Abstract

Mitigating climate change has become increasingly critical in the context of accelerating urbanization and rising energy demand. The long-term goal of effective and sustainable urban energy planning is to develop practical strategies that ensure access to affordable energy while enhancing thermal comfort and urban livability. This paper presents a technical evaluation of the energy performance of a bifacial PV system installed on the roof of a warehouse located in a suburban area (near Lodz airport). The efficiency of the system is assessed in comparison to traditional PV panels. To investigate the potential gains from reflected solar radiation, a high-reflectance exterior roof coating was applied to half of the monitored roof surface, allowing for direct performance comparison between coated and uncoated surfaces. The applied reflective membrane, a flexible and UV-resistant coating, also serves to reduce roof surface temperatures and enhance PV efficiency. The influence of the reflective surface on energy yield was assessed with the historical records: the documented yield of the examined scenario is almost 10%. Rather than relying on numerical modeling, this work presents a real-world case study that demonstrates a good practice example for urban sustainability.

1 Introduction

The impacts of ongoing climate change are becoming increasingly evident, with prolonged heatwaves, as well as more frequent extreme weather events such as hurricanes, droughts, and floods (Calvin et al., 2023). These changes are largely caused by our development, most notably, the rapidly growing global population and the resulting surge in global energy demand, a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. The inevitable urbanization is transforming the traditional rural residency model, adding an additional element to the already complicated puzzle: how to mitigate climate change utilizing sustainable urban planning? It is expected that by 2050, almost 70% of the global population will reside in urban areas (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2019). This unprecedented urban growth underscores the critical need for novel adaptation policies and technological solutions for sustainable urban infrastructure and planning.

Urban areas encompass both densely built city centers and more loosely structured suburban zones. High-density urban environments often struggle with the low quality of local climate, characterized especially by high energy demand, poor air quality, and elevated ambient temperatures (Piracha and Chaudhary, 2022). Elevated temperatures are often linked to the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, which notably impacts energy consumption, air quality, and thermal comfort (Mohajerani et al., 2017). Although these challenges may be less evident in suburban areas outside the dense city centers, such zones offer valuable opportunities to pilot and deploy mitigation strategies at scale, particularly on large roof surfaces typical of warehouses and commercial buildings (Santamouris, 2020; Santamouris et al., 2015). Scalable solutions fitted to different urban zones, i.e., suburban areas, can support sustainable energy transitions across diverse city contexts, improving overall building- and community-scale energy efficiency (Guarino et al., 2025).

Among available interventions, rooftops are a critical interface where renewable energy generation and passive microclimate control can be implemented without competing for scarce ground-level space. A widely recognized way to improve the overall urban environmental quality is to reduce energy demand while maximizing the integration of clean energy sources (Kennedy et al., 2015). However, the deployment of renewable energy, particularly solar energy, remains challenging in high-density urban areas due to numerous constraints of architectural and urban design (Amado et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2020). In suburban settings, these constraints are often relaxed, enabling more favorable solar access and more cost-effective PV integration (Mohajeri et al., 2016). This greater spatial flexibility often makes solar installations not only more technically feasible but also more cost-effective. In light of increasing energy demand with urban development, accelerating the penetration of renewable energy sources is essential for the transition to a low-carbon urban future.

Material-based strategies provide a complementary pathway for advancing sustainable urban development. Reflective materials, especially coatings and membranes, are effective passive solutions in mitigating the UHI effect in both existing and new buildings (Santamouris et al., 2011). These surfaces are simple to implement, low-cost, and highly scalable, making them well-suited for widespread application in urban environments. The benefits of increased surface reflectivity, most notably significant reductions in ambient temperature, are well documented (Akbari and Matthews, 2012). For instance, increasing the albedo of pavement surfaces by a factor of 0.1 can reduce average air temperatures by approximately 1 K (Robinson et al., 2024). Even greater impacts can be achieved through the application of cool roofs. When reflective coating is implemented across multiple buildings, cool roofs enhance area-scale albedo increases, leading to measurable decreases in recorded air temperature at the neighborhood or cluster scale (Mohegh et al., 2018). Material-based solutions, reflective surfaces in particular, offer passive and effective means of addressing urban climate challenges.

Recent research has explored the integration of PV systems with green roofs as a promising multifunctional approach to sustainable building design. Studies demonstrate that combining vegetation with PV panels creates reciprocal benefits. The combination of PV and green roofs benefits both elements: the PVs are naturally cooled (lower operating temperature) due to the evapotranspiration, while panels provide beneficial partial shading for vegetation (Chemisana and Lamnatou, 2014). This synergy has been shown to increase PV power output by 1 to 6% compared to conventional roof installations. Furthermore, the thermal performance of PV systems is significantly influenced by underlying rooftop materials, impacting conversion efficiency (Al-Akam et al., 2024). These integrated approaches represent an evolution in sustainable roofing strategies, moving beyond single-purpose solutions toward systems that address multiple urban challenges simultaneously. From an environmental assessment perspective, life-cycle analysis indicates that although integration of PV with green roofs may introduce additional material impacts relative to simpler configurations, these impacts can be compensated over time when higher PV output is cumulated (Lamnatou and Chemisana, 2014). However, when implementing such systems, careful consideration must be given to site-specific factors, including climate conditions, building characteristics, and intended sustainability outcomes to optimize performance, rather than single-metric optimization (Dimond and Webb, 2017).

This article presents the results of a field study on a bifacial PV (bi-PV) system installed in a suburban area of Lodz, Poland. The overview includes a performance comparison between a conventional PV system and a more technologically advanced bifacial configuration, both mounted on the same warehouse rooftop. Additionally, the study evaluates the impact of a reflective roof membrane on PV system efficiency and roof temperatures. The combined application of both discussed solutions, bi-PV technology and reflective roof coatings, demonstrates a practical strategy that allows for mitigating some of the negative impacts associated with urban development.

2 Overview of the assessment

The main objective of this article is to present insights from a field investigation that might help improve the local urban environment through combined sustainable strategies. The research focuses on the integration of a bi-PV system and a high-reflectance membrane, both installed on the rooftop of a warehouse located in the suburban area of the second biggest city in Poland. To support a clearer understanding of the research context, this section provides background on key components of the assessment. A brief overview of the bi-PV technology, as well as cool roof coatings, is given. Finally, the overview of the examined case study is given.

2.1 Bifacial PV technology

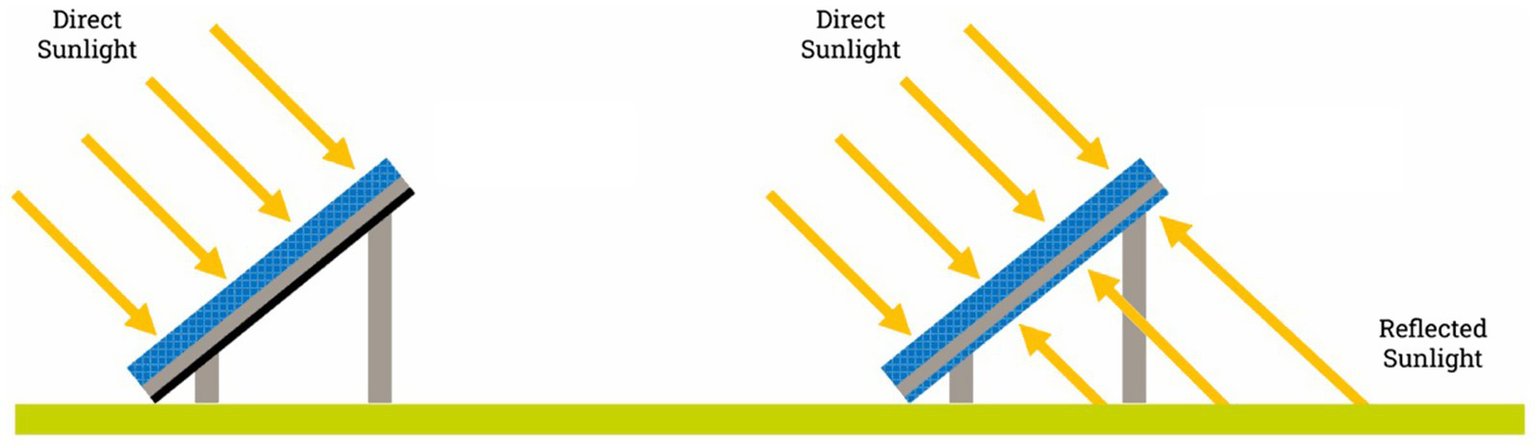

Solar energy can be utilized to harness heat or to use radiation to generate electricity. PV modules, composed of interconnected solar cells, generate electricity via the photovoltaic effect: an electric current produced when electrons are set in motion by sunlight exposure (Singh, 2013). Nowadays, PV systems are considered a cornerstone of the global energy transition, driven by rapid technology advancement and declining costs (Ali et al., 2025). There is a huge variety of available technologies of PV, among which bi-PV systems represent a significant advancement over traditional modules (Sun et al., 2018), enabling electricity generation from both the front and rear sides of a panel (see Figure 1). While monofacial panels generate electricity solely from their front surface, bifacial modules capture solar energy from both sides by collecting direct and diffuse radiation on the front surface while simultaneously utilizing reflected and scattered irradiance on the rear surface. According to Sun et al. (2018), under favorable conditions, bi-PVs are capable of up to 30% higher energy yield compared to conventional modules. A comprehensive overview of the bi-PV technology is provided by Guerrero-Lemus et al. (2016); technology of bifacial modules can surpass monofacial in market share as soon as the end of this decade (Deline et al., 2019).

Figure 1

Schematic comparison of irradiation yield by monofacial (on the left) and bifacial (on the right) PVs (Schematic Comparison of Mono- and Bi-facial PVs, n.d.).

In addition to standard factors affecting PV efficiency, such as technological advancement, the proper placement and tilt angle, or solar irradiance intensity, bi-PV systems are particularly sensitive to the reflective properties of the underlying surface (performance boost when installed above high-albedo surfaces). Regardless of PV technology, elevated operating temperatures negatively impact Regardless of PV technology and the corresponding energy output (Dubey et al., 2013). According to Cotfas et al. (2018), we can expect approx. 0.5% efficiency loss for every 1 K temperature rise in cell temperature. The temperature sensitivity, known as the so-called temperature coefficient (γP), is used in the power output equation defined as follows:

Where P(T) is the power output at the operating temperature [W], PSTC is the power output [W] at Standard Test Conditions (STC), γP is the temperature coefficient of power [%/oC], Tcell is the cell operating temperature [oC], and TSTC is the reference temperature at STC (25 °C). Given this relationship, no matter the technology used, it is critical to provide optimal operating temperatures for efficient PV operation. Specific thresholds and specs are typically provided by the manufacturer in technical datasheets.

For bi-PV solutions, it is also important to correctly assign the installation height (Wang et al., 2015). Based on Johnson and Manikandan (2023), the empirical model for an optimal design of bi-PV installation is influenced by multiple factors, including tilt angle, height, and underlying surface albedo. In practice, the initially assumed height can be adjusted post-installation to maximize system output. Additionally, the adequate spacing between the adjacent bi-PV modules is also critical to avoid the self-shading effect, which can significantly reduce rear-side irradiance. Finally, to maximize the rear-side illumination, the bi-PV installation should be ideally applied over the surface with high albedo, i.e., the surface with high-reflectance properties.

2.2 High-reflectance roof coating

To mitigate the UHI effect, the elevated temperatures commonly observed on various urban surfaces, particularly rooftops, should be addressed. Conventional roofing materials are typically characterized by low solar reflectance and high thermal emittance, leading to excessive heat absorption and elevated surface temperatures, consequently increasing cooling demands. Traditional rooftops can reach surface temperatures as high as 70 °C during summer, accelerating material degradation, magnifying the UHI effect, as well as negatively impacting the performance of rooftop-mounted HVAC and PV (Akbari and Konopacki, 2005; Rawat and Singh, 2022).

There are several strategies developed to address the rooftop overheating and mitigate its impact on urban microclimates. Green roofs provide thermal insulation and promote evapotranspiration, leading to lower surface temperatures. However, they are relatively expensive, and the required complex structure and maintenance should be considered (Shafique et al., 2018). Ventilated roof assemblies, promoting convective air flow beneath the roofing surface, can reduce heat accumulation and surface heat. Yet, these systems are design-intensive, as well as often expensive to implement and retrofit (Wang et al., 2024). In contrast, cool roof (cool-r) solutions, i.e., membranes or materials, represent a passive and cost-effective technique applicable to both existing and new buildings. These materials provide a high solar reflectance and thermal emissivity, thereby minimizing heat absorption, reducing surface temperatures, and improving indoor thermal comfort, especially during the summer. Notably, lower roof temperature due to the cool-r application is also highly profitable for PV performance (Dominguez et al., 2011). According to (Green et al., 2020), a significant peak surface temperature reduction can be obtained after applying the cool-r solution.

The effectiveness and practicality of cool-r applications are well documented in the literature and increasingly adopted in real-world settings (Ashtari et al., 2021; Park and Lee, 2022; Rawat and Singh, 2022). Both laboratory experiments and field studies have demonstrated the exceptional performance of high-reflectance materials in limiting extreme surface temperatures. Application of the high-reflectance materials on the roof surface can be even more effective if combined with PV systems, especially bi-PV modules. When applied to rooftops, these materials can significantly enhance the thermal environment and energy efficiency of buildings. The benefits are magnified when integrated with PV systems, especially bi-PV modules, as they can harness cooler, more reflective surfaces to boost energy yield.

2.3 Case study description

The primary objective of the performed analysis was to assess the impact of the cool-r solution on bi-PV performance as well as on the thermal behavior of the roof surface. As a secondary goal, a comparison between monofacial and bifacial PV systems under real-world operating conditions was examined. Field-based research of this nature is essential for informing the urban energy transition, particularly in the context of more sustainable, energy-efficient, and resident-friendly built environments.

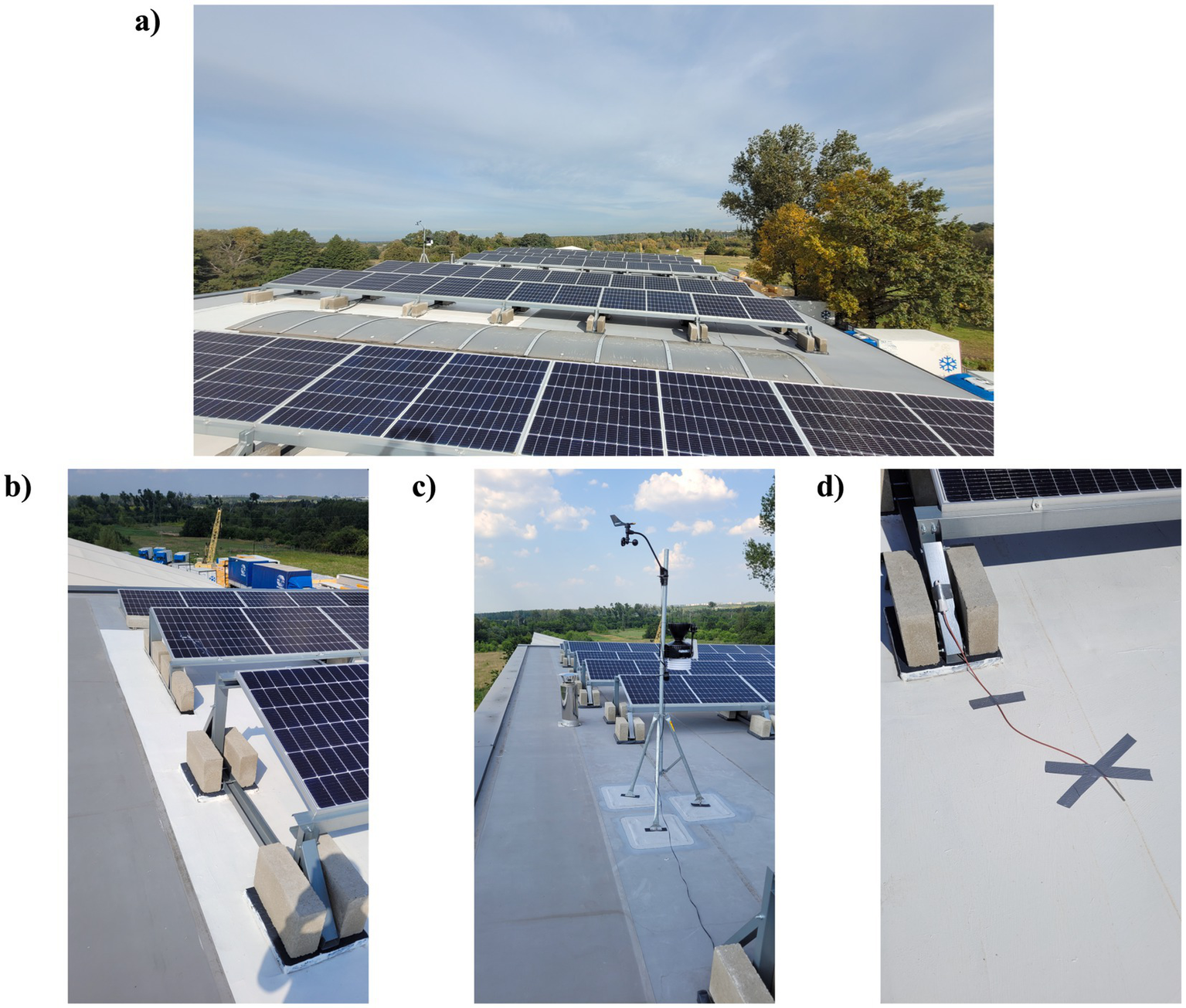

The experimental setup was installed on the rooftop of a warehouse, located in the suburban area of Lodz, Poland, approx. 10 km away from the city center and near the local airport. The rooftop has a flat, rectangular geometry (approximately 30 m × 15 m), with a slight eastward tilt, and was almost entirely available for PV installation (see Figure 2a). The roof is covered with a greyish waterproof single-ply thermoplastic membrane with a generally smooth surface, installed in overlapping sheets and sealed by hot-air welding. All the surrounding buildings were of similar height to the examined warehouse, eliminating the risk of shading from the nearby built environment. The full-scale monitoring was performed over 4 months, starting from 1st July to 31st October 2022. The examined solar system remains in continuous successful operation as of the time of writing.

Figure 2

The examined PV system installed on the warehouse rooftop: (a) Overview of the assembled setup with cool-R coating applied on the left half of the roof, (b) comparison of different mounting structures for PV modules, (c) used weather station, (d) exemplary application of thermocouple sensor on the rooftop.

In total, 54 south-facing PV panels were installed, arranged in 9 rows of 6 panels each; this layout ensured adequate spacing for maintenance access and minimized the risk of the self-shading effect. All the modules are tilted at a fixed angle of 15 degrees. The used bi-PV modules are n-type with an aluminum frame, with a peak power rating of 455 Wp and an efficiency of 20.9% under STC conditions. The bifaciality factor (ratio of rear and front power output) is 75%. According to the manufacturer, the modules are expected to preserve approx. 86% of their nominal efficiency after 30 years of operation.

The first row of PV modules (from the northern façade) was configured as a conventional monofacial system (see Figure 2b). The additional backing structure (closed structure with the total height of 8 cm) was provided to block reflected radiation, preventing the rear surface from contributing to power generation. The remaining 8 rows were installed as a bifacial system, using an elevated mounting structure, elevating panels above the roof surface. Initially, two different mounting structures were tested (see Figure 2b), particularly with the height of 34 cm (used for the 2nd row) and 46 cm (used for the remaining 7 rows). A third height of the mounting structure was introduced for the 4th row, starting from October 1st until the end of measurements; the PVs were elevated by an additional 12 cm, up to a total height of 58 cm above the roof surface. All the solutions used for the PV systems were checked and designed following the national structural safety regulations, including wind resistance criteria.

PV monitoring was provided by the SolarEdge platform (SolarEdge, n.d.), a widely adopted web-based application for, among others, solar systems performance tracking. The used platform provides a user-friendly GUI enabling transparent data access and a real-time system overview. It offers a data overview with both collective performance summaries and time series plots for individual modules. The monitoring in the examined system was configured by coupling two adjusted PVs together; thus, a data overview was performed for 3 PV doublets per row, enabling localized performance comparisons within the whole solar installation.

The impact of the high-reflective roof surface on the roof temperature, as well as the performance of the installed solar system, was assessed through the application of cool-r membrane (see Figure 2a). The selected coating was applied on the left half of the rooftop, excluding a strip from the northern edge (i.e., the 1st row of panels mimicking monofacial PV). The cool-r membrane was applied between 14 and 17 July; this short period is excluded from the analysis. The period before the application served as the baseline for both rooftop thermal conditions and PV system performance. The comprehensive comparison of cool-r effectiveness is documented for 15 weeks. The used material is a UV-resistant, liquid-applied waterproofing membrane with exceptional reflectance characteristics. It provides a high solar reflectance (0.84) and thermal emissivity (0.88), effectively mitigating rooftop temperatures and enhancing reflected irradiation. The used material is considered a cost-effective solution, with an approximate cost of 13 USD/m2. The selected coating was applied by certified professionals from the manufacturer, following thorough cleaning of the roof surface. The benefits of the applied membrane contribute to improving both energy and thermal performance.

To monitor temperatures on the roof surface, as well as beneath the operating bi-PV modules, the specialized thermocouples were used (see Figure 2d), provided by Aranet (n.d.). Four advanced sheathed temperature probes were used, wirelessly connected to the data logger with a web-based software provided by the same producer. The compact sensors are rated for protection against dust ingress and prolonged water immersion, enabling reliable performance under outdoor conditions. The sensors are capable of measuring temperatures in the range of -55 °C and 105 °C. The temperature data were recorded at 10-min intervals throughout the measurement period.

Finally, the local meteorological data were collected using a Davis weather station (Davis Instruments, n.d.). It was installed in the central part of the examined rooftop, near the left edge (see Figure 2c). The used professional weather station supports comprehensive climate monitoring, including measurements of air temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, wind speed and direction, UV-index, and solar radiation. Data acquisition and real-time climate monitoring were managed by the dedicated software called WeatherLink. Using real-time, site-specific weather data is critical for the accurate assessment of urban development strategies, with much higher reliability compared to the standard weather files, e.g., Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) files (Xu et al., 2022).

The described setup is used to assess the case-study effectiveness of bi-PV for urban environments under various scenarios. Based on the performed examination, a valuable insight into the synergistic benefits of high-reflectance coatings and bi-PV technology was provided. This integrated approach can support decision-making for energy-efficient and climate-responsive urban development.

3 Results

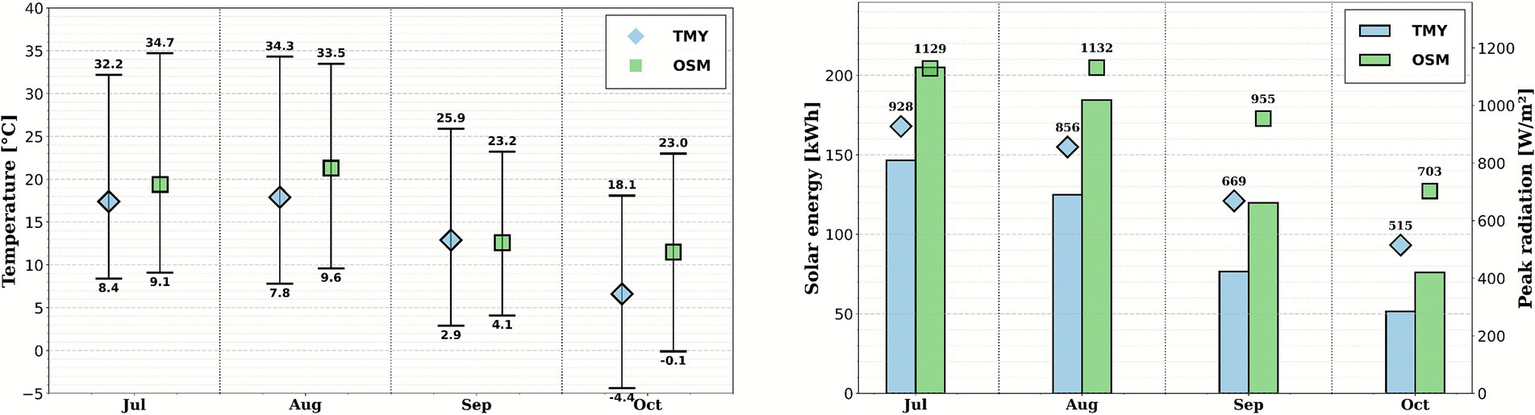

The exterior climate conditions are highly impactful on the effectiveness of the examined system, particularly the availability of solar irradiation and ambient air temperature. These two factors directly affect both energy yield potential and the thermal behavior of the rooftop and PV modules. The monitoring period was characterized by notably warmer and sunnier conditions compared to the TMY dataset (see Figure 3). The maximum air temperature recorded on-site was (34.7 °C) slightly higher than the TMY peak of 34.3 °C, while the minimum temperature was substantially higher (−0.1 °C compared to −4.4 °C). On average, the on-site measured air temperature during the monitoring period exceeded TMY data by 2.5 °C. Peak solar radiation reached 1,132 W/m2, which is higher by 204 W/m2 than the corresponding maximal record from TMY. The cumulative solar energy received over the examined 4 months totaled 585.1 kWh, representing an approx. 46% increase compared to the TMY records. These findings reflect ongoing climatic change, with the present local conditions varying substantially from historical records, i.e., the TMY data recorded between 1970 and 2005. The above-mentioned is evident not only in statistical summaries but also in the frequency and intensity of peak records.

Figure 3

The exterior climate overview highlights a comparison between TMY and on-site measurements (OSM) for air temperature (on the left) and solar radiation (on the right).

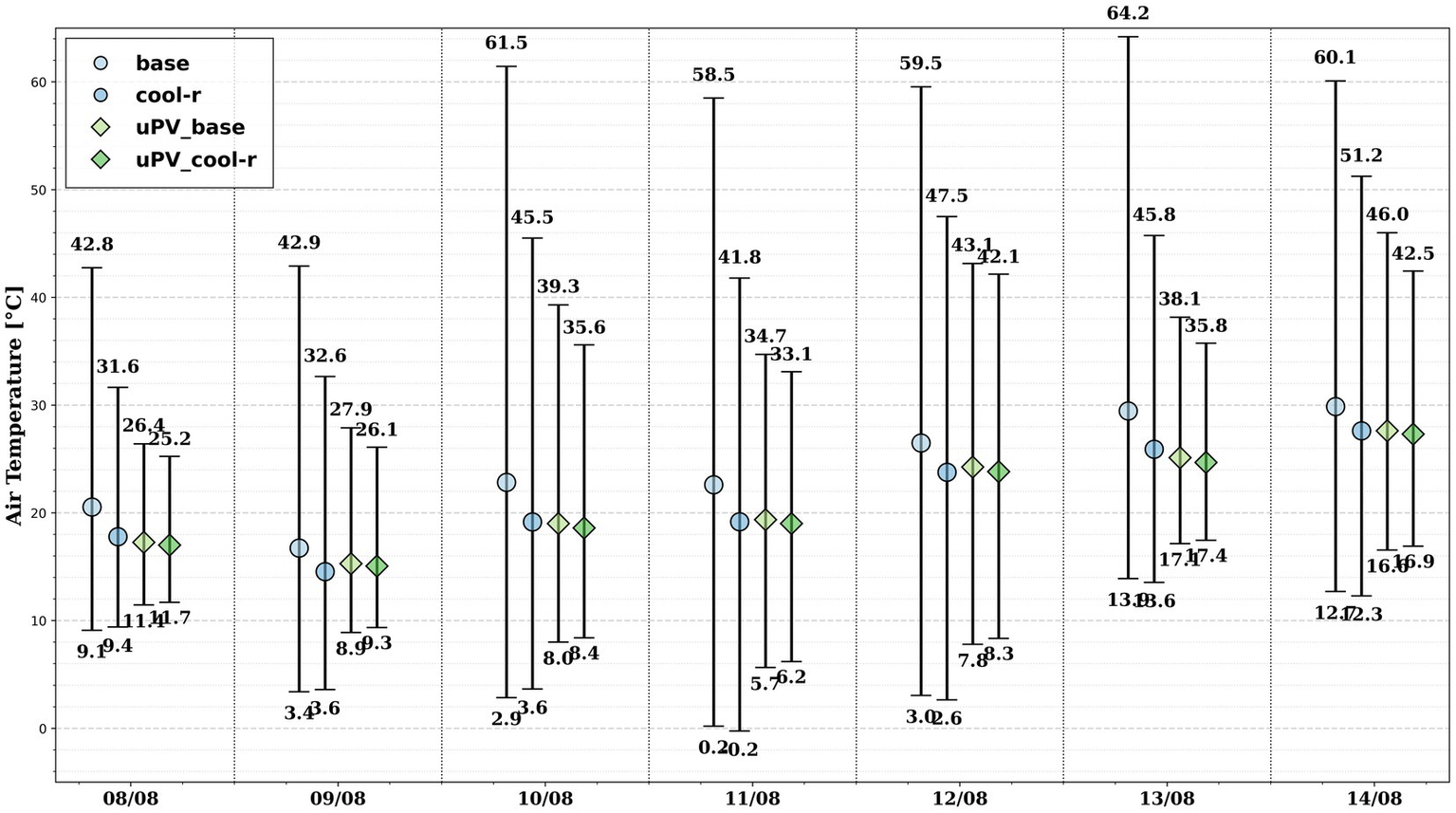

The temperature measurements were performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the cool-r membrane in reducing rooftop surface temperature, as well as the local thermal environment just beneath PV panels. Four thermocouple probes were used throughout the monitoring period, recording at 10-min frequencies, comparing opposite placements under several sensor assignment scenarios (see Figure 4). The first set of records was collected before the application of the cool-r membrane and used as a reference. During early July, the peak rooftop surface temperature reached 46.1 °C, while the highest temperature recorded beneath the PV module (with the sensor suspended freely under the panel) was 35.8 °C. During the reference period, temperature differences between sensors at opposing placements were minimal, within ±1.5 °C. The highest temperature recorded on the uncoated rooftop during the entire study was 64.2 °C.

Figure 4

The exemplary period (first 2 weeks of August) of recorded roof surface temperature under different conditions (exposure to sunlight) and positioning (cool-R or default side) on the examined rooftop.

After the application of the cool-r membrane, temperature comparisons between coated and uncoated (default) surfaces were analyzed. Under shadow conditions, the coated surface reached a maximum temperature of 31.5 °C compared to 42.4 °C on the uncoated side. The effectiveness of cool-r coating is particularly notable given that the peak temperature recorded under direct sun exposure was only 39.8 °C, which is significantly lower than the peak records for the uncoated surface in shade. In September, a notable contrast was recorded for temperatures in full sun exposure: 46.4 °C on the default surface versus 34.4 °C on the cool-r surface, displaying a 12 °C reduction. This trend continues later with the measurements, keeping the peak surface temperature reductions consistently in the range of 21–26%. The application of cool-r was proven to be effective in lowering the temperature underneath the PV modules. Recorded peak temperatures were 10–20% lower for panels above the cool-r coating, potentially boosting PV efficiency.

Finally, the effect of mounting height scenarios was assessed. For the lowest structure with a height of 34 cm (2nd row), the peak temperature above the uncoated surface was approx. 5 °C higher than for the 46 cm scenario (3rd row, also considered as a common structure). Simultaneously, when cool-r coating was applied, the recorded difference is only 1 °C. The highest elevation tested, with a total height of 58 cm (4th row), showed negligible temperature differences relative to the common configuration, regardless of surface finish below. These findings suggest that beyond a certain mounting height of PV, convective airflow becomes the dominant cooling mechanism, reducing the influence of roof surface temperature.

The PV assessment focused on two main objectives: to check the effectiveness of the cool-r surface on the energy field, as well as to compare different PV system configurations. For accurate evaluation of the impact of roof surface reflectivity, the outputs of two adjacent panels located on the opposite sides of the roof were compared; the left (western) side of the roof (with cool-r) was compared with the right (eastern) side (default surface). The analysis excluded the central two panels to avoid edge effects and due to the configuration of the monitoring software used, as described in subsection 2.3 (hourly records are used). The cool-r side produced on average 9.2% more electricity compared to the opposite side. In contrast, during the reference period (i.e., before cool-r application), the difference in yield was negligible (lower than 1%), confirming the effectiveness of the high-reflectance surface used.

The second mounting structure (the common structure, used for 6 rows in total), with a height of 46 cm, was proven to be the most effective in terms of electricity generation. Comparing to the lowest structure (34 cm, in the 2nd row), the electricity production was higher by an average of 6 and 5%, respectively, for cool-r and default sides. The advantage of the common mounting structure was particularly pronounced during periods of lower solar irradiance. The tallest configuration (58 cm, applied to the 4th row) was almost as effective as the common one, yielding only about 1% less energy regardless of the underlying surface.

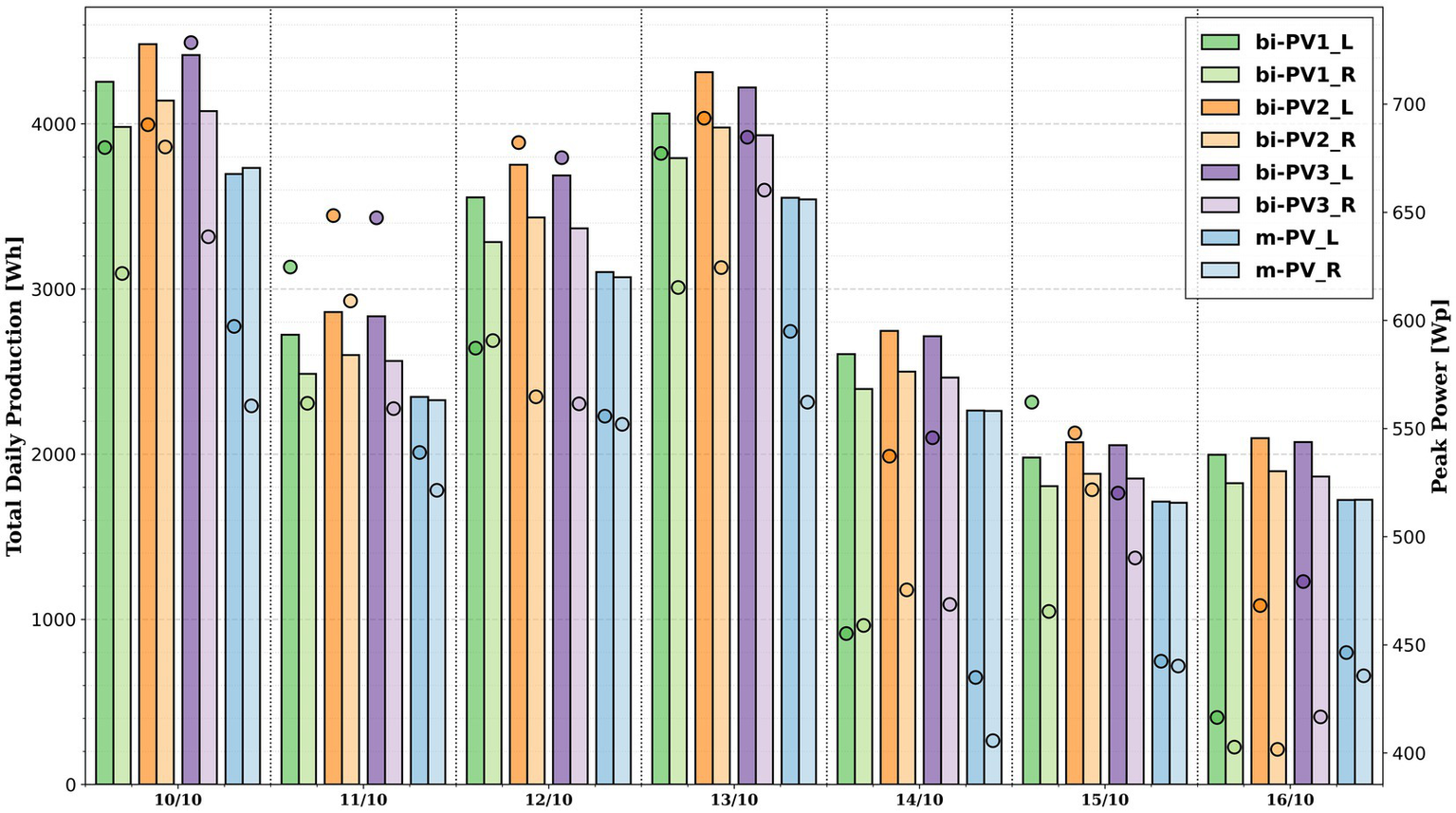

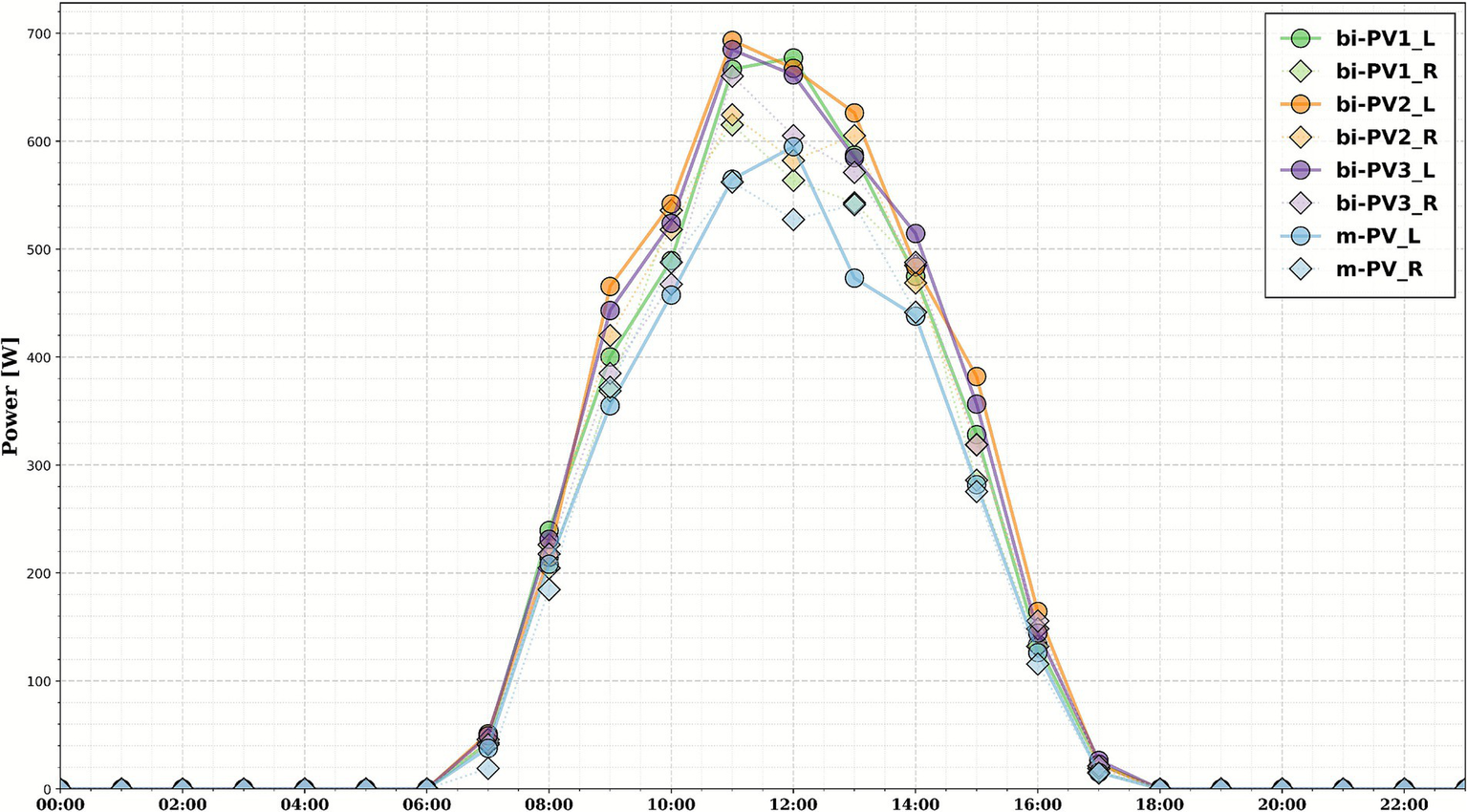

Finally, the 1st row of PVs (configured as monofacial) was compared to all bifacial configurations (see Figure 5); up to 22% more electricity per month was produced, demonstrating the clear advantage of bifacial technology under the studied conditions. The exemplary time series on PV generation during the day is shown in Figure 6. The labels used on both plots indicate the examined PV setup, as follows: L or R suffix indicates the placement on the roof, in particular left or right side (as it was explained in subsection 2.3); bi or m prefix indicates the type of PV used, in particular bi-facial or mono-facial; the numbering for bi-PV indicates the type of mounting structures, where 1 (2nd row) is the 34 cm, 2 is the 46 cm (3rd row, also considered as a common structure), and 3 (4th row) is 58 cm.

Figure 5

Comparison of PV solutions for an exemplary week in October (between 10th and 16th) in terms of peak performance, as well as daily generations; data shows records for two panels jointly, on the left (cool-R side, designated as L) and on the right (default side, designated as R) roof sides.

Figure 6

Time series of PV generation for 13th October, comparing all the examined PV solutions on both sides of the rooftop.

The performance of each scenario was addressed day by day (for the same period as in Figure 5), as shown in Tables 1, 2. Based on the representative overview in Table 1, we can see the advancement of bi-PV compared to the traditional panels for the common structure: the recorded yield is about 11% higher for the right side of the roof, and about 21% for the left one (with cool-r coating). The common structure (PV2) is also more effective than the lower structure (PV1) in the range of 4.74–6.16% for the cool-r side and 3.96–4.87% for the base coating. It shows the benefit of the default height of the structure, as well as proving the effectiveness of the applied cool-r coating. Comparing the PV2 structure with the highest examined (PV3), the common structure is still more effective, however, less visible. Similar differences were observed for both sides of the roof: a range of 1.17–1.94% for the right side and 0.88–2.20% for the left side with cool-r coating.

Table 1

| L (cool-r) | R (base) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV vs. PV2 | PV2 vs. PV1 | PV2 vs. PV3 | PV vs. PV2 | PV2 vs. PV1 | PV2 vs. PV3 | |

| 10/10 | 20.06 | 5.37 | 1.49 | 12.02 | 4.01 | 1.55 |

| 11/10 | 21.87 | 5.03 | 0.90 | 11.77 | 4.60 | 1.38 |

| 12/10 | 20.92 | 5.56 | 1.76 | 11.76 | 4.51 | 1.94 |

| 13/10 | 21.40 | 6.17 | 2.20 | 12.28 | 4.87 | 1.17 |

| 14/10 | 21.29 | 5.37 | 1.17 | 10.53 | 4.37 | 1.46 |

| 15/10 | 20.98 | 4.74 | 0.88 | 10.25 | 4.15 | 1.54 |

| 16/10 | 21.70 | 5.05 | 1.16 | 10.05 | 3.96 | 1.76 |

Cumulative comparison between the examined PV solutions (in %) for the representative week in October.

Table 2

| M-PV_L | m-PV_R | bi-PV1_L | bi-PV1_R | bi-PV2_L | bi-PV2_R | bi-PV3_L | bi-PV3_R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10/10 | 3,734 (1.01%) | 3,697 | 4,255 (6.86%) | 3,981 | 4,483 (8.26%) | 4,141 | 4,417 (8.32%) | 4,078 |

| 11/10 | 2,347 (0.87%) | 2,327 | 2,723 (9.53%) | 2,486 | 2,860 (9.99%) | 2,601 | 2,835 (10.52%) | 2,565 |

| 12/10 | 3,103 (1.02%) | 3,072 | 3,555 (8.22%) | 3,285 | 3,753 (9.30%) | 3,433 | 3,688 (9.49%) | 3,368 |

| 13/10 | 3,553 (0.29%) | 3,543 | 4,063 (7.11%) | 3,793 | 4,314 (8.44%) | 3,978 | 4,221 (7.35%) | 3,932 |

| 14/10 | 2,265 (0.12%) | 2,262 | 2,607 (8.82%) | 2,395 | 2,747 (9.86%) | 2,500 | 2,715 (10.18%) | 2,464 |

| 15/10 | 1714 (0.41%) | 1,707 | 1,979 (9.56%) | 1,807 | 2,073 (10.18%) | 1,882 | 2,055 (10.90%) | 1,853 |

| 16/10 | 1724 (−0.03%) | 1,724 | 1,997 (9.41%) | 1,825 | 2,098 (10.55%) | 1,897 | 2,074 (11.21%) | 1,865 |

Comparison of the performance for the examined PV solutions for the representative week in October (production in Wh).

Table 2 shows a comparison between the yield for the left and right sides for each scenario examined. As expected, there is no noteworthy difference in the positioning of the mono-facial PVs: the difference stays within 1%. For all the bi-facial PVs, the side with the cool-r coating is significantly more efficient. Structure type 1 has the lowest improvement of the produced energy, while structures 2 and 3 are comparable. For the best day (the one with the highest daily production), the recorded differences are 6.86, 8.26, and 8.32% respectively, for PV1, PV2, and PV3, while for the worst day (the one with the lowest daily production), the outputs are 9.56, 10.18, and 10.90%.

Lastly, it is worth highlighting that the installed PV system fully covers the demand of the examined warehouse. The total operational demand consists not only of the warehouse itself but also includes two adjacent office buildings located on the same parcel. During the examined period, the whole installation produced nearly 12,500 kWh of electricity, among which approx. 15% was self-consumed. All the remaining surplus production was exported to the grid under a net-metering agreement, yet no further details on export pricing or compensation were shared.

4 Discussion

In Europe, the mean annual temperature has already increased by approx. 1.8 °C, relative to the pre-industrial period, with recent years ranking among the warmest years on record (World Meteorological Organization, n.d.). This trend is also evident in the present case study, where on-site measurements recorded an average air temperature higher by 2.5 °C compared to the TMY data, established based on records from 1970 to 2005. Climate change is further reflected in the observed increase in solar radiation, but this parameter exhibits greater year-to-year variability, influenced by, e.g., sunshine hours.

Given the above-mentioned, the traditional European approach to building design, which particularly focuses on cold-weather protection, must adapt to the rising global temperature. Design strategies should increasingly incorporate solutions that prevent heat mitigation and overheating. Addressing these challenges requires an understanding of the mechanisms that contribute to indoor overheating and its corresponding impacts on occupants and energy demand. Among these mechanisms, the UHI effect plays a prominent role, intensifying temperatures in urban areas. Changes to the housing stock are necessary, both in retrofitting existing dwellings and in more stringent regulations for new buildings, to support the mitigation of the UHI effect and reduce overheating risk (Taylor et al., 2023).

This case study evaluated bi-PV technology and high-reflectance roof coating as complementary strategies for sustainable urban development that might be helpful for UHI mitigation. The analysis focused on two main aspects: the potential increase in electricity yield as well as the reduction of roof surface temperature. All the provided comments are based on the outputs collected from 1st July to 31st October 2022.

The cool-r coating proved highly effective in lowering the roof surface temperatures, with recorded reduction as high as almost 18.4 °C, keeping the temperature drop in the range of 21–26%. Even more impressive, the temperature of the cool-r surface recorded in direct sunlight was often lower than the temperature of the shaded (under PV) uncoated surface. The applied coating also reduced temperatures beneath elevated PV modules, yet this cooling effect diminished with increasing installation height. It is therefore concluded that the strongest impact of the surface temperature reduction was observed for a mounting height of 34 cm, while at 46 cm and 58 cm, the influence of the underlying surface temperature was minimal: no significant difference between those two structures was noticed.

The high reflectance of the cool-r membrane also enhanced the rear-side utilization of the bi-PV modules; based on the analyzed period, an expected increase of almost 10% in the electricity yield is expected compared to the uncoated side. The correlation of electricity generation with the mounting height of bi-PV was also pointed out. The supporting structure of 46 cm was found optimal, producing 3.5 and 2.2% more electricity compared to 34 cm and 58 cm configurations, respectively. Overall, the bi-PV system outperformed the monofacial reference array by 12% on average.

The current challenges of climate change and the ongoing energy crisis have forced us to progressively shift toward clean, reliable, and sustainable energy sources. Combining the application of high-reflectance roof coatings with the usage of bi-PV systems can increase electricity generation by up to 16%. This solution also leads to a reduction of surface temperatures and supports building-level energy autonomy in suburban contexts. These findings underscore the synergistic benefits of integrating active (bi-PV systems) and passive (high-reflectance roof coatings) techniques to not only enhance building energy efficiency but also support building-level energy autonomy in urban contexts and climate resilience.

This paper is intentionally framed as a practice-oriented field case study reporting system-level, real-site performance of bi-PV above a high-reflectance roof coating, rather than a full mechanistic attribution study. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as evidence of achievable operational outcomes (i.e., net energy yield and observed thermal response) under realistic conditions. Several factors are important for broader interpreting and guiding future works. Although the cool-roof membrane properties are provided as certified technical specifications, effective in-situ reflectance and emissivity may vary with aging, soiling, moisture, and spectral effects. A rigorous validation would require on-site measurements of incident and reflected shortwave radiation, as well as incident and emitted longwave radiation. Likewise, the reported energy gain is based on aggregate production; a more detailed bifacial assessment would require separate monitoring of front- and rear-side irradiance. Finally, the modest effect of installation height likely reflects coupled convective and radiative processes on the module rear side, where airflow stagnation, longwave exchange, and mutual reflections can be significant. Targeted computational assessment could be carried out to quantify these mechanisms and support a more robust temperature-power interpretation. In this context, a front/back heat-balance model, supported by dedicated irradiance and thermal measurements, including cell temperature, is anticipated.

The cool-r roof membranes allow for managing the indoor temperature better by lowering the roof surface temperature. By lowering roof surface temperatures, such coatings can reduce cooling loads and enable more efficient HVAC (heating, ventilation, air conditioning) operation, particularly for AHU (air handling units), typically installed on the rooftops (Green et al., 2020). Compared to comprehensive building retrofits, light-colored, high-albedo membranes offer a cost-effective and minimally invasive strategy for urban heat mitigation. The optimal operation of the active cooling systems is also critical due to the corresponding waste heat from AC operation that can exacerbate the UHI effect (Salamanca et al., 2014).

The impacts of UHI are most pronounced in dense urban areas, yet are also evident, to a lesser degree, in suburban areas, as discussed in this study. Given ongoing urbanization, today’s suburban zones might evolve into high-density city centers in the upcoming years, making early adoption of mitigation strategies both relevant and cost-effective.

Finally, the building owner confirmed that the applied measures were fully profitable. The whole roof was covered with the cool-r coating in the upcoming spring following the measurements. At the time of research finalization, the additional expansion of bi-PV installation was under consideration. These results, derived from a real-world field assessment, provide actionable evidence for policymakers and practitioners to integrate proven, scalable solutions into sustainable urban planning frameworks.

5 Conclusion

Rapid urbanization and rising energy demands underscore the urgency for effective energy transition. This study presents a technical evaluation of a real-world bi-PV system installed on a suburban warehouse roof, combined with the application of a high-reflectance (cool-r) roof coating. Both examined approaches demonstrated substantial potential for optimizing rooftop surfaces to improve solar systems’ performance. Together, they support effective energy transition and can contribute to UHI mitigation, enhancing the local urban climate. Urban areas, as major contributors to global energy consumption and carbon emissions (International Energy Agency (IEA), 2024), hold highly promising potential for scalable climate change mitigation strategies.

Effective integration of such solutions requires broader urban planning and supportive policy frameworks. This work offers practical, field-based evidence that complements theoretical modeling, providing a transferable good-practice example for reasonable urban applications. The findings indicate that the most effective approach is a simultaneous integration of reflective roofing with bi-PV systems. The performed field measurements confirmed that such an approach can increase PV electricity yield by up to 16%, simultaneously reducing rooftop surface temperatures by over 20%, thereby improving HVAC efficiency. Beyond the technical advances, the examined solution aligns with broader climate and decarbonization targets, contributing to sustainable urban development. This strategy is not only cost-effective, but it also enhances building-level energy performance and reduces UHI intensity. As urban areas continue to expand and transform, adopting combined passive–active strategies will be critical for shaping healthier, more energy-efficient built environments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MZ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Akbari H. Konopacki S. (2005). Calculating energy-saving potentials of heat-island reduction strategies. Energy Policy33, 721–756. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2003.10.001

2

Akbari H. Matthews H. D. (2012). Global cooling updates: reflective roofs and pavements. Energ. Buildings55, 2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.02.055

3

Al-Akam A. Abduljabbar A. A. Abdulhamed A. J. (2024). Impact of different rooftop coverings on photovoltaic panel temperature. Energy Eng.121, 3761–3777. doi: 10.32604/ee.2024.055198

4

Ali A. O. Elgohr A. T. El-Mahdy M. H. Zohir H. M. Emam A. Z. Mostafa M. G. et al . (2025). Advancements in photovoltaic technology: a comprehensive review of recent advances and future prospects. Energy Conver. Manage. X26:100952. doi: 10.1016/j.ecmx.2025.100952

5

Amado M. Poggi F. Amado A. R. (2016). Energy efficient city: a model for urban planning. Sustain. Cities Soc.26, 476–485. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2016.04.011

6

Aranet (n.d.). (homepge) (Website). Aranet, Riga, Latvia. Availabe at: https://www.aranet.com/en/home

7

Ashtari B. Yeganeh M. Bemanian M. Vojdani Fakhr B. (2021). A conceptual review of the potential of cool roofs as an effective passive solar technique: elaboration of benefits and drawbacks. Front. Energy Res.9:738182. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2021.738182

8

Calvin K. Dasgupta D. Krinner G. Mukherji A. Thorne P. W. Trisos C. et al . (2023). “IPCC, 2023: Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change” in IPCC. eds. Core Writing Team, LeeH.RomeroJ. (Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)).

9

Chemisana D. Lamnatou C. (2014). Photovoltaic-green roofs: an experimental evaluation of system performance. Appl. Energy119, 246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.12.027

10

Cotfas D. T. Cotfas P. A. Machidon O. M. (2018). Study of temperature coefficients for parameters of photovoltaic cells. Int. J. Photoenergy2018, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2018/5945602

11

Davis Instruments . (n.d.). Davis instruments (homepage) (website). Davis Instruments Corp., Hayward, CA, United States. Available at: https://www.davisinstruments.com

12

Deline C. Peláez S.A. Marion B. Sekulic B. Woodhouse M. Stein J. , (2019). Bifacial PV system performance: separating fact from fiction. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.23189.27365

13

Dimond K. Webb A. (2017). Sustainable roof selection: environmental and contextual factors to be considered in choosing a vegetated roof or rooftop solar photovoltaic system. Sustain. Cities Soc.35, 241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2017.08.015

14

Dominguez A. Kleissl J. Luvall J. C. (2011). Effects of solar photovoltaic panels on roof heat transfer. Sol. Energy85, 2244–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2011.06.010

15

Dubey S. Sarvaiya J. N. Seshadri B. (2013). Temperature dependent photovoltaic (PV) efficiency and its effect on PV production in the world – a review. Energy Procedia33, 311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2013.05.072

16

Green A. Ledo Gomis L. Paolini R. Haddad S. Kokogiannakis G. Cooper P. et al . (2020). Above-roof air temperature effects on HVAC and cool roof performance: experiments and development of a predictive model. Energ. Buildings222:110071. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110071

17

Green Roof Picture , (n.d.). Green roof (photograph). Retrieved from Google Images. (Accessed 02 September 2025).

18

Guarino S. Lo Brano V. Kosny J. (2025). Understanding the transformative potential of solar thermal technology for urban sustainability. Front. Sustain. Cities7:1583316. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1583316

19

Guerrero-Lemus R. Vega R. Kim T. Kimm A. Shephard L. E. (2016). Bifacial solar photovoltaics – a technology review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.60, 1533–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.03.041

20

International Energy Agency (IEA) (2024). World energy outlook 2024. Paris: IEA.

21

Johnson J. Manikandan S. (2023). Experimental study and model development of bifacial photovoltaic power plants for Indian climatic zones. Energy284:128693. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2023.128693

22

Kennedy C. A. Stewart I. Facchini A. Cersosimo I. Mele R. Chen B. et al . (2015). Energy and material flows of megacities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.112, 5985–5990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504315112,

23

Lamnatou C. Chemisana D. (2014). Photovoltaic-green roofs: a life cycle assessment approach with emphasis on warm months of Mediterranean climate. J. Clean. Prod.72, 57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.03.006

24

Mohajerani A. Bakaric J. Jeffrey-Bailey T. (2017). The urban heat island effect, its causes, and mitigation, with reference to the thermal properties of asphalt concrete. J. Environ. Manag.197, 522–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.03.095,

25

Mohajeri N. Upadhyay G. Gudmundsson A. Assouline D. Kämpf J. Scartezzini J.-L. (2016). Effects of urban compactness on solar energy potential. Renew. Energy93, 469–482. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2016.02.053

26

Mohegh A. Levinson R. Taha H. Gilbert H. Zhang J. Li Y. et al . (2018). Observational evidence of neighborhood scale reductions in air temperature associated with increases in roof albedo. Climate6:98. doi: 10.3390/cli6040098

27

Park J. Lee S. (2022). Effects of a cool roof system on the mitigation of building temperature: empirical evidence from a field experiment. Sustainability14:4843. doi: 10.3390/su14084843

28

Peng J. Yan J. Zhai Z. Markides C. N. Lee E. S. Eicker U. et al . (2020). Solar energy integration in buildings. Appl. Energy264:114740. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114740

29

Piracha A. Chaudhary M. T. (2022). Urban air pollution, urban heat island and human health: a review of the literature. Sustainability14:9234. doi: 10.3390/su14159234

30

Robinson A. Samuel F. Hong T. Lee Sang H. Levinson R. Piett Mary A. (2024). Potential urban Heat Island countermeasures and building energy efficiency improvements in Los Angeles County.

31

Rawat M. Singh R. N. (2022). A study on the comparative review of cool roof thermal performance in various regions. Energy Built Environ.3, 327–347. doi: 10.1016/j.enbenv.2021.03.001

32

Salamanca F. Georgescu M. Mahalov A. Moustaoui M. Wang M. (2014). Anthropogenic heating of the urban environment due to air conditioning. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres119, 5949–5965. doi: 10.1002/2013JD021225

33

Santamouris M. (2020). Recent progress on urban overheating and heat island research. Integrated assessment of the energy, environmental, vulnerability and health impact. Synergies with the global climate change. Energ. Buildings207:109482. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109482

34

Santamouris M. Cartalis C. Synnefa A. Kolokotsa D. (2015). On the impact of urban heat island and global warming on the power demand and electricity consumption of buildings—a review. Energ. Buildings98, 119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.09.052

35

Santamouris M. Synnefa A. Karlessi T. (2011). Using advanced cool materials in the urban built environment to mitigate heat islands and improve thermal comfort conditions. Sol. Energy85, 3085–3102. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2010.12.023

36

Schematic Comparison of Mono- and Bi-facial PVs . (n.d.).

37

Shafique M. Kim R. Rafiq M. (2018). Green roof benefits, opportunities and challenges – a review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev.90, 757–773. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.006

38

Singh G. K. (2013). Solar power generation by PV (photovoltaic) technology: a review. Energy53, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2013.02.057

39

SolarEdge (n.d.). SolarEdge (homepage). SolarEdge Technologies Ltd., Herzliya, Israel. Available at: https://www.solaredge.com/en

40

Sun X. Khan M. R. Deline C. Alam M. A. (2018). Optimization and performance of bifacial solar modules: a global perspective. Appl. Energy212, 1601–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.041

41

Taylor J. McLeod R. Petrou G. Hopfe C. Mavrogianni A. Castaño-Rosa R. et al . (2023). Ten questions concerning residential overheating in central and northern Europe. Build. Environ.234:110154. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110154

42

TPO Roof Membrane – Picture . (n.d.). TPO roof membrane / cool roof (photograph). Retrieved from Google Images (Accessed 02 September 2025)

43

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World urbanization prospects 2018: Highlights (no. ST/ESA/SER.A/421). United Nations, New York, NY, United States. Available at: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/

44

Wang H. Chen Y. Guo C. Zhou H. Yang L. (2024). Study on optimal layout and design parameters of ventilated roof for improving building roof thermal performances. Energ. Buildings320:114576. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114576

45

Wang S. Wilkie O. Lam J. Steeman R. Zhang W. Khoo K. S. et al . (2015). Bifacial photovoltaic systems energy yield modelling. Energy Procedia77, 428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.060

46

World Meteorological Organization (n.d.). World Meteorological Organization (website). World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Availabe at: https://wmo.int/

47

Xu L. Tong S. He W. Zhu W. Mei S. Cao K. et al . (2022). Better understanding on impact of microclimate information on building energy modelling performance for urban resilience. Sustain. Cities Soc.80:103775. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2022.103775

Summary

Keywords

bifacial PV, high-reflectance roof coating, sustainable urban development, urban energy efficiency, urban energy transition

Citation

Zygmunt M (2026) Enhancing sustainable urban development by combined application of bifacial PV and a high-reflectance roof coating: a case study. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1709168. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1709168

Received

19 September 2025

Revised

15 December 2025

Accepted

18 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Chin Haw Lim, Taylor's University, Malaysia

Reviewed by

Maria Matheou, University of Stuttgart, Germany

Aws Al-Akam, University of Babylon, Iraq

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zygmunt.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcin Zygmunt, marcin.zygmunt@kuleuven.be; marcin.zygmunt@p.lodz.pl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.