Abstract

Bridging the gap between academic research and practical implementation remains a major challenge in the transition toward sustainable urban mobility—especially in rapidly growing cities of the Global South. This paper examines the applicability of the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development (FSSD) and its ABCD planning process in supporting real-world action in four East African cities: Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam and Kisumu. Drawing on participatory co-creation workshops, stakeholder interviews, and city-level strategy development, the analysis explores how systemic thinking and strategic dialogue can help identify critical gaps in governance, infrastructure, and institutional trust. The findings reveal that while many mobility strategies are visionary, they often lack integrated implementation pathways. However, elements of the ABCD approach were evident in practice, demonstrating how structured, participatory methods can build consensus, align actions with sustainability principles, and enhance local ownership. The study suggests that more systematic integration of the FSSD framework in implementation-oriented projects could further bridge the research–practice divide. This paper contributes to the literature on method application and research-practice translation, offering lessons for urban planners, policymakers, and researchers seeking to navigate the complexity of sustainable mobility transitions in developing contexts.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, sustainable mobility has emerged as a central priority in global urban development agendas (Russo, 2022) driven by the imperatives of climate change mitigation, social inclusion, and the need to support growing urban populations (Allam and Sharifi, 2022). Numerous international frameworks—including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Agreement, and the New Urban Agenda—have underscored the importance of building low-carbon, inclusive, and resilient transport systems (Penagos, 2021; ESCAP UN, 2024; Mohammadpourlima et al., 2024; Shadiya, 2024). However, despite an expanding body of academic knowledge and the proliferation of pilot projects and technical solutions, cities (particularly in the Global South) continue to struggle with the practical implementation of sustainable mobility strategies (Heinrichs et al., 2018; Venter et al., 2019; Zegras et al., 2020; Angarita-Lozano et al., 2025). The disjunction between knowledge generation and action is what many scholars refer to as the implementation gap (Bardosh et al., 2017; Westerlund et al., 2019; Alazmi and Alazmi, 2023; Arteaga et al., 2024).

This gap is not merely a result of poor policy design or technical shortcomings. Rather, it reflects deeper structural issues, including fragmented governance systems, weak institutional coordination, limited stakeholder engagement, and an absence of strategic frameworks that can translate vision into practice (Cejudo and Michel, 2017; Pelletier et al., 2018; Biermann et al., 2020; Nilsen and Sandaunet, 2021; Arteaga et al., 2024). Even as concepts such as Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning (SUMP), Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), and transport electrification gain prominence, many cities find themselves unable to integrate these approaches into existing systems in a coherent and context-sensitive way (Filho et al., 2021; Gall et al., 2023; Borchers et al., 2024; Comi et al., 2024).

In East Africa, cities such as Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu illustrate this paradox. They are simultaneously sites of bold experimentation and persistent challenges, including traffic congestion, infrastructure deficits, air pollution, and inequitable access to mobility (Galuszka, 2021; Myers, 2022; Goodfellow, 2022; Kombe and Muheirwe, 2024). These cities have received considerable support from development partners, research institutions, and donors to design and implement sustainable transport solutions. Yet practical uptake remains limited. Often, well-designed research outputs and policy recommendations remain disconnected from city-level decision-making—especially when competing mandates, political cycles, or informal transport systems are not fully accounted for (Cirolia, 2019; Galuszka, 2021; Joseph et al., 2021; Nyamai, 2020). The result is a pattern of visionary documents and demonstration pilots that fail to generate systemic transformation (Barwick et al., 2009; Abdi and Lamíquiz-Daudén, 2022; Araújo and Smith, 2025).

This paper suggests that addressing this implementation gap requires strategic frameworks that support cities in navigating complexity, aligning long-term goals with short-term actions, and fostering inclusive decision-making. This is where the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development (FSSD)is expected to be able to help. Developed through an international consensus process, the FSSD is grounded in a principled definition of sustainability and is operationalized through the ABCD process—a four-step planning method that includes building shared awareness and vision (A), mapping the current reality in relation to the vision (B), co-creating potential solutions (C), and prioritizing among the solutions to make strategic action plans (D) (Sandilya, 2020; Wälitalo et al., 2020, 2022). It promotes systems thinking, stakeholder co-creation, and backcasting from sustainability principles, offering a structured, iterative way for cities and organizations to develop transition strategies that are both visionary and grounded in context (Aldabaldetreku et al., 2016; Broman and Robèrt, 2017; Robèrt et al., 2017; von Langenstein et al., 2017; Vidler et al., 2019; Slob, 2023; Sroufe, 2025; Sylcox et al., 2025).

While the FSSD has been widely applied in corporate sustainability, regional development, and institutional planning in Europe and North America, its use in rapidly urbanizing contexts in the Global South—particularly in relation to mobility systems—remains limited. As such, there is a need to explore how such a framework can be meaningfully adapted and applied in African cities, where implementation challenges are shaped by unique governance dynamics, informal transport systems, and socio-political constraints. This paper examines how the FSSD, operationalized through its ABCD strategic planning process, could be used to bridge the implementation gap in sustainable mobility transitions in African cities.

In this research, the FSSD’s ABCD process was used as an analytical lens in four East African cities—Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu—which participated in two major EU-funded development projects (2020–2025): the SOLUTIONSplus project and the Smart Energy Solutions for Africa (SESA) project. SOLUTIONSplus sought to foster transformational change in urban mobility systems by implementing integrated electric mobility solutions in the selected cities (Teko and Lah, 2022; Lah, 2025), while SESA aimed to accelerate the uptake of sustainable energy and mobility solutions in African cities by supporting innovation, capacity building, and locally driven demonstration actions (Martins, 2025). Together, these two projects offered a valuable platform to assess the applicability of the ABCD process in real-world urban environments. For example, SESA’s Living Labs in five African countries provided real-life test beds where energy users and providers co-created and tested innovative solutions to ensure they meet user needs and fit the local context.

Within both projects, many activities inherently mirrored components of the FSSD’s ABCD framework. Stakeholder engagement processes, the development of strategic planning tools, and efforts to strengthen institutional collaboration were aligned with the framework’s steps. Project activities—including resident perception surveys, stakeholder interviews, co-creation workshops, and policy reviews—were intentionally structured around the ABCD process to co-develop shared sustainability visions (corresponds to A), diagnose systemic barriers (corresponds to B), and identify and prioritize locally grounded solutions (corresponds to C and D). In other words, elements of the framework were present in practice, even if not explicitly labeled as such, illustrating its relevance on the ground.

The cities themselves provided diverse settings to test the flexibility and relevance of this strategic approach. Nairobi features active civil society engagement and a dynamic private sector but is hampered by institutional fragmentation (Wood, 2019; Annan, 2022; Sverdlik et al., 2025). Kigali benefits from relatively strong policy discipline and centralized governance but has limited channels for bottom-up participation (Iyakaremye, 2016; Aldean, 2017; McMahan, 2021; Pailman, 2024). Dar es Salaam presents a hybrid environment shaped by both national planning and international donor influence, with growing informal transport networks and limited horizontal coordination (Appelhans and Baumgart, 2019; Appelhans and Magina, 2021; Appelhans, 2024; Kombe and Muheirwe, 2024). Finally, Kisumu represents a secondary city—in contrast to the three capital cities—where rapid development is underway and there is an opportunity to pursue more sustainable pathways before reaching the complexity of the larger capitals (Cirolia, 2019; Galuszka, 2021; Martins, 2025).

By focusing on strategy, systems thinking, and participatory planning, this paper positions the FSSD not as a universal solution, but as a potential framework whose applicability in rapidly urbanizing African contexts requires critical examination. Specifically, the study investigates whether, and through which mechanisms, the FSSD and its ABCD process can contribute to bridging the persistent implementation gap in sustainable mobility transitions in East African cities. The central hypothesis is that while many strategic components for implementation already exist such as policies, pilot projects, and institutional initiatives, the FSSD may provide a structured way to align these fragmented elements into more coherent and actionable pathways.

2 Methodology

2.1 Research design

This study employed a mixed-methods design (McKim, 2017; Mackey and Bryfonski, 2018; Dawadi et al., 2021) guided by the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development and its ABCD process (Broman and Robèrt, 2017; Robèrt et al., 2017). The FSSD served as the overarching analytical and strategic framework for integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Sardana et al., 2023). The research was carried out within the context of two multi-country, EU-funded initiatives—SOLUTIONSplus (SolutionsPlus, 2024) and SESA (Smart Energy Solutions for Africa) (SESA, 2025)–implemented between 2020 and 2025 to support electric mobility and sustainable energy transitions in African cities.

Four East African cities (Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu) were selected as case studies due to their participation in these projects and their ongoing engagement in sustainable urban mobility reforms (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). More city context is provided in section 3.

2.2 The FSSD and its ABCD process

The Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development provides a structured, principled approach to planning and decision-making for sustainability. At its core are eight sustainability principles (SPs), which outline conditions that must not be systematically violated if a system (such as a city’s mobility system) is to remain sustainable over the long term(Robert, 2009; Missimer, 2015; Broman and Robèrt, 2017; Sandilya, 2020). More specifically, the SPs define the sustainability of any system as not contributing to:

-

Pollution of nature through systematically increasing concentrations of substances:

-

SP1: concentrations of substances from the Earth’s crust (e.g., fossil fuels and mined metals).

-

SP2: concentrations of substances produced by society (e.g., NOx emissions, CFCs).

-

Physical destruction of nature through systematically increasing degradation:

-

SP3: physical degradation of ecosystems (e.g., deforestation, loss of wetlands).

-

Destruction of the socio-economic system by exposing people to structural barriers to:

-

SP4: health (e.g., hazardous working conditions, overwork).

-

SP5: influence (e.g., exclusion from decision-making or suppression of expression).

-

SP6: competence (e.g., barriers to knowledge, education and personal development).

-

SP7: impartiality (e.g., discrimination or corruption).

-

SP8: meaning-making (e.g., suppression of culture or inability to participate in society’s development).

To operationalize these principles, the FSSD employs the ABCD planning process, a four-step iterative methodology used for backcasting (Bibri, 2018; Camilleri et al., 2021; Trein and Ansell, 2021) from a shared vision of sustainability. These steps are:

-

Awareness and Visioning (A): building a common understanding of the system and co-creating a desired future aligned with the sustainability principles.

-

Baseline Mapping (B): assessing the current reality relative to that vision to identify challenges and opportunities (i.e., gaps between current conditions and the sustainable vision).

-

Creative Solutions (C): generating innovative ideas and options to bridge the gaps between the current state and the desired future.

-

Down to Action (D): prioritizing ideas and options to create concrete actions as part of strategic roadmaps for implementation, and establishing monitoring mechanisms (Figure 1).

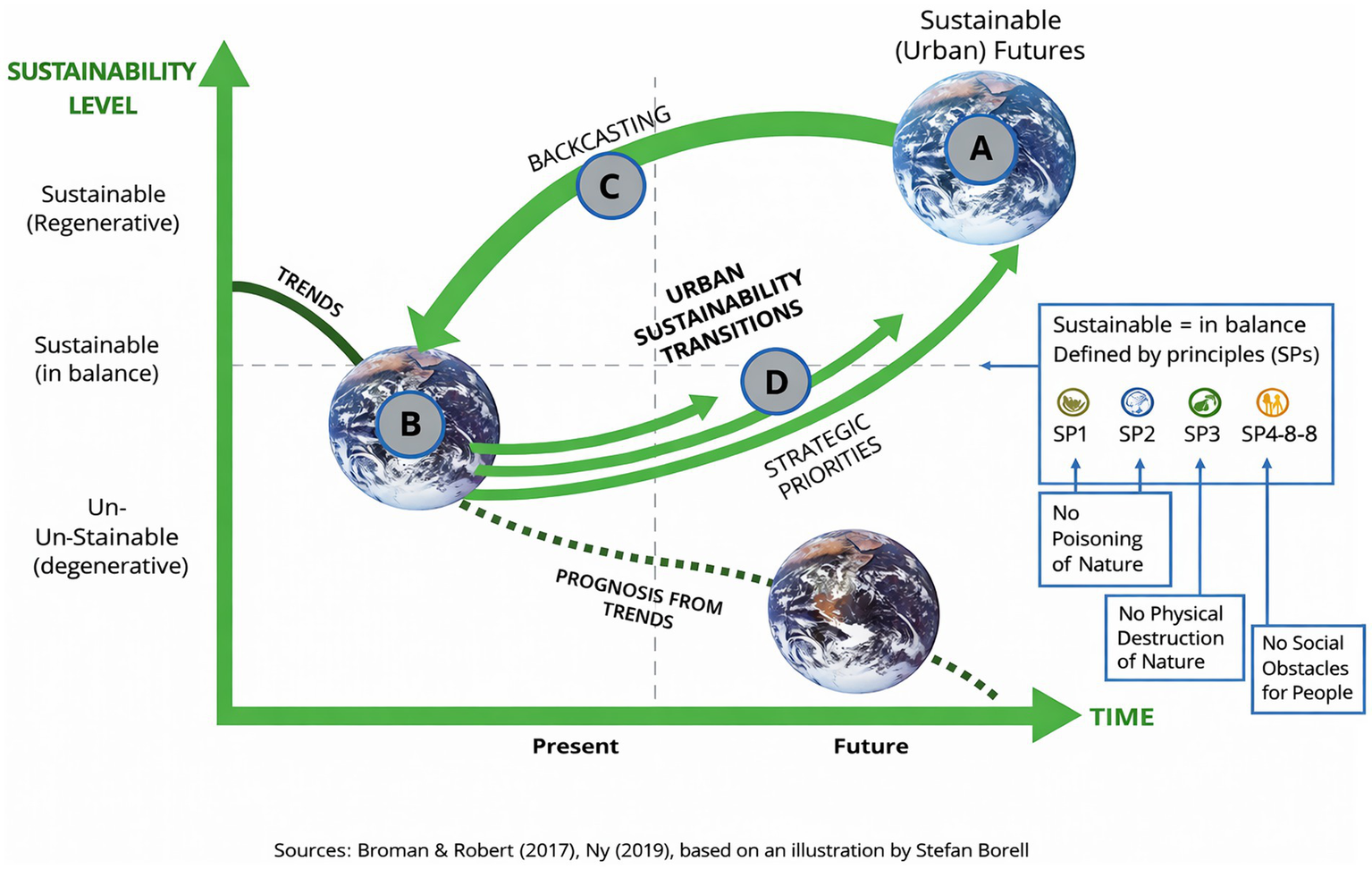

Figure 1

A schematic illustration of the ABCD process, adapted from Broman and Robèrt (2017) and Ny et al. (2019).

2.3 Combining the ABCD framework with specific data collection methods

The study integrated the ABCD framework with various data collection and engagement methods to ensure both strategic structure and empirical grounding. In practice, the research team mapped each method onto the corresponding step of the ABCD process, thereby demonstrating how general framework steps translate into concrete activities on the ground.

2.3.1 The ABCD steps

2.3.1.1 Step A: awareness and visioning

In the initial step (A), stakeholders were engaged to establish a shared vision for sustainable mobility in each city. This involved extensive collaboration with residents, government officials, and technical experts to outline a desired future state for urban transport (Teko and Lah, 2022; Lah, 2023, 2025). Each city’s project team convened diverse stakeholder groups—from government, civil society, the private sector, and academia—to co-create a sustainability vision. For instance, in Nairobi the visioning exercise centered on reducing reliance on fossil-fuel transport, increasing the share of walking and cycling trips, and enhancing equity in transport access. In Kigali and Dar es Salaam, participants emphasized scaling up efficient public transport and integrating non-motorized transport infrastructurewhile in Kisumu, the SESA living-lab facilitated locally grounded visioning that highlighted the need for affordable, community-based e-mobility options, improved safety for women and youth, and solutions aligned with lakeside travel patterns and short-distance urban trips (Zahid, 2023; SESA, 2025). These visioning workshops built a common awareness of current challenges and an inspiring picture of the future, laying the foundation for strategic planning.

2.3.1.2 Step B: baseline mapping

Following visioning, the process moved to assessing current conditions relative to the shared vision. This Baseline Mapping step (B) involved identifying systemic barriers, institutional dynamics, and mobility practices that diverged from the sustainability principles or the agreed vision (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). A combination of qualitative and quantitative tools was used to map the gap between the present state and the envisioned future (Lah, 2023). In addition to the formal data collection tools, the research team also drew on observational insights gained through their ongoing participation in project workshops and pilot activities which helped contextualize stakeholder perspectives. These experiential observations enriched the diagnostic process by clarifying discrepancies in reported data and deepening understanding of operational realities in each city (Noble et al., 2025). By comparing “where we are” to “where we want to be,” stakeholders could pinpoint misalignments and root causes that needed to be addressed. This diagnostic phase ensured that any proposed actions would be grounded in an accurate understanding of local realities and constraints.

2.3.1.3 Step C: creative solutions

With the baseline established, the third step (C) focused on brainstorming and developing strategic options to close the identified gaps. Stakeholders were encouraged to generate innovative, context-sensitive ideas bridging the distance between current mobility realities and the sustainable vision. This phase emphasized open creativity without immediate constraints, while still being anchored in the sustainability principles (Zahid, 2023; Medina-Molina et al., 2024; Haou et al., 2025; Junaid et al., 2025). The aim was to tap into local knowledge and global best practices to formulate a menu of potential solutions—from policy reforms and technological innovations to community initiatives—that could move the city toward its vision.

2.3.1.4 Step D: down to action (prioritization and planning)

The final step (D) involved evaluating and prioritizing the proposed actions based on criteria such as feasibility, impact, equity, and alignment with the Step A vision. Stakeholders engaged in structured discussions or workshops to assess which actions could be advanced immediately, which required enabling conditions first, and how progress would be monitored over time (Hamurcu and Eren, 2020; Wälitalo et al., 2022). This prioritization stage translated the creative ideas into an actionable strategy, essentially turning a wish-list of solutions into a coherent plan with short-term and long-term elements. It ensured that the transition strategy was not only ambitious but also practical and sequenced for implementation.

2.3.2 Data collection methods supporting each step of the ABCD

To support and inform the ABCD planning steps, a variety of data collection methods were employed. These methods provided empirical evidence and stakeholder input at each stage, enriching the analysis and ensuring that the strategic planning remained grounded in on-the-ground realities (Table 1).

Table 1

| Method | Description/purpose | Primary ABCD step(s) supported |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaires (Residents’ Survey) | 201 surveys administered across four cities; purposive sampling ensuring diversity (gender, age 18–65, socioeconomic background); multilingual facilitation (Kiswahili, Luo, Kinyarwanda/French). Explored mobility behaviours, satisfaction, governance perceptions, and attitudes to e-mobility. | Steps A & B: Visioning Baseline Mapping |

| Key Informant Interviews (n = 18) | Semi-structured interviews with national/city government, private sector, academia, NGOs/IOs. Provided insights on governance challenges, implementation barriers, institutional dynamics and solution feasibility. | Steps B, C & D: Baseline Mapping, Creative Solutions, Down to Action |

| Focus Group Discussions (Regional FGDs) | Four regional FGDs (2020–2024) on an annual basis with five technical experts. Synthesised cross-city insights, validated emerging patterns, and discussed implementation challenges across Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu. | Steps B & C: Baseline Mapping, Creative Solutions |

| Stakeholder Workshops (City-Level) | Participatory workshops with city officials, informal transport actors, civil society groups, private sector stakeholders and academia. Helped build shared awareness of mobility challenges, reviewed preliminary findings, and co-developed solution pathways and prioritisation criteria. | Steps A, C & D: Awareness & Visioning; Creative Solutions; Down to Action |

| Policy Document Review | Analysis of national and city mobility strategies, regulatory frameworks and transport plans to identify alignment with sustainability principles and uncover gaps requiring policy action. | Step B: Baseline Mapping |

| Researcher Observation | Contextual insights drawn from project involvement, site visits, pilot deployments and stakeholder meetings. Informed the initial system understanding, supported interpretation of mobility practices and governance realities and enriched solution deliberation. | Steps A–D (cross-cutting, with strongest influence on Steps A & B) |

Data collection methods and ABCD alignment.

2.3.2.1 Questionnaires

A residents’ survey was conducted to gather public perceptions and experiences regarding mobility infrastructure and governance (primarily supporting Step B of the ABCD). A purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure diversity across gender, age, and socioeconomic background, while adapting to the specific socio-spatial structures of each city. The survey targeted adult residents aged 18–65, with at least basic literacy and education up to high school level, to ensure that participants were able to meaningfully engage with the questionnaire content. Although purposive sampling is typically associated with expert informants, in this study it was applied to resident selection to ensure balanced inclusion across gender, age range (18–65), and different socioeconomic realities reflected in diverse neighbourhoods and mobility patterns. Surveys were administered in public, community, and institutional settings relevant to each city’s mobility landscape, such as neighbourhood forums, transport hubs, markets, universities, and community organisations (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

Although the questionnaire was prepared in English, multilingual research assistants supported comprehension and response validation by translating and interpreting in locally relevant languages: Kiswahili in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, Luo in Kisumu, and Kinyarwanda or French in Kigali. Althouth the survey was designed to take 30 min per respondent, the average time in the end was approximately 45 min (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

To ensure respondent eligibility, in-built screening questions verified that participants were residents of the respective cities and fell within the intended demographic range. The sampling design also incorporated a gender balance requirement, resulting in a distribution of at least 25 men and 25 women per city. Respondents were recruited through the existing networks of project partners, including community and grassroots groups, university student associations, women’s and youth organisations, neighbourhood forums, and mobility-related professional networks. This allowed for inclusive engagement while ensuring coverage of diverse mobility patterns across:

-

Nairobi: community groups, neighbourhood forums, informal transport users, university networks

-

Kigali: organised community clusters, university networks

-

Dar es Salaam: major transport hubs, BRT corridors, university networks

-

Kisumu: market and boda boda associations, community based organizations, university networks

This approach strengthened the diversity of perspectives while remaining consistent with the participatory ethos of both projects (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

To further enhance methodological clarity, the overall sample of 201 survey respondents was disaggregated by city. The initial target was 55 respondents per city, selected pragmatically to support cross-city comparison within the ABCD framework rather than to produce statistically representative population estimates. The final number of valid responses reflects only those questionnaires that passed the data-quality checks; incomplete or inconsistent questionnaires were excluded. This resulted in Table 2.

Table 2

| City | Original sample | Excluded responses (Incomplete/Invalid) | Valid responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nairobi | 55 | 3 | 52 |

| Kigali | 55 | 5 | 50 |

| Dar es Salaam | 55 | 6 | 49 |

| Kisumu | 55 | 5 | 50 |

| Total | 220 | 19 | 201 |

Questionnaires per city and sample distribution.

This approach allowed the study to reflect the lived realities of a wide range of residents in all four cities, ensuring that mobility experiences, governance perceptions and priorities for sustainable transport were captured from a broad base of participants. The questionnaire included both closed and open-ended questions addressing modes of travel, satisfaction with mobility infrastructure, perceptions of governance, levels of public participation, and attitudes toward sustainable and electric mobility (Mackey and Bryfonski, 2018; Muller et al., 2021; Porter and Dungey, 2021; Smajic et al., 2022).

In addition, data on public perceptions and user experiences from SOLUTIONSplus pilot activities were reviewed to complement the primary data. For example, in Kigali, structured data collection was integrated into the deployment of 1,350 electric motorcycle taxis, involving a monitoring and evaluation process with 24 women drivers recruited through a gender-responsive model. Similarly, in Dar es Salaam, 39 electric three-wheelers were deployed to local riders as part of a living lab pilot and monitored over several months. In the SESA project, 8 structured interviews were also conducted to supplement these findings (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

2.3.2.2 Key informant interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted with individuals possessing expert knowledge or leadership roles in sustainable mobility. The sample comprised 18 key informants, including national and city government officials, technical experts, private-sector mobility providers, and representatives of regional/international development organizations. A semi-structured interview guide was used to focus on governance challenges, policy implementation issues, public engagement, and recommendations for improving sustainable mobility (supporting steps B, C and D). This flexible format allowed interviewees to provide detailed, nuanced insights (Porter and Dungey, 2021), and enabled the research to capture perspectives from those directly involved in policy or project delivery. These interviews provided qualitative depth to the baseline mapping, often explaining why certain gaps existed or how certain ideas could be implemented. It is important to note that Kisumu did not require a separate national government interview nor from the international organization (UN-Habitat representative), as the national-level respondents based in Nairobi provided a comprehensive overview applicable to both Kenyan cities (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025; Table 3).

Table 3

| City/Country | National Govt | City Govt | Academia | Private Sector | NGOs/IOs | Total Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nairobi (Kenya) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Kigali (Rwanda) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Kisumu (Kenya) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 18 |

Key informant interviews distribution.

2.3.2.3 Focus group discussions

Four FGDs were held at a regional level across the duration of the SolutionsPlus project (2020–2024), each comprising five technical experts drawn from programme partners, experts and international project coordinators. These regional FGDs were designed to synthesise cross-city insights, validate emerging patterns, and discuss implementation challenges that cut across the four study cities (Porter and Dungey, 2021) (supporting steps B and C). A discussion guide helped keep conversations on track—covering current mobility practices, key challenges, and innovative solution pathways—while allowing participants to interact and build on each other’s points. These sessions were recorded and transcribed for analysis (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). The focus groups reinforced the creative solutions phase by generating ideas in a group setting and revealing consensus areas or divergent viewpoints among experts (SolutionsPlus, 2024).

In addition to the expert FGDs, stakeholder workshops formed a core component of the peer-to-peer learning exchanges in both SOLUTIONSplus and SESA. These workshops brought together city officials, informal transport representatives, civil society groups, private-sector actors, and academic partners to jointly review preliminary findings and refine emerging solution areas. They also functioned as collaborative spaces for co-developing priority actions under Steps C and D of the ABCD process (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

2.3.2.4 Policy documents review

The study also reviewed existing mobility policies, strategies, and plans in Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu. National and city-level policy documents, strategic plans, and regulatory frameworks were analyzed using a thematic approach. The review sought to identify content related to sustainable mobility, references to sustainability principles, and gaps or misalignments in current policy (Schiller and Kenworthy, 2017; Pojani and Stead, 2018; Jensen et al., 2020; Alazmi and Alazmi, 2023; Dinbabo and Mazani, 2025). This provided a context for the baseline mapping (supporting step B), highlighting where official strategies already support the shared vision or where policy changes might be needed. Examining these documents systematically allowed the research to uncover patterns—for example, recurring emphasis on certain modes, or neglect of others like non-motorized transport—thus also informing the strategic prioritization in Step D.

2.3.2.5 Researcher observation

In addition to surveys, interviews, FGDs and document reviews, the research team drew on experiential insights gained through direct participation in project meetings, stakeholder workshops, site visits, and pilot implementation activities across all four cities. Although no formal or systematic field-observation protocol was applied, the researchers’ ongoing professional engagement in SOLUTIONSplus and SESA provided contextual understanding that contributed to triangulation of findings (Noble et al., 2025). These observational insights helped interpret discrepancies in stakeholder responses, shed light on practical implementation challenges, and deepen the analysis of governance, infrastructural, and behavioural dynamics that were evident on the ground in Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam and Kisumu (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

2.4 Data analysis approach

All data was analysed using a mixed-methods approach consistent with the ABCD process of the FSSD. Quantitative and qualitative datasets were examined separately and then integrated during synthesis to triangulate findings across sources.

Closed-ended questionnaire items were analysed using descriptive statistics (frequency counts and percentages) to identify patterns in mobility behaviours, satisfaction with infrastructure, governance perceptions, and attitudes toward sustainable and electric mobility. Given the exploratory and comparative nature of the research, descriptive patterns were compared across the four cities to support the cross-city interpretation required for the ABCD baseline (Step B) and vision–gap mapping (Winkler et al., 2023; Babapourdijojin, 2025).

The interviews, focus group discussions, and workshop notes were analysed using a thematic analysis approach. Transcripts and researcher notes were coded inductively and then grouped into higher-order themes (Nyumba et al., 2018; Saunders et al., 2023; Dawson et al., 2024) aligned with the sustainability principles and the ABCD stages.

Three coding cycles were applied:

-

Initial coding: capturing stakeholder expressions on mobility challenges, governance practices, lived experiences, and views on e-mobility (Devullapalli, 2024; Brouwers et al., 2025).

-

Axial coding: grouping similar codes and identifying relationships among them (Vollstedt and Rezat, 2019; Williams and Moser, 2019).

-

Selective thematic synthesis: refining codes into core analytical themes (Naeem et al., 2023; Ahmed et al., 2025) that informed Steps A–D of the ABCD framework.

Across cities, the following overarching themes emerged from the qualitative analysis:

-

Governance fragmentation and institutional misalignment (Step B / SP6)

-

Trust deficits and public disengagement (Step B / SP5, SP7)

-

Infrastructure and service gaps, particularly for walking, cycling, and e-mobility (Step B / SP4, SP6)

-

Role of informality as both a backbone and barrier in mobility systems (Step B / SP5, SP7)

-

Community-grounded mobility needs and tacit geographic knowledge (Step A/SP4, SP5)

-

Co-creation of solution pathways and experimentation dynamics (Steps C & D/SP5, SP6, SP7)

These themes were subsequently used to structure the comparative analysis in Section 3 and to inform the synthesis of strategic actions developed during the ABCD process.

Integration of mixed data: Insights from surveys, interviews, FGDs, workshops, policy documents, and researcher observation were triangulated during Steps C and D. This allowed convergence across data sources, strengthened internal validity, and ensured that strategic recommendations reflected both empirical evidence and lived experience across the four cities.

2.5 Study limitations

While this study draws upon a diverse set of methods (policy analysis, surveys, interviews, and participatory workshops), several limitations should be noted. First, the research was embedded within externally funded demonstration projects (SESA and SOLUTIONSplus), which may have introduced selection bias in terms of which cities, stakeholders, and initiatives were emphasized. Second, while the ABCD process provided a consistent guiding structure, participation varied across cities due to contextual constraints, differing levels of political will, and time limitations. For instance, some cities had more robust stakeholder turnout in workshops than others, potentially influencing the breadth of perspectives captured. Finally, despite efforts to triangulate findings, the dynamic nature of project implementation means that some recent policy shifts or stakeholder changes may not have been captured during the study period. These limitations notwithstanding, they do not detract from the broader insights gained into strategy, governance, and institutional alignment for sustainable mobility transitions.

2.6 Ethical considerations

All survey and interview activities reported in this article were implemented within the EU-funded SOLUTIONSplus and Smart Energy Solutions for Africa (SESA) projects. Both projects are subject to the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 ethics requirements and have dedicated ethics work packages that govern research involving human participants, personal data and non-EU contexts. In all cases, participation was voluntary and data was anonymised prior to analysis. No additional institutional ethical approval was required, as all procedures fell under the ethics governance frameworks of the EU Horizon 2020 programme (Europe, H, 2021; Lanzerath, 2023; Stancu and Agheniței, 2025).

3 Results and analysis

This section presents the results of the multi-site research conducted in Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu. The analysis draws on data from surveys, interviews, policy reviews, and co-creation workshops, and is structured around the ABCD process of the FSSD. In what follows, findings from both the SOLUTIONSplus and SESA projects are analyzed, offering insights from their demonstration actions and stakeholder engagement efforts. SOLUTIONSplus focused on implementing integrated electric mobility solutions across several urban contexts, while SESA emphasized sustainable energy and mobility innovations, particularly in Kisumu (among other African cities). By examining the results through the ABCD lens, we illustrate how each step of the framework manifested in practice and what this means for bridging the research–implementation gap.

3.1 City contexts

3.1.1 Overview

A comparative interpretation of the survey results required an understanding of the spatial, demographic, economic and governance contexts that shape mobility patterns in each city. These contextual elements provided the basis for synthesis through the ABCD method by situating the numerical findings within broader socio-spatial realities. They also clarified why resident perceptions differ across cities and how local conditions shape the feasibility of sustainable mobility transitions.

3.1.2 City contexts: Nairobi, Kigali, Dar Es Salaam, Kisumu

Nairobi’s mobility system is shaped by rapid population growth, a dispersed urban form, and a historically fragmented governance structure. According to the 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census, Nairobi City County has approximately 4.4 million residents living within 696 km2, making it one of the most densely populated urban counties in East Africa (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2019, 2023; NAMATA, 2019). Governance challenges stem from long-standing institutional overlaps among national and county agencies such as NTSA, KURA, KeNHA, and NaMATA which contribute to gaps in planning, enforcement, and implementation. These structural complexities, combined with uneven historical investment patterns and spatial inequities, continue to influence mobility experiences and public dissatisfaction with transport governance (Klopp and Cavoli, 2019; Basil and Nyachieo, 2023; Sverdlik et al., 2025).

These challenges are compounded by colonial-era spatial planning, which established segregated districts, hierarchical road networks and uneven infrastructural investment patterns that still underpin Nairobi’s socio-spatial inequalities (Home, 2014; Becker, 2020). Informal transport dominates due to the absence of a fully formalised public transport system, while recent infrastructure projects have reinforced perceptions of car-centred planning at the expense of walking, cycling and public transport. Spatial disparities between well-serviced northern suburbs and underserved eastern and southern districts shape mobility experiences and help explain why Nairobi reports lower satisfaction and weaker trust in governance as is elaborated in section 3.2 through the ABCD method (Mutongi, 2017; Lubaale and Opiyo, 2020; Martin, 2020; Galuszka et al., 2021; Basil and Nyachieo, 2023; Nyamai, 2020).

Kigali’s mobility landscape reflects a highly centralised and coordinated governance system, supported by clear national policies, strong implementation capacity, and a unified urban planning framework. While hierarchical planning traditions have historical roots in colonial administration, Rwanda’s contemporary model of centralised governance is more strongly shaped by post-1994 state-building efforts that emphasise coherence, discipline, and integrated urban management (Nyiransabimana et al., 2019; Manirakiza et al., 2025). The City of Kigali is home to approximately 1.75 million residents within an area of about 730 km2 and has a predominantly urban, high-density population structured through planned neighbourhood clusters (Nshimiyimana, 2025). Recent investments in non-motorised transport infrastructure and integrated mobility planning contribute to comparatively higher satisfaction levels among residents. SolutionsPlus pilot activities, including the deployment of 1,350 electric motorcycles and targeted monitoring with women drivers, further demonstrate Kigali’s capacity to integrate innovation into formal mobility systems (SolutionsPlus, 2024). The city’s institutional coherence and emphasis on transparency help explain its consistently strong governance and trust indicators, as later discussed in Section 3.2.

Dar es Salaam’s mobility system is shaped by its expansive metropolitan footprint, rapid population growth and a fast-changing peri-urban environment(Kombe and Muheirwe, 2024). According to the 2022 National Population and Housing Census, the city hosts approximately 5.38 million residents across 1,593 km2, making it one of the largest and most densely populated urban centres in East Africa (Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 2022). Its linear coastal development pattern reflects both German and British colonial investments that prioritised port operations, rail connectivity and export-oriented infrastructure, creating spatial structures that continue to influence contemporary mobility demands (Brennan and Burton, 2007; Brennan et al., 2007; Edward, 2022). Despite the introduction of the BRT system, the city remains heavily dependent on informal public transport, particularly daladala services. Governance fragmentation—arising from overlapping mandates among national, municipal and city authorities—further contributes to gaps in planning, regulation and enforcement. SolutionsPlus pilot deployments, including electric three-wheelers, operate within this complex environment and illustrate both the opportunities for innovation and the persistent structural constraints (Galuszka et al., 2021). These dynamics help explain Dar es Salaam’s mixed satisfaction levels, where optimism generated by BRT improvements coexists with concerns about congestion, affordability and persistent informality.

While the other three cities represent current (Nairobi, Kigali) and former (Dar es Salaam) capital cities, Kisumu’s mobility context is distinct due to its secondary and mid-sized scale, lakeside geography and emerging innovation ecosystem. The urban area covers roughly 297 km2, with close to 400,000 residents in the core city and just over 1.1 million people in the wider metropolitan region (Obiero, 2022; K’oyoo and Breed, 2024). Historically, Kisumu was marginalised within colonial economic planning, receiving fewer mobility and infrastructure investments than Nairobi, a legacy that contributes to ongoing resource constraints and uneven development trajectories (Lesutis, 2021, 2022). Findings from SESA show that the city’s form—lower density, market-based trip generators and expanding peripheral settlements—shapes mobility needs and infrastructure gaps. Governance fragmentation is less pronounced than in Nairobi, though capacity limitations persist. Participation through community-based organisations and youth groups aligns well with SESA’s Living Lab approach. Early adoption of electric motorcycle pilots demonstrates strong acceptance and suitability for short-distance travel patterns (Galuszka et al., 2021; Martins, 2025; SESA, 2025).

The implications of these contextual conditions for sustainable mobility transitions are synthesised in Section 3.2 through the ABCD analysis.

3.2 Synthesis through the ABCD process

3.2.1 Awareness and visioning (A)

Across all cities involved, a shared aspiration emerged for more accessible, affordable, and environmentally sustainable mobility systems. Participants expressed concern over the dominance of private cars and unregulated informal transport modes, voicing a strong desire for more equitable, multimodal transport futures. This common vision—improved public transit, safer walking and cycling, and cleaner vehicle technologies—provided an early indication that stakeholders in these cities are aligned on what outcomes are desirable (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

The visioning phase also highlighted the importance of geographical context and tacit community knowledge (Güller and Varol, 2024; Cavoli et al., 2025) in shaping future mobility aspirations. Citizens in all four cities noted that mobility is deeply affected by local travel rhythms, environmental conditions and socio-economic realities. In Kisumu and Dar es Salaam, for instance, lakeside economies, heatwaves, seasonal market flows and peri-urban travel patterns influence mobility needs echoing research that calls for planning approaches attentive to situated geographies, local labour flows and the practical knowledge of communities navigating diverse terrains. Incorporating this tacit knowledge into visioning was viewed as essential for designing mobility systems that work with, rather than against, everyday patterns of movement (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

The visioning phase also exposed gaps in planning literacy. While many urban planners and city officials were somewhat familiar with structured frameworks like the FSSD, only 34% of surveyed civil society actors and fewer than 20% of informal transport operators had ever encountered formal tools for long-term mobility planning. This knowledge divide became apparent during the early stages of the SOLUTIONSplus Nairobi pilot, which required redesign efforts to bridge technical knowledge with local lived experience (SolutionsPlus, 2024). In other words, even as a shared vision was taking shape, not all participants initially had the same capacity to engage with strategic planning concepts—an insight that underscores the need for inclusive capacity-building as part of the visioning process.

In Kisumu, the visioning activities under SESA highlighted the benefits of grounding future mobility visions in community priorities. Participatory tools helped engage groups historically excluded from planning—including women and informal operators—and fostered a sense of shared ownership over the transition to electric mobility (SESA, 2025). This inclusive visioning meant that the emerging vision in Kisumu reflected on-the-ground realities and aspirations (e.g., interest in affordable e-motorcycle schemes and improved safety for female riders), not just top-down policy goals.

Similarly, city-specific focuses emerged within the overall vision. In Kigali, 82% of surveyed stakeholders highlighted expanding mass public transit as a key priority, aligning with Rwanda’s national agenda on smart, green urbanism. In Nairobi, where decades of road-centric development have entrenched inequalities, 63% of respondents called for reversing this legacy through investment in NMT and public transport infrastructure. These concerns resonate with studies showing that colonial-era planning and regulatory systems continue to shape mobility inequalities, including in the allocation of road space, land use, and accessibility for marginalised communities (Engerman and Sokoloff, 2005; Home, 2014; Edward, 2022). In contrast, Dar es Salaam, stakeholders praised the success of the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system but noted its limitations—particularly poor last-mile connectivity in peri-urban areas that left many residents without effective access to the BRT. They called for a continuation of the work on the BRT to make it more inclusive (SolutionsPlus, 2024).

Finally, across cities, stakeholders articulated the need for mobility solutions that respond to cognitive and sensory urban experiences(Carlsson-Kanyama and Lindén, 1999; Klinger and Lanzendorf, 2016; Abbassy et al., 2025). Discussions in markets, interchanges and neighbourhood nodes revealed interest in e-mobility devices designed for daily tasks such as e-bikes or motorcycles that can accommodate shopping loads or passenger-ferrying aligning with emerging research on how multisensory and cognitive dimensions of urban design can support inclusive mobility futures (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025; Güller and Varol, 2024). These insights provide early cues on how technological design and urban form could be better aligned in the later phases of the ABCD process.

Together, these findings demonstrate that while a broad common vision of sustainable, people-centred mobility is shared across the four cities, each city’s visioning process reflects its distinct geographical realities, governance histories and community experiences—elements that shape the direction and feasibility of implementation steps explored in the next phase of the ABCD analysis.

3.2.2 Baseline mapping (B)

The baseline mapping revealed significant misalignments between the aspirational visions outlined in Step A and the operational realities on the ground. In particular, four recurring challenge areas became evident: governance fragmentation, trust deficits, infrastructure gaps, and the role of informality. Each of these areas represents a category of systemic misalignment needing attention for the cities to progress toward their visions.

3.2.2.1 Governance and institutional fragmentation

Stakeholders in the SOLUTIONSplus project reported fragmented transport governance structures impeding implementation (this primarily relates to structural barriers to competence or sustainability principle 6 of the FSSD). In Nairobi, for example, multiple agencies—the National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA), Nairobi Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (NaMATA), the Kenya Urban Roads Authority (KURA), among others—coexisted with overlapping mandates, leading to unclear responsibilities and duplication of planning efforts. A similar pattern was observed in Dar es Salaam, where the Dar Rapid Transit agency (DART) and municipal authorities had overlapping roles, creating institutional inefficiencies. SOLUTIONSplus coordination meetings revealed that pilot project rollouts were often delayed by bureaucratic bottlenecks and conflicts in approval processes (SolutionsPlus, 2024). By contrast, Kigali’s more streamlined institutional setup (with a central authority overseeing transport) meant its pilot processes encountered fewer bureaucratic obstacles.

In Kisumu (under the SESA project), the pilot project experienced relatively smooth implementation largely because its small scale did not require complex multi-agency intervention. This highlighted a paradox in governance: while strong institutions and regulations are typically seen as enablers of sustainable transitions, in some contexts the absence of heavy bureaucratic oversight (or at least a hands-off approach by authorities) can create agility for experimentation and rapid implementation. Kisumu’s ability to bypass slow administrative procedures allowed local partners to co-design and execute the e-mobility pilot more efficiently, suggesting that over-bureaucratized systems may sometimes hinder innovation rather than support it (Cavoli et al., 2025; Martins, 2025; SESA, 2025). The lesson is that clear governance alignment, not necessarily more institutions, is needed: either by streamlining agencies or by granting pilot projects special coordination mechanisms to avoid red tape.

Moreover, the persistence of fragmented governance reflects deeper colonial-era planning legacies (Home, 2014; Becker, 2020), where transport and land-use systems were historically structured along segregated administrative lines. These inherited governance architectures, still visible in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam for instance, reinforce institutional silos and shape uneven service provision, thereby influencing the baseline realities captured in the survey. Understanding these structural path dependencies explains why institutional coordination remains one of the most significant barriers across the four cities.

3.2.2.2 Trust deficits and public disengagement

Results from SOLUTIONSplus indicated that public trust in transport governance was notably low in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. In Nairobi, 71% of survey respondents reported that information on transport projects was “not readily available,” and 68% felt excluded from decision-making processes (relating to structural barriers to influence and impartiality or sustainability principles 5 and 7 of the FSSD). By contrast, Kigali fared better: 59% of respondents expressed satisfaction with the communication channels of the Rwanda Transport Development Agency (RTDA), suggesting more effective public outreach (SolutionsPlus, 2024).

The SESA project in Kisumu demonstrated that trust can be built when communities are genuinely engaged from the early design stages and when transparency measures (like open budget sessions or public dashboards) are in place. Kisumu’s approach of involving community representatives in project planning and openly sharing pilot results fostered a greater sense of trust and buy-in among the public (SESA, 2025). These findings underscore the need for systematic stakeholder engagement approaches in implementation. In cities where skepticism toward authorities is deeply entrenched, early and ongoing community involvement and transparency are not just “nice-to-have” features but critical components of successful implementation.

Trust dynamics were also shaped by geographical and livelihood realities. For example, lakeside communities in Kisumu, fishery-based neighbourhoods, and peri-urban settlements in Dar es Salaam exhibit mobility challenges linked to seasonal work, fluctuating incomes and environmental factors such as heatwaves or flooding. These situated experiences shaped residents’ perceptions of fairness, responsiveness and inclusion in planning processes, consistent with research highlighting the importance of community-tacit knowledge (Güller and Varol, 2024; Cavoli et al., 2025) in transport governance (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

Additionally, the role of universities and NGOs emerged as critical in shaping trust pathways. In Kigali and Kisumu, universities acted as neutral conveners and facilitators of participatory processes (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025), aligning with recent scholarship on transformative agency, where academic institutions help bridge technical planning and community priorities (El-Husseiny et al., 2024).

3.2.2.3 Infrastructure deficits and modal imbalance

The baseline assessment also highlighted severe infrastructure gaps, particularly in support of non-motorized transport (NMT) (this also relates to structural barriers to competence or sustainability principle 6 of the FSSD). Data from SOLUTIONSplus showed that 54% of daily trips in Nairobi, 49% in Dar es Salaam, and 44% in Kigali are made on foot—yet infrastructure investment does not reflect this reality. In Nairobi, for instance, only ~2% of the transport budget is allocated to NMT, despite the city having a progressive NMT policy on paper. Over 60% of respondents in both Nairobi and Dar es Salaam cited poor-quality sidewalks, lack of shading, and safety/security concerns as key deterrents to walking (relating to structural barriers to health or sustainability principle 4 of the FSSD). Likewise, 73% of Dar es Salaam respondents noted that BRT stations were poorly integrated with walking and cycling routes, undermining the effectiveness of the public transit system. The SOLUTIONSplus demonstration report further pointed out that the lack of dedicated lanes and limited battery charging infrastructure were constraining the adoption of electric vehicles (SolutionsPlus, 2024).

SESA’s infrastructure pilots in Kisumu showed how even small-scale improvements can make a difference. For example, establishing a local “energy hub” with solar charging for e-mobility significantly improved electric bike uptake when it was co-designed with local users (ensuring convenient location, security, and added services). This indicates that targeted investments, if aligned with user input, can begin to close the infrastructure gap and encourage sustainable modes.

These infrastructure gaps cannot be understood without considering colonial and post-colonial land-use patterns, which privileged road-building for extractive and administrative purposes while deprioritising walking and cycling. This historical neglect contributes to today’s imbalance between dominant modes (private vehicles, motorcycles) and sustainable mobility options. Furthermore, stakeholders across cities highlighted the need for infrastructure that responds to the cognitive and sensory dimensions of urban life. Market areas in Kigali and Kisumu, for example, require e-mobility devices adapted for carrying goods, while shaded walkways and well-lit streets were frequently cited as essential for safe walking in Nairobi. This aligns with emerging research linking mobility design to multisensory urban experience, showing how tailored infrastructure can catalyse inclusive mobility patterns (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

3.2.2.4 Informality as systemic backbone (and barrier)

Informal transport operators—such as Nairobi’s matatus or the boda bodas in Kisumu and Dar es Salaam—account for the majority of motorized trips in these cities (over 75% in Nairobi, ~68% in Dar es Salaam). They are the de facto public transport system for most residents, yet they remain largely marginalized in formal planning processes. Exclusion of informal actors is partly rooted in colonial-era regulatory systems that criminalised informality while privileging formal, motorised transport systems. These structural biases persist and continue to shape mobility hierarchies today. Survey results showed that 81% of informal operators in Nairobi had never been consulted in any mobility planning, and 59% said they would welcome structured engagement or training opportunities if offered (Galuszka, 2021). This points to a vast reservoir of on-the-ground knowledge and capacity that is being left untapped due to the formal–informal divide (relating to structural barriers to influence and impartiality or sustainability principles 5 and 7 of the FSSD).

Both SOLUTIONSplus and SESA demonstrated that formal–informal integration is possible when partnerships are designed around co-benefits. In Kisumu, the introduction of electric motorcycles through a boda boda riders’ cooperative (supported by SESA) helped operators reduce fuel costs by ~40% and increase daily incomes by an average of 25%. In Dar es Salaam, SOLUTIONSplus supported training programs in EV maintenance and safety for informal operators, which in turn increased the informal sector’s participation in city-led transport forums (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). These examples show that informal actors can become champions of innovation when they are included as stakeholders—turning a potential barrier (informality and its associated chaos) into a backbone for sustainable solutions.

3.2.3 Creative solutions (C)

In the creative solutions phase, stakeholders in each city generated a portfolio of context-appropriate actions and strategies, drawing on both local insights and international best practices. The emphasis here was on practical interventions that still aligned with the ambitious sustainability goals set out in the vision. Across the cases, several common strategic solution themes emerged, reflecting both the shared challenges identified in the baseline and the shared aspirations from the visioning stage.

3.2.3.1 Multi-stakeholder coordination platforms

City partners in both projects proposed formalizing coordination through cross-sector mobility councils or working groups. This idea was directly inspired by the SOLUTIONSplus Nairobi Technical Working Group, which had proved essential in aligning university research, city planning departments, and donor efforts during the e-mobility pilot (SolutionsPlus, 2024). Stakeholders saw value in making such ad-hoc groups permanent: a formal council could continuously bring together agencies (transport, energy, urban planning), academia, civil society, and private sector representatives to ensure ongoing alignment beyond the life of any single project.

In Kigali, participants similarly advocated for a mobility innovation hub hosted by the University of Rwanda, building on the collaborative model seen during the project. This would institutionalize a space for joint problem-solving and training, comparable to the SESA-supported knowledge hub integration model where local universities partnered with city officials to share data and insights (SESA, 2025). The broad consensus was that without dedicated coordination bodies, many good ideas remain siloed within individual agencies or pilot projects.

3.2.3.2 Regulatory sandboxes for innovation

The concept of flexible regulatory zones or “sandboxes” emerged as a high-priority innovation policy. In Nairobi, stakeholders proposed allowing electric boda-boda (motorbike taxi) pilot operations under temporary special licenses, with supportive regulations contingent on meeting training and emissions performance benchmarks. This builds on a small-scale SOLUTIONSplus sandbox trial in Nairobi, which enabled informal operators to test electric vehicles under relaxed rules, coupled with training programs, to safely experiment without the full weight of standard regulations hindering them. Kigali stakeholders echoed the importance of adaptive regulatory frameworks, particularly for introducing electric buses and encouraging local assembly of e-vehicles—areas where traditional procurement and vehicle standards might be too rigid for nascent technology (SolutionsPlus, 2024).

The appeal of these sandboxes is that they create learning environments for innovation: cities can pilot new mobility solutions (like e-scooters, ride-sharing, etc.) in a controlled way, gather data, and adjust policies before scaling up. This approach recognizes that waiting for perfect regulation can stall innovation, whereas a sandbox provides a compromise between anarchy and over-regulation.

3.2.3.3 Community-driven e-mobility models

Community-based business models were recognized as critical to making e-mobility inclusive and sustainable. Stakeholders highlighted the role of cooperatives and Savings and Credit Cooperative Organizations (SACCOs) in financing, maintaining, and governing shared electric vehicle fleets. In Kisumu, a SESA pilot successfully enabled a women-led SACCO to operate a fleet of e-motorcycles, which created jobs while improving women’s access to markets and health facilities. This not only empowered a typically marginalized group but also ensured local ownership of the solution. In Nairobi, informal matatu and boda boda operators suggested cooperative-based lease-to-own schemes for electric vehicles, so that drivers could gradually gain asset ownership with the help of microfinance, rather than being perpetually renters (SESA, 2025). These community-driven models tie together social equity and financial sustainability, aiming to lower barriers to entry for cleaner technology and keep more economic benefits within local communities.

3.2.3.4 Digital public engagement tools

To enhance transparency and citizen input, stakeholders proposed various digital participation tools as low-cost, high-impact interventions. Examples included mobile apps for transit feedback, SMS-based polling for quick community surveys, and interactive public dashboards displaying project progress or transport data. Kigali has already piloted some digital feedback mechanisms through the RTDA’s online portal, where residents can submit comments on transport services. In Nairobi, there was enthusiasm for building on the open-data platform prototype created under SOLUTIONSplus, expanding it into a full public-facing mobility data portal linked to city planning systems (SolutionsPlus, 2024). Such tools were seen as ways to boost public engagement without heavy infrastructure—enabling two-way communication, crowdsourcing of issues (like broken streetlights or dangerous intersections), and greater accountability by making data (e.g., on congestion or emissions) visible to all.

3.2.3.5 Infrastructure upgrades for walking and cycling

Several groups stressed that new solutions must be coupled with substantial investments in walking and cycling infrastructure. This included proposals for safer sidewalks, shaded pathways, cycle lanes, and improved last-mile connections to public transport systems, especially in low-income and peripheral areas (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

3.2.3.6 Community e-mobility hubs

Another idea concerned creating neighborhood-based e-mobility hubs that would provide shared charging, battery-swapping, and maintenance services, often linked to youth or women’s cooperatives (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). Such hubs were envisioned as both mobility infrastructure and livelihood platforms.

3.2.3.7 Open-access mobility data platforms

Finally, stakeholders highlighted the importance of data sharing to improve planning and accountability. Proposals included city-wide data portals integrating formal and informal transport services, real-time traffic data, and emissions inventories to support both decision-makers and the public (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

Taken together, these proposals illustrate the breadth of solutions generated during Step C. While not all could be pursued immediately, they reflect the wide range of strategic possibilities under consideration. The subsequent Down to Action stage (Step D) focused on filtering and prioritizing among these ideas to produce actionable strategies tailored to each city context.

3.2.4 Down to action (D)

The “Down to Action” phase focused on filtering and prioritizing among the ideas from Step C to translate them into a coherent set of actionable strategies. Each city held structured prioritization workshops, where stakeholders evaluated proposed interventions using multi-criteria frameworks. Common criteria included feasibility (technical and financial), alignment with the sustainability vision, equity impacts, potential to catalyze wider change, and required resources or policy support (Ny et al., 2019; Thomson et al., 2020). Through this process, each city developed a short list of priority actions and an accompanying roadmap.

Across the four cities, there was a shared recognition that successful implementation would require coordinated action beyond fragmented projects. A frequent recommendation was to institutionalize coordination mechanisms that had proven useful during the pilots. For example, in Nairobi stakeholders strongly supported establishing a permanent mobility coordination platform to unite transport agencies, research institutions, civil society, and private actors. This directly drew from the experience of the SOLUTIONSplus Technical Working Group—an interim body that had significantly improved communication and alignment during the pilot. Participants saw that group as a blueprint for a standing committee or agency that could continue bridging silos beyond the project’s end.

Dar es Salaam and Kigali echoed similar priorities for formal inter-agency and public coordination. In Kigali, a concrete proposal emerged to create a “mobility innovation unit” within the University of Rwanda, institutionalizing the project’s academic-policy partnership model. This unit would act as a hub for knowledge exchange, ongoing pilot monitoring, and injecting fresh research (including student projects) into city decision-making (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

Another high-priority category of actions was addressing infrastructure deficits for walking and cycling. Participants from Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, in particular, underscored the need to vastly expand pedestrian sidewalks and cycling lanes, especially in low-income and peripheral areas that had been underserved. There was consensus that infrastructure upgrades should be bundled with safety improvements (e.g., lighting, safe crossings, drainage) to truly make walking and cycling viable and attractive (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). These proposals reflect an awareness that without safe infrastructure, the modal share of walking/cycling—though already high out of necessity—would never translate into a choice made by those who have alternatives.

Community-based e-mobility solutions also rose to the top during prioritization. Inspired by the success of SESA’s women-led electric motorcycle cooperative in Kisumu, stakeholders in other cities recommended establishing similar community e-mobility hubs targeting youth and women. These would provide lease-to-own EV programs, maintenance training, and battery-swapping services. Such models were seen as simultaneously tackling unemployment (by creating new green jobs and enterprise opportunities) and mobility inequities (by focusing on groups that face barriers in the current system). The cooperative approach was favored as a means to ensure inclusive ownership and shared responsibility, thus increasing the likelihood of long-term success (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025).

The creation of regulatory sandboxes was another widely endorsed action. Stakeholders in Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, and Kigali all agreed on the need for flexible innovation zones where new mobility solutions (like e-bike sharing, drone delivery, or other emerging tech) could be tested under temporarily relaxed regulations. This was informed by Nairobi’s sandbox experience under SOLUTIONSplus, where temporary exemptions allowed e-boda operators to test EVs while undergoing training (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). Formalizing this approach could help cities stay adaptive, quickly learning and iterating on regulations in response to pilot outcomes.

Finally, developing open-access urban mobility data platforms was seen as foundational. Dar es Salaam stakeholders proposed a city-owned open data portal integrating real-time information from buses, informal minibuses, and traffic sensors—enabling better planning and public transparency. In Nairobi, the idea was to expand the SOLUTIONSplus pilot’s data platform to include more datasets (e.g., an inventory of walking infrastructure, locations of EV charging, transport emissions data). Such platforms were envisioned to serve multiple audiences: policymakers (for evidence-based decisions), civil society (to monitor and hold authorities accountable), and businesses (to identify market opportunities) (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). In short, open data was considered a catalyst for innovation and accountability in implementing the prioritized actions.

4 Discussion and future research recommendations

This study set out to explore how East African cities can better bridge the persistent implementation gap in sustainable mobility transitions. Using Nairobi, Kigali, Dar es Salaam, and Kisumu as case studies, the FSSD and its ABCD process were used to structure an investigation of how structured, participatory planning could move cities from vision to action. The findings confirm that despite progressive policies and numerous donor-supported pilot initiatives, implementation challenges persist. These challenges are not simply technical; rather, they are deeply rooted in systemic factors such as institutional fragmentation, misaligned incentives, socio-political dynamics, and divides between formal plans and informal realities.

Below, we reflect on several key themes: reframing implementation as a systems challenge, the strategic value of the ABCD framework, the importance of structured experimentation (living labs and pilots), the centrality of inclusion, and the need for context-responsive and scalable models. We also discuss implications for policy and practice, and identify directions for future research.

4.1 Reframing implementation as a systems challenge

The results underscore that implementation failures are not only about isolated issues like funding gaps or weak enforcement (Tama et al., 2021). Instead, they stem from interlocking, system-level constraints: overlapping mandates, institutional silos, political misalignments, and entrenched trust deficits between formal authorities and informal operators (Urban Electric Mobility Initiative (UEMI), 2025; SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). In other words, the implementation gap is a symptom of deeper systemic misalignments.

Both the SOLUTIONSplus and SESA project experiences revealed that effective implementation required more than just technological solutions or one-off investments. For example, in Nairobi an electric bus pilot only gained real traction after a technical working group was formed, bringing together public agencies, universities, and private actors into ongoing dialogue (SolutionsPlus, 2024). In Kisumu, the adoption of a battery-leasing model for e-motorcycles accelerated once boda boda riders were directly involved in co-designing the business model (SESA, 2025). These instances illustrate that processes and partnerships—not just products—drive implementation success.

The ABCD process helped stakeholders reframe “implementation” not as a fixed end-point (i.e., simply getting a project done), but as a complex, iterative process of system change. By collaboratively mapping systemic barriers and then co-developing context-aware solutions, the cities moved beyond reactive problem-solving toward more coherent strategies rooted in long-term sustainability goals. Importantly, this approach built solutions on collaborative alignment rather than on the tenuous foundations of a single champion or rigid institution. Similar results have been documented elsewhere when adopting systems perspectives (Thomson et al., 2020; Ny et al., 2019). The implication is that urban implementation should be addressed as a holistic challenge—one that requires convening diverse actors to diagnose and act on system relationships, not just deploying technology or passing a law and expecting change.

4.2 The strategic value of the FSSD

The FSSD, through its ABCD methodology, is a valuable and highly applicable approach for navigating the complexity of implementation. Unlike conventional planning tools that may emphasize static checklists or narrow project metrics, the ABCD process enables cities to plan with a normative, principle-based vision while remaining adaptable to shifting realities and stakeholder needs (Kanyama, 2016; Wälitalo et al., 2020, 2022; Gossal, 2025). This dual focus—principled yet flexible—is crucial in the fluid context of rapidly urbanizing cities.

Participants across all four cities found tangible value in the structured sequencing of ABCD steps: starting with a shared vision (which set a unifying direction), then conducting a candid baseline diagnosis (which created a common understanding of problems), moving into creative solution-generation (which opened space for innovation), and finally strategic prioritization (which brought realism and focus). In Nairobi, for instance, informal transport operators who typically air grievances were able to use this structure to move from identifying problems to proposing concrete solutions (like flexible licensing schemes and EV training programs), feeling that their concerns translated into action plans. In Kigali, the ABCD process helped align the lofty goals of the national “smart city” agenda with the local realities of the transport system, resulting in calibrated interventions (e.g., improving transit integration) rather than calls for disruptive, impractical overhauls (SolutionsPlus, 2024).

This structured approach encouraged stakeholders to distinguish between immediate fixes and deeper structural changes. For example, calls for “more electric buses” were accompanied—through the ABCD discussions—by recognition of supporting measures needed (cooperative ownership models, citywide coordination platforms, adaptive regulation), which are essential for system-wide change (SolutionsPlus, 2024; SESA, 2025). In essence, the framework fostered strategic thinking: participants started to see pilot projects not as standalone endeavors but as pieces of a larger transition puzzle.

4.3 Embedding learning and experimentation into practice

Both SOLUTIONSplus and SESA emphasized demonstration projects and living labs as means to accelerate innovation. However, a caution that emerged (and is echoed in literature) is the risk of the “pilot trap”—where successful pilots fail to scale or translate into policy because they remain isolated (Sagaris et al., 2020; Ryghaug and Skjølsvold, 2021; Abdi and Lamíquiz-Daudén, 2022). The ABCD process offers a counterpoint to this risk by explicitly embedding mechanisms for reflection, prioritization, and planning for scale-up (Thomson et al., 2020) as part of the strategic process, rather than treating pilots as one-off experiments.

In practice, we saw this in Kisumu: SESA’s electric boda boda initiative was run as more than a tech demo; it was effectively a living lab that doubled as a learning platform. Riders, cooperatives, and officials treated the pilot as a chance to test cooperative business models, build trust between stakeholders (e.g., between riders and the city), and gather real-world user feedback on the e-motorbikes’ performance and acceptability. Because this pilot was framed as strategic experimentation rather than just deployment, it became a stepping stone for institutional learning and adaptation. In both projects, such outputs were even formalized as “Key Exploitable Results” intended to live beyond the project timeline—a conscious effort by project designers to ensure continuity (Urban Electric Mobility Initiative (UEMI), 2025; SESA, 2025).

Notably, SESA’s Living Labs approach encapsulated this philosophy: the project’s living labs were real-life test beds co-created with local stakeholders to ensure solutions were viable in context and could be refined collaboratively. By actively involving end-users and local providers in experimentation, these living labs helped bridge the gap between a successful trial and a scalable practice, because the necessary buy-in and local tweaks were addressed during the pilot itself. Thus, one lesson is that scaling up should not be an afterthought; it needs to be built into the DNA of pilot projects via strategic frameworks that guide how pilots are conceived, evaluated, and followed-through into broader implementation.

4.4 Advancing inclusion in urban transitions

A core insight from both projects is that inclusion is central to implementation success, not a secondary concern or a mere box to tick (Allen and Farber, 2020; Mirzoev et al., 2022). Sustainable mobility solutions in these cities will only take root if they account for and involve the majority of urban travelers—many of whom are in the informal sector or are otherwise marginalized (by gender, income, etc.). The research showed that when engaged through structured methods like the ABCD process, traditionally excluded actors (e.g., informal transit operators, women, youth) contributed practical and innovative ideas that improved both equity and effectiveness of solutions (Galuszka, 2021).