Abstract

As CO2 emissions continue to rise and the impacts of climate change reach unprecedented levels, cities must accelerate the net-zero transition through rapid and effective action. The EU Mission for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities has made strong commitments to lead this transition, but securing the necessary resources increasingly requires leveraging innovative financing instruments (IFIs). This paper provides an exploratory empirical assessment of governance barriers and enabling conditions shaping innovative finance in Mission Cities, drawing on qualitative analysis of cities’ Climate Investment Plans and in-depth interviews with six Mission Cities (Barcelona, Münster, Parma, Pécs, The Hague, and Thessaloniki). The results reveal a high level of interest but limited uptake of IFIs, with many instruments remaining in conceptual stages. We identify six mutually reinforcing categories of barriers—fiscal and financial; legal and regulatory; institutional and capacity; behavioral and cultural; political and macroeconomic; and technological and market—through which instrument choices become constrained and cities remain reliant on grants and concessional loans. At the same time, progress is enabled by motivated municipal leadership, EU-funded technical assistance and peer learning, and prior “learning-by-doing” experience with specific instruments. Building on these findings, we propose governance-oriented recommendations across four areas to help cities move from plans to implementation: strengthening institutional and financial capacity, improving public engagement and acceptance, reforming national rules that constrain local fiscal tools and borrowing, and restructuring EU funding programmes to reduce administrative burden while deliberately building more effective, innovative, and blended urban climate finance.

1 Introduction

As global temperatures keep rising and many climate indicators reach record-breaking levels, the targets established by the Paris agreement are at stake: the net-zero transition requires urgent and substantial acceleration (IPCC, 2023; WMO, 2024; Copernicus Climate Change Service, 2024; UNEP, 2024). This challenge goes beyond technical and infrastructural change: it requires a deep socio-economic transformation. The need of socio-technical systems to transition towards a more sustainable paradigm has been addressed in literature for over 20 years (Kemp et al., 2007; Geels, 2002), leading to the development of the branch of literature dealing with transition theory (Geels and Schot, 2007) and specifically with sustainability transitions (Geels, 2011; Loorbach et al., 2017; Markard et al., 2012) and transition management (Rotmans et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2010; Loorbach et al., 2011). These transitions represent long-term, system-level changes toward more resource-efficient, low-emission and inclusive ways of living (Geels, 2018; Silva and Stocker, 2018). Furthermore, the concept of transformation is gaining momentum both in academic literature and in policy discourses (Hölscher et al., 2018), introducing a wider understanding of system change which includes power dynamics and focuses on larger scale changes compared to the notion of transition (Hölscher et al., 2018).

Cities1 are at the heart of this transformative change. Despite occupying only around 3% of the Earth’s surface, they are responsible for over 70% of global CO2 emissions (Joint Research Centre, n.d.). Moreover, projections show that they will host more than 70% of the global population by 2050, strengthening their key role as nodes of production, consumption, innovation and cultural exchange (World Bank, n.d.; UN DESA, 2019). The unique complexity of urban environments makes them a vulnerable target to climate impacts, but also a powerful engine of climate action and innovation (Wolfram, 2016; Nagorny-Koring and Nochta, 2018; Fuhr et al., 2018). Thus, the notion of urban transformation is becoming central in local policies (Tozer and Klenk, 2019) and has been described as a new “norm” in cities (Dixon et al., 2023). Relatedly, international literature on urban climate governance (Luque-Ayala et al., 2018; Romero-Lankao et al., 2018) has grown extensively and has fed the social and policy debates about the potential and limits of low carbon urbanism.

Recognizing this dual role of cities, the European Union (EU) has positioned urban areas at the center of its climate strategy. Under the Green Deal (European Commission, 2019) umbrella, it has launched the EU Mission for Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities, supporting 112 cities (hereinafter, the Mission Cities) in their commitment to reach climate-neutrality by 2030 (European Commission, n.d.). The Mission provides cities with technical and financial assistance, tools, and funding support to develop and carry out their climate strategies through the Horizon Europe-funded NetZeroCities project (NetZeroCities, n.d.). As part of the Mission, cities are required to co-develop and sign a Climate City Contract (CCC)—which outlines transformative actions that the city commits to carry out—and related 2030 Climate Neutrality Investment Plan (IP) which defines how they will be financed. Between 2022 and 2024, 53 cities were awarded the EU Mission Label, and in 2025, 39 more received it, bringing the total up to 92 cities as of the writing of this paper (European Commission, 2025).

Nonetheless, the ambitious goal set by Mission Cities faces a major constraint: the lack of adequate funding (Ulpiani et al., 2023; Kaufmann et al., 2024). According to the OECD (2020), the current volume of climate finance is insufficient to meet the scale of investment required, particularly in urban contexts. Urban mitigation finance needs are estimated to be USD 4.3 trillion annually from now until 2030, and over USD 6 trillion per year from 2031 to 2050 (CCFLA, 2024). An analysis by Bankers without Boundaries (BwB, 2025) of the Climate Neutrality Investment Plans developed by Mission Cities estimated that EUR 307 billion is required for cities to reach climate neutrality by 2030, which in turn will generate total benefits of EUR 394 billion. Yet public and concessional finance is increasingly constrained, as fiscal pressures and competing priorities limit the growth of grant-based and low-cost financing (OECD, 2023c; IMF, 2023). Moreover, cities often lack both financial resources and institutional capacity to plan and implement climate-neutral infrastructure at scale (Giacomelli et al., 2025). In light of different structural and fiscal constraints, they must look beyond traditional public funding to mobilize the scale of investment required for climate transitions. Innovative financing instruments (IFIs) are increasingly being promoted as crucial tools to mobilize private capital and diversify urban climate finance portfolios (OECD, 2022b; UN-Habitat, 2021).

Building on earlier definitions in the literature, this paper considers innovative climate finance to include non-traditional sources, mechanisms and instruments specifically designed to mobilize additional resources for climate action, particularly those that engage private-sector actors (Sandor et al., 2009; UNDP, 2012; UN DESA, 2022; Carter and Boukerche, 2020; Gouett et al., 2023). These include financing instruments—financing mechanisms, funding sources and fiscal tools—that go beyond standard public financing approaches, such as blended finance, green bonds, and risk-sharing instruments. As such, the emphasis is not just on novelty, but on effectiveness, and the ability to address existing financing gaps. In contrast, traditional sources of finance typically include concessional loans, grants, intergovernmental fiscal transfers, municipal budget allocations, and other forms of public expenditure. The concept of innovative finance is fluid and context-dependent: what is considered innovative in one city at one point in time may become mainstream in another, and it might depend on the institutional and financial capacity of the specific municipality and the access to resources. Accordingly, we look at IFIs as a broader class of tools and approaches that could leverage new or underutilized sources of capital and enable a more strategic use of public funds to unlock additional finance for urban climate transitions.

Initiatives involving private actors in the implementation of public policies—particularly through blended finance and Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)—are increasingly recognized as promising, though not without important risks. Previous research has highlighted critical challenges linked to the use of private finance initiatives (PFIs) in PPPs. For example, PFIs can generate affordability problems for the public sector, as the costs of repaying private finance with interest may place a significant burden on public resources, potentially diverting funding from essential services and resulting in budget constraints and cuts (Hellowell and Pollock, 2007). Empirical analyses have further documented that PPP-based procurement often entails higher costs than traditional public procurement methods (Bing et al., 2005). In addition, extensive literature suggests that PFIs may undermine transparency and democratic accountability in public service provision (Hodge and Greve, 2007). It is also reported that many public authorities have encountered challenges in managing the complexity of PFI contracts due to experience gaps leading to unfavorable contract terms and difficulties in sustaining effective partnerships with private actors (Matti, 2015). On the other hand, beyond numerous international policy reports (World Bank, 2024; CPI, 2025; GGGI, 2023; OECD, 2023b), a growing body of scientific literature emphasizes the crucial role of PPPs and PFIs in supporting climate action at multiple levels (Casady et al., 2024; Vassileva, 2022; Fuglsang, 2014; Adhikari and Chalkasra, 2023). Innovative climate finance mechanisms—including PPPs, blended finance, and catalytic instruments—have shown potential to mobilize substantial additional resources for climate adaptation and mitigation, particularly within the accelerated trajectory towards net zero (Omukuti et al., 2024). These financial instruments require careful design, governance and monitoring to ensure their effectiveness and to mitigate the documented risks.

However, despite growing political and institutional interest in these instruments, their actual use by cities remains limited. A recent survey of Mission Cities found that over 75% had no experience with innovative financing mechanisms, even though most expressed a strong interest in using them (Ulpiani et al., 2023). This points out a persistent gap between interest and implementation, highlighting deeper governance, institutional, and market barriers that hinder uptake. Literature has so far provided valuable insights into the local governance of climate policy (Betsill and Bulkeley, 2003; Wolfram, 2016; Nagorny-Koring and Nochta, 2018; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., 2019), and specifically into the governance dimensions of climate finance (e.g., Bracking and Leffel, 2021; Browne, 2022; Richardson, 2009), as well as into the role of policy capacities in allocating climate funding at central government level (Raudla et al., 2025). However, it has yet to fully address the specific challenges posed by the deployment of innovative financing solutions at different levels of governance. So far mainly international reports dealt with the implementation of innovative finance in cities (e.g., OECD, CCFLA, UN-Habitat, Eurocities, NetZeroCities), thus, arguing for further academic research. This article aims to contribute to filling this gap, trying to understand how Mission Cities can unlock and scale finance for their net-zero urban transition. To do so, the paper builds on the governance implications of sustainability transitions and experience of local climate governance in designing and implementing ambitious climate policies and develops a categorization of barriers and enablers to investigate in detail the governance enablers and barriers that Mission Cities face in deploying IFIs. This is the first exploratory study of its kind, and we do not aim for extensive literature review on the enablers and challenges, but to provide extensive empirical insights of an area that has not yet been studied before. Specifically, we analyzed the Investment Plans developed by a sample of Mission Cities and complemented the analysis with qualitative in-depth interviews with city officials and practitioners involved in the IPs elaboration. Our aim is to provide insights into how cities are approaching climate finance innovation in practice, and to identify related key lessons for improving the governance and effectiveness of urban climate transitions. With this, we also provide additional research avenues at the end of this paper.

To address all relevant aspects of the empirical study, the paper is structured as follows. First, it reviews the relevant literature and introduces the analytical framework used to assess barriers and enablers to the uptake of IFIs. Second, it describes the materials and methods. Third, results and empirical findings of the IP analysis and interviews are presented. Fourth, the findings are discussed together with the main contribution of this study, namely the identification of enablers to address key barriers, drawn from both city practices and author recommendations. The paper concludes by synthesizing key insights and outlining limitations and areas for further research.

2 Analytical framework

Currently, the effective use and uptake of IFIs remains uneven (NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023; Eurocities, 2024). The literature on urban environmental governance demonstrates that indeed, many challenges are impeding the implementation of ambitious climate policies (Granqvist and Mäntysalo, 2020; Correa do Lago et al., 2023) including also design and implementation of IFIs. We claim that several obstacles that local governments experience are inherent to the complexity of sustainability transitions, stemming from the multidimensional, directional, disruptive, and uncertain nature of these processes (Geels, 2011; Markard et al., 2012; Loorbach et al., 2017), which make the governance of change particularly complex (Hölscher et al., 2018; Papin and Fortier, 2024), and this also at the local level. Furthermore, these studies emphasize the need to mobilize a broad base of actors of change, promote action and knowledge sharing across different social-networks (Bulkeley and Castán Broto, 2013; Wolfram, 2016; Papin and Fortier, 2024), sectors and governance levels. They argue for policy mixes, experimentation, creativity, feedback systems and learning (Frantzeskaki et al., 2018; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023; Tõnurist et al., 2019; Späth and Rohracher, 2012). Next, the key implications from local climate governance and how they are related to the broader governance implications of sustainability transitions are presented.

First, different social, cultural and behavioral factors are essential, e.g., as a broader challenge, the insufficient engagement of stakeholders for effective climate action has been widely discussed (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2013; OECD, 2022a,b; Montfort et al., 2025). Accordingly, the lack of involvement may result from a general unwillingness to participate, often linked to the additional costs associated with sustainable or innovative practices (Nurse and Fulton, 2017; Averchenkova et al., 2021; Huovila et al., 2022; Ohene et al., 2022), or from a lack of awareness on climate issues (Papin and Fortier, 2024). As transitions involve winners and losers (sustainable innovation versus the engagement of incumbents and potential losers), it specifically argues for a polycentric governance model that needs to involve flexible and self-organized activities carried out by non-state actors (EEA, 2019).

Second, institutional factors within local governments also play a critical role. The persistence of siloed organizational structures (Averchenkova et al., 2021; Nurse and Fulton, 2017; Frantzeskaki et al., 2018) often leads to fragmented policy implementation, limits the exchange of knowledge among municipal departments, and hinders the necessary interconnections between urban systems (Correa do Lago et al., 2023; Quitzau et al., 2022). As transitions are accompanied by surprises and unintended consequences, they argue for monitoring, reflexivity and adaptive governance to ensure directional flexibility and addressing side-effects (EEA, 2019). Relatedly, a key issue emphasized frequently by many scholars is the lack of long-term planning. As transitions are open-ended and uncertain, they demand portfolio approaches, project-based learning and experimentation, especially with radical innovations (social, technical, business models) in early transition phases (Loorbach et al., 2017). However, urban climate governance often remains project-based and program-driven, resulting in fragmented efforts rather than coherent, long-term, and integrated strategies (Wolfram et al., 2019; Eurocities, 2024; CCFLA, 2024; Huovila et al., 2022; Correa do Lago et al., 2023). This has led to the proliferation of pilot projects (Papin and Fortier, 2024) without the development of enduring strategies capable of inducing systemic change (Nagorny-Koring and Nochta, 2018).

Third, legislative and jurisdictional constraints represent another important category of barriers and enablers (Bracking and Leffel, 2021; Averchenkova et al., 2021; Casady et al., 2024; UNECE, 2023) as local governments frequently operate under limited legal authority, restricting their capacity to effectively address major sources of greenhouse gas emissions (Ohene et al., 2022; Linton et al., 2020; Laine et al., 2020; Correa do Lago et al., 2023). As transitions are characterized by goal-oriented directionality and urgency, they need indications about the general direction of action (e.g., through financial incentives, regulation and broad goals, target and visions), and more specific indications about innovations and alternative pathways (e.g., through roadmaps and foresight exercises), as well as require stronger innovation and diffusion policies, the phase-out and exnovation of policies through bans or stronger environmental regulations (EEA, 2019), which is challenging due to legislative and jurisdictional constraints (OECD, 2022a,b; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023).

Fourth, well-known technological and institutional lock-ins that have been long studied within the transition theory literature (Geels and Schot, 2007; Hölscher et al., 2018; Seto et al., 2016; Foxon, 2002; Eitan and Hekkert, 2023) are also hindering the uptake of ambitious climate policies locally (Hölscher and Frantzeskaki, 2020). Institutional and regulatory factors (Arthur, 1994; North, 1990; Unruh, 2002), economic rules and contracts, as well as social conventions and codes of behavior feed and increase carbon lock-in (Unruh, 2000, 2002). These formal and informal institutional constraints create drivers and barriers for social change over time and influence economic performance (North, 1990).

The previously described interlink set of implications from local climate governance and sustainability transitions governance span legal, fiscal, behavioral, and institutional domains (Alexander et al., 2019; CCFLA, 2015) and stem both from internal limitations (e.g., capacities to develop bankable projects) or external constraints (e.g., national regulations or coordination across government levels). Drawing upon the existing literature, we propose a framework of six main barriers’ and enablers’ categories as the analytical ground for the empirical study conducted.

First, institutional and capacity aspects, including all factors related to phenomena such as learning effects for organizations that arise because of the opportunities provided by the institutional framework, as well co-ordination effects (Frantzeskaki et al., 2018; Fairbairn, 2022; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023) and adaptive expectations, occurring because the increased presence of contracting based on a specific institutional framework reduces uncertainty about the continuation of that framework (Arthur, 1994; Pierson, 2000; Dicks and Fulghieri, 2023). Limited capacity (Frantzeskaki et al., 2018; Fairbairn, 2022; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023) and expertise are also a limitation to leveraging alternative financial streams, slowing down the development of investor ready and “bankable” project proposals (Ulpiani et al., 2023). Closely related to the first one, the second category refers to behavioral and cultural barriers and enablers. As investigated in the “co-evolutionary” approaches (Rip and Kemp, 1998; Kemp et al., 2007; Geels, 2002) to understanding technological change, the development of technologies both influences and is influenced by social, economic and cultural settings in which they develop (Rip and Kemp, 1998; Kemp, 2000; Fritsch et al., 2019). Within this point of view, also informal constraints and drivers such as social conventions and codes of behavior have a direct influence on the uptake of climate mitigation technologies among communities (technological lock-in effect) and on the uptake of IFIs among employees of the local administration of the Mission Cities (institutional lock-in effect) (Foxon, 2002; Seto et al., 2016). The third category deals with legal and regulatory factors (Bracking and Leffel, 2021; UNECE, 2023; Casady et al., 2024). These stem from the national level overarching taxation and climate-related policies that can either drive or inhibit urban transition, as in the case of the latter they may not support or cater to the specific needs of Mission Cities. These could create a situation of regulatory uncertainty, which limits both local administration in undertaking innovative financing initiatives and private-sector investors to take up risks associated with political uncertainty (NetZeroCities, 2024). The fourth key category is fiscal and financial aspects (NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023; Ulpiani et al., 2023; Casady et al., 2024). As national regulations may limit the powers of municipalities to raise funds, increase taxes or borrow money, cities are left with limited sources of finance to subsidize the net-zero transition, calling for a pressuring need to further involve private investors in climate-related investments as long stressed out by international organizations (Betsill and Bulkeley, 2003; Rosenzweig et al., 2018; OECD, 2023c). On the other hand, clear legal mandates and supportive regulatory frameworks allow for the implementation of innovative solutions (Heinrichs et al., 2013; Averchenkova et al., 2021; Montfort et al., 2025) The fifth category is political and macroeconomic factors (Eurocities, 2024; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023), which account for the national and international geopolitical phenomena that can drive or inhibit local financial choices. Market instability, including currency fluctuations, inflation, and unpredictable regulatory changes, introduces risks that increase financing costs or deter private investment (Carter and Boukerche, 2020). Policy uncertainty, particularly regarding tax incentives or climate-related subsidies, further exacerbates investor hesitation. As a final category, we consider technological and market factors that can act as both barriers and enablers (CCFLA, 2024; UNECE, 2023; Castán Broto and Sudmant, 2022). Barriers include all technological lock-ins such as path dependency, positive feedbacks and network economies, that constitute a persisting barrier to the implementation and uptake of financing innovations (David, 1985; Arthur, 1994; Seto et al., 2016).

Besides the aforementioned factors, the crucial role of cities in developing innovative governance instruments through the process of “urban experimentation” deserves special attention as a governance approach that supports the development and testing of novel solutions to urban challenges, particularly those related to climate resilience and sustainability (Mukhtar-Landgren et al., 2019; Bulkeley et al., 2013; Frantzeskaki et al., 2018; Papin and Fortier, 2024; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023; Eurocities, 2024). Through pilot initiatives, cities serve as living laboratories where innovations—technical, social, or financial—can be evaluated and adapted for broader implementation. Among these innovations, financial instruments and institutional arrangements have emerged as critical enablers. Cities are particularly well positioned to drive financial innovation (Castán Broto and Sudmant, 2022; UNECE, 2023) through their ability to establish collaborative platforms, engage in “learning-by-doing” processes, and coordinate diverse stakeholders in testing and scaling new financial models (Ulpiani et al., 2023). One example is the development of green bonds in cities, which have been proven effective in mobilizing capital for climate-related infrastructure and environmental projects (Thioye, 2021). Local governments can influence the growth of green finance by aligning public policies with sustainable investment goals, creating enabling environments for private sector participation, and designing incentives for inclusive financial instruments. In this context, diversification of the investor base—including the mobilization of local and retail investors (NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023; Eurocities, 2024)—emerges as another critical enabler (OECD, 2020). Ultimately, the transition to innovative finance systems (Bhatnagar and Sharma, 2022; Frantzeskaki et al., 2018) also relies on inclusive governance and active public engagement, which can be steered by cities. As such, fostering local participation, whether through public consultation, participatory budgeting, or community-based investment platforms, can significantly enhance the social legitimacy and responsiveness of financial innovation (Bhatnagar and Sharma, 2022).

3 Materials and methods

To gain an in-depth understanding of the barriers faced by the city administrations in deploying IFIs, and the potential enablers which supported it, we employed a qualitative methodology approach.

First, we reviewed the IPs of all 53 Mission Cities that were labeled in Window 1 and Window 22 of the NetZeroCities Mission. While the Action Plans are publicly accessible on the NetZeroCities platform, the accompanying IPs, which detail the financial strategies and resources required to implement the Action Plans, are confidential and available only to NetZeroCities finance partners and the European Commission. The CCC has three main documents: the Investment Plan, the Action Plan, and the Commitments document. The actions of cities to reach net-zero by 2030 are described in the Action Plans, whilst the actions described are calculated and financially analyzed in the IPs. For our analysis, we focus on the IP as this contains information on IFIs and related barriers and enablers (if documented by the city partners). The IP structure template helps cities craft detailed, actionable financial strategies for achieving climate neutrality by 2030. It is structured in three main parts: Part A maps the current climate investment landscape, including past funding, strategic finance evaluation, and barriers to capital deployment; Part B focuses on defining the investment pathways needed to deliver on climate goals, through cost scenarios, capital planning, and financial indicators for monitoring progress; and Part C outlines the enabling conditions for successful implementation, such as supportive policies, risk management frameworks, and capacity building through stakeholder engagement. Together, these sections ensure cities can identify needs, attract funding, and operationalize their climate plans.

The preliminary analysis encompassed all submitted IPs available at the time, namely the cities that were awarded the Mission label in Window 1 and Window 2 (53). Cities were categorized according to their mention of IFIs in their IPs. This classification is based on a qualitative review of the investment plans and municipal documentation, focusing on whether references to IFIs were explicit and clear, or if the city did not clearly mention their interest in or use of IFIs. Investment plans were not analyzed in-depth; instead, we used a keyword-based analysis, specifically making sure that the city made explicit mention of “green bonds” “innovative financing” “innovative finance” and “PPPs” or “public-private partnerships.” Based on this, cities were grouped into two categories, cities that mentioned these IFIs versus cities that did not explicitly mention them. Almost all cities (49) mentioned IFIs in some capacity, showing clear interest in the topic among cities. Following this preliminary categorization, cities were shortlisted for qualitative interviews. It should be clear that cities that mentioned IFIs do not necessarily use them today; the mentions could refer to their interest in exploring the use of IFIs or the city’s reasoning why they do not use IFIs.

Once we established cities’ engagement and intentions regarding IFIs, the selection of a representative sample aimed to capture a diverse range of urban scales. City size, measured by both population and physical area, was used as a proxy for variations in municipal capacity, governance complexity, and financing needs. The selection process prioritized a balance of geographic distribution, city size, and differing levels of experience and ambition related to IFIs. To ensure this balance, cities were categorized according to established typologies based on both population and area size. For population, we apply the OECD classification, defining small cities as those with fewer than 250,000 inhabitants, medium-sized cities as those with 250,000–500,000 inhabitants, and large cities as those with more than 500,000 inhabitants (Dijkstra et al., 2019). For city area, we classified cities with less than 100 km2 as small, those with 100–250 km2 as medium, and those over 250 km2 as large. Based on these criteria, we developed a list of 15 cities to be contacted. We also ensured to include cities that: (1) either signaled some level of past experience, and, or showed broad intentions to apply multiple instruments in the future, categorizing them as “high”; (2) cities that referred to IFIs with some clarity and showed moderate future intentions, but without clear indication of past experience, we categorized them as “medium”; and last (3) cities that only vaguely mentioned IFIs, with no clear evidence of past experience, we categorized them as “low.”

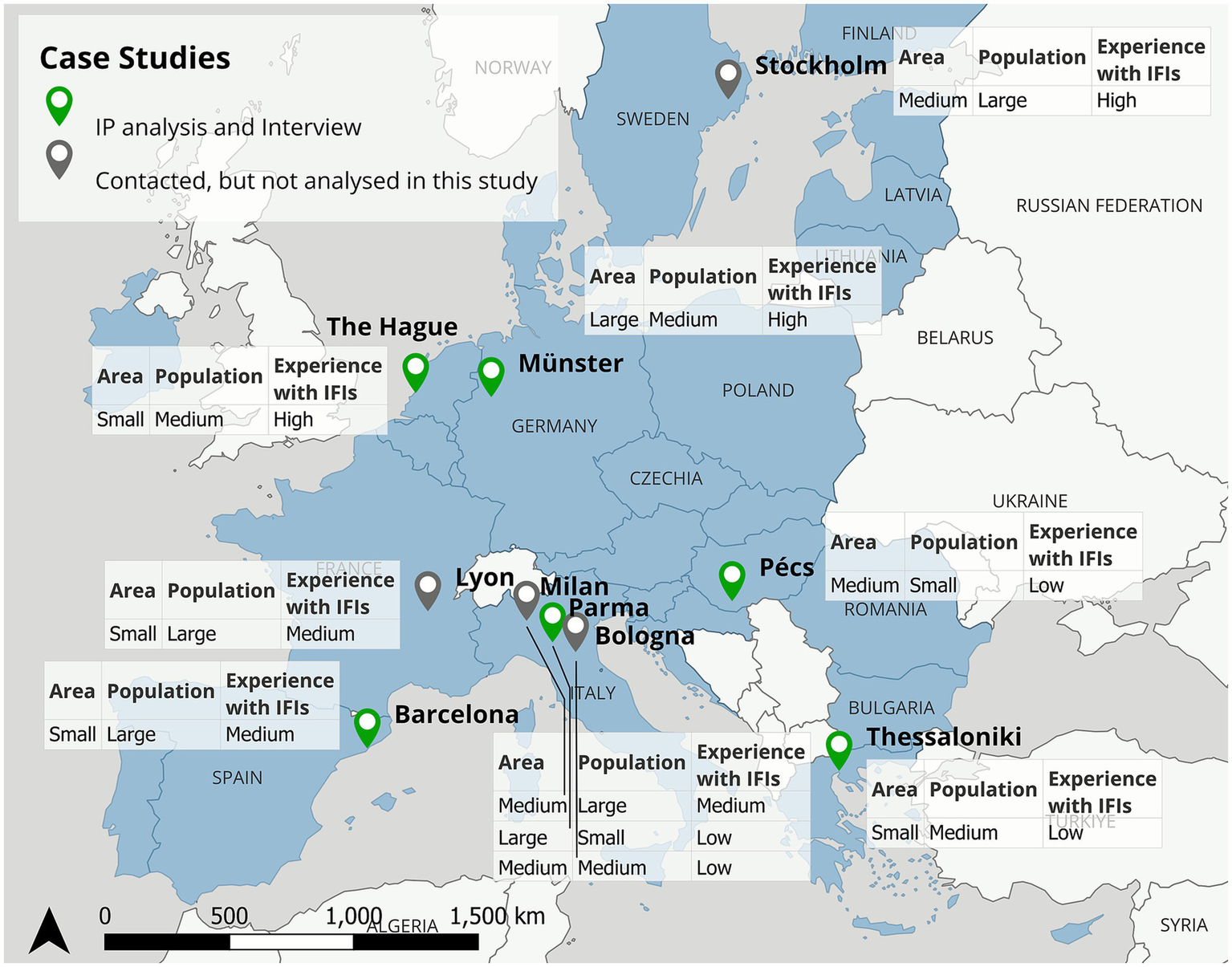

As per availability of direct contacts out of these shortlisted cities, we contacted 10 city authority representatives for approval for analyzing their IPs and asked for their availability for the interviews. Out of the ten cities (see Figure 1), six cities agreed with sharing their IP for analysis and conducting the interview, whilst one could not share its IP due to non-disclosure agreement, one approved but was not available for the interview within the timeframe of this study, and three did not respond to our e-mails. The six cities to be analyzed and interviewed were Barcelona (Spain), Münster (Germany), Parma (Italy), Pécs (Hungary), The Hague (Netherlands) and Thessaloniki (Greece).

Figure 1

Cities selected for analysis.

It is important to acknowledge that the selection of cities included in this analysis is subject to several layers of selection bias. First, all cities in our sample are part of the EU Cities Mission after voluntary application, which already indicates a predisposition towards innovation, climate action, and participation in EU-led initiatives. Second, given the high number of applications, a selection process was conducted to identify the 112 cities that were ultimately chosen to participate in the NetZeroCities programme. Third, within this already selective group, our analysis focused on those cities that had completed and submitted their Climate City Contracts (CCCs), including the IPs, and had received the Mission Label, signaling that their proposals met specific quality criteria set by the European Commission. As a result, the findings of this study are based on a subset of cities that are not representative of all European municipalities, but rather of those at the forefront of the climate neutrality agenda, with higher-than-average institutional capacity and political will.

As a final step under the IP analysis, we conducted an in-depth analysis of IPs of these six cities. Our analysis focused on the financing instruments distinguishing between those that have already been implemented and used, and those the municipality explicitly intends to use, further categorizing according to traditional or innovative. Additionally, we explored barriers and enablers mentioned in the IPs.

Second, to clarify, deepen and triangulate the understanding gained from the IP analysis of selected cities, we conducted in-depth interviews with officials from relevant cities’ administrations. The interviewees were selected based on their primary role or involvement in the development of the Investment Plan itself or having a role as a key financing expert of the municipality (i.e., Director of the Environmental Department or Energy Department of the city, Vice Mayor and similar). See the Annex to find more information about interview dates and city representatives present. While the interviews were designed and structured based on the content of the IPs, they also served as a means to verify, contextualize, and, where necessary, correct or complement the information presented in the IPs. In cases where discrepancies arose between the IP and the information provided by city representatives, we prioritized the interview data as the most up-to-date and context-specific source. This approach reflects our assumption that the interviewees, being directly involved in implementation or financing decisions, could provide more accurate and current insights into the status and rationale of the investments. To deepen the insights reported in the IPs, we developed a questionnaire to investigate further the barriers and enablers that challenged or enabled the cities to use IFIs. The questionnaire is divided into four subsections, that can be summarized as follows:

-

Opening: general understanding of the IP elaboration process.

-

Innovative Finance and Governance: did the city use any IFIs? Which ones? Alternatively, does the city plan to use any IFIs? Which have been governance barriers and enablers to their implementation?

-

EU Funding: how dependent is the city on EU funds to finance the green transition?

-

Closing: General comments and needs of the administration to make the city’s climate finance more effective.

The online interviews were conducted from May to August 2025. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and the transcriptions were manually analyzed in Excel, where several tables summarizing the main findings were developed. The results of the interviews contributed to a clear overview of the experience of different cities with the use of IFIs, allowing us to trace trends and relevant patterns in their adoption—with a focus on governance—and identify instruments and sources that have not been mentioned by the IP.

Furthermore, for analyzing the interview data, we combined the Excel tables on the information collected using AI (ChatGPT 4o) into a master database, cross-checking the output manually for accuracy and completeness. We listed and categorized all financial instruments mentioned in the IPs and interviews into common categories (such as municipal funds, soft loans, municipal budget) to identify key themes and unique sources among cities. We then separated instruments according to whether they were innovative or traditional. We also collected information on the instruments whether they were (1) “implemented,” i.e., already used (currently or in the past), thus the city has experience with them; (2) “planned” to be implemented, in cases where the city signaled strong intention of implementing certain instruments; in mixed cases (3) “implemented and planned,” indicating that the instrument is currently in use or the city has experience with it, but also foreseen for continued or expanded application in the future; and “conceptual,” in cases when a city indicated an instrument it may use when several conditions are fulfilled in the municipality (governance, capacity and, or regulatory changes, etc.) for implementation. To differentiate between planned and conceptual stages, we applied a subjective interpretation based on the available data: instruments marked as “planned” reflect a clearer municipal commitment or preparatory steps toward implementation, whereas those marked as “conceptual” indicate early-stage interest that is currently hindered by governance barriers. This categorization was necessary as cities did not consistently indicate the status of each instrument, and in some cases, judgments were made based on the context provided in interviews and investment plans.

Similarly, for the barriers and enablers analysis, we categorized those mentioned by both IPs and the interviews according to the 6 categories identified in the Analytical framework section: (1) behavioral and cultural, (2) fiscal and financial, (3) institutional and capacity, (4) legal and regulatory, (5) political and macroeconomic and (6) technological and market. To identify trends, similarities and outliers in barriers, we subcategorized barriers highlighted by city partners. The barriers and enablers identified in the analysis are based on what cities explicitly stated or clearly indicated in their investment plans and interviews. The findings reflect the challenges as reported or acknowledged by municipal representatives and may not capture all underlying or structural barriers unless they were directly mentioned or implied by city officials. Whilst the discussions mainly focused on barriers, we also collected specific enablers highlighted by cities in their investment plans and during the interviews.

4 Results

Using the keyword based qualitative review, we found that 49 of these cities explicitly referenced IFIs, whilst only 4 omitted them, or referred to them only vaguely. Based on the case selection criteria outlined in the previous section, we conducted an in-depth analysis and interviews with six cities. The selected cities reflect a diverse range of engagement with IFIs and urban scales, capturing variation in both population size and geographic characteristics.

4.1 Financing instruments used and planned

Table 1 presents an overview of innovative and traditional financing instruments identified across the six selected cities. The classification shows instruments at various stages of adoption, from conceptual (C) to implemented (I) or planned (P), with nuances such as implementation in progress (I*) or implemented as pilots (I**), or dual statuses (I + P), i.e., it is or has been used already, but the municipality also indicated future use.

Table 1

| Instruments identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovative | ||||||

| Carbon trading / credit mechanisms | C | C | C | |||

| Crowdfunding | I + P | P | ||||

| Green bonds | I* | I | C | P | C | |

| Green loans | I + P | P | ||||

| Land value capture | C | |||||

| Municipal charges and fees linked to emissions | I | |||||

| Municipal debt pooling | P | |||||

| Municipal funds | P | P | P* | I + P | ||

| Non-financial incentives | C | C | ||||

| On-bill financing | P | C | ||||

| Philanthropic donations | P | |||||

| Pooled procurement (EU-level) | C | |||||

| PPPs | I + P | P | I + P | I + P | P | C |

| Property-tax-linked financing | P | |||||

| Tax incentives and disincentives | I + P | C | C | C | ||

| Urban tolls (congestion charge) | P | |||||

| Traditional | ||||||

| Commercial loans / credit lines | I | I | ||||

| Concessional (soft) loans | I + P | P | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P |

| Forward financing | I | |||||

| Municipal budget (own source revenues and national government transfers) | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P |

| National, regional (indirect) & direct EU grants | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P | I + P |

| Subsidiary sale proceeds | I | |||||

Overview of innovative and traditional financing instruments.

I: implemented; I*: implemented (as a pilot); I + P: implemented and also planned; P: planned; C: conceptual.

Evidence highlights the foundational role of municipal budgets, European grants and loans from the European Investment Bank (EIB) across all cities. However the extent each city relies on these traditional sources varies greatly. All cities indicated that a limited part of their budget can be used for climate related activities and that the role of EU funding is critical. For example, Barcelona utilizes annual savings they obtain from their budget to finance climate action. Concessional (soft) loans are also a key source of finance for climate initiatives, however only western cities were observed to use of commercial debt instruments (loans, credit lines), due to the cities’ favorable credit rating, leading to lower interest rates.

A clear finding of our work has been the strong interest from cities in financial innovation in order to scale up direct private investment, private financing or co-financing. Cities have experience in co-financing through European programmes (e.g., an RRF, EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility supported by the development of electric vehicle charging network in Thessaloniki). Among IFIs, public-private partnerships (PPPs) are the most widely used or planned to be used, mainly for mitigation projects (such as infrastructure, mobility and energy transition) through concessions, joint ventures, in a shared public-private investment mechanism (through a special purpose vehicle). Energy performance contracts (EPCs), a type of PPPs, are also widely applied, e.g., for public lighting development in Parma and Pécs, with further plans to use them for building refurbishments and energy investments. Municipal funds also show promising where it has been applied previously: The Hague has extensive experience in revolving and thematic funds, with a notable example of the HEID (Stichting Holdingfonds Economische Investeringen Den Haag), the holding fund of the municipality, which channels national and European public funds into sector-specific investment sub-funds to co-finance sustainable urban projects. Although private investment in these sub-funds remains limited, further financial innovation could mobilize additional private capital, consistent with the city’s stated ambition. Additionally, with the support of the Hungarian Development Bank, Pécs set up an “Urban Development Fund” to provide equity finance for small-medium enterprises (SMEs). Green bonds are widely considered across cities, yet only Münster has implemented them successfully, as a result of considerable preparatory work and the introduction of the Sustainable Investment Framework. Other innovative instruments, such as tax incentives and disincentives (e.g., emission-related taxes), property-tax-linked financing, crowdfunding, on-bill financing, and carbon market mechanisms are also being explored, but are in conceptual phases due to various governance barriers, unpacked in the following section.

In summary, IFI deployment across the six cities reveals significant variation in both the number and maturity of tools being considered or applied. Barcelona stands out with a wide range of instruments, reflecting both broad conceptual interest and progress toward implementation. Parma and Pécs demonstrate more selective engagement, primarily in planning stages but with high interest in learning and trying different IFIs given their limited funds available. Both Münster and The Hague listed fewer IFIs overall but have mobilized significant amounts through a small number of well-tested instruments, indicating that learning from and replicating successful mechanisms can be as important as introducing new ones. In contrast, Thessaloniki remains largely at the conceptual stage for most proposed IFIs. Overall, while interest in innovative financing is prominent in all cities, many instruments remain in the planning phase, highlighting the need to address the barriers and support needs that hinder their implementation.

4.2 Barriers identified across cities

As Table 2 demonstrates, the lack of private sector investment into net-zero projects was identified to be driven by two behavioral forces: reluctance to engage with private actors by the municipality and resistance to invest into climate initiatives by the private sector, due to (e.g., political) risk aversion and lack of awareness or outright opposition to certain projects. For example, Pécs highlighted that “many residents do not understand climate neutrality and net-zero targets.” Hesitancy to engage with the private sector is exacerbated by the resistance to change and preference for business-as-usual approaches. Reluctancy stems from different causes: The Hague indicated “early political reluctance” in giving up public control over HEID’s sub-funds. Whilst traditionally left-leaning political culture is cautious of market-based approaches in Barcelona. Parma indicated past negative experiences with PPPs, resulting in debt burdens.

Table 2

| Barriers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional lock-in | x | x | x | x | ||

| Risk aversion by investors and stakeholders (higher perceived risk of climate projects) | x | x | x | x | ||

| Lack of public awareness about the benefits of climate investments | x | x | x | |||

| Historical reluctance to collaborate with private actors | x | x | x | |||

| Community opposition to certain energy projects | x | x | ||||

| Politically difficult to increase taxes | x |

Behavioral and cultural barriers.

Despite differences in size, geography, and financing structures, all cities highlighted that funding and financing is insufficient from both public and private sources, with these barriers being the most wide-spread and prominent across all barrier categories. All cities reported constrained budgets for climate-related measures and investments exceeding available resources, leading to heavy reliance on national and European funds (see Table 3). This points to widespread structural limitations to revenue generation for climate initiatives.

Table 3

| Barriers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited (or no) municipal budget dedicated to climate-related measures | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Heavy reliance on national and European funds | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Limited fiscal autonomy to raise or introduce new taxes | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Limited financing capacities or access to finance by households and SMEs | x | x | x | |||

| Lack of financial incentives to private sector | x | x | x | |||

| Low fiscal autonomy due to legal limits on expenditure spending | x | |||||

| Lack of European and national funds to finance climate-related initiatives | x | x | ||||

| Lack of innovative financing instruments available for private investors | x | x | ||||

| Short-term returns favored over long-term outcomes by private investors | x | x | ||||

| High competition for public funding (EU, national, regional) | x | x | ||||

| Limited financial viability of PPP models | x | |||||

| Limited national government transfers | x | |||||

| Limited private investments for net-zero transition | x | |||||

| Lack of private capital mobilized for municipal fund | x | |||||

| High costs of debt financing | x | |||||

| Earmarked funding opportunities are misaligned with local priorities | x | |||||

| Limited national initiatives and schemes to incentivize private investment | x | |||||

| Unplanned fiscal pressures from climate-related disasters | x |

Fiscal and financial barriers.

Municipal budget constraints stem from various factors. One of the key constraints is that the municipal budget is almost exclusively allocated to mandatory tasks and long-term contracts (e.g., in Barcelona). Whilst climate neutrality is declared a priority in these cities and countries, for example climate action is considered voluntary in Germany. Limited budgets are exacerbated by the lack of fiscal autonomy to raise or introduce new taxes to increase revenues.

Taxes, a key revenue source for municipalities, also serve as important levers to incentivize or disincentivize private investment. However, in most cities, tax rates, credits, and incentives are regulated at the national level, which restricts local governments in two essential ways. Firstly, they are unable to increase local taxation revenue (partly due to behavioral barriers), and secondly, they lack the autonomy to design targeted fiscal incentives to encourage climate conscious behavior and investments. For example, in Pécs, the 2022 Competitive Regions Program introduced by the national government redistributes part of the local business tax revenue, further reducing the city’s income.

A notable and recurring self-observation by cities is the continuous need for European and national funding. Even in The Hague, where finance was not identified as the main barrier, its flagship financing initiative (the HEID holding fund) is heavily reliant on national and European sources. Pécs noted a lack of access to “affordable finance, such as loans and grants,” and Parma cited that high debt servicing costs make certain instruments unaffordable. We observed various financial constraints to mobilizing private finance. These include the absence of fiscal incentives and tailored financial instruments for the private sector; limited financing capacity among households and SMEs, often due to for example “low household purchasing power” in Thessaloniki; or “limited access to capital markets” in the Hague; or higher costs of loan finance in Münster, if the municipality’s ownership share falls.

Table 4 shows that recurring institutional and capacity-related barriers were the lack of internal knowledge, skills, and, or practical experience to understand, structure, and implement innovative instruments. These issues were emphasized across all cities regardless of a city’s size or geographic context.

Table 4

| Barriers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of knowledge, capacity and experience with IFIs | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Labour shortages | x | x | ||||

| Lack of and limited access to data and information on climate risks, benefits, and opportunities | x | x | ||||

| Lack of capacity building and training opportunities in the municipality | x | |||||

| Lack of pipeline of bankable projects | x | x | ||||

| Organisational silos and fragmented coordination across stakeholders | x | x | ||||

| Lack of institutional tools integrating climate consideration into financial planning and allocation | x | x | ||||

| Lack of standardized measurement frameworks | x | |||||

| Lack of understanding private investment needs by municipal staff | x | |||||

| Lack of coordinated governance at higher levels of government | x | |||||

| Misalignment between strategic and financial planning | x | |||||

| Difficulty of demonstrating the economic and financial attractiveness of climate-related projects | x |

Institutional and capacity barriers.

Across all cities, institutional capacity gaps emerged as one of the most pervasive barriers to deploying innovative financing instruments. Parma, Pécs, and Thessaloniki all reported limited internal expertise to design, structure, and manage non-traditional financial mechanisms and the absence of prior experience with IFIs. Municipal staff were often unfamiliar with IFIs, lacked training opportunities, and had little experience engaging with private actors or negotiating co-financing arrangements.

In Pécs and Thessaloniki, chronic understaffing—driven by austerity and the outmigration of skilled workers—further reduced the bandwidth needed to explore IFIs, as most administrative capacity was absorbed by competing demands tied to traditional national and EU grant procedures.

Even better-resourced cities require institutional learning. In The Hague, municipal departments initially struggled to understand the structure of the HEID fund, particularly the separation between city-level investment strategy and project-level decisions made by an external fund operator, necessitating dedicated training and internal coordination. Both The Hague and Thessaloniki also noted difficulties in developing bankable project pipelines that meet investor requirements, while data gaps on climate risks and project impacts further weakened evidence-based planning. Similar challenges were reflected in Barcelona, which faced complications meeting KPI and reporting requirements for its green loan. While Münster indicated structural challenges in linking climate action planning with municipal budgeting.

Across all cases, the lack of tools to integrate climate priorities into budgeting and financial planning, insufficient understanding of investor needs, and fragmented coordination across municipal departments (indicated in Münster and Parma) collectively slow down financial innovation and hinder the preparation of projects capable of leveraging IFIs at scale.

As Table 5 illustrates, cities face significant legal and regulatory obstacles that directly shape their capacity to mobilize finance through IFIs. Most constraints stem from national frameworks, which determine whether municipalities can borrow, raise revenues, set up local incentives, or collaborate with private actors. Crucially, legal and regulatory barriers are closely interlinked with financial and fiscal constraints in municipalities, effectively restricting the range of instruments cities can deploy.

Table 5

| Barriers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal limitations to municipal borrowing | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| High bureaucracy and complex administrative steps to access European funding | x | x | x | |||

| Complex and inconsistent national regulations and policies | x | x | ||||

| National regulations limit citizen-led energy initiatives and investments | x | |||||

| Scattered ownership of residential buildings and flats | x | x | ||||

| Institutional uncertainty and lack of legal clarity | x | x | ||||

| Regulatory conservatism from higher-level government | x | |||||

| Municipality imposed regulatory constraints | x | |||||

| Legal limitations to issuing bonds | x |

Legal and regulatory barriers.

Across all cases, borrowing restrictions were the most pervasive barrier. National debt ceilings limit municipal access to green bonds, and in some countries (e.g., Hungary) prohibit certain instruments unless the national government approves them. Further limitations can be observed in the Netherlands, where the Fido Act requires high creditworthiness of the instruments and counterparties, besides strict borrowing limits. Even fiscally strong cities such as Barcelona are prevented from borrowing due to national fiscal rules and their own conservative internal policies, which further limit spending flexibility.

Cities also pointed to complex and unstable regulatory environments, especially concerning procurement and energy regulations, which create uncertainty, increase transaction costs, and deter private investment. Southern and Central European cities additionally faced high administrative burden, inconsistent national regulations, and restrictive rules on certain initiatives that all hinder private investment: Parma highlighted constantly changing procurement rules; Thessaloniki stressed that legal instability hinders investor confidence; and Pécs noted that evolving rules for citizen- or community-led energy initiatives limit collaboration with households and SMEs.

Institutional ambiguity and lack of legal clarity emerged as further constraints. Barcelona reported an unclear division of responsibilities between national and municipal authorities, especially for newer financial tools, while Thessaloniki struggled to interpret legal requirements for green bond issuance due to limited internal capacity.

Finally, some barriers stem not from national legislation but from embedded governance structures, such as the fragmented ownership of residential buildings in Parma and Pécs, which complicates collective decision-making for retrofitting projects. While not a direct barrier to innovative finance per se, high levels of bureaucracy and administrative complexity, especially in accessing EU funds, were reported to drain municipal capacities and slowing down progress toward exploring more innovative financial solutions.

Political and macroeconomic factors can further constrain cities’ ability to mobilize private finance (Table 6). Several of these challenges are outside the direct control of municipalities. Cities reported that the short-term nature of political cycles undermines continuity, while political fragmentation in Barcelona’s council delays budget approvals and politicizes investment choices. Pécs similarly noted that immediate political pressures often sideline long-term climate priorities with deferred returns and less tangible benefits. The Hague highlighted how delays in the adoption of the Collective Heating Act (Wet Collectieve Warmte) eroded investor confidence deterring private investment.

Table 6

| Barriers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic uncertainty and volatile financial markets limit access to finance | x | x | x | x | ||

| Short-term policy cycles hinder long-term planning and investment | x | x | x | |||

| Politicized investment decisions | x | |||||

| Socio-economic inequalities lead to unequal distribution of resources | x | |||||

| Limited municipal revenue base due to economic constraints and demographic decline | x | |||||

| Limited access to European Cohesion funds | x |

Political and macroeconomic barriers.

Macroeconomic shocks, including inflation, supply chain disruptions and rising interest rates linked to the pandemic and geopolitical tensions, affected all cities, for example Parma experienced cost surges that delayed or cancelled photovoltaic and agri-voltaic projects. Economic volatility and unstable financial markets limit affordable access to credit and investor confidence—both Parma and Pécs reported reduced access to affordable loans. Where local revenue bases are structurally weak, as in Pécs due to economic decline and outmigration, these shocks further restrict fiscal space and co-financing capacity. Economic constraints in the country also lead to the phase-out of national funding schemes, such as the Growth Loan Program and housing renovation support, leaving a gap that neither the city nor the private sector can readily fill. Thessaloniki also noted that socio-economic inequalities complicate the equitable allocation of climate investments.

Political decisions at higher government levels further constrain municipal financing. Pécs faces restricted access to EU Cohesion Funds due to Rule of Law procedure against the national government, which directly reduces public funds to catalyze private finance.

Cities face several infrastructure and technology-related constraints that limit the bankability of projects and the uptake of IFIs (Table 7).

Table 7

| Barriers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure constraints: aging and capacities | x | x | x | |||

| Lack of capacity and expertise in private sector to implement projects | x | x | x | x | ||

| High upfront costs of low-carbon technologies | x | x | x | |||

| Market barriers to low-carbon technologies | x | x | ||||

| Higher risks associated with new technologies | x | x | ||||

| Lack of market readiness for innovative technologies | x |

Technological and market barriers.

High upfront costs and long payback periods remain major barriers, Barcelona noted that long payback periods deter private investors, while Thessaloniki highlighted technological uncertainty and limited reliability, which heighten investment risk. Investors may be wary of funding solutions that are new to the market or lack a proven track record, particularly when regulatory frameworks or performance standards are not fully developed. Under such conditions, instruments like green bonds or PPPs become less attractive due to uncertain returns.

Infrastructure bottlenecks are prevalent across cities. Ageing grids, insufficient energy storage, and poor-quality building stock restrict the deployment of new technologies (e.g., connect decentralized systems), narrowing opportunities to build investment pipelines. Capacity gaps in the private sector also deteriorates investor confidence: in The Hague supplier shortages and long procurement times meant that only a small share of the city’s waste truck fleet could be electrified over 2 years; while parallel implementation of multiple major infrastructure projects in Münster caused capacity bottlenecks.

Finally, market immaturity and distorted price signals (e.g., fossil fuel subsidies, dominance of legacy energy industries, solutions with lack of track record, as noted by The Hague and Thessaloniki) inhibit the development of competitive low-carbon markets. These factors collectively raise costs, delay projects, and weaken investor confidence.

4.3 Enablers identified across cities

We observed a range of enablers that cities employ or refer to while addressing the key barriers to facilitate the deployment of IFIs (Table 8), demonstrating that progress is possible under structural constraints.

Table 8

| Enablers identified | Barcelona | Münster | Parma | Pécs | The Hague | Thessaloniki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral and cultural | ||||||

| Motivated municipal staff driving financial innovation and engaging in capacity-building | x | x | x | |||

| Collaboration with the community and private sector | x | x | x | |||

| Fiscal and financial | ||||||

| Strong creditworthiness and financial reputation | x | x | x | |||

| Availability of public funding (OSR, national, European) that can scale private finance | x | x | ||||

| Institutional and capacity | ||||||

| Previous experience in implementing some IFIs | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Cross-exchanges and learning from other municipalities | x | x | x | x | ||

| EU-funded projects advancing net-zero transition and IFI deployment | x | x | x | x | ||

| Access to European technical assistance and capacity-building support | x | x | x | |||

| Support and capacity-building offered through the NZC programme | x | x | x | |||

| Support from local institutions (development agencies, universities, private companies and financial intermediaries) | x | x | x | |||

| Establishment of a cross-functional department to drive green projects | x | x | ||||

| Good multilevel collaboration to access national and European funds | x | x | ||||

| Capacity building and HR expansion planned | x | x | ||||

| Organizational learning and capacities built to issue further bonds more efficiently | x | |||||

| Institutional tools strengthening financial planning and fund allocation | x | |||||

| Integration of climate considerations into municipal decision making | x | |||||

| Successful application of IFI to scale finance | x | |||||

| Internalizing private sector experience and capacities | x | |||||

| Safeguards in place to ensure alignment of municipal goals with private investments | x | |||||

| Quantifying data and identifying opportunities to build the project pipeline | x | |||||

| Legal and regulatory | ||||||

| Enabling national legislation driving local private finance | x | x | ||||

| Political and macroeconomic | ||||||

| Strong political support from municipal leadership for sustainability | x | x | ||||

Enablers identified in analyzed cities, across key categories.

A frequently cited enabler relates to behavioral factors. Several cities emphasized the role of motivated municipal staff, who actively drive financial innovation, even in settings with limited capacity or experience. This personal drive helps overcome institutional inertia and raise awareness, unlocking progress. Commitment was also linked to more effective community engagement and awareness-raising, particularly in sectors like building retrofits where behavioral barriers strongly inhibit private investment.

On the fiscal front, cities with strong credit ratings and sound financial management (e.g., The Hague, Münster, Barcelona) can access borrowing on favorable terms, improving their ability to leverage debt for climate investment. Strategic use of public funds and assets (e.g., sale proceeds from selling The Hague’s utility company or equity investment through Münster’s public utility) can effectively leverage private finance through innovative mechanisms. EU-funded programmes provide predictable, multi-year support that helps cities plan investments despite external shocks or politically induced uncertainty at the national level.

Cities noted that continuous training, peer learning, and EU-funded technical assistance (e.g., EIB advisory support, NetZeroCities) are essential for strengthening institutional capacities and skills, reducing uncertainty around IFIs, and enabling “learning-by-doing.” Cities that had prior experience with IFIs—such as EPCs in Parma and Pécs or green bonds in Münster—often planned to scale or replicate these models, indicating a reinforcing cycle of institutional knowledge, confidence, and implementation capacity. Platforms such as ClimaNet in Greece further support institutional development through structured cross-city exchange. Some cities are also institutionalizing this progress by creating cross-functional climate offices (e.g., Parma, Pécs), improving coordination, integrating climate priorities into financial planning, and protecting continuity across political cycles. Partnerships with financial institutions, research bodies, and service providers—such as Parma’s work with Credit Agricole or Pécs’ Climate Platform—help tailor financial products to local needs, strengthen investor confidence, and build bankable project pipelines.

Despite widespread barriers, some enabling national legislation can act as key enablers. Examples include the Energy Efficiency Obligation Scheme mandating private-sector investments by utilities in Hungary, or the regulatory provisions allowing philanthropic donations in Thessaloniki.

5 Discussion

This paper provides one of the first exploratory comparative assessments of barriers and enablers to the use of IFIs for urban climate action drawing directly from Mission Cities’ investment plans and city interviews. Focusing on six cities, Barcelona, Münster, Parma, Pécs, The Hague, and Thessaloniki, we identified recurring patterns of IFI uptake, a set of structural and inter-dependent constraints, and enabling conditions that explain why many instruments remain conceptual or small-scale despite widespread interest.

5.1 Patterns in IFI uptake and plans

Across the six cities, there is clear conceptual interest in IFIs, but implementation is uneven in both depth and maturity. As shown in Section 5.1, cities tend to rely on a limited set of “workhorse” instruments (Nurse and Fulton, 2017; CCFLA, 2024), primarily PPPs (including EPCs), concessional loans and, in some cases, municipal funds and green loans, while more complex tools such as green bonds and tax-based mechanisms remain largely experimental (Ulpiani et al., 2023; Casady et al., 2024). Cities therefore do not lack ideas; rather, they selectively deepen a small number of instruments they already understand and can manage administratively.

A central pattern is the continued dominance of municipal budgets (own-source revenues plus transfers) and European funds as the backbone of climate investment. While such funding is catalytic, its dominance points to a structural gap: cities are expected to deliver ambitious net-zero goals, yet their fiscal autonomy and borrowing space remain constrained by national rules and conservative internal policies (Bracking and Leffel, 2021; Casady et al., 2024; Averchenkova et al., 2021; Correa do Lago et al., 2023). This reliance on grants and transfers, also noted in wider analyses of European urban climate finance, raises questions about how far municipalities can diversify into IFIs in the absence of deeper governance reforms (Casady et al., 2024; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023).

The uneven use of commercial debt further illustrates how governance conditions shape instrument choice. Some cities (e.g., The Hague, Münster) can access capital markets on favorable terms due to strong credit profiles and stable national frameworks, whereas others face high borrowing costs, strict debt ceilings or legal restrictions on bond issuance (Bracking and Leffel, 2021; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023). In the latter contexts, IFIs are framed as desirable but remain conceptually “on the shelf,” as cities fall back on grants and soft loans to avoid perceived financial and political risks (Ulpiani et al., 2023; Casady et al., 2024).

Previous experience emerges as a strong predictor of future IFI plans. Cities that have piloted EPCs, PPPs, or green bonds tend to signal an intention to replicate and scale these instruments, even where initial experiences were mixed. This reflects a positive path dependency (David, 1985; Arthur, 1994; Seto et al., 2016): administrative systems, risk norms and political narratives become tailored to particular instruments, making it easier to repeat an established model than to adopt new ones. Importantly, our cases suggest that governance quality around a few well-designed instruments—supported by clear rules, competent intermediaries, and political backing—may be more important than the sheer diversity of tools available (Heinrichs et al., 2013; Castán Broto, 2017). Cities such as The Hague and Münster have mobilized substantial volumes through a relatively narrow set of mechanisms, whereas cities with a wide conceptual menu of IFIs still struggle to move beyond pilots.

5.2 Barriers: key takeaways and interdependencies

Our findings support the wider implications of sustainability transition governance (EEA, 2019) and confirm earlier studies that identify fiscal, legal, and institutional barriers as central constraints to municipal climate finance (Alexander et al., 2019; Nurse and Fulton, 2017; OECD, 2022a,b), but add granularity on how these barriers interact in the specific context of IFIs. The six categories identified in Section 3—fiscal and financial, legal and regulatory, institutional and capacity, behavioral and cultural, political and macroeconomic, and technological and market—should be understood as a mutually reinforcing barrier and enabler system rather than separate obstacles and opportunities (EEA, 2019). Next, we first focus on the main identified barriers and in the following sub-section, we highlight the main policy recommendations based on the enablers that the studied cities experienced.

Fiscal and legal constraints form the backbone of this system, as legal and regulatory frameworks define the fiscal space, and the menu of instruments cities can use. National frameworks typically set debt limits, constrain municipal borrowing spending and bond issuance, and centralize control over key taxes and incentives. As the cases of Hungary and the Netherlands illustrate, cities may be prevented from issuing bonds without national approval or must comply with strict prudential rules that narrow the range of acceptable instruments (Averchenkova et al., 2021; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023). At the same time, local budgets are largely pre-committed to mandatory services, leaving little discretionary space for climate investments (Heinrichs et al., 2013; Nurse and Fulton, 2017; OECD, 2022a,b). Larger cities such as Barcelona still face a lack of autonomy, despite having more financial capacity than smaller cities. This combination undermines the preconditions for many IFIs, which require stable, locally controlled revenue streams (e.g., from taxes, fees or user charges), the ability to design targeted fiscal incentives for private actors, and sufficient balance sheet capacity to take on risk. The result is a persistent dependence on grants and concessional loans: a rational response to the regulatory environment, but one that entrenches limited experimentation with market-based tools (Ulpiani et al., 2023; Casady et al., 2024). Our evidence also cautions against assuming PPPs/PFIs are always financially viable: in Münster, banks are reluctant to extend credit when the municipality’s ownership share in projects fell (as under many PPP structures), and PPP delivery was perceived to entail higher operating costs, concerns that are consistent with the wider evidence on PPP/PFI cost and affordability risks (Bing et al., 2005; Hellowell and Pollock, 2007).

Institutional and capacity barriers reinforce this equilibrium. Municipal teams are generally well-versed in applying for and managing grants but have much less experience in structuring risk-sharing mechanisms, negotiating with private investors, or managing performance-based contracts (Bulkeley et al., 2013; Frantzeskaki et al., 2018; Ulpiani et al., 2023). Chronic understaffing, especially in smaller and fiscally weaker cities, exacerbated by austerity-driven staffing freezes or brain drain, means that most administrative capacity is absorbed by routine tasks and traditional EU/national programmes, crowding out the time and skills needed to design and test IFIs. We found that even larger, more experienced cities also had a learning curve (Wolfram, 2016; Frantzeskaki et al., 2018) with IFIs as evidenced by the introduction of HEID or green bonds, requiring additional resources to train the staff and decision makers. Where dedicated organizations such as municipal funds, utilities or dedicated climate finance units exist, they help translate political priorities into bankable projects and standardized processes (Castán Broto and Sudmant, 2022; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023). Where such intermediaries are weak or absent, each department must negotiate separately with investors and navigate complex regulations, raising transaction costs and perceived risk (Casady et al., 2024; NetZeroCities/JRC, 2023; Bracking and Leffel, 2021).

Behavioral and cultural factors further amplify these constraints. Conservative risk cultures and resistance to change make officials cautious about instruments perceived as complex, opaque or politically sensitive, leading to organizational inertia (Bracking and Leffel, 2021; Ulpiani et al., 2023). Negative past experiences with PPPs, ideological skepticism towards private sector involvement, and low public awareness of climate benefits (e.g., in Pécs and Parma) all contribute to a preference for familiar tools as we also observed in earlier studies (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2013; Bracking and Leffel, 2021). Interestingly, several cities still plan to use PPPs despite earlier negative experiences (e.g., Barcelona, Parma), suggesting a constrained choice set: they may lack the mandate and the capacity to design alternative solutions, so they return to known but imperfect templates rather than experimenting with entirely new instruments.

Political and macroeconomic conditions shape the overall risk environment in which municipalities operate. Short electoral cycles and fragmented councils (e.g., in Barcelona) can delay budget approvals and discourage investments whose payoffs fall beyond a single term (Montfort et al., 2025). National-level political decisions, such as rule-of-law disputes in Hungary, limiting access to EU funds, directly affect cities’ ability to co-financing projects. At the same time we identified that inflation, supply chain disruptions, and rising interest rates have raised project costs and tightened credit conditions, making both public and private actors more conservative due to real or perceived risks, and less able to invest across the studied cities (Carter and Boukerche, 2020; Casady et al., 2024). Legal instability in procurement and energy regulations adds another layer of uncertainty for investors, increasing the governance risk premium attached to municipal projects (Bracking and Leffel, 2021; UNECE, 2023).

Technological and market barriers interact closely with these governance risks. High upfront costs, long payback periods and immature markets for certain low-carbon technologies reduce the bankability of projects, particularly in contexts of low household purchasing power or socio-economic inequality (Ohene et al., 2022; Huovila et al., 2022). This is especially visible for building retrofits, where fragmented ownership, weak homeowner associations, and limited capacity among local suppliers combine to make projects complex and slow, undermining scaling of IFIs that rely on technical readiness, even when instruments like EPCs or green bonds exist (Heinrichs et al., 2013; Castán Broto and Sudmant, 2022).

Taken together, these interdependencies suggest that limited uptake of IFIs is not primarily due to a lack of innovative ideas or instruments. Rather, it reflects a configuration of multilevel governance arrangements—fiscal rules, regulatory frameworks, institutional capacities, political incentives and macroeconomic and social conditions—that makes grant-based, incremental financing the path of least resistance. Overcoming this configuration requires coordinated reforms across several dimensions, rather than isolated interventions to individual instruments.

5.3 Overcoming barriers: local practices and policy recommendations