Abstract

Urban areas play a central role in achieving climate neutrality, yet their capacity to drive systemic change remains uneven. The EU Mission on 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030 seeks to accelerate urban transitions through Climate City Contracts (CCCs), but it remains unclear whether cities possess—or can develop—the governance capacities required. Using the Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework, this paper examines the Spanish experience as an early frontrunner in Mission implementation. Drawing on qualitative evidence from seven cities, the study shows that the Mission has stimulated new forms of leadership, coordination, and experimentation, but these procedural advances often remain fragile and weakly institutionalized. Capacities related to reflexivity, learning, and civic engagement progressed more slowly, constrained by administrative inertia, resource limitations, and the procedural urgency embedded in mission delivery. At the same time, intermediaries such as CitiES2030, universities, and civil servants acted as relational infrastructures that enabled coordination and learning under pressure, while urgency and the inevitable reliance on consultants frequently reduced ownership and opportunities for institutional consolidation. These dynamics reveal a core tension in mission-oriented governance: the same architectures that enable rapid mobilization can also reinforce externalization and short-termism, limiting long-term capability-building. The paper argues that embedding capacity-building as a sustained component of mission design—prioritizing process quality, reflexivity, and continuity—will be essential for translating short-term mobilization into enduring transformation within urban sustainability transitions.

1 Introduction and background

Urban areas are central to global climate action, serving as key sites for innovation and systemic transformation. Yet, despite growing awareness of their potential, urban transition initiatives often fall short of delivering significant, measurable action (Westman and Castán Broto, 2022). In response to this challenge, the European Commission launched the “Mission on 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030” in September 2021 under Horizon Europe, supporting 112 municipalities to achieve climate neutrality and act as innovation pioneers (European Commission, 2022). The Mission reflects a shift toward mission-driven governance within the Mission Oriented Innovation Policy (MOIP) framework, designed to tackle “wicked” societal challenges (Mazzucato, 2017; Wanzenböck et al., 2020). By combining an ambitious bold deadline with cross-sector collaboration, it seeks to foster deep, systemic change—technological, institutional, and behavioral—marking a new public governance strategy emphasizing urgency, stakeholder involvement, and co-creation (Alkemade et al., 2011; Geels, 2004; Mazzucato, 2018; Rosa et al., 2021).

At the core of the Cities Mission are the Climate City Contracts (CCCs), a document co-signed by city leaders and witnessed by the European Commission (European Commission, 2022; Shabb et al., 2023; Shabb and McCormick, 2023). While not legally enforceable, CCCs comprise three interlinked elements: a 2030 Climate Neutrality Commitment, an integrated Action Plan, and an Investment Plan detailing financing pathways (NetZeroCities, 2022). This structure aligns ambition with concrete policies, multi-level coordination, stakeholder engagement, and resource allocation, fostering iterative learning and institutionalizing a shared mission to expand urban actors' capacity to act (Kern, 2023; Rogge and Reichardt, 2016; Shabb et al., 2022).

However, despite their promise, scholars describe significant challenges in implementing the Mission and developing the CCC. Conceptual ambiguities around the scope of “climate neutrality” and offsetting practices threaten accountability and comparability (Geels, 2011; Shabb et al., 2022). Many cities lack the real-time emissions data systems needed for adaptive policymaking (Shabb et al., 2022). Financing gaps persist as initial CCCs often under-specify how to mobilize the vast public and private investments required (Shabb and McCormick, 2023; Ulpiani and Vetters, 2023). Their non-binding nature raises concerns about political continuity across electoral cycles (Beretta and Bracchi, 2023; Terwilliger and Christie, 2025). Inclusiveness is also uneven: while financial actors and academia are often engaged, citizens and vulnerable groups are involved in fewer than half of CCC processes (Shtjefni et al., 2024; Ulpiani et al., 2025).

Scaling insights from 100 cities requires deliberate diffusion strategies—peer learning, toolkits, and new mission waves—to prevent a two-speed Europe (Brown, 2021; Fastenrath et al., 2023), with co-learning platforms seen as vital for sharing both technical and governance innovations (Kilkiş et al., 2024; Ulpiani and Vetters, 2023). For this, dynamic interplay of bottom-up experimentation and top-down goal-setting/monitoring, pointing to design principles for institutional architectures that balance flexibility with accountability (Uyarra et al., 2025). Yet, the 2030 deadline imposes urgency that may lock cities into suboptimal pathways unless CCC governance includes institutional slack (Ulpiani and Vetters, 2023).

This paper examines the Spanish Cities Mission—Madrid, Valencia, Valladolid, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Zaragoza Sevilla and Barcelona—as an illustrative case of how transformation-oriented initiatives—aimed at reshaping governance, institutional learning, innovation ecosystems, and urban futures—are unfolding in practice. The Mission calls on cities to break down institutional silos, steer private investment toward decarbonization, and balance adaptation and mitigation while ensuring just transitions (Brown, 2021; NetZeroCities, 2022). Meeting these demands requires new capacities that enable path-deviant change and are embedded in governance structures. In this sense, it is important to raise the critical question of whether cities possess these capacities or whether the Mission contributes to their development, and under which conditions the Mission enables/restricts them. In this tension between assumed and actual capability, a capacity-centered analysis becomes essential, shifting the focus from normative assumptions to a concrete interrogation of transformative potential.

To this end, the paper applies the Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework, which offers a structured lens to assess cities' collective ability to envision, prepare for, and drive deep socio-technical change through ten capacities—from inclusive co-creation and reflexive learning to resource mobilization and strategic leadership (Wolfram, 2016; Wolfram et al., 2019). Unlike alternative models—such as resilience-oriented adaptive capacity, which privileges system persistence under disturbance (Folke et al., 2010; IPCC, 2021), dynamic capabilities theory rooted in corporate strategy (O'Reilly and Tushman, 2008; Teece, 2007), or indicator-based urban resilience indices centered on outcomes (Meerow et al., 2016; Molenaar et al., 2021)—the UTC framework is governance-centered, normatively aligned with transitions, empirically grounded in urban contexts, and operationally tailored to this analysis.

By examining all ten UTC components, this study goes beyond identifying capacity gaps: it highlights how the Mission, by assuming capacities like inclusive governance, reflexive learning, and resource mobilization, may risk setting cities up for unmet goals or shallow compliance. Focusing on transformative capacities allows us to uncover governance barriers that technical metrics may miss, trace how Mission governance dynamics shape or limit municipal skills, and suggest how future CCC iterations could better embed capacity-building. This new approach on capacities seeks to contribute to a more qualitative approach, that combined with quantitative metrics, helps bridge abstract transition theory and actionable governance, offering insights for translating ambitious sustainability missions into context-sensitive pathways for urban transformation.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Urban sustainability transitions governance

Urban sustainability transitions demand governance arrangements capable of steering complex, place-based socio-technical transformations (Coenen et al., 2012; Hansen and Coenen, 2015). Rather than relying on isolated policy instruments, transition governance emphasizes orchestrated processes of collective visioning, iterative experimentation, reflexive learning, and adaptive regulation (Frantzeskaki, 2022; Loorbach, 2010), but they suffer from acute time-pressures, that can forbid deeper deliberation and lock decision-makers into “next-best” choices unless governance designs build in institutional slack—through pre-negotiated contracts or standby funds (Reale, 2021). Central mechanisms include multi-actor platforms—urban living labs, transition arenas, and public–private–civil-society partnerships—that facilitate multi-level coordination and resource pooling while engaging diverse stakeholders in co-creating long-term sustainability pathways (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2013; Bulkeley and Castán Broto, 2013; Nevens et al., 2013), fostered by intermediary actors to broker trust, translate between stakeholders, and sustain long-term coalitions (Hamann and April, 2013; Kivimaa, 2014; Soberón et al., 2023).

Inclusive participation not only enhances legitimacy but also leverages the social learning necessary to negotiate deep uncertainties and embed context-sensitive innovations (Avelino et al., 2019; Frantzeskaki and Rok, 2018; McCrory et al., 2020). Critically, attention to local cultural and geographical specificities ensures that governance interventions resonate with place-based needs and values (Broto and Westman, 2019; Uyarra et al., 2025). Complementing these governance innovations, mission-oriented innovation policy (MOIP) frameworks mobilize resources and align public mandates around bold, time-bound objectives (Mazzucato, 2017).

Despite the promise of these governance models, empirical evidence highlights persistent obstacles. Institutional silos—fragmented departments, siloed budgets, and sector-specific mandates—impede collaboration and knowledge exchange, reinforcing path-dependent routines (Wittmayer and Loorbach, 2016). Such siloing also undermines the systematic capture and diffusion of pilot-project insights into city-wide learning loops, as cities report skills shortages and high staff turnover that erode institutional memory (Dóci et al., 2022; Soberón et al., 2023). Rigid infrastructures and administrative processes further lock in the status quo, while power asymmetries allow dominant actors to capture transition agendas and favor incremental over systemic change (Huovila et al., 2022; Wittmayer and Loorbach, 2016). Uneven capacities across municipalities privilege well-resourced cities—those with technical expertise, financial reserves, and political backing—while marginalizing less-equipped locales (Beretta and Bracchi, 2023; Kirchherr et al., 2023; Nagorny-Koring and Nochta, 2018). Accelerated timelines and resource constraints exacerbate these dynamics, curtailing meaningful experimentation and undermining reflexive feedback loops essential for scaling innovations (Dóci et al., 2022). Addressing these barriers demands governance designs that explicitly integrate equity, institutional reform, and systematic capacity-building to dismantle silos, rebalance power, and enable broad-based, enduring urban transformation.

2.2 Urban Transformative Capacities

While the above mentioned governance framework underscore the importance of long term, participatory, experimental, and reflexive processes, they often under-specify the concrete capacities required for cities to enact such processes effectively—especially under the time pressures and institutional constraints of real-world implementation. As a result, many urban efforts risk being aspirational rather than operational. To address this gap, we turn to the concept of urban transformative capacity (Wolfram, 2016), which foregrounds the institutional, organizational, and social competencies that underpin a city's ability to orchestrate systemic change. By shifting from abstract governance ideals to diagnostic capacities, we can more precisely assess where urban transformation succeeds or falters, and how mission-oriented frameworks like the Cities Mission might function as catalysts for cultivating these capacities or not. The Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework offers a robust, empirically grounded structure to carry out this task.

Governance scholarship converges on the view that “capacity”—the bundle of human, organizational, and institutional competencies—constitutes the linchpin of systemic change, enabling actors to design, implement, and sustain complex interventions (Borgström, 2019; Castán Broto et al., 2019; Haindlmaier et al., 2021; Wolfram et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2015). Foundational policy-capacity research delineates three core dimensions: analytical foresight (e.g., evidence appraisal and scenario planning), operational coordination (e.g., program delivery and inter-departmental alignment), and political legitimacy (e.g., stakeholder engagement and advocacy). Each of them operate across individual, organizational, and systemic scales, with shortcomings in any domain risking implementation breakdown (Wu et al., 2015).

Complementary resilience and adaptive-governance studies underscore the indispensability of social-learning networks and institutional flexibility for navigating uncertainty and maintaining adaptability (Folke et al., 2010; Simmons et al., 2018). Collaborative-governance scholarship further identifies facilitative leadership, trust-building, and conflict-management capacities as prerequisites for eliciting stakeholder buy-in and co-producing context-sensitive solutions (Emerson et al., 2012). Meanwhile, dynamic capabilities theory elucidates how organizations sense emerging trends, mobilize resources, and reconfigure structures to seize new opportunities (O'Reilly and Tushman, 2008; Teece, 2007). Despite the breadth of insights these streams offer, they tend to address either system resilience, policy implementation, collaborative processes, or firm-level strategy in isolation, lacking a unified schema tailored to the multi-scalar, socio-technical complexity of urban governance.

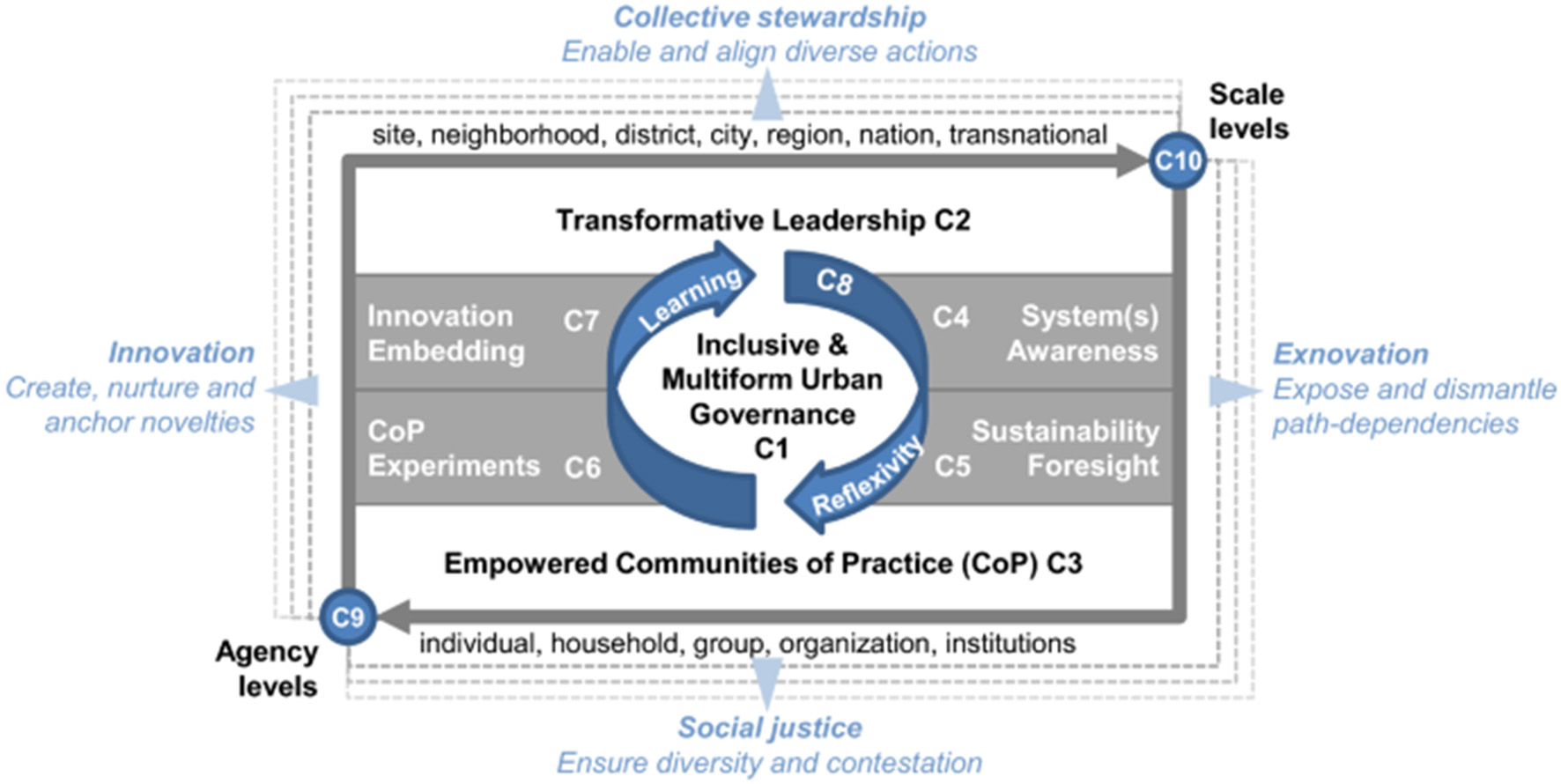

To bridge this gap, the Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework distills ten interrelated capacities—ranging from inclusive co-creation and reflexive learning to strategic leadership and resource mobilization (see Figure 1 and Table 1)—that reflect “the collective ability of the stakeholders involved in urban development to conceive of, prepare for, initiate and perform path-deviant change toward sustainability within and across multiple complex systems that constitute the cities they relate to” (Wolfram, 2016, p. 126). The framework has a place-based approach and integrates approaches such as urban transition management and urban transition labs. It also has since been applied across diverse socio-technical systems (Nevens et al., 2013; Peris-Blanes et al., 2022; Roorda and Wittmayer, 2014; Wolfram, 2018, 2019). Yet empirical research still needs to explore the interplay of socio-technical systems (Kanger et al., 2021), emerging governance challenges (Castán Broto et al., 2019; Castán Broto and Westman, 2020), and co-production processes in European urban areas (Haindlmaier et al., 2021).

Figure 1

Urban Transformative Capacities. Source: Wolfram, 2019.

Table 1

| Urban Transformative Capacities (UTC) |

|---|

|

C1. Inclusive, multiform urban governance

Citizens, civil society groups and private enterprises engage directly with the government through formal bodies and informal networks. Previously marginalized stakeholders are identified and supported. Intermediaries span sectors and scales to foster trust, a shared discourse and coordinated action. |

|

C2. Transformative leadership

Leaders drive systemic change by convening open problem-solving forums, articulating clear sustainability visions, mobilizing support and inspiring broad participation. They bridge local, regional and global levels to maintain political backing and resource flows. |

|

C3. Empowered and autonomous communities of practice (CoP)

CoP identify local social needs, organize themselves and secure resources—information, skills, space and funding—to act autonomously. These groups form coalitions that strengthen their autonomy and collective impact. |

|

C4. System awareness and memory

Systematic routine analyses map and understands connections among cultural, structural and practical elements. Lessons from past initiatives are documented and path dependencies—physical, institutional and cognitive barriers—are explicitly addressed. |

|

C5. Urban sustainability foresight

Diverse actors co-produce transdisciplinary knowledge, craft shared visions for radical change and develop alternative scenarios. These foresight exercises build commitment and guide long-term planning toward resilient urban futures. Collective foresight exercises build commitment and anticipation of long-term urban trajectories. |

|

C6. Community-based experimentation

Place-based, vision-guided experiments are co-produced as safe-to-fail trials to established policies, technologies and practices, generating transformational knowledge and catalyzing social learning. |

|

C7. Innovation embedding and coupling

Proven pilots are scaled and institutionalized by securing resources, forming coalitions and adapting regulations. Reflexive adjustments ensure lasting uptake and system integration. |

|

C8. Reflexivity and social learning

Reflexive monitoring is conducted across all dimensions, combining formal evaluations and informal reflection formats, integrating insights into ongoing processes for continuous adaptation. |

|

C9. Working across human agency levels

Capacity-building spans individuals, households, groups, organizations and networks, ensuring development of skills, knowledge and agency from grassroots to city-wide institutions. |

|

C10. Working across political-administrative levels and geographical scales

Collaboration links neighborhood, municipal, regional, national and transnational actors. Integrated data flows and governance processes ensure local initiatives inform higher-level policies and vice versa. |

The Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework. Source: Wolfram et al. (2019).

UTC's ten capacities are grouped into three categories: agency and interaction (C1–C3), with stakeholder participation, transformative leadership, and empowered communities; core development processes (C4–C8), with system awareness, foresight, experimentation, innovation embedding and reflexive learning; and relational dimensions (C9–C10), multi-level and multi-scale integration.

Crucially, the framework also highlights a set of development factors—such as fostering social capital, available financial and human resources, and identification of exogenous landscape pressures—that determine how and when these capacities emerge and mature in specific urban contexts (Wolfram, 2016). By combining these enabling conditions with the ten capacity components, UTC offers a nuanced, operationally precise tool for diagnosing both the strengths and the preconditions of transformative urban governance.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Context

Spain provides a particularly relevant context for analyzing the development of urban transformative capacities under the Cities Mission. It has emerged as a frontrunner in the Cities Mission, supported by multi-level agreements with national and regional authorities (NetZeroCities, 2023). By late 2023, seven Spanish cities had submitted their CCCs, with five—Madrid, Valencia, Valladolid, Vitoria-Gasteiz, and Zaragoza—receiving the EU Mission Label1 in the first round (out of ten in Europe), followed by Sevilla and Barcelona in March 2024 (citiES, 2025). These cities began implementing CCC frameworks, however, electoral turnover in the 2023 local elections introduced new leadership in several cities, while budgetary pressures and sustaining deep, inclusive public engagement remains ongoing tests of Spain's collaborative model (Brown, 2021).

To support these efforts, the national platform CitiES2030 was launched in late 2022 by EIT Climate-KIC (the EU's Knowledge and Innovation Community dedicated to climate innovation, funded by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology) and the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, with government backing. In coordination with NetZeroCities, the European initiative supporting Mission cities through systemic innovation and capacity building, and the EU Mission Secretariat, the platform facilitates collaboration and decarbonization across mission cities. It promotes peer exchange, capacity-building workshops, and joint initiatives in a multi-city building retrofit programme (EIT Climate-KIC, 2023a,b). Additionally, in Spain, eight non-mission municipalities also participate in urban decarbonization through citiES 2030 (EIT Climate-KIC, 2023a).

3.2 Research design

This study adopts a qualitative, multi-case research design to investigate the transformative capacities of eight Spanish municipalities engaged with the EU Climate-Neutral Cities Mission. Seven of these—Barcelona, Madrid, Seville, Valencia, Valladolid, Vitoria-Gasteiz, and Zaragoza—were among the first cohort of 112 European cities selected to participate. Notably, five cities (Madrid, Valencia, Valladolid, Vitoria-Gasteiz, and Zaragoza) received the prestigious Mission Label, placing them among the first ten European cities to do so and underscoring their pioneering role in the program. To broaden comparative insights, two additional applicant cities—Pamplona and Logroño—were included based on their active participation in the CitiES2030 platform, which facilitates peer learning, collaborative governance, and knowledge exchange among Mission stakeholders.

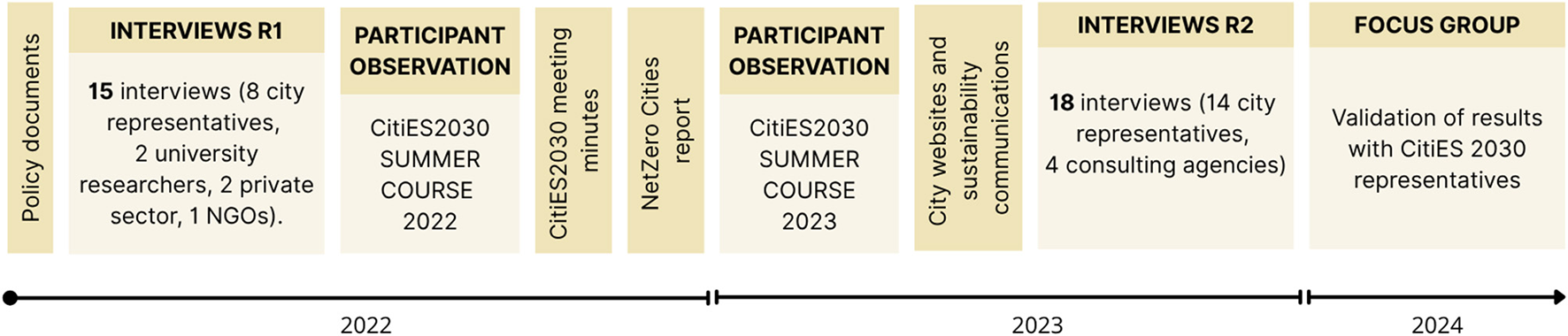

As illustrated in Figure 2 (Author's elaboration), the research combines primary and secondary data sources. Primary data were collected through 28 semi-structured interviews (Table 2) conducted in two waves. The first round (June–October 2022, n = 14) included a diverse array of stakeholders—municipal officials, technical staff, researchers, and NGO representatives—to explore perceptions of capacity needs, barriers, and enabling factors. The second round (September 2023–February 2024, n = 14) focused specifically on city officials and consultancy actors directly involved in drafting Climate City Contracts (CCCs), delving into emerging implementation challenges and adaptive responses. Consultants were included in this phase due to their strategic importance, identified in the first wave. Both interview phases were carried out in parallel with the annual CitiES2030 summer course in Santander—a 1 week immersive workshop promoting peer learning and reflective dialogue on urban transformation. This setting also allowed for participant observation (Corbetta, 2003; Valles, 1997). Additionally, a focus group with four CitiES2030 representatives was convened to validate preliminary findings and foster interpretive co-production.

Figure 2

Methodology of the research, mixing primary and secondary sources. Authors' own elaboration.

Table 2

| 1st round | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Mission city | Stakeholder type | Organizational role | |

| Cities | ||||

| 1 | Barcelona | Yes | Municipal official | Commissioner for Agenda 2030 |

| 2 | Logroño | No | External consultant | Project Coordinator |

| 3 | Madrid | Yes | Municipal official | Researcher and Project Coordinator |

| 4 | Pamplona | No | Municipal official | Deputy Director, Energy and Climate Change |

| 5 | Sevilla | Yes | Municipal official | Director, Strategic Office |

| 6 | Valencia | Yes | Municipal official | Head of the Innovation Service |

| 7 | Valladolid | Yes | Municipal official | European Projects Coordinator |

| 8 | Vitoria | Yes | Municipal official | Deputy Mayor and Councilor for Territory and Climate Action |

| 9 | Zaragoza | Yes | Municipal official | Head of European Funds Projects Office |

| Academia | ||||

| 10 | Universidad Politècnica de Madrid | Researcher at ITD | Researcher and Project Coordinator | |

| 11 | Universitat Politècnica de València | Researcher | Vice-Rector for Sustainable Development | |

| 12 | Universidad de Valladolid | Researcher | Technical Director, Campus Development Office | |

| Public sector | ||||

| 13 | CENER (National Center of Renewable Energy) | Researcher | R and D Projects Advisor | |

| NGO | ||||

| 14 | Oxfam | NGO representative | Social Justice and Policy Advisor (Observer) | |

| 2nd round | ||||

| Name | Mission city | Stakeholder type | Organizational role | |

| Cities | ||||

| 1 | Barcelona | Yes | Municipal official | Administrative Assistant at Barcelona City Council |

| 2 | Madrid | Yes | Municipal official | Climate Change Service, Office of Urban Planning, Environment and Mobility |

| 3 | Madrid | Yes | Municipal official | Technical Advisor for Climate Change |

| 4 | Sevilla | Yes | Municipal official | Agency of Energy and Sustainability—Seville City Council |

| 5 | Sevilla | Yes | Municipal official | Agency of Energy and Sustainability—Seville City Council |

| 6 | Valencia | Yes | Municipal official | Valencia Climate and Energy Foundation technician |

| 7 | Valladolid | Yes | Municipal official | European Project Technician |

| 8 | Valladolid | Yes | Municipal official | European Project Technician |

| 9 | Vitoria | Yes | Municipal official | Sustainability, Climate, and Energy Service |

| 10 | Zaragoza | Yes | Municipal official | Environment, Climate Action, and Public Health Office Zaragoza City Council |

| Private sector | ||||

| 11 | CIRCE | Consultancy | Project manager | |

| 12 | TechFriendly | Consultancy | Climate Action Office | |

| 13 | Cartif | Consultancy | Director | |

Overview of participants interviewed.

Each interview was structured to operationalize the ten dimensions of the Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework (Table 1), combining diagnostic and prescriptive perspectives. The interview protocol comprised four modules: (1) stakeholders' institutional roles in the city's sustainability transitions; (2) UTC capacities; (3) systemic barriers; and (4) solution-oriented reflection, encouraging participants to propose actionable interventions—such as training programs, governance reforms, or pilot projects—to address identified capacity gaps.

All interviews and the focus group were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using NVivo and Taguet software. The analysis followed a two-stage coding strategy aligned with established qualitative procedures. First, deductive coding (Braun and Clarke, 2013; Clarke and Braun, 2017), guided by the ten dimensions of the Urban Transformative Capacity (UTC) framework, was used to identify pre-defined capacity components. A structured codebook was developed for this purpose, including operational definitions and examples, which ensured consistency across cases. Second, inductive thematic analysis (Thomas, 2003) was applied to identify novel, context-specific patterns—such as the reliance on external consultants and early-stage institutional learning—that extended beyond the initial framework. Two researchers independently coded all transcripts. Inter-coder reliability was assessed on a 20% subset, with discrepancies resolved through iterative discussion and joint refinement of code definitions. Analytic memos were maintained to document emerging insights, reflections and cross-case comparisons.

To enhance robustness, findings were triangulated across interview data, focus-group insights, and two key secondary sources: City Needs, Drivers, and Barriers toward Climate Neutrality (NetZeroCities) and CCC Challenges, Learnings, and Next Steps (CitiES2030). This triangulation was particularly important given the early-stage nature of the Mission, ensuring that interpretations were grounded in systematically validated, multi-source evidence.

When interpreting the findings of this study, it is important to consider its scope and contextual particularities. First, it focuses solely on Spanish municipalities, which may limit generalizability, though their leadership within the Mission provides strategic relevance. Second, the fieldwork was conducted at an early implementation stage, when cities were still drafting their Climate City Contracts. This reflects a period of institutional learning, uncertainty, and experimentation. However, it also offers valuable insights into emerging capacities and foundational conditions. Third, while a range of actors was included, institutional voices are predominant (also in the Mission process itself), potentially underrepresenting critical or community perspectives. Lastly, despite double coding and reliability checks, qualitative analysis inherently involves interpretive judgments. These limitations were addressed through triangulation with secondary sources, participant observation, and a validation focus group. Longitudinal research is recommended to track the evolution of transformative capacities as implementation progresses.

Consistent with the principles of collaborative research (Lieberman, 1986; Shani et al., 2007; Wittmayer and Schäpke, 2014), the study combines researchers with different degrees of involvement in Mission processes, alongside external observers who provide analytical distance. Two authors acted as observers, increasing their involvement in the Mission in Spain throughout the research, engaging directly with municipalities and contributing with participant observation that enriched understanding of the Mission's dynamics. A third author served as an external observer with no direct participation in Spanish Mission activities, contributing analytical distance and expertise in sustainability transitions and governance processes. In contrast, two team members were directly engaged in Mission-related processes at national and municipal levels, providing contextual knowledge, access to key actors, and insight into ongoing policy developments. This combination of insider and outsider perspectives enabled continuous reflexive dialogue throughout the research process and strengthened the credibility and transparency of the analysis.

4 Results

4.1 C1–C3: governance and collective agency

4.1.1 Inclusive, multiform urban governance (C1)

Interviewees across all cities described efforts to build Inclusive, Multiform Urban Governance (C1) mechanisms during the development of their Climate City Contracts (CCCs), though these were shaped by procedural constraints, limited resources, and tight timelines. Stakeholder engagement tended to be informational or consultative, primarily involving accessible and established actors such as private-sector clusters, universities, civil society organizations, and business forums. For instance, Zaragoza secured 117 letters of support from a range of stakeholders. Valencia built the Energy Transition Arena—an initiative developed under a European project within its Urban Agenda planning—as a participatory co-creation space that later informed the CCC, though it was not originally designed for that purpose. Other examples are Deep Demonstrations to foster multi-actor collaboration across sectors, while Barcelona employed citizen assemblies as part of its broader participatory architecture. However, no city reported institutionalized co-decision-making, or dedicated strategies for reaching marginalized or underrepresented groups within the Mission scope.

At the moment of the interviews, governance remained centralized and top down in municipal units responsible for European funds, innovation, or sustainability, with coordination frequently concentrated in a single person or small team, identifying administrative frontrunners. Siloed structures across departments were widely cited as barriers to integration and just a few cities reported explicit political support (Valencia, Zaragoza and Vitoria-Gasteiz). Intermediary actors, particularly through the CitiES2030 platform, were pointed out as instrumental in providing technical assistance, fostering inter-city collaboration and learning, maintaining continuity during political transitions and for building alliances with European counterparts—such as Sweden's national Mission platform. Several accounts emphasized the pivotal role of CitiES2030 in facilitating locally grounded support, “not only in the technical aspects but also in creating a sense of community among the Spanish cities” (I15).

While NetZeroCities advisors were acknowledged, their support was generally perceived as less impactful and less operationally relevant to local needs: they were “mostly learning from the cities [...] far from the way public administrations work” with “a private logic that doesn't fit our reality” (I15). Others described their approach as “more conceptual than practical” (I17) recognizing that they have been “useful for understanding the European logic and what is expected from the Missions, but in terms of hands-on support for projects or governance, it has not been very operational” (I2), comparing the work of CitiES2030, being “the ones helping us move forward week by week” (I1).

Interviewees acknowledged that while academic partners or experts were sometimes involved—such as in Madrid, and Valladolid—these collaborations were typically short-term and instrumental, “often limited to producing the documents required by the Mission—useful but not transformative or sustained over time” (I2).. Valencia established the city–university partnership to institutionalize collaboration and position the university as a living lab for decarbonization, but was interrupted after the 2023 government change.

4.1.2 Transformative leadership (C2)

Transformative Leadership (C2) manifested in varied forms depending on city-specific political contexts. Prior to the 2023 municipal elections, Valencia, Zaragoza, Barcelona, and Vitoria-Gasteiz demonstrated high-level political support for the Mission, enabling stronger alignment across municipal departments and policy agendas. In contrast, Madrid, Seville, and Valladolid approached the Mission through more technocratic channels, driven largely by administrative departments and intermediaries without explicit political endorsement. Post-election shifts saw a general trend toward “economic opportunities and attracting investment rather than transformation” (I2), with Valladolid being an exception reinforcing political commitment. Across all cases, individual leadership—whether technical or political—was a decisive factor in sustaining momentum and motivating action. In Zaragoza, “leadership from specific people—our former mayor, the current mayor, and the team behind them—has been fundamental. When leadership is clear, projects advance” (I19), while others warned that “in many cities, it depends on one or two people who really believe in it. If they leave, everything slows down” (I2). As emphasized in Seville, “we need to avoid centering everything in one person, because if that person leaves, the process collapses” (I14).

4.1.3 Empowered and autonomous communities of practice (C3)

The presence of Empowered and Autonomous Communities of Practice (C3) remained disconnected from mission conceptualization and action planning. While cities engaged institutional and sectoral actors, such as universities and business forums, there was little evidence of community-led structures or practices supporting autonomous civic agency and the existing ones were “rather symbolic spaces” (I16). Grassroots participation was largely absent, and mechanisms to identify or address social needs were not in place. Engagement formats tended to be framed by procedural goals rather than long-term empowerment. Still, several participants regarded the CCC process as a stepping stone toward more inclusive forms of participation, emphasizing that “future rounds of the Mission should open space for smaller initiatives and social actors that are not yet represented” (I1).

4.2 C4–C7: system awareness, foresight, experimentation, and innovation

4.2.1 System(s) awareness and memory (C4)

Interviewees across cities described partial and uneven progress toward System(s) Awareness and Memory (C4). Municipalities conducted baseline assessments to support their Climate City Contracts (CCCs), most relying on pre-existing plans or data due to financial, human, and time constraints. These diagnostics were typically consultant-led and focused primarily on emissions or technical infrastructures with limited social and integrated, cross-sectoral perspectives. As one interviewee explained, “we have many data and studies, but the problem is how we analyze them… analyses are often fragmented and not realistic” (I16). Another described that “the diagnosis exists, but it was made before the Mission—it needs to be updated to integrate new perspectives” (I14).

For instance, cities like Valladolid, Zaragoza, and Madrid developed thematic assessments, yet overlooked the systemic interdependencies between climate, institutional, and cultural dimensions. Interviewees highlighted that including actors such as schools, foundations, and business organizations reinforced the importance of adopting systemic approaches to urban transformation. As stated, “we tried to bring together different municipal areas, but each department holds its own information; there is no integrated picture” (I19).

Despite these limitations, the Mission was pointed to help to prompt new internal dialogues on entrenched institutional dynamics. Cities began to surface bureaucratic rigidities and departmental silos as critical barriers to transformation, as well as workload (“the day-to-day inertia and the most basic tasks can completely consume everything” (I14)). This awareness was notably strong in places like Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, and Zaragoza, where interviewees explicitly pointed to path dependencies, outdated regulatory frameworks, and fragmented responsibilities as key obduracies. Though no city had tools in place to address these structurally, participation in platforms like CitiES2030 and NetZeroCities encouraged, raising awareness of systemic blind spots and institutional inertia. However, immediate demands of CCC development contributed to sideline these issues, prioritizing document development.

4.2.2 Urban sustainability foresight (C5)

Efforts toward Urban Sustainability Foresight (C5) remained in an early phase across Spanish Mission cities. Although all municipalities endorsed the 2030 climate neutrality target, most developed Climate City Contracts (CCCs) as “an administrative exercise rather than as an opportunity to rethink their model of city” (I3). Long-term planning was typically led by small technical teams, with limited participation from broader municipal departments or civil society. As noted by interviewees, long term planning was a challenge since “departments tend to plan for the next project, not for the next decade” (I11), recognizing the need “to move from political cycles to future-oriented planning” (I5) and the important role of the Mission in that aspect. Several interviewees acknowledged that the Mission encouraged a more systemic perspective, yet co-produced strategic visions—integrating economic, cultural, and social justice dimensions—were not fully developed. Strategic direction often hinged on the priorities of individual staff members, underscoring a lack of institutional mechanisms to support participatory foresight. While scenario-thinking exercises were introduced via CitiES2030, they had yet to be embedded in formal governance routines.

4.2.3 Diverse community-based experimentation (C6)

This emerging strategic orientation toward innovation intersected with Diverse Community-Based Experimentation (C6). Interviewees described early-stage experimentation, especially in governance formats, more than in technical or community-driven pilots. Cities leveraged the Mission to reframe existing initiatives and test new approaches—such as Valladolid's regulatory sandbox and the urban regeneration project Madrid Nuevo Norte2 part of broader innovation narratives. Although many of these initiatives were not initiated by the Mission itself, its framework provided “visibility and legitimacy to projects that were already underway, because now they can be linked to a European framework and to climate neutrality” (I2) and “give them coherence under the same umbrella” (I11), reinforcing “the city's commitment to continue on that path of transition” (I19). Some interviewees viewed the Mission as a “safe space” to try out novel ideas, with new institutional language—like living labs and transition arenas—gaining traction in local discourse. However, experimentation remained consultant- or administration-driven, and evaluation or scaling mechanisms were rarely in place, as noted “the real challenge is how to apply [the strategies] and follow them up” (I16). Interviewees viewed funding as a key challenge for experimentation, noting a reliance on future Mission-linked resources that, while expected, remain uncertain and risky at this stage.

4.2.4 Innovation embedding and coupling (C7)

Meanwhile, the capacity for Innovation Embedding and Coupling (C7)—embedding innovation within municipal planning and regulation—was widely acknowledged as a significant challenge. Most cities had yet to institutionalize experimental learnings or integrate them into strategic decision-making processes. As one interviewee noted, “it is still difficult to incorporate transversal dynamics in municipal work because day-to-day management absorbs most of the time” (I1). Supplementary instruments like investment portfolios and climate roadmaps were emerging, but often lacked financial anchoring, legal support, or departmental integration, being funding a challenge here to integrate the Climate Agreement into the city's planning tools, “because it doesn't have its own funding line yet” (I17). Rigid governance structures and outdated procurement norms were identified as major mainstreaming limitations. Nonetheless, platforms like CitiES2030 were seen as critical enablers, providing continuity, peer learning, and access to European policy making environments that could support long-term embedding of innovation.

4.3 C8: reflexivity and social learning

Interviewees did not identify monitoring strategies based on reflexive processes across the previously analyzed capacities (C1–C7). While they recognized the importance of fostering reflexivity and critically reflecting on and questioning progress, their focus at this stage was primarily on gathering data for the technical aspects of sustainability, with a primary focus on collecting data for technical sustainability aspects using traditional methods like monitoring and evaluation as the effort was “focused on preparing the Climate Contract, not yet on evaluating or monitoring” (I17). When asked why, a significant challenge identified was the resource-intensive requirement for quality data, lack of know-how and prioritizing other aspects such as developing the CCC, attributed to the early stages of the EU Cities Mission.

Despite these obstacles, the value of knowledge exchange was recognized, especially among stakeholders from similar cultural contexts and governance systems, such as the Spanish cities. CitiES2030 was widely praised as a safe space “to move forward and to keep cities connected, sharing experiences and learning from each other” (I2), essential for critical debate, and practical problem-solving. It also helped to introduce reflexive formats—such as weekly webinars, summer workshops, and thematic modules—that encouraged officials to step back from compliance tasks and question underlying assumptions.

4.4 C9–C10: multi-level engagement and governance coordination

4.4.1 Working across human agency levels (C9)

Across the Spanish Mission cities, the working across human agency levels (C9) remained primarily concentrated at the institutional and organizational levels, with strong involvement from municipal departments, consultancy firms, and academic institutions. The private sector was widely seen as an accessible and influential actor, often engaged through existing networks or climate-related projects. However, other social agents—particularly citizens, community organizations, and grassroots actors—were largely absent from the development of the city's strategies.

Several interviewees noted that participation strategies were not conceived from a systemic or inclusive logic but rather emerged from project-based dynamics, shaped by tight deadlines and internal administrative structures. As one participant noted “deadlines have been extremely tight, so there was little room to build a participatory process; the focus was on delivering the document” (I10). The process often reflected a task-oriented, bureaucratic exercise, driven by a small group of technicians or consultants. As one interviewee critically stated, the CCC “was drafted by four or five people” (I8) and framed more as a compliance document than a co-produced roadmap. Another remarked that “the whole European Commission approach reduced the process to filling in a document” (I4) which undermined initial expectations of inclusivity and co-creation. Although the intent to build cross-sectoral coalitions was often articulated, these ambitions were not yet matched by concrete strategies or institutional mechanisms as noted by several interviewees, “the challenge is not writing projects but generating structures that make collaboration possible in the long term” (I13).

4.4.2 Work across political-administrative levels and spatial scales (C10)

Regarding the Work Across Political-Administrative Levels and Spatial Scales (C10) although CCCs were formally endorsed through state–city agreements, mostly driven by CitiES2030, many interviewees characterized these as symbolic formalities without operational collaboration. Nonetheless, the EU Cities Mission provided a shared governance narrative, linking local CCCs to European ambitions and enhancing political cohesion within cities. “The Mission has allowed us to connect our local strategies with the European Green Deal; it gives coherence and visibility to what we are already doing” (I4). Participation in national and international platforms—most notably CitiES2030, but also networks like NetZeroCities or C40—was widely seen as essential for legitimacy and multi-scale alignment. These platforms helped cities build visibility, share technical know-how, and explore broader climate frameworks. As one participant put it, “being part of these European networks gives us credibility and political support to continue advancing locally” (I3). For some municipalities, involvement with the EU Adaptation Mission3 provided a pathway to engage regional actors and further multilevel integration.

5 Discussion

The Cities Mission seeks climate neutrality by 2030 through aligned goals, policies, timelines and collective action. This presumes cities already hold capacities such as the ability to coordinate across governance levels, mobilize funding, engage diverse stakeholders, and embed innovation into governance arrangements (Mazzucato, 2017; Wanzenböck et al., 2020). Yet whether such capacities exist—or can be developed through the Mission, and how—remains uncertain. What emerges across the cities studied is a varied picture, where some capacities strengthen while others remain more difficult to embed within municipal structures, directly influencing each city's trajectory.

5.1 From procedural to transformative capacities

The Cities Mission rests on the assumption that cities can act as orchestrators of systemic change once the appropriate frameworks and incentives are in place (Mazzucato, 2018). Yet findings from Spanish Mission cities reveal a persistent tension between ambition and capacity: while the Mission mobilized leadership, collaboration, and experimentation, capacities for institutional embedding, learning, and inclusivity advanced more slowly. Enduring administrative inertia and path-dependencies hindered the translation of Mission ambitions into everyday routines—a limitation long noted in transition studies but insufficiently addressed in practice (Kern, 2023; Köhler et al., 2019; Frantzeskaki et al., 2017). Across cases, capacities emerged as relational processes shaped by political will, organizational design, and temporal and resource pressures. The Mission's procedural urgency encouraged visible forms of mobilization—plans, committees, and partnerships—while capacities that depend on time, trust, and iterative learning remained fragile.

Leadership, experimentation, and coordination illustrate this tension. Leadership created momentum but remained fragile when not anchored in wider institutional and political structures (Braams et al., 2022; Frantzeskaki et al., 2016). Experimentation faced tight timelines and scarce resources that often led to reframing existing projects under the Mission's umbrella, improving coherence and visibility but raising questions about the depth of change (Wittmann et al., 2020). The lack of reflexive mechanisms also risked reinforcing rather than challenging established governance logics (Frantzeskaki and Rok, 2018; Loorbach et al., 2020; Voß and Bornemann, 2011). Multi-level and cross-sectoral coordination improved alignment across levels but frequently reduced inclusivity, privileging institutional and reachable actors over grassroots (Avelino et al., 2024; Dóci et al., 2022). When participation lacks power redistribution, it legitimizes predefined agendas and hierarchies (Chilvers and Kearnes, 2020), contrasting with transformative capacities, which aim to “disrupt and dismantle existing systems, and simultaneously create and build viable alternatives” (Wolfram et al., 2019, p. 438). Similar dynamics were visible in foresight and systems thinking, which remained narrow and technocratic, centered on carbon metrics and risking reinforcing existing path dependencies when marginalizing alternative imaginaries and contested knowledge (Fastenrath et al., 2023; Hölscher et al., 2019; Scoones et al., 2020).

Taken together, these patterns reveal a procedural mode of mobilization that translates potentially transformative functions into administrative ones—a dynamic also observed in transition governance and mission implementation (Avelino and Wittmayer, 2016; Voß and Bornemann, 2011; Kivimaa et al., 2019). Capacities aligned with administrative and political logics—visible, output-oriented, and measurable—receive stronger institutional backing, while those oriented toward systemic learning, reflexivity, and civic anchoring remain less supported. Such learning-oriented capacities require stability and long-term commitment, which often conflict with the short funding cycles and accountability demands of EU programmes (Hölscher et al., 2020; Frantzeskaki et al., 2016; Nevens et al., 2013). The result is procedural progress without equivalent institutional depth, offering short-term coherence but risking the reproduction of existing routines (Loorbach et al., 2020; Wanzenböck et al., 2020).

5.2 Catalysts of transformative capacity: new actors key in the Mission

Across the Spanish cases, the development of transformative capacity was not solely a matter of institutional design or formal objectives, but emerged through situated catalytic conditions that enabled municipalities to navigate the demands of the Mission. Such conditions—training initiatives, mutual learning exchanges, access to external expertise, coordination and support mechanisms, etc.—were largely facilitated by actors acting as relational infrastructures (Neij and Heiskanen, 2021), such as CitiES2030, universities and civil servants weaving together other actors, resources and practices across governance levels.

CitiES2030 was pivotal in the Mission's early stages. It supported overstretched municipal teams, aligned climate strategies, and guided cities through uncertainty, gradually resembling a community of practice where municipalities built trust, shared experiences, and co-developed responses to shared challenges (Wenger, 2011; Wolfram, 2016). It also provided multi-scalar coordination with national and EU goals, reflecting an “ecology of intermediation” (Barrie and Kanda, 2020; Soberón et al., 2022). During weak political leadership, as in the 2023 elections, CitiES2030 stabilized and legitimized ongoing processes, sustaining agendas through advocacy and stewardship (Ehnert, 2023; Tanja Manders et al., 2020). Unlike standardized European programmes such as NetZeroCities or the City Advisors, its locally grounded facilitation proved more effective in embedding transformative practices, confirming the value of context-sensitive intermediation (Kendall and Kendall, 2012; Kivimaa et al., 2019; Soberón et al., 2022).

Universities and research centers also contributed to transformative capacity when engaged as embedded partners rather than external providers, combining expertise, infrastructure and legitimacy but also contributing to reflexivity and, at times, acting as epistemic intermediaries between technical models and political judgment (Coenen et al., 2012; Hansen and Coenen, 2015; Peris-Blanes et al., 2022).

The Mission also relied on the adaptive work of civil servants, who became key enablers in contexts of limited resources and institutional rigidity. Directly exposed to the Mission's operational demands, they mobilized knowledge, aligned stakeholders, and adapted procedures to evolving circumstances, exemplifying administrative entrepreneurship (Borins, 2001; Roberts and King, 1991): innovation from within through negotiation, persistence, and informal coordination. Acting through relational agency rather than hierarchical authority, these officials sustained mission processes through iterative learning and continual adaptation. Their contribution underscores the significance of everyday bureaucratic work and the need to recognize the situated, often invisible efforts that translate systemic ambition into practice under constrained conditions.

Together, these actors performed distinct yet interdependent roles that nurtured the development of transformative capacity. Their combined activity formed a multilayered support structure weaving procedural, organizational, and relational mechanisms into a coherent, adaptive system. From the perspective of urban sustainability transitions governance, these catalytic processes show how transformation often depends on the connective architectures that link policy ambition with situated practice, turning external frameworks into lived processes of collective learning and coordination. Intermediation emerges not as a supporting function but as a governance architecture in itself—an ecology of actors that stabilizes coordination, facilitates learning, and connects transition processes across scales. These findings also extend current understandings of urban transformative capacity by evidencing its distributed nature—emerging through inter-organizational collaboration and intermediary infrastructures rather than within single institutional domains.

5.3 Limiting urban transformative capacity: between urgency and externalization

The Climate Neutral Cities Mission represents a significant reorientation of urban governance, aiming to advance transitions within compressed timeframes. In Spain, the interaction between urgency, institutional capacity, and procedural design has influenced how the Mission has been implemented. Across the cases examined, municipalities worked under considerable pressure to deliver Climate City Contracts (CCCs) within a two-year period, a condition that structured how goals were framed, resources mobilized, and collaboration organized.

While understandable given the 2030 neutrality target, this urgency often led to procedural acceleration of coordination, learning and engagement. The result was a widespread instrumentalization of the CCC process as a technocratic planning task, privileging deliverables over deliberation and compliance over co-production (Reale, 2021; Wanzenböck et al., 2020), with ambitions for experimentation, inclusivity and reflexivity sometimes constrained by more familiar logics of performance and administrative control (Ehnert et al., 2018). In this sense, the Mission's temporal structure facilitated commitment and visibility, but at times reduced opportunities for more adaptive and reflective governance.

Many municipalities addressed these demands by engaging external consultants, particularly where internal capacity was limited. In some cases, close collaboration with officials supported visioning, data integration, and strategy alignment, indirectly strengthening local capacity (Kivimaa et al., 2019; McCrory, 2022). More often, however, involvement remained peripheral, leading to “consultancy drift” (Christensen and Collington, 2024), where external actors produced key documents with limited political or organizational ownership. This reflects critiques of consultocracies in urban governance, where decision-making is mediated by technical expertise, reducing internal learning and political agency (Mazzucato and Collington, 2024; Scott and Carter, 2019). Consultants may enhance procedural efficiency but seldom replace internal leadership, institutional memory, or cross-departmental integration.

This pattern aligns with wider transformations in the political economy of public administration, where outsourcing and project-based logics reshape who holds knowledge, authority, and accountability in urban governance (Christensen and Lægreid, 2020; Seabrooke and Sending, 2022). Reliance on external expertise may also affect the perceived legitimacy of the transition process, as decision-making shifts from democratically accountable institutions to technical intermediaries (Sørensen and Torfing, 2021).

The Spanish experience thus reveals a tension inherent to mission-oriented governance: the same urgency that mobilizes political will and coordination can, under certain conditions, reinforce externalization, dependence and proceduralism, constraining longer-term capability-building such as reflexivity, system awareness and strategic foresight (Hölscher et al., 2018; Wolfram, 2016). However, while external expertise can reinforce dependency, it may also function as a boundary resource that expands cognitive and organizational repertoires within constrained administrations (Kivimaa et al., 2019; McCrory, 2022). Balancing acceleration with reflection, and procedural delivery with institutional learning, appears essential if missions are to cultivate the deeper capacities.

6 Conclusions

This paper examined the Cities Mission as a paradigmatic case of transformation-oriented governance, grounded in the view that missions operate not only as policy frameworks but as structuring logics that reshape how cities govern, innovate, and envision sustainable futures. By focusing on the interplay between institutional ambition and urban capacity, the analysis shifts attention from policy design to the governance capabilities required for systemic change. Rather than assuming cities already possess such capacities—or that ambitious goals automatically generate them—it adopts a capacity-centered perspective to explore how transformative potential is enabled, constrained, and reconfigured through mission-oriented interventions. The analysis therefore invites a more critical engagement with how mission-oriented governance frameworks influence the development—or inhibition—of transformative capacities. The Cities Mission thus serves both as an empirical window into ongoing transitions and as a testbed for rethinking how transformation is governed within the constraints of contemporary urban governance.

Evidence from seven Spanish cities shows that while the Mission has stimulated new forms of leadership, coordination, and experimentation, these capacities often remain thin, individualized, and weakly embedded in municipal routines. Deeper capacities—such as reflexivity, civic anchoring, and institutional adaptation—were less developed, constrained by limited resources, siloed structures, and procedural urgency. This reflects a broader tendency of mission governance to privilege visible, measurable outputs over slower, process-oriented work essential for transformation, risking “thin” innovation—surface-level novelty without lasting reform. Yet early experiences also suggest potential to strengthen systemic capacities if approached as a long-term, adaptive process.

Locally grounded intermediaries and national platforms emerged as relational infrastructures that stabilized coordination and fostered learning under constraint. Their contribution contrasts with the overreliance on external consultancies, which often reduced ownership and internal learning, and with the procedural acceleration that risked undermining precisely those deeper capacities required for durable change. These patterns underscore the importance of understanding capacity development as a distributed process shaped by intermediation, reflexivity, and adaptation, rather than as a linear outcome of policy design.

While the UTC framework proved analytically valuable, its application also invites reflection. Its heuristic potential lies in shifting attention from outcomes to the quality of governance processes. However, its application also revealed certain limitations: while strong in identifying relevant dimensions, the framework offers less guidance on specific actions to develop those capacities, how capacities evolve over time, interact with power dynamics, or become embedded (or not) in institutional routines. Capacities are not just built—they are unevenly distributed, selectively prioritized, and sometimes eroded. Understanding how this happens in practice is crucial to avoid idealized or depoliticized accounts of urban transformation.

The research also speaks to ongoing debates in urban sustainability transitions. It highlights that building transformative capacity is not a matter of institutional design but of sustaining processes of learning, alignment, and adaptation over time. In this sense, the Cities Mission exemplifies both the opportunities and tensions of governing transformation under constraint, providing insights into how urban change is assembled in practice.

Insights from this case point to areas that may warrant further attention. Capacity-building could be considered a central element of the Cities Mission, involving support for institutional learning, civic infrastructures and administrative innovation. Mission instruments might also benefit from placing greater emphasis on the quality of processes—how cities govern, engage and learn—alongside measurable outcomes. Finally, the experience highlights the potential value of sustaining cross-city communities of practice, with platforms such as CitiES2030 seen not only as project-based support but as possible long-term components of European climate governance.

The findings may also inform broader debates on how the Mission-Oriented Innovation approach unfolds across diverse geographic and socio-institutional settings. Although grounded in Europe, the research can offer insights into how missions are locally interpreted, adapted and mediated through governance structures. These results may contribute to discussions on barriers and mechanisms for advancing social inclusion in Latin America (Hernández et al., 2021), the creative management of diverse stakeholders in the Middle East and North Africa region (Al-Jayyousi et al., 2023), and the challenges of identity and diversity identified in the Australian context (Fielke et al., 2023).

The research captures an early phase of the Climate City Contracting (CCC) process; many governance arrangements, collaborative mechanisms, and anticipatory practices are still evolving and may shift substantially as implementation progresses. Future research could address current limitations by adopting longitudinal designs and examine the continuity of the Mission's implementation in a more mature step to trace how transformative capacities evolve, identifying which activities and policy instruments have effectively strengthened specific capacities, and capture a wider range of perspectives, including those of citizens, niche actors, and policymakers.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans given the nature of the research. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AE-C: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP-B: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. JM-S: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. GP-S: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SS-C: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. OU: Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by the European Union (EU) Horizon 2020 NetZeroCities Project under Grant Number 101036519.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1694543/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^A formal recognition awarded by the European Commission to cities with approved Climate City Contracts, signaling readiness to access funding and implement their neutrality strategies.

2.^ https://creamadridnuevonorte.com/—as

3.^The EU Mission on Adaptation to Climate Change supports European regions and communities in strengthening resilience to climate impacts, aiming for at least 150 regions to develop adaptation plans by 2030 (European Commission, 2025).

References

1

Al-Jayyousi O. Amin H. Al-Saudi H. A. Aljassas A. Tok E. (2023). Mission-oriented innovation policy for sustainable development: a systematic literature review. Sustainability15:13101. doi: 10.3390/su151713101

2

Alkemade F. Hekkert M. P. Negro S. O. (2011). Transition policy and innovation policy: friends or foes?Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.1, 125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.009

3

Avelino F. van Steenbergen F. Schipper K. Steger T. Henfrey T. Cook I. M. et al . (2024). Mapping the diversity and transformative potential of approaches to sustainable just cities. Urban Transform.6, 1–29. doi: 10.1186/s42854-023-00058-8

4

Avelino F. Wittmayer J. M. (2016). Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: a multi-actor perspective. J. Environ. Policy Plann.18, 628–649. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259

5

Avelino F. Wittmayer J. M. Pel B. Weaver P. Dumitru A. Haxeltine A. et al . (2019). Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change145, 195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.002

6

Barrie J. Kanda W. (2020). “Building ecologies of circular intermediaries,” in Handbook of the Circular Economy (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 469–488.

7

Beretta I. Bracchi C. (2023). Climate-neutral and smart cities: a critical review through the lens of environmental justice. Front. Sociol.8:1175592. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.1175592

8

Borgström S. (2019). Balancing diversity and connectivity in multi-level governance settings for urban transformative capacity. Ambio48, 463–477. doi: 10.1007/s13280-018-01142-1

9

Borins S. (2001). The Challenge of Innovating In Government. PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowment for the Business of Government. Available online at: http://businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/BorinsInnovatingInGov.pdf (Accessed August, 2025).

10

Braams R. B. Wesseling J. H. Meijer A. J. Hekkert M. P. (2022). Understanding why civil servants are reluctant to carry out transition tasks. Sci. Public Policy49, 905–914. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scac037

11

Braun V. Clarke V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners.

12

Broto V. C. Westman L. (2019). Urban Sustainability And Justice. London: Zed Books Ltd.

13

Brown R. (2021). Mission-oriented or mission adrift? A critical examination of mission-oriented innovation policies. Eur. Plan. Stud.29, 739–761.

14

Bulkeley H. Betsill M. M. (2013). Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environ. Politics22, 136–154. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2013.755797

15

Bulkeley H. Castán Broto V. (2013). Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr.38, 361–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00535.x

16

Castán Broto V. Trencher G. Iwaszuk E. Westman L. (2019). Transformative capacity and local action for urban sustainability. Ambio48, 449–462. doi: 10.1007/s13280-018-1086-z

17

Castán Broto V. Westman L. K. (2020). Ten years after Copenhagen: reimagining climate change governance in urban areas. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change11:e643. doi: 10.1002/wcc.643

18

Chilvers J. Kearnes M. (2020). Remaking participation in science and democracy. Sci. Technol. Hum.Values45, 347–380. doi: 10.1177/0162243919850885

19

Christensen R. C. Collington R. (2024). New development: climate consulting and the transformation of climate governance. Public Money Manag.44, 461–464. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2024.2353672

20

Christensen T. Lægreid P. (2020). Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: how the Norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Admin. Rev.80, 774–779. doi: 10.1111/puar.13241

21

citiES 2030 (2025). Acuerdos Climáticos / Climate City Contracts. Available online at: https://cities2030.es/en/acuerdos-climaticos/ (Accessed August, 2025).

22

Clarke V. Braun V. (2017). Commentary: Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol.12, 297–298. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

23

Coenen L. Benneworth P. Truffer B. (2012). Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Res. Policy41, 968–979. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014

24

Corbetta P. (2003). Social Research: Theory, Methods And Techniques. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

25

Dóci G. Rohracher H. Kordas O. (2022). Knowledge management in transition management: the ripples of learning. Sustain. Cities Soc.78:103621. doi: 10.1016/j.scs,.2021.103621

26

Ehnert F. (2023). Bridging the old and the new in sustainability transitions: the role of transition intermediaries in facilitating urban experimentation. J. Clean. Prod.417:138084. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138084

27

Ehnert F. Kern F. Borgström S. Gorissen L. Maschmeyer S. Egermann M. (2018). Urban sustainability transitions in a context of multi-level governance: a comparison of four European states. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.26, 101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2017.05.002

28

EIT Climate-KIC (2023a). Radical Collaboration: Spanish Cities Unite for Climate Neutrality Journey. Available online at: https://www.climate-kic.org/news/radical-collaboration-the-core-of-spanish-cities-in-climate-neutrality-journey/ (Accessed August, 2025).

29

EIT Climate-KIC (2023b). The National Platform to Support Spanish Cities Meet Their Climate Goals. Available online at: https://www.climate-kic.org/news/spain-national-platform/ (Accessed August, 2025).

30

Emerson K. Nabatchi T. Balogh S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory22, 1–29. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur011

31

European Commission (2022). EU Missions in Horizon Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

32

European Commission (2025). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, EU Mission, Adaptation to Climate Change. Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2777/5725296

33

Fastenrath S. Tavassoli S. Sharp D. Raven R. Coenen L. Wilson B. et al . (2023). Mission-oriented innovation districts: towards challenge-led, place-based urban innovation. J. Clean. Prod.418:138079. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138079

34

Fielke S. J. Lacey J. Jakku E. Allison J. Stitzlein C. Ricketts K. et al . (2023). From a land ‘down under': the potential role of responsible innovation as practice during the bottom-up development of mission arenas in Australia. J. Responsible Innov.10:2142393. doi: 10.1080/23299460.2022.2142393

35

Folke C. Carpenter S. R. Walker B. Scheffer M. Chapin T. Rockström J. (2010). Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc.15:20. doi: 10.5751/ES-03610-150420

36

Frantzeskaki N. (2022). Bringing transition management to cities: building skills for transformative urban governance. Sustainability14:650. doi: 10.3390/su14020650

37

Frantzeskaki N. Castán Broto V. Coenen L. Loorback D. (2017). Urban Sustainability Transitions. Abingdon: Routledge.

38

Frantzeskaki N. Dumitru A. Anguelovski I. Avelino F. Bach M. Best B. et al . (2016). Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain.22, 41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.008

39

Frantzeskaki N. Rok A. (2018). Co-producing urban sustainability transitions knowledge with community, policy and science. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.29, 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2018.08.001

40

Geels F. W. (2004). From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy33, 897–920. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015

41

Geels F. W. (2011). The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.1, 24–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.002

42

Haindlmaier G. R. Wagner P. Wilhelmer D. (2021). Transformation rooms: building transformative capacity for European cities. Int. J. Urban Plann. Smart Cities2, 48–69. doi: 10.4018/IJUPSC.2021070104

43

Hamann R. April K. (2013). On the role and capabilities of collaborative intermediary organisations in urban sustainability transitions. J. Clean. Prod.50, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.017

44

Hansen T. Coenen L. (2015). The geography of sustainability transitions: review, synthesis and reflections on an emergent research field. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.17, 92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2014.11.001

45

Hernández I. D. Castellanos J. G. Gómez-León A. Bermeo-Andrade H. P. Bautista S. S. (2021). “Mission-oriented innovation policies: an approach to two Colombian cases,” in Policy and Governance of Science, Technology, and Innovation: Social Inclusion and Sustainable Development in Latin América (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 35–54.

46

Hölscher K. Frantzeskaki N. McPhearson T. Loorbach D. (2019). Capacities for urban transformations governance and the case of New York City. Cities94, 186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.037

47

Hölscher K. Frantzeskaki N. McPhearson T. Loorbach D. (2020). Capacities for Transformative Climate Governance in New York City. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 205–240.

48

Hölscher K. Wittmayer J. M. Loorbach D. (2018). Transition versus transformation: what's the difference?Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.27, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007

49

Huovila A. Siikavirta H. Antuña Rozado C. Rökman J. Tuominen P. Paiho S. et al . (2022). Carbon-neutral cities: critical review of theory and practice. J. Clean. Prod.341:130912. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130912

50

IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WG1AR5_all_final.pdf (Accessed August, 2025).

51

Kanger L. Schot J. Sovacool B. K. van der Vleuten E. Ghosh B. Keller M. et al . (2021). Research frontiers for multi-system dynamics and deep transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.41, 52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.025

52

Kendall J. E. Kendall K. E. (2012). Storytelling as a qualitative method for is research: heralding the heroic and echoing the mythic. Australas. J. Inf. Syst.17, 161–187. doi: 10.3127/ajis.v17i2.697

53