- 1Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

The European Union's “100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission” launched in 2021, urges European cities to collaborate with local stakeholders to develop transition plans (Climate City Contracts) aimed at achieving climate neutrality by 2030. This initiative represents the largest urban transition experiment to date, offering valuable lessons for future urban transformations. This article assesses cities' initial efforts to implement the transition governance model through the lens of the analytical framework that focuses on four key functions drawn from the transition management literature: coordination, co-creation, anchoring, and governance learning. Using a mixed-methods approach, the study examines the extent to which these functions have been operationalized, and the early experiences cities have had in applying them. This study presents findings on how cities govern transitions and underscores the difficulties of coordination and management when delegated to municipalities instead of practitioners or researchers. The Cities Mission provides a unique opportunity to study multiple cross-sectoral urban transition experiments, as each city customizes its approach to local conditions. To enhance urban climate transitions, it is imperative to examine transition governance within its inherent context, enabling the insights gained to offer substantial and thorough guidance to municipalities and significantly advance the practical implementation of transition management theory. A comparative analysis of these evolving transition scenarios deepens our understanding of how cities operationalize transition management and the complexities involved in long-term urban sustainability transformations.

Highlights

• The paper introduces the EU Cities Mission's Climate City Contract governance model and assesses its implementation by European cities

• Four key functions drawn from transition management are assessed: coordination, co-creation, anchoring, and governance learning

• Cities are able to more easily adopt coordinating and co-creation functions than anchoring and governance learning

• Cities struggle with private sector investment and co-financing models

• Time pressure related to the mission and limited resources at the local level hinder long-term governance planning

• Adaptive governance and reflexive learning are key to long-term success of transition plans

1 Introduction

Currently, urban environments are responsible for nearly 70% of the global carbon footprint, of which the 100 largest emitting cities alone account for around 18% (Moran et al., 2018). Transforming the urban economy sustainably means offering zero-emission alternatives for services, products, and production processes that involve GHG emissions. Since municipalities lack the means and capacity to develop and finance innovation on such a large scale, and achieving sustainability in urban settings requires not only significant financial investment but also the active involvement of various local stakeholders, including public and private sectors, citizens, and civil society groups (Klaaßen and Steffen, 2023; Steffen, 2021; Betsill and Bulkeley, 2007). To meet this challenge, cities need to reform their governance practices and explore new models and approaches that go beyond municipal boundaries and enable shared governance (Khan, 2013).

Recognizing the importance and urgency for cities to find new ways to manage transitions, the European Commission decided to establish its biggest urban transition experiment yet as part of the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. It launched the “100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission” (or “the Cities Mission”) in 2021 and selected 112 “mission cities” across Europe to become climate neutral by 2030 through systemic and transformative changes. These cities are positioned as experimental hubs for testing and scaling innovative climate solutions, aiming to leverage technological transformation and multi-stakeholder approaches, to inspire urban transition accross Europe (NetZeroCities, 2022). The Cities Mission provides guidance to cities on how to develop a governance model to tackle climate change (Moran et al., 2018; Ulpiani et al., 2023). This governance model combines elements of transition management to provide a basis for long-term collaboration among local stakeholders striving for climate neutrality, while remaining flexible to different urban contexts.

To accelerate the necessary actions, each city is expected to develop a transition agenda presented in a so-called Climate City Contract (CCC) that is designed to provide a clear outline of actions to be taken, as well as an overview of commitments to the process. While not actually a contract in the legal sense, its primary goal is to ensure a strong commitment to the transition work at the highest levels in each municipality, and from other urban stakeholders. Once completed, cities are accredited the Mission Label which is intended to improve access to EU, national, and regional funding and finance sources, particularly private investment through the Climate City Capital Hub (European Commission, 2024). As the Cities Mission is a novel program, its effects, and those of the CCC as its proposed governance model, are still unknown (Shabb and McCormick, 2023). However, the early progress of cities setting up their transition governance model and developing their transition plans in the CCC can shed light on processes of local transition governance in practice. Since the launch of the Cities Mission, several articles have examined the cities efforts by focusing on the concept of carbon-neutral cities (Huovila et al., 2022) and the financing of their implementation (Ulpiani et al., 2023). However, no study has yet explored how the CCC governance model has been applied in practice and what key lessons can be drawn for urban transition management.

To answer the research question, this academic paper draws on theories of transition management (TM; cf. Loorbach, 2010; Roorda et al., 2014; Janssen et al., 2021; Haddad et al., 2022) to provide empirical evidence on how transition management principles work in real urban contexts. It provides insights into the adaptability and flexibility of governance models when applied to complex urban systems. In addition, the study helps to identify potential mismatches between theoretical expectations and practical realities in urban climate governance, contributing to a deeper understanding of how governance innovations such as CCC can bring about systemic change in urban environments.

The article is organized as follows. First, we describe the transition management governance model and the extent to which the CCC governance model mirrors it. Next, we introduce four functions that provided the key pillars of transition governance in the Cities Mission, and which form the main focus of our analysis. In the methodological section we introduce our research methods and analytical framework. In the results section we present our research findings along the four main transition functions. Finally, in the last two sections we draw general conclusions and summarize our contribution to the method portfolio of transition management.

2 Theoretical framework: toward a new urban governance model

Transition management is one of the key approaches within the broader field of urban sustainability transitions (Ernst et al., 2016; Walsh et al., 2006). Over the last two decades, it has been applied to a wide range of sustainability issues, policy contexts and geographical scales, and provides a compelling approach for managing sustainability transitions (Frantzeskaki et al., 2018). Transition Management (TM) is a prescriptive governance model that aims to influence government action in a way that enables social change to sustainability by moving toward new, innovative forms of governance that involve the interaction of many actors from different parts of society (Frantzeskaki et al., 2012; Nevens et al., 2013). It is based on participatory and reflexive strategic planning by enabling frontrunners to become agents of the change and co-create transformative solutions (Frantzeskaki, 2022). It offers a portfolio of tools to enable changes in practices and structures toward sustainable development targets (Loorbach, 2010; Nevens and Roorda, 2014; Loorbach et al., 2024). Studies on its diverse applications have demonstrated that transition management has the potential to be an adaptable and valuable framework (Hölscher and Frantzeskaki, 2020; Nevens and Roorda, 2014; Kumar, 2021; Loorbach, 2007, 2010; Loorbach et al., 2017, 2024). However, its critics also claim that its application in real life can often still result in a shallow adaptation (Nagorny-Koring and Nochta, 2018), partly because of tensions between the desire for radical change and the need to cooperate with status quo-oriented actors (Wittmayer et al., 2016).

The TM model proposes a series of mutually reinforcing steps and related activities (Roorda et al., 2014; Haddad et al., 2022):

1. Setting the scene—as a first step, a transition team is formed to guide and facilitate the transition management process.

2. Exploring the local dynamics—the transition team conducts a systems and actor analysis to help set the scene for a transition arena involving a diverse group of local change agents

3. Framing the transition challenge—the transition arena creates a common problem frame.

4. Envisioning a sustainable city—the transition arena then develops a shared vision for a sustainable city.

5. Reconnecting the long- and short-term goals—the transition arena develops the transition pathways to the envisioned future, which are then summarized in a transition agenda.

6. Engaging and anchoring—the transition arena makes the transition agenda public so that others can adopt and adapt it.

7. Taking action—initiating transition experiments in line with the transition agenda.

As a separate task, monitoring and evaluation supports reflexivity and reflexive learning throughout the process (Nevens et al., 2013).

The transition arena is at the heart of the transition management process, a temporary setting that includes 15–20 frontrunners from different parts of local society with various competences, who participate in a series of meetings to envision a sustainable future and develop transition plans for its realization (Roorda et al., 2014). Frontrunners are not just involved as stakeholders, but as individuals who are empowered change agents and have the ambition to lead local transition processes (Loorbach, 2007; Hölscher et al., 2019).

The transition arena is a form of network governance in which participants develop transition pathways, which are not detailed plans, but rather inspirational stories that contain ideas for action. These are then collected in the transition agenda, which is not a roadmap to climate neutrality, but rather a compass for future strategies and actions. It is not intended for implementation, but rather as an inspiration for transition (Roorda et al., 2014). An important characteristic of network governance is that actors are interdependent and cannot implement decisions on their own. However, this also makes policy implementation challenging, as actors tend to implement measures only to the extent that they are beneficial to their own objectives (Khan, 2013).

Parts of the transition agenda can be operationalized by identifying short-term actions and implementing transition experiments (Rotmans and Loorbach, 2009). They should illustrate an envisioned transition pathway that takes a “societal challenge as a starting point for learning aimed at contributing to a transition” (Van den Bosch, 2010, p. 58). This aligns with the concept of meta-governance, where governments organize conditions for self-organization and experimentation, as discussed by Kuhlmann and Rip (2018). Transition experiments can be both newly developed projects or already planned/ongoing innovative experiments that align with a pathway and support the transition process and they have become a prevalent mode of response, creating new possibilities for governance and political subjectivities (Wittmayer et al., 2018; Bulkeley, 2023).

After the agenda is set the arena participants are expected to return to their networks and induce wider societal changes by inspiring with the transition pathways they developed (Wittmayer et al., 2018), which is called the “Engaging and Anchoring” step, the least elaborated step of all. While much of the literature has focused on the outputs and outcomes of TM processes in cities, less attention has been paid to the capacities necessary for local actors to design and implement these processes, including the institutional knowledge and skills needed to foster meaningful stakeholder engagement and strategic co-creation (Loorbach et al., 2017).

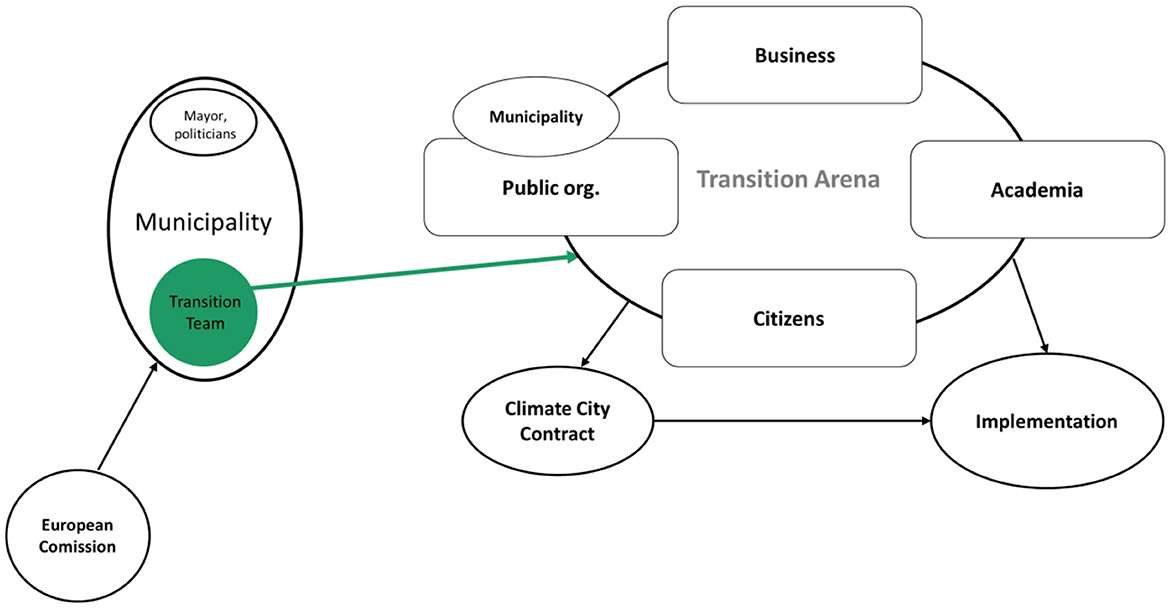

The expectations of the Cities Mission with regards to the governance framework that cities should establish (as detailed in Littek and Wildman, 2021) shares similarities (including but also going beyond terminology) with the TM model and its process structure. As we visualized it in Figure 1, the Cities Mission invited municipalities to establish a transition team that enables and coordinates the agenda writing process by setting up a transition arena. This transition arena is tasked with collectively developing climate action and investment plans. The transition arena should consist of quadruple helix groups of local stakeholders including business, academia, civil society and public organizations (one of which is the municipality itself). The municipality is thus both the catalyst (or coordinator) of the process and one of the stakeholders in the transition arena, whose purpose is, on the one hand, to develop the urban transition plans and, on the other hand, to implement the transition plans and anchor stakeholders' commitment.

The transition agenda developed by the cities forms the basis of the Climate City Contract (CCC), a document signed by city mayors and key stakeholders, which contains climate action and investment plans. The CCC is not a legally binding contract, but rather a declaration of intent, signifying the signatories' commitment to contribute to making the city climate neutral. The CCC is expected to be developed and regularly updated through an iterative process together with local stakeholders, with a particular emphasis on private sector investment, as opposed to relying solely on traditional sources of municipal funding (European Commission, 2024). However, the focus of the Cities Mission is not solely on the CCC document, but on transformative, systemic change; i.e., enabling a more holistic approach to the way cities manage their climate policies—which the CCC governance model enables. The main idea of the Cities Mission is that if different stakeholder groups are to actively partake in the implementation of the transition pathways and to design and invest in climate-friendly solutions accordingly, they need to be involved from the outset of the planning process. So the municipality involves representatives of local stakeholder groups from the very beginning of the process. This way, both planning and implementation become part of the joint work in the arena. It also results in the broadening of the range of participants involved and the process itself, making the arena the backbone of transition governance throughout the entire transition process. Consequently, with the CCC governance model the Cities Mission aims to form the backbone of long-term collaboration between local stakeholders to achieve climate neutrality, while remaining flexible to be applied across a wide range of cities.

To explore how the CCC governance model has been applied in practice, we have structured our analysis around four key functions that we have identified from TM literature as key to enabling urban transitions. By focusing on key functions rather than prescribed steps, we wanted to recognize that cities can use a variety of solutions to achieve these functions, depending on local circumstances. These are further detailed below.

2.1 Coordinating function

Like the TM model, the CCC governance model regards the initiation and coordination of transition processes as a crucial function, which is similarly assigned to the transition team (Nevens et al., 2013). As this model considers municipalities the main entity responsible for creating the framework to manage the local climate transition, they are expected to set up the transition team, although it can include members from outside the municipality either partially or entirely (Littek and Wildman, 2021; NetZeroCities, 2022). The transition team's objective is to mobilize all interested parties and industries of the local community to collaborate and synchronize their endeavors to devise comprehensive solutions that significantly reduce emissions.

To this end, the transition team establishes and supports the transition arena, composed of the quadruple helix organizations responsible for developing the CCC agenda. Thus, just like in the TM model, the transition team needs to identify stakeholders, onboard them into the transition arena and then organize their ongoing collaboration. The transition team's main role in the arena is to facilitate the co-creation of transition plans, facilitate transition experiments and support internal communication and decision-making.

2.2 Co-creating function

The co-creating function refers to the collaborative efforts of stakeholders in the transition arena to develop joint transition plans. However, it involves representatives of stakeholders from the quadruple helix groups instead of individual frontrunners, to ensure that both the development of transition plans (summarized in the CCC agenda) and their implementation are the responsibility of the same actors. It is important to note that the operation of the transition arena goes beyond the development of transition plans. As the CCC governance model focuses on implementation and long-term stakeholder engagement, the ambition of the arena is to make shared governance a long-term framework for local transition governance.

While the transition arena can take many forms, certain features to ensure smooth operation and active participation should be built into all arena types (Roorda et al., 2014; Janssen et al., 2021). This process involves:

1. Stakeholder engagement: Incorporating representatives from the quadruple helix—business, academia, civil society, and public organizations.

2. Systemic planning: Developing comprehensive, ambitious plans that address interconnected urban challenges.

3. Collaborative decision-making: Establishing frameworks for co-creation, including defined goals, roles, and communication channels.

4. Trust-building: Fostering a shared identity and community among participants to enhance commitment and effectiveness.

2.3 Anchoring function

While the TM model sees the involvement of local organizations as a step following the development of transition plans (Roorda et al., 2014), the CCC governance model places a strong emphasis on the involvement of the quadruple helix stakeholder groups in each phase of the transition process (Littek and Wildman, 2021). Anchoring in this case refers to ensuring the adoption and implementation of transition plans by local stakeholders (Roorda et al., 2014), which can be achieved by developing and nurturing their involvement from the beginning throughout the entire transition process. Organizational commitment can be demonstrated early in the process through the extent to which they take ownership of the action and investment plans articulated in the CCC agenda. This ownership would require changes to the internal planning and budgeting of organizations so that the plans developed jointly in the CCC agenda can become part of the individual plans of every organization.

As the municipality has a special role to play in governing local transitions, both as a member of the quadruple helix groups and as a facilitator or supporter through the transition team, anchoring municipal commitment and engagement is crucial to the success of urban transformations (Smedby and Quitzau, 2016). This involves enabling local governments to take the lead externally in managing transitions and internally to make climate an overarching consideration in all decision-making. Key to anchoring is the level of political and leadership support for the transition team, and the extent and level of engagement of different municipal departments in the CCC process. Political support is further reflected in the form of regular contact with administrative and political leaders to raise ideas that allow for going beyond pre-defined pathways. Nevertheless, focusing just on implementing transition measures at the city level is insufficient. It is crucial to ensure that local and national initiatives are synchronized and that cities receive necessary assistance from their respective national administrations (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005; Ehnert et al., 2018).

2.4 Governance learning function

Governance learning refers to the learning process of arena stakeholders as well as policymakers and other local and national level government actors about the development and implementation of participatory planning procedures, with the aim of enhancing their efficacy for guiding climate transitions (Newig et al., 2016). Actors can acquire knowledge deliberately, for example, by conducting policy experiments and evaluating evidence systematically regarding implementation and effects (Sabel and Zeitlin, 2010; Sanderson, 2002). Alternatively, learning can occur incidentally or intuitively, through trial and error or the spontaneous assimilation of experience (Bennett and Howlett, 1992).

Learning is an essential function that accompanies transitions and is an iterative process including a series of trials and errors (Swilling and Hajer, 2017). This requires the constant reflection of all stakeholders on individual and group efforts (Dóci et al., 2022). The manifestation of progress may not be immediately apparent, as it involves the gradual alteration of individuals' mental frameworks and approaches, which serve as the foundation for significant transformations (Rohracher et al., 2023).

Learning therefore is an essential part of the CCC process that needs to be systemically induced and ensured in each city (Cartron et al., 2023). Thus, the transition team, as an intermediary, also has a role to play in supporting learning within the municipality and the quadruple helix organizations, for instance in acquiring collaboration and network governance capabilities and promoting structural organizational changes that enable these capabilities.

3 Methodology

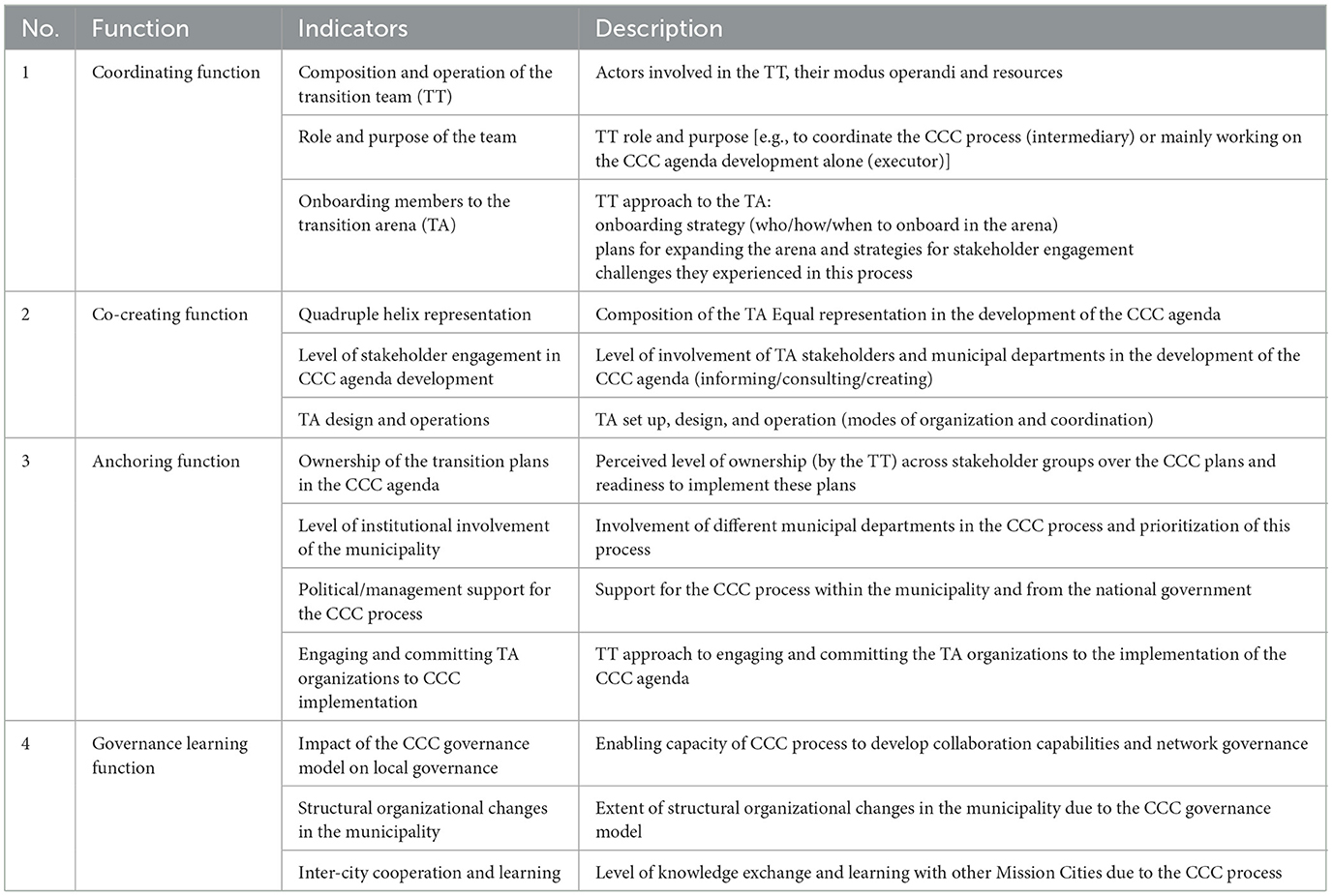

To study how the CCC governance model was put into practice, our analysis explored whether cities could establish the most important functions for enabling urban transitions. These functions and accompanying indicators are summarized in Table 1.

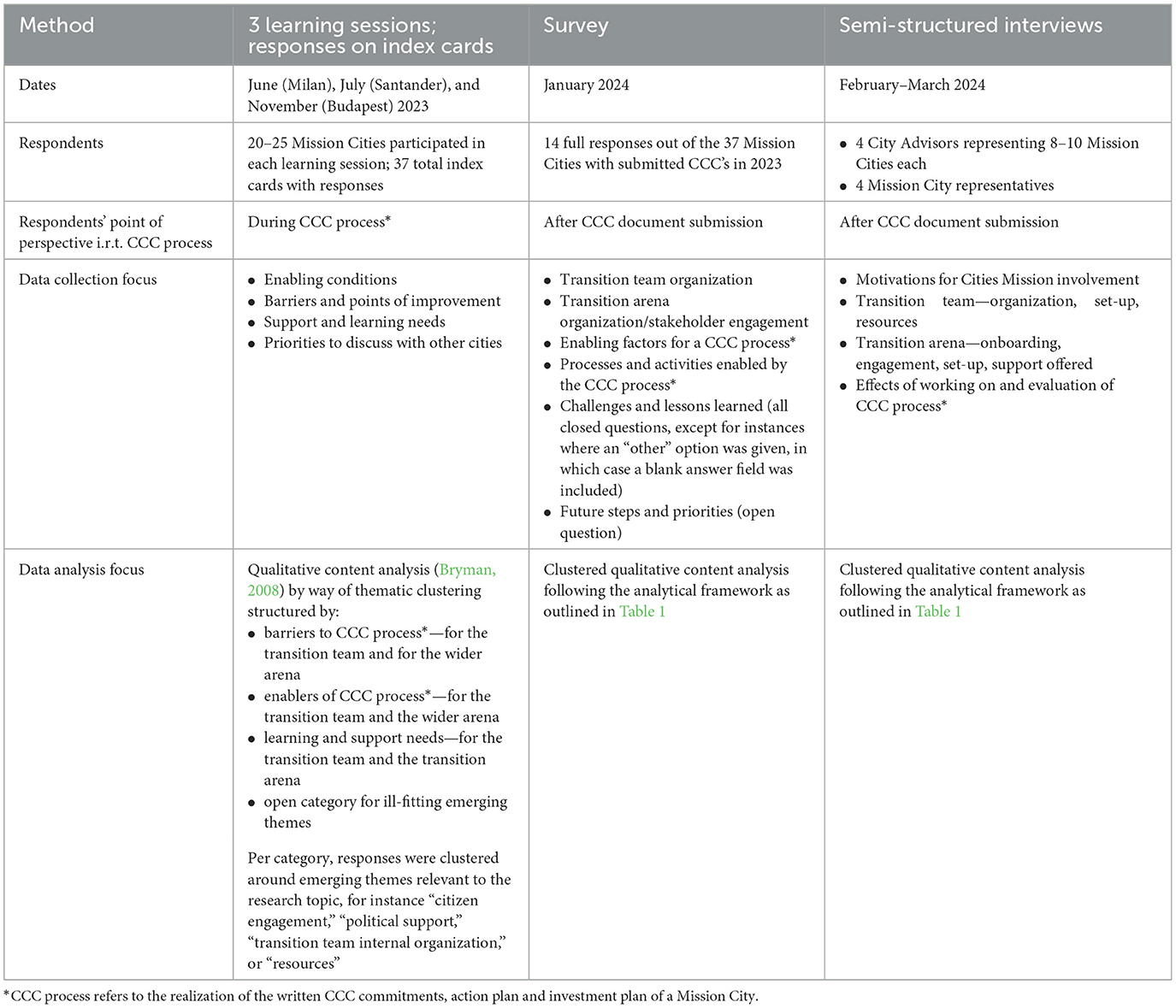

The analysis consisted of a qualitative research design, using a mix of data collection methods. Data collection started with inviting Mission City feedback on their experiences with the CCC governance model during the realization of their CCC commitments, action plan and investment plan—this feedback was collected at three in-person learning sessions with transition team representatives—followed by a survey and follow-up in-depth interviews after the submission of the CCC document. Appendix A outlines in more detail the collection and analytical approaches we used per research method.

First, data was collected at three seasonal schools organized by a research consortium that supports cities in their CCC process, in the run up to the submission of their CCC. Participants in these 3 days in-person workshops in 2023 are all part of their cities' transition team. Representatives of around 20–25 cities participated in each of these schools, where CCC reflection sessions were organized. Here, feedback was collected on the cities' individual CCC processes, discussing their challenges, enabling conditions, learning and support needs, and priorities. A total of 37 responses were collected between June and November 2023. Qualitative content analysis was used for sensemaking (Bryman, 2008), as preparation for the survey and more in-depth qualitative interviews.

Second, a survey was conducted among the first two groups of cities that submitted their CCC agenda to the European Commission. Out of 37 cities who submitted their CCC in 2023, 14 responded in full to the survey. Survey questions focused on transition team organization, transition arena organization/stakeholder engagement, enabling factors, processes, and activities enabled by the CCC process, challenges and lessons learned, and future steps and priorities.

Third, interviews were held with leaders of transition teams from four cities and with four City Advisors who support cities with their CCC process, each representing around 8-10 cities. City interviewees were self-nominated in response to the survey and can thus show a bias toward exhibiting successes and best practices. City Advisors were selected to represent a regional variation of cities across Europe. Interviews followed a semi-structured format covering the topics outlined in the analytical framework designed differently for case cities and city advisors, but both exploring how the cities applied the CCC governance model. Because of confidentiality considerations we cannot share the name of the cities, and we will refer only to the interviewees as city representative or city advisor.

To validate and bring together the results from the various data sources, two validation sessions were organized with all researchers included, plus an external researcher not previously involved in the coding, clustering, and analysis, with the intention to improve upon the qualitative content thematic analysis. Each validation session lasted approximately 1,5 hours and was structured around the key themes identified by the lead researchers. Upon conclusion of integrating all research results, an additional sensemaking workshop was organized with all researchers involved as well as team members from the consortium working on the CCC support, for additional analysis and reflections from the practice of city support with the CCC model implementation. In this way, thematic gaps as well as avenues for further research were identified for inclusion in this paper.

4 Results

While mission cities were selected based on an expression of interest, our findings indicated a broad variety in experience and expertise of cities in regard to climate action planning and implementation, as well as motivation to take part in the EU Cities Mission. Yet, both the CCC agenda and governance model were generally regarded to facilitate a strategic approach toward achieving climate-neutrality. This comprehensive approach allowed cities to prioritize actions tailored to their specific contexts and leverage the CCC to address systemic obstacles hindering progress toward climate-neutrality. As such, cities also expressed that the mission helped them to move beyond typical project-based approaches to a more systemic approach. As a city representative remarked: “You're moving away from just incrementally moving forward. So, if we had to get there, that would probably mean we would have to transform the system in some way. And so, what are the steps we can take toward transforming the system?” Some cities, however, felt that participation in the CCC process required a significant amount of unnecessary work and extra administration, which they perceived as a barrier to their development. A recurring theme in our interviews was the need to strike a balance between clear guidelines and the flexibility to adapt locally.

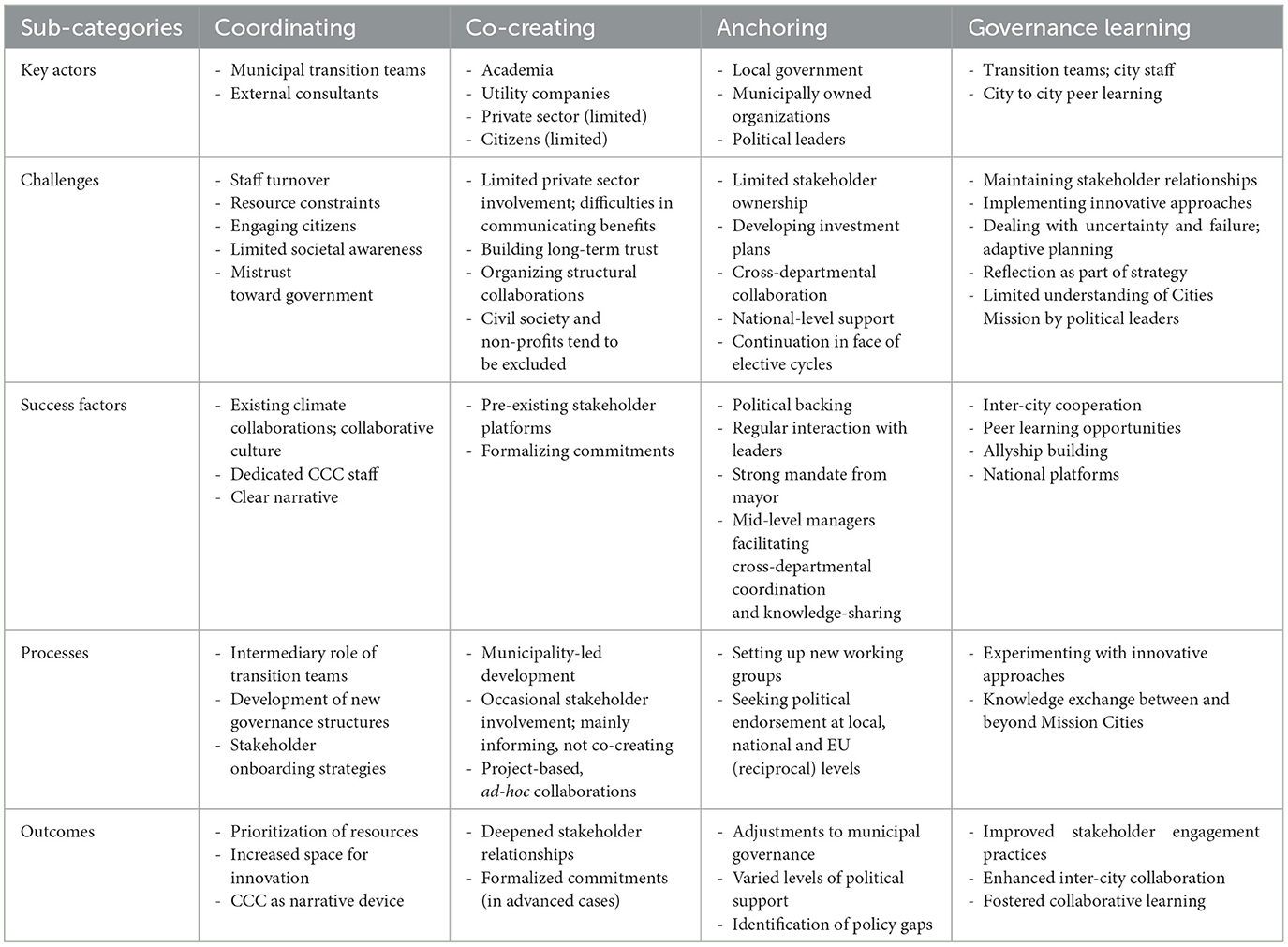

In the following, we explore how cities established the different functions of the CCC governance model and what are the key lessons learnt from these examples for transition governance. Table 2 summarizes our findings.

4.1 Coordinating function

First, we present our findings on the setting up, functioning, and resources of the transition team. Secondly, we look at how the transition team defined their own role and purpose in the process, whether they identified themselves as coordinators and facilitators (intermediary), or whether they saw themselves as executors, primarily responsible for working on the CCC agenda. Thirdly, we were also interested in how they related to the transition arena; whether/how they have established a multi-stakeholder collaboration for the development of the CCC agenda.

The setting up and functions of the transition teams varied widely across Mission Cities. Apart from a few examples where new governance structures were established to develop CCC agenda, a majority of the respondents indicated that a municipal team coordinated their CCC process, in some cases with the support of external consultants. Cities that had already been collaborating on climate change work could take advantage of existing relationships and prior experience in cross-sectoral work. Most respondents understood the role of the transition team as an intermediary, both to engage and support local stakeholder groups in the development of transition plans and to actively coordinate the mission between different departments in the municipality. Making the CCC agenda the primary task for one dedicated person or team was highlighted as a success factor for the CCC work.

Among survey respondents, resource availability was frequently mentioned as an important consideration in the CCC process. Several city representatives specifically noted that participation in the CCC process led to prioritization of resources (time, funding, capacity) for climate-neutrality activities and increased the space (mandate) to experiment with innovative governance practices. At the same time, insufficient municipal resources—primarily human capital, time, and funding constraints—were also cited as a key obstacle. In terms of staffing, a particular challenge has been the loss of institutional knowledge and expertise due to staff turnover, with some municipal officials switching to alternative career paths, often in the private sector, after gaining expertise in climate policy planning. This “brain drain” has hampered efforts to build sustainable climate policy capacity within local governments.

Regarding the setting up of the transition arena, our analysis revealed notable disparities in stakeholder engagement efforts. Not surprisingly, municipalities with well-established climate teams and stakeholder platforms generally demonstrated more advanced progress in this area. In contrast, one City Advisor reflected that municipalities that appeared to lack “strong traditions of climate action and civil society engagement,” struggled more to productively engage stakeholders, for “they are not aware of how and who to engage with.” Vice versa, the involvement of the local government in the transition arena also had its complications; while some interviewees found the municipality's presence crucial, others were critical toward their plans and activities. Reasons for this were amongst others: mistrust toward the government, weak civil society, cultures, and traditions that are not collaborative, participatory or have a limited history with climate action. The lack of societal awareness and commitment to tackle climate change was also reported as an obstacle for onboarding. Ensuring the active participation and engagement of citizens in local climate action plans was a particular challenge, despite the fact that many respondents considered it essential. In addition to difficulties with communication and interaction with citizens, city representatives experienced “people's [limited] willingness to change habits” as a deeper underlying barrier.

Many cities were in the early stages of setting up an onboarding strategy, organizing events (neighborhood tables and dialogue methods, media appearances and CCC launch events) aimed at the different thematic or stakeholder groups. This indicates that although in many cases cross-sectoral collaboration was taken seriously, onboarding activities often were still siloed.

Respondents recognized the CCC as a powerful instrument to assess their unique strengths, with some cities using it as a narrative device, an instrument to contextualize the cities' journey toward climate-neutrality within their historical context, fostering a sense of identity, and showing the significance of their efforts. A clear narrative was considered essential to effectively generate commitments.

In summary, transition teams predominantly comprised municipal staff. Their role was generally understood as intermediary rather than solely executor-focused. Onboarding strategies for transition arenas varied considerably between cities at different stages of development. Those with previous climate collaboration experience reported more advanced progress in stakeholder engagement.

4.2 Co-creating function

This section summarizes how cities enabled the co-creation of the CCC agenda, by focusing on the quadruple helix stakeholder groups: their modes and level of involvement in the transition arena and how their collaboration and co-creation work was enabled and supported. As mentioned, at the time of the data collection, cities' transition teams were still working on strategies to set up/broaden their transition arena, so it is likely too early to draw strong conclusions from their current experiences on their composition. Yet, our first insights were the following.

Most municipalities have already been able to get some level of commitment from external stakeholders such as academia and (publicly owned) utility companies, which in this case meant not only that these organizations had participated in the development of the transition plans, but also that they had signed the CCC's commitment form, indicating their dedication to implementing the plans. In some of the more advanced cities, private companies and citizens also signed the commitment form.

Besides exploring the engagement of local stakeholders, we were also interested in the extent to which they were involved in the process, whether through information, consultation or participation in the development of the plans. Generally, the development of the CCC agenda was mainly a municipality-led process, and other local stakeholders were only occasionally and/or partly involved. Both public and private organizations as well as academic institutions contributed to some extent to the development of the plans but had limited involvement in the writing phase. Non-profit organizations and civil society groups were generally not included in both writing and co-creation processes.

For cities with pre-existing stakeholder platforms and engagement processes, the CCC process served as an enabler, deepening these relationships and formalizing commitments at the project level. Only in the most advanced cases could we find a co-creation process in which stakeholders were closely involved in the development of the CCC agenda, for instance in providing data on emissions, investment planning support, co-creating shared roadmaps, and in the design and execution of climate actions through initiatives like citizen assemblies, advisory boards and steering committees, and local green deal programs. However, in most cases, stakeholder involvement in the CCC meant informing stakeholders about existing plans and collecting feedback.

This also meant that for many municipalities it was not clear how to organize structural collaboration and long-term commitments for implementation. Contact with stakeholders was still mostly ad-hoc and organized on a project-basis, while the CCC commitments would require long-term engagement based on trust and a shared vision. As there has been limited time to build this trust, commitments were not always as ambitious as hoped for.

Although survey data indicated that cooperation with private sector partners happened more often than with civil society partners, the private sector was highlighted in interviews as a challenging stakeholder type to collaborate with. Cities found it difficult to highlight the benefits of joining the Cities Mission to them and why their commitment and time investment would be important.

In conclusion, our findings related to the co-creating function revealed variations in the representation of the quadruple helix groups, with academic institutions and utility companies being the most frequently involved, while private sector and citizen participation remained limited. Most respondents indicated that stakeholder engagement in the development of the CCC agenda was primarily informational or consultative, rather than truly co-creative. Additionally, the operations of transition arenas were mostly project-based and ad-hoc, with only the most advanced cities establishing formalized, structured collaborations.

4.3 Anchoring function

This section discusses the extent to which stakeholders could anchor the plans in their own organizations, thus to what extent they adopted and took ownership of the plans developed in the CCC agenda and committed to their implementation. In practice, this would mean that the plans they undertake would be reflected in the organization's future plans, to which financial and human resources are allocated. Furthermore, we examine the level of institutional involvement of the municipality and the political and leadership support for the transition team and the CCC process.

First, we were interested in who takes ownership of the plans in the CCC agenda and to what extent these actors were committed to implementing them. Our most striking finding is that, in most cases, the local government remained the main or only party that fully embraced the transition plans. As one of the city representatives reflected: “Engagement was not that much of a problem, but the challenge was how far our stakeholders are willing to go in their commitments.” While municipally owned organizations and companies generally felt strong ownership of the plans, other stakeholder groups and citizens in particular were not part of the process and therefore had little or no ownership at all.

The different levels of ownership were also reflected in the challenge of developing investment plans. Many municipalities struggled with building a (realistic) investment portfolio and negotiating for private sector capital investments. While needed, the setting up of innovative financing models such as longer term co-investing structures with external stakeholders in major urban transition projects remained challenging.

Second, we examined the extent to which the CCC process was anchored within the municipalities, specifically the extent and breadth of involvement of different municipal departments in the CCC process and the level of political and leadership support for the transition team.

Regarding broad municipal involvement we found wide variations between cities. City representatives indicated that they made adjustments to their governance due to the CCC work, for instance by setting up new working groups. But while rallying people from different municipal departments around the CCC was indicated to address municipal silos, interdepartmental communication, engagement, and collaboration were also identified as key barriers to the CCC process: “To put it bluntly, [municipal staff from other departments] just say that it's outside their scope of work. That's it.” a City Advisor explained. The role of mid-level managers has emerged as a crucial factor in facilitating cross-departmental coordination and knowledge-sharing.

Difficulties with municipal anchoring might arise from the size of the transition team, as one City Advisor explained: “In some municipalities you already have like 11 people in the climate team [transition team], it's amazing. But then you also see that they can do quite a lot of things by themselves, right, and then in municipalities where you have a very tiny climate team or a just established climate team, they are much more reliant on the other departments to actually contribute.”

Political backing and regular interaction with the administrative and political leaders to be able to pitch ideas provided room to go beyond predefined paths. By some respondents, political support and commitment were considered key to the success of setting up a CCC process. Several city representatives shared their contentment about political endorsement of their work and the Cities Mission in general. They reported receiving a strong mandate, high level support, and permanent commitment from their mayor. “I never thought that politicians are so important until you see what happens when they're not there, because then it's a technocratic mission and it needs to have a heart and soul. It needs to have a spokesperson who has ownership of the mission who is willing to stick his neck out for the project,” said one City Advisor.

Still, concerns were expressed about the sometimes limited understanding by political leaders of the Cities Mission and role of the transition team, as well as on political engagement and ownership of the Mission. City representatives faced with local elections also expressed their concerns about the continuity of their climate plans and actions.

Furthermore, municipalities struggled with national level political support. Climate-neutrality ambitions for 2030 are generally not yet well supported at national level, indicating a gap between local ambitions and national policy frameworks. In more than a few examples, support at the national level for municipal plans was highlighted to even be counterproductive. This could potentially be stemming from conflicting political interests between national governments and the EU. Additionally, some cities would value more explicit commitment by the European Commission, not only in terms of occasional funding but also in relation to necessary regulatory changes. Subsidiarity was raised as an issue: who is responsible for which climate actions and policies? For instance, urban greening is often a local responsibility, while transport and mobility infrastructure planning tends to be determined at higher regional or national government levels, leading to tensions when it comes to cross-sectoral interventions.

In sum, we found that local governments typically maintained primary ownership of plans, with municipally-owned organizations showing stronger commitment than other stakeholders. The level of institutional involvement within municipalities varied considerably among respondents. Political support was identified as crucial but inconsistent across cities, with the engagement of transition arena organizations in implementation remaining a significant challenge for most respondents.

4.4 Governance learning function

As a final function we analyzed—acknowledging that CCC agenda development and particularly its implementation is still at an early stage—to what extent governance learning has taken place in relation to the CCC process. Specifically, we wanted to know whether participation in the Cities Mission had enabled the development of collaboration capabilities or even led to structural organizational changes in municipalities. We also wanted to see whether cooperation and learning transfer between cities had taken place; whether they had been able to exploit the potential that a mission involving 112 cities could offer.

The Cities Mission has aimed to catalyze a shift in how municipalities reevaluate and restructure their governance practices. Our results indicate that the CCC process encouraged experimentation with innovative approaches to fostering climate-neutrality, some of which have already been outlined above, such as the formation of transition teams, internal municipal alignment, and experimenting with novel finance models.

As noted previously, most respondents indicated that working on the CCC agenda positively impacted their governance processes, particularly stakeholder engagement. Where stakeholder involvement was not present initially, working on the CCC agenda helped cities understand that to accelerate their steps to climate neutrality, changes were needed to their way of working. Recognizing the importance of stakeholder involvement in the CCC process, city representatives were interested in learning about successful approaches and communication strategies to engage stakeholders for the long term, and to keep and foster these relationships.

The CCC process has prompted cities to engage in inter-city cooperation (both in formal and less formalized ways), fostering knowledge exchange and collaborative learning. Cities expressed their wish for city-to-city exchange and peer learning as an enabler of their individual CCC progresses, to exchange best practices but also challenges, and to “find allies,” as one seasonal school participant put it. As for formal cooperation, cities sometimes turned to collaboration platforms for structured exchanges, providing opportunities for joint learning and resource sharing, such as city twinning programs. Some national governments, notably Sweden and Spain as front runners, also set up national platforms to support cities participating in the CCC process, enhancing coordination and assistance at a higher level. Informal exchanges occurred outside of structured programs on an ad-hoc basis, driven by a spirit of peer learning and solidarity, for instance sharing CCC components, in some cases also beyond the selected Cities Mission cohort.

In addition to inter-city learning, several other learning mechanisms were highlighted. Prior experience in international climate-neutrality research projects, internal experts and monitoring and control processes were all mentioned as CCC process enablers. Many municipalities have at least some forms of internal evaluation and monitoring frameworks. Yet particularly qualitative impact (for instance, in relation to stakeholder engagement) was difficult to measure.

Moreover, some cities were not used to dealing with failure and uncertainty, whereas the nature of the climate transition requires flexibility being built into their plans, while that may contradict political accountability and task responsibilities. One City Advisor reflected: “What I've noticed is it's very hard for them to test solutions in the CCC and also be ready for failure. […] They would like to be certain that it's going to work. They would like to be certain that the numbers are going to prove that they're right. And I think this is one of the biggest challenges.” City Advisors further noted that the iterative process that is needed to allow for reflection and adjustment is still missing in the overall strategy of some of the cities they supported.

As such, for the governance learning function, respondents reported positive impacts on local governance practices, particularly in stakeholder engagement approaches. Structural organizational changes appeared limited at this early implementation stage. Inter-city cooperation was widely valued, occurring through both formal platforms and informal exchanges. While cities employed various learning mechanisms, many acknowledged ongoing challenges in addressing uncertainty and incorporating systematic reflection into their strategies.

5 Discussion

This study explored the initial actions of cities participating in the 100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission to establish a transition governance model and formulate their transition plans under the CCC agenda. It assessed the implementation of the four key functions to understand how the CCC governance model has been put into practice, and what are the key lessons learned for transition governance. Our study revealed that certain functions were comprehensively grasped and implemented, while others were just partially utilized, combined with other functions, or missing altogether.

In terms of coordination and co-creation, all municipalities had set up a transition team, but only a few had established a transition arena. Although the transition team was appropriately recognized as a coordinator, several city representatives also credited the co-creation function. Thus, rather than establishing a distinct transition arena for this purpose, essentially the transition team formulated the plans and merely consulted local stakeholders. This negatively impacted the anchoring function, as the low level of involvement of local stakeholders in the development of the transition plans has unsurprisingly resulted in exclusive municipal ownership of the CCC agenda. This can be problematic for the implementation of the plans, as a transition agenda developed primarily by a small team within the municipality may be less likely to represent the broader community, raising doubts about its implementation.

A key reason the coordination and co-creation functions were attributed to the transition team alone was that municipalities had a predominantly project-based approach. Since municipalities had to develop the CCC plans within 2 years, they focused on meeting these short-term expectations, despite understanding what long-term mission-oriented thinking and urban transition planning required from a governance perspective. The simplest way to do so was to manage a small team, without wasting valuable time and human resources to engage the quadruple helix stakeholders and facilitate their co-creation. For municipalities whose budgets are heavily dependent on external, project-based funding (Fred and Hall, 2017)—and matching externally set deadlines—it is not surprising that timely delivery of transition plans took precedence over establishing a shared governance framework. Furthermore, with a time horizon of 2030, time pressure is intrinsic to this Cities Mission.

Another reason the transition team may have assumed responsibility for the CCC agenda is that municipalities had limited resources, and little experience in coordinating climate action and engaging local stakeholders. For stakeholder engagement, they tend to focus on low hanging fruit, such as academia and publicly funded organizations. Other stakeholder groups, particularly citizens, were generally not perceived as co-owners of the process. Cities also often struggled to articulate clear motivations and incentives for the participation of private sector stakeholders, and in particular in negotiating for private sector capital investments.

As for the third function, anchoring, increasing ownership within the municipality has received attention as indicated by representatives. Still, the first efforts to break down silos and take a holistic approach to climate action were a strong internal challenge, with the success depending on political support within the municipality. This highlights the tensions between uncertainty or failure management and political accountability on the one hand, and between local and national climate efforts on the other. Many cities have pointed out that this support is also lacking at EU level.

As for the last function, governance learning and building reflexive governance capabilities, evidence is mixed. While some cities leveraged prior experience, experts and monitoring processes, others struggled with embracing experimentation. Integrating reflexivity and iterative learning remains a challenge for many municipal organizations. As a function of the CCC process, the governance learning component appears more isolated than originally envisioned and has not yet permeated through municipal organizations as an integral driver of climate action. Integrating reflexive practices from the outset of the CCC process is demanding, given competing priorities and the fact that many transition arenas are still under development. The vulnerability required for genuine reflexivity within developing stakeholder networks is often not readily available in municipal contexts.

Nevertheless, participation in the CCC process provided a good opportunity to at least raise awareness among municipalities of the importance of involving local stakeholders in the transition and to experiment with initial forms of shared governance and innovative approaches to fostering climate neutrality. The CCC has successfully provided a narrative tool and governance framework that has helped municipalities to better engage local stakeholders in climate work and in aligning, reorganizing, and prioritizing transition efforts within the municipality. The CCC clearly encouraged experimentation with innovative governance practices, including the formation of transition teams, inter-departmental collaboration, and novel finance models. As such, cities displayed evidence of opening up to adaptive governance approaches, emphasizing the importance of flexibility, learning, and iterative processes in managing complex sustainability issues (Folke et al., 2005).

6 Conclusion

Our study examined how the CCC governance model adopts and reinterprets the four main functions of transition management in theory and how cities can apply them in practice, and what it reveals about implementing a theoretical model. First, as an attempt to address the uncertainty around the actual implementation of initiatives stemming from transition management processes (Nevens and Roorda, 2014; Hölscher, 2018; Frantzeskaki et al., 2018; Hölscher and Wittmayer, 2018), the CCC governance model emphasizes early and continuous involvement of different stakeholders in planning and implementation. Thus, it advocates for the active involvement of representatives of stakeholder groups from the outset, i.e., those who should actually implement the concrete projects outlined in the transition plans, rather than the frontrunners. Thereby, the model aims to ensure that all stakeholders participating in the development of the plans feel also ownership of their implementation. Furthermore, this approach promotes wider participation, ensuring that the transition process is more inclusive, collaborative, and sustainable in the long term. In addition, by focusing on the four main functions rather than prescribing specific steps, the CCC aims to create a governance model that can serve as a basis for long-term collaboration of local stakeholders to achieve climate neutrality, while being adaptable to be implemented in a diversity of cities.

However, putting the CCC model into practice has revealed both strengths and challenges. While it serves as a useful strategic tool and helps create a compelling narrative for engagement, balancing stakeholder involvement and the resource constraints faced by local governments remains a significant challenge.

Our findings on anchoring show that many municipalities struggled to build a realistic investment portfolio and secure private sector commitments to capital investments. Indeed, a first assessment of the financial plans of the CCC agendas submitted to the European Commission revealed that many cities could not present concrete and solid financial plans and had only marginally developed private sector co-financing models (Ulpiani et al., 2023). Literature on financing urban climate action highlights how local governments tend to be “operationally unprepared” for dealing with cross-sectoral and multi-scalar challenges, leading to a shift from public sector driven approaches to more decentralized, public-private and fully private funding models for climate action, which comes with trade-offs in terms of accountability, local needs vs. higher scale demands and short-term vs. long term interests (Keenan et al., 2019). Our findings on the CCC process so far indeed confirm that the challenges in building realistic investment portfolios and securing private sector investments are significant.

Another key finding relates to the tension between the ideal of co-creation and the reality of its implementation. While the CCC framework emphasizes multi-stakeholder involvement from the outset, many municipalities grappled with moving beyond consultative participation to genuine co-creation. This issue mirrors broader critiques of mission-oriented governance, where uneven power dynamics within participation processes can hinder truly collaborative decision-making (Kuhlmann and Rip, 2018). However, it is important to recognize that cities did not engage transition practitioners or scholars during this process; hence, the resultant deficiencies may not reflect a flaw in the model but rather a lack of comprehension of it. Cities with less experience in coordinating climate action often prioritize short-term results over establishing inclusive and flexible governance structures, leading to a more centralized approach. In some cases, this centralization has limited the involvement of local stakeholders and undermined the crucial anchoring function needed to ensure long-term commitment and sustained progress.

At the same time, the focus on cases that were not led by transition practitioners or researchers, but by cities themselves, makes this study a unique contribution to the current literature on urban transition management. The results show the extent to which cities are able to adopt transition management models on their own, an understanding that can be important when the mission scales up.

As Kuhlmann and Rip (2018) suggest, reflexivity is crucial for cities to adapt their goals and strategies in response to unexpected societal changes. Consequently,a key next step for cities engaged in the CCC initiative is to integrate reflexive governance elements into their frameworks and revisit their climate agendas regularly to ensure continued alignment with evolving challenges and opportunities. Future research could investigate how such flexible financial structures could be integrated into the transition process and more effectively support cross-sectoral investments in long-term, systemic transitions.

In conclusion, this paper contributes to the broader field of transition studies by introducing a governance model that is adaptable for a diverse range of cities and has been tested in the world's largest urban transition experiment to date. It provides critical insights into the practical application of theoretical models, illustrating how cities learn and adopt new governance frameworks and the challenges encountered during this process. By examining these dynamics, the study offers valuable lessons for transition researchers and practitioners, aiding in the design of more effective models and adoption strategies. Furthermore, it identifies which components of the models are more readily implemented and which present greater difficulties, along with the underlying reasons. This understanding is essential for refining governance frameworks and enhancing the practical application of transition management theories in varied urban contexts.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to confidentiality agreements with the interviewees. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Verbal consent was obtained from the participants and documented or recorded prior to the interviews.

Author contributions

GD: Writing – original draft. HD: Writing – original draft. SH: Writing – original draft. TT: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the European Union (EU) Horizon 2020 NetZeroCities project under grant number 101036519.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude for the task team and consortium members of the NetZeroCities consortium for their contributions to the validation sessions and for their reviews and advice on the research as it developed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bennett, C. J., and Howlett, M. (1992). The lessons of learning: reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sci. 25, 275–294.

Betsill, M., and Bulkeley, H. (2007). Looking back and thinking ahead: a decade of cities and climate change research. Local Environ. 12, 447–456. doi: 10.1080/13549830701659683

Bulkeley, H. (2023). The condition of urban climate experimentation. Sustain. Sci. Prac. Policy 19:2188726. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2023.2188726

Bulkeley, H., and Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: multilevel governance and the 'urban' politics of climate change. Env. Polit. 14, 42–63. doi: 10.1080/0964401042000310178

Cartron, E., Schmidt-Thome, K., Tjokrodikromo, T., Dorst, H., Campbell-Jonhston, K., Saniour, N., et al. (2023). Leading systemic transformation in cities - a capability building approach for systemic transformation in NetZeroCities' Mission and Pilot cities.

Dóci, G., Rohracher, H., and Kordas, O. (2022). Knowledge management in transition management: the ripples of learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 78:103621. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103621

Ehnert, F., Kern, F., Borgström, S., Gorissen, L., and Maschmeyer, S. (2018). Urban sustainability transitions in a context of multi-level governance: a comparison of four European states. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 26, 101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2017.05.002

Ernst, L., de Graaf-Van Dinther, R. E., Peek, G. J., and Loorbach, D. A. (2016). Sustainable urban transformation and sustainability transitions: conceptual framework and case study. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 2988–2999. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.136

European Commission (2024). EU Mission: Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities. Available online at: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe/eu-missions-horizon-europe/climate-neutral-and-smart-cities_en (accessed March 17, 2024).

Folke, C., Hahn, T., and Olsson, P. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 441–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

Frantzeskaki, N. (2022). Bringing transition management to cities: Building skills for transformative urban governance. Sustainability 14:650. doi: 10.3390/su14020650

Frantzeskaki, N., Hölscher, K., and Bach, M. (2018). Co-creating sustainable urban futures. A primer on applying transition management in cities. Future City 11. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69273-9

Frantzeskaki, N., Loorbach, D., and Meadowcroft, J. (2012). Governing transitions to sustainability: transition management as a governance approach towards pursuing sustainability. Intern. J. Sustain. Dev. 15, 19–36. doi: 10.1504/IJSD.2012.044032

Fred, M., and Hall, P. (2017). A projectified public administration how projects in Swedish local governments become instruments for political and managerial concerns. Statsvetenskaplig tidskrift 119, 185–205.

Haddad, C. R., Nakic, V., and Bergek, A. (2022). Transformative innovation policy: a systematic review. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 43, 14–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2022.03.002

Hölscher, K. (2018). “So what? Transition management as a transformative approach to support governance capacities in cities,” in Co-creating Sustainable Urban Futures: A Primer on Applying Transition Management in Cities, 375–396. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69273-9_16

Hölscher, K., and Frantzeskaki, N. (Eds.). (2020). Transformative Climate Governance. A Capacities Perspective to Systematize, Evaluate and Guide Climate Action. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-49040-9

Hölscher, K., and Wittmayer, J. M. (2018). “A german experience: the challenges of mediating ‘Ideal-Type' transition management in Ludwigsburg,” in Co-?creating Sustainable Urban Futures. Future City, Vol. 11, eds. N. Frantzeskaki, K. Hölscher, M. Bach, and F. Avelino (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69273-9_9

Hölscher, K., Wittmayer, J. M., and Avelino, F. (2019). Opening up the transition arena: an analysis of (dis) empowerment of civil society actors in transition management in cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 145, 176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.004

Huovila, A., Siikavirta, H., Rozado, C. A., Rökman, J., Tuominen, P., Paiho, S., et al. (2022). Carbon-neutral cities: critical review of theory and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 341:130912. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130912

Janssen, M. J., Torrens, J., and Wesseling, J. H. (2021). The promises and premises of mission-oriented innovation policy—a reflection and ways forward. Sci. Public Policy 48, 438–444. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scaa072

Keenan, J. M., Chu, E., and Peterson, J. (2019). From funding to financing: perspectives shaping a research agenda for investment in urban climate adaptation. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 11, 297–308. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2019.1565413

Khan, J. (2013). What role for network governance in urban low carbon transitions? J. Clean. Prod. 50, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.045

Klaaßen, L., and Steffen, B. (2023). Meta-analysis on necessary investment shifts to reach net zero pathways in Europe. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 58–66. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01549-5

Kuhlmann, S., and Rip, A. (2018). Next-generation innovation policy and grand challenges. Sci. Public Policy 45, 448–454. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scy011

Kumar, A. (2021). Transition management theory-based policy framework for analyzing environmentally responsible freight transport practices. J. Clean. Prod. 294:126209. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126209

Littek, M., and Wildman, A. (2021). Climate-neutral City Contract Concept. Available online at: https://netzerocities.eu/ (accessed March 18, 2024).

Loorbach, D. (2007). Transition Management. New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development. Utrecht: International Books.

Loorbach, D. (2010). Transition management for sustainable development: a prescriptive. complexity-based governance framework. Governance 23, 161–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01471.x

Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., and Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42, 599–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., and Huffenreuter, R. L. (2024). “Transition management: taking stock from governance experimentation,” in Large Systems Change: An Emerging Field of Transformation and Transitions (Routledge), 48–66.

Moran, D., Kanemoto, K., Jiborn, M., Wood, R., and Többen, J. (2018). Carbon footprints of 13 000 cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 13:064041. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aac72a

Nagorny-Koring, N. C., and Nochta, T. (2018). Managing urban transitions in theory and practice—the case of the pioneer cities and transition cities projects. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.072

NetZeroCities (2022). Transition Team Playbook - Orchestrating a Just Transition to Climate Neutrality. Available online at: https://netzerocities.app/assets/files/Transition_Playbookv0.1.pdf (accessed September 5, 2024).

Nevens, F., Frantzeskaki, N., Gorissen, L., and Loorbach, D. (2013). Urban transition labs: co-creating transformative action for sustainable cities. J. Clean. Prod. 50, 111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.001

Nevens, F., and Roorda, C. (2014). A climate of change: a transition approach for climate neutrality in the city of Ghent (Belgium). Sustain. Cities Soc. 10, 112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2013.06.001

Newig, J., Kochskämper, E., and Challies, E. (2016). Exploring governance learning: How policymakers draw on evidence, experience and intuition in designing participatory flood risk planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 55, 353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.020

Rohracher, H., Coenen, L., and Kordas, O. (2023). Mission incomplete: layered practices of monitoring and evaluation in Swedish transformative innovation policy. Sci. Public Policy 50, 336–349. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scac071

Roorda, C., Wittmayer, J., Henneman, P., van Steenbergen, F., and Frantzeskaki, N. (2014). Transition Management in the Urban Context: Guidance Manual. Rotterdam: Drift. Available online at: www.drift.eur.nl (accessed September 5, 2024).

Rotmans, J., and Loorbach, D. (2009). Complexity and transition management. J. Indus. Ecol. 13, 184–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2009.00116.x

Sabel, C. F., and Zeitlin, J. (Eds.). (2010). Experimentalist Governance in the European Union: Towards a New Architecture. Oxford: OUP.

Sanderson, I. (2002). Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Adm. 80, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00292

Shabb, K., and McCormick, K. (2023). Achieving 100 climate neutral cities in Europe: investigating climate city contracts in Sweden. NPJ Clim. Action 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s44168-023-00035-8

Smedby, N., and Quitzau, M. B. (2016). Municipal governance and sustainability: the role of local governments in promoting transitions. Environ. Policy Governance 26, 323–336. doi: 10.1002/eet.1708

Steffen, B. (2021). A comparative analysis of green financial policy output in OECD countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 16:74031. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac0c43

Swilling, M., and Hajer, M. (2017). Governance of urban transitions: towards sustainable resource efficient urban infrastructures. Environ. Res. Lett. 12:125007. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa7d3a

Ulpiani, G., Rebolledo, E., Vetters, N., Florio, P., and Bertoldi, P. (2023). Funding and financing the zero emissions journey: urban visions from the 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities Mission. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1057/s41599-023-02055-5

Walsh, E., Babakina, O., Pennock, A., Shi, H., Chi, Y., Wang, T., et al. (2006). Quantitative guidelines for urban sustainability. Technol. Soc. 28, 45–61. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.10.008

Wittmayer, J. M., van Steenbergen, F., and Frantzeskaki, N. (2018). “Transition management: guiding principles and applications,” in Co-creating Sustainable Urban Futures: A Primer on Applying Transition Management in Cities, 81–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69273-9_4

Wittmayer, J. M., van Steenbergen, F., Rok, A., and Roorda, C. (2016). Governing sustainability: A dialogue between Local Agenda 21 and transition management. Local Environ. 21, 939–955. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2015.1050658

Appendix A. Details of methodology

Keywords: climate policy, local governance, transition management, urban transitions, stakeholder engagement, transition arena

Citation: Doci G, Dorst H, Hillen S and Tjokrodikromo T (2025) Urban transition governance in practice: exploring how European cities govern local transitions to achieve climate neutrality. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1559356. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1559356

Received: 12 January 2025; Accepted: 06 May 2025;

Published: 17 June 2025.

Edited by:

Joe Ravetz, The University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Andrew Paul Kythreotis, University of Lincoln, United KingdomMarco Dean, University College London, United Kingdom

Kenshi Baba, Tokyo City University, Japan

Copyright © 2025 Doci, Dorst, Hillen and Tjokrodikromo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabriella Doci, Z2FiaS5kb2NpQHRuby5ubA==

Gabriella Doci

Gabriella Doci Hade Dorst

Hade Dorst Stanislas Hillen2

Stanislas Hillen2 Tess Tjokrodikromo

Tess Tjokrodikromo