Abstract

Background:

Digital budgeting reforms increasingly hinge on collaborative governance. This study examines how strategic co-creation and synergistic partnerships shape Makassar’s e-budgeting and strengthen public governance for sustainable cities.

Methods:

A qualitative single-case design triangulates a five-year fiscal series (2019–2023), a regulatory hierarchy, internal documents, and 15 semi-structured interviews (government, DPRD, civil society, academia, banking/technology).

Results:

Makassar has established strong procedural rails—standardised workflows, KKPD non-cash instruments, bank integrations, and interoperable audit trails—enhancing transparency and control. Execution remains uneven: transfers realise ≈97–98%; PAD fluctuates ≈80–94%; total expenditure fell to ≈76% (2021–2022) before rebounding to ≈86% (2023). Participation is largely transactional; citizens/CSOs rarely engage in problem framing, prototyping, or joint evaluation.

Discussion:

We identify an operational “synergy gap”—strategic alliances not institutionalised as day-to-day co-monitoring and co-problem-solving. We advance a venue–capabilities–resilience (VCR) triad to explain why transparency gains in a SIPD-centred ecosystem do not automatically yield participatory governance.

Conclusion:

Closing the synergy gap requires performative co-creation: re-engineering Musrenbang as co-design sprints, a multi-party execution task force, audit-to-design rule translation, and local resilience to national platform disruptions. The findings offer portable guidance for cities linking digital rails to inclusive, accountable, and sustainable budgeting.

Highlights

-

E-budgeting reform in Makassar improved transparency but faced absorption challenges.

-

Strategic partnerships exist but remain fragmented, creating a “synergy gap.”

-

Citizens engaged as proposers, not co-creators, limiting participatory depth.

-

Reliance on SIPD exposes local systems to national-level vulnerabilities.

-

Policy reforms should institutionalize co-creation and enhance local resilience.

1 Introduction

The digital transformation of public financial management has become a critical frontier of contemporary governance reform (Bekiaris et al., 2025; Kotina et al., 2022). Across diverse institutional contexts, governments are adopting electronic budgeting (e-budgeting) systems to improve transparency, strengthen accountability, and enhance fiscal efficiency (A’yun and Hartaman, 2021; OECD, 2019; Shukhnin et al., 2025). In parallel, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)in particular SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions)—increasingly frame digital public finance as an enabling capability for urban sustainability, linking budgetary choices to allocative discipline, service equity, and resilience (UN-Habitat, 2020, 2022; United Nations, 2019). Within this broader trajectory, digital budgeting is no longer seen as a merely technical upgrade, but as a potentially transformative governance instrument that can align fiscal architecture with sustainability-oriented urban development.

In Indonesia, these global currents are channelled through the Sistem Pemerintahan Berbasis Elektronik (SPBE), which seeks to institutionalise digital governance across all tiers of government (Hadjarati et al., 2025). Presidential Regulations No. 95/2018 and No. 132/2022 on digital government architecture codify a strong national commitment to integrating planning, budgeting, and reporting via interoperable platforms (Isabella et al., 2024; Pribadi et al., 2024). At the core of subnational public financial management reform stands the Sistem Informasi Pemerintahan Daerah (SIPD), a centralised platform mandated by Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation No. 70/2019 to standardise procedures, harmonise classifications, and integrate financial data across provinces, districts, and municipalities, thereby enhancing vertical transparency and enabling consolidated fiscal oversight (Dellyana et al., 2023; Hafel, 2023). While this architecture promises greater consistency, traceability, and comparability of budgetary information, it also recentralises critical digital infrastructures and raises concerns about local autonomy, flexibility, and scope for innovation.

Within this national landscape, Makassar City has been widely recognised as one of the pioneering local governments in adopting e-budgeting as part of its Smart City and “Sombere’ & Smart City” agenda (Hafel, 2023; Setiawan et al., 2025; Wahyuni et al., 2024). Introduced in the mid-2010s, Makassar’s e-budgeting system aimed to modernise financial management by integrating planning and budgeting into a coherent digital platform (Abdul et al., 2025). The reform was explicitly framed as a socio-technical lever for sustainable urban outcomes: it was expected to address entrenched inefficiencies, minimise discretionary manipulation, and restore public trust in local governance, while steering resources toward resilient infrastructure, inclusive services, and low-carbon transitions (Thesari et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2018). Empirically, Makassar’s fiscal posture has become increasingly expansive, with annual budgets surpassing IDR 5 trillion by 2023 (Pagarra et al., 2024). Yet persistent gaps between planned allocations and realised expenditures—especially in capital spending—and continued structural dependence on intergovernmental transfers, indicate that the city still struggles to convert ambitious programming into consistent execution.

The implementation of e-budgeting in Makassar cannot be understood solely as a technocratic exercise; it is embedded in an ecosystem of synergistic partnerships that shape both opportunities and constraints (Anggara et al., 2025; Suryana et al., 2024; Taufik, 2023). The municipal executive, the Regional People’s Representative Council (DPRD), civil society organisations (CSOs), academic institutions, and private sector actors have played differentiated yet interconnected roles over the course of the reform (Tuanaya and Rengifurwarin, 2023). The executive branch has promoted e-budgeting as a flagship policy for transparency and anti-corruption, seeking to harness digital tools to discipline bureaucratic behavior and signal probity (Reynilda and Renal, 2025; Ríos et al., 2016). The legislature, initially more resistant, has navigated a gradual process of adaptation, moving towards alignment through mechanisms such as the institutionalisation of legislative priorities (pokok pikiran) within the digital planning system (Chima et al., 2024; Gaol and Suryani, 2024). CSOs and non-governmental organisations have acted predominantly as external watchdogs, providing oversight and critique rather than being systematically integrated into formal decision-making processes (Hollibaugh and Krause, 2023). Academic institutions have contributed analytical insights and strategic advice, yet their potential for sustained operational engagement in system design and evaluation remains underutilised (Kang et al., 2019; O’Neill, 2019). Private sector partners in technology and finance have supported the digital infrastructure—enabling non-cash transactions and interoperable data flows that intersect with urban service delivery in domains such as waste management, drainage, and public transport (Kang et al., 2019).

Despite these advances, Makassar’s experience reveals significant structural and operational vulnerabilities (Fuady et al., 2025; Setiawan et al., 2024; Setyono et al., 2018). The city’s reliance on SIPD as a centralised national platform implies that local budgeting processes are tightly coupled to a system over which the municipality exercises limited control. Technical failures or performance issues at the national level can directly disrupt local operations, including salary disbursement and key stages of the budget cycle (Balqis and Fadhly, 2021; Vitriana et al., 2022). Moreover, while e-budgeting has improved the formal rigour and auditability of budget formulation, its capacity to deepen participatory governance and to align spending with sustainability priorities appears constrained (Oh et al., 2019; Treija et al., 2021; Zolotov et al., 2018). Existing participatory mechanisms such as Musrenbang are frequently criticised as transactional and insufficiently deliberative, reducing citizen engagement to the submission of technical proposals that are often filtered or diluted through bureaucratic and political negotiations (Akbar et al., 2020).

Recent scholarly debates on public governance underscore that digital reforms are unlikely to achieve their transformative potential in the absence of meaningful co-creation (Ansell and Torfing, 2021; Kalvet et al., 2018a, 2018b; Meijer and Boon, 2024; Stoll et al., 2021). Co-creation theory posits that value in governance emerges from collaborative interaction among state and non-state actors, where each partner contributes distinct resources, knowledge, and capabilities to joint problem-solving (Guo and Zhang, 2024; Lember et al., 2019). In the realm of e-budgeting, synergistic partnerships are therefore essential to address the multi-dimensional challenges—technical, institutional, socio-political, and sustainability-related—that exceed the capacity of government agencies acting alone. Makassar’s reforms exemplify both the promise and the limitations of such an approach: although strategic alliances have been assembled, limited integration of actors at the operational layer generates a “synergy gap” that undermines the full potential of digital budgeting to support sustainable and inclusive cities.

At the same time, the Indonesian model of centralised digital infrastructure intensifies the tension between standardisation and local autonomy (Craig et al., 2025; Nugroho et al., 2023; Wawer et al., 2022). SIPD functions as an infrastructural backbone for subnational public financial management, providing standardised procedures and integrated data, but also introducing a single point of failure, strong dependence on central policy decisions, and restricted scope for local experimentation in system design and participatory features (Kusuma et al., 2023; Mahesa et al., 2019). These tensions are particularly salient for cities like Makassar that seek to position themselves as laboratories for smart city and co-creation-based digital governance while operating within a tightly governed national digital architecture (Isabella, 2025; Mappisabbi, 2025).

Makassar has increasingly branded itself as a laboratory for co-creation in urban governance under the “Sombere’ & Smart City” banner and through its digital budgeting reforms (Malik, 2025; Nggilu, 2025; Setiawan et al., 2025). Participatory planning instruments such as Musrenbang, e-Musrenbang, and thematic consultative forums are officially framed as arenas in which citizens, community leaders, and civil society organisations can articulate development priorities and collaboratively shape budgetary decisions (Damayanti et al., 2025; Mursalin, 2025; Prastiwi, 2025; Syafaruddin and Haris, 2025). Within this policy discourse, digital platforms and inter-organisational partnerships are presented as key enablers of a shift from technocratic, top-down budgeting towards more inclusive, citizen-centric governance (Baillie et al., 2025; Burnett and Jones, 2025; Maitima and Munene, 2025). Empirically, however, the findings of this study indicate that what is labelled as “co-creation” in Makassar largely remains confined to relatively shallow forms of participation, concentrated at the stage of proposal submission rather than extending to joint problem framing, co-design, prototyping, or iterative evaluation of digital budgeting tools. Interpreted through Arnstein’s ladder of participation, these practices cluster around tokenistic rungs—information, consultation, and placation—rather than approaching partnership or citizen control (Pambila et al., 2025; Seetharaman et al., 2025; Yusof et al., 2025). This reveals a persistent disjuncture between the rhetoric of co-creation and its practical enactment: participatory mechanisms and digital channels have been formally expanded, yet the effective influence of citizens over the design, governance, and performance of e-budgeting systems remains limited.

Against this backdrop, the present study examines the role of strategic co-creation and synergistic partnerships in advancing digital budgeting reforms to strengthen public governance for sustainable cities in Makassar. Drawing on documentary analysis, regulatory review, and qualitative evidence from key stakeholders, the article contributes to theory and practice in three main ways. First, it illuminates how co-creation is operationalised—and constrained—within a centrally standardised digital budgeting architecture in a Global South urban context. Second, it analyses how diverse partnerships among governmental, societal, and private actors shape the design, implementation, and outcomes of e-budgeting, highlighting the conditions under which these partnerships generate, or fail to generate, substantive co-creation. Third, it distils lessons for broader debates on digital governance, collaborative public management, and sustainable urban governance, particularly concerning how digital budgeting reforms can move beyond declarative commitments to co-creation towards more substantive, inclusive, and resilient forms of urban fiscal governance.

2 Literature review

2.1 Digital budgeting and public financial management reforms

Digital budgeting, commonly conceptualised as e-budgeting, has become a central pillar of contemporary public financial management (PFM) reforms (Krynytsia, 2024; Sikabanga and Haabazoka, 2025). Rather than simply automating pre-existing procedures, digital budgeting platforms reconfigure how fiscal information is generated, processed, and communicated across administrative units and to external stakeholders. Integrated financial management information systems and online budgeting portals are introduced not only to streamline internal workflows, but also to enhance transparency, strengthen accountability, and support timelier, data-driven decision-making in the allocation, execution, and monitoring of public resources. In this sense, digital budgeting is better understood as a transformation of fiscal governance infrastructures than as a purely technical upgrade (Baidalinova et al., 2025; Metelenko et al., 2025).

Within the public finance and open government literature, e-budgeting is closely associated with efforts to advance fiscal transparency and open government (Gacitua et al., 2021; OECD, 2019). By making budget documents, spending data, and performance indicators available in machine-readable formats, digital systems are expected to reduce information asymmetries and facilitate external scrutiny by legislatures, audit institutions, civil society, and the media. At the same time, digital interfaces can lower the transaction costs of citizen engagement by providing channels for submitting proposals, commenting on draft budgets, and tracking the implementation of funded activities. Yet, the extent to which these technological affordances translate into substantive shifts in power relations, voice, and accountability remains an open empirical question—particularly in decentralised settings and in the diverse institutional environments of the Global South. Digital budgeting may enable new forms of co-monitoring and contestation, but it can equally entrench existing hierarchies if design, access, and digital skills are unevenly distributed (Baidalinova et al., 2025; Kazanskaia, 2025; Mariu et al., 2025).

Global normative frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide an important backdrop for these reforms. In particular, SDG 16 (peaceful, just, and inclusive institutions) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) encourage governments to harness digital tools to support participatory, accountable, and inclusive decision-making at multiple scales (Sultana and Turkina, 2023; Zulkefli et al., 2021; Mrabet and Sliti, 2024). From this perspective, e-budgeting is expected to connect fiscal choices to sustainability outcomes in at least three ways: first, by improving allocative discipline and medium-term planning so that scarce public resources are steered towards resilient, low-carbon infrastructure and inclusive services; second, by embedding transparency and auditability that curb leakage, reduce opportunities for discretion, and enable civic co-monitoring; and third, by enabling data-driven, cross-sector coordination—across transport, water, waste, housing, and other domains—through interoperable digital platforms that reveal trade-offs and synergies in urban investments.

In this article, SDG frameworks function not as the primary analytical lens, but as a normative horizon against which concrete reform trajectories can be assessed. The core analytical focus lies on how digital budgeting reforms interact with local institutional arrangements, participatory architecture, and co-creation practices in specific urban governance contexts such as Makassar. In such settings, the same digital infrastructure that promises enhanced transparency and coordination may, depend on its design and governance, also centralise control, privilege technically proficient actors, or reproduce tokenistic forms of participation. When combined with genuinely co-creative processes and synergistic partnerships, digital budgeting can evolve into a governance capability that helps direct scarce resources toward projects with the highest social–ecological value and strengthens urban resilience. Absent these enabling conditions, it risks amounting primarily to the digitisation of inherited budgeting routines, with limited impact on the deeper logics of public financial management and democratic governance.

2.2 Co-creation in public governance

Co-creation has emerged as a central paradigm in contemporary public governance, signalling a shift away from hierarchical, top-down steering towards more participatory and collaborative arrangements (Ansell and Torfing, 2021; Rubalcaba et al., 2022). Building collaborative governance and public value theory, co-creation emphasises the joint design, delivery, and evaluation of public policies and services by governments and their stakeholders (Kalvet et al., 2018a, 2018b). In contrast to conventional participation, which often limits citizens to consultative or advisory roles, co-creation actively involves diverse actors in problem framing, option generation, implementation, and assessment. This broader role is associated with enhanced legitimacy, innovation, and effectiveness, particularly in contexts characterised by complex, cross-cutting problems.

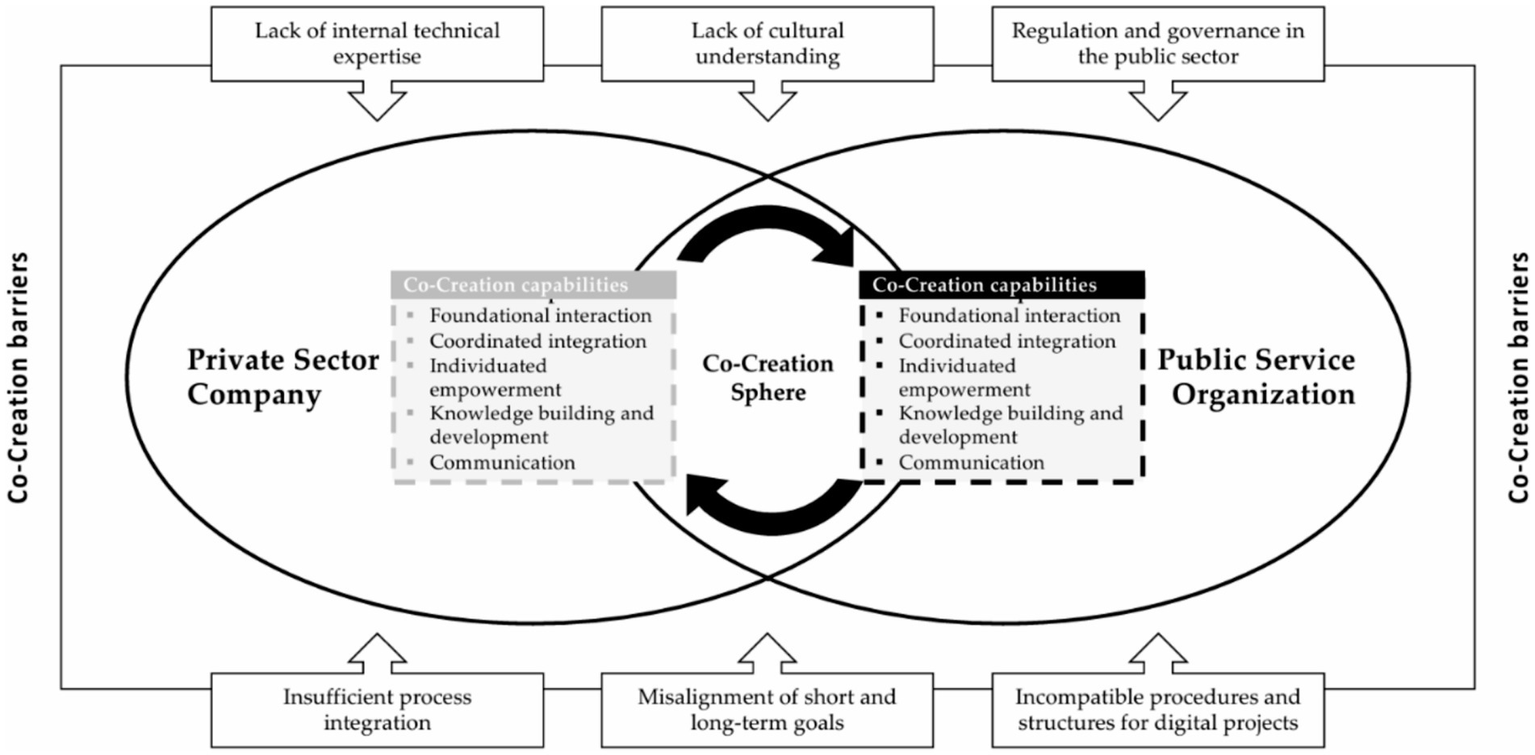

The literature on public-service co-creation in digitalisation contexts highlights several organisational capabilities that condition whether co-creation remains rhetorical or becomes substantively embedded. Rösler et al. (2021), for instance, identify five capabilities: individuated empowerment (an open, change-receptive culture that allows partners to reshape methods and structures), knowledge building and development (reciprocal skill and knowledge exchange to address technical gaps and asymmetries), foundational interaction (early alignment on goals, roles, and cooperation logics), coordinated integration (synchronising partners’ contributions and processes), and communication (continuous, structured information exchange to align expectations and reduce knowledge imbalances). These capabilities are particularly salient for digital reforms, where co-creation must bridge technical complexity, institutional inertia, and diverse stakeholder capacities.

Public-service co-creation in digitalization contexts rests on five organizational capabilities that directly confront typical barriers in public service ecosystems: individuated empowerment (an open, change-receptive culture that allows partners to reshape methods and structures), knowledge building and development (reciprocal skill and knowledge exchange to address technical gaps and asymmetries), foundational interaction (early alignment on goals, roles, and cooperation logic), coordinated integration (synchronizing partners’ contributions and processes), and communication (continuous, structured information exchange to align goals and reduce knowledge imbalances) (Rösler et al., 2021) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Overview of identified capabilities for co-creation (Rösler et al., 2021).

In digital governance, empirical studies indicate that reforms achieve higher sustainability when they are co-created with stakeholders rather than imposed unilaterally (Lember et al., 2019). Co-creation can foster trust and shared ownership, which are critical for overcoming scepticism and resistance to innovation in public administration. Conversely, when co-creation is limited to symbolic consultations or narrow expert circles, digital platforms may reinforce technocratic decision-making and exacerbate existing inequalities in access and influence. These tensions are central to the analysis of digital budgeting reforms in Makassar.

2.3 The four meta-models of co-creation

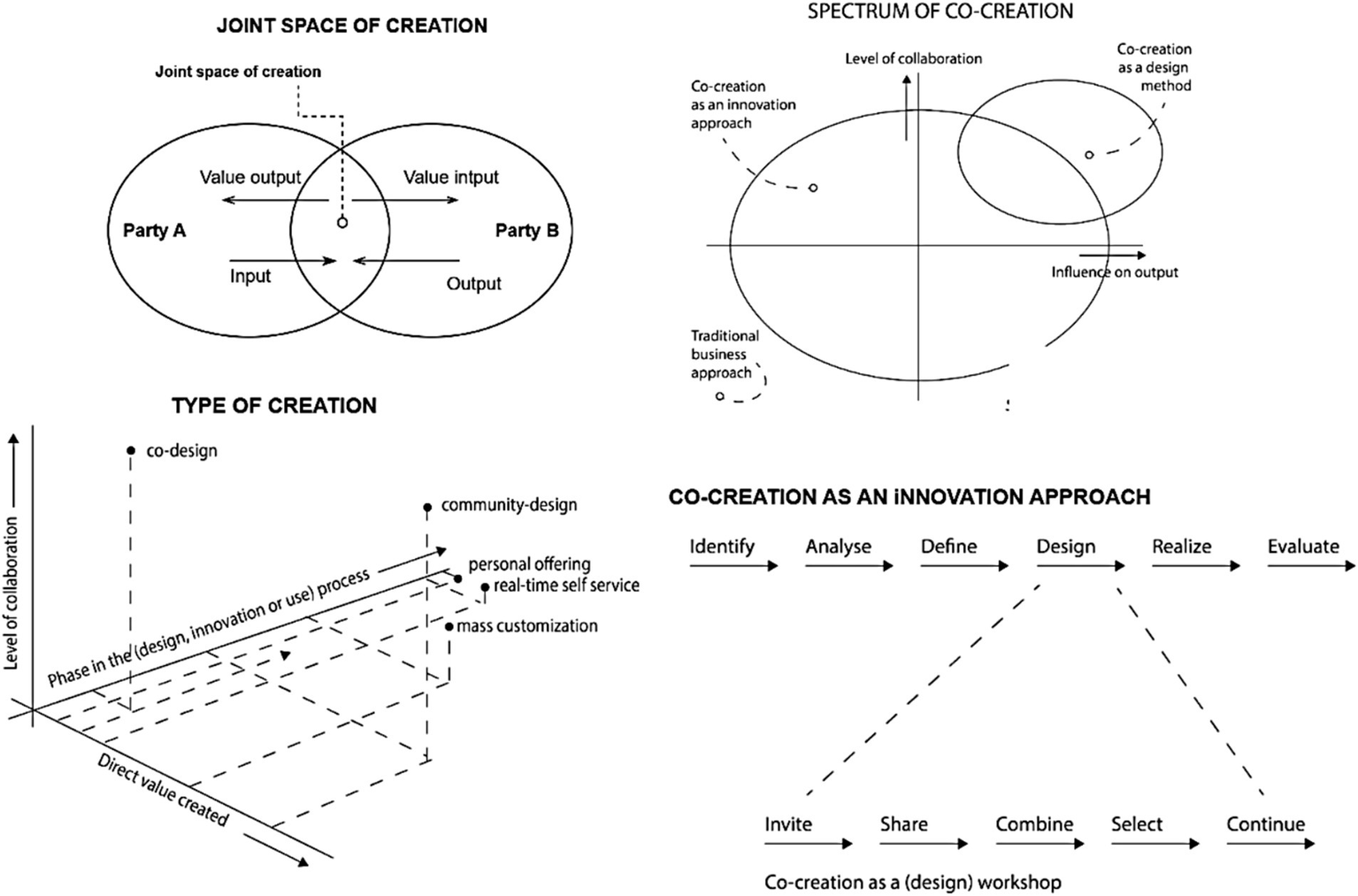

Beyond general principles, recent work has sought to make the concept of co-creation more analytically tractable through visual and structural meta-models. De Koning et al. (2016) synthesise fifty co-creation visuals into four concise meta-models (Figure 2):

Figure 2

The four meta-models of co-creation. Source: in adoption from De Koning et al. (2016).

De Koning, Crul, and Wever synthesize fifty co-creation visuals into four concise meta-models (Figure 2): (1) joint space of creation—the locus where actors co-produce value; (2) co-creation spectrum—a continuum from consultation to collaboration specifying the intensity of power-sharing; (3) types of co-creation—variants by timing and depth (personal offering, real-time self-service, mass customization, co-design, community design); and (4) process steps—4–6 staged sequences treating co-creation as method or approach (De Koning et al., 2016). Relevance to digital budgeting: the meta-models (i) locate the value-creation arena across government–DPRD–citizen–CSO interfaces, (ii) calibrate non-state influence when designing participatory rules, (iii) guide fit-for-purpose engagement (e.g., co-design for Musrenbang, community oversight for neighborhoods), and (iv) structure the reform pathway from framing to evaluation within SIPD. Consistent with digital governance research, co-created reforms are more sustainable and build trust and shared ownership (Lember et al., 2019).

For digital budgeting, these meta-models offer a structured vocabulary for locating and assessing co-creation practices. They help to (i) identify where the joint space of creation is situated across government–DPRD–citizen–CSO interfaces; (ii) calibrate the degree of non-state influence when designing participatory rules and digital interfaces; (iii) guide fit-for-purpose engagement strategies (e.g., co-design for Musrenbang, community oversight for neighbourhood-level monitoring); and (iv) structure the reform pathway from framing to evaluation within platforms such as SIPD. In the present study, the meta-models are not treated as formal theories, but as analytical instruments that support the operationalisation of co-creation in the Makassar case.

2.4 Citizen participation, digital literacy, and people-centric governance

A substantial body of research has underscored that the democratic benefits of digital platforms are contingent on the depth and quality of citizen participation they enable, rather than on their mere existence. E-participation and digital engagement initiatives can support more inclusive governance when citizens are able not only to access information, but also to understand, interpret, and critically engage with complex budgetary data. From this vantage point, digital literacy—encompassing technical, informational, critical, and civic dimensions—constitutes a fundamental precondition for meaningful participation in digital budgeting (Dyussenov et al., 2025).

Classic frameworks of participation, such as Arnstein’s ladder, remind us that participatory arrangements can range from manipulation and tokenism to partnership and citizen control (Akasaka et al., 2022; Schroeer et al., 2021). Digital platforms may expand opportunities for information and consultation, yet still situate citizens on the lower, tokenistic rungs if their contributions are weakly integrated into decision-making (Sanderson et al., 2024; Sieber et al., 2025; Varwell, 2022). Recent work on people-centred governance and digital citizenship, including studies at Astana IT University, shows how integrating digital literacy into active learning frameworks and institutional strategies can enhance participants’ ability to navigate, evaluate, and responsibly use digital tools for both educational and governance purposes (Akasaka et al., 2022; Chau, 2024; Warraitch et al., 2023). In public administration, these insights suggest that digital platforms only become genuinely empowering when citizens and stakeholders possess the competencies required to co-interpret data, articulate informed preferences, and hold decision-makers to account, rather than merely submitting inputs into opaque processes (Mouter et al., 2021; Popescul et al., 2024; Shava and Muringa, 2025).

From a governance perspective, digital literacy is therefore not an ancillary concern but an enabling condition for people-centric and co-creative arrangements. Without adequate investments in capacity-building for both state and non-state actors, co-creation risks becoming highly formalistic: platforms may invite participation in principle, but actual engagement remains shallow, skewed towards more privileged groups, or mediated almost entirely by experts and intermediaries. In the context of Makassar, this study examines digital budgeting reforms and associated participatory mechanisms while acknowledging that it does not yet provide a systematic measurement of digital literacy levels across stakeholder groups. This limitation is revisited in the Discussion as both an agenda for future research and a critical dimension for policy design, given the central role of digital literacy in enabling citizens to move from tokenistic engagement towards substantive co-design and joint evaluation of digital budgeting systems.

2.5 Comparative and global experiences with digital budgeting reforms

Comparative experience from other Asian and global contexts provides a useful reference point for situating Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms. In Malaysia, reforms in digital governance and e-participation have often been framed through initiatives to expand online portals for budget information, feedback mechanisms, and consultative platforms at both national and local levels (Man and Manaf, 2023; Seng Boon et al., 2020). While these initiatives demonstrate relatively advanced use of digital tools for transparency and consultation, scholarly assessments point to enduring tensions between centralised control, bureaucratic steering, and aspirations for more deliberative, citizen-driven forms of participation. These ambivalences highlight how digital infrastructures can facilitate access and visibility without necessarily transforming underlying power relations or policy design practices (Costopoulou et al., 2021; Indama, 2022; Nur Salam Man and Abdul Manaf, 2024).

South Korea is frequently cited as a global frontrunner in digital government, with sophisticated infrastructures for open data, smart city projects, and online citizen engagement (Ryu et al., 2022). Systems such as dBrain integrate planning, budgeting, and execution, enabling real-time monitoring and reducing opportunities for fiscal mismanagement (Chung et al., 2022). Yet critical studies underline persistent frictions between high-tech solutions and inclusive governance, pointing to digital divides, differential capacities among user groups, and the risk that complex systems reinforce technocratic modes of decision-making (Choo et al., 2023). The Korean experience illustrates that technological advancement alone does not guarantee deep co-creation: the institutional embedding of citizen input, the design of participatory interfaces, and social inequalities in digital skills remain key determinants of whether digital platforms open or narrow spaces for public influence (Choo et al., 2023; Ghose and Johnson, 2020; Gillispie, 2021; Lee et al., 2022).

In Kazakhstan, emerging work on people-centred governance and digital literacy—again exemplified by initiatives at Astana IT University—emphasises how deliberate investments in digital competencies can be aligned with broader efforts to democratise decision-making and promote more responsible, citizen-oriented uses of technology (Abil and Bauyrzhankyzy, 2023; Hartanti et al., 2021). These studies suggest that digital literacy programmes can help bridge the gap between formal opportunities for participation and the actual ability of individuals and communities to exercise agency within digital governance system (Kabwe et al., 2024; Takhan and Khussainova, 2024).

International evidence documented by the OECD and related organisations indicates that digital budgeting has emerged as a central pillar of fiscal transparency reforms in a range of jurisdictions, including Brazil and (Apleni and Smuts, 2020; Carneiro Ramos et al., 2019). Brazil’s Portal da Transparência illustrates how open budget data infrastructures can enhance public oversight and enable civil society to scrutinise government expenditures, while Estonia’s digitally integrated public finance systems—embedded within a comprehensive e-governance architecture—underscore the role of interoperability and citizen-centric design in reinforcing fiscal discipline and democratic accountability (Kalvet et al., 2018a; Krimmer et al., 2021). At the same time, the global literature consistently highlights enduring constraints on the transformative potential of e-budgeting: institutional resistance, uneven digital literacy, and disparities in infrastructural access frequently mediate outcomes, such that improvements in transparency do not necessarily translate into meaningful participation or a substantive redistribution of decision-making power.

Taken together, comparative and global evidence indicates that the interplay between digital transformation initiatives, citizen participation, and co-creation is highly conditional upon institutional configurations, sustained capacity-building, and the uneven distribution of digital competencies. Within this spectrum, Makassar and other Indonesian cities occupy an intermediate position: while digital budgeting platforms and participatory discourses are being actively adopted, the surrounding institutional arrangements and digital literacy ecosystems have yet to fully support more substantive forms of co-creation. Positioning the Makassar case within these international experiences enables the study to illuminate both common challenges—such as the tendency towards technocratic or elite-driven modes of engagement—and context-specific dynamics shaped by Indonesia’s decentralised governance architecture and its evolving landscape of digital skills.

2.6 Implications for the Makassar case

The literature reviewed above yields three interrelated insights that are particularly salient for the analysis of Makassar. First, co-creation theory suggests that the sustainability of digital budgeting reforms depends on embedding participatory mechanisms that move beyond tokenistic consultation towards more substantive forms of joint design and evaluation. Second, synergistic partnerships—among governmental actors, legislatures, civil society, academia, and the private sector—are critical for mobilising diverse resources and capabilities in contexts where technical, institutional, and fiscal constraints limit the capacity of government agencies acting alone. Third, global experiences demonstrate that while e-budgeting can significantly enhance transparency and efficiency, its transformative potential hinges on how well it is integrated with broader governance reforms, capacity-building efforts, and citizen engagement strategies.

These insights provide a robust conceptual and empirical foundation for the Makassar case. They also point to the need for an explicit theoretical framework that can (i) specify how collaborative governance and co-creation are understood in this study; (ii) conceptualise synergistic partnerships as an enabling condition for digital budgeting reforms; (iii) treat digital literacy and capacity building as moderating factors that shape the depth and inclusiveness of co-creation; and (iv) operationalise co-creation using concrete analytical tools, such as co-creation capabilities and meta-models. The following section develops this theoretical framework, which then guides the qualitative analysis of Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms.

3 Theoretical framework

3.1 Collaborative governance and co-creation theory

The study is anchored in theories of collaborative governance and co-creation, which conceptualise public problem-solving as a process involving multiple actors—state agencies, private organisations, and civil society—working jointly across organisational and jurisdictional boundaries (Ansell and Torfing, 2021; Setiawandari and Kriswibowo, 2023; Ansell and Gash, 2008). Collaborative governance emphasises structured, cross-boundary interactions underpinned by shared norms, joint decision-making, and mutual accountability. Co-creation extends this logic by foregrounding the role of users and citizens not merely as consultees or implementers, but as co-designers of policies, services, and institutional arrangements (Lember et al., 2019; Ng et al., 2024).

In the context of digital budgeting, these theoretical lenses direct attention to who is involved, at which stages of the policy and design cycle, and with what degree of influence over the rules and infrastructures that shape fiscal decisions. Arnstein’s ladder of participation provides a normative gradient for assessing the depth of involvement, from manipulation and tokenism to partnership and citizen control. Combining collaborative governance and co-creation theory with Arnstein’s insights allows this study to interrogate the discrepancy between the rhetoric of “strategic co-creation” and the actual distribution of power and agency in Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms.

3.2 Synergistic partnerships as an enabling condition

Within this broader collaborative framework, synergistic partnerships are conceptualised as an enabling condition that can either support or constrain co-creation in digital budgeting reforms (Kwon et al., 2023; Sundaram, 2018). Such partnerships encompass formal and informal relationships among municipal departments, higher-level government agencies, IT vendors, universities, and civil society organisations. When characterised by mutual trust, complementary resources, and clear but flexible governance arrangements, these partnerships can generate synergies that enhance the design, implementation, and sustainability of digital budgeting platforms (Hamu et al., 2021). Conversely, partnerships that remain closed, technocratic, or dominated by a narrow set of expert actors may reproduce hierarchical dynamics and restrict the scope for citizen-driven influence over digital governance infrastructures (Kalogirou et al., 2022).

The concept of synergistic partnerships builds on theories of inter-organisational collaboration and collaborative governance, which posit that complex societal challenges cannot be addressed by governments alone but require the pooling of complementary resources and capabilities (Meijer and Boon, 2024). Synergy arises when the combined outcome of collaboration exceeds the sum of individual contributions, generating added value through interdependence, coordination, and joint learning (Jung and Cho, 2023). In governance reforms, synergistic partnerships often take the form of multi-stakeholder alliances involving government agencies, legislative bodies, civil society organisations, academia, and private-sector actors. Such alliances can enable knowledge sharing, mutual learning, and innovation, while also mitigating risks associated with unilateral decision-making and centralised control.

Within the broader trajectory of digital transformation, synergistic partnerships assume a critical role in mediating technical capacity constraints, strengthening accountability mechanisms, and promoting inclusive policy outcomes. In the case of Makassar, the analytical premise is that both the configuration and the qualitative depth of these partnerships will be decisive in determining whether e-budgeting reforms evolve beyond compliance-driven digitisation and towards more substantively co-created, sustainability-oriented models of governance.

3.3 Digital literacy and capacity building as moderating/enabling factors

The framework further positions digital literacy and capacity building as key enabling and moderating conditions shaping the relationship between collaborative arrangements and the depth of co-creation (Fu and Sideris, 2024; Vissenberg et al., 2022). Elevated levels of digital literacy among institutional actors and citizens enhance the quality of interaction, expand the pool of participants capable of engaging with complex budgetary information, and facilitate more deliberative modes of co-design and joint evaluation (Kazanskaia, 2025; Syahrir et al., 2025). By contrast, uneven competencies and fragmented capacity-building initiatives can significantly dampen the potential gains of co-creation, reducing participation to largely symbolic or tokenistic forms (Mariu et al., 2025; Syahrir et al., 2025).

Building on the reviewed literature, digital literacy is conceptualised as a multidimensional capability encompassing technical proficiency, information-processing skills, critical judgement, and civic orientation. In the Makassar context, digital literacy and capacity building operate as contextual determinants that condition whether co-creation practices—formalised through participatory instruments such as Musrenbang and e-Musrenbang—can advance beyond the lower rungs of Arnstein’s ladder of participation. Where literacy and capacity remain limited, co-creation tends to be restricted to proposal submission within pre-defined institutional and technological formats; where they are more robust and broadly distributed, the scope for substantive engagement in problem framing, system design, and evaluative processes is correspondingly enhanced.

3.4 Operationalising co-creation in digital budgeting

To operationalise the theoretical constructs underpinning this study, the analysis integrates two complementary conceptual instruments: (i) the five co-creation capabilities articulated by Rösler et al. (2021) and (ii) the four meta-models of co-creation proposed by De Koning et al. (2016). The five capabilities—individuated empowerment, knowledge building and development, foundational interaction, coordinated integration, and communication—are employed to evaluate the organisational conditions that enable or constrain co-creation within Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms. Collectively, these dimensions facilitate a systematic appraisal of the city’s capacity to empower non-state actors, foster joint learning, align roles and objectives, integrate contributions across organisational boundaries, and sustain iterative communication and feedback.

The four meta-models, in turn, provide an analytical lens for situating co-creation within the digital budgeting process itself. The concept of the joint space of creation is used to identify which actors are meaningfully involved in key arenas of design and decision-making; the co-creation spectrum is applied to classify the degree of power sharing; the typology of co-creation distinguishes between lighter-touch arrangements—such as real-time self-service or mass customisation—and more intensive forms, including co-design and community design; and the process steps illuminate the extent to which co-creation is embedded across successive phases of problem framing, prototyping, implementation, and evaluation. By integrating these two tools, the framework moves beyond rhetorical invocations of co-creation and enables a structured, multidimensional assessment of Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms, addressing not only whether co-creation is present, but also where it occurs, with whom, at what depth, and under which enabling capability conditions.

3.5 Proposed analytical framework

Bringing these strands together, the study proposes an analytical framework in which strategic co-creation in digital budgeting is understood as the outcome of interactions between three core dimensions:

-

Collaborative governance arrangements – the formal and informal structures through which multiple actors engage in shared decision-making, as interpreted through co-creation theory and Arnstein’s ladder of participation.

-

The configuration and quality of synergistic partnerships – the extent to which multi-stakeholder alliances generate genuine synergy through complementary resources, joint learning, and shared accountability, or remain constrained by technocratic closure and centralised control.

-

The distribution of digital literacy and capacity – the degree to which state and non-state actors possess the skills and institutional support necessary to participate substantively in digital budgeting processes.

Rather than formulating testable hypotheses in a strict quantitative sense, the framework is used to guide qualitative analysis of the Makassar case. It specifies key dimensions—actor constellations, participatory depth, partnership dynamics, and literacy/capacity conditions—through which the promises and limitations of digital budgeting reforms are systematically examined. In subsequent sections, this framework is applied to the empirical material to illuminate how Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms enact, constrain, or reconfigure strategic co-creation and synergistic partnerships in the pursuit of sustainable urban governance.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research design

This study employs a qualitative case study design, which is particularly suited to exploring complex governance reforms where contextual factors and stakeholder interactions play decisive roles (Nong and Yao, 2019; Wasaf and Zhang, 2022; Zankina, 2020). By focusing on Makassar City, the research seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of how strategic co-creation and synergistic partnerships shape the implementation and outcomes of digital budgeting reforms. The case study approach allows for the triangulation of multiple data sources, including interviews with 15 informants directly involved in the design, implementation, and monitoring of e-budgeting, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of findings.

In order to explore how digital competencies shape the implementation of e-budgeting reforms, the interview guide explicitly included probes on perceived levels of digital literacy and organisational capacity among key stakeholders. Respondents were asked to reflect on their own ability, and that of their colleagues and constituents, to use digital budgeting platforms, interpret online budget information, and support others in navigating the system. Additional questions focused on the availability, frequency, and perceived effectiveness of training, mentoring, and other capacity-building initiatives related to digital tools. These topics were treated as a distinct analytical dimension during coding and analysis, enabling the study to examine how gaps in digital literacy and uneven capacity-building efforts condition the depth and quality of co-creation in Makassar’s digital budgeting reforms.

4.2 Case selection: Makassar City

Makassar City was selected as the focal case due to its pioneering role in adopting e-budgeting at the municipal level in Indonesia. Introduced as part of the city’s Smart City agenda in the mid-2010s, e-budgeting in Makassar represents both a technological innovation and a socio-political experiment in digital governance. The city provides a compelling context because of its ambitious fiscal posture—marked by increasingly expansive annual budgets—and the documented challenges of budget absorption, capital expenditure realization, and dependency on intergovernmental transfers. Furthermore, Makassar has been at the forefront of experimenting with multi-stakeholder collaboration, involving government agencies, the Regional People’s Representative Council (DPRD), civil society organizations, academia, and private-sector actors. These characteristics make Makassar a critical case for examining the intersection of digital reform, co-creation, and synergistic partnerships.

4.3 Data sources

The empirical foundation of this study rests on three main categories of data:

-

Documentary Evidence: This includes official reports, municipal regulations, audit opinions by the Supreme Audit Board (BPK), and policy documents issued by the Ministry of Home Affairs, particularly those mandating the use of the Sistem Informasi Pemerintahan Daerah (SIPD). Complementary local regulations such as the Peraturan Daerah Kota Makassar No. 2/2022 and Peraturan Walikota No. 97/2023 provide additional insights into local institutional frameworks.

-

Secondary Literature: Academic studies and international comparative research on co-creation, synergistic partnerships, and digital budgeting reforms supply the theoretical grounding for the analysis (Voorberg et al., 2015; Bryson et al., 2015; Ansell and Torfing, 2021).

-

Field-Based Insights: While primary interviews were not conducted for this study, empirical perspectives were drawn from previously published reports and expert analyses documenting the experiences of key actors in Makassar’s budgeting process, including municipal executives, legislators, civil society, and academic institutions.

4.4 Analytical framework

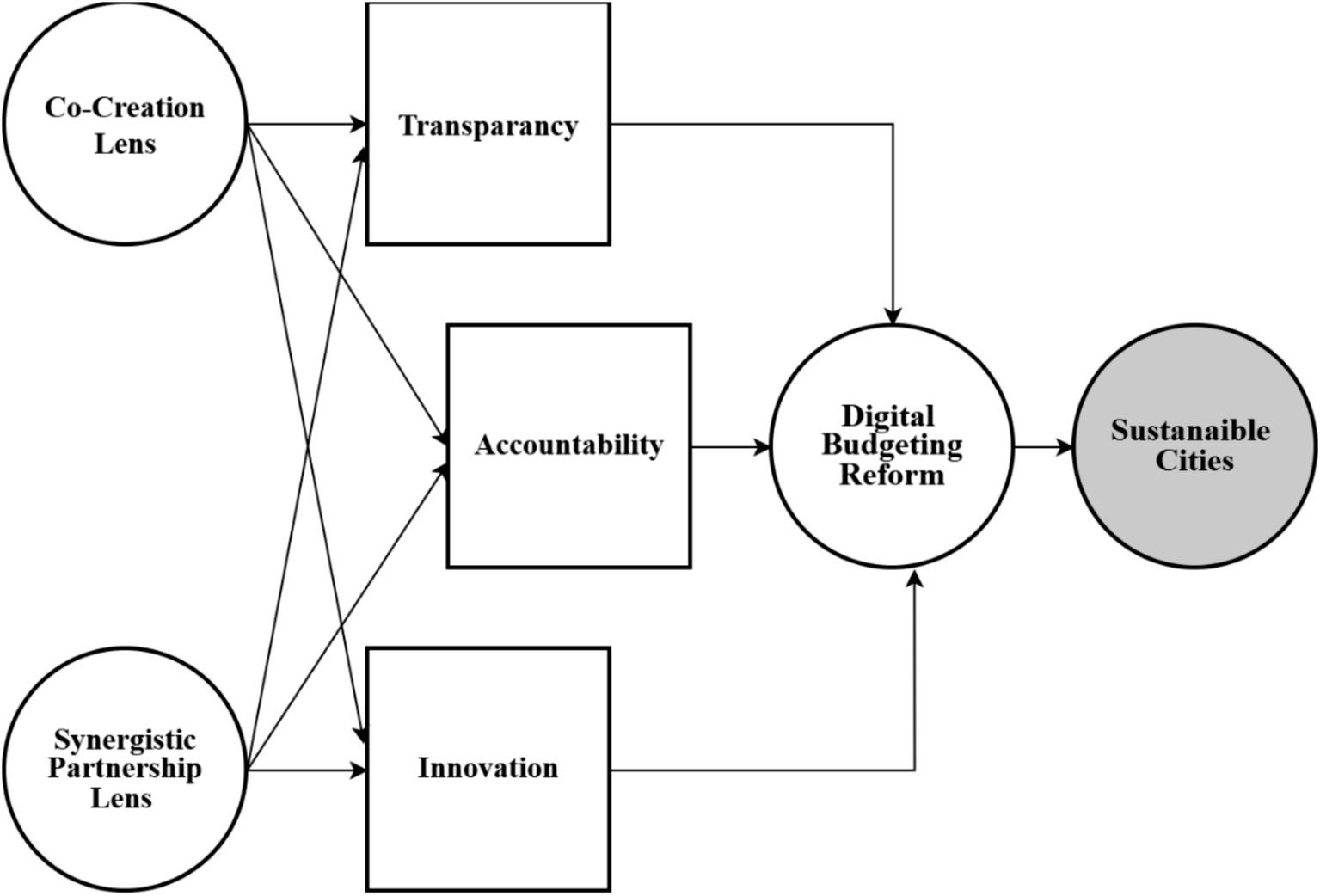

The analysis is guided by a two-pronged framework that integrates co-creation theory and the concept of synergistic partnerships, which is illustrated in Figure 1 under the title Analytical Framework of Co-Creation and Synergistic Partnerships in Digital Budgeting Reform (see conceptual diagram showing two interlinked pillars: Co-Creation Lens and Synergistic Partnerships Lens, connected to outcomes of transparency, accountability, and innovation) (Figure 3):

-

Co-Creation Lens: This dimension assesses the extent to which stakeholders are engaged not only as consultees but as active collaborators in the design, implementation, and evaluation of e-budgeting processes. It distinguishes between tokenistic participation and genuine co-production of governance outcomes (Kalvet et al., 2018a, 2018b; Lember et al., 2019)

-

Synergistic Partnerships Lens: This dimension examines how collaboration across government, civil society, academia, and private actors generates added value by pooling complementary resources and knowledge. It evaluates whether such partnerships are strategic (high-level and policy-oriented) or operational (day-to-day implementation and problem-solving).

Figure 3

Analytical framework of co-creation and synergistic partnership in digital budgeting reform for sustainable cities.

Data analysis employed thematic coding to identify recurring patterns across documents and reports, focusing on the interplay between technological reform and institutional collaboration (Chabok et al., 2025; Mian et al., 2025; Nasution et al., 2025). Triangulation was achieved by cross-referencing findings from multiple sources, thereby ensuring analytical rigor and reducing the risk of bias (Shahab et al., 2022; Treur et al., 2024).

By combining these methodological elements, the study seeks to uncover how digital budgeting reform in Makassar evolves not merely as a technological project but as a collaborative governance endeavor, shaped by the dynamics of co-creation and synergistic partnerships.

5 Results and discussion

This section presents empirical findings and interprets them through the lenses of strategic co-creation, synergistic partnerships, citizen participation and digital literacy, and digital governance resilience. To avoid excessive fragmentation and to maintain analytical coherence, the results are organised into four interrelated thematic sub-sections.

5.1 Strategic co-creation dynamics in e-budgeting

Makassar’s e-budgeting reforms originated in the mid-2010s under the broader Smart City agenda and have since been progressively institutionalised through socialisation, technical training, and local regulations (Mediaty et al., 2025; Nasrullah and Siraj, 2023). The integration of e-planning with e-budgeting aligned the RPJMD, RKPD, and APBD cycles, while full compliance with the national Sistem Informasi Pemerintahan Daerah (SIPD) followed the enactment of the Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation No. 70/2019 (Karima et al., 2021; Ngago and Sutra Dewi, 2024; Wisnu Pradana, 2022). Subsequent waves of reform focused on end-to-end digitisation—including non-cash transactions, electronic verification, and consolidated audit trails—which now constitute the backbone of Makassar’s emerging data-driven financial governance regime (Chairunnisa et al., 2020; David and Koney Evangeline, 2024; Nazran et al., 2024).

From a fiscal perspective, the city’s budget trajectory over 2019–2023 reveals expanding nominal budgets accompanied by uneven realisation—Table 1. Makassar Revenue Structure and Realization, 2019–2023 reports the composition and execution of revenues (in billion IDR), showing consistently high realisation rates for intergovernmental transfers (approximately 97–98 per cent) alongside more volatile performance of own-source revenue (PAD), fluctuating between roughly 80–94 per cent (Table 2). Makassar Expenditure (Total) and Realization, 2019–2023, summarizes total expenditure outturns, indicating that overall realisation dipped to about 76 per cent in 2021–2022 before recovering to approximately 86 per cent in 2023. These patterns are consistent with interview evidence that highlights mid-year absorption lags, procurement frictions, and year-end back-loading of disbursements, despite incremental improvements in internal audit follow-up enabled by digital trails.

Table 1

| Year | Item | Budget | Actual | % Actual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Own-Source Revenue (PAD) | 1,624.8 | 1,303.3 | 80% |

| Transfers | 2,274.3 | 2,213.0 | 97% | |

| Other Legitimate Revenue | 156.5 | 150.1 | 96% | |

| Total Revenue | 4,055.6 | 3,666.4 | 90% | |

| 2020 | Own-Source Revenue (PAD) | 1,144.2 | 1,078.3 | 94% |

| Transfers | 2,111.9 | 2,053.5 | 97% | |

| Other Legitimate Revenue | 213.1 | 191.8 | 90% | |

| Total Revenue | 3,469.2 | 3,323.7 | 96% | |

| 2021 | Own-Source Revenue (PAD) | 1,326.4 | 1,140.3 | 86% |

| Transfers | 2,046.9 | 1,979.5 | 97% | |

| Other Legitimate Revenue | 204.0 | 166.2 | 81% | |

| Total Revenue | 3,577.2 | 3,286.0 | 92% | |

| 2022 | Own-Source Revenue (PAD) | 1,715.0 | 1,410.8 | 82% |

| Transfers | 2,203.9 | 2,167.6 | 98% | |

| Other Legitimate Revenue | 67.5 | 8.9 | 13% | |

| Total Revenue | 3,986.4 | 3,587.3 | 90% | |

| 2023 | Own-Source Revenue (PAD) | 1,965.7 | 1,568.3 | 80% |

| Transfers | 2,508.1 | 2,448.1 | 98% | |

| Other Legitimate Revenue | 43.5 | 33.0 | 76% | |

| Total Revenue | 4,517.2 | 4,049.4 | 90% |

Makassar revenue structure and realization, 2019–2023 (billion IDR).

Notes (Revenue): Figures transcribed from internal BPKAD tables; minor rounding applied. Unit = billion IDR.

Table 2

| Year | Total expenditure – budget | Total expenditure – actual | % Actual |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 4,176.2 | 3,548.0 | 85% |

| 2020 | 3,706.9 | 2,968.6 | 80% |

| 2021 | 4,165.2 | 3,150.5 | 76% |

| 2022 | 4,700.7 | 3,549.1 | 76% |

| 2023 | 5,262.2 | 4,507.7 | 86% |

Makassar expenditure (Total) and realization, 2019–2023 (billion IDR).

Notes (Expenditure): Figures compiled from BPKAD; unit = billion IDR; minor rounding applied.

Makassar’s budgets expanded over 2019–2023 while realization remained uneven, with mid-year absorption lagging and disbursements bunching toward year-end. To contextualize these dynamics, Tables 1, 2 report revenue and expenditure outturns (billion IDR). Interviewees attribute under-execution primarily to fragmented early-cycle coordination and limited joint problem-solving on capital projects; recent pre-budget technical sessions convened by the Sekretaris Daerah and structured touchpoints with DPRD during KUA–PPAS were cited as emergent mitigations.

Against this background, interviewees pointed to emerging co-creation dynamics primarily within government and its close institutional partners. Pre-budget technical sessions convened by the Sekretaris Daerah and more structured touchpoints with the DPRD during the KUA–PPAS stages have created new spaces for joint problem-solving on capital projects and for aligning priorities across SKPD and legislative commissions. Officials described these forums as moments when “we sit together to see where the bottlenecks are and what must be prioritised,” suggesting a gradual shift away from sequential, file-based procedures toward more dialogic and interactive budget work. Read through the lens of co-creation theory (Besora-Moreno et al., 2025; Boateng et al., 2021; Morote et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2024; Tay et al., 2021; Vargas et al., 2022), these arrangements signal a partial transition from purely procedural compliance toward more interaction-centred governance, in which budgeting is treated less as a linear administrative sequence and more as an iterative, multi-actor process within the state apparatus (Dobbin et al., 2023; Lim and Lin, 2021; Vento, 2024).

De Koning et al. (2016) meta-models of co-creation provide a useful heuristic for situating Makassar’s trajectory. First, with respect to the joint space of creation, the empirical material indicates that this space is expanding across multiple interfaces—Executive–DPRD, Executive–CSOs, Executive–Academia, and Executive–Banks/Tech. Pre-budget sessions, thematic hearings, and technical coordination meetings bring different institutional actors into the same room, both physically and virtually. However, problem ownership within these arenas remains markedly asymmetrical: government actors, particularly the executive, continue to define the core issues, parameters, and procedural scripts, while other stakeholders are primarily invited to react within these pre-set frames. CSOs and academics, for example, are commonly positioned as providers of feedback or technical input rather than as equal partners in agenda-setting or rule design.

Second, along the spectrum of co-creation—from information and consultation to collaboration and partnership—most interactions observed in Makassar cluster between consultation and lower-order collaboration. The formal routing of legislative pokok pikiran (pokir) into planning and budgeting modules represents a meaningful step towards higher-influence collaboration between the executive and the DPRD, as legislative priorities are now more systematically encoded into digital planning workflows. Nonetheless, CSOs remain predominantly in a watchdog role, intervening from the outside through monitoring and critique rather than through guaranteed seats in structured co-design or co-governance forums. As several respondents from civil society noted, their engagement is often “by invitation” and topic-specific, rather than institutionalised through stable, co-decision-making arrangements.

Third, in terms of type configuration, the prevailing pattern can be characterised as “co-design lite.” Practice concentrates on the integration, prioritisation, and reconciliation of inputs—Musrenbang proposals, pokok pikiran, sectoral work plans—within an already established architecture of planning and budgeting systems. While this integrative work is non-trivial and does require cross-actor coordination, it falls short of deeper forms of co-creation in which users and stakeholders participate in designing the system’s architecture, service blueprints, or interaction logic. Institutionalised mass customisation (for example, neighbourhood-level budget dashboards that citizens can personalise) and real-time self-service monitoring tools remain nascent, often limited to experimental pilots or internal prototypes rather than fully operational, citizen-facing features.

Fourth, regarding process steps, the executive–legislative cycle has become more routinised in agenda-setting and option generation. Interviews with planners and legislative staff indicate clearer procedural sequencing for surfacing issues, assessing alternative allocations and iterating draft documents across the KUA–PPAS and APBD stages. However, iterative prototyping of digital tools and the joint evaluation of outcomes with non-state actors remain largely ad hoc. While workshops and focus groups are occasionally convened to introduce new features or solicit feedback, these activities have not been institutionalised as recurring stages within a formalised co-creation methodology. As one academic informant observed, engagement with universities is “often episodic—around a project or a seminar—rather than part of a structured, ongoing design and evaluation cycle” (academic interview, 2024).

Viewed through the composite lens of these meta-models, Makassar appears to have assembled many of the venues of co-creation without fully institutionalising power-sharing and iterative design. The city has established robust technical and procedural “rails” for e-budgeting and has begun to construct a joint space of creation among institutional actors—particularly between the executive and the DPRD, and to a more limited extent with CSOs, academia, and private partners. However, the depth and inclusiveness of co-creation remain constrained. Problem ownership is still largely state-centric; the intensity of collaboration rarely reaches the level of genuine partnership; and the modalities of co-creation tend to focus on integrating inputs into pre-existing architectures rather than questioning or redesigning those architectures themselves.

In summary, Makassar’s trajectory can be interpreted as one of emergent but still bounded co-creation. Within government, there is evidence of movement away from rigid, compliance-oriented budgeting towards more interactive, cross-actor problem-solving. Yet with respect to citizens and civil society, involvement in the design, governance, and evaluation of the digital budgeting system remains limited. This asymmetry—between relatively dense co-creation among institutional elites and shallow, input-focused participation for broader publics—forms a critical backdrop for the subsequent discussion of digital literacy gaps, platform dependency, and the conditions under which strategic co-creation can evolve from a largely declarative commitment into a more substantive, inclusive, and resilient mode of digital budgeting governance (Eckhardt et al., 2021; Lee and Lee, 2020; Rizki and Hendarman, 2024).

5.2 Limited depth of citizen involvement in digital budgeting co-creation

Local leaders in Makassar increasingly frame governance as a shared enterprise and have sought to expand the “joint space” of interaction through open information policies and continuous digital communication. In official discourse, Musrenbang, e-Musrenbang, and related forums are presented as emblematic instruments of co-creation, intended to connect citizen priorities to planning and budgeting modules. The Chair of the DPRD, for example, has publicly supported the idea of transforming Musrenbang from a largely ceremonial intake exercise into a more deliberative channel whose outputs—together with legislative pokok pikiran—are systematically captured in digital planning tools and carried forward into budget negotiations. However, the empirical material suggests that this ambition is unevenly realised across commissions and sectors, and that the depth of citizen involvement remains limited.

Across interviews, officials, community leaders, and CSO representatives converge on a description of participation that is heavily front-loaded at the proposal-submission stage. In practice, residents are invited to attend neighbourhood or sub-district meetings, discuss local issues, and formulate spending priorities, which are then entered manually by facilitators or uploaded by designated operators into e-Musrenbang and, ultimately, into the broader e-budgeting ecosystem. Once this initial phase is completed, citizens have very few opportunities to follow, let alone shape, how their proposals are filtered, prioritised, or translated into specific budget lines and system functionalities. Several interviewees described the process as a “one-way channel” that allows citizens to send inputs into the system but offers limited clarity regarding subsequent steps.

Interview data indicate that co-creation practices in Makassar remain unevenly distributed across actors, with non-state stakeholders largely positioned as contributors of inputs rather than as co-designers or co-evaluators. Although the joint space of interaction has expanded through formal forums and digital channels, substantive control over problem definition and system design continues to reside with government actors. An academic informant captured this asymmetry by noting that engagement with universities is “often episodic—around a project or a seminar—rather than part of a structured, ongoing design and evaluation cycle” (academic interview, 2024).

This pattern is reinforced by the routinisation of executive–legislative processes, where agenda-setting and option generation have become more procedurally ordered across the KUA–PPAS and APBD stages, yet without corresponding institutionalisation of iterative prototyping or joint evaluation with external actors. From the perspective of civil society, participation tends to be time-bound and invitation-based, limiting opportunities to influence system architecture, interface design, or prioritisation criteria. As one CSO informant described, their involvement remains largely “monitoring from the outside” rather than “sitting at the table when the system is being designed” (CSO interview, 2024).

Taken together, these accounts suggest that while collaborative interfaces are increasingly visible, co-creation in Makassar continues to operate at a “co-design lite” level, falling short of more embedded and reflexive models of shared design and evaluation.

The analysis reveals a structural decoupling between participatory rhetoric and the actual configuration of Makassar’s digital budgeting process, in which citizen contributions are largely channelled into pre-designed templates and standardised workflows. The rules governing aggregation, scoring, and integration with other inputs—such as legislative pokok pikiran and technocratic calculations—remain concentrated within the bureaucracy and its technical partners, reinforcing a division between front-end participation and back-end design. The complexity of SIPD, combined with tight regulatory timelines, further consolidates administrative and technical control over decision logics, interface design, and evaluative routines embedded in the platform, leaving citizens with limited leverage beyond articulating demands. Consequently, co-creation operates at a relatively superficial level: participation is largely confined to agenda-setting and does not extend to joint problem framing, iterative prototyping, system testing, or participatory monitoring and evaluation. From the perspective of Arnstein’s ladder of participation, observed practices cluster around tokenistic modes of information, consultation, and limited placation rather than partnership or shared control. Analytically, this configuration underscores that strategic co-creation in Makassar primarily serves inter-organisational coordination among governmental actors and a narrow circle of technical partners, while digital platforms risk institutionalising a form of “managed participation” that aligns with transparency narratives but falls short of substantive co-design and shared governance.

5.3 Synergistic partnerships and governance arrangements

The e-budgeting reforms are sustained by a dense network of actors whose roles and action repertoires are consolidated in Table 3. Roles and action patterns of key actors in Makassar’s e-budgeting reform. Municipal government (Mayor, BPKAD, Bappeda) acts as the primary driver of implementation: it designs local regulations, sets up infrastructure, integrates e-planning and e-budgeting, conducts outreach and technical training, and partners with regional banks to operationalise non-cash transactions. The DPRD functions both as a channel for citizen aspirations—through reses and pokok pikiran—and as an oversight body that aligns APBD decisions with these inputs and with Musrenbang outputs, gradually moving towards a more data-driven “Smart DPRD” model.

Table 3

| Actor | Role summary | Action patterns (illustrative) |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal Government (Mayor, BPKAD, Bappeda) | Primary driver of implementation; designs regulations; sets up infrastructure; leads modernization of public financial management. | Integrates e-planning and e-budgeting; conducts outreach and technical training; addresses resistance and technical issues through political commitment; issues Perwali/Perda as legal bases; partners with the regional bank for non-cash transactions. |

| DPRD (Legislature) | Channels citizens’ aspirations into the budget (pokok pikiran); exercises oversight to align the APBD with the results of Reses and Musrenbang. | Integrates Pokir into the system; shifts from closed-door bargaining to open collaboration; uses data-driven oversight; advances a “Smart DPRD” agenda for transparency and efficiency. |

| CSOs & Civil Society | Conduct social audits, advocate transparency, and participate in Musrenbang; act as independent watchdogs over the use of APBD. | Monitor and critique APBD through e-budgeting access; flag potential double-counting/mark-ups; demand open budget data/portal; participate in public consultations. |

| Academia & Experts | Provide conceptual analysis, evaluation, and system-improvement recommendations; lead education, research, and capacity building. | Conduct case studies and publications; serve as trainers/speakers; advise on technical integration (e.g., e-performance budgeting); partner in evaluation and benchmarking. |

| Private Sector (Technology, Banking, Media, Telco) | Provide technical and financial support, including IT infrastructure and non-cash transactions; media disseminate information. | Supply software and IT consulting; Bank Sulselbar supports non-cash transactions and online SP2D; media amplify transparency achievements; CSR programs support digital capacity building. |

Roles and action patterns of key actors in Makassar’s e-budgeting reform.

To consolidate observed roles and behavior, Table 3 summarizes functions and action repertoire across government, legislature, civil society, academia, and private actors.

Civil society organisations and broader civil society conduct social audits, advocate transparency, and participate in Musrenbang, acting as independent watchdogs over APBD use. Academia and experts contribute conceptual analysis, evaluation, and capacity building through research, training, and technical advice (for example on performance-based budgeting), while private sector actors—particularly IT vendors, banks, media, and telecommunications companies—provide critical infrastructure, non-cash payment rails, and public communication channels, including CSR-supported digital capacity initiatives.

These actor constellations operate within a multi-level regulatory and institutional framework summarised in Table 4. Hierarchy of E-Budgeting Regulations in Makassar City. At the national level, Presidential Regulations No. 95/2018 and No. 132/2022 establish the SPBE architecture, while Presidential Regulation No. 82/2023 accelerates digital transformation and integration of national digital services. Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation No. 70/2019 mandates SIPD as a single platform for planning, budgeting, reporting, and financial management, and Ministry of Finance regulations link transfer disbursement to electronic reporting and compliance with mandatory expenditure. Locally, Perda No. 2/2022 on regional financial management and Perwali No. 97/2023 (a 311-page operational blueprint) detail the system and procedures for regional financial management, consolidating earlier regulations and embedding SIPD at the core of Makassar’s e-budgeting ecosystem.

Table 4

| Regulation level | Number and year | Title | Core relevance to e-budgeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| National – Presidential Regulation | Presidential Regulation No. 95/2018 | Electronic-Based Government System (SPBE) | Establishes the legal foundation for digital governance, including financial management, and embeds transparency and accountability principles. |

| National – Ministerial Regulation | Minister of Home Affairs Regulation No. 70/2019 | Regional Government Information System (SIPD) | Mandates a single platform (SIPD) for planning, budgeting, reporting, and financial management across regions. |

| National – Presidential Regulation | Presidential Regulation No. 132/2022 | National SPBE Architecture | Provides the technical blueprint ensuring interoperability and integration of local e-budgeting with the national architecture. |

| National – Presidential Regulation | Presidential Regulation No. 82/2023 | Acceleration of Digital Transformation and Integration of National Digital Services | Prioritizes SPBE applications and accelerates integration of local digital services. |

| National – Ministerial Regulation | Minister of Finance Regulation No. 231/PMK.07/2020 | Electronic Submission of Regional Financial Information (IKD) | Requires electronic reporting of regional financial data; non-compliance subject to sanctions (withholding DAU/DBH). |

| National – Ministerial Regulation | Minister of Finance Regulation No. 24/2024 | Withholding/Reduction of Transfers for Non-Compliance | Strengthens fiscal discipline by linking transfer disbursement to compliance with mandatory expenditure. |

| National – Ministerial Regulation | Minister of Home Affairs Regulation No. 56/2021 | Regional Digitalization Acceleration Teams (TP2DD) | Establishes local teams to accelerate electronic financial transactions (ETPD), supporting the e-budgeting ecosystem. |

| Local – Regional Regulation (Perda) | Regional Regulation of Makassar City No. 2/2022 | Regional Financial Management | Provides the local legal umbrella for financial management; aligns local governance with SPBE and SIPD mandates. |

| Local – Mayor Regulation (Perwali) | Mayor Regulation of Makassar City No. 97/2023 | System and Procedures of Regional Financial Management | Operational blueprint (311 pages) detailing procedures for e-budgeting via SIPD; consolidates and repeals previous Perwali. |

| Local – Annual Regional Budget (APBD) Regulation | e.g., Perda No. 5/2020 (APBD 2021); Perda No. 4/2023 (Revised APBD 2023); Perda No. 8/2024 (APBD 2025) | Regional Budget (APBD) | Legally binding annual budget outputs; operationalized via Mayor Regulations on APBD elaboration that translate SIPD data into official allocations. |

Hierarchy of e-budgeting regulations in Makassar city.

At the national level, Presidential Regulations No. 95/2018 and No. 132/2022 established SPBE architecture; Presidential Regulation No. 82/2023 accelerated digital transformation. The Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation No. 70/2019 mandated SIPD adoption. Locally, Perda 2/2022 and Perwali 97/2023 provide the legal scaffolding for implementation.

From a theoretical standpoint, these arrangements correspond to what the literature terms synergistic partnerships, which create value by pooling heterogeneous resources and authority across organisational boundaries. The Makassar case exhibits several features of such synergy:

-

(i) a strong executive centre that convenes pre-budget technical reviews and aligns SKPD with DPRD milestones;

-

(ii) robust financial rails and traceability via KKPD and real-time bank integrations;

-

(iii) an interoperability backbone stewarded by the ICT unit that reduces transaction costs across agencies and vendors;

-

(iv) growing legislative use of system data in KUA–PPAS and APBD deliberations; and

-

(v) knowledge and social accountability contributions from academia, CSOs, media, and banking partners.

At the same time, the findings reveal an operational “synergy gap.” CSOs are rarely embedded in module or KPI co-design; academic memoranda of understanding seldom translate into joint prototyping of tools or dashboards; and private actors primarily contribute technological infrastructure rather than participating in policy or governance co-design. Benchmarking Makassar’s capability profile for co-creation shows that: individual empowerment beyond executive nodes is uneven; structured joint learning with CSOs and citizens is limited; shared design charters and service blueprints are rare; linkages with civic-tech tooling are nascent; and bi-directional feedback loops that systematically trigger design changes have yet to be institutionalised. This configuration helps explain why transparency and standardisation have advanced more rapidly than participatory depth, and why the city’s co-creation architecture remains vulnerable when confronted with external shocks to the national platform.

5.4 Citizen involvement and digital literacy gaps

On the participatory frontier, city leaders in Makassar increasingly portray governance as a shared enterprise and have sought to enlarge the “joint space” of decision-making through open information policies and digital communication channels. Instruments such as Musrenbang, e-Musrenbang, and various thematic consultative forums are formally presented as arenas in which citizens, community leaders, and civil society organisations (CSOs) can articulate spending priorities and feed them into planning and budgeting modules. The Chair of the DPRD, for instance, has advocated a substantive reorientation of Musrenbang from a largely ceremonial intake exercise towards a more deliberative process whose outputs—together with legislative pokok pikiran—are systematically captured in planning modules and carried forward into budget formulation.

Empirically, however, the material collected for this study reveals a more constrained pattern of participation. Citizen involvement in Makassar’s digital budgeting processes remains largely confined to the front-end submission of proposals. Residents are invited to attend neighbourhood or sub-district meetings, identify and rank local priorities, and channel these proposals into the e-Musrenbang interface, often with the assistance of facilitators or village-level operators. Once submitted, however, citizens have very limited opportunities to influence how these proposals are filtered, aggregated, or translated into specific budget lines, system functionalities, or dashboard features. Interviewees across government and community groups converged on the description of a process in which citizens’ contributions “enter the system” but are then processed within administrative and technical domains to which they have little or no access.

Interview accounts consistently portray citizens as “input providers” rather than co-designers or co-evaluators, indicating that participation is largely confined to upstream submission while downstream design authority remains concentrated within administrative and technical actors. As one sectoral planner explained, “People come to Musrenbang or submit proposals online, but the technical design of the system—the modules, the menus, the dashboards—is handled by the government and our IT partners” (planner interview, 2024). From the standpoint of community actors, engagement becomes increasingly opaque once proposals are lodged, with limited visibility over processing rules, selection decisions, or opportunities for deliberative follow-up; a community representative noted, “After we send our proposals, we do not really know how they are processed, which ones are accepted, or whether there is any follow-up discussion with us” (community interview, 2024). Civil society respondents echoed this assessment, suggesting that while advocacy priorities may occasionally surface in draft documents, CSOs are seldom invited into structured sessions to review interface changes, test new functionalities, or co-develop prioritisation criteria. As one CSO activist put it, their role remains “watching from the outside” rather than participating in the design of the rules and tools that ultimately structure e-budgeting (CSO interview, 2024).

Taken as a whole, these findings suggest that the co-creation framework invoked in Makassar’s e-budgeting reforms remains largely nominal rather than substantive. Citizen involvement is predominantly concentrated at the front end of the policy cycle, particularly during agenda articulation, and rarely extends into deeper phases such as joint problem definition, iterative system prototyping, user testing, or participatory monitoring and evaluation. Consequently, the rhetoric of co-creation obscures a constrained mode of engagement in which citizens are invited to express preferences within pre-configured institutional and technological settings, while substantive design authority over the system remains elsewhere. Viewed through Arnstein’s ladder of participation, these practices are best characterised as clustering at the lower rungs of information and consultation, with only sporadic progression towards placation, and falling well short of partnership or shared control.