Abstract

Cities are central to climate action, with the district scale serving as a promising level for implementing climate interventions. However, municipal administrations often face significant barriers in integrating mitigation and adaptation strategies due to siloed departmental structures that limit effective collaboration. This article examines how the City of Munster, Germany, developed a Transition Guideline to systematically integrate climate mitigation and adaptation for existing urban districts through co-creative processes within municipal administration. Using a qualitative mixed-methods approach, a baseline analysis revealed critical organizational barriers: fragmented interdepartmental communication, misaligned data structures, and absence of systematic guidance for transforming existing building stock at the district level. Building on these findings, the City of Munster adapted the Climate Proofing approach – a five-step iterative framework for integrated climate action – into a practical guideline tailored to local governance structures. The resulting Transition Guideline consolidates available climate data, tools, and resources through interactive checklists that guide practitioners through integrated planning cycles while embedding co-creation as a core governance principle. Key findings demonstrate that structured co-creative frameworks have the potential to overcome institutional silos, though persistent gaps remain in district-scale carbon accounting and political engagement. This research provides a replicable methodological approach for municipalities seeking to bridge the gap between ambitious climate targets and implementation capacity at the district scale.

1 Introduction

In 1950, less than one third of the global population resided in urban areas (29.6%), whereas by 2015 the share had already surpassed half of the world’s inhabitants (54.0%). Projections by the United Nations (2015) estimate that this proportion will increase further to 66.4% by 2050. This rapid urbanization, accompanied by the concentration of technology, infrastructure, societal assets, and economic activity in metropolitan areas (Grafakos et al., 2019; Kaklauskas et al., 2024) places cities at the center of climate change dynamics, where they occupy a paradoxical dual role. On the one hand, cities generate approximately 70% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and account for around 75% of the global energy demand (IEA, 2024). On the other hand, they constitute zones of heightened vulnerability to climate-related impacts (Gu, 2019; Pizzorni et al., 2021). Reducing both the urban contribution to climate change and the susceptibility of urban systems to related disruptions requires the integrated implementation of mitigation and adaptation strategies (Cortekar et al., 2016). As Qi and Terton (2022) emphasize, mitigation and adaptation are “two sides of the same coin”: they are two complementary approaches to addressing one of humanity’s greatest challenges.

Climate mitigation, as defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014), encompasses interventions that restrict GHG emissions or reduce their atmospheric concentrations. Mitigation strategies typically include technological and infrastructural investments, renewable energy deployment, and energy efficiency enhancements. Meanwhile, climate adaptation constitutes “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects” within human and/or natural systems (IPCC, 2014). These adjustments aim to increase a city’s resilience against climate change vulnerabilities and impacts.

Both climate mitigation and adaptation actions prove most effective when implemented locally, where specific climate change manifestations can be directly addressed through contextually appropriate responses (Kern and Mol, 2013; Ürge-Vorsatz et al., 2018). Globally, countries recognized the importance of a place-based approach and have incorporated a city-focused commitment into a nationally established agenda (Espey et al., 2023; Aboagye and Sharifi, 2024). This is evidenced by the increase in the number of municipalities establishing GHG reduction targets and implementing adaptation measures, particularly in economically strong regions (Grafakos et al., 2020). As reported by the Global Covenant of Mayors (2024), 13,558 municipal and local governments across 147 countries – collectively representing 1.2 billion residents – have formally committed to addressing GHG emissions.

Growing attention to urban climate action has sparked considerable interest in examining districts as key sites for climate interventions within cities. Several scholars regard the district level itself as a promising scale for climate interventions, given their strategic position as a bridge between citywide policies and household-level actions while capitalizing on established community networks and local relationships (Grazieschi et al., 2020; Joshi et al., 2022). From the perspective of urban planning, districts function as essential organizational units that create favorable conditions for developing, testing, and evaluating various climate-related projects (Joshi et al., 2024). Climate initiatives at the district scale encompass both emission reduction strategies – such as energy-efficient construction and clean energy system implementation – and resilience-building measures, including stormwater management and urban cooling through vegetation expansion (Joshi et al., 2024).

Despite this progress, initiatives for mitigation and adaptation – at city and district levels – are most often conceptualized and implemented as distinct domains (Mendizabal et al., 2018). Consequently, different stakeholders and actors operate in each domain with limited communication, making it difficult to assess synergies and trade-offs during planning and implementation. This siloed approach can lead to stranded assets, missed opportunities for synergies, duplicated efforts, higher overall project costs, and the misallocation of limited staffing capacities (Qi and Terton, 2022). Addressing mitigation and adaptation in isolation is therefore inefficient and wastes valuable resources.

To overcome institutional barriers and dismantle sectoral silos, emerging approaches emphasize employing diverse methods to engage stakeholders in co-creation processes (Frantzeskaki et al., 2025), seeking to shift from a static, state-driven, and spatially biased approach to one that is dynamic, people-centered, and integrative.

The concept of co-creation originated in psychology and sociology and has since been adopted in urban planning domains, where the need to reach, communicate and work with different stakeholders is paramount. Co-creation is widely recognized as “any act of collective creativity shared by two or more individuals” (Avila-Garzon and Bacca-Acosta, 2024). The aim is to ensure that ideas and solutions are implemented in their original context and selected through an informed, democratic process.

In urban contexts, co-creation involves collaborative processes in which stakeholders – including local communities, government bodies, architects, and planners – work together to design and implement projects. It is often argued that co-creation bridges gaps between these actors, enabling a more comprehensive consideration of diverse ideas, needs and concerns (Leino and Puumala, 2021). This approach empowers participants by ensuring that their perspectives are incorporated into integrated planning processes. Furthermore, it promotes innovation by combining knowledge from previously separate sectors, producing solutions that address multiple climate challenges while generating high local acceptance and ownership. In summary, such co-creation processes overcome the inefficiencies of sectoral isolation and lead to more sustainable outcomes supported by a broader range of urban stakeholders, maximizing synergies (Angelidou et al., 2021). By doing so, co-creation represents an alternative management model with potential advantages over conventional approaches that rely primarily on expert input (Hassan et al., 2011). However, to realize the potential of co-creation, structured frameworks and careful implementation are essential. Effective co-creation depends on establishing clear parameters for stakeholder engagement, including well-defined roles, decision-making authority, and participation timelines (Mahmoud et al., 2021).

In response to these challenges, this article demonstrates how the City of Munster, Germany, developed a structured guideline that enables municipal stakeholders to address climate mitigation and adaptation in an integrated manner through collaborative co-creation processes. This approach specifically targets the institutional barriers within municipal administration that perpetuate siloed approaches to climate action.

The case study is embedded within the UP2030 project, a strategic research and development initiative funded by the Horizon Europe Framework program. UP2030 supports cities in driving the socio-technical transitions necessary to meet ambitious climate targets through systematic co-creation (Kapetas et al., 2023). The project facilitates strategic partnerships between pilot cities and specialized Tool Providers, allowing the customization of existing tools and methodologies to address specific urban climate requirements. In Munster, the developed guideline builds upon the Climate Proofing approach developed by Buro Happold (BH) and complementary research into Munster’s use and availability of carbon emission data by the University of Cambridge (UCAM).

The primary contribution of this article is to show how the developed guideline can strengthen co-creation processes within municipal administration, overcoming institutional silos and enabling integrated climate action. By detailing both the methodological framework of Climate Proofing, as well as its practical application and extension for the development of the guideline in Munster, this research provides a replicable approach for fostering holistic urban climate strategies.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: After outlining Munster’s baseline conditions in Section 2, Section 3 details the methodological foundations of Climate Proofing. Building on this, Section 4 illustrates how this approach was adapted in Munster to develop the guideline for municipal administration. Section 5 then synthesizes key lessons from the development process, before Section 6 discusses prospects for scaling the guideline beyond the local context.

2 Munster case study: from baseline analysis to visioning solutions

The City of Munster faces complex challenges in climate mitigation and adaptation, with dense inner-city districts requiring particular attention. These urban spaces combine diverse uses and stakeholders within limited areas, creating both opportunities and specific problems. The historic city center exemplifies these challenges. It exhibits potential for climate mitigation, including underutilized rooftops for photovoltaic installations, considerable opportunities for energy-efficient retrofits, and underdeveloped sustainable heating infrastructure. Simultaneously, the district faces significant adaptation hurdles from urban heat island effects caused by extensive surface sealing and insufficient green spaces – conditions that also exacerbate flooding vulnerabilities.

Against this background, Munster has established the ambitious goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2030. The city advances this agenda through participation in the mission 100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030 of the European Union (European Commission, 2025). As part of this mission, Munster has developed a comprehensive Climate City Contract encompassing commitments from both municipal administration and civil society, alongside a detailed investment and action plan.

Implementation efforts are structured across seven key strategic domains: (1) Energy Production, (2) Construction and Renovation, (3) Mobility, (4) Climate Budgeting, (5) Education and Nutrition, (6) Economy and Science, and (7) Climate Adaptation. The dedicated Climate Staff Unit orchestrates these initiatives. Its placement within the staff unit structure ensures effective integration of climate objectives across all municipal departments, as staff units support administrative departments without being embedded in day-to-day operational processes.

An important element within Munster’s pursuit of climate neutrality is the city’s emphasis on the district level as a key focus for municipal climate action, with an intention to strengthen this approach in the future. This represents a cross-departmental principle closely linked to the city’s broader mission efforts. In the strategic domain of Construction and Renovation, for example, the traditional approach of considering individual buildings gains significant potential when supplemented by a district perspective. This broader view enables the identification of efficiency opportunities and action strategies within the context of integrated urban development and energy planning, thereby increasing the overall impact of GHG reduction measures.

2.1 Baseline analysis methods

Despite Munster having detailed knowledge of the specific challenges in climate mitigation and adaptation, there are still considerable implementation deficits. In view of the ambitious climate neutrality target of 2030 and the associated need to accelerate efforts in climate mitigation and adaptation, a systematic analysis of Munster’s urban climate action was conducted. This analysis aimed to determine baseline conditions within the municipal administration, develop a comprehensive understanding of individual departments’ and employees’ needs, and identify barriers to implementing climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. The analysis systematically examined three core elements of Munster’s urban climate action: (1) municipal staff perspectives – exploring employees’ understanding, knowledge, and experiences with current climate efforts; (2) the governance landscape – including available strategies, projects, and institutional frameworks; and (3) operational capacity – encompassing relevant available data. Through a mixed-methods approach, the baseline analysis developed comprehensive insights across all three dimensions.

The investigation commenced with a survey to assess the knowledge and perspectives of municipal staff working in climate-related fields (including the Climate Staff Uni, the Office for Green Spaces, Environment and Sustainability, the Office for Mobility and Civil Engineering and the Office for Housing and Neighborhood Development) on local climate mitigation and adaptation. The survey combined closed questions with multiple-choice responses and open questions to capture qualitative insights. The questionnaire comprised 15 questions covering organizational affiliation, prior project participation, understanding of Munster’s climate mitigation and adaptation concepts, methods for GHG accounting, and knowledge of municipal climate goals. Pre-defined response categories were used for the participant classification questions. Open-ended questions, however, enabled a more detailed exploration of participants’ conceptual understanding and their perceived roles in climate action. Data collection was conducted anonymously with informed consent to ensure confidentiality.

Following the survey, a structured workshop was held in May 2023 to systematically evaluate the current governance landscape and operational capacity for climate mitigation and adaptation. Participants again included the Climate Staff Unit and relevant administrative personnel working in climate-related fields. The workshop employed a two-stage matrix mapping approach for comprehensive analysis. In the first stage, participants collaboratively positioned existing strategies, instruments, projects, regulations and data sources (matrix columns) across Munster’s seven key strategic climate action domains (matrix rows). This systematic mapping exercise generated a comprehensive overview of the prevailing governance landscape, identifying potential overlaps or gaps in the current approach. In the second stage, participants analyzed each mapped element in detail by systematically assigning drivers, barriers, needs and relevant actors. This enabled a multi-dimensional assessment of the governance landscape, revealing not only the existing initiatives, but also the underlying factors that facilitate or impede their implementation and strategic gaps.

Additionally, a semi-structured group interview with two members of Munster’s Climate Staff Unit was conducted by UCAM. This was to complement the survey and workshop findings with in-depth insights into the city’s capacity to use carbon emission data within the decision-making process. This interview focused specifically on how emission data informs political decision-making.

The original research design envisioned engaging city councilors to examine this question. However, concerns expressed by the administration regarding political sensitivities necessitated a revised approach. Consequently, access was only granted to practitioners within the Climate Staff Unit as an alternative pathway for investigation.

The interview protocol addressed four main thematic areas: (1) the structural framework of carbon neutrality decision-making within Munster City Council, examining the entire process from initiation to implementation; (2) the role of data in decision-making, with a particular focus on the use of municipal carbon emission data; (3) the availability and use of tools and resources to support various types of climate-related decisions; and (4) the participants’ views on the ideal decision-making process, including possible improvements to information flow and data accessibility.

The semi-structured format employed open-ended questions to facilitate detailed exploration of decision-making processes, allowing participants to share experiential insights and contextual knowledge.

The interview lasted for 54 min and was conducted via Microsoft Teams. It was audio-recorded and transcribed for subsequent analysis. The resulting data were used to develop carbon emission data flow maps, which visualize information pathways within municipal governance structures.

2.2 Baseline analysis results

The mixed-methods analysis revealed multiple interconnected organizational barriers to the effective implementation of integrated climate mitigation and adaptation measures within Munster’s climate action efforts.

Heterogeneous responses regarding the understanding of municipal climate goals and a widespread lack of knowledge about GHG emission inventories, as revealed by the survey, indicate major gaps in communication and information flow. This suggests that essential climate data and strategies are not systematically disseminated to all relevant stakeholders. Concerning strategic clarity, varying definitions of climate-neutral city revealed opportunities to strengthen a unified strategic vision and common understanding among participants. Differing interpretations may contribute to coordination challenges and suboptimal resource allocation. Particularly notable was feedback concerning implementation speed, which suggested that administrative processes require streamlining to better support timely implementation of climate measures.

The organizational barriers that were already identified in the survey were also supported by the results of the workshop format. It revealed significant interdepartmental communication deficiencies, with siloed working practices hindering knowledge exchange regarding interconnected strategies and available data resources. Despite various climate initiatives existing within individual departments these efforts lacked cohesion and visibility across the broader administration. Several climate action related projects are pursued in parallel, leading to a lack of consistency and links between them. Participants consistently identified co-creation among all relevant departments as the essential solution for successful implementation and long-term sustainability of climate measures, emphasizing that collaborative approaches are not optional but fundamental to overcoming these systemic barriers.

Beyond these organizational barriers, the workshop also identified a significant thematic gap within Munster’s climate governance landscape. While Munster has developed a comprehensive guideline for the integrated consideration of climate mitigation and adaptation in land-use planning, this guidance framework exclusively focuses on new construction projects and district development. This narrow scope represents a significant strategic gap, as it overlooks the substantial climate potential within the building stock and existing urban infrastructure, which faces various challenges, as described above. The absence of systematic climate guidance for building stock and existing urban infrastructures means that a critical opportunity for achieving the city’s 2030 climate neutrality target remains largely untapped.

The interview provided important insights, particularly with regard to data availability, flow and usage within the administration. Every year, the Climate Staff Unit produces an emission inventory for the city area of Munster. This includes the emissions produced from stationary energy sources, such as households, businesses and industry, alongside the agricultural sector, land use change and forestry, and transportation. Whilst the transportation data is centered upon the downscaling of national emission data, the stationary energy data is taken from the local utility company, who have the energy use data for all customers, and therefore all buildings within the city. By applying emission factors to the energy use data, the Climate Staff Unit can calculate the carbon emissions from the above stationary energy consumers.

However, this is done at a sectoral level, not per-household or building level, with the local utility company sharing overall totals, not building specific energy use data with the city. This is owing to data protection concerns, which whilst understandable, prevents granular assessment of building emissions within districts. To structure the city’s carbon accounting, the practitioners use BISKO, a territorial-based standard “that aims to harmonize different approaches and achieve comparability between carbon accounting of German municipalities” (Lenk et al., 2021). According to Lenk et al:

“The BISKO standard is defined as a final energy-based territorial carbon accounting. Within a territory, all accruing consumption on the level of final energy is considered and assigned to various sectors, for example, housing or traffic. The carbon emissions are calculated through specific emission factors.”

This standard accounts for carbon emissions from sources located within the city boundary (Scope 1) and emissions occurring as a consequence of the use of grid-supplied electricity, heat, steam and/or cooling within the city boundary (Scope 2) (Lenk et al., 2021). As is demonstrated above, a key element of BISKO is the ability to compare different cities, owing to the centralization of energy systems within Germany. Whilst this is of benefit to the City of Munster, via the ability to contextualize their mitigation efforts, broader national-level standardization across cities has the potential to limit the ability of Munster, and other cities, to devise locally specific emission reduction actions, with actions such as reducing the use of oil fueled domestic heating systems and the ability to set local emission taxes being identified as actions constrained by this operational context.

Beyond national legislation, there are also practical constraints limiting carbon accounting, such as financial, time and capacity limitations, as well as the influence of the city’s political context. As was cited in the interview process, previously decarbonization was the most pressing issue within the municipality, however in the long shadows cast by Covid-19 and the inflationary economic impacts of the war in Ukraine, the reduction of carbon emissions must be factored into actions designed to limit the financial impacts on Munster’s 320,000 residents.

This has altered the nature of Munster’s carbon reporting. Previously, the carbon emission inventory would solely focus on the reporting of emissions within the city, however, as of 2024, it now combines emission data with the associated costs of carbon reduction. These reductions, identified through a series of concept studies and action plans, predominantly center around building retrofit, in particular the upgrading of heating systems vis-a-vis the transition from oil to heat pumps, and enhanced household insulation.

The overriding insight derived from the interview process revolves around the role of emission data in decision making. For, despite the good intentions underpinning these actions, and the a priori research conducted looking into their potential impacts, there is little evidence of the city’s authorities possessing the capacity or desire to advance the scope of Munster’s current carbon accounting practice, with the interviewees identifying a lack of data at the district level and an inability to estimate lifestyle carbon emissions of the city’s residents as key barriers to such enhancement.

Although Munster is pursuing a district-level approach to mitigating climate change, its current accounting practices and the resulting data are misaligned with conducting decarbonization at this scale. In short, the city’s contemporary understanding of its emissions is centered upon city-wide accounting and relies upon concept studies, not contextually specific carbon accounting.

The results obtained from the baseline analysis and the associated implications are listed in Table 1, grouped by topic.

Table 1

| Topic | Key findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Communication and strategic clarity |

|

|

| Interdepartmental coordination |

|

|

| Strategic scope of governance |

|

|

| Data availability and usage |

|

|

| Carbon accounting standard (bisko) |

|

|

| Resource and political constraints |

|

|

| Evolution of reporting |

|

|

| Data gaps and misalignment |

|

|

Baseline analysis key findings and implications.

2.3 Co-creation of a vision to overcome identified barriers

Based on the systematic analysis, the research process transitioned from diagnosis to solution development through a collaborative visioning approach. For this purpose a workshop was conducted to design blueprints to address identified organizational barriers and thematic gaps previously identified. Since the findings indicated that Munster’s climate action challenges primarily stemmed from internal administrative organization and processes, participation in the following workshop was limited to members of the Climate Staff Unit, which is primarily responsible for orchestrating activities in this domain. The workshop, held in March 2024, employed a strategic two-stage approach. Initially, participants reviewed the analysis results and identified any missing aspects. The Climate Staff Unit also clarified its own responsibilities within the city’s climate governance landscape. Subsequently, participants developed a shared vision outlining solutions to these challenges.

The key outcome was the vision of an internal administrative Guideline for Climate-Friendly Transition of Existing Urban Districts (hereinafter referred to as Transition Guideline). The term climate-friendly in this context reflects that climate mitigation and adaptation should be considered as integrated and synergistic approaches when transforming existing urban areas. By focusing on existing urban areas, the guideline addresses the previously identified thematic gap, extending beyond new construction projects to encompass building stock and existing urban infrastructure.

The Transition Guideline was visioned as a high-level strategic framework for future-proof district-scale development in Muenster rather than a project-specific manual. It should not be tailored to a single specific district but provide action-guiding orientation for all municipal staff implementing district-level measures in accordance with the city’s district-level approach. The Transition Guideline aims to empower municipal staff to approach the dimensions of climate mitigation and climate adaptation in an integrated manner, making the most of existing expertise, resources, and collaborative potential within the city administration. Through co-creation and cross-departmental collaboration, the guideline seeks to foster a holistic perspective on district-level climate action. It is intended to be consulted whenever district-level projects are initiated, or structural interventions are planned. This design ensures that the framework’s methodology remains deliberately flexible, thereby maintaining long-term applicability and supporting continuous transformation processes at the district scale.

In summary, the Transition Guideline aims to (1) streamline processes for integrating climate mitigation and adaptation into building stock, and existing urban infrastructures on a district level; (2) facilitate systematic co-creation and knowledge exchange between all relevant departments to overcome siloed working practices; (3) and systematically organize and consolidate existing climate-related knowledge, data, implementation examples, tools, and processes to enhance evidence-based decision-making through improved data governance.

The target group was defined as urban practitioners within the municipal administration and has been intentionally kept broad to ensure that mitigation and adaptation are integrated across various areas of Munster’s administration.

To develop the envisioned Transition Guideline, Munster’s Climate Staff Unit collaborated with BH as a Tool Provider, adopting their Climate Proofing approach. It was applied to strengthen synergies between mitigation and adaptation in implementing Munster’s urban climate action initiatives – from early conceptualization to operation.

It is important to note that institutional resistance from municipal administration regarding councilor involvement substantially limited UCAM’s engagement in the case study. Although UCAM’s original research design envisioned analyzing the role of emission data in political decision-making, concerns about potential political implications surrounding current carbon accounting limitations precluded access to relevant decision-makers. This resulted in UCAM’s repositioning to a supporting capacity, contributing only insights from their stakeholder interviews to inform the Transition Guideline development.

3 Methodological framework underlying the development of Munster’s Transition Guideline

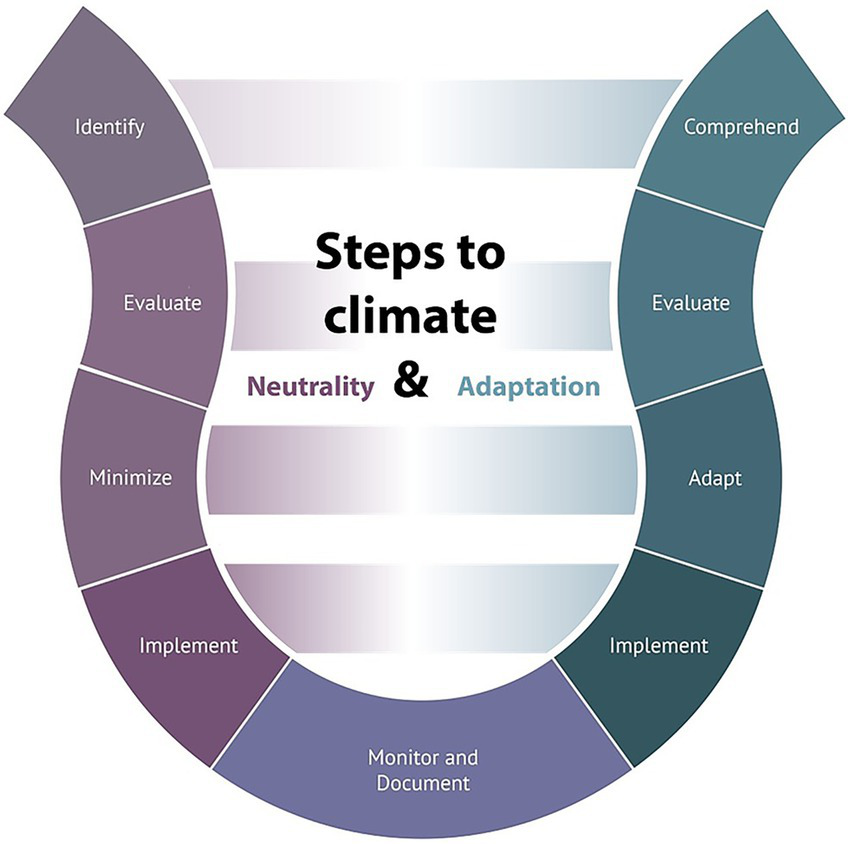

As highlighted above, developing integrated strategies that synergistically combine climate mitigation and adaptation approaches is crucial for cities to achieve comprehensive and sustainable climate targets. The Climate Proofing approach responds to this need by proposing a structured five step process for urban climate action initiatives, providing methods for the planning, design, delivery, and operation of climate-neutral and -adapted systems. At its core, the method consists of five iterative steps. As illustrated in Figure 1, the five process steps are structured to be read in parallel from top to bottom, reflecting the concurrent development of climate neutrality and adaptation strategies across each phase. They are applied in parallel but complementary ways to address mitigation and adaptation objectives. The process moves from city and vision assessment (Identify/Comprehend), to creating and implementing action plans (Evaluate, Minimize/Adapt, and Implement), and then to evaluating results to reassess objectives and priorities over the long term and inform future programs (Monitor and Document).

Figure 1

Climate proofing for integrating climate mitigation and adaptation (own illustration).

The steps for both adaptation and mitigation follow a similar structure, with minor variations targeting different dimensions of climate action. Importantly, the methodology emphasizes the early integration of climate considerations into project development, helping to overcome institutional silos and foster collaboration across disciplines and departments. Furthermore, it enables practitioners to integrate both perspectives into a coherent planning cycle that encourages continuous learning and adjustment. Monitoring and documentation of outcomes can feed directly into subsequent planning and decision-making iterations. The method targets a broad range of stakeholders in urban and regional development, including public authorities at national, regional, and local levels, as well as private sector professionals such as urban planners, architects, and engineers.

The Climate Proofing approach was developed in the early stages of a large-scale district development project in Berlin (Blankenburger Süden), which provides more than 6,000 new residential units for the city’s growing population. As part of a study on climate impacts and adaptation options for the area, both climate adaptation and mitigation aspects were considered synergistically (microclimate simulations and GHG accounting were used, among other things). This approach reflects the aim of Berlin’s Climate Urban Development Plan (StEP Klima) and the Berlin Energy Transition Act, which mandates the expedited attainment of climate neutrality. Within the framework of StEP Klima, integrated approaches to both climate change mitigation and adaptation are addressed and partly interlinked. The conceptualization and implementation of Climate Proofing operationalizes this policy vision by translating it into a pragmatic, actionable instrument for urban planning and development processes.

Climate Proofing was developed from this project using a mixed-methods approach, including a comprehensive literature review, as well as the targeted involvement of municipal stakeholders.

The literature review aimed to identify current trends in climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, as well as how cities engage with these themes, to better understand practical needs and potential implementation challenges. It examined governance strategies, city-wide concepts and studies as well as climate-relevant legal frameworks, guidelines and resolutions from 2010 to 2024, ensuring source relevance by focusing on publications applicable to district- and city-level interventions. Additionally, the research integrated the most recent European legislation to ensure alignment with current policy frameworks.

In parallel, a close collaboration with the senate and a co-creative development process with different stakeholders were pursued. Especially the integration of different departments within the senate was a key element to ensure alignment and acceptance of the outcomes and results throughout the process. Additionally, exchanges with stakeholders in the fields of rainwater management, energetic district renovation and the municipal energy company (Berliner Stadtwerke) were held to continuously inform as well as review outcomes and exchange on planned actions throughout the development process. In regular working groups, attended by representatives of different units, results and outcomes were presented and actions discussed. The proposed actions for climate mitigation and adaptation were then translated into spatial recommendations, forming concepts for the development, which would set the basis for climate neutral and resilient district development (Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung, Bauen und Wohnen, 2025). Within the Climate Proofing approach (see Figure 1) this translation of developed actions into concrete spatial interventions is referred to as Implement.

This approach enabled the creation of a robust and context-sensitive framework that supports climate-friendly urban development. Within each step (see Figure 1), Climate Proofing outlines a detailed yet flexible methodology for achieving its objectives in accordance with the specific context of each project. The approach underlying each step is described in more detail below.

Climate Proofing starts with the identification (mitigation approach) or comprehension (adaptation approach) of the context: relevant framework conditions, specifically overarching climate action goals and ambitions, are compiled to derive specific objectives for the considered scale of the individual project. This includes understanding set climate mitigation goals, such as balancing GHG emissions until a target year, promoting resource conservation and adaptation ambitions with regard to expected future climate impacts. The identified framework conditions for both climate mitigation and adaptation are aligned as part of the first step, aiming to recognize synergies and potential areas of conflicts between the two ambitions resulting from overarching frameworks with relevance to project development. The ambitions are informed by international, federal, state, and municipal directives, policies and action plans.

In the second step, specific fields of action are defined and prioritized. This involves evaluating areas where significant GHG reductions and resource conservation can be achieved. Simultaneously, this includes the assessment of climate risks, for example through hotspot analyses. This step involves aligning the identified and prioritized fields of action in the areas of climate mitigation and adaptation. This lays the foundation for exploiting synergies between these areas in targeted interventions later on. An exemplary field of action is the reduction of operational carbon related to the built-up areas and urban structures in a project. With regards to climate risks in urban areas, the reduction of heat stress and the management of stormwater are examples for fields of actions. Evaluating the named fields of action shows that while no conflict in ambitions and priorities arises between the two fields of action, spatial interventions in the fields can later influence each other, requiring an integrated development process.

The third step involves developing specific strategies within the identified fields of action to advance both climate mitigation and adaptation. Depending on their focus, actions related to mitigation are classified under Minimize, while those addressing adaptation fall under Adapt. This distinction ensures that each intervention is aligned with its intended environmental objective and contributes effectively to a comprehensive climate-proofing approach. For this, the prioritized fields of action are used as a basis to develop strategies. As part of the integrated development approach, each developed strategy is tested against and analyzed with regards to its impacts on both climate mitigation and adaptation in the project. Aiming to identify synergies of the targeted implementation strategies enhances the effectiveness and long-term impact in the project. Urban green infrastructure demonstrates how climate adaptation and mitigation strategies can work synergistically. By integrating natural and semi-natural systems into urban environments, cities can simultaneously reduce operational GHG emissions while addressing critical climate risks. These green systems provide essential adaptation benefits by mitigating urban heat island effects and managing stormwater runoff during extreme weather events. At the same time, they contribute to climate mitigation through reduced energy demands for cooling buildings and infrastructure.

In the fourth step, the developed measures are implemented at regional, city-wide, or district levels. This involves spatial allocation for implementation and securing financial resources through funding programs at various levels. The exemplary strategy described in the previous process step, integrating natural and semi-natural systems, is detailed and allocated spatially here: hotspots for heat stress, identified in process step two, are selected and the feasibility for selected intervention measures is analyzed. Following the integrated approach, intervention sites are chosen to simultaneously provide building shading, passively reducing cooling energy requirements. By selecting locations used as circulation routes, indirect effects can further be exploited: Through an increase in outdoor comfort, sustainable mobility including cycling and walking is promoted in urban areas. Along the simultaneous consideration of the ambitions for climate mitigation and adaptation, measures and their implementations are developed in a way that contributes to both climate neutrality and resilience.

The final phase focuses on monitoring, documenting and sustaining the implemented measures to ensure their long-term effectiveness. This includes regularly reviewing the effectiveness of climate mitigation measures through data collection and analysis of GHG emissions as well as energy consumption and ensuring continuous integration and funding of these measures in development plans. The effectiveness of climate adaptation measures is also regularly reviewed through data collection and analysis of temperature changes, precipitation patterns, and other relevant indicators, with a focus on previously identified hotspots. Defining indicators for monitoring that specifically reflect the integrated impacts of the developed measures allows for the quantification of the integrated long-term effects of the implemented measures.

In summary, the Climate Proofing approach offers a structured yet adaptable framework for integrating mitigation and adaptation goals throughout the entire urban development process. By guiding practitioners from the initial assessment of baseline conditions to the monitoring and documentation of implemented measures, it supports comprehensive climate-friendly planning and decision-making. Its iterative nature ensures that strategies remain responsive to new data, evolving policy frameworks, and emerging urban challenges, thereby supporting the long-term pursuit of climate-neutral and resilient cities.

4 Developing Munster’s Transition Guideline

The adaptation of theoretical methods to local urban conditions marks a pivotal phase in socio-technical transformation processes. Following the baseline analysis and collaborative visioning approach (see Section 2), the research transitioned into its action phase, where BH leveraged their Climate Proofing and UCAM provided insight into the current use of carbon emission data within Munster, to develop an actionable Transition Guideline for the city. This section explains how BH and UCAM – based on their existing methods and insights – developed the Transition Guideline and how it was customized to Munster’s specific needs.

To situate the subsequent methodological discussion, it is helpful to briefly outline the conceptual foundation of the Transition Guideline. It conceptualizes the district as the key scale for implementing climate-friendly urban transformation. Districts are understood as “manageable units with specific needs” in which “needs can be identified and assessed, and measures can be developed and implemented in a targeted and effective manner.” Building on Munster’s existing citywide concepts – such as the Climate City Contract – the guideline translates these overarching ambitions into actionable processes at the district level through the application of the Climate Proofing methodology. In other words: by aligning climate proofing with Munster’s existing strategies, planning frameworks and data sources, the Transition Guideline enables its users to adapt their respective projects to the specific local context of the district, while taking an integrated approach to climate mitigation and climate adaptation.

In this context, co-creation was identified (s. Section 2b) as a key mechanism for fostering the integrated consideration of climate mitigation and adaptation by strengthening communication and collaboration across municipal departments. It was seen as an important approach for overcoming deficiencies in interdepartmental communication caused by siloed working practices. This emphasizes the need for collaborative processes from the very beginning. Consequently, it was essential that co-creation was not only embedded in the Transition Guideline itself, but that collaboration played a central role during its development. This collaborative foundation was established through numerous exchanges and discussion rounds between Munsters Climate Staff Unit and various departments working in climate related fields.

To further emphasize the importance of co-creation it was introduced as a key lever within the Climate Proofing approach to enhance the integrated consideration of mitigation and adaptation. While co-creation had already played a significant role in the development of the Climate Proofing approach, it was not yet explicitly recognized as a distinct component supporting integrated climate action. Its inclusion in the current approach highlights the value of collaborative processes in aligning mitigation and adaptation objectives and fostering more inclusive and context-sensitive climate action.

Within the Climate Proofing process in the Munster context, co-creation is conceived as an inherently iterative rather than linear approach. Each of the five methodological steps is revisited and refined in light of emerging insights and stakeholder feedback, allowing for continuous learning and adaptation. This iterative logic ensures that strategies remain responsive to local dynamics and evolving climatic and social conditions, while simultaneously fostering dialog and mutual understanding across municipal departments. Through this ongoing process of reflection and adjustment, co-creation creates the conditions for overcoming fragmented administrative structures by strengthening interdepartmental communication, joint planning and collective reflection. Collaborative discussions, synchronized timelines, and flexible adaptation of planning outcomes thus facilitate the development of integrated strategies that bridge institutional silos and enhance coordination across departments. Building on this procedural foundation, co-creation in the Climate Proofing process also entails a gradual transformation of governance structures and decision-making routines. For its impact to be sustained, collaborative competencies and practices need to become embedded within the institutional culture of public administration. In Munster, this principle has been reflected in the early and continuous engagement of actors across departments and sectors. In this sense, co-creation extends beyond a methodological tool to function as an evolving governance paradigm that seeks to institutionalize integrated climate action across administrative boundaries.

To develop the envisioned Transition Guideline from the Climate Proofing approach expanded by the aspect of co-creation, an Organizational Tracker in the form of a comprehensive Excel worksheet was first developed. This tracker structured and consolidated available data, tools, project outcomes, and existing guidelines related to climate action and co-creation in the City of Munster. The collected resources were then systematically mapped to the individual process steps of Climate Proofing, based on their relevance and applicability to planning and implementation processes within the city.

In close collaboration with representatives of the city’s Climate Staff Unit detailed needs and demands for the later content and implementation of the Transition Guideline were collected to develop an initial structure of the document. The baseline analysis revealed the lack of a shared understanding and vision for climate mitigation and adaptation in urban development amongst the administrational staff. Formulating a shared vision for the integration of climate mitigation and adaptation in urban development processes in Munster and its implementation on the district level was hence crucial for the development of the Transition Guideline. For this, the following structure, divided into four parts was defined: Section 1 is an introduction to district development in the City of Munster and the formulated shared vision for climate friendly district development. Section 2 presents the methodological background of Climate Proofing and gives the theoretical background to the method. Section 3 is a step-by-step guideline for implementing Climate Proofing in Munster and is aimed at operationalizing the allocated data and other resources for climate action and co-creation in the city. Section 4 includes profiles on the most relevant resources including guidelines and policies on climate action available in the City of Munster.

Section 3 forms the focal part of the Transition Guideline and its later application, as it is action focused. Here, checklists with guiding questions lead the user through the individual Climate Proofing steps, with links to Munster internal and external resources provided, enabling the user access through hyperlinks directly from within the document. For each step of the Climate Proofing, a separate checklist was developed, covering the topics of climate mitigation, adaptation and co-creation.

The guiding questions were designed to balance local specificity with broader applicability. They address Munster’s key strategic domains of climate action and are accompanied by links to locally relevant data wherever possible, while remaining adaptable to diverse project types and implementation scenarios. By prompting users to reflect on integrated climate mitigation and adaptation actions, they encourage a more effective use of existing municipal resources while simultaneously guiding the development of new ideas for strategies and interventions within individual projects. Beyond their functional role, the guiding questions deliberately anchor the Climate Proofing process at the district scale. They require the collection and evaluation of district-specific information – such as local land-use regulations, energy consumption patterns, social and demographic structures, mobility behavior, climatic risks, and local stakeholder networks. Drawing on citywide datasets and planning frameworks, the Transition Guideline enables municipal staff to translate these into their respective district contexts, fostering a localized understanding of climate potentials. In this sense, the guiding questions serve as an operative link between Munster’s city-level strategies and the concrete, action-oriented processes within individual districts. They direct attention to interconnected groups of buildings and surrounding infrastructure – streets, sidewalks, public spaces, and energy networks – that share similar spatial and functional characteristics and thus constitute meaningful units for integrated climate mitigation and adaptation planning.

An exemplary question in the development (steps Minimize and Adapt) of climate mitigation measures is “What is the local potential for solar energy generation in the district?.” Assigned to this specific guiding question is an embedded hyperlink to Munster’s solar cadaster, which allows the user to evaluate the suitability of a selected rooftop for solar energy production. A guiding question that aims to address climate adaptation in the area of roof space utilization is “What is the potential for green roofs in the district?” To provide support in answering this question, the guideline also links to the green roof register of the city of Munster. To incorporate the aspect of internal administrative co-creation, the Transition Guideline asks “What role do different administrative units play in the development of implementation strategies for the climate-friendly use of roof spaces in the district?.” While the three topics of climate mitigation, adaptation and co-creation, are addressed individually in the form of guiding questions, they are also considered in an integrative manner. This was done through the posing of guiding questions on the linkages, synergies and potential trade-offs between the topics: “Where are synergies between the proposed climate mitigation and climate adaptation measures, and can climate mitigation and climate adaptation be combined in a single strategy?” Examples for linkages and synergies between measures contributing to both climate mitigation and adaptation on the district level are offered as guidance. This includes the dual use of roof areas for solar energy generation and green roofs or the climate adaptive renovation of existing buildings to enhance energy efficiency and reduce overheating.

To highlight the most crucial resources, including existing concepts and data, Section 4 presents comprehensive profiles of these elements. Each profile begins with a brief introduction, followed by a classification concerning liability and implementation. Subsequently, it provides pertinent information relating to Climate Proofing, detailing which aspects of the previously described five step process can be found within this source. The profile concludes exploring synergies with other significant sources of information. Several of the profiled concepts and data explicitly operate at the district scale.

This approach ensures that the Climate Proofing is tailored to the local context of Munster, preventing previously developed content and concepts from being overlooked or underutilized. Instead, it leverages and disseminates existing knowledge effectively. The Climate Proofing approach serves as a framework to consolidate these resources, making them accessible to various stakeholders through a systematic process. Additionally, the list of profiles can be continuously expanded and adapted, ensuring ongoing relevance and utility.

At this juncture, however, the limitations of the Transition Guideline became evident. While the guiding questions are designed to anchor the Climate Proofing process at the district scale, much of the conceptual data provided in Section 4, as well as the hyperlinks embedded in Section 3, primarily reference city-level information. This presents a methodological constraint, as it limits the ability of municipal staff and project participants to contextualize strategies and interventions within specific districts. Given Munster’s explicit focus on district-level climate action, as highlighted by the baseline analysis, the reliance on citywide datasets can obscure locally specific conditions (such as neighborhood land-use patterns, energy consumption behaviors, social structures, and vulnerability to climatic risks) potentially constraining the effective translation of city-level strategies into actionable, localized measures.

A critical enhancement to the Transition Guideline’s efficacy lies in the integration of spatially disaggregated carbon emission data at the district scale – specifically, data pertaining to the urban regeneration projects under consideration. Such granular data would prove particularly valuable during the Identify/Comprehend and Evaluate phases of the Climate Proofing process: the collection, provision, and utilization of district-specific GHG emission data enables the identification of high-priority intervention areas and facilitates the development of context-appropriate climate action measures for localized implementation.

Currently, Munster’s GHG emission inventory operates exclusively at the municipal level, lacking the technical capacity to disaggregate or downscale data to the district scale. This data gap constrains the ability to design tailored interventions that respond to the specific emission profiles and mitigation potentials of individual districts. Consequently, the development and integration of district-level carbon accounting methodologies into the Transition Guideline framework is recommended as an essential next step toward advancing climate-friendly district development within the city.

5 Discussion: insights from the Transition Guideline development process

The climate crisis requires cities to move beyond siloed approaches and to co-creatively address both mitigation and adaptation through integrated strategies that treat these dimensions as complementary elements of a unified response. Munster also faces intertwined challenges in transforming its building stock and existing urban infrastructures in ways that are both climate-mitigating and climate-adaptive. Yet, despite broad recognition of this necessity, Munster previously lacked a targeted, systematic, and integrated approach. The conducted baseline analysis revealed fundamental organizational barriers. Communication deficiencies create inconsistent understanding of climate objectives and core concepts, while departmental silos prevent effective knowledge exchange and coordination. Although various climate initiatives exist across the municipal administration, they operate independently without systematic integration, resulting in missed synergies.

Additionally, there is a critical misalignment between the city’s strategic ambitions and the practical means to implement them. While the city is pursuing integrated climate action in districts, its existing information and data structures do not provide sufficient support for evidence-based decision-making at this level. The development of the Transition Guideline represents a first attempt to strategically overcome these barriers. This section reflects the experiences and insights gained throughout this process. The aim is not only to evaluate the specific outcomes for Munster: by distilling key findings from the Transition Guideline development process, this discussion highlights both enabling conditions and structural challenges that are relevant for other cities seeking to co-creatively align mitigation and adaptation in urban development.

The experience of developing the Transition Guideline illustrates that research and development projects in urban planning rarely take place in a vacuum but rather enter urban contexts already shaped by existing strategies and initiatives. This was particularly evident in the case of Munster, a city that has committed to ambitious climate targets, participates in the EU’s Mission Cities initiative, and implements climate measures across seven key strategic domains. Despite this substantial strategic foundation, the governance landscape was marked by the mentioned organizational barriers. Therefore, the value of the project did not lie in producing isolated solutions but in the strategic integration of existing initiatives within a coherent co-creation framework capable of aligning mitigation and adaptation objectives. A crucial prerequisite for this integration was the combination of systematic baseline analysis and co-creative visioning. By deliberately avoiding preconceived technical fixes, the project process enabled Munster to develop a solution that is locally adapted and strengthens the broader climate strategy. This highlighted the importance of projects remaining flexible and open, ensuring that proposed interventions genuinely respond to local structures and challenges.

The development of the Transition Guideline also revealed that the creation of solutions is highly dependent on the quality of collaboration across municipal structures. In this regard, the co-creative development process of the Transition Guideline itself proved transformative. The setting brought together the Climate Staff Unit with other municipal departments that had previously worked largely independently, while also involving external partners. This broadened the perspectives feeding into the work and initiated new routines of cross-departmental exchange. Co-creation thus emerged not simply as a theoretical method but as an enabling lived practice for organizational change, helping to challenge siloed operational practices and establish a more integrated mindset toward climate mitigation and adaptation. Collaboration functioned as a form of internal capacity building, strengthening mutual understanding of climate-related challenges and empowering employees beyond the Climate Staff Unit to actively contribute to the city’s ambition of becoming climate-neutral by 2030. In this sense, the Transition Guideline was less a static product than a vehicle, laying the groundwork for sustained interdepartmental cooperation and embedding co-creation more deeply into municipal governance structures.

Yet the boundaries of this approach also became visible when the process sought to extend co-creation beyond the administrative sphere and include political actors. While researchers initially intended to engage city councilors to explore the role of emission data in political decision-making, this plan was rejected due to sensitivities and concerns about the political implications. As a compromise, access was granted to practitioners within the Climate Staff Unit. Although valuable, these insights could not replace the perspectives of elected representatives, leaving important knowledge gaps about how emission data is used in political deliberations. This episode highlights an important consideration for co-creation in municipal contexts: while structured processes can enhance collaboration within administrations, extending such collaboration into the political arena may face institutional boundaries that can affect openness, knowledge exchange, and the pace of innovation. These dynamics should be thoughtfully considered when implementing co-creation as part of evolving urban governance approaches.

Beyond organizational structures, integrated climate action also depends on an adequate data basis, without which targeted interventions in building stock and district-level infrastructures remain severely constrained. Although Munster has extensive data sets from annual carbon accounting, they are neither sufficiently linked to each other nor clearly presented and consistently accessible to city administration staff. As a result, evidence-based decision-making is often hindered by fragmented data structures and limited transparency. The Transition Guideline addressed this challenge by systematically organizing and consolidating the existing data landscape. In doing so, it increased transparency and created an overview of available resources. Moreover, it made it visible where critical deficits persist: The status quo for many cities is to conduct city-wide carbon accounting, based upon the downscaling of national level emission data to the urban level (GPC, 2021). However, whilst this provides an adequate perspective of a city’s scope one and two emissions, the data generally cannot be accurately downscaled further to the district level – although this approach is being developed (Rivera-Marín et al., 2023). This means that whilst urban regeneration projects may be grounded in notions of sustainability, they are flying blind from an actual carbon emission reduction perspective. This represents a form of data misalignment, where the decarbonizing goals and the actions intended to attain them cannot be measured in terms of their impact, because the data that is available is not suitable. This is not only an issue for Munster, but for all the city partners within UP2030, who are all, to varying degrees of scale and complexity, adopting a form of urban regeneration as their pilot project (UP2030, 2025).

Taken together, these insights highlight both enabling conditions and constraints of developing integrated approaches to urban climate action. The Transition Guideline made visible that flexible project frameworks, co-creative processes, and systematic data infrastructures are essential to align mitigation and adaptation objectives across municipal structures. At the same time, it revealed persistent gaps: the misalignment between strategic ambitions and the granularity of available data, and the institutional limits of co-creation when political decision-making remains out of reach. Rather than undermining the project, these challenges represent important findings in their own right. The Transition Guideline should therefore be seen less as an endpoint than as a step in an ongoing process. Making these deficits visible is itself a significant contribution, as it provides the basis for more targeted and effective future action. In this way, the Transition Guideline serves both as a catalyst for further change in Munster and as a reference point for other cities seeking to reconcile ambitious climate goals with the institutional and informational realities of urban practice.

6 Outlook and conclusion

The next critical step involves integrating and testing the Transition Guideline in Munster’s administrative structure as well as adapting it continuously as necessary. This step will depend significantly on establishing appropriate governance mechanisms to enable effective implementation and scaling beyond city administration.

A crucial aspect of establishing such governance mechanisms lies in strengthening the binding nature of the Transition Guideline within the administration. This ensures that the document is not only consulted but also actively applied in administrative practice. Equally important is effective communication between departments, which promotes transparency, creates a common understanding of the objectives and thus increases the likelihood of broad acceptance and adoption. Additionally, clear processes and responsibilities must be established to maintain the guideline as a living document: regular review cycles, transparent feedback mechanisms, the incorporation of emerging scientific insights and policy developments, and the gradual integration of spatially disaggregated data and district-level carbon accounting methodologies are essential to keeping it relevant, precise, and contextually tailored to Munsters climate action.

In terms of scalability, the Transition Guideline originally developed for the city administration of Munster, shows great potential for broader application by key external stakeholders. For urban planners and architects, it can serve as a strategic framework for closely aligning projects with the city’s climate goals while adapting solutions to local conditions. In the context of urban development initiatives, the guideline’s co-creation approach proves particularly valuable as it can support the integration of different perspectives into designs. Scientific researchers working with the city can also use the Transition Guideline as a structured methodology to promote integrated strategies that combine climate mitigation and climate adaptation.

Looking forward, the co-creation approach embedded in the Transition Guideline could also be extended to include a wider range of stakeholders beyond municipal administration and professional practitioners. Engaging citizens, community organizations, and local businesses in the implementation of integrated climate measures could enhance legitimacy, foster ownership, and strengthen the social foundation for urban climate transitions. Developing participatory mechanisms that enable such stakeholder involvement represents a promising avenue for future iterations of the guideline.

This empirical investigation presented the methodological framework of Climate Proofing applied in Munster, aiming to develop a Transition Guideline that facilitates the essential shift from isolated climate mitigation and adaptation initiatives to cohesive, co-creative urban climate actions. By documenting the Transition Guideline development process and extracting valuable lessons learned, this article offers transferable insights that can inform various municipal settings across Europe and beyond. The approach established through this research not only addresses the immediate needs of climate governance in Munster but also enriches the broader discourse on institutional climate-neutrality initiatives.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Cambridge, Department of Engineering. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AK: Project administration, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Investigation. SR: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Conceptualization. FL: Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. JT: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. WB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. TF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was funded by the EU Horizon Project UP2030. Publication costs are covered by the University of Stuttgart.

Conflict of interest

SR, FL, JT, and PS were employed by Buro Happold GmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. A Large Language Model was used to develop Table 1.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

BH, Buro Happold GmbH; GHG, Greenhouse gas; Transition Guideline, Guideline for Climate-Friendly Transition of Existing Urban Districts; UCAM, University of Cambridge.

References

1

Aboagye P. D. Sharifi A. (2024). Urban climate adaptation and mitigation action plans: a critical review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.189:113886. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2023.113886

2

Angelidou M. Froes I. Karachaliou E. Wippoo M. (2021, 2020). “Co-creation Techniques and Tools for Sustainable and Inclusive Planning at Neighbourhood Level. Experience from Four European Research and Innovation Projects” in Advances in Mobility-as-a-Service Systems: Proceedings of 5th Conference on Sustainable Urban Mobility, Virtual CSUM2020. eds. NathanailE. G.AdamosG.KarakikesI. (Greece: Springer), 562–572.

3

Avila-Garzon C. Bacca-Acosta J. (2024). Thirty years of research and methodologies in value co-creation and co-design. Sustainability16:2360. doi: 10.3390/su16062360

4

Cortekar J. Bender S. Brune M. Groth M. (2016). Why climate change adaptation in cities needs customised and flexible climate services. Clim. Serv.4, 42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cliser.2016.11.002

5

Espey J. Parnell S. Revi A. (2023). The transformative potential of a Global Urban Agenda and its lessons in a time of crisis. NPJ Urban Sustain.3:15. doi: 10.1038/s42949-023-00087-z

6

European Commission (2025). Urban Planning and Design ready for 2030. doi: 10.3030/101096405

7

Frantzeskaki N. Collier M. Hölscher K. Gaziulusoy I. Ossola A. Albulescu P. et al . (2025). Premises, practices and politics of co-creation for urban sustainability transitions. Urban Transformations7:7. doi: 10.1186/s42854-025-00075-9

8

Global Covenant of Mayors (2024) Data Portal. Available online at: https://data.globalcovenantofmayors.org (Accessed June 27, 2025).

9

GPC (2021). Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventories. Available online at: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/ghgp/standards/GHGP_GPC_0.pdf (Accessed July 7, 2025).

10

Grafakos S. Trigg K. Landauer M. Chelleri L. Dhakal S. (2019). Analytical framework to evaluate the level of integration of climate adaptation and mitigation in cities. Clim. Chang.154, 87–106. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02394-w

11

Grafakos S. Viero G. Reckien D. Trigg K. Viguie V. Sudmant A. et al . (2020). Neighbourhood sustainability: state of the art, critical review and space-temporal analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc.63:102477. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102477

12

Grazieschi G. Asdrubali F. Guattari C. (2020). Neighbourhood sustainability: State of the art, critical review and space-temporal analysis. Sustainable Cities and Society63:102477. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102477

13

Gu D. (2019). Exposure and vulnerability to natural disaster for world's cities. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Technical Paper No. 4. New York, NY.

14

Hassan G. F. Hefnawi A. E. Refaie M. E. (2011). Efficiency of participation in planning. Alex. Eng. J.50, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2011.03.004

15

IEA . (2024). Empowering Urban Energy Transitions. Smart cities and smart grids. Available online at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/00f7d520-d517-473d-b357-5adb43c4a57e/EmpoweringUrbanEnergyTransitions.pdf (Accessed July 7, 2025).

16

IPCC (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

17

Joshi N. Agrawal S. Ambury H. Parida D. (2024). Advancing neighbourhood climate action: opportunities, challenges and way ahead. NPJ Clim. Action.3:7. doi: 10.1038/s44168-023-00084-z

18

Joshi N. Agrawal S. Lie S. (2022). What does neighbourhood climate action look like? A scoping literature review. NPJ Clim. Action.1, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s44168-022-00009-2

19

Kaklauskas A. Rajib S. Kaklauskiene . L. Ruddock L. Bianchi M. Ubarte I. et al . (2024). A holistic approach to evaluate the synergies and trade-offs of city and country success. Ecol. Indic.158:111595. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111595

20

Kapetas L. Aili F. Tajuddin N. (2023). CORDIS – WP4 – UP-Grading – Piloting and demonstrating: D4.2 - UP2030 Implementation Plan for the pilot cities 2. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5066c5aaf&appId=PPGMS.

21

Kern K. Mol A. P. (2013). “Cities and global climate governance: From passive implementers to active co-decision-makers” in The Quest for Security: Protection without Protectionism and the Challenge of Global Governance. eds. StiglitzJ. E.KaldorM. (New York: Columbia University Press), 288–306.

22

Leino H. Puumala E. (2021). What can co-creation do for the citizens? Applying co-creation for the promotion of participation in cities. Environ. Plan. C, Politics Space39, 781–779. doi: 10.1177/2399654420957337

23

Lenk C. Arendt R. Bach V. Finkbeiner M. (2021). Territorial-based vs. consumption-based carbon footprint of an urban district - a case study of Berlin-Wedding. Sustainability13:7262. doi: 10.3390/su13137262

24

Mahmoud I. Morello E. Pasquinelli F. Rizzi F. (2021). Co-creation pathways to inform shared governance of urban living labs in practice: lessons from three European projects. Front Sustain Cities3:690458. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.690458

25

Mendizabal M. Heidrich O. Feliu E. García-Blanco G. Mendizabal A. (2018). Stimulating urban transition and transformation to achieve sustainable and resilient cities. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.94, 410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.06.003

26

Pizzorni M. Caldarice O. Tollin N. (2021). A methodological framework to assess the urban content in climate change policies. Valori e Valutazioni.27, 123–132. doi: 10.48264/VVSIEV-20212909

27

Qi J. Terton A. (2022). Addressing climate change through integrated responses: Linking adaptation and mitigation. In International Institute for Sustainable Development Policy Brief. Winnipeg. Available online at: https://www.iisd.org/publications/policy-brief/addressing-climate-change-through-integrated-responses (Accessed July 7, 2025).

28

Rivera-Marín A. Alfonso-Solar D. Vargas-Salgado C. Català-Mortes S. (2023). Methodology for estimating the decarbonization potential at the neighborhood level in an urban area: application to La Carrasca in Valencia city-Spain. J. Clean. Prod.417:138087. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138087

29

Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung, Bauen und Wohnen . (2025). Blankenburger Süden. Available online at https://www.berlin.de/sen/stadtentwicklung/neue-stadtquartiere/blankenburger-sueden/downloads/ (Accessed June 20, 2025).

30

United Nations (2015). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. New York: United Nations.

31

UP2030 . (2025). Urban Carbon Emission Data Mapping. Available online at: https://up2030-he.eu/2025/04/14/urban-carbon-emission-data-mapping/ (Accessed October 8, 2025).

32

Ürge-Vorsatz D. Rosenzweig C. Dawson R. Sanchez Rodriguez R. Bai X. Barau A. et al . (2018). Locking in positive climate responses in cities. Nat. Clim. Chang.8, 174–177. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0100-6

Summary

Keywords

climate change, urban planning, mitigation, adaptation, co-creation, climate proofing, carbon accounting, district level interventions

Citation

Krumm A, Rossi S, Leithner F, Theobald J, Brown W, Fernandez Lopez T and Scheibstock P (2025) Integrating climate mitigation and adaptation at the district level: co-creating a Transition Guideline for urban climate action in Munster. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1661038. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1661038

Received

07 July 2025

Revised

31 October 2025

Accepted

12 November 2025

Published

25 November 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by