Abstract

Introduction:

Digital technologies are reshaping the economy and, by restructuring factor flows and resource allocation, are significantly affecting urban development. Focusing on firms' digital technology behavior, this paper examines how digital technology improves the efficiency of new-type urbanization under the dual mechanisms of government and market, and what effects follow, with the aim of broadening the theoretical account of the relationship between digitization and urban development.

Methods:

Using city-firm matched panel data that link Chinese prefecture-level cities and A-share listed companies for 2005–2022, we construct a large-sample database with a long time span and wide coverage that closely reflects city-firm linkages and apply a fixed-effects model with both city and firm effects for identification to strengthen the reliability and robustness of the estimates.

Results:

The empirical findings are as follows. (1) Firms' use of digital technologies significantly improves the efficiency of new-type urbanization. (2) On the government side, digital technologies enhance the government's digital focus while reducing the distortion caused by fiscal interventions, thereby improving the governance environment. On the market side, they encourage the agglomeration of producer services and enhance the allocation of human capital, forming a market transmission chain that promotes gains in urbanization efficiency. (3) The positive effect of digital technologies is stronger in the eastern and central regions, in cities with lower levels of environmental recycling, in higher-income cities, and in cities with more advanced industrial structures.

Discussion:

Drawing on a micro-level perspective of firm behavior, this paper uncovers the mechanisms through which digital technologies drive new-type urbanization and offers empirical evidence to inform policies that coordinate urban digital transformation with new-type urbanization.

1 Introduction

The principal challenge of new-type urbanization lies in improving efficiency under persistent structural constraints. Existing studies show that the agglomeration of pollution-intensive industries intensifies environmental damage (Charfeddine, 2017), excessive population concentration leads to urban congestion and infrastructure overload (Jedwab et al., 2015), and high housing prices in central areas induce counter-urbanization and spatial differentiation (Remoundou et al., 2015). For China and other developing countries, conventional urbanization has promoted industrialization and economic growth, but it has also generated a series of negative externalities, including resource misallocation, ecological constraints, and unequal access to public services (Marrara, 2026; Tran and Tran, 2025). To address these structural contradictions, China has elevated “people-centered” new-type urbanization to a national strategy since 2013. Relevant policy documents define the core content of new-type urbanization as a people-centered approach to urban citizenship, compact and efficient spatial development, coordinated regional integration, and sustainable development with an emphasis on safety and resilience.1 As a result, the aim of urbanization has shifted from expanding scale to improving efficiency, stressing the coordinated development of population, space and the environment under resource and environmental constraints. Against this background, a pressing question is whether digital technology (DT) can ease the structural strains inherent in traditional urbanization and what mechanisms enable DT to enhance new-type urbanization efficiency (NTUE).

Advances in DT provide new technological conditions and governance tools for easing the structural tensions associated with traditional urbanization. DT emerged from the post-war commercialization of information and communication technologies (ICT; Ceruzzi, 2003) and has continued to evolve under the support of the TCP/IP protocol, expanding from basic computing and communication to browsers, search engines, mobile communications, and industrial internet platforms. Over time, they have come to constitute the core infrastructure of the digital economy (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019). In China, the gross value added of core industries in the digital economy has risen steadily, reaching 12.76 trillion yuan in 2023 and accounting for 9.9% of GDP,2 which underscores the macroeconomic importance of DT. At the firm level, DT, such as industrial Internet platforms, cloud computing, and data analytic services have improved production organization and supply chain coordination and provided low-cost digital solutions for small and medium-sized enterprises. Importantly, these digital innovations do not remain confined within firm boundaries. They diffuse and accumulate across urban space through supply-chain linkages, knowledge spillovers and platform externalities, creating a considerable city-scale endowment of DT (Deng et al., 2025; Soghi et al., 2025; Lingfu et al., 2024). With such accumulated capacities, cities can enhance people-centered and sustainable NTUE by improving factor matching, strengthening public-service provision, and facilitating green transition (Berlingieri et al., 2025; Yusuf et al., 2025; Gusarova et al., 2025). Accordingly, this study aggregates firm-level digital patents at the city level to capture a city's DT endowment and, based on this measure, examines the impact of DT on NTUE as well as the mechanisms through which this impact is transmitted.

Research on DT has developed into a multi-level literature spanning technology adoption to urban governance. Early studies focused on ICT, examining its effects on service sector productivity (Hempell, 2005), economic welfare (Gani and Clemes, 2006), and the digital divide (Hanna and Qiang, 2010). With the widespread application of big data platforms and the Internet of Things, digital transformation has increasingly become a research focus, drawing attention to both firm-level digitalization and government digital governance (ElMassah and Mohieldin, 2019; Deng et al., 2021). In recent years, the rise of artificial intelligence has extended research into multiple dimensions, including labor markets, social structures and firm behavior (Makridakis, 2017; Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2019). It has shifted the perspective from the firm level to urban and regional governance. International experience shows that in Europe, digital transformation has helped improve urban energy efficiency and green innovation capacity, optimize resource use, and reduce carbon emissions (Hojnik et al., 2025). In the United States, smart technologies, through the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence and data analytics, have optimized urban management, enhanced public safety, and supported sustainable governance, thereby increasing urban attractiveness and influencing the urbanization process (Singh, 2025). In China, as the digital economy has developed rapidly, research has increasingly focused on the role of DT in areas such as innovation (Feng et al., 2022), carbon emissions (Zhang et al., 2022), and energy consumption (Ren et al., 2021). At the city level, existing studies have examined the relationship between the digital economy and high-quality urban development or spatial structure evolution, for example, the mechanisms through which comprehensive big data pilot zones affect high-quality urban development, and how the digital economy reshapes urban sprawl and industrial division (Guo et al., 2023; Wen et al., 2024). However, these studies generally emphasize the macro-level impact of digitalization on urban development or spatial patterns, and there remains a lack of systematic analysis of NTUE, a performance indicator centered on people and sustainability.

From the perspective of new-type urbanization, existing research still shows significant gaps in both theoretical characterization and empirical identification. On one hand, the formation of NTUE depends on the reallocation and coordination of population, industry, and the environment within urban space (Chen R. et al., 2025), a process largely driven by changes in firm production methods, organizational restructuring, and technology adoption (Alfaraz and Tully, 2025; Prasetyani et al., 2025). Relying solely on macro-level digital economy indices or city-level digital infrastructure is insufficient to reveal how DT, through micro-level firm behavior, becomes embedded in the allocation of urban factors and thereby influences urbanization performance oriented toward people and sustainability. On the other hand, existing studies pay limited attention to the specific channels through which DT alleviates the structural tensions of traditional urbanization, and a systematic framework considering both government and market dimensions has yet to be established. Moreover, existing studies have paid insufficient attention to the specific channels through which DT alleviates the structural tensions of traditional urbanization, and a systematic framework that considers both government and market dimensions has yet to be developed. In addition, measures of DT largely rely on macro-level composite indices, providing limited insight into its micro-level sources and the process through which it accumulates at the city scale. Overall, the current literature leaves several gaps to be addressed, including how to construct a city's DT endowment based on firm-level digital activity, how DT enhances NTUE through government and market mechanisms, and how to measure DT at the micro level and integrate it into urban analysis frameworks.

To address these gaps, this study develops a micro-to-city analytical framework that connects firm-level digital technology activity to NTUE. Specifically, using digital patent data from listed companies for 2005–2022, firm-level digital patents are matched to the city level to capture a city's DT endowment. These data are then combined with city-level NTUE indicators and other relevant statistics to form a city-firm panel dataset, which allows for a systematic examination of the impact of DT on NTUE. The analysis of underlying mechanisms focuses on both government and market dimensions. On the government side, the study examines whether DT enhances government digital attention and mitigates resource misallocation caused by fiscal interventions, thereby improving governance effectiveness and the efficiency of public service provision. On the market side, it analyzes whether DT promotes the agglomeration of producer services and optimizes the spatial allocation of high-quality human capital and employment matching, thus increasing factor allocation efficiency during urbanization. Given significant differences among cities in terms of geographic location, environmental recycling, population income, and industrial structure, the study further explores the heterogeneous effects of DT on NTUE across regional, environmental, income, and industrial dimensions, aiming to reveal a more detailed structural relationship between DT and urban development.

Compared with the existing literature, this study makes three main contributions.

Firstly, in terms of research perspective and focus, this study integrates DT and NTUE into a unified analytical framework and, starting from firms as micro-level actors, constructs the transmission chain linking enterprise digital patents, urban digital technology endowments, and NTUE. Unlike studies that primarily rely on macro-level digital economy indicators or city digital infrastructure (Zhang et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2023; Wen et al., 2024), we treat firm-level DT activity as the starting point of digitalization's impact on urbanization. By capturing the agglomeration of firm digital patents across urban space, we measure city-level DT endowment and thus more directly identify the effect of DT on NTUE, which is centered on people and sustainability.

Secondly, in terms of research content and mechanisms, this study systematically examines the specific pathways through which DT enhances NTUE from both government and market perspectives. Building on the overall positive effect of DT on NTUE, we further investigate the underlying mechanisms. On the government side, we assess whether DT improves urban governance performance and the efficiency of public service provision by enhancing government digital attention and reducing distortive fiscal interventions. On the market side, we examine whether DT increases factor allocation efficiency during urbanization by promoting the development and agglomeration of producer services and by optimizing the spatial distribution of high-quality human capital and employment matching. In addition, heterogeneity analysis is conducted to explore how the effects of DT vary across cities with different geographic locations, environmental recycling levels, population incomes, and industrial structures, thereby enriching the understanding of DT's role in both urban governance and market functioning.

Thirdly, with respect to data and methodology, this study introduces refinements and innovations in the measurement of DT and the construction of the sample. Compared with approaches that rely on macro-level digital economy indices (Chen R. et al., 2025; Wen et al., 2024), we use digital patent data from listed companies for 2005–2022 to construct a long city–firm panel dataset. City-level DT endowment is measured by aggregating firm digital patents, allowing for a more granular examination of the relationship between DT and NTUE. This data and methodological framework not only provides new empirical evidence for understanding China's digital transformation and new-type urbanization, but also offers a reference for other developing countries seeking to leverage micro-level firm data to enhance urbanization efficiency during their digitalization processes.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 develops the theoretical framework and proposes the research hypotheses. Section 3 presents the research context, model specification, variable definitions, and data sources. Section 4 reports the empirical results, including the baseline estimations, robustness checks, endogeneity treatments, heterogeneity analyzes, and mechanism tests. Section 5 offers discussion, conclusions, and policy implications, and further outlines the limitations of this study and potential directions for future research.

2 Mechanism analysis and research hypotheses

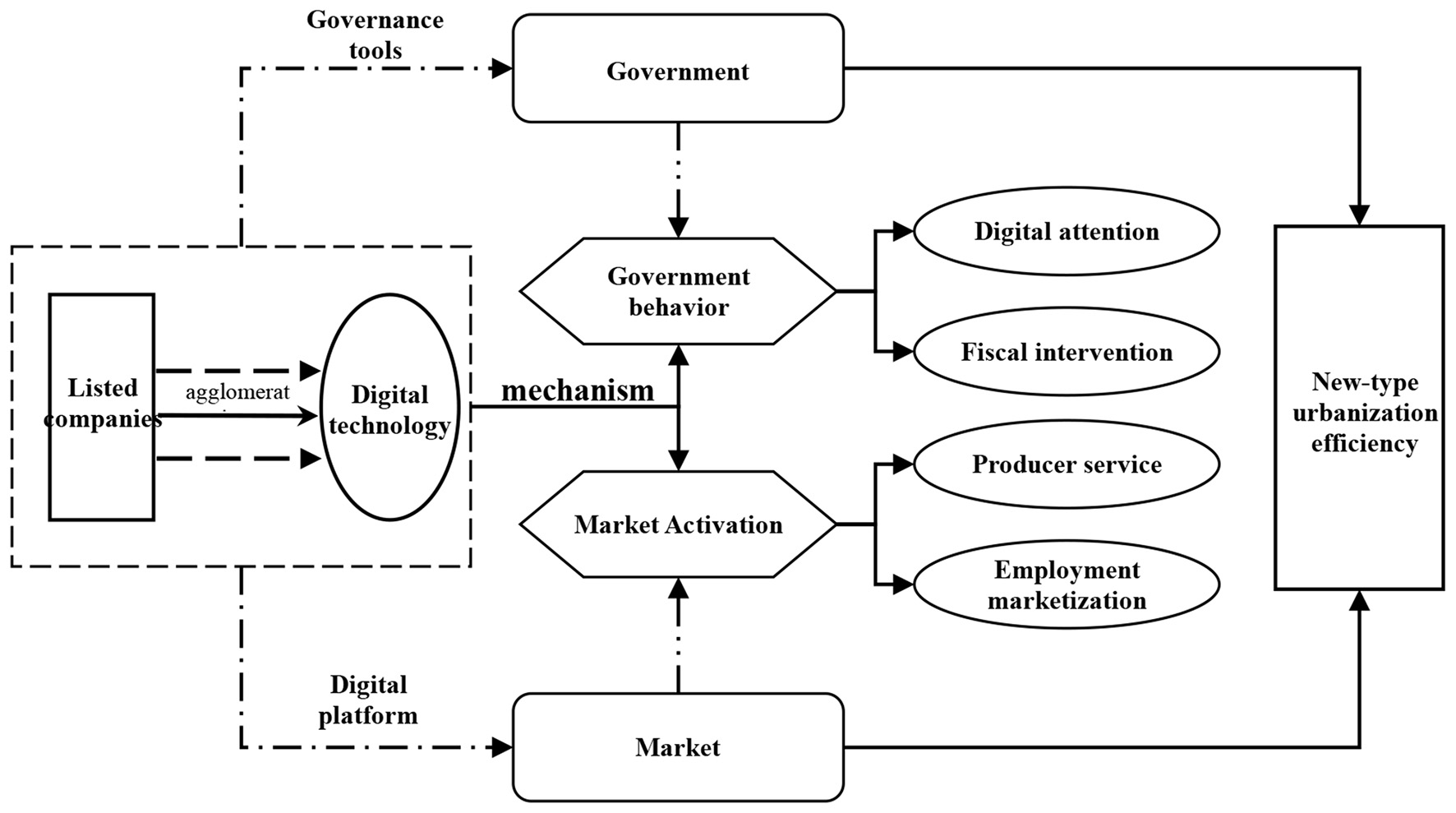

The improvement of NTUE fundamentally depends on whether population, industry, and spatial factors can be allocated efficiently under resource and environmental constraints through effective institutional and technological arrangements. As a general-purpose technology deeply embedded in urban systems, DT can influence NTUE directly by altering information structures, transaction costs, and governance capacity, and indirectly by reshaping government actions and market mechanisms. Based on this reasoning, this study develops the theoretical framework illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The impact mechanism of DT on NTUE.

2.1 The direct impact

DT has evolved from an auxiliary tool into a general-purpose technology deeply embedded in urban systems, directly enhancing NTUE by reshaping government governance logic and market functioning. On one hand, it enables governments to build efficient and transparent digital governance systems (Wang and Guo, 2024). On the other hand, it expands the boundaries of market platforms, improves managerial capabilities, and strengthens the market's micro-level support for urbanization by optimizing firm innovation and resource allocation. Under the influence of DT, government and market form a synergistic mechanism that jointly promotes the transition of urbanization from scale expansion to quality improvement.

From the governmental perspective, DT improves the information environment and broadens the policy toolkit. It has become not only a new impetus for urbanization expansion, but also a pivotal governance instrument for enhancing the quality of new-type urbanization. In terms of population urbanization, DT significantly reduces labor search and matching costs (Goldfarb and Tucker, 2019), enabling governments to monitor labor flows and structural changes in real time through tools such as facial recognition and cloud computing. This allows for more targeted employment and residency policies, improving the allocation efficiency of population urbanization (Autor, 2001). In ecological governance, 5G networks and automated monitoring technologies provide high-frequency, low-cost information inputs for environmental regulations (Wang and Guo, 2024). Governments can thus identify corporate emissions in real time and implement differentiated regulation, effectively reducing governance time and enforcement costs. This illustrates the technology-empowerment effect emphasized in digital governance theory (Dunleavy et al., 2006) and enhances urbanization efficiency under environmental constraints. Regarding economic space and industrial layout, governments deploy digital infrastructure such as fiber optic networks and telecom base stations to support factor flows and information exchange within cities and between urban and surrounding areas (Arhipova et al., 2020). Investments in digital public goods, including low-orbit satellite internet and city data platforms, further strengthen resource integration and information connectivity across regions, promoting industrial agglomeration and upgrading. At the same time, standardized data trading and service provision improve resource access for small- and medium-sized enterprises (Zhao et al., 2023). With the systematic embedding of digital governance tools in public services, regulation, and industrial policy, local governments are able to make decisions based on more comprehensive and precise information, gradually building a secure and trustworthy digital governance ecosystem (Zhang et al., 2021) that supports sustained improvements in NTUE through higher total factor productivity.

From the market perspective, DT provides a continuous micro-level impetus for new-type urbanization by reshaping firm resource allocation and spatial organization through platform-based transactions and enhanced managerial cognition. According to information asymmetry theory, market frictions stem from gaps in information (Akerlof, 1970), and digital platforms reduce search and bargaining costs, enabling efficient matching among multiple actors (Bonina et al., 2021). Firms use these platforms to coordinate order matching, payment settlement, and logistics, which not only improve operational performance but also advance digital transformation, fostering data-driven business models and flatter organizational structures (Laudien et al., 2024; Chatterjee et al., 2023). Platform control over data and rules further reshapes supply chains and location incentives, weakening traditional urban-rural boundaries and promoting the two-way flow of factors between cities, suburbs and rural areas. For instance, fresh e-commerce platforms connect peri-urban agriculture with urban consumption, shifting production from supply-driven to demand-driven and extending urban services through cold chains and warehouse distribution systems, thereby influencing urban expansion paths. At the same time, DT lowers internal communication and cross-regional coordination costs (Kovaite et al., 2020), reducing reliance on large-city agglomerations and encouraging firms to locate in second- and third-tier cities or on the peripheries of metropolitan areas. This decentralization mitigates the “large city disease” and improves the balance and quality of urbanization patterns. Digitalization also enhances managerial awareness of regulatory requirements and the expectations of residents and consumers, motivating firms under compliance pressure to integrate green supply chain objectives into corporate strategy (Kouloukoui et al., 2025). This aligns with government green urbanization policies and further increases factor allocation efficiency as well as NTUE.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 1. Digital technology significantly enhances the efficiency of new-type urbanization.

2.2 Influencing mechanism

2.2.1 Government behavior

DT is systematically reshaping government governance mechanisms. On one hand, governments improve the efficiency of public service provision and administrative performance by developing government data platforms and intelligent regulatory systems, promoting a more refined and real-time operation of cities (Martins and Veiga, 2022). On the other hand, the digital economy has been incorporated into local performance evaluations and competitive development goals. Local governments introduce digital policies and optimize the business environment to attract capital and industrial clusters, thereby strengthening the allocation of resources to the digital sector (Briglauer et al., 2019; Falck et al., 2014; Xu, 2011). However, if interventions are poorly timed or executed, digital-related investments can become excessive and lead to resource misallocation, undermining fiscal efficiency and amplifying institutional distortions (Gao et al., 2017; Liao and Liu, 2013). Within this context, DT profoundly affects the mechanisms shaping NTUE by shifting government priorities and decision-making logic, and by restructuring fiscal expenditures and resource allocation.

In terms of governance focus, DT enhances NTUE primarily by strengthening government “digital attention.” The widespread application of technologies such as big data, cloud computing, the Internet of Things, and artificial intelligence enables governments to access high-frequency data on population flows, energy use, and pollution emissions in real time through integrated platforms such as “one-stop governance” and “maximum once visits.” This significantly reduces information collection and regulatory costs while improving the efficiency and precision of public service provision (Yusuf et al., 2025; Martins and Veiga, 2022). Digital governance theory suggests that the integration of DT helps enhance the accuracy of government resource allocation and policy implementation, thereby promoting more intelligent and efficient urban governance. As a result, indicators related to population citizenization, intensive spatial use, and environmental quality are more likely to become priorities in government evaluation and decision-making, directing additional policy resources to key aspects of new-type urbanization. At the same time, the growth and employment effects brought by the digital economy reinforce competitive investment by local governments in digital development (Xu, 2011; Briglauer et al., 2019), further deepening governmental attention to DT in planning, regulation, and institutional innovation. Digital attention thus serves as a crucial mediating link connecting city-level DT endowment and NTUE.

Regarding fiscal behavior, DT provides new tools for optimizing fiscal interventions and enhancing policy implementation. Existing studies show that fiscal interventions have significant effects on urban development, and their distorting effects cannot be ignored (Liao and Liu, 2013; Gao et al., 2017). By leveraging applications such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and digital twins, DT facilitates the digital transformation of urban and rural infrastructure, integrates urban-rural supply chains, and optimizes the allocation of factors such as land and energy (Singh et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2025). This not only improves resource allocation efficiency but also supports the citizenization of rural-to-urban migrants, thereby enhancing the quality of population urbanization. At the same time, DT provides governments with more precise investment decision support, helping to curb overinvestment and resource misallocation commonly associated with traditional fiscal interventions (Liao and Liu, 2013). Through digital platforms, governments can monitor firm development and regional dynamics in real time, increasing transparency and targeting of fiscal expenditures. This supports economic urbanization while strengthening environmental regulation and promoting green-oriented policies, fostering a positive interaction between economic and green urbanization and thereby overall enhancing NTUE.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 2a. Digital technology enhances the efficiency of new-type urbanization by strengthening governments' digital attention.

-

Hypothesis 2b. Digital technology improves the efficiency of new-type urbanization by mitigating the distortionary effects of government fiscal intervention.

2.2.2 Market activation

DT has profoundly altered market functioning by driving automation and the emergence of new industries, producing notable changes in labor structures and industrial layouts (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2020; Gathmann et al., 2024). This process not only fosters the growth of producer services but also reshapes urban employment patterns. The key mechanism lies in DT-driven expansion of producer services, which absorbs and concentrates high-skilled labor while providing opportunities for low-skilled workers to transition to new positions, particularly in the lower segments of the service chain. Through this reallocation in the labor market, urban market efficiency is enhanced, providing a sustained impetus for new-type urbanization.

At the industry level, the transformation of high-skilled and low-skilled jobs driven by DT constitutes a key channel through which producer services affect NTUE. Technologies such as artificial intelligence and robotics simplify and partially replace routine manufacturing tasks, displacing some low-skilled positions (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2020). Through training and skill upgrading mechanisms, these workers have the opportunity to transition into DT-supported producer services (Li W. et al., 2024). According to theories of labor division and comparative advantage, the movement of labor into specialized, knowledge-intensive roles helps optimize factor allocation while achieving efficient labor transfer and industrial specialization (Yan et al., 2025). At the same time, DT shortens the interaction distance between producers and consumers and expands the spatial reach of residence and employment, providing new opportunities for low-skilled workers to participate in the downstream segments of producer services. Their engagement at the lower end of the service chain not only alleviates employment pressure but also extends industrial chains and service coverage (Qiao and Chen, 2025), promoting the expansion of producer services to city outskirts and metropolitan areas. This industrial spatial restructuring blurs traditional urban boundaries and enhances NTUE.

From the perspective of employment structure evolution, DT provides an endogenous market-driven impetus for NTUE by optimizing labor allocation and enhancing industrial efficiency. On one hand, the substitution effect of DT on low-skilled positions drives labor toward high-skilled, high-value producer services (Nguimkeu and Okou, 2021), improving overall employment quality and accelerating the transformation of urban employment structures toward knowledge-intensive and service-oriented sectors. On the other hand, as the digital transformation of traditional industries deepens, factors increasingly concentrate in more efficient and digitally advanced firms and business models (Xu et al., 2025), promoting the expansion of state-owned, foreign-invested, and large enterprises while gradually absorbing low-efficiency employment previously dispersed in individual private sectors. This process reshapes and optimizes the composition of market actors. Moreover, DT encourages cities to shift from traditional commodity supply toward scaled, standardized, and diversified innovative service provision (Wu et al., 2023), restructuring urban economic patterns alongside changes in employment forms. Although these adjustments may increase short-term pressures on the employment structure, in the long term, this structural upgrading helps establish a high-efficiency labor market compatible with new-type urbanization, providing a solid foundation for the sustained improvement of NTUE.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 3a. Digital technology enhances the efficiency of new-type urbanization by promoting the development of producer services.

-

Hypothesis 3b. Digital technology enhances the efficiency of new-type urbanization by optimizing employment structures.

3 Research background, design, variables, and data

3.1 Research background

In 2016, the digital economy of China entered a period of accelerated growth, and the value-added part of GDP reached 30 percent and higher. In a context of more proactive national policy advice and increased interest in capital markets, listed companies started to consider DT as one of their strategic priorities. This was a change that appeared in corporate annual reports and an increase in expenditure on R&D. Top companies also developed the direction toward closer collaboration of the digital and real economy and increased the amount of R&D investments in fields like artificial intelligence, big data and financial technologies, accelerating the spread and penetration of DT into the organization.

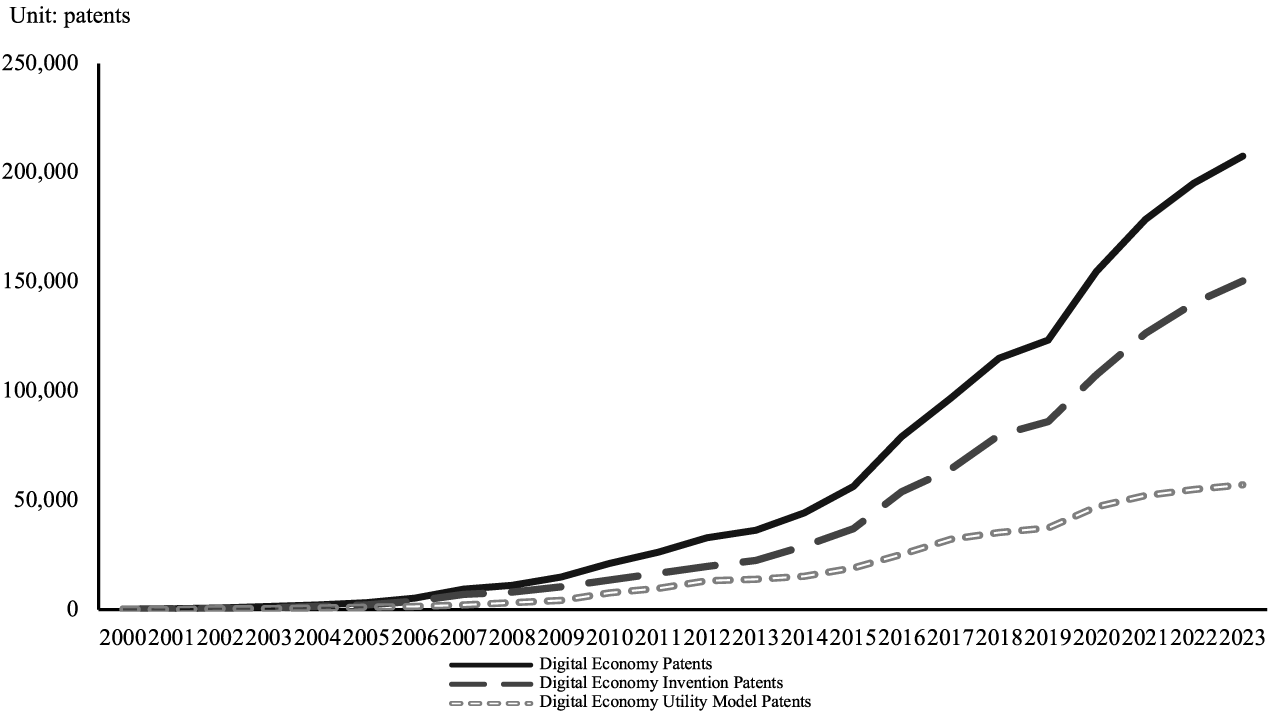

Figure 2 represents the dynamics of the development of patent applications in the digital economy. The matching of the data in the lists of CSMAR-identified firms to the 2021 Statistical Classification of the Digital Economy and Its Core Industries identifies these patents. The black bars capture the total black bars are patents of the digital economy, which is a combination of invention patents (gray bars) and utility model patents (outlined bars). Before 2015, there was a stable growth in patenting digital technology. Since 2015, the number of applications has been growing faster, which is in line with the acceleration of the digital economy in 2016. Within a period of time, the disparity between the invention and utility model patent has grown showing that the listed firms are now focused on achieving more of a quality innovation with a more targeted focus toward the immediate core technologies that have longer protection length alongside a higher level of technological content.

Figure 2

Digital economy patents of Chinese listed firms, 2000–2023.

In this perspective of the institutional and market factors, the enhanced adoption of DT among listed companies indicates the coordinated efforts of government users and market incentives. From one perspective, as of end-2022, A-share issuers in the digital economy had the representation of about a quarter of all listed companies and over two-thirds of the listed companies had already embarked on digital transformation, which means that DT has turned into a significant tool for competitive success and ensuring structural modernization. At the same time, central-level policies focusing on the digital economy were able to grow significantly after 2017 and, by 2022, were assembled into a rather consistent set of policies that stabilized institutional expectations and offered long-term support to digital-technology innovation and dissemination. Overall, the mass implementation and the accelerated development of DT among the listed companies were transferred to the prefecture-city level after the change in corporate actions and the enhancement of the innovativeness of regions, contributing to the economy geography of China and the direction of new-type urbanization.

3.2 Model design

To examine the impact of DT on NTUE, this study constructs the following baseline model.

In this model, the dependent variable NTUEi,t denotes NTUE of city i in year t. The key explanatory variable DTi,t captures DT, while Controlsi,t represents a set of city-level control variables. μi and μt denote city fixed effects and year fixed effects, respectively, and εi,t is the random disturbance term. To address potential within-group serial correlation, robust standard errors clustered at the city level are employed. In this study, the coefficient of primary interest is α1, which measures the change in urbanization efficiency associated with a one-unit increase in DT. To validate Hypothesis 1, α1 is expected to be significantly positive, indicating that DT significantly enhances NTUE of prefecture-level cities.

3.3 Data sources and processing

DT is proxied using patent data aggregated from Shanghai- and Shenzhen-listed A-share firms, which constitute the main micro-level sample. Relative to city-level patent counts, the digital-technology patenting of leading firms more plausibly reflects the depth of technological diffusion and the quality of innovation. Guided by the availability of NTUE measures, the study period spans 2005–2022. Firm-level inputs for DT construction are drawn primarily from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, with missing items complemented using the China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS). Data on NTUE, city characteristics, and other urban indicators are mainly collected from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook, the China Provincial Statistical Yearbook, and the statistical yearbooks of prefecture-level cities. For observations that remain unavailable, we additionally consult prefectural Statistical Bulletins on National Economic and Social Development, the CEIC database (CEdata), and the EPS Data Platform.

To improve data validity and reliability, we implement several cleaning and screening steps. We, first of all, eliminate financial institutions, ST/PT firms, firms holding an IPO within the sample period, and delisted firms. Second, we delete firms that miss values on core variables and select only those which have a minimum of 5 years of complete observation. Thirdly, before aggregating city-level NTUE, we would cross-check and standardize indicator names that differ across years (e.g., industrial dust emissions vs. particulate emissions in industrial exhaust) by hand and leave the rest of the missing data imputed through interpolation.

3.4 Variable selection

3.4.1 Dependent variable: new-type urbanization efficiency (NTUE)

The concept of new-type urbanization was officially established by the Chinese government in the National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020), which was published in 2014. The new-type urbanization is more focused on resource conservation, intensive development, ecological livability and other similar green ideals unlike its conventional counterpart, and, as a result, the new model is much closer to the overarching idea of green urbanization. In line with the efficiency-evaluation strategy of Lv et al. (2021), we quantify NTUE through Slack-Based Measure (SBM) model of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). The DEA-SBM method has two major benefits over the typical efficiency methods (Wang et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2023). First, it has the capability of accommodating desirable and undesirable outputs including the emission of pollutants. Second, the method is non-parametric, thus does not presuppose a functional form, thereby boosting flexibility and applicability in heterogeneous cities (Bartosiewicz et al., 2024). These are properties that enable the model to combine effectively socioeconomic achievements, and the environmental forces that come with urbanization. Moreover, the DEA-SBM framework incorporates the traditional socioeconomic benefits, multiples inputs, and environmental performance into one analytical framework, which corresponds to the ecological spirit of new-type urbanization and ecological sustainability needs. This makes it well-suited for assessing urbanization efficiency in the context of green transition. Table 1 reports the input and output indicators used to construct NTUE. The resulting efficiency score is strictly positive, with higher values indicating greater NTUE.

Table 1

| Type | Element name | Indicator selection |

|---|---|---|

| Resource inputs | Land | Urban administrative area size |

| Capital | Total fixed asset investment | |

| Labor | End-of-year urban employment numbers | |

| Energy | Total electricity consumption data | |

| Desirable outputs | Economic benefits | Per capita GDP |

| Social benefits | Total retail sales of consumer goods | |

| Ecological benefits | Urban green space area | |

| Undesirable outputs | Environmental outputs | Industrial SO2 emissions |

| Industrial dust emissions |

Input-output system for NTUE.

3.4.2 Explanatory variable: digital technology (DT)

DT has expanded from early ICT and internet-based applications toward the broader digital economy and, more recently, artificial intelligence, with these technological domains advancing through cumulative and mutually reinforcing innovation cycles (Arshad et al., 2025; Ren et al., 2021; Makridakis, 2017). Because neither the digital economy nor artificial intelligence is fully covered by standalone patent classes, empirical identification typically draws on government or industry taxonomies, supplemented by firm disclosures when necessary. In the empirical literature, DT is most often proxied using either financial-report text mining or patent-based indicators (Zhao and Wu, 2025; Chen and Wang, 2025). Relative to keyword measures from annual reports, which may reflect managerial discretion or rhetorical inflation, patent data provide a more verifiable and countable signal of technological effort, especially since invention patents are generally associated with higher degrees of novelty and substantive technological progress (Xu et al., 2024; Chen and Wang, 2025). Following the Classification of the Digital Economy and Its Core Industries (2021) and the procedure in Xu et al. (2024), we identify listed firms' DT patents by mapping IPC codes to the relevant digital-economy categories, and then compute firm-level totals. Since there are indications that scale-specific features of listed firms, like updated disclosure demands, and appropriate performance in scale, profitability, and innovation, are typical of superstar firms (Ayyagari et al., 2023), we further consolidate DT-related patents in all listed companies in each prefecture-level city. These city-level totals are then normalized into the DT measure which undergoes analysis.

3.4.3 Control variables

So as to remove confounding factors in the regression, and to maximize the reliability and validity of the results, we incorporate a sequence of control variables. In the footsteps of Xu et al. (2021), these controls reflect general, industrial, and economic aspects of the city levels at the prefecture. The level of manufacturing development (Manufacture) is in terms of the manufacturing location quotient of the city. The scale of Internet development (Internet) is in turn proxyed by the number of online subscriptions to mobile Internet accessibility per 100 inhabitants, which can be seen as an indicator of Internet coverage of a region. The status of infrastructures (Infrastructure) is gauged by the size of road area per capita, which shows the development of city infrastructures. The Theil index is the rationalization of industrial structure (Theil), that is, the description of the level of structural rationality in the industrial development of a city. The level of openness (Open) is gauged as a ratio between total imports and exports (in RMB converted into the mean annual exchange rate) to regional GDP.

3.4.4 Descriptive statistics

The three sets of variables employed in analysis as indicated in Table 2 are the dependent variable, the principal explanatory variable and the controls. In every measure, the table provides a report of the category of variable, notation, means, standard deviation, lower quartile, upper quartile, and the number of observations. NTUE means 0.3855 and standard deviation 0.1940. The 25th and 75th percentiles are 0.2629 and 0.4458, respectively. The above statistics imply an average degree of NTUE that is moderate and the cross-city dispersion is high, and the distribution is skewed to the right. The mean of DT is 0.1198 and the standard deviation is 0.6771 with lower and upper quartile 0.0000 and 0.0250, respectively. This trajectory suggests that the spatial management of DT is highly concentrated with majority of cities recording very low rates with a few being able to score a disproportionate rate of digital operations. The patterns of description are congruent with the uneven regional distribution of DT in China and its performance of urbanization. The means of manufacturing development, internet development, infrastructure conditions, industrial-structure rationalization, and openness as the control variables are 1.0368, 0.2341, 17.2142, 0.2523 and 0.2314, respectively, and it can be noticed that the development conditions of prefecture-level cities are significantly varied. All in all, the descriptive statistics indicate two major regularities concerning the NTUE and increasing yet rather low and the DT being extremely imbalanced among cities, i.e., displaying a high degree of inter-city heterogeneity.

Table 2

| Type | Variable | Mean | SD | P25 | P75 | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | NTUE | 0.3855 | 0.1940 | 0.2629 | 0.4458 | 3484 |

| Independent | DT | 0.1198 | 0.6771 | 0.0000 | 0.0250 | 3484 |

| Control | Manufacture | 1.0368 | 0.5277 | 0.6716 | 1.2940 | 3484 |

| Internet | 0.2341 | 0.2025 | 0.0889 | 0.3192 | 3484 | |

| Infrastructure | 17.2142 | 7.7278 | 11.7411 | 21.5134 | 3484 | |

| Theil | 0.2523 | 0.1991 | 0.0962 | 0.3581 | 3484 | |

| Open | 0.2314 | 0.3678 | 0.0444 | 0.2442 | 3484 |

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Baseline results

Table 3 displays the baseline results of the impact of DT on NTUE with the support of an unbalanced panel. The specifications [i.e., Columns (1)–(4)] report, respectively, the specifications with city-clustered standard errors, time fixed effect added in models, time and city fixed effect added in models, and fully specified model, which further adjusts the entire body of the covariates. The coefficient on DT is also estimated to be positive and significantly greater at the 1 percent level in all specifications with or without control variables and whether or not two-way fixed effects are assumed. Having paid attention to the specification that is preferred in Column (4), the coefficient of DT appears to be around 0.0506. Other things being equal, an increase of one standard-deviation in DT translates into an average increase of 8.9 percent in NTUE, meaning that a large increase in the stock of digital-technology patent in a city can result in a 10-percent plus increase in NTUE. Such findings suggest that the digital innovation by listed firms which are regularly considered star enterprises can be broadcaste to the level of the city and is correlated with the quantifiable improvements in the quality of urbanization. The results empirically present Hypothesis 1 and highlight the utility of DT in enhancing the quality of urban development (Ayyagari et al., 2023). This trend can be also associated with the evidence reported by Xu et al. (2024), Gao and Wen (2025) and Gharbi et al. (2025), who capture in their studies as of Chinese cities, cross-country sample of 100 economies, and extended European regions, respectively, that DT or the digital economy results in positive impact on urban development quality and green transformation. On the whole, the findings support the opinion that DT has emerged as relevant source of the enhancements in the quality of urban development within a constrained set of resources and environment.

Table 3

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTUE | ||||

| DT | 0.0662*** (0.0103) |

0.0566*** (0.0117) |

0.0488*** (0.0129) |

0.0506*** (0.0101) |

| Manufacture | −0.0259 (0.0170) |

|||

| Internet | 0.0248 (0.0513) |

|||

| Infrastructure | −0.0001 (0.0012) |

|||

| Theil | −0.1197*** (0.0380) |

|||

| Open | 0.0239 (0.0360) |

|||

| Constant | 0.3775*** (0.0095) |

0.3787*** (0.0094) |

0.3796*** (0.0015) |

0.4274*** (0.0366) |

| Year FE | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual FE | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 |

| Adj R2 | 0.0531 | 0.1754 | 0.6309 | 0.6342 |

Baseline regression results.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.2 Robustness tests

In order to provide a robustness assessment of the baseline results, we carry out a set of robustness checks on two complementary fronts. The first group of tests looks at how sensitive the findings are to other measures and frames of the most important variables. The second set evaluates the robustness in relation to shifts in the sample choice and model specification, and thus it evaluates whether the approximated effects remain consistent in the context of varying empirical conditions.

4.2.1 Robustness: measurement and construction of indicators and variables

In the robustness analyses pertaining to the constructions of the indicators and variables, we replace the key explanatory and dependent variables with alternative measures and apply winsorization to some vital variables in order to reduce the impact of an outlier.

In order to confirm that the results of the baseline are not a product of the specific DT proxy, we develop two alternative indicators. First, we take the sum of the patents of digital inventions at the prefecture level (DT_i). Since invention patents often reflect greater levels of content technological and a higher level of protection, they are more able to describe substantive improvements in DT. Second, we take the aggregate stock of patent of listed companies in each prefecture (patents). Given that listed firms are commonly viewed as leading actors in local innovation systems, their overall patent holdings can serve as a broad proxy for the intensity of DT-related innovative activity.

In order to further ascertain the risk that the compiled baseline evidence relies on the given proxy for the dependent variable, we develop two alternative measures of NTUE using the methods of Wang et al. (2016) and Chen et al. (2023). To be more precise, we estimate a DEA-based CCR efficiency score and a Malmquist index of productivity of 2006–2022. Under this specification, labor input is proxied by the annual average number of urban employees, capital input is measured by total fixed-asset investment constructed via the perpetual-inventory method, and energy input is captured by annual urban energy consumption expressed in standard coal equivalents. Output is used as GDP and industrial sulfur dioxide emission, industrial particulate emission and industrial wastewater discharge are used as undesirable outputs. Due to data availability, these alternative factors are estimated for 2006–2022. Notably, when 2005 is removed as an element of the initial sample, the results make no difference to the baseline regression inferences, which also provides evidence of the robustness.

Regarding the winsorization of key variables, we consider that a few cities may exhibit extreme values in DT, NTUE, and other similar variables, which could influence the stability of the regression results. Thus, a two-sided 1% winsorization is applied to the primary continuous variables.

Table 4 presents the results of the above three robustness checks in Columns (1) to (5). The coefficients on DT-related variables remain significantly positive across all specifications, which supports the conclusion that digital transformation significantly enhances NTUE.

Table 4

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTUE | NTUE2 | NTUE3 | NTUE | ||

| DT | 0.0439*** (0.0078) |

0.0447*** (0.0343) |

0.1036** (0.0414) |

||

| DT_i | 0.0597*** (0.0082) |

||||

| Patent | 0.0144*** (0.0027) |

||||

| Constant | 0.4308*** (0.0366) |

0.4461*** (0.0396) |

0.4043*** (0.0329) |

0.5991*** (0.0343) |

0.4511*** (0.0369) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3,484 | 3,062 | 3,322 | 3,322 | 3,484 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6349 | 0.6356 | 0.7010 | 0.7092 | 0.6303 |

Robustness tests: measurement and construction of indicators and variables.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.2.2 Robustness: estimation-setting adjustments

We subject our estimation settings to a series of robustness checks. This is done through four complementary approaches: sample completion, the exclusion of particular event windows, adjustments to the clustering of standard errors, and the adoption of an alternative estimation method.

(i) To reduce missing observations caused by the uneven spatial distribution of listed firms, we set the value of DT to zero for prefecture-level cities that contain no listed companies. This treatment allows us to retain these cities in the analysis and expand the dataset into a balanced panel comprising 282 prefecture-level cities. (ii) To mitigate potential contamination from major event windows, we note that the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 shock from 2020 onward may have influenced listed firms' innovation activity and the urbanization process through disruptions to financial markets and the real economy. Accordingly, we re-estimate the model after excluding the subsamples for 2008–2009 and for 2020–2022, respectively. (iii) Regarding the clustering scheme, we change the clustering level of standard errors from the prefecture to the province, to account for potential correlation among cities within the same province. (iv) For the alternative estimation method, we employ the System GMM (SYS-GMM) estimator to conduct a dynamic panel data estimation of the baseline model and include first- and second-order lags of NTUE in the specification.

Columns (1)–(5) of Table 5 report the results of the four robustness exercises in sequence. Under the SYS-GMM specification, the diagnostic tests are well-behaved: the Hansen test does not reject instrument validity, AR (1) is present as expected, and AR (2) is not significant. Across all specifications, the coefficients on the digital-technology variables remain positive and statistically significant. Taken together, these results indicate that the baseline inference is not driven by any single estimation setting.

Table 5

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTUE | SYS-GMM | ||||

| DT2 | 0.0488*** (0.0110) |

||||

| DT | 0.0480*** (0.0110) |

0.0654*** (0.0102) |

0.0506*** (0.0102) |

0.0181** (0.0072) |

|

| NTUEt − 1 | 0.6414*** (0.0501) |

||||

| NTUEt − 2 | 0.1640*** (0.0395) |

||||

| Constant | 0.4348*** (0.0300) |

0.4243*** (0.0376) |

0.4216*** (0.0310) |

0.4274*** (0.0328) |

−8.3871*** (2.8826) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cluster | id | id | id | Province | id |

| Hansen J-test | 0.110 | ||||

| AR (1) | 0.000 | ||||

| AR (2) | 0.646 | ||||

| N | 5,076 | 3,138 | 2,834 | 3,484 | 3,159 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6071 | 0.6281 | 0.6565 | 0.6342 | |

Robustness tests: estimation-setting adjustments.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.3 Endogeneity tests

Endogeneity is another aspect of empirical analysis that should be tackled. Here, we address possible endogeneity issues by a combination of instrumental variable (IV) estimation, Heckman two-stage procedure and the way to handle omitted-variable bias. The combination of these methods is useful in reducing endogeneity due to reverse causality, sampling bias, unknown heterogeneity, and error measurement. This multifaceted identification strategy would reduce endogeneity bias and increase the validity of our underlying findings.

4.3.1 IV method

In accordance with the instrumental variable construction approach of Nunn and Qian (2014) and with the specifications used by Ji and Wang (2024), we form two types of interaction-based instrumental variables of DT. The interaction between the spherical distance of each prefecture-level city to Hangzhou and one period lag of DT is the first tool. The relevance requirement of an instrumental variable is met in the construction of this instrument. The distance sphere quantifies the distance between every city to the Chinese capital of digitalized economy Hangzhou that is widely considered to be the center of the Chinese digital economy. Hangzhou is the headquarters of Alibaba whose technological environment, mobile payment, e-commerce like Taobao and Tmall, and the Alipay system has been in the driving seat in designing DT in the country. The cities that are very close to Hangzhou are likely to enjoy more technological spillovers and have more ability to absorb DT. When this distance measure is interacted with lagged DT, the correlation with current DT is even increased further. In regard to the exclusion restriction, geographic conditions predefine the spherical distance, being exogenous to the process of new-type urbanization. It does not have a direct causal effect on NTUE. Moreover, lagged DT will help to avoid contemporaneous reverse causality. This measure is thus valid and is referred to as IV1. The second instrument is constructed in a similar manner. It is the interaction between local terrain-slope variation and the one-period lag in DT. In terms of relevance, terrain slope variation reflects the complexity of local topography, which may influence local infrastructure construction costs and thereby increase demand for DT. When interacting with lagged DT, which captures the cumulative effect of past technological development, the resulting variable satisfies the relevance condition. Regarding the exclusion restriction, terrain slope variation is determined by natural geographic characteristics and has no direct causal relationship with NTUE. Lagged DT also helps mitigate reverse causality. This instrument is theoretically appropriate for addressing endogeneity concerns and is denoted as IV2.

The two-stage instrumental variable estimation results are reported in Table 6. Columns (1) and (2), as well as columns (3) and (4), present the two-stage results for IV1 and IV2, respectively. First of all, as shown in columns (1) and (3), the first-stage coefficients of both instrumental variables are statistically significant at the one percent level. Second, columns (2) and (4) show that the coefficient of DT in the second stage is significantly positive at the one percent level, which is consistent with both the significance and the direction of the baseline regression results. Furthermore, the Kleibergen Paap rank LM statistics of both instruments are significant, the Cragg Donald Wald F statistics are 9274.58 and 9768.90, and the Kleibergen Paap rank F statistics are 237.977 and 262.548, respectively. These diagnostic statistics collectively confirm the validity and strength of the instrumental variables. Overall, the results support the positive effect of DT on NTUE.

Table 6

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV approach 2SLS | ||||

| First | Second | First | Second | |

| IV1 | 0.1172*** (0.0076) |

0.0019*** (0.0001) |

||

| IV2 | ||||

| DT | 0.0346*** (0.0066) |

0.0272*** (0.0079) |

||

| Constant | −0.0580*** (0.0190) |

0.2510*** (0.0107) |

−0.0525*** (0.0182) |

0.2520*** (0.0107) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| K-P rk LM | 13.233*** | 14.687*** | ||

| C-D Wald F | 9274.58 | 9768.9 | ||

| K-P rk F | 237.977 | 262.548 | ||

| N | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 |

Two-stage results of instrumental variables.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.3.2 Heckman two-step

Close attention should also be paid to endogeneity associated with sample selection and self-selection. Within this environment, bias can occur when there is a failure of observations to occur some how without randomness, or where cities with greater NTUE tend to adopt DT as a systematic effect which causes self-selection. To mitigate this we also apply a Heckman two-stage adjustment to reconsider the strength of the baseline findings. Table 7 columns (1)–(4) express the findings of the Heckman two-stage estimation. Columns (1) and (3) give the findings of the first stage selection equation since here we take the two variables that we are using as an exclusion restriction through the instrument variable method. Probit model is used to determine a likelihood that the observation fits into sample i.e., whether a region will adopt DT. The positive coefficients are significantly large which determines non-random selection. Column (2) and (4) represent the second stage outcomes when the inverse Mills ratio calculated based on the Mills ratio of the first stage is added. The inverse Mills ratio is not statistically significant in both cases. This is a sign that the probability of sample selection bias impacting significantly on our findings is low and that the positive correlation that exists between DT and NTUE is strong and valid.

Table 7

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heckman two_step | ||||

| First | Second | First | Second | |

| IV1 | 1.7467*** (0.1859) |

|||

| IV2 | 0.0267*** (0.0025) |

|||

| DT | 0.0493*** (0.0098) |

0.0498*** (0.0099) |

||

| Constant | 0.3683*** (0.0958) |

0.4022*** (0.0399) |

0.4549*** (0.0963) |

0.4154*** (0.0393) |

| Mills | 0.0922 (0.0595) |

0.0484 (0.0449) |

||

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 5,076 | 3,484 | 5,076 | 3,484 |

| Adj R2 | 0.0833 | 0.6351 | 0.0957 | 0.6345 |

Heckman two-step results.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.3.3 Omitted variable

Once we have avoided endogeneity issues surrounding reverse causality and sample selection, we also increase the number of controls to help prevent omitted-variable bias and also re-examine the strength of the baseline estimates. We incorporate three additional categories of covariates. Firstly, we account for human capital. Higher human capital can strengthen the effective use of digital tools in urban management and governance, and it can also facilitate R&D activity and the diffusion of innovation, all of which may influence NTUE. Because human capital may be correlated with both DT and NTUE, controlling for it helps reduce estimation bias. We proxy human capital (HC) using the ratio of enrolled students in regular higher-education institutions to the total urban population. Secondly, we control for financial development. Cities with more developed financial systems may be better able to attract DT-related investment and allocate capital more efficiently, which can directly improve NTUE. At the same time, urbanization itself may increase demand for financial services, implying potential simultaneity. We proxy financial development (Finance) by the ratio of outstanding deposits and loans of financial institutions to local GDP. Thirdly, we account for the employment structure. DT may affect NTUE through changes in the composition of employment, as employment reallocation is a salient manifestation of labor mobility during urbanization. To reduce omitted-variable concerns associated with this channel, we include the share of employment in the tertiary sector as a proxy for employment structure (Employment).

Columns (1)–(3) of Table 8 report the results after addressing potential omitted-variable concerns, with human capital, financial development, and employment structure added sequentially as additional controls. Across these specifications, the estimated coefficient on DT remains statistically significant and retains the same sign as in the baseline model. This pattern suggests that omitted-variable bias is unlikely to be a primary driver of the main findings and that the positive effect of DT on NTUE is robust to the inclusion of these additional covariates.

Table 8

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NTUE | |||

| DT | 0.0501*** (0.0100) |

0.0511*** (0.0099) |

0.0498*** (0.0102) |

| HC | −0.4006 (0.6357) |

||

| Finance | −0.0124 (0.0119) |

||

| Employment | 0.0029*** (0.0557) |

||

| Constant | 0.4371*** (0.0418) |

0.4602*** (0.0417) |

0.2465*** (0.0557) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6343 | 0.6349 | 0.6396 |

Results considering omitted variables.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.4 Heterogeneity analysis

The impact of DT on NTUE is very context-dependent and the direction and amount of its effects depend on the development level of a city and the factor endowment structure. The high level of territorial size and disproportionate regional growth in China creates structural cross-city variation in geographic location, historical processes, aperture and economic fundamentals. All these features contribute to the institutional setting and the infrastructural underpinning, in which DT spreads and becomes incorporated. Simultaneously, the new-type urbanization is not too much confined to the concentration of population and its spatial growth; it accentuates the quality development within the ecological limits and highlights people-oriented benefits in their income and structural improvement. In this respect, the environmental circularity, the residents' income levels, and the characteristics of the industrial structures are the critical contextual conditions that define whether, and to what degree, the DT can be converted into urbanization efficiency improvements.

Developing this reasoning, and based on the literature on this topic and the institutional situation in China, we discuss heterogeneity on four dimensions that are closely interconnected but analytically different. Geographic location provides general variation of regional development trends and openness, which helps to identify differences in the baseline conditions supporting DT's spatial diffusion. The environmental circularity shows the degree of green-development base and the degree of pressure of environmental regulation, and therefore, the extent of the ability of DT to lead to higher marginal returns in the form of conservation of energy, reduction of emissions, and the further optimization of resource use. Population income serves as a partial proxy for human-capital endowments and demand upgrading, which can shape the channels through which DT improves labor quality and alters consumption structures. The industrial structure determines the factor-allocation in ways, the potential to absorb the technology which is coupled with the prospect of green transformations, hence conditioning the gains of marginal efficiency in the case where the DT is incorporated into production systems. By systematizing the heterogeneity in these aspects, the study will not only aim to elucidate when and where DT is important, but it will also aim at more systematically discovering alternative pathways of differentiation and boundary conditions that the DT has on NTUE.

4.4.1 Geographical location

The availability of enabling infrastructure and the surrounding institutional environment are critical to the diffusion and successful application of DT. Pronounced macro-level variations between the eastern, central and western regions of China, in terms of geographic location, economic foundations, and openness, define the preconditions for DT adoption and the policy space for leveraging DT to enhance urbanization transformation (Lin and Ma, 2022). In order to test the heterogeneity in terms of location and the general region development trends, we further more subdivide the sample cities to two groups, namely the East-Central group and the West group, based on the regional classification criterion of the National Bureau of Statistics, and provide between-group comparison testing.

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 9 present the heterogeneity results. The estimates indicate that DT exerts a stronger positive effect on NTUE in eastern and central cities than in western cities. This variation is arguably connected to regional disparities in socio-cultural contexts and economic endowments. From a socio-cultural perspective, the eastern coastal area and parts of central China have historically been more exposed to external economic and cultural exchange, which has fostered a more open and inclusive environment. Consequently, the population and companies in these regions can be better prepared to embrace and use new technologies, which offers an easy social group to promote the spread and further implementation of DT. In comparison, in some western regions, the external dissimilarity is more minimal and the cost of adjustment to change related to the institution and notion is more heightened, which may escalate the total expense of adopting and evolving DT (He et al., 2025). In terms of economic-endowment, the cities of the east and center tend to have more basic economic foundations and better developed enterprise ecosystems. They also have a larger number of listed companies and superior quality corporate agents, which increases the market demand and financial power to invest in digital infrastructure and accumulation of DT. In these circumstances, the marginal contribution of DT to NTUE is easier to attain. Comparatively, western cities typically experience limitations regarding the weaker economic base, reduced enterprise digitalization, and less advanced market mechanisms, which may restrict the scale of DT penetration and eliminate the increase in efficiency possibilities of the urbanization process (Chen W. et al., 2025).

Table 9

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTUE | ||||

| East-central | West | High Env | Low Env | |

| DT | 0.0497*** (0.0105) |

0.2340 (0.1778) |

0.0385 (0.0349) |

0.0600*** (0.0050) |

| Constant | 0.4143*** (0.0390) |

0.4131*** (0.0747) |

0.4279*** (0.0473) |

0.4028*** (0.0597) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2,715 | 769 | 1,854 | 1,630 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6338 | 0.6552 | 0.6881 | 0.6069 |

Heterogeneity test I: geography and environment.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.4.2 Environmental cycles

The climate-sustainable potential of DT will be linked to the capability of the environmental bearing of a place and resource circularity. Being a salient requirement in the context of new-type urbanization, a concept of environmental circularity interprets baseline requirements in resource management, waste treatment, and ecological development (Hu et al., 2025), as well as defines the possibility and validity of applying DT to facilitate the development of green and low-carbon. In attempt to analyze heterogeneity linked to environmental endowments, we use in its place the overall utilization rate of general industrial solid waste. We then divided cities into high and low environmental circularity categories by the median of the annual sample, and determined whether the impact of DT on NTUE is different when environmental constraints are strong and weak.

Table 9 in columns (3) and (4) delivers the heterogeneity results of environmental circularity. The estimates suggest that the positive effect of DT on NTUE is statistically stronger in the cities that are characterized by low environmental circularity compared to the cities that have high environmental circularity. Trying to comprehend this pattern in two mutually supplementary angles, one can speak about the development potential and governance pressure. In regards to development potential, low-circularity cities are generally worse-off in terms of their underlying conditions and as such, has more room to improve its efficiency level. In places where DT is penetrating rather less developed fields like environmental regulation and resource allocation, it can produce more apparent incremental benefits, resulting in more comparatively significant short term gains in NTUE levels. Oppositely, cities having a greater environmental circularity are closer to a comparatively mature stage, in which the additional improvement of the NTUE is more related to institutional enhancement and more intense technological modernization, suggesting low marginal returns (Zhan et al., 2025). Regarding the governance pressure, low-circularity cities tend to have a higher number of binding environmental limitations and a higher number of salient governance issues, which can enhance the incentives of local governments to implement DT and enhance implementation endeavors (Du et al., 2023). These cities can experience simultaneous environmental performance and urbanization efficiency gains by increasing the rate of adoption of DT in environmental monitoring, waste management and energy utilization. Compared to high-circularity cities, NTUE will be more apt to be determined by a greater range of structural factors, including industrial composition and population distribution, than modify or weaken the marginal contribution of DT to the overall efficiency outcome.

4.4.3 Population income

The income level of the residents is not only one of the central outcomes measures of the quality of urbanization, but also a vital factor determining the level of human-capital endowments and the organization of consumption demand. Higher income is the key factor of the new-type urbanization, based on people-centered concerns, and generally, it relates to the quality of human capital, increased and more diverse market demand, and more structural upgrade incentives (Zhou et al., 2015). These characteristics, in their turn, will offer more allowing demand base and more fiscal power to implement DT in the delivery of public services, optimization of factor allocation, and industrial change. Based on this rationale, we utilize urban per capita disposable income as an indicator of the income level of cities. We then group cities by the sample median of annual income by high and low, and test the hypothesis that the effect of DT on NTUE varies systematically between high and low-income groups.

Table 10 under section columns (1) and (2) file the heterogeneity by level of income. The estimates have shown that the high-income cities are largely affected by DT compared to low-income cities in terms of NTUE. It is possible to make two different suppositions of this pattern. To begin with, regarding factor endowment and development conditions, high-income cities generally have a larger capacity of attracting labor and concentrating human capital, which provides a broader range of possibilities to embed DT in terms of job matching, industrial upgrade, and delivering public services (Özden et al., 2018). An increase in income means better fiscal capabilities and expanded tax base to support the investment in digital infrastructure and institutional innovation, which increases the marginal contribution of DT to NTUE. Secondly, with respect to preferences and governance mechanisms, residents in high-income cities tend to demand higher-quality public services, greener products, and improved environmental conditions. These preferences can encourage firms to increase investment in environmental protection and technology upgrading, and they may also lower social resistance when governments implement digital-governance and green-urbanization policies. In this way, demand-side pressures and governance responses can jointly strengthen the transmission mechanisms through which DT improves NTUE (Li Z. et al., 2024). By comparison, the cities with lower incomes are more likely to be dependent on the benefits of low costs of labor as they can bring labor-intensive activities and even more pollution-intensive ones. That can extend a factor-based and comprehensive developmental path, destabilizing indigenous demand of digital transformation. Moreover, diminished income may limit the willingness of the residents and their ability to afford digital forms of public services and green products, which will not support the implementation of DT at both the demand-side and market in general.

Table 10

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTUE | ||||

| High income | Low income | High-level | Low-level | |

| DT | 0.0527*** (0.0090) |

−0.1414 (0.1045) |

0.0514*** (0.0093) |

−0.0749 (0.0515) |

| Constant | 0.4276*** (0.0727) |

0.4323*** (0.0363) |

0.4160*** (0.0613) |

0.4241*** (0.0347) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1,746 | 1,738 | 1,746 | 1,738 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6573 | 0.6300 | 0.6727 | 0.6555 |

Heterogeneity test II: income and structure.

Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

4.4.4 Industrial structure

Industrial structure constitutes a central carrier of factor allocation and technological capability, and its degree of modernization is closely tied to a city's capacity to absorb and transform DT. Upgrading the industrial structure typically reflects a shift from factor-driven expansion toward innovation- and service-led growth (Guan et al., 2022). Such a transition not only reallocates capital and labor across sectors, but also strengthens the scope for inter-industry technological integration and enlarges, to some extent, the institutional and market space for green and low-carbon development. Together, these changes form the structural basis through which DT can support new-type urbanization. Building on this logic, we construct an indicator of industrial-structure advancement and divide cities into high-level and low-level groups using the annual sample median. We then examine whether DT's effect on NTUE differs systematically across stages of industrial-structure development.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 10 report the heterogeneity results by industrial-structure advancement. The estimates show that DT has a significantly positive effect on NTUE in the high-level group, whereas the corresponding coefficient in the low-level group is negative but statistically insignificant. This difference can indicate that an improved industrial apparatus can provide a more accommodative environment to operate in by the institutional and market types of channels under which DT operates, due in part to its transfer of resource allocation and labor absorption benefits. To be more precise, industrial upgrading is a changing process of a rather low-productivity agricultural society to a higher-productivity non-agricultural society, in other words, manufacturing and service industries, where the factors are redistributed in favor of more productive industries (Li et al., 2025). The result of such reallocation makes the application scenarios more rich and more varied in the demand base of DT that will reinforce the role of DT in NTUE. Furthermore, as modern producer services are being expanded, further upgrading increases the need of working labor in medium and high skills (Shi, 2021). During rural-to-urban migration, DT can reduce job-search and matching frictions and improve the efficiency of training and reemployment, facilitating the absorption of migrating workers into the urban industrial system. These dynamics can enhance the quality dimension of population urbanization and, by extension, overall NTUE. Taken together, cities with more advanced industrial structures appear to realize stronger DT effects on economic upgrading, factor-allocation efficiency, and green transformation, which jointly support improvements in NTUE.

4.5 Mechanism analysis

The intermediate channels through which DT affects NTUE from the government and market perspectives have been motivated in the introduction and formalized in the hypotheses. For the government-behavior channel, we examine government digital attention (Digital) and fiscal intervention (Intervention). Government digital attention is proxied by the frequency of DT-related keywords in government annual reports, while fiscal intervention is measured as the ratio of public fiscal expenditure to GDP. For the market-behavior channel, we consider producer-service development (Produ_service) and the degree of labor-market marketization (Marketization), proxied by the number of newly established producer-service firms and the share of employment in private and self-employed units in total urban employment, respectively. The corresponding estimation results are reported in Table 11.

Table 11

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | Market | |||

| Digital | Intervention | Produ_service | Marketization | |

| DT | 0.5610* (0.3115) |

−0.0035*** (0.0010) |

0.7583* (0.4042) |

−0.0098** (0.0045) |

| Constant | 9.4243*** (1.3600) |

0.1653*** (0.0096) |

2.1548*** (0.5162) |

0.5348*** (0.0318) |

| Control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Individual/year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 | 3,484 |

| Adj R2 | 0.6115 | 0.8545 | 0.6244 | 0.6311 |

Mediating mechanisms test: government behavior and market behavior.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.1, robust standard errors in parentheses.