

Study location map.

This research was conducted in Louis Trichardt, New Town residential areas (Figure 1), Limpopo Province, for a variety of reasons. This small rural agricultural town was selected as it recently experienced a surge in crime and security in unemployment (36.7%), poverty (45.4%), proximity to the Musina border, and a perceived increase in the number of illegal or undocumented migrants from countries located to the north of South Africa's borders. In addition, Louis Trichardt has several active neighborhood watch groups that are integrated with the SAPS. These community policing neighborhood watch groups conduct(ed) jointly and severally night patrols to minimize crime and security concerns in the Town. In terms of interviewing key informants, the snowball sampling method was utilized. This method is very helpful in approaching a population that is not readily available such as typical of the safety, security, and safety value chain and systems (Perez et al., 2013; Alvi, 2016). The participants were asked to rate the extent to which each of the crime, safety, and security neighborhood barriers affected the neighborhoodscapes as well as to make suggestions on possible solutions in advancing safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town using a five-point Likert scale. The reliability of multiple Likert scale questions was measured using Cronbach's alpha. The Cronbach's alpha (α) value obtained using SPSS version 27 was 0.81, indicating a high level of internal consistency for the scale.

2.2. Qualitative research method, questionnaire structure, and analysis procedure

A qualitative research methodology approach was used in seeking to explore the study's research aims and questions. Qualitative research methodology offers the advantages that it is in the research paradigm that argues that human–environmental behavior and interactions cannot be understood and studied outside the context of an individual's daily life and lived experiences (Low, 2003, 2008a,b, 2009, 2017; Salcedo, 2003).

Qualitative interviews were carried out with key informants who were leaders and had lived and experienced the urban environmental conditions of the study area for at least a minimum of 3 years. The purposive selection of the key informants enabled the collection of detailed data and information on the urban crime, safety, and security conditions of the study area (Babbie, 2001, 2020; Wagenaar and Babbie, 2001). In addition, qualitative approaches are viewed as an ethically sensitive way of conducting research (Minichiello et al., 2008). Overall, this method enabled “access to, and an understanding of, activities and events which [could not] be observed directly by the researcher” (Minichiello et al., 2000, p. 70; Quintal, 2006; Minichiello et al., 2008).

In addition to the two five-point Likert scale questions, an open-ended question schedule was developed to examine the issues central to the research questions (Minichiello et al., 2000, p. 65). The questions were related to (1) the safety, security, and crime experiences of living in the residential community; (2) initiatives and possible solutions to addressing safety, security, and crime experiences in the study area; and (3) any ideas or suggestions for improving the environmental conditions in the study area.

These open-ended questions helped to complement, confirm, and triangulate the data and information sources with respect to the two five-point Likert scale central questions. Given the sensitivity and nature of the study, the key informants were approached through contacts making use of the snowball sampling technique. Random approaches on matters linked to safety, security, and crime could have aroused suspicion, thereby causing distress, discomfort, and/or lack of cooperation.

A thematic content analysis of the research findings was conducted, with each transcript being coded according to the identified themes (Low, 2003). Thematic coding made it possible to explore the following issues: (1) respondents lived experiences and perception of safety, security, and crime in the study area; (2) exploring a chronology of measures, strategies, and actions adopted by the residents in response to perceptions of safety, security, and crime in their residential neighborhood; and (3) discussing ideas and potential solutions to fighting the perceived forms of safety, security, and crime in the neighborhood.

2.3. Data sources accessed and analyzed

Four data sets were accessed to explore security statistics in the study area. First, the Makhado Integrated Development Plan (IDP) from 2015–2022 documents were accessed and analyzed. These documents were reviewed with the aim to understand and explore trends with respect to the theme of crime, safety, and security. The interest was to establish whether the theme remained a key theme and a significant priority intervention area. Second, the Crime and Security SAPS databases were reviewed. This database was accessed from 2015 to 2022 with the purpose to understand the trends and major forms of crime, safety, and security matters in South Africa, Limpopo province, and Louis Trichardt in particular. Third, the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) crime statistics databases were reviewed, focusing on extracting crime statistics for the study area. Finally, the Crime and Justice Hub (https://issafrica.org/crimehub) was also accessed and reviewed, with a focus on crime statistics for the study area. Through this triangulation of data, validity and reliability were ensured. It is also suffice to point out that the databases were complementary and had the same information in the final analysis. What differed is how the data and information are presented and analyzed. The content and thematic analysis of these databases enabled for the better interpretation and analysis of study results and analysis in context.

2.4. Data analysis and method procedure

Data obtained were analyzed using frequency, percentage, mean, relative importance index (RII), and ranking. The RII was used to rank barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town as well as potential steering mechanisms and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town, using the new town as the case study. The RII computed in this article is adopted from a previous computation in Mbamali and Okotie (2012), which is as follows:

where

Here x = weights given by each participant on a range of 1–5 on the Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree); f = frequency of respondents' choice of each point on the scale x; and k = maximum point on the Likert scale (in this case, k = 5). The RII computed for barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town as well as potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods settlements and built environment areas were ranked in their order of size.

Ranking of the items under consideration was based on their RII values. The item with the highest RII value is ranked first, next, and so on. Interpretation of the RII values is made as follows: if RII <0.60, the item is assessed to have a low rating; if 0.60 ≤ RII < 0.80, the item is assessed to have a high rating; and if RII ≥ 0.80, the item is assessed to have a very high rating.

3. Theoretical framework

This section covers three critical but complementary aspects of the theory and philosophy of securityscapes. This section is dedicated to critically exploring the concept and notion of securityscapes and engaging in a theoretical reflection on the multiple dimensions and perspectives on crime, safety, and security in residential neighborhoods. In addition, the concept of home/house, fear, and security is explored within the purview of environmental, urban design, and spatial planning.

3.1. Concept and notion of securityscapes

The concept of a securityscape is linked to the understanding of human (in)securities. It was coined and developed from the original concept of “scapes,” originally proposed by Appadurai in 1996 (Appadurai, 1996, 2010; Omurov, 2017). Securityscapes are defined as “imagined individual perceptions of safety motivated by existential contingencies or otherwise theorized as givens of existence (i.e., death, freedom, existential isolation, and meaningfulness)” (Omurov, 2017). Table 2 presents an adapted exploration of Appadurai's (1996) five scapes within the scope of the built environment.

Table 2

| Scapes typologies | Description | Crime, safety, and security discourses |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnoscapes | • Migration mobilities (intra-inter), movement and flows of people, goods, and commodities across national borders • Exportation and importation of cultures of difference and otherness • Adoption, adaptation, and simulation of host countries, neighborhoods, and town cultures |

• Environmental and architectural (re)design and planning • Cultural mixing • Cultural integration • Cultural (re)branding |

| Mediascapes | • Modern communication technologies that quickly allow the sharing of localized information globally, as well as how media changes people's imaginations and perceptions • The utilization of various forms of mass media as interaction, messaging, knowledge, and information sharing and communication tools and mechanism in an area • The assemblage of various images, sounds, and programmes presented by the mass media or through billboards |

• Neighborhood watch groups • Community policing • Street surveillance • CCTV smart security technologies • Armed response security and alarm systems • Site layout design and architecture • Building layout (re)design • Infrastructure and barrier hardening |

| Technoscapes | • The rapid spread, adoption, and use of emerging technologies in the globalized “village” world • The uptake of mechanical technology, e.g., machinery, gadgets, and cars • Informational technology, which in its broadest scope involves more virtual technologies involving telecommunications and software |

• Closed-circuit television (CCTV) and “cat eyes” • Smart planning and home security technologies • Drone technology • Industrial Revolutions 4 and 5 • Mobile communication technologies, e.g., WhatsApp, Messenger, Telegram • 3D printing • Virtual reality and augmented reality • Geographic information systems (GIS) and remote sensing (RS) applications |

| Financescapes | • Exchange of currencies, stocks, and related commodities • Cross-border movement and flow of loans, equities, direct and indirect investments, currencies, and remittances that transcend the power of the nation-state |

• Banks • Money transfer companies • Money exchange and application transfer • Money laundering and smuggling |

| Ideoscapes | • Cross fertilization of ideologies of different countries and cultures influence each other • Shifting and changing political and ideological beliefs landscapes of people • Political discourses of the Enlightenment, e.g., sovereignty, freedom, rights, welfare, representation, and democracy |

• Political ideologies and constitutions • Environmental planning and design concepts, models, and paradigms • Spatial planning (re)branding • Urban area renewal and revitalisation • Xenophobia • Afrophobia, Afroscepticism, or Anti-African • White supremacy |

Unraveling Appadurai's (1996) five scapes: reduction and application to crime, safety, and security in built environment dimensions.

According to Appadurai (1996), definitions of scapes can be viewed as the conceptual lens with applications to the built environment (refer to Table 1). This can be understood from a perspective that scapes are imaginary transboundary perceptions consisting of “ethnic, cultural, religious, national, political, and other identities” not confined to geographical scales but are subject to globalization drivers such as labor mobility, technology innovation and diffusion, media communication, curation and management, and ideology with regard to individual domestication of the above-mentioned issues (Omurov, 2017). Following Appadurai's concept of “scapes,” von Boemcken has attempted a refinement of the definition of securityscapes (Von Boemcken et al., 2018; Von Boemcken, 2019; Von Boemcken and Bagdasarova, 2020). In these studies, the authors highlighted that people have developed both mitigation and adaptation strategies and everyday life behavior linked to perceived and imagined threats and potential solutions. This is achieved via mind mapping and picturing secure and safe streets, neighborhoods, and environments (both psycho-social and geographical-spatial) for themselves, families, neighborhoods, and communities. From this exercise, one then adjusts attitudes, behavior, movement, and trip pattern (whether conscious or subconscious) to fit and navigate in safe and sustainable living patterns within imagined secure world realms (Omurov, 2017; Boboyorov, 2018; Ismailbekova, 2020; Oestmann and Korschinek, 2020; Paasche and Sidaway, 2021).

In this article, the concept and notion of securityscapes are extended to apply to the concept of streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes. In this regard, streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes are conceived and viewed as multiple and differentiated dynamic, changing, and shifting scale dimensioned; safety, security, and crime imagined; and related imaginations and practices that individuals, communities, and organizations adopt in seeking to show and make their environments safe from crime and violence. This incorporates the concept of “riskscapes,” which is defined by Müller-Mahn et al. (2018) as an assemblage of local practices for managing risks quite, irrespective of the “discourses of danger” articulated within the “ideoscape” of the town, neighborhood, or nation-state (Lemanski, 2006; Müller-Mahn et al., 2018).

3.2. Theoretical synthesis on crime, safety, and security in residential neighborhoods

Table 3 presents a schematic tabular representation of safety, security, and crime theoretical groundings.

Table 3

| Concept and notion | Purpose | Implications for policy, planning, and design |

|---|---|---|

| Site layout and housing architectural design and style | • Security measures that are designed to deny access to unauthorized personnel (including attackers or even accidental intruders) from physically accessing a building, facility, resource, or stored information • Guidelines and guidance on how to design structures to resist potentially hostile acts |

• Zoning laws, by-laws, and regulations • Building lines • Setbacks • Elevations • Orientation |

| Physical safety | • Locked doors and windows • Strong walls, door locks, and safes • Multiple layers or skins of barriers • Armed security guards • Guardhouse placement • Restricting physical access by unauthorized people (commonly interpreted as intruders) to controlled facilities • Limiting access within a facility and/or to specific assets, and environmental controls to reduce physical incidents such as fires and floods • Using key cards/access badges • Intruder alarms and CCTV systems |

• Adaptive designs • Flexible designs • Resilient designs • Disaster risk profiling, management, and planning • Safety costs to property owners/residents • Safety costs to state/government • Full-cycle safety, security, and crime analysis • Integrated safety, security, and crime analysis • Safety, risk, and crime management framework • Safety designers, architects, and analysts to balance safety controls against risks at scale |

| Social capital | • The price and value generated through the human associations or systems that allow a society to function efficiently • Origins in classical and old philosophical concepts of the upright society and the role of citizens in encouraging social wellbeing • Societies with low social capital show more adverse results comprising higher crime rates • Social capital as the networks, norms and trust that permit a society to function effectively |

• Community policing • Reassuring policing • Integrated safety, security, and crime framework |

| Residents' perception of safety | • Tendency to assume that rises in, or high levels of, crime and disorder will automatically result in worsening neighborhoods' safety • Controls considered adequate in the past tend to be insecure today and in future as advances in the knowledge and capabilities of attackers evolve • People who live in gated communities control access through key cards, electronic codes, video surveillance equipment, and security guards, measures that deter crime and keep strangers including unwelcome visitor out, making the community quiet and safe but not fully immune from crime and safety imperfections |

• Gated and walled neighborhoods and enclosures • Spatial gentrification • Spatial fragmentation and splintering • Spatial safety, security, and crime infrastructure hardening and targeting |

| Safety | • Safety is an ambiguous and ambivalence concept that assumes different meaning in time, space, and context • In well-resourced communities, safety incorporates security in terms of ability to protect against known risks, as well as the application of technology and manpower against criminal intent • Managing a growing sense of unsafe neighborhood and environments is among the most pressing concerns for public policy • Building a safer society strengthens and enhances resilient communities' development • Interpretation, negotiation, and definition of a sense of safety and security is a reflexive process in which individuals and communities integrate and link both objective and subjective dimensions of safety and security |

• Safety, security, and crime orientated and sensitive development plans, improvement plans and schemes, and SDFs (Spatial development frameworks) • Building safe environments, streets, public spaces, and neighborhoods • Resilient communities |

| Gated communities | • A gated community is a residential development with controlled access by means of a security gate located at the front entrance • Sometimes the entire neighborhood is enclosed within a perimeter of gates • Physical measures, in combination with hired guards, replace the older social control mechanisms, which are based on community social cohesion • Gated communities refer to a physical area that is fenced or walled off from its surroundings, either prohibiting or controlling access to these areas using gates or booms • Enclosed neighborhoods refer to existing neighborhoods that have controlled access through gates or booms across existing roads. Many are fenced or walled off as well, with a limited number of controlled entrances/exits and security guards at these points in some cases |

• Urban acupuncture • Spatial fragmentation, segregation, exclusion, and inclusivity • Inclusive cities • Just cities • Resilient cities |

| Territorial geographies theory | • If spatial boundaries and order are threatened, socio-spatial control responses are the outcome • Forms of socio-spatial control take place in terms of what Foucault identifies as discourses and practices of governmentality and territoriality • Governmentality, or “the conduct of conduct,', marks people and places by regulating through technologies of discipline who should be in public space and what is defined as public space • Emerging practices define and redefine what and who should be included within the public and what and who should not • Territoriality, a variation of spatial policing and targeting, is another method of socio-spatial control used to delineate public space and limit access to public space for those who are not considered citizens | • Functional spatial planning • Spatial targeting • Spatial integration • Spatial fragmentation • Spatial splintering • Foucauldian planning theory and philosophy • Spatial and territorial governance • Communicative and collaborative planning |

| Community policing theory | • Policing of space occurs at various scales through various means, ranging from the policing by law-enforcement agencies to community watch groups • Neighborhood watch groups—given their own systems of vigilance (in cooperation with local law enforcement), are able to police spaces through alternative means of policing (for example, members of a group can physically patrol certain crime ‘hot spots' for much longer than can a police officer or patrol team) • Neighborhood organizations that can take the form of block watch groups, neighborhood associations, homeowners' associations, and crime prevention councils are often involved in forms of community policing • In these neighborhood associations, there exists a community of fear based on the threat of an “invasion by outsiders” • Residents believe their neighborhoods are under siege by outsiders, and they seek to “take back” their community • Community policing is often not representative of the larger community as residents with greater social capital participate to a greater extent than those with fewer social resources and instances in which this leads to policies which “target members of the community who do not [or even cannot] participate” have been recorded and witnessed in practice | • Participatory and integrated policing • Local level crime, safety, and security planning • Street level crime, safety, and security planning • Block level crime, safety, and security planning • Community Ubuntu ethics of care, responsibility, humanity, and sympathy |

| Broken windows theory | • The basic premise of broken windows theory is that if a window gets broken and is not repaired, it is assumed, both by the community and by the outsider, that the building is not cared about by its inhabitants or the neighborhood • Neighborhood morale begins to decline and criminals move in • The chain effect is more broken windows and an escalation of nuisance crimes, such as graffiti, vandalism, and trespassing • Broken windows theory is applied by police and community policing organizations through arresting and reporting of petty crimes such as graffiti, vandalism, and trespassing • The focus is on dissipating crime before it spirals out of police and community control • Broken windows theory is a way of controlling social meaning and, by doing that, changing human behavior • Broken windows theory is not just about windows, but the control of disorderly people. Broken windows can be made of glass, but they can also be people | • Governmentality and territorial planning • Spatial policing and targeting • Abandoned houses, structures, and buildings • Vacant land, stands, and (re)development |

| Geographies of exclusion | • Johnston (2001, p. 540) defines a neighborhood as an area “within which there is an identifiable subculture to which the majority of its residents conform.” • A process of including neighbors and excluding those not constructed as such and reinforcing conforming behavior • Exclusion may take the form of social sanctions, in which strangers or those seen as outsiders or undesirables are ignored or harassed • Harassment can be from residents, community watch groups, or the police or mob justice | • Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) |

| Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) | • CPTED is the design and use of the built environment in a way which leads to a reduction in both the fear and incidence of crime and an “improvement of the quality of life.”' • The basics of CPTED: natural surveillance, access control, definition of territory, image and maintenance, and community activation • Making environments easy to see into/out of so that users of that space can see what is happening in or on all parts of their property • Making the environment unfriendly for trespassers and potential criminals so that they feel unsafe because they are too visible • Lighting is an important part of natural surveillance, but the precise type of lighting is key • Glaring or direct lights can be “dangerous and hide criminal activities.” • Access control is about “determining who you want on the property and limiting access to those you do not want.” • It is about designing and placing walkways, building entrances, fences, landscaping, and lighting in such a way as to discourage crime • Territorial definition is about promoting the “proper use” of zones, i.e., four zones (public, semi-public, semiprivate, and private) • Use of signage, e.g., “No Trespassing/No Loitering” or “No Parking” signs can deter crime • Image and maintenance—If one keeps properties looking good on all sides, it “sends a powerful message that the people here care about this place and will not tolerate bad behavior in this area.” | • Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) • Safe walking routes • Walking buses |

Schematic literature review of representation of safety, security, and crime theoretical groundings.

Sources: Authors own construction and adapted from Kelling and Wilson (1982), Rose (1993), Sadd and Grinc (1994), Putnam (2000), Johnston et al. (2001), MacAllister et al. (2001), Flyvbjerg et al. (2002), Minnery and Lim (2005), Elden (2007), England (2008), Malette (2009), Morgan (2013), Makinde (2014, 2020), Wilson and Kelling (2015), Muiga and Rukwaro (2016), Olajide and Lizam (2016), Musyoka et al. (2017), Jiang et al. (2018), Mashhadi Moghadam and Rafieian (2019), Sarhan (2020), and Security (2021).

The intersection of crime, safety, and security highlights the multidimensional, multidisciplinarity nature of the crime, safety, and security adaptive complex “system of systems” (refer to Table 3). At the same time, interventions and initiatives to address the challenge are innumerable, but these measures and efforts can never be perfect or complete. Although safety, security, and crime can be reduced, it is debatable whether all risks can be completely wiped off in an area. Safety and its antithesis of unsafe are, therefore, conceived and viewed as important and intriguing concepts (Wilson and Kelling, 1982, 1989; Lawanson et al., 2013; Farinmade et al., 2018; Iliyasu et al., 2022). Makinde (2020) highlighted that although increased safety precautions may alleviate the resident's fears, upgrades and alterations to the physical environment can introduce visual cues that may intensify concerns about neighborhood crime, safety, and security in other people as well as give high-risk signals to attract criminals to such highly “protected and defended” properties. It is also interesting to note that the need for a more reassuring police presence in the community is highlighted as part of the solution (Millie and Herrington, 2005; Millie, 2010, 2012, 2014; Millie and Wells, 2019). Millie's “reassurance policing” is an approach to encourage positive encounters between the police and the public, thereby fostering greater police presence, visibility, and accessibility (Povey, 2001; Millie, 2012; Oh et al., 2019; Park et al., 2021; Aston et al., 2022).

3.3. Linking security, urban design, and spatial planning

Linking security, urban design, and spatial planning is one critical cornerstone to building sustainable and friendly urban environments. In seeking to explore how security, urban design, and spatial planning are interrelated and interconnected, there is a need to revisit the notions and concepts of security, urban design, and spatial planning. Such reconceptualization seeks to locate the home/house as the first unit of security, urban design, and spatial planning, while the community is an invisible open enclosure of the extended aggregated values and standards of the home/house security, urban design, and spatial planning regimes. In this analysis, three typologies of security, urban design, and spatial planning emerge (1) home/house security, urban design, and spatial planning (i.e., micro site unit location, design, and architectural offerings); (2) neighborhood security, urban design, and spatial planning (i.e., meso block and street landscape, layout and block design, and sense of place characteristics); and (3) the residential suburb community security, urban design, and spatial planning (i.e., the macro township or suburb or suburban security, design concept and spatial structuring form, and structure and arrangement). These three levels of the concept of home, house, street blocks, and neighborhood cascading to the township or city-wide spatial structure represent the hierarchy of security, urban design, and spatial planning complexities that operate as a “system of systems” in either promoting safe urban environments or not.

In exploring the relationship further, a home/house is defined by the Oxford dictionary as “the place where a person (or family) lives; one's dwelling place, e.g., a specific house, apartment, etc.” The concept of the home can be expanded to include the extended home/house (the neighborhood, the suburb, the town, and community, as well as other environments that we identify as home, e.g., spatial area or region or province of origin) and is, therefore, viewed as symbol-laden. A home encompasses the following attributes: resting place, place of peace and security, love and belonging, recovery and social ties and bonding, inspiration, and identity, among other aspects (Appleyard, 1979a,b). The home, therefore, embodies the familiar place in which residents are comfortable and feel at ease. In addition, the home nests a place identity through the medium of a location that one perceives as “theirs, ours” and acts as a symbol of self-identity, consciousness, ownership, possession, and inheritance (Marcus, 1976, 1997, 2006; Low, 2008a,b; Argandoña, 2018; Smith, 2018; Akesson and Basso, 2022). The term “fear (of crime, safety, and security plus)” was coined by Lemanski (2006) in recognition that fear of crime, safety, and security is related to much wider processes than just crime and violence. Various studies corroborate that “fear (of crime, safety, and security plus)” does not match the actual risk of victimization (Valentine, 1989, 2016, 2022; Valetine, 1992; Beck and Willis, 1995; Beck and Chistyakova, 2002; Beck and Robertson, 2003; Eugene et al., 2003; Buus, 2009; Eagle, 2015; Beck, 2019; Hughes, 2022). Oftentimes, the fear of crime, safety, and security plus masks broader and deeper fears (Judd, 1994, 2004; Samuels and Judd, 2002; Judd et al., 2005; Jalili et al., 2021). In South Africa, these deeper and broader fears include the presence of other races/ethnicities/nationalities in proximity, fear of “otherness,” fear of changes (at a national, provincial, and local scale), and fear of uncertain future for oneself and one's family (Schuermans, 2016; Blandy, 2018; Masuku, 2018; Yates and Ceccato, 2020). In this regard, Lemanski (2006) highlighted that the label “fear of crime, safety, and security plus” can be viewed as the explanation for deeper fears of change and racial difference.

Meanwhile, a community is defined as “an interacting population of various kinds of individuals in a common location” or “a group of people with a common characteristic or interest living together within a larger society” (Dunn, 1996; Clough, 1999; Jordan, 2018). Invariably, the concept of the community can have interpretations in terms of an extended and expanded concept and notion of the house/home and neighborhood that creates a sense of belonging, cohesion, bonding, togetherness, and unity of common purpose within the bounds of diversity and differences in a township, suburb, or city-wide environment.

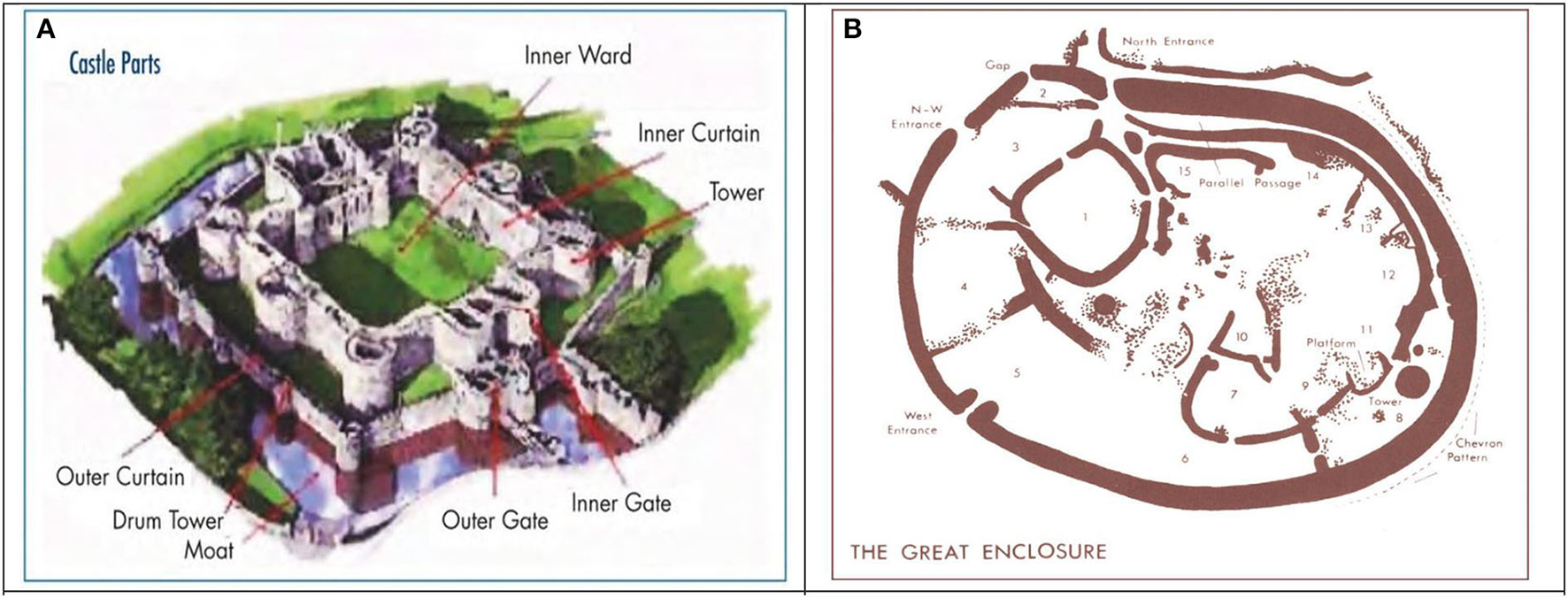

Considering the proceeding debates, the history of urban planning and spatial design has numerous studies that clearly incorporate fear (of crime, safety, and security plus). For example, the classical design of castles and walled cities (found in both pre-colonial and post-colonies of developed and developing countries), in terms of the courtyard design and the Cul-De-Sac and Radburn principle, has long demonstrated the influence of location, site design, urban design, spatial planning, landscape architecture, and public planning in creating safe environments, neighborhoods, and homes (refer to Figure 2). The medieval cities and castles, Bentham's (1830, 1843a,b) classic “panoptican” prison design, Baron Haussman's Parisian boulevardization, and Jacobs's (1961) reliance on natural surveillance (“eyes on the street”) to reduce fears of crime, safety, and security related focused on research studies that illuminate the interaction, integration, and complementarity between private, citizen, and state-driven fear spatial design, planning, and management strategies (Lemanski, 2006; Li et al., 2011; Frimpong, 2016; Philo et al., 2017; Courtney, 2018).

Figure 2

Crime, safety, and security plus site, urban design, and spatial planning examples from the history of town planning. (A) Fema's site and urban design for security historic European settlement spatial structure. (B) Great Zimbabwe site and urban design African settlement spatial structure. Source: Fema (2007) and Chirikure and Pikirayi (2008).

Urban planning and design principles, norms, and standards to counter crime, safety, and fear plus issues consider the following elements summarized in the CPTED (refer to Figure 1): built and neighborhood environments that are easy to see into/out; lighting to make criminals and intruders impossible to hide; designing and placing walkways; building entrances and fences; landscaping; and lighting in such a way so as to discourage crime are important hallmarks in home, site, street, neighborhood, and town/cityscapes design and spatial logic systems (Cozens et al., 2005; England, 2008; Owusu et al., 2015; Iqbal and Ceccato, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Marzbali et al., 2016; Sohn, 2016; Thani et al., 2016; Mihinjac and Saville, 2019). Thus, connecting, linking, and integrating security, urban design, and spatial planning in a harmonious way are central to creating safe and friendly home/houses precincts, urban streetscapes, blockscapes, neighborhoods, suburbs, and cities that are a pleasure to work, live, and recreate in. These building blocks are linked to each other in an “onion” security, urban design, and spatial planning framework in which each unit of analysis builds and adds a layer and skin of (in)security, urban design, and spatial form that, in aggregate, constitute the “total” security, urban design, and spatial planning safe and friendly environment. This security “system of systems” “onion-layering” security, urban design, and spatial planning system create a value chain that if “broken” or disturbed, has reverberating impacts on the need for system security, urban design, and spatial planning framework adjustment and amendments in attempts to recover and imprint security, urban design, and spatial planning norms and standards of safe and secure environments subscribed in each area. Considering the discussion, the importance of full-cycle analysis and activation of these linkages in application to the crime, urban design, and spatial planning context of any urban or rural setting cannot, therefore, be over-emphasized.

4. Discussion of results and findings

This section discusses study results and findings from the key informants' interviews (KII) as well as an analysis of crime statistics extracted from the relevant databanks. In addition, the study recommendations, study limitations, and areas for future research are also explored.

4.1. Key informants respondents: Descriptive statistics

Forty-four (44) key informants were purposively sampled by the researcher for their knowledge of the crime, safety, and security in Louis Trichardt and the new town residential suburb. Table 4 presents the demographic breakdown and representativeness of the study respondents.

Table 4

| Knowledge and expertise domain representation | Selected expertise profile | Number of purposively selected respondents or participants |

Age (years)

(mean) |

Gender | Number of years living in Louis Trichardt or Louis Trichardt new town (mean) | Percentage of total research participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||||||

| District development Planning foruma | • Spatial planners • LED Officers • University of Venda Lecturers |

9 | 41.6 | 5 | 4 | 18.5 | 20.45 |

| IDP representative forumb | • Activist/lobby group representing aged people's forum • Moral regeneration and youth council • Local Service Delivery and Municipal Resident Engagement Forum |

10 | 44.8 | 6 | 4 | 24.2 | 22.72 |

| IDP clustersc | • Representative from COGHSTA (planning and development) • COGTA (planning and development) • Provincial Treasury Representative (IDP) |

6 | 33.5 | 2 | 4 | 4.2 | 13.60 |

| IDP steering committeed | • Senior Manager—Municipal Manager • Senior Manager—Development and Planning • Senior Manager—Director Community Services |

5 | 35.3 | 3 | 2 | 7.2 | 11.36 |

| Community police forume | • Crime intelligence • Investigating crime • Stakeholder relations |

6 | 45.2 | 4 | 2 | 12.9 | 13.60 |

| Development and real estate industry | • Realty 1 • Harcourt limitless • Anhetico properties |

8 | 50.1 | 5 | 3 | 20.6 | 18.18 |

| 44 | 25 (56%) | 19 (44%) | 100 | ||||

Key informant respondents.

This Forum is Chaired by Development & Planning General Manager and composed of the following: the district and its four local municipalities, Development and Planning Managers, Technical Managers, Local Economic Development (LED) Managers, Integrated Development Plan (IDP) Managers, Spatial Planners, Surveyors, Transport Planning Managers, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Managers from municipalities, University of Venda, Madzivhandila Agricultural College, Parastatals, i.e., state-owned enterprise, Representatives from sector departments at planning sections, and representatives from Traditional Leaders.

This is Chaired by the Executive Mayor and composed by the following stakeholder‘s formations—inter alia: Vhembe District Municipality, Local Municipalities i.e., Makhado, Musina, Thulamela, and Collins Chabane LM, Governmental Departments (District, Provincial, and National Sphere representatives), Traditional leaders, Organized business, Women's organization, Men's organization, Youth movements, People with disability, Advocacy Agents of unorganized groups, Parastatals, Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), Community-Based Organization (CBO), Other service providers, i.e., consultants and constructors, Other Social Sectors and Strata, University of Venda, Madzivhandila Agricultural College, Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges, Aged People‘s Forum, Moral Regeneration and Youth Council.

Chaired by departmental General Managers and composed of experts, officials, and professionals from all spheres of government: Governance and Administration, Economic, Social, Infrastructure, and Justice Clusters.

Chaired by the Municipal Manager and composed as follows: General Managers, Senior Managers, Managers, Projects Managers, Technicians (post level 4 and 5), Professionals (post level 4 and 5), Specialists/ Experts (post level 4 and 5), and Project Management Unit (PMU).

South African Planning Services Act (SAPS) Act 68 of 1995 legislated that Community Police Forums (CPF) as the only recognized consultative forum designed to permit communities to make their policing concerns known to the police. Community Policing Forum is a platform where community members, organizations (CBO, NGO, Business, Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs), youth organizations, women organizations, School Governing Body (SGB), other relevant stakeholders (provincial government, local government, traditional authority, and parastatals), and the police meet to discuss local crime prevention initiatives.

The selected key informants had first-hand information working with the district development planning forum, spatial planning and human settlement and environmental design, IDP Representative Forum, IDP Clusters, IDP Steering Committee, Community Policing Forum, Crime Intelligence, and Investigating Crime (refer to Table 4). They thus provided critical insights, reflexive thinking, and perceptions with respect to the integration and intersection of crime, safety, and security with environmental design, architecture, street planning layout, spatial planning, community policing, statutory constitutional peace, and order as well as general environmental wellbeing of streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes. These insights assisted in deepening and expanding the interpretation of the discourse under investigation. It is suffice to point out that the IDPs in the study area have prioritized basic service delivery provision with an emphasis on water and energy and implied attention to crime, safety, and security. The identified gap partly explains the lack and absence of architectural Liaison Officers in the police departments and local authorities for structured engagement and resolution of crime, safety, and security matters in the study area. Although preventing and combating crime is not easy, it is, however, not an insurmountable task. With greater cooperation between the state and non-state actors, the various types and categories of crime can be tackled head-on. However, attention must not be lost that those solutions to (re)solve these issues are complicated and rely on a level of state resources/competence that seems difficult to materialize if we use prior knowledge and experience on how similar problems have played out in practice. This perhaps calls for the need for both the state and non-state sectors to re-invent and innovate differently in seeking to transform the crime, safety, and security landscapes in blockscapes, streetscapes, and neighborhoodscapes in any setting.

4.2. Crime statistics trends in the study area

Data sets from SAPS statistics and the ISS were accessed and filtered by sub-district and precinct to reflect the data relevant to Makhado Local Municipality. Property crime and property-related crime instances are very high in the study area (refer to Table 1). While this is the case, attention should not be lost on the other crimes as criminals usually commit the crimes in a chain and a multi-pronged comprehensive and all-inclusive approach to tackling crime and safety matters are important. An approach that isolates and targets one crime and safety hotspot and thematic zone area will result in displaced crime and safety spill-over effects. Crime has been on an upward trend from 2006 to 2020 (refer to Table 1). At the same time, due to the COVID-19 lockdown in 2021 together with stronger local neighborhood activity during this period, the crime levels were low. This upward and concerning trend in crime activity was lamented by one of the key activist informants as follows:

“When I moved to stay in Louis Trichardt town in the early 2000s, this was owing to a job opportunity I was very keen to pursue. The little town was sweet, clean, and peaceful. I am afraid I cannot say the same about the town as of now. I remember I could hang clothes until very late in the night and would sometimes forget to pick up the clothes on the line. However, my family and I would wake up and still find the clothes on the line—intact. Now mention this to fellow residents and it is like you are talking folk stories or jokes. We now must be vigilant. We now have an active neighborhood watch group that also has an interest in the development of the town. They are night patrol teams that work hand in hand with the police. These patrol the streets at night for seven days. Different teams do this every day, and they have nicknames and identity codes that I will not share with you. They are doing a very good job and assisting with identifying bushes that should be cleared, overgrown grass that should be cut, and identifying abandoned or vacant stands to establish owners and ensure that these areas are not nests for unscrupulous elements. They have a functional system which we are grateful for. I know they are working on hiring a security company for the neighborhood and have engaged well with the municipality to implement a city-wide CCTV programme to assist in crime detection and prevention.” Extract of a verbatim interview with a key informant respondent local development activist in the study area.

As reflected in Table 1, with regard to the burglary at residential premises in the police precinct, Makhado is a crime area of concern. Burglary has been an increasing trend, creating fear, security, and crime plus challenges for the residents. Usually, the spike tends to be in the early year (i.e., January to March) and midyear around (i.e., August and September) as well as October and November. These are linked to the holiday and festive seasons as well as the beginning of the year in which some key informants attributed anecdotal evidence to returning “illegal immigrants” from the north of South Africa. Although this perception was shared, there were no hard statistics to support and confirm this viewpoint. Regarding the current levels of crime in Makhado Local Municipality, in 2022, residential burglary and general theft are the highest forms of crime common in the study area. This places in perspective on residents' crime, safety, and security fear plus concerns, thus prompting residents to respond in various ways such as changing traveling behavior and patterns and upgrading home security systems, such as buying dogs and cats for added security. Property- and contact-related crimes are high in the study area. This is because property attacks usually involve contact with thieves.

4.3. Barriers to secure streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes

The barriers identified from the literature and confirmed by key informant stakeholders of the new town Louis Trichardt neighborhoods' settlements were ranked according to their RII (refer to Table 5).

Table 5

| Barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment | Weighting ( x )/response frequency ( f ) | Σf | RII | RII rating interpretation | Rank | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Spatial geographic socio-economic differentials and wealth inequalities | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 31 | 44 | 4.45 | 0.89 | Very high | 1st |

| Lack of visible and quick reaction police crime unit | 3 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 21 | 44 | 3.90 | 0.78 | High | 2nd |

| High rates of unemployment (especially among the youths and active working groups) | 3 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 19 | 44 | 3.65 | 0.73 | High | 3rd |

| Inadequate stand and home architectural design and safety design and friendly set-up | 7 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 44 | 3.11 | 0.62 | High | 4th |

| Presence of illegal immigrants | 10 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 44 | 2.63 | 0.52 | Low | 5th |

| Inadequate environmental and urban planning design neighborhoods and streets | 18 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 44 | 2.04 | 0.40 | Low | 6th |

Barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town.

1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree, = mean, f = frequency.

Interpretation of the RII values is as follows: if RII < 0.60, the item is considered to have low rating; if 0.60 ≤ RII < 0.80, the item is considered to have high rating; if RII ≥ 0.80, the item is considered to have very high rating.

The ranking that crime, safety, and security plus matters are indeed social and economic issues corroborates previous findings of similar and related studies that apply the “broken windows” theory to the phenomenon (refer to Table 5) (Frimpong, 2016; Wrigley-Asante, 2016; Beck, 2019; Oh et al., 2019). The major crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes barriers to safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas are as follows: spatial geographical socio-economic differentials and wealth inequalities (RII = 0.89), lack of visible and quick reaction of police crime unit (RII = 0.78), high rates of unemployment (especially among the youths and active working groups) (RII = 0.73), and inadequate stand and home architectural design and safety design and friendly set-up (RII = 0.62). However, the presence of illegal immigrants (RII = 0.52) and inadequate environmental and urban planning design neighborhoods and streets (RII = 0.40) are low ranking factors that explain the architecture and dimensions of crime, safety, and security streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes in the study area. The need to address the spatial and economic geography inequalities, inefficiencies, and settlement distortions have long been identified as a stubborn legacy that requires resolution in South Africa (Nightingale, 2012; Turok, 2013; Chakwizira et al., 2018a). The 2030 National Development Plan (NDP) in South Africa highlights the importance of creating a reassuring and world-class police and security system in South Africa. Chapter 12 on building safer communities objective is: “In 2030 people living in South Africa feel safe and have no fear of crime. They feel safe at home, at school, and work, and they enjoy an active community life free of fear. Women can walk freely in the street and the children can play safely outside. The police service is a well-resourced professional institution staffed by highly skilled officers who value their work, serve the community, safeguard lives and property without discrimination, protect the peaceful against violence, and respect the rights of all to equality and justice.” The requirement for better policing presence, availability, accessibility, and velocity in addressing crime, safety, and security is a requirement and expectation that transcends nation-states throughout the world (Millie and Herrington, 2005; Millie, 2010, 2014; Ratcliffe et al., 2015). The matter of the inadequate site, home and neighborhood environmental, spatial planning, and design deficiencies is a matter at the core of urban design and planning (Cozens et al., 2005; Owusu et al., 2015; Iqbal and Ceccato, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Marzbali et al., 2016; Sohn, 2016; Thani et al., 2016; Mihinjac and Saville, 2019; Saraiva et al., 2021). The following transcript extract from a resident who owns a Security and Alarms Company provides useful insights on potential security features that one can consider in building home defense and seeking to make houses and homes safer:

“Look, residents and everyone must understand that criminals are out there on the prowl and looking for the slightest opportunity to break into your home, company premises, car etc., and take valuables and property. What I would advise and generally advise clients, relatives, families, and friends is that have clear entrances and transparent walls or elevation that allow your home/house or premise to be visible from the main street. Have lighting and if possible, security sensor lights that are triggered by movements. Also having beams and a security system linked to a security company provides a sense of added safety and security. Increasing the layers that intruders must peel through, from the wall, razor wire or electric fencing, or spikes, strong locks and doors, extra door screens, and good burglary to ensure you delay any forced attempts and give you reaction time is important. Having a dog or dogs can also deter criminals and even cats can assist in case of intruders. If you have an alarm system always test that it is working. It also helps to have contact numbers of your neighbors, the police hotline as well as being on the social/community neighborhood watch group platforms. In the event of an attack, you can always alert these systems of networks so that they can be activated for support. In general, also, remember to be vigilant as usually criminals study and comb your area for some time studying all the victim's movement patterns, activities as well as profiling the victim household in terms of composition by age, sex, and other information etc.” Extract of a verbatim interview with a key informant respondent who owns a security and alarm company operating in the study area.

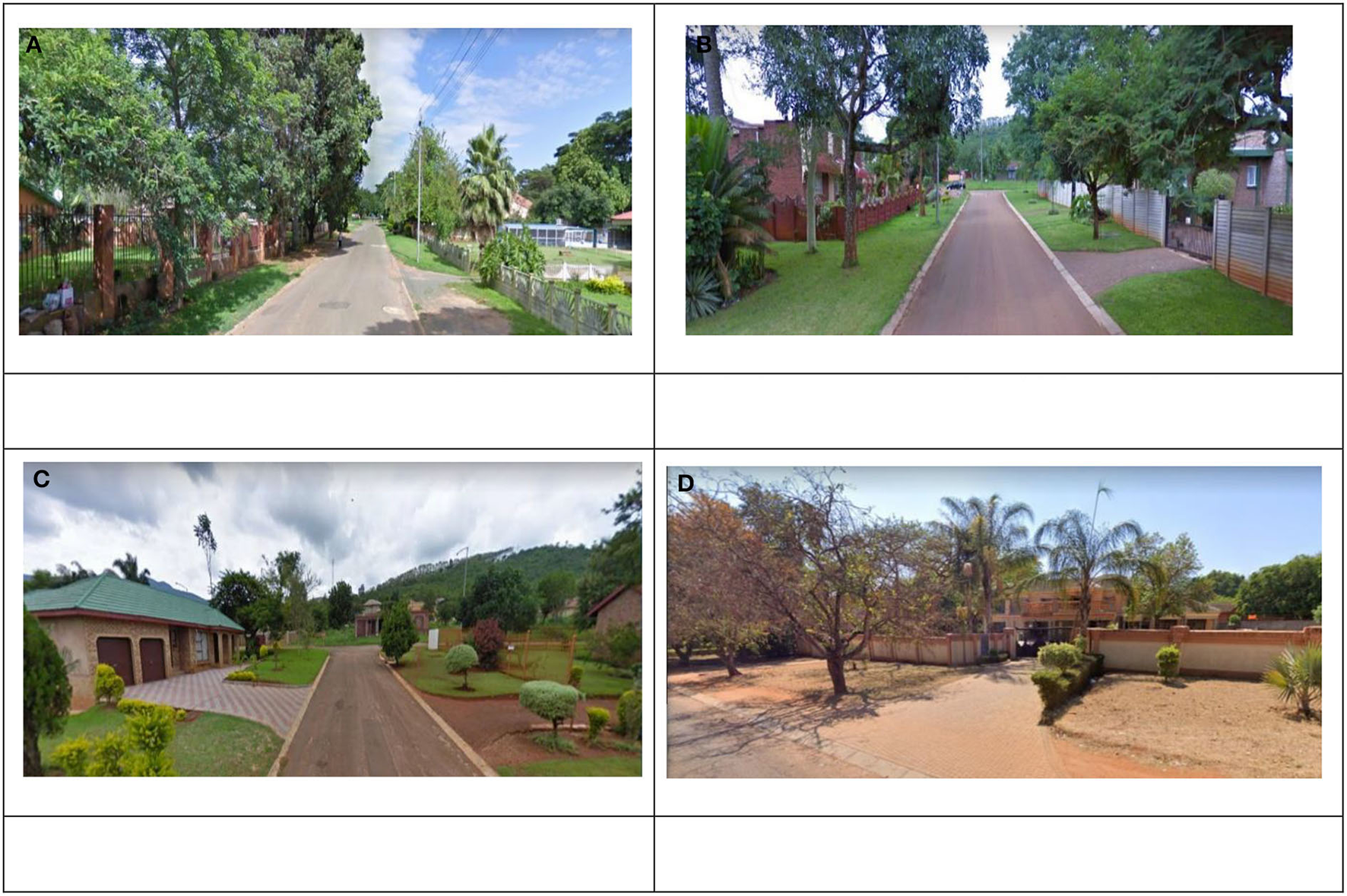

Figure 3 presents streetscapes pictures of different streets in the new town, Louis Trichardt. On the other hand, Figure 4 presents buildingscapes skyline and architectural changes over time in the study area.

Figure 3

Pictures of streetscapes in the new town, Louis Trichardt. (A) Mimosa street: low and open fencing/walling. (B) Rietbok street: no fencing, high and closed durawalls/fencing. (C) Leeu street: no fencing—landscaping, gardening, and elevation. (D) Bauhinia street: high strong walls, electric fence, and gate.

Figure 4

Buildingscapes skyline and architectural changes over time in Louis Trichardt. (A) Modern house with high wall, electric fence, and transparent electric gate. (B) Old style (1970–1980s) house with tree and steel open fencing and gardening. (C) Gated community housing estate with open communal courtyard. (D) Modern double storey building—open and closed landscaping and elevation security designs at play.

Different households and residents have erected different types of security systems (Figure 3). These range from low transparent walls and open fencing for increased inside and outside surveillance, to high closed off walls in which both inside and outside surveillance are blocked and extremely curtailed usually accompanied by electric fences, CCTV camera, and armed response security teams' subscription and protection. The main private armed response security companies operating in Louis Trichardt and the study area are Big 5 Security Company, DRS Security Company, and TMS Security Company among others. Similarly, at the same time, buildingscapes skylines have evolved over time with a mixture of open and closed building systems being constructed and developed in the study area (Figure 4). The issues of securityscapes, neighborhoodscapes, streetscapes, blockscapes, and mapping riskscapes are matters that have also been investigated and identified as critical in seeking to understand barriers in advancing safe communities and neighborhoods. Indeed, barriers to crime, safety, and security are complex, multiple, interconnected, and interdependent, suggesting that solutions to overcoming these barriers need collaborative engagement and partnership of all role players and actors involved in safety, security, crime prevention, combating, and reduction value chain.

4.4. Advancing secure streetscapes and neighborhoodscapes in Louis Trichardt town

Potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance crime safe and security streetscapes, blockscapes, and neighborhoodscapes environments were identified from the literature and confirmed by key informant stakeholders of the new town Louis Trichardt neighborhoods' settlements and, thus, were ranked according to their RII (refer to Table 6).

Table 6

| Potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas | Weighting ( x )/response frequency ( f ) | Σf | RII | RII rating interpretation | Rank | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Stimulating jobs creation and entrepreneurship opportunities | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 29 | 44 | 4.36 | 0.87 | Very high | 1st |

| Integrated community and police enforcement and compliance management systems and procedures | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 32 | 44 | 4.27 | 0.85 | Very high | 2nd |

| Developing a spatially balanced and integrated urban mixed economy and settlements | 2 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 26 | 44 | 4.15 | 0.83 | Very high | 3rd |

| Retrofitting and implementing environmental and urban planning design neighborhoods and streets “crime, safety, and security” hotspots improvement plans and strategies | 7 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 18 | 44 | 3.59 | 0.71 | High | 4th |

| Capacity building, training and awareness on safety, crime, and security innovation and advancements for both community and police department | 10 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 16 | 44 | 3.34 | 0.66 | High | 5th |

| Addressing border immigration imperfections and irregularities | 16 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 44 | 2.77 | 0.55 | Low | 6th |

Potential steering mechanism and inflection points to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town.

1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree, = mean, f = frequency.

Interpretation of the RII values is as follows: if RII < 0.60, the item is considered to have low rating; if 0.60 ≤ RII < 0.80, the item is considered to have high rating; if RII ≥ 0.80, the item is considered to have very high rating.

Entrepreneurship, economic growth, innovation, and diversification strategy (RII = 0.87) are at the core of measures and actions meant to advance safe neighborhoods' settlements and built environment areas in Louis Trichardt town specifically, but South Africa generally and developing countries in general (refer to Table 6). An economic approach to solving socio-economic problems manifesting in crime, safety, and security plus challenges is not a new approach but a well-established approach (Judd, 2004; Scheider et al., 2012; Soltes et al., 2020). The challenge was to build strong local integrated and balanced economic systems and structures that can foster an environment that encourages job creation and employment opportunities (RII = 0.83) at rates higher than the demand for jobs and employment. The following transcript extract from a key informant who is an urban design and planning expert provides useful insights on how the spatial and mobility turn pathway can be used as a pathway in fostering the existence of safer environments and communities:

“The legacy of the spatial divide and fragmentation in South African cities must be addressed with a greater sense of urgency and velocity than we have witnessed before. The longer we nurse this wound, the longer it will continue to pain and hurt us in so many ways. The situation in which the country remains one of the most unequal societies in the World, with the gini-coefficient hovering around 63 does not do good to various well-meaning efforts by government to tackle poverty, unemployment, and inequality. Given this context, areas of high income are seen as spatial enclaves of wealth and opportunity by criminals who predominantly come from the low-income areas and poverty enclaves, or persons sometimes being labeled as illegal migrants, although crime knows no border, nationality, or race. Urban designers, architects, planners, and various actors involved in the planning, renewal, upgrading and establishment of human settlements should always plan and design the blocks, streets, and neighborhoods with a view for implanting in-built design policing and social surveillance systems in place. Retrofitting designs after plan approval and implementation always places the bigger burden for financial capital investment for upgrades on the residents and to some extent the municipality. In short, many gains in friendly, safer designs and communities can be achieved with participatory urban design planning and the inclusion of multiple disciplines and stakeholders interested in neighborhood, town, and urban planning and development.” Extract of a verbatim interview with a key informant respondent who is an urban design and planning expert in the study area.

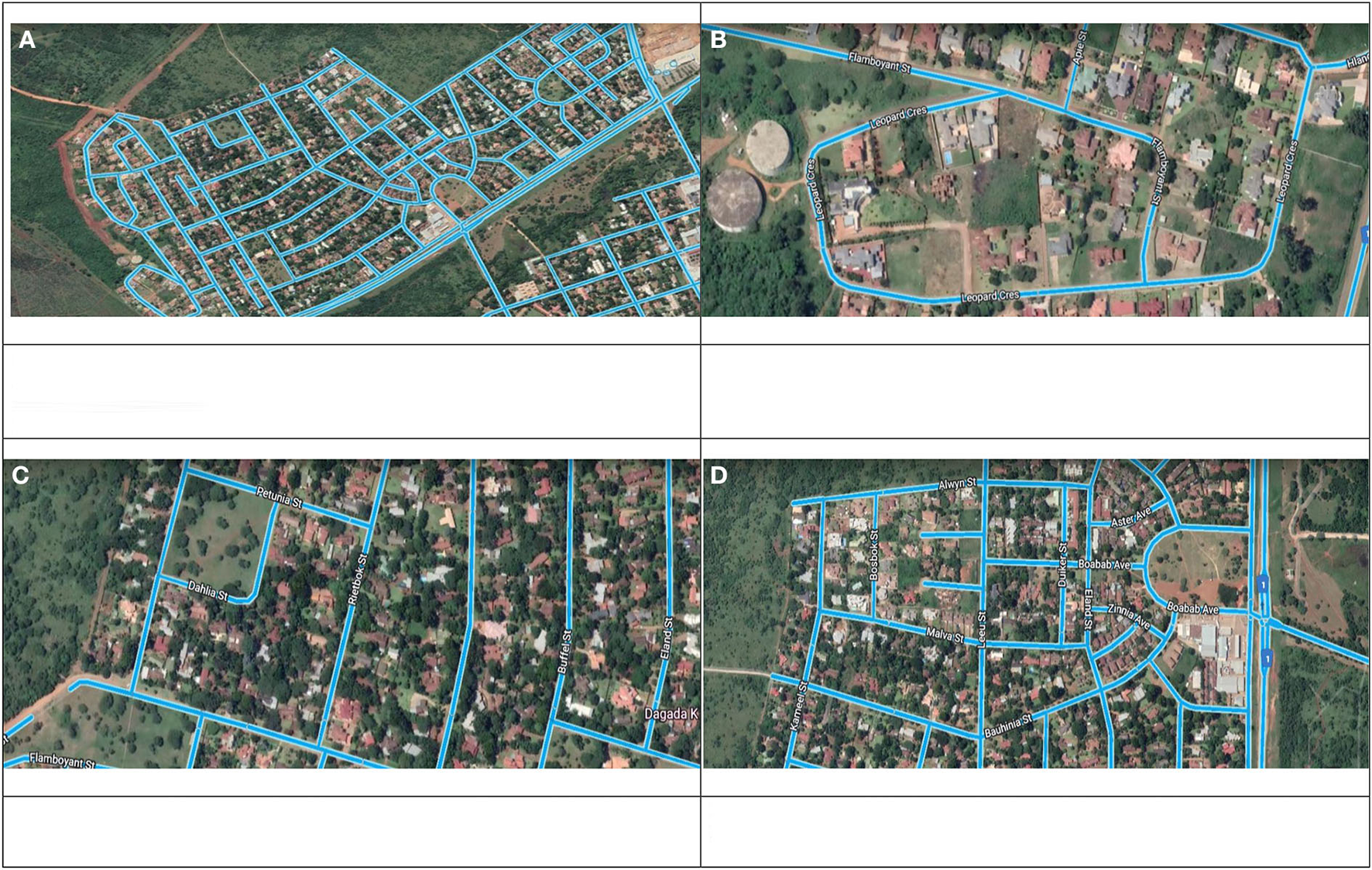

Figure 5 presents 2D mapping illustrations of streetscapes and blockscapes layout and arrangement in the new town residential area, Louis Trichardt.

Figure 5

2D streetscapes and blockscapes layout and arrangement in new town residential area, Louis Trichardt. (A) Streetscapes and blockscapes aerial 2D view of new town—the proximity of the neighborhood to N1 as well as the block layout and streetscape that encourages permeability, easy accessibility and exit, and ease legibility providing opportunities for quick escape by criminals, especially those that are mobile. (B) Streetscapes and blockscapes aerial 2D view of new town showing vacant/open stands that pose security threat in area. (C) 2D streetscape and layout showing big open space as well as stands bordering farms—which edge farmlands and forests are used by criminals as get-away and hiding nests. (D) 2D streetscape and blockscape showing cul-de-sac and short avenues that enhance neighborhood surveillance and community or street/block policing.

The 2D mapping of streetscapes and blockscapes in new town residential area shows that different forms of planning and design principles were used in the layout and arrangement of the neighborhood (Figure 5). These spatial planning and urban design models are predicated on the need to encourage accessibility, legibility, and permeability, bringing variation in street function, length, size, and distribution with diverse crime and security implications. In trying to maximize place-making connectivity and linkages of neighborhoods, the challenge lies in seeking to balance these principles with the need for safety, security, peace, orderliness, serenity, and the protection of the neighborhood quality of area.