Abstract

Introduction:

Nigeria's rapidly urbanizing landscape faces persistent governance, infrastructure, and energy challenges that undermine sustainable city development. Bureaucratic inefficiencies, corruption, and unreliable energy systems continue to constrain urban service delivery and citizen welfare. This study investigates how Artificial Intelligence (AI), digitalization, and Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) can transform urban public service systems to promote efficiency, transparency, and inclusive governance.

Methods:

Anchored in a mixed-methods design, the study gathered data from federal, state, and municipal institutions, yielding 642 valid responses, alongside 35 key informant interviews and six focus groups across major Nigerian cities. Quantitative analyses measured adoption levels and relationships among technology integration variables, while qualitative insights illuminated socio-technical barriers and enablers influencing innovation readiness.

Results:

Findings reveal moderate adoption of AI and RETs (mean scores of 3.02 and 3.17, respectively), but low adoption of blockchain technologies (mean score of 2.64). Barriers such as weak digital literacy, inadequate energy infrastructure, limited regulatory frameworks, and inconsistent political commitment significantly hinder the advancement of smart governance.

Discussion:

The study introduces the Integrated Smart Governance Transformation (ISGT) Model, which integrates governance reform, technology deployment, and capacity building to address these systemic constraints. The model provides a strategic pathway for linking digitalization and renewable energy within a participatory governance structure that enhances accountability, service efficiency, and citizen engagement at the urban level. The ISGT model evolves into the Framework for Integrating Renewable Energy Solutions and Technological Innovations for the Digital Transformation of Public Service (FIREs-TIDTPS), which operationalizes technology adoption and governance reform through regulatory support, inclusive participation, and phased implementation. By embedding renewable energy systems within digital governance infrastructures, the framework advances energy-secure, transparent, and citizen-centered urban governance. The study concludes that integrating AI-driven digital systems and renewable energy adoption can enable African cities, particularly in Nigeria, to overcome structural and governance deficits while accelerating progress toward SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). This interdisciplinary contribution offers both theoretical insights and practical strategies for achieving smart, sustainable, and inclusive cities in the Global South.

Introduction

Rapid urbanization in the Global South is intensifying pressures on infrastructure, governance, and energy systems, making sustainable smart city development both urgent and complex. In Nigeria, systemic governance failures, infrastructural deficits, and chronic energy insecurity undermine efforts to modernize public service delivery and improve citizen welfare (Bello et al., 2024; Adeshina et al., 2024). Contemporary scholarship emphasizes that sustainable smart cities require holistic, context-sensitive strategies that integrate infrastructure, environmental sustainability, effective governance, social inclusion, and economic innovation rather than narrowly technocentric solutions (Bello et al., 2024; Das, 2024; Ahad et al., 2020).

Smart governance defined as the strategic application of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), and blockchain to transform public administration has emerged as a critical driver of transparent, efficient, and citizen-centric institutions (Kaponda, 2025; John et al., 2025; Matei and Coco?atu, 2024). Reviews show that AI-enabled systems can significantly enhance operational efficiency, energy optimization, and participatory planning, but their benefits are contingent on robust governance, ethical frameworks, and inclusive digital infrastructure (Almulhim, 2025; John et al., 2025; Ahad et al., 2020). Parallel research highlights that renewable energy and digitalization together can accelerate low-carbon, resilient urban transitions when embedded in strong policy and regulatory environments (Alamry and Al-Jashaami, 2024; Li et al., 2025; Nwaiwu, 2021; Zhang et al., 2023).

These technologies can enable data-driven decision-making, real-time monitoring, and adaptive service delivery, which are critical for addressing Nigeria's energy and infrastructure challenges (Okpala and Nzeanorue, 2024; Matei and Coco?atu, 2024). However, scholars caution that successful implementation depends on robust digital infrastructure, reliable connectivity, effective regulatory frameworks, and sustained capacity building within public institutions (Aghimien et al., 2020; Nkwunonwo et al., 2022). Nigeria, Africa's most populous country with over 220 million citizens, faces entrenched challenges in its public service delivery system. Long-standing systemic inefficiencies—including bureaucratic inertia, endemic corruption, and fractured institutional coordination—have stifled socio-economic development and eroded citizen trust (Idike et al., 2019; Adewumi and Abasilim, 2024; Haesevoets et al., 2024; Egba et al., 2025). Recent digital reforms such as the Integrated Personnel and Payroll Information System (IPPIS) and the Treasury Single Account introduced digital tools to enhance financial management and accountability, yet their impact has remained muted due to infrastructural deficits, political interference, and cultural resistance (Asogwa, 2013; Onwuegbuna et al., 2024; International Renewable Energy Agency, 2023). Empirical studies show that despite these platforms, public trust remains fragile and service delivery inconsistent.

A critical, but often overlooked, factor undermining Nigeria's digital governance potential is its severe and persistent energy deficit. The International Energy Agency (2024) estimates that over 85 million Nigerians lack reliable electricity access, especially in rural and underserved urban areas, forcing reliance on costly and polluting diesel generators to sustain government operations (Ekechukwu and Eziefula, 2025; Ekechukwu et al., 2024). This energy gap is not only a technical constraint but also a deeply political and socio-economic challenge that affects the adoption and performance of digital platforms crucial for service modernization (Adebanji et al., 2022). Emerging technologies such as Maxwell Chikumbutso's microsonic energy devices (MSEDs) have been presented as novel opportunities to leapfrog energy infrastructure deficits by enabling resilient, off-grid power for public institutions and digital governance nodes (Africa Global News, 2025; Obuseh et al., 2025; PRNigeria, 2025). Disruptive digital and renewable-energy solutions remain promising but require empirical validation, supportive regulation, and integration into coherent transition strategies to yield sustainable benefits (Nwaiwu, 2021; Min and Haile, 2021).

Within this context, the paper adopts a multidimensional conceptual framing that positions smart governance as the primary analytical construct, supported by two critical enabling subsystems: digital transformation (driven by AI and blockchain) and energy transition (underpinned by renewable energy technologies, RETs). Unlike previous technocentric approaches that treat IT infrastructure in isolation, this hierarchy acknowledges that technological tools can only thrive within a robust governance framework supported by reliable, sustainable power. Renewable energy is therefore theoretically linked to governance outcomes through its role in ensuring system reliability, operational continuity, and institutional resilience. Stable energy infrastructure underpins digital platforms, data systems, and AI-enabled decision tools, thereby enhancing administrative efficiency, transparency, and service delivery. By explicitly theorizing this governance–energy nexus, the study moves beyond modular IT assessments toward a systemic evaluation of innovation readiness in the Nigerian public sector and contributes to integrative models of smart urban governance and public value creation.

Globally, countries such as Estonia and Singapore exemplify how harnessing artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and integrated digital infrastructures can resolve governance inefficiencies and promote transparency (Miskiewicz, 2022; Kaiser et al., 2024). These nations have achieved near-complete digital access to public services, automating processes and enhancing citizen engagement to build resilient, adaptive institutions. Nigeria's stagnant progress reflects broader structural obstacles: limited AI adoption, unreliable grid power necessitating costly and polluting diesel generators, and weak infrastructural foundations (Adebanji et al., 2022). These impediments not only constrain Nigeria's development but also jeopardize attainment of SDGs, particularly SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). The socio-technical transition toward smart governance requires nuanced consideration of political economy factors, including vested interests, institutional inertia, and hierarchical public service cultures that often resist disruptive innovations (Auld et al., 2022; Shenkoya, 2024). Research underscores the urgent need for multi-level governance reforms incorporating ethical AI frameworks, robust citizen participation mechanisms, and sustainable renewable energy integration to overcome these challenges and foster trust, equity, and accountability (Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi, 2024; Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024). Notably, emerging technologies such as Maxwell Chikumbutso's microsonic energy devices (MSEDs) present novel opportunities for leapfrogging energy infrastructure deficits, potentially enabling resilient, off-grid power to rural public institutions and digital governance nodes (Africa Global News, 2025; Obuseh et al., 2025). While promising, such disruptive innovations require thorough empirical validation, regulatory preparedness, and integration within broader renewable energy strategies to realize sustainable benefits (PRNigeria, 2025).

In Nigeria, abundant renewable resources coexist with persistent electricity shortages caused by weak institutions, inadequate investment, and policy fragmentation, constraining both digital transformation and sustainable urban development (Nwaiwu, 2021; Adeshina et al., 2024). Studies on digitalising African energy systems reveal early-stage adoption of smart grids and blockchain, and a persistent disconnect between innovative pilots and enabling regulatory frameworks (Nwaiwu, 2021). Evidence from developing countries further underscores that synchronized governance reforms, distributed renewables, and data-driven management can substantially reduce emissions while improving resilience and equity (Islam and Islam, 2025; Erifeta, 2025; Alamry and Al-Jashaami, 2024). To address these systemic constraints, the study introduces the Integrated Smart Governance Transformation (ISGT) Model, which integrates governance reform, technology deployment, and capacity building. The model provides a strategic pathway for linking digitalization and renewable energy within a participatory governance structure that enhances accountability, service efficiency, and citizen engagement at the urban level. The ISGT model further evolves into the Framework for Integrating Renewable Energy Solutions and Technological Innovations for the Digital Transformation of Public Service (FIREs-TIDTPS), which operationalizes technology adoption and governance reform through regulatory support, inclusive participation, and phased implementation. By embedding renewable energy systems within digital governance infrastructures, the framework advances energy-secure, transparent, and citizen-centered urban governance.

Against this backdrop, smart urban governance in Nigeria must be conceptualized as a governance–energy–digital nexus: AI-driven digitalization and renewable energy technologies function as enabling infrastructures whose transformative potential depends on institutional capacity, regulatory coherence, and inclusive participation. Integrating these dimensions offers a pathway for Nigerian cities to advance Sustainable Development Goals 7, 11, and 16 through energy-secure, transparent, and citizen-centered public service systems.

This research is guided by three primary objectives: (i) to evaluate the current level of AI, blockchain, and RET adoption across Nigerian public institutions; (ii) to identify the socio-technical and political-economy barriers hindering this integration; and (iii) to empirically validate the proposed governance–energy–digital transformation framework as a pathway for achieving smart, sustainable, and inclusive urban governance in Nigeria and the wider Global South.

Conceptual and analytical framework

Digital governance and artificial intelligence in public service reform

Public administration models have evolved significantly, reflecting transitions from classical bureaucratic arrangements to digitally enabled governance frameworks. As Ukeje et al. (2019) argue, bureaucracy is an “indecisive” and frequently contested concept, whose hierarchical and rule-bound nature is often simplistically criticized for rigidity and inefficiency, particularly within reform narratives in developing administrative systems. Early administrative models like Old Public Administration (OPA) are characterized by hierarchical and rule-bound operations, which Weber observed as “an iron cage” limiting flexibility and innovation (Rogers, 2003; p. 89). Rogers (2003, p. 97) stresses that “the diffusion of innovations in public administration has historically been slowed by entrenched bureaucratic inertia”. Public sector reforms across Africa have increasingly sought to embed results-oriented management and citizen-centric service delivery through digitalization and NPM-influenced governance models (Mbae et al., 2025; Egba et al., 2025). However, Ndukwe et al. (2021) observe that “reforms have largely failed to overcome bureaucratic resistance, weak institutions, and lack of political will, resulting in limited transformation.”

Digital Era Governance (DEG) represents a paradigm shift, leveraging ICT and AI to build transparent, efficient, and participatory institutions. Kaiser et al. (2024, p. 220) argue that DEG “integrates technology into governance to enable real-time data-driven decision-making, inclusivity, and accountability”. A recent milestone in Nigeria exemplifying DEG is the rollout of the Service-Wise GPT, an AI-powered assistant that “automates complex policy referencing, improving accuracy and speed in civil service task execution” (Anyanwu, 2025; p. 2). In her presentation, Walson-Jack (2025, as cited in Anyanwu, 2025) notes that “the integration of AI such as GPT into public service dramatically reduces bureaucratic bottlenecks and enables efficiency gains hitherto impossible” (Anyanwu, 2025, p. 3). However, the transition to DEG is “not merely technological but cultural and institutional, requiring paradigm shifts in governance approaches” (Luna et al., 2024; p. 101). Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi (2024, p. 3) emphasize the triadic nexus of “humans, machines, and organizations,” urging that governance models “must carefully balance automation benefits with human discretion and ethical oversight”.

Nigeria's digital governance ambitions are constrained by structural and socio-political challenges. Odiche and Amodu (2024, p. 150) highlight that “while digital technologies offer transformational potential, incomplete infrastructural development and significant digital literacy gaps impede progress”. They emphasize that “policymakers often overlook inclusivity, risking marginalization of rural and disadvantaged populations” (p. 153). Onwuegbuna et al. (2024, p. 202) identify bureaucratic rigidity as a critical barrier: “Public servants' bureaucratic resistance to digital adoption stems from job insecurity fears and lack of adequate ICT training”. These human factors “reduce the pace and quality of digital integration in Nigerian public institutions” (p. 203). Poor inter-agency coordination has been identified as a critical institutional constraint, as Kasiwi et al. (2025) observe that such fragmentation produces disjointed digital strategies, thereby limiting interoperability and constraining the scalability of e-governance systems. Wirtz et al. (2015, p. 365) also emphasized that “security concerns and infrastructural deficits remain key barriers to e-government uptake, which resonate profoundly in Nigeria's volatile context”. Furthermore, Punch Newspapers (2025, para. 10) reports growing cybersecurity threats that “challenge the integrity of government platforms, necessitating strengthened data protection policies and capacity building”. Growing cybersecurity threats undermine the integrity of Nigerian government platforms, highlighting the need for stronger data protection frameworks and sustained capacity-building for public institutions (Ikuero, 2022; Adebanjo et al., 2024).

Crucially, this study argues that the success of Digital Era Governance (DEG) in Nigeria is fundamentally predicated on the resolution of the country's chronic energy deficit. We conceptualize the “Governance–Energy Nexus” as a foundational dependency where energy reliability serves as the enabling substrate for institutional transparency and administrative efficiency. Without a stable power supply, the “immutable” nature of blockchain and the real-time processing of AI become functionally intermittent, thereby eroding the very citizen trust these technologies are meant to build. By positioning Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) as a core governance infrastructure rather than a secondary utility, the FIREs-TIDTPS framework acknowledges that energy security is a prerequisite for digital sovereignty. This perspective shifts the discourse from a technocentric focus on software to a socio-technical focus on “operational continuity.” In this model, RETs provide the resilient energy backbone necessary to sustain digital platforms in underserved urban and rural areas, ensuring that the benefits of smart governance are not limited by the failures of the national grid. Thus, the integration of clean energy is theorized here as an active driver of governance reform, providing the literal power needed to sustain a transparent and accountable public service. The digital divide remains stark; World Bank (2024, p. 4) data reveals that “only 42% of Nigeria's population have internet access, with urban centers and higher-income groups disproportionately represented”. This gap threatens to widen inequalities unless digital governance frameworks incorporate targeted inclusion strategies (Odiche and Amodu, 2024; p. 159).

Blockchain is increasingly recognized as a powerful tool in combating corruption and inefficiency in governance by creating “immutable transaction records accessible by all relevant stakeholders” (Boumaiza and Maher, 2024; p. 110). Onukwulu et al. (2025, p. 700) highlight how blockchain in Nigerian procurement processes “has led to drastic reductions in fraud occurrences and increased public confidence”. They emphasize “Blockchain's cryptographic security and decentralized design allows for transparency while safeguarding data integrity, a crucial feature for Nigerian governance systems suffering from opacity” (p. 705). Recent studies highlight that blockchain-based public service platforms, especially when integrated with automated data analytics, can significantly enhance traceability, streamline compliance through smart contracts, and help identify fraud and corruption risks in areas such as public procurement, welfare payments, and tax administration. This positions blockchain as a powerful driver of e-government reform (Wamba et al., 2024; Kassen, 2022, 2024; Hyvärinen et al., 2017). However, the literature consistently identifies regulatory ambiguities, underdeveloped legal frameworks, and insufficient institutional capacity as major barriers to adoption. To realize the anti-corruption and efficiency benefits of blockchain in public administration, it is crucial to establish clearer legal guidelines, effective governance models, and ongoing capacity-building initiatives (Cagigas et al., 2021; Warkentin and Orgeron, 2020). Adebanji et al. (2022, p. 21) caution that despite its promise, blockchain's implementation requires “significant infrastructural investments and digital literacy enhancements”.

Nigeria's public service has shifted from rigid, hierarchical Old Public Administration models toward Digital Era Governance (DEG), driven by ICT, AI, and blockchain innovations aimed at improving transparency, efficiency, and citizen participation. While AI tools like Service-Wise GPT have reduced bureaucratic bottlenecks, progress is hampered by infrastructural gaps, low digital literacy, bureaucratic resistance, poor inter-agency coordination, and cybersecurity threats, with internet access limited to 42% of the population. Blockchain shows strong potential in enhancing procurement transparency and reducing corruption, yet its adoption is constrained by unclear regulations, high infrastructure costs, and capacity deficits, making inclusive policy frameworks and targeted investment essential for sustainable digital transformation.

Global examples of smart governance: lessons from Estonia, Singapore, and Rwanda for Nigeria's unique context

Estonia, Singapore, and Rwanda offer instructive models for digital governance, demonstrating how AI, digitalization, and renewable energy technologies can transform public service delivery and institutional transparency. While these countries provide invaluable lessons, Nigeria's unique governance environment necessitates contextual adaptation rather than direct replication (Kaiser et al., 2024; Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024). Estonia, a pioneer in e-government, established a highly interconnected digital ecosystem via its X-Road platform, enabling seamless interoperability across government databases, secure citizen identification, and transparent public transactions (Kaiser et al., 2024; Miskiewicz, 2022). With early adoption of blockchain ensuring public record integrity and digital literacy campaigns fostering citizen engagement, over 99% of government services are available online (Kaiser et al., 2024).

Singapore's Smart Nation programme exemplifies a largely top-down digital governance model that deploys AI-driven analytics and integrated platforms for real-time management of urban services, while coupling innovation with legal and governance frameworks for data protection (Das and Kwek, 2024; Engin and Treleaven, 2019). The integration of AI with digital platforms enhances urban management, health services, and public feedback systems. Singapore couples technological innovation with robust legal frameworks enforcing data privacy and emphasizes digital skills training within the civil service (Lim et al., 2020). Rwanda is a rapidly emerging exemplar, deploying digital public services and renewable energy to bridge infrastructural gaps (Miskiewicz, 2022). Governments and health systems are increasingly implementing AI-enabled mobile and telehealth platforms to enhance healthcare delivery and improve public service performance. Simultaneously, solar-powered infrastructure is utilized to operate AI units, kiosks, and other digital health nodes in rural and underserved areas where grid electricity is unreliable (Batista, 2025; Balakrishnan et al., 2025; Teklemariam et al., 2025; Kumar et al., 2025). Nnadi et al. (2025) highlight the potential of integrating solar, wind, hydro, and biomass with fossil fuels in Nigeria to reduce transmission losses and improve rural energy access. They note significant challenges, such as high initial costs, regulatory hurdles, and insufficient technical expertise. Additionally, policy inconsistencies and a weak regulatory framework hinder progress, exemplified by the ineffective Electric Power Sector Reform Act of 2005 in facilitating renewable energy integration (p. 12).

However, Nigeria's federal and decentralized governance structure contrasts sharply with the unitary systems in Estonia and Rwanda, requiring a phased, multi-tiered approach tailored to institutional capacities at all levels (Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024). Infrastructural and digital divides are more pronounced in Nigeria, with only 42% internet access, necessitating targeted interventions for electricity, connectivity, and digital literacy (Odiche and Amodu, 2024; World Bank, 2024). Political economy dynamics and bureaucratic resistance also present barriers, demanding robust transparency measures and political will (Auld et al., 2022; Shenkoya, 2024). Resource constraints, especially power shortages, impede digital platform operations. Unlike Singapore and Estonia, Nigeria requires integrating renewable energy technologies (RETs), including innovative options like microsonic energy devices (MSEDs), for resilient, off-grid deployments (Adebanji et al., 2023; Africa Global News, 2025). Citizen engagement frameworks in Nigeria require emphasis to foster inclusiveness and trust, accommodating diverse linguistic, cultural, and socio-economic groups (Haesevoets et al., 2024). South Africa is advancing smart/digitalised grid and renewable energy integration initiatives, including distributed generation, smart inverters and RE-specific grid codes to improve reliability and power quality, while planning large-scale renewable additions to support its strained grid (Dzobo et al., 2024; Mbungu et al., 2020; Thopil et al., 2018).

Nigeria's chronic energy deficit undermines digital governance ambitions, as the reliability of AI and blockchain platforms is precarious without sustainable energy solutions (International Energy Agency, 2024). Solar PV adoption has emerged as a viable renewable intervention, particularly in rural areas (Adebanji et al., 2023; Champion Newspapers, 2025). Combining solar with wind or biomass enhances system reliability, though implementation faces financing and regulatory delays (Ekpotu et al., 2024; Adebanji et al., 2023). MSEDs offer potential to leapfrog energy deficits, but require rigorous validation and integration with governance technologies (Africa Global News, 2025; Obuseh et al., 2025). Thus, Nigeria should pursue a hybridized smart governance model, leveraging lessons from Estonia, Singapore and Rwanda, while innovating adaptive strategies to navigate its unique complexities (Kaiser et al., 2024; Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024).

Empirical and conceptual studies increasingly support the establishment of a pragmatic and dynamic ISGT model that aligns with international AI ethics frameworks, such as the European Union (EU) AI Act and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recommendations. Systematic reviews and cross-jurisdictional analyses show that effective AI governance requires moving beyond high-level principles to actionable, context-specific frameworks that embed ethical values like transparency, accountability, fairness, privacy, and inclusivity into both policy and practice (Ashok et al., 2022; Celsi and Zomaya, 2025; Ahmad et al., 2024; Ukeje et al., 2025). For example, a global review of AI ethics frameworks highlights the need for ontological models that address digital ethics across cognitive, information, and governance domains, echoing the EU AI Act's risk-based, rights-focused approach and UNESCO's emphasis on human rights and social justice (Ashok et al., 2022; Celsi and Zomaya, 2025; Erman and Furendal, 2022).

Nigeria's National Urban Development Policy (NUDP) and emerging Smart City Initiatives provide a strategic context for implementing the ISGT and FIREs-TIDTPS models. The NUDP emphasizes the creation of inclusive, resilient, and environmentally sustainable cities through integrated governance, digital infrastructure, and energy efficiency. Complementing this, Nigeria's Smart City Framework piloted in Lagos, Abuja, and Enugu promotes data-driven urban management, renewable energy adoption, and citizen-centered e-services. These works emphasize the importance of infrastructure integration, environmental sustainability, efficient governance, and social inclusivity as key drivers for sustainable smart city initiatives (Bello et al., 2024; Zubairu, 2020; Unegbu et al., 2024). Nigeria's Smart City Initiatives, including pilot projects in Lagos and Abuja, are documented as efforts to promote data-driven urban management, renewable energy adoption, and citizen-centered e-services. These initiatives rely heavily on ICT, geospatial technologies, and stakeholder engagement to transform urban centers into more efficient and responsive cities (Bandauko and Arku, 2022; Agboola et al., 2023). These policies align with the study's focus on AI-enabled governance, decentralized renewable systems, and participatory digital platforms, reinforcing national priorities for sustainable urban transformation. This alignment is consistent with SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities and SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy.

Transforming public service infrastructure: microsonic energy and the future of renewable technologies in Nigeria

Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) are vital for improving Nigeria's public service infrastructure, particularly in light of persistent energy challenges such as grid unreliability and disparities in energy access. This is especially pronounced in rural and peri-urban areas where RETs provide decentralized, resilient power sources essential for digital governance tools and public amenities. Among these technologies, microsonic energy devices (MSEDs) offer a groundbreaking approach to energy generation, potentially transforming how energy is accessed and utilized in Nigeria.

MSEDs, pioneered by Zimbabwean inventor Maxwell Chikumbutso, harness ambient radio-frequency (RF) signals present in the environment, converting these electromagnetic waves into usable electrical energy. This technology operates without the need for batteries, fuel, or charging infrastructure, making it a compelling solution for energy-deficit regions. As highlighted by Africa Global News (2025), Chikumbutso's Renewable-Energy Vehicle operates solely on ambient RF energy, representing a fundamentally new source of clean energy that could revolutionize transportation and energy generation.

The microsonic device circumvents the intermittency issues associated with conventional renewable sources like solar and wind by tapping into a consistent energy reservoir, including waves generated by celestial bodies (Uplifting Africa, 2025). Its core technology comprises Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors (MOSFETs) and custom transformers, which amplify and convert low-voltage signals into usable electricity. Chikumbutso likens this innovation to Nikola Tesla's early concepts of wireless power transmission, stating that it actualizes Tesla's theories on frequency transformers (Waking Times, 2021). Empirical evaluations claim energy output beyond battery capacity, yet scientific scrutiny remains skeptical, citing apparent violations of thermodynamics and classifying GPM (Greener Power Machine) as a “perpetual motion” device (Gamble, 2020).

Independent tests documented in the documentary Gamble (2020) have corroborated claims about the MSED's capabilities, showing it powered a welding machine longer than expected, indicating it draws energy from an unknown source. Gamble (2020) states, “We observed the machine not only outlasted the expected battery life, but the batteries were still fully charged, proving that the device is being powered from an unknown energy source,” showcasing its capability to capture and utilize ambient RF energy. However, the scientific community remains divided. Critics question the device's ability to defy thermodynamic laws, while supporters view it as a breakthrough in harnessing underutilized physical phenomena (PRNigeria, 2025). Rigorous peer-reviewed testing is crucial for broader acceptance of this technology.

Environmental, technological, and legal challenges are particularly prominent in Nigeria, and addressing basic needs such as poverty reduction is seen as a prerequisite for meaningful smart city transformation (Aghimien et al., 2020; Nkwunonwo et al., 2022). In Nigeria, where over 85 million people lack reliable electricity, MSEDs present a compelling solution to the country's chronic energy issues (International Energy Agency, 2024). Conventional renewable technologies face significant infrastructural and financial barriers, making decentralized innovations particularly attractive for accelerating rural electrification and supporting digital governance ecosystems (Obuseh et al., 2025). The off-grid, battery-free operation of MSEDs aligns well with the needs of underserved rural communities and public sector facilities, enabling them to operate independently of the unreliable grid.

Integrating microsonic devices into Nigeria's renewable energy strategy complements national efforts to diversify energy sources. Innovation-driven renewable energy strategies and digitalization are central to sustainable and inclusive energy transitions in Nigeria (Nwaiwu, 2021; Okafor et al., 2025), while Nigeria's Energy Transition Plan emphasizes diversified, locally appropriate renewable energy pathways supported by targeted policy and infrastructure upgrades (Ekpotu et al., 2024). Existing solar PV and hybrid systems have already proven to be modular and scalable, capable of supporting the ICT infrastructures necessary for Digital Era Governance (DEG). Although there is strong recognition of solar energy's potential, infrastructural and financial constraints continue to limit its broader adoption (Adebanji et al., 2023). Modular solar, hybrid solutions, and the emerging microsonic devices offer scalable options adaptable to various institutional sizes and geographic contexts. This adaptability allows for tailored deployments that meet specific service demands, supporting initiatives such as the EU-funded Nigeria Solar for Health Program (Champion Newspapers, 2025).

Theoretical framework

The theoretical foundation of this study is anchored in the Diffusion of Innovations (DoI) Theory, the Resource-Based View, and integrates Political Economy perspectives to reflect systemic realities shaping governance transformation. Rogers's DoI Theory is pivotal for understanding how new ideas and technologies spread within social systems. It identifies five core attributes that influence innovation adoption: relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability. In Nigeria, for AI and blockchain technologies to gain traction, they must clearly demonstrate advantages over traditional methods, such as enhanced efficiency and transparency (Anyanwu, 2025). Compatibility assesses how well the innovation aligns with existing values and needs. Nigeria's bureaucratic culture and complex governance structures significantly impact the adoption of digital governance solutions (Onwuegbuna et al., 2024; Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024).

Complexity involves the perceived difficulty of using the innovation. In Nigeria, low digital literacy levels present a substantial barrier, necessitating targeted capacity-building efforts (Odiche and Amodu, 2024). Pilot programs for AI and renewable energy have been effective in Nigeria, allowing for gradual acceptance by minimizing perceived risks (Obuseh et al., 2025). Additionally, early successes in transparency and efficiency can help overcome skepticism, promoting broader adoption (Shenkoya, 2024). Applying these attributes, the DoI Theory elucidates the partial and uneven adoption patterns in Nigeria's public sector. Studies indicate that adoption accelerates with clear relative advantages and observable successes but stalls when complexity and cultural incompatibility are significant barriers (Miskiewicz, 2022; Ashok et al., 2022).

Barney's Resource-Based View (RBV) complements this analysis by focusing on internal organizational capabilities and resources as key drivers of sustainable competitive advantage. In Nigeria's public service, essential resources include technological infrastructure, skilled human capital, regulatory frameworks, and energy security, all critical for effective technology deployment (Adebanji et al., 2023; Nwosu et al., 2024). The RBV highlights disparities in institutional resources across Nigeria's different governance tiers, where variations in infrastructure and capacity impact the scalability of digital initiatives (Onukwulu et al., 2025). The ability to attract and develop skilled personnel who can manage complex technologies is vital for distinguishing high-performing institutions (Adewumi and Abasilim, 2024). Furthermore, integrating renewable energy solutions can mitigate Nigeria's energy crises while enhancing institutional resilience (Ekpotu et al., 2024; Africa Global News, 2025). Thus, RBV underscores the need for policy interventions that strengthen these critical resources.

While DoI and RBV provide valuable insights, they often overlook entrenched power dynamics and institutional inertia affecting governance transformations. Political economy analyses reveal that resistance from established actors, whose interests may be threatened by new technologies, significantly shapes policy formulation and implementation (Auld et al., 2022). Bureaucratic resistance and political patronage can undermine efforts to adopt innovative technologies, highlighting the need for strategic change management that considers these systemic realities in governance transformation efforts.

Empirical research strongly supports the need for integrated, dynamic AI-ethical compliance frameworks, citizen engagement, capacity building, and a political economy lens in digital governance. Studies highlight that embedding ethical safeguards such as transparency, accountability, privacy, and inclusivity into AI deployment is essential for public trust and democratic legitimacy. For example, global and Indian stakeholder surveys reveal widespread concerns about algorithmic bias, data privacy, and the need for human oversight, leading to recommendations for mandatory transparency protocols, ethics-by-design frameworks, and continuous capacity-building initiatives in public administration (Sharma, 2025; Ashok et al., 2022; Saura et al., 2022). Strategic frameworks in both public and corporate governance emphasize the establishment of AI ethics committees, adoption of ethical guidelines, and ongoing training to ensure responsible, inclusive, and transparent AI use (Sharma et al., 2025; Kandeel et al., 2024; Ashok et al., 2022).

Studies reviews also show that two-way citizen-government interaction is critical for legitimacy, with governments using AI to improve service delivery and engagement, but facing privacy and behavioral data concerns that require robust regulatory and ethical design (Saura et al., 2022; Shouli et al., 2025). Capacity building is repeatedly identified as a key enabler, as digital literacy gaps among both public servants and citizens can undermine the effectiveness and fairness of AI-driven governance (Sharma, 2025; Ashok et al., 2022).

Importantly, the political economy of reform is crucial: research finds that power dynamics, vested interests, and institutional inertia can shape the adoption and ethical governance of AI, with private and public actors influencing standards, regulatory responses, and the pace of reform (Auld et al., 2022; Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024). Addressing these dynamics through inclusive, transparent, and adaptive governance structures is necessary for sustainable, ethical digital transformation (Sharma, 2025; Adeniyi and Okusi, 2024). Empirical studies highlight that AI adoption enhances accuracy, reduces human bias, and accelerates decision cycles in public service delivery (Thanyawatpornkul, 2024; Turyasingura et al., 2024).

Citizen-centric governance and ethical oversight are empirically shown to enhance trust and legitimacy. Studies on citizen-centric AI and e-governance in India and elsewhere demonstrate that ethical alignment, participatory design, and two-way engagement mechanisms are critical for public acceptance and effective service delivery (Deshmukh et al., 2024; Swapnil et al., 2024; Ahmad et al., 2024). These findings map directly onto Diffusion of Innovations Theory (DoI): observability and trialability are increased when citizens see transparent, ethical AI in action, while compatibility and relative advantage are enhanced by participatory, inclusive design. The Resource-Based View (RBV) is also supported, as institutions with robust digital skills, ethical frameworks, and stakeholder engagement are better positioned to achieve sustainable governance advantages (Ashok et al., 2022; Swapnil et al., 2024; Ahmad et al., 2024).

Introducing a political economy lens, research underscores that power dynamics, vested interests, and institutional inertia can hinder ethical AI adoption. Comparative studies reveal that successful frameworks such as the EU AI Act emerge from multi-stakeholder negotiations that balance innovation with public interest, while failures often stem from regulatory capture or lack of enforcement (Koniakou, 2022; Celsi and Zomaya, 2025; Erman and Furendal, 2022). Thus, aligning the ISGT with established frameworks and explicitly addressing political economy factors ensures both international relevance and local effectiveness.

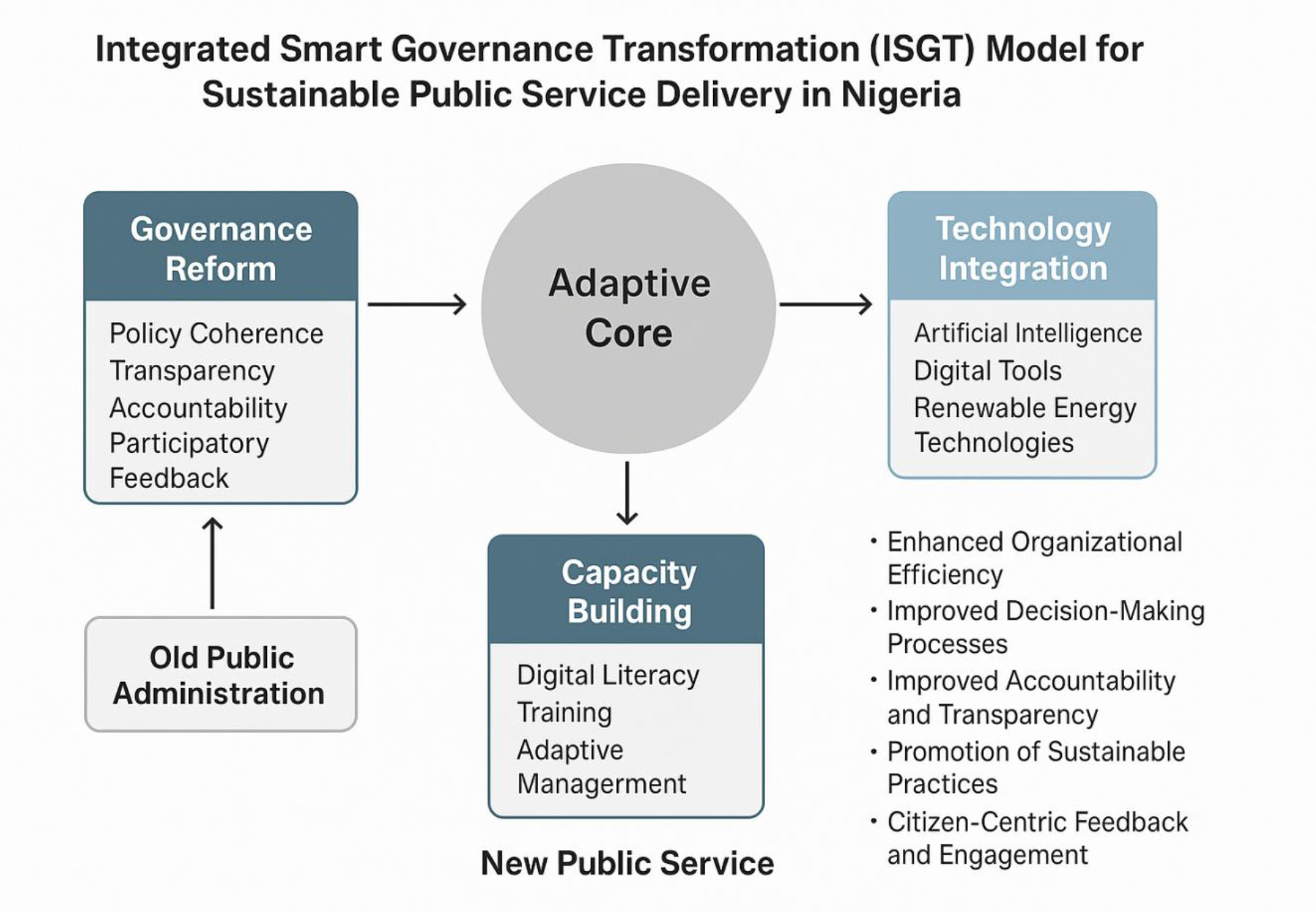

The Integrated Smart Governance Transformation (ISGT) Model (Figure 1) presents a holistic framework for reimagining urban public service delivery in Nigeria through the synergistic interaction of Governance Reform, Technology Integration, and Capacity Building. Grounded in empirical and thematic evidence, the model addresses key barriers such as resistance to change, digital literacy gaps, infrastructural limitations, ethical concerns, and weak political commitment by embedding adaptive, inclusive, and sustainability-oriented mechanisms for reform.

Figure 1

Conceptual model: Integrated Smart Governance Transformation (ISGT) for Sustainable Public Service Delivery in Nigeria. Source: Authors analytical framework, 2025.

The Governance Reform pillar promotes transparency, accountability, and participatory decision-making to rebuild public trust and enhance urban administrative responsiveness. The Technology Integration pillar encourages the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain-enabled systems, and Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) to improve efficiency, transparency, and environmental sustainability in municipal service delivery. Meanwhile, the Capacity Building pillar prioritizes digital literacy, adaptive management, and technical competence among city officials to overcome institutional rigidity and accelerate Nigeria's transition toward smart, resilient, and sustainable cities, in alignment with SDG 7, SDG 11, and SDG 16.

At the center of the model lies an Adaptive Core, representing the dynamic intersection of governance, technology, and capacity development. This core facilitates a progressive transformation from Old Public Administration (OPA) characterized by rigid hierarchies and paperwork to New Public Management (NPM), which focuses on efficiency, and ultimately to New Public Service (NPS), emphasizing citizen engagement and inclusivity. The model's outcomes include enhanced organizational efficiency, improved decision-making, strengthened accountability, and the promotion of sustainable practices across institutions. Contextually, it aligns with Nigeria's developmental priorities by integrating renewable energy to address chronic infrastructure gaps and promoting ethical, citizen-centered governance consistent with SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). Overall, the ISGT model offers a context-sensitive blueprint for transforming Nigeria's public sector into a smart, transparent, and sustainable governance system driven by technology, human capacity, and political will.

This model aligns with the study's objectives by integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI), digitalization, and Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) to transform urban public service delivery and address critical challenges related to efficiency, transparency, and citizen welfare in Nigeria's cities. As noted by Ejiyi et al. (2025), advancements in AI are essential for overcoming regulatory and data-related barriers to renewable energy adoption. The ISGT model is envisioned to evolve into the Framework for Integrating Renewable Energy Solutions and Technological Innovations for the Digital Transformation of Public Service (FIREs-TIDTPS) a holistic urban governance framework that synthesizes AI, blockchain-enabled digitalization, and RETs to create transparent, energy-secure, and sustainable municipal institutions aligned with SDG 7, SDG 11, and SDG 16.

Model justification: linking the sustainable smart governance model to Nigeria's urban public service delivery

Scholarly research supports the model's core arguments (see Figure 1) by highlighting the evolution of governance paradigms in Nigeria and the transformative role of technology integration and capacity building.

Scholarly research supports the model's core arguments (see Figure 1), emphasizing the evolution of governance paradigms in Nigeria's urban context and the transformative potential of technology integration and capacity building in achieving sustainable city management. Studies on digital governance and smart-city transitions highlight how adopting AI-driven systems, renewable energy solutions, and data-enabled decision-making can strengthen institutional performance, enhance transparency, and foster citizen participation. Studies show that traditional bureaucratic systems (Old Public Administration) are often hampered by inefficiencies, legacy systems, and limited citizen engagement, which undermine public trust and service delivery (Ikeanyibe et al., 2017; Yagboyaju and Akinola, 2019; Momoh et al., 2025). The shift toward New Public Management (NPM) and New Public Service (NPS) paradigms is advocated to promote transparency, efficiency, and participatory governance, aligning with SDG 16.6 and 16.7 (Ikeanyibe et al., 2017; Momoh et al., 2025). Empirical evidence demonstrates that community participation, capacity building, and the use of digital tools significantly enhance accountability, project sustainability, and responsiveness in governance, especially when barriers such as low awareness and inadequate infrastructure are addressed (Awoonor, 2025; Adeyeye and Aladesanmi, 2011; Mohammed and Bardai, 2024).

Technology integration through AI, digitalization, and renewable energy has been shown to improve decision-making, reduce corruption, and drive organizational efficiency, but its success depends on robust governance frameworks and investment in skills development (Oladeinde et al., 2024; Adeyeye and Aladesanmi, 2011; Essien et al., 2025). Capacity building, including targeted training and re-skilling, is repeatedly identified as essential for supporting reform and equipping public servants to adapt to new technologies and governance models (Nnaji et al., 2023; Mohammed and Bardai, 2024; Awoonor, 2025; Essien et al., 2025; Nnaji et al., 2026). The convergence of these elements leads to improved accountability, enhanced efficiency, better decision-making, and the promotion of sustainable practices, directly supporting the SDGs and the model's outcomes (Awoonor, 2025; Oladeinde et al., 2024; Momoh et al., 2025; Essien et al., 2025).

Scholarly perspectives on governance transformation in Nigeria emphasize that political economy factors such as the distribution of power, elite interests, and institutional dynamics are central to understanding both progress and persistent challenges. The “veto players” theory, for example, demonstrates that Nigeria's policy-making is often shaped by powerful actors who can block or dilute reforms, leading to a trade-off: while more veto players may reduce corruption, they can also slow or complicate national decision-making and the delivery of public goods (Dube, 2019). Elite theory research further reveals that, despite structural changes since democratization, Nigeria's political elite have shown limited innovation or transformation toward good governance, with entrenched interests and institutional inertia impeding reform (Yagboyaju and Akinola, 2019; Kifordu, 2022).

Scholars argue that governance failures in Nigeria are not simply due to resource constraints or technical issues, but are deeply rooted in the self-interest and priorities of political leadership, which often override the public good (Yagboyaju and Akinola, 2019; Ivorgba, 2024). This is reflected in persistent issues such as corruption, weak state capacity, and the prioritization of private or local interests over national development. Practical experiences from donor-led governance programs, such as the UK's DFID, show that adopting a “thinking and working politically” approach one that explicitly accounts for Nigeria's political economy can create “islands of effectiveness,” but systemic transformation remains difficult without broader shifts in power relations and incentives (Williams et al., 2019).

Recent scholarship also highlights the importance of socially embedded governance models that recognize the role of informal networks, local actors, and the need for accountability and transparency beyond technocratic solutions (Idike et al., 2019; Roelofs, 2023). Thus, integrating power and political economy theories into governance reform models is seen as essential for realism and policy relevance, as these perspectives illuminate why reforms succeed or fail and how sustainable change can be achieved in the Nigerian context (Dube, 2019; Kifordu, 2022).

The proposed ISGT and the FFIREs-TIDTPS provide a holistic approach for advancing sustainable urban management and smart-city development in Nigeria. See Table 1 for the summary of theories and analytical frameworks for sustainable smart governance in Nigeria and their policy implications. By integrating AI-driven decision-making systems, blockchain-enabled transparency, and renewable energy technologies (RETs), these models address critical challenges in municipal governance, including inefficient service delivery, unreliable power supply, and weak citizen engagement.

Table 1

| Theory/Analytical framework | Key concepts | Application in the smart governance model | Governance core component link | Relevant SDG indicators | Expected outcomes | Policy implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion of Innovations (Miller, 2015) | Relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, observability | Explains how governance reforms and technology solutions progress from pilot stages to full adoption, overcoming bureaucratic inertia and cultural resistance; supports transition from OPA to NPM/NPS | Technology Integration—AI, digitalization, and renewable energy for improved decision-making and service delivery | SDG 4.4 (skills), 9.5 (technological capabilities), 16.6 (effective institutions), 16.7 (participatory decision-making) | Improved Accountability and Transparency (IAP); Enhanced Organizational Efficiency (EOE); Improved Decision-Making Processes (IDP) | Adopt phased implementation of AI and digital governance reforms; invest in awareness campaigns to build citizen and staff confidence; ensure policy frameworks support pilot-to-scale adoption |

| Resource-Based View (Barney, 1991) | VRIN resources (Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, Non-substitutable); dynamic capabilities | Demonstrates how strategic mobilization of human, technological, and energy resources sustains governance reforms and builds institutional adaptability | Governance—policy coherence, transparency, interest aggregation; Capacity Building—skills training, re-skilling, retention | SDG 4.4 (skills), 7 (sustainable energy), 9.5 (technological capabilities), 16.6 (effective institutions) | Promotion of Sustainable Practices (PSP); Resilient governance systems; Increased citizen trust; Energy-efficient public services | Prioritize strategic resource audits to identify and leverage unique national assets; embed renewable energy policies in ICT infrastructure; allocate funds for continuous upskilling of public servants |

| ISGT | Alignment with international AI ethics (EU AI Act, UNESCO recommendations); integration of political economy considerations | Establishes binding ethical guidelines for AI use in governance, ensuring transparency, accountability, fairness, and compliance with global best practices; adapted for Nigerian public sector realities | Governance—ethical oversight, citizen rights protection; Technology Integration—AI accountability mechanisms | SDG 16.6 (effective institutions), 16.7 (inclusive decision-making), 17.14 (policy coherence for sustainable development) | Legitimacy in AI deployment; Reduction of ethical risks; Increased citizen trust in digital governance | Create enforceable AI ethics policies; mandate regular AI compliance audits; integrate citizen feedback mechanisms to monitor AI's social and ethical impact |

| FIREs-TIDTPS—Framework | Integration of AI, blockchain, digitalization, and renewable energy technologies (RETs) for systemic reform | Provides a holistic pathway for transforming Nigerian public institutions into transparent, efficient, and sustainable entities; addresses digital divide and energy constraints | Technology Integration—AI, blockchain, RETs; Capacity Building—technical training; Governance—transparency, efficiency, anti-corruption | SDG 4.3 (access to tertiary education), 4.4 (skills), 7 (affordable clean energy), 9.5 (technology capabilities), 16.6 (effective institutions) | Transparent service delivery; Reduced corruption; Sustainable operations; Enhanced citizen engagement | Develop national policies integrating renewable energy with ICT in public service; provide incentives for blockchain-based transparency systems; ensure cross-sector partnerships to fund and sustain reforms |

Summary of theories and analytical frameworks for sustainable smart governance in Nigeria and their policy implications.

Source: Author's analytical explanations, 2025.

In urban contexts, these frameworks facilitate energy-secure e-governance platforms, real-time data analytics for infrastructure management, and inclusive digital participation. They enable cities such as Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt to transition toward smart, resilient, and low-carbon governance systems that align with SDG 7, SDG 16, and SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities. Thus, the models bridge governance innovation, urban energy transition, and technological inclusion to transform city administration and enhance citizen wellbeing.

Methodology

This study adopts a mixed-methods research design to leverage the complementary strengths of quantitative and qualitative data (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018). The choice of a mixed-methods approach is specifically justified by the complexity of smart governance transitions, which require both the statistical breadth of survey data to identify adoption trends and the narrative depth of qualitative insights to explain the “how” and “why” of institutional resistance. By integrating these strands, the study addresses specific research objectives through a convergent design: the quantitative component evaluates the extent of technology integration across MDAs, while the qualitative component explores the underlying socio-political enablers and barriers. This integration occurs at the interpretation stage, where qualitative findings are used to triangulate and contextualize the statistical results, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of Nigeria's public service transformation. The approach investigates the adoption and urban impacts of advanced technologies specifically Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain-enabled digitalization, and Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) within Nigeria's evolving urban public service systems.

Sampling strategy and participant selection

The target population comprised public institutions operating across federal, state, and municipal (local-city-level) administrations, yielding 642 valid responses from diverse organizational contexts. To ensure the acquisition of high-quality, specialized data from this population, the study adopted a purposive, multi-stage sampling strategy. This approach is consistent with global best practices in governance and smart city research, where access to information-rich respondents is essential for understanding complex institutional dynamics (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018). Participants were intentionally selected based on their institutional roles, professional expertise, and direct involvement in public service delivery, digital governance, urban planning, or energy management. The sampling frame spanned federal, state, and municipal levels to capture governance dynamics across Nigeria's decentralized administrative tiers. For the qualitative strand, key informant interviews and focus groups specifically targeted senior administrators, policy advisers, ICT managers, and energy officers whose experiential knowledge enabled an in-depth exploration of institutional constraints. This purposive approach prioritizes analytical depth and contextual validity over simple statistical representativeness, ensuring that the findings reflect the perspectives of those driving innovation readiness within the Nigerian public service.

Prior to analysis, all survey data underwent systematic screening to ensure accuracy, completeness, and analytical reliability. Responses were examined for inconsistencies, duplicate entries, and excessive non-response. Cases with substantial missing data beyond an established threshold were excluded using listwise deletion, a method widely accepted in large-sample governance research when missingness is non-systematic (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2019). Sporadic missing values were assessed to ensure they did not bias key variables or distort inferential outcomes. Data cleaning procedures also involved consistency checks across related variables and validation of scale responses to confirm logical coherence. These steps ensured that the final dataset reflected high-quality, analyzable information, preserving statistical power while maintaining methodological rigor.

Technology adoption index construction

To measure the overall technological maturity of the participating institutions, a Technology Adoption Index (TAI) was constructed. The index utilizes a composite scoring logic based on the 17 key adoption statements detailed in the survey instrument. Variable selection was guided by the theoretical constructs of “Trialability,” “Observability,” and “Relative Advantage” from the Diffusion of Innovations theory. Scaling involved 5-point Likert items, which were then aggregated using a simple additive weighting method to provide a mean maturity score for each institution. This aggregation logic allows for a standardized comparison across federal, state, and municipal tiers, transforming individual perceptions into a quantifiable metric of institutional innovation readiness. The resulting index serves as the primary dependent variable for the inferential analyses conducted in this study.

Data were collected through a structured questionnaire covering technology adoption, perceived enablers and barriers, and socio-economic outcomes. The survey instrument was systematically designed to operationalize the core constructs of smart governance and institutional capacity. Drawing on established scales, the questionnaire comprised five structured sections measuring: (i) Artificial Intelligence adoption, (ii) blockchain utilization, (iii) renewable energy integration, (iv) institutional readiness, and (v) perceived barriers. Each construct was measured using 5-point Likert-type items to capture respondents' perceptions and levels of institutional maturity. Items were contextualized to reflect Nigeria's public sector realities while retaining conceptual alignment with the Diffusion of Innovations (DoI) theory and the Resource-Based View (RBV). The instrument was reviewed by domain experts and pre-tested to ensure content validity. A summarized version of this instrument, including representative items, is provided in Supplementary Appendix A to enhance scholarly transparency and replicability. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations) summarized respondents' characteristics and levels of technology adoption. Inferential analyses included chi-square tests to examine associations between categorical variables, independent-samples t-tests to compare mean adoption scores across institutional levels, and Pearson correlation analysis to assess relationships between key governance and technology adoption indicators. All statistical tests were conducted at a 5% significance level. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed prior to analysis, and results were interpreted conservatively where assumptions were borderline. The study employed a combination of descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. Each statistical test was explicitly linked to the research questions to ensure analytical coherence.

Qualitative data from interviews and focus groups were analyzed using a hybrid inductive/deductive thematic analysis approach. Deductive coding was informed by the study's theoretical framework, while inductive coding allowed unanticipated themes to emerge from participants' narratives. The process involved iterative readings, open coding, theme refinement, and cross-validation across data sources. Analytical rigor was enhanced through reflexive memoing and systematic comparisons of interview and focus group insights. Themes were consolidated based on recurrence and explanatory power, aligning with international qualitative research standards to enhance the dependability and transferability of the findings. This research addresses the ethical complexities of AI-enabled governance by incorporating algorithmic transparency and accountability into our framework. We acknowledge risks such as data privacy breaches and algorithmic bias, which could marginalize vulnerable populations. Emphasizing “Responsible AI” governance, we prioritize citizen consent as essential for digital trust, aligning our study with international norms on digital ethics and responsible public sector innovation.

A total of 642 valid survey responses were collected, representing a response rate of 91.7% from the targeted sample size of 700.

The sample is balanced with a majority male representation and fairly distributed age groups, reflecting Nigeria's public sector demographics. Education levels skewed toward tertiary qualifications, appropriate for technology adoption studies (Table 2).

Table 2

| Demographic variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 372 | 58.0 |

| Female | 270 | 42.0 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–29 | 154 | 24.0 |

| 30–39 | 253 | 39.4 |

| 40–49 | 158 | 24.6 |

| 50+ | 77 | 12.0 |

| Education level | ||

| Secondary or less | 48 | 7.5 |

| Diploma/Certificate | 82 | 12.8 |

| Bachelor's degree | 352 | 54.8 |

| Postgraduate degree | 160 | 24.9 |

| Institution type | ||

| Federal Government | 261 | 40.7 |

| State Government | 203 | 31.6 |

| Local Government | 178 | 27.7 |

Demographic information.

The results indicate varying levels of adoption across technologies. AI-driven administrative processes show moderate adoption (Mean = 3.02), suggesting institutions are progressively integrating AI into operations. Blockchain systems record the lowest uptake with a low to moderate adoption score (Mean = 2.64), reflecting slow integration and possible structural or regulatory challenges. Renewable energy technologies demonstrate the strongest adoption level with a moderate adoption score (Mean = 3.17), highlighting a relatively higher commitment to sustainable infrastructure compared to digital systems.

Strong positive correlations among perceptions of political will, incentives, training, institutional coordination, and actual technology adoption affirm the centrality of coordinated policy and institutional support for FIREs-TIDTPS scalability.

All policy perception variables are significant independent predictors of adoption. Political commitment, incentives, training, and coordination collectively underpin scalable integrated AI and RET adoption across institutional tiers. Analysis revealed a significant positive association between these policy-related factors and adoption status. Logistic regression confirmed that high political commitment notably increased the likelihood of technology integration. These findings underscore the critical role of supportive policy environments and coordinated implementation strategies in scaling sustainable digital governance nationwide.

Findings

This analysis investigates the adoption of advanced technologies specifically Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain, and Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs) within Nigeria's public service sector. The study, which involved 642 valid responses from federal, state, and local institutions, reveals moderate adoption levels for AI (Mean ≈ 3.02) and RETs (Mean ≈ 3.17), while blockchain adoption is notably low (Mean ≈ 2.64). Key barriers identified include a lack of digital skills, weak energy infrastructure, and limited government incentives. Positive governance outcomes were observed, with correlations indicating improvements in transparency (Mean = 3.15), efficiency (Mean = 3.17), and citizen engagement (Mean = 3.09; Table 3). These findings align with several SDGs, particularly SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). Political commitment emerged as a crucial driver of adoption, confirmed by statistical analysis.

Table 3

| Item No | Adoption statement | SA | A | N | D | SD | Total | Mean score | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AI-driven administrative processes are adopted in my institution | 210 | 230 | 65 | 87 | 50 | 642 | 3.02 | Moderate adoption |

| 2 | Blockchain systems are operational in our workflows | 150 | 195 | 110 | 105 | 82 | 642 | 2.64 | Low to moderate adoption |

| 3 | Renewable energy technologies power our public service infrastructure | 230 | 210 | 90 | 74 | 38 | 642 | 3.17 | Moderate adoption |

| 4 | Lack of employee skills limits AI adoption | 230 | 195 | 90 | 65 | 62 | 642 | 3.20 | Barrier accepted |

| 5 | Political commitment facilitates technology integration | 220 | 205 | 75 | 75 | 67 | 642 | 3.12 | Facilitator accepted |

| 6 | Poor energy infrastructure hinders renewable energy adoption | 250 | 180 | 80 | 72 | 60 | 642 | 3.26 | Barrier accepted |

| 7 | There is strong political commitment to the integration of digital technologies and renewable energy in our institution. | 200 | 150 | 200 | 40 | 52 | 642 | 3.35 | Facilitator accepted |

| 8 | Transparency improved due to framework implementation | 215 | 210 | 75 | 72 | 70 | 642 | 3.15 | Moderate improvement |

| 9 | Service efficiency increased after framework deployment | 230 | 190 | 80 | 65 | 77 | 642 | 3.17 | Moderate improvement |

| 10 | Accountability mechanisms strengthened because of the framework | 205 | 220 | 72 | 75 | 70 | 642 | 3.11 | Moderate improvement |

| 11 | Operational cost savings realized due to renewable energy | 190 | 215 | 85 | 85 | 67 | 642 | 3.02 | Moderate impact |

| 12 | Service reliability improved following technology adoption | 220 | 200 | 80 | 70 | 72 | 642 | 3.11 | Moderate impact |

| 13 | Citizen engagement increased after technology adoption | 210 | 210 | 90 | 65 | 67 | 642 | 3.09 | Moderate Impact |

| 14 | Sufficient political will and policy support exists | 150 | 220 | 90 | 100 | 82 | 642 | 2.84 | Low-to-moderate agreement |

| 15 | Government incentives effectively encourage AI and RET adoption | 130 | 205 | 110 | 102 | 95 | 642 | 2.69 | Low agreement |

| 16 | Adequate training and capacity building programs are provided | 180 | 210 | 80 | 85 | 87 | 642 | 2.98 | Moderate agreement |

| 17 | Institutional coordination supports integrated deployment | 160 | 215 | 95 | 92 | 80 | 642 | 2.90 | Moderate agreement |

Frequency distribution and mean scores for adoption items.

To enhance technology integration and urban sustainability, the study recommends the implementation of the Integrated Smart Governance Transformation (ISGT) model (Figure 1). This framework addresses the complex challenges facing Nigeria's urban public service systems by promoting regulatory support for evaluating and adopting innovative renewable energy technologies, including emerging solutions such as microsonic energy devices. It emphasizes inclusive participation, phased implementation, and capacity building to strengthen efficiency, transparency, and citizen welfare at the city level. By overcoming systemic governance and infrastructural barriers, Nigerian cities can harness digital and renewable innovations to achieve smart, resilient, and sustainable urban governance aligned with SDGs 7, 11, and 16 (see Tables 4, 5, 6).

Table 4

| Institution type | Agree (SA + A) | Non-agree (N + D + SD) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Govt | 240 | 46 | 286 |

| State Govt | 66 | 94 | 160 |

| Local Govt | 34 | 162 | 196 |

| Total | 440 | 202 | 642 |

AI Adoption by institution type.

Table 5

| Variable | Adoption index | Political will perception | Government incentives | Training support | Institutional coordination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoption index | 1.00 | 0.62*** | 0.54*** | 0.59*** | 0.56*** |

| Political will perception | 0.62*** | 1.00 | 0.58*** | 0.67*** | 0.63*** |

| Government incentives | 0.54*** | 0.58*** | 1.00 | 0.61*** | 0.48*** |

| Training support | 0.59*** | 0.67*** | 0.61*** | 1.00 | 0.55*** |

| Institutional coordination | 0.56*** | 0.63*** | 0.48*** | 0.55*** | 1.00 |

Correlation between policy support perceptions and adoption index.

*** p < 0.001.

Table 6

| Predictor variable | Odds ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political will perception (High) | 3.15 | 2.18–4.56 | <0.001 |

| Perceived government incentives | 2.78 | 1.89–4.09 | <0.001 |

| Training and capacity support | 2.95 | 2.03–4.29 | <0.001 |

| Institutional coordination | 2.55 | 1.70–3.81 | <0.001 |

| Control: institution type (federal vs. local) | 2.40 | 1.63–3.53 | <0.001 |

Multivariate logistic regression: predicting adoption considering policy perceptions.

Thematic analysis

-

Resistance to change

Description: many respondents expressed concerns about the potential displacement of workers due to automation. There is a prevailing fear that machines will replace human roles, leading to natural resistance against adopting new technologies.

Supporting quotes:

° “People fear the machines will replace them. There is little training or reward, so resistance is natural.” (Senior Administrator)

° “The old culture values paperwork and face-to-face contacts. Digital systems feel alien and threatening.” (Local Government Staff)

-

Digital literacy and skills gap

Description: a significant barrier to technology adoption is the uneven distribution of digital literacy among public servants and citizens. Limited technical skills, especially in rural areas, hinder engagement with digital systems.

Supporting quotes:

° “Digital knowledge is uneven, especially outside urban centers. Without continuous training, systems fail to deliver.” (ICT Officer)

° “Some people don't even have smartphones or reliable internet; expecting them to engage digitally is unrealistic.” (Citizen Focus Group Participant)

-

Infrastructure limitations

Description: unreliable electricity and inadequate infrastructure are seen as foundational barriers to effective digital governance. Respondents noted that frequent power outages disrupt services and hinder the implementation of digital solutions.

Supporting quotes:

° “Our servers shut down often; generators are expensive and noisy. Solar offers hope but funding is limited.” (IT Manager)

° “Micro sonic energy is interesting but untested here; regulators want proof before approval.” (Energy Specialist)

-

Ethical concerns and trust

Description: there is a strong emphasis on the need for ethical guidelines and oversight in the adoption of advanced technologies. Respondents voiced concerns about discrimination and the opacity of automated decisions.

Supporting quotes:

° “People worry machines may discriminate or hide decisions. We need clear ethical rules and human oversight.” (Policy Maker)

° “Blockchain can seal corruption leaks if fully implemented and made accessible.” (Civil Society Leader)

-

Political commitment and support

Description: The success of technology adoption heavily relies on political backing and financial resources. Respondents indicated that innovations cannot thrive without strong political support and successful pilot projects to demonstrate feasibility.

Supporting quotes:

° “Without political backing, no innovation can thrive in bureaucracies.” (Senior Policy Advisor)

° “Showcasing successful pilots gave us proof to convince skeptical colleagues.” (Project Manager)

The thematic analysis highlights critical barriers and enablers shaping the adoption of advanced technologies within Nigeria's urban public service systems. Overcoming resistance to change, enhancing digital literacy among city administrators, strengthening urban infrastructure and energy reliability, establishing ethical and accountability frameworks, and ensuring consistent political support are essential for fostering an environment conducive to smart innovation. This multidimensional approach is vital for transforming municipal governance, improving urban service delivery, and advancing sustainable, technology-driven cities in line with SDG 7, SDG 11, and SDG 16.

Discussion

The study found that AI and digital technology adoption within Nigeria's urban public institutions remains moderate overall, with significant disparities across institution types and regions. Federal and metropolitan agencies, often equipped with better funding, infrastructure, and technical capacity, demonstrated higher levels of AI and Renewable Energy Technology (RET) adoption compared to subnational and municipal entities. These differences reflect broader urban–rural and intergovernmental inequalities that influence the pace of digital transformation. Strengthening local capacity, decentralizing innovation, and expanding renewable energy integration are therefore critical for enabling inclusive and sustainable smart urban governance across Nigeria's cities, paralleling findings by Adebanji et al. (2022) and Onwuegbuna et al. (2024), who documented disparities between federal and subnational levels.

However, beyond technical and regional disparities, the discussion must account for a complex web of contextual and institutional constraints. Organizational culture plays a pivotal role; the deeply entrenched “paperwork-based” bureaucratic identity in Nigeria often views digital transparency as a threat to traditional power dynamics rather than an efficiency gain. Furthermore, institutional readiness is frequently hampered by acute financial constraints and the lack of dedicated budget lines for technology maintenance. From a political economy perspective, adoption is often non-linear, as interests tied to manual, opaque procurement processes may subtly resist blockchain-enabled accountability. Understanding these “soft” barriers is essential, as they suggest that even with perfect infrastructure, adoption will stall without a fundamental shift in the administrative mindset and political will.

The significant association between digital literacy and governance outcomes underscores how human capital limitations act as gatekeepers of technological progress a critical insight aligned with Diffusion of Innovations Theory (Rogers, 2003), which emphasizes compatibility and complexity as drivers of adoption. Qualitative data revealed that entrenched bureaucratic culture, fear of job displacement, and inadequate training impede uptake, reinforcing barriers discussed by Haesevoets et al. (2024). Leveraging AI, digitalization, and renewable energy technologies is central to improving decision-making processes and service delivery. These technologies can mitigate corruption and inefficiencies, driving organizational effectiveness. The study finds moderate adoption levels for AI (Mean ≈ 3.02) and Renewable Energy Technologies (RETs; Mean ≈ 3.17), indicating a foundation upon which to build.

Beyond the empirical successes of these technologies, it is imperative to address the inherent technocratic risks and the potential for “techno-solutionism” within Nigeria's smart governance agenda. Critics of smart urbanism warn that an over-reliance on algorithmic decision-making can lead to governance asymmetries, where technical efficiency is prioritized at the expense of social equity and democratic deliberation. In the Nigerian context, there is a risk that AI and blockchain could be deployed as “digital band-aids” that mask deeper structural and political failures rather than resolving them. If the FIREs-TIDTPS model is implemented without a focus on universal access, it may inadvertently widen the digital divide, creating “islands of efficiency” in affluent urban nodes while further marginalizing rural and low-income populations. Situating this study within critical smart governance literature reveals that for technology to be truly transformative, it must be accompanied by institutional reforms that safeguard against the displacement of human discretion by automated systems. Therefore, the integration of AI and RETs must be viewed not as a purely technical fix, but as a socio-political project that requires continuous ethical oversight and a commitment to inclusive, non-technocentric governance.