Abstract

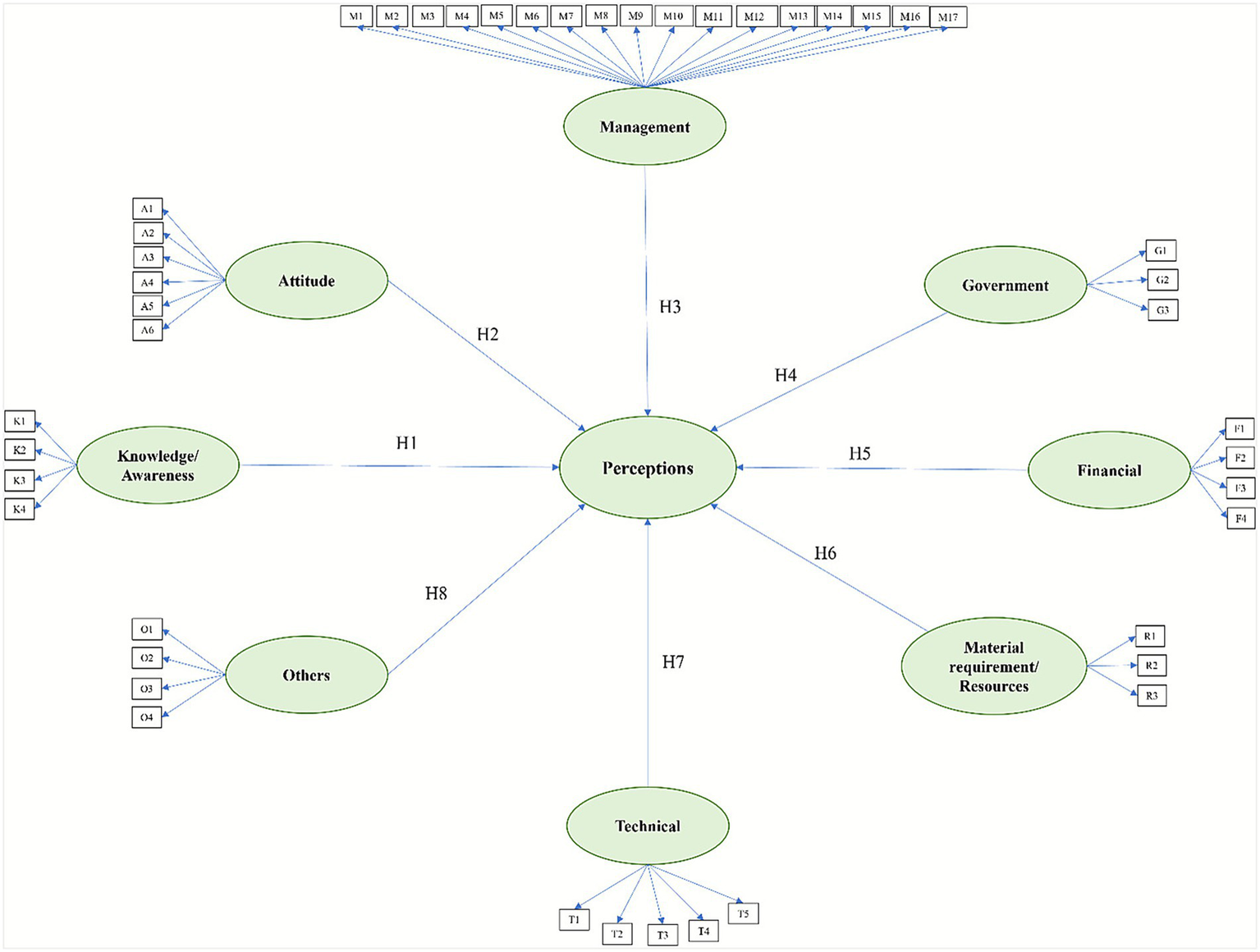

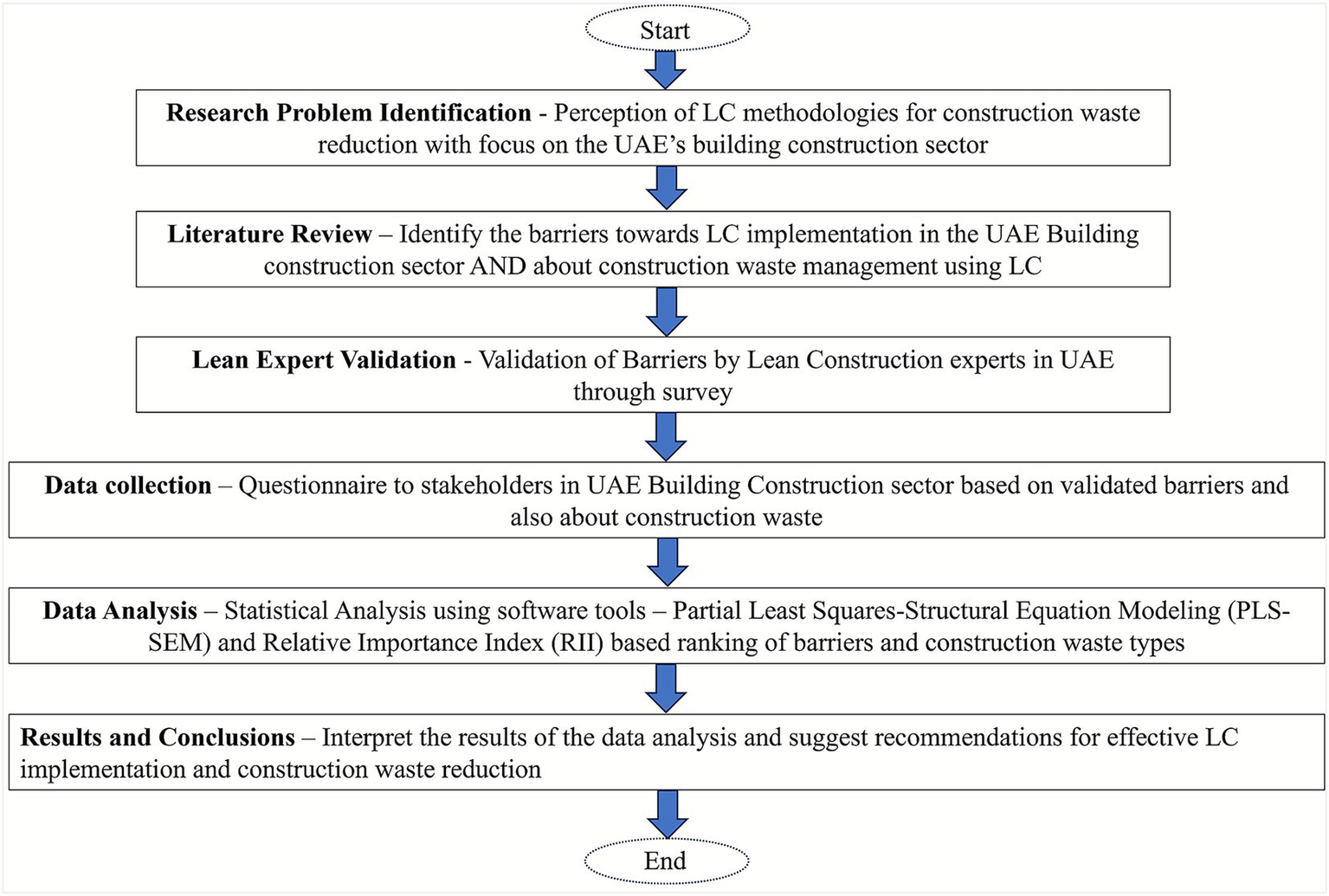

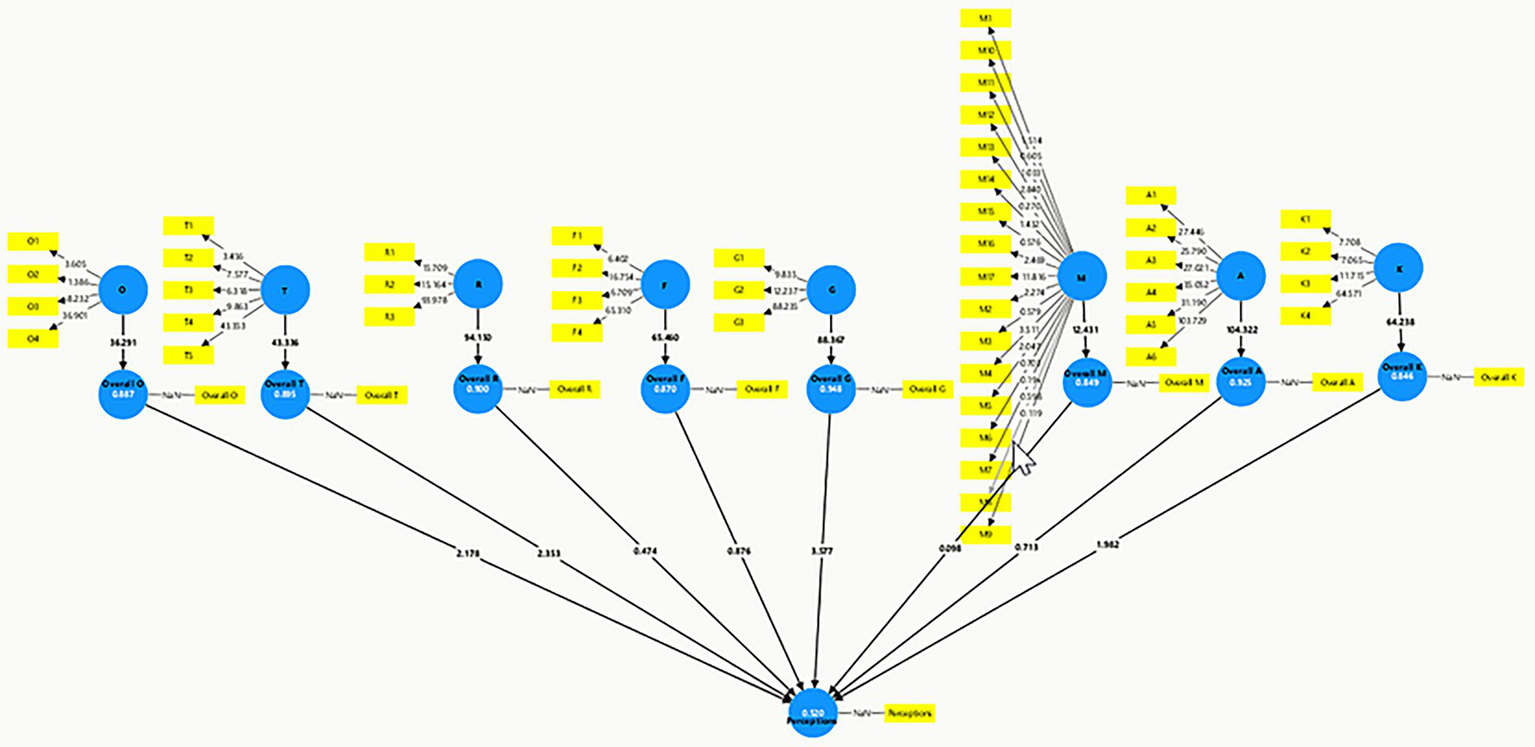

Despite having a significant socio-economic impact on a country’s growth, one of the biggest contributors to waste generation is the construction sector, thus increasing the necessity for innovative construction waste management strategies. Lean Construction (LC) is a much-adopted methodology that helps manage construction waste efficiently. This study investigates the barriers to LC implementation in the UAE’s building construction sector, with a specific focus on its potential for effective construction waste management. Recognizing the urgent need to adopt sustainable practices in the face of escalating environmental concerns, the study employs a quantitative exploratory approach combining literature synthesis, expert validation, descriptive statistical analysis, Relative Importance Index (RII) ranking, and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to examine stakeholder perceptions across eight critical categories: Knowledge/Awareness, Attitude, Management, Government, Financial, Material/Resource, Technical, and Other contextual factors. The RII analysis ranks these barriers based on stakeholder responses, while the PLS-SEM approach models the strength and significance of their interrelationships within a validated structural framework. The findings reveal that while all eight categories significantly influence stakeholder perceptions, Attitude and Management factors exhibit the strongest impact, highlighting the importance of behavioral and organizational readiness in enabling LC adoption. The key deliverable of this research is a validated and empirically supported structural model that provides a strategic roadmap for overcoming resistance to LC implementation. By offering actionable insights into which barriers matter most and how they interact, the study equips policymakers, contractors, and industry stakeholders with evidence-based guidance to design targeted interventions. Ultimately, this research contributes to the growing discourse on sustainable construction by positioning LC as a viable pathway for reducing construction waste and improving efficiency in the UAE context.

1 Introduction

The construction industry is crucial for the socio-economic development of a nation as it significantly helps improve its residents’ standards of living by providing fundamental and enhanced infrastructure, such as roads, hospitals, schools and others. However, this industry is also one of the most significant contributors toward waste, thus, also affecting the need for new and innovative methods of effective waste management.

In this regard, the construction industry is held accountable for its various unsustainable practices including the use of non-renewable resources, the production of waste, energy and water consumption, and pollution, the most detrimental being the construction waste generation (Sadi et al., 2012). The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (US EPA-OLEM, 2016) defines construction and demolition (C&D) waste as the waste produced during the construction, refurbishment, and destruction of buildings, roads, and bridges. It contains a wide variety of materials such as concrete, bricks, wood, glass, metals, plastic, dust and more.

As per an article by British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) (Miller, 2021), a third of the world’s waste and at least 40% of its carbon dioxide emissions are estimated to come from the construction sector. Further, according to the EPA’s (US EPA-OLEM, 2016) 2018 waste characterization report, the United States generated 600 million tons of construction and demolition waste in 2018, which was more than twice that of municipal solid waste. Likewise, in 2020, more than 37% of all waste produced in the European Union came from C&D operations (Statista, 2021).

Additionally, in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the waste generated from the construction industry accounts for the largest share of the total waste produced in the country. In 2021, the Emirate of Abu Dhabi alone produced about 10.4 million tons of solid waste, of which, 37% of the non-hazardous solid waste was solely from the C&D sector (Environmental Environmental Agency—Abu Dhabi, 2022). Similarly, with an estimated 77 million metric tons produced in 2022, construction waste was, by far, the most prevalent kind of waste produced in Dubai (Saleh, 2023). Consequently, a significant amount of collected waste, including those from the C&D industry, eventually ends up in dumps or landfills outside of major cities. These landfills or dumpsites might not be designed to handle the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, waste sludge, odor, and soil and water contamination that follow, hence, leading to disastrous consequences on the environment and human health. Thus, in light of these increasing threats posed by the C&D waste, implementation of new and effective construction waste management approaches is of utmost importance. The Lean Construction (LC) approach is one such method.

Furthermore, the adoption of LC aligns closely with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) (United Nations, 2015). By promoting process efficiency, minimizing resource waste, and optimizing material flow throughout the project lifecycle, LC contributes directly to sustainable urban development and responsible production practices. Within the UAE’s construction context, where waste minimization is a key national priority, enhancing LC adoption supports not only operational efficiency but also the broader transition toward sustainable and circular built-environment practices.

While LC has demonstrated strong global uptake in countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, among others, driven by advanced procurement systems, robust training ecosystems, and integrated project delivery models, its application within the distinct regulatory and industrial environment of the UAE remains relatively limited. Despite the UAE’s strategic emphasis on sustainability through initiatives such as Vision 2030 and Net Zero by 2050, LC has not yet been widely institutionalized within mainstream construction practices. The UAE’s construction sector presents a unique set of challenges. These contextual differences limit the direct transferability of global LC solutions and necessitate locally grounded research. Moreover, although international literature emphasizes LC’s benefits for waste reduction, empirical studies investigating how UAE stakeholders perceive its barriers and applicability are scarce, especially using quantitative frameworks. This study addresses this gap by exploring how key organizational, managerial, and contextual factors influence perceptions of LC implementation in the UAE’s building sector, using a structural modeling approach to uncover patterns unique to this regional context. Accordingly, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

What are the main barriers to implementation of LC methodologies for waste management in the UAE building construction sector, and how are these barriers associated with specific construction and Lean waste types across project phases?

How do stakeholders in the UAE’s building construction sector perceive these barriers, and which of these barriers exert the most significant influence on their perceptions of LC adoption?

What are the most commonly found construction waste types in the UAE building construction sector, and how do stakeholder-perceived barriers translate into construction waste generation patterns across different construction project phases?

To address this, a dual-method approach was adopted, integrating Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and Relative Importance Index (RII) techniques to quantify both conceptual influences and practical waste manifestations. This enables a systems-level understanding of how various factors interact to shape LC implementation and its impact on waste management outcomes.

2 Literature review

2.1 Lean construction

2.1.1 Origin

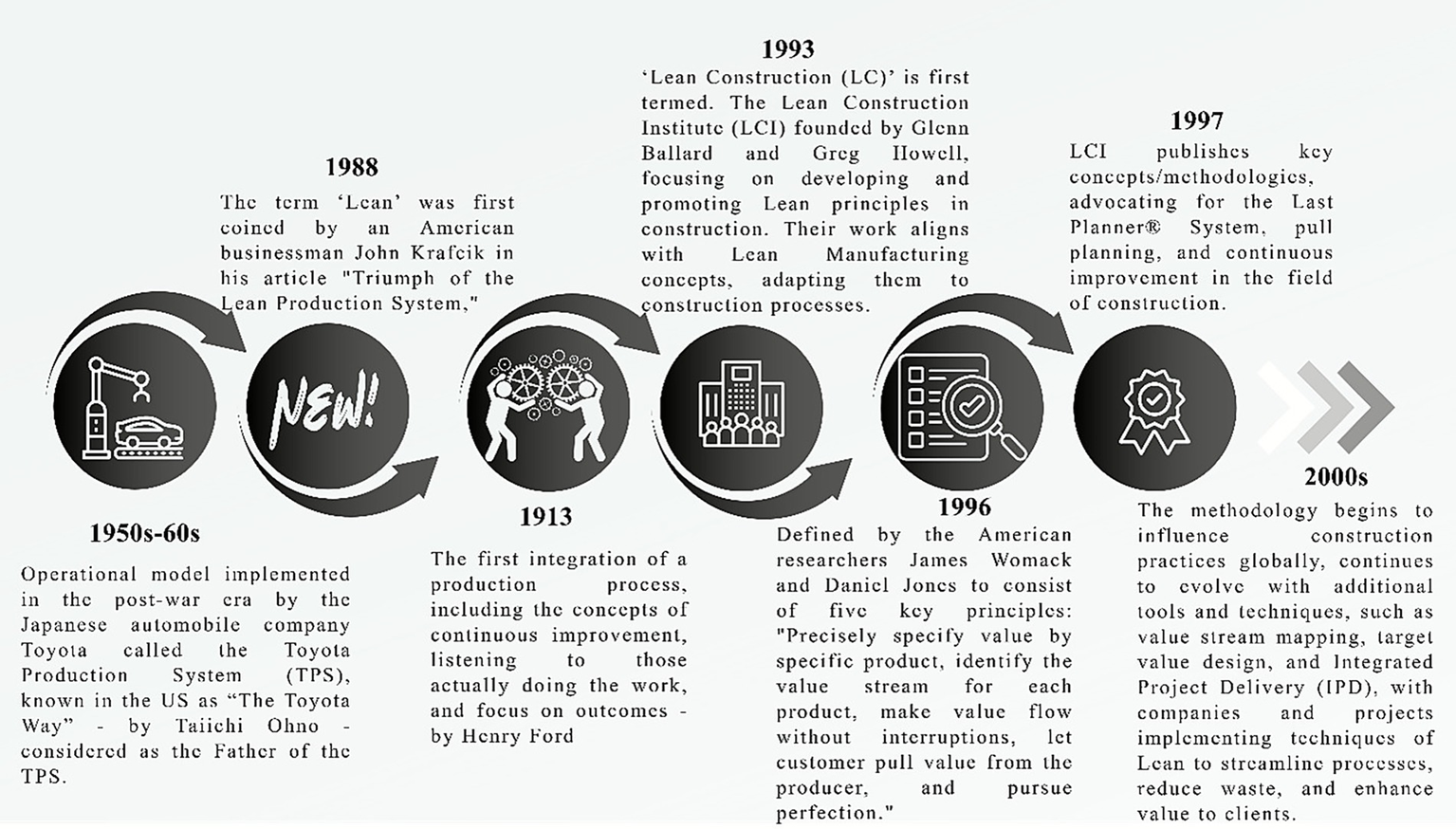

The term “Lean” was originally used in 1988 to refer to the management concept of lean manufacturing, which has its roots in Toyota’s manufacturing System of the 1930s (Howell and Ballard, 1998). With its origins in the lean production system, LC emerged in the early 1990s by approaching the building process from three angles: transformation, flow, and value. Figure 1 gives an overview of the development of the “Lean Construction (LC)” concept over the years.

Figure 1

Development of “Lean Construction (LC)” concept over the years.

The idea of lean thinking and its benefits are realized through the adherence to five fundamental principles of lean production (Eskander and Hafez, 2013):

-

The first principle involves specifying the customer’s value, which requires a thorough understanding and identification of the client’s wants, focusing solely on what the client desires.

-

The second principle is understanding the value stream, which refers to the sequence of actions that, when executed correctly and in the right order, result in the product or service that the client values. Activities are categorized as superfluous and wasteful (which should be eliminated), supporting value-adding activities (which should be minimized as much as possible), and client value-adding (which should be continuously enhanced).

-

The third principle is about improving the flow of work to ensure it is consistent and uninterrupted from one value-adding or supporting activity to the next. This flow significantly accelerates processing, and all efforts should be made to eliminate obstructions and bottlenecks that impede this flow.

-

The fourth principle involves implementing a pull strategy to respond to client demand. Unlike non-lean businesses where work is pushed, resulting in the creation of unneeded outputs, most lean services respond to consumer demand and thus pull work through the system.

-

The fifth and final principle is perfection. Based on the previous four principles, organizations should strive to gain a deeper understanding of the system and provide recommendations for further improvement. An excellent process delivers just the right amount of value to the client. In an ideal process, each stage is value-adding, capable (produces a good outcome every time), available (produces the intended output, not just the desired quality, every time), adequate (does not cause delay), adaptable, and linked by continuous flow. If any of these elements fail, some waste is inevitably generated.

2.1.2 Suitability of lean principles for the construction industry

The primary objective of implementing Lean ideas in the construction industry is to eliminate the significant waste from its materials, processes, and workflows (Aslam et al., 2020). LC employs a suite of tools designed to identify and systematically reduce waste across various domains, including time, inventory, space, labor, equipment, and money. This approach ultimately enhances quality while reducing both production time and costs. Traditionally, sustainable construction efforts have prioritized the building’s operational performance, often overlooking the waste generated during the construction process itself. Nonetheless, integrating Lean thinking into construction practices offers the potential to substantially boost productivity and minimize waste generation. By focusing on adding value and eliminating inefficiencies, Lean promotes continuous and incremental improvements in both processes and outcomes (Waite, 2020).

Moreover, the construction industry encompasses a wide range of core activities, such as regulation, design, planning, production, construction, and maintenance. However, the complexity of these activities—marked by fragmented responsibilities and poorly defined interactions—often obscures a clear understanding of the industry’s structure and the challenges it faces (Hughes et al., 2015). The sector is often characterized by low productivity, cost overruns, delayed schedules, flaws, a bad reputation, insufficient safety precautions, and a scarcity of competent workers (Thomassen and Andreas, 2004). Additionally, the sector exhibits distinct characteristics that set it apart from other industries—the physical nature of its products, on-site project execution on the client’s premises, the uniqueness of most designs, the division of design and construction phases, the sequential nature of construction processes, and the pricing mechanisms used. These factors collectively contribute to the unique challenges and opportunities for improvement within the construction industry.

2.1.3 Application of lean principles in construction

As previously mentioned, LC is the constant process of eliminating waste, meeting or exceeding all client needs, focusing on the full value stream, and striving for perfection in the execution of building projects (Diekmann et al., 2004). To create a lean workplace, construction could implement a set of lean concepts and best practices, including customer focus, culture/people, workplace standardization, waste elimination, and continuous improvement/built-in quality.

Lean concepts have been introduced into the construction industry in various nations, including Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Ecuador, the UK, the USA Peru, and Finland (Fernández-Solís, 2008). However, transitioning to Lean is not a quick or isolated process; it involves a fundamental transformation of the entire organization. Lean is not merely a set of tools or rules—it is a shared philosophy and behavioral system that must be integrated throughout the value chain. Achieving Lean requires a long-term commitment to cultural and operational change.

Given the complex, dynamic, and often unpredictable nature of construction projects, Lean principles must be contextually understood and applied. This necessitates a deep understanding of the construction system as an interdependent network of processes and stakeholders (Diekmann et al., 2004). Lewis (2000) emphasized that while Lean offers significant benefits, its success in implementation heavily depends on the organizational context and prevailing culture.

Accordingly, the tenets of lean thinking in construction can be encapsulated into these key points (Xue et al., 2014). First and foremost, it emphasizes decreasing the shares of non-value-adding activities. This is followed by increasing the value of output by providing systematic configurations that cater to the needs of the customer. It also focuses on decreasing the variability that may occur in the process. Simplifying the different number of steps and parts is another crucial aspect. Furthermore, it aims at increasing the flexibility of output and enhancing the transparency of the process. Concentrating on the completion of the process is another significant point. It also underscores the importance of providing continuous improvements in the process and maintaining a balance between flow and conversion improvement. Lastly, establishing a benchmark is an integral part of these principles. These points collectively form the foundation of lean thinking.

Furthermore, the application of a lean system offers a multitude of benefits to companies (Abo-Zeid and Othman, 2018; Aslam et al., 2024). It enables a significant reduction in waste, cuts production costs, allows for a decrease in manufacturing cycle times while simultaneously reducing labor and maintaining or even increasing throughput. Furthermore, it aids in reducing inventory, which in turn increases customer service levels. The capacity in current facilities can be increased through the implementation of this system. It also plays a crucial role in improving quality and increasing profits. The system’s flexibility is enhanced, allowing it to react swiftly to changes in requirements. It also helps in creating a better strategic focus. Lastly, it improves cash flow by increasing shipping and billing frequencies. Thus, lean production methods provide a comprehensive solution for enhancing operational efficiency and profitability.

2.1.4 Lean tools for prevention and/or reduction of waste

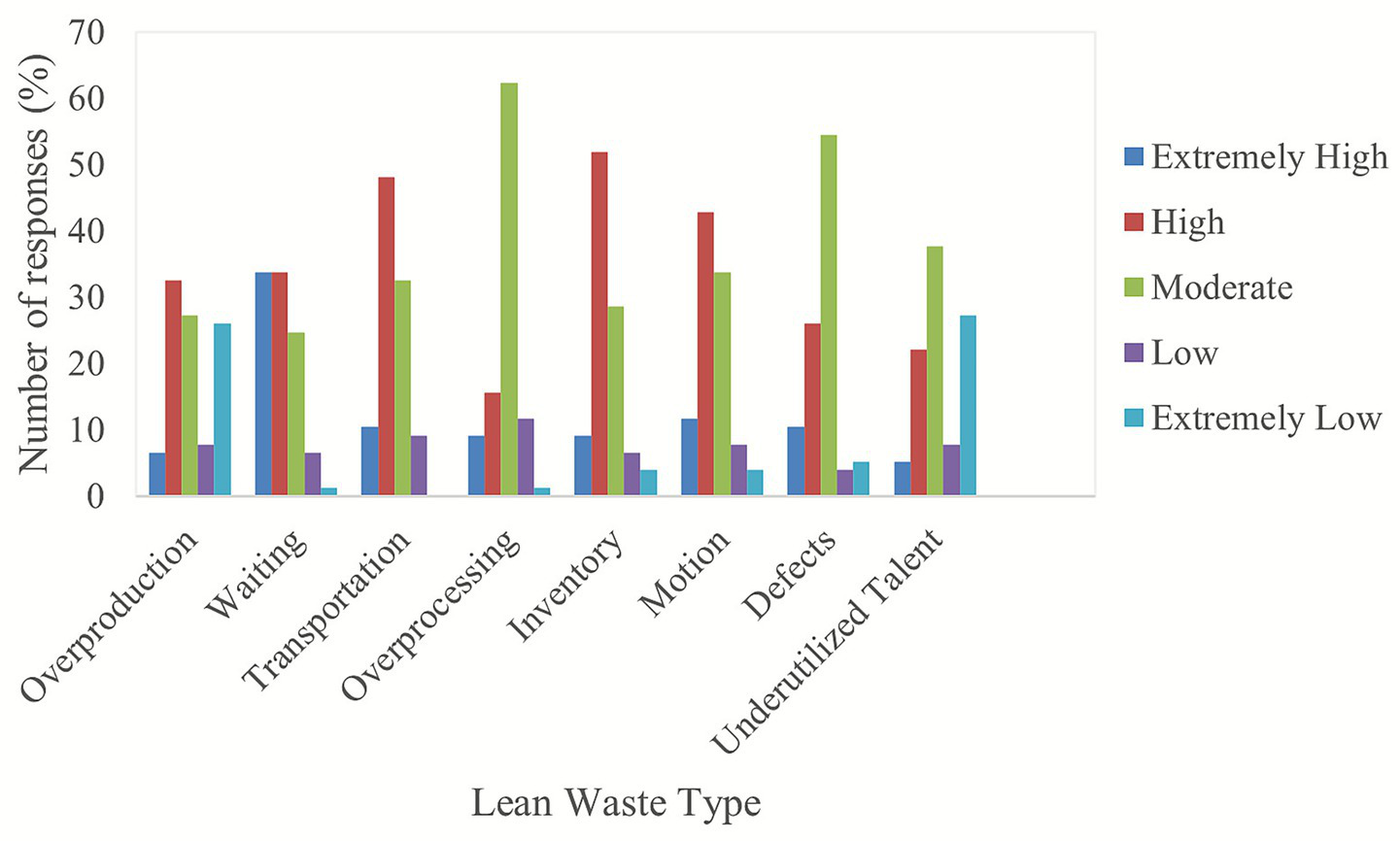

Lean waste refers to any activity or element that adds cost without delivering value to the product or the end customer (Klein et al., 2020). In this context, eight classic categories of waste have been identified: transportation, motion, overproduction, inventory, waiting, over-processing, defects, and underutilized talent. A critical step in progressing toward a more efficient and leaner organizational state is the identification of the most prevalent or most detrimental forms of waste that should be addressed first. Furthermore, for successful Lean implementation, organizations must systematically identify, evaluate, and prioritize these waste types, focusing initially on those that offer the greatest potential for rapid improvement or quick, visible gains in productivity. The eight lean waste types are listed in Table 1 along with their respective description.

Table 1

| Sl. no. | Categories | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Overproduction | Occurs when a product, service, or element is made before it is asked for or required. | Nikakhtar et al., (2015), Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), Maraqa et al. (2023), and Graham (2024) |

| 2. | Waiting | Occurs when workers are waiting for material, machine maintenance, programs, or equipment which results in time loss. | Nikakhtar et al. (2015), Bajjou and Chafi (2019), Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), and Graham (2024) |

| 3. | Transportation | Involves the movement of people, goods, tools, inventory, equipment, or products further than necessary or moved around. | Nikakhtar et al. (2015), Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), Maraqa et al. (2023), and Graham (2024) |

| 4. | Overprocessing | Occurs in situations where more work or steps than necessary are made, or more components than required are included in the process resulting in overly complex systems. | Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), Maraqa et al. (2023), and Graham (2024) |

| 5. | Inventory | Excess of inventory or more than necessary to sustain a steady flow of work tends to increase lead time and needs of space, it also becomes more difficult the identify the problems and communicate. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Nikakhtar et al. (2015), Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), Maraqa et al. (2023), and Graham (2024) |

| 6. | Motion | Includes any unnecessary movement of staff, equipment, or machinery. | Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), Maraqa et al. (2023), and Graham (2024) |

| 7. | Defects | Occurs when final products or services are not fit for use, which incurs direct costs and reworking. Defects indicate clear opportunities to improve procedures. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Nikakhtar et al. (2015), Bajjou and Chafi (2019), Klein et al. (2020), Maraqa et al. (2021), and Graham (2024) |

| 8. | Underutilized talent | Not fully utilizing the skills, knowledge, and capabilities of workers and project teams can lead to inefficiencies and waste. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Bajjou and Chafi (2019), Klein et al. (2020), and Maraqa et al. (2021) |

Lean-type waste and their descriptions.

Several Lean strategies play a vital role in preventing/reducing waste within construction projects (Xue et al., 2014):

-

Process Analysis is a well-known tool for waste reduction in building projects. Each organization has its criteria and standards, which results in a unique type of process and analysis for its initiatives. This tool is essential for defining project objectives clearly and systematically, allowing teams to analyze workflows and pinpoint inefficiencies that contribute to waste.

-

Pull Technique is another effective Lean strategy, which ensures that materials and resources are delivered to the construction site only as needed, based on project demands and timelines. Proper implementation of this technique enhances planning accuracy, reduces excess inventory, and eliminates unnecessary handling—thereby cutting waste and improving overall workflow efficiency.

-

Mistake-proofing techniques is a proactive approach that improves project quality by preventing errors before they occur. It helps minimize rework, reduce delays, and ensure consistency in performance. By limiting the likelihood and consequences of errors in both products and processes, mistake-proofing significantly contributes to waste reduction and productivity gains.

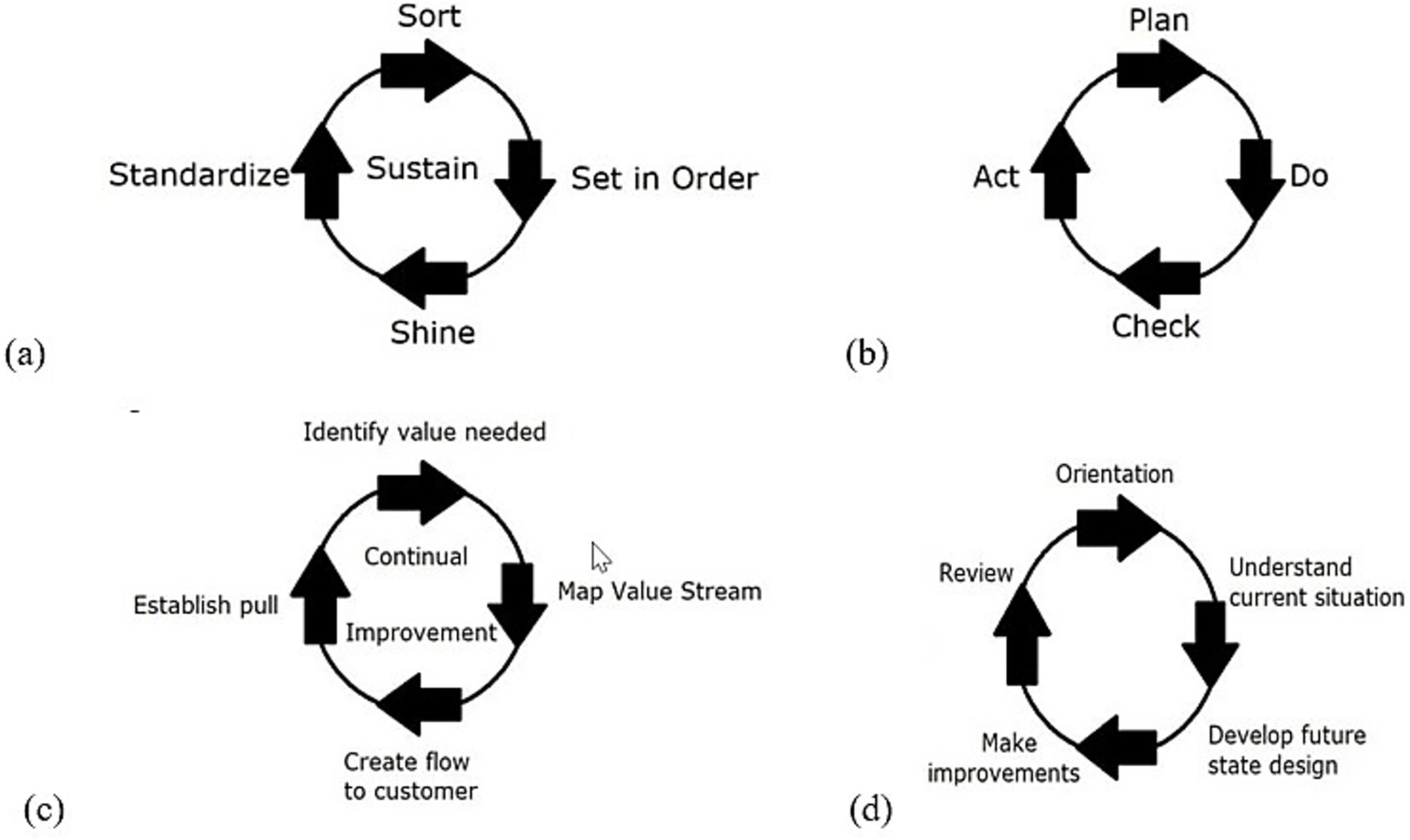

In addition, there are numerous other Lean tools available, each supported by structured guidelines for adoption. Among the most prominent are 5S, Plan Do Check Act (PDCA), Continuous Improvement Cycle (CIP), and Kaizen. These methodologies share common philosophical principles, emphasizing iterative cycles and continuous improvement. These also require a bidirectional flow of information—communicating management goals and decisions while incorporating feedback from frontline personnel. This feedback loop enables teams to align improvements with organizational objectives and fosters a culture of proactive problem-solving. 5S, PDCA, CIP and Kaizen are depicted in Figure 2 (Waite, 2020) to show their underlying philosophies of iterative and cyclical processes seeking continual improvement.

Figure 2

(a) 5S, (b) PDCA, (c) CIP, and (d) Kaizen. Source: Waite (2020).

Ultimately, the value of Lean lies not in the mechanical application of tools, but in embracing its core strategies of waste elimination, transparent communication, and relentless pursuit of improvement.

2.2 Impact of lean construction on construction waste management

A number of literatures point to the fact that LC is highly beneficial in the reduction of waste produced during the life of a construction project, right from its inception to even after its demolition. This section briefly looks through some of these literatures.

To begin with, a case study carried out by Nowotarski et al. (2019) present the benefits of LC toward waste reduction at an office building construction site. Lean Management was implemented for the performance of three different processes in the project and it was concluded that LC approach helped significantly reduce (by about half) the waste generated at the site. Furthermore, Agyekum et al. (2013) examined the application of LC approach for minimizing material wastage in the construction industry in Ghana. Likewise, Abo-Zeid and Othman (2018) investigated the role of Lean approach for reduction of waste in the Egyptian construction industry. A comprehensive understanding of various aspects regarding construction waste, its causes and impacts as well as the challenges and benefits of the implementation of LC in a construction project was highlighted. Additionally, the perception and application of LC for the reduction of construction waste was emphasized upon in this study. Similarly, a study by Waite (2020), lays stress on the use of Lean Management Principles to reduce waste and achieve sustainability in the construction sector. Furthermore, a case study by Berroir et al. (2023) investigated the applicability of LC and Artificial Intelligence (AI) and their potential synergy to aid in on-site construction waste management. In addition, Maraqa et al. (2023) provides strategies for waste reduction in construction projection using lean principles. Also, Karaz and Teixeira (2020) conducted a systematic literature review on construction waste management using LC and Building Information Modeling (BIM), providing useful insights into the relevance of LC for effective construction waste management.

2.3 Lean construction implementation in the UAE’S construction sector

Despite its numerous proven advantages for construction waste management globally, very few studies emphasize on the applicability of LC in the UAE’s construction sector (Small et al., 2017). A study by Bakry (2022) analyzed the suitability of lean tools for effective application in the UAE’s construction industry, by comparing the features of the regional construction market with an assessment of Lean tool capabilities. Al-Aomar (2012) carried out an analysis of LC practices in the construction industry within the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, with the aim of developing a framework for effective application of the approach in the C&D industry. According to the report, only 32% of the organizations surveyed within Abu Dhabi had either used or are currently aware of LC approaches. Warid and Hamani (2023) conducted a case study to investigate the suitability of applying the Last Planner System of LC in UAE construction projects and concluded its successful implementation in the industry. Additionally, Shurrab and Hussain (2018) carried out an empirical investigation to examine the manner in which lean methodology affects the performance of medium and large construction businesses in the UAE. Furthermore, Small et al. (2017) examined the opportunities for integrating LC methods into the construction industry in Dubai by providing insights into specific techniques for overcoming institutional resistance. Additionally, Kanafani (2015) investigated the barriers to the application of Lean principles in the UAE’s construction sector and concluded that lack of commitment from stakeholders overall and from management in particular was the greatest barrier. Another study by Wajahat (2022) also highlighted the barriers toward Lean implementation in the UAE construction industry, offering potential solutions from a Swedish context. Also, Watfa and Sawalha (2021) conducted an empirical study on the critical factors for the successful application of LC in the UAE construction sector.

In conclusion, numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of LC (LC) methodologies in reducing construction waste. However, adoption of these practices within the UAE’s construction sector remains limited, and research on this subject in the region is relatively scarce. Notably, there is a lack of studies that explore stakeholders’ perceptions of LC specifically in the context of construction waste reduction, particularly within the UAE’s building construction sector.

Consequently, this gap underscores the necessity for the present study, which aims to assess the perceptions of professionals in the UAE construction industry regarding the application of Lean Construction. The objective is to gain insight into the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of stakeholders, and to identify the key factors influencing the adoption of LC practices. By doing so, the study seeks to inform the development of effective strategies for the successful implementation of LC in the UAE, thereby enhancing construction waste management with a focused lens on the building construction sector.

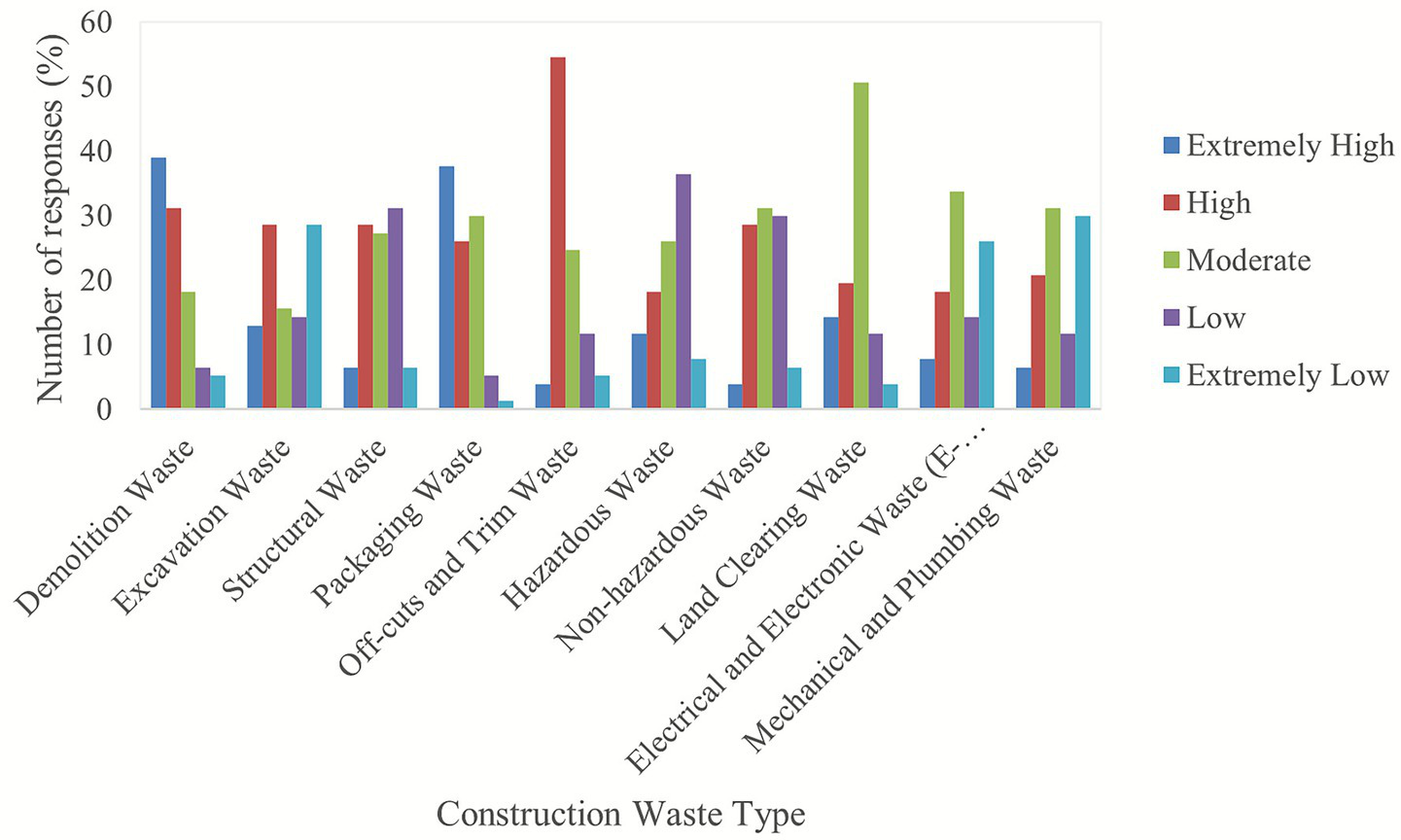

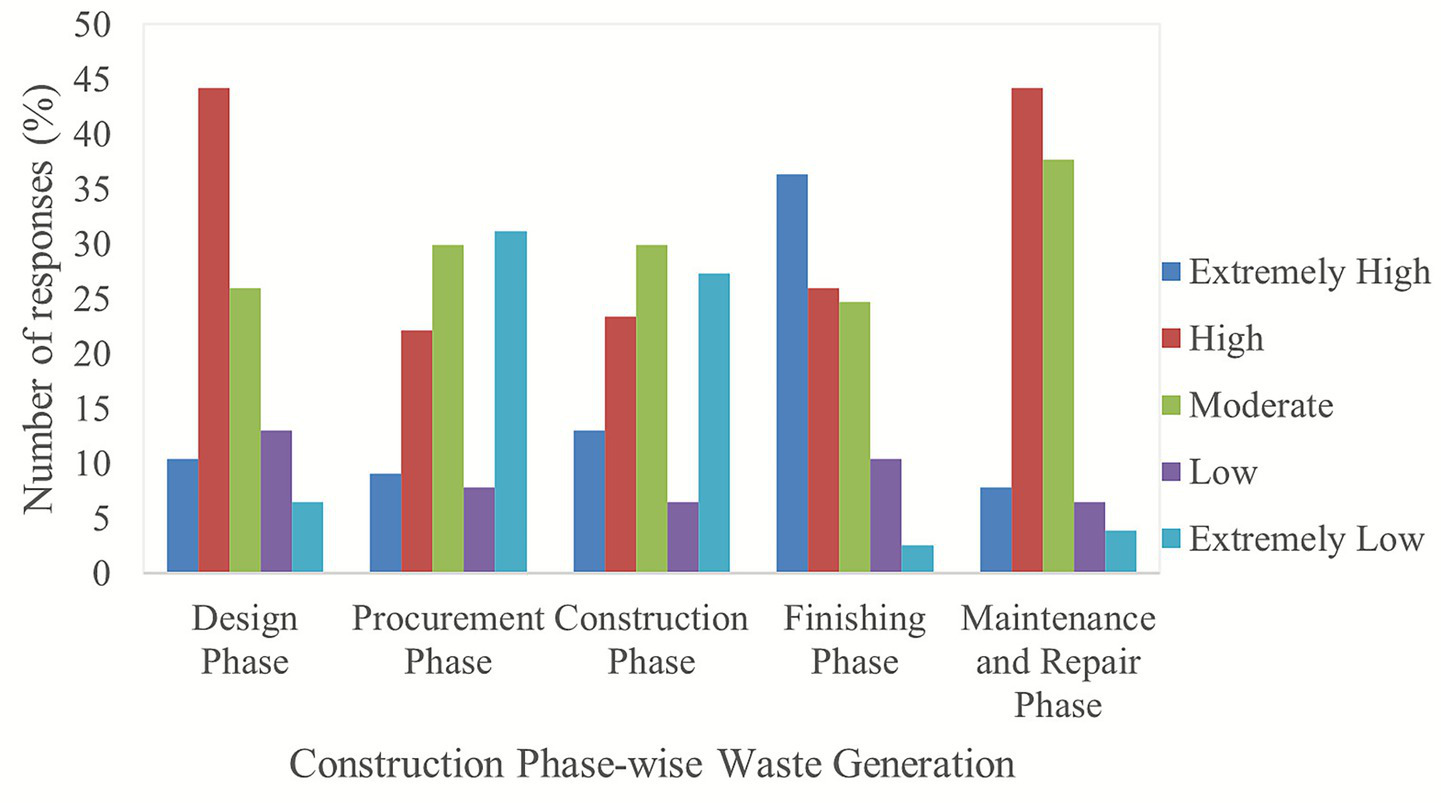

Tables 2, 3 present the foundational insights derived from the literature, detailing the primary types of construction waste and their prevalence across different project phases, respectively. These insights contextualize the relevance of Lean principles in addressing specific waste streams within the construction industry. Table 4 builds upon this by synthesizing a comprehensive list of LC implementation barriers, grouped into thematic constructs identified through content analysis of the literature.

Table 2

| Sl. no. | Construction waste type | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Demolition waste | Generated during the demolition or deconstruction of existing building structures. This includes materials such as concrete, bricks, wood, metals, insulation, and wiring. | Kanafani (2015), Nie et al. (2024), and Dispo (2024) |

| 2 | Excavation waste | Arises from digging, trenching, or earthmoving activities. It comprises soil, rocks, and other materials excavated from the building construction site. | Kanafani (2015), Nie et al. (2024), and Saradara et al. (2024) |

| 3 | Structural waste | Waste resulting from the construction of buildings. This includes excess concrete, steel beams, reinforcement bars (rebar), and other structural elements. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Kanafani (2015), and Nie et al. (2024) |

| 4 | Packaging waste | Packaging materials such as cardboard, plastic wrapping, and wooden pallets used to transport and store building construction materials and equipment. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Kanafani (2015), and Aldeeri and Touqan (2025) |

| 5 | Off-cuts and trim waste | Generated during the cutting, trimming, or shaping of building construction materials such as timber, pipes, and sheet metal. This waste includes small pieces or off-cuts that are discarded. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011) and Kanafani (2015) |

| 6 | Hazardous waste | Materials containing substances that pose a risk to human health or the environment. This includes items such as asbestos-containing materials, lead-based paints, solvents, and chemicals. | Kanafani (2015), Saradara et al. (2024), and Nie et al. (2024) |

| 7 | Non-hazardous waste | General waste produced during building construction activities that does not pose a significant risk to health or the environment. This category may include items such as plastic packaging, paper, cardboard, and food waste. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Kanafani (2015), Hittini and Shibeika (2019), and Saradara et al. (2024) |

| 8 | Land clearing waste | Generated during the clearing of land for construction purposes. It includes vegetation, tree stumps, roots, and other organic matter. | Kanafani (2015) and Saradara et al. (2024) |

| 9 | Electrical and electronic waste (E-Waste) | Discarded electrical and electronic equipment such as wiring, fixtures, appliances, and electronic devices used in construction. | Kanafani (2015), Husin (2019), Kumar and Verma (2024), and Aldeeri and Touqan (2025) |

| 10 | Mechanical and plumbing waste | Waste generated from the installation, maintenance, or replacement of mechanical and plumbing systems. This includes pipes, fittings, valves, and HVAC components. | Kanafani (2015) and Husin (2019) |

Construction wastes generated in a building construction project.

Table 3

| Sl. no. | Construction phases | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Design phase | Design errors, late changes, over-specifications, and lack of coordination leading to material mismatches, rework, and redundant designs. | Meshref et al. (2023) and Purushothaman and Seadon (2024) |

| 2 | Procurement phase | Overstocking, batch ordering, delayed delivery; excessive packaging and material handling due to poor forecasting and supplier coordination. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011) and Purushothaman and Seadon (2024) |

| 3 | Construction phase | Material off-cuts, formwork ejecta, spoil, and debris; general handling losses during core structural operations. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Saradara et al. (2024), Purushothaman and Seadon (2024) |

| 4 | Finishing phase | High volumes of trim waste (tiles, paint, carpentry), packaging from fixtures, surface rework (defects), and oversupply due to last-minute alterations. | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Saradara et al. (2024), and Purushothaman and Seadon (2024) |

| 5 | Maintenance and repair phase | Waste from replacement of parts, reactive repairs, system upgrades, typically redundant or prematurely discarded building components. | Klimenko et al. (2019) |

Construction phase-wise waste types.

Table 4

| Sl. no. | Groups | Barriers | Reference | Description | Associated lean/construction waste type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowledge/ awareness (K) | Lack of knowledge about lean concepts including LC within the public procurement procedure (K1) | Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), Musa et al. (2023), Enshassi et al. (2021a), Ahmed and Wong (2020), Enshassi et al. (2021b), Sayed et al. (2019), and Pedrosa et al. (2023) | Lack of knowledge about lean ideas, such as LC, affects public procurement procedures and leads to ineffective project execution and resource allocation. |

Overprocessing: due to redundant or misaligned procurement steps. Underutilized Talent: because workers are not trained or aware of how to contribute using Lean principles. Structural Waste: poor procurement may lead to wrong materials or specifications, requiring rework or disposal. Packaging Waste: over-ordering or inefficiencies lead to excess packaging. Demolition Waste: ineffective processes can result in redoing work or demolishing parts. |

| 2 | Lack of awareness programs (K2) | Kim and Park (2006), Alarcón et al. (2002), Mehra et al. (2015), and Bashir et al. (2015) | Lack of awareness campaigns prevents stakeholders from learning essential knowledge about LC techniques, which makes it more difficult for the sector to adopt effective procedures and achieve the best project outcomes. |

Underutilized Talent: workers, engineers, and managers lack the training to contribute efficiently. Waiting: due to lack of proactive planning and unfamiliarity with lean methods. Structural Waste: from execution errors due to ignorance of best practices. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: lack of lean planning results in inefficient cutting and material use. |

|

| 3 | Unskilled labor and low level of education of the site foreman (K3) | Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Pedrosa et al. (2023), and Musa et al. (2023) | The widespread presence of poorly trained and insufficiently educated site foremen poses a challenge to the effective application of LC methodologies, hindering the advancement of more sustainable and efficient construction procedures. |

Underutilized Talent: since it involves human resources not being effectively trained or deployed. Defects: errors in execution due to lack of technical skill. Overprocessing: inefficient procedures performed incorrectly or unnecessarily due to lack of understanding. Structural Waste: poor workmanship leads to material rework or structural failure. Mechanical and Plumbing Waste: faulty installation due to lack of technical training. |

|

| 4 | Lack of experiences (K4) | Alarcón et al. (2002) and Bashir et al. (2015) | The industry’s capacity to learn from prior experiences is limited by a lack of direct exposure to successful LC projects, which restricts the general adoption of lean methodology and best practices. |

Defects: mistakes are repeated due to lack of past project learnings. Waiting: inefficiencies occur while figuring out what to do or how to do it. Overprocessing: redundant or non-value-adding steps are repeated due to unfamiliarity with streamlined methods. Demolition Waste: corrections and reworks required due to misjudgment or lack of technical insight. Structural Waste: overdesign or mis-installation from inexperience. Non-hazardous Waste: materials wasted due to trial-and-error handling. |

|

| 5 | Attitude (A) | Selfishness among professionals (A1) | Mossman (2009) | Selfishness among professionals hampers collaboration and inhibits the collective adoption of LC principles. |

Underutilized Talent: collaboration failure prevents pooling of skills and ideas. Waiting: project delays occur when parties fail to share information or cooperate. Defects: lack of communication and teamwork increases coordination errors. Structural Waste: poor coordination between design and site execution causes rework. Demolition Waste: miscommunication can lead to incorrect construction that must be redone. Non-hazardous Waste: material overuse or disposal from poor planning and lack of collaboration. |

| 6 | Stick to the old ways and refuse to use new ideas (A2) | Bayhan et al. (2019) and Al Balkhy et al. (2021) | Resistance to new ideas and a preference for traditional methods hinder the integration of LC practices, preventing the industry from evolving and optimizing its processes to meet modern challenges. |

Waiting: delays occur when outdated methods slow adoption of faster, more efficient approaches. Overprocessing: reliance on redundant or inefficient traditional steps. Underutilized Talent: innovation and initiative from workers are suppressed when traditional practices dominate. Waiting: resistance to change causes delays in adopting improved workflows or new technologies. Overprocessing: outdated methods often involve redundant steps, excessive paperwork, and inefficient processes. Structural Waste: continued use of outdated techniques can result in inefficiencies and rework. Non-hazardous Waste: old processes yield excess packaging, paper, or unused materials. |

|

| 7 | Labor considers LC too complex (A3) | Musa et al. (2023), Bayhan et al. (2019), Metlej (2021), Sholanke et al. (2019), Al Balkhy et al. (2021), and Bajjou and Chafi (2018) | Labor frequently view LC as too difficult, which makes them unwilling to adopt it and prevents them from realizing how beneficial it is for enhancing workflow and eliminating waste. |

Underutilized Talent: workers disengage or avoid Lean methods because they feel incapable of applying them, leading to lost potential and inefficiency. Waiting: hesitation and slow decision-making occur as laborers delay actions due to uncertainty about Lean practices. Defects: misapplications or misunderstandings of Lean procedures lead to mistakes in execution and rework. Structural Waste: errors in construction or assembly due to improper application of Lean methods. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: inaccurate measurements and poor understanding of processes increase off-cut generation. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient handling of materials and processes leads to excessive discard of general waste. |

|

| 8 | Fear of unfamiliar activities (A4) | Mossman (2009), Alarcón et al. (2002), Bashir (2013), Bashir et al. (2015), and Sarhan and Fox (2012) | Fear of unfamiliar activities creates a barrier to embracing LC methodologies, impeding progress toward more efficient and sustainable construction practices. |

Waiting: progress slows as workers hesitate to engage in new or unfamiliar Lean practices. Underutilized Talent: potential contributions from skilled workers are lost when fear prevents them from experimenting or innovating. Overprocessing: reliance on traditional, repetitive methods instead of simplified Lean processes increases unnecessary steps. Defects: avoidance of new, more accurate processes leads to reliance on outdated, error-prone methods. Structural Waste: reluctance to adopt efficient methods leads to continued use of error-prone construction techniques. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient or redundant material usage arises from sticking to old, familiar processes. Packaging Waste: hesitation to implement new material-handling systems results in excess packaging and material movement. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: avoidance of prefabrication or precision cutting methods, leading to material surplus and scrap. |

|

| 9 | Lack of self-criticism (A5) | Alarcón et al. (2002) | A lack of self-criticism prevents professionals from identifying and addressing inefficiencies within their processes, hindering the continuous improvement necessary for successful implementation of LC principles. |

Defects: recurring errors go uncorrected because processes are not evaluated critically. Overprocessing: unnecessary or inefficient steps continue unchecked due to the absence of reflection and improvement. Underutilized Talent: failure to encourage feedback prevents workers from contributing ideas for improvement. Structural Waste: repeated mistakes in design or execution create rework and material loss. Demolition Waste: unaddressed process errors lead to the need for demolition and rebuilding. Non-hazardous Waste: materials are wasted when inefficiencies are ignored rather than resolved. |

|

| 10 | Inability to change the organizational culture (A6) | Kim and Park (2006), Sandeep and Panwar (2016), Salem et al. (2005), Zhou (2016), Mossman (2009), Mehra et al. (2015), Attri et al. (2017), and Sarhan and Fox (2012) | Inability to change the organizational culture to one that values innovation and efficiency obstructs the widespread adoption of LC, limiting the industry’s ability to adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing environment. |

Underutilized Talent: employees’ ideas and creativity are ignored due to a rigid culture resistant to innovation. Waiting: decision-making and process improvements are delayed because the organization resists change. Overprocessing: outdated procedures are maintained unnecessarily, adding non-value-creating steps. Structural Waste: rigid management structures hinder adaptive responses, resulting in design or build errors. Non-hazardous Waste: outdated practices result in continued material wastage and poor site management. Demolition Waste: reluctance to adopt continuous improvement increases the risk of rework and reconstruction. |

|

| 11 | Management (M) | Inadequate pre-planning (M1) | Ahmed et al. (2021) and Moyo and Chigara (2021) | Lack of thorough preparation and foresight in the initial stages of a construction project, including insufficient consideration of LC principles. This barrier impedes the effective implementation of lean methodologies, leading to inefficiencies, delays, and increased costs during project execution. |

Waiting: project activities are delayed due to poor scheduling and lack of foresight in planning. Overproduction: materials and work are initiated prematurely without proper coordination. Defects: design and construction errors arise because critical details were not addressed during planning. Transportation: poor logistics planning causes unnecessary movement of materials or equipment. Structural Waste: insufficient planning and poor coordination between design and execution causes incorrect installations and material wastage during construction. Excavation Waste: poor pre-planning and site preparation leads to unnecessary earthwork and material handling. Non-hazardous Waste: poor resource coordination results in surplus materials and packaging waste. Packaging Waste: Disorganized logistics and delivery lead to excessive packaging disposal. |

| 12 | Lack of employee training and continuous improvement in lean construction (M2) | Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Sayed et al. (2019), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Ahmed et al. (2021), and Sholanke et al. (2019) | Inadequate employee training about LC principles and the absence of efforts to make ongoing enhancements hinder the industry’s capacity to maximize project completion and improve efficiency. |

Underutilized Talent: employees are unable to contribute effectively because they lack Lean knowledge and skill development. Defects: mistakes occur due to insufficient understanding of best practices through Lean processes and poor execution. Overprocessing: inefficient or redundant activities persist because workers are not trained to identify wasteful steps. Waiting: Poorly trained staff take longer to make decisions or complete tasks, causing delays. Structural Waste: poor workmanship and repeated errors increase rework and material usage. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: inefficient handling of materials results in excessive trimming and waste generation. Non-hazardous Waste: limited training in sustainable practices leads to poor waste segregation and material management. |

|

| 13 | Lack of information sharing (M3) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), Alarcón et al. (2002), and Bashir et al. (2015) | This refers to ineffective channels for exchanging information and aligning efforts, hindering the seamless integration of LC principles and impeding project efficiency. |

Waiting: delays occur as teams wait for necessary information or approvals from other departments. Defects: miscommunication or missing data leads to design errors, rework, and inconsistencies. Overprocessing: duplicate work arises when information is not shared efficiently among stakeholders. Transportation: unnecessary transfer of information or materials due to poor coordination systems. Structural Waste: incorrect or incomplete information results in rework and inefficient material use. Packaging Waste: lack of coordination in material handling increases unnecessary packaging and transport. Demolition Waste: poor information flow can lead to construction errors requiring partial demolition and rebuilding. Mechanical and Plumbing Waste: Mis-coordination between MEP teams and other disciplines causes fitting errors. |

|

| 14 | Poor communication between project parties (M4) | Mehra et al. (2015), Attri et al. (2017), and Small et al. (2017) | This denotes a lack of effective information exchange and collaboration among stakeholders involved in a construction project, hindering the successful implementation of LC principles. This barrier leads to misunderstandings, delays, and conflicts, impeding the optimization of processes and the attainment of project goals. |

Waiting: tasks are delayed because critical information, approvals and instructions are not communicated promptly. Defects: misinterpretation of plans or instructions between design and site teams leads to construction errors and rework. Overprocessing: duplicate efforts, excessive documentation and unnecessary corrections occur due to misaligned communication. Transportation: Repeated physical or digital transfer of drawings, materials, or requests due to fragmented communication. Structural Waste: errors caused by poor coordination between designers, contractors, and site staff result in rework and excess material use. Demolition Waste: sections of work may need to be demolished and rebuilt due to misunderstanding of requirements or drawings. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient communication causes improper use, storage or disposal of materials on-site. Mechanical and Plumbing Waste: Coordination lapses between trades lead to misplaced or conflicting installations. |

|

| 15 | Lack of supply chain integration (M5) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), and Al Balkhy et al. (2021) | The absence of seamless collaboration and coordination among various suppliers and subcontractors, inhibiting the smooth implementation of LC practices and resulting in inefficiencies within the project delivery process. |

Waiting: work halts while materials, approvals, or subcontractor inputs are delayed. Transportation: excessive or unnecessary movement of materials occurs because of unaligned logistics. Inventory: overstocking or shortages result from a lack of synchronized supply chain planning. Packaging Waste: excess packaging from fragmented deliveries and multiple suppliers. Structural Waste: delays or mismatched deliveries cause rework and material inefficiencies. Non-hazardous Waste: over-ordering, improper storage or handling of materials results in general site waste accumulation. |

|

| 16 | Slow decision-making as a result of complex organization hierarchy (M6) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Musa et al. (2023), Al Balkhy et al. (2021) | The delays in responding to project needs due to bureaucratic layers, hindering the agile implementation of LC principles and impeding overall project efficiency. |

Waiting: prolonged approval processes delay project progress and workflow efficiency. Overprocessing: redundant layers of authorization add unnecessary administrative steps. Underutilized Talent: decision-making power is concentrated, limiting initiative and problem-solving among lower-level staff. Structural Waste: delays in approvals lead to scheduling conflicts and inefficient resource use. Non-hazardous Waste: stalled activities cause material degradation and accumulation of general waste on-site. |

|

| 17 | Contractors and specialists rarely involved in the planning and design phase (M7) | Ahmed et al. (2021) and Moyo and Chigara (2021) | This signifies a missed opportunity for early collaboration and input, leading to suboptimal project outcomes and hindering the effective implementation of LC principles. |

Defects: design errors occur because practical, on-site expertise is not considered early. Overprocessing: additional rework and redesign efforts arise due to lack of early coordination. Waiting: delays in later phases arise due to design conflicts discovered too late. Structural Waste: design inconsistencies lead to rework and material wastage during construction. Demolition Waste: parts of the structure may need to be removed and redone due to impractical design details. Packaging Waste: un-coordinated deliveries and material handling due to poor upfront planning. Non-Hazardous Waste: extra materials consumed during late-stage corrections or modifications. |

|

| 18 | Lengthy approval procedure from top management (M8) | Small et al. (2017) | This represent administrative delays that prevent LC techniques from being quickly implemented, reducing project efficiency and responsiveness to changing requirements. |

Waiting: extended approval times delay project execution and disrupt workflow continuity. Overprocessing: multiple unnecessary approval steps add bureaucracy and slow progress. Underutilized Talent: lower-level staff cannot act independently despite being capable. Structural Waste: delayed approvals affect scheduling and material readiness, leading to inefficiencies. Non-hazardous Waste: idle time results in material spoilage and accumulation of site waste. |

|

| 19 | Lack of support from top management (M9) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), and Bayhan et al. (2019) | This indicates a lack of commitment and resources essential for driving the adoption of LC principles throughout the organization. |

Underutilized Talent: employees are not empowered or motivated to apply Lean principles effectively. Waiting: decision-making and resource allocation are delayed due to lack of managerial involvement. Overprocessing: inefficient or outdated processes persist because leadership does not champion Lean improvements. Structural Waste: limited oversight, lack of resource support and commitment lead to poor quality control and material rework. Non-hazardous Waste: general inefficiencies, unused materials, and administrative waste from lack of strategic guidance. Demolition Waste: lack of strategic direction causes misaligned objectives, requiring correction or reconstruction. |

|

| 20 | Unclear project definition and outcomes (M10) | Attri et al. (2017) and Bashir et al. (2015) | A lack of clarity in project objectives, which hampers the application of LC methodologies requiring clear goals for optimization and continuous improvement. |

Defects: vague project objectives lead to design errors, rework, and misaligned deliverables. Overprocessing: unnecessary work and redundant documentation occur due to unclear scope. Waiting: teams pause for clarification or additional instructions, delaying workflow. Overproduction: work is done ahead of need or to incorrect specifications. Structural Waste: miscommunication and poor project scoping lead to rework and excess material use and wastage. Demolition Waste: unclear design or scope changes result in partial demolition and reconstruction. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient planning and misalignment create surplus or discarded materials. |

|

| 21 | Centralization of decision under single authority (M11) | Moyo and Chigara (2021), Musa et al. (2023) and Al Balkhy et al. (2021) | Refers to a concentration of power that inhibits decentralized problem-solving and collaborative decision-making, hindering the agile and adaptive nature of LC practices. |

Waiting: project teams experience delays while awaiting approvals or instructions from a single authority. Underutilized Talent: employees and middle managers are discouraged from making independent decisions or suggesting improvements. Overprocessing: repetitive administrative reviews occur due to concentration of decision-making power. Structural Waste: delayed decisions disrupt work sequencing and resource allocation, leading to inefficiencies. Non-hazardous Waste: prolonged waiting periods cause material degradation and general site waste. Packaging Waste: Inefficient procurement cycles and material handling due to rigid hierarchy. |

|

| 22 | Lack of motivation for the employees to learn about lean construction (M12) | Moyo and Chigara (2021), Ahmed et al. (2021), Al Balkhy et al. (2021), and Sholanke et al. (2019) | Signifies a reluctance to embrace new methodologies, impeding the adoption of lean principles essential for enhancing project efficiency and effectiveness. |

Underutilized Talent: workers do not develop or apply skills that could enhance productivity and reduce waste. Defects: low engagement and poor understanding lead to mistakes and inconsistent quality. Waiting: lack of motivation slows initiative and responsiveness, delaying workflow improvement. Structural Waste: errors and inefficiencies persist due to limited workforce engagement and care. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: inattentive material handling and poor work habits increase waste during fabrication. Non-hazardous Waste: disinterested employees fail to adhere to waste management practices, leading to avoidable material loss. |

|

| 23 | Poor leadership (M13) | Mossman (2009), Mehra et al. (2015), Attri et al. (2017), and Bashir et al. (2015) | Denotes a deficiency in guiding and inspiring teams, hindering the successful implementation of LC principles that require strong direction and support from management |

Underutilized Talent: lack of direction and support prevents employees from contributing their full potential. Waiting: indecisive or ineffective leadership causes delays in task allocation and project progression. Defects: unclear guidance and inconsistent supervision lead to mistakes and quality issues. Overprocessing: lack of clear priorities causes redundant or misdirected efforts. Structural Waste: poor supervision and decision-making cause errors and rework during construction. Demolition Waste: inadequate oversight leads to improper execution, resulting in sections needing removal or rebuilding. Non-hazardous Waste: disorganized site management results in unnecessary material loss and poor waste segregation. |

|

| 24 | Lack of transparency (M14) | Alarcón et al. (2002) | Deficit in openness and accessibility of information, impeding the effective application of LC principles that rely on shared visibility and accountability throughout the project lifecycle. |

Defects: hidden information and poor visibility lead to design or execution errors that require correction. Overprocessing: redundant checks and reporting arise to compensate for missing transparency. Waiting: delayed communication of project updates causes idle time and disrupted scheduling. Structural Waste: lack of clarity on specifications or progress leads to rework and inefficient use of materials. Non-hazardous Waste: incomplete information about materials or processes leads to poor site waste handling and segregation. |

|

| 25 | Poor communication among participants of the production process (managers, foremen, administrators, etc.) (M15) | Bashir et al. (2015), Bashir (2013), and Salem et al. (2005) | Breakdown in coordination and information sharing that prevents LC principles—which depend on smooth cooperation and mutual understanding—from being applied effectively. |

Waiting: work progress is delayed as teams await information or clarification from others. Defects: errors occur due to misunderstandings or inconsistent instructions between project participants. Overprocessing: repeated corrections and duplicated efforts result from unclear communication channels. Transportation: inefficient communication leads to unnecessary movement of materials, tools, or workers. Structural Waste: poor coordination causes design and construction mismatches leading to rework. Demolition Waste: misaligned instructions and execution errors require partial demolition and reconstruction. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient coordination leads to unnecessary material use and increased waste generation. Mechanical and Plumbing Waste: coordination gaps between trades lead to damaged or misplaced MEP components. |

|

| 26 | Lack of long-term commitments to innovation and change within the company (M16) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Prabaharan and Shanmugapriya (2023), Enshassi et al. (2021a), Ahmed and Wong (2020), Mossman (2009), Bashir (2013), Bashir et al. (2015), and Small et al. (2017) | Indicates a reluctance to invest in continuous improvement initiatives, impeding the sustained adoption and integration of LC practices essential for long-term success. |

Underutilized Talent: employees are discouraged from pursuing continuous improvement or suggesting innovative solutions. Overprocessing: outdated processes are maintained without evaluation or optimization. Defects: lack of sustained learning leads to recurring mistakes and process degradation. Waiting: progress slows as the organization hesitates to invest in or adopt new Lean practices. Structural Waste: failure to innovate leads to repetitive errors and material inefficiencies over time. Non-hazardous Waste: obsolete methods and lack of process improvement result in persistent material wastage. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: lack of investment in precision technologies or prefabrication increases material excess. Demolition Waste: lack of adaptation to modern standards or sustainable methods causes rework and reconstruction needs. |

|

| 27 | Lack of teamwork (M17) | Bashir et al. (2015), Bashir (2013), and Salem et al. (2005) | Inadequate teamwork and responsibility sharing among project participants, obstructing the successful application of LC concepts, which place value on cooperation and group problem-solving. |

Underutilized Talent: individual capabilities are not effectively combined, leading to lost potential and inefficiency. Waiting: tasks are delayed as teams fail to coordinate or wait on others to complete dependent activities. Overprocessing: teams duplicate efforts or engage in redundant activities due to poor coordination. Defects: poor collaboration leads to inconsistent work quality and errors that require rework. Structural Waste: lack of coordination results in mistakes during construction, leading to material rework. Demolition Waste: misaligned efforts between trades or departments lead to errors requiring partial demolition. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient teamwork leads to duplicated material use and general on-site waste accumulation. Mechanical and Plumbing Waste: coordination gaps between trades cause misalignment or damage. |

|

| 28 | Government (G) | Lack of supportive government laws and regulations that helps to implement lean construction (G1) | Al-Hajj and Hamani (2011), Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Enshassi et al. (2021b) and Ahmed and Wong (2020) | Denotes a deficiency in legal frameworks and incentives, hindering the widespread adoption of lean methodologies in the construction industry. |

Waiting: Bureaucratic processes and unclear legal frameworks cause project delays. Overprocessing: additional administrative steps are required to comply with outdated or irrelevant regulations. Defects: inconsistent or poorly defined standards lead to confusion and implementation errors. Underutilized Talent: industry professionals cannot fully apply Lean methods due to regulatory constraints. Structural Waste: misalignment between regulatory requirements and modern practices leads to inefficiencies and rework. Demolition Waste: delayed or conflicting approvals cause rework or redesign after construction begins. Non-hazardous Waste: lack of waste management regulations contributes to poor segregation and disposal practices on-site. |

| 29 | Inconsistent governmental policies (not constant and steady) over time (G2) | Moyo and Chigara (2021), Pedrosa et al. (2023), and Enshassi et al. (2021a) | Fluctuating regulations and guidelines, which disrupt continuity and stability, impeding the consistent implementation of LC practices in the industry. |

Waiting: project implementation is delayed as companies adjust to frequent policy changes. Overprocessing: repeated administrative adjustments are needed to comply with shifting government requirements. Defects: projects built under outdated or misunderstood regulations must be redone or corrected. Overprocessing: Additional documentation or compliance work required due to policy changes. Structural Waste: redesign or reconstruction of project elements due to compliance revisions. Non-hazardous Waste: inconsistent waste management policies result in poor recycling and disposal practices. |

|

| 30 | Government bureaucracy and instability (G3) | Small et al. (2017) | This indicates administrative hurdles and uncertainty in policies, obstructing the streamlined adoption of LC practices within the construction sector. |

Waiting: long approval cycles and administrative delays stall project flow. Overprocessing: excessive documentation and administrative steps add unnecessary effort. Transportation: repeated movement of documents and people across departments for approvals. Structural Waste: inefficient inspection and permitting processes delay work and increase rework risk. Non-hazardous Waste: idle materials deteriorate while awaiting administrative clearance. |

|

| 31 | Inflation in material prices due to unsafe market conditions for construction (G4) | Enshassi et al. (2021b) and Ahmed and Wong (2020) | This refers to volatile economic environments that disrupt cost predictability, impeding the efficient implementation of LC practices reliant on stable input costs. |

Waiting: delays occur while sourcing affordable materials or renegotiating prices. Inventory: firms and projects overstock or understock materials in response to unpredictable pricing. Overproduction: materials may be purchased in excess to hedge against future price increases, leading to inefficiencies. Structural Waste: fluctuating prices cause changes in material selection and substitutions that result in inefficiencies. Packaging Waste: bulk buying during inflation periods increases packaging materials and handling waste. Non-hazardous Waste: over-purchasing or poor storage due to panic buying leads to material degradation and waste. |

|

| 32 | Corruption due to bribery, extortion and fraud (G5) | Attri et al. (2017) | This signifies unethical practices that undermine fair competition and transparency, hindering the effective implementation of LC principles and impeding project efficiency. |

Overprocessing: additional, redundant steps (paperwork, payments, or approvals) arise to satisfy corrupt practices. Defects: poor-quality materials or work from non-merit-based contractor selection. Waiting: delays due to favoritism, selective approvals, and administrative manipulation. Structural Waste: substandard materials and compromised supervision lead to structural inefficiencies and rework. Demolition Waste: corruption-induced poor-quality work results in the need for removal and reconstruction. Non-hazardous Waste: misuse of materials and over-ordering to conceal inflated procurement costs. |

|

| 33 | Financial (F) | Lack of funding to start the implementation of lean construction in the company (F1) | Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), Sholanke et al. (2019), Enshassi et al. (2021b), and Ahmed and Wong (2020) | This denotes a shortage of financial resources, hindering the initial investment necessary for adopting lean methodologies and initiating process improvements. |

Waiting: limited financial resources delay the initiation of Lean programs and procurement of necessary tools. Inventory: insufficient funding disrupts material flow, causing shortages or overstocking at inappropriate times leading to unwanted waste. Underutilized Talent: employees cannot receive proper training or use Lean tools effectively due to budget constraints. Structural Waste: poor funding limits quality control and supervision, resulting in rework and inefficiencies. Non-hazardous Waste: resource mismanagement due to funding gaps causes surplus materials and waste accumulation. |

| 34 | Poor salaries of professionals (F2) | Bashir (2013), Bashir et al. (2015), and Sandeep and Panwar (2016) | It represents insufficient pay, which could lower productivity and make it more difficult to hire and retain the qualified workers needed to successfully apply LC techniques. |

Underutilized Talent: low compensation reduces motivation and engagement, preventing employees from performing to their full potential. Defects: lack of incentive and morale leads to careless work and quality issues. Waiting: reduced workforce motivation slows productivity and responsiveness. Structural Waste: poor performance and reduced oversight lead to construction errors and rework. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: low worker motivation results in careless material cutting and handling. Non-hazardous Waste: demotivated staff fail to follow waste management protocols, increasing general waste on-site. |

|

| 35 | Unsteady price of commodities (F3) | Bashir (2013) and Bashir et al. (2015) | Refers to fluctuating costs of materials, hindering cost predictability and making it challenging to implement LC practices that rely on stable input prices. |

Waiting: procurement activities are delayed as firms wait for favorable price conditions. Inventory: companies overstock materials during low-price periods, leading to storage inefficiencies. Overproduction: excess ordering occurs to mitigate future price increases, causing imbalance in supply. Structural Waste: fluctuating prices lead to material substitution and inconsistencies in quality, causing rework. Packaging Waste: repeated orders and deliveries increase packaging materials and logistics waste. Non-hazardous Waste: materials purchased in excess may expire, degrade, or be discarded due to poor storage and planning. |

|

| 36 | Low tender prices (F4) | Small et al. (2017) | This show underbidding in the procurement process, which might delay the successful use of LC techniques that prioritize value delivery over cost-cutting initiatives and compromise quality. |

Defects: cost-cutting during low tenders leads to poor-quality materials and workmanship. Overprocessing: extra rework and paperwork to justify cost changes or recover losses. Underutilized Talent: qualified professionals are replaced with less experienced labor to reduce costs, limiting efficiency. Waiting: delays caused by resource shortages or budget constraints. Structural Waste: compromised quality and poor workmanship lead to rework and excess material use. Demolition Waste: substandard construction resulting from low-cost strategies may require removal and rebuilding. Non-hazardous Waste: the use of cheap, low-quality materials increases waste generation and disposal needs. |

|

| 37 | Material requirement and equipments (R) | Scarcity of materials suitable for LC implementation (R1) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), and Sayed et al. (2019) | This refers to a lack of availability of specific materials tailored to LC methodologies, hindering the seamless integration of lean principles into construction projects. |

Inventory: material shortages cause imbalance in supply, leading to overstocking of alternatives or waiting for deliveries. Waiting: project progress is delayed due to unavailability of Lean-compliant materials. Transportation: sourcing materials from distant suppliers increases unnecessary movement and logistical inefficiencies. Overprocessing: rework or modification of unsuitable materials to meet design requirements. Structural Waste: unsuitable or substitute materials lead to poor performance and rework. Non-hazardous Waste: replacement materials may not be optimized for Lean use, creating excess waste on-site. |

| 38 | Inadequate equipment to implement LC methods (R2) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), and Sayed et al. (2019) | This denotes a shortage of specialized tools and machinery required for efficient execution of LC practices, impeding the adoption and effectiveness of lean methodologies on construction sites. |

Waiting: project activities are delayed while teams share or wait for limited equipment. Overprocessing: additional manual work or alternative steps are performed due to lack of proper tools. Motion: excessive physical movement occurs as workers adapt processes to compensate for missing equipment. Structural Waste: inefficiencies and errors occur when manual methods replace appropriate mechanized processes. Non-hazardous Waste: inefficient equipment use increases material handling and site waste accumulation. |

|

| 39 | Limited use of off-site construction techniques and prefabrication (R3) | Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Pedrosa et al. (2023), and Metlej (2021) | Signifies a missed opportunity to streamline processes and minimize waste, hindering the full realization of LC principles aimed at maximizing efficiency and productivity. |

Overprocessing: traditional on-site methods require more steps and labor compared to prefabrication. Transportation: inefficient movement of materials and components occurs due to fragmented on-site processes. Motion: limited prefabricated technique-usage leads to more movement of personnel on-site to produce the same components. Defects: lack of precision from on-site fabrication increases the likelihood of errors and rework. Structural Waste: manual on-site fabrication results in dimensional inaccuracies and excess material use. Off-cuts and Trim Waste: inefficient on-site cutting and assembly increase material waste. Non-hazardous Waste: traditional methods produce general debris, packaging, and miscellaneous material waste. |

|

| 40 | Technical (T) | Poor performance measurements strategies (T1) | Small et al. (2017), Bashir et al. (2015), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Sayed et al. (2019), and Bashir (2013) | Refers to inadequate methods for assessing project progress and outcomes, hindering the effective implementation of LC principles reliant on data-driven decision-making and continuous improvement. |

Defects: errors and inefficiencies go undetected due to lack of proper monitoring and evaluation. Overprocessing: excessive or redundant reporting compensates for unclear metrics. Waiting: delayed decision-making results from absence of real-time performance feedback. Underutilized Talent: workers’ feedback and ideas are ignored in the absence of performance monitoring. Structural Waste: rework from undetected quality issues or performance deviations. Non-hazardous Waste: poor monitoring of material usage leads to excess consumption and waste generation. Demolition Waste: unmeasured performance deviations can cause major errors requiring partial reconstruction. |

| 41 | Lack of software advancement that helps in implementing LC (T2) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Bayhan et al. (2019), Sholanke et al. (2019), and Musa et al. (2023) | Indicates a deficiency in technology tools tailored for LC methodologies, impeding the efficient adoption and integration of lean practices into project management processes. |

Waiting: project progress is delayed due to slow information processing and manual coordination. Overprocessing: repetitive manual data entry and documentation replace automated workflows. Transportation and Motion: excess movement of documents, drawings, and personnel for communication. Defects: lack of digital integration leads to inaccurate data, poor coordination, and errors. Structural Waste: coordination gaps from manual systems result in design and construction inconsistencies. Demolition Waste: design or planning errors unnoticed until construction stage. Non-hazardous Waste: absence of digital monitoring leads to uncontrolled material usage and waste. |

|

| 42 | Lack of agreed implementation methodology (T3) | Small et al. (2017) | Refers to the absence of a standardized approach for applying LC principles, resulting in inconsistency and hindering effective adoption across projects. |

Defects: inconsistent application of Lean principles leads to errors and quality deviations. Overprocessing: different teams follow varied methods, causing duplication of effort and inefficiency. Waiting: uncertainty in procedures delays task execution and decision-making. Underutilized Talent: employees’ Lean knowledge and initiative remain unused without structure. Structural Waste: inconsistent methodologies or unclear Lean standards lead to construction errors and rework. Non-hazardous Waste: lack of standardized processes increases material wastage and poor handling. Demolition Waste: misaligned methods among teams can result in incorrect installations that require removal and rebuilding. |

|

| 43 | Logistics problems (T4) | Small et al. (2017) | Challenges in material delivery, site access, and resource management, impeding the smooth implementation of LC practices reliant on efficient logistics for project optimization. |

Transportation: inefficient movement of materials and equipment increases handling time and cost. Waiting: project delays occur when materials, tools, or components do not arrive on time. Motion: extra movement of workers searching for or moving materials. Inventory: poor logistics management leads to either material shortages or excessive stockpiling. Packaging Waste: excess packaging from multiple small or redundant deliveries. Structural Waste: delays and material mismanagement result in quality deterioration or improper installation. Non-hazardous Waste: disorganized logistics lead to material damage and unnecessary disposal on-site. |

|

| 44 | Complexity of LC implementation (T5) | Alarcón et al. (2002) | Denotes the intricate nature of integrating LC principles into existing workflows, posing challenges and hindering widespread adoption within the construction industry. |

Overprocessing: redundant procedures arise as firms overcomplicate Lean adoption. Waiting: delays in decision-making and adoption due to confusion or uncertainty. Underutilized Talent: employees lack clarity on roles or are excluded from Lean initiatives. Structural Waste: misunderstandings and misapplications of Lean methods cause execution errors and rework. Non-hazardous Waste: general inefficiencies and material misuse from uncoordinated Lean processes. Demolition Waste: poor understanding of Lean coordination can lead to incorrect assembly, requiring partial demolition. |

|

| 45 | Inaccurate and incomplete designs (T6) | Ahmed et al. (2021), Moyo and Chigara (2021), Musa et al. (2023), Bayhan et al. (2019), Metlej (2021), and Sholanke et al. (2019) | Denotes deficiencies in project plans, leading to disruptions and inefficiencies during construction, thereby hindering the smooth implementation of LC practices. |

Defects: incomplete or inaccurate designs lead to rework and errors in execution. Overprocessing: additional revisions and clarifications are needed due to incomplete drawings. Waiting: construction activities are delayed while design issues are resolved or clarified. Structural Waste: incorrect or incomplete design details lead to rework and inefficient material usage. Demolition Waste: errors in design can result in the need to remove and rebuild completed sections. Non-hazardous Waste: repeated adjustments and redesigns generate surplus materials and general site waste. |

|

| 46 | Others (O) | Difficult nature of construction industry (O1) | Moyo and Chigara (2021), Al Balkhy et al. (2021), Pedrosa et al. (2023), Bajjou and Chafi (2018), and Martinez et al. (2019) | Refers to the inherently complex and unpredictable characteristics of construction projects, posing challenges to the streamlined implementation of LC methodologies. |

Waiting: unpredictable site conditions and uncertainties delay progress and disrupt workflow. Overprocessing: complex project conditions require redundant steps and repeated verification. Defects: variability in materials, methods, and labor increases the likelihood of errors. Structural Waste: unpredictable conditions lead to rework, excess material use, and inefficiencies. Excavation Waste: site difficulties such as unstable ground conditions increase redundant earthwork. Non-hazardous Waste: complex operations generate additional debris and general construction waste. |

| 47 | Dependence on many subcontractors (O2) | Ahmed et al. (2021) and Moyo and Chigara (2021) | This signifies a fragmented supply chain and coordination challenges, hindering the cohesive implementation of LC practices across project phases. |

Waiting: project delays occur as different subcontractors wait for preceding tasks to be completed. Defects: inconsistent workmanship and lack of coordination among subcontractors lead to errors. Transportation: frequent movement of materials and resources between subcontractors increases inefficiency. Structural Waste: poor coordination among subcontractors leads to misalignment and rework. Packaging Waste: repeated handling and transport of materials between subcontractors increase packaging use. Non-hazardous Waste: fragmented workflows and overlapping activities cause excess general site waste. |

|

| 48 | Long implementation period (O3) | Alarcón et al. (2002) | This indicates a prolonged timeframe required for transitioning to LC practices, potentially delaying the realization of benefits and hindering organizational buy-in. |

Waiting: prolonged timelines slow progress and reduce workflow efficiency. Overprocessing: extended implementation leads to unnecessary steps, reviews, and duplicated efforts. Underutilized Talent: lengthy projects cause employee fatigue and reduced motivation, lowering productivity. Structural Waste: extended project duration increases the risk of rework and material deterioration. Non-hazardous Waste: prolonged site activity leads to accumulation of general waste and unused materials. |

|

| 49 | Lack of integrity in the production chain including clients, materials, suppliers, and subcontractors (O4) | Small et al. (2017) and Bashir et al. (2015) | Denotes ethical lapses and trust issues, impeding the smooth execution of LC principles reliant on collaborative and transparent relationships throughout the supply chain. |