Abstract

In an era of increasing urbanization and sealing, green and open spaces are being displaced at an accelerated rate. However, it is precisely these spaces that contribute to the liveability of a city for its inhabitants, including a significant number of schoolchildren. Concurrently, urban green infrastructure is strategically integrated into the city's structures with a view to providing ecosystem services that support human well-being. The prevailing assumption is that green infrastructure exerts a significant influence on the play behavior of children in school yards, with certain green elements being hypothesized to foster increased creativity. The present pilot study, which was conducted in the city of Leipzig, Germany, examined the importance of green infrastructure on children's schoolyard activities at five elementary schools which were selected at random. Of particular interest was the importance of specific elements of UGI that foster creative play. The study employed a non-participant observation approach, wherein the children's activities were meticulously documented, and a comprehensive mapping of the elementary school schoolyards was conducted to ascertain the proportions of green and gray areas, as well as their arrangement. The research findings are noteworthy in demonstrating that mid-height green infrastructure exerts a positive influence on creative play behavior of primary school children, with a particular emphasis on the promotion of creative play, which in turn contributes to the cognitive development of younger children.

Graphical Abstract

Illustrating the article core content created using Napkin.

Introduction

An increasing share of the European population is now residing in urban areas, a trend that is set to continue (Elmqvist et al., 2021). This development is likely to result in a greater emphasis on denser housing construction. In Germany, approximately 75% of the population resides in urban areas, and the increasing demand for building land is exerting substantial pressure on green and open spaces. In addition to increasing densification, related traffic and air pollution, cities must also deal with the impacts of climate change, such as heatwaves and tropical nights (Barber et al., 2021).

Urban green infrastructure (UGI) has been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in the adaptation process to such extreme events, thereby enhancing both the coping capacities and the resilience of cities (Gómez-Baggethun et al., 2013). The presence of UGI has been observed in a variety of settings, including public spaces such as parks, urban forests, and trees, as well as within constructed environments designed for educational purposes, such as schoolyards.

Concurrently, recent research findings indicate that children in urban areas are increasingly spending less time in natural environments, despite the well-documented importance of this exposure for their optimal development (Chawla, 2015; Raith, 2017a,b). Research has highlighted the significance of children's exposure to nature in fostering the development of healthy, sustainable, and liveable cities (World Health Organization, 2017; Douglas et al., 2017). Given that schoolchildren spend a significant proportion of their day in schoolyards, the potential of green or greened schoolyards to contribute to their physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development and health is considerable (Chawla, 2015). In particular, the importance of natural elements in schoolyards for cognitive development is still underestimated, and UGI is implemented mainly because of its well-known cooling and air purification functions (Haase et al., 2014a,b).

The objective of this study, which employs a pilot character, is to ascertain the extent to which green infrastructure in school yards exerts an influence on the play behavior of elementary school children. In particular, the study is looking for elements of UGI in schoolyards that foster creative play. The study is being conducted in five elementary schools in the city of Leipzig, Germany, which have been selected at random. The schoolyards have been mapped to record the green and gray infrastructure. In addition, a non-participatory observation of school children's play behavior in the schoolyard was conducted. This will relate proportions and types of green and gray infrastructure to the observed schoolyard activities of the school children.

It is assumed, based on an extensive review of the relevant literature, that gray infrastructure more exclusively encourages students to play actively when play elements, such as playgrounds and playhouses, are present (see papers by Fjørtoft, Dyment, Raith or Smith, and others cited in this manuscript). From a developmental, environmental and social point of view, UGI has clear advantages as it encourages students to play creatively. The type of UGI has been found to influence children's play behavior, encouraging more creative games. Specifically, the presence of half-height green elements has been observed to promote role-playing and hide-and-seek, in contrast to gray infrastructure (Fjørtoft, 2001; Fjørtoft and Sageie, 2000).

Urban green infrastructure

Urban green infrastructure (UGI) is defined as encompassing not only (relict) natural forest or meadow green spaces, but also natural design elements that have been strategically and purposefully created in urban areas (Pauleit et al., 2019). The UGI model comprises a park, garden, roof-green, back- and frontyard structures. These elements are designed, planned and managed to provide a variety of ecosystem services, including air cooling and air cleaning (Haase, 2020; Haase et al., 2014a,b). Such ecosystem services have the capacity to benefit individuals in both a direct and indirect manner, particularly in the context of public health (Groot et al., 2002). In addition to their regulatory function, UGI offers cultural services that encompass health benefits, tourism and social cohesion (Barber et al., 2021). It is evident that UGI has the capacity to support a variety of societal goals and promote sustainable urban development. These include the protection of biodiversity, the promotion of health and well-being, and the adaptation to climate change (Gómez-Baggethun and Barton, 2013; Dushkova and Haase, 2020; Haase, 2020; Schwarz et al., 2021). The positive impact of UGI on human well-being and public health is of particular importance for urban dwellers (Annerstedt et al., 2012; Kabisch et al., 2016a,b), as counteracts environmental and stress burdens of urban life. The impact of this phenomenon has been demonstrated to encompass a reduction in stress levels, enhanced psychological relaxation, a decrease in mental health issues, and an increase in physical activity (Barber et al., 2021; Schipperijn et al., 2010; Ward Thompson et al., 2012).

Gray infrastructure

Gray infrastructure can be defined as the counterpart to UGI and includes built-up and sealed areas such as buildings of different height, streets, squares, sealed backyards, parking, and storage areas, building façades, and roofs, as well as parts of technical infrastructure including supply and disposal systems and transport systems which facilitate urban functionality (Naumann et al., 2011; Zwierzchowska et al., 2021). It has been demonstrated that UGI has the capacity to complement, and in certain instances even supplant, gray infrastructure through unsealing, the planting of trees, and the creation of permeable and perforated surfaces (Haase, 2025).

School playgrounds

(Pauleit et al. 2019) propose a taxonomy of UGI, subdividing it into 44 distinct types including ‘institutional green spaces and green spaces associated with gray infrastructure', a category which encompasses courtyards of educational infrastructure, such as elementary school playgrounds. Schoolyards are characterized by a combination of gray and green infrastructure. The elements of schoolyards that are characteristic of the UGI include trees, grasslands, raised beds and medium-height green elements, such as bushes, shrubs and hedges (see Figures 4–9). Examples of gray infrastructure include asphalt surfaces, sandboxes, playing fields (e.g. football and chess), playgrounds and climbing equipment, paths (paving stones, flagstones, etc.), gravel areas and safety slabs (Pauleit et al., 2019; Zwierzchowska et al., 2021; again, see Figures 4–9).

Elementary school children

Elementary school children spend a significant portion of their day at school. In addition, they often spend their breaks or afternoon care in the schoolyard. This is especially pertinent in large cities, where many children are deprived of the opportunity to experience nature and consequently lose awareness of their natural environment. Consequently, the presence of green schoolyards provides students with the opportunity to engage with nature and acquire a variety of experiences (Raith, 2017a). Moreover, the presence of urban natural areas in close proximity to children, whether within their immediate neighborhood, on their regular routes to and from educational institutions, or within the immediate environs of the school itself, has been demonstrated to exert a favorable influence on the health and well-being of children. Research on school greening has also indicated an improvement in academic performance through practical work and experimentation in and with nature (Williams and Dixon, 2013; Smith and Sobel, 2014). Lucas and Dyment (2010) found that students in schoolyards with natural green and blue elements exhibit higher levels of physical activity, and girls are also more likely to spend their recess time actively in green spaces. Asphalt schoolyards have been observed to encourage the participation of boys in sports and to create a social environment that is less conducive to the involvement of girls (Dyment et al., 2009). An improvement in the conditions for students' mental and social health can be observed in green schoolyards, as stress can be reduced and the natural landscapes can facilitate creative and cooperative play (Chawla et al., 2014). In the context of climate change and the prevalence of car traffic in urban areas (Gössling, 2020), the presence of UGI in schoolyards offers a natural refuge from the visual, auditory and (heat and air) polluting aspects of urban life. During the summer months, the canopies of large trees provide shade, thereby creating a habitat for a diverse fauna (Dyment and Bell, 2007).

Play behavior in children

Play behavior in children is a topic which has been extensively researched in the field of early childhood education. Indeed, it has been examined from infancy to school age (Chakravarthi, 2009). Play is defined as an intrinsically motivated, self-determined, meaningful and enjoyable activity involving symbolism, motivation, opportunism and creativity (Chakravarthi, 2009; Flannigan and Dietze, 2018). Smilansky's (1968) seminal work classified children's play based on cognitive development, while Frost et al. (2012) distinguish between physical, social, and cognitive play. Smilansky (1968) identifies four categories of play: functional, construction, dramatic/role, and rule-based. The remaining three types of play are all underpinned by functional play, which is defined as the initial movements and exploration of the infant's body, environment and behavior from infancy to kindergarten age. In the context of construction play, children have the opportunity to utilize a range of materials in the construction of various structures. The nature of role-playing games frequently entails the emulation of familiar conduct, a process that is typified by communication, interaction and creativity (Chakravarthi, 2009; Mogel, 2008).

The act of role-playing

The act of role-playing is a distinctive phenomenon in the context of UGI, as it demands a substantial degree of imagination and creativity that involves green elements. Through this process, children are able to create an imaginary play world, within which they transform objects, actions and even their own identity. The implementation of role-playing in an outdoor group context necessitates the employment of diverse cognitive strategies to facilitate the development and realistic execution of play themes. It is imperative that children possess the capacity to communicate both verbally and non-verbally, employing facial expressions and gestures as appropriate. Play actions also require planning, setting goals, solving problems, negotiating and coordinating (Bergen, 2002; Drown and Christensen, 2014). Through the utilization of role-playing, children are able to develop their capacity for abstract thinking, which is a prerequisite for academic success (Smilansky, 1968).

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that these activities foster the development of problem-solving skills, while concurrently enhancing the imagination, social interactions and other pertinent abilities of the individuals involved (Drown and Christensen, 2014). The cognitive, motor, emotional and linguistic skills that are generally trained by role-playing games are extensive. Indeed, the potential engagement of different brain areas is such that synaptic connections are strengthened, and new ones are created (Bergen, 2002). According to Vygotsky et al. (1980), role-playing constitutes a significant source of child development and represents the zone of proximal development, i.e. the difference between a child's current and potential developmental levels. It has been demonstrated that, during dramatic play, children have the capacity to exceed their current cognitive developmental level and attain higher levels of mental performance.

Outdoor environment

The outdoor environment exerts a significant influence on the play behavior of children, and this influence is multifaceted. As early as the 18th century, educational pioneers such as Rousseau, Fröbel, Dewey, Pestalozzi and Gandhi recognized the importance of a natural—green—environment for child development. It is evident that children derive knowledge from nature and necessitate the opportunity and liberty to explore, observe and experience it (Chakravarthi, 2009). However, environmental factors such as weather conditions also influence outdoor play and the variation in weather conditions throughout the year determines the utilization of outdoor recreational opportunities (Smith, 2017).

In addition to what has been explored the paragraphs above, the design of the surrounding nature has a significant impact on the activities and games that children engage in. Greening has been shown to promote active play behavior among children and to enhance the quality of play, thereby motivating a greater proportion of children to participate in activities (Mårtensson et al., 2014; Smith, 2017). As demonstrated by Änggård (2011), empirical research has indicated that green spaces serve as communal areas where children of diverse age groups, genders, and abilities engage in shared activities. These activities are distinguished by close interactions with the environment, in conjunction with non-verbal communication, and constantly shifting play locations, topics and partners (Mårtensson et al., 2014). The implementation of a greener approach in Australian schoolyards has been demonstrated to enhance the diversity of play activities and to foster an increased sense of affection among children toward their schoolyard environment (Dyment and Bell, 2007, 2008). Observational studies have demonstrated that the number of boys and girls engaging in physical activity in green environments is equal. Furthermore, a natural environment facilitates children's participation in light to moderate activities through open or free creative play (Dyment et al., 2009; Lucas and Dyment, 2010).

Materials and methods

Study area

The city of Leipzig in Germany was selected as the study area. Leipzig is located in the eastern region of Germany and possesses an urban area that encompasses an approximate area of 300 square kilometers. The city is located in a lowland bay on the Weiße Elster, Parthe, and Pleiße rivers. The UGI of the city of Leipzig consists of 896 hectares of public green spaces (parks, town squares, and others), among them 2,450 hectares of forest, 1,229 hectares of allotment gardens, 182 hectares of cemeteries, 1,101 hectares of water bodies, 61,063 street trees, 179.5 km of second-order watercourses, and 10,297 hectares of agricultural land. The system under discussion can be described as a ring-radial system. This consists of three green rings and radial green axes, predominantly oriented along waterways and their remnant floodplains. The innermost ring, otherwise designated the “Promenade Ring”, encompasses the city center and was constructed on the site of the former ramparts. The city of Leipzig is characterized by a “Green Ring” that is located between the continuously built-up city center and the residential area on the outskirts. This “Green Ring” primarily encompasses larger green areas, including the Leipzig floodplains. The outer green ring is located outside the urban settlement area and is composed primarily of agricultural and other open land, as well as smaller forest areas. The implementation of this strategy entails the delineation of the urban area and its environs, thereby counteracting the phenomenon of urban sprawl in peripheral regions.

The city has a population of 631,509 inhabitants (Office for Statistics and Elections, City of Leipzig, 2025), making it the eighth-largest city in Germany (DESTATIS, 2020). Since the year 2000, Leipzig's population has exhibited consistent growth, attributable to immigration from external regions and foreign countries, as well as a resurgence in birth rates following a nadir in the 1990s. Concurrent with population growth is an increased demand for places in educational institutions, particularly elementary schools. The Children and Youth Fund has reported a 2% increase in the number of primary school pupils in Leipzig. In 2024, Leipzig had 82 municipal and 12 private primary schools, with a total enrolment of approximately 22,000 pupils (Office for Statistics and Elections, City of Leipzig, 2025).

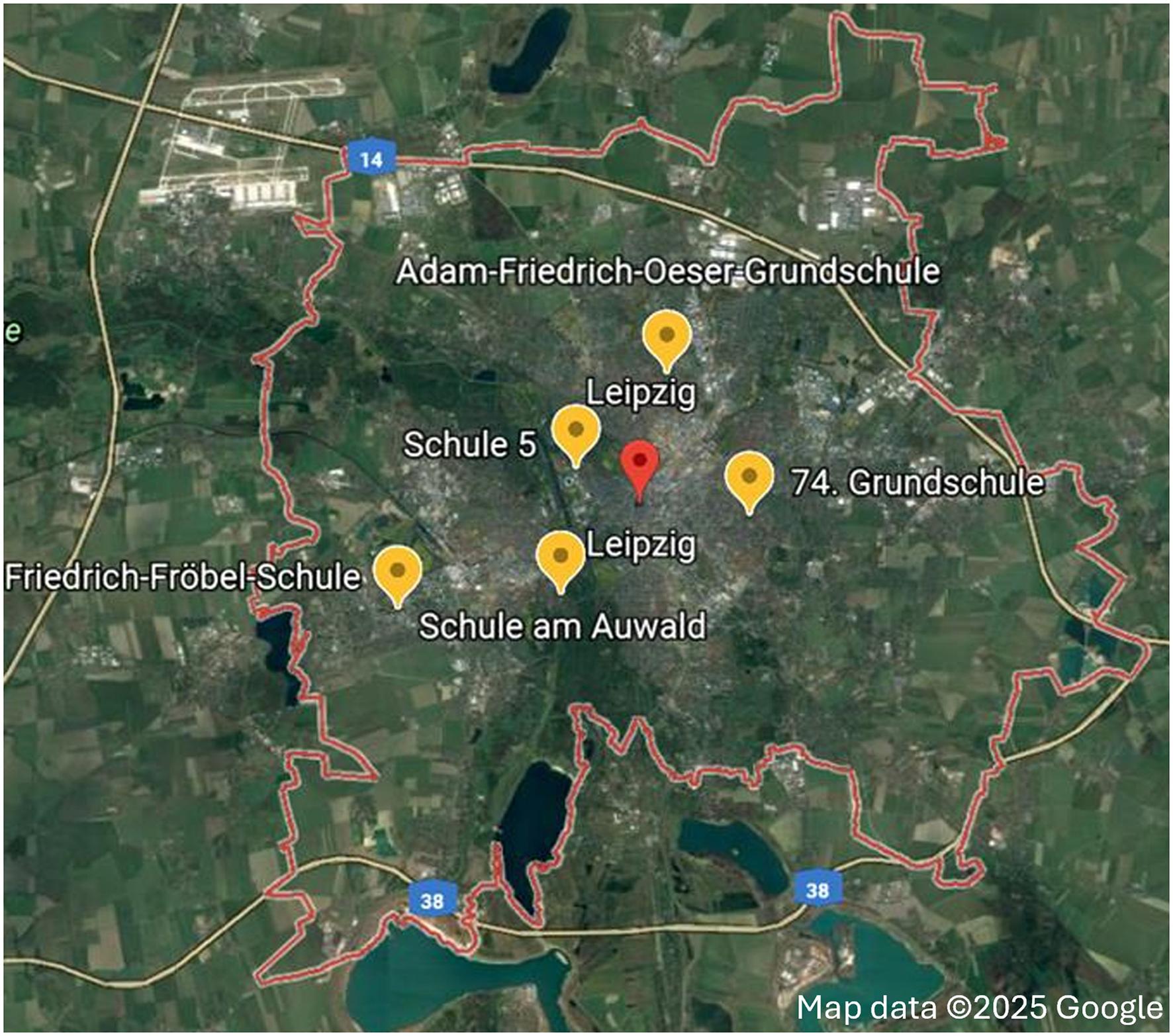

The case study schools for non-participant observation and mapping were selected using a statistical random number generator. To this end, public elementary schools were assigned to the five districts of Mitte, Nord, Süd, West and Ost within a corresponding database. This random selection process ensured the objective choice of elementary schools. In the central district, 5th School, located between the Leipzig Auwald forest and the Red Bull Arena, was chosen. In the Nord district, the Adam-Friedrich-Oeser Elementary School was selected; it is located next to the Arthur-Bretschneider-Park. In the Süd district, the “Auwald School” was selected. This school is located north of the Elster-Pleiße floodplain forest nature reserve. In the West district, the Friedrich-Fröbel-Primary School in the Grünau district was selected. In the Ost district, the 74th School at Ramdohrsch Park (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1

| School chosen for the study | District |

|---|---|

| (Auwald) School No 5 | Central |

| Adam-Friedrich-Oeser-School | North |

| Auwald School | South |

| Friedrich-Froebel-School | West |

| School No 74 | East |

Sample of the primary schools in Leipzig selected for this study.

Figure 1

Spatial distribution of the five selected primary schools (using Google Earth Pro).

Mapping the green and gray infrastructure of the schoolyards

To visually determine the connections between school children activities and the UGI of the schoolyards, maps of the selected schoolyards were created. These were initially sketched by hand on the observation days at each school, before the activity counting study began.

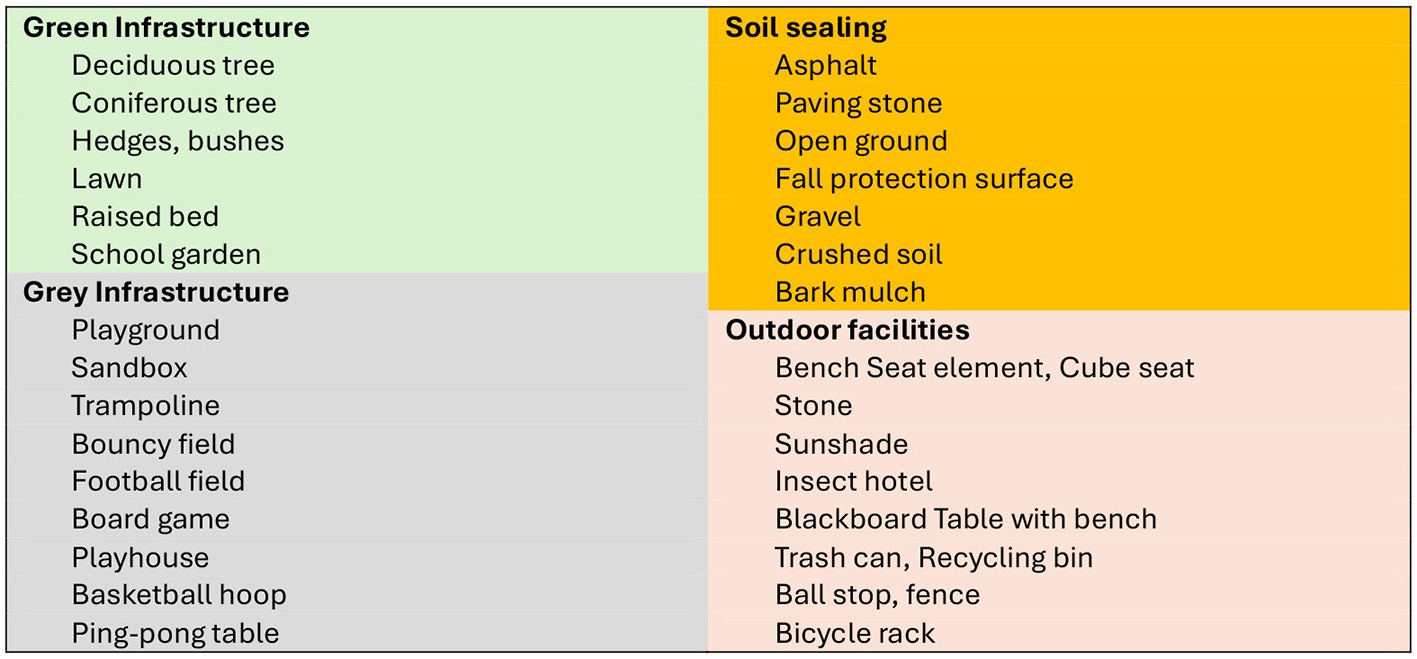

Categories of green and gray infrastructure

In order to facilitate the process of illustrating the elementary schools, satellite and map images of each school were obtained from Google Maps and printed for each site. These data facilitated the depiction of the larger edifices in relation to the other elements in the schoolyard. In order to capture as many elements of the schoolyard as possible in the mapping, a methodical approach was adopted. This entailed walking through the schoolyards and sketching them from the outside. Different hatchings and colors were used to distinguish between ground surfaces, deciduous and coniferous trees and medium-sized green elements. Symbols representing various elements were also sketched, including playgrounds, school gardens, insect hotels, playhouses, tables with benches, football pitches, table tennis tables, board games, bicycle racks, and wooden horses. A variety of shapes were utilized for seating elements and buildings. All sketches were then digitized to scale (see Supplementary material). For the digitized maps, similar colors, and shapes were used. The selection of pictograms for the painted symbols was informed by the principles of visual clarity and legibility. The map's background is the respective satellite image obtained from Google Earth Pro. Mapping categories and type of mapping were based on those used by Aminpour et al. (2020), Jansson et al. (2014), Mårtensson et al. (2014), and Tranter and Malone (2004).

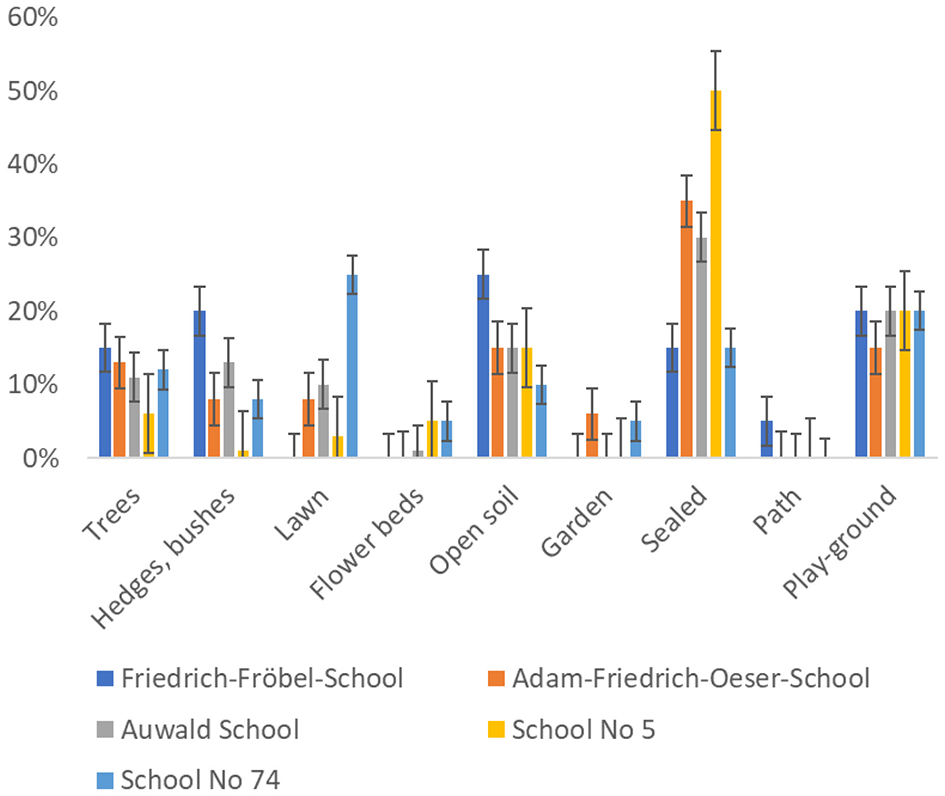

Data analysis

Descriptive median-statistics were performed, and ring diagrams were created to evaluate the mappings and estimate the respective proportions of green and gray infrastructure in the schoolyards. To this end, a table was created with two columns, one for green infrastructure and one for gray infrastructure, each of which was then divided into individual elements. For UGI, there were deciduous and coniferous trees, medium-height green elements, meadows, raised beds and school gardens. Gray infrastructure was divided into sealed ground (asphalt, stone or concrete paving, and fall protection surfaces), paths and play equipment (including areas around playgrounds, sandboxes, and other play elements) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mapping categories for green and gray infrastructure (see also resulting maps for the individual schoolyards in the Supplementary material).

Non-participatory observation of the playing activities

In the course of a non-participatory observation study, quantitative and qualitative data were collected over a period of 10 weekdays in early summer 2024, toward the end of the school year. Throughout the duration of the study, the weather conditions remained consistent, exhibiting a predominance of sunshine interspersed with periods of cloud cover. The temperature range observed was from 24 to 26°C. A quantitative analysis of the various activities present on gray and green infrastructure in the schoolyards was conducted using observation sheets. A meticulous record was kept of the qualitative observations of various play themes, including role play and dramatic play. The subsequent sections detail the development of the observation sheet and the observational study procedure.

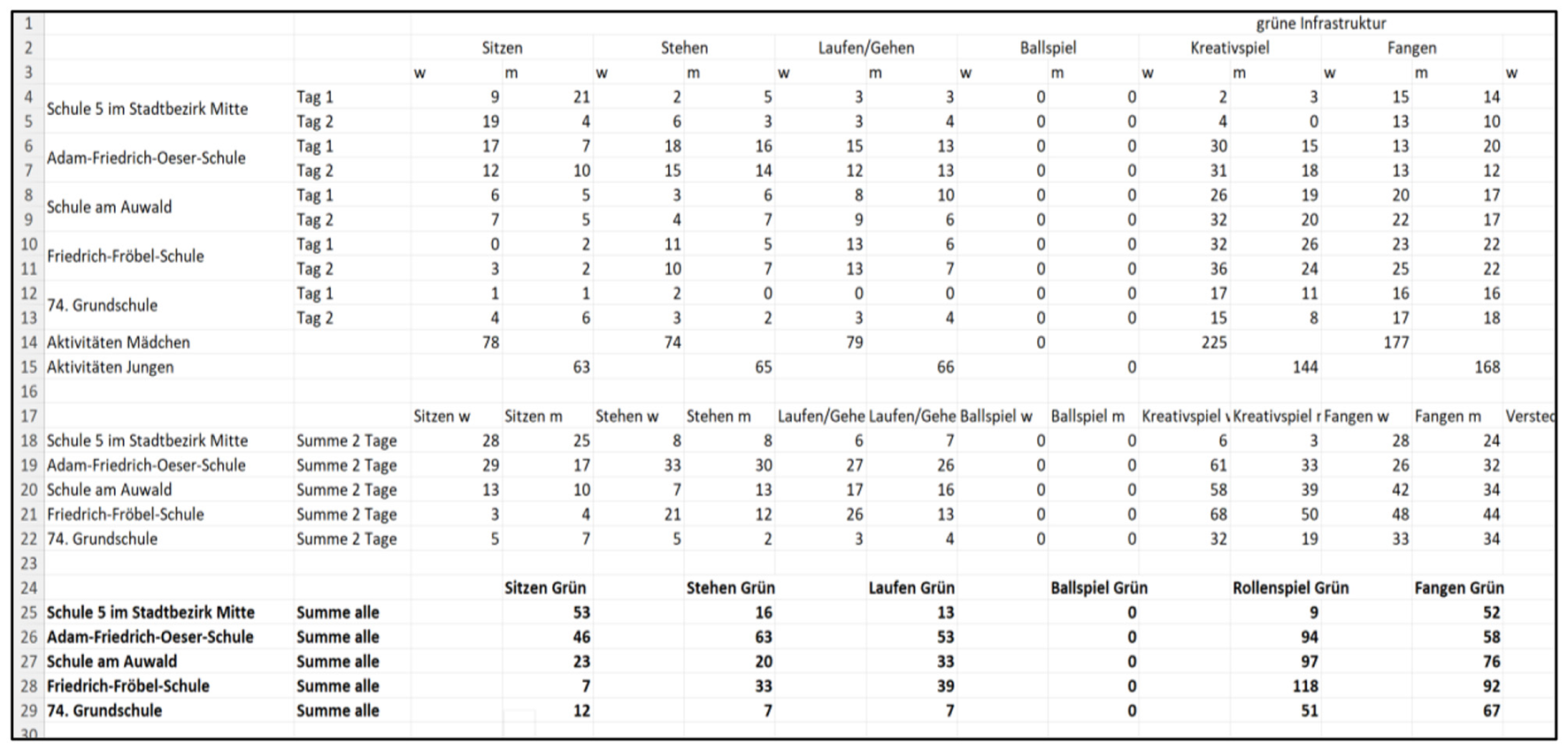

The observation tool

It was designed to facilitate the documentation of schoolyard activities. The associated database contains the following main categories: Activities, green infrastructure and gray infrastructure (Figure 3). Although the activities had been predetermined, they were open to potential inclusions. The final selection of activities comprised sitting, running/walking, standing, ball games, role-playing, tag, hide-and-seek, climbing/playing on the playground equipment, playing in the sandpit and rule-based games. These activities were then documented as individual detections, separated by gender. As the children could only be assessed based on their appearance, classification into diverse categories was omitted. Consequently, the analysis cannot be based on this subjective category.

Figure 3

Extract from the observation database.

The process of non-participant observation and data analysis

Elementary school recess periods were observed to take place between 9:30 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. Photographic documentation and mapping of the schoolyard were conducted before recess, without the presence of children, for reasons of data protection. During the observation phase, the schoolyard was observed from multiple vantage points to comprehensively document all observable activities. It was observed that, when observing from a greater distance, the children were not perceived as a distraction or observer. Consequently, any distortion of play behavior was avoided. The data collected from the observation sheets were analyzed in the aforementioned database with regard to relative frequencies for the various categories, variability of activities and total indices for girls and boys.

All data were transferred to a database (Figure 3), categorized and then analyzed using mean-based frequency statistics.

The non-participatory observation sessions at the five schools took place over a 6-week period during the summer semester (vegetation season), on regular school days (Monday to Friday). The observations were conducted from a considerable distance and there was no interaction with the children to ensure that they were not influenced by the observation. Therefore, observing children's behavior in this way does not constitute “research on humans” in an ethical sense.

Results

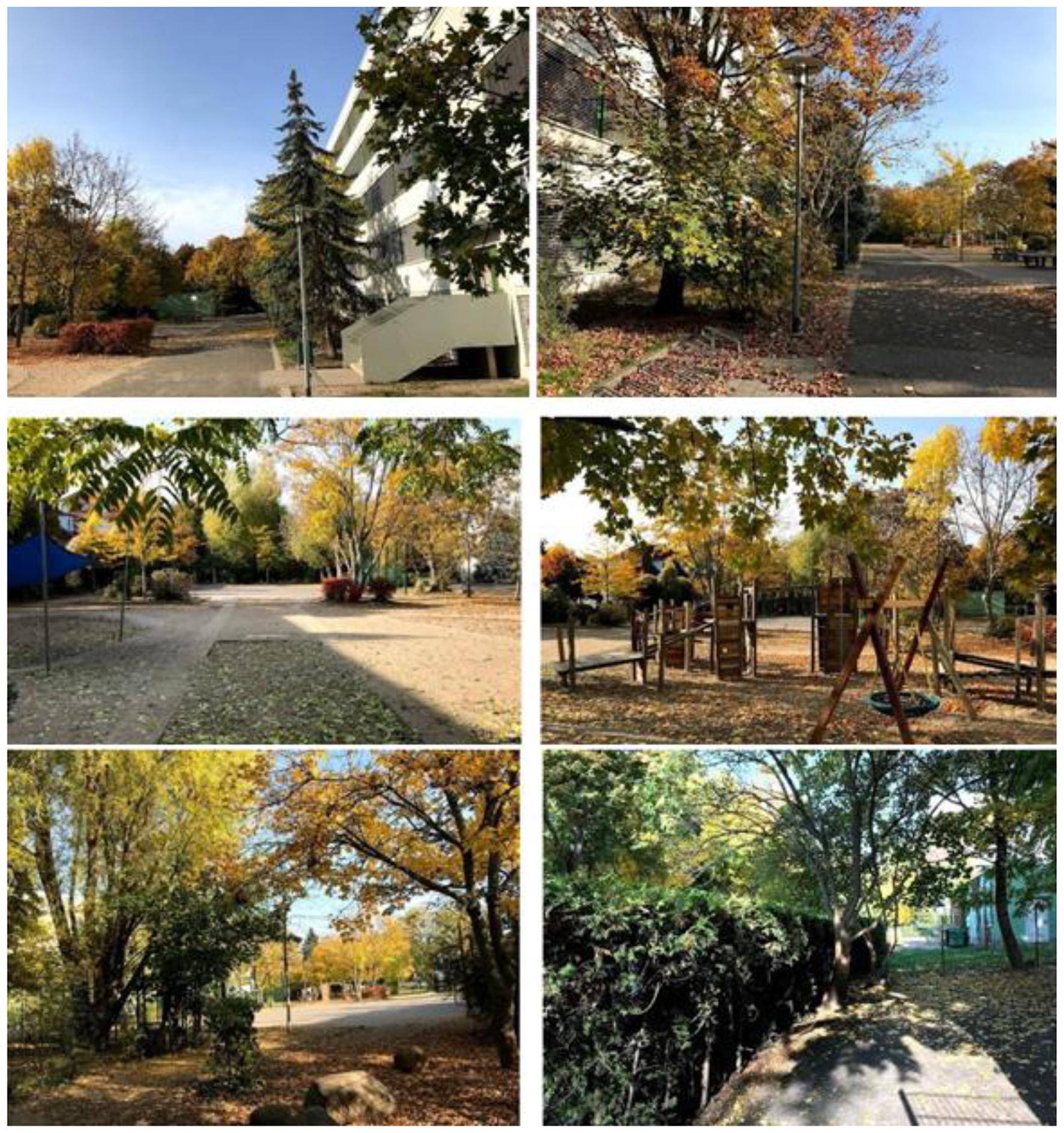

The subsequent section is devoted to the presentation of the results of the observations and the mapping of the schoolyards. Firstly, the elements of the UGI in schoolyards are introduced in detail. Figure 4 provides a comprehensive set of pictures that show all the elements of the UGI that were identified in the schoolyards that were examined. Deciduous trees, including maple, linden, and ash, in conjunction with a limited number of conifers, are present within the schoolyards, though they predominantly occupy the periphery of the grounds, adjacent to entrances or boundaries. A plethora of medium-height green elements, including bushes, shrubs, hedges, and meadows, are present in the majority of schoolyards. A survey of primary schools in the Mitte district revealed that two out of five of them do not have a meadow, with one school (Auwald School 5, Friedrich-Froebel-School) having only one shrub.

Figure 4

Elements of UGI, gray infrastructure, soil sealing and outdoor facilities in Leipzig's primary school playgrounds: Trees, hedgerows, lawns, flower beds, raised beds, sandboxes, sport fields, playgrounds, open soil and on the top of the building an extensive green roof. Adapted with permission from City of Leipzig, Leipzig.de by City of Leipzig, contract no. 101060429.

Furthermore, three out of five schools have also constructed raised beds in their schoolyards (namely, School 5, School at the Floodplains, and School 74). In addition, two schools have a school garden in the schoolyard. The school garden at the Friedrich Fröbel School is located off-site.

School 5

School 5 is located in the central “Mitte” district, in close proximity to the famous Red Bull Football Arena. The school building, which consists of container complexes, is the smallest in the sample and also has the highest proportion of sealed surfaces. Approximately 50% of the schoolyard is sealed ground, consisting of asphalt, safety mats and paving stones. Play equipment accounts for approximately 20%, which provides an estimated total gray infrastructure share of 70% (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S1a). The schoolyard's UGI accounts for an estimated 30% of the total yard area, consisting of 15% soil, 6% trees, 5% flowerbeds, 3% grass and 1% medium-height green elements. Despite its diminutive proportions, the schoolyard is equipped with a plethora of playground apparatus. In the top right corner of the image, there is a playhouse with a climbing roof. The following images depict a climbing frame and a set of wooden toy horses (Figure 5). This area is primarily used by girls. The subjects in question have been observed to ascend to the rooftop of the playhouse and the climbing frame. Within the domestic environment, and on the toy horses, they engage in role-play scenarios that emulate family life, holidays and horseback riding. Furthermore, ropes are incorporated into their role-play activities.

Figure 5

Features characterizing the School No 5. Upper left: Playhouse on fall protection floor, Upper right: Playhouse on fall protection floor, Middle left: Seating area with deciduous trees, Middle right: Board and climbing cube, Bottom left: Playing field and semicircular seating element, Bottom right: Lower play area with sandbox, raised beds, and open space (own photographs).

The role-playing element within the gray infrastructure accounts for 11% of the total. It is evident that all of these play elements are located on a safety surface. In the top left corner of the schoolyard is an asphalt football pitch (Figure 5), which is used almost exclusively by boys. Ball games constitute 16% of the gray infrastructure and represent the largest proportion of all schoolyard activities. The upper play area is delineated from the remainder of the schoolyard by a paved surface and raised beds. Adjacent to this, to the left, is a large dirt area with a significant number of trees (Figure 5), which provide shade for the tables and benches. It is estimated that 9% of the student population utilize this green area for sitting and resting purposes. In the left-hand corner, in close proximity to the fence, there is a blackboard, and directly beneath it is a climbing cube with a safety surface (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S1a). The children engage in a variety of physical activities, including hide-and-seek, catch, and climbing the climbing cube. Playing on and climbing playground equipment accounts for 12% of activities. In the lower section of the schoolyard, there is a sandbox, a table tennis table, raised garden beds, and an open asphalt area in the bottom left-hand corner, which is also utilized for ball games.

Adam Friedrich Oeser Elementary School

The Adam Friedrich Oeser Elementary School is located in the Nord district, next to the large Arthur Bretschneider Park. The schoolyard is estimated to consist of 50% gray infrastructure comprising 35% sealed ground (asphalt and paving stones) and 15% of the area designated for playground equipment and is covered in gravel, sand or pebbles (Figure 6). The remaining 50% is classified as green infrastructure, comprising 15% soil, 13% trees, 8% medium-height greenery, 8% grass and 6% a school garden (Supplementary Figure S1b). To the right of the schoolyard, there are a few deciduous trees, some of which cast their shade over the playground. Adjacent to the school building and in proximity to the access points leading to the schoolyard, there exist green spaces characterized by the presence of grass, deciduous and coniferous trees, in addition to medium-height green elements, including bushes and shrubs. The upper portion of the schoolyard is predominantly surfaced with asphalt, and is equipped with a table for ping-pong, a basketball hoop, outdoor seating, and individual trees (Supplementary Figure S1b).

Figure 6

Features characterizing the Adam Friedrich Oeser Elementary School. Upper left: Playhouse on fall protection floor, Upper right: Playhouse on fall protection floor, Middle left: Seating area with deciduous trees, Middle right: Board and climbing cube, Bottom left: Playing field and semicircular seating element, Bottom right: Lower play area with sandbox, raised beds, and open space (own photographs).

The area is primarily utilized by children for running (10%), standing (4%), sitting (8%), playing tag (4%), and playing regular games (7%). The majority of activities in this area of the schoolyard is accounted for by running accounts, which account for 10% of all activities. The schoolyard is bisected by a series of green spaces, with three distinct areas of grass, deciduous trees, and medium-height green elements. Benches are located in front of these. In the lower half of the field, a football pitch is delineated in the central area, surrounded by a ball-stop fence positioned behind each goal. In this context, too, football is predominantly played by boys. Ball games constitute the second most prevalent category of gray infrastructure activities, accounting for 8% of the total, a proportion similarly matched by playground activities. The playground and sandbox are located on the right-hand side of the schoolyard, separated from the football pitch on the left by deciduous trees. Conifers of medium height were planted along the fence in the bottom right-hand corner, and their needles only start growing at around 1.5 meters, which invites some children to play in this area.

An additional area of this nature is situated in the bottom left corner. This section of the schoolyard is characterized by a substantial presence of greenery, including trees, hedges and shrubs, which collectively provide a significant degree of shade. Large stones on the ground provide opportunities for students to climb or jump from stone to stone (Figure 6). It is estimated that approximately two-thirds of the students who participate in sporting activities at this institution are female. The present study found that 12% of students engage in role-playing games, constituting the largest proportion in the UGI, while 9% prefer to adopt a more concealed position within it. It has been observed that students make use of the gaps in the hedge, as well as the small spaces between shrubs and bushes (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure S1b).

Auwald School

The Auwald School is located in the southern district, which, as the name suggests, lies to the north of the Elster-Pleiße Floodplain Forest. The schoolyard is estimated to comprise again 50% gray infrastructure, 30% sealed ground and 20% playground equipment (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S1c). The remaining 50% of the UGI is comprised of 15% soil, 13% medium-height greenery, 11% trees, 10% meadow and 1% flowerbeds. The playground is well shielded from external observation by virtue of its UGI and is barely visible due to the dense vegetation in the vicinity of the fence. It is evident that students (9%) adopt a concealed position amidst the natural environment, specifically within shrubbery and trees, engaging in creative role-playing activities (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S1c). About 15% of UGI activities are accounted for by role-playing in the greenery. The incorporation of natural materials, such as sticks and leaves, into the play environment is a notable feature, and the utilization of the wooden playhouses located in the bottom left corner of the playground is also observed. The playhouses are situated in a clearing, which is surrounded by medium-height green elements and trees. The students engage in role-play, simulating a variety of scenarios, including family life, fantastical beings such as fairies, dinosaurs, and law enforcement figures, among others.

Figure 7

Features characterizing the Auwald School No 5. Upper left: Hiding places in half-height green elements and insect hotels, Upper right: Wooden playhouses, Middle left: Fenced meadow with raised beds and deciduous trees, Middle right: Climbing frame with bark mulch floor and playground in the background, Bottom: View of the green schoolyard of the school at the Auwald, raised beds, and open space (own photographs).

Playing tag accounts for 11% of UGI activities, and children demonstrate a high level of proficiency in turning and dodging between the green elements. In addition, the lower section of the schoolyard contains two sandboxes, two trampolines, an insect hotel and two playgrounds. Ball games in the gray infrastructure account for the second largest share at 11%. To the east of the football pitch are two meadows. The upper playground is enclosed by a fence and adjoins a recently constructed small school complex. There are a raised bed and several trees in a row on the lawn. Next to the large school building is a large asphalt playground, which has another playground and a sandbox. The gravel playground is bordered by four large, mature deciduous trees that provide shade. A large proportion of the playground activities observed in the gray infrastructure take place on this playground. Overall, 13% of the observed activities took place on the playgrounds. Students primarily use the asphalt surface for running (9%) and standing (6%). Another climbing frame with a bark mulch floor is used more frequently for sitting than climbing (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S1c).

Friedrich Fröbel School

The Friedrich Fröbel School is located in the Grünau district in the west of Leipzig and is surrounded by the Colonnade Garden, a local recreational facility. The perimeter of the site is delineated by a medium-height green fence, interspersed with trees, which serve to provide a natural barrier between the schoolyard and the adjacent area.

The schoolyard is composed of approximately 60% green infrastructure. The composition of the soil should be 25% inorganic material, 20% medium-height greenery and 15% trees. Approximately 40% of the schoolyard area is comprised of gray infrastructure, among them 20% for playground equipment, 15% to sealed surfaces, and 5% to paths made of paving stones and footpaths. There is a football pitch on the paved area in front of the school, which remains unused. In contrast to traditional football, a growing number of boys are opting for role-playing games in green spaces, constituting 19% of the total sample (Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure S1d). These activities manifest primarily the vicinity of the green classroom including medium-height green elements and equipped with tables, benches and a blackboard. It has been observed that students appear to feel unobserved in this half-height green setting, engaging in role-playing activities similar to those previously observed in elementary schools. The schoolyard is characterized by a playground with a gravel bed, which is utilized by children for climbing and playing (Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure S1d).

Figure 8

Features characterizing the Friedrich-Froebel-School. Upper left: Hiding places in half-height green elements and insect hotels, Upper right: Wooden playhouses, Middle left: Fenced meadow with raised beds and deciduous trees, Middle right: Climbing frame with bark mulch floor and playground in the background, Bottom: View of the green schoolyard of the school at the Auwald, raised beds, and open space (own photographs).

Most activities on the playground are categorized as gray infrastructure, accounting for 10%. Above the playground, there is a round sandpit and bouncy castles. Next to these is a curved area of brick dust and paving stones. These two areas are separated by a similarly curved seating area. Further to the left on the ground are some trampolines which the students rarely use. Two other play areas marked on the asphalt floor serve for chess and Ludo, but these are not used by students. The asphalt area is used for playing tag (8%), running (8%), standing (5%) and sitting (4%). However, 14% of tag games take place within the green infrastructure at the lower fence. Between the half-height green elements, players can easily lose sight of their catchers, and 10% of students also use these elements to hide (Supplementary Figure S1d).

74th Elementary School

The 74th Elementary School is located in the Reudnitz district in the inner east of Leipzig, adjacent to Ramdohrsch Park. The schoolyard is estimated to comprise 65% green infrastructure, including 25% grassland, 12% trees, 10% soil, 8% medium-height greenery, 5% a school garden and 5% flowerbeds. The remaining 40% gray infrastructure is comprised of 20% playground equipment and 15% sealed soil (Figure 9 and Supplementary Figure S1e). A substantial expanse of grassland extends from the lower fence to the school garden and playground. It is evident that a considerable number of trees are situated along both the lower fence and the fence that leads to the schoolyard. Medium-height green elements have been observed in the lower area adjacent to the trees and below the school garden. However, the substantial open meadow area is rarely utilized for activities in its own right, but rather in conjunction with the medium-height green elements and trees (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Features characterizing the 74th Elementary School. Upper left: Trees along the lower fence, Upper right: Large open meadow area, Middle left: Half-height green elements (hedges, bushes) below the school garden, Middle right: Playground and climbing frames, Bottom left: Football field, Bottom right: Meadow area next to the football field (own photographs).

Pupils have here the capacity to conceal themselves with ease behind these and partake in a game of catch. Role-playing activities can only be observed in close proximity to or in a position posterior to the medium-height green elements. The playground and climbing frame accounted for the largest proportion of activities, with 33% of all activities taking place there.

The tool shed and the gap behind it are utilized for the purposes of concealing (2%) and engaging in recreational activities (9%) within the gray infrastructure. The schoolyard is also equipped with an artificial turf football pitch (Figure 9), which is utilized exclusively by one class for a limited period. Adjacent to this is an additional grassy area where students who do not wish to participate in football activities can repose. In this setting as well, the participation in football is predominantly male, while female participation is limited to spectating or participation in games on the grass.

Following the presentation of the green and gray furnishings of Leipzig's primary school playgrounds and the subsequent observation of student activities, a comparative overview of the data is now presented. Respectively, and as demonstrated in Figure 10, the range of green and gray infrastructure coverage in the schoolyards of the analyzed Leipzig elementary schools is substantial, and the data do not provide a uniform picture. Consequently, the mean values are, at best, only approximate. As one of the most significant indicators, the proportion of soil sealing ranges from less than 20% to 50% and varies considerably overall. However, significant green elements such as trees (and the shade they provide) and hedges or shrubs, all of which have a cooling effect, vary between virtually 0% and 20% of the area.

Figure 10

Shares of green and gray infrastructure in all five primary school playgrounds examined, including the uncertainties regarding admission (own illustration).

This evidence clearly demonstrates that schoolyards are ill-equipped to cope with the effects of climate change. The presence of areas designated for plant diversity and biodiversity, such as flowerbeds or garden elements, is minimal to non-existent. The gray elements of open ground and playgrounds/play equipment are almost equally distributed across all analyzed schools, which is deterministic for the use of the schoolyards by elementary school students, as will be demonstrated below.

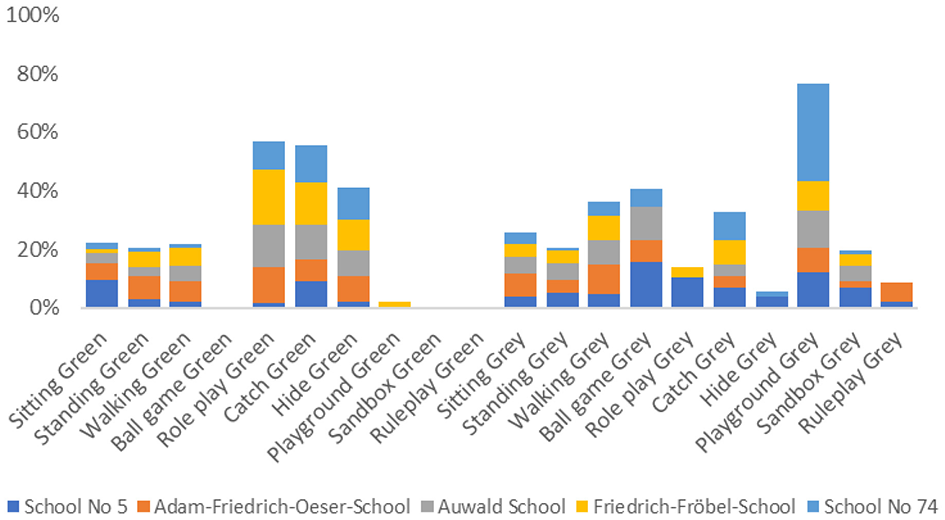

Figure 11 shows all schoolyard activities in green and gray infrastructure at all schools in the form of a bar chart. The x-axis shows the activities in the schoolyards, and the y-axis shows the percentage of each activity. Most activities are found in gray infrastructure on the playground (77%). Primary School 74 dominates this category, accounting for 33% of the observed activities, and the remainder are distributed relatively evenly among the other four primary schools.

Figure 11

Schoolyard activities in green and gray infrastructure at all primary schools studied (own illustration).

Role-playing in green infrastructure achieved the second-highest number of activities, accounting for 76% of the total. Notably and a bit counter-intuitive, School 5 in the floodplain forest area, which has the lowest proportion of UGI and only one half-height green element, despite its location in the most natural area the entire city has, reports the fewest role-playing activities in the green area (2%). Even at Primary School 74, which has the highest proportion of UGI of all the schoolyards but also a relatively low proportion of half-height green elements, only 10% of role-playing activities take place in green spaces. At the three remaining schools, a similar proportion of role-playing activities take place in green spaces, and the proportion of half-height green elements is higher (58%), except at the Adam-Friedrich-Oeser School. However, this school has a special feature in the form of a ‘green niche', which offers students a great deal of privacy. Tagging in green infrastructure comes third with a share of 55%. These activities are evenly distributed across all five schools. Hide-and-seek in green spaces comes fourth with 41% and School 5 has the fewest activities due to a lack of green hiding places. Ball games account for 41% of the total and are on par with hide-and-seek as part of the gray infrastructure. School 5, in turn, records the largest number of activities, accounting for 16%.

Soccer is not played in the schoolyard at the Friedrich Fröbel School, which is why it does not appear in this column. Running accounts for 37% of gray infrastructure activities and tag for 32%. Approximately 20% of green infrastructure activities are sitting, running and standing, and approximately 20% of gray infrastructure activities are sitting, standing and playing in the sandbox. Role-playing activities in the gray infrastructure can only be observed at School 5 and the Friedrich Fröbel School, accounting for 14%. The schoolyard at School 5 has wooden toy horses and a playhouse for role-playing. Rule-based play in the gray infrastructure is observed at 9% of School 5 and Adam Friedrich Oeser School. Finally, hide-and-seek in the gray infrastructure accounts for 6%, while play on the green playground accounts for just 2%. Ball games in green infrastructure cannot be observed in any of the schoolyards as the football pitches are not grassed and no ball games are played on the meadows. As the sandboxes are not connected to UGI, these activities are generally counted as gray infrastructure. No rule-based play in green infrastructure could be recorded in any of the schoolyards.

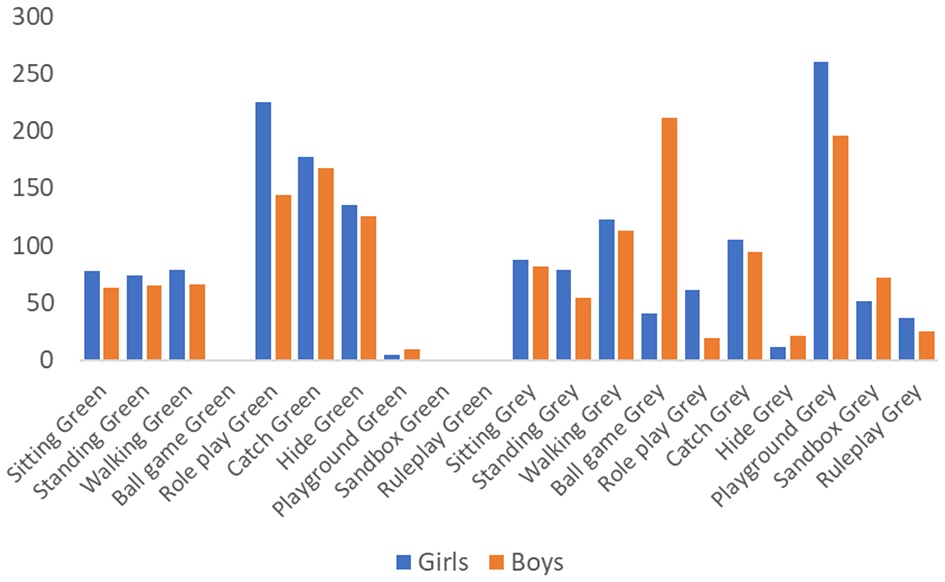

Figure 12 shows that role play is observed four times more frequently in green infrastructure than in gray infrastructure. Children clearly incorporate their green environment into their role play, using it as a house, cave or hiding place, for example, or creatively using natural materials such as sticks and leaves.

Figure 12

Comparison of the share of role-playing and hiding activities in green and gray infrastructure across all schools (own illustration).

They also use predefined play objects, such as playhouses or toy horses. Half-height green elements appear to play a key role as they are at child height, providing privacy for play. These differences are also clearly visible in games of hide-and-seek. Children hide five times more often in green infrastructure than in gray infrastructure.

As finally demonstrated in Figure 13, there is a marked difference between the utilization of green and gray infrastructure in schoolyards by girls and boys. It has been observed that girls are more inclined to utilize green spaces for individualistic and inventive forms of role-playing or concealment. In contrast, boys predominantly occupy prepared, gray sports fields for activities such as football, thereby utilizing an infrastructure that is clearly designated for its designated purpose.

Figure 13

Comparison of the share of role-playing and hiding activities in green and gray infrastructure between girls and boys (own illustration).

Discussion

Green and gray infrastructures

A direct comparison of the primary schools reveals that one is clearly inferior to the others in terms of its UGI equipment. As demonstrated in the Results section, Auwald School 5 in the central Mitte district exhibits a substantial presence of gray infrastructure, with the schoolyard predominantly characterized by gray hues, namely asphalt flooring, impact protection flooring and paving stones. The schoolyard is distinguished by its expansive, unobstructed layout, devoid of any natural or man-made barriers such as hedges. In contrast, the Adam-Friedrich-Oeser Primary School boasts a significantly greater abundance of green space, encompassing trees, medium-height green elements and meadows. The schoolyard is characterized by its compartmentalization, with distinct areas designated for specific activities. These areas include meadows, planting zones, and designated play areas. This results in variations in height, which contributes to the perception of a less flat appearance in comparison to School 5 and Primary School 74. A comparable compact structure and balance of green and gray infrastructure is evident in the Auwald School. The prevalence of medium-height green elements and arboreal features in the lower half of the schoolyard is immediately apparent. The Friedrich-Froebel-Schule schoolyard is distinguished by its curved and rounded design. The delineation of the individual spaces of the schoolyard is achieved by UGI through the implementation of mid-height green elements and trees, which serve to distinguish these zones from one another. It is noteworthy that only one schoolyard features a more expansive lawn area, given that this particular type of green infrastructure is also highly intuitive as ground cover for a schoolyard designed for elementary school students.

Structures and activities

The findings of this pilot study for Leipzig demonstrate that the UGI has different play priorities depending on its composition, a finding that is supported by literature: The study by Fjørtoft and Sageie (2000) indicates a relationship between landscape structures and play functions, a relationship that is also evident in the bar charts of all mappings. The paper posits the hypothesis that medium-height green elements, such as bushes and shrubs, encourage creative games, such as role-playing and hide-and-seek (Fjørtoft, 2001; Flade, 2018). The presence of unstructured natural environments and dispersed natural materials has been demonstrated to foster creativity in children and to encourage role play (Chawla, 2015; Flannigan and Dietze, 2018; Fjørtoft and Sageie, 2000). Hedges can function as refuges for children and as ecological corridors, as well as performing natural connecting roles (Naumann et al., 2011). This finding is in excellent agreement with the results found in Leipzig.

It has been further demonstrated by the Leipzig study that trees with low-lying branches can also be incorporated into creative play and used for climbing (supported by similar results reported by Fjørtoft, 2001; Chawla, 2015; Van Dijk-Wesselius et al., 2018). Furthermore, trees provide shade, thereby cooling parts of the schoolyard and allowing students to play comfortably, even during the hotter summer months (Kabisch, 2019; Pauleit et al., 2019). In addition, it has been demonstrated that trees have the capacity to enhance air quality (Haase et al., 2014a,b). Flat surfaces, such as meadows or ground, are primarily utilized for running activities (Fjørtoft and Sageie, 2000). It is evident, as demonstrated in the extant literature, that the Friedrich Fröbel School provides optimal conditions for creative play. The green infrastructure is high at 60%, and there is a significant proportion of mid-height green elements (20%). The schoolyard also features a tree with a curved shape that can be utilized in play activities. Auwald School 5 has been assigned the lowest ranking in this concern, with a mere 30% UGI and only 1% half-height green elements which results in a significantly constrained environment, offering minimal space for creative outdoor play.

Relationship between play behavior and schoolyard design

In this section, a more detailed examination of the individual activities observed is conducted, with a summary of these activities presented in Figures 11–13. The predominant element is playground play in the gray infrastructure, accounting for just over 75%, with almost half of the observed activities attributable to Elementary School 74. As previously stated, although this primary school has the largest share of UGI at 65%, the majority of this is grass (lawn), which is primarily used for running activities (Fjørtoft and Sageie, 2000). The configuration of the schoolyard, which is characterized by a lack of varied play and hiding opportunities, has a significant impact on the students' recreational habits. It has been observed that students tend to restrict their play to the playground due to the limited options available in the schoolyard. It is evident that all other schools collectively attain a maximum of 13%, a phenomenon that may be attributed to the existence of supplementary recreational alternatives and the shift in focus away from the playground.

The second most significant pillar is role-playing within the UGI. A more detailed examination of the individual bar charts in the mappings reveals that, with the exception of Schools 5 and 74, the role-play bar within the green infrastructure exhibits the highest values, ranging from 12% to 19%. The schoolyards of School 5 and Elementary School 74 are distinct from the other schoolyards in two respects. The presence of either a higher proportion of gray infrastructure and a paucity of mid-height green elements (School 5) or a higher proportion of UGI, albeit predominantly grassy (Elementary School 74) was observed. The schoolyard of Elementary School 74 contains a notably high proportion of mid-height green elements, amounting to 8%, yet these elements exhibit a more sporadic distribution compared to the aforementioned schoolyard.

It can therefore be posited that role-playing is motivated by UGI, but also by the arrangement of individual green elements, especially mid-height green elements (bushes, shrubs, hedges). When mid-height green elements form niches, these are used as natural play settings for role-playing and are often further developed with natural materials such as sticks (Derecik, 2013; Chawla, 2015; Chawla et al., 2014; Flannigan and Dietze, 2018). Mid-height green elements, such as shrubs, play a pivotal role in activities like hide-and-seek and tag games in green spaces (Fjørtoft and Sageie, 2000; Dyment and Bell, 2007). It has been demonstrated that trees have the capacity to function as a medium for creative play, provided that they possess low-lying branches or possess a distinctive shape, as evidenced by the case of a tree in the schoolyard of the Friedrich Fröbel School (Van Dijk-Wesselius et al., 2018; Fjørtoft, 2001). As the Friedrich Fröbel School has been determined to have the highest value in this category at 19%, it can be confirmed that the Friedrich Fröbel School offers the optimal conditions for creative play, as evidenced by the presence of the highest proportion of medium-height green elements. Subsequent to this, tag play/games form the third highest column, and all schoolyards are roughly equal in this activity, as tag games often only rely on objects to run around or hide around. These phenomena are ubiquitous in schoolyards.

The activities of hide-and-seek in the UGI and ball games in the gray infrastructure are on an equivalent percentage basis at 41%. As with the role-playing game, School 5 is distinctive in its low participation rate in hide-and-seek, with a mere 2% of students engaging in the activity. It is evident that all other primary schools have values that approximate 10%. This distribution can be explained by the low proportion of medium-height green elements, which are particularly suitable for students to play hide-and-seek, also due to their height (Fjørtoft and Sageie, 2000; Dyment and Bell, 2007). The prevalence of ball games in the schoolyard of School 5 is particularly notable, with the soccer field occupying an area equivalent to almost one-third of the entire schoolyard. This location is thus considered the most central and active point within the schoolyard. It has been confirmed by literature that, in general, the football facilities of the gray infrastructure are used primarily by male adolescents (Lucas and Dyment, 2010; Dyment et al., 2009).

Within the gray infrastructure, the pillar of catching follows, with the 74 Elementary School and the Friedrich Fröbel School having the largest shares and both having a sealed ground share of an estimated 15%. The remaining activities in the gray infrastructure, including sitting, standing, running in the green space and sitting, standing, playing in the sandbox, have approximate values of around 20% each. These activities are equally represented within the elementary school. The aforementioned values are contingent on various factors, including the configuration of the benches and the design of the pathways (Lucas and Dyment, 2010; Dyment et al., 2009).

The observation that role-playing and hide-and-seek occur with low or non-existent frequency within the gray infrastructure indicates that the encouragement of creative play is not possible within the confines of the gray infrastructure alone, and that the presence of additional play objects, such as playhouses, is a prerequisite for this to occur. It was solely at School 5 and the Friedrich Fröbel School that role-playing activities were permitted. At School 5, a playhouse and toy horses were found to have a stimulating effect on children's creativity, while at the Friedrich Fröbel School, a niche below the playground was found to have a similar effect.

Typification of the schoolyards

As demonstrated in the Results section, two distinct schoolyard types can be identified for individual elementary schools. The black arachnid in the gray infrastructure at Elementary School 74 is once again particularly prominent. As previously mentioned, there are discernible arrangements that determine a highly directed, one-sided play behavior. The UGI has been observed to be present almost exclusively within a corner of the schoolyard at Elementary School 74. Conversely, in the other schoolyards, green spaces and elements are distributed across the entire area and permeability is present. The schoolyards of the Adam-Friedrich-Oeser Elementary School and the School at the Auwald, for example, are characterized by a relatively diminutive, compartmentalized structure. It has been observed that the students at School 5 demonstrate comparable behavioral patterns, albeit in the context of the ball game (turquoise spider) within the gray infrastructure. This is due to the fact that the greatest variation is also found within the gray infrastructure at this school. The schoolyard is characterized by a centralized UGI infrastructure, which is substandard in terms of equipment and maintenance. This occurrence is notable for its singularity, as it has not been documented in any other elementary schools, suggesting an isolated nature.

The study results confirm, that UGI is disseminated across entirely the designated play areas, thereby delineating distinct zones for individual recreational pursuits. This phenomenon has been shown to engender green spaces that are conducive to creative play behaviors, such as role-playing and hide-and-seek (Derecik, 2013; Chawla, 2015; Chawla et al., 2014; Flannigan and Dietze, 2018). The spatial configuration of the schoolyards in question is indicative of the fact that they exert a significant influence on the behavioral patterns exhibited by young people in the context of UGI, particularly with regard to creativity and levels of physical activity. These schoolyards can be classified as “creative play in UGI” schoolyard type.

The integration of various chart types, including the donut, bar, column, and spider charts, has been employed to illustrate the notion that green infrastructure fosters creative play. The findings of this study are evident in the substantial discrepancy observed between role-playing and hide-and-seek in green and gray infrastructure. In the UGI, the values for role-playing are almost 60%, and within the gray infrastructure, it reaches just 12%. The values for hide-and-seek are consistent across both categories, with 41% in the UGI and 6% in the gray infrastructure. The UGI has been demonstrated to enhance students' play creativity to a significant degree, thereby demonstrating its potential to be “superior” in terms of developmental psychology, environmental impact, and social benefits when compared to conventional gray infrastructure. A correlation has been observed between schoolyards with the highest values for role-playing and hide-and-seek and the highest proportions of UGI, especially half-height green elements. For instance, creative play in the form of role-playing was observed in only two schoolyards, and these, in contrast to the other schools, had play elements, such as playhouses and horses, within the gray infrastructure. Exclusively the playground, occupying a central position within the configuration of all the schoolyards sampled, is promoting active play within the context of the gray infrastructure.

Limitations

This study is in its pilot phase, which means it has clear limitations. For example, the sample size is relatively small, but it was randomly generated and is well distributed across the city. Currently, only one observation season is available, and all observations were conducted by a single individual. Due to the small dataset, the analysis is purely descriptive at present, as no demographic or other contextual variables were available for the primary school classes. The author acknowledges the potential limitations imposed by the seasonality of the observations, the absence of children's voices and the limited sample size typical of a pilot study.

Conclusions

The objective of this pilot study was to ascertain the extent to which the presence of UGI in schoolyards influences the play behavior of elementary school children. Furthermore, the focus was directed toward the individual green elements of the UGI, and their utilization and incorporation into students' games was meticulously observed. The results were obtained through a non-participant observation study of schoolyards at five schools in the city of Leipzig, Germany, and their mapping. The research findings demonstrate that UGI exerts a significant influence on the play behavior of elementary school children, with a particular emphasis on the promotion of creative play. The study clearly shows that not all green infrastructure is equally important for outdoor activities by schoolchildren, and that the presence of mid-height vegetation in particular plays a key role in encouraging creative play, rather than the overall amount of green space.

It is evident from the findings of this study that UGI should be accorded greater consideration in the realm of schoolyard planning. The results indicate a quantifiable positive effect of UGI on children, thereby underscoring its potential to promote their mental and physical health, learning abilities, and creativity. Consequently, from an urban policy perspective, the results of this study should be considered when planning future schoolyards and redesigning existing ones, with a view to creating an optimal learning and recreational environment for students. It is recommended that educational institutions be provided with financial assistance, and that a minimum proportion of UGI be stipulated in architectural blueprints.

In the context of future research in this domain, it would be advantageous to extend the present study to encompass a greater number of elementary schools, with a view to consolidating the existing body of evidence. From the standpoint of environmental education, it would be intriguing to observe how students from different school types, such as grammar schools, behave in schoolyards that feature a greater abundance of greenery. Doing so, interviews should be conducted with school children to ascertain their subjective perceptions regarding the concept of green schoolyards. What is more, data from a range of school types, be it state or private, could be collated, and a recommendation could be published regarding the respective role of UGI in schoolyards and their impact on young school children.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The article processing charge was funded by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Conflict of interest

The author declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The Graphical Abstract was created using Napkin AI.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2025.1743481/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aminpour F. Bishop K. Corkery L. (2020). The hidden value of in-between spaces for children's self-directed play within outdoor school environments. Landsc. Urban Plan.194:103683. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103683

2

Änggård E. (2011). Children's gendered and non-gendered play in natural spaces. Child. Youth Environ.21, 5–33. doi: 10.1353/cye.2011.0008

3

Annerstedt M. Ostergren P. O. Björk J. Grahn P. Skärbäck E. Währborg P. (2012). Green qualities in the neighbourhood and mental health - results from a longitudinal cohort study in Southern Sweden. BMC Public Health12:337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-337

4

Barber A. Haase D. Wolff M. (2021). Permeability of the city – physical barriers of and in urban green spaces in the city of Halle, Germany. Ecol. Indic.125:107555. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107555

5

Bergen D. (2002). The role of pretend play in children's cognitive development. Early Child. Res. Pract. 4. Available online at: https://ecrp.illinois.edu/v4n1/bergen.html (Accessed December 15, 2025).

6

Chakravarthi S. (2009). Preschool teachers' beliefs and practices of outdoor play and outdoor environments (Doctoral dissertation). The University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC. Available online at: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/chakravarthi_uncg_0154d_10074.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2025).

7

Chawla L. (2015). Benefits of nature contact for children. J. Plann. Lit.30, 433–452. doi: 10.1177/0885412215595441

8

Chawla L. Keena K. Pevec I. Stanley E. (2014). Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place28, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.001

9

Derecik A. (2013). Das potenzial des schulhofs für die entwicklung von heranwachsenden. Sportwiss43, 34–46. German. doi: 10.1007/s12662-012-0272-6

10

DESTATIS (2020). Available online at: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Home/_inhalt.html (Accessed December 15, 2025).

11

Douglas O. Lennon M. Scott M. (2017). Green space benefits for health and well-being: a life-course approach for urban planning, design and management. Cities66, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.03.011

12

Drown K. K. C. Christensen K. M. (2014). Dramatic play affordances of natural and manufactured outdoor settings for preschool-aged children. Child. Youth Environ.24:53. doi: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.24.2.0053

13

Dushkova D. Haase D. (2020). Not simply green: nature-based solutions as a concept and practical approach for sustainability studies and planning agendas in cities. Land9:19. doi: 10.3390/land9010019

14

Dyment J. E. Bell A. C. (2007). Active by design: promoting physical activity through school ground greening. Child. Geogr.5, 463–477. doi: 10.1080/14733280701631965

15

Dyment J. E. Bell A. C. (2008). ‘Our garden is colour blind, inclusive and warm': reflections on green school grounds and social inclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ.12, 169–183. doi: 10.1080/13603110600855671

16

Dyment J. E. Bell A. C. Lucas A. J. (2009). The relationship between school ground design and intensity of physical activity. Child. Geogr.7, 261–276. doi: 10.1080/14733280903024423

17

Elmqvist T. Andersson E. McPhearson T. Bai X. Bettencourt L. Brondizio E. et al . (2021). Urbanization in and for the anthropocene. npj Urban Sustain1:6. doi: 10.1038/s42949-021-00018-w

18

Fjørtoft I. (2001). The natural environment as a playground for children: the impact of outdoor play activities in pre-primary school children. Early Child. Educ. J.29, 111–117. doi: 10.1023/A:1012576913074

19

Fjørtoft I. Sageie J. (2000). The natural environment as a playground for children. Landsc. Urban Plan.48, 83–97. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00045-1

20

Flade A. (2018). Zurück Zur Natur?Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. German.

21

Flannigan C. Dietze B. (2018). Children, outdoor play, and loose parts. J. Child. Stud. 53–60. doi: 10.18357/jcs.v42i4.18103

22

Frost J. L. Wortham S. C. Reifel R. S. (2012). Play And Child Development, 4th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson.

23

Gómez-Baggethun E. Barton D. N. (2013). Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ.86, 235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.019

24

Gómez-Baggethun E. Gren Å. Barton D. N. Langemeyer J. McPhearson T. O'Farrell P. et al . (2013). “Urban ecosystem services,” in Urbanization, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Challenges and Opportunities, Eds. T. Elmqvist, M. Fragkias, J. Goodness, B. Güneralp, P. J. Marcotullio, R. I. McDonald, et al. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands) 175–251.

25

Gössling S. (2020). Why cities need to take road space from cars - and how this could be done. J. Urban Des.25, 443–448. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2020.1727318

26

Groot R. S. de Wilson, M. A. Boumans R. M. J. (2002). A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ.41, 393–408. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7

27

Haase D. (2020). “The effects of greening cities on climate change mitigation and adaptation,” in Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation, Eds. M. Lackner, B. Sajjadi, and W. Y. Chen (New York, NY: Springer New York), 1–19.

28

Haase D. (2025). Sponge city in existing housing stock – more of a dream or reality?Front. Environ. Sci. Sec. Social-Ecological Urban Syst.13:1653240. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1653240

29

Haase D. Haase A. Rink D. (2014a). Conceptualizing the nexus between urban shrinkage and ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan.132, 159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.003

30

Haase D. Larondelle N. Andersson E. Artmann M. Borgström S. Breuste J. et al . (2014b). A quantitative review of urban ecosystem services assessment: concepts, models and implementation. Ambio43, 413–433. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0504-0

31

Jansson M. Gunnarsson A. Mårtensson F. Andersson S. (2014). Children's perspectives on vegetation establishment: implications for school ground greening. Urban For. Urban Green.13, 166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.09.003

32

Kabisch N. (2019). “Urban ecosystem service provision and social-environmental justice in the city of Leipzig, Germany,” in Atlas of Ecosystem Services, Eds. M. Schröter, A. Bonn, S. Klotz, R. Seppelt, and C. Baessler (Cham: Springer International Publishing) 347–352.

33

Kabisch N. Haase D. van den Annerstedt Bosch M. (2016a). Adding natural areas to social indicators of intra-urban health inequalities among children: a case study from Berlin, Germany. IJERPH13:783. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13080783

34

Kabisch N. Strohbach M. Haase D. Kronenberg J. (2016b). Urban green space availability in European cities. Ecol. Indic.70, 586–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.02.029

35

Lucas A. J. Dyment J. E. (2010). Where do children choose to play on the school ground? The influence of green design. Educ. 3–13, 177–189. doi: 10.1080/03004270903130812

36

Mårtensson F. Jansson M. Johansson M. Raustorp A. Kylin M. Boldemann C. (2014). The role of greenery for physical activity play at school grounds. Urban For. Urban Green.13, 103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.10.003

37

Mogel H. (2008). Psychologie Des Kinderspiels. Von Den Frühesten Spielen Bis Zum Computerspiel; Die Bedeutung Des Spiels Als Lebensform Des Kindes, Seine Funktion Und Wirksamkeit Für Die Kindliche Entwicklung; Mit 6 Tabellen, 3rd ed.Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. German. Available online at: http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10257927 (Accessed December 15, 2025).

38

Naumann S. McKenna D. Kaphengst T. Pieterse M. Rayment M. (2011). Design, implementation and cost elements of Green Infrastructure projects. Final report to the European Commission, DG Environment, Contract no. 070307/2010/577182/ETU/F.1. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/enveco/biodiversity/pdf/GI_DICE_FinalReport.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2025).

39

Office for Statistics and Elections City of Leipzig. (2025). Office for Statistics and Elections, City of Leipzig. Available online at: https://www.leipzig.de/buergerservice-und-verwaltung/aemter-und-behoerdengaenge/behoerden-und-dienstleistungen/dienststelle/statistik-und-wahlen-amt-fuer-12 (Accessed December 15, 2025).

40

Pauleit S. Ambrose-Oji B. Andersson E. Anton B. Buijs A. Haase D. et al . (2019). Advancing urban green infrastructure in Europe: outcomes and reflections from the GREEN SURGE project. Urban For. Urban Green.40, 4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2018.10.006

41

Raith A. (2017a). Children on green schoolyards: nature experience, preferences, and behavior. Child. Youth Environ.27:91. doi: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.27.1.0091

42

Raith A. (2017b). Das Potential Naturnah Gestalteter Schulhöfe Für Informelle Naturerfahrungen (Dissertation). Pädagogische Hochschule Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg. German.

43

Schipperijn J. Stigsdotter U. K. Randrup T. B. Troelsen J. (2010). Influences on the use of urban green space – a case study in Odense, Denmark. Urban For. Urban Green.9, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2009.09.002

44

Schwarz N. Haase A. Haase D. Kabisch N. Kabisch S. Liebelt V. et al . (2021). How are urban green spaces and residential development related? A synopsis of multi-perspective analyses for Leipzig, Germany. Land10:630. doi: 10.3390/land10060630

45

Smilansky S. (1968). The Effects of Sociodramatic Play On Disadvantaged Preschool Children. New York, NY: Wiley and Sons.

46

Smith G. A. Sobel D. (2014). Place- And Community-Based Education In Schools.New York, NY: Routledge.

47

Smith P. K. (2017). Children's Play. Research Developments And Practical Applications 1st ed.Milton: Taylor and Francis (Psychology Library Editions, v.14). Available online at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gbv/detail.action?docID=5178522 (Accessed December 15, 2025).

48

Tranter P. J. Malone K. (2004). Geographies of environmental learning: an exploration of children's use of school grounds. Child. Geogr.2, 131–155. doi: 10.1080/1473328032000168813

49

Van Dijk-Wesselius J. E. Maas J. Hovinga D. van Vugt M. van den Berg A. E. (2018). The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: a prospective intervention study. Landsc. Urban Plan.180, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.08.003

50

Vygotsky L. S. Cole M. Jolm-Steiner V. Scribner S. Souberman E. (Eds.). (1980). Mind In Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

51

Ward Thompson C. Roe J. Aspinall P. Mitchell R. Clow A. Miller D. (2012). More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan.105, 221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015

52

Williams D. R. Dixon P. S. (2013). Impact of garden-based learning on academic outcomes in schools. Rev. Educ. Res.83, 211–235. doi: 10.3102/0034654313475824

53

World Health Organization (2017). Urban Green Space Interventions And Health. A Review Of Impacts And Effectiveness.

54

Zwierzchowska I. Haase D. Dushkova D. (2021). Discovering the environmental potential of multi-family residential areas for nature-based solutions. A Central European cities perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan.206:103975. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103975

Summary

Keywords

creative play, green infrastructure, gray infrastructure, mid-height green, outdoor activities, primary schools, schoolyards

Citation

Haase D (2026) Unveiling the impact of green infrastructure on children's play in primary school open spaces an empirical pilot case study from Leipzig, Germany. Front. Sustain. Cities 7:1743481. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2025.1743481

Received

10 November 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

05 December 2025

Published

09 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Kumelachew Yeshitela Habtemariam, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Reviewed by

Diogo Guedes Vidal, Universidade Aberta, Portugal