Abstract

Despite expanded municipal climate commitments, many cities continue to struggle with translating carbon-neutrality, resilience, and equity goals into coordinated implementation. Persistent governance fragmentation, institutional inertia, and limited technical capacity undermine the development of integsrated climate strategies. This article evaluates the Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) methodology—developed within the UCCRN network—as a structured, multi-scalar approach to bridge these gaps. UDCWs couple interoperable Simulation and Facilitation toolkits to support evidence-based, participatory co-design processes. We draw on eight case studies across Europe, Africa, and South America to examine how UDCWs operate within diverse governance and planning contexts. Findings show that the UDCW framework supports climate-responsive design by spatializing community needs, quantifying adaptation and mitigation benefits, and enabling interdepartmental collaboration. The methodology reveals systemic barriers, including siloed planning, policy misalignment, and the absence of procedural mechanisms to enforce cooperation. At the same time, it provides context-sensitive tools that support embed socio-spatial and climate-justice considerations into decision-making. Results indicate that upscaling climate action requires more than technical solutions: it demands adaptive governance cultures that align scientific evidence, community aspirations, and enforceable policy instruments. UDCWs experience offer a replicable pathway to unlock stalled transitions and institutionalize just, climate-resilient transformations, providing a practical response to the multilevel barriers that continue to undermine sustainable urban climate governance.

1 Introduction

Urban areas are increasingly exposed to compounding and intensifying risks driven by climate change, particularly in the form of flooding, heat stress, and pressure on critical infrastructure. Effectively addressing these challenges requires targeted adaptation strategies, improved risk assessment, and inclusive urban planning approaches that prioritize the protection of vulnerable populations and enhance city-wide resilience through transformative tools and actions (Ye et al., 2021; Blokus-Dziula and Dziula, 2024; Nowak, 2023).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), introduces the concept of climate-resilient development. This framework advocates for integrated actions that simultaneously advance carbon neutrality, climate adaptation, and the well-being of both human and non-human life (Singh and Chudasama, 2021; Schipper et al., 2022). Importantly, it shifts focus from incremental improvements to transformative change in the ways cities are planned, regenerated, and retrofitted. Achieving this requires context-sensitive, coordinated actions that bridge climate and development objectives, address equity considerations, and foster long-term sustainability (Abel et al., 2021; Otto et al., 2021).

Climate-resilient development can follow multiple pathways, including targeted climate action, social learning, policy mainstreaming, and systemic transformation. Effective planning in this context necessitates flexibility, anticipatory governance, and continuous learning (Abel et al., 2021; Stringer and Favretto, 2024; Glavovic et al., 2020). It also demands confronting trade-offs and actively avoiding the reinforcement of existing inequalities, employing a justice- and equity-oriented lens. Ensuring inclusive participation and participatory governance is especially critical in the Global South and other vulnerable geographies (Barkai et al., 2023; Rodríguez and Carril, 2024; Stringer and Favretto, 2024).

Operationalizing climate-resilient development within urban design practices requires the deployment of innovative, evidence-based methods that can synthesize complex, multi-scalar information—including localized climate projections, social vulnerability data, ecosystem services, and emissions inventories. These methods must not only inform technical interventions but also enable inclusive decision-making, long-term scenario planning, and equitable outcomes (Frantzeskaki et al., 2019).

Transformative approaches to resilience go beyond surface-level responses, aiming instead to address the root causes of risk by engaging with the underlying drivers of vulnerability. This includes critical attention to questions of power, justice, and agency (Pelling et al., 2015; Patterson et al., 2018; Wolfram, 2016; Forsyth, 2018; Parsons et al., 2025). Such approaches aim to overcome structural drivers of vulnerability and assess the long-term impacts and scale of transformation, particularly in relation to engagement and governance mechanisms (Eriksen et al., 2021).

In the realm of spatial planning, transformational change is closely tied to principles of equity and justice. This includes the implementation of distributive, recognitional, procedural, and restorative justice within urban design projects and regeneration practices aimed at climate adaptation and mitigation (Shi et al., 2016). These actions span different spatial scales—from metropolitan regions to neighborhoods—and benefit from integrated top-down and bottom-up governance processes.

Emerging concepts in urban studies, such as the “just urban transition” (JUT) (Hughes and Hoffmann, 2020) and “just climate adaptation” (Castan Broto, 2021), capture this shift toward a justice-oriented and transformative climate agenda. These frameworks emphasize the transformative capacity embedded in urban systems and the dynamic interactions among stakeholders, places, and institutional processes (Shahani et al., 2022; Torrens et al., 2021; Wolfram et al., 2019a;b; Wolfram, 2016; Castán Broto et al., 2019). Spatial transformation should thus be understood as both an outcome and a driver of urban stakeholders’ agency, spatial interventions, and institutional configurations (Christmann et al., 2020; Wolfram et al., 2019b). These dimensions must be considered in spatial planning to foster socially embedded, place-based, and cross-scale solutions supported by social learning processes (Sharpe, 2021).

In this context, planning and design practices must transcend fragmented and sectoral approaches that separate environmental and social goals. Instead, they must adopt integrative methodologies that support long-term visioning, foster inclusive dialogue among diverse actors and participatory methods, and enable the iterative testing of innovative solutions (Parson et al., 2025). Climate-resilient urban design must also critically address and challenge business-as-usual models that tend to prioritize market logic over community needs, particularly in socially and spatially vulnerable contexts (Robin and Castan Broto, 2021).

Achieving a just urban transition entails reconfiguring physical infrastructure and both public and private spaces to meet the increasing demands of fair climate adaptation and mitigation, particularly in response to intensifying extreme weather events such as flooding and heatwaves who severely threat the most vulnerable groups, already subject of exclusion, segregation and marginalization (Visconti, 2025). This process requires science-based data that quantify the impacts of climate threats on infrastructure and vulnerable populations, while also accounting for microclimatic conditions affecting public health, energy consumption, and urban quality (Santamouris, 2020). Equally critical is the recognition of co-benefits—economic, environmental, and social—as well as the integration of co-produced knowledge, including tacit and experiential insights from a wide spectrum of stakeholders and communities involved in spatial planning and decision-making (Castan Broto, 2021; Wolfram et al., 2019a). Tools that facilitate the integration of different types of knowledge are essential to inform risk assessments and to tailor design solutions capable of transforming the urban spaces according to the changing climate conditions while delivering essential services, urban functions and value propositions (Raven et al., 2025b).

This paper explores the evolving landscape of evidence-based tools and methods that support climate-resilient urban design, focusing on the methodology and findings of the Urban Design Climate Workshops (UDCWs) developed by the Urban Climate Change Research Network (UCCRN). The study examines the operationalization of climate data and performance indicators through two specific toolkits (UDCW simulation and UDCW facilitation) to inform sustainable urban regeneration and retrofitting strategies, while ensuring inclusiveness, equity, and long-term transformative impact.

Evidence-based design, traditionally rooted in architecture and healthcare, offers a systematic framework for integrating empirical data, performance metrics, and stakeholder input into the design process (Shi, 2024; Quiñones-Gómez et al., 2025). When applied to climate resilience, evidence-based design enhances decision-making by aligning interventions with the best available scientific knowledge, modeling tools, and observed outcomes (Peavey and Vander Wyst, 2017). Yet, despite the growing availability of climate data and adaptation strategies, a persistent gap remains between research and practice (Raven et al., 2025a). Many practitioners still lack access to, or the ability to interpret, tools that can translate complex climate projections into actionable design guidance. In this context Dhar and Khirfan, 2017 identifies four main gaps that pertain to: the lack of interdisciplinary linkages, the absence of knowledge transfer, the presence of scale conflict, and the dearth of participatory research methods. A growing consensus is in advocating the advancement of participatory and collaborative action research to meet the multifaceted challenges of climate change (Dhar and Khirfan, 2017, Bremer and Meisch, 2017, Parson et al., 2025).

The Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) represents a key methodological response to these challenges. Conceived as an applied, capacity-building process, the UDCW brings together urban designers, climate scientists, planners, policymakers, students, and local stakeholders in a collaborative environment to co-develop transformative climate actions for specific urban districts. Through scenario modelling, participants and experts assess projected climate impacts across different development, zoning and land use alternatives, while community-based climate-sensitive prototyping helps identify spatial strategies that integrate both mitigation, adaptation and livability objectives.

The UDCW was first formalized in the Urban Planning and Urban Design chapter of the Second Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3.2) (Raven et al., 2018), and further advanced in the forthcoming Third Assessment Report (ARC3.3) (Raven et al., 2025a). ARC3.3 expands on this foundation by presenting applied research, pilot projects, and tested models that demonstrate how urban systems and the built environment can be reimagined to support integrated mitigation and adaptation strategies and local community needs. Grounded in urban climate science and community engagement, from 2015 the UDCW methodology has been tested through case studies in cities on a global scale such as Napoli, Paris, Durban, and New York, within several research and institutional initiatives.

Compared to other workshop-based approaches which primarily focus on collaborative design processes at the district scale, the UDCW is distinctive in its multi-scalar scope and in the systematic integration of a Simulation Toolkit with participatory processes. This combination allows not only for the co-design of local adaptation measures but also for the translation of stakeholder priorities into quantitative scenarios to design and simulate, thereby linking community engagement with city-wide climate and energy planning.

Through the analysis of UDCW toolkits implemented across eight cities in different regional contexts, this paper offers a critical and empirical contribution to understanding and addressing the implementation gaps that hinder urban climate action at the city level.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

-

Firstly, the two toolkits, UDCW Simulation and Facilitation, are described and defined in terms of their main functionalities and potentialities (Section 2).

-

Secondly, a methodological focus on UDCW as a learning environment and co-production process is developed to explicate the methodology and its application (Section 3).

-

Thirdly, eight UDCW experiences at global and regional scales (Europe, Africa and South America) are presented through case studies, drawing on the main results of the UDCW implementation in specific real contexts (Section 4).

-

Fourthly, the main findings of the cases are discussed, framing the processual analysis of the results (Section 5).

-

Finally, conclusions are outlined about the potential upscaling of the UDCW approach and its practice and policy implications (Section 6).

2 UDCW toolkits

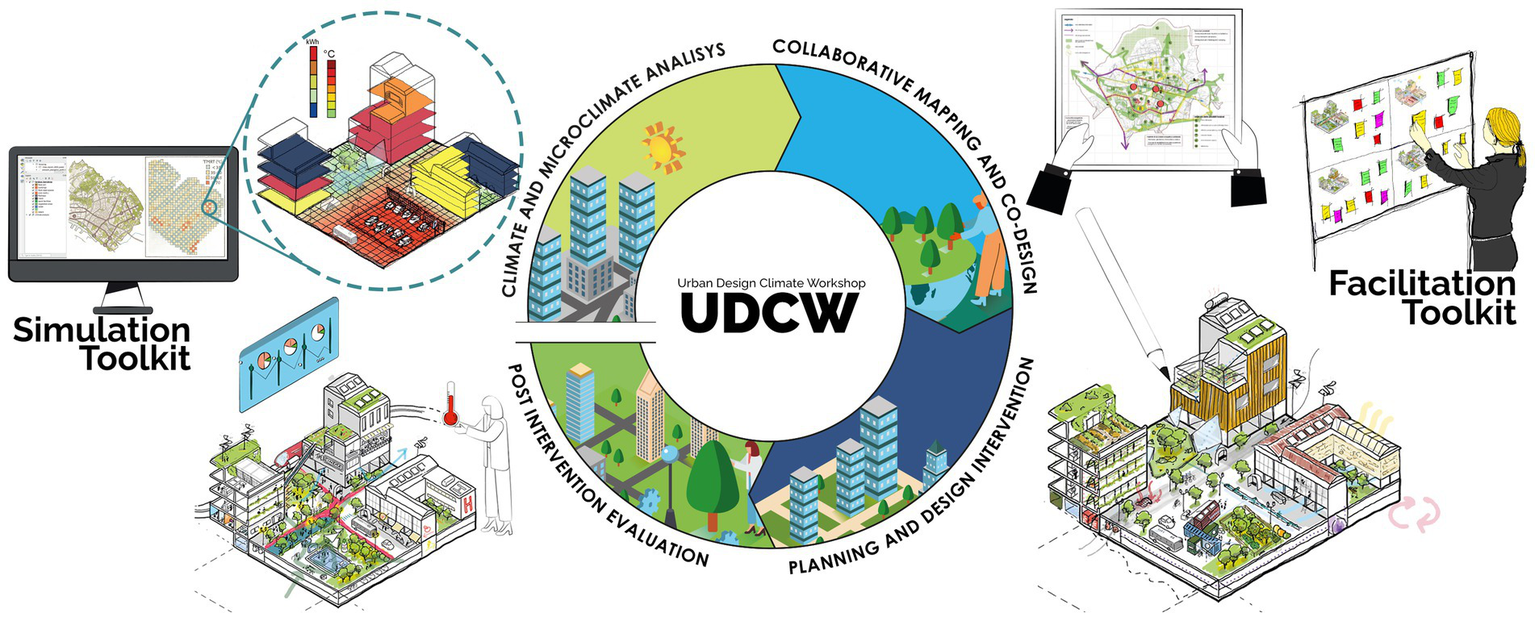

The UDCW as a broader methodology aimed at fostering climate-responsive urban development, is based on a suite of evidence-based, user-friendly tools to support multi-scale urban planning and design. Central to this approach are the UDCW Simulation Toolkit and the UDCW Facilitation Toolkit, developed through applied and action-oriented research (Raven et al., 2025a). These tools are designed to assist city technical departments, urban planners, and design practitioners in aligning climate mitigation and adaptation goals with environmental justice and community priorities. The UDCW methodology adopts a four-step iterative process that enables spatialized, quantitative assessment of co-designed urban scenarios, incorporating downscaled climate projections alongside socio-economic and environmental co-benefits (Figure 1). Operating across spatial scales—from city-wide strategies to neighborhood-scale interventions—the toolkits provide integrated analyses that connect urban morphology, land use, and climate data with qualitative insights from stakeholder engagement. This multi-scalar and integrated framework - defined by the combination of Simulation and Facilitation toolkits - provides a structured way to connect urban morphology, land use, and climate data with qualitative insights from stakeholder engagement, ensuring that planning and design processes are both informed by data and community insights.

Figure 1

UDCW methodology.

2.1 UDCW simulation toolkit

The increasing reliance on computational tools in the built environment professions has been accelerated by the advances in Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). These technologies enable the processing of large datasets (e.g., climate projections, urban morphology, land uses) and facilitate simulations of complex phenomena (Kumar and Bassill, 2024). Simulation thus emerges as a foundational scientific tool, providing, with a certain level of abstraction, a description of physical, environmental, or socio-economic processes, and their evolution over time.

In the field of architecture and urban design, professionals and researchers increasingly rely on computational simulation tools in order to optimize design solutions at different scales (Chiesa et al., 2023; Mazzetto et al., 2024). This approach involves using calculation results to inform the model directly, rather than analyzing the performance of a given design solution through a separate tool and modifying it accordingly (Nocerino and Leone, 2024).

In this context, the UDCW Simulation Toolkit has been developed to streamline and enhance planning and design decisions by integrating key performance indicators related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. As a core component of the UDCW methodology, the Toolkit supports interdisciplinary collaboration among planners, architects, climate scientists, and local communities. It aligns data-driven climate analysis with participatory design practices, fostering informed and resilient urban transformations. One of the main objectives of the UDCW simulation toolkit lies in overcoming the lack of user-friendly tools for evaluating the effect of different urban design decisions (Jänicke et al., 2021).

From a methodological standpoint, simulation tools embedded in the UDCW approach are not only representational but decisional: they guide the generation, comparison, and evaluation of design alternatives based on their quantified simulated performances against a series of key climate, environmental, and socio-economic indicators.

The Simulation Toolkit includes a suite of interoperable instruments operating across two principal modelling environments:

-

GIS-Based Tools for urban-scale analysis (2D and 2.5D geospatial models)

-

Algorithm Aided Design (AAD) tools for neighborhood- and building-scale simulation (3D parametric modelling using Rhinoceros + Grasshopper)

Each environment supports different steps of the UDCW methodology—from preliminary climate mapping to post-intervention assessment—while also enabling comparative evaluation between scenarios: current conditions, business-as-usual development, and climate-resilient alternatives.

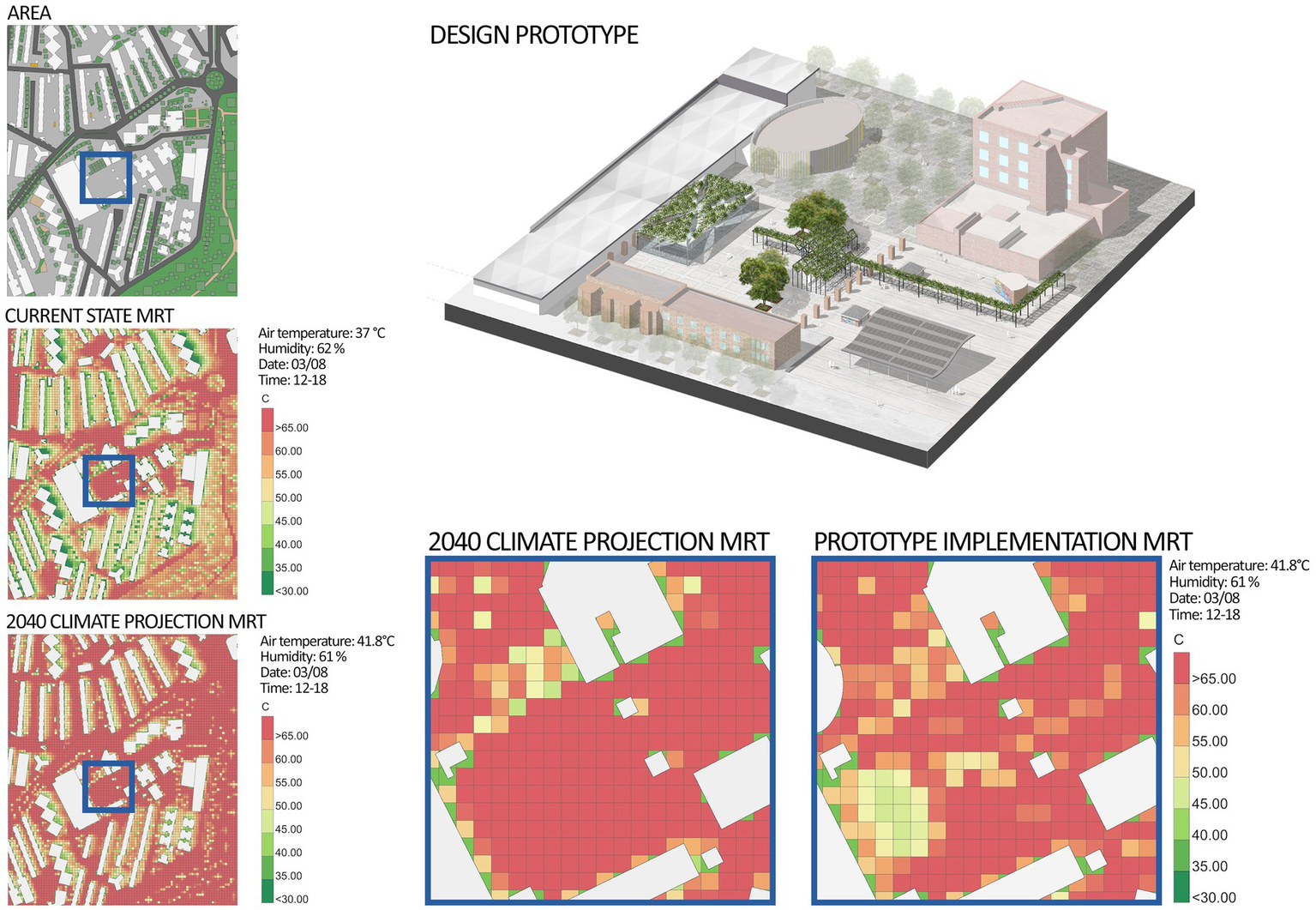

Typical applications of the Simulation Toolkit span three analytical scenarios: baseline analysis under current urban configurations and climate data; Business-as-usual scenarios with minimal adaptation measures; best practice scenarios that embed climate-resilient design strategies (Figure 2).

Figure 2

UDCW simulation toolkit tested in Cornella de Llobregat.

These are evaluated using both quantitative outputs and qualitative overlays derived from stakeholder priorities, enabling a quanti/qualitative evaluation of social (e.g., access to green spaces), economic (e.g., energy savings), and environmental (e.g., CO₂ sequestration) co-benefits.

More specifically, at the urban scale, GIS tools enable hazard and impact mapping of heatwaves and floods. At the neighborhood scale, 3D modelling Algorithm Aided Design (AAD) tools assess design alternatives for buildings and public spaces, considering surface materials, building features shading, and vegetation typologies. This multi-scalar integration supports design-to-impact loops, where iterative simulation refines the design to optimize both mitigation and adaptation outcomes. The list presented below is indicative of key applications; additional indicators (e.g., co-benefits) were included in specific case studies depending on local priorities and data availability.

The toolkit components are organized around simulation typologies and expected outputs:

-

Climate and Microclimate Modelling

-

◦ Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI)

-

◦ Mean Radiant Temperature (TMRT)

-

◦ Predicted Mean Vote (PMV)

-

◦ Apparent and Land Surface Temperature

-

◦ Flood probability index

-

Impact Assessment Tools

-

◦ Heatwave-related hospitalization costs and mortality rates

-

◦ Economic impact of floods (building/road damages)

-

Energy and Carbon Analysis

-

◦ Total and specific energy consumption [kWh/m2]

-

◦ Renewable energy potential [kWh/year]

-

◦ CO₂ storage from green-blue infrastructure [tCO₂/year]

At the urban scale, these indicators are computed using algorithms derived from validated models, such as ENVI-MET (Simon and Bruse, 2020) for thermal simulations and SOLWEIG (Lindberg and Grimmond, 2011) for radiant temperature mapping. The GIS tools apply these models through a PostgreSQL-Python pipeline using 2.5D urban representations, integrating land-use data, elevation, albedo, and sky view factor. At the neighborhood scale, these indicators are computed using algorithms written in Grasshopper for Rhinoceros (McNeel) implementing environmental design and energy modelling plug ins (Ladybug Tools) with custom Python components. While the climate and impact assessment tools emphasize adaptation outcomes, the framework simultaneously integrates mitigation-oriented indicators—such as energy use, renewable energy potential, and CO₂ storage—thereby ensuring a consistent approach across adaptation and mitigation dimensions.

2.2 UDCW facilitation toolkit

The UDCW Facilitation Toolkit comprises a comprehensive set of participatory tools developed to support multi-actor engagement in the co-creation of climate-resilient urban strategies. Targeting both expert stakeholders (e.g., city officials, urban planners, design practitioners) and non-expert actors (e.g., citizens, civil society organizations, the third sector), the toolkit fosters inclusive dialogue and shared learning within climate planning processes. Its core objective is to bridge the gap between scientific and technical knowledge and the everyday experiences and practices of local communities, thus grounding urban adaptation and mitigation strategies in place-based needs and capacities. The toolkit enhances participatory urban governance by enabling the downscaling of climate solutions, supporting the definition of shared priorities, and informing decision-making processes with both qualitative and quantitative insights. It facilitates communication around complex urban climate issues, contextualizes planning and design solutions within specific territorial realities, and aligns adaptation and mitigation strategies with community needs and institutional capacities. Key components of the toolkit include the following set of tools:

-

The Collaborative Mapping enables the co-production of spatial knowledge related to climate risks, urban vulnerabilities, socio-environmental pressures, infrastructure availability, and everyday urban experience. It is implemented through analogic methods (e.g., boards and stickers) or digitally via Participatory Geographic Information Systems (P-GIS), and its outputs are georeferenced and integrated into GIS platforms, serving as inputs to the UDCW Simulation Toolkit.

-

The City Visions and Local Needs Matching supports the identification of regeneration priorities—such as housing, mobility, and access to services—by linking them to thematic urban visions (e.g., Green and Blue City, Circular City, Zero-Carbon City, 15-Minute City, Disaster Resilient City), thereby facilitating a strategic alignment between local needs and climate-resilient futures. It is a visioning and co-design exercise that helps identify local urban regeneration needs and match them with climate-resilient strategies.

-

The Day in the Life visioning exercise elicits narratives of desired urban experiences through the lens of specific user personas (e.g., children, youth, women, elderly), enabling the envisioning of inclusive, user-centered outcomes and helping to surface differentiated needs and vulnerabilities.

-

The 3D Neighborhood Configurator Tool allows technical stakeholders to collaboratively generate spatial design solutions within a three-dimensional modelling environment, integrating simulated climate impacts and enabling visual exploration of mitigation and adaptation co-benefits across physical, social, and environmental dimensions.

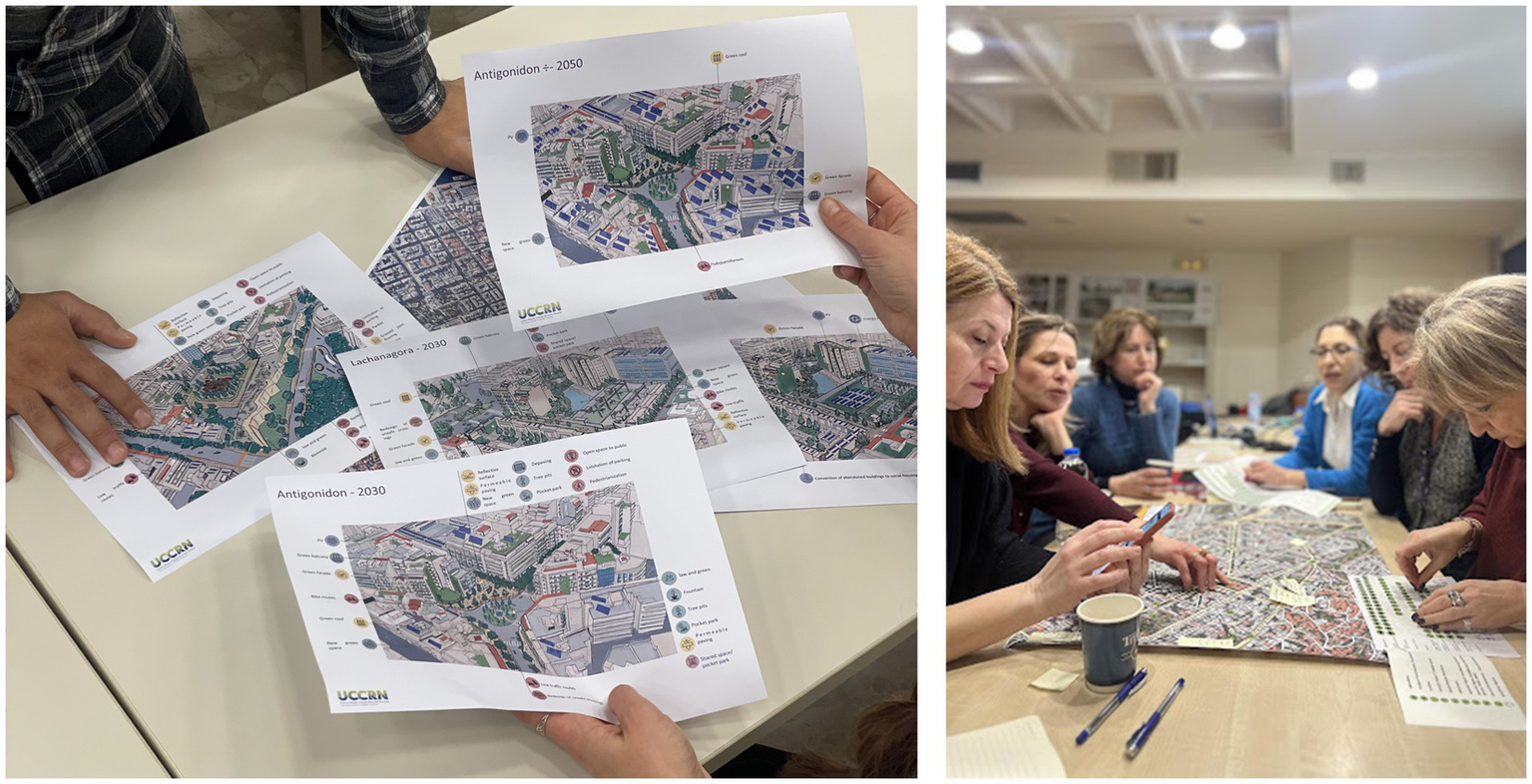

Together, these tools are deployed within participatory workshops to facilitate structured interactions among institutions, experts, and communities, guiding the co-design of urban transformation pathways for mutual learning (Calvo et al., 2022) and co-production of knowledge (Visconti, 2023). In synergy with the UDCW Simulation Toolkit, the facilitation tools enrich quantitative analyses with stakeholder-derived knowledge, thereby contributing to integrated climate risk assessment, performance evaluation, and the development of socially grounded, climate-responsive design strategies. UDCW Facilitation toolkit contribute in conducting workshops activities in which local authorities, stakeholders, students, practitioners and community are engaged to collaboratively envision city transformation pathways, to identify common goals and divergence elements, to evaluate climate benefits and social, economic, and environmental co-benefits of possible technical solutions (Figure 3). The UDCW Facilitation Toolkit is conceived as a flexible instrument, designed to be adapted to various UDCW formats, target audiences, and the specific objectives of engagement activities (Raven et al., 2025a). Its participatory and co-productive dimensions have been progressively refined through action-research practices, incorporating a diverse set of supporting methods to facilitate engagement in the early phases of the UDCW methodology. These include actor mapping, stakeholder priority mapping, climate and neighborhood walks, interviews, and fieldwork activities. The evolution and structuring of the toolkit have also been guided by the intention to explicitly address dimensions of climate justice, as demonstrated through its application in two pilot cases presented in this study—Thessaloniki and Naples (Goncalves et al., 2025; Visconti, 2025).

Figure 3

UDCW facilitation toolkit tested in Thessaloniki.

In alignment with a climate justice framework (Reckien et al., 2025; Visconti, 2025), the toolkit’s components contribute to different dimensions of justice. The Collaborative Mapping tool, which documents daily experiences of climate risks and socio-spatial challenges or opportunities, supports procedural justice by enabling early-stage engagement, distributional justice through the identification of spatially prioritized areas, recognitional justice by rendering socio-environmental inequalities visible, and restorative justice by acknowledging historically embedded losses. The City Visions and Local Needs Matching exercise facilitates the co-identification of urban regeneration needs and their alignment with climate-resilient strategies. This tool fosters procedural justice by involving citizens in strategic planning processes, distributional justice by addressing spatial and service inequities, recognitional justice by surfacing community vulnerabilities, and restorative justice by embedding community-generated solutions into planning frameworks. The Day in the Life visioning exercise employs user profiling (e.g., children, elderly, women) to identify differentiated needs and vulnerabilities. It contributes to procedural justice by ensuring inclusive representation, to distributional justice by addressing intersecting inequalities, to recognitional justice through the construction of shared narratives, and to restorative justice by acknowledging historical exclusion and promoting inclusive urban imaginaries.

3 Methodology

In this section, we introduce the Urban Design Climate Workshops (UDCW) methodology and present eight case studies where it has been implemented. The UDCW outcomes gave been achieved including both qualitative and quantitative methods, such as environmental simulations, performance-based design assessments, participatory data collection and co-design. The dialogue between diverse methods to support climate-responsive design and planning lies at the core of the UDCW methodology, which adopts the “workshop” not merely as a temporal event, but as a sustained, interdisciplinary, and iterative co-creative process. Workshops are conceptualized as experimental environments where architects, urban planners, engineers, designers, and local stakeholders engage collaboratively through hands-on modelling, real-time feedback, and knowledge exchange. This setting fosters integrative thinking and bridges disciplinary boundaries, a concept supported by participatory design literature (Simonsen and Robertson, 2013; Sanders and Stappers, 2008; Smith et al., 2017).

Central to the methodology is the emphasis on rapid prototyping and iterative experimentation. The design process involves context-sensitive modelling, participatory mapping, and the incorporation of local knowledge systems alongside advanced scientific and technical tools (Eliasson, 2000, Warren-Myers et al., 2024, Nanda and Wingler, 2020).

The UDCW approach is also positioned to mediate aesthetic and functional conflicts that often act as barriers to the adoption of climate-adaptive design solutions—challenges extensively noted in climate-responsive architecture and urban planning literature (Brandma et al., 2024; Watson and Adams, 2011). Through facilitated dialogue and co-design exercises, these workshops aim to produce outcomes that are both performative and contextually appropriate.

The methodology follows a multi-phase, multi-scalar sequence that supports design and implementation through a multidisciplinary framework (Figure 1). The four key iterative steps are:

-

Climate and Microclimate Analysis: This phase identifies urban areas vulnerable to climate-related stressors such as extreme heat, flooding. It integrates historical climate data and regional climate projections processed through simulation models. UDCW Simulation Toolkit is applied for site-specific environmental data modeling: GIS platforms support district and city-scale assessments by visualizing urban heat islands and flood-prone zones. At the building/block scale, 3D modelling Algorithm Aided Design (AAD) tools are used to evaluate resilience strategies, incorporating benchmarks from green building, environmental design standards and information useful to generate an Urban Building Energy Model (UBEM) (Reinhart and Davila, 2016). Main outcomes are: preliminary climate and microclimate assessments for current state and future scenarios.

-

Collaborative Mapping and Co-Design: This phase explores the lived experiences of urban environments and integrates the values, needs, and aspirations of local communities. Participants, together with facilitators, articulate spatial knowledge and identify shared as well as divergent design priorities. Participatory engagement methods from the UDCW facilitation toolkit enable diverse stakeholders—residents, local governments, associations, and practitioners—to jointly define urban challenges. Stakeholders are selected on a case-by-case and purpose-driven basis, depending on each project’s framework, commitments, and constraints. In general, stakeholder categories include local authorities, third-sector organizations, local agencies operating at both city and neighborhood scales, local practitioners and researchers, civic associations, activist groups, and inhabitants of the targeted areas. Selection often follows a snowball approach, taking into account participants’ prior involvement in urban regeneration initiatives and their expressed interest in the project. Differences and conflicts among stakeholders are acknowledged as integral to the process. These may stem from contrasting institutional mandates, resource priorities, or community expectations. Facilitators employ structured dialogue and mapping techniques to surface such tensions and turn them into productive discussions that inform co-design outcomes. While participation generally functions as intended—fostering mutual learning, negotiation, and consensus-building—it also reveals the limits of collaboration in contexts characterized by unequal power relations or differing temporal commitments. Nonetheless, these dynamics contribute valuable insights into the complexity of inclusive and conflict-aware urban design processes (Fischer et al., 2013; Manzini, 2015). The main outcomes of this phase include collaborative maps, co-produced narratives, and the spatialization of community-based potential interventions. These outcomes serve both as design tools and as shared reference frameworks that guide subsequent stages of urban development and decision-making.

-

Planning and Design Development: Informed by the previous phases, this step involves critically aligning stakeholder insights with planning instruments and regulatory frameworks. Urban plans and zoning laws provide the spatial and legal context within which context-sensitive design strategies are developed. The use of visual, parametric, and geospatial tools facilitates the exploration of synergies and trade-offs, supporting the creation of adaptable meta-design proposals that address climate change impacts while enhancing urban environmental quality (Rosenzweig et al., 2018). The application of UDCW Simulation Toolkit in this phase is useful to quickly evaluate different design alternatives according to several energy and environmental performance indicators. Outcomes are: masterplans, strategic and thematic analysis, detailing of design solutions, visuals, prototypes.

-

Post-Intervention Evaluation: This concluding phase evaluates the efficacy of the implemented interventions. It applies scenario simulations, performance metrics (e.g., thermal comfort, energy savings), and feedback loops involving community stakeholders to assess both technical outcomes and social acceptance. The objective is to iteratively refine solutions and provide evidence-based validation of their effectiveness in real-world contexts (Zinzi and Agnoli, 2012; Brown et al., 2009). In this phase, the UDCW Simulation Toolkit is used to evaluate the effects of the final solutions on urban microclimate both at the neighborhood and at the urban scale. UDCW Facilitation toolkit can also be applied tailoring the tools to gather specific input from stakeholders about the proposed solutions or main challenges to match climate-proof measures and urban fabric constrains.

The UDCW methodology is implemented with support from UCCRN experts and local actors. It builds an intervention model that links scientific modelling with community-based planning, using computational tools to monitor key indicators—such as temperature regulation, solar radiation, and stormwater management—critical to building and open-space performance in a changing climate.

The UDCW methodology is adaptable to different contexts through a range of formats, each tailored to specific objectives, durations, and levels of engagement (Table 1). Knowledge Exchange workshops are short-format events (1–2 days) typically held as side sessions within conferences. These sessions facilitate dialogue among experts, scientists, and practitioners through panel discussions and interactive exercises, such as post-it sessions. Capacity Building formats extend over 3–5 days and are designed to strengthen institutional knowledge by engaging multidisciplinary UCCRN experts with local authorities, technical staff, and community representatives. The Design Studio format spans 7–15 days and involves intensive collaboration between experts, students, and stakeholders, supported by preparatory work. It includes public-facing events such as opening lectures and final presentations, fostering broader engagement. The most comprehensive format, the Pilot, unfolds over 3 to 12 months and integrates data collection, climate assessments, co-design sessions, and scenario planning with participatory activities and public dissemination events. Each format is supported by varying degrees of preparatory involvement from the UCCRN team and local hosts, ensuring contextual relevance and depth of impact.

Table 1

| Format | Duration | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge exchange | 1–2 days (plus 2–4 weeks preparatory activities involving UCCRN team) | Panel discussion/post-it session prompted by a pitch from UCCRN facilitators, session or side event within a conference (with experts, scientists, practitioners). |

| Capacity building | 3–5 days (plus 4–8 weeks preparatory activities involving UCCRN team and local hosts) | Workshop with multidisciplinary UCCRN experts and local authorities’ representatives (technical experts, scientists, practitioners, local authorities and communities). |

| Design studio | 7–15 days (plus 8–16 weeks preparatory activities involving UCCRN team and local hosts) | Workshop with multidisciplinary UCCRN experts and students/practitioners (technical experts, scientists, students/practitioners, local stakeholders and communities, with an opening conference and a final presentation as events involving also external audience). |

| Pilot | 3–12 Months involving UCCRN team and local hosts, with 1–3 days of participatory activities | Multidisciplinary UCCRN experts joint with local technical staff for data collection, preliminary climate assessments current state, prototyping: facilitation sessions for co-design, design and planning, future scenario climate assessments, feedback sessions; final presentation as events involving general public |

UDCW formats adapted from Raven et al. (2025a)

4 Results

The section presents the analysis of results obtained by testing the UDCW methodology in eight case studies and achieved through the use of the UDCW toolkits. The results are structured identifying the framework in which the UDCW has been development, the format, the tools applied, the main outcomes and the actors engaged (Table 2). Additionally, details are provided for each case in Table 3 articulated around climate and no-climate priorities, design strategies and synergies, barriers and gaps, innovation. More specifically, Table 3 was structured to map, for each case city, the relationship between innovative strategies, identified barriers and gaps, and design outcomes. This mapping highlights not only the priorities defined in each context but also the tensions between ambition and feasibility. In this way it enables a cross-case understanding of recurrent obstacles and enabling conditionsThis synthesis relies on heterogeneous documentation.

Table 2

| Case | UDCW simulation | UDCW facilitation | State of development | Project framework | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thessaloniki 2024–2025 |

GIS, AAD | Collaborative Mapping, Co-design through district visions | Prototype Diotikirion District Climate Action Plan (DCAP) | UP2030-Horizon Europe | Pilot |

| Rio de Janeiro 2024–2025 |

GIS, AAD | Stakeholders Priorities | Prototype Sao Cristovao District | UP2030-Horizon Europe UCCRN_Edu- Erasmus+Project |

Pilot Design studio |

| Naples 2023-on-going |

GIS, AAD | Stakeholder priorities, collaborative mapping, co-design through city visions, day in the life | Prototype sustainable energy and climate action plan SECAP, Scenario development for San Giovanni neighborhood |

KNOWING-Horizon Europe UCCRN_Edu- Erasmus+Project |

Pilot Design studio |

| Cornella 2024–2025 |

AAD | Community and stakeholders’ priorities, participatory micro-scale actions | Prototype climate itinerary for Sant Ils del Fons neighborhood Scenario development |

Climate Itineraries Cornella de Llobregat- Climate KIC_ | Pilot |

| Granollers 2025 |

GIS, AAD | Stakeholder priorities | Prototype La Bobila, Palau Nord | UP2030-Horizon Europe UCCRN_Edu- Erasmus+Project |

Design studio Pilot |

| Durban 2019 and 2022 |

GIS, AAD | Community and stakeholders’ priorities | Prototype Isipingo district Scenario development Tshelinmyama and Bridge City |

UP2030-Horizon Europe UCCRN_Edu- Erasmus+Project |

Knowledge exchange and capacity building |

| Paris 2020 and 2022 |

GIS, AAD | Community and stakeholders’ priorities | Scenario development for Montreuille district | UCCRN_Edu- Erasmus+Project | Design studio |

|

Sitges

2024 |

GIS, AAD | Community and stakeholders’ priorities | Scenario development for the historical center | UCCRN_Edu- Erasmus+Project | Design studio |

Synthetic overview of cases, application of the toolkits, project framework, formats.

Table 3

| Cases | Key outcomes | Priorities | Design strategies | Synergies | Barriers and gaps | Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thessaloniki | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Masterplan for 2030 and 2050; Exchange activities and workshops; Community mapping; Neighbourhood scale design prototypes. |

Flood and heatwave hazard; public space decay; mobility; accessibility to public spaces | Pocket parks; green walls; Recycling hubs; Pedestrian mobility; PV integration; Shading of streets, increase of cooling materials and permeable surfaces | Thessaloniki District Climate Action Plan (DCAP); Thessaloniki Climate Contract | DCAP not binding; Gaps in building technology information | Detailed district visual to support UDCW facilitation tools application; Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) implementation; integration of community-based information into Simulations; Improvement of UDCW Data collection protocols |

| Rio de Janeiro | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Masterplan 2050; exchange activities and workshops; Neighborhood scale design prototypes. |

Flood and heatwave hazard; informal settlements; spatial justice; Accessibility to public spaces |

Green and Blue infrastructures; Collaborative design strategies | Plan for Sustainable Development and Climate acrion (PDS) Rio Climate Resilience” initiative with Columbia Global center and NASA-GISS G20 Summit |

Lack of adequate financial resources to facilitate the full development of the UDCW | Improvement of Simulation tools HEC-RAS modeling for flood hazard |

| Naples | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Energy efficiency assessments; Community mapping, Strategic line of interventions for the Municipal planning at city scale; Community co-design strategies at district scale; Neighbourhood scale design prototypes. |

Flood and heatwave hazard; waste management issues; lack of green areas; large brownfields and abandoned public spaces; energy poverty; pollution | Climate shelters; Energy hubs; Green and -blue infrastructures; Library regeneration | Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan for Naples (SECAP); KNOWING project alignment; Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy |

Climate strategic policies like SECAP are not binding for urban projects regenerations Gap between city scale simulations and neighborhood scale participatory process Lack of funds for technical implementation and capacity building within municipality |

UDCW tailored to climate justice; improvements in energy consumption simulation tools; Long term stakeholder engagement |

| Cornellà | Land cover studies; Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Masterplan for 2032 and 2040; Neighborhood scale design prototypes; guidelines for NBS integration. |

Heatwave hazard; lack of green areas; open spaces for children; integration of community-based action for social cohesion through gardening | Shading devices; Green roofs and walls; Soil depaving; cool and permeable pavements; green infrastructures | Ajuntament de Cornellà; Cornella Natura | Lack of adequate financial resources for the implementation of the demonstration solution | Catalogue of technical solutions for climate-responsive public spaces; Community action for vegetation planting |

| Granollers | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Neighbourhood scale design prototypes; Climate resilient design guidelines | Flood and heatwave hazard; lack of green areas; public transport issues; | Green corridors; Water squares Soil depaving; cool and permeable pavements; PV integration; pedestrian and cycling connections | Pla d’Acció d’Energia Sostenible i Canvi Climàtic (SECAP) de Granollers; Connecta Congost Natura 2025 (CocoNut25); Plà Estratègic Granollers 2030 |

Lack of information to run energy consumption simulations; UDCW Facilitation toolkit not fully employed | Data integration from satellite & external simulation tools (e.g., Infoworks ICT) |

| Sitges | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Neighbourhood scale design prototypes; Climate resilient design guidelines | Vulnerability of population to extreme heat stress; tourism pressure; Accessibility to public spaces; need for accessible shaded areas and climate shelters | Canopies, green courtyards; shading devices; implementation of heat shelters; preservatioon of existing plant species; dry garden species promotion | Estrategia Catalana de Adaptación al Cambio Climático (ESCCA) 2021–2030; Sitges SECAP | Low accuracy of the simulation tools | Testing of the first version of the UDCW 3DNeighbourhood Configurator Tool |

| Paris | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Subdistrict design prototypes Energy consumption evaluation of the subdistrict prototypes; Co-designed strategies and interventions at district scale | Vulnerability of population to extreme heat stress; heritage conservation; lack of green areas accessibility to public spaces, gentrification; enhancement of public spaces quality | Green and Blue infrastructures; Bio-sourced and geo-sourced materials; Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV); flexibility of buildings functions (e.g., offices reversible into housing); water reuse strategies | New National Urban Renewal Program (NPNRU); C40 Reinventing Cities project | Low accuracy and efficiency of the tools Lack of sufficient community engagement and interaction with policy makers |

Implementation of the UDCW methodology with metadesign strategies (city visions) Test of the first version of the Energy consumption simulation tool at the neighbourhood scale Co benefits evaluation |

| Durban | Current and future climate scenarios analysis; Neighbourhood scale design prototypes; Co-designed strategies and interventions at district scale |

Effects of extreme heat on open spaces; Lack of services, issue with mobility and public transportation, energy poverty, socio-economic vulnerabilities | Green corridors; Soil depaving; cool and permeable pavements; shading devices; space for informal traders | Isipingo Central Business District (CBD) Detailed Urban Design Layout and Implementation Plan; CICLIA-supported Transformative River Management Programme (TRMP) |

Low accuracy and efficiency of the tools; lack of adequate landcover information | Testing of Facilitation tools not yet formalized in the UDCW facilitation toolkit Testing of the first version of UDCW simulation tools Integration of UDCW methodology with on-going project |

UDCW case studies results.

Full simulation archives exist for Thessaloníki, Rio, Naples, and Granollers, whereas Sitges, Paris, Durban, and Cornellà provided predominantly qualitative records. Furthermore, most interventions remain pre-implementation; thus, longitudinal monitoring data is still pending, highlighting the necessity for continued empirical validation. Overall, the eight UDCW applications present some differences in scopes, tools application depth, and temporal continuity. This heterogeneity does not undermine their relevance but should be considered when interpreting cross-case comparisons.

4.1 Case 1 Thessaloniki (2024–2025)

The Diokitirion District in Thessaloniki serves as a prototype pilot area for carbon neutrality within the framework of the EU Horizon project UP2030, under the leadership of the Municipality of Thessaloniki. This initiative aims to develop a District Climate Action Plan (DCAP), employing both the Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) simulation and facilitation toolkit, which have been specifically adapted to meet the requirements of the pilot. The UDCW process progressed from an initial understanding of the urban system to detailed prototype design and masterplanning.

Key outcomes of the UDCW include: the identification of design strategies to enhance the energy efficiency of both private and public buildings; the reduction of urban heat stress; assessment of microclimate performance and open space comfort levels; evaluation of the role of green infrastructure; and simulation of future climate scenarios (2025, 2030, 2050) to assess vulnerabilities and impacts related to urban heat. The process also facilitated the development of community-based strategies to integrate climate-resilient solutions and informed the creation of thematic intervention lines centered on green infrastructure and biodiversity, energy transition, proximity and sustainable mobility, and climate responsiveness.

Actors engaged in the process included the Municipality of Thessaloniki, city public servants, citizens of the Diokitirion District, and Draxis, a private company acting as liaison and technical partner.

4.2 Case 2 Rio de Janeiro (2024–2025)

The São Cristóvão district in Rio de Janeiro has been selected as a prototype pilot area for carbon neutrality within the framework of the EU Horizon project UP2030. This initiative aims to develop a localized prototype in synergy with the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, testing the applicability of Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) tools in alignment with the city’s Plan for Sustainable Development and Climate Action (PDS). The project seeks to translate the PDS’s long-term objectives—climate mitigation, adaptation, and spatial justice—into actionable strategies at the neighbourhood scale. The UDCW simulation toolkit was fully applied in São Cristóvão, while the facilitation toolkit was only partially implemented due to budgetary limitations. Key outcomes include: the identification of design strategies for downscaling Sustainable Corridors into the São Cristóvão neighborhood; assessment of microclimate performance and open space comfort levels; simulation of future climate scenarios focusing on heatwaves and flooding; and a survey of existing community initiatives and socio-spatial practices. Actors involved in the UDCW process included: the technical offices of the City of Rio de Janeiro, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, New York Institute of Technology, UCCRN Secretariat, European, Latin American, and Central American Hubs, Fiocruz, Centro Clima, COPPE-UFRJ, and various civic organizations.

4.3 Case 3 Naples (2023–2025)

The UDCW has been implemented in Naples in two research steps at neighborhood scale in to a design studio format and then up-scaled at city scale through a pilot. Between 2023 and 2024, the UDCW methodology was implemented in San Giovanni a Teduccio, an eastern coastal district of Naples as part of the Erasmus+ project UCCRN_edu.

The district, is affected by marginalization dynamics and chronic pollution and disfranchment of communities and it coumpounds climate stress with complex socio-spatial issues. Outputs of the UDCW included climate scenario assessments, energy consumption evaluations, community-based strategic interventions, co-produced disign narratives, collaborative mapping. At this aim the UDCW facilitation has been tested and tailored with a specific focus on climate justice with an indepth engagement with local community for co-production and co-design (Visconti, 2025). The UDCW was tested to promote a just regeneration of brownfield sites present in the neighborhood reclaiming polluted amenities (beaches), abandoned buildings and neglected public spaces. The UDCW simulation toolkit was also employed later in 2025–2025 at the city scale within the KNOWING EU Horizon project, in which Naples serves as a pilot case. These applications supported the development of the city’s Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP), aligning the UDCW with the city’s planning framework. The UDCW applied within this framework contributed in energy assessment, heat and flood risk assessment, cost–benefit analysis and identification of strategic actions for micro-climate responsiveness, nature-based solutions, and community interventions (such as climate shelthers and energy community hubs). The main actors involved were the Municipality of Naples, the University of Naples, third-sector associations, and residents of San Giovanni a Teduccio.

4.4 Case 4 Cornella de Llobregat (2024–2025)

The case of Cornellà de Llobregat focuses on the district of Sant Ildefons and serves as the prototype for the “Climate Itineraries of Cornellà de Llobregat” project, funded by the Sustainable Cities Mobility Challenge (Climate KIC). The project aims to enhance walkability and accessibility within the city, particularly during periods of extreme heat. To this end, the UDCW simulation toolkit was employed to evaluate thermal stress conditions at both urban and neighborhood scales and to support the development of design scenarios. Additionally, the UDCW facilitation framework was partially used to collect feedback. Outputs of the project include the development of a multi-scalar adaptation pathway, with short-term (2025), medium-term (2030), and long-term (2040) objectives; assessments of current and projected climate conditions related to heat waves; evaluations of microclimatic performance using outdoor thermal comfort indicators; development of a Mediterranean-specific NBS taxonomy and technical catalogue of climate-responsive solutions. The climate-responsive masterplan introduced nature-based solutions (NBS) according to on-going greening policy “Cornella Natura.” The pedestrian greening corridors prototyped through the UDCW culminated in a demonstration project at Rotonda Horts co-implemented with local residents.

4.5 Case 5 Granollers (2025)

The UDCW was implemented in Granollers as design in coordination with the Erasmus+ UCCRN_Edu initiative and as prototype testing in synergy with the EU Horizon projects KNOWING and UP2030. The main objective of this implementation was to facilitate the development of multi-scale urban and design strategies for climate adaptation and mitigation. Although the UDCW facilitation tools were not directly applied, preliminary stakeholder engagement activities and priority mapping informed the design strategies that were subsequently simulated. Simulation tools were employed to assess heatwave and flood hazards at the urban scale and to evaluate outdoor thermal comfort impacts of various urban design prototypes in two key areas: La Bobila and Palau Nord. Even Though UDCW Facilitation tools have not been implemented in the case, preliminary engagement activities and stakeholder priority mapping informed the design and the strategies later simulated. The results obtained from this study include the development of project prototypes, the formulation of climate resilient design guidelines, and the assessment of current and future scenarios with regard to heatwave and flood hazards. The initiative involved academic collaboration between the University of Naples Federico II and the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona), contributing to the scientific and methodological advancement of urban climate adaptation planning in Granollers.

4.6 Case 6 Sitges (2023)

The UDCW methodology in a design studio format was applied in the coastal town of Sitges, in Catalonia, within the UCCRN_Edu programme. The aim was to explore how specific climate-sensitive design strategies can support urban regeneration in coastal zones, integrating flood risk mitigation, heat adaptation and social cohesion. Simulation tools analysed multi-hazard climate risks, focusing on coastal floodings, heatwaves and the loss of public space quality. The primary focus of this study was to assess the efficacy of heat shelters in urban environments, especially the historical centre and the waterfront. In the initial phase of the study, a review of four existing heat shelters was carried out: Casa Farratges, Jardí de l’Hort de Can Falç, Biblioteca Josep i Roig, and Carrer Pau Casals. Subsequently, different prototypes were implemented in the historical centre of Sitges. Facilitation tools included collaborative planning sessions with local stakeholders using stakeholder priority mapping, which allowed participants to integrate climate data with urban design strategies. UDCW facilitation toolkit wasn’t applied but the preliminary engagement activities have been conducted according to the UDCW methodology. Key output include: A series of urban design prototypes experimenting the use of climate shelters and other climate resilient strategies; current and future climate assessment for heat waves; microclimate performances of the implemented solutions (using outdoor thermal comfort indicators). The actors involved were the UIC Barcelona, the University of Naples Federico II, and local stakeholders from the Sitges municipality.

4.7 Case 7 Paris (2022)

The UDCW methodology, implemented as a design studio format, was applied to the urban redevelopment project of Porte de Montreuil, located on the eastern edge of Paris. This initiative was undertaken within a research collaboration supported by the University of Naples Federico II and conducted in synergy with the UCCRN_Edu Erasmus+ project. The principal objective was to integrate climate resilience goals into the masterplan of a dense and socially complex area undergoing transformation through public-private partnerships. Simulation tools were employed to assess heatwave hazard and outdoor thermal comfort across different spatial configurations at both urban scale and neighbourhood scale, with a specific focus on two subdistricts. Facilitation tools were crucial in linking simulation results to lived experiences and stakeholder objectives; notably, the participatory method A Day in the Life was applied to map the daily routines of local users and vulnerable groups within the redevelopment sites.

Principal outcomes comprised preliminary studies on current microclimate conditions and future 2050 Business As Usual (BAU) scenarios; analysis of the urban system including building typologies, mobility and accessibility, traffic, public transport and pedestrian networks, parks, and green spaces; and the design and comparison of several prototypes for the subdistricts implementing four metadesign strategies: the green-blue city, the 15-min city, the zero-carbon city, and the circular city. The process also entailed the evaluation of energy consumption and the assessment of climate impacts and co-benefits of the designed solutions (Addabbo et al., 2023). The initiative involved the University of Naples Federico II, Université Gustave Eiffel, urban designers and consultants engaged in the official redevelopment, and key institutional actors from the City of Paris.

4.8 Case 8 Durban (2019 and 2023)

The UDCW was implemented in Durban in a knowledge exchange and capacity building format through a two-phase initiative that occurred in 2019 and 2023. The objective of this initiative was to support urban regeneration and the integration of climate resilience strategies into existing planning frameworks. The workshops were developed in collaboration with eThekwini Municipality, as part of the UCCRN and UCCRN_Edu initiatives.

In 2019, the UDCW focused on the Isipingo district, where it served dual roles: facilitating capacity building and functioning as a testbed for urban design prototypes. Simulation tools were applied to assess heatwave and flood hazards under three climate scenarios: baseline (2019), business-as-usual (2050), and best-practice (2050). Urban regeneration strategies were developed through a participatory process involving eThekwini city officials, local residents, private sector representatives, and civil society stakeholders. The primary outcomes included preliminary studies on current microclimatic conditions and future scenarios, a detailed heatwave and flood hazard assessment, co-designed interventions at the district scale, and a suite of design prototypes incorporated into the Isipingo Urban Design Framework.

In 2023, a follow-up UDCW workshop was conducted within the CICLIA-supported Transformative River Management Programme (TRMP), focusing on the Bridge City and Tshelimnyama areas and four associated catchments. The UDCW methodology supported the identification of synergies between local community priorities and broader climate adaptation goals. In 2023, a follow-up UDCW workshop was conducted within the CICLIA-supported Transformative River Management Programme (TRMP), focusing on the Bridge City and Tshelimnyama areas and four associated catchments. The UDCW methodology supported the identification of synergies between local community priorities and broader climate adaptation goals. Simulation tools were employed to assess existing thermal stress conditions, while co-design sessions enabled stakeholders to articulate desired urban futures and formulate a roadmap aligned with TRMP objectives. Actors involved were the Urban Climate Change Research Network (UCCRN), the University of Naples Federico II, New York Institute of Technology, the eThekwini Municipality, and local stakeholders and communities.

5 Discussion

The diverse applications of the Urban Design Climate Workshop (UDCW) methodology across eight international case studies—Thessaloniki, Rio de Janeiro, Naples, Cornellà de Llobregat, Granollers, Sitges, Paris, and Durban—demonstrate a wide-ranging interplay of climate objectives, social priorities, technical innovations, and persistent limitations in operationalizing transformative urban regeneration. The section is structured around through four analytical lenses: climate- and society-driven priorities (5.1), technical and governance innovation (5.2), persistent barriers (5.3) and methodological implications (5.4).

5.1 Climate- and society-driven priorities

Across all pilots, the methodology confronted two entwined agendas: climate risk reduction and socio-spatial equity. Heat-wave exposure and pluvial or fluvial flooding were the most recurrent hazards, whereas energy poverty, inadequate public space and mobility inequities emerged as dominant non-climatic concerns. Table 3 (Results) evidences how every city combined adaptation and mitigation aims with distributive, recognitional, procedural and restorative justice considerations (Reckien et al., 2025; Visconti, 2025).

A salient pattern is the scale coupling between neighbourhood prototypes and city-wide policy frameworks. In Naples, a robust climate justice framework has been introduced to implement the UDCW at the neighborhood scale, anchoring climate priorities in overlooked community narratives while strengthening technical assessments at the city scale through the SECAP; Rio de Janeiro down-scaled the Plan for Sustainable Development & Climate Action linking it to grass-root initiatives; Thessaloníki’s Diokitirion District fed into the city’s Climate Neutrality Contract. This vertical integration highlights the potential of UDCW as a sensemaking tool that helps align strategic visions, on-the-ground spatial transformation and citizens daily experience, illustrating its capacity to integrate multiscale approaches to urban design with governance trajectories, planning instruments, and community innovation.

By embedding climate adaptation and mitigation goals within existing local development concerns, the methodology enabled climate action to serve as a unifying platform rather than an additional or isolated agenda, reinforcing its legitimacy across diverse institutional and community contexts.

Advancing the climate agenda amid competing urban priorities—such as poverty reduction, affordable housing provision, governance deficits, and gentrification or marginalization dynamics—required a reframing rather than a parallel pursuit of goals. Across the pilot cases, climate action was strategically articulated through co-benefits that addressed these interconnected challenges. Heat-stress redutction was linked to energy-efficient housing retrofits and reductions in energy poverty; flood-risk management was integrated with the upgrading of public spaces and mobility systems; and participatory mapping processes revealed governance gaps while fostering institutional accountability.

Thus, the methodology positioned climate action as a transversal driver of inclusive urban transformation.

The integration of justice within climate- and society-driven priorities proved both essential and challenging. While the methodological framework explicitly embeds procedural, distributional, recognitional, and restorative dimensions of justice, their translation into practice revealed the complexity and, at times, the contestation inherent to real-world implementation. Stakeholders often approached climate priorities from differing standpoints (technical, social, or political) requiring facilitators to navigate conflicts and asymmetries in power and capacity. Rather than treating justice as an abstract principle, the UDCW approach operationalized it through concrete tools: Collaborative Mapping fostered early-stage participation and spatial recognition of inequalities; City Visions and Local Needs Matching aligned climate resilience with socio-spatial equity; and Day in the Life exercises surfaced differentiated vulnerabilities and experiences. Across pilots, these “reality checks” exposed both the potential and the limits of participatory justice, showing how inclusive processes can reveal competing expectations and institutional constraints. In this sense, the methodology positions justice not as a fixed outcome but as an evolving, negotiated process—one that situates climate adaptation and mitigation within the lived realities and governance dynamics of each city.

5.2 Technical and governance innovation

Technical advancements and inclusive governance approaches were mutually reinforcing across the UDCW pilots. The integration of advanced environmental modelling—GIS–HEC-RAS coupling in Rio, satellite-based NDVI–LST overlays in Granollers, and the 3-D Neighbourhood Configurator implementation in Naples, Thessaloniki, Granollers, Sitges and Cornellà - enabled rapid iteration and clear visualization of climate impacts, substantially reducing the ‘design-to-impact’ timeline and democratizing climate data access (Nocerino and Leone, 2024).

In parallel, qualitative and experiential engagement methods, including collaborative mapping, City vision exercise, Day-in-the-life applications in Naples, in Thessaloníki, and Paris jointly with stakeholder priority mapping, climate walks such as in Paris, Durban, and demonstration project like in Cornella effectively translated abstract metrics into lived experiences, embedding justice dimensions directly within design decisions (Goncalves et al., 2025).

The flexible adaptation of the methodology to various institutional and temporal frameworks, exemplified by design studios in Sitges, Granollers and Paris, long-interactions pilots in Cornellà, Rio and Thessaloniki and capacity building workshops in Durban, highlight the UDCW’s adaptability to distinct governance contexts and opportunities making it adaptable to different institutional rhythms resource envelopes and research opportunities.

5.3 Persistent barriers and future roadmap

Despite significant achievements, several barriers limited the UDCW application, suggesting a future roadmap to guide a broader impact and implementation.

First, data scarcity emerged as a recurring constraint, limiting the effectiveness of simulation and scenario-building processes. In the case of Durban, limitations were identified not only due to an embryonic state of simulation tool development, but also due to insufficient availability of local climate data. In the case of Thessaloniki, however, despite the significantly more advanced state of tool development, the accuracy of the results was compromised by the limited availability of detailed data concerning the construction features of the buildings. This difference also reflects the evolution of the UDCW Simulation Toolkit itself: Durban applied an early version with a limited set of performance indicators, while Thessaloniki, being one of the most recent workshops, benefited from the latest version, capable of producing additional performance metrics, such as neighborhood-scale energy consumption.

Second, institutional inertia hampered effective uptake and integration into formal governance mechanisms: Thessaloníki’s District Climate Action Plan remains advisory rather than binding, and Cornellà’s proposed climate itineraries should include more fundings to be upscaled, highlighting the persistence of an ‘ambition–feasibility gap’ and the lack of mechanisms able to translate strategies into enforceable actions (Uittenbroek et al., 2014). Third, inadequate financing posed challenges for scaling pilot interventions to city-wide implementation. Both the Rio case and Napoli case highlight a notable difficulty in the transition from strategic projects to systemic urban solutions or tangible community-based urban transformations addressing multiple challenges such as marginalization, access to urban services or quality of public spaces. Moreover, participatory practices included in the UDCW facilitation toolkit to be effective in terms of justice comprehend sustained stakeholder engagement, and require careful tailoring of the tools to guarantee the recognition of preexisting inequalities and community agency (Visconti, 2025, Raven et al., 2025a). This is revealed particularly by the Paris and Sitges case where gentrification and touristification tensions existed, and Napoli case where socio-economic and socio-ecological vulnerability chronically affect the communities (Visconti, 2023). These experiences underline the importance of aligning participatory processes with local claims, socio-spatial dynamics and contexts by expanding the engagement of both scientists and citizens, inclusivity and representativeness. Finally, a key barrier lies in comparing cases implemented with different scopes, facilitation depth, and timelines, potentially affecting the assessment of long-term outcomes.

5.4 Methodological implications

Reflecting on these experiences, methodological improvements can be identified in the synergies between UDCW facilitation and simulation toolkit supporting the UDCW methodology in its full implementation. The integration of analytical modelling with participatory facilitation resulted in a substantial enrichment of process activities and outputs This was evidenced by pilots conducted in Naples and Thessaloniki, which demonstrated greater social legitimacy and technical robustness in comparison to separate deployments of these elements, as observed in Granollers and Rio cases. Secondly, developing implementation pathways in the early phases of planning and design development was beneficial, particularly in the cases in which they aligned with existing planning instruments. In these cases, the UDCW process helped translate broad strategies into concrete project proposals with associated metrics, allowing their incorporation into formal planning frameworks such as Climate Action Plans or SECAPs.

The multi-scalar nature of climate mitigation and adaptation was addressed through the nested application of the UDCW toolkits, linking neighborhood-scale prototypes with city-wide planning frameworks and regional or international initiatives such as SECAPs and Climate Neutrality Contracts. This integration allowed cross-scalar consistency between local co-design actions and overarching policy targets. However, the process also exposed several gaps and coordination challenges, especially between local implementation capacities and the broader frameworks for monitoring and reporting at national or EU levels. These findings emphasize the need for a more systematic vertical alignment of data, governance mechanisms, and evaluation procedures across scales.

This need for vertical coherence was also reflected at the operational level. In Durban, for instance, even though the toolkits were still in the preliminary stages of development, they provided a framework for a dialogue among all the actors involved. The multi-actorial approach helped to mitigate some of common implementation barriers that were previously observed in other contexts due to siloing interactions.

In the third instance, the integration of justice framework at key methodological stages (analysis, co-design, prototyping) like in Thessaloniki and Naples, if applied in the planning instruments by local authorities, can deliver, at the early stages, participatory processes thereby enhancing both procedural fairness and recognitional and distributive justice aspects. Furthermore, the co-production of knowledge and the adoption of open-source data standards and open-source data formats like shapefiles, led to enhanced transparency, accessibility, and local ownership of data and outcomes.

Future research should prioritize validating the integration of designer and planner-friendly interoperable tools that assess climate benefits at different scales, both in terms of comfort-related quantitative indicators and quantitative and qualitative co-benefit indicators, including socio-spatial justice configurations. These frontiers will make it possible to better spatialize community needs that are often not directly climate-related, aligning them with climate-resilient design opportunities that contribute to delivering just urban transformations.

6 Conclusion

These eight international case studies delve the persistent tension between the ambition of climate-responsive urban design and the fragmented institutional, financial, and socio-technical realities that constrain its implementation. While certain climate-resilient measures have been implemented in several cities globally, numerous available strategies remain unutilized. This reflects a persistent inertia in different policy contexts, where neither binding nor non-binding instruments are systematically applied to support climate-responsive design (Brandsma et al., 2024). The UDCW methodology emerges in this context to bridge this divide between climate science, design practice, local communities and policy makers, creating an iterative, collaborative environment that can mainstream evidence-based, equity-oriented approaches (Raven et al., 2025a). However, the findings highlight that as mainstreaming approaches rely on institutional entrepreneurs to embed climate objectives within policies, such efforts can remain erratic or symbolic without mechanisms to translate strategy into enforceable action (Uittenbroek et al., 2014). Indeed, instruments become more effective when methods are offered to assist planners and designers in implementing context-driven urban climate-responsive strategies (Scherer et al., 1999) underscoring the necessity of discrete tools—such as climate maps, assessment procedures, and interoperable design platforms—to operationalize adaptation within diverse urban fabrics (Cortesão et al., 2020).

While this study primarily focused on refining and testing the UDCW methodology, it also recognizes the importance of situating this framework within the broader landscape of participatory and evidence-based planning approaches. Recent contributions, such as Yamasaki and Murayama (2025), have explored district-scale design workshops for climate adaptation in Japan, offering complementary insights into how collaborative methodologies can support urban resilience. A more systematic comparison with such approaches, and with similar toolkits like Urban Living Labs or Resilience Hubs, represents a promising direction for future research aimed at consolidating transdisciplinary learning and methodological convergence.

At the same time, the UDCW prototypes demonstrate that advancing transformative adaptation and just urban transitions requires not only innovative tools and co-design processes but also the cultivation of a governance culture capable of aligning scientific knowledge, community aspirations, and enforceable policy instruments in an integrated and adaptive manner beyond purely technical fixes (Nightingale et al., 2019). The UDCW implementation indicates that effective climate-responsive design must move beyond general standards and universal principles to embed explicit, flexible, and locally grounded instruments that engage citizens, scientists, public institutions and practitioners thereby supporting the transition from isolated demonstrations to institutionalized, city-scale change.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ML: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge the financial support provided by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 101096405.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all our colleagues who contributed to the development of the UDCW in collaboration with local institutions and made its implementation possible across different cities. In particular, we are grateful to Margot Pellegrino, Bruno Barroca, Enza Tersigni, Marilena Prisco, Sean O’Donoghue, Maria Fernanda Lemos, Martha Baratha, Maria Dombrov, Cynthia Rosenzwaig, Lorenzo Chelleri. A special thank goes to Jeffrey Raven who initiated the UDCW experience and developed its initial methodology, giving us the opportunity to conceptualize and test the toolkits. We also extend our sincere appreciation to all the citizens, local NGOs, and students who actively participated in the UDCW and make possible our research and to Antonio Sferratore and Hossein Ghandi who illustrate the UDCW methodology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Authors’ note on language editing: This manuscript has benefited from language editing support provided by ChatGPT, an AI-based tool developed by OpenAI. The tool was used exclusively to check the grammar, and fluency of the English text. All content, including ideas, results analysis and interpretation, discussion, and conclusions and the writing of the article was developed entirely by the authors without AI assistance.