Abstract

Urbanisation is leading to an increase in outdoor lighting technologies in cities, which can disrupt wildlife habitats in urban greenery and alter their natural biological, physiological, and behavioural rhythms. Despite the flexibility of LED lighting technology, it is not being used effectively in practise to minimise ecological disturbances while providing sufficient illumination for people. A PRISMA review of 31 papers on lighting using contemporary LED sources and wildlife species revealed that lighting parameters were inadequately described to (1) characterise the relationship between assessed ecological impacts and light properties and (2) adjust properties of contemporary lighting technologies to reduce such impacts on animals. The authors suggest strengthening interdisciplinary collaborations for informed sustainable development by establishing common procedures and methods to ensure the transferability of research outcomes to practical applications.

1 Introduction

Artificial light at night (ALAN), an outcome of urbanisation, alters natural light and dark conditions in cities and beyond (Gaston et al., 2015; Bara and Falchi, 2023). Light pollution includes glare, light trespass, skyglow, and over-illumination; and outdoor electric lighting of an urban area can result in skyglow that extends hundreds of kilometres, impacting night skies and ecosystems (Jägerbrand and Spoelstra, 2023; Zielińska-Dabkowska et al., 2020; Kocifaj et al., 2023). Skyglow affects 23% of the global land area (Falchi et al., 2016), and is intensified by atmospheric conditions, such as weather (particularly clouds and snow) (Gaston et al., 2015; Jechow and Hölker, 2019; Rozman Cafuta, 2021). For example, sky brightness can increase by up to 10 times in entirely overcast conditions compared to clear skies (Kyba et al., 2012). Local light trespass can affect wildlife at distances of 10 to 50 m from the light source (Azam et al., 2018).

“Ecological” light pollution specifically refers to the modified natural light–dark cycles for non-human species (Longcore and Rich, 2004) whose biology evolved in synchrony with these cycles (Bradshaw and Holzapfel, 2010).

Beyond altering the visual character of built and natural environments, light exposure triggers diverse physiological and behavioural responses in humans and wildlife. In particular, electric lighting can alter circadian rhythms, hormonal cycles (Seebacher, 2022; Cabrera-Cruz et al., 2018), reproductive systems (Dominoni et al., 2013; Kempenaers et al., 2010), disease susceptibility (Dominoni et al., 2013; Ouyang et al., 2017), and orientation during flight (Cabrera-Cruz et al., 2018). Nocturnal species are particularly vulnerable, as darkness offers protection and foraging advantages. Electric lighting can heighten predation risk (McMunn et al., 2019; Barrientos et al., 2023; Ditmer et al., 2020) and attract species (e.g., insects) to hazardous areas (Gaston et al., 2013). Disrupted natural light regimes may impair life history traits and individual fitness, with cascading effects on community interactions (Dominoni et al., 2016) and broader ecological dynamics (Cieraad et al., 2022). Despite this, ecosystem-level consequences of light pollution remain underexplored (Hölker et al., 2021; Hirt et al., 2023).

Cities retain significant biodiversity within urban green spaces (Aronson et al., 2014), however, urban expansion and increased ALAN threaten these ecosystems (Seto et al., 2012). Limiting electric lighting, particularly in natural zones could mitigate species loss. The recent habitat restoration law in Europe highlights shifting from the current lighting practises by stating, “Member States should be able to consider to stop, reduce and remediate light pollution in all ecosystems” (Habitat Restoration, 2024). Humans have implemented lighting to provide security and safety during commuting, recreation, and socialisation (Boyce, 2019). Recently, there has been a larger focus in the Convention on Biodiversity (target 12.4) (Convention Biological Diversity, 2022) on conserving and restoring species biodiversity alongside ensuring human well-being.

One way to support biodiversity conservation and advance sustainable planning is to adapt new lighting technologies based on the identification and localisation of species. The transition to LEDs in recent decades has altered the character of after-dark environments, natural habitats and species interactions (Longcore and Rich, 2004; Gaston et al., 2013; Pawson and Bader, 2014; Perez Vega et al., 2022). Some ecological effects have been documented, however, little attention has been given to LED characteristics and to how they are defined and measured outside the specialised lighting community, hindering comparability and translation of findings into practise.

“Light” is defined as the range of wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum that are visible to humans (CIE, 2020). Electromagnetic radiation, however, includes a wide range of wavelengths beyond what humans can see (Schreuder, 2008), including ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR), which are perceived by species other than humans.

Commercial white LEDs typically have a peak in short-wavelength radiation (blue-appearing light in the wavelength region between 440 and 490 nm). Short-wavelength light especially contributes to increasing skyglow and affects the visual and non-visual mechanisms of species (Illuminating Engineering Society, 2023a). Broad-spectrum lighting (encompassing most or all wavelengths of the visible spectrum, 380 nm–740 nm) is favourable for supporting the overall vision of some organisms, while it might be disadvantageous for others due to exacerbating predator–prey relations (Dominoni et al., 2016; Rich and Longcore, 2006). LEDs can be dimmed by rapidly turning off and on, causing temporal light modulations (TLM), commonly called flicker (Lindén and Dam-Hansen, 2022). This temporal variation can be fast and invisible to most species; still, it may present visual and non-visual challenges (e.g., stress, eyestrain, and headaches in humans) (Abelson et al., 2023; Inger et al., 2014) especially for sensitive individuals (Miller et al., 2023). In contrast, daylight and some older technologies do not exhibit flicker.

Within state-of-the-art lighting design research, anticipating animal responses at a community ecology scale is limited due to a lack of integrated knowledge. While LED technology offers potentials for customisability, further studies are needed to test lighting parameters across seasons, geographical locations and species. Such research could improve the evaluation of ecosystem-level effects (Gaston et al., 2013; Hirt et al., 2023) and guide future use of LEDs to mitigate ecological impacts of electric lighting.

Pedestrian lighting systems are the main sources of light trespass in urban parks. Two lighting metrics often used to characterise pedestrian outdoor lighting are horizontal and vertical illuminance, estimating the amount of light projected on a surface (measured in lx) (Schreuder, 2008). The other is correlated colour temperature (CCT), describing the colour appearance of warm-cool white light sources defined in Kelvin (K) (Schreuder, 2008). They serve as guidelines based on visual performance criteria for different outdoor settings (European Committee for Standardization, 2016; Trafikverket, 2022). In practise (when this review was conducted), a CCT of 3,000 K, generally considered as “warm white” (DCCEEW, 2023; Illuminating Engineering Society, 2023b) or “neutral white” in colour appearance, has commonly been opted for by municipalities for pedestrian lighting. However, these metrics are developed based on the photometric and colourimetric system (Illuminating Engineering Society, 2011), for (limited) aspects of human vision. While useful in planning for visual performance, they remain simplified and insufficient from a multispecies perspective, and arguably inadequate for fully capturing human experience.

Spectral sensitivities of species vary compared to one another and humans (Longcore, 2023a,b). To better understand how light (and the broader electromagnetic spectrum) is evaluated in wildlife research and to assess how this research could apply to contemporary practise, we reviewed recent studies. Specifically, we aimed to explore two questions: (1) how (LED) lighting properties are measured, assessed, defined, and communicated in animal studies compared to human-targeted lighting research; and (2) how this could inform lighting practise aiming at minimising disturbance on wildlife.

2 Current practises identified

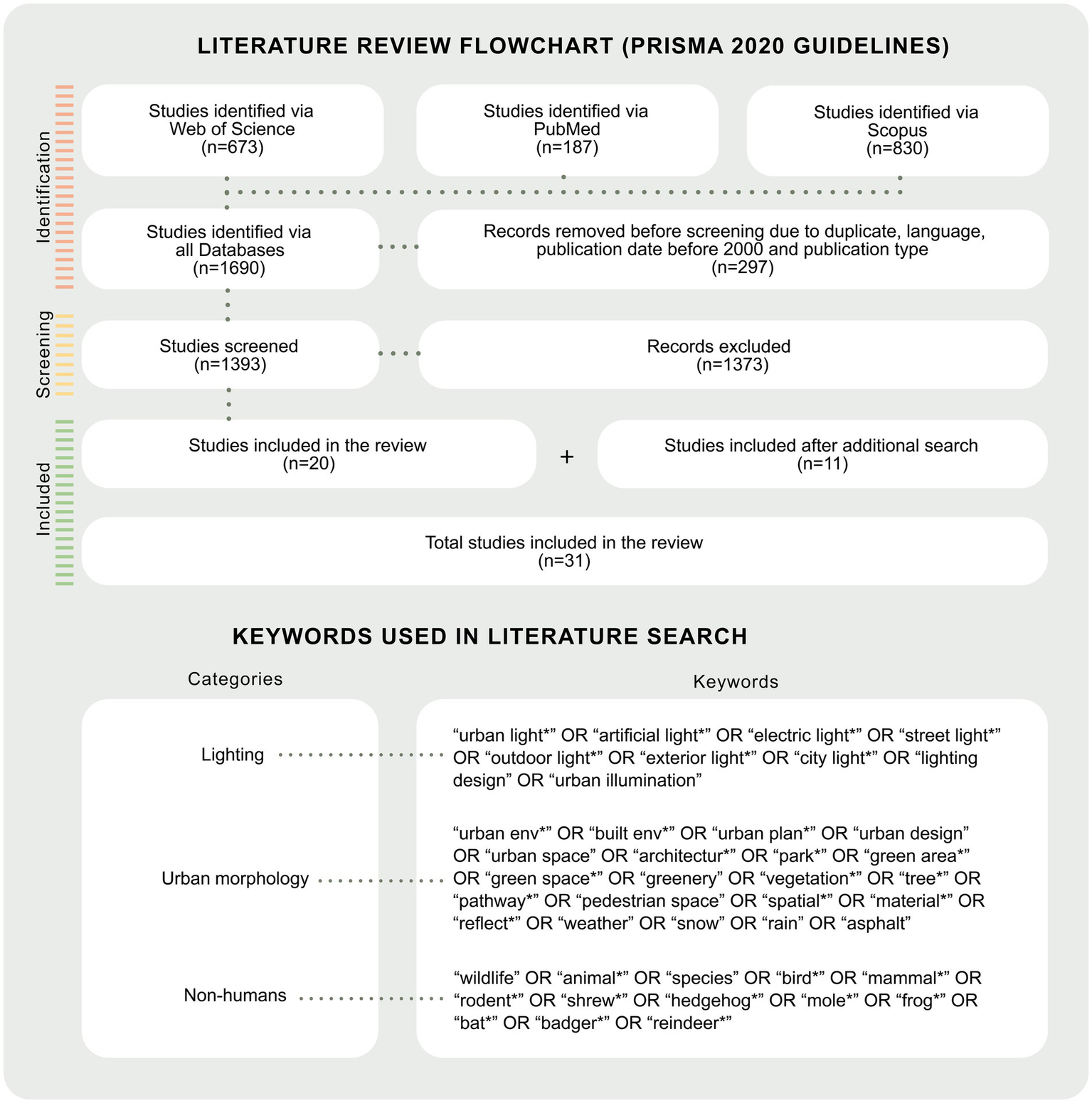

To guide our inquiry, we reviewed recent literature on the ecological studies involving LED lighting technologies. PRISMA 2020 guidelines were applied across Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus between 2023 and 2024, resulting in 1,690 articles. Keyword combinations in the non-human organism category (Figure 1) intentionally focused on taxa relevant to our broader research objectives. In line with the review’s focus, we excluded studies that addressed roadway- or building-adjacent lighting, omitted LEDs, involved unidentified organism groups, or used undefined light sources, or which were broadly described as ALAN. After applying the exclusion criteria, 31 recent research papers remained, focusing on avian species (11), bats (8), mammals (other than bats) (9), and amphibians (3). The review aimed to understand how lighting parameters are defined and measured in current wildlife ecology research, often with an emphasis on reducing ecological disruption.

Figure 1

Flow chart for the literature search process and selected studies for review using PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The literature searches were performed during the period of February to March 2023, and the papers were reviewed from March to May 2024. Additional searches were performed in March 2024 using the same research databases. The literature search was aimed at detecting and including only peer-reviewed articles, proceedings papers, and book chapters. In the identification stage, 1,690 studies were identified, and articles not relevant to our inquiry were excluded. The graphical inspiration is based on Figure 3 in Perez Vega et al. (2022).

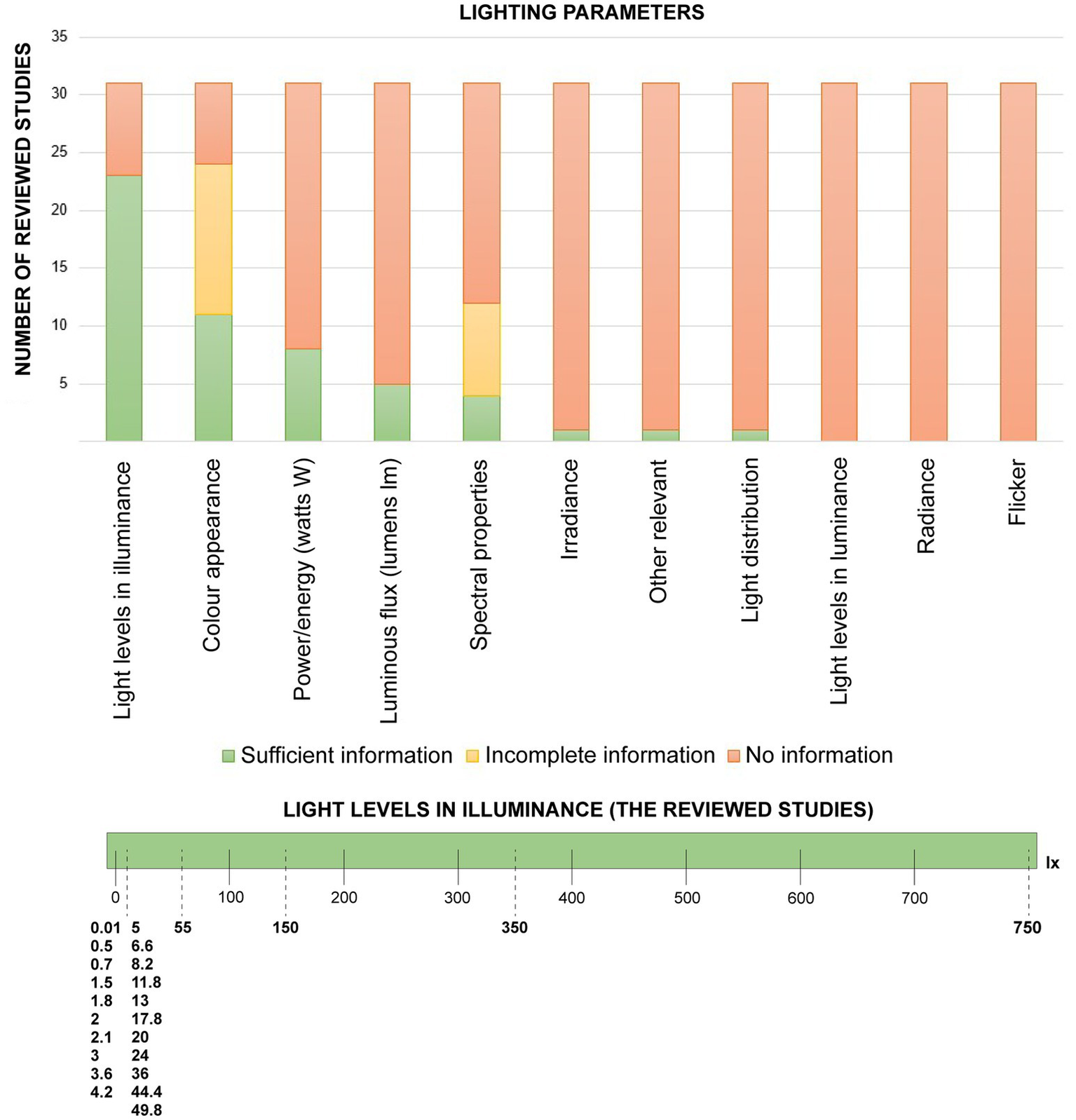

The results demonstrated limited alignment between light measurements and descriptions across studies. The lighting parameters in the reviewed papers were similar to those used in urban lighting design practises for humans (not wildlife). Species-neutral radiometric parameters relevant to ecological assessments were often omitted. Figure 2 summarises a range of possible lighting parameters and metrics and whether they were found in the 31 studies. Most reported metrics described to varying extents (e.g., sufficient, incomplete, or missing) are human-based (e.g., spot illuminance, illuminance distribution, CCT), and also radiometric information (peak wavelength, SPD). “Complete” or “missing” indicates whether studies included or omitted a parameter entirely, while “incomplete” denotes partial inclusion (e.g., a label or range without specificity).

Figure 2

The lighting parameters included and the relevant omitted parameters in the reviewed studies. The detailed units and definitions are found in the Supplementary Table 1.

Illuminance was included in 23 papers and was the most used parameter. CCT was described in ten papers; the other ten papers contained broad light colour descriptions (e.g., white, blue, and so on). Peak wavelength was reported in eight papers, and four other papers reported wavelength ranges (SPD); one paper studied light distribution. The experimental studies were conducted in either field or lab settings, except for one review paper. The term “field” is defined for studies conducted in natural environments of species, and the “lab” for controlled indoor facilities.

3 Wildlife responses

To clarify the type of ecological outcomes of electric lighting, this section summarises the findings from the reviewed papers. The studies aim to inform ecology-sensitive lighting practise and demonstrate electric lighting as a disrupting variable. The underlying question whether reporting different parameters (Figure 2) would allow for additional interpretations or comparisons is subsequently discussed.

3.1 Birds

11 studies were reviewed, ten experimental and one review. The majority of species were Great tits (Parus major), Blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus), Zebra finch (Taeniopygia gutatta) and Tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) in the studies. Lighting descriptions contained limited detail on CCT or spectra. Reported parameters included illuminance (0.5–5 lx) (Injaian et al., 2021; Dominoni et al., 2020; Dominoni et al., 2021; Dominoni et al., 2022; Grunst et al., 2020; McGlade et al., 2023; Alaasam et al., 2021; Ziegler et al., 2021), CCT, and spectral composition (Grunst et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020; van Dis et al., 2021). Light levels were linked to both physiological and behavioural changes (Injaian et al., 2021; Dominoni et al., 2020; Dominoni et al., 2021; Dominoni et al., 2022; McGlade et al., 2023; Alaasam et al., 2021; Ziegler et al., 2021), and spectral variation was mainly tested for behaviour (Zhao et al., 2020; van Dis et al., 2021). A review reported migratory disruptions at multiple spatial scales due to exposure to light pollution (Burt et al., 2023).

Reported effects varied, sometimes contradicting earlier findings (e.g., red light harmful to migration vs. later studies suggesting the opposite) (Zhao et al., 2020). Such inconsistencies likely reflect species sensory differences, age, health, habitat, additional stressors (noise, weather, and pollution), and study design (Dominoni et al., 2020; van Dis et al., 2021). Even low intensities (0.5–1.5 lx) induced physiological stress, altering hormones, immune responses, circadian regulation, sleep, and activity rhythms (Dominoni et al., 2021; Dominoni et al., 2022; Grunst et al., 2020; Ziegler et al., 2021). Migratory birds were strongly attracted to short-wavelength LEDs, especially in foggy or windy conditions, increasing collision risk (Zhao et al., 2020). “White” LEDs disturbed incubation behaviour (early start) (van Dis et al., 2021), with rural bird populations showing greater sensitivity than urban ones (McGlade et al., 2023).

3.2 Bats

One review paper and eight experimental studies investigated through LED lighting, some in comparison with other light sources [e.g., gas discharge (Li and Wilkins, 2022), mercury vapour lamps (Haddock et al., 2019) or high-pressure sodium (Rowse et al., 2016)]. All were measured in field experiments and connected to foraging and commuting activities. Some papers included information on CCT, energy usage in watts (W), or flux output in lumens (lm). Two papers specified peak wavelengths (Luo et al., 2021; Bolliger et al., 2020), and another paper compared light distributions described as “focused,” “diffused,” and “standard” (Bolliger et al., 2022). The measured light levels ranged from low (1–25 lx) to high (24–250 lx). Two reviewed papers experimented with different CCTs, including warm-appearing light (1750 K and 2,700 K), and reported either an inexplicit influence due to avoidance of cold-appearing light (4,000 K) (Bolliger et al., 2022) or no effect on bat activity (Bolliger et al., 2020).

The common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) was described as benefiting from electric lighting to hunt prey (Rowse et al., 2016; Bolliger et al., 2020), while horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus) reduced foraging in lit areas (Luo et al., 2021). It appears that light tolerance varies amongst bats, influencing their foraging behaviour, boosting prey access for opportunists but not altering bat-insect predator–prey dynamics (Li and Wilkins, 2022; Bolliger et al., 2020). One study linked LED lighting to changes in activity levels, with confounding variables (e.g., vegetation, habituation, and monitoring duration) complicating specific assessments of effects (Haddock et al., 2019).

3.3 Mammals (other than bats)

We identified nine papers on other mammals than bats; seven were lab studies conducted on rats or mice to investigate the physiological mechanisms of human health (Faborode et al., 2021; Romeo et al., 2017; Rumanova et al., 2022; Lundberg et al., 2019; Martynhak et al., 2017; Orhan et al., 2021; Zubidat et al., 2018; Willems et al., 2021), one studied pinyon mouse (Peromyscus truei) (Willems et al., 2021) in the field, and the other was a lab study on shrews (Crocidura russula) (Aparício et al., 2022). Light levels in illuminance (between 2 and 700 lx) were reported in seven studies (Faborode et al., 2021; Rumanova et al., 2022; Lundberg et al., 2019; Martynhak et al., 2017; Orhan et al., 2021; Zubidat et al., 2018; Aparício et al., 2022), and CCT (2700–3000 K) was reported in one study (Li and Wilkins, 2022). In other studies, light’s colour was described semantically as “yellow-LED” (Zubidat et al., 2018) or “white-LED” (Faborode et al., 2021; Willems et al., 2021) without CCT or SPD. The spectral range was described in three studies (Romeo et al., 2017; Rumanova et al., 2022; Zubidat et al., 2018), whereas the other two studies provided the peak wavelengths (Faborode et al., 2021). Species-neutral parameters, photon flux, and irradiance were included in two studies (Romeo et al., 2017; Zubidat et al., 2018).

3.4 Amphibians

The three reviewed papers included the common toad (Bufo bufo), Agile frog (Rana dalmatina) and Serrate-legged small treefrog (Kurixalus odontotarsus). Illuminance levels were used for assessments were grouped into lower (0.01 lx) to higher illuminances (55 lx). Two studies investigating gene expressions in juveniles indicated the CCT (6000–6500 K) (Touzot et al., 2023; Touzot et al., 2022). One study found minimal effect on melatonin-related genes, which suggests responses are species-specific (Touzot et al., 2023). Another study showed a significant effect on immune and lipid pathways under 5 lx with effects prolonging into daytime (Touzot et al., 2022).

Electric lighting has notable effects on molecular changes even in urban-tolerant species (e.g., common toad). One study found female small treefrogs preferring brighter lit environments mimicking the full moon illuminance [reported as 2.1 lx, although the full moon under clear sky is between 0.1 and 0.3 lx (Kyba et al., 2017)], implying an easier mate detection under increased light (Deng et al., 2019). Aquatic insects and anurans possess photosensitive receptors capable of detecting UV and near-IR light, with intensity and wavelength driving alterations (Schroer and Hölker, 2017; Holker et al., 2023). However, relevant parameters of irradiance or photon flux across UV and IR bands were not included in the studies.

4 Discussion – lighting design and wildlife research

Our review demonstrates that the most animal studies define and report LED lighting properties using a human-based system, reinforcing the human–ecology dichotomy in research and practise (Erixon et al., 2013). To make in-depth evaluations of the relationship between electric lighting and terrestrial species, a measurement toolbox on the use of different techniques and systems for measuring light and radiation beyond human vision (Hölker et al., 2021; DCCEEW, 2023; Apfelbeck et al., 2020) is needed. The ecological implications of electric lighting for wildlife species are mapped in previous research (Rich and Longcore, 2006; Schroer and Hölker, 2017; Perez Vega et al., 2022). This study’s results on how lighting properties are defined, measured, assessed, and communicated, notably including LEDs, call for transdisciplinary dialogues (Apfelbeck et al., 2020; Garrard et al., 2017). These initiatives have capacity to bridge ecological knowledge with human safety in lighting, urban and landscape planning practises. Likewise, ecology needs clearer definitions of light in experiments to enable properly adapted design practises for after-dark environments (Pérez Vega et al., 2021).

The review revealed inconsistent use and reporting of LEDs (e.g., “blue-LED”). Although spectral information is essential when studying species-specific responses, only a few papers reported on peak wavelength or spectral range, while others included CCT (indicating the light colour appearance). Incomplete and inaccurate descriptions (e.g., CCT or vague colour information) limits studying specific vulnerabilities further.

The measurement of SPD (radiant energy at different wavelengths) (Kalinkat et al., 2021) by researchers and practitioners could serve as a basis for follow-up calculations. Other methods to biologically assess species habitats include “environmental light field (ELF)” by Nilsson and Smolka (2021), “spectral tuning” by Longcore (2023a), and “α-opic irradiance metrology” (spectral tuning according to species light receptor physiology) by Lucas et al. (2024) and Schlangen and Price (2021). Some procedural recommendations include temporal and methodological variation in taxon sampling, in-depth analysis of control conditions, and relevant modes of measurement (e.g., determining location, time, metrics, and instruments) based on the research inquiry (Kalinkat et al., 2021; Jägerbrand and Bouroussis, 2021). Light pollution monitoring employs various measurement techniques (e.g., ground-based approaches, satellite-based, and airborne observations) (Kocifaj et al., 2023; Linares Arroyo et al., 2024), which are distinct from those used in wildlife and ecological studies (e.g., camera traps, acoustic sensors, or GPS tracking). Both approaches can be complementary in understanding impact of ALAN on ecological processes. However, the real-world dynamics and temporality (e.g., physical clutter, albedo, cloud height, aerosols) complicate both measurement accuracy and ecological implications (Kocifaj et al., 2023).

Wildlife assessments in the reviewed studies showed strong or weak correlations with lighting conditions. Disentangling the contribution of lighting from environmental stressors (e.g., other pollutants, weather conditions, and species-specific traits) is challenging. Low light levels (0.5–1.8 lx) have been shown to disrupt sleep patterns, extending the active period and accelerating incubation in birds. Recent research indicates even lower light levels can alter breeding, foraging, and singing behaviours (0.05 lx) and melatonin production (0.01 lx) (Aulsebrook et al., 2022).

An average light level on a pedestrian pathway in a suburban context (5 lx), was linked to substantial long-term physiological effects (e.g., on frogs). Short-wavelength-rich LEDs attracted some birds, altered incubation, and caused avoidance in certain bats under cold-appearing light at 4000 K. Later studies have shown that red light attracts some bat species while repelling others (Durmus et al., 2024). Variations or even contradictions across studies reveal confounder effects, such as seasonality and trait-based responses to multiple sensory pollutants (Hölker et al., 2021; Rich and Longcore, 2006; Haddock et al., 2019; Dominoni et al., 2020). These pollutants can have additive (effects sum), synergistic (effects exceed or shift from expectation), or antagonistic (mutually dampening) effects (Piggott et al., 2015). Such interactions vary in magnitude and direction depending on ecological scale, and sensory, physiological, and natural history (Dominoni et al., 2020).

Although confounding variables in the field might obscure implications of electric lighting, lab studies tend to employ unnaturally dark or overly bright conditions, failing to reflect the actual animal environments (Aulsebrook et al., 2022). Both approaches can offer complementary insights; however, they come with limitations. One approach could be conducting lab studies at the molecular, cellular, and organ-system levels while carrying out field research on organism and population behaviours. However, experimental setups and devices that lack sensitivity (or are costly) to detect dim conditions accurately risk misinterpreting results. Other works suggest a need for long-term monitoring (Kalinkat et al., 2021), and before-and-after control studies of wildlife and biodiversity, as they are rarely conducted (Christie et al., 2019), with even fewer studies focused on before-and-after different lighting conditions.

Carefully interpreting these outcomes leads to the assumption that lowered light levels and long-wavelength light content are worthwhile mitigation strategies for ALAN in site-specific testing. Such prototypical testing, by tuning light levels and spectrum, could be easily implemented with LED lighting systems. Additionally, dimming technologies can introduce temporal light modulation (flicker), which can negatively influence living organisms (Inger et al., 2014). More complete flicker characteristics and descriptions can be enabled through field-measuring devices in future studies.

Due to the inconsistencies identified in this review and the absence of consensus-based protocols (Kocifaj et al., 2023; Kalinkat et al., 2021), we propose using ecologically relevant lighting parameters (Figure 2; Supplementary Table 1) to be reported in animal studies to enable reproducibility and support ecologists as well as practitioners. Ongoing research by interdisciplinary teams could contribute to the development of realistic guidelines, metrics, methods, and instrument specifications for outdoor illumination (obtrusive light and skyglow) and wildlife measurements. Examples of current initiatives include: The Plan-B European Project, Aquaplan, NorDark, several IES and CIE Technical Committees (TC2-95, TC4-61), 4th Manchester Workshop on Light Metrics for Biology: Light Pollution.

5 Conclusion

In the reviewed studies on LEDs and its effect on animals, we found little alignment between reported light measures and species-specific sensitivities, making nuanced, practise-relevant interpretations difficult. Collaboration between lighting and ecology researchers could support more precise use of technology and design knowledge to consistently characterise light qualities in lab and field. Critically assessing and translating emergent knowledge (e.g., pilot studies in urban parks) into planning practise depends on transdisciplinary engagement, with policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders. When properly designed, wildlife-adapted LED illumination could support balancing human vision on walking paths and minimising adverse effects for other species, as highlighted in the Convention on Biodiversity. New findings will play a significant role when implementing the EU Nature Restoration Regulation (Habitat Restoration, 2024) or the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (Convention Biological Diversity, 2022).

Statements

Author contributions

SD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL-A: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MH: Writing – review & editing. KZ-D: Writing – review & editing. UB: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work is financially supported by NordForsk, grant #105116 and the Swedish Energy Agency, grant #P2021-00024.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ken Appleman for proofreading the paper.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1710192/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abelson E. Seymoure B. Jechow A. Perkin E. Moon H. Hölker F. et al . (2023). Ecological aspects and measurement of anthropogenic light at night. Rochester, NY, USA: SSRN.

2

Alaasam V. J. Liu X. Niu Y. Habibian J. S. Pieraut S. Ferguson B. S. et al . (2021). Effects of dim artificial light at night on locomotor activity, cardiovascular physiology, and circadian clock genes in a diurnal songbird. Environ. Pollut.282:117036. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117036,

3

Aparício G. Carrilho M. Oliveira F. Mathias M. L. Tapisso J. T. von Merten S. (2022). Artificial light affects the foraging behavior in greater white-toothed shrews (CROCIDURA RUSSULA). Ethology129, 88–98. doi: 10.1111/eth.13347,

4

Apfelbeck B. Snep R. P. H. Hauck T. E. Ferguson J. Holy M. Jakoby C. et al . (2020). Designing wildlife-inclusive cities that support human-animal co-existence. Landsc. Urban Plan.200:103817. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103817

5

Aronson M. F. J. La Sorte F. A. Nilon C. H. Katti M. Goddard M. A. Lepczyk C. A. et al . (2014). A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.281:20133330. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.3330

6

Aulsebrook A. E. Jechow A. Krop-Benesch A. Kyba C. C. M. Longcore T. Perkin E. K. et al . (2022). Nocturnal lighting in animal research should be replicable and reflect relevant ecological conditions. Biol. Lett.18:20220035. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0035,

7

Azam C. Le Viol I. Bas Y. Zissis G. Vernet A. Julien J.-F. et al . (2018). Evidence for distance and illuminance thresholds in the effects of artificial lighting on bat activity. Landsc. Urban Plan.175, 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.02.011

8

Bara S. Falchi F. (2023). Artificial light at night: a global disruptor of the night-time environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci.378:20220352. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0352

9

Barrientos R. Vickers W. Longcore T. Abelson E. S. Dellinger J. Waetjen D. P. et al . (2023). Nearby night lighting, rather than sky glow, is associated with habitat selection by a top predator in human-dominated landscapes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci.378:20220370. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0370,

10

Bolliger J. Haller J. Wermelinger B. Blum S. Obrist M. K. (2022). Contrasting effects of street light shapes and LED color temperatures on nocturnal insects and bats. Basic Appl. Ecol.64, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2022.07.002

11

Bolliger J. Hennet T. Wermelinger B. Blum S. Haller J. Obrist M. K. (2020). Low impact of two LED colors on nocturnal insect abundance and bat activity in a peri-urban environment. J. Insect Conserv.24, 625–635. doi: 10.1007/s10841-020-00235-1

12

Bolliger J. Hennet T. Wermelinger B. Bösch R. Pazur R. Blum S. et al . (2020). Effects of traffic-regulated street lighting on nocturnal insect abundance and bat activity. Basic Appl. Ecol.47, 44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2020.06.003

13

Boyce P. R. (2019). The benefits of light at night. Build. Environ.151, 356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.01.020

14

Bradshaw W. E. Holzapfel C. M. (2010). Light, time, and the physiology of biotic response to rapid climate change in animals. Annu. Rev. Physiol.72, 147–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135837,

15

Burt C. S. Kelly J. F. Trankina G. E. Silva C. L. Khalighifar A. Jenkins-Smith H. C. et al . (2023). The effects of light pollution on migratory animal behavior. Trends Ecol. Evol.38, 355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2022.12.006,

16

Cabrera-Cruz S. A. Smolinsky J. A. Buler J. J. (2018). Light pollution is greatest within migration passage areas for nocturnally-migrating birds around the world. Sci. Rep.8:3261. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21577-6,

17

Christie A. P. Amano T. Martin P. A. Shackelford G. E. Simmons B. I. Sutherland W. J. et al . (2019). Simple study designs in ecology produce inaccurate estimates of biodiversity responses. J. Appl. Ecol.56, 2742–2754. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13499

18

CIE (Commission internationale de l'éclairage) CIE 017:2020 ILV: International lighting vocabulary (2020)

19

Cieraad E. Strange E. Flink M. Schrama M. Spoelstra K. (2022). Artificial light at night affects plant–herbivore interactions. J. Appl. Ecol.60, 400–410. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.14336,

20

Convention Biological Diversity (2022). Kunming-Montreal Global biodiversity framework, 1–14.

21

DCCEEW (2023). National Light Pollution Guidelines for wildlife; 2.0. Canberra: Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (Commonwealth of Australia).

22

Deng K. Zhu B. C. Zhou Y. Chen Q. H. Wang T. L. Wang J. C. et al . (2019). Mate choice decisions of female serrate-legged small treefrogs are affected by ambient light under natural, but not enhanced artificial nocturnal light conditions. Behav. Process.169:103997. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2019.103997,

23

Ditmer M. A. Stoner D. C. Francis C. D. Barber J. R. Forester J. D. Choate D. M. et al . (2020). Artificial nightlight alters the predator–prey dynamics of an apex carnivore. Ecography44, 149–161. doi: 10.1111/ecog.05251,

24

Dominoni D. M. Borniger J. C. Nelson R. J. (2016). Light at night, clocks and health: from humans to wild organisms. Biol. Lett.12:20160015. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0015,

25

Dominoni D. M. de Jong M. van Oers K. O'Shaughnessy P. Blackburn G. J. Atema E. et al . (2022). Integrated molecular and behavioural data reveal deep circadian disruption in response to artificial light at night in male great tits (Parus major). Sci. Rep.12:1553. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05059-4

26

Dominoni D. M. Halfwerk W. Baird E. Buxton R. T. Fernandez-Juricic E. Fristrup K. M. et al . (2020). Why conservation biology can benefit from sensory ecology. Nat. Ecol. Evol.4, 502–511. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1135-4,

27

Dominoni D. M. Quetting M. Partecke J. (2013). Long-term effects of chronic light pollution on seasonal functions of European blackbirds (Turdus merula). PLoS One8:e85069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085069,

28

Dominoni D. Smit J. A. H. Visser M. E. Halfwerk W. (2020). Multisensory pollution: artificial light at night and anthropogenic noise have interactive effects on activity patterns of great tits (Parus major). Environ. Pollut.256:113314. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113314,

29

Dominoni D. M. Teo D. Branston C. J. Jakhar A. Albalawi B. F. A. Evans N. P. (2021). Feather, but not plasma, glucocorticoid response to artificial light at night differs between urban and Forest blue tit nestlings. Integr. Comp. Biol.61, 1111–1121. doi: 10.1093/icb/icab067,

30

Durmus D. Jägerbrand A. K. Tengelin M. N. (2024). Research note: red light to mitigate light pollution: is it possible to balance functionality and ecological impact?Light. Res. Technol.56, 304–308. doi: 10.1177/14771535231225362,

31

Erixon H. Borgström S. Andersson E. (2013). Challenging dichotomies – exploring resilience as an integrative and operative conceptual framework for large-scale urban green structures. Plan. Theory Pract.14, 349–372. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2013.813960

32

European Committee for Standardization (2016). “Light and lighting”. Road lighting – Part 2: Performance requirements; EN 13201-2:2016. Brussels: European Committee for Standardization (CEN).

33

Faborode O. S. Yusuf I. O. Okpe P. O. Okudaje A. O. Onasanwo S. A. (2021). Exposure to prolonged unpredictable light impairs spatial memory via induction of oxidative stress and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in rats. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol.33, 355–362. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2020-0160,

34

Falchi F. Cinzano P. Duriscoe D. Kyba C. C. M. Elvidge C. D. Baugh K. et al . (2016). The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Sci. Adv.2, 1–25. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600377,

35

Garrard G. E. Williams N. S. G. Mata L. Thomas J. Bekessy S. A. (2017). Biodiversity sensitive urban design. Conserv. Lett.11:e12411. doi: 10.1111/conl.12411

36

Gaston K. J. Bennie J. Davies T. W. Hopkins J. (2013). The ecological impacts of nighttime light pollution: a mechanistic appraisal. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc.88, 912–927. doi: 10.1111/brv.12036,

37

Gaston K. J. Visser M. E. Hölker F. (2015). The biological impacts of artificial light at night: the research challenge. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci.370, 1–6. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0133

38

Grunst M. L. Raap T. Grunst A. S. Pinxten R. Parenteau C. Angelier F. et al . (2020). Early-life exposure to artificial light at night elevates physiological stress in free-living songbirds(☆). Environ. Pollut.259:113895. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113895,

39

Habitat Restoration (2024). “The proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the council on nature restoration” in A9-0220/2023. ed. ParliamentT. E. (Strasbourg: Official Journal of the Europen Union). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L_202401991

40

Haddock J. K. Threlfall C. G. Law B. Hochuli D. F. (2019). Responses of insectivorous bats and nocturnal insects to local changes in street light technology. Austral Ecol.44, 1052–1064. doi: 10.1111/aec.12772

41

Hirt M. R. Evans D. M. Miller C. R. Ryser R. (2023). Light pollution in complex ecological systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci.378:20220351. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0351,

42

Hölker F. Bolliger J. Davies T. W. Giavi S. Jechow A. Kalinkat G. et al . (2021). 11 pressing research questions on how light pollution affects biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Evol.9:9. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.767177,

43

Holker F. Jechow A. Schroer S. Tockner K. Gessner M. O. (2023). Light pollution of freshwater ecosystems: principles, ecological impacts and remedies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci.378:20220360. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2022.0360,

44

Illuminating Engineering Society The lighting handbook: Reference and application; 2011.

45

Illuminating Engineering Society (2023a). Lighting practice: Environmental considerations for outdoor lighting. New York: Illuminating Engineering Society.

46

Illuminating Engineering Society (2023b). Lighting practice: Designing quality lighting for people in outdoor environment. New York: Illuminating Engineering Society.

47

Inger R. Bennie J. Davies T. W. Gaston K. J. (2014). Potential biological and ecological effects of flickering artificial light. PLoS One9:e98631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098631,

48

Injaian A. S. Uehling J. J. Taff C. C. Vitousek M. N. (2021). Effects of artificial light at night on avian provisioning, corticosterone, and reproductive success. Integr. Comp. Biol.61, 1147–1159. doi: 10.1093/icb/icab055,

49

Jägerbrand A. K. Bouroussis C. A. (2021). Ecological impact of artificial light at night: effective strategies and measures to Deal with protected species and habitats. Sustainability13:5991. doi: 10.3390/su13115991,

50

Jägerbrand A. K. Spoelstra K. (2023). Effects of anthropogenic light on species and ecosystems. Science380, 1125–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.adg3173,

51

Jechow A. Hölker F. (2019). Snowglow-the amplification of Skyglow by snow and clouds can exceed full Moon illuminance in suburban areas. J. Imaging5:8. doi: 10.3390/jimaging5080069,

52

Kalinkat G. Grubisic M. Jechow A. van Grunsven R. H. A. Schroer S. Hölker F. (2021). Assessing long-term effects of artificial light at night on insects: what is missing and how to get there. Insect Conserv. Divers.14, 260–270. doi: 10.1111/icad.12482

53

Kempenaers B. Borgstrom P. Loes P. Schlicht E. Valcu M. (2010). Artificial night lighting affects dawn song, extra-pair siring success, and lay date in songbirds. Curr. Biol.20, 1735–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.028,

54

Kocifaj M. Wallner S. Barentine J. C. (2023). Measuring and monitoring light pollution: current approaches and challenges. Science380, 1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.adg0473,

55

Kyba C. Mohar A. Posch T. (2017). How bright is moonlight?Astron. Geophys.58, 1.31–1.32. doi: 10.1093/astrogeo/atx025,

56

Kyba C. C. M. Ruhtz T. Fischer J. Hölker F. (2012). Red is the new black: how the colour of urban skyglow varies with cloud cover. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc.425, 701–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21559.x

57

Li H. Wilkins K. T. (2022). Predator-prey relationship between urban bats and insects impacted by both artificial light at night and spatial clutter. Biology11:829. doi: 10.3390/biology11060829,

58

Linares Arroyo H. Abascal A. Degen T. Aubé M. Espey B. R. Gyuk G. et al . (2024). Monitoring, trends and impacts of light pollution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ.5, 417–430. doi: 10.1038/s43017-024-00555-9

59

Lindén J. Dam-Hansen C. (2022). Flicker explained: guide to IEC for lighting industry. Lund, Sweden: Lund University, 17.

60

Longcore T. (2023a). A compendium of photopigment peak sensitivities and visual spectral response curves of terrestrial wildlife to guide design of outdoor nighttime lighting. Basic Appl. Ecol.73, 40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2023.09.002

61

Longcore T. (2023b). Effects of LED lighting on terrestrial wildlife; TR0003 (REV 10/98). Los Angeles, CA: California Department of Transportation and Regents of the University of California, 171.

62

Longcore T. Rich C. (2004). Ecological light pollution. Front. Ecol. Environ.2, 191–198. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0191:ELP]2.0.CO;2

63

Lucas R. J. Allen A. E. Brainard G. C. Brown T. M. Dauchy R. T. Didikoglu A. et al . (2024). Recommendations for measuring and standardizing light for laboratory mammals to improve welfare and reproducibility in animal research. PLoS Biol.22:e3002535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002535,

64

Lundberg L. Sienkiewicz Z. Anthony D. C. Broom K. A. (2019). Effects of 50 Hz magnetic fields on circadian rhythm control in mice. Bioelectromagnetics40, 250–259. doi: 10.1002/bem.22188,

65

Luo B. Xu R. Li Y. Zhou W. Wang W. Gao H. et al . (2021). Artificial light reduces foraging opportunities in wild least horseshoe bats. Environ. Pollut.288:117765. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117765,

66

Martynhak B. J. Hogben A. L. Zanos P. Georgiou P. Andreatini R. Kitchen I. et al . (2017). Transient anhedonia phenotype and altered circadian timing of behaviour during night-time dim light exposure in Per3(−/−) mice, but not wildtype mice. Sci. Rep.7:40399. doi: 10.1038/srep40399,

67

McGlade C. L. O. Capilla-Lasheras P. Womack R. J. Helm B. Dominoni D. M. (2023). Experimental light at night explains differences in activity onset between urban and forest great tits. Biol. Lett.19:20230194. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2023.0194,

68

McMunn M. S. Yang L. H. Ansalmo A. Bucknam K. Claret M. Clay C. et al . (2019). Artificial light increases local predator abundance, predation rates, and herbivory. Environ. Entomol.48, 1331–1339. doi: 10.1093/ee/nvz103,

69

Miller N. J. Leon F. A. Tan J. Irvin L. (2023). Flicker: a review of temporal light modulation stimulus, responses, and measures. Light. Res. Technol.55, 5–35. doi: 10.1177/14771535211069482

70

Nilsson D. E. Smolka J. (2021). Quantifying biologically essential aspects of environmental light. J. R. Soc. Interface18:20210184. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2021.0184,

71

Orhan C. Gencoglu H. Tuzcu M. Sahin N. Ozercan I. H. Morde A. A. et al . (2021). Allyl isothiocyanate attenuates LED light-induced retinal damage in rats: exploration for the potential molecular mechanisms. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol.40, 376–386. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2021.1978478

72

Ouyang J. Q. de Jong M. van Grunsven R. H. A. Matson K. D. Haussmann M. F. Meerlo P. et al . (2017). Restless roosts: light pollution affects behavior, sleep, and physiology in a free-living songbird. Glob. Chang. Biol.23, 4987–4994. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13756,

73

Pawson S. M. Bader M. K. F. (2014). LED lighting increases the ecological impact of light pollution irrespective of color temperature. Ecol. Appl.24, 1561–1568. doi: 10.1890/14-0468.1,

74

Pérez Vega C. Zielinska-Dabkowska K. M. Holker F. (2021). Urban lighting research transdisciplinary framework-a collaborative process with lighting professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020624,

75

Perez Vega C. Zielinska-Dabkowska K. M. Schroer S. Jechow A. (2022). A systematic review for establishing relevant environmental parameters for urban lighting: translating research into practice. Sustainability14:1107. doi: 10.3390/su14031107

76

Piggott J. J. Townsend C. R. Matthaei C. D. (2015). Reconceptualizing synergism and antagonism among multiple stressors. Ecol. Evol.5, 1538–1547. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1465,

77

Rich C. Longcore T. (2006). Ecological consequences of artificial night lighting. Washington, D. C., United States: Island Press.

78

Romeo S. Vitale F. Viaggi C. di Marco S. Aloisi G. Fasciani I. et al . (2017). Fluorescent light induces neurodegeneration in the rodent nigrostriatal system but near infrared LED light does not. Brain Res.1662, 87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.02.026,

79

Rowse E. G. Lewanzik D. Stone E. L. Harris S. Jones G. (2016). “Dark matters: the effects of artificial lighting on bats” in Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of bats in a changing world, eds. VoigtC. C.KingstonT. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer) 187–213.

80

Rozman Cafuta M. (2021). Sustainable city lighting impact and evaluation methodology of lighting quality from a user perspective. Sustainability13:3409. doi: 10.3390/su13063409

81

Rumanova V. S. Okuliarova M. Foppen E. Kalsbeek A. Zeman M. (2022). Exposure to dim light at night alters daily rhythms of glucose and lipid metabolism in rats. Front. Physiol.13:973461. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.973461,

82

Schlangen L. J. M. Price L. L. A. (2021). The lighting environment, its metrology, and non-visual responses. Front. Neurol.12:624861. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.624861,

83

Schreuder D. (2008). Outdoor lighting: Physics, vision and perception. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

84

Schroer S. Hölker F. (2017). “Impact of lighting on Flora and Fauna” in Handbook of advanced lighting technology. eds. KarlicekR.SunC.-C.ZissisG.MaR. (Cham: Springer), 957–989.

85

Seebacher F. (2022). Interactive effects of anthropogenic environmental drivers on endocrine responses in wildlife. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.556:111737. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2022.111737,

86

Seto K. C. Guneralp B. Hutyra L. R. (2012). Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA109, 16083–16088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211658109,

87

Touzot M. Dumet A. Secondi J. Lengagne T. Henri H. Desouhant E. et al . (2023). Artifical light at night triggers slight transcriptomic effects on melatonin signaling but not synthesis in tadpoles of two anuran species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol.280:111386. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2023.111386,

88

Touzot M. Lefebure T. Lengagne T. Secondi J. Dumet A. Konecny-Dupre L. et al . (2022). Transcriptome-wide deregulation of gene expression by artificial light at night in tadpoles of common toads. Sci. Total Environ.818:151734. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151734,

89

Trafikverket (2022). Krav - VGU Vägars och gators utformning; 2022: 001. Borlänge: Trafikverket.

90

van Dis N. E. Spoelstra K. Visser M. E. Dominoni D. M. (2021). Color of artificial light at night affects incubation behavior in the great tit, Parus major. Front. Ecol. Evol.9:9. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.728377,

91

Willems J. S. Phillips J. N. Vosbigian R. A. Villablanca F. X. Francis C. D. (2021). Night lighting and anthropogenic noise alter the activity and body condition of pinyon mice (Peromyscus truei). Ecosphere12:3. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3388,

92

Zhao X. Zhang M. Che X. Zou F. (2020). Blue light attracts nocturnally migrating birds. Condor122:duaa002. doi: 10.1093/condor/duaa002

93

Ziegler A. K. Watson H. Hegemann A. Meitern R. Canoine V. Nilsson J. A. et al . (2021). Exposure to artificial light at night alters innate immune response in wild great tit nestlings. J. Exp. Biol.224:jeb239350. doi: 10.1242/jeb.239350,

94

Zielińska-Dabkowska K. M. Xavia K. Bobkowska K. (2020). Assessment of citizens’ actions against light pollution with guidelines for future initiatives. Sustainability12:12. doi: 10.3390/su12124997,

95

Zubidat A. E. Fares B. Fares F. Haim A. (2018). Artificial light at night of different spectral compositions differentially affects tumor growth in mice: interaction with melatonin and epigenetic pathways. Cancer Control25:1073274818812908. doi: 10.1177/1073274818812908,

Summary

Keywords

urban lighting design, outdoor illumination, electric lighting, artificial light at night (ALAN), light-emitting diodes (LEDs), light pollution, ecological impact, interdisciplinary research

Citation

Dincel S, López-Alfaro C, Hedblom M, Zielinska-Dabkowska KM and Besenecker UC (2025) Inconsistent light measurement protocols in animal studies hinder wildlife-adapted LED illumination applications for natural habitats. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1710192. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1710192

Received

23 September 2025

Revised

22 November 2025

Accepted

02 December 2025

Published

19 December 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Rusty Gonser, Indiana State University, United States

Reviewed by

Sunil Dutt Shukla, Government Meera Girls College Udaipur, India

Gregor Kalinkat, Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB), Germany

Morgan Crump, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Dincel, López-Alfaro, Hedblom, Zielinska-Dabkowska and Besenecker.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seren Dincel, dincel@kth.se

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.