Abstract

Introduction:

This study investigates the adoption levels of regenerative architecture principles in selected wellness facilities in Abuja, Nigeria, to identify opportunities for promoting regenerative architecture. This study addressed two key objectives: to analyse the physical architectural features of these selected facilities, and to identify the regenerative architecture principles adopted in these facilities.

Methods:

A structured multiple-case observation guide/checklist was employed to systematically examine key regenerative design features across three wellness facilities in Abuja. Seven regenerative architecture principles—Place, Water, Energy, Health & Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Costs—were utilised to develop a structured checklist. Each indicator received a score between 0 and 3, with a maximum score of 84 per facility.

Results:

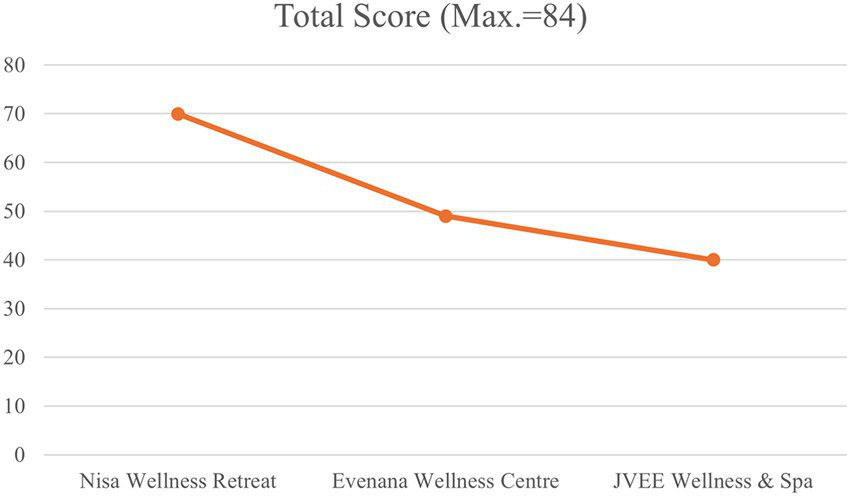

The findings reveal varying degrees of adoption across various facilities. Nisa Wellness Retreat achieved the highest implementation score (70/84), Evenana Wellness Centre demonstrated moderate adoption (49/84), while JVEE Wellness and Spa exhibited the lowest adoption (40/84). Across all three facilities, water management systems were the weakest domain, whereas Place, Materials and Equity revealed a relatively consistent adoption.

Discussion:

The study identifies significant areas for improvement for built environment professionals seeking to enhance the adoption of regenerative design in wellness facilities within the Nigerian context. In addition to establishing a scientific baseline for the adoption of regenerative architecture in Abuja’s wellness industry, the study provides designers, operators, and policymakers with a replicable framework for assessment.

1 Introduction

Regenerative architecture transcends conventional boundaries by combining multiple disciplines in an experimental manner, developing theoretical and practical breakthroughs such as new building systems, tools, and technologies to promote environmental sustainability. This entails restoring the natural world by rejuvenating communities, repairing harmed ecosystems, restoring soil health, and cleaning up polluted areas, as we carry out our daily activities (Armstrong, 2023; Sholanke and Nwangwu, 2025). In wellness-focused structures such as hotels, resorts, and retreats, where visitors seek rest, renewal, and a closer connection with nature, this integration has been especially important (Chi et al., 2019). Additionally, the need to reconsider conventional architectural approaches is growing as the effects of global climate change intensify (Aduwo et al., 2024). Regenerative architecture makes more contributions to the environment over a building’s lifetime than it does during construction and operation, with the goal of leaving a positive environmental impact on the site, rather than designing a project with the least amount of impact possible (Lucchi, 2023; Petrovski et al., 2021). Consequently, contemporary architectural practice must prioritise human comfort while actively contributing to long-term sustainability (Tabassum and Park, 2024). Architects and designers are reimagining how physical environments can support holistic well-being while fostering ecological resilience and sustainability by integrating regenerative ideas into wellness spaces (Stamenković et al., 2018).

Wellness, as defined by the WHO, is the “ideal or optimal state of health for individuals and communities.” It is regarded as the notion of possessing holistic physical and emotional health. It is considered to involve continuously making health-conscious choices to attain optimal health in all areas of life (Sood and Gupta, 2024).

Integrating the functions of the hospitality and healthcare sectors has also become a well-acknowledged phenomenon in the built environment (Zhao and He, 2024). In his book, “The New Wellness Revolution,” Pilzer (2007) predicted that “wellness is the next big thing,” and that prediction did not delay in coming true. The wellness market is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 6.4% between 2021 and 2025, reaching a value of $123.2 billion by 2025, according to Global Wellness Institute (2024). Many hotels, particularly spa hotels, offer wellness experience programs as part of their offerings, as post-COVID-19 customers are prioritising their health and well-being and are increasingly seeking out wellness experiences (Dimitrovski et al., 2024).

Although numerous studies provide significant information on the evaluation criteria for wellness facilities, there is limited information on how RAPs can be effectively incorporated into the design. Existing literature needs to evolve into the strategic application of RAPs within the context of wellness spaces. There is also a significant locational gap, as most research on wellness in the hospitality sector is unavailable for regions such as Abuja, Nigeria. Considering Nigeria’s climate and culture, the potential benefits of regenerative design within wellness spaces underscore the significance of this research problem.

Adoption in this study is defined analytically as the consistent use of regenerative architectural concepts in wellness facilities, as well as their observable presence and functional quality. A systematic observation-based framework that assesses both design intent and operational effectiveness across several regeneration principles is used to evaluate adoption at the building scale.

The overall aim of this study is to assess the adoption levels of RAPs in selected wellness facilities in Abuja, Nigeria, to identify opportunities for promoting regenerative architecture. This aim was achieved by analysing the physical architectural features of these selected facilities and identifying the regenerative architecture principles adopted in these facilities.

To achieve these objectives, the paper employs an observational approach across three wellness facilities in Abuja. Section 2 outlines the conceptual framework and operationalised RAPs used for the assessment. Section 3 highlights the materials, methods and scoring procedure. Section 4 presents a report on the case study assessments, followed by an in-depth discussion of the findings’ implications in Section 5. This study concludes with relevant recommendations for designers, facility operators, and policymakers in Section 6.

2 Literature review and conceptual framework

2.1 Regenerative architecture principles

Green building designs aim to mitigate negative environmental challenges; however, they are often deemed inadequate in addressing complex, interwoven unsustainable practices, highlighting the need for a more regenerative approach (Adewale et al., 2025). Although sustainability is based on three pillars—economic, social, and environmental—the majority of green architecture techniques neglect this holistic framework. LEED and other building rating systems primarily only incorporate energy efficiency and environmental metrics, assessing buildings according to how their construction, design, and operation minimise ecological effect through conservation measures (Fahmy et al., 2019). However, to close the gap between current practices and ideal solutions, the Living Building Challenge, introduced in 2006, goes beyond traditional sustainability indicators. Envisioning a future in which architecture actively restores ecosystems while fostering cultural richness and social justice, this extensive certification program is a transformative instrument for all building scales (Hassan, 2016).

This study evaluates the adoption of regenerative architecture by applying the seven LBC principles derived from established regenerative design and performance-based sustainability frameworks. Developed by the International Living Future Institute, the Living Building Challenge (LBC) is one of the most rigorous and extensive green construction certifications in the world. It goes beyond environmental sustainability to incorporate social and economic responsibilities in building design. Its peculiarities are rooted in its demand for active contribution to creating a healthier and more resilient environment, while minimising the carbon footprint on the environment. The LBC curated seven “petals” that a building must achieve continuously for a duration of 12 months for it to be eligible for the certificate and be regarded as a “Living Building.” The seven “petals” are Place, Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity and Cost (Mattar et al., n.d.).

The regenerative architecture principles and their core descriptions were adopted from the operational framework proposed by Mattar et al. (n.d.). However, the specific indicators used to assess adoption within wellness facilities were developed by the authors through a synthesis of diverse regenerative and wellness-oriented design studies, with contextual adaptation to the Abuja setting. This approach enables the study to maintain conceptual consistency with established regenerative frameworks while allowing for context-specific and function-sensitive assessments at the facility scale.

Table 1 presents the seven RAPs, their operational descriptions, and the indicators developed for observational assessment in this study.

Table 1

| RAPs | Description | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Place | A mutually supportive relationship between people and natural systems, with emphasis on human-scaled, low-impact modes of living |

|

| Water | Building operations are designed to function within the limits of the local climate conditions, rather than exceeding available water resources |

|

| Energy | Energy strategies extend beyond dependence on solar input alone, aiming instead for environments that generate more energy than they consume |

|

| Health & Happiness | Design decisions are directed toward improving both the physical comfort and psychological well-being of building users |

|

| Materials | Materials and systems are selected to minimise harm across ecosystems, while promoting waste cycles that result in positive environmental outcomes |

|

| Equity | Architecture is positioned as an active contributor to social equity by ensuring inclusive access to nature, space, and place for diverse users. |

|

| Cost | Greater emphasis is placed on long-term operational performance and life-cycle efficiency rather than focusing only on upfront construction costs |

|

Operationalisation of variables.

2.2 Regenerative architecture performance assessment

Based on the criteria defined above, performance in this study is related to the presence and quality of RAPs within each facility, as measured through observable and verifiable evidence.

The study also adopted a 0–3 scoring system as follows:

0—Not present.

1—Minimally present (basic compliance).

2—Moderately present (functional implementation).

3—Fully present (high-quality regenerative integration).

This scoring system yields a maximum score of 84, based on the evaluation of the 28 indicators outlined above. These indicators are assessed across the three facilities, i.e., 28 × 3 = 84. Each facility’s score represents the extent of regenerative adoption.

To ensure transparency:

All indicators were assigned equal weight.

Traceability from principle → indicator → score is maintained.

Thresholds were established as:

-

0–28 = Low adoption

-

29–56 = Moderate adoption

-

57–84 = High adoption

This framework enables cross-case comparison and facilitates replication in future research.

3 Materials and methods

To provide a thorough analysis of the varying adoption levels of regenerative characteristics in the selected wellness facilities in Abuja, Nigeria, the study employed a qualitative data collection approach. A multi-case observational approach was adopted because RAPs are primarily physical, spatial, and operational, and can therefore be assessed visually and documented. Due to Abuja’s rapidly expanding wellness sector and emphasis on sustainable building development, it was selected as the locational context of this investigation. The authors used non-intrusive direct observations, a systematic checklist, and photographic documentation to gather data between December 2024 and January 2025. Three wellness facilities were selected as case studies to facilitate comparative research and identify variations in scale, typology, and design approach. A 0–3 rating system was used to assess the RAPs’ adoption levels, enabling comparisons between the three facilities and regenerative principles.

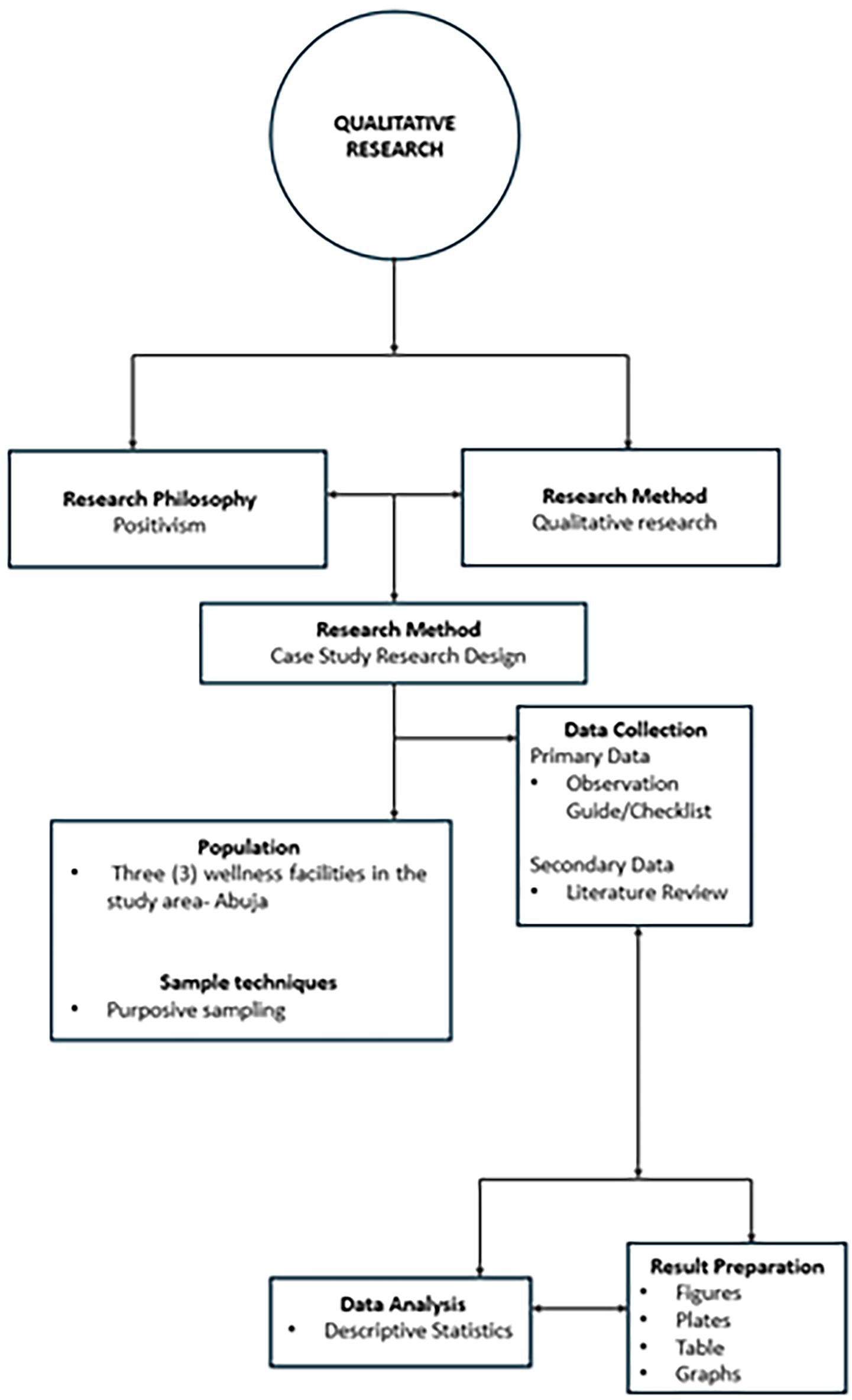

Figure 1 is a flowchart summarising the methodological approach of the study.

Figure 1

Structure of the research methodology.

The following objectives will achieve this aim;

-

To ascertain the physical architectural features of these selected facilities

-

To identify the regenerative architecture principles adopted in these facilities.

3.1 Case study selection

The primary objective of this study is to assess the application of RAPs in wellness-focused environments in Abuja. Hence, the case study selection prioritised wellness facilities and wellness hotels situated within the geographical scope of the study. These facilities were selected because they are most suited to the research’s aim of investigating how RAPs influence user well-being in wellness spaces. Priority was given to wellness facilities in the selection phase due to their notable incorporation of natural elements in their wellness spaces. Presently, there are two known wellness facilities in Abuja, and both facilities were initially selected through purposive sampling due to their relevance to the research objectives. However, due to access limitations and institutional permissions, only one facility was used for this research. Two additional wellness facilities were randomly selected from a list of wellness centres commissioned within the last 5 years, forming the total sample size of the study. This was done to facilitate an in-depth and more comprehensive result findings on the study focus, as well as avoid bias and subjectivity. All selected facilities are located within the urban, mixed-use zones in Abuja, popular for its numerous hospitality and wellness services. This provided a strategic context for analysis due to its urban nature, zoning regulations and significance to the intended facility type, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| S/N | Wellness facilities | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nisa Wellness Retreat | British Village, 14 Ejigbo CL., Wuse 2, Abuja 904,101, Federal Capital Territory |

| 2 | JVEE Wellness and Spa | 3 Kumasi Cres, Wuse 2, Abuja 900,288, Federal Capital Territory |

| 3 | Evenana Wellness Centre | Franca Afegbua Cres, Gudu, Abuja 900,110, Federal Capital Territory |

The wellness facilities and their locations.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

3.2 Data collection and analysis

Data used in this study were obtained from both primary and secondary sources. An in-depth checklist, developed from the tenets of regenerative architecture as postulated by Mattar et al. (n.d.), comprised the primary data source of this study. A digital camera was also used to gather data from the field, accompanying the documentation of RAPs implemented in these facilities.

The data from the study were analysed using descriptive quantitative analysis, comparing scores across each wellness facility to examine the similarities and differences in the adoption of RAPs. The data were content analysed, and the results were reported descriptively using tables and photographic images. When gathering and using data, ethical considerations were prioritised. Following a thorough explanation of the research’s objectives, the management of the three wellness facilities voluntarily consented to the collection of data within their facilities. The data were used solely for the purpose of the study (Table 3).

Table 3

| Facility | Total score (Max. = 84) | Threshold band |

|---|---|---|

| Nisa Wellness Retreat | 70 | High |

| Evenana Wellness Centre | 49 | Moderate |

| JVEE Wellness and Spa | 40 | Moderate (Lower bound) |

Facility-level regenerative adoption scores.

The field data for the analysis were gathered during the months of December 2024 and January 2025.

3.3 Scoring and assessment

Each indicator was scored on a 0–3 scale, as described earlier. Non-applicable indicators were excluded from the denominator, though all indicators were applicable in this study.

3.4 Reliability and data quality

Although observations were conducted by a single researcher, a checklist was used in one of the facilities to carry out a pilot study aimed at improving indicator clarity and scoring consistency. This process strengthened the internal coherence of the assessment tool. Future studies involving multiple assessors could further examine inter-rater reliability using standard agreement metrics.

3.5 Ethical considerations

In this study, a few wellness centres in Abuja, Nigeria, were observed in the field, and their architecture was documented. This study did not involve any human subjects, animals, biological samples, or experiments of any kind. Each facility’s management allowed access to the buildings and premises. At each location, authorisation was acquired from authorised staff to conduct non-intrusive visual assessments and take photographs. During the course of the investigation, no protected species were seen or sampled, and no parts of animal husbandry, care, or experimentation were applied.

4 Results

The study investigated the physical architectural features and RAPs adopted in the selected wellness facilities, and the findings are presented this section.

The study’s first objective is to ascertain the physical architectural features of the selected facilities. To achieve this objective, several key concepts were examined under each facility, namely, the building overview, site layout, building description, and spatial organisation and analysis. These descriptive findings provide a solid baseline against which the adoption levels of identified RAPs can be effectively assessed, which is the second objective. From this comprehensive overview, the presence or absence of specific context-based RAPs are identified, in section 5, as well as the subsequent gaps and opportunities for better sustainability outcomes in such institutions.

Table 4 summarises facility-level regenerative adoption scores and corresponding adoption bands based on the predefined threshold ranges.

Table 4

| S/N | Principles | Present | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (0) | Low (Armstrong, 2023) | Moderate (Sholanke and Nwangwu, 2025) | High (Chi et al., 2019) | ||

| A. Place | |||||

| 1 | Use of native or adapted vegetation | * | |||

| 2 | Site selection minimises environmental impact | * | |||

| 3 | The design promotes access to outdoor views and natural surroundings | * | |||

| 4 | Integration with the surrounding community | * | |||

| B. Water | |||||

| 5 | Rainwater harvesting systems | * | |||

| 6 | Greywater recycling systems | * | |||

| 7 | Low-flow or water-efficient plumbing fixtures | * | |||

| 8 | Visible water features enhancing user experience (e.g., fountains, pools) | * | |||

| C. Energy | |||||

| 9 | Use of renewable energy systems | * | |||

| 10 | Smart energy management systems (e.g., motion sensors, automated controls) | * | |||

| 11 | Passive design features for natural lighting and ventilation | * | |||

| 12 | Efficient use of energy-saving lighting systems | * | |||

| D. Health and Happiness | |||||

| 13 | Presence of green spaces (e.g., gardens, courtyards) | * | |||

| 14 | Access to natural lighting in user areas | * | |||

| 15 | Acoustic measures to enhance comfort | * | |||

| 16 | The design encourages physical activity (e.g., walking paths, stairs) | * | |||

| E. Materials | |||||

| 17 | Use of recycled or upcycled building materials | * | |||

| 18 | Locally sourced materials to reduce transportation impacts | * | |||

| 19 | Non-toxic materials for interior finishes | * | |||

| 20 | Durability and adaptability of materials to environmental conditions | * | |||

| F. Equity | |||||

| 21 | Inclusive design features (e.g., ramps, elevators, braille signage) | * | |||

| 22 | The design promotes equitable access to amenities for all users | * | |||

| 23 | Spaces encourage community interaction and social cohesion | * | |||

| 24 | Staff facilities and workspaces are designed for comfort and efficiency | * | |||

| G. Costs | |||||

| 25 | Evidence of cost-efficient energy and water systems | * | |||

| 26 | Long-term operational cost savings from sustainable design features | * | |||

| 27 | Investment in high-quality, durable materials for cost savings over time | * | |||

| 28 | Visible efforts to balance user affordability with luxury and wellness offerings | * | |||

| Total | 70 | ||||

Identification of regenerative architecture principles in Nisa Wellness Centre.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

Table 5

| S/N | Principles | Present | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (0) | Low (Armstrong, 2023) | Moderate (Sholanke and Nwangwu, 2025) | High (Chi et al., 2019) | ||

| A. Place | |||||

| 1 | Use of native or adapted vegetation | * | |||

| 2 | Site selection minimises environmental impact | * | |||

| 3 | The design promotes access to outdoor views and natural surroundings | * | |||

| 4 | Integration with the surrounding community | * | |||

| B. Water | |||||

| 5 | Rainwater harvesting systems | * | |||

| 6 | Greywater recycling systems | * | |||

| 7 | Low-flow or water-efficient plumbing fixtures | * | |||

| 8 | Visible water features enhancing user experience (e.g., fountains, pools) | * | |||

| C. Energy | |||||

| 9 | Use of renewable energy systems | * | |||

| 10 | Smart energy management systems (e.g., motion sensors, automated controls) | * | |||

| 11 | Passive design features for natural lighting and ventilation | * | |||

| 12 | Efficient use of energy-saving lighting systems | * | |||

| D. Health and Happiness | |||||

| 13 | Presence of green spaces (e.g., gardens, courtyards) | * | |||

| 14 | Access to natural lighting in user areas | * | |||

| 15 | Acoustic measures to enhance comfort | * | |||

| 16 | The design encourages physical activity (e.g., walking paths, stairs) | * | |||

| E. Materials | |||||

| 17 | Use of recycled or upcycled building materials | * | |||

| 18 | Locally sourced materials to reduce transportation impacts | * | |||

| 19 | Non-toxic materials for interior finishes | * | |||

| 20 | Durability and adaptability of materials to environmental conditions | * | |||

| F. Equity | |||||

| 21 | Inclusive design features (e.g., ramps, elevators, braille signage) | * | |||

| 22 | The design promotes equitable access to amenities for all users | * | |||

| 23 | Spaces encourage community interaction and social cohesion | * | |||

| 24 | Staff facilities and workspaces are designed for comfort and efficiency | * | |||

| G. Costs | |||||

| 25 | Evidence of cost-efficient energy and water systems | * | |||

| 26 | Long-term operational cost savings from sustainable design features | * | |||

| 27 | Investment in high-quality, durable materials for cost savings over time | * | |||

| 28 | Visible efforts to balance user affordability with luxury and wellness offerings | * | |||

| Total | 40 | ||||

Identification of regenerative architecture principles in Jvee Wellness and Spa.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

4.1 Case study 1: Nisa Wellness Retreat, Abuja

Location: British Village, 14 Ejigbo CL., Wuse 2, Abuja 904,101, Federal Capital Territory.

4.1.1 Building overview

The Nisa Wellness Retreat, one of the few wellness-themed hotels in Abuja and in Nigeria, represents a unique approach to hospitality and well-being. The design responds to Abuja’s tropical climate, offering a serene, nature-infused environment for healing and wellness activities. It is located within the medical district in one of Abuja’s most developed central locations, thereby offering the advantage of close proximity to other medical facilities. This district is also in close proximity to a high-end residential district, thereby contributing to the local wellness economy in that area and in Abuja as a whole. Figure 2 illustrates the welcoming and simple exterior design of Nisa Wellness Retreat.

Figure 2

Front view of Nisa Wellness Retreat.

4.1.2 Site layout

Due to the sloping topography of the site, the strategic positioning of the Nisa Wellness Retreat offers stunning, calming views of the surrounding landscape, filled with vegetation, and the cityscape of Abuja. The site layout features abundant vegetation, including trees and shrubs, as shown in Figure 3, offering both ornamental and eco-friendly benefits to the clinic and its users.

Figure 3

Exterior view of Nisa Wellness Retreat showing topography.

4.1.3 Building description

The design of the facility creatively integrates African architecture, expressed in a contemporary manner, with wellness design principles suitable for the urban context in which it is located. The stepped design of the building presents an organic response to the site’s topography, resulting in a series of cascading levels. The building’s exterior is characterised by a clean, cream-coloured finish that expresses a hint of modernism while reflecting the heat of Abuja’s climate. The building also optimises its relationship with the environment by strategically positioning balconies and terraces, as shown in Figure 4. This offers outdoor engagement for the guests while providing shading from the sun for the rooms at lower levels. The roof design features a combination of a pitched roof for the main building and a flat roof for ancillary spaces, including the generator house, bar, and outdoor restaurant.

Figure 4

Outdoor restaurant at Nisa Wellness Retreat.

To successfully execute the stepped design of the facility, retaining concrete walls were utilised, allowing for usable terraced spaces at various elevations. This creates a beautiful landscape around the pool area of the building, as cover vegetation, as opposed to concrete, was used to further enhance the vegetative mass of the area. To cater to the hot climate of Abuja, HVAC systems are implemented in addition to the passive design strategies the building adopts, which include creating large windows and openings in each room. The rear area of the building features an elevated swimming pool surrounded by natural and artificial grass, and overlooking the relaxing view of Abuja’s urban area as shown in Figure 5. A few steps below are the outdoor bars with seating, some fully exposed to the spontaneity of nature and others carefully located to provide guests with a secluded, semi-open lounging space as shown in Figures 6 and 7. The use of wood and unfinished concrete in the interior of certain spaces, juxtaposed with the clean walling of the building, expresses the deliberate fusion of African art and contemporary design. Overall, this building successfully achieves a balanced distribution of indoor and outdoor spaces, benefiting from a more controlled environment while outdoor areas enjoy natural ventilation and captivating views, thereby creating a variety of spatial experiences for users.

Figure 5

Elevated pool at Nisa Wellness Retreat.

Figure 6

Sit-out and bar at Nisa Wellness Retreat.

Figure 7

Outdoor lounge at Nisa Wellness Retreat.

4.1.4 Spatial organisation and analysis

The design of the Nisa Wellness Retreat offers a smooth and easy circulation for visitors and guests. From the entrance of the building to all the spaces, both above ground level and in the basement, this facility is designed to provide an easy wayfinding for its users. Although not immediately apparent from the exterior, the building contains numerous rooms within its structure and several spaces dedicated to wellness activities. In accordance with proper zoning, the wellness areas are restricted to the basement, ground floor, and first floor, while the rooms are located on the upper floors. This ensures that guests are not overstimulated and can be properly guided upon entering the facility. Other spaces, such as the restaurant and offices, are located on what appears to be the ground floor from the reception and entrance, but offer a stunning view of Abuja below due to the site’s sloping topography. This enables the facility to provide two distinct types of spatial experiences for guests using the restaurant.

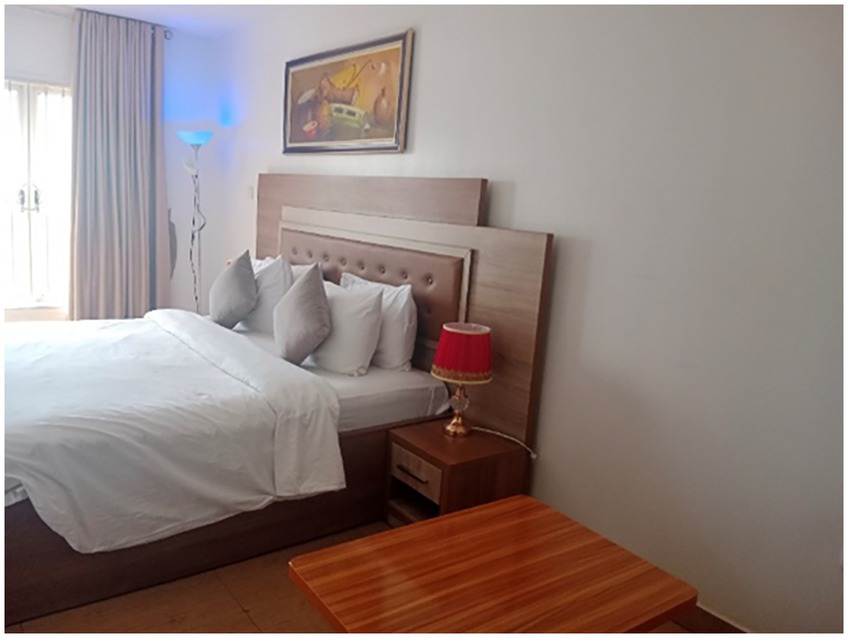

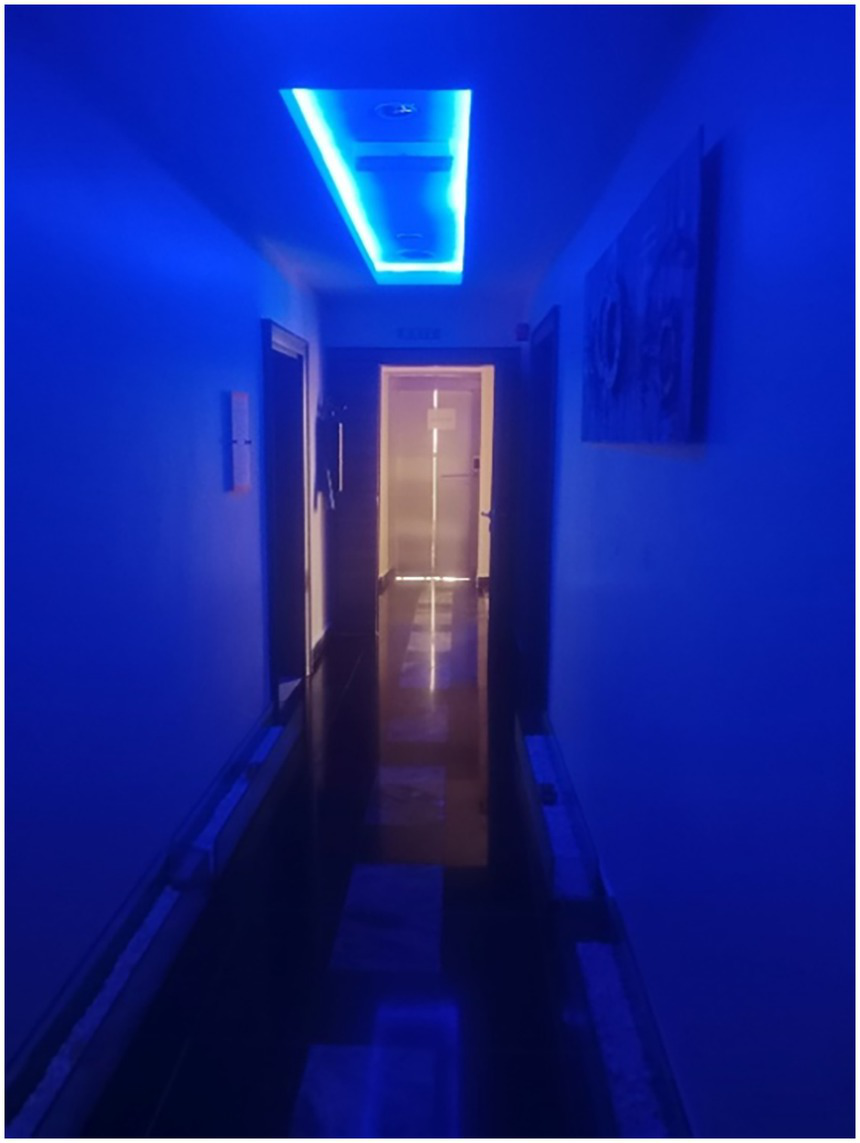

The layout of this facility can be divided into three zones: the public zone, the wellness zone and the private zone. The public zone of Nisa Wellness Retreat comprises of the reception area, administrative offices, dining and restaurant area, the swimming pool, bar and outdoor lounges. The wellness zone comprises the hydrotherapy room, massage room, facial room, steam room, gym, and salon. The private zone consists of the bedrooms, bathrooms, changing room, and kitchen. Figure 8 shows the dining section of the ground floor of the wellness facility. Figure 9 is a blow-out of the different accommodation typologies that the retreat offers, with different sizes, furniture configurations and amenities, also shown in Figure 10. Figure 11 is a depiction of the facilities and services in the wellness area of the retreat. It showcases the spatial organisation of the different massage rooms and wellness spaces, carefully separated by a long, narrow lobby with ambient lighting, as shown in Figure 12. Figure 13 shows the vegetative cover of the steeped landscape from the rear side of the building.

Figure 8

Ground floor plan showing dining area.

Figure 9

Floor plan showing rooms.

Figure 10

Room at Nisa Wellness Retreat.

Figure 11

Floor plan showing wellness spaces.

Figure 12

Wellness area corridor showing ambient lighting.

Figure 13

Vegetative cover of steeped landscape.

4.2 Case study 2: JVEE Wellness and Spa, Abuja

Location: 3 Kumasi Cres, Wuse 2, Abuja 900,288, Federal Capital Territory.

4.2.1 Building overview

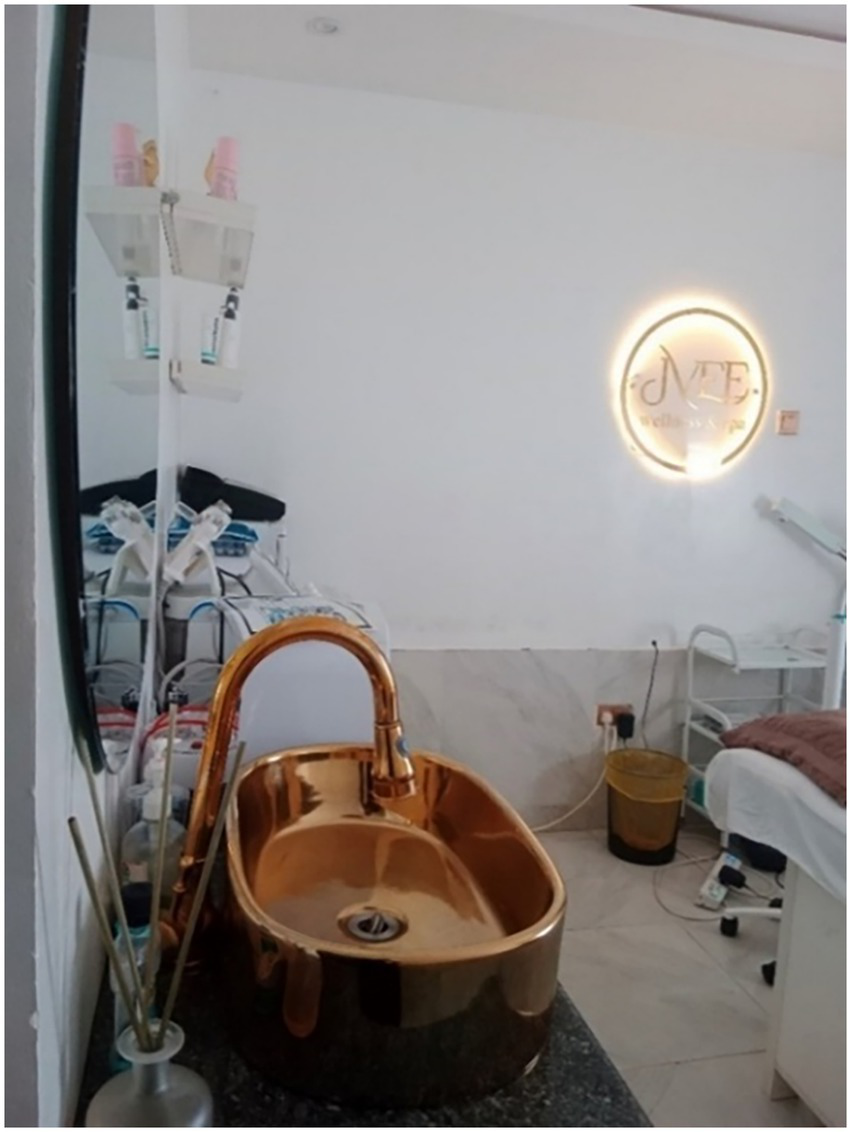

JVEE Wellness and Spa operates within a converted residential building in Wuse 2, Abuja. This main feature demonstrates innovative adaptive reuse of an existing structure, thereby expressing regenerative and sustainable design. The adapted facility embodies the characteristics of typical Nigerian residential architecture, featuring pitched roofs and cream-coloured walls, as shown in Figure 14. However, the spa presents a stark contrast to this façade by incorporating modern design features into its interior, as shown in Figure 15. This inevitably provides a sense of calm and serenity to a user coming in from the seemingly chaotic outdoor space to the tranquil indoor space of JVEE. Due to site and building limitations, the facility maximises its resources to ensure that wellness-themed activities are kept within its envelope. This, therefore, minimises the opportunity to offer outdoor wellness services, but this is made up for by its creative approach to a calming interior space. This is done in various ways: by using technology to create calming nature sounds, by opting for a predominantly beige colour scheme, by using energy-efficient ambient lighting to create a sense of calmness, by maintaining a very pristine indoor air quality both in smell and temperature, by using interior cladding to offer optimal acoustic solutions. The combination of these solutions demonstrates how designers can use technology and innovative material solutions to create wellness spaces, regardless of space constraints. These insights can be highly valuable for designers based in Nigeria who face similar constraints but seek to incorporate certain regenerative design principles in creating wellness spaces.

Figure 14

Exterior view of Jvee Wellness Centre.

Figure 15

Waiting area in Jvee Wellness Centre showing lighting design.

4.2.2 Site layout

The facility is situated within a gated compound in a residential urban area in Abuja. This puts it in close proximity to the residents of that area, thereby enhancing the wellness economy of that zone in Abuja. The site features certain characteristics typical of a high-end residential space in Nigeria. It is surrounded by a secure concrete perimeter wall with decorative metallic gates, and the parking space is paved with interlocking rather than asphalt. There are pockets of green spaces surrounding the facility, providing shade and comfortable sitting areas for the users of that complex. There is also a provision of an efficient vehicular circulation path from the gate to the main entrance of the facility.

4.2.3 Building description

Due to the peculiarities of this repurposed facility, the building description is in two parts: the exterior and the interior.

4.2.3.1 Exterior

The building is a two-story structure with a pitched roof, constructed from concrete block walls and finished in cream paint. This expresses modernism in fusion with Nigerian-style buildings, thereby promoting integration with its surrounding community. A surrounding perimeter fence with integrated columns serves as a security boundary wall for the facility.

4.2.3.2 Interior

The spa’s interior design combines contemporary themes with vernacular elements. The space offers a calm environment by layering ambient and task lighting; reflective surfaces are used to make certain small spaces feel larger and more spacious. Warm colours, such as beige and neutral tones like white, comprise the colour palette of this facility. Artificial greenery elements are used at the facility’s entrance to provide a sense of biophilia to guests and users.

4.2.4 Spatial organisation and analysis

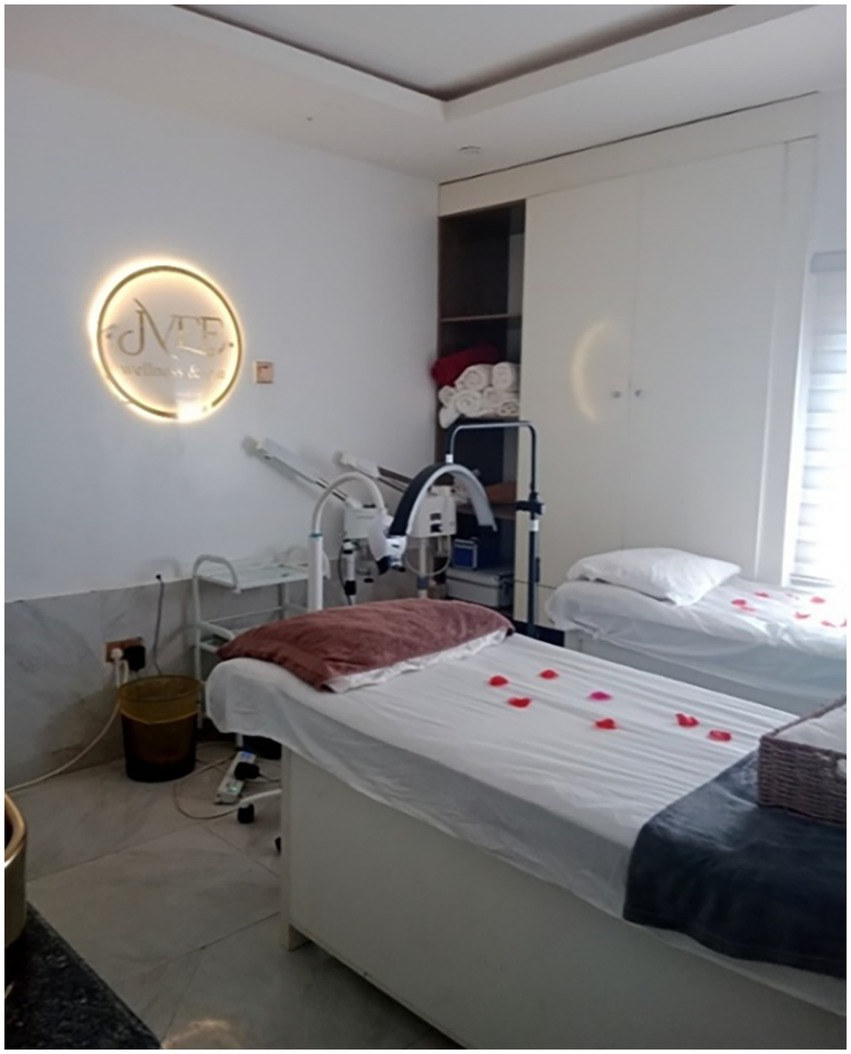

The spatial layout of the facility reflects a careful consideration of the functionality required in a spa and wellness space, as shown in Figure 16. The reception and waiting room functions are located in the same space, with a separate nook reserved solely for pedicures and manicures. The reception/waiting area is characterised by in-built storage spaces designed to display their cosmetic brand products. The waiting room leads to a private consultation room, which restricts access to anyone who is not undergoing a consultation. The waiting room also leads to a lobby that shows three doors: one to the restroom, another to the spa and wellness spaces and the last to the rear part of the facility. The wellness spaces comprise four rooms, each with different equipment and layouts to suit their diverse functions, as shown in Figures 17–20. This simple, functional circulation design, despite being constrained by the facility’s spatial limitations, reflects creative space optimisation and effective zoning of functions.

Figure 16

Floor plan of Jvee Wellness Spa.

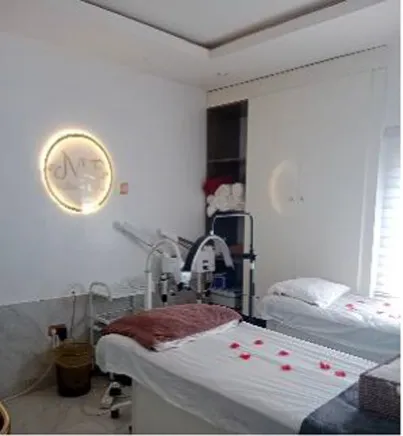

Figure 17

Massage room showing low-flow plumbing fixtures.

Figure 18

Facial room at Jvee Wellness.

Figure 19

Couple’s massage room in Jvee Wellness Spa.

Figure 20

Pedicure room in Jvee Wellness Centre.

4.3 Case study 3: Evenana Spa, Evolve 360, Abuja

Location: Franca Afegbua Cres, Gudu, Abuja 900,110, Federal Capital Territory.

4.3.1 Building overview

Evolve 360 is a modern architectural complex that accommodates a number of wellness spaces within its walls, such as wellness centres, open restaurant areas and a gym. Due to its mixed-use nature, the complex also has some office spaces. Although the complex is not officially labelled as a wellness centre, it houses key wellness spaces and public areas that these spaces utilise. Evenana Spa is one of the main wellness spaces within that complex, and it exemplifies contemporary architectural design. The facility’s exterior façade features a glass curtain wall system and neat geometric lines. The design features a clean aesthetic, suitable for wellness functionality, and incorporates both public and private spaces throughout its multi-level layout, as shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21

Exterior view of Evolve 360.

4.3.2 Site layout

The site layout showcases careful consideration of Abuja’s urban context with strategic setback from the street. Although this setback may be inadequate for ample vehicular circulation, it allows for unhindered and safe pedestrian movement. The building is situated in an urban area, close to various commercial, recreational, and hospitality establishments. This strategic positioning allows nearby tourists and residents to have close access to the wellness services at Evolve 360.

4.3.3 Building description

This facility is a four-story building featuring a central atrium with a skylight, as illustrated in Figure 22. The external features of the building include a modern curtain wall system and white aluminium panels for the façade, a cantilevered canopy entrance finished with the same materials as the building, geometric massing with strong horizontal and vertical lines, and strategic fenestration placement to allow daylighting into the building interior.

Figure 22

Atrium and lounge spec at Evolve 360.

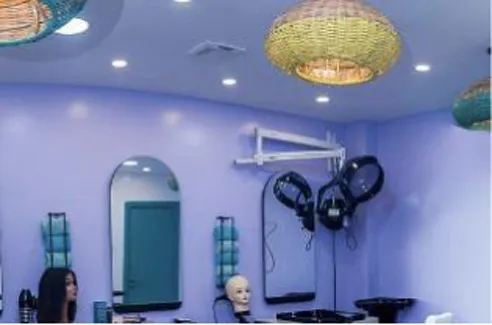

The interior layout of the building is characterised by warm and neutral tones in the public spaces, offering a sense of tranquillity to the users. The atrium is covered with a skylight, providing ample daylight to the building’s interior. This atrium space features a sit-out/restaurant area where users can relax or conduct their daily tasks. Due to the atrium’s height, the space is well-ventilated and airy, offering users comfort and passive design benefits. Evenana Wellness Spa is situated on the top floor of the complex, offering stunning views of the surrounding area to its guests. The plan layout of their facility aids easy circulation due to its functional and balanced design. The wellness centre offers a contrast to the facility’s hues by using a unique blend of turquoise for the walls and door, in harmony with the walnut brown colour of their storage spaces in the interior design, as shown in Figure 23. This colour choice helps to promote a sense of calm and stress reduction while maintaining alertness and focus. This colour scheme also helps to alter space perception by making a space feel larger than it already is. Regarding biophilia, turquoise can also convey a subtle connection to nature, as it resembles the colour of tropical waters and some of its elements. When paired with brown, it effectively conveys a tropical, beach-like, and restful ambience.

Figure 23

Turquoise wall paint in Evenana Wellness Centre.

Evenana interior décor is characterised by certain African art elements and motifs, as shown in Figure 24, adding warmth and texture to the space. This material and design choice helps to improve the traditional and heritage economy of the facility, bringing a sense of familiarity and place to the users of the wellness space.

Figure 24

Interior décor of the massage room showing African elements.

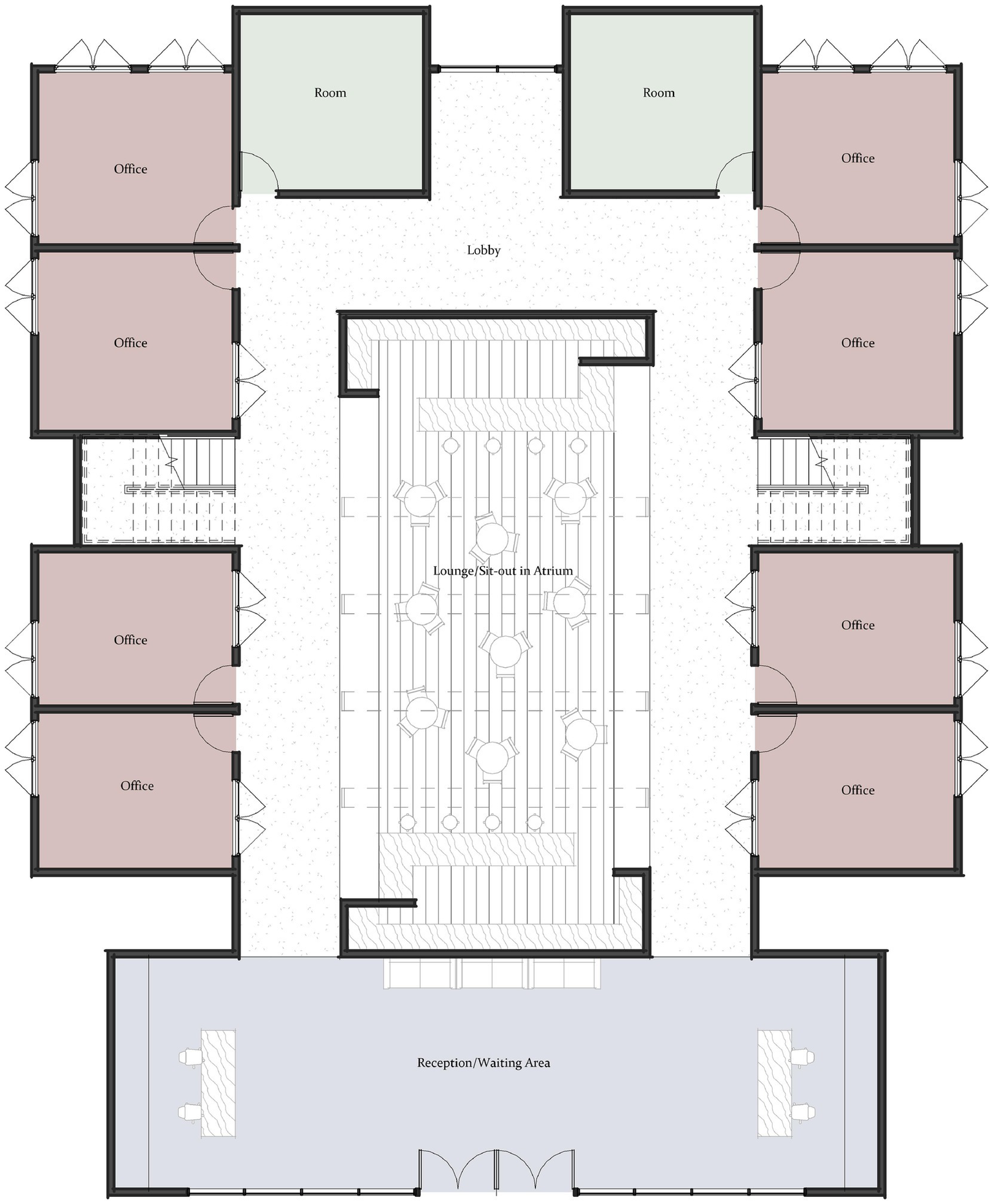

4.3.4 Spatial organisation and analysis

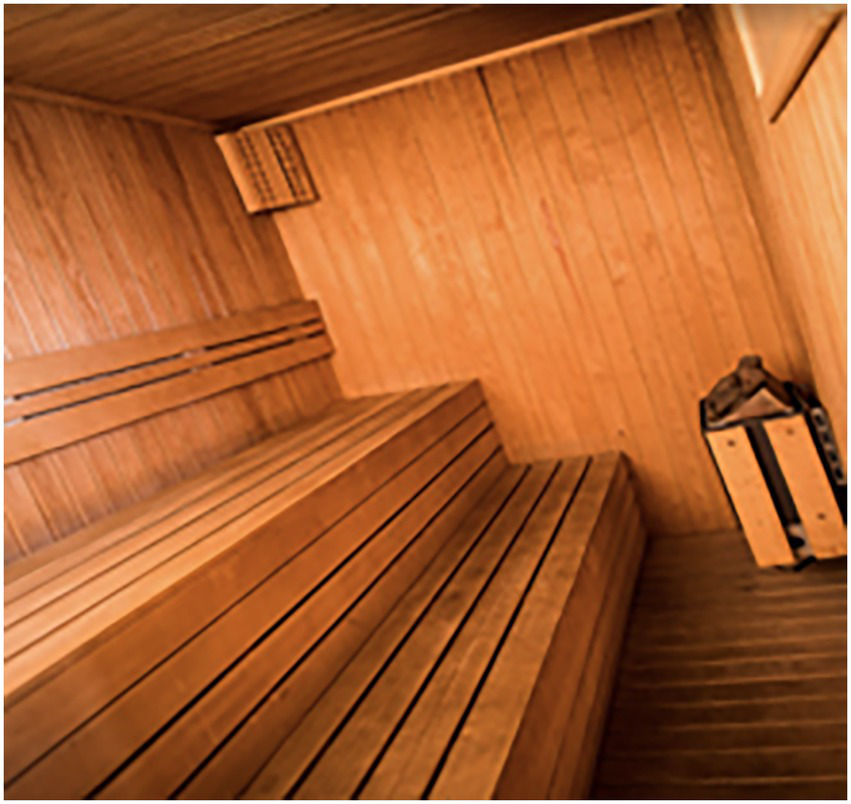

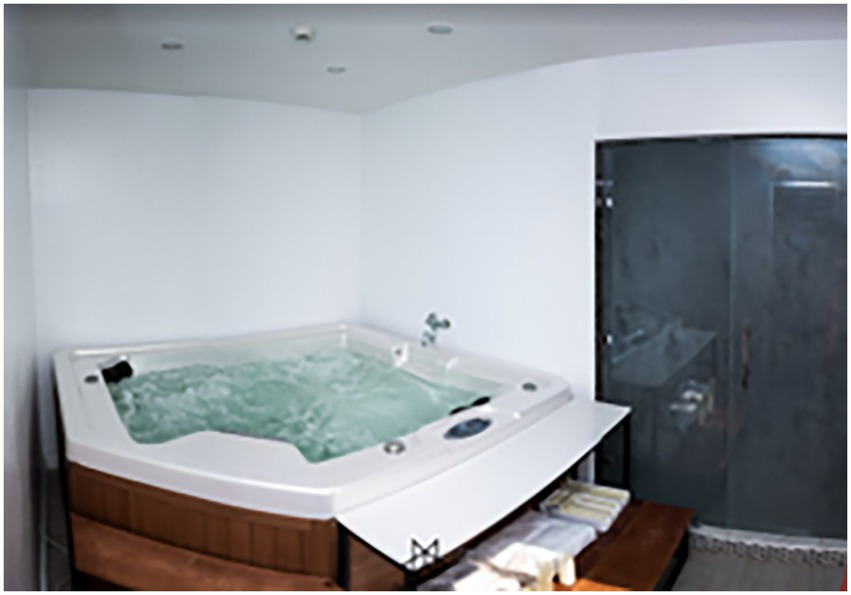

The spatial organisation of this facility will be analysed under three separate categories: the public space, the wellness/treatment spaces and the private rooms. Figures 25 and 26 show the floor plan layout of the Evolve 360 centre and Evenana Wellness Centre, respectively. The public space comprises of the reception/waiting area, the circulation/transition spaces and the retail display areas. The wellness spaces include the hair and beauty salon, massage rooms, facial rooms, Jacuzzi room, and sauna, as shown in Figure 27. The private spaces include offices, a staff room, a consultation room, changing rooms, and restrooms. There is a smooth transition between these spaces to aid functionality and circulation. The wellness spaces are located further into the facility to ensure adequate privacy and seclusion for the guests. One key feature of this facility is the Jacuzzi room, which features a large window that opens up to a beautiful scenery of Abuja’s urban scape and a water body beneath it, offering the guests and users of that space a variety of spatial experiences, as shown in Figures 28–30.

Figure 25

Ground floor plan of Evolve 360.

Figure 26

Third floor plan of Evenana Wellness Centre.

Figure 27

Sauna in Evenana Wellness Spa.

Figure 28

Jacuzzi room at Evenana Wellness Centre.

Figure 29

Large window in jacuzzi room.

Figure 30

View from jacuzzi room.

5 Discussion

In answering the second objective, each facility was analysed using the regenerative principles coined by Tabassum and Park, (2024) to ensure a comprehensive analysis and suitability to recent literature discourse. The identified RAPs in each facility were then discussed to assess the extent of their implementation.

5.1 Assessment of regenerative architecture principles in case studies

Tables 4–6 depict qualitative assessments of the seven RAPs as postulated by Mattar et al. (n.d.): Place, Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Costs. Each principle is assessed based on its implementation extent using a four-point scale from 0 to 3, with 0 for ‘Absent’, 1 for ‘Low’, 2 for ‘Moderate’ and 3 for ‘High’. This evaluation approach offers a comprehensive view of the facility’s performance, encompassing not only environmental considerations but also human well-being and inclusivity. The maximum achievable score using this method is 84.

Table 6

| S/N | Principles | Present | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (0) | Low (Armstrong, 2023) | Moderate (Sholanke and Nwangwu, 2025) | High (Chi et al., 2019) | ||

| A. Place | |||||

| 1 | Use of native or adapted vegetation | * | |||

| 2 | Site selection minimises environmental impact | * | |||

| 3 | The design promotes access to outdoor views and natural surroundings | * | |||

| 4 | Integration with the surrounding community | * | |||

| B. Water | |||||

| 5 | Rainwater harvesting systems | * | |||

| 6 | Greywater recycling systems | * | |||

| 7 | Low-flow or water-efficient plumbing fixtures | * | |||

| 8 | Visible water features enhancing user experience (e.g., fountains, pools) | * | |||

| C. Energy | |||||

| 9 | Use of renewable energy systems | * | |||

| 10 | Smart energy management systems (e.g., motion sensors, automated controls) | * | |||

| 11 | Passive design features for natural lighting and ventilation | * | |||

| 12 | Efficient use of energy-saving lighting systems | * | |||

| D. Health and Happiness | |||||

| 13 | Presence of green spaces (e.g., gardens, courtyards) | * | |||

| 14 | Access to natural lighting in user areas | * | |||

| 15 | Acoustic measures to enhance comfort | * | |||

| 16 | The design encourages physical activity (e.g., walking paths, stairs) | * | |||

| E. Materials | |||||

| 17 | Use of recycled or upcycled building materials | * | |||

| 18 | Locally sourced materials to reduce transportation impacts | * | |||

| 19 | Non-toxic materials for interior finishes | * | |||

| 20 | Durability and adaptability of materials to environmental conditions | * | |||

| F. Equity | |||||

| 21 | Inclusive design features (e.g., ramps, elevators, braille signage) | * | |||

| 22 | The design promotes equitable access to amenities for all users | * | |||

| 23 | Spaces encourage community interaction and social cohesion | * | |||

| 24 | Staff facilities and workspaces are designed for comfort and efficiency | * | |||

| G. Costs | |||||

| 25 | Evidence of cost-efficient energy and water systems | * | |||

| 26 | Long-term operational cost savings from sustainable design features | * | |||

| 27 | Investment in high-quality, durable materials for cost savings over time | * | |||

| 28 | Visible efforts to balance user affordability with luxury and wellness offerings | * | |||

| Total score | 49 | ||||

Identification of regenerative architecture principles in Evenana Wellness.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

Following this evaluation framework, the three case studies exhibits varying levels of RAP adoption. Nisa Wellness Retreat received the highest score of 70 out of 84, reflecting the highest implementation of RAPs across the case studies. In contrast, Evenana Wellness scored 49 out of 84, while Jvee Wellness and Spa received a lower score of 40 out of 84. These results reveal clear variations in the extent and consistency of RAPs adoption among the three facilities.

5.1.1 Adoption levels of identified RAPs in case studies

5.1.1.1 Place

Across the three wellness facilities, the ‘Place’ principle demonstrates relatively strong adoption, although exhibited through varying strategies. Nisa Wellness Retreat incorporates native and adapted vegetation in its landscaping, while its site selection minimises environmental impact on the surrounding ecosystem. Evenana Wellness Centre’s design promotes access to outdoor views and natural surroundings, and it is well-integrated with its surrounding community. The facility’s design also promotes socio-economic integration by providing general spaces that foster social interaction, as well as offering services that the community needs. In contrast, JVEE Wellness and Spa adopts an adaptive reuse approach to this facility, preserving the architectural character of the neighbourhood and promoting integration with the local context in which it is situated.

5.1.1.2 Water

Water emerged as the weakest RAP across all three case studies, signifying a significant gap in regenerative water management within Abuja’s wellness facilities. Nisa Wellness Retreat incorporates an elevated swimming pool, enhancing visual experience; however, it lacks rainwater harvesting and greywater recycling systems. Similarly, Evenana Wellness Centre and JVEE Wellness and Spa utilises low-flow water fixtures and a technological water sound simulation to compensate for the absence of visible water features.

5.1.1.3 Energy

Energy-related strategies reveal moderate but varying degrees of adoption across the facilities. Nisa Wellness Centre harnesses solar power and other renewable energy systems to reduce its environmental impact. The building employs passive design strategies that maximise natural daylight penetration, complemented by energy-efficient LED lighting systems throughout the facility. Jvee Wellness Centre utilises energy-efficient lighting systems and reflective surfaces to maximise light distribution within the facility. Although Evenana Wellness Centre does not rely on renewable energy sources for its operation, its design and choice of energy-efficient electrical fixtures, along with passive daylighting through a central atrium, aim to compensate for this.

5.1.1.4 Health and happiness

All facilities demonstrate relatively strong implementation of the Health and Happiness principle, reflecting their wellness-focused operations. Nisa Wellness Retreat features green spaces, circulation paths, and outdoor terraces throughout the building, offering therapeutic and physical benefits to its users. JVEE Wellness and Spa fosters this multi-dimensional well-being by adopting colour schemes, material textures, and lighting designs that create a calming and therapeutic environment for the users. Similarly, Evenana Wellness centre makes use of tropical, vibrant colours to evoke a sense of visual interest, clarity, and connection to nature while being calm and gentle. This colour choice helps to heighten user experience and user well-being.

5.1.1.5 Materials

The materials used for the exterior design and interior finishes of Nisa Wellness Retreat are locally sourced, thereby reducing the environmental impact of transportation. JVEE Wellness and Spa benefits from adaptive reuse of the building, significantly reducing material cost and the socio-economic and environmental impact of transportation. The interior design of the spa rooms also utilises local materials for finishing, showcasing African culture through the creative use of these materials. Evenana Wellness Centre also integrates local, sustainable African-themed materials such as wood and woven raffia offering a sophisticated space where these elements, coupled with contemporary elements, can work together to add warmth and texture to the space.

5.1.1.6 Equity

The principle of Equity is addressed differently across the case studies. Nisa Wellness Retreat and Evenana Wellness Centre exhibit stronger equity-based performance by being accessible to all individuals, regardless of physical impairment, through the provision of an entrance ramp and elevators. JVEE Wellness and Spa, however, exhibits a weaker equity provision due to spatial constraints that limit inclusive access and communal engagement. However, none of the facilities were designed to cater for those with visual and hearing impairments.

5.1.1.7 Costs

The cost considerations of the three facilities demonstrate a respectable preference for long-term operational effectiveness over immediate cost savings. With its emphasis on passive design strategies, Nisa Wellness Retreat, which received the highest overall score, exhibits the most intentional balance between wellness services and operational ease. Adaptive reuse, material selection, and low-flow fixtures help Evenana Wellness Centre and JVEE Wellness and Spa achieve a respectable degree of cost efficiency. However, given the limited implementation of advanced regenerative principles, there is still ample room for improvement.

5.2 Synthesis of findings and practical implications

This section synthesises the results presented in the previous section by explicitly linking cross-case patterns of regenerative adoption to the study’s research objectives. In particular, this section interprets RAPs strengths and weaknesses in relation to (i) the physical architectural features of these selected and (ii) identifying the regenerative architecture principles adopted in these facilities.

From the data gathered from the three national case studies, similar themes relevant to the field of wellness design were discovered. These themes were then analysed comparatively among the three facilities to draw valuable insights unique to each facility, further enhancing the design process of the proposed wellness facility. These findings will then be applied in the development of an innovative wellness facility tailored to Nigeria’s socio-economic climate and context. The results of this comparative analysis are tabularised below:

Additionally, mean scores were calculated for each regenerative domain across facilities, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7

| Domain | Mean score (0–3) | Adoption interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Place | 2.6 | High |

| Water | 1.1 | Low |

| Energy | 1.4 | Moderate |

| Health & Happiness | 2.2 | Moderate–High |

| Materials | 2.0 | Moderate |

| Equity | 1.8 | Moderate |

| Cost | 1.9 | Moderate |

Mean domain scores across facilities.

Table 8 provides a pictorial cross-analysis of the wellness facilities under various shared themes. It reveals how each facility addressed each principle, offering key insights into innovative ways that user well-being and user comfort can be achieved in facilities of varying sizes, limitations and wellness focus. Each comparison is also supported by photographic images to demonstrate its adoption.

Table 8

| S/N | Principle | Wellness facilities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nisa Wellness Retreat | Jvee Wellness Centre | Evenana Wellness Spa at Evolve 360 | ||

| 1 | Exterior Façade/Welcoming Facade |

|

|

|

| Building design looks welcoming due to its simple design and similarity to typical Nigerian residential buildings | Similar exterior façade to Nisa Wellness Retreat | Adopted a more modern, commercial look with aluminium panels and glass facades | ||

| 2 | Materials used in wellness spaces |

|

|

|

| Blend of modern and afro-centric material for the design of wellness spaces, such as wood, metal, and raffia. | Adopted a more modern approach to interior design | Similar material scheme to Nisa Wellness, creatively combining both afro-centric and modern themes | ||

| 3 | Color Scheme |

|

|

|

| Warm and calm tones in the interior, such as white, orange, and brown. | Warm, neutral and calm tones as well such as white and beige | Chose a different approach to tranquillity by using cool, tropical colours scheme such as turquoise, brown and white. | ||

| 4 | Natural Lighting |

|

|

|

| Ample natural lighting in the hotel | This facility, unlike Nisa wellness, has fewer naturally lit spaces; however, this design choice effectively shields users from thermal discomfort and glare, particularly during peak heat periods. | Although Evenana Wellness offers fewer naturally lit wellness spaces compared to Nisa, its public spaces are amply lit due to the presence of the skylight roof. | ||

| 5 | Natural Ventilation |

|

|

|

| Incorporates passive design strategies by providing large windows and open green spaces | Also limits the entrance of natural ventilation, but makes up for it with HVAC cooling systems, maintaining the Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) of the space | Incorporates passive design strategies in certain spaces, such as the Jacuzzi room | ||

| 6 | Ambient Lighting design in wellness spaces |

|

|

|

| Makes use of blue lights in wellness spaces to evoke a sense of calm and serenity | Adopts a clear, calm lighting scheme as well for the users | Similar lighting scheme to Jvee wellness, however, this lighting creates a deep blue hue when paired with the turquoise colour of the walls | ||

| 7 | Notable design feature |

|

|

|

| Outdoor green areas and a stunning view | Serene, secluded, and an aesthetically designed interior space | Jacuzzi room with a beautiful view of a water body and natural vegetation | ||

| 8 | Rating (%) | 82.1 | 47.6 | 58.3 |

Comparative analysis of national case studies.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

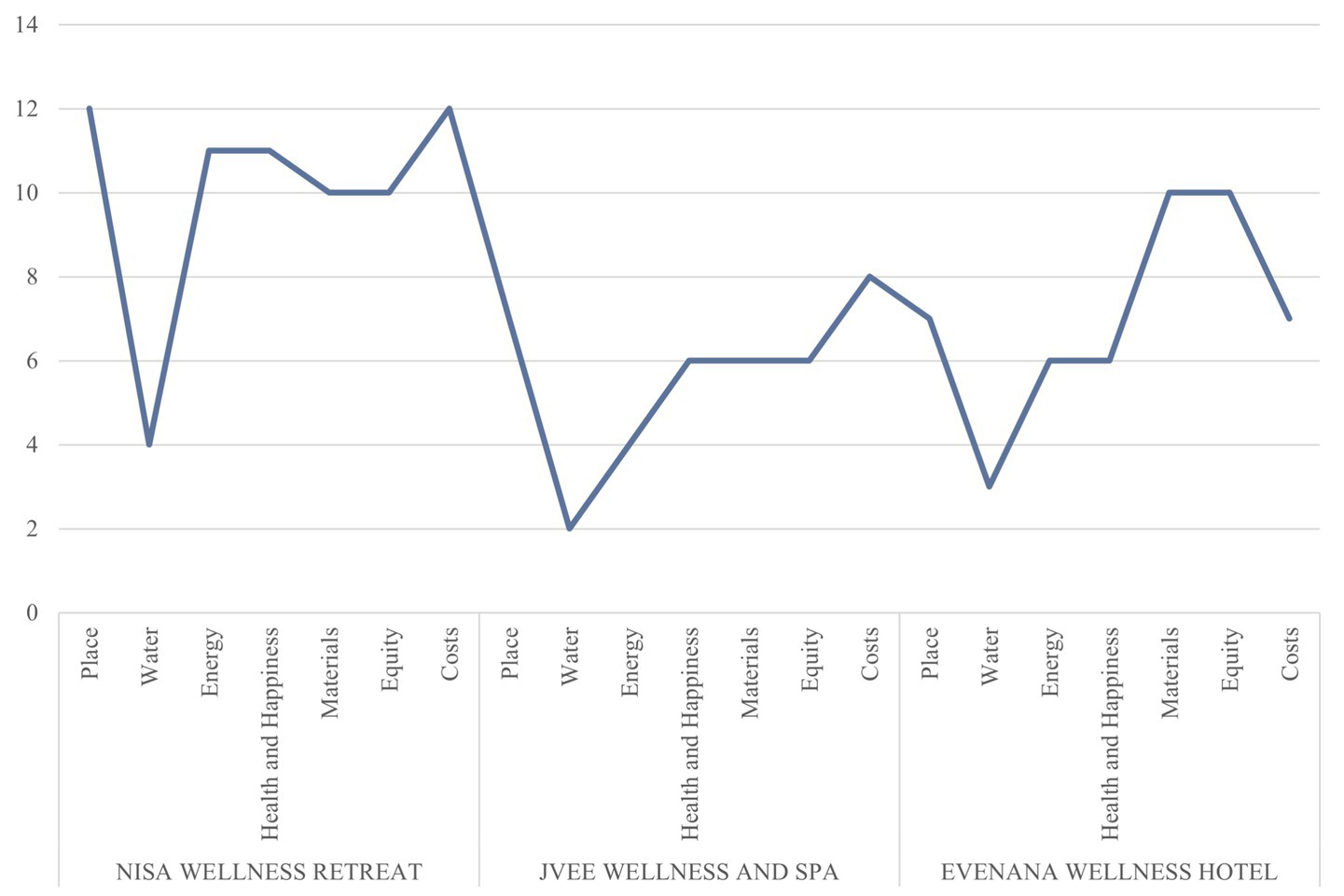

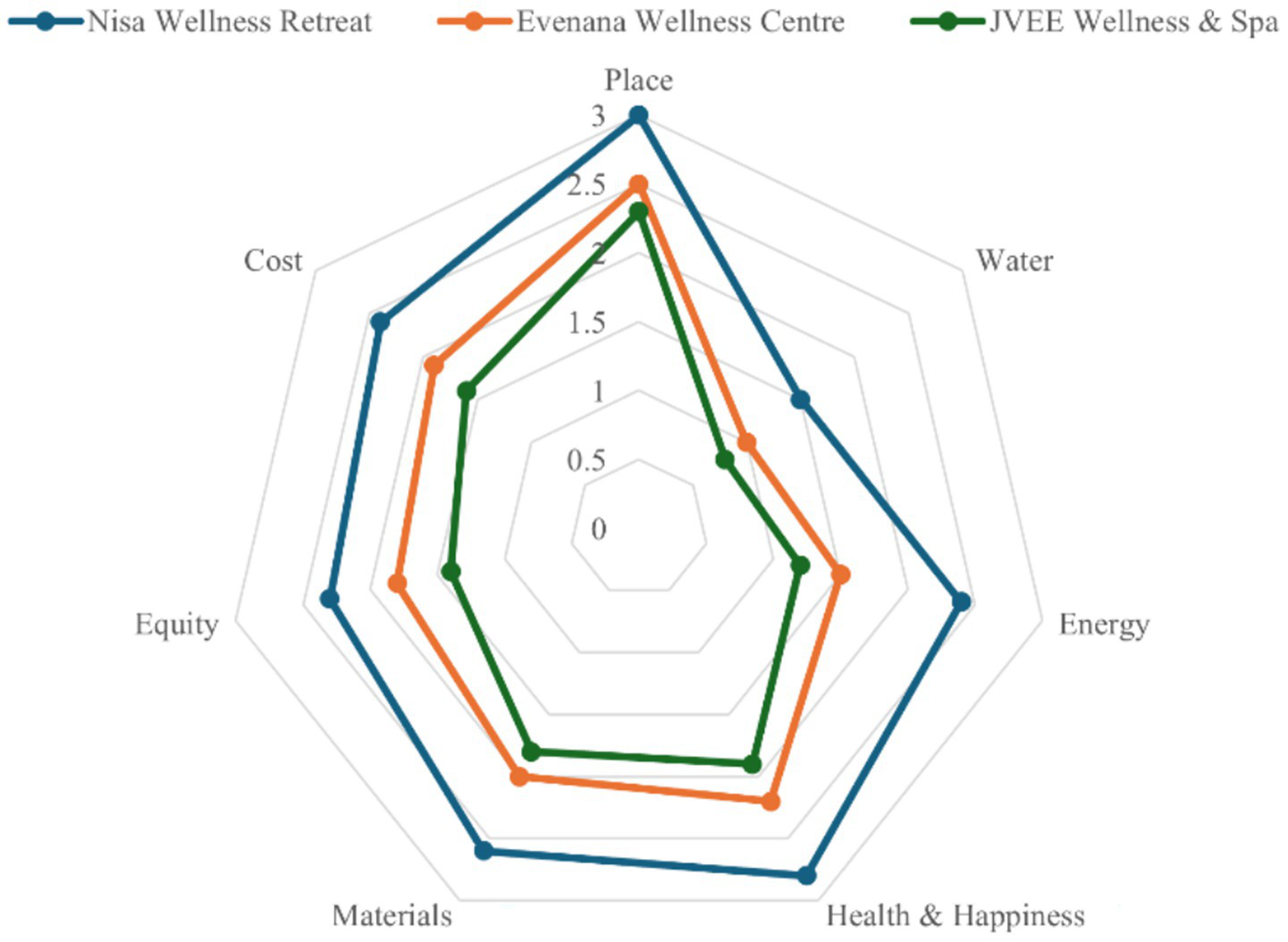

Figure 31 illustrates the performance of each RAP across the selected wellness facilities, allowing for a cross-case comparison of how individual regenerative principles are implemented. Figure 32 presents the aggregated regenerative adoption scores for the three assessed wellness facilities, based on a maximum possible score of 84.

Figure 31

Chart showing cross-analysis of selected facilities. Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

Figure 32

Total regenerative adoption scores by facility. Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

Overall, the cross-analysis reveals that RAPs are not uniformly applied across wellness facilities. Design attention is often focused on experiential and material qualities, while aspects related to infrastructure and water systems receive less attention. This disparity highlights the need to integrate both technical and operational approaches to regeneration, alongside spatial and experiential design considerations. A radar chart illustrating domain-level regenerative adoption profiles across facilities has also been added (Figure 33), allowing for a direct visual comparison of strengths and weaknesses across cases. Scores are based on a 0–3 scale, where 0 indicates absence, and 3 indicates strong adoption.

Figure 33

Domain-level regenerative adoption profiles across facilities. Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

Lower performance in the Water, Energy, and Equity domains has implications that extend beyond overall adoption scores, as these areas shape key performance pathways within wellness-oriented environments. Limited attention to water-related strategies affects resource efficiency and influences how environmental responsibility is perceived, while weaker adoption of energy-domain strategies can reduce daylight quality, thermal comfort, and long-term operational efficiency. Gaps within the Equity domain—particularly those related to accessibility and inclusive design—may further limit usability and narrow the range of users who can fully engage with wellness spaces. Together, these principles closely align with core indoor environmental quality (IEQ) factors, including visual comfort, acoustic conditions, thermal regulation, and universal access, all of which are essential to the effective operation of wellness facilities.

Table 9 summarises the overall performance of adopting RAPs across the three analysed case studies: Nisa Wellness Retreat, JVEE Wellness and Spa, and Evenana Wellness Hotel.

Table 9

| Location | Principle | Score (/84) |

|---|---|---|

| Nisa wellness retreat | Place | 12 |

| Water | 4 | |

| Energy | 11 | |

| Health and Happiness | 11 | |

| Materials | 10 | |

| Equity | 10 | |

| Costs | 12 | |

| Total | 70 | |

| Jvee wellness and spa | Place | 7 |

| Water | 2 | |

| Energy | 4 | |

| Health and Happiness | 6 | |

| Materials | 6 | |

| Equity | 6 | |

| Costs | 8 | |

| Total | 39 | |

| Evenana wellness hotel | Place | 7 |

| Water | 3 | |

| Energy | 6 | |

| Health and Happiness | 6 | |

| Materials | 10 | |

| Equity | 10 | |

| Costs | 7 | |

| Total | 49 | |

Comparative analysis of national case studies showing rating score.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

Figure 31 shows a cross-analysis of the facilities, revealing patterns of varying RAP implementation amongst the three institutions. This comparative assessment is based on the seven key RAPs derived from relevant studies: Place, Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Costs. Computing the diverse rating scores per RAP, the highest score achievable by any facility, using the developed checklist, is 84.

Nisa Wellness Retreat had the highest score, as shown in Table 4, because it possesses the majority of the facets of Regenerative architecture listed on the checklist. The majority of the RAPs identified were highly implemented, with Rainwater harvesting and Greywater recycling being the only absent principles in the facility. This pattern was observed throughout all three facilities, as all facilities had their lowest scores in the element of ‘Water’, especially JVEE Wellness and Spa (2/12). This highlights a lack of priority placed on water management practices in wellness spaces within the study area. This aligns with a recent study carried out by Martins et al. (2025) that reveals a significant gap in Nigeria’s water management strategies, stemming from non-compliance with relevant policies, inadequate infrastructure, and the prioritisation of sustainable water management practices. In the principle of ‘Energy’, Nisa Wellness Retreat scored the highest score (11/12), followed by Evenana (6/12), then JVEE scoring the least (4/12). This gap highlights a reliance on conventional energy systems rather than sustainable and renewable energy sources. A relevant study conducted in 2023 by Akande et al. (2023) revealed a severe lack of energy supply in Nigeria to meet the demands of the growing population. Most Nigerians exhibit apathy towards energy efficiency practices due to a lack of interest or inadequate knowledge of the necessary changes. The study emphasises the need for experts to prioritise energy-efficiency practices in Nigeria.

Nisa Wellness Retreat had the highest score in the ‘Health and Happiness’ category, while the other facilities showed moderate implementation. The disparity may be associated with indoor environmental quality, exposure to natural light, user-focused facilities, and spatial quality. In the principle of ‘materials’, all facilities exhibit a moderate to high degree of implementation. This reflects a decent adoption of locally sourced building materials; however, a more comprehensive lifecycle analysis may be necessary. Both NISA and Evenana received a score of 10/12 in the principle of ‘Equity’, indicating that they prioritised inclusive design and accessibility. The lower score JVEE received indicates that they lack sufficient provisions in this regard. Similarly, Nisa also scored the highest score in ‘Costs’, suggesting cost-effective regenerative strategies within the facility.

Comparatively, all three facilities had decent scores in certain RAPs such as ‘Place’, ‘Materials’, ‘Equity’, and ‘Costs’. The facility with the lowest score was Jvee Wellness and Spa, scoring 39, which is less than 50% of the total score. It was followed by Evenana Wellness, scoring 49, and Nisa Wellness Retreat, scoring 70, which is over 80% of the total score. This analysis revealed that Nisa Wellness Retreat has a significantly higher score than the other facilities, demonstrating that the implementation of RAPs in Abuja is feasible and impactful. The indicators highlighted in Table 10 represent the most critical opportunities for improving regenerative performance in each facility, prioritised based on potential wellness impact and implementation feasibility.

Table 10

| Facility | Indicator | Impact on wellness | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nisa | Greywater reuse | High | Medium |

| Nisa | Renewable energy integration | Medium | Medium |

| Nisa | Universal access to outdoor areas | Medium | High |

| Evenana | Rainwater harvesting | High | Medium |

| Evenana | Natural ventilation strategies | High | Low |

| Evenana | Acoustic comfort measures | Medium | High |

| JVEE | Low-flow water fixtures | High | High |

| JVEE | Daylighting optimisation | Medium | Medium |

| JVEE | Universal accessibility | High | Medium |

Priority missing or weak indicators by facility.

Source: Author’s fieldwork (2024).

The significant disparity between Nisa and the other facilities suggests a need for increased awareness and policy initiatives to promote the adoption of RAPs in Nigerian hospitality facilities. Hindrances to its effective implementation should be addressed with professional training and educational initiatives. A study done by Oluwasegun et al. (2025) on the green building techniques applicable in Nigeria supports this notion. This study reveals that the implementation of green and sustainable building practices in Abuja presents a substantial opportunity for environmental and socio-economic benefits. However, a similar study (Ashen et al., 2024) demonstrates that the major hindrance to the effective implementation of such green-focused construction in the study area is the initial cost associated with such practices. Other issues include a lack of awareness and an indifference to the culture of sustainability.

6 Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed to assess the adoption levels of RAPs in three wellness facilities in Abuja: Abuja-Nisa Wellness Retreat, JVEE Wellness and Spa, and Evenana Wellness Hotel, using a ‘seven-petal’ framework of regenerative architecture principles. The research objectives were achieved through a systematic evaluation of the three case studies, revealing disparate adoption levels of RAPs across the three selected wellness facilities. Although certain principles, such as Place, Materials, and Health and Happiness, were strongly implemented, inadequate access to water management strategies, energy-efficient systems, and inclusive design features were also observed.

The main contribution of this study is the development and implementation of an assessment framework that translates RAPs into observable indicators for wellness facilities. The study has also provided a regenerative adoption profile within the context of Abuja, serving as a guide for future comparative and longitudinal studies.

From the study findings, the researchers suggest several near-term vs. mid-term actionable recommendations:

6.1 Near-term suggestions

Wellness facilities adopt water management strategies in their daily operations, as well as other RAPs defined by the Living Building Challenge, such as natural lighting and ventilation.

Priority should also be placed on implementing active water-efficiency measures such as low-flow fixtures and regular plumbing maintenance.

6.2 Mid-term suggestions

Facilities with low equity scores should also address their design to ensure unhindered accessibility to every space in the building.

Architects and other relevant stakeholders in the built environment should be duly trained in RAPs through workshops, certifications and inter-professional collaborations with sustainability experts and regenerative design specialists. Government and legislative bodies should also develop frameworks that encourage the adoption of RAPs in building design and construction through policy incentives, public-private partnerships, regulatory frameworks, and the integration of regenerative criteria into building codes.

6.3 Limitations

While this research provides valuable insights into the integration of RAPs in wellness spaces in Abuja, several limitations should be acknowledged. This study evaluated only three wellness facilities due to accessibility restrictions and time constraints. As a result, the findings may not accurately represent the broader spectrum of wellness facilities in Nigeria and other locations with different climatic and cultural contexts. In addition, the findings of this study are specific to the Nigerian context, particularly in Abuja, where infrastructural policies may differ from those in other states, further limiting the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the scope of this research does not include subjective data from users’ perceptions of these RAPs and their resulting psychological and physiological health outcomes. Data collection relied solely on an observation guide, which does not fully capture the experiences of the users of these facilities. This approach could lead to an inadequate representation of the true level of adoption of RAPs. Therefore, a mixed-methods approach with a larger sample size could be more effective in providing comprehensive insight into the research topic. Consequently, it is also recommended that similar studies be extended to different regions of Nigeria and the world to gain a more comprehensive view of the study’s focus.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ENE: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. BGO: Writing – original draft, Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Covenant University for providing the necessary resources and support to undertake this research. We extend our appreciation to the Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation, and Development (CUCRID) for their invaluable guidance, encouragement, and access to research facilities throughout the course of this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adewale AB Ogunbayo BF Aigbavboa CO Ene VO . (2025). “Implementing Litman’s nine principles of regenerative architecture: an evaluation of a proposed public building design in Lagos.” in The fourteenth international conference on construction in the 21st century (CITC-14); 2024 Sep 2–5; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389001538_Implementing_Litman's_Nine_Principles_of_Regenerative_Architecture_An_Evaluation_of_a_Proposed_Public_Building_Design_in_Lagos_Nigeria (Accessed August 3, 2025).

2

Aduwo E. B. Sholanke A. B. Eleagu J. C. (2024). Prospects, challenges and solutions for achieving sustainability in implementing green architecture strategies in high-rise buildings: a review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci.1428:012004. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1428/1/012004

3

Akande O. Emechebe C. Lembi J. Nwokorie J. (2023). Energy demand reduction for Nigeria housing stock through innovative materials, methods and technologies. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol.8, 216–232. doi: 10.47481/jscmt.1184338

4

Armstrong R. (2023). Introducing regenerative architecture. J. Chin. Archit. Urban.1882. doi: 10.36922/jcau.1882

5

Ashen R. M. Rimtip M. N. Davou M. Y. (2024). A framework for implementing green building practices in Abuja, Nigeria. East Afr. Scholars J. Eng. Comp. Sci.7, 104–115. doi: 10.36349/easjecs.2024.v07i08.004

6

Chi C. G. Chi O. H. Ouyang Z. (2019). Wellness hotel: conceptualisation, scale development, and validation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag.89:102404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102404

7

Dimitrovski D. Marinković V. Djordjević A. Sthapit E. (2024). Wellness spa hotel experience: evidence from spa hotel guests in Serbia. Tour. Rev. doi: 10.1108/TR-11-2023-0770

8

Fahmy A. Abdou A. Ghoneem M. (2019). Regenerative architecture as a paradigm for enhancing the urban environment. Port-Said Eng. Res. J.23, 11–19. doi: 10.21608/pserj.2019.49554

9

Global Wellness Institute . (2024). Statistics & facts - global wellness institute. Available online at: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/press-room/statistics-and-facts/ (Accessed August 3, 2025)

10

Hassan A. S. A. (2016). Introduction to the living building challenge. Q. Sci. Proc.2016:2. doi: 10.5339/qproc.2016.qgbc.2

11

Lucchi E. (2023). Regenerative design of archaeological sites: a pedagogical approach to boost environmental sustainability and social engagement. Sustainability15:3783. doi: 10.3390/su15043783

12

Martins G. Ehinmentan B. Mafimisebi P. America A. Gbadero G. (2025). Sustainable water resource management in Nigeria: challenges, integrated water resource management implementation, and national development. Int. J. Trendy Res. Eng. Technol.9, 8–16. doi: 10.54473/ijtret.2024.9102

13

Mattar Y Alali M Beheiry S . (n.d.). Comparative review of the living building challenge certification. In: The thirteenth international conference on construction in the 21st century (CITC-13); 2023; Arnhem, the Netherlands. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373604343_Comparative_Review_of_the_Living_Building_Challenge_Certification (Accessed August 3, 2025).

14

Oluwasegun V. A. Kpalo S. Y. Magaji J. I. (2025). Classification of green building techniques applicable to the federal capital city, Abuja, Nigeria. Int. J Afr. Innov. Multidiscip. Res.7:29. doi: 10.70382/mejaimr.v7i2.029

15

Petrovski A. Pauwels E. González A. G. (2021). Implementing regenerative design principles: a refurbishment case study of the first regenerative building in Spain. Sustainability13:2411. doi: 10.3390/su13042411

16

Pilzer P. Z. (2007). The new wellness revolution: How to make a fortune in the next trillion-dollar industry. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons.

17

Sholanke A. B. Nwangwu C. I. (2025). Influence of architectural education on sustainable design thinking: a review of energy-efficiency concepts. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci.1492:012015. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1492/1/012015

18

Sood S. Gupta A. (2024). Exploring the impact of family environment on quality of life, wellness, and self-concept: a comprehensive analysis. Afr. J. Biomed. Res.27, 49–62. doi: 10.53555/ajbr.v27i3s.1719

19

Stamenković M Stojčić L Glišović S . (2018). “Regenerative design as an approach for building practice improvement.” in Proceedings of 26th international conference ecological truth and environmental research–EcoTER’18. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335568554_REGENERATIVE_DESIGN_AS_AN_APPROACH_FOR_BUILDING_PRACTICE_IMPROVEMENT (Accessed August 3, 2025).

20

Tabassum R. R. Park J. (2024). Development of a building evaluation framework for biophilic design in architecture. Buildings14:3254. doi: 10.3390/buildings14103254

21

Zhao J. He M. (2024). Understanding the motivation behind new mothers’ choice of postpartum wellness hotels: scale development and validation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag.121:103795. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2024.103795

Summary

Keywords

case study, regenerative architecture, sustainability, user well-being, wellness facilities

Citation

Ekhaese EN and Olukayode BG (2026) Adoption of regenerative architecture in wellness facilities in Abuja, Nigeria: multiple-case observational evidence. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1691829. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1691829

Received

24 August 2025

Revised

27 December 2025

Accepted

30 December 2025

Published

20 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Pau Chung Leng, University of Technology Malaysia, Malaysia

Reviewed by

Wael Rashdan, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Chris Heng, University of Science Malaysia (USM), Malaysia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ekhaese and Olukayode.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bisola Grace Olukayode, bisola.olukayodepgs@stu.cu.edu.ng

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.