The Skin-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Is Crucial for Parasite Control

The skin represents one of the largest organs in mammalians and accomplishes complex physiological and immunological functions (1). The most outer epidermal layer of this cutaneous shield is pivotal to protect the body from invading microorganisms. However, this barrier is futile, once pathogens are incorporated into deeper dermal compartments by bloodsucking arthropods. In this case, arthropod-associated pathogens such as fungi, protozoans, viruses, and bacteria are transmitted into the dermis of mammalians (2). After such a barrier-breakdown, a promptly reacting innate immune response is crucial to eliminate most of the arthropod-associated pathogens at the site of infection (3).

Pathogens have learned to evade some mechanisms of innate immunity (4–6). Thus, a precise pathogen-specific adaptive immunity has to be generated, to avoid an uncontrolled spreading of pathogens and tissue damage. This highly evolved immune response combines a network of cellular and humoral components capable of recognizing foreign antigens to eliminate pathogens and pathogen-harbouring cells (7, 8). In the case of bloodsucking arthropods, most of these host-pathogen interactions take place within the skin-associated lymphoid tissue (SALT) that combines three major components: First, the cutaneous microenvironment equipped with immune cells capable of accepting, processing, and presenting antigens at the site of adaptive effector cell function. Second, the efferent lymphatics connecting the dermal compartment with skin-draining lymph nodes (SDLN). Third, the paracortex within the SDLN where T cell-mediated immunity against skin-derived antigens is generated (9).

A coordinated interaction of immune cells is a precondition for efficient adaptive immunity within the SALT. In this context, the experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis (ECL) of mice has to be emphasized. In the model, promastigote Leishmania (L.) major parasites are mostly incorporated by a syringe into the dermal compartment to mimic the natural transmission by bloodsucking sand flies (10). Ground-breaking aspects of T cell-mediated immunity, such as T helper (Th) 1 and Th2 polarization arose from studies in ECL (11, 12). It has been shown, that healing of ECL correlates with the presence of a profound Th1 cell expansion and the production of IFN-γ that activates macrophages to eliminate intracellular parasites (13). IL-12 has been identified as the Th1-polarizing cytokine important for Th1 cell differentiation (14, 15). By contrast, IL-4 promotes Th2 cell development and susceptibility for ECL (16).

Langerhans Cells Are Involved in Adaptive Immunity Against Leishmania Parasites

A subset of specialized myeloid cells, the epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs), has been favoured to generate Leishmania-specific T cells in vivo. In 1992, studies revealed that epidermal cells, including LCs, can activate the Leishmania-specific T cell clone L1/1 and antigen-primed T cells derived from susceptible BALB/c mice (17). Furthermore, DEC-205/CD205/NLDC-145+ LCs can transport L. major antigens (L-Ag) to the SDLNs of susceptible BALB/c mice (18). Flohé et al. demonstrated that a single i.v. treatment with epidermal-derived LCs, that had been pulsed with L-Ags, induces adaptive immunity and resistance against a L. major (MHOM/IL/81/FE/BNI) infection (2×105 stationary-phase promastigote parasites/i.d.) in normally susceptible BALB/c mice (19). The release of Th1-polarizing cytokines by LCs has also been proven by other groups using L. major clone V1 (MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin) and low-dose models of ECL (20, 21). Thus, LCs have been in the spotlight as decisive cells to induce a protective adaptive immunity in ECL for a long time.

Changing Views on LC Functions in ECL

Inspired by novel markers, useful for the dissection of LCs and dendritic cell (DC) subsets, it has been shown by different in vivo configurations, varying in L. major strains and dose of application, that LCs are not the only “antigen-presenting cells” that are involved in orchestrating T cell-mediated immunity (22–26). L-Ag-specific T cell proliferation is predominantly driven by Langerin/CD207- DC subsets (epidermal LCs are Langerin/CD207+), suggesting that Langerin/CD207- dermal-derived DCs (dDCs) are crucial for protective immunity in ECL using different L. major strains [MHOM/IL/81/FE/BNI or clone VI (MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin)] and applications (low- or high-dose) for needle infections (27–30). Indeed, LCs can present L-Ags to T cells under certain conditions (17–21). However, the question remains, which pathways of T cell development and immunity are induced by LCs in ECL? To address this aspect, in vivo models of inducible ablation of LCs and other DC subsets have been used (31). It has been proven that C57BL/6-LangDTR mice remain resistant against L. major (MHOM/IL/81/FE/BNI) high-dose infection even after depleting LCs (29). Protective Th1 cells are also induced in SDLNs in the absence of LCs (29). Other groups using low-dose models and the L. major strain clone VI (MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin), were able to confirm that finding - mice depleted for LCs can still control the disease (28). Consequently, the presence of lymph node resident or dDCs is sufficient to generate a protective immunity in in vivo ECL (28, 29).

One should not get the impression that epidermal LCs represent a kind of rudimental or redundant myeloid subset, without specific immunological functions. Speculations in this field assumed that LCs are involved in dampening the immune response against Leishmania parasites (32, 33). This hypothesis has been confirmed some years later, by demonstrating that LCs participate in expanding regulatory CD4+ T cells (Treg) [low-dose model; L. major strain clone VI (MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin) (28)] and other IL-10 and IFN-γ expressing CD4+ T cells [high-dose model; L. major MHOM/IL/81/FE/BNI (29)] with regulatory capacity (34). Consequently, LCs are involved in balancing immune responses within the SALT. This aspect has also been supported by other experimental systems, showing that LCs are involved in the maintenance of tolerance to peripheral skin-associated antigens (35–37).

Apart from this tolerance promoting functions, LCs are also crucial in ECL for priming and differentiation of follicular helper T cells (Tfh) and the subsequent formation of early germinal centres (GC) within SDLNs [high-dose; L. major MHOM/IL/81/FE/BNI (38)]. A number of other immunization-based and disease models, such as atopic dermatitis, have also confirmed that LCs promote Tfh differentiation and GC formation (39–42). This general “LC attribute” of Tfh polarization, needs to be examined in more detail. In ECL, B cell-deficient µMT mice develop severe lesions, compared to WT mice. However, the absence of B cell-mediated immunity does not affect the final outcome of ECL (43). These facts might explain why LC-depleted C57BL/6-LangDTR mice can control ECL, even in the absence of early GC formation and restricted Tfh development (38).

Natural Transmission of Leishmania Parasites Is Not Sterile

In ECL, LCs contribute to the differentiation of distinct CD4+ T cell subsets such as Foxp3+ Treg cells, IL-10 and IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells, and Tfh cells. However, the absence of LCs does not affect the generation of protective immunity in ECL. Are LCs really “sufficient but not necessary” for protective immunity? Most of the studies involved in the decoding of LCs function in ECL have been performed under standardized conditions such as defined parasite numbers, sterile needle injection and animal housing under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions (21, 27–29). This standardization is crucial to compare data between studies and in terms of reproducibility, but have we underestimated some vector-associated important factors while decrypting the function of LCs in ECL?

This question is more than justified, because all metazoans coexist intimately with a community of commensal microorganisms (44). Sand flies can harbour fungi, bacteria and viruses (44). In addition, there are sand fly-associated components, such as the saliva and others, that can also influence immune cells (45). The elaboration of all these “vector additives” in ECL is very ambitious. We nonetheless are of the opinion that these factors, most prominent the microbiota-associated side effects, should not be ignored while decrypting the function of LCs in ECL. Given the fact that L. major parasites are transmitted selectively by Phlebotomus (P.) papatasi (46), this vector-parasite constellation will be considered in the following paragraphs.

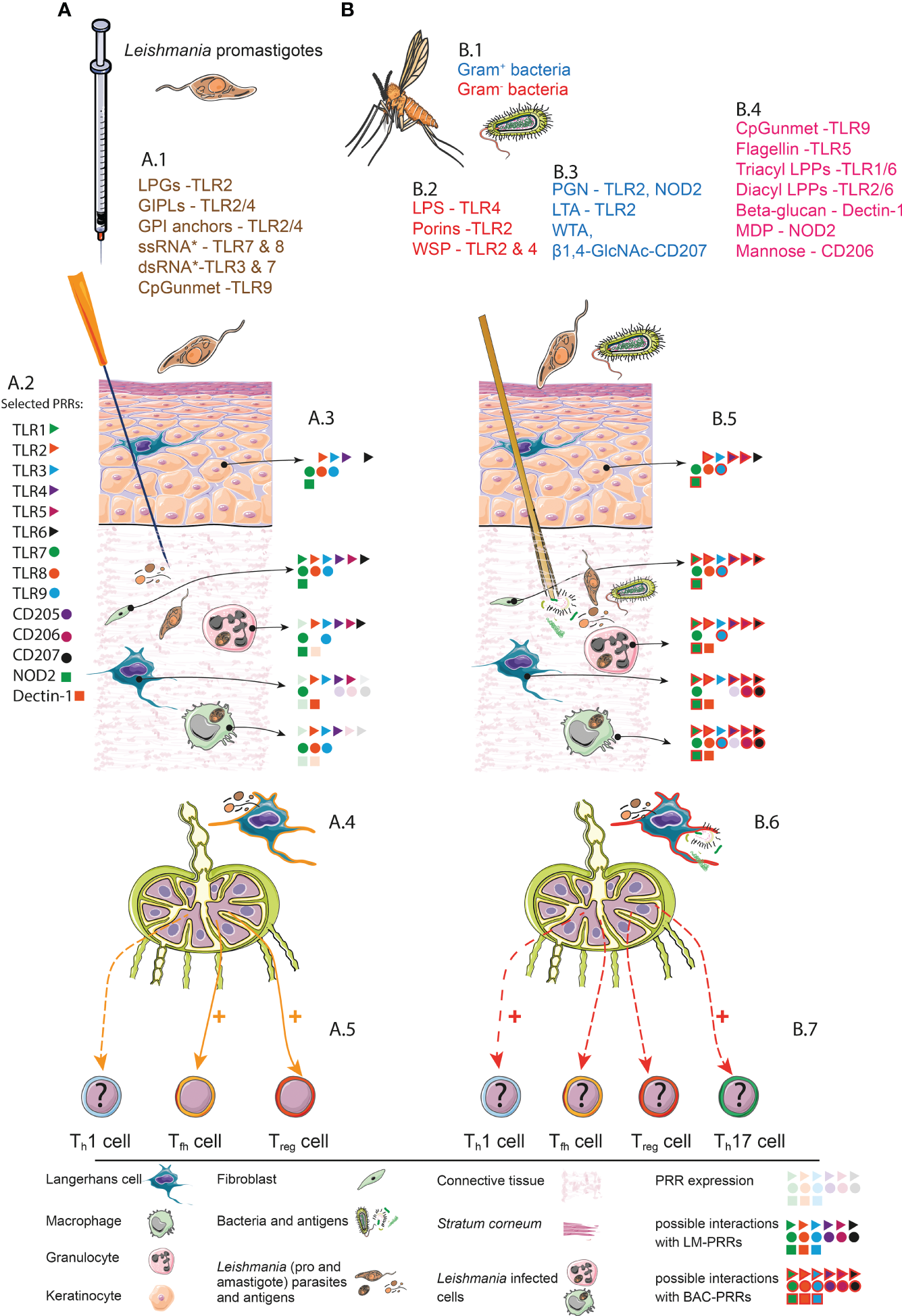

Comparable to the human gut microbiome (47), wild caught Phlebotomus species (sp.) host distinct microbiomes (2) (Figure 1B). During the blood meal of sand flies, gut microbes are egested into the skin - alongside with L. major parasites (89). This “multicomponent infection” triggers early inflammatory responses within the dermal compartment, such as inflammasome activation and neutrophil infiltration (89). The potential impact of microbes on innate and adaptive immunity in ECL has been already demonstrated. In this case, a needle infection of C57BL/6 mice using a combination of Staphylococcus (S.) aureus plus L. major (90) supports the recruitment of neutrophil granulocytes, γδ T cells, and IL-17 releasing Th17 cells to the dermal compartment (90). These microbiome-associated side effects seem beneficial for parasite replication and spreading, based on three reasons: First, L. major parasites have the ability to maintain infectivity in neutrophil granulocytes. Second, the parasites use granulocytes as “Trojan horses” before they enter their definitive host cells, the macrophages (91, 92). Third, IL-17 favours the recruitment of additional “Trojan horses” such as neutrophil granulocytes (93). This suggests that the inflammatory micro milieu mediated by S. aureus is responsible for exacerbating lesion development (90). Arthropod-associated microbiota might therefore represent “natural adjuvants” capable of catalysing parasite spreading. Whether functional capacities of LCs are also affected, needs to be analysed. Additionally, it remains speculative whether such an exacerbation of lesion development is crucial for long-lasting immunity.

Figure 1

Simplified synopsis of LC-functions in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Comparison of needle infection (A) and transmission by vectors (B). (A) Needle infection. A.1. Selected PAMPs of Leishmania parasites and their possible interactions with PRRs. *single strand (ss) RNA and *double strand (ds) RNA from Leishmania-associated viruses (48). A.2. Representative PRRs and assigned symbols. A.3. PRRs expression and interaction with Leishmania (LM)-PAMPs. Pale symbols represent PRRs that are expressed by the indicated cell subset. Solid symbols represent a possible interaction between PRRs and LM-PAMPs. Keratinocytes (49–53), Fibroblasts (54–58), TLR8 (54, 59), Neutrophil granulocytes (60–69), Epidermal Langerhans cells (24, 70–73). Dermal Macrophages (69, 74, 75). A.4. Migratory LC that has been primed in a sterile context (orange contour). This subset can present LM-derived antigens. A.5. LC-driven immune responses in skin-draining lymph nodes. Documented LC functions such as the induction (highlighted by “+”) of Tfh and Treg cells are highlighted with solid orange arrows. So far unclear (highlighted by “?”) involvement of LCs in Th1 cells differentiation is depicted with a dashed orange arrow. (B) Natural transmission. B.1. Gut microbiome of P. papatasi. Gram- bacteria: Wolbachia sp. (2), Klebsiella sp., Serratia sp., Stenotrophomonas gen., Thauera sp (76), Pseudomonas sp (77), Brevundimonas sp., Ochrobactrum gen (76). Gram+ bacteria: Spiroplasma sp (2) Staphylococcus sp., Micrococcus sp., Corynebacteriaceae sp. (2) Bacillus gen (78), Microbacteria gen (77). Gram+ or gram-Paenibacillus gen (2). B.2. PAMP/PRR-interactions of gram- bacteria (79–81). B.3. PAMP/PRR-interactions of gram+ bacteria (82–84). B.4. PAMP/PRR-interactions with bacterial components in general (68, 79, 85–88). B.5. PRRs expression and interaction with LM and bacterial (BAC) PAMPs. Pale symbols represent PRRs that are expressed by the indicated cell subset. Solid symbols represent a possible interaction between PRRs and LM-PAMPs. Solid symbols highlighted with red lines represent possible interactions with BAC-PAMPs. B.6. Migratory LC that has been primed in a nonsterile context (red contour). A presentation of BAC- as well as LM-derived antigens is possible. B.7. Putative (highlighted by “?”) LC-driven immune responses in SDLNs. The LC-driven Th1 and/or Th17 immune responses might be enhanced (+) by LCs that has been primed in a nonsterile context (solid red arrow). Whether LCs still prime Leishmania-specific Treg or Tfh cell subsets under nonsterile conditions remains speculative (dashed red arrow). It is possible that LCs fulfill novel functions if conditioned within a nonsterile microenvironment such as the induction of Th17 and Th1 cells. All components and symbols are explained by the legend below the figure. LPG, Lipophosphoglycan; GIPLs, glycoinositolphospholipids; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; CpG, cytosine-phosphate-guanine; unmet, unmethylated; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; WSP, Wolbachia surface protein; PGN, peptidoglycan; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; WTA, wall teichoic acid; β1,4-GlcNAc, β 1,4-N-acetyl glucosamine; LPP, lipoprotein; NOD, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; MDP, muramyl dipeptide; LM, Leishmania; BAC, Bacteria; PRR, pattern recognition receptors.

Given the fact that most cell types at the infection site including LCs, dermal macrophages and keratinocytes, are equipped with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), capable of sensing the bacterial PAMPs (Figure 1A), it is plausible that microbiota-associated PAMPs strongly influence adaptive immunity in ECL (Figure 1B). For instance, application of isolated PRR ligands, in parallel to Leishmania parasites or antigens, displayed beneficial effects. In addition, C57BL/6 mice treated intradermally with L. major and the TLR9 ligand CpG oligodeoxynucleotides developed little or no dermal lesions (94) and the treatment of BALB/c mice with L-Ag fractions plus the NOD2 ligand muramyl dipeptide induced resistance against cutaneous leishmaniasis (85). Moreover, an administration of the TLR2/TLR6 agonist BPPcysMPEG in combination with fixed L. major parasites protected BALB/c mice against L. major infection (95). Based on these and other data, it is obvious that arthropod microbiota might represent important additional parameters in orchestrating immunity in ECL (96, 97) (Figure 1).

Conceivable Impact of Arthropod-Associated Microbiota on LC Functions in ECL

LCs and other cells associated to the SALT are equipped with PRRs sensing microbial PAMPs (Figure 1). It is obvious that LCs must get in contact with bacterial compounds during the blood meal of vectors, harbouring microbiota and Leishmania parasites. In this context, LCs will be “stimulated” by PAMPs based on the expression of the corresponding PRRs (compare Figure 1B). Additionally epidermal LCs, while migrating through the dermal compartment, will be exposed to a micromilieu of soluble factors including cytokines, chemokines and other metabolites, that are released by keratinocytes or other dermal immune cells in response to microbial compounds. This natural Leishmania-infection, in the presence of additional vector-derived microbes, is might be capable to modify the transcriptome and proteome of LCs. The consequence remains still speculative. Many scenarios are conceivable based on the given expression PRRs and immune receptors sensing the environment. Here just one example: After PRR-ligation, LCs can release cytokines such as IL-17 (98), IL-12 (49) and TNF-alpha (99) - known to support Th-cell polarization and LC maturation programs (99). Consequently, it is feasible that LCs might lose their “tolerogenic capacity” (23, 32) and support Th-cell programs, resulting in adaptive immunity against L. major parasites (Figure 1B).

Conclusion

It is very likely that LCs can support so far unknown immunological programs in the presence of distinct sand fly-associated factors. Up to now, no systematic studies have been performed comparing the immunological attributes of LCs under “microbiome-free” and “microbiome-containing” sand fly or syringe conditions. In our opinion, these aspects need to be deciphered to understand the role of LCs in adaptive immunity and the generation of long-lasting immunological memory in detail. This understanding is pivotal for the improvement of alternative rationally designed vaccination strategies, using novel vector-associated “natural” microbial adjuvants. This new studies are more than overdue based on two aspects: First, L-Ag plus classical adjuvants such as CpG does not protect mice from ECL after challenge with infected sand flies (100). Second, people living in endemic areas seem to be “vaccinated” by multiple sand fly bites in the absence of clinical symptoms of ECL (101). Let’s get started to decrypt the impact of LCs in ECL under more physiological conditions.

Funding

The study was supported by the Bavarian Research Network (bayresq.net; Bavarian State Ministry for Science and the Arts, UR, MF, AG, and DD).

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

Conceptualization and investigation, UR. Writing – Original Draft, UR. Writing – Review & Editing, BN, MF, AG, DD. Visualization, UR and BN. Funding Acquisition, UR, MF, AG, and DD. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Ingeborg Becker (Centro de Medicina Tropical, Unidad de Medicina Experimental, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico) for helpful discussions and Lisa Schmidleithner (Department for Immunology, LIT - Leibniz Institute for Immunotherapy - Universitätsklinikum Regensburg Franz-Josef-Strauß-Allee 11, 93053 Regensburg) and Jordan Hartley (Department for Gene-Immunotherapy, LIT) for critical reading of the manuscript. Graphic abstract illustratiion credits from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), reproduced under Creative Commons License attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Nguyen AV Soulika AM . The Dynamics of the Skin’s Immune System. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20(8). doi: 10.3390/ijms20081811

2

Papadopoulos C Karas PA Vasileiadis S Ligda P Saratsis A Sotiraki S et al . Host Species Determines the Composition of the Prokaryotic Microbiota in Phlebotomus Sandflies. Pathogens (2020) 9(6):1–15. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9060428

3

Ritter U . Presentation of Skin-Derived Leishmania Antigen by Dendritic Cell Subtypes. In: JirilloE, editor. Immune Response to Parasitic Infections. 1Saif Zone Sharjah: Bentham e-Books (2010). p. 123–36 (14). doi: 10.2174/978160805148911001010123

4

Bogdan C Rollinghoff M . The Immune Response to Leishmania: Mechanisms of Parasite Control and Evasion. Int J Parasitol (1998) 28(1):121–34. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00169-0

5

Rosbjerg A Genster N Pilely K Garred P . Evasion Mechanisms Used by Pathogens to Escape the Lectin Complement Pathway. Front Microbiol (2017) 8:868. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00868

6

Sacks D Sher A . Evasion of Innate Immunity by Parasitic Protozoa. Nat Immunol (2002) 3(11):1041–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-1041

7

Kautz-Neu K Schwonberg K Fischer MR Schermann AI von Stebut E . Dendritic Cells in Leishmania Major Infections: Mechanisms of Parasite Uptake, Cell Activation and Evidence for Physiological Relevance. Med Microbiol Immunol (2012) 201(4):581–92. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0261-2

8

Kaye P Scott P . Leishmaniasis: Complexity at the Host-Pathogen Interface. Nat Rev Microbiol (2011) 9(8):604–15. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2608

9

Streilein JW . Skin-Associated Lymphoid Tissues (Salt): Origins and Functions. J Invest Dermatol (1983) 80 Suppl:12s–6s. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12536743

10

Scott P Novais FO . Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Immune Responses in Protection and Pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol (2016) 16(9):581–92. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.72

11

Heinzel FP Sadick MD Holaday BJ Coffman RL Locksley RM . Reciprocal Expression of Interferon Gamma or Interleukin 4 During the Resolution or Progression of Murine Leishmaniasis. Evidence for Expansion of Distinct Helper T Cell Subsets. J Exp Med (1989) 169(1):59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59

12

Scott P Natovitz P Coffman RL Pearce E Sher A . Immunoregulation of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. T Cell Lines That Transfer Protective Immunity or Exacerbation Belong to Different T Helper Subsets and Respond to Distinct Parasite Antigens. J Exp Med (1988) 168(5):1675–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1675

13

Goncalves R Zhang X Cohen H Debrabant A Mosser DM . Platelet Activation Attracts a Subpopulation of Effector Monocytes to Sites of Leishmania Major Infection. J Exp Med (2011) 208(6):1253–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101751

14

Heinzel FP Schoenhaut DS Rerko RM Rosser LE Gately MK . Recombinant Interleukin 12 Cures Mice Infected With Leishmania Major. J Exp Med (1993) 177(5):1505–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1505

15

Sypek JP Chung CL Mayor SE Subramanyam JM Goldman SJ Sieburth DS et al . Resolution of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Interleukin 12 Initiates a Protective T Helper Type 1 Immune Response. J Exp Med (1993) 177(6):1797–802. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1797

16

Chatelain R Varkila K Coffman RL . Il-4 Induces a Th2 Response in Leishmania Major-Infected Mice. J Immunol (1992) 148(4):1182–7.

17

Will A Blank C Rollinghoff M Moll H . Murine Epidermal Langerhans Cells Are Potent Stimulators of an Antigen-Specific T Cell Response to Leishmania Major, The Cause of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol (1992) 22(6):1341–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220603

18

Moll H Fuchs H Blank C Rollinghoff M . Langerhans Cells Transport Leishmania Major From the Infected Skin to the Draining Lymph Node for Presentation to Antigen-Specific T Cells. Eur J Immunol (1993) 23(7):1595–601. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230730

19

Flohe SB Bauer C Flohe S Moll H . Antigen-Pulsed Epidermal Langerhans Cells Protect Susceptible Mice From Infection With the Intracellular Parasite Leishmania Major. Eur J Immunol (1998) 28(11):3800–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3800::AID-IMMU3800>3.0.CO;2-0

20

von Stebut E Belkaid Y Jakob T Sacks DL Udey MC . Uptake of Leishmania Major Amastigotes Results in Activation and Interleukin 12 Release From Murine Skin-Derived Dendritic Cells: Implications for the Initiation of Anti-Leishmania Immunity. J Exp Med (1998) 188(8):1547–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1547

21

von Stebut E Belkaid Y Nguyen BV Cushing M Sacks DL Udey MC . Leishmania Major-Infected Murine Langerhans Cell-Like Dendritic Cells From Susceptible Mice Release Il-12 After Infection and Vaccinate Against Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol (2000) 30(12):3498–506. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000012)30:12<3498::AID-IMMU3498>3.0.CO;2-6

22

Romani N Brunner PM Stingl G . Changing Views of the Role of Langerhans Cells. J Invest Dermatol (2012) 132(3 Pt 2):872–81. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.437

23

Moreno J . Changing Views on Langerhans Cell Functions in Leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol (2007) 23(3):86–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.01.002

24

Kaplan DH . In Vivo Function of Langerhans Cells and Dermal Dendritic Cells. Trends Immunol (2010) 31(12):446–51. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.08.006

25

Doebel T Voisin B Nagao K . Langerhans Cells - the Macrophage in Dendritic Cell Clothing. Trends Immunol (2017) 38(11):817–28. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.06.008

26

Soares H Waechter H Glaichenhaus N Mougneau E Yagita H Mizenina O et al . A Subset of Dendritic Cells Induces Cd4+ T Cells to Produce Ifn-Gamma by an Il-12-Independent But Cd70-Dependent Mechanism in Vivo. J Exp Med (2007) 204(5):1095–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070176

27

Ritter U Meissner A Scheidig C Korner H . Cd8 Alpha- and Langerin-Negative Dendritic Cells, But Not Langerhans Cells, Act as Principal Antigen-Presenting Cells in Leishmaniasis. Eur J Immunol (2004) 34(6):1542–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324586

28

Kautz-Neu K Noordegraaf M Dinges S Bennett CL John D Clausen BE et al . Langerhans Cells Are Negative Regulators of the Anti-Leishmania Response. J Exp Med (2011) 208(5):885–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102318

29

Brewig N Kissenpfennig A Malissen B Veit A Bickert T Fleischer B et al . Priming of Cd8+ and Cd4+ T Cells in Experimental Leishmaniasis Is Initiated by Different Dendritic Cell Subtypes. J Immunol (2009) 182(2):774–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.774

30

Merad M Ginhoux F Collin M . Origin, Homeostasis and Function of Langerhans Cells and Other Langerin-Expressing Dendritic Cells. Nat Rev Immunol (2008) 8(12):935–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2455

31

Bennett CL Clausen BE . Dc Ablation in Mice: Promises, Pitfalls, and Challenges. Trends Immunol (2007) 28(12):525–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.08.011

32

Ritter U Osterloh A . A New View on Cutaneous Dendritic Cell Subsets in Experimental Leishmaniasis. Med Microbiol Immunol (2007) 196(1):51–9. doi: 10.1007/s00430-006-0023-0

33

Weiss R Scheiblhofer S Thalhamer J Bickert T Richardt U Fleischer B et al . Epidermal Inoculation of Leishmania-Antigen by Gold Bombardment Results in a Chronic Form of Leishmaniasis. Vaccine (2007) 25(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.044

34

Jankovic D Kullberg MC Feng CG Goldszmid RS Collazo CM Wilson M et al . Conventional T-Bet(+)Foxp3(-) Th1 Cells Are the Major Source of Host-Protective Regulatory Il-10 During Intracellular Protozoan Infection. J Exp Med (2007) 204(2):273–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175

35

Shibaki A Sato A Vogel JC Miyagawa F Katz SI . Induction of Gvhd-Like Skin Disease by Passively Transferred Cd8(+) T-Cell Receptor Transgenic T Cells Into Keratin 14-Ovalbumin Transgenic Mice. J Invest Dermatol (2004) 123(1):109–15. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22701.x

36

Luo Y Wang S Liu X Wen H Li W Yao X . Langerhans Cells Mediate the Skin-Induced Tolerance to Ovalbumin Via Langerin in a Murine Model. Allergy (2019) 74(9):1738–47. doi: 10.1111/all.13813

37

Clayton K Vallejo AF Davies J Sirvent S Polak ME . Langerhans Cells-Programmed by the Epidermis. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1676. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01676

38

Zimara N Florian C Schmid M Malissen B Kissenpfennig A Mannel DN et al . Langerhans Cells Promote Early Germinal Center Formation in Response to Leishmania-Derived Cutaneous Antigens. Eur J Immunol (2014) 44(10):2955–67. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344263

39

Kervevan J Bouteau A Lanza JS Hammoudi A Zurawski S Surenaud M et al . Targeting Human Langerin Promotes Hiv-1 Specific Humoral Immune Responses. PloS Pathog (2021) 17(7):e1009749. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009749

40

Levin C Bonduelle O Nuttens C Primard C Verrier B Boissonnas A et al . Critical Role for Skin-Derived Migratory Dcs and Langerhans Cells in Tfh and Gc Responses After Intradermal Immunization. J Invest Dermatol (2017) 137(9):1905–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.04.016

41

Vardam T Anandasabapathy N . Langerhans Cells Orchestrate Tfh-Dependent Humoral Immunity. J Invest Dermatol (2017) 137(9):1826–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.014

42

Marschall P Wei R Segaud J Yao W Hener P German BF et al . Dual Function of Langerhans Cells in Skin Tslp-Promoted Tfh Differentiation in Mouse Atopic Dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2021) 147(5):1778–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.006

43

Woelbing F Kostka SL Moelle K Belkaid Y Sunderkoetter C Verbeek S et al . Uptake of Leishmania Major by Dendritic Cells Is Mediated by Fcgamma Receptors and Facilitates Acquisition of Protective Immunity. J Exp Med (2006) 203(1):177–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052288

44

Telleria EL Martins-da-Silva A Tempone AJ Traub-Cseko YM . Leishmania, Microbiota and Sand Fly Immunity. Parasitology (2018) 145(10):1336–53. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018001014

45

Lima HC Titus RG . Effects of Sand Fly Vector Saliva on Development of Cutaneous Lesions and the Immune Response to Leishmania Braziliensis in Balb/C Mice. Infect Immun (1996) 64(12):5442–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5442-5445.1996

46

Dobson DE Kamhawi S Lawyer P Turco SJ Beverley SM Sacks DL . Leishmania Major Survival in Selective Phlebotomus Papatasi Sand Fly Vector Requires a Specific Scg-Encoded Lipophosphoglycan Galactosylation Pattern. PloS Pathog (2010) 6(11):e1001185. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001185

47

Lozupone CA Stombaugh JI Gordon JI Jansson JK Knight R . Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nature (2012) 489(7415):220–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11550

48

Chauhan P Shukla D Chattopadhyay D Saha B . Redundant and Regulatory Roles for Toll-Like Receptors in Leishmania Infection. Clin Exp Immunol (2017) 190(2):167–86. doi: 10.1111/cei.13014

49

Sun L Liu W Zhang LJ . The Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Skin Host Defense, Psoriasis, and Atopic Dermatitis. J Immunol Res (2019) 2019:1824624. doi: 10.1155/2019/1824624

50

Stremnitzer C Manzano-Szalai K Willensdorfer A Starkl P Pieper M Konig P et al . Papain Degrades Tight Junction Proteins of Human Keratinocytes in Vitro and Sensitizes C57bl/6 Mice Via the Skin Independent of Its Enzymatic Activity or Tlr4 Activation. J Invest Dermatol (2015) 135(7):1790–800. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.58

51

Crain B Yao S Keophilaone V Promessi V Kang M Barberis A et al . Inhibition of Keratinocyte Proliferation by Phospholipid-Conjugates of a Tlr7 Ligand in a Myc-Induced Hyperplastic Actinic Keratosis Model in the Absence of Systemic Side Effects. Eur J Dermatol (2013) 23(5):618–28. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2155

52

Sugita K Kabashima K Atarashi K Shimauchi T Kobayashi M Tokura Y . Innate Immunity Mediated by Epidermal Keratinocytes Promotes Acquired Immunity Involving Langerhans Cells and T Cells in the Skin. Clin Exp Immunol (2007) 147(1):176–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03258.x

53

Muller-Anstett MA Muller P Albrecht T Nega M Wagener J Gao Q et al . Staphylococcal Peptidoglycan Co-Localizes With Nod2 and Tlr2 and Activates Innate Immune Response Via Both Receptors in Primary Murine Keratinocytes. PloS One (2010) 5(10):e13153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013153

54

Rodriguez-Martinez S Cancino-Diaz ME Jimenez-Zamudio L Garcia-Latorre E Cancino-Diaz JC . Tlrs and Nods Mrna Expression Pattern in Healthy Mouse Eye. Br J Ophthalmol (2005) 89(7):904–10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.056218

55

Satta N Dunoyer-Geindre S Reber G Fish RJ Boehlen F Kruithof EK et al . The Role of Tlr2 in the Inflammatory Activation of Mouse Fibroblasts by Human Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Blood (2007) 109(4):1507–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-024463

56

Yu FY Xie CQ Jiang CL Sun JT Huang XW . Tnfalpha Increases Inflammatory Factor Expression in Synovial Fibroblasts Through the Tolllike Receptor3mediated Erk/Akt Signaling Pathway in a Mouse Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Mol Med Rep (2018) 17(6):8475–83. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8897

57

Jung YO Cho ML Lee SY Oh HJ Park JS Park MK et al . Synergism of Toll-Like Receptor 2 (Tlr2), Tlr4, and Tlr6 Ligation on the Production of Tumor Necrosis Factor (Tnf)-Alpha in a Spontaneous Arthritis Animal Model of Interleukin (Il)-1 Receptor Antagonist-Deficient Mice. Immunol Lett (2009) 123(2):138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.03.004

58

Green BB Kandasamy S Elsasser TH Kerr DE . The Use of Dermal Fibroblasts as a Predictive Tool of the Toll-Like Receptor 4 Response Pathway and Its Development in Holstein Heifers. J Dairy Sci (2011) 94(11):5502–14. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4441

59

Hergert B Grambow E Butschkau A Vollmar B . Effects of Systemic Pretreatment With Cpg Oligodeoxynucleotides on Skin Wound Healing in Mice. Wound Repair Regener (2013) 21(5):723–9. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12084

60

Ding R Xu G Feng Y Zou L Chao W . Lipopeptide Pam3cys4 Synergizes N-Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (Fmlp)-Induced Calcium Transients in Mouse Neutrophils. Shock (2018) 50(4):493–9. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001062

61

Deng T Feng X Liu P Yan K Chen Y Han D . Toll-Like Receptor 3 Activation Differentially Regulates Phagocytosis of Bacteria and Apoptotic Neutrophils by Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages. Immunol Cell Biol (2013) 91(1):52–9. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.45

62

Wang Y Du F Hawez A Morgelin M Thorlacius H . Neutrophil Extracellular Trap-Microparticle Complexes Trigger Neutrophil Recruitment Via High-Mobility Group Protein 1 (Hmgb1)-Toll-Like Receptors(Tlr2)/Tlr4 Signalling. Br J Pharmacol (2019) 176(17):3350–63. doi: 10.1111/bph.14765

63

Shibata T Takemura N Motoi Y Goto Y Karuppuchamy T Izawa K et al . Prat4a-Dependent Expression of Cell Surface Tlr5 on Neutrophils, Classical Monocytes and Dendritic Cells. Int Immunol (2012) 24(10):613–23. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs068

64

Bellocchio S Moretti S Perruccio K Fallarino F Bozza S Montagnoli C et al . Tlrs Govern Neutrophil Activity in Aspergillosis. J Immunol (2004) 173(12):7406–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7406

65

Regli IB Passelli K Martinez-Salazar B Amore J Hurrell BP Muller AJ et al . Tlr7 Sensing by Neutrophils Is Critical for the Control of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Cell Rep (2020) 31(10):107746. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107746

66

Prince LR Whyte MK Sabroe I Parker LC . The Role of Tlrs in Neutrophil Activation. Curr Opin Pharmacol (2011) 11(4):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.06.007

67

Jeong YJ Kang MJ Lee SJ Kim CH Kim JC Kim TH et al . Nod2 and Rip2 Contribute to Innate Immune Responses in Mouse Neutrophils. Immunology (2014) 143(2):269–76. doi: 10.1111/imm.12307

68

Goodridge HS Wolf AJ Underhill DM . Beta-Glucan Recognition by the Innate Immune System. Immunol Rev (2009) 230(1):38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00793.x

69

Taylor PR Brown GD Reid DM Willment JA Martinez-Pomares L Gordon S et al . The Beta-Glucan Receptor, Dectin-1, Is Predominantly Expressed on the Surface of Cells of the Monocyte/Macrophage and Neutrophil Lineages. J Immunol (2002) 169(7):3876–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3876

70

van der Aar AM Picavet DI Muller FJ de Boer L van Capel TM Zaat SA et al . Langerhans Cells Favor Skin Flora Tolerance Through Limited Presentation of Bacterial Antigens and Induction of Regulatory T Cells. J Invest Dermatol (2013) 133(5):1240–9. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.500

71

Becerril-Garcia MA Yam-Puc JC Maqueda-Alfaro R Beristain-Covarrubias N Heras-Chavarria M Gallegos-Hernandez IA et al . Langerhans Cells From Mice at Birth Express Endocytic- and Pattern Recognition-Receptors, Migrate to Draining Lymph Nodes Ferrying Antigen and Activate Neonatal T CellsIn Vivo. Front Immunol (2020) 11:744. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00744

72

Shrimpton RE Butler M Morel AS Eren E Hue SS Ritter MA . Cd205 (Dec-205): A Recognition Receptor for Apoptotic and Necrotic Self. Mol Immunol (2009) 46(6):1229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.11.016

73

Donadei A Gallorini S Berti F O’Hagan DT Adamo R Baudner BC . Rational Design of Adjuvant for Skin Delivery: Conjugation of Synthetic Beta-Glucan Dectin-1 Agonist to Protein Antigen. Mol Pharm (2015) 12(5):1662–72. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00072

74

Ley K Pramod AB Croft M Ravichandran KS Ting JP . How Mouse Macrophages Sense What Is Going on. Front Immunol (2016) 7:204. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00204

75

Corbett Y Parapini S D’Alessandro S Scaccabarozzi D Rocha BC Egan TJ et al . Involvement of Nod2 in the Innate Immune Response Elicited by Malarial Pigment Hemozoin. Microbes Infect (2015) 17(3):184–94. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.11.001

76

Karakus M Karabey B Orcun Kalkan S Ozdemir G Oguz G Erisoz Kasap O et al . Midgut Bacterial Diversity of Wild Populations of Phlebotomus (P.) Papatasi, the Vector of Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (Zcl) in Turkey. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):14812. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13948-2

77

Maleki-Ravasan N Oshaghi MA Afshar D Arandian MH Hajikhani S Akhavan AA et al . Aerobic Bacterial Flora of Biotic and Abiotic Compartments of a Hyperendemic Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (Zcl) Focus. Parasit Vectors (2015) 8:63. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0517-3

78

Mukhopadhyay J Braig HR Rowton ED Ghosh K . Naturally Occurring Culturable Aerobic Gut Flora of Adult Phlebotomus Papatasi, Vector of Leishmania Major in the Old World. PloS One (2012) 7(5):e35748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035748

79

Mogensen TH . Pathogen Recognition and Inflammatory Signaling in Innate Immune Defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev (2009) 22(2):240–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08

80

Brattig NW Buttner DW Hoerauf A . Neutrophil Accumulation Around Onchocerca Worms and Chemotaxis of Neutrophils Are Dependent on Wolbachia Endobacteria. Microbes Infect (2001) 3(6):439–46. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01399-5

81

Brattig NW Bazzocchi C Kirschning CJ Reiling N Buttner DW Ceciliani F et al . The Major Surface Protein of Wolbachia Endosymbionts in Filarial Nematodes Elicits Immune Responses Through Tlr2 and Tlr4. J Immunol (2004) 173(1):437–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.437

82

Wolf AJ Underhill DM . Peptidoglycan Recognition by the Innate Immune System. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18(4):243–54. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.136

83

van Dalen R de la Cruz Diaz JS Rumpret M Fuchsberger FF van Teijlingen NH Hanske J et al . Langerhans Cells Sense Staphylococcus Aureus Wall Teichoic Acid Through Langerin to Induce Inflammatory Responses. mBio (2019) 10(3):1–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00330-19

84

Jawdat DM Rowden G Marshall JS . Mast Cells Have a Pivotal Role in Tnf-Independent Lymph Node Hypertrophy and the Mobilization of Langerhans Cells in Response to Bacterial Peptidoglycan. J Immunol (2006) 177(3):1755–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1755

85

Ogunkolade BW Monjour L Vouldoukis I Rhodes-Feuillette A Frommel D . Inoculation of Balb/C Mice Against Leishmania Major Infection With Leishmania-Derived Antigens Isolated by Gel Filtration. J Chromatogr (1988) 440:459–65. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)94550-3

86

Ryu S Song PI Seo CH Cheong H Park Y . Colonization and Infection of the Skin by S. Aureus: Immune System Evasion and the Response to Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides. Int J Mol Sci (2014) 15(5):8753–72. doi: 10.3390/ijms15058753

87

Grady EN MacDonald J Liu L Richman A Yuan ZC . Current Knowledge and Perspectives of Paenibacillus: A Review. Microb Cell Fact (2016) 15(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0603-7

88

Watanabe T Asano N Murray PJ Ozato K Tailor P Fuss IJ et al . Muramyl Dipeptide Activation of Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerization Domain 2 Protects Mice From Experimental Colitis. J Clin Invest (2008) 118(2):545–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI33145

89

Dey R Joshi AB Oliveira F Pereira L Guimaraes-Costa AB Serafim TD et al . Gut Microbes Egested During Bites of Infected Sand Flies Augment Severity of Leishmaniasis Via Inflammasome-Derived Il-1beta. Cell Host Microbe (2018) 23(1):134–43 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.002

90

Borbon TY Scorza BM Clay GM Lima Nobre de Queiroz F Sariol AJ Bowen JL et al . Coinfection With Leishmania Major and Staphylococcus Aureus Enhances the Pathologic Responses to Both Microbes Through a Pathway Involving Il-17a. PloS Negl Trop Dis (2019) 13(5):e0007247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007247

91

Laskay T van Zandbergen G Solbach W . Neutrophil Granulocytes–Trojan Horses for Leishmania Major and Other Intracellular Microbes? Trends Microbiol (2003) 11(5):210–4. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00075-1

92

Ritter U Frischknecht F van Zandbergen G . Are Neutrophils Important Host Cells for Leishmania Parasites? Trends Parasitol (2009) 25(11):505–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.08.003

93

Goncalves-de-Albuquerque SDC Pessoa ESR Trajano-Silva LAM de Goes TC de Morais RCS da COCN et al . The Equivocal Role of Th17 Cells and Neutrophils on Immunopathogenesis of Leishmaniasis. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1437. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01437

94

Wu W Weigand L Belkaid Y Mendez S . Immunomodulatory Effects Associated With a Live Vaccine Against Leishmania Major Containing Cpg Oligodeoxynucleotides. Eur J Immunol (2006) 36(12):3238–47. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636472

95

Pandey SP Chandel HS Srivastava S Selvaraj S Jha MK Shukla D et al . Pegylated Bisacycloxypropylcysteine, a Diacylated Lipopeptide Ligand of Tlr6, Plays a Host-Protective Role Against Experimental Leishmania Major Infection. J Immunol (2014) 193(7):3632–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400672

96

Oliveira MR Tafuri WL Afonso LC Oliveira MA Nicoli JR Vieira EC et al . Germ-Free Mice Produce High Levels of Interferon-Gamma in Response to Infection With Leishmania Major But Fail to Heal Lesions. Parasitology (2005) 131(Pt 4):477–88. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005008073

97

Lopes ME Dos Santos LM Sacks D Vieira LQ Carneiro MB . Resistance Against Leishmania Major Infection Depends on Microbiota-Guided Macrophage Activation. Front Immunol (2021) 12:730437. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.730437

98

Igyarto BZ Haley K Ortner D Bobr A Gerami-Nejad M Edelson BT et al . Skin-Resident Murine Dendritic Cell Subsets Promote Distinct and Opposing Antigen-Specific T Helper Cell Responses. Immunity (2011) 35(2):260–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.005

99

Sumpter TL Balmert SC Kaplan DH . Cutaneous Immune Responses Mediated by Dendritic Cells and Mast Cells. JCI Insight (2019) 4(1):1–13. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123947

100

Peters NC Bertholet S Lawyer PG Charmoy M Romano A Ribeiro-Gomes FL et al . Evaluation of Recombinant Leishmania Polyprotein Plus Glucopyranosyl Lipid a Stable Emulsion Vaccines Against Sand Fly-Transmitted Leishmania Major in C57bl/6 Mice. J Immunol (2012) 189(10):4832–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201676

101

Kamhawi S Belkaid Y Modi G Rowton E Sacks D . Protection Against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Resulting From Bites of Uninfected Sand Flies. Science (2000) 290(5495):1351–4. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5495.1351

Summary

Keywords

Langerhans cells, dendritic cells, microbiome, skin, experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis, T cell-mediated immunity, lymph node

Citation

Nerb B, Dudziak D, Gessner A, Feuerer M and Ritter U (2022) Have We Ignored Vector-Associated Microbiota While Characterizing the Function of Langerhans Cells in Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis?. Front. Trop. Dis 3:874081. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2022.874081

Received

11 February 2022

Accepted

04 April 2022

Published

30 June 2022

Volume

3 - 2022

Edited by

Laís Amorim Sacramento, University of Pennsylvania, United States

Reviewed by

Esther Von Stebut, University of Cologne, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Nerb, Dudziak, Gessner, Feuerer and Ritter.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Uwe Ritter, uwe.ritter@ukr.de

This article was submitted to Neglected Tropical Diseases, a section of the journal Frontiers in Tropical Diseases

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.