1 Introduction

The 21st-century city faces the dual imperative of accommodating expanding populations while preserving ecological integrity. Urban land is finite, yet the demand for housing and infrastructure continues to rise, prompting cities to grow vertically and compactly (Lin, 2018). This densification, however, often comes at the perceived cost of urban nature. Traditional urban models treat green spaces as residual buffers to built form rather than integral components of the city's metabolism. Consequently, the discourse on sustainable cities has long oscillated between two poles: density as an economic and social necessity and greenness as an ecological ideal (McDonald and Beatley, 2020). This article challenges that binary. It argues that density and greenness are not mutually exclusive but can be interdependent dimensions of a single urban metabolism. When urban systems are designed to exchange energy, matter, and biodiversity, density itself can become a medium of ecological regeneration. The symbiotic city redefines urban sustainability as a metabolic process rather than a spatial compromise (Kennedy et al., 2011).

2 From biophilic aesthetics to metabolic function

The last decade has witnessed a surge in “green” architecture—vertical gardens, rooftop farms, and eco-parks integrated into high-density fabrics. While visually transformative, many of these interventions remain primarily aesthetic, addressing human wellbeing rather than ecosystem performance (Allam and Newman, 2023). The biophilic city paradigm celebrates human nature's connection but often stops short of reconfiguring the city's metabolic structure (de Lorenzo and de la Ossa, 2023).

By contrast, metabolic urbanism reconceptualizes nature as infrastructure. Green roofs and facades become organs within a broader ecological system, capable of filtering air, sequestering carbon, and regulating microclimates (Diaz et al., 2024). In this sense, vegetation is not decorative but performative, as it sustains the city's energy and material cycles. This approach embeds living systems across every layer of the city, transforming buildings into active ecological interfaces and urban corridors into biological networks that sustain biodiversity, regulate climate, and regenerate material and energy flows.

Singapore exemplifies this shift. Its “City in Nature” vision embeds vertical greenery and blue-green networks into planning codes, treating biodiversity as a measurable service rather than an aesthetic asset (Er, 2021). Similarly, Copenhagen's green infrastructure strategy links stormwater retention basins with cycling networks, demonstrating how environmental systems can double as social and transport infrastructures (Zouras, 2020). In Medellin, the “Green Corridors” initiative demonstrates how re-greening dense transport arteries can lower ambient temperatures and improve public health (Paniagua-Villada et al., 2024). These examples signal a transition from ornamental greenness to functional metabolism (Table 1).

Table 1

| City | Innovation | Ecological function |

|---|---|---|

| Singapore | Integration of vertical greenery habitat restoration, and connected blue-green networks under the “City in Nature” Strategy | Urban heat mitigation, habitat creation, and biodiversity connectivity |

| Copenhagen | Cloudburst plan activating streets/parks as flood conveyance and storage | Pluvial- flood risk reduction, multifunctional public realm |

| Medellin | Vegetated corridors along 18 road axes and 12 waterways | Surface/ambient temperature reduction (2 °C), biodiversity co-benefits |

Selected examples of metabolic urbanism in dense cities.

Source: Prepared by authors.

3 Reframing density: from constraint to catalyst

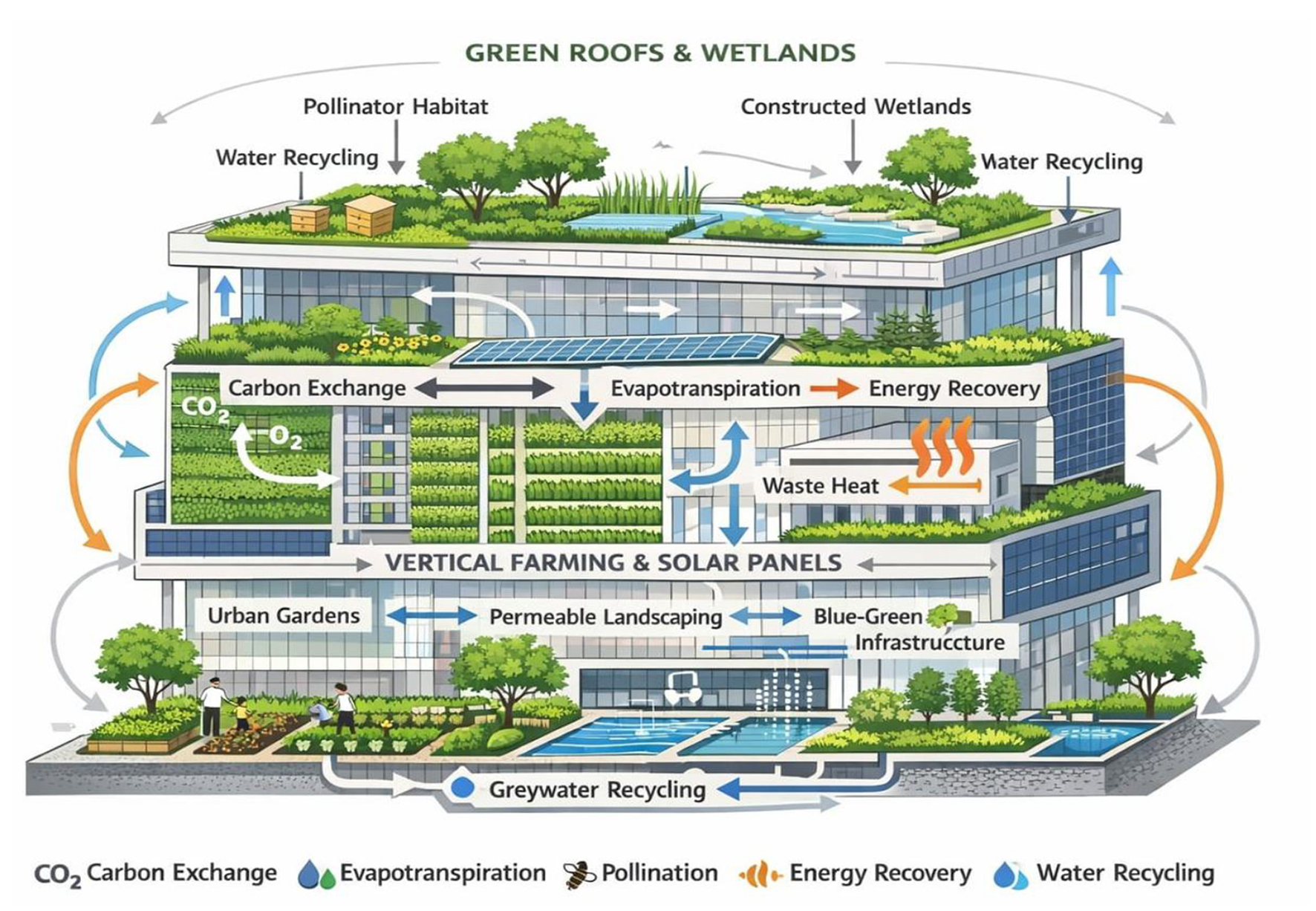

In the symbiotic city, density becomes an ecological amplifier rather than a constraint. High-rise districts, when designed metabolically, create vertical layers of habitats, from soil-based gardens at ground level to canopy ecosystems on rooftops (Sanchez and Swyngedouw, 2022). Buildings become living strata in which carbon exchange, evapotranspiration, and pollination occur simultaneously (Dawson, 2020).

Furthermore, metabolic density enables circular economies of energy and materials. Waste heat from buildings can power vertical farms, greywater can sustain rooftop wetlands, and photovoltaic facades can function as urban photosynthesis membranes (Hajer and Dassen, 2014). Such integrations convert density from a passive consumer of resources into an active ecological producer.

Yet, the transformation toward metabolic urbanism requires policy realignment. Urban performance must be measured not by static indicators such as “green area per capita,” but by dynamic metabolic flows—carbon flux, biodiversity, and energy circularity (Diaz et al., 2024). Quantifying how dense urban systems produce life will redefine how planners, financiers, and citizens perceive sustainability (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Symbiotic city model. A conceptual diagram, illustrating the cyclical flow of energy, carbon, water, and biodiversity across the dense urban fabric. The model depicts buildings, vegetation, and infrastructure as interconnected organs within a city-scale metabolism that supports reciprocal ecological exchanges. Source: This image was prepared by the authors with the help of AI.

4 Governance of the symbiotic city

Transitioning from linear urban systems to symbiotic metabolisms requires a new governance architecture. Existing zoning codes and building standards still privilege gray infrastructure over living infrastructure. Cities need institutional mechanisms, such as urban metabolism agencies, to monitor ecological throughput, much as treasuries monitor fiscal flows (Meyer et al., 2005). Regulatory incentives would reward developers for quantifiable ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, stormwater retention, or species habitat provision. Similarly, financial instruments such as “ecological performance bonds” could link open investment returns to diversity outcomes (Elmqvist et al., 2018).

Such approaches align with the global transition toward regenerative design, where cities are viewed as dynamic participants in Earth's ecological systems rather than external stressors (Tzaninis et al., 2021). By embedding metabolism into policy, governance shifts from managing land to cultivating life.

5 Conclusion: toward the photosynthetic city

The question “Can a city be dense and green?” needs to be interpreted differently. The goal is not to balance these qualities but to synthesize them to cultivate cities that are dense because they are green. In this future, urban metabolism becomes photosynthetic, infrastructures convert sunlight into energy, facades absorb carbon, and biodiversity thrives across vertical gradients.

The symbiotic city thus represents a new urban ethic that recognizes human habitats as living extensions of the biosphere. Density ceases to be a measure of cognition and becomes a measure of ecological intensity. As cities evolve, their success will not be judged by the quantity of green space they contain but by the vitality of the metabolisms they sustain.

Statements

Author contributions

RR: Writing – original draft. AD: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI is used for editing the manuscript as well for image generation.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Allam Z. Newman P. (2023). Revising Smart Cities with Regenerative Design. Basel: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-28028-3

2

Dawson K. (2020). Shifting sands in Accra, Ghana: the ante-lives of urban form (Doctoral dissertation). London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom.

3

de Lorenzo V. de la Ossa M. (2023). Synthetic biology enabling a shift from domination to partnership with natural space. J. Chin. Archit. Urbanism5:0619. doi: 10.36922/jcau.0619

4

Diaz C. G. Zambrana-Vasquez D. Bartolome C. (2024). Building resilient cities: a comprehensive review of climate change adaptation indicators for urban design. Energies17:1959. doi: 10.3390/en17081959

5

Elmqvist T. Bai X. Frantzeskaki N. Griffith C. Maddox D. McPhearson T. et al . (2018). Urban planet: Knowledge Towards Sustainable Cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781316647554

6

Er K. (2021). Transforming Singapore into a city in nature. Urban Solut.19, 68–77.

7

Hajer M. Dassen T. (2014). Smart About Cities: Visualizing the Challenge for 21st Century Urbanism. Rotterdam: Rotterdamnai010 publishers.

8

Kennedy C. Pincetl S. Bunje P. (2011). The study of urban metabolism and its applications to urban planning and design. Environ. Pollut.159, 1965–1973. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.10.022

9

Lin Z. (2018). “Vertical urbanism: re-conceptualizing the compact city,” in Vertical Urbanism, eds. Z. Lin and J. L. S. Gámez (London: Routledge), 3–18. doi: 10.4324/9781351206839-1

10

McDonald R. Beatley T. (2020). Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature Is Essential for the Success of Cities. Cham: Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-51665-9

11

Meyer J. L. Paul M. J. Taulbee W. K. (2005). Stream ecosystem function in urbanizing landscapes. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc.24, 602–612. doi: 10.1899/04-021.1

12

Paniagua-Villada C. Garizábal-Carmona J. A. Martínez-Arias V. M. Mancera-Rodríguez N. J. (2024). Built vs. green cover: an unequal struggle for urban space in Medellín (Colombia). Urban Ecosyst.27, 1055–1065. doi: 10.1007/s11252-023-01443-8

13

Sanchez F. Swyngedouw E. (2022). The urbanization of nature revisited: metabolic flows and political ecology in the Anthropocene. Prog. Hum. Geogr.46, 1258–1275.

14

Tzaninis Y. Mandler T. Kaika M. Keil R. (2021). Moving urban political ecology beyond the ‘urbanization of nature'. Prog. Hum. Geogr.45, 229–252. doi: 10.1177/0309132520903350

15

Zouras J. N. (2020). Collaborative decision-making in green and blue infrastructure projects: the case of Copenhagen's Hans Tavsens Park and Korsgade (Master's thesis). KTH Royal Institute of Technology; School of Architecture and the Built Environment.

Summary

Keywords

biodiversity, ecological performance analysis, solar energy, the symbiotic city, urban density, urban sustainability

Citation

Raut R and Deshpande A (2026) The symbiotic city: when density becomes green. Front. Sustain. Cities 8:1760474. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2026.1760474

Received

04 December 2025

Revised

27 December 2025

Accepted

02 January 2026

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

8 - 2026

Edited by

Daniel Jato-Espino, Valencian International University, Spain

Reviewed by

Jeferson Tavares, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Raut and Deshpande.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rajesh Raut, rajesh.raut@mitsde.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.