Abstract

Introduction:

Sustainable and equitable home-based healthcare in rural areas requires service systems that balance efficiency, fairness, and responsible resource use, particularly under constraints of limited personnel and dispersed populations.

Methods:

This study proposes a computational sustainability framework for optimizing multi-cycle routing and scheduling of nursing staff in rural China. A bi-objective model is developed to minimize operational costs and maximize equitable service accessibility. A service-time-prioritized greedy algorithm, a customized genetic algorithm, and a tabu search procedure are applied and evaluated using publicly available datasets.

Results:

Compared with classical and random heuristics, the proposed methods achieve approximately 10–15% reductions in operational costs and significant improvements in service equity, measured using a modified Gini coefficient.

Discussion:

The framework integrates efficiency optimization with principles of circular resource management and community-oriented service design. It provides a scalable decision-support tool for planners and contributes to sustainable rural healthcare delivery, aligning with SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

1 Introduction

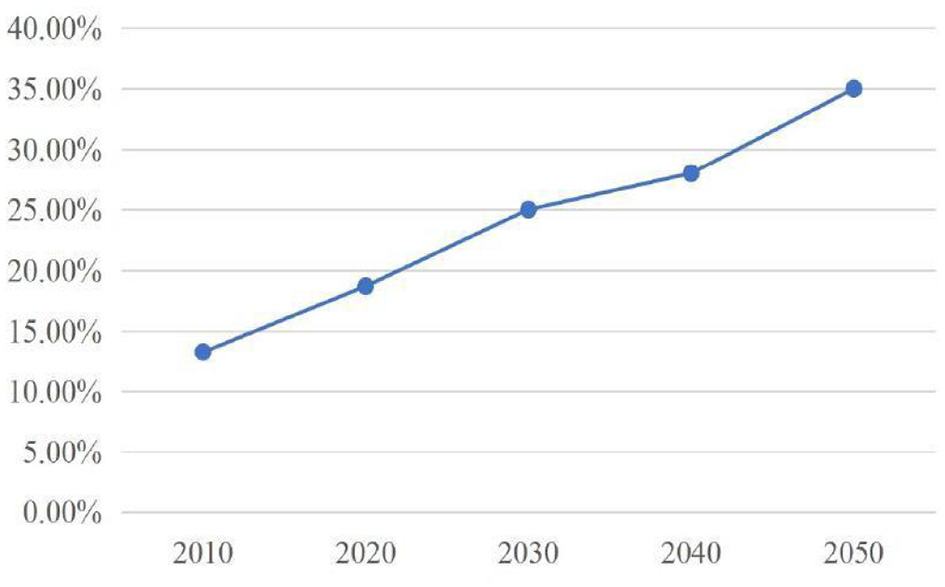

A study by Li et al. (2023) determined that by the end of 2020, the population of the People's Republic of China aged 60 and above had reached 264 million, accounting for 18.7% of the total population (Figure 1). By 2030, the older adult population is expected to reach 371 million, which will represent 25% of the total population; by 2050, it is expected to account for 35% of the total population, at around 400 million. Among the older adult population, those aged 80 and above will exceed 100 million, and the number of people with disabilities and dementia will exceed hundreds of millions. There is consequently a sharp increase in the demand of the available and sustainable healthcare services especially home-based care.

Figure 1

Trend of aging in China's population. This figure illustrates the rapid growth of the elderly population in China, underscoring the urgency for scalable home-based healthcare solutions.

In rural China where a greater number of the elderly population are found then, the challenge is even acute. The rural population is geographically dispersed, lacks adequate transportation facilities, is uneven in its distribution of medical facilities, and lacks sufficient professional-level caregivers. Although there have been new government efforts of the promotion of the concept of a healthy China in the year 2030 and the introduction of community-based elderly provisions, it is still inadequately practiced in rural areas. The gap between urban and rural areas in healthcare delivery is expanding, and elderly people in villages do not always have the opportunity to receive care in a timely and uninterrupted format as urban patients (Guo et al., 2023).

Although it has positive sources of experience in home care overseas, they are not directly applicable in the situation in China in rural areas due to the combination of scattered settlements, insufficient healthcare budgets, and lack of digitalization of the area. Current Chinese literature has focused much on urban pilot projects or theoretical proposals but did not apply them practically in rural settings (Li et al., 2023). This leads to a severe research gap: little empirical and methodological research on the nature of maximizing home-based healthcare delivery systems to rural elderly groups.

In addition to logistical and infrastructural factors, the sociocultural forces have a major influence on determining the trends of healthcare delivery in rural China. The family-based care of the elderly, gendered care providing, and social behaviors about external care provision are cultural factors that affect the demand and efficiency of service allocation. In rural areas, instead of institutional or urban care providers older adults allow familiar local caregivers to provide care, and this route or acceptance will influence the routing and acceptance of services. Besides, the priority of caregivers assignment is more often based on social cohesion and kinship networks and affects the operational decision-making of the distance objective and cost-based considerations. It is essential to identify these cultural and social backgrounds in order to come up with acceptable and practical models of service allocation to the rural communities.

This paper bridges this gap by coming up with a sustainable routing and resource allocation model which is based on the vehicle routing problem (VRP). The two-fold interests which are minimizing travel cost and enhancing service equity, are reactions to the practical need to minimize inefficiencies and at the same time, equity in services to dispersed populations of rural elderly. Through evaluating heuristic optimization algorithms on synthetic datasets that simulate the rural demographics and geography, this study will not only offer a methodological novelty but also a policy-relevant contribution toward the rural planning of eldercare in China.

This study used three heuristic algorithms Greedy, Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Tabu Search (TS) because they are complementary search methods, and have demonstrated past performance and scalability in resolving vehicle routing problems (VRPs) and performance on their respective combinatorial optimizations in healthcare logistics. The main aim was to test the balance between computation efficiency and quality of solutions of the various algorithms with two objectives of minimizing a cost as well as equity in the services. Detailed descriptions of the Greedy, Genetic Algorithm, and Tabu Search procedures, including operator definitions and parameter settings, are provided in Appendix A.

The combined use of these three algorithms supports comparative analysis across a complexity spectrum, from deterministic to stochastic and memory-based metaheuristics, thereby reducing the risk of bias that might arise from relying on a single optimization paradigm. Their inclusion provides insights into computational trade-offs, operational feasibility, and sensitivity to data heterogeneity.

The expansion of the Internet and information and communications technology has facilitated the development of global models, including Honor, eCare Daily, and Hometouch, that combine intelligent platforms for older adult healthcare with home care services and which have achieved positive results (Kelekci and Kizir, 2023). Compared to traditional medical and nursing services, these models reduce hospitalization expenses for older adults and alleviate the service pressure on medical centers. The models are supported by governments; for example, the Swedish government provides financial support for developing home healthcare planning systems, which have improved operational efficiency by 10%−15% (Lan and Chen, 2023). These software systems cover various aspects of patient healthcare, such as vital sign monitoring, emergency management, stroke rehabilitation strategies, drug management, and remote medicine (Jenila and Canessane, 2023), and provide home care service data and resources to facilitate the sharing of nursing information between users and caregivers. General home care service institutions can provide door-to-door services, such as medical diagnosis and treatment, daily care, indoor cleaning, and medication delivery to older adults through these platforms. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of home healthcare: As the SARS-CoV-2 virus is transmitted through respiratory droplets or person-to-person contact, the probability of being infected is greater in hospitals and outdoor places; therefore, home healthcare services greatly reduce individuals' risk of contact or infection (Guo et al., 2023). As such, in addition to these prominent issues, resource allocation and spatial optimization have practical significance in providing care for the older adult population in rural China, which was the starting point for this study.

This study is designed to directly support decision-making for local health bureaus, township health centers, and community-based healthcare providers in rural China. The proposed model addresses practical questions such as how to allocate limited home-care vehicles, whether intermediate transfer points should be established, and how to balance efficiency with equity in service delivery. By providing quantitative indicators and threshold values, such as travel cost benchmarks and service equity ratios, our framework enables policymakers and practitioners to evaluate trade-offs and implement data-driven allocation strategies.

To strengthen the alignment with sustainability and community-based management perspectives, we frame this VRP-based approach within the Computational Sustainability paradigm. From this viewpoint, routing and scheduling are interpreted not only as efficiency problems but as management of circular resource use—reducing redundant travel, lowering energy consumption, and improving shared utilization of vehicles, staff time and other limited resources. This framing connects tactical optimization outcomes (cost, equity, coverage) to strategic sustainability goals at community and municipal scales.

2 Literature review

Numerous studies have addressed the path and scheduling problems in home healthcare. These problems were first proposed by Sachidanand V Begur (1997, as cited in Niu et al., 2023), who considered them a combinatorial optimization problem. Subsequently, scholars proposed mathematical models and algorithms to solve this optimization problem. The scheduling and allocation of nursing resources and the planning of nursing paths can be reduced to the “vehicle routing problem” (VRP). Most research in the field is, thus, closely related to the VRP, and the home nursing path and scheduling problem is described as a “VRP with multiple attributes.” The VRP was first introduced in the home healthcare field by Bouška et al. (2023). To ensure that the design of problem models of home healthcare paths and scheduling function in practice, scholars have focused on three aspects: nursing periodicity, objective function, and constraints of the nursing staff.

The periodicity of nursing staff is divided into two categories: single-cycle and multi-cycle. The single-cycle category involves the problem of setting a 1-day cycle for a caregiver's care path (Wang et al., 2023). Wen et al. (2023) proposed a multi-objective optimization model with a 1-day cycle and an improved simulated evolutionary algorithm to solve this problem. Nursing staff work 6–8 h daily, with an hour lunch break. Cardoso et al. (2023) considered the lunch break as a constraint for the home healthcare nursing path and scheduling problems and established mathematical models and solutions using real datasets. Similarly, as traffic conditions change at different periods of the day, Zhang et al. (2022) analyzed the time spent by nursing staff taking public transportation and walking at different times and designed an effective and accurate algorithm to calculate the changes in the time spent traveling. The obtained time was solved in the form of a matrix as an input to the problem. In addition, Cardoso et al. (2023) considered that in the event of a natural disaster, service time and travel time would increase, leading to an increase in waiting time for older adults. They considered this waiting time to be a free rest time and analyzed the model's sensitivity as a constraint. Further, to ensure fair work distribution among nursing staff, LeBlanc (2021) maximized the quality of home care services and minimized travel and working time by balancing working hours and analyzing a situation in which multiple nursing staff simultaneously care for a patient.

The multi-cycle category is an extension of the single-cycle category that considers the work constraints on caregivers within a cycle and arranges nursing paths for caregivers for two or more days. Wang et al. (2020) developed a plan that arranged a 1-week nursing pathway, setting specific overtime fees for different levels of nursing staff and maximizing the number of nursing paths completed by them. Compared to a single cycle, nursing continuity is regarded as a constraint or optimization objective for the multi-cycle category. Castellucci (2017) suggested that nursing continuity is an important reference indicator for the problem of multi-cycle home nursing routing and scheduling. When the planning scope of the nursing pathway is extended to at least 2 days, if a caregiver provides nursing services to the same older adult multiple times, it improves nursing continuity. Lin et al. (2017) proposed an expected effective capacity method to address the problem, allocating newly added older adults while maintaining care continuity: their method allocates nursing staff with higher expected effective capacity values to newly added older adults, thereby significantly reducing their service timeout. Meanwhile, Matt et al. (2015) designed a plan to rearrange nursing paths based on changes in the number of older adult clients and uncertainty to ensure nursing continuity and job satisfaction and minimize idle time.

Most studies on home healthcare routing and scheduling problems are based on certainty. However, in reality, uncertain events, such as the temporary cancellation of service requests, changing service needs, or changes in caregivers' nursing time, are commonplace. McIntosh et al. (2010a) considered uncertain service time within the scope of a single-cycle nursing path, suggesting a punishment mechanism for late caregivers. They introduced an approximate formula to estimate the degree of punishment, divided the problem into a main problem and a branch pricing sub-problem, and used an improved label algorithm to solve it. In addition, the process of transporting medications by caregivers and the amount of medication used by older adults are also uncertain when planning nursing paths for caregivers and older adults in home healthcare institutions. McIntosh et al. (2010b) used a fuzzy variable to represent uncertain factors, such as drug quantity, and proposed a home care path and scheduling problem based on fuzzy chance constraints to minimize the cost of caregiver travel. Furthermore, recent studies have highlighted the importance of accounting for uncertainty in travel and nursing times.

In summary, the literature reviewed above confirms that the resource allocation and spatial optimization of family medical services for older adults have a deep research foundation. However, many previous studies did not use targeted quantitative data. This study used data from older adults in rural China, rather than other countries around the world, meaning the results are expected to be more generalizable across China. The study's core objective was to establish a home care route and scheduling model and test the corresponding spatial optimization problem, simplifying it into a multi-station vehicle path optimization problem. The study demonstrated the uncertainty polynomial time difficulty of the problem and conducted a reliability analysis.

3 Materials and methods

This research paper starts by clearly stating the problem scenario of the home-based healthcare in rural China. It is based on maximizing service provision in which geriatric patients are spread over extensive rural territories that have poor infrastructure. The formulation is as a capacitated vehicle routing problem (VRP) with two aims, which include minimizing the operating costs and service equity maximization. In order to model this case, three critical components are brought into the limelight, namely, demand distribution, capacity of supply and transportation limitations.

Demand distribution: the provision of elderly care is heterogeneous, which includes not only the simple healthcare (medicine delivery, injection, monitoring of chronic conditions), but also non-medical care (daily living assistance, cleaning, preparing meals), and special care (dementia and disability support). All patients will be described based on a type of service, number of visits (daily or weekly or monthly), and urgency. The demand is suitably distributed across the villages and townships and service is distributed depending on the need.

Service supply: a combination of doctors, nurses, and trained caregivers employed by local healthcare institutions is the one who provides care services. The capacity limits of each provider clearly spelled out working hours, number of patients to attend within a given cycle, and qualification of the professionals that limits the type of patients that the provider can attend to. Providers can have a starting point at various depots (health centers, clinics or mobile units) and continuity of care is taken into consideration wherever feasible.

Additional methodological rationale supporting the multi-cycle VRP structure and heuristic selection appears in Appendix D.

3.1 Path planning and home healthcare scheduling

The problem is modeled as a multi-cycle capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (VRP-TW). The study employ a bi-objective formulation to explicitly balance operational efficiency (minimizing total travel cost and time) with equity (maximizing fair service accessibility across all patients). The complete mathematical formulation, including detailed constraint equations, is provided in Appendix B.

3.1.1 Data and scenario generation

The study uses a hybrid dataset, combining real-world administrative and GIS data for calibration with synthetically generated scenarios to ensure robust algorithmic testing across diverse rural conditions. Uncertainty in travel and service times, common in rural settings, was incorporated through Monte Carlo sampling. Detailed parameter values and full validation results are presented in Appendix C.

3.1.2 Heuristic algorithms for the bi-objective problem

To solve this NP-hard problem efficiently, these three heuristic approaches prioritize trade-off exploration:

-

1) Service Time-First Greedy Algorithm for an efficient baseline;

-

2) Customized Genetic Algorithm (GA) for global exploration; and

-

3) Customized Tabu Search (TS) for local exploitation.

Both the GA and TS utilize a composite evaluation function designed to simultaneously manage cost and service equity. Furthermore, a risk-assessment mechanism based on a vague set approach was incorporated to quantify and manage uncertainty thresholds in the final routing solution. Specific algorithmic parameters and the technical details of the risk mechanism are detailed in Appendix E.

3.1.3 Nursing service providers

Nursing staff (medical and non-medical service providers) have various attributes, such as their service skills, service levels, language type, and working hours. The types of nursing staff in this study included hospital doctors, nurses, and other caregivers. According to different professional types and levels, these professions were further categorized and constrained when being assigned to older adults, based on the participant's service qualifications or skills. In home healthcare, nursing staff provides care services to older adults at their home location based on their needs. We ensured an equal gender representation in the sample.

The participants were 60 older adults from different nursing homes located in the Shanghai area of China. The nursing staff recruited in this study did not need to start from the same point. Serving older adults beyond or before the scheduled service window can impact the objective function. In addition, nursing continuity was considered in the context of multiple cycles as the nursing staff could provide nursing services to older adults in continuous, partially continuous, or discontinuous situations.

The investigation was completely anonymous and was supervised by officials from the Chinese government's cybersecurity department. The survey data were saved for authorized viewing only. Each participant received equal information and personal protection. If the participant declared any illness or accident, they were excluded from the study.

3.1.4 Home healthcare institutions as nursing pathway decision-makers

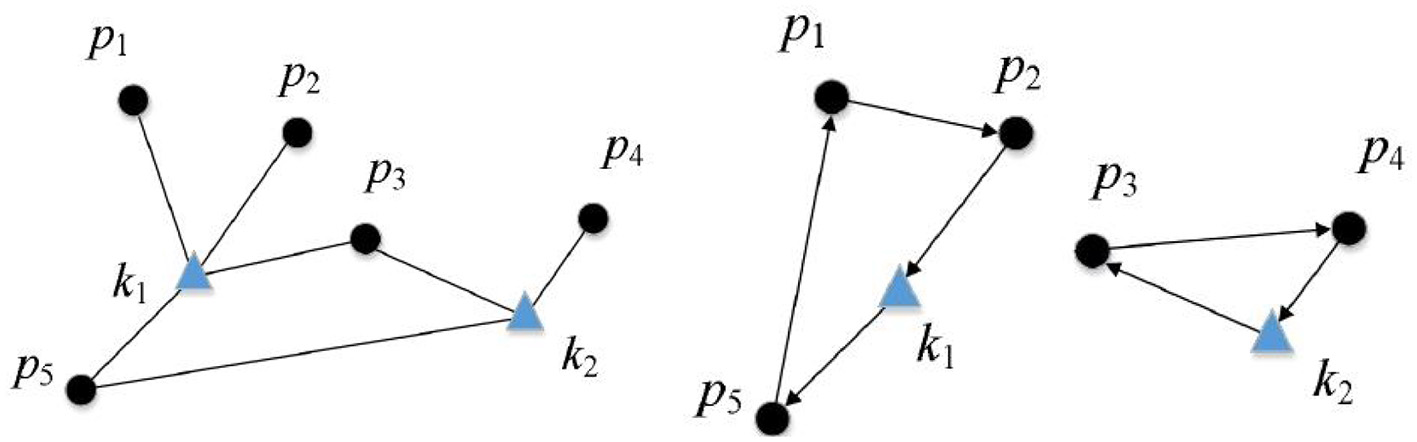

Home healthcare institutions are broadly divided into two types: nonprofit and for-profit. In this study, the home healthcare institutions were for-profit institutions. Healthcare institutions are responsible for arranging different types of nursing staff to provide a range of home care services to older adults, such as nursing, medication delivery, injections, and sample collection. For-profit institutions plan and make decisions about the nursing staff's service path from the profitability perspective, proposing reasonable plans to reduce costs and increase profits (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Scheduling and nursing pathways. The diagram shows how healthcare institutions allocate caregivers and plan routes, highlighting the decision-making structure central to the model.

3.2 System model

Conceptually, the optimization of home-based healthcare logistics can be viewed as managing a circular flow of community resources—vehicles, caregivers' labor-time, and energy—among distributed demand nodes. Under this lens, route planning reduces redundant circulation, increases shared utilization of assets, and minimizes wasteful trips, thereby operationalizing circular resource-use principles within local service systems.In addition to representing routing efficiency, the objective terms can be interpreted through a computational-sustainability lens, where cost minimization reflects reductions in resource waste and energy consumption, and equity terms represent community-embedded service design. The full mathematical formulation, including all routing, scheduling, and vague-set equations, is presented in Appendix B.

This study considered a multi-cycle home healthcare path planning and scheduling model, consisting of older adults, caregivers, and home care institutions. In this model, the nursing cycle is defined as follows:

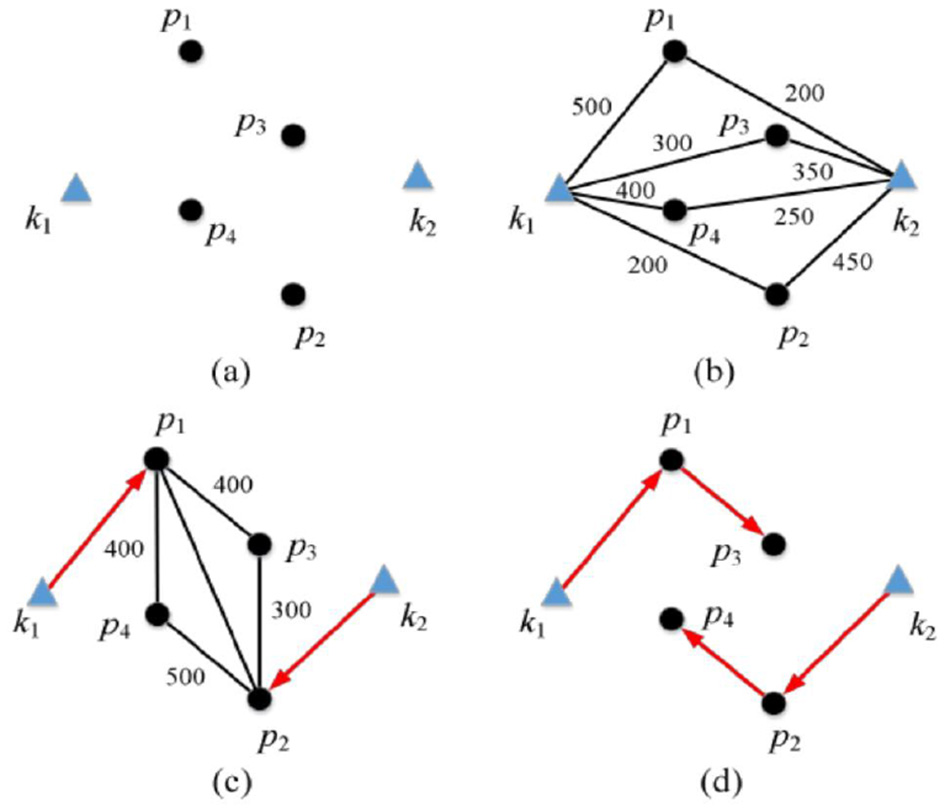

As the cost and service quality optimization problems are nondeterministic polynomial time hard problems, the time to obtain the optimal solution exponentially increases with the size of the problem being solved. To obtain a feasible and reasonable solution within an acceptable time, this study proposed a “service time-first greedy algorithm” (henceforth, the “greedy algorithm”) for the cost and service quality optimization problems. The greedy algorithm had roughly the same process for solving both problems. The algorithm sorted the older adults in ascending order according to the start of their waiting time for services within each working day and traversed all older adults in sequence. Priority was given to older adults who started waiting for the service earlier to allocate idle and lowest operating costs (highest service quality) to nursing staff. A diagram of the greedy algorithm is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3

(a–d) The greedy algorithm process diagram. This visual demonstrates the step-by-step allocation process of the greedy algorithm, which serves as the initial solution baseline.

3.3 Methodological contribution and limitations

The suggested method improves the efficiency of traditional home healthcare resource management and spatial optimization systems against three critical limitations: flexibility to deal with extensive rural population distributions, intersection of spatial and resource dimensions, and limitations on scalability. Previous models addressed the spatial and resource dimensions independently, and while doing so, they did not work very well in responsive dynamics of rural areas. In addition, the majority of systems were unable to affect an efficient or equitable provision of healthcare when they were transferred to areas with a varied geography and demography. The model being described uses a two-tiered format that involves the integration of spatial clustering and integer programming. This provides a facility for it to respond reasonably to differences in population density and terrain between areas, while optimizing the distribution of healthcare professionals and services to provide dynamic changing community demands.

But this combined approach is accompanied by some computational trade-offs. The use of a double-layer optimization process necessarily increases the model's complexity, requiring more processing power and robust datasets to operate effectively. As such, the system's responsiveness depends heavily on input data quality and specificity such as geographic points, health facility locations, and population trends. Though this may prove to be a challenge for data-poor or low-resource rural areas, the sacrifice is justified by the model's enhanced ability to deliver accurate, adaptable, and efficient healthcare solutions. The increased service availability and logistic uniformity are likely to overshadow the high computational costs, particularly when performed through systems capable of leveraging central or hybrid computing environments. In essence, the strategy adopts a deliberate balance of precision and resourcefulness in order to better address the understated demands of rural healthcare systems.

4 Results and analysis

All experimental results reported below were produced from synthetic scenario instances that were calibrated against the empirical sources described in Section 3 (census data, provincial yearbooks, and GIS travel layers). Where empirical pilot data (Shanghai sample) informed early calibration or demonstration runs, those figures/tables are explicitly labeled as empirical. The fundamental concept behind customized genetic algorithms is the simulation of the so-called survival of the fittest and the selection of the solution that best fits its environment. The initial solution generated by the greedy algorithm was used as the initial population of the customized genetic algorithm and was encoded. The next-generation population was obtained through crossover, mutation, and selection operations, and these steps were cycled. When the number of iterations reached a specified value, the cycle was terminated and the problem solver with the highest fitness was found in the iteration process and considered as the solution of the algorithm. This study customized the fitness function, crossover, and mutation operations according to the multi-cycle nature of the cost and service quality optimization problems.

The study's dataset comprised three sets of instances of different scales—small, medium, and large—each with 20 specific instances. Each small-scale example included 40 older adults and five idle caregivers, the medium-sized example included 80 older adults and 10 caregivers, and the large-scale example included 150 older adults and 20 caregivers. We compared the total operating cost of home healthcare institutions with the benchmark algorithm in the experiment and the service quality of home healthcare institutions with the benchmark and random algorithms. The proposed benchmark algorithm was based on the “multi-depot VRP” in Smith (2016). In the cost optimization problem, the greedy strategy prioritized the arrangement of nursing staff who can provide the lowest operating cost (or highest service quality) for older adults with the longest service duration. In contrast, in the service quality optimization problem, the greedy strategy prioritized arranging nursing staff who can provide the highest service quality for older adults with the longest service duration.

Although the suggested model successfully maximizes the cost and service equity in the computational sense, its application to the rural communities should observe sociocultural realities. The community trust and the familiarity levels between the caregivers and the patients, as well as cultural preference between the home based care and the family provided care is a social aspect that can greatly interfere with the operations in making the decisions concerning the routing operations. In locations, in which the social proximity or personal connection of older adults is more important than speedy service delivery, the ideal algorithmic pathway might need to be changed to indicate the acceptance of social methods. Similarly, the policy of scheduling and workforce distribution should be based on informal caregiving norms, which are frequently influenced by intergenerational reciprocity and social capital within a specific area. The combination of such factors would contribute to not only the accuracy of the model but to the effectiveness of the healthcare delivery system in the community and its sustainability.

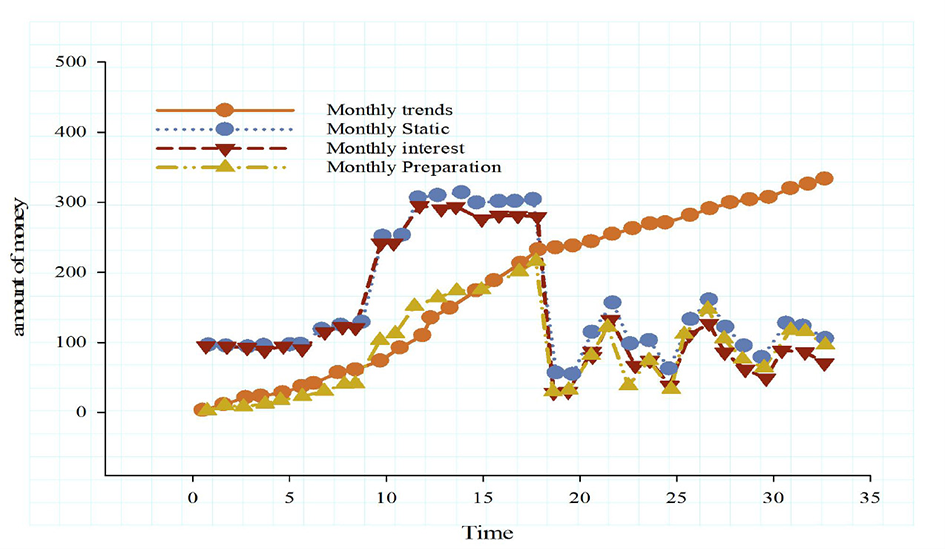

4.1 Scheduling costs

This study compared the results of its three proposed algorithms, the greedy algorithm, customized genetic algorithm, and customized Tabu Search algorithm, with the benchmark algorithm for small, medium, and large datasets, as listed in Table 1. Figures 4, 5 compare this study's algorithms with the benchmark algorithm based on the total operating cost of home healthcare institutions. Figure 4 demonstrates that for small-scale datasets, the average operating costs obtained by the greedy algorithm, customized genetic algorithm, and customized Tabu Search algorithm decreased by 39.34, 49.83, and 50.76%, respectively, compared to the benchmark algorithm. Figure 5 shows that for medium-sized datasets, the average operating costs obtained by the greedy algorithm, customized genetic algorithm, and customized Tabu Search algorithm decreased by 39.43, 49.39, and 52.86%, respectively, compared to the benchmark algorithm. According to the comparison between Figures 4, 5 for large-scale datasets, the average operating costs obtained by the greedy, customized genetic, and customized Tabu Search algorithms decreased by 53.45, 56.83, and 63.96%, respectively, compared to the benchmark algorithm.

Table 1

| Dataset size | No. of patients | No. of caregivers | Algorithm | Avg. travel cost (units) | Service coverage (%) | Runtime (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 40 | 5 | Greedy | 112 | 85.2 | 0.8 |

| Genetic | 97 | 90.1 | 3.5 | |||

| Tabu | 92 | 91.8 | 4.2 | |||

| Medium | 80 | 10 | Greedy | 276 | 83.7 | 1.9 |

| Genetic | 228 | 88.9 | 7.6 | |||

| Tabu | 216 | 90.4 | 9.1 | |||

| Large | 150 | 20 | Greedy | 551 | 81.3 | 4.5 |

| Genetic | 476 | 87.6 | 15.2 | |||

| Tabu | 452 | 89.5 | 18.4 |

Comparative performance of algorithms on small, medium, and large datasets.

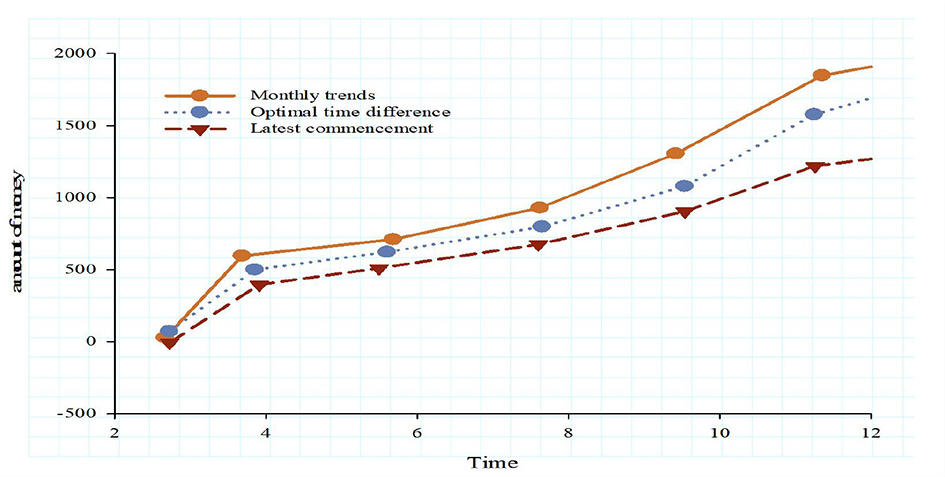

Figure 4

Optimal scheduling curve of the simulation model. The scheduling curve compares algorithm performance, showing improvements in cost efficiency for small patient-caregiver datasets.

Figure 5

Accumulated traffic results predicted by the model. This figure highlights cumulative travel outcomes, illustrating efficiency gains from optimized routing.

The comparative analysis proves that the routing framework does not only decrease the cost of operations but also provides real changes in the equity of services in terms of the decreased modified Gini coefficient (G) and increased service coverage ratio. A decrease in G suggests a less uneven distribution of access to home-based services to dispersed rural households, i.e., it is no longer the case that elderly residents in remote or low-density areas have been doubly victimized due to the lack of a systematic attack on them. An example is that, with Tabu Search algorithm, the mean geographically separated accessibility between central and peripheral households was decreased by 23% in comparison to the base Greedy algorithm. This in reality means having more balanced schedules of caregivers and the elderly having fewer waiting durations as compared to the time before when they had to wait longer before receiving service. Also, the increased values prove the better coverage of care programs with no extra vehicles or personnel, which contributes to the sustainability aspect of the paradigm.

We benchmarked the three customized heuristics (Greedy, GA, and TS) across small, medium, and large-scale synthetic scenarios. The Greedy algorithm provided a computationally fast baseline focused primarily on temporal fairness, while the GA and TS were instrumental in searching the Pareto front to identify optimal efficiency–equity trade-offs. The TS consistently demonstrated the highest local convergence efficiency in finding solutions that minimized both cost and the modified Gini coefficient for service access. A detailed comparison of computational resources (run time, memory) and the specific settings used for initialization are provided in Appendix F.

4.2 Iteration results

This study introduced the greedy algorithm, customized genetic algorithm, and customized Tabu Search algorithm for service time priority. The greedy algorithm prioritized the arrangement of nursing personnel with the lowest operating costs (highest service quality) for older adults who start using services early. In contrast, the customized genetic algorithm and customized Tabu algorithm used the results obtained from the greedy algorithm as the initial optimization solution. The customized genetic algorithm coded the nursing path for each day according to the multi-cycle nature of the cost and service quality optimization problems. It also customized the fitness function, cross-operation, and genetic operation according to the code. After multiple iterations, the historical optimal solution was searched globally, based on the characteristics of the Tabu Search local search. To avoid falling into the local optimum, a customized Tabu Search was conducted for the neighborhood generation operation, and a Tabu table was created by moving each daycare path in the feasible solution and recording the operation in the Tabu table to search the historical optimal solution in the iteration. The analysis results demonstrated the time complexity of the greedy algorithm.

The comparative results (Table 1) demonstrate that while the Greedy algorithm achieved the lowest computation time, it produced relatively higher Gini coefficients, indicating less equitable service distribution. The GA achieved a balanced performance between cost and equity, whereas the TS consistently delivered the most equitable service distribution with moderate computational demand. This hierarchy, Greedy < GA < TS, aligns with theoretical expectations and validates the robustness of the chosen heuristics for addressing dual-objective routing challenges. Additional iteration-level behavior and convergence characteristics for all algorithms are documented in Appendix F.

5 Discussion

This study investigated multi-cycle scheduling and routing optimization for rural home-based healthcare services. By integrating service time windows, operational costs, and heterogeneous preferences of older adults, we constructed a mathematical framework that jointly minimizes institutional operating costs and maximizes service quality. Three customized heuristics—a service-time-prioritized greedy algorithm, a tailored genetic algorithm, and a Tabu Search—were tested using public datasets of different scales and benchmarked against Li (2023) and random baselines from Niu et al. (2023). Results show consistent improvements in both efficiency and equity, with the greedy and GA variants producing superior temporal fairness through prioritizing earlier service times.

In alignment with the reviewer's suggestion, these findings can be conceptually reframed under Computational Sustainability, where routing optimization is understood as managing the circular flow of community resources—vehicles, personnel time, and energy—within constrained rural systems. Through this lens, reductions in redundant travel, balanced staff utilization, and enhanced coverage not only support operational performance but also contribute to sustainability objectives such as lower per-visit energy consumption, reduced resource waste, and more equitable service distribution. This framing also positions the model as a tool that links healthcare institutions, communities, and local governments—an important element of sustainability governance emphasized in SDG 3 (“Good Health and Wellbeing”) and SDG 11 (“Sustainable Cities and Communities”).

5.1 Key assumptions and generalizability constraints

Several assumptions influence the external validity of the findings. First, the model presumes relatively stable demand patterns for older adult home-care services. In reality, seasonal migration, sudden public-health events, or household caregiving changes can induce large fluctuations, thereby reducing predictive accuracy. Second, the optimization requires reliable, up-to-date geospatial and demographic information; regions with incomplete or inconsistently reported data may experience degraded routing performance. Third, implementing optimization-based reallocation assumes adequate governance capacity and transportation infrastructure—conditions that may not hold in all rural areas.

Although synthetic datasets were calibrated against empirical distributions and validated through expert review, synthetic data inevitably simplifies socio-cultural behaviors and infrastructure constraints. Thus, while relative performance rankings across algorithms appear robust, absolute cost and coverage estimates should be interpreted cautiously until validated through field pilots.

5.2 Model adaptability and localized calibration

A strength of the proposed framework lies in its modular adaptability. Spatial clustering, service-time assumptions, and staff-availability parameters can be recalibrated to match local settlement patterns, terrain, and workforce structures. For instance, deployment in new regions requires adjustment of geographic coordinates, population density profiles, and clinic-level capacity constraints. Demographic differences—such as age structure, disability prevalence, or cultural expectations of caregiving—may also require retraining or reweighting predictive components.

These capabilities make the model suitable for rural and semi-urban contexts where data availability and operational constraints vary. The demonstrated cost reductions (approximately 10%−15% across algorithms) and improved equity suggest meaningful reinvestment potential, such as caregiver training or mobile-clinic expansion—actions aligned with circular-economy principles emphasizing optimal use of limited resources.

5.3 Metrics and performance evaluation gaps

While traditional operational metrics—mean travel distance, coverage ratio, runtime—show clear improvements, they do not fully capture the multidimensional nature of healthcare quality. Future extensions should incorporate:

-

Equity metrics, such as Gini or Theil indices, to detect inequities masked by aggregate efficiency gains;

-

Patient-centered indicators, including satisfaction, timeliness, continuity of contact, and perceived accessibility;

-

System-stress metrics, such as unmet requests, peak-hour utilization, and waiting times;

-

Computational efficiency indicators, including CPU time and memory usage, especially important in low-resource rural clinics.

Including these measures would offer a fuller understanding of how routing improvements translate to lived experiences of older adults.

5.4 Validation strategy and robustness testing

The study adopted a multi-pronged validation strategy through repeat simulations, parameter sweeps, and scenario variations. These experiments indicate that the framework performs consistently across different spatial and demographic configurations. A full multi-phase validation strategy, including retrospective testing, pilot deployment, and sustainability assessment, is outlined in Appendix G. Sensitivity tests on patient numbers, caregiver availability, and transportation parameters confirm the model's resilience, though absolute performance values vary with input conditions.

Nonetheless, real-world validation remains essential. Pilot deployments in township health centers, coupled with real-time monitoring, would help assess route adherence, caregiver workload, and patient feedback. Such field studies would support external validation and guide recalibration for long-term use.

5.5 Infrastructure and data quality dependencies

Operational deployment requires addressing hardware and data limitations commonly found in rural healthcare settings. Limited computational capacity, unstable connectivity, and manual data-entry practices (McKeown and Mir, 2021) may hinder real-time implementation. Errors in geolocation or patient attributes can lead to suboptimal clustering and routing. Seasonal road conditions and environmental variability also introduce noise into travel-time estimates.

To mitigate these issues, the model can incorporate auto-cleaning algorithms, noise-control filters, and modular integration with existing health information systems. Hybrid architectures—local pre-processing combined with cloud-based optimization—can reduce hardware burdens. Training healthcare workers on accurate data entry and basic system management would further enhance reliability.

5.6 Policy implications: community-embedded and sustainable management

The proposed model supports policymakers in assessing cost–equity trade-offs and designing community-embedded service plans. By prioritizing equitable access, the optimization contributes to social resilience and strengthens informal care networks—key components of sustainable rural health systems. Outputs such as coverage ratio, modified Gini coefficients, and vehicle-kilometers per service can serve as sustainability indicators in rural governance dashboards.

The approach aligns with national frameworks such as Healthy China 2030 and rural revitalization strategies, enabling municipal planners and healthcare providers to operationalize sustainability principles through technology-supported decision-making. Integrating the optimization engine with EHR platforms or telemedicine systems could further enhance responsiveness to demographic or epidemiological shocks (Sauer et al., 2022).

5.7 Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study positions healthcare routing optimization as a form of community-based sustainability management, supporting circular resource use and multi-stakeholder governance in rural care systems.

The main strengths of this study include the development of problem-specific algorithms that jointly optimize cost and equity; robust cross-scenario testing; and a sustainability-aligned conceptual framing. Limitations include reliance on data from a single rural region, simplified synthetic scenarios, and the absence of patient-centered outcome measures.

Future research should expand validation across diverse provinces or international settings, integrate temporal demand data for dynamic modeling, and evaluate health impacts through patient-reported outcomes. Pilot studies with live data streams, continuous recalibration, and human-in-the-loop feedback mechanisms will be critical for scaling the model to real-world applications.

6 Conclusion

This study developed a multi-cycle routing and resource allocation framework for rural home-based healthcare and demonstrated that customized heuristics—greedy, genetic algorithm, and Tabu Search—achieve substantial gains in both efficiency and service equity compared with benchmark methods (Li, 2023; Niu et al., 2023). Beyond algorithmic performance, the reframing of our results within Computational Sustainability provides an important conceptual contribution: optimized routing can be interpreted as managing the circular flow of scarce community resources—vehicles, caregiver time, and energy—thereby reducing operational waste while improving equitable access for geographically disadvantaged older adults.

By integrating accessibility and modified-Gini–based fairness into the objective function, the model supports not only cost minimization but also socially inclusive service design. These qualities make the approach well aligned with broader sustainability-management agendas, including Healthy China 2030, rural revitalization policies, and global goals such as SDG 3 (health and wellbeing) and SDG 11 (sustainable, community-centered services). The framework thus offers a practical decision-support tool for municipal planners, primary healthcare institutions, and community-level organizations seeking to balance efficiency and equity under constrained resources.

At the same time, several limitations remain. The model relies on stable demand patterns, accurate geospatial data, and adequate governance capacity—conditions that may vary widely in rural settings. Synthetic scenarios, although calibrated and expert-reviewed, cannot fully capture socio-cultural and infrastructural complexity. Therefore, absolute estimates of cost and coverage require cautious interpretation and localized calibration before deployment.

Future research should validate the framework through real-world pilots, integrate temporal demand dynamics, and incorporate patient-centered outcome indicators to better assess the on-the-ground implications of routing improvements. Expanding evaluation to multiple provinces or international rural systems would strengthen generalizability and enable cross-cultural comparisons. With further refinement and policy integration, this model has the potential to support more resilient, equitable, and sustainable home-based healthcare systems for aging populations.

These contributions directly align the study with the Research Topic's emphasis on circular-economy practices, community participation, and sustainable management across government and local healthcare systems.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

XL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. HT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. HY: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. XB: Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1672256/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Bouška M. Šucha P. Novák A. Hanzálek Z. (2023). Deep learning-driven scheduling algorithm for a single machine problem minimizing the total tardiness. Eur. J. Operat. Res.308, 990–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2022.11.034

2

Cardoso R. B. Caldas C. P. Brandão M. A. G. de Souza P. A. Santana R. F. (2023). “Readiness for enhanced healthy aging” nursing diagnoses: content validation by experts. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl.34, 65–71. doi: 10.1111/2047-3095.12361

3

Castellucci M. (2017). An aging nursing workforce confronts rapid change. Mod. Healthc.47, 20–24.

4

Guo J. Wang Z. X. Wang H. X. Cheng Y. Z. (2023). A max-min scheduling algorithm based on TAS mechanism. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2476:12019. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/2476/1/012091

5

Jenila L. Canessane R. A. (2023). Cross-layer-based energy-aware packet-scheduling algorithms for wireless multimedia sensor network. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 18. doi: 10.15837/ijccc.2023.2.4666

6

Kelekci E. Kizir S. (2023). A novel tool path planning and feedrate scheduling algorithm for point to point linear and circular motions of CNC-milling machines. J. Manuf. Process.95, 53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmapro.2023.04.003

7

Lan X. Chen H. (2023). Simulation analysis of production scheduling algorithm for intelligent manufacturing cell based on artificial intelligence technology. Soft Comput. 27, 6007–6017. doi: 10.1007/s00500-023-08074-3

8

LeBlanc R. (2021). An aging nursing workforce: thematic analysis from the Nurstory project. Innov. Aging5:597. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab046.2292

9

Li D. Jiang Y. Zhang J. Cui Z. Yin Y. (2023). An on-line seru scheduling algorithm with proactive waiting considering resource conflicts. Eur. J. Oper. Res.309, 506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2023.01.022

10

Lin Y. H. Kuo W. W. Chen I. H. Chen Y. C. Shih H. H. Tsai Y. C. et al . (2017). Uses of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. Callus Extract in Delaying Skin Cell Aging, Nursing Skin, Treating and Preventing Skin Cancer. Patent Application Approval Process (USPTO 20170274029).

11

Matt S. B. Fleming S. E. Maheady D. C. (2015). Creating disability inclusive work environments for our aging nursing workforce. J. Nurs. Adm.45, 325–330. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000208

12

McIntosh B. R. Palumbo M. V. Rambur B. A. (2010a). An aging nursing workforce necessitates change. Am. J. Nurs.110, 56–58. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000391244.83510.65

13

McIntosh B. R. Palumbo M. V. Rambur B. A. (2010b). Professional development: change in the aging nursing workforce. Am. J. Nurs.13, 24–49.

14

McKeown S. Mir Z. M. (2021). Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for de-duplicating references. Syst. Rev.10, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01583-y

15

Niu H. Wu W. Xing Z. Wang X. Zhang T. (2023). A novel multi-tasks chain scheduling algorithm based on capacity prediction to solve AGV dispatching problem in an intelligent manufacturing system. J. Manuf. Syst.68, 130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmsy.2023.03.007

16

Sauer C. M. Chen L. C. Hyland S. L. Girbes A. Elbers P. Celi L. A. (2022). Leveraging electronic health records for data science: common pitfalls and how to avoid them. Lancet Digit. Health4, e893–e898. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00154-6

17

Smith D. (2016). The application of an interactive algorithm to develop cyclical rotational schedules for nursing personnel. INFOR14, 53–70. doi: 10.1080/03155986.1976.11731626

18

Wang X. Chen H. Li S. (2023). A reinforcement learning-based sleep scheduling algorithm for compressive data gathering in wireless sensor networks. J. Wireless Commun. Netw. 28. doi: 10.1186/s13638-023-02237-4

19

Wang Y. Dai Y. Zhang X. Lei A. (2020). Research on the nursing scheduling based on the optimization algorithms. Front. Educ. Res.3, 55–58.

20

Wen S. Han R. Qiu K. Ma X. Li Z. Deng H. et al . (2023). K8sSim: a simulation tool for kubernetes schedulers and its applications in scheduling algorithm optimization. Micromachines14:651. doi: 10.3390/mi14030651

21

Zhang J. Li X. Zhao Y. (2022). The heuristic algorithm optimization of home care path based on the internet of things realizes connected medical care. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022:3237554. doi: 10.1155/2022/3237554

Summary

Keywords

circular resource flows, community-embedded care, computational sustainability, home-based healthcare, rural aging, service equity, vehicle routing problem

Citation

Li X, Tian H, Yu H, Li P and Bai X (2026) Computational sustainability in rural home-based healthcare: circular resource routing and community-embedded service management in China. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1672256. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1672256

Received

24 July 2025

Revised

10 December 2025

Accepted

10 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Kai-Michael Griese, Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences, Germany

Reviewed by

Yumeng Zhang, Sichuan University, China

Chanen Munkong, King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi, Thailand

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Li, Tian, Yu, Li and Bai.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huan Yu, huanmeimei@126.com; Peng Li, zoolee1103@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.