Abstract

Introduction:

How to make work life increasingly meaningful and ensuring that business actions aim at improving quality of life is a trending topic. Yet, it has not often been studied within architectural firms, that play a crucial role in achieving sustainable development goals, especially those related to equity, equality, and the creation of pleasant work environments. This study aims to identify whether there are gender differences in the perception and levels of workplace happiness of individuals working within architectural companies in Valencia (Spain).

Methods:

A mixed methodology based on qualitative and quantitative data has been applied with a sample of 201 workers from 60 practices.

Results:

Participants perceive themselves as flourishing and quite happy at work. Yet, there are gender differences in the factors that motivate workplace happiness. While women prioritize the work environment, their colleagues and teams, men point out to career development. Thus, recognition, appreciation, feeling valued and goals and achievements are among the main drivers of men’s workplace happiness. In addition, women tend to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, or sadness more frequently than men. Given these results, architectural companies face a considerable challenge.

Discussion:

The research examines the relationship between workplace happiness and social sustainability in architectural firms, highlighting the importance of human capital for competitiveness. To promote sustainability and well-being at work, it is crucial to understand how organizational decisions impact employee well-being and to know the differences in perceptions of workplace happiness between men and women. This analysis may be of interest to the architectural firms object of this research.

1 Introduction

That happiness has become a popular topic these days is undeniable, especially due to its well-known political, economic, and social consequences unveiled over time. It not only attracts the attention of academics and researchers, but some authors even assert that Western society is “enchanted” with happiness (Alam, 2022). There is an overexposure to this ideal from childhood, through hygiene products, pet items, food, drinks, books, magazines, blogs, and Hollywood movies, which speaks volumes about the ubiquity of happiness in our lives (Cabanas and Illouz, 2023; Alam, 2022).

The impact of happiness is such that governments recognize its importance and include it in many nations’ policies along with well-being (Cabanas and Illouz, 2023; Alam, 2022; Musikanski et al., 2021; Butler and Kern, 2016). However, this has not only happened with happiness but also with sustainability. Initially associated with environmental issues, sustainability has reached such considerable influence that the UN has proposed a series of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that countries should achieve as part of the 2030 Agenda (UN, 2020).

This study falls within SDG #11, which aims to make cities and communities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable environments (UN, 2020). This means promoting social inclusion, equal opportunities, and diversity; aspects that have significant impact on subjective well-being, that is, the happiness of people living in cities.

Although at first glance, the connection between well-being, happiness, and sustainability may not seem relevant, there is growing awareness that they are intertwined (Alam, 2022; Posada and Aguilar, 2012). Studies investigating this relationship are therefore important, particularly if focused on the workplace.

Thus, considering that:

-

Happiness at work is closely linked to human development (Wijaya et al., 2021) and to individuals’ quality of life (López-Ruiz et al., 2021).

-

Companies play an important role in promoting equity, diversity, and equality, which contribute to creating more inclusive cities.

-

Increasing happiness within organizations can create a “butterfly effect”1, that is, happier people can help build more prosperous businesses, and these, in turn, will contribute to making cities more inclusive, safe, and resilient.

This research aims to explore happiness in the architectural companies in the city of Valencia.

1.1 Background

Sustainable development promotes the existence of a balance between economic growth, environmental protection and social well-being (Warnecke, 2015; Posada and Aguilar, 2012; UN Environment, 2020; United Nations Development Programme, 2012; Brundtland, 1987). Thus, when organizations strive for equity-oriented and inclusive business practices, productivity, economic prosperity and respect for the environment, they align with this approach. In other words, if sustainability encompasses the environmental, economic, and social spheres, it means that all organizational actions should aim to improve people’s quality of life.

In the literature, gender has been studied as a determinant for achieving social equity (Nasser and Fakhroo, 2021; Raj et al., 2019; Guzmán, 1998), which is one of the pillars of sustainability (Warnecke, 2015; Bosch et al., 2005). In this sense, as part of their sustainable actions, firms are responsible for ensuring that all individuals have the same opportunities regardless of gender. However, some studies show that inequalities in this regard persist, especially in the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry (Carrasco and Perez Lopez, 2024; Möller et al., 2022).

For example, working in this traditional male-dominated sector (Reimers and April, 2022; Ridgeway et al., 2022; Sánchez De Madariaga and Novella, 2022; Savitri, 2022; Çivici and Yemişçioğlu, 2021; ACE, 2020) is associated with higher levels of dissatisfaction in the workplace for women (Oluwatayo, 2015; Cantonnet et al., 2011; Sang et al., 2007). Additionally, barriers such as the wage gap, the glass ceiling, lack of visibility, and low inclusion of women are aspects that continue to emerge (ACE, 2023; Ahuja and Weatherall, 2023; Möller et al., 2022; Reimers and April, 2022; Ridgeway et al., 2022; Savitri, 2022; Barrera et al., 2021; Çivici and Yemişçioğlu, 2021; Alba, 2018; Navarro-Astor et al., 2017; Oluwatayo, 2015; Whitman, 2005).

Furthermore, there are still gender differences in time use, with women being more burdened with domestic and family care responsibilities (Möller et al., 2022; Çivici and Yemişçioğlu, 2021; Sang et al., 2007), and difficulties for balancing career and family life (Troiani, 2024; ACE, 2023; Reimers and April, 2022; Navarro-Astor et al., 2017). In addition to higher levels of stress, perceptions of different treatment due to gender, and lower happiness indices among women (Van Heerden et al., 2024; Navarro-Astor et al., 2017; Sang et al., 2007), are some of the many inequalities that have been identified.

In contrast, the flourishing life is an acclaimed theory by Seligman, focusing on human flourishing through the pursuit of well-being and authentic happiness (Seligman, 2011). In this context, the PERMA model arises, an acronym for the factors Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. Hence, to flourish means to perceive that life is mostly filled with positive emotions, to show engagement in what one does, to build warm relationships with those around you, and to take challenges aimed at personal fulfillment (Kern, 2022; Butler and Kern, 2016; Seligman, 2011).

The PERMA-Profiler, proposed by Butler and Kern (2016), emerges as a tool aimed at providing a measurable character to Seligman’s PERMA model. Additionally, it was adapted by Margaret Kern to the workplace environment, adjusting the questions to better reflect work experiences and challenges (Kern, 2022). The instrument includes the following five dimensions that encompass both the hedonic and eudaimonic nature of happiness2:

-

Positive emotions: it focuses on aspects related to the satisfaction and joy experienced at work.

-

Engagement: it examines the ability to immerse oneself while enjoying work.

-

Positive relationships: it refers to the bonds of camaraderie woven in the organization as a result of working with others.

-

Meaning: it explores the level of importance people place on the work they do.

-

Feeling of accomplishment: it relates to the work done to achieve set goals and continue advancing to the next level.

In addition, the instrument includes another 4 factors: physical health, negative emotions, loneliness, and happiness (Kern, 2022; Butler and Kern, 2016).

-

Physical health: it evaluates physical conditions, vitality, and the ability to perform daily work activities without difficulty.

-

Negative emotions: it explores the presence and frequency of emotions such as sadness, anxiety, or anger in the workplace.

-

Loneliness: it investigates how often a person feels lonely at work.

-

Happiness: as an overall measure of subjective well-being, that is, life satisfaction.

Regarding happiness at work, various studies have recognized that human capital is the fundamental endogenous factor influencing performance, for achieving businesses’ growth and market positioning (Mendoza-Ocasal et al., 2021; Alnachef and Alhajjar, 2017). Following this idea, all human beings want and need happiness, that is, the subtle natural balance between work and personal, family, social, and emotional life (Firmansyah and Wahdiniwaty, 2023). For this reason, organizations have a significant mission in the post-pandemic era, which is to make happier and more productive workplaces (Ruiz-Rodríguez et al., 2023).

In order to achieve this, the first step is to dismantle the myth that happiness is a purely metaphysical and cumbersome topic, with no real results in organizations (Bilginoğlu, 2020). In McKee’s words: “Work is work, after all. It’s supposed to be grueling and a means to an end” (McKee, 2017: p. 48). Hence, companies are not there to make anyone happy, not a place that motivates happiness, nor a source of fulfillment. Secondly, despite being a challenge, there are theoretical models that seek to measure happiness in the workplace. In fact, well known and accredited measurement tools exist that help corroborate hypotheses and broaden understanding of this construct, as well as provide subjective insights and identify problems (Butler and Kern, 2016). Thirdly, it is important to recognize that the link between happiness and sustainability aims at human well-being and that both are dynamic in nature. Hence, sustainability implies an ongoing process of development, which is to say, it is not a fixed point (Papadopoulou and Lapithis, 2015), just like happiness, which is a continuous search rather than a static goal to be achieved (Camps, 2019). Therefore, the combination of these two elements offers significant possibilities for analyzing individual well-being (O'Brien, 2008) and how it affects organizations and society in general.

As outlined in this text: i) it is acknowledged that happiness, sustainability, and organizational performance do not go separate ways (Halis and Halis, 2022; Sameer et al., 2021), ii) it is considered that studies on happiness possess great potential that has not yet been fully exploited to promote sustainability (O'Brien, 2008), iii) it is recognized that, although defining sustainability in a social context is complex (Sameer et al., 2021), it is unavoidable, given that individual flourishing is interconnected with that of others, both in the present and in the future (O'Brien, 2013), and iv) the focus is on architectural firms.

1.2 The architectural firm

Architecture is part of the construction sector, which, incidentally, has historically played a crucial role in Spain’s economic growth, even during periods of economic hardship, such as the pandemic that notably affected businesses in the sector due to the shortage of materials and construction equipment, delays and increased expenses, reduction and changes in both demand and financing, among other factors (Tahir, 2023).

Architectural firms are entrepreneurial businesses that sell professional services. Their work focuses on coordinating and merging various commercial functions through specific projects, developed over weeks, months, or even years, which involve deep research and a substantial amount of problem-solving. The goal is to meet clients’ expectations and needs, maintain the desired quality standards, and respect the established budget (Srećković, 2018; Oyedele, 2013).

Generally, architectural firms are small businesses, so they have a lower average turnover, they rely considerably on their reputation, and use established relationships with clients to generate new business opportunities (Raisbeck, 2020; Srećković, 2018). In Spain, the architectural sector is highly fragmented, with small firms predominating, many of which have few or no permanent employees. This makes it difficult to develop professional careers with clear criteria for entry, stabilization, advancement, promotion, and access to leadership roles (Sánchez De Madariaga and Novella, 2022).

On the other hand, regarding sustainability, understood from the perspective of inclusion and equity as previously mentioned, the social evolution that has taken place in the country in recent decades has resulted in greater women’s presence in the field of architecture, with a noticeable increase in their numbers in universities (Sánchez De Madariaga and Novella, 2022; Ocerin-Ibáñez and Rodríguez-Oyarbide, 2022). However, this has not translated into equality in the professional field, where significant gender disparities persist in the number of practicing women, promotion, pay equality, invisibility in firms, and uncertain and unsafe working conditions, among many other aspects (Sánchez De Madariaga and Novella, 2022; Navarro-Astor and Caven, 2018).

In light of the above, first, it is acknowledged that women’s contributions to the sector are increasingly valued, gaining recognition and expanding job opportunities (Savitri, 2022). Second, although job happiness has been widely addressed and recognized by researchers in many fields, there are very few studies concerning architectural firms. Third, job happiness is understood as an important aspect of human resources (HR) practices, and as mentioned, studies have found a positive relationship between human capital happiness, organizational performance (Pant and Agarwal, 2020; Ramírez et al., 2019; Fisher, 2010), and sustainability (Alam, 2022; Halis and Halis, 2022; Sameer et al., 2021). Hence, results of this analysis may be of interest and benefit to the architectural firms object of this research and contribute to the construction of sustainable cities.

Finally, as they often go unnoticed in academic research because of the difficulty in accessing information and there being a scarcity of studies (Raisbeck, 2020; Oluwatayo et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2016), this research is focused on architectural firms. This situation, along with their significant contribution to the economy (ACE, 2020), makes them a particularly interesting subject of study.

1.3 Study objectives and hypotheses

The objectives of this research are the following:

-

To explore definitions of happiness and workplace happiness within architectural firms and to estimate gender differences.

-

To investigate women’s and men’s perceptions regarding happiness in architectural workplaces.

-

To analyze the dimensions and factors of the Workplace PERMA-Profiler, determine their values, compare them by gender, and establish whether gender influences the perception of workplace happiness among the sample population.

Furthermore, the hypotheses proposed are:

H1: Working men and women in Valencia’s architectural companies perceive that they are flourishing at work.

H2: There are significant differences between men and women in Workplace PERMA-Profiler dimensions and factors.

2 Materials and methods

Although there is no consensus on the definition of happiness at work, there is agreement on its hedonic, eudaimonic, social, and multidimensional nature (Peiro et al., 2021; Sender et al., 2021; Posada and Aguilar, 2012; Fisher, 2010). Therefore, this research adopted a mixed methodology to rigorously analyze the complexity of the phenomenon (Sender et al., 2021; Fehrenbacher and Patel, 2020), gain a deeper understanding (Andrews Kenney, 2024), and respond to the call for methodological diversity in this type of research (Clark and Plano Clark, 2022). Consequently, qualitative and quantitative data were obtained.

2.1 Quantitative methods

In order to corroborate the hypotheses, a questionnaire was created based on the Workplace PERMA Profiler measurement tool, in its Spanish version by Julián Lorenzo Farrapeira and Arlen Solodkin (Kern, 2014).

Butler and Kern’s PERMA-profiler is not the only instrument that exists to measure the dimensions of Seligman’s PERMA (Muñiz-Velázquez et al., 2022). However, this research adopted this instrument because it offers a hedonic and eudaimonic view of happiness (Yang et al., 2024; Giangrasso, 2021). Additionally, because this instrument, which consists of 23 items (15 items assess the five PERMA dimensions, along with 8 additional items: 3 related to health, 3 to negative emotions, 1 to loneliness, and 1 to happiness), was subjected to a rigorous validation process in its English version (Chaves et al., 2023; Butler and Kern, 2016). Furthermore, it has been adapted and validated in different countries, among others: Malaysia, Australia, Ecuador, Colombia, Indonesia, India, Japan, Turkey, Germany, Greece, Chile, Venezuela, Italy, United States, India, Greece, Australia, Brazil, Portugal, and Spain (Chaves et al., 2023). Moreover, this tool has a version suitable for the workplace, known as Workplace PERMA-profiler (Kern, 2022; Kern, 2014), which has been adapted, validated and used by some researchers (Rice, 2024; Yang et al., 2024; Choudhari, 2022; Muñiz-Velázquez et al., 2022; Donaldson and Donaldson, 2020; Choi et al., 2019; Watanabe et al., 2018). Thus, considering that the dimensions of Seligman’s PERMA influence work performance (Mendoza-Ocasal et al., 2021; Seligman, 2011), the Workplace PERMA-profiler is deemed appropriate for their measurement.

2.1.1 Procedure

The list of companies used in this study comes from the SABI database (Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System), which provides legal, economic, and financial information on more than 2 million Spanish companies. This tool is widely used in research as it covers a significant and representative percentage of the companies operating in the country (Guillen and Baqué, 2024; Julia-Igual et al., 2020).

The following steps were taken for sample selection: First of all potential participant companies were chosen according to the National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE, 2009), with code 7111 (Technical Architectural Services). These companies had to be registered at the regional architectural professional association (Colegio Territorial de Arquitectos de Valencia), employ qualified professionals, or engage in their activities directly or indirectly. In addition, only companies registered in the commercial registry of the city of Valencia were included, while those without contact information (address, website, phone number), with inconsistencies in their activity status according to various sources, or outdated contact details (bounced emails or incorrect phone numbers) were excluded. As a result, a database consisting of 143 companies was obtained (the company is the unit of data collection). Applying the formula used by Oluwatayo et al. (2018) [n = N/(1 + α^2 N)], where n = sample size; N = population; α = significance level, which is 0.05 for this study, a sample size of 105 companies was obtained.

Then, a pilot study was conducted with seven people from two different firms, each with five employees. Its purpose was to evaluate the easiness with which respondents could complete the survey questionnaire and the time it would take them to do so. The clarity of the language used, the adequacy and logic of the questions and the design were analyzed, as well as the ease of access and navigation of the questionnaire. Additionally, participants were asked to suggest other aspects that could be added. All participants commented on the clarity and ease of the questionnaire and suggested the inclusion of some additional sociodemographic aspects, which were incorporated into its final version.

The questionnaire was designed in an online Google form for its ease of administration, guarantee of anonymity, low individual application costs, and practicality for conducting analysis (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2014). Subsequently, an introductory letter was sent by email to the 143 companies in our database. This letter described the research objectives, informed about approximate completion time and confidential nature of participation, and requested involvement of all employers and employees, explaining its importance. No financial incentives were offered to encourage participation, so participants did so voluntarily and generously. Nevertheless, they will receive a detailed report with the results of this research.

Next, followed telephone calls, in-person visits, further emails sent from the architect’s professional body in Valencia (CTAV) and contact through the UPV School of Architecture’s employability office. We had to insist several times over a 3-month time period and obstacles confronted were many.

2.1.2 Participants

After considerable effort, we managed to collect 201 questionnaires from people working in 60 architectural companies. Although this represents 42% of the total target companies, we achieved a response rate of 57% in relation to the required sample. This response rate is close to Oluwatayo et al. (2018) at 59%, and higher than the 15% considered reasonable in the sector (Lai et al., 2016). Sample participants are diverse in terms of gender, age, job function, length of service and yearly income. The sample is balanced in terms of gender, with a slight majority of women (50.2%). Most participants are between 25 and 44 years old (61.2%), with developers being the most common role (30.8%). Women predominate in technical and administrative roles, while the majority of men are in leadership positions. In terms of tenure, women tend to have fewer years of service, whereas men are more represented in groups with more years of service. Regarding income, most individuals earn between 16,000 and 26,000 €, with this fact being more common among women. In fact, there are no women in the sample with incomes above 60,000 €, while some men do reach that level. Hence, as income increases, the proportion of men earning more is greater than that of women. Detailed socio-demographic characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Women n (%) 101 (50.2) |

Men n (%) 97 (48.3) |

PNTSa n (%) 3 (1.5) |

All n (%) 201 (100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 10 (5.0) | 9 (4.5) | – | 19 (9.5) |

| 25–34 | 36 (17.9) | 28 (13.9) | – | 64 (31.8) |

| 35–44 | 32 (15.9) | 26 (12.9) | 1 (0.50) | 59 (29.4) |

| 45–54 | 18 (9.0) | 18 (9.0) | 1 (0.50) | 37 (18.4) |

| 55 + | 5 (2.5) | 16 (8.0) | 1 (0.50) | 22 (10.9) |

| Job function | ||||

| Partner | 16 (8.0) | 11 (5.5) | – | 27 (13.5) |

| Managing partner | 11 (5.5) | 28 (13.9) | 1 (0.50) | 40 (19.4) |

| Chief Executive Officer | – | 5 (2.5) | – | 5 (2.5) |

| Team Leader | 5 (2.5) | 7 (3.5) | 1 (0.50) | 13 (6.5) |

| Project Manager | 7 (3.5) | 11 (5.5) | – | 18 (9.0) |

| Developer | 38 (18.9) | 24 (11.9) | – | 62 (30.8) |

| Administrative Assistant | 15 (7.5) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.50) | 19 (9.5) |

| Other | 9 (4.5) | 8 (4.0) | – | 17 (8.5) |

| Length of service (years) | ||||

| <1 | 17 (8.5) | 8 (4.0) | – | 25 (12.5) |

| 1–2 | 28 (13.9) | 25 (12.4) | 1 (0.5) | 54 (26.3) |

| 3–5 | 22 (11.0) | 15 (7.5) | – | 37 (18.5) |

| 6–11 | 14 (7.0) | 17 (8.5) | – | 31 (15.5) |

| 12–20 | 10 (5.0) | 16 (8.0) | 1 (0.5) | 27 (13.5) |

| 21+ | 10 (5.0) | 16 (8.0) | 1 (0.5) | 27 (13.5) |

| Annual individual income (€) | ||||

| <15. 000 | 27 (13.5) | 19 (9.5) | – | 46 (23) |

| 16.000–26.000 | 49 (24.4) | 29 (14.4) | 2 (1.00) | 80 (39.8) |

| 27.000–37.000 | 17 (8.5) | 20 (10.0) | 1 (0.50) | 38 (18.9) |

| 38.000–48.000 | 5 (2.5) | 10 (5.0) | – | 15 (7.5) |

| 49.000–59.000 | 3 (1.5) | 10 (5.0) | – | 13 (6.5) |

| 60.000+ | – | 9 (4.5) | – | 9 (4.5) |

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Prefer not to say their gender.

2.1.3 Data analysis

Data obtained through the Workplace PERMA-profiler were coded in SPSS version 25, and their means and standard deviations were calculated. Additionally, the normality test was performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic. All the data lack a normal distribution that is (p > 0.05), therefore, non-parametric tests were used, specifically the Mann–Whitney U test.

2.2 Qualitative methods

2.2.1 Procedure

To investigate the notion of happiness and understand the factors that people in the sample associate with happiness at work, the following two questions were included in the survey questionnaire: i) what does happiness mean to you? and ii) what factors make you happy in your work life? In addition, 22 semi-structured interviews were conducted with individuals who showed the most interest in the initial research phase. This type of interview was chosen for its value in qualitative research, being fundamental in exploring knowledge through dialogue, interaction, and the participation of individuals with diverse experiences (Kakilla, 2021; Caven, 2012). A schedule of topic areas to be covered was devised for the semi-structure interviews, to guide the interviewer and to encourage the interviewees to ‘talk around’ the topics rather than to give close-ended answers (Caven, 2012). The elaboration of the interview guide required extensive bibliographic review and is based on research by Ghosh (2020), Knox-Brown (2020), Ingram (2021), Edwards (2020), Mayberry (2018), and Morice (2019). It includes questions such as: What role does happiness play in your professional development? What are the satisfactions and dissatisfactions derived from your work? When you face challenges at work, what motivates you to keep going?

The sociodemographic and situational characteristics of the interviewee, the interview format, the time available, and participant’s disposition were also taken into account during the interview process. Hence the interviewer was flexible and gave quite a lot of freedom to the interviewee.

As regards participants’ involvement in this qualitative research phase, individuals were contacted via email based on the interest shown in the survey. They were informed about the need to record their words during the interview and gave consent. Interviews were carried out between September 19, 2023, and January 22, 2024, and were conducted in three formats: 60% in person, 36% by phone, and 4% via Zoom. Each interview lasted approximately from 30 to 60 min.

2.2.2 Participants

The open-ended questionnaire was completed by 201 participants (Table 1). The semi-structured interview involved the contribution of 11 women and 11 men with different roles within the architectural companies under study and different professions (Table 2). In the sample of 22 interviewees, efforts were made to achieve gender parity, although it was not a strict requirement. This parity was essential to equitably understand the perceptions of both genders, ensuring that men and women were adequately represented. Additionally, this balance was sought because the participation of both genders in the open-ended questionnaire had very similar figures. Moreover, the number of participants selected is related to the concept of data saturation, which, according to various studies, is typically reached between nine and 17 interviews (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022), with the most common saturation occurring within the first 12 interviews (Guest et al., 2006). In this context, the sample of 11 men and 11 women allows for a balanced reflection of the perspectives of both groups, thereby facilitating a direct comparison of their viewpoints.

Table 2

| # | Sex/Age/Marital status-children | Profession | Role within the company |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Women/35-44/a | Architect | Managing Partner |

| 2 | Women/45+/a | Architect | Partner |

| 3 | Women/35-44/b | Architect | Architect/Developer |

| 4 | Women/35-44/a | Architect | Managing Partner |

| 5 | Women/25-34/c | Architect | Intern |

| 6 | Women/35-44/a | Interior Designer | Developer |

| 7 | Women/18-24/c | Architect | Developer |

| 8 | Women/35-44/b | Architect | Managing Partner |

| 9 | Women/18-24/c | architecture student | Intern |

| 10 | Women/25-34/c | Architect | Developer |

| 11 | Women/25-34/c | Architect | Developer |

| # | Sex/Age/Marital status-children | Profession | Role within the company |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Men/35-44/a | Architectural Coatings Technician | Architectural Assistant |

| 2 | Men/45+/a | Draftsperson | Developer |

| 3 | Men/35-44/a | Industrial Designer | Managing Partner |

| 4 | Men/35-44/a | Architect | marketing /communications |

| 5 | Men/35-44/c | Architect | Managing Partner |

| 6 | Men/18-24/a | Architecture Student | Intern |

| 7 | Men/45+/c | Business Administrator | Managing Partner |

| 8 | Men/45+/a | Interior Designer | Managing Partner |

| 9 | Men/25-34/c | Architect | Developer |

| 10 | Men/35-44/a | Architect | Developer |

| 11 | Men/45+/d | Industrial Designer | Chief Executive Officer |

Characteristics of the interviewees.

Marital status-children = a Married or in a relationship/with children, b Married or in a relationship/without children, c Single/without children, d Divorced/with children.

2.2.3 Data analysis

The qualitative data were analyzed using MAXQDA 2024. Additionally, a brief exploration of the identified themes was conducted in the open-ended questions and interviews, considering the six phases suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006) for qualitative research.

3 Results

3.1 Qualitative findings

The first objective of this study was to describe how the individuals in the sample define happiness and to identify possible differences by gender. Table 3 shows a comparative analysis by gender of the 10 most frequently repeated words by participants when defining happiness. A word cloud and frequency of use have been used for its elaboration. Notice many of the terms used to define happiness are the same for both women and men. In fact, seven of the most commonly used ones are shared by both genders: peace, family, tranquility, enjoyment, and health, state, and time. For example, consider the similar use of “family” and “enjoyment.” Participant 32 (woman) mentions that happiness is “avoiding stress, being able to enjoy family, friends, and coworkers with a certain tranquility, and having time for personal hobbies, reading, and exercising.” Participant 26 (man) states, “enjoying oneself and personal relationships with those around me: family, friends, coworkers, etc.”

Table 3

| Women | Men |

|---|---|

|

|

| Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Word | Frequency | Word | Frequency |

| Peace | 20 | Time | 13 |

| Family | 17 | Tranquility | 13 |

| Good (well) | 16 | Family | 12 |

| Tranquility | 15 | Enjoy | 11 |

| Moments | 14 | Personal | 10 |

| Enjoy | 12 | Health | 8 |

| Health | 12 | Satisfaction | 8 |

| Time | 11 | State | 8 |

| Job | 11 | Balance | 7 |

| State | 11 | Peace | 6 |

Comparative analysis of the definition of happiness/number of occurrences by sex/open-ended questionnaire.

Word cloud from MAXQDA 2024.

However, there is some disparity in the order of priorities when talking about and referring to happiness. In fact, women tend to use the word “peace” more often than men, followed by “family.” For the men, the most frequently used terms are “time” and “tranquility,” mentioned by the same number of participants, followed by “family” and “peace” in the tenth place (see Table 3). It is also important to note that the word “work” appears in the ranking of the 10 most used words by the surveyed women, while among the men it is not found.

For illustration purposes, participant 23 (woman) defines happiness as “being able to live life as peacefully as possible with myself.” Meanwhile, participant 37 (woman) states, “happiness is living with peace and tranquility despite the circumstances. Happiness is living in coherence with oneself both personally and professionally. Living in alignment with oneself and working daily to improve. Knowing how to live day by day. Feeling that one is enough (despite the capitalist and consumerist world telling you otherwise). Finding an opportunity in everything you experience. Knowing what you like, doing it, and enjoying it.”

Regarding men, participant 1 (man) defines happiness as “having enough money to live decently and enough free time to enjoy it with my loved ones.” As for participant 62 (man) it is “a stable state of combined and lasting feelings of tranquility, satisfaction, hope, family and personal harmony, among others.”

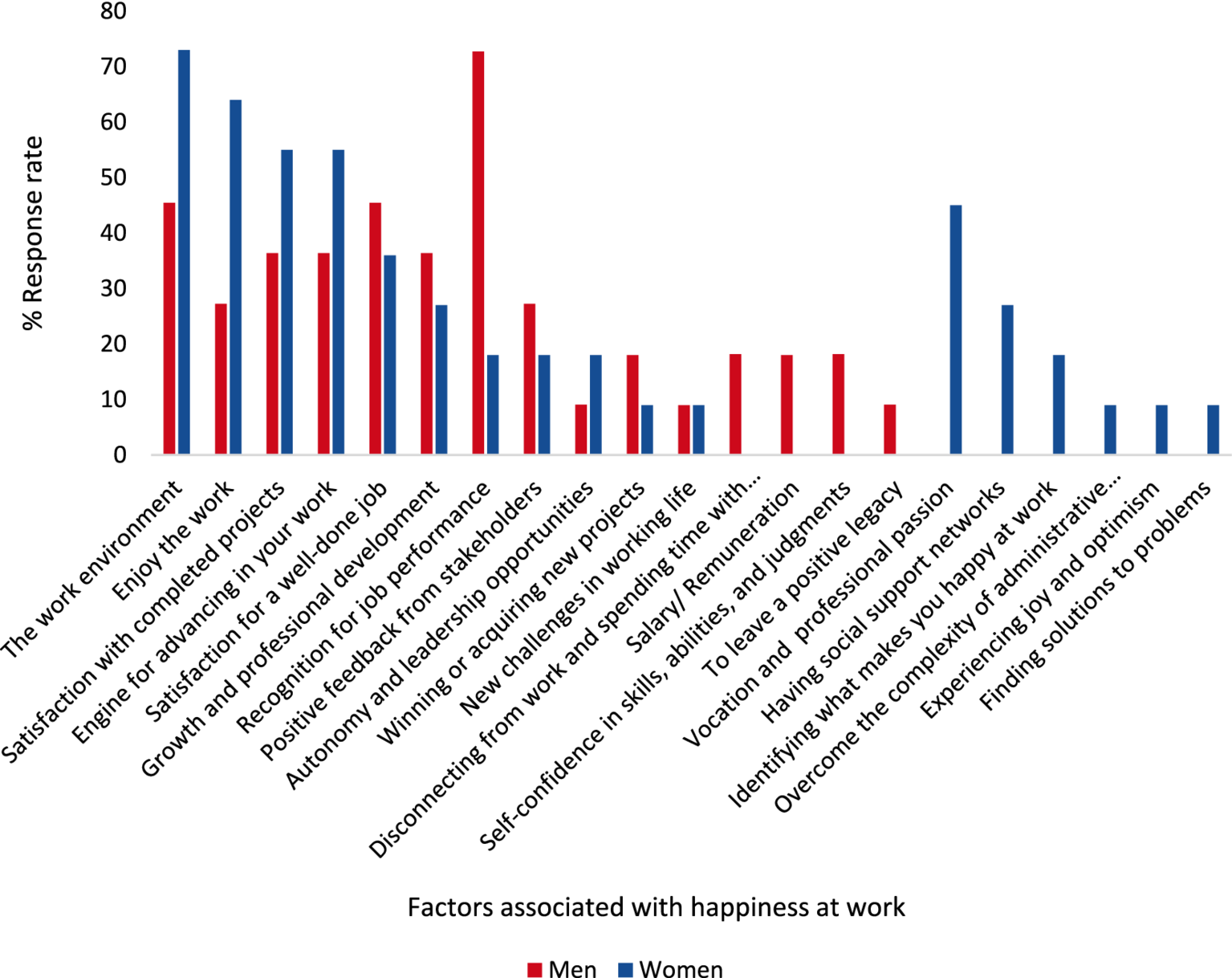

In relation to the elements associated with workplace happiness, only those identified with a minimum frequency of 5% of the interviewees, and words longer than 4 characters have been considered, while irrelevant words were excluded. Thus, 18 factors for each gender were obtained (Figure 1). Figure 1 shows that for women, the most significant factors related to happiness at work are the following in order of occurrence: work environment, mentioned by 29% of the surveyed female respondents, followed by colleagues 25%, projects 22%, salary/compensation/wage 19%, work schedule 16%, and team and flexibility with 14% of the responses. Regarding men, the most important are: recognition mentioned by 16%, colleagues 15%, followed by both salary/compensation/pay, being valued and goals/achievements, all mentioned equally by 14%, work environment 13%, growth 12%, and team 11% of the male participants.

Figure 1

Comparative analysis of workplace happiness factors by sex/open-ended questionnaire. Word cloud from MAXQDA 2024.

Notice 14 factors are shared by men and women: colleagues, salary/compensation/pay, being valued, work environment, team, flexibility, relationships, work schedule, projects, enjoyment, recognition, clients, time, and respect. From this perspective, the factors contributing to the work happiness of participant 74 (woman) are “Good salary, good work environment, and adherence to the schedule.” On the other hand, participant 56 (man) mentions, “Doing tasks that fulfill me and make me feel fulfilled. In my case, creative things that eventually get built. Also, good working conditions, a good work environment, and a fair salary.”

Likewise, gender differences in workplace happiness determinants are evident. 8% of women mention challenges, another 8% point to work-life balance, 6% refer to trust, and 5% cite creativity. On the other hand, goals, growth, dedication and learning are pointed out by 14, 12, 8 and 7% of male participants, respectively (see Figure 1). Participant 27 (woman) words while defining happiness at work illustrates well these elements: “having a good work environment above all, with respect, empathy, and closeness; being well paid and not monotonous, always with challenges to learn.” Similarly, participant 87 (man) defines it as “professional fulfillment based on meeting personal and company goals, learning new things and cultures, and receiving adequate compensation according to my expectations.”

Continuing with the study of qualitative data, now we move on to the analysis of the semi-structured interviews. The qualitative research software MAXQDA was used for this purpose, through which segments were created based on the responses obtained. Within these segments, a list of codes separated by gender was developed, considering the frequency of terms or themes, and excluding those that were redundant or irrelevant. The result was a coding system detailed at Figure 2.

Figure 2

Workplace happiness factors based on qualitative interviews.

For women, the most relevant elements related to happiness at work among the 17 constructed codes are a positive and mutually supportive work environment, followed by enjoying the work being done, 73 and 63% of the interviewee’s responses, respectively, are related to these two aspects. In contrast, aspects related to performance appreciation and contributions to the organization’s success stand out as the main elements in men’s perception of happiness at work out of the 15 codes constructed. In this regard, 73% of the interviewees used terms related to this aspect. This is followed by the team and work environment and satisfaction from a job well done, both with 46% of the interviewees.

It is important to highlight that there are similarities between men and women when talking about happiness at work. Factors such as the work environment, satisfaction with the work done, enjoyment of the process, opportunities for growth and professional development, and positive feedback are shared elements. Similarly, both genders consider happiness as the driving force that motivates them to move forward.

Yet, discrepancies were observed in the order of shared factors. For example, while 63% of women stated that enjoying what they do makes them happy at work, for men, this corresponds to only 27%. Likewise, the work environment, which is fundamental for women with 73% of the sample, represents 45% for men, placing it in second place with a marked distance from the first element. Disparities were also observed in some elements. For instance, women mentioned solving problems, overcoming administrative complexities, vocation, having support networks, and experiencing positive emotions such as optimism and joy. Men, on the other hand, mentioned income, leadership opportunities, disconnecting from work, self-confidence, and the hope of leaving a positive legacy as factors that make them happy at work.

In addition, in line with Garip and Kablan (2024), Kern et al. (2014) and Kern (2014), each element of the coding system was related to the five Workplace PERMA-Profiler dimensions, to which it was considered to correspond plus the happiness variable. From this, the code matrix emerged, from which the following table differentiated by gender was constructed (Table 4).

Table 4

| Women | PERMA | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoy the work you do Experiencing joy and optimism Feeling valued, recognized, and appreciated Identifying what makes you happy at work Positive feedback from stakeholders |

P | Enjoy the work you do Positive feedback from stakeholders |

| Finding solutions to problems Freedom, autonomy, and participation in decision-making Opportunities for creativity and to take on new challenges Overcome the complexity of administrative procedures and waiting times Satisfaction with completed projects |

E | Disconnecting from work and spending time with family Salary/ Remuneration Satisfaction with completed projects New challenges in working life |

| Having social support networks Positive and supportive work environment |

R | The team members and the work environment |

| Having vocation and experiencing professional passion | M | Self-confidence in skills, abilities, and judgments To leave a positive legacy |

| Opportunities for growth and professional development Satisfaction for a well-done job Winning or acquiring new projects |

A | Opportunities for growth and professional development Recognition for job performance Satisfaction for a well-done job Winning or acquiring new projects |

| Engine for advancing in your work | Hap | Engine for advancing in your work |

Elements encoded by dimensions of workplace happiness by gender.

The second research objective set forth aimed to investigate the perception that both women and men have about happiness at their workplaces. Through the comparative table of codes (Table 4), it has been found that two factors are perceived as fundamental by women. The first one is a positive and supportive work environment, which corresponds to PERMA’s positive relationships dimension. The second one is enjoying the work they do, included in PERMA’s positive emotions dimension. It is also worth noting that engagement and positive emotions dimensions are the ones with the highest number of related codes found for women. In comparison, for men, the essential aspects are recognition for their performance and contributions to company’s success, and satisfaction from a well-done job. Both correspond to the accomplishment or achievement dimension of the Workplace PERMA-Profiler. Additionally, for men’s workplace happiness, accomplishment is the dimension with the highest number of related codes, followed by engagement.

In summary, there are gender differences in happiness at work perceptions. On the one hand, women consider factors related to positive relationships and positive emotions dimensions as being the most important for their workplace happiness. In addition, engagement related factors also make women happy at their workplace. On the other hand, men place greater emphasis on aspects linked to the accomplishment and fulfillment dimension. In this regard, autonomy, leadership opportunities, satisfaction with the work they do, opportunities for growth and professional development, recognition, and achievements are fundamental in their perception of workplace happiness.

Table 5 clearly illustrates the previous findings by collecting the interviewees’ opinions on what makes them happy at work. These opinions have been organized according to the PERMA model, which includes: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment, and happiness.

Table 5

| Dimension | Code | Quote | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||

| Positive Emotions |

|

“If you are not happy at work, you have nothing, neither at work nor in your life… In general, what you have to do is to like your job, and if you like it, you are at ease, you work well, you have worthwhile colleagues, and they let you balance with your personal life. I believe that everything together is what makes happiness.”

Interviewee 6 |

“I think happiness is a very abstract concept. I believe I have moments of happiness, and that seems like a lot to me… We have peaks of high tension and high demands, but suddenly a laugh burst out with a joke or a prank… and you start to let off steam. I am very happy, I have feelings of pride and satisfaction, which might be close to happiness.”

Interviewee 8 |

| Engagement |

|

“We could relate enthusiasm to happiness. (…) It is super satisfying when a project is completed, if the result is as you intended, obviously you feel a lot of joy and also satisfaction that the client is happy. It is very exciting.”

Interviewee 4 |

“I am professionally ambitious, I am ambitious in almost everything and rarely conformist. So, I like challenges; they stimulate me in and of themselves. (…) Since I have to dedicate so many hours, I try to ensure that it satisfies me. Challenges satisfy me.”

Interviewee 5 |

| Positive Relationships |

|

“It’s a really great place on a human level. Coming to work is pleasant compared to other places, they tell me… This is a place where the atmosphere is very friendly, and there’s no competition. There’s no aggression among people. You endure difficult times, and low payment is easier to handle. …”

Interviewee 8 |

“The satisfaction of seeing my team working happily, hearing that someone outside said they love working with you. I like that. Being able to undertake projects for which I am ultimately responsible.

Interviewee 7 |

| Meaning |

|

“I think those who study architecture do it out of vocation, because otherwise, it’s really like saying you are crazy. Do not study it unless you really like it because at times I feel like we are playing the Hunger Games*.”

Interviewee 2 (*referring to public competitions) |

“The possibilities are whatever I want them to be, they depend on me. So sometimes I think, am I developing professionally as much as I would like? Because the company does not limit me, at least that’s what they have told me (…) I mean, in the end, I’m the one setting my own limits, I’ve never encountered a wall where the company says no, you cannot go beyond this.”

Interviewee 4 |

| Accomplishment |

|

“Well, it’s very exciting when you win a competition, or when the work is done, and people comment: ‘how beautiful!’”

Interviewee 1 |

“Feeling satisfied with good work, when you finish a project and see that users are enjoying it.”

Interviewee 11 |

| Happiness |

|

“Since I spend 8 h a day on this, I think if you are not doing something that pretty much makes happy… obviously, not every day. But if the balance is negative, I do not think it’s worth it.”

Interviewee 7 |

“Happiness at work is life. I believe that to convey something clean, honest, and well-formed, you have to be healed yourself. If you are not well, if you are bitter, you will transmit bitterness. That’s not always easy because you are not always perfect (…) I think it’s a profession where, if you are not emotionally strong, it’s tough, because it has (…) a very, very ungrateful side.”

Interviewee 3 |

Statements about happiness dimensions by gender.

3.2 Quantitative results

This research also aimed to determine the values of the Workplace PERMA-Profiler dimensions for people working in Valencia’s architectural companies and to find out if gender influences their job happiness levels. This objective was operationalized with 2 hypothesis. Table 6 shows the results obtained for the dimensions and factors of the Workplace PERMA Profiler.

Table 6

| P | E | R | M | A | Global | N | H | Lon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women n = 101 | Average | 7.38 | 7.79 | 8.01 | 7.66 | 7.59 | 7.63 | 4.48 | 7.22 | 3.49 |

| SD | 1.354 | 1.460 | 1.520 | 1.501 | 1.206 | 1.283 | 2.034 | 1.675 | 2.802 | |

| Men N = 97 | Average | 7.37 | 7.90 | 7.82 | 7.63 | 7.45 | 7.61 | 3.90 | 7.56 | 3.87 |

| SD | 1.533 | 1.538 | 1.463 | 1.748 | 1.268 | 1.349 | 1.743 | 1.528 | 2.656 |

Workplace PERMA-Profiler means and standard deviations by sex.

SD, Standard Deviation. Data from those who prefer not to disclose their gender (3 participants) were not considered.

PERMANH-L (Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, Accomplishment, Negative Emotions, Health, and Loneliness). Scoring scale for interpretation: 0.00–4.99 = Languishing; 5.00–6.49 = Suboptimal functioning; 6.50; 7.99 = Normal Functioning; 8.00–8.99 = High Functioning; 9.00–10.00 = Very High Functioning (Villarino et al., 2023).

The first hypothesis aimed to determine whether working men and women in these firms perceive themselves as flourishing and happy at work. Given that women’s overall mean value of happiness is 7.63 and men’s is 7.61, considered within a normal level of happiness (Berry, 2023; Villarino et al., 2023; Muñiz-Velázquez et al., 2022; Moog, 2021), Table 6 allows us to confirm Hypothesis 1. In addition, when comparing the results of Table 6 by gender, we find slightly higher averages for women in four out of the five dimensions. Therefore, the Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to check if there are statistically significant differences (see Table 7).

Table 7

| P | E | R | M | A | Global | N | H | Lon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | −0.404 | −0.731 | −1.055 | −0.348 | −0.702 | −0.141 | −2.148 | −1.496 | −1.148 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.89 | 0.03* | 0.14 | 0.25 |

Mann–Whitney U test/sex grouping variable.

* Statistical significance p < 0.05.

With respect to the second hypothesis relating to gender differences, higher scores were found among women on 4 parameters, but with no statistically significant differences. Nor are there significant differences in the health and loneliness factors (Tables 6, 7). However, a statistically significant difference was found in the factor of negative emotions (p = 0.032), with women (m = 4.48; sd = 2.034) scoring higher than men (m = 3.88; sd = 1.743). In summary, women tend to experience emotions such as anxiety, anger, or sadness at work more frequently than men. Therefore, having found differences in one of the Workplace PERMA-Profiler factors, our second hypothesis is partially supported.

Finally, considering that the negative emotions factor is composed of anxiety at work, anger, and sadness, to illustrate this finding, some female interviewee’s state: Interviewee 3: “I feel guilty because I’ve never had defined boundaries with work.” Interviewee 1: “The psychological burden you have… You have to be 100 % professional, 100 % a mother, and that’s incompatible.” Interviewee 9: “Everyone handles stress differently… For example, I’m a very nervous person; I sometimes get a bit anxious.”

4 Discussion

This research has been motivated by the need to highlight the close relationship between workplace happiness and social sustainability in the context of architectural firms, considering that human capital is the intangible asset that provides the greatest competitive advantage to an organization. Combining sustainability with workplace happiness involves addressing the impact of organizational actions on employees’ quality of life and well-being. In addition, understanding the variables in which men and women agree and disagree regarding workplace happiness can help companies manage this complex construct more effectively. Furthermore, knowing these differences might help businesses in designing a retention strategy that fits each gender.

According to the sample participants, we conclude that architectural companies’ workers in the city of Valencia often find that their work provides them with happiness due to the personal and professional development opportunities they find. This is largely because, in general, they perceive a coherence between their job expectations and what the job offers them, especially in terms of personal relationships, colleagues, team, and the overall work environment, with the latter being the most highlighted factor.

In terms of the distinction between men and women, this study identified that although there are no substantial differences in the notion of happiness, there are clear gender divergences in the factors that motivate workplace happiness. For women, peace, family, and tranquility are aspects that best align with their definition of happiness. Additionally, they prioritize the work environment, colleagues, and team. These aspects are predominant for 56% of the women in the sample, compared to 39% of the men. This finding aligns with Denegri et al. (2015), who in a study with young professional adults in Chile, found that women value more personal relationships due to the socially assigned role that emphasizes building stable and sincere bonds and a greater orientation towards sociability. Also, in line with Padilla-Walker et al. (2008), in their research with young adults, they identified that women tend to define themselves largely through their interactions and relationships with others. For this reason, a positive work environment fosters women’s happiness at work, whereas men place less importance on this aspect.

As for men, their definition of overall happiness prioritizes time, tranquility, and family, whereas in the workplace, the most highlighted factors for happiness are related to career development. Thus, recognition, appreciation, feeling valued, goals and achievements, dedication, learning, and professional growth are the main factors driving their workplace happiness. Analyzing these elements, 71% of the men’s responses are related to them, compared to 28% of the women’s.

Here it is necessary to emphasize two key aspects. First, Denegri et al. (2015) found that men focus on career success, seeking professional rewards and achievements driven by employment conditions and cultural conventions, which convey from childhood the need to demonstrate identity through success, competitiveness, power, self-control, and strength. Similarly, Padilla-Walker et al. (2008), concluded that men tend to see themselves by emphasizing their individuality and personal achievements. This could partly explain why, in the context of the architectural firms analyzed here, men associate primarily happiness at work with success in their professional careers.

Secondly, it is noteworthy that, although men prioritize career development as a source of happiness in the workplace, work does not appear in the ranking of the 10 terms that define overall happiness, unlike with women. Additionally, there appears to be a relationship between the word “time,” the most repeated term by men in their general definition of happiness, and professional development. This suggests that, given men are more focused on career advancement, “time” reflects the most aspirational aspect of their concept of happiness.

Furthermore, the research revealed that when it comes to happiness at work, women mentioned salary (19%), work schedule (16%), and flexibility (14%) more frequently compared to men, who mentioned them at (14%), (8%), and (9%) respectively.

Examining the salary variable in detail, Burone and Mendez (2022) summarize that women’s working conditions are often more unfavorable than men’s, as they receive lower wages, have more difficulty accessing quality employment, and occupying high-level, better-paid positions. This reality has been previously identified in the architectural sector (ACE, 2023; Ahuja and Weatherall, 2023; Sánchez De Madariaga and Novella, 2022; Oluwatayo, 2015; Navarro-Astor and Caven, 2018; Sang et al., 2007).

In this regard, it is important to mention that low wages affect both women and men in companies within the sector (Ashworth et al., 2024; Oyedele, 2013; Whitman, 2005) which adds to the phenomenon of wage inequality in the analyzed companies. In the sample profile (Table 1), it is observed that 23% of the sample earn less than €15,000 per year; being 14% of these women and 9% men. Additionally, 40% earn between €16,000 and €26,000 per year, with women representing 25% and men 15% of this group. These data illustrate that inequalities persist. De Blas and Estrada (2021) argued that in Spain, men’s average salaries were considerably higher than women’s. Anghel et al. (2019) also noted that gender wage equity was far from being achieved, as the wage gap widens with age, increases with the length of time spent at a company, is more pronounced in occupations and sectors with a predominantly male presence, and grows at the higher end of the wage distribution. In line with the above, it is essential to analyze this variable in depth and devote more attention to this issue in the future.

Fei et al. (2021) and Horry et al. (2022) suggest that the construction sector, where participant companies belong, has a crucial role in fulfilling many of the SDGs, especially those related to gender equality and the construction of sustainable cities. However, aware of the significant challenge that architecture firms still face regarding remuneration and wage equity, there is much room to further research on this topic.

Our qualitative results show a list of workplace happiness factors that have also been commented by other researchers such as: the work environment (Satuf et al., 2016), enjoying the work being done (Ugheoke et al., 2022), satisfaction (Stead et al., 2022; Locke, 1969), colleagues and social support networks (Benevene et al., 2019), opportunities for professional growth and development (Çivici and Yemişçioğlu, 2021; Satuf et al., 2016; Ramírez et al., 2019), and salary (Troiani, 2024; Stead et al., 2022; Ramírez et al., 2019), among others. All these elements, in turn, are closely linked to the PERMA dimensions.

On the other hand, the quantitative results of this study show that in Valencia’s architectural companies, women score higher on four dimensions of the Workplace PERMA Profiler, similar to Muñiz-Velázquez et al. (2022)’s findings in their study with public relations practitioners in Spain. However, no statistically significant gender differences have been found in any of the five dimensions. This is consistent with other studies that have used PERMA profiler. For example, Villarino et al. (2023) in a sample of university students in the Philippines, Hernández-Vergel et al. (2022) in a study with older adults in Colombia, and Pezirkianidis et al. (2023) in research with adults in Greece and Donaldson et al. (2023) in a cross-cultural study. Additionally, this result contrasts with Muñiz-Velázquez et al. (2022), who found significant differences in two dimensions: engagement and positive relationships.

Regarding the other instrument factors, in agreement with Muñiz-Velázquez et al. (2022), this research has found statistically significant differences in one of them. Women experience negative emotions more than men, which is consistent with Choudhari (2022) in his study with university students in India, with Burke and Minton (2019) in their research with adolescents in Ireland and also with Zuckerman et al. (2017) and Taylor et al. (2022).

Finally, regarding the level of happiness at work, the overall analysis of the instrument shows no significant gender differences. This result is consistent with Al-Taie (2023), Chaves et al. (2023), Kaur (2023), and Mousa (2020). Their studies, conducted with university professors in the United Arab Emirates, university students and employees at a university in Mexico, young adults in India, and public university professors in Egypt, respectively, support this conclusion. The reason for this could be because men and women increasingly, find happiness and dissatisfaction in similar aspects, due to the disappearance of traditional gender expectations in the workplace (Troiani, 2024; Brakus et al., 2022).

5 Implications and limitations

This study has several theoretical and practical implications. On the one hand, it makes three significant contributions that enrich the existing academic literature. Firstly, the Workplace PERMA Profiler instrument has been scarcely used in Spain, a notable example is Muñiz-Velázquez et al. (2022), who implemented it in the field of public relations. Our research is pioneering in its use of this instrument in the architectural sector, a field that has received little attention from academics and researchers, especially concerning the topic of happiness. By integrating these two elements, the study lays a foundation for future research. Moreover, its methodology can be replicated in the architectural sector and other sectors in various cities, both nationally and internationally, facilitating the comparison of results and contributing to a greater understanding of this topic. Secondly, although there are some studies addressing architects’ well-being and satisfaction (Oluwatayo, 2015; Oyedele, 2013; Cantonnet et al., 2011; Navarro et al., 2010; Sang et al., 2009), this research fills a gap by focusing on the different professional profiles that can be found in architectural firms. Thirdly, this study contributes to advancing research on happiness in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), acknowledging their crucial role in the economic development of the city and their importance as a source of workplace well-being.

On the other hand, a few practical implications are identified. Firstly, in the business environment it can help to understand how men and women define and experience happiness in the workplace, enabling companies to improve their levels of well-being. To achieve this companies should consider the subjectivity of happiness, the sociocultural environment, and what each individual values, such as professional success or personal relationships (Muratori et al., 2015; Padilla-Walker et al., 2008; Alarcón, 2001).

Secondly, analyzing negative emotions related to work, especially in women, offers a valuable opportunity for companies to examine their sources and design effective strategies to manage them, as this improves well-being, reduces absenteeism, and enhances cooperation, motivation, and innovation within companies (Yang et al., 2023; Taylor et al., 2022; De Neve and Ward, 2017; Gabini, 2017; Perandones et al., 2013; Fisher, 2010).

Thirdly, understanding the factors that influence the well-being of architects can help Valencia’s Territorial College of Architects (CTAV) to develop strategies to improve the professional and personal satisfaction of its members. Since architecture is a demanding and stressful profession, CTAV’s actions that promote well-being contribute to a better quality of life for its members, fostering their happiness and career satisfaction. In addition, the study could be of significant value to Valencia’s policymakers, as it explores an under-researched area: small and medium-sized architectural enterprises (SMEs), which contribute significantly to the local economy. The study not only analyzes workplace happiness in these SMEs but also takes a comparative approach that addresses crucial issues for the city, such as inclusion, equality, and sustainability.

Participation in this research was achieved without offering financial incentives, resulting in a sample of individuals who took part out of personal interest and intrinsic motivation. We value their time and effort and as a token of appreciation, we will ensure to share the results and detailed analysis with the participating companies, interviewed individuals, and the CTAV, also emphasizing the importance of their contribution to advancing knowledge in this field.

In addition, this study has limitations due to the small sample size and the fact that it was conducted in companies within the same sector and one city, which may limit the generalization of the results to other contexts. Furthermore, factors such as income level, education, job position, dependents, or years of tenure in the company were not explored in depth. The study focused solely on gender, intentionally excluding other socioeconomic factors to capture a comprehensive view of happiness. This is considered a limitation because the perception of happiness can vary between men and women depending on educational levels (Solomon et al., 2022; Bryant and Marquez, 1986). Parenthood can also affect men and women differently, so parental responsibilities could influence well-being (Rizzato et al., 2023; Pant and Agarwal, 2020; Ugur, 2020; Rico, 2012). Income levels between men and women may differ due to structural inequalities in the labor market and may be related to other important factors such as training opportunities, health, and career development, impacting happiness (Mert, 2020; Rico, 2012). Additionally, men and women may experience the work environment differently due to roles performed and gender expectations, which can include differences in promotion opportunities, salaries, and work-life balance (Taylor et al., 2022; Sloan, 2012). Finally, tenure in a company can influence the level of experience and the perspective men and women have about the organization and its culture. It may also be correlated with opportunities for professional development, promotion, hiring, and employee retention. These differences can affect how both groups perceive and experience their professional growth within the organization (Alonso, 2008; Anaya and Suárez, 2006). All these variables, which are also related to happiness in the workplace, will be addressed in subsequent studies. Another limitation was the authors’ decision to address only architectural companies while neglecting self-employed architectural firms. Needless to say that in Spain and many countries, aspects such as organizational culture, working conditions, development opportunities and economic incentives vary from one setting to another. This may also hinder the authors’ ability to generalize the results of the research. Nevertheless, these limitations offer opportunities for future research.

6 Conclusion

The results of this study show that although the terms used to define happiness present slight differences between men and women and the elements that contribute to happiness at work also vary, there are no significant differences in the happiness dimensions based on gender. Women tend to value a positive and supportive work environment more, while men place greater importance on career development. However, the gender of workers in Valencia’s architectural companies is not a predictor of happiness at work, according to the data obtained with the Workplace PERMA-Profiler instrument.

Nevertheless, the participants’ discourse and the medium-level scores in the instrument’s dimensions demonstrate that, although at work, a flourishing life does not depend on gender, companies still have much work to do to increase employees’ perception of happiness. Since work life is more satisfying when PERMA are increased, and negative emotions and loneliness are reduced, companies face a considerable challenge.

Finally, the differences found in negative emotions and salary lead to a reflection on inclusion and equity. If we truly want inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities (SDG 11), it is essential to bet on happiness in work environments, promoting equality and quality of life through better working and salary conditions.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because complete transcriptions of the semistructured interviews cannot be shared, since they are confidential. We do include some fragments in the manuscript to support our findings. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Elena Navarro-Astor, enavarro@omp.upv.es.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this research is part of a PhD carried out at the Business Organization Department of UPV. It involves the use of an online survey and semistructured interviews to workers of architectural firms. When the research plan was submitted and approved the authoritities did not ask for this approval and we started working. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AR-L: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. EN-A: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The researchers thank the study participants for taking the time to complete the instrument and to those who agreed to be interviewed. Special thanks also go to the partners and managers who opened the doors of their companies and contributed with their participation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ As the metaphor goes, the flapping of a butterfly’s wings can create a tsunami on the other side of the world.

2.^ Defining happiness is complex due to the multiple variables that constitute it (Alarcón, 2006). However, there is consensus regarding its hedonic character related to the pleasant or enjoyable and its eudaimonic nature, linked to flourishing or personal fulfillment (Fisher, 2010). When discussing happiness at work, it means finding meaning in the work performed and enjoying it (Seligman, 2011), recognizing its hedonic perspective, with elements such as satisfaction and the affective aspects that work generates for us. Likewise, its eudaimonic component, with factors such as personal growth, life project, and autonomy (Hervás and Vázquez, 2013).

References

1

Ahuja S. Weatherall R. (2023). “This boy’s club world is finally getting to me”: developing our glass consciousness to understand women's experiences in elite architecture firms. Gend, Work Organ.30, 826–841. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12921

2

Alam A. (2022). Investigating sustainable education and positive psychology interventions in schools towards achievement of sustainable happiness and wellbeing for 21st century pedagogy and curriculum. ECS Trans.107, 19481–19494. doi: 10.1149/10701.19481ecst

3

Alarcón R. (2001). Relaciones entre felicidad, género, edad y estado conyugal. Rev. Psicol.19, 27–46. doi: 10.18800/psico.200101.002

4

Alarcón R. (2006). Desarrollo de una Escala Factorial para Medir la Felicidad. Interam. J. Psychol.40, 99–106.

5

Alba M. I. (2018). Nadie hablará de nosotras… invisibilidad y presencia de la mujer en la arquitectura. Ábaco95-96, 30–39.

6

Alnachef T. H. Alhajjar A. A. (2017). Effect of human capital on organizational performance: a literature review. Int. J. Sci. Res.6, 1154–1158. doi: 10.21275/ART20176151

7

Alonso P. (2008). Estudio comparativo de la satisfacción laboral en el personal de administración. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ.24, 25–40. doi: 10.4321/s1576-59622008000100002

8

Al-Taie M. (2023). Antecedents of happiness at work: the moderating role of gender. Cogent Bus. Manag.10:2283927. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2023.2283927

9

Anaya D. Suárez J. (2006). La satisfacción laboral de los profesores en función de la etapa educativa, del género y de la antigüedad profesional. Rev. Investig. Educ.24, 521–556.

10

Andrews Kenney J. (2024). Improving school climate: The impact of a perma-based intervention on educators' well-being and emotional intelligence. Fairfield, CT: Sacred Heart University.

11

Anghel B. Conde-Ruiz J. I. De Artíñano I. M. (2019). Brechas salariales de género en España. Hacienda Pública Española.229, 87–119. doi: 10.7866/hpe-rpe.19.2.4

12

ACE (2020). The architectural profession in Europe 2020 ace sector study. Available at: https://www.ace-cae.eu/activities/publications/ace-2020-sector-study/ (accessed January 3, 2023).

13

ACE (2023). ABC: Gender balance, diversity & inclusion in architecture. Available at: https://www.ace-cae.eu/activities/publications/abc-gender-balance-diversity-and-inclusion-in-architecture/ (accessed May 19, 2024).

14

Ashworth S. McFadyen A. Clark J. Stead N. Gusheh M. Kinnaird B. (2024). Time & money: A guide to wellbeing in architecture practice; an outcome of the research project the wellbeing of architects: Culture, identity and practice. Melbourne, Australia: Parlour.

15

Barrera U. Abarca Y. Mellado J. Carpio W. Barreto O. Abarca R. (2021). Women and glass ceilings in the construction industry: a review: las mujeres y los techos de Cristal en la industria de la construcción: una revisión. South Fla. J. Dev.2, 4775–4790. doi: 10.46932/sfjdv2n3-072

16

Benevene P. De Stasio S. Fiorilli C. Buonomo I. Ragni B. Maldonado J. et al . (2019). Effect of teachers’ happiness on teachers’ health. The mediating role of happiness at work. Front. Psychol.10:2449. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02449

17

Berry Y. (2023). Examining the workplace wellbeing of elementary school teachers whose students participated in a social and emotional learning program. Malibu, CA: Pepperdine University.

18

Bilginoğlu E. (2020). Debunking the myths of workplace fun. Middle East J. Manag.7, 150–165. doi: 10.1504/mejm.2020.105945

19

Bosch A. Carrasco C. Grau E. (2005). “Verde que te quiero violeta. Encuentros y desencuentros entre feminismo y ecologismo” in La historia cuenta. ed. TelloE. (Barcelona: Ediciones El Viejo Topo).

20

Brakus J. J. Chen W. Schmitt B. Zarantonello L. (2022). Experiences and happiness: the role of gender. Psychol. Mark.39, 1646–1659. doi: 10.1002/mar.21677

21

Braun V. Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol.3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

22

Brundtland G. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: Our common future. United Nations General Assembly Document A/42/427. Available at: www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf (accessed May 29, 2024).

23

Bryant F. Marquez J. (1986). Educational status and the structure of subjective well-being in men and women. Soc. Psychol. Q.49, 142–153. doi: 10.2307/2786725

24

Burke J. Minton S. J. (2019). Well-being in post-primary schools in Ireland: the assessment and contribution of character strengths. Ir. Educ. Stud.38, 177–192. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2018.1512887

25

Burone S. Mendez L. (2022). Are women and men equally happy at work? Evidence from PhD holders at a public university in Uruguay. J. Behav. Exp. Econ.97:101821. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2021.101821

26

Butler J. Kern M. L. (2016). The PERMA-profiler: a brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing.6, 1–48. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

27

Cabanas E. Illouz E. (2023). Happycracia. Cómo la ciencia y la industria de la felicidad controlan nuestras vidas. Barcelona: Paidós.

28

Camps V. (2019). La búsqueda de la felicidad. Barcelona: Arpa y Alfil Editores, S.L.

29

Cantonnet M. L. Iradi J. Larrea A. Aldasoro J. C. (2011). Análisis de la satisfacción laboral de los arquitectos técnicos en el sector de la construcción de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Rev. Constr.10, 16–25. doi: 10.4067/S0718-915X2011000200003

30

Carrasco S. Perez Lopez I. (2024). Linking education and practice gaps for inclusive architecture in the AEC industry. Archnet-IJAR, Advance online publication. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-11-2023-0297 (ahead-of-print).

31

Caven V. (2012). Agony aunt, hostage, intruder or friend? The multiple personas of the interviewer during fieldwork. Intang. Cap.8, 548–563. doi: 10.3926/ic.276

32

Chaves C. Ballesteros-Valdés R. Madridejos E. Charles-Leija H. (2023). PERMA-profiler for the evaluation of well-being: adaptation and validation in a sample of university students and employees in the Mexican educational context. Appl. Res. Qual. Life18, 1225–1247. doi: 10.1007/s11482-022-10132-1

33

Choi S. P. Suh C. Yang J. W. Ye B. J. Lee C. K. Son B. C. et al . (2019). Korean translation and validation of the workplace positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (PERMA)-profiler. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med.31:e17. doi: 10.35371/aoem.2019.31.e17

34

Choudhari V. N. (2022). Positivity at work-place: a comparative investigation. Indian J. Nat. Sci.12, 38160–38168.

35

Çivici T. Yemişçioğlu Ş. (2021). One of the barriers that female architects face in their career development: glass ceiling syndrome. Online J. Art Des.9, 185–195.

36

Clark R. Plano Clark V. P. (2022). The use of mixed methods to advance positive psychology: a methodological review. Int. J. Wellbeing.12, 35–55. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v12i3.2017

37

CNAE (2009). Clasificación Nacional de Actividades Económicas. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística INE. Junio, 2008. Available at: https://www.ine.es/daco/daco42/clasificaciones/cnae09/notasex_cnae_09.pdf (accessed December 5, 2022)

38

De Blas R. Estrada B. (2021). Género y desigualdad laboral: la brecha salarial como indicador agregado. Documentos de trabajo (Laboratorio de alternativas) 209. Spain: Dialnet.

39

De Neve J. Ward G. (2017). Happiness at work. World happiness report 2017. Saïd Bus. Sch. Res. Pap2017:07. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2943318

40

Denegri C. M. García J. C. González R. N. (2015). Experiencia de bienestar subjetivo en adultos jóvenes profesionales chilenos. Rev. CES Psicol.8, 77–97.

41

Donaldson S. I. Donaldson S. I. (2020). The positive functioning at work scale: psychometric assessment, validation, and measurement invariance. J. Well-Being Assess.4, 181–215. doi: 10.1007/s41543-020-00033-1

42

Donaldson S. I. Donaldson S. I. McQuaid M. Kern M. L. (2023). The PERMA+ 4 short scale: a cross-cultural empirical validation using item response theory. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol.8, 555–569. doi: 10.1007/s41042-023-00110-9

43

Edwards S. (2020). A qualitative study: perceptions, racial inequality, intersectionality-underrepresentation of black women in intercollegiate leadership. Scottsdale, AZ: Northcentral University.

44

Fehrenbacher A. E. Patel D. (2020). Translating the theory of intersectionality into quantitative and mixed methods for empirical gender transformative research on health. Cult. Health Sex.22, 145–160. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1671494

45

Fei W. Opoku A. Agyekum K. Oppon J. A. Ahmed V. Chen C. et al . (2021). The critical role of the construction industry in achieving the sustainable development goals (sdgs): delivering projects for the common good. Sustain. For.13:9112. doi: 10.3390/su13169112

46

Firmansyah D. Wahdiniwaty R. (2023). Happiness management: theoretical, practical and impact. Int. J. Bus. Law Educ.4, 747–756. doi: 10.56442/ijble.v4i2.244

47

Fisher C. (2010). Happiness at work. Int. J. Manag. Rev.12, 384–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00270.x

48