Abstract

The study aimed to systematically assess community-level risk perceptions and informal resilience capacities concerning urban fluvial hazards within Peshawar, Pakistan. The research addresses the global acceleration of urban flood hazards, a phenomenon increased by unregulated urban expansion and anthropogenic climate change. Methodologically, the study adopted a qualitative inquiry and the study was framed in an Interpretive Phenomenological Approach, utilizing the Socio-Ecological Systems (SES) framework as its theoretical construct. The SES framework operationalizes the local context by integrating the core components of risk (hazard, vulnerability, and exposure) and resilience (defined by anticipatory, adaptive, and restorative capacities) within the paradigm of the human-environment relationship. Data collection employed a multi-modal strategy including nine Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), 15 Key Informant Interviews (KIIs), and five In-Depth Interviews (IDIs), all conducted via purposive sampling. The empirical data reveal that local conceptualizations of urban flooding are primarily attributed to shifts in precipitation regimes and a spectrum of anthropogenic interventions. These interventions include uncontrolled informal settlements (encroachment), faulty urbanization, elevated groundwater tables and deficiencies in critical infrastructure, with all factors being aggravated by pervasive governance deficits. The resultant vulnerability is characterized as multidimensional vulnerabilities extending across socio-economic, physical, environmental and motivational axes. Parallel to it, communities demonstrate emergent resilience mechanisms, specifically manifesting as self-organized early warning systems and adaptive structural modifications such as elevated building plinths. The study suggests that effective urban flood risk management necessitates a paradigm shift from the silos-based top-down governance model toward a holistic, risk-informed urban planning framework. Such transition requires support from institutional reforms and formalized community engagement to effectively use indigenous knowledge and local capacities, thereby adding the system’s inherent capacity to absorb, adapt and transform in response to hydrometeorological stressors.

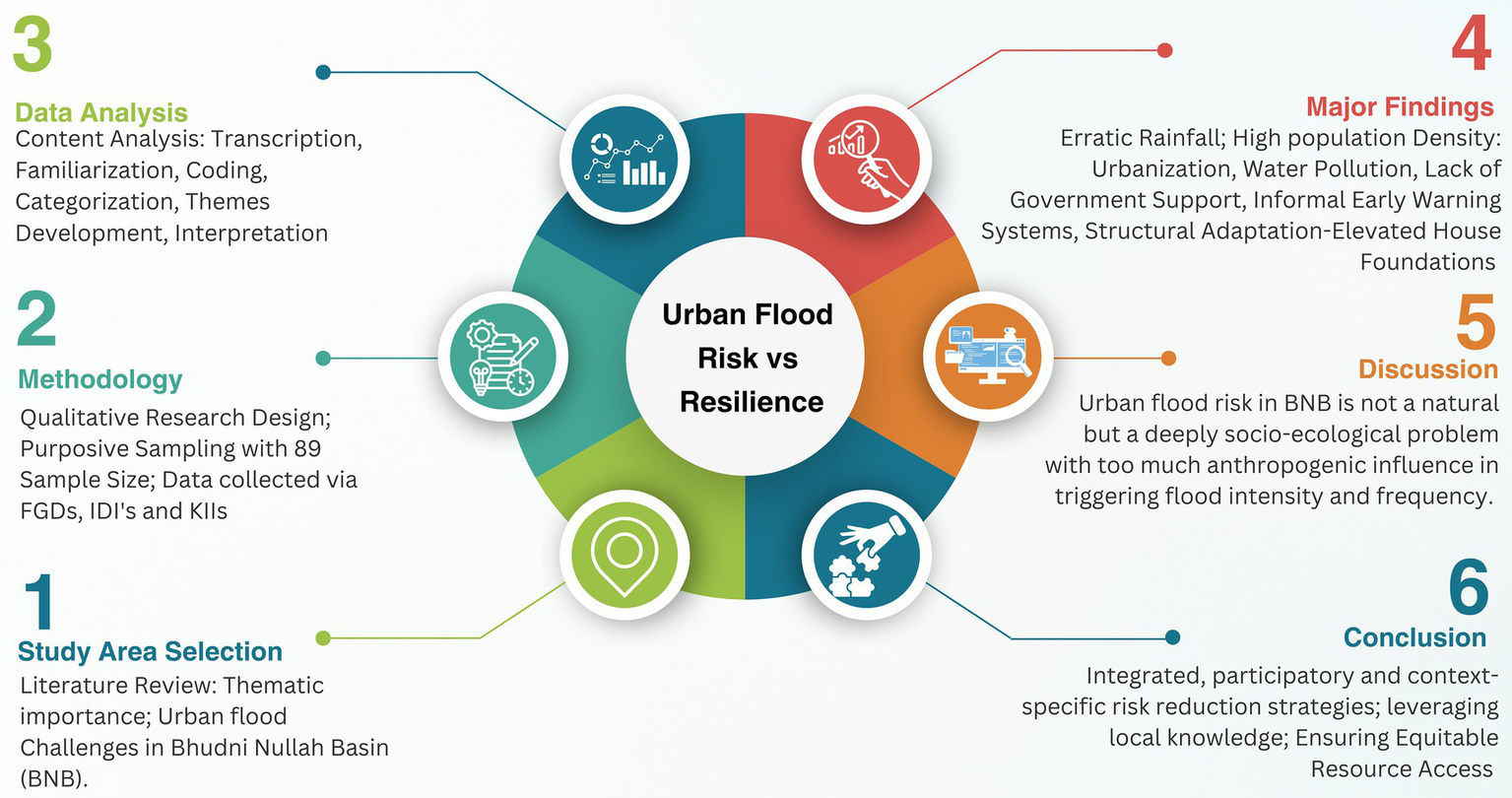

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Floods are one of the catastrophic global disasters, resulting in widespread impacts on people, properties, agriculture, livelihoods and critical infrastructure (Wang et al., 2024; Deen, 2015). The severity and intensity of urban flooding are increasingly exacerbated by the synergistic pressures of accelerating climate change and rapid urbanization (Mekkaoui et al., 2025; Dharmarathne et al., 2024; Das et al., 2024). Climate change induced enhanced precipitation often overwhelms existing drainage infrastructure, especially in urban areas where extensive impermeable surfaces reduce natural absorption (Bagheri and Liu, 2025). Consequently, urbanization not only creates new flood hazards through altered hydrology and reduced natural absorption but also surges exposure by concentrating vulnerable populations and assets. This dual role results in a compounded urban risk, portraying a systemic vulnerability inherent to the urban fabric that demands specific attention (Ibrahim et al., 2025; Neves, 2024; Iftikhar and Iqbal, 2023a, 2023b; Ali et al., 2015).

Pakistan is vulnerable to frequent flood disasters, leading to substantial human casualties and significant economic losses (Ibrahim et al., 2024; Tayyab et al., 2024). These events have been severely worsened by anthropogenic climate change, a phenomenon demonstrated by the catastrophic floods witnessed in 2010 (affected 20 million people with 9 billion USD direct damages) and 2022 (affected 33 million people with 40 billion USD direct damages) (Hussain A. et al., 2023; Rebi et al., 2023; Ullah et al., 2021). These floods were marked by an unprecedented eight cycles of monsoon rains (exceeding the typical three to four cycles), which resulted in widespread riverine, flash and urban floods across various provinces of Pakistan (PMD, 2022a; PMD, 2022b). The existing vulnerabilities are ingrained in the unplanned urbanization, poor governance and poverty, which have been further intensified by the increased frequency and intensity of monsoon rains (Jan et al., 2025; Jan et al., 2024; Ali et al., 2022). The intensity of flood hazards in Pakistan does not solely determine the impact of climate change rather it is significantly shaped by pre-existing societal vulnerabilities, classifying it as a complex socio-environmental problem (Rahman et al., 2025b; Khan et al., 2024; Ali et al., 2024; Khan and Jan, 2015). In Pakistan, research indicates that floods are not merely hydro-meteorological events but the complex result of climate change interacting with socio-economic, governance, and environmental systems (Hussain et al., 2025; Rahman et al., 2025a; Ali et al., 2022). In all types of flooding, urban flooding poses an intensifying and serious challenge in Pakistan, causing widespread destruction and fatalities (Rana and Routray, 2018). Repeated urban flood events have impacted prominent cities such as Lahore, Karachi, Quetta, Peshawar, Islamabad, and Rawalpindi in recent years. The urban floods that hit Lahore in 2014, 2016, and 2019, for example, resulted in deaths, injuries, and a breakdown of normal life, alongside damage to roadways and real estate (Zia and Shirazi, 2019; Hanif, 2019). Karachi experienced severe urban flooding across the entire city following an extraordinary rainfall event in 2020 (which saw 367.0 mm at Karachi Airport, 436.0 mm at Masroor, and 588.0 mm at Faisal) (Iftikhar and Iqbal, 2023a). Likewise, episodes of urban flooding in Peshawar in 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2022 and 2025 destroyed homes and roads and caused deaths. These incidents were often a consequence of the River Kabul and Budhni Nullah overflowing and backing up (Tayyab et al., 2021).

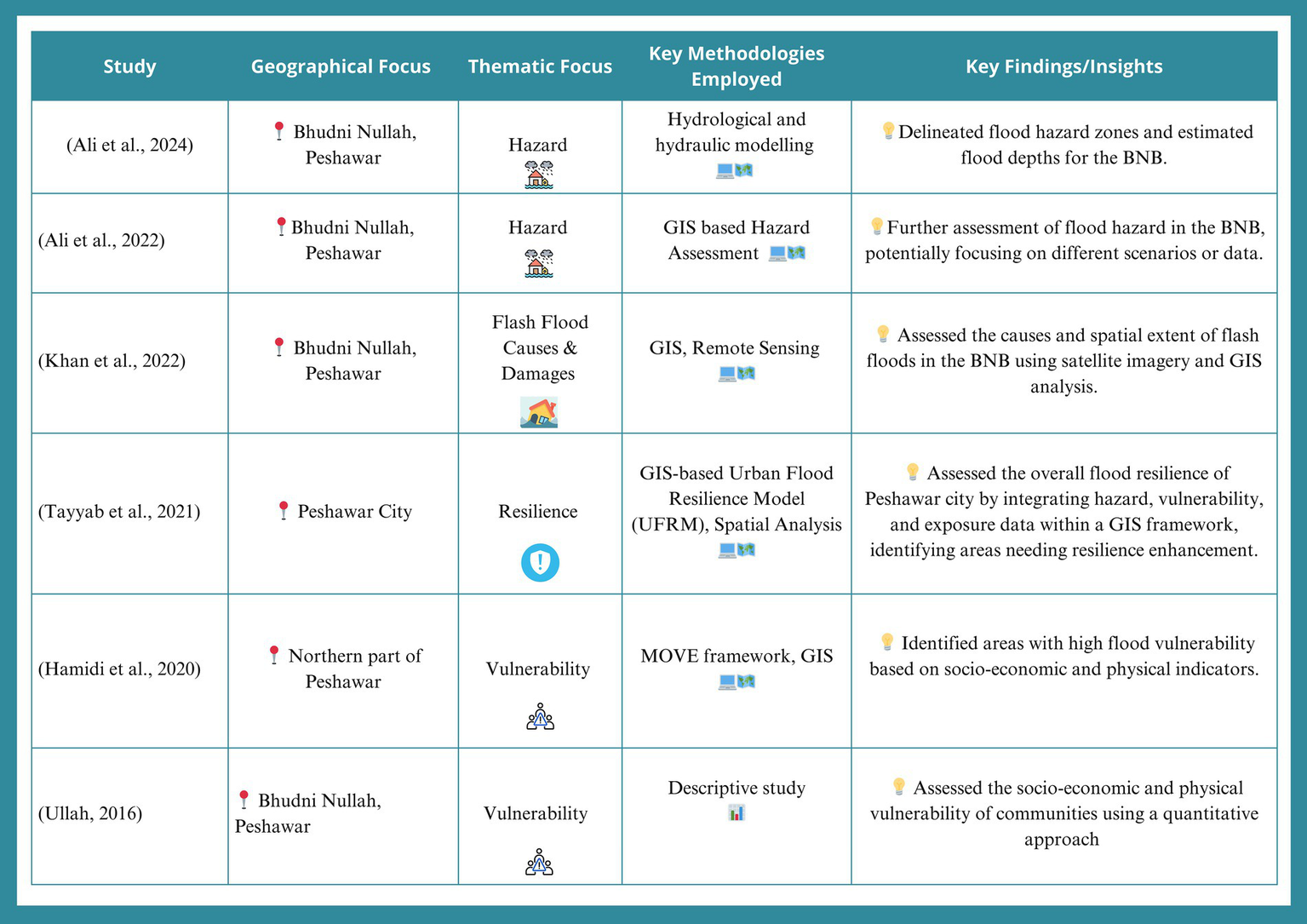

With a population of 4.76 million, Peshawar is among the most populous urban centers in Pakistan and serves as the historic capital of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Peshawar demonstrates the complex interplay of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure, highlighting a critical need for enhanced resilience (Ullah, 2016). The consistent scholarly focus on flooding within the city points to its high flood risk and establishes it as a pertinent case study for examining the application of diverse flood assessment methodologies in a specific urban context. Recently, several studies have assessed flood hazards, vulnerabilities, and risk across Peshawar with different assessment techniques (Figure 1). These studies have only focused on either the hazard, risk, or vulnerability aspects with the application of geospatial technologies, but they have not integrated both risk and resilience in their studies. For example, Hamidi et al. (2020) conducted a detailed flood vulnerability assessment of the northern part of Peshawar, utilizing the MOVE (Meaning-Making, Observations, Viewpoints, and Experiences) framework and presented a spatial analysis of flood vulnerability. The study exclusively focused on assessing social, economic and physical vulnerability through community perception data but overlooked the motivational, environmental and governance aspects. Ali et al. (2024) and Ali et al. (2022) used hydrological and hydraulic modelling techniques to delineate flood-prone areas in BNB Peshawar. These two research studies only focused on the hydrological modelling with no inclusion of the social parameters or exposure data. Khan I. et al. (2022) and Khan S. N. et al. (2022) assessed the causes, spatial extent and associated damages of flash floods in this critical area. The emphasis was entirely focused on the spatial extent of the flood without the inclusion of the cascading impacts of floods. Furthermore, Tayyab et al. (2021) and Tayyab et al. (2024) provided a GIS-based urban flood resilience assessment within a GIS framework. The GIS-based resilience study uses secondary data available from various sources but does not address how the local community adapts, adjusts, and transforms before, during and after disasters. The variety of methodologies employed in these case studies including hydrological modelling, vulnerability frameworks and GIS-based assessment allows for a valuable comparative understanding of their respective strengths with several limitations in addressing different aspects of urban flood risk. Specifically, most studies have concentrated on discrete aspects of flood risk, including hazard, vulnerability and resilience, often relying on secondary data sources. This fragmented approach underscores the need for a more comprehensive and integrated research framework that incorporates primary data and examines the complex interrelationships between risk and resilience. Review of the already published work presented above indicates an incoherent understanding of flood risks in Peshawar, emphasizing the need for an integrated assessment that considers the interplay between hazard, vulnerability, exposure and resilience within the city’s distinct socio-geographical context. Besides, these studies have only focused on the technical parameters, overlooking the significance of the perspective of the flood-vulnerable communities and stakeholders involved in urban flood risk management. The fragmented character of earlier research emphasizes the need for integrated studies that must capture local perspectives directly through community engagement while addressing hazard, risk and resilience (Arosio et al., 2024; Sadia et al., 2016). This is also necessary for local resilience-building against disasters (Jan et al., 2025; Rahman et al., 2023a). A comprehensive approach, therefore, is necessary to integrate local insights and community views to establish successful flood risk reduction and resilience-building initiatives (Shah and Ai, 2024). The present study aims to conduct a parallel investigation of risk and resilience to identify the hazard, vulnerabilities, exposure, capacities, risk, and resilience.

Figure 1

Summary of urban flood hazard, risk and resilience assessment methodologies used in Peshawar case studies (Ali et al., 2024; Tayyab et al., 2024; Khan I. et al., 2022; Khan S. N. et al., 2022; Tayyab et al., 2021; Hamidi et al., 2020; Ullah, 2016).

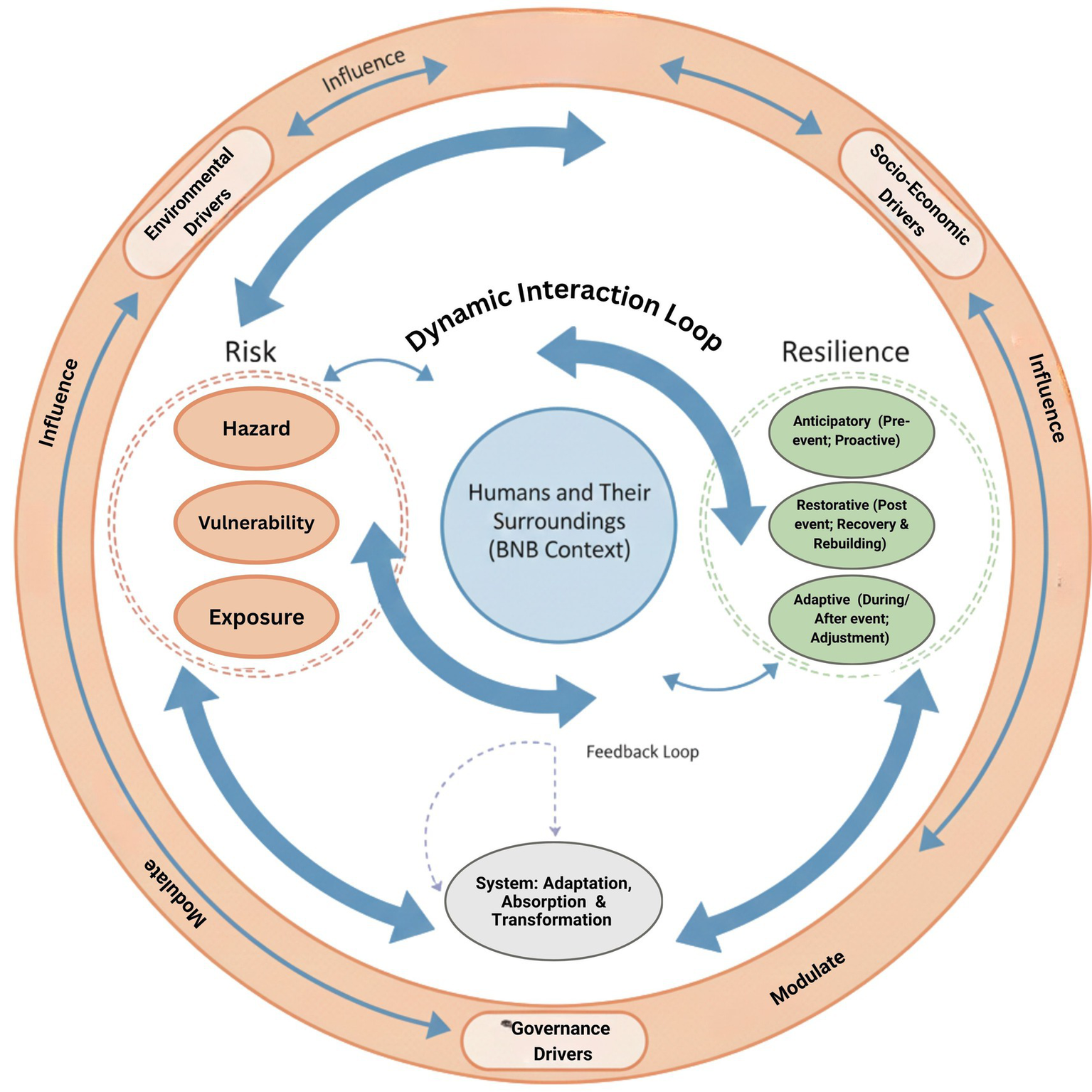

This study has employed the Socio-Ecological Systems (SES) framework as a theoretical framework to capture the local perspective on urban flood risk and resilience in BNB. It incorporates the concepts of risk (hazard, vulnerability, exposure) and resilience (anticipatory, adaptive, and restorative) in the context of interactions between humans and their surroundings (Hanf et al., 2025). The SES framework provided a conceptual link between the social and technical aspects of flood risk and generated interventions that are socially relevant and scientifically sound and sustainable. Therefore, from a community perspective, the SES framework systematically guides the investigation toward identifying the intricate socioeconomic, environmental and governance-related drivers (Peck et al., 2022). Within the SES framework, resilience refers to a community’s comprehensive ability to adapt, absorb and transform in response to flood events (Folke, 2006). This includes anticipatory capacities (proactive measures like early warnings), adaptive capacities (dynamic adjustments during or after an event) and restorative capacities (effective recovery and rebuilding) (Tariq, 2023). Critically, this perspective acknowledges that resilience often stems from local ingenuity and collective action (Hanf et al., 2025). In Figure 2, the framework outlines the urban flood as a dynamic interaction loop between risk, resilience, and the central humans and their surroundings (BNB Context), all influenced by external drivers. Risk, defined by Hazard, Vulnerability, and Exposure, acts upon the BNB Context, which in turn determines the system’s capacity for Resilience, categorized as Anticipatory (proactive), Adaptive (adjustment during/after the event) and Restorative (post-event recovery). The performance of Resilience capacity dictates the system’s final state of Adaptation, Absorption, and Transformation. The entire cycle is continuously shaped by Environmental, Socio-Economic, and Governance Drivers, which Influence Risk and Modulate Resilience. The process is closed by a Feedback Loop where the system’s transformative outcome directly revises the initial Risk components, highlighting the dynamic and continuous nature of urban flood risk management and system evolution. The study seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

How do the residents of BNB perceive the primary drivers of urban flood, multidimensional vulnerabilities, and specific socio-economic and physical impacts?

-

What are the key characteristics and mechanisms of informal, community-level resilience that emerge in response to urban flooding, and how can these be integrated into a formal, risk-informed urban planning framework?

Figure 2

Socio-ecological systems (SES) framework of the study.

Specific objectives of the study are to systematically assess the community-level risk perceptions of urban flooding by investigating the causes and their conceptualization of multidimensional vulnerabilities; and to identify and characterize the informal resilience capacities within affected communities, including self-organized early warning systems and adaptive structural modifications using the SES framework.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study area: BNB, Peshawar

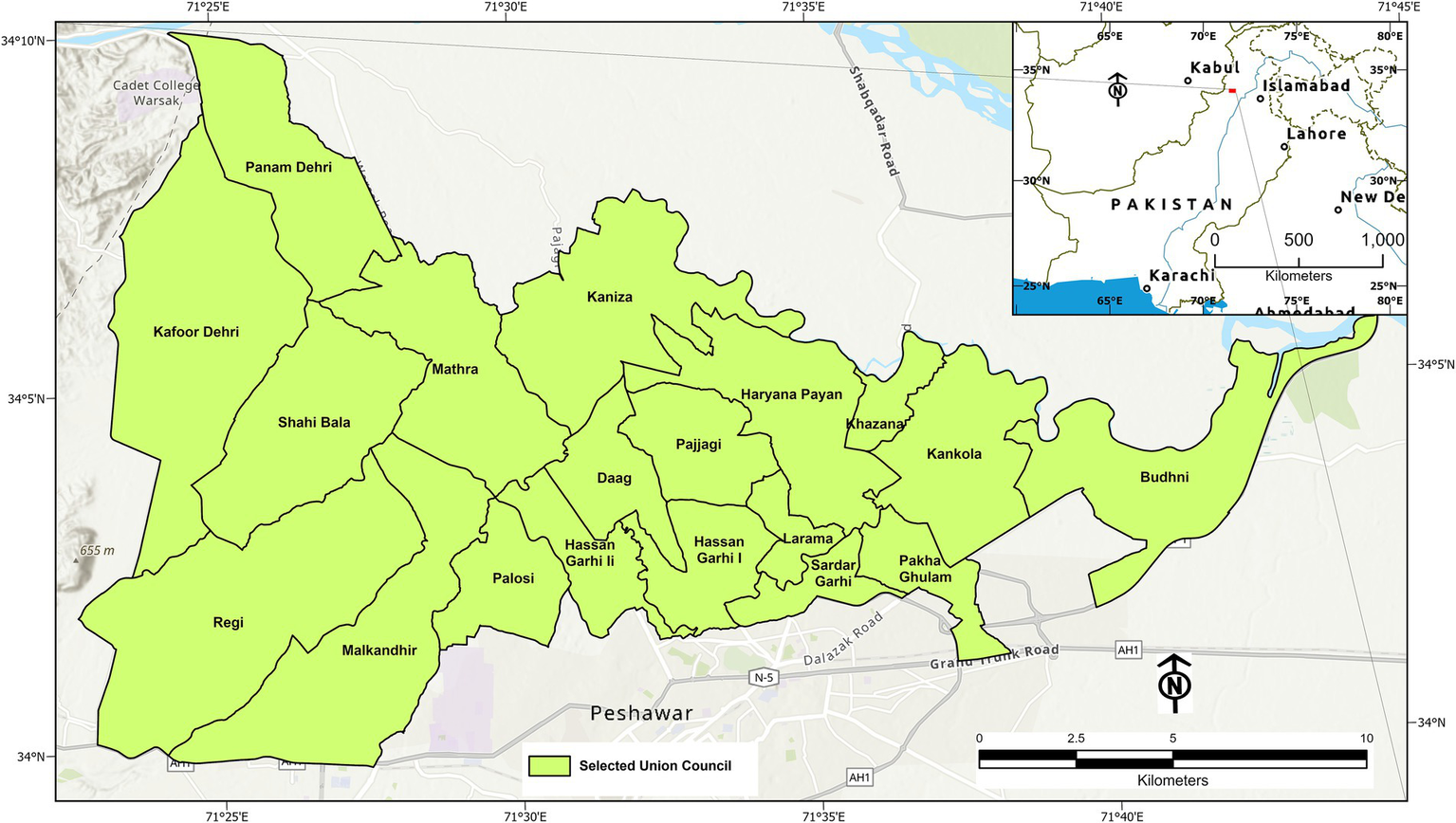

This study was conducted in the Bhudni Nullah Basin (BNB), Peshawar, Pakistan. Peshawar, a valley-shaped district designated as “Very High Risk” for disasters by the National Disaster Management Authority (Government of Pakistan, 2024). The BNB covers 272 km2 (Ali et al., 2022) and is traversed by the Bhudni Nullah, which spans 38 km (up to 122 km including tributaries), bordering 84 settlements with a population of over 922,000 (Figure 3) (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023; Khan I. et al., 2022; Khan S. N. et al., 2022). Peshawar’s basin-like topography is the primary natural driver of chronic urban flooding, as water naturally channels from surrounding highlands into the Nullah. The flood risk is intensified by intense rainfall, upstream cloud-bursting, and critical anthropogenic factors (Ali et al., 2022). Further exacerbating this is the proximity of the Warsak Dam, which increases waterlogging and reduces stormwater absorption (Ullah, 2016). Peshawar is the only urban center in the region located in the foothills that receives flooding. The interplay of different rivers and the tributaries produces secondary blocking of natural flow, creating a ponding-like condition. The area has a severe history of destructive events, including the 2002 flash flood, the 2010 torrential flood (affecting over 200,000 people), and the 2008 urban floods (claiming 41 lives) (Government of Pakistan, 2022; Asian Development Bank and World Bank, 2010). Recent floods, such as the 2025 have caused major socioeconomic losses and dangerous cascading effects, like disease outbreaks (Jan et al., 2025). Despite this clear pattern, communities widely perceive a profound lack of effective government mitigation and reliable early warning systems (Ali et al., 2024).

Figure 3

Location and administrative map of the Bhudni Nullah Basin (BNB), Pakistan.

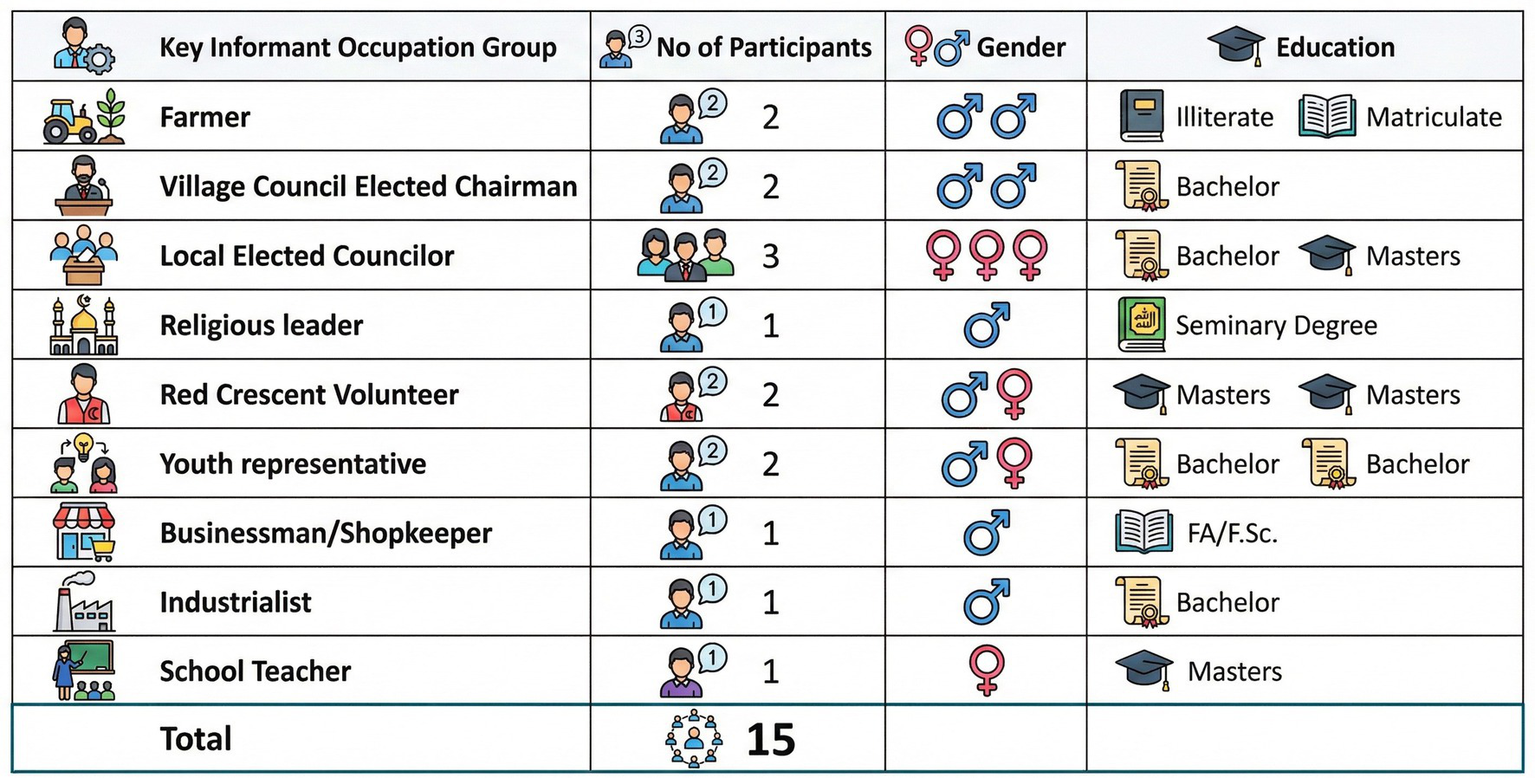

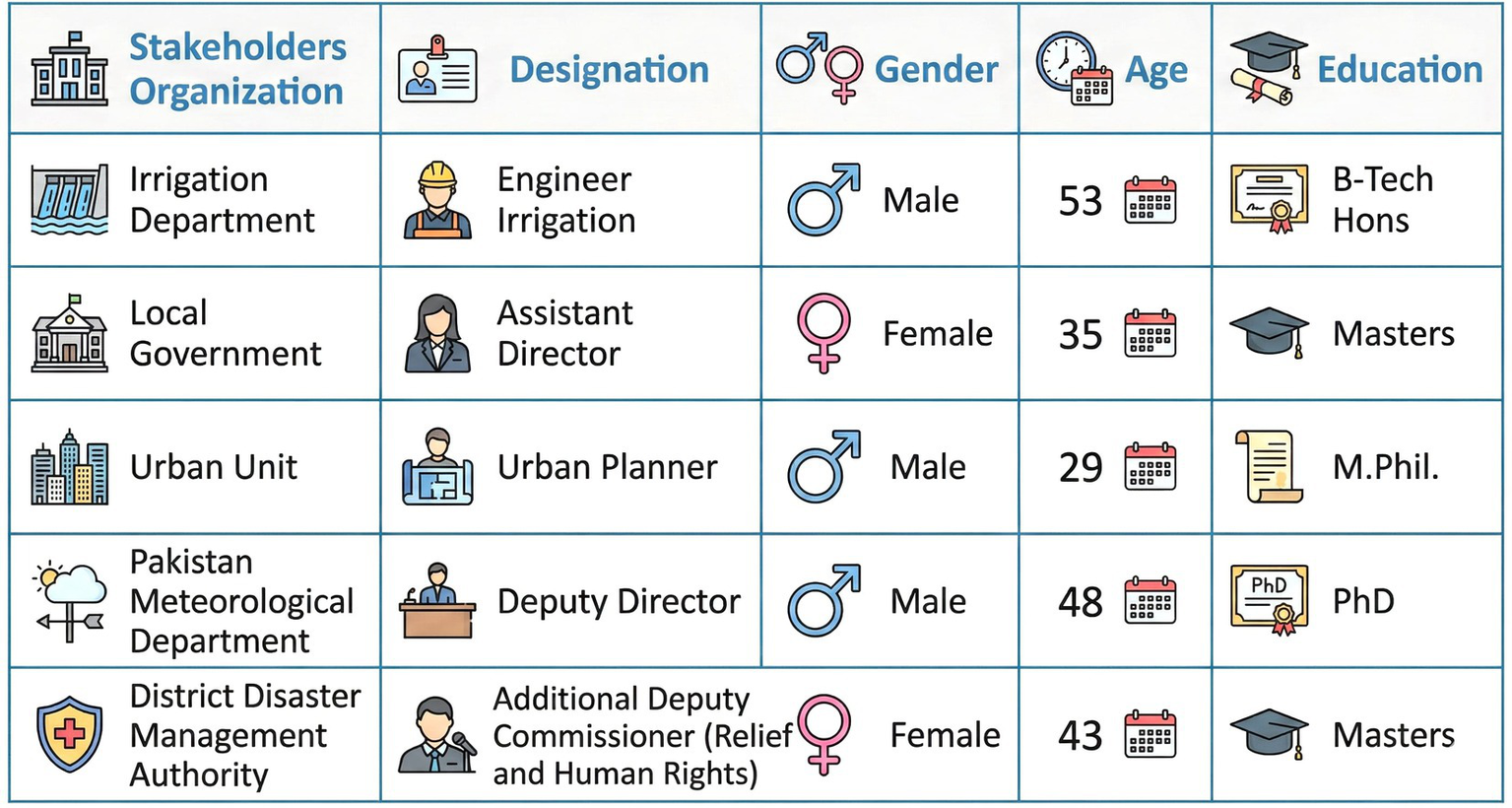

2.2 Research design: a qualitative approach

The study is qualitative in nature and has been framed under the interpretive phenomenological approach to explore the perception and lived experiences of urban flood risk and resilience among the inhabitants of BNB. This research approach is chosen for its suitability in examining complex social phenomena, enabling us to capture primary data directly from participants’ perspectives (Celebi Cakiroglu et al., 2025; Robinson and Williams, 2024). The study facilitates an in-depth exploration of the subjective realities of hazard, vulnerability, risk, and coping mechanisms. Keeping in view the qualitative nature of the study, Focus Group Discussion (FGD), Key Informants Interview (KII) and In-depth Interview (IDI) were used as tools of data collection. These tools were selected due to their wide applicability in qualitative research as suggested by Mwilongo (2025), Hussain et al. (2025), Shisanya and Obando (2024), Asamoah et al. (2024), Iqbal et al. (2025), and Creswell and Creswell (2018). The FGD and KII checklists were translated into the Pashto language for field-based data collection, taking into account the local literacy rate and technical jargon specific to the research and disaster management field. Data was collected in the Pashto language from the participants of the FGDs and KKIs. The high level of literacy of the IDI participants enabled the researchers to collect data in the English language. We employed purposive sampling techniques to select the study population. Compared to other sampling techniques and as per peer-reviewed literature recommendations (such as Ahmad and Wilkins, 2025; Ahmed, 2024; Stratton, 2023; Creswell and Creswell, 2018), the purposive sampling method guided the selection of participants who directly experienced urban flooding and had expertise in governance and disaster management, allowing for a holistic view through data triangulation. The sample composition included 69 community members participating in 9 FGDs (see Table 1), 15 KIIs with key community leaders and stakeholders (Figure 4) and 5 IDIs with government officials from relevant departments (Figure 5). The composite sample size was 89 participants. Out of the total sample size, i.e., 69 were male and 20 were female. Due to cultural restrictions, women are not allowed to interact with male researchers; therefore, the services of female data enumerators were used to capture the perspective of female study participants. This comprehensive and multi-layered data collection approach captured both individual and collective experiences as well as top-down and bottom-up views, ensuring a critical understanding of urban flood dynamics. Primary data through FGDs was collected from January to February 2025. KKIs were conducted in April 2026 and IDIs were conducted in May 2025. The data was collected with the perspective of floods of 2008, 2010, 2014, and 2022. Since the 2025 floods occurred after the data collection process was completed. The researchers revisited the field in August 2025 and validated the results again in the perspective of the 2025 floods.

Table 1

| Name of UC | Number of participants in each FGD | Nature of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Sheikh Abad | 11 | Male |

| Darmangi | 7 | Male |

| Pajaggi | 6 | Female |

| Hassan Garhi | 7 | Male |

| Haryana | 8 | Male |

| Kankola | 6 | Male |

| Bhudni | 9 | Male |

| Larama | 8 | Male |

| Shahi Bala | 7 | Female |

| Total | 69 (Male = 56; Female = 13) |

Sample size of the focus group discussion.

Figure 4

Sample size of the key informant interviews.

Figure 5

Sample size of the in-depth interviews.

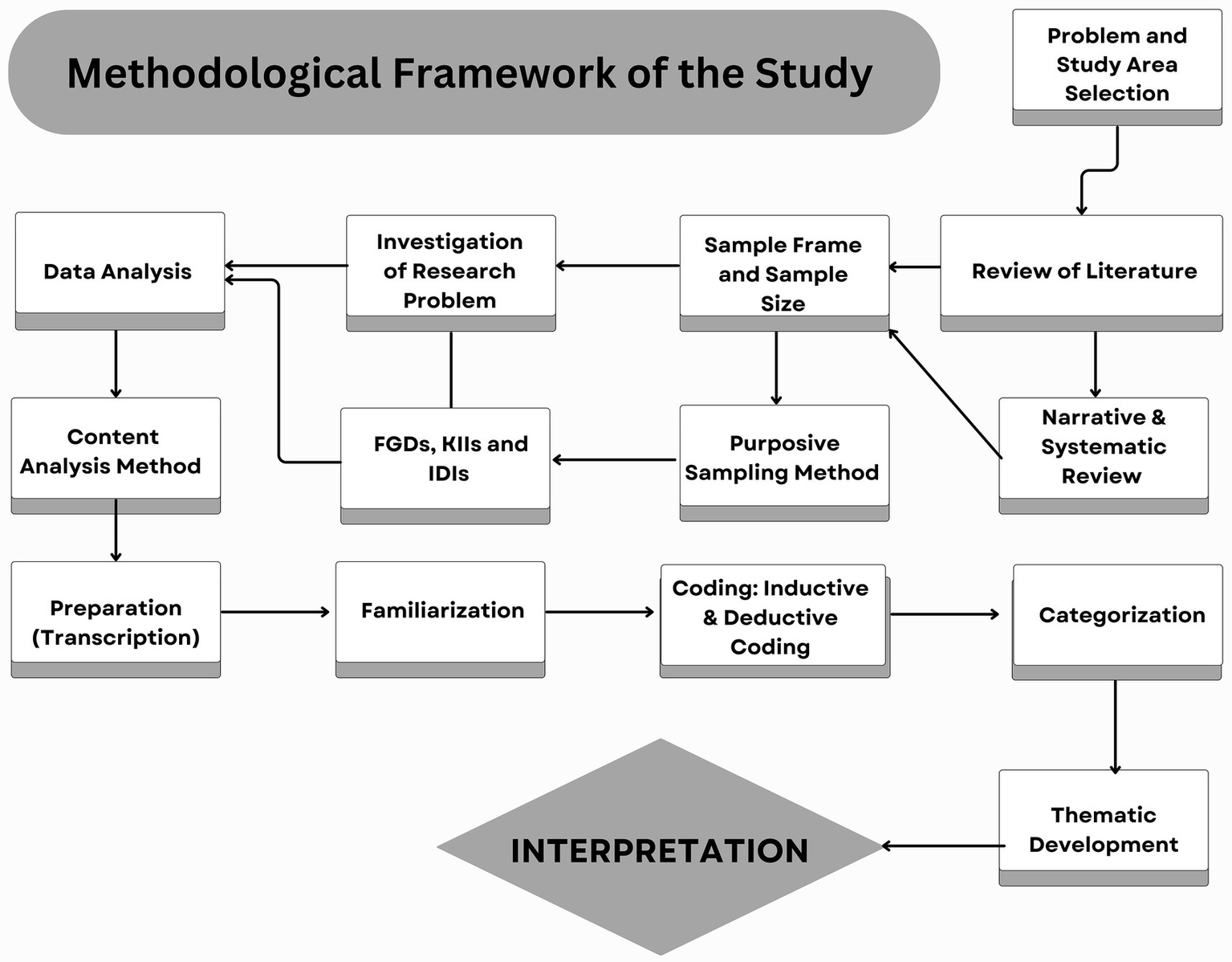

2.3 Data analysis

The data collected through FGDs, KIIs, and IDIs were analyzed using content analysis. This systematic and objective method was chosen to identify patterns, themes, and meanings within the textual data, allowing for both inductive discovery of new insights and deductive verification of concepts derived from the theoretical framework (Neuman, 2021; Creswell and Creswell, 2017).

Compared to other qualitative analyses (grounded theory, thematic analysis, ethnography), content analysis enabled the researcher to systematically analyze heterogeneous data (bridging formal policy texts and informal narrative texts). It also facilitated us to structure the needed mapping of existing concepts of “urban flood risk” onto the data while remaining flexible enough to identify latent “informal resilience” strategies.

As described in Figure 6, the content analysis process followed several systematic stages in this study. All audio recordings from FGDs and interviews were meticulously transcribed verbatim and subsequently cross-verified against their original audio sources and corresponding field notes to ensure data reliability. The transcription process was completed in two phases. In the first phase, data were collected through FGDs and KKIs were transcribed in the Pashto language. After the Pashto language transcription, all transcripts were translated into English for subsequent analysis. Subsequently, a familiarization phase involved repeated immersion in the textual data through extensive reading. The iterative process facilitated a comprehensive understanding of the dataset’s breadth and depth, leading to identify the recurring patterns and an initial conceptual mapping.

Figure 6

Methodological framework.

The subsequent coding stage was executed using a hybrid inductive and deductive methodology. Inductive coding involved an iterative open coding process, wherein emergent categories and concepts were directly derived from the data without a prior theoretical imposition. Simultaneously, deductive coding applied pre-defined codes, informed by the established theoretical framework and literature (e.g., categories about urban flood hazard, vulnerability dimensions, and resilience capacities). The latter stage involved axial coding, systematically grouping initial codes into more abstract, overarching categories based on conceptual relationships. The identified codes were then organized into a coherent structure through categorization, grouping conceptually similar codes into broader categories and contents. This systematic arrangement paved the way for content/themes development, where themes were iteratively defined and refined to ensure their robust representation of underlying meanings within the data and their direct relevance to the research objectives as described in Table 2. Finally, the interpretation phase involved a comprehensive analysis of the interrelationships among the developed contents/themes. This analytical step culminated in the formulation of conclusions, rigorously linking the emergent findings back to the existing academic literature and the study’s foundational theoretical framework. The study adhered to strict ethical guidelines to ensure the protection and well-being of all participants. Informed consent was obtained from all FGDs, KIIs, and IDIs participants before data collection. This process ensured that participants fully understood the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, their right to withdraw at any time, and the measures taken to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. All collected data were anonymized during transcription to protect individual identities. The findings are presented responsibly, respecting the voices and experiences of the community without causing harm or misrepresentation.

Table 2

| Core concept | Identified themes | Identified codes (community perceptions) |

|---|---|---|

| Urban flood risk | Drivers of flood hazard | Erratic/heavy rainfall, high water table, low infiltration, flash/urban flood frequency. |

| Exposure | Population density in floodplains, housing in active channels, and critical infrastructure in low-lying areas. | |

| Multi-dimensional vulnerability | Social: Loss of life/injury, displacement, education/health disruption, PTSD, gender-based violence, land disputes, and lack of community participation. | |

| Economic: Worsened poverty/unemployment, livelihood loss, market disruption, food insecurity, compromised basic needs, and inability to afford protective measures. | ||

| Physical: Housing/property damage, critical infrastructure damage, utility disruption, building material susceptibility. | ||

| Environmental: Water pollution, siltation, drainage obstruction, and lack of greenery. | ||

| Motivational: Lack of formal DRR education, low awareness of official systems, perceived lack of government support, and disengagement. | ||

| Community Perceptions: Subjective interpretations, lived experiences, informal knowledge, trust/distrust in authorities. | ||

| Resilience | Anticipatory | Informal community early warning systems (mosque loudspeakers) and self-monitoring of water levels. |

| Adaptive | Community-led structural adaptations (elevated house foundations), behavioral changes (e.g., land-use shifts), and unintended ecological benefits (silt for crops). | |

| Restorative | Reliance on NGOs/government relief (immediate), slow economic recovery, protracted homelessness, and demand for transparent compensation. |

Coding framework: identified codes, themes, and their interconnections regarding urban flood risk and resilience in BNB, Peshawar, Pakistan.

3 Results

This section presents the findings derived from the content analysis of the primary data, integrating direct quotes from FGDs, KIIs, and IDIs to substantiate the identified themes. The analysis is structured to address hazard assessment, multi-dimensional vulnerability, exposure of vulnerable populations, and resilience capacities, reflecting the community’s lived experiences and perceptions.

3.1 Urban flood hazard assessment

The community in the BNB perceives urban flooding as a frequent and intensifying hazard. All research participants reported experiencing flash floods, with the 2008 event being consistently cited as the “worst flood experienced by communities in the area.” Historical memory contrasted with the more frequent occurrences since 2007, suggests a perceived shift in hazard patterns, indicating a “new normal” where floods are no longer rare isolated events but recurrent threats. This perception aligns with broader literature on climate change impacts, which notes an increase in the frequency and intensity of intense precipitation events (Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 2025; Shehzad, 2023; Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 2022; Fahad and Wang, 2020; Chaudhry, 2017). The community’s understanding evolving nature of hazards is critical for comprehending their adaptive behaviors and their expectations from authorities.

While erratic precipitation in upstream areas, like Khyber and Tirah Valley, is acknowledged as a trigger, community and expert perceptions strongly attribute the severity and frequency of urban flooding to human-induced modifications of the natural environment. Research participants believe that “the flood hazard in the built environment of Peshawar is the result of both natural and anthropogenic factors.” Massive encroachment in the Bhudni Nullah is consistently highlighted as a significant reason, with “senior citizens recalling the nullah’s width ranging from 65 to 115 feet, now reduced to a mere 30–40 feet due to unchecked expansion,” as can be seen in field level photography in Supplementary material 1. This reduction in capacity is directly linked to “unplanned urbanization” and the “mushrooming of new housing schemes along Bhudni” that have “encroached the stream basin.” The construction of buildings and other structures on the floodplain has demonstrably reduced the nullah’s capacity to carry excess water. These anthropogenic factors are not merely vulnerabilities but actively enhances the flood hazard itself. These perceptions effectively shift the understanding of flood risk from “acts of nature” to “acts of man,” suggesting that flood severity is largely preventable through better urban planning, land-use regulation, and enforcement. It emphasizes the need for a human-centred approach to hazard assessment that includes the political and economic drivers of environmental degradation.

Other contributing factors to the hazard’s intensity include a high-water table due to proximity to Warsak Dam, leading to saturated land and low infiltration rates. Moreover, solid waste dumping, indicated by both residents and municipal services officials, is considered a major concern, as it “creates obstruction to the water flow” and can cause “backflow leading to inundation” beneath low bridges. The design of communication infrastructure, such as shortened bridges, also contributes to water obstruction and debris transport during floods (Supplementary material 1). These factors collectively transform natural rainfall events into severe urban flood hazards.

3.2 Vulnerability assessment

Community perceptions reveal a multi-dimensional vulnerability to urban flooding, encompassing social, economic, physical, environmental, and motivational aspects. These vulnerabilities are often interconnected, creating a complex web of susceptibility. Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of all types of vulnerabilities identified in the study area.

Table 3

| Vulnerability dimension | Key indicators/codes/manifestations (from data) | Illustrative quote(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Loss of life/injury, displacement, homelessness, PTSD, gender-based violence, and disrupted social life | “Flood killed people and caused injuries,” “Homelessness and migration to other areas,” “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was noted amongst the most vulnerable, especially children, women, and aged people.” “I do not remember about my community members being consulted by the government or participating in a project in our area.” |

| Education disruption, child labor, and school dropouts | “Negatively affected education. The majority of the schools were partially damaged, which affected the smooth flow of education… The majority of the poor people engaged their children in paid work as child labor, and such children did not go to school again.” | |

| Health service disruption, disease outbreaks | “Basic Health Units and Rural Health Centers… either fully damaged or submerged… Cases of malaria, dengue, and cholera emerged in post post-flood situation.” | |

| Land disputes | “In some communities land land-related disputes emerged due to deposition of silt on the demarcation line.” | |

| Economic | Worsened poverty, unemployment, and livelihood loss | “The flood caused and worsened the poverty level of the already impoverished people. The majority of the people are daily wagers and in post post-flood situation, they lost the opportunity to continue their work.” |

| Livelihood vs. housing trade-off, protracted recovery | “Poor people were compelled to choose between reconstruction of their houses and daily wage work.” “Even after 16 years since the 2008 flood, 5–8% of the affected people are still not able to reconstruct their houses.” | |

| Agricultural/livestock loss, food insecurity | “The agriculture and Livestock sector was badly affected… The 2008 flood killed 90% livestock in the area.” “The flood also damaged the vegetable production in the area.” | |

| Market/business disruption, reduced purchasing power | “Local markets… were severely affected… all valuable goods in those shops were damaged… low sales of the goods… their purchasing power went down.” | |

| Compromised basic needs | “The income was targeted toward the construction of homes and purchase of homes. Some people said that they compromised on the health expenditure and children’s education.” | |

| Physical | Housing/property damage, building material susceptibility | “Damages to houses and contents of houses.” “Hujras were damaged because the majority of them had adobe structures.” |

| Critical infrastructure damage, utility disruption | “Physical infrastructure, like roads and bridges, was submerged and damaged… Power supply lines were damaged it resulting in a blackout and load shedding.” | |

| Unintended consequences of mitigation | “When the water level during a flood rises, the storm water from the housing colonies is not drained to Bhudni, and it causes urban flooding.” | |

| Environmental | Water contamination, siltation of drains/streets | “Public sector water supply schemes and tube wells, as well as private wells, were contaminated by flood and caused an outbreak of cholera.” “Streets and drains were filled with silt.” |

| Industrial waste pollution | “Water Pollution is a major problem due to the drainage of industrial wastewater into the local streams.” | |

| Motivational | Lack of formal DRR education/awareness, lack of access to information | “Community-level preparedness activities, including training, were not noticed in the area.” “Very few people know about PMD or PDMA.” The majority of the upstream people, around 5% are daily wagers. They do not have access to technology to access information.” |

| Lack of community participation, disengagement | “Community participation in both public and private sector development projects is at zero level.” “DDMU has neither consulted the people nor engaged them in the mitigation projects.” | |

| Poverty limits protective measures | “People cannot afford to migrate to safe places or construct flood-proof elevated houses.” |

Analysis of multidimensional vulnerability in the BNB, Peshawar, Pakistan.

3.2.1 Social vulnerability

Urban flooding in the BNB region engenders protracted and intergenerational social vulnerability, transcending immediate physical damage. Direct impacts include fatalities, injuries, damages to houses, widespread displacement, and forced migration, leading to psychological problems, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among people. Educational continuity is significantly disrupted, characterized by “schools damaged and filled with silt and academic sessions delayed for up to six months.” This disruption correlates with an alarming increase in child labor, as “the majority of the poor people engaged their children in paid work as child labor and such children did not go to school again,” thereby exacerbating socioeconomic marginalization. Submergence of healthcare infrastructure, combined with impaired access to external medical facilities due to compromised roadways, exacerbates critical public health crises with outbreaks of vector-borne and waterborne diseases. While religious structures (mosques) generally demonstrate resilience, community centers, like “hujras,” are frequently compromised due to their inherent adobe construction.

Post-flood environments also witness an increase in gender-based violence, with “women mostly the target of verbal and physical abuse.” Altered geomorphological landscapes instigate social friction and legal disputes due to land demarcation, leading to communal-level conflicts. Another critical dimension of social vulnerability is the disempowerment of the community. Community members report “zero level” participation in both public and private sector development initiatives/projects, asserting that the government “has neither consulted the people nor engaged them in the mitigation projects.” This is coupled with the weak local government system and the limited “powers and funding” of local elected representatives, which underlines a serious disengagement of local communities from critical decision-making processes. The prevalent top-down bureaucratic paradigm, further worsened by political interference and weak local governance, renders communities as passive recipients of aid, rather than active actors in disaster risk reduction. Systemic lack of participatory governance constitutes a significant social vulnerability, impeding the integration of indigenous knowledge and community-specific needs into formal planning, thereby resulting in unsustainable interventions, creating mistrust of populations over governing authorities. In some communities, land disputes were also observed in post-flood conditions due to the demarcation lines being submerged by silt.

3.2.2 Economic vulnerability

Table 2 indicates that pre-existing poverty significantly increases the economic impact of floods, creating a “devastating economic trap” for vulnerable populations. Floods have “caused and worsened the poverty level of the already impoverished people.” Daily wage earners, who form the majority of residents, are losing livelihoods as damaged farms and industries are expected to “take six months to restart,” forcing them to make the difficult choice “between reconstruction of their houses and daily wage work.” This led to extended stays in relief camps and reliance on external aid. Even “after 16 years since the 2008 flood, 5–8% of the affected people are still not able to reconstruct their houses,” highlighting the long-term economic hardship. It represents the “risk-poverty nexus,” where disasters worsen poverty and poverty increases susceptibility to future disasters, with the most vulnerable lacking the economic resilience provided by diversified livelihoods, social safety nets, or access to credit and insurance (Hote and Koike, 2025; Chand and Gupta, 2025; Rana et al., 2022; Islam et al., 2021). The impacts extend beyond individual households to the broader local economy. The agriculture and livestock sectors were severely affected, with crops damaged and “90% livestock perished in the 2008 flood” due to the lack of warning. For many, livestock rearing and dairy product sales were the “only source of cash income monthly.” Local markets, both rural and urban, were severely affected, with water damaging buildings, shops, and valuable goods during the 2022, 2024, and 2025 floods. The subsequent “low sales of the goods” due to decreased purchasing power meant it “took a long time to recover.” Local industries, such as granite, marble, and woodworks, suffered further increasing unemployment and poverty, which in turn caused undernutrition among vulnerable groups. Families facing financial crises were compelled to compromise on “health expenditure and children’s education.” Consequently, economic resilience strategies must account for the cascading impact and must support small industries, diversify income sources, and design recovery programs that bridge the gap between immediate relief and sustainable stability.

3.2.3 Physical vulnerability

The physical vulnerability to urban floods is shown by the extensive damage inflicted upon both the built environment and crucial infrastructure. The inundation led to widespread “damages to houses and contents of houses,” rendering numerous individuals homeless (Supplementary material 1). Public facilities, including schools and health centers, suffered significantly, either “partially damaged and filled with silt” or “fully damaged or submerged by water.” Furthermore, vital physical infrastructure, such as “roads and bridges, was submerged and damaged,” severely obstructing rescue and relief operations. The disruption extended to power supply lines, causing blackouts and load shedding, which in turn cascaded into detrimental impacts on communication systems and industrial productivity.

A critical observation is the concept of “engineered vulnerability,” where some physical mitigation measures inadvertently create new risks. For example, while flood protection walls were constructed in some urban areas, they paradoxically created another problem for the community. “When the water level during a flood rises, the storm water from the housing colonies does not drain to the nullah, and it causes urban flooding.” It points to a critical flaw in flood management with a siloed, engineering-centric approach without considering the broader hydrological system or urban design. Similarly, cost-cutting measures in infrastructure development, such as the “heights of the bridges on the nullah are very low” and their “length… has been reduced,” directly increase physical vulnerability by obstructing water flow and causing significant damage downstream. The damage to physical infrastructure has direct and severe cascading impacts on livelihoods and access to essential services, demonstrating the deep interdependence between physical integrity and socio-economic well-being. The physical infrastructure is not merely static assets but critical enablers of social and economic activity, and its vulnerability directly translates into social and economic vulnerability, highlighting the need for resilient infrastructure development as a cornerstone of overall community resilience.

3.2.4 Environmental vulnerability

Environmental vulnerability within the BNB is deeply shaped by continuous pollution and ecosystem degradation, which increase flood risks and pose a significant threat to public health. The “discharge of industrial wastewater directly” into the local stream causes immense water pollution, with a particularly acute impact observed in Darmangi UC. A “pollution-flood” feedback loop has been noted as a result of the “dumping of industrial effluent, municipal water and domestic waste” into the Bhudni Nullah. The accumulation of solid waste actively “obstructs the water flow” and can lead to “backflow causing inundation.” Such environmental mismanagement is not an indirect issue but a direct contributor to heightened flood vulnerability. The absence of adequate waste management infrastructure further exposes the systemic failure in environmental governance. Furthermore, floodwaters contaminate “public sector water supply schemes and tube wells as well as private wells,” leading to outbreaks of diseases like cholera. Streets and drains become “filled with silt,” creating a ripple effect in wastewater drainage in urban areas. The broader environmental context also includes a “lack of greenery in Peshawar Valley,” which, according to research participants, makes “heat waves… a seriously challenging issue.” The green and blue spaces in the BNB were a natural buffer to absorb water and reduce flood intensity, suggesting that environmental vulnerability is interconnected and needs a holistic management approach. It includes proper waste disposal, segregation of wastewater from the stream water, reforestation and protection of natural drainage systems to enhance the overall ecological resilience of the basin.

3.2.5 Motivational vulnerability

Motivational vulnerability stems from a perceived disengagement from formal risk reduction processes and a lack of access to relevant knowledge and resources. Community participation in government development projects is perceived as “zero level,” with the district government reportedly having “neither consulted the people nor engaged them in the mitigation projects.” The lack of engagement extends to preparedness as “community-level preparedness activities, including training, were not noticed in the area.” A significant barrier is the absence of a dedicated government early warning system (EWS) that effectively reaches the community. While the PDMA issues warnings via media, “the majority of the upstream people, around 65% are daily wagers. They do not have access to technology to access information. Besides, very few people know about the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) or the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA).” Reliance on informal systems where “local people themselves monitor the situation in flood seasons and use mosques’ loudspeakers for communication of warning during flood” is a commonly observed pattern in the study area.

The reliance on informal systems, while adaptive, may also stem from a lack of trust or access to official channels, implying that communities feel disengaged from formal DRR efforts. Erosion of trust and self-efficacy, linked to a perceived lack of agency and external support is a critical barrier to sustainable resilience building. Moreover, communities exhibit motivational vulnerability due to a “lack of proper education/disaster risk education” and “illiteracy, as many people do not know where and how to construct their houses to cope with the problem of flooding.” Despite possessing valuable local knowledge and informal warning systems, they lack the formal technical know-how and financial resources to implement strong protective measures. The unavoidable poverty means “people cannot afford to migrate to safe places or construct flood-proof elevated houses,” further limiting their perceived ability to act. Motivational vulnerability is therefore intertwined with educational and economic barriers, requiring integrated capacity building that respects and augments local initiatives.

3.3 Exposure of the most vulnerable populations

The exposure of vulnerable populations in the BNB is a critical aspect of flood risk, driven by a combination of geographical proximity to the hazard and socio-economic factors. A significant finding is that “84 villages are located within the proximity of one kilometre of both sides” of the Bhudni Nullah, placing a large population directly in the flood’s path. The primary driver of this exposure is economic necessity. Communities are observed to be “after purchasing cheap plots on easy instalment without keeping in view that the same area was flooded from 4 to 8 feet in the past.” This indicates that poverty limits choices, pushing vulnerable groups into hazardous areas. The pervasive “poverty is a major social problem in both urban and rural areas of the Bhudni Nullah,” meaning “people cannot afford to migrate to safe places or construct flood-proof elevated houses,” demonstrating that exposure is not merely a geographical factor but a socio-economic outcome. Addressing exposure requires not just land-use planning but also poverty alleviation and affordable but safe housing alternatives. Additionally, specific demographic groups are disproportionately exposed and suffer more severe impacts. “PTSD was noted amongst the most vulnerable, especially children, women, and aged people.” A significant portion of the upstream population, around “daily wagers,” who “do not have access to technology to access information” regarding official warnings. The broader literature indicating that low-income residents are disproportionately impacted by flooding.

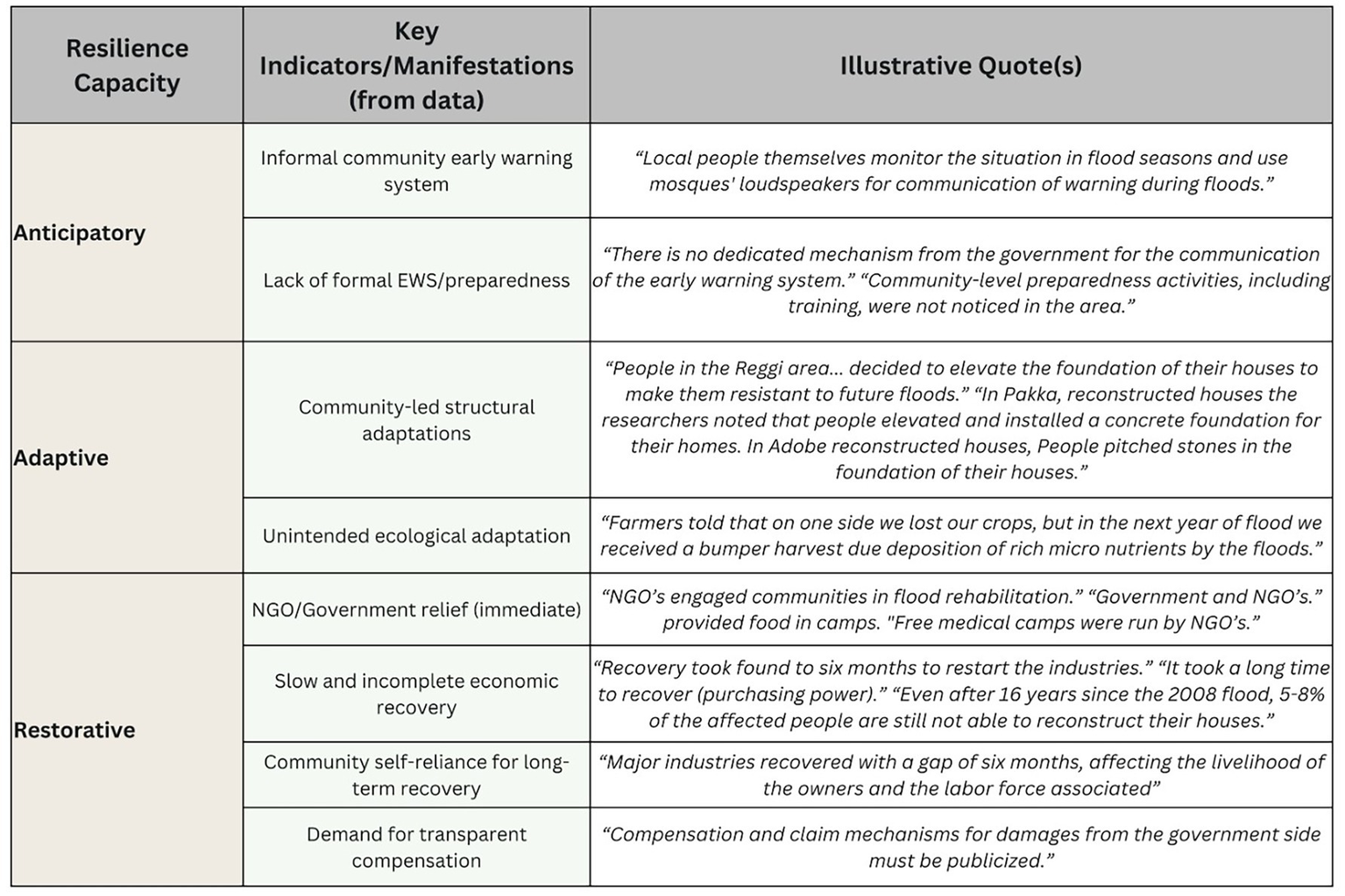

3.4 Resilience capacities

Despite the significant vulnerabilities, communities in the BNB demonstrate various forms of resilience, including anticipatory, adaptive, and restorative capacities. These capacities, however, often operate informally and face limitations due to systemic challenges, but these have helped communities in protection from floods. Figure 7 provides details of these resilience capacities.

Figure 7

Observed anticipatory, adaptive, and restorative capacities in BNB.

3.4.1 Anticipatory resilience

Communities in the BNB demonstrate a noteworthy, albeit informal, anticipatory capacity. In the absence of a dedicated government EWS, “local people themselves monitor the situation in flood seasons and use mosques’ loudspeakers for communication of warning during floods.” Using the strength of social networks and traditional communication channels in local preparedness is one of the key resilience factors. However, the informal system is limited by a lack of formal integration, technical knowledge, and broader reach, pointing out a critical reliance on traditional social capital for early warning, which is locally effective but lacks the scalability, technical precision, and official backing. Integrating these informal systems with formal ones and ensuring accessible communication channels is key to strengthening anticipatory resilience. A significant “knowledge-action” gap exists in preparedness. Despite community awareness of the recurring flood hazards, “community-level preparedness activities, including training, were not noticed in the area.” Community members reportedly “do not understand the technical language of the early warning institutions” and lack knowledge regarding building codes, early warning mechanisms, and evacuation procedures. It shows that awareness alone is insufficient; it must be combined with practical training and accessible information on specific preparedness measures to translate into effective anticipatory resilience.

3.4.2 Adaptive resilience

A powerful form of adaptive resilience observed in the community is the bottom-up structural adaptation. Following past floods, “people in the Reggi area… decided to elevate the foundation of their houses to make them resistant to future floods.” Installing concrete foundations in reconstructed “pakka” houses and pitching stones in the foundations of “adobe” houses are recommended structural mitigation measures for flooding. The initiative, driven by direct experience and a desire for future protection, is a crucial self-organized adaptation. It demonstrates learning from past disasters and proactive efforts to reduce future physical vulnerability. Bottom-up adaptation should be recognized, supported, and potentially scaled up by formal programmes through training for local masons, who are often the primary architects for community housing.

An unexpected, positive ecological adaptation was also noted in the agricultural sector. Farmers reported that while they lost crops during floods, “in the next year of flood, we received a bumper harvest due to deposition of rich micro nutrients by the floods.” The unintended benefit highlights the dual nature of natural events and the potential for ecosystems to provide adaptive benefits. While not a planned human adaptation, it points to the importance of understanding and potentially using natural processes in flood management, such as maintaining floodplains as natural buffers. Another major adaptive capacity is the construction of natural barriers from the deposited silt along the Bhudni Nullah and the subsequent plantation on it as a potential nature-based solution (Supplementary material 1). This cost-effective and sustainable nature-based solution in some villages in the BNB has increased water retention and infiltration, reduced sediment load observed, helped in controlling erosion, and provided positive ecological and biodiversity benefits.

3.4.3 Restorative resilience

Restorative resilience in the BNB is characterized by a mix of external aid and significant self-reliance, often hampered by systemic deficiencies. In the immediate aftermath of floods, non-government organizations (NGOs) played a crucial role by “engaging communities in flood rehabilitation” and providing essential relief, such as food in camps and running “free medical camps.” The government also initiated a “vaccination campaign” in one affected area. However, the long-term restorative capacity appears inadequate. The recovery process for industries took “six months to restart,” and it “took a long time to recover” for the general purchasing power of the community. A basic indicator of protracted recovery was “the affected people are still not able to reconstruct their houses.” Data reveal that humanitarian relief mechanisms exist but the systemic process of resilient recovery and restoration of livelihoods is very weak and inaccessible to everyone. Restorative resilience is critically dependent on effective and equitable post-disaster recovery policies and their implementation.

Furthermore, the community expressed a need for the “compensation and claim mechanism for damages from the government side must be publicized,” indicating a lack of transparency and accessibility in formal recovery processes. In the absence of robust formal support, communities are largely left to their own for long-term recovery, which is severely constrained by pre-existing poverty. Restorative resilience for the most vulnerable is often a struggle for survival rather than a structured recovery process. The need for a transparent and accessible recovery framework focused on accessible compensation, unconditional cash grants, technical assistance, reconstruction of homes and infrastructure and livelihood restoration programmes is recommended for a resilient recovery.

4 Discussion

The study results reveal that both human and natural factors play an intricate role in enhancing urban flood risk in BNB, Peshawar. The community’s perception of a “new normal” where urban floods are no longer rare but recurring threats aligns with broader scientific observations on the impacts of climate change (Das and Sahoo, 2025; Abubakar et al., 2025; Abdul et al., 2025; Dugstad et al., 2025; Müller et al., 2024; Rahman et al., 2023; Hussain et al., 2021). Results reveal that in Peshawar, the rapidity and severity of urban flooding have significantly increased validate existing literature, indicating an increase in the frequency and intensity of precipitation events globally and specifically in South Asia (Janizadeh et al., 2024; Hussain M. et al., 2023; Ullah et al., 2021). In a recent study, Das et al. (2023) highlight that climate change directly influences extreme precipitation patterns in the region, providing a macro-level explanation for the community’s lived experience of more frequent and intense flood events.

The study’s findings also highlight the significance of community-level perspectives, which attribute flood severity primarily to anthropogenic factors rather than exclusively to natural causes. This perception is validated by the consistent emphasis on massive encroachment within the Bhudni Nullah, resulting in a substantial reduction of its capacity. The literature supports the assertion, highlighting the role of unplanned urbanization and the proliferation of housing schemes in floodplains as key triggers of flood hazards in the BNB (Khan I. et al., 2022; Tayyab et al., 2021; Hamidi et al., 2020). In recent studies, Todini (2025), Bagheri and Liu (2025), and Dharmarathne et al. (2024) state that anthropogenic factors including unregulated urbanization directly increase flood risk in urban environments (Qazi et al., 2024). The issues of high-water tables, solid waste dumping obstructing the water flow and poorly designed infrastructure, like low-elevation bridges, are also critical anthropogenic factors in the BNB. These results support the findings of previous studies, such as Rahman et al. (2025b) and Agborabang and Ori (2025).

Like other developing nations, vulnerability in the BNB is multi-dimensional, spanning social, economic, physical and motivational aspects, a common pattern in developing nations. Floods inflict profound psychological harm, including PTSD among vulnerable groups and disrupt education, forcing children into child labour and perpetuating intergenerational poverty (Yousuf et al., 2023; Sawada and Takasaki, 2017). Furthermore, floods intensify existing gender inequality, leading to increased gender-based violence (Gul et al., 2024). A critical social vulnerability is the “zero level” of community participation in government projects. The top-down bureaucratic approach disempowers locals, erodes trust and significantly undermines flood resilience by failing to integrate vital local knowledge (Jan and Muhammad, 2020). Economically, existing poverty traps are deepened as floods destroy livelihoods for daily wage earners and devastate agriculture, reflecting findings from other developing regions where long-term recovery becomes impossible (Parvin et al., 2016). Physical vulnerability is marked by damage to homes and infrastructure. A critical concept is “engineered vulnerability,” where poorly integrated flood protection structures inadvertently intensify flooding by obstructing stormwater drainage (maladaptation) (Ginige et al., 2022). Furthermore, substandard, cost-cutting infrastructure design increases physical risks (Almulhim, 2025). Environmental vulnerability is characterized by a “pollution-flood feedback loop,” as industrial waste and solid garbage block the Nullah, intensifying flood risk and contamination water sources (Dharmarathne et al., 2024). Finally, motivational vulnerability stems from a perceived disengagement from formal systems. The lack of an effective, accessible early warning system for all community segments forces reliance on informal methods. It is observed that a crucial “knowledge-action” gap, where local awareness is not translated into formal flood-proof action (Rana et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2020). The exposure of vulnerable populations in the BNB is primarily driven by economic necessity rather than mere geographical proximity. The finding that “84 villages are located at a proximity of one kilometer” to the nullah is critical but the underlying driver for occupying these hazardous areas is poverty, compelling communities to purchase “cheap plots on easy instalment” despite known flood risks. The situation reinforces the conceptual model put forth by Wisner et al. (2003), which posits that vulnerability to natural hazards in developing countries is fundamentally rooted in socio-economic conditions and power structures that limit choices and push marginalized groups into risky environments.

Despite inescapable vulnerabilities, communities in the BNB exhibit significant resilience capacities with remarkable self-reliance. Anticipatory resilience is evident in the community-led informal early warning systems, where local people themselves monitor the situation and use mosques’ loudspeakers for communication of warnings, exhibiting the role of social capital and traditional communication channels in local preparedness (Xiong and Li, 2024; Panday et al., 2021). However, the limitations of an informal system are the lack of formal integration, technical knowledge and broader reach, highlighting the need for a hybrid approach that builds upon local strengths while providing official support. Adaptive resilience is confirmed through bottom-up structural adaptations, such as communities in the BNB deciding to elevate the foundation of their houses. Proactive and self-organized initiative driven by direct experience and a desire for future protection represents a critical form of learning from past disasters (Conway et al., 2019; Girard et al., 2015).

The unexpected ecological adaptation of “bumper harvest” due to nutrient-rich silt deposition points to the potential for understanding natural processes, a concept central to nature-based solutions. The construction of natural barriers from deposited silt and subsequent plantation along the Nullah further exemplifies adaptive resilience through a cost-effective, nature-based solution. These solutions effectively reduced urban flood risk by increasing water retention, reducing sediment and controlling erosion. The findings align perfectly with the observed benefits stated by Aghaloo et al. (2024) and Qi et al. (2020). Restorative resilience in the BNB is characterized by a mix of immediate external aid and significant community self-reliance. NGOs played a crucial role in immediate flood rehabilitation and provided essential relief, consistent with their established role in humanitarian response. However, the long-term restorative capacity appears inadequate as shown by the protracted economic recovery and the fact that some affected people are still not able to reconstruct their houses even after 16 years following a major flood. It highlights a systemic failure in long-term recovery mechanisms and challenges in livelihood restoration. The community’s demand for a publicized compensation and claim mechanism for damages points to a lack of transparency and accessibility in formal recovery processes. Disaster compensation mechanisms often note their limitations in ensuring equitable and complete long-term recovery, particularly for the most vulnerable populations. This underscores that for many, restorative resilience is not a structured recovery but a struggle for survival (Jan et al., 2024).

5 Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of urban flood risk in the BNB, integrating community lived experiences with insights from academic literature. The findings reveal that urban flooding is an intensifying hazard, significantly amplified by human-induced factors such as encroachment, unplanned urbanization, and inadequate waste management. Multi-dimensional vulnerabilities, including the social, economic, physical, environmental, and motivational, exacerbate the impacts of floods and trap communities in a cycle of poverty and susceptibility. Notably, poverty drives vulnerable populations to reside in highly exposed areas, reinforcing the notion that exposure is as much a socio-economic outcome as a geographical one. Despite these challenges, communities demonstrate remarkable anticipatory, adaptive, and restorative resilience, characterized by informal early warning systems, bottom-up structural adaptations, and the utilization of nature-based solutions. However, these capacities are often limited by systemic governance gaps, a lack of formal support, and inadequate long-term recovery mechanisms. The study underscores the critical need for integrated, participatory, and context-specific disaster risk reduction strategies that address the root causes of vulnerability, leverage local knowledge and initiatives, and ensure equitable access to resources and transparent recovery processes for building sustainable urban resilience in the BNB and similar contexts.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because we have already provided the generated code (Data) as Table 1 in the study. The rest of the data is confidential due to the identifiable information of the research participants. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Mushtaq Ahmad Jan, mushtaq@uop.edu.pk.

Ethics statement

The study adhered to all applicable local legislation and the ethical guidelines of the Graduate Studies Committee of the Centre for Disaster Preparedness and Management (CDPM), University of Peshawar. All research participants provided their written informed consent, having been fully apprised of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty.

Author contributions

MJ: Methodology, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft. KA: Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. SU: Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. WU: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation. HT: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. TF: Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Conceptualization. AA: Methodology, Data curation, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MT: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Validation. MS: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors express their gratitude to the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) for the support under the International Grant, EP/PO28543/1, entitled “A Collaborative Multi-Agency Platform for Building Resilient Communities,” and the GCRF and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) support under the Grant ES/T003219/1 entitled “Technology Enhanced Stakeholder Collaboration for Supporting Risk-Sensitive Sustainable Urban Development. The authors acknowledge Rabdan Academy, United Arab Emirates (UAE), for supporting article processing charges (APC).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI used for the grammatical correction of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1725174/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdul L. Yu T. Yousif Mangi M. (2025). Climate change and urban vulnerabilities: analysing flood and drought resilience of Islamabad. Local Environ.30, 1082–1098. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2025.2472370

2

Abubakar I. R. Onyebueke V. U. Lawanson T. Barau A. S. Bununu Y. A. (2025). Urban planning strategies for addressing climate change in Lagos megacity, Nigeria. Land Use Policy153:107524. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2025.107524

3

Agborabang S. E. Ori A. (2025). Assessing the effects of flood waste on municipal solid waste systems: a community centric approach to waste management. J. Geoscience Environ. Prot.13, 184–205. doi: 10.4236/gep.2025.133011

4

Aghaloo K. Sharifi A. Habibzadeh N. Ali T. Chiu Y.-R. (2024). How nature-based solutions can enhance urban resilience to flooding and climate change and provide other co-benefits: a systematic review and taxonomy. Urban Forestry Urban Green.95:128320. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128320

5

Ahmad M. Wilkins S. (2025). Purposive sampling in qualitative research: a framework for the entire journey. Qual. Quant.59, 1461–1479. doi: 10.1007/s11135-024-02022-5

6

Ahmed S. K. (2024). How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: a simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep.12:100662. doi: 10.1016/j.oor.2024.100662

7

Ali A. Iqbal S. Amin N. U. Malik H. L. (2015). Urbanization and disaster risk in Pakistan. Acta Tech. Corviniensis Bull. Eng.8:161. Available at: https://acta.fih.upt.ro/pdf/2015-3/ACTA-2015-3-30.pdf

8

Ali A. Jan M. A. Tariq H. 2022 Flood hazard assessment of Budhni Nullah, Peshawar: Mobilise Case Study Report. Available online at: https://www.mobilise-project.org.uk/ (Accessed June 17, 2025).

9

Ali A. Ullah W. Khan U. A. Ullah S. Ali A. Jan M. A. et al . (2024). Assessment of multi-components and sectoral vulnerability to urban floods in Peshawar – Pakistan. Nat. Hazards Res.4, 507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.nhres.2023.12.012

10

Almulhim A. I. (2025). Building urban resilience through smart city planning: a systematic literature review. Smart Cities8:22. doi: 10.3390/smartcities8010022

11

Arosio M. Arrighi C. Bonomelli R. Domeneghetti A. Farina G. Molinari D. et al . (2024). Unveiling the assessment process behind an integrated flood risk management plan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.112:104755. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104755

12

Asamoah M. Dzodzomenyo M. Gyimah F. T. Li C. Agyemang L. Wright J. (2024). A qualitative study of lived experience and life courses following dam release flooding in northern Ghanaian communities: implications for damage and loss assessment. PLoS One19:e0310952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0310952,

13

Asian Development Bank and World Bank 2010 Pakistan Floods 2010: Preliminary Damages and Needs Assessment. Available online at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/linked-documents/44372-01-pak-oth-02.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2025).

14

Bagheri A. Liu G.-J. (2025). Climate change and urban flooding: assessing remote sensing data and flood modeling techniques: a comprehensive review. Environ. Rev.33, 1–14. doi: 10.1139/er-2024-0065,

15

Celebi Cakiroglu O. Tuncer Unver G. Cakiroglu S. (2025). Traces of earthquake: traumatic life experiences and their effects on volunteer nurses in the earthquake zone–an interpretative phenomenological study. Public Health Nurs.42, 899–911. doi: 10.1111/phn.13532,

16

Chand I. Gupta C. (2025). Community-Based Landslide Risk Reduction in Himachal Pradesh, India. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.5259000

17

Chaudhry Q. U. Z. (2017). Climate change profile of Pakistan. Islamabad: Asian Development Bank.

18

Conway D. Nicholls R. J. Brown S. Tebboth M. G. L. Adger W. N. Ahmad B. et al . (2019). The need for bottom-up assessments of climate risks and adaptation in climate-sensitive regions. Nat. Clim. Chang.9, 503–511. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0502-0

19

Creswell J. W. Creswell J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London: Sage publications.

20

Creswell J. W. Creswell J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

21

Das S. Choudhury M. R. Chatterjee B. Das P. Bagri S. Paul D. et al . (2024). Unraveling the urban climate crisis: exploring the nexus of urbanization, climate change, and their impacts on the environment and human well-being–a global perspective. AIMS Public Health11, 963–1001. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2024050

22

Das P. K. Roy B. Biswas S. Das S. K. Joardar S. N. Samanta I. 2023 Emerging Practices in Animal Husbandry and Fisheries vis-à-vis Climate Change., in Proceedings of National Symposium of Indian Journal of Animal Health, 1–68

23

Das A. Sahoo S. N. (2025). Impact of land use and climate change on urban flooding: a case study of Bhubaneswar city in India. Nat. Hazards121, 8655–8674. doi: 10.1007/s11069-025-07130-5

24

Deen S. (2015). Pakistan 2010 floods. Policy gaps in disaster preparedness and response. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.12, 341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.03.007

25

Dharmarathne G. Waduge A. O. Bogahawaththa M. Rathnayake U. Meddage D. P. P. (2024). Adapting cities to the surge: a comprehensive review of climate-induced urban flooding. Results Eng.22:102123. doi: 10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102123

26

Dugstad A. Ben Hammou H. Navrud S. (2025). Valuing the benefits of climate adaptation measures to reduce urban flooding: community preferences for nature-based solutions. Water Resour. Econ.49:100257. doi: 10.1016/j.wre.2025.100257

27

Fahad S. Wang J. (2020). Climate change, vulnerability, and its impacts in rural Pakistan: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.27, 1334–1338. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06878-1,

28

Folke C. (2006). Resilience: the emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change16, 253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

29

Ginige K. Mendis K. Thayaparan M. (2022). An assessment of structural measures for risk reduction of hydrometeorological disasters in Sri Lanka. Prog. Disaster Sci.14:100232. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2022.100232

30

Girard C. Pulido-Velazquez M. Rinaudo J.-D. Pagé C. Caballero Y. (2015). Integrating top–down and bottom–up approaches to design global change adaptation at the river basin scale. Glob. Environ. Change34, 132–146. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.07.002

31

Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (2022). Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Climate Change Action Plan. Peshawar. Available online at: https://epakp.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa-Climate-Change-Action-Plan-August-2022-English.pdf (Accessed December 2, 2024).

32

Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (2025). Inclusive Summer Hazards Contingency Plan 2025. Peshawar. Available online at: https://www.pdma.gov.pk/public/storage/downloads/files//DtdsirUd6Hlva2QHhLcx8abhyQOEWVVrj4clDMlV.pdf (Accessed July 3, 2025).

33

Government of Pakistan (2022). Pakistan Flood 2022: Post Flood Damage Need Assessment. Islamabad. Available online at: https://www.pc.gov.pk/uploads/downloads/PDNA-2022.pdf (Accessed October 28, 2024).

34

Government of Pakistan 2024 National Disaster Management Plan III Islamabad Available online at: http://www.ndma.gov.pk/storage/plans/July2024/vWxklzviXxzbgPGHuitB.pdf (Accessed March 24, 2025).

35

Gul S. Khan N. Nisar S. Ali Z. Ullah U. (2024). Impact of climate change-induced flood on women’s life: a case study of 2022 flood in district Nowshera, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J. Asian Dev. Stud.13, 1468–1482. doi: 10.62345/jads.2024.13.2.117

36

Hamidi A. R. Wang J. Guo S. Zeng Z. (2020). Flood vulnerability assessment using move framework: a case study of the northern part of district Peshawar, Pakistan. Nat. Hazards101, 385–408. doi: 10.1007/s11069-020-03878-0

37

Hanf F. S. Ament F. Boettcher M. Burgemeister F. Gaslikova L. Hoffmann P. et al . (2025). Towards a socio-ecological system understanding of urban flood risk and barriers to climate change adaptation using causal loop diagrams. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev.17, 69–102. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2025.2474399

38

Hanif I. (2019). Day-long heavy rain spell disrupts life in Lahore. Islamabad: Dawn News.

39

Hote H. H. Koike T. (2025). Addressing foundational issues for effective flood risk governance in Pakistan. Water Policy27, 334–354. doi: 10.2166/wp.2025.236

40

Hussain A. Hussain I. Ali S. Ullah W. Khan F. Rezaei A. et al . (2023). Assessment of precipitation extremes and their association with NDVI, monsoon and oceanic indices over Pakistan. Atmos. Res.292:106873. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2023.106873

41

Hussain M. Tayyab M. Ullah K. Ullah S. Rahman Z. U. Zhang J. et al . (2023). Development of a new integrated flood resilience model using machine learning with GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis. Urban Clim.50:101589. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101589

42

Hussain M. Tayyab M. Zhang J. Shah A. A. Ullah K. Mehmood U. et al . (2021). GIS-based multi-criteria approach for flood vulnerability assessment and mapping in district Shangla: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability13:3126. doi: 10.3390/su13063126

43

Hussain M. Ullah K. Tayyab M. Ullah S. Shah A. A. Zhang J. et al . (2025). Data-driven multi-hazard susceptibility and community perceptions assessment using a mixed-methods approach. J. Environ. Manag.388:126009. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.126009,

44

Ibrahim M. Huo A. Ullah W. Ullah S. Ahmad A. Zhong F. (2024). Flood vulnerability assessment in the flood prone area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci.12:1303976. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1303976

45

Ibrahim M. Huo A. Ullah W. Ullah S. Xuantao Z. (2025). An integrated approach to flood risk assessment using multi-criteria decision analysis and geographic information system. A case study from a flood-prone region of Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci.12:1476761. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1476761

46

Iftikhar A. Iqbal J. (2023a). Factors responsible for urban flooding in Karachi: a case study of DHA. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag.5, 83–103. doi: 10.18485/ijdrm.2023.5.1.7

47

Iftikhar A. Iqbal J. (2023b). The factors responsible for urban flooding in Karachi (a case study of DHA). Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag.5, 81–103.

48

Iqbal A. Haque S. Murshed S. B. Saiful Islam A. K. M. Hussain M. A. (2025). Climate vulnerability and risk assessment in low-lying coastal cities of Bangladesh using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) approach. J. Water Clim. Chang.16, 2952–2973. doi: 10.2166/wcc.2025.744

49

Islam S. Zobair K. Chu C. Smart J. Alam M. (2021). Do political economy factors influence funding allocations for disaster risk reduction?J. Risk Financ. Manag.14:85. doi: 10.3390/jrfm14020085

50

Jan M. A. Muhammad N. (2020). Governance and disaster vulnerability reduction: a community based perception study in Pakistan. J. Bio. Env. Sci16, 138–149. Available online at: https://innspub.net/governance-and-disaster-vulnerability-reduction-a-community-based-perception-study-in-pakistan/ (Accessed May 25, 2025).

51

Jan M. A. Saeed M. Kaleem M. (2024). Community satisfaction from government-led emergency response and recovery to Pakistan climate catastrophe of flood 2022 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Glob. Sociol. Rev.IX, 13–30. doi: 10.31703/gsr.2024(IX-IV).02

52

Jan M. A. Ullah S. I. Ullah W. Ullah S. Tariq H. Fernando T. et al . (2025). Analyzing and conceptualizing Pakistan’s pioneering disaster risk communication Mobile application: a case study of PDMA Madadgar. Front. Commun.10:1593319. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1593319

53

Janizadeh S. Kim D. Jun C. Bateni S. M. Pandey M. Mishra V. N. (2024). Impact of climate change on future flood susceptibility projections under shared socioeconomic pathway scenarios in South Asia using artificial intelligence algorithms. J. Environ. Manag.366:121764. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121764

54

Khan I. Ali A. Ullah W. Jan M. A. Ullah S. Laker F. A. et al . (2024). Mainstreaming disaster risk reduction (DRR) into development: effectiveness of DRR investment in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci.12:1474344. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1474344

55

Khan I. Ali A. Waqas T. Ullah S. Ullah S. Shah A. A. et al . (2022). Investing in disaster relief and recovery: a reactive approach of disaster management in Pakistan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.75:102975. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102975

56

Khan A. N. Jan M. A. (2015). “National strategy, law and institutional framework for disaster risk reduction in Pakistan” in Disaster risk reduction approaches in Pakistan. Disaster risk reduction (methods, approaches and practices). eds. RahmanA. U.KhanA.ShawR. (Tokyo: Springer), 241–257.

57

Khan S. N. Mujahid D. Zahid S. M. H. (2022). Application of GIS/RS in assessment of flash flood causes and damages: a case study of Budhni Nullah, district Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustain. Bus. Soc. Emerg. Econ.4:2262. doi: 10.26710/sbsee.v4i2.2262

58

Mekkaoui O. Morarech M. Bouramtane T. Barbiero L. Hamidi M. Akka H. et al . (2025). Unveiling urban flood vulnerability: a machine learning approach for mapping high risk zones in Tetouan City, northern Morocco. Urban Sci.9:70. doi: 10.3390/urbansci9030070

59

Müller O. V. McGuire P. C. Vidale P. L. Hawkins E. (2024). River flow in the near future: a global perspective in the context of a high-emission climate change scenario. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci.28, 2179–2201. doi: 10.5194/hess-28-2179-2024

60

Mwilongo N. (2025). Focus group discussions in qualitative research: dos and don’ts. Eminent J. Soc. Sci.1, 1–16. doi: 10.70582/28z5p189

61

Neuman W. L. (2021). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 8th Edn. London: Pearson Education Limited.

62

Neves J. L. 2024 Floods Vulnerability and the Quest for Resilience-Urban Planning and Development Challenges in Matola, Mozambique. doi: 10.1080/19376812.2022.2076133

63