Abstract

Introduction:

University campuses in Central Europe, like elsewhere, are under increasing pressure to adopt flexible, climate-responsive, and ecological infrastructure that improves both environmental performance and student experience. In this study, we introduce a hexagonal modular unit (HEXA unit) designed to revitalize underused campus spaces through green infrastructure.

Methods:

We combined a survey of 190 campus users, statistical tests for reliability and associations, and a Life Cycle Assessment.

Results:

The survey revealed that students strongly prefer natural materials like wood and vegetation and favor multifunctional module configurations that enhance social interaction and collaborative learning. Reliability (Cronbach's Alpha) supported consistency in our attitudinal measures; Chi-square tests revealed significant differences in material preferences. Our LCA shows that HEXA units built with natural materials can reduce carbon footprint by up to ~30% compared to traditional synthetic designs.

Discussion:

Beyond environmental gains, the findings suggest that modular design choices can also enhance student engagement and support more resilient campus ecosystems. Overall, HEXA represents a scalable model for green infrastructure that can be adapted by universities and potentially extended to other urban contexts in support of sustainability goals.

1 Introduction

Urbanization and climate change increasingly pressure universities to provide outdoor environments that are sustainable, adaptable, and supportive of student well-being. Green infrastructure is widely recognized for improving microclimate, biodiversity, and user comfort (Zhu et al., 2020; Gholami et al., 2020; Ridhosari and Rahman, 2020) including cooling effects, carbon storage, and improved campus sustainability performance (Berardi et al., 2014; Bowler et al., 2010; Guest et al., 2013; Bakar et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2025). Yet most interventions remain large-scale or permanent, while small, modular, and rapidly deployable systems for revitalizing underused campus spaces remain significantly underexplored. This gap is especially relevant in Central European campuses, which function as compact urban ecosystems and are expected to act as testbeds for sustainability innovation (Min-Allah and Alrashed, 2020; Valks et al., 2020; AbuAlnaaj et al., 2020).

Recent studies demonstrate the potential of modular approaches for resilience and rapid adaptation in institutional settings (Jia et al., 2025). However, research on modular systems predominantly focuses on technical and environmental performance, with limited integration of user acceptance, spatial experience, and material preference—factors shown to strongly influence actual use of outdoor environments (Tourinho et al., 2021; Peker and Ataöv, 2020; Alnusairat et al., 2022; Abdulrazzaq et al., 2024). At the same time, universities are aligning infrastructure development with global sustainability frameworks such as SDG 11 and SDG 13 and assessment tools like UI GreenMetric (UI GreenMetric World University Rankings, 2024; Suwartha and Sari, 2013). This increases the demand for design strategies that combine ecological performance with evidence-based user-centered planning.

To address this gap, we introduce a hexagonal modular unit—HEXA unit designed to revitalize underused campus spaces through flexible spatial configurations and nature-based materials. The concept draws on the efficiency of hexagonal geometry and the growing evidence that biophilic elements enhance perceived quality, comfort, and willingness to use outdoor spaces (Tiyarattanachai and Hollmann, 2016; Zhu et al., 2020). Using a mixed-methods approach—concept development, a structured user-preference survey with statistical validation, and a comparative cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—we evaluate both social acceptance and embodied environmental performance of the system. This triangulation across prototype validation, survey-based evidence, and environmental assessment provides a robust analytical foundation.

We formulate two hypotheses:

-

(H1) spatial configuration of HEXA unit modules significantly influences user preference;

-

(H2) natural materials are preferred over synthetic alternatives.

By linking user perceptions with LCA outcomes, this study provides a transferable model for modular green infrastructure aligned with contemporary campus sustainability strategies. The findings contribute to current discussions on adaptive outdoor learning environments, decarbonisation of small-scale infrastructure, and innovative campus design within global sustainability frameworks.

2 Materials and methods

We applied a mixed-methods research design integrating three complementary components: (i) concept development supported by a full-scale prototype, constructed to verify spatial dimensions, ergonomic feasibility, and material arrangement, without conducting user testing at this stage; (ii) a structured user-preference survey with statistical validation (Cronbach's alpha for internal consistency and Chi-square tests for associations) to examine how spatial configuration and material choices influence acceptance; and (iii) a comparative Life Cycle Assessment performed according to ISO 14040/44 and EN 15804 to quantify the embodied impacts of natural (NAT) vs. synthetic (SYN) design variants. This triangulated approach combines physical concept verification, empirical survey evidence, and environmental modeling, enabling a robust assessment of both social and environmental performance.

2.1 Design concept of the HEXA modular unit

The concept of developing and adopting the modular unit employs the design thinking methodology, which emphasizes design analysis and, at a higher level, design verification through the creation of a tangible prototype. The HEXA unit was conceived as a sustainable and adaptable infrastructure element inspired by the efficiency of hexagonal geometry in natural systems such as honeycombs. Its hexagonal base (side length 1,250 mm; diameter 2,500 mm; height 2,500 mm) ensures efficient use of space, allows modular expansion, and complies with standard transport dimensions.

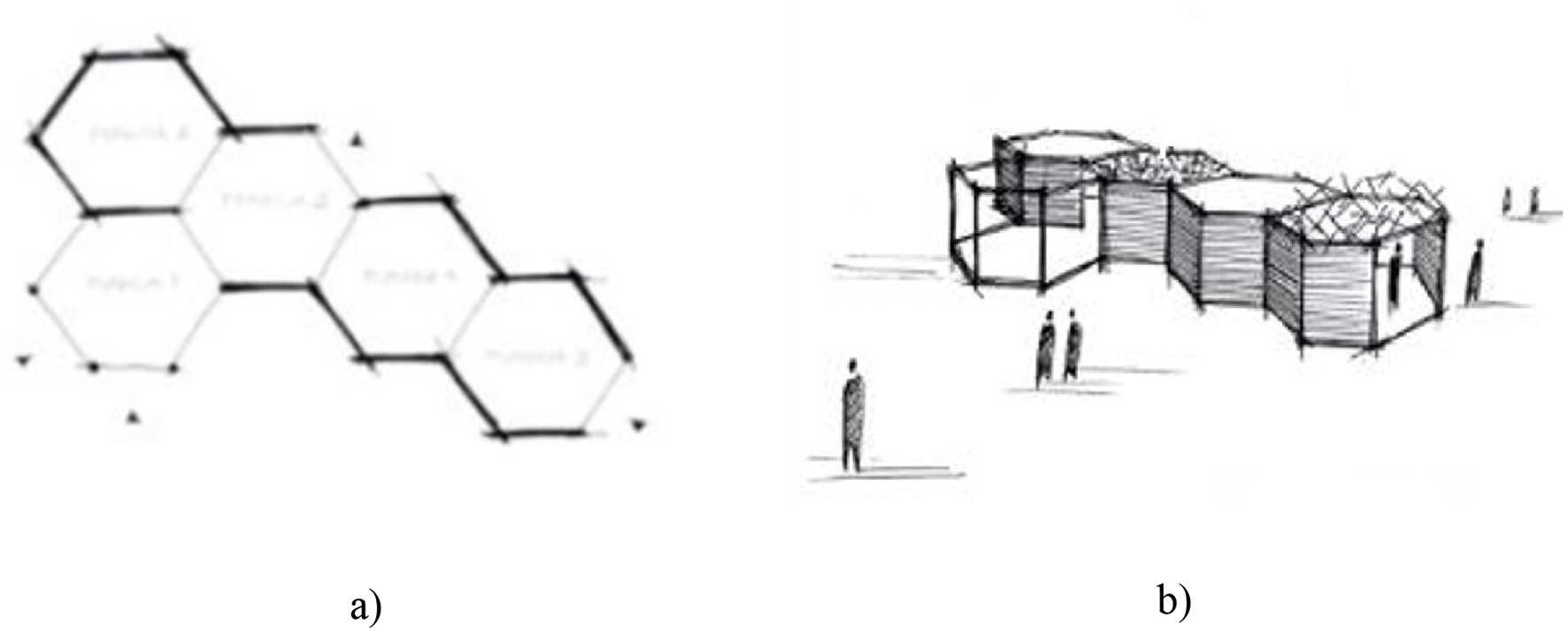

Structural frames can be constructed from wood, steel, or composites, while wall, roof, and floor panels integrate renewable materials such as vegetation panels, moss, or wood. This design enables flexible adaptation of the unit for different functions and locations, ranging from single modules to multi-unit clusters for relaxation zones, learning spaces, or transport nodes. The conceptual design of the HEXA unit is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Initial design concept of the HEXA unit: (a) floor plan design concept of the unit, (b) perspective design concept of the unit (source Authors).

Circularity was embedded into the design, with panels and structural components intended for disassembly, replacement, reuse, and recycling. Additional elements such as green roofs and moss panels enhance ecological performance by mitigating the urban heat island effect, promoting biodiversity, and improving air quality (Tourinho et al., 2021).

2.2 Prototype development

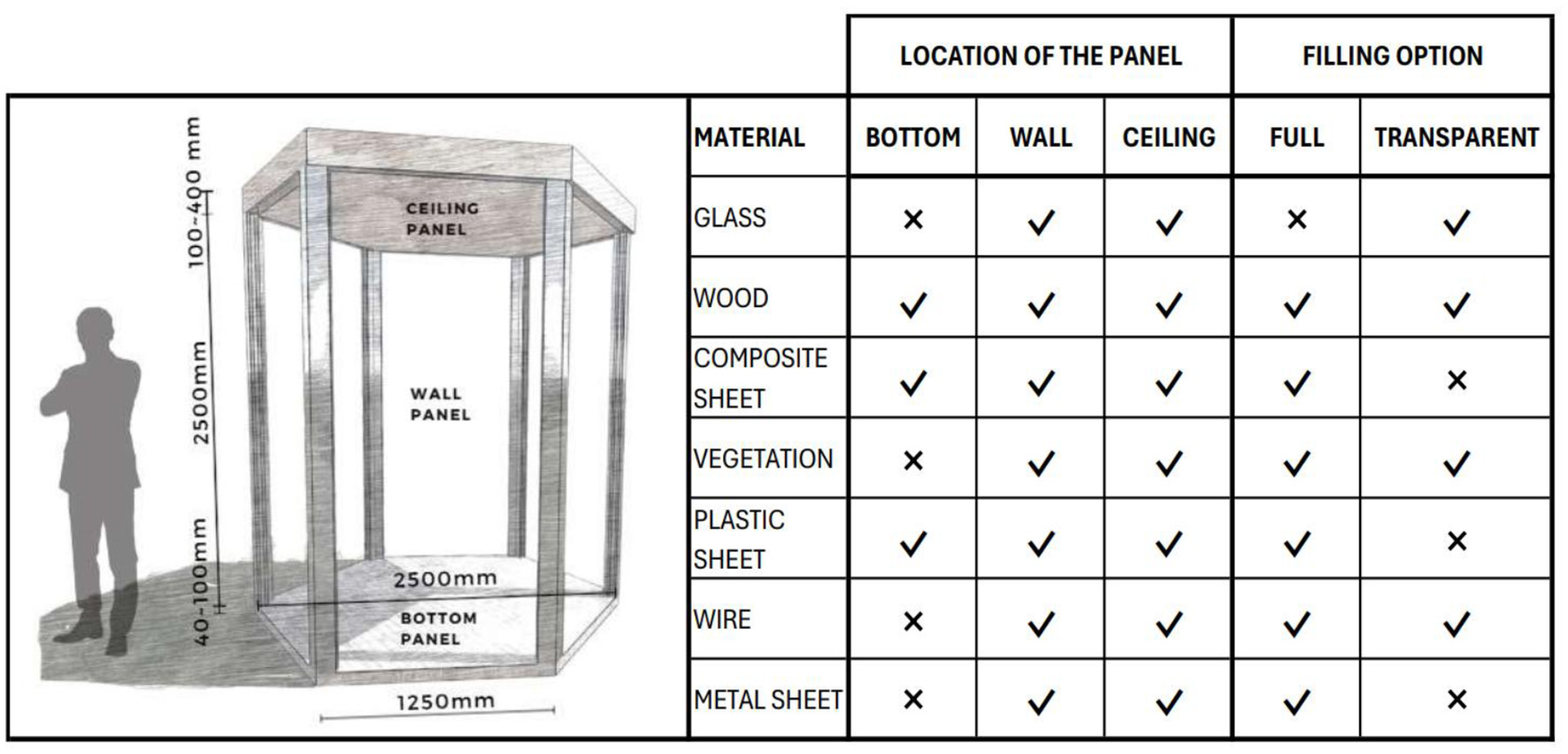

The design thinking methodology (Buhl et al., 2019) emphasizes iterative prototyping to test feasibility and stakeholder acceptance. To validate the HEXA design, a 1:1 scale prototype was constructed from wire mesh panels assembled into a hexagonal form, leaving one side open to simulate entry. A physical prototype was developed to validate the design (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Material potential of the hexagonal modular unit (source Authors).

This prototyping phase enabled spatial testing of dimensions, basic ergonomic feasibility assessment, and visual communication of the concept. Prototyping is recognized as a key tool in design thinking, supporting iterative improvement and effective stakeholder engagement (Camburn et al., 2017). Although the prototype validated spatial dimensions and assembly feasibility, no structured ergonomic or usability testing was performed at this stage. The prototype served exclusively as a concept-validation tool rather than an operational mock-up. A Stage-2 evaluation involving systematic user movement mapping, reach and posture envelopes, seating ergonomics, accessibility metrics, and thermal comfort observations is planned once the HEXA units are deployed in real campus conditions. Figures 1–3 illustrate the conceptual design, material alternatives, and prototype assembly.

Figure 3

Realization of the prototype of the HEXA unit from the wire mesh: (a) preparation of the wall panel, (b) folding the panels into a module, (c) final module (source Authors).

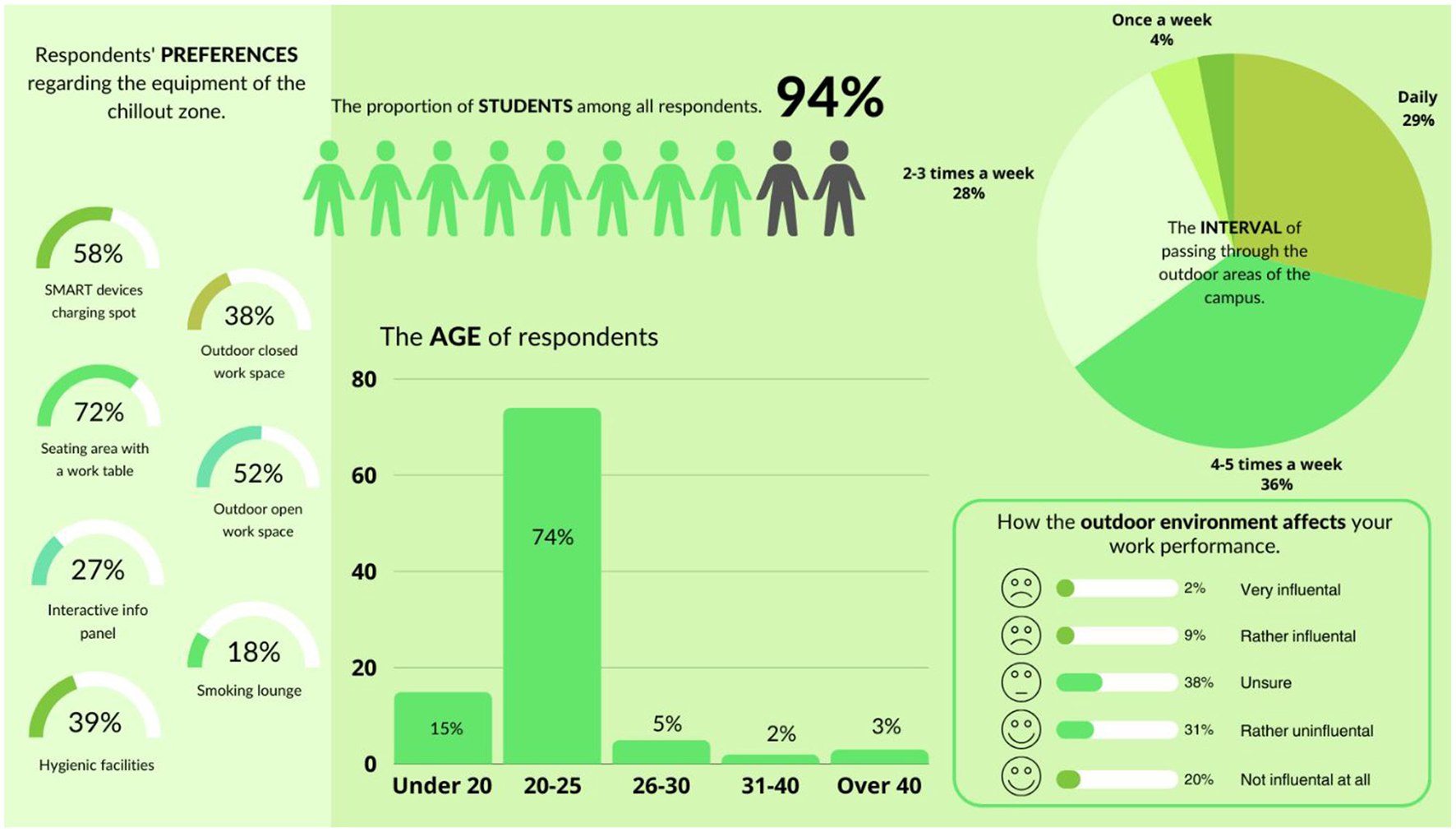

2.3 Survey methodology

The questionnaire was designed in line with recommended practices for survey-based research (Dillman et al., 2014; Fowler, 2014). It was structured into two main sections: (i) respondents' profiles (age, relation to TUKE, and frequency of campus use) and (ii) preferences regarding the design and material configuration of modular hexagonal chill-out zones. Multiple-response questions were analyzed using categorical aggregation following standard procedures for multi-select surveys (cf. Dillman et al., 2014; Presser et al., 2004). The items included categorical variables, multiple-choice options, and Likert-scale ratings on a five-point scale ranging from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied”. Figure 4 provides an overview of the questionnaire.

Figure 4

Overview of questionnaire structure.

A pilot test with 10 participants was conducted to check clarity and internal consistency before the full survey rollout (Presser et al., 2004). The final questionnaire was administered online in spring 2024 via the Click4Survey platform. Distribution channels included official university mailing lists, student social media groups, and notice boards across the TUKE campus. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with no incentives provided.

In total, 209 responses were collected. After screening and removal of incomplete or inconsistent entries, 190 valid responses remained, resulting in a 91% rate of usable data. This sample size provided sufficient statistical power for descriptive analysis and chi-square testing (Cochran, 1977).

Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale, a widely used tool to capture subjective attitudes and satisfaction in sustainability research (Tourinho et al., 2021; Alnusairat et al., 2022).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Internal consistency of the survey instrument was tested using Cronbach's Alpha (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011):

where N is the number of items, the average covariance between item pairs, and the average variance.

Preferences for materials and configurations were further tested using Chi-square goodness-of-fit (George and Mallery, 2019):

where O is the observed frequency and E the expected frequency under the null hypothesis. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

2.5 Life cycle assessment

The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was performed in accordance with ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 (ISO, 2006a,b), using thermal comfort and energy assumptions aligned with ISO 7730 (ISO, 2005) and ISO 52016-1 (ISO, 2017).

-

Goal and scope definition

-

Life cycle inventory (LCI) analysis

-

Life cycle impact assessment (LCIA)

-

Life cycle interpretation

This methodological structure is consistent with LCA practice for construction products and modular building systems (e.g., EN 15804:2012+A2:2019/AC:2021; Shah et al., 2024; Pons Fiorentin et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2011; Thirunavukkarasu et al., 2021).

2.5.1 Goal and scope of study

The goal of this LCA is to quantify the Global Warming Potential (GWP, expressed as CO2e) of Hexagonal Modular Units and to compare two design variants: NAT (timber-based) and SYN (steel–PP based). The analysis reports four indicators required by the Environmental Footprint 3.1 method: GWP-total, GWP-fossil, GWP-biogenic, and GWP-LULUC, in line with current practice for modular and green infrastructure LCAs (Almutairi, 2024; Wang et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2025).

The declared unit is one modular unit, with a total mass of 707 kg (NAT) and 732 kg (SYN). Material composition is based on 2024 design data and is shown in Table 1, which also incorporates a 2% material loss rate reflecting typical prefabrication tolerances.

Table 1

| NAT | SYN | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Mass kg | Material | Mass kg |

| Structural timber (spruce) | 350 | Structural timber (spruce) | 350 |

| Steel screws, fasteners | 25 | Steel connectors (screws, fasteners) | 25 |

| Wooden panels | 95 | Plastic panels | 120 |

| Thermal insulation (mineral wool) | 50 | Thermal insulation (mineral wool) | 50 |

| Adhesive | 5 | Adhesive | 5 |

| Coating | 2 | Coating | 2 |

| Vegetation substrate | 180 | Vegetation substrate | 180 |

| Total | 707 | Total | 732 |

Material composition of NAT and SYN modular units.

2.5.2 System boundary

The system boundary follows a cradle-to-gate scope (modules A1–A3) with end-of-life stages (C1–C4) and the Module D benefits and loads beyond system boundary, in accordance with EN 15804:2012+A2:2019/AC:2021 and ISO 14040/44. Operational energy and water use (B-modules) were excluded, as the system is a prefabricated construction component without defined in-use performance, consistent with standard practice in modular construction LCAs (Pons Fiorentin et al., 2024; Almutairi, 2024).

Included Processes- description.

2.5.3 A1-raw material supply

Covers extraction and upstream processing of all materials, including timber, steel fasteners, mineral wool insulation, adhesive, coatings, wooden or PP panels, and vegetated substrate. Generic datasets were sourced from Ecoinvent 3.10.1 to ensure technological and geographical representativeness.

A2-Transport—includes transport of all raw materials to the manufacturing facility. A standard distance of 200 km by EURO VI lorry (16–32 t; 35 l/100 km) is applied, including emissions from fuel production and combustion

A3-Manufacturing—includes all energy and material inputs for prefabrication:

-

- 45 kWh of electricity for cutting and assembly,

-

- 20 MJ for wood drying and gluing,

-

- 2% material losses, typical for prefabricated timber–steel hybrid systems.

End-of-life Processes

C1-Deconstruction—manual disassembly of the unit is assumed, with negligible environmental impact.

C2-Transport—transport of dismantled components to waste treatment facilities over 50 km by EURO VI lorry.

C3-Waste Processing—reflects realistic European recycling and recovery rates: – 26% of wood recycled, 50% energy recovery – 85% of steel recycled – 9% of polystyrene recycled, 59% energy recovery

C4-Disposal Landfilling of remaining fractions: – 24% timber, 15% steel, 32% polystyrene.

Module D-Benefits and Loads Beyond the System Boundary

Module D includes substitution benefits from materials recovered during waste processing. Credits are calculated for avoided production of primary steel, energy recovery from wood and polystyrene, and biogenic carbon flows. The structure follows EN 15804 substitution principles and aligns with recent modular LCA studies (Jia et al., 2025; Shah et al., 2024).

The life cycle inventory (LCI) compiles all material and energy flows associated with the production and end-of-life stages of the Hexagonal Units. Inventory data were collected in 2024 and supplemented with generic datasets from Ecoinvent 3.10.1, ensuring technological, geographical, and temporal representativeness in line with ISO 14040/44. The LCI corresponds to the system boundary defined in modules A1–A3, C1–C4, and D, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Module | Product stage | Assembly stage | Use stage | End of life stage | Beyond the system boundaries | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw material supply | Transport | Manufacturing | Transport | Assembly | Use | Maintenance | Repair | Replacement | Refurbishment | Operational energyuse | Operational wateruse | De-constructiondemolition | Transport | Waste processing | Disposal | Reuse-Recovery-Recycling-potential | |

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 | B7 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | D | |

| Modules declared | X | X | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | X | X | X | X | X |

Lifecycle modules considered in the LCA according to EN 15804.

2.5.4 Life cycle inventory analysis

The life cycle inventory compiles all material and energy flows within the modules included in the system boundary (A1–A3, C1–C4, D). Inventory data for the Hexagonal Units were collected in 2024 and processed using the Ecoinvent 3.10.1 database and EF 3.1 characterization factors in One Click LCA. Only processes within the declared system boundary were included; no operational-stage data were modeled.

-

Primary data: material composition of NAT and SYN variants, manufacturing energy requirements, and transport distances provided by the design team at TUKE (2024).

-

Secondary data: Ecoinvent datasets for upstream material production, transport, energy supply, recycling, and waste treatment.

-

Data meet ISO 14040/44 criteria for temporal (< 3 years), geographical (Europe), and technological relevance.

Product Stage Inventory (A1–A3)

Raw materials (A1)—inventory includes all inputs listed in Table 1 (timber, steel fasteners, wooden or PP panels, mineral wool, adhesives, coatings, vegetated substrate). Material losses are accounted for by applying a 2% process loss factor across relevant materials.

Transport of materials (A2)—material inputs are transported to the manufacturing facility using a EURO VI lorry over a 200 km distance. Transport includes both fuel use and upstream fuel production.

Manufacturing processes (A3)—the inventory covers:

-

45 kWh of electricity for cutting, machining, and assembly,

-

20 MJ of thermal energy for wood drying and adhesive curing,

-

auxiliary processes (fastener installation, coating application). Electricity and heat datasets reflect the European energy mix.

End-of-Life Inventory (C1–C4)

Deconstruction (C1)—manual disassembly without machinery or fuel inputs.

Transport to waste treatment (C2)—a uniform distance of 50 km is applied for all outgoing material streams.

Waste processing (C3)—treatment routes follow rates provided in the technical documentation:

-

Wood: 26% recycling, 50% energy recovery

-

Steel: 85% recycling

-

Polystyrene: 9% recycling, 59% energy recovery Datasets include material sorting, shredding, and preparation for recycling.

Disposal (C4)—residual fractions not recovered in C3 are landfilled (24% wood, 15% steel, 32% polystyrene), modeled using standard European landfill datasets.

Module D quantifies avoided burdens from recycling and energy recovery. Credits include:

-

substitution of primary steel through recovered steel,

-

substitution of heat production through energy recovery from wood and polystyrene,

-

biogenic carbon flows from timber following EF 3.1 rules.

Module D results are reported separately, as required by EN 15804.

2.5.5 Uncertainty and data quality assessment

A pedigree-based qualitative assessment was applied to evaluate uncertainty in the LCI datasets, following the Ecoinvent and ILCD/EF 3.1 framework. Each dataset was assessed across technological, geographical, and temporal representativeness, completeness, and reliability. Most background datasets (timber, steel, insulation, PP, transport) showed high representativeness (scores 1–2), while manufacturing energy data showed medium temporal completeness (score 3) due to annual variability. Overall, the uncertainty levels do not affect the comparative direction of the results, as the NAT–SYN difference remains larger than the variability introduced by data quality factors.

3 Results

3.1 Validation of hypotheses

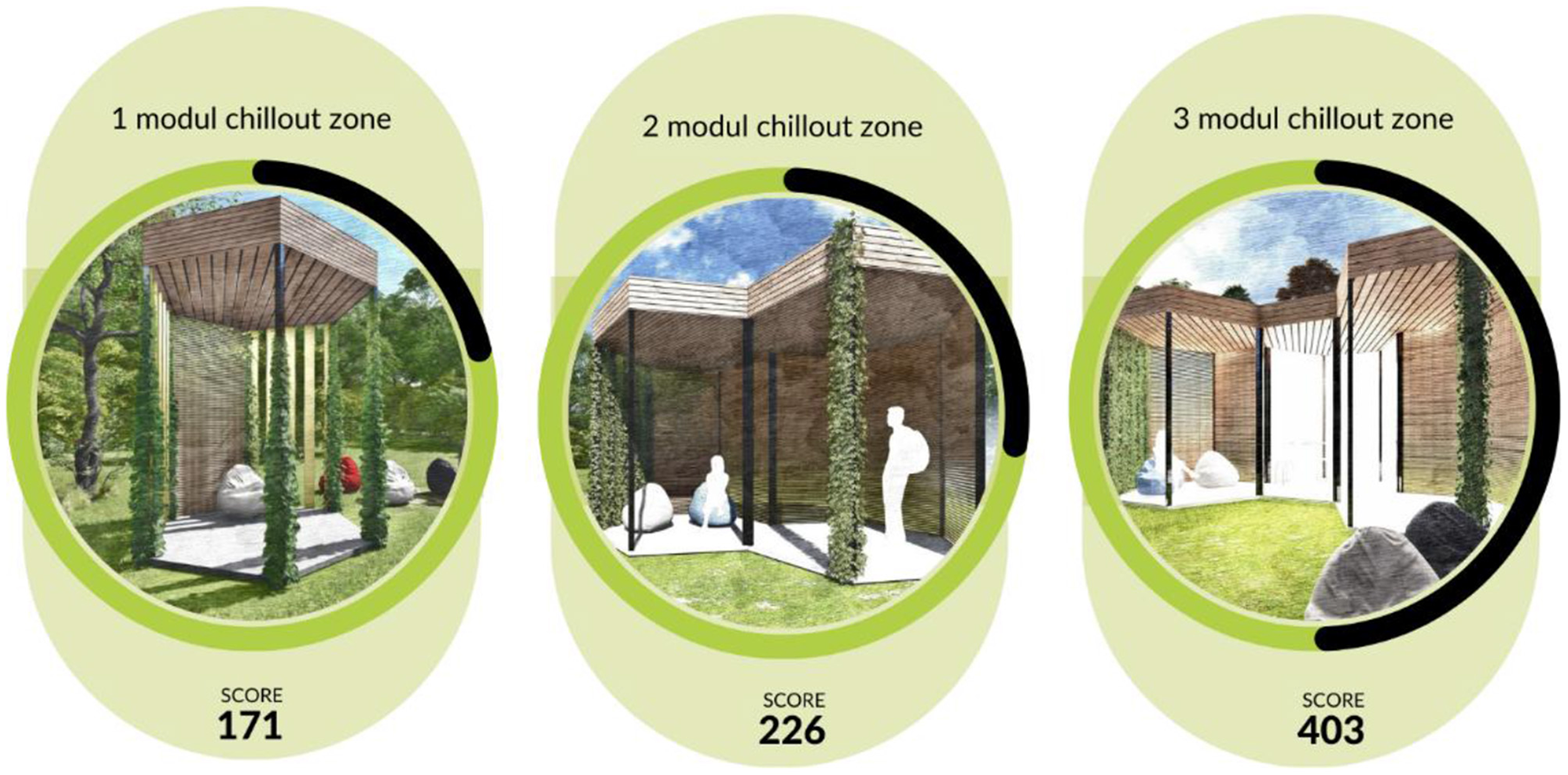

We evaluated whether spatial configuration (H1) and material choice (H2) influence user acceptance of the HEXA unit. For H1, the distribution of first-rank choices across the three configurations (single, double, triple) was highly uneven (31, 43, 116 of 190, respectively), yielding χ2(2) = 66.83, p < 0.0001. For H2, votes across nine material options were likewise far from uniform (wood-based and vegetated options dominating), with χ2(8) = 409.61, p < 0.0001. These results confirm that both module configuration and materials substantially shape user acceptance (Table 3; cf. Figure 5 for configuration first choices and for material votes). This pattern aligns with the broader campus literature in which design attributes condition uptake of sustainability interventions (Tiyarattanachai and Hollmann, 2016; Zhu et al., 2020).

Table 3

| Hypothesis | Description* | χ2 | df | p-value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Spatial configuration (single/double/triple) influences preference (based on first-rank counts) | 66.83 | 2 | < 0.0001 | Supported |

| H2 | Material choice (9 options; multi-select vote counts) influences acceptance | 409.61 | 8 | < 0.0001 | Supported |

Validation of H1 and H2 using Chi-square tests (goodness-of-fit against equal preference).

*Counts used for tests. H1: 31 (single), 43 (double), 116 (triple); H2 (total votes = 677): 150 (wood panels), 143 (wood frame), 130 (moss), 120 (vegetation panels), 82 (glass), 21 (plaster), 11 (wire mesh), 11 (plastic wall panel), 9 (metal sheet).

Figure 5

Preferences of the volume configuration of the chillout zone in the premises of the university campus (source Authors).

3.2 Reliability analysis

Internal consistency was assessed only for the multi-item block related to design preferences (six Likert-scale items addressing satisfaction with spatial configuration, material use, comfort, aesthetic appeal, perceived functionality, and overall suitability). This block reached Cronbach's alpha of 0.76, indicating acceptable reliability for exploratory analysis (Table 4). Other parts of the questionnaire (e.g., sustainability impact) consisted of single items and were therefore excluded from the reliability analysis, as Cronbach's alpha is not applicable in such cases. Overall, the instrument demonstrated sufficient reliability for descriptive contrasts and chi-square testing (Tavakol and Dennick, 2011; George and Mallery, 2019), which is consistent with guidance on interpreting instrument reliability (Streiner, 2003).

Table 4

| Construct | Items | Scale | α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design preferences | 6 | Likert (1–5) | 0.76 |

| Sustainability impact | 1 | Likert (1–5) | — |

Internal consistency (Cronbach's Alpha) for survey constructs.

Interpretation follows common practice for exploratory studies; see Methods 2.4.

3.3 Preferences for configurations

Students clearly favored interconnected clusters over a single standalone unit (see Table 5). Based on first-rank choices, the triple-module configuration dominated (116/190, 61.1%), followed by double-module (43/190, 22.6%) and single-module (31/190, 16.3%; Figure 5). This uneven distribution underpins the significant Chi-square result reported in Table 3 (Section 3.1), confirming that spatial arrangement is a salient driver of acceptance. The ordering was mirrored by the study's weighted ranking (triple > double > single), indicating consistency across summary metrics.

Table 5

| Configuration | First-rank count | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Single standalone module | 31 | 16.3 |

| Double-module cluster | 43 | 22.6 |

| Triple-module cluster | 116 | 61.1 |

First-rank preferences for HEXA unit configurations (n = 190).

First-rank counts were used for the goodness-of-fit test of H1 (see Table 3).

3.4 Preferences for materials

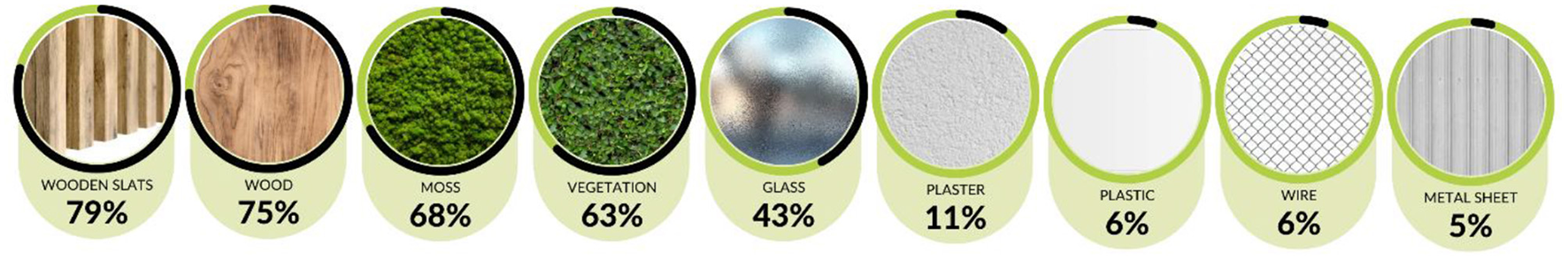

Material choices were strongly skewed toward nature-based options. Out of nine alternatives, respondents most frequently selected wood panels (150/190; 78.9%), wood for the frame (143/190; 75.3%), moss panels (130/190; 68.4%), and vegetation panels (120/190; 63.2%). By contrast, synthetic finishes received markedly fewer selections—plaster (11.1%), wire mesh (5.8%), plastic wall panel (5.8%), and metal sheet (4.7%)—with glass (43.2%) sitting mid-range as a transparent cladding alternative. The goodness-of-fit test against equal preference confirmed a large deviation (χ2(8) = 409.61, p < 0.0001; see Table 2), i.e., natural materials overwhelmingly dominated, supporting H2. The distribution visualized in Figure 6 underpins the Chi-square result in Table 3 (Section 3.1).

Figure 6

Preferences in relation to the material design of the construction of the modular unit (source Authors).

3.5 LCA findings

The impact assessment was carried out using One Click LCA. All background data were taken from Ecoinvent 3.10.1, and characterization factors were applied according to the Environmental Footprint 3.1 (EF 3.1) method. The assessment follows the EN 15804-compliant impact categories provided by the EF 3.1 characterization framework (European Commission, JRC).

The calculated impact values represent relative environmental performance and do not indicate absolute risk levels, threshold exceedances, or endpoint damage. Results for the Global Warming Potential (GWP) indicators are reported per lifecycle module, as totals, and normalized per kilogram of the declared unit. These results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6

| Module | NAT | SYN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWP-total kg CO 2 e | GWP-fossil kg CO 2 e | GWP-biogenic kg CO 2 e | GWP-LULUC kg CO 2 e | GWP-total kg CO 2 e | GWP-fossil kg CO 2 e | GWP-biogenic kg CO 2 e | GWP-LULUC kg CO 2 e | |

| A1 | −622.90 | 127.88 | −753.86 | 3.0800 | −52.74 | 537.43 | −591.51 | 1.3400 |

| A2 | 27.32 | 27.32 | 0.00 | 0.0097 | 28.35 | 28.34 | 0.00 | 0.0102 |

| A3 | 775.37 | 21.50 | 753.86 | 0.0034 | 613.01 | 21.5 | 591.51 | 0.0034 |

| A1–A3 | 179.79 | 176.69 | 0.00 | 3.0900 | 588.62 | 587.27 | 0.00 | 1.3536 |

| C1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.0000 |

| C2 | 4.71 | 4.70 | 0.00 | 0.0019 | 5.05 | 5.05 | 0.00 | 0.0020 |

| C3 | 99.33 | 99.32 | 0.00 | 0.0046 | 325.44 | 325.43 | 0.00 | 0.0056 |

| C4 | 4.33 | 4.33 | 0.00 | 0.0015 | 8.80 | 8.80 | 0.00 | 0.0017 |

| Total | 288.16 | 285.04 | 0.00 | 3.1000 | 927.91 | 926.55 | 0.00 | 1.3629 |

| D | −192.06 | 0.00 | −192.06 | 0.0000 | −151.06 | 0.00 | −151.06 | 0.0000 |

| Total per mass of DU | 0.4076 | 0.4032 | 0.00 | 0.0044 | 1.2676 | 1.2658 | 0.00 | 0.0018 |

Results for GWP indicators (NAT and SYN variants).

3.5.1 Prospective scenarios and uncertainty analysis

To contextualize the cradle-to-gate results and assess robustness, two prospective scenarios were modeled qualitatively: (1) prospective use-phase benefits, including shading, evapotranspiration cooling, and biodiversity support; (these potential operational co-benefits fall outside the declared cradle-to-gate system boundary and were not quantified in this study. They are therefore presented only as qualitative prospective scenarios and should not be interpreted as part of the core LCA results) and (2) end-of-life pathways, including increased recycling for steel and timber and reduced landfill disposal. Although not included in the core system boundary, these scenarios indicate that operational benefits would further favor the NAT variant due to its nature-based components.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on key parameters. Increasing recycled steel content by 30% reduced SYN GWP by approximately 10%, while a ±50% variation in transport distance changed total impacts by 3–7%. Increasing energy demand for vegetated panels by 20% increased NAT GWP by 2–4%. These variations are substantially smaller than the observed NAT–SYN difference (~30%), confirming the robustness of the comparative outcome.

Uncertainty was examined using a pedigree-based qualitative assessment, which indicated medium data quality for manufacturing and high quality for material production datasets. These uncertainty levels do not affect the directional conclusions of the study.

3.5.2 Interpretation of results

The interpretation of results focuses on identifying the dominant lifecycle stages, explaining differences between the NAT and SYN variants, and evaluating the influence of key modeling assumptions.

The product stage (A1–A3) was the primary contributor to the total GWP for both variants. The NAT variant exhibited substantially lower GWP due to the high biogenic carbon content of timber, reflected in negative biogenic CO2 flows in A1. As a result, the NAT unit showed a 32% lower total GWP compared to the SYN unit, confirming the environmental advantage of bio-based materials.

End-of-life processes (C1–C4) contributed only a minor share to overall impacts. However, Module C3 was more significant for the SYN variant due to higher waste processing requirements for steel and polystyrene.

Module D provided meaningful environmental credits for both variants. The SYN unit benefited primarily from steel recycling, while the NAT unit showed additional biogenic carbon credits associated with wood recovery. These avoided burdens reduced total GWP by 40–55% depending on the variant.

The results demonstrate that material selection—particularly replacing steel and PP panels with timber-based components—has a decisive effect on embodied carbon performance. Transport assumptions and energy inputs had comparatively limited influence on overall results.

4 Discussion

4.1 Comparison with prior research

This aligns also with broader findings on social sustainability gaps in construction projects (Kordi et al., 2022). This study demonstrates that spatial configuration and material choice strongly shape user acceptance of the HEXA unit. The clear preference for clustered (triple-module) arrangements supports findings that spatial coherence and connectedness enhance social interaction and usability in urban open spaces (Tourinho et al., 2021; Peker and Ataöv, 2020; Alnusairat et al., 2022). The favorable response to natural materials likewise aligns with evidence that biophilic elements such as timber, vegetation, and moss enhance perceived quality, well-being, and willingness to use outdoor environments (Tiyarattanachai and Hollmann, 2016; Zhu et al., 2020).

To strengthen the external validity of our findings, we compared user-preference patterns with evidence from campuses located in different climatic and cultural contexts. Similar preferences for clustered layouts, shaded resting areas, and nature-based materials have been reported in subtropical environments such as Hong Kong (Jia et al., 2025), Mediterranean settings including Istanbul (Bulut, 2021), arid and semi-arid regions such as Amman (Alnusairat et al., 2022), and tropical–subtropical climates such as Brazil (Tourinho et al., 2021). These convergent results suggest that the strong appeal of biophilic materials and interconnected modular configurations is not limited to Central Europe and may be generalisable across diverse climate zones and campus typologies.

The environmental assessment reinforces these design patterns: the NAT variant—characterized by timber framing and vegetated components—exhibited substantially lower embodied carbon than the SYN variant due to biogenic carbon storage and reduced use of energy-intensive materials. This aligns with research showing that bio-based materials significantly reduce life-cycle impacts in modular and prefabricated systems (Shah et al., 2024; Pons Fiorentin et al., 2024; Jia et al., 2025). The convergence of user preference and environmental performance therefore suggests that nature-based design strategies can simultaneously support decarbonisation and improve public acceptance.

Beyond social and environmental performance, the HEXA unit shows strong relevance for campus sustainability assessment. It aligns with several UI GreenMetric indicators, including energy and climate change, water management, land use and green space, and innovative campus infrastructure. Lower embodied carbon in the NAT variant contributes to the Energy and Climate Change (EC) category, while vegetated and permeable surfaces support Water (WS) and Setting and Infrastructure (SI) indicators. These contributions can be quantified through added vegetated area, stormwater retention potential, shading performance, and modular deployment counts, positioning the HEXA unit as a practical tool for improving campus sustainability metrics. These potential operational co-benefits fall outside the current cradle-to-gate boundary and will be quantified in future work.

Finally, the study advances methodological practice by integrating user-preference analysis with a comparative LCA, scenario-based sensitivity testing, and data-quality assessment. This combined approach illustrates how early-stage modular concepts can be evaluated rigorously before large-scale deployment, offering a transferable framework for future hybrid social–environmental assessment of nature-based modular systems.

4.2 Implications for sustainable infrastructure

Our findings suggest several implications for design and planning practice.

-

Clustering matters: modular systems deployed in interconnected groups are more likely to attract use and deliver perceived value than isolated units, supporting resilience and adaptability in dense urban settings.

-

Material choices matter: nature-based envelopes not only improve social acceptance but also reduce embodied carbon; where synthetic materials are unavoidable, specifying recycled content can mitigate impacts.

-

Regionalized supply chains: transport effects are modest within 50–150 km but grow with system mass; local prefabrication and logistics planning are therefore essential for scalable adoption.

-

Circularity by design: designing modules for disassembly and reuse ensures long-term adaptability and aligns with circular-economy objectives for urban infrastructure.

-

Monitoring in operation: embedding sensors and observational studies in real deployments can generate evidence on thermal comfort, biodiversity, and usage, transforming modular systems into living laboratories for sustainable innovation.

4.3 Limitations and future directions

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The survey was based on a single case study context and showed moderate internal consistency across multi-item scales—acceptable for an exploratory design, yet indicating the need for more robust measurement instruments and longitudinal validation in future research. The prototype was validated visually and dimensionally, but not through systematic ergonomic testing. Future work will include structured user-interaction metrics. The LCA component was restricted to cradle-to-gate boundaries, which excludes potential operational benefits such as shading, cooling, or evapotranspiration, as well as full end-of-life scenarios. Future studies should therefore adopt cradle-to-grave system boundaries and apply life-cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) to capture environmental, social, and economic performance in an integrated framework. Finally, the results reflect a specific cultural and spatial setting; broader validation across diverse geographies, climatic conditions, and governance systems—ideally through coordinated multi-site pilots—will be essential for generalizing the findings.

5 Conclusions

This study introduced and evaluated a modular HEXA unit as a scalable model for sustainable urban infrastructure. By integrating user perception data with a comparative LCA, it demonstrated that spatial configuration and material selection exert significant influence on both social acceptance and embodied environmental impacts. The findings highlight the potential of clustered, nature-based modular systems to enhance usability while lowering carbon footprints, supporting more adaptive and resource-efficient urban environments.

Although grounded in a single campus prototype, the results point to broader implications for sustainable infrastructure design: the need to incorporate user perspectives into early-stage decisions, the effectiveness of bio-based materials in reducing embodied carbon, and the importance of designing for circularity and regionally sourced supply chains. Future research should extend toward full life-cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA), conduct longitudinal user studies, and test modular systems across diverse geographic and climatic contexts. Advancing these pathways can help modular green units progress from experimental prototypes to practical, low-carbon solutions that support resilient and inclusive cities.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MKoz: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation. IH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SV: Data curation, Fromal analysis, Validation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZV: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MKoc: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We kindly thank to project VEGA 1/0336/22 Research on the effects of Lean Production/Lean Construction methods on increasing the efficiency of on-site and off-site construction technologies, APVV-22-0576 Research of digital technologies and building information modeling tools for designing and evaluating the sustainability parameters of building structures in the context of decarbonization and circular construction and KEGA project num. 054TUKE-4/2024.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Artificial intelligence tools (specifically ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI) were used exclusively to assist with English grammar correction and language editing. The author(s) take full responsibility for the scientific content, interpretation, and conclusions of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1706667/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdulrazzaq Z. M. Al-Abdaly H. M. Ahmad M. D. (2024). Sustainable outdoor spaces and their achievement mechanisms at the university campus (case study – University of Anbar). AIP Conf. Proc.2885:050010. doi: 10.1063/5.0181570

2

AbuAlnaaj K. Ahmed V. Saboor S. (2020). “A strategic framework for smart campus,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 790–798.

3

Almutairi M. (2024). Sustainability assessment of modern methods of construction: opportunities and challenges. Front. Sustain. Cities6:1439024. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1439024

4

Alnusairat S. Al-Shatnawi Z. Ayyad Y. Alwaked A. Abuanzeh N. (2022). Rethinking outdoor courtyard spaces on university campuses to enhance health and wellbeing: the anti-virus built environment. Sustainability14:5602. doi: 10.3390/su14095602

5

Bakar M. N. A. Salleh H. M. Rahim N. M. Ne'Matullah K. F. Idris Z. (2021). Sustainable campus: an integrated student knowledge, waste (WS), energy and climate change (EC) for recognition in UI-Green Metric World College Ranking. Selangor Human. Rev.5, 93–101. https://share.journals.unisel.edu.my/index.php/share/article/view/175 (Accessed June 16, 2024).

6

Berardi U. GhaffarianHoseini A. GhaffarianHoseini A. (2014). State-of-the-art analysis of the environmental benefits of green roofs. Appl. Energy115, 411–428. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.10.047

7

Bowler D. E. Buyung-Ali L. Knight T. M. Pullin A. S. (2010). Urban greening to cool towns and cities: a systematic review of the empirical evidence. Landsc. Urban Plan.97, 147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.05.006

8

Buhl A. Schmidt-Keilich M. Muster V. Blazejewski S. Schrader U. Harrach C. et al . (2019). Design thinking for sustainability: why and how design thinking can foster sustainability-oriented innovation development. J. Clean. Prod.231, 1248–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.259

9

Bulut M. (2021). Building a sustainable university campus in Turkey: the case of Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University. J. Sustain. Perspect.1, 263–269. doi: 10.14710/jsp.2021.12013

10

Camburn B. Viswanathan V. Linsey J. Anderson D. Jensen D. Crawford R. et al . (2017). Design prototyping methods: state of the art in strategies, techniques, and guidelines. Des. Sci.3:13. doi: 10.1017/dsj.2017.10

11

Cochran W. G. (1977). Sampling Techniques, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN: 978-0-471-16240-7.

12

Dillman D. A. Smyth J. D. Christian L. M. (2014). Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method.Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN: 978-1-118-45614-9. doi: 10.1002/9781394260645

13

Fowler F. J. (2014). Survey Research Methods, 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. ISBN: 978-1-4522-5784-7.

14

George D. Mallery P. (2019). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. London: Routledge.

15

Gholami H. Bachok M. F. Saman M. Z. M. Streimikiene D. Sharif S. Zakuan N. (2020). An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing green campus operations: towards higher education sustainability. Sustainability12:363. doi: 10.3390/su12010363

16

Guest G. Cherubini F. Strømman A. (2013). Global warming potential of carbon dioxide emissions from bioenergy fuels. Clim. Change121, 763–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00507.x

17

ISO (2005). ISO 7730: Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment – Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

18

ISO (2006a). ISO 14040: Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment – Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

19

ISO (2006b). ISO 14044: Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment – Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

20

ISO (2017). ISO 52016-1: Energy Performance of Buildings – Calculation of Indoor Temperatures and Heating and Cooling Loads – Part 1. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

21

Jia A. Y. Zhang Y. Shen J. (2025). Modular integrated construction as a development strategy for post-COVID urban sustainability: the case of Hong Kong. Front. Sustain. Cities7:1553276. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1553276

22

Kordi N. E. Belayutham S. Ibrahim C. K. I. C. (2022). Social sustainability in construction projects: perception versus reality and the gap-filling strategies. Front. Built Environ.8:1053144. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2022.1053144

23

Kumar P. Sahani J. Cao S. J. Nascimento E. G. S. Perez K. C. Ahlawat A. et al . (2025). Urban greening for climate resilient and sustainable cities. Front. Sustain. Cities4:1595280. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1595280

24

Min-Allah N. Alrashed S. (2020). Smart campus—a sketch. Sustainable Cities and Society59, 102231. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102231

25

Peker E. Ataöv A. (2020). Exploring the ways in which campus open space design influences students' learning experiences. Landsc. Res.45, 310–326. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2019.1622661

26

Pons Fiorentin D. Martín-Gamboa M. Rafael S. Quinteiro P. (2024). Life cycle assessment of green roofs: a comprehensive review of methodological approaches and climate change impacts. Sustain. Prod. Consumption45, 598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2024.02.004

27

Presser S. Couper M. P. Lessler J. T. Martin E. Martin J. Rothgeb J. M. et al . (2004). Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opin. Q.68, 109–130. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfh008

28

Ridhosari B. Rahman A. (2020). Carbon footprint assessment at Universitas Pertamina: toward a green campus and promotion of environmental sustainability. J. Clean. Prod.246:119172. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119172

29

Shah A. M. Liu G. Nawab A. Li H. Xu D. Yeboah F. K. et al . (2024). Sustainability and resilience interface at typical urban green and blue infrastructures: costs, benefits, and impacts assessment. Front. Sustain. Cities6:1453829. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2024.1453829

30

Sharma A. Saxena A. Sethi M. Shree V. Varun. (2011). Life cycle assessment of buildings: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.15, 871–875. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2010.09.008

31

Streiner D. (2003). Being inconsistent about consistency: when coefficient alpha does and doesn't matter. J. Pers. Assess.80, 217–222. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8003_01

32

Suwartha N. Sari R. F. (2013). Evaluating UI GreenMetric as a tool to support green universities development: assessment of the year 2011 ranking. J. Clean. Prod.61, 46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.02.034

33

Tavakol M. Dennick R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ.2, 53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

34

Thirunavukkarasu K. Kanthasamy E. Gatheeshgar P. Poologanathan K. Rajanayagam H. Suntharalingam T. et al . (2021). Sustainable performance of a modular building system made of built-up cold-formed steel beams. Buildings11:460. doi: 10.3390/buildings11100460

35

Tiyarattanachai R. Hollmann N. M. (2016). Green campus initiative and its impacts on quality of life of stakeholders in Green and Non-Green Campus universities. SpringerPlus5:84. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1697-4

36

Tourinho A. C. C. Barbosa S, A. Göçer Ö. Alberto K, C. (2021). Post-occupancy evaluation of outdoor spaces on the campus of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brazil. Archnet-IJAR: Int. J. Archit. Res. 15, 617–633. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-09-2020-0204

37

UI GreenMetric World University Rankings (2024). About UI GreenMetric. Available online at: https://greenmetric.ui.ac.id/about/welcome (Accessed June 16, 2024).

38

Valks B. Arkesteijn M. H. Koutamanis A. den Heijer A. C. (2020). Towards a smart campus: supporting campus decisions with internet of things applications. Build. Res. Inf.49, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2020.1784702

39

Wang H. Zhang Y. Gao W. Kuroki S. (2020). Life cycle environmental and cost performance of prefabricated buildings. Sustainability12:2609. doi: 10.3390/su12072609

40

Zhu B. Zhu C. Dewancker B. (2020). A study of development mode in green campus to realize the sustainable development goals. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ.21, 799–818, doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-01-2020-0021

Summary

Keywords

biophilic materials, campus urban design, hexagonal design units, life cycle assessment, modular green infrastructure, sustainable cities, user preferences

Citation

Kozlovska M, Halaszova I, Kaposztasova D, Vilcekova S, Vranayova Z and Kocúrkova M (2026) Scalable hexagonal modular units for green and adaptive infrastructure. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1706667. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1706667

Received

16 September 2025

Revised

27 November 2025

Accepted

30 November 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Roberto Alonso González-Lezcano, CEU San Pablo University, Spain

Reviewed by

Sofia Melero-Tur, CEU San Pablo University, Spain

Mohammed Alnaim, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kozlovska, Halaszova, Kaposztasova, Vilcekova, Vranayova and Kocúrkova.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Kaposztasova, daniela.kaposztasova@tuke.sk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.