Abstract

Introduction:

Rabies remains a public health and veterinary concern, with both animal and human cases regularly documented. To gain insight into the rise and persistence of rabies in Tunisia, a comprehensive retrospective study was conducted from 1994 to 2023.

Methods:

The total number of animal cases recorded over this period was 6 920, with 90 human cases also documented. Analysis of data included species distribution, temporal patterns, and spatial dynamics. To assess the temporal distribution of dog rabies at larger scale, we applied a Markov-Switching Autoregressive (MS-AR) model to the annual time series of canine rabies cases from 1961 to 2023. The spatial distribution of the disease was examined using Anselin's Local Moran's I index applied at the governorate level.

Results:

Analysis of data showed that dogs accounted for 61.9% of the total confirmed rabies cases, with ruminants (24% of the cases) being the victims of bites from rabid dogs. Comparison between months indicated that the occurrence of dog rabies was more frequent during the months of March, April and May. The MS-AR model indicates the presence of two patterns: a low transmission pattern (average of 83.4 cases per year) and a high transmission pattern (average of 218.0 cases per year). The probability of persistence in each regime was estimated as moderate (50.0% for “low” and 62.1% for “high”), with average episode durations of 2.0 and 2.6 years, respectively. The country has been in an unprecedented 12-year phase of high transmission since 2012, which suggests an important change in the profile of the disease in Tunisia. The spatial distribution of the disease indicated that cases moved from a governorate to another over time. Anselin's Local Moran's I index reveals that areas of significant clustering (High-High) regularly extended in the north-east and north-west of the country. The incidence of human rabies varied significantly among the different regions (governorates) of the country.

Discussion:

The findings of this study highlight the urgency of revising current rabies control strategies considering the unprecedented 12-year high-transmission phase since 2012. Strengthening public awareness, optimizing resource allocation, and establishing integrated One Health rabies task forces in high-risk governorates are critical steps toward interrupting the persistence and transmission of rabies in Tunisia.

Introduction

Rabies is a viral infectious disease caused by the Lyssavirus genus of the Rhabdoviridae family (1). The virus is transmitted to mammals generally by bite or scratch from an infected animal via saliva contact on damaged tissue (2). Before the advance of the rabies vaccine by Louis Pasteur, no effective preventive or curative treatment existed (3). It is well-known that the disease is almost always fatal in both humans and animals once clinical symptoms manifest (4). This significant zoonotic disease is widely distributed across the globe, with the exception of Antarctica and a number of islands, including the United Kingdom, Ireland, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, which are regarded as being free of the disease (5). The prevalence of rabies in humans and domestic animals is higher in economically disadvantaged regions, particularly in Africa and Asia. Africa indeed accounts for 43% of all human rabies deaths, with over 95% of these fatalities caused by virus transmission through bites from rabid dogs (6). In North African countries, rabies is enzootic and the domestic dog acts as both reservoir and main vector of the disease (7, 8). In Tunisia, the disease with endemic status causes one or two human fatalities per year and substantial livestock losses, despite the post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) that has been provided free of charge in the public sector (6, 9). Historically, the first cases of rabies, which occurred in 1870 in the capital (Tunis), were associated with the arrival of European migrants and other factors such as sociocultural and ecological changes (10). During the 1970s and 1980s, the increasing number of stray dogs led to a resurgence of animal rabies, with epidemics occurring in different regions of the country (10). Prior to 1982, an average of 265 rabies cases in animals were recorded each year, with 16 human cases (7). Nevertheless, human control of the disease precedes the control of the animal, and the Pasteur Institute was the reference center for PEP in Tunisia and the main institution responsible for treating persons who were exposed to the bites of suspected animals. During this period, the strategy for preventing human rabies underwent a significant change with the creation of a central veterinary public health unit. This unit decentralized treatment for those who had been bitten, trained vaccination agents, allocated a central budget, and improved data collection (11, 12). The first rabies control program based on dog vaccination campaigns was initiated in 1982 in collaboration with World Health Organization (WHO) experts (13). At this time, 282 cases were reported. This program relies mainly on the compulsory vaccination of owned dogs, which has been in place since 1987. This measure has been successful in controlling the disease and maintaining a very low prevalence (43 cases in 1987). However, in 1992, the incidence of rabies resumed its upward trend, leading to epizootic peaks (14). The authorities consequently adapted the control strategy, and the frequency of the vaccination campaigns was increased from one campaign every 2 years to an annual basis from 1992, with the objective to reach 70% vaccination coverage to control rabies (15). Despite control efforts, animal rabies has never ceased to circulate and has reached alarming prevalence levels in recent years (14).

In Tunisia, knowledge of the epidemiology of rabies is currently limited to general descriptions of how the disease changes over time and space. Previous studies have examined the structure and dynamics of the country’s canine population. The results showed that the renewal rate of this population varied between 30% and 40% and that dog densities differed significantly, depending on the area type (16). In rural areas, for example, the density of the canine population was estimated at 7 and 30 dogs per km2, whereas in urban and semi-urban areas, it ranged from 700 to 1,000 dogs per km2 (16). These studies provide important information for understanding the distribution and density of dogs in Tunisia. Previous studies have also shown that the risk of rabies in Tunisia varies over time and space. Bouslama et al. (17) used a spatiotemporal model to identify six clusters that appeared at different times. These clusters are distributed across the northern and north-eastern regions of Tunisia (14, 17), demonstrating that rabies is confined to the north and center of the country. Hotspot analyses revealed four clusters over the 4-year study period (2012–2015), primarily in the northern and central governorates (14). Even at the regional level, differences in the distribution of rabies cases were highlighted, and clusters were detected in the Nabeul governorate in northern Tunisia (18). Despite all these studies, these studies have not filled all the gaps. The long-term evolution of rabies should also be studied to gain an understanding of trends, identify any changes in disease prevalence, assess the effectiveness of control measures implemented over the years, and inform future strategies to combat and prevent rabies effectively. A wide variety of models can be used to explain diseases and their onset and spread, based on a set of variables. The complexity of the interactions they capture and the types of data they analyze determine the complexity of these models (19). The Markov switching autoregressive (MS-AR) model is one of the models that is increasingly used in veterinary epidemiology to identify latent disease regimes and quantify transitions between endemic and epidemic phases. This provides a more detailed view of the disease’s epidemiological evolution (20, 21).

Prior studies on rabies in Tunisia have described rabies clusters and seasonal patterns, but a comprehensive understanding of long-term transmission dynamics, particularly shifts between endemic and epidemic phases and their spatial drivers, is lacking. This study fills that gap by applying the MS-AR model to the 30-year surveillance data with the objective of providing insights into the epidemiological features and trends of rabies in Tunisia, with the intention of informing and improving disease management strategies.

Materials and methods

Study area

Tunisia is located in the northern part of the African continent. It is bordered to the north and east by the Mediterranean Sea, to the west by Algeria (965 km), and to the south-east by Libya (459 km). Spanning 165,000 km², Tunisia is divided into 24 governorates (administrative units), which are subdivided into 264 delegations. Its population was estimated to be 11,972,169 (2024 census; INS 2024, https://www.ins.tn/) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Localization of Tunisia in Africa and its governorates.

Rabies surveillance and control measures

In Tunisia, rabies is a notifiable disease, as indicated in Decree No. 2009–2200 of 14 July 2009, which establishes the nomenclature of regulated diseases and enacts the general measures applicable to them. Animal rabies surveillance is conducted through passive surveillance. All animals exhibiting clinical signs (e.g., bites, hypersalivation) or behavioral changes (e.g., paralysis, aggression, and altered vocalization) must be reported to the regional veterinary services (14), which are responsible for sending the samples to the laboratory. Human samples are sent to the laboratory through regional health directorates. Samples taken in cases of a valid suspicion are sent to the Pasteur Institute of Tunis (IPT), which is actually the only approved reference laboratory for rabies diagnosis in Tunisia in animals and humans (22). The routine techniques used in the post-mortem diagnosis of animal and human rabies are the direct fluorescent antibody test (dFAT), which detects the presence of rabies antigens in the brain tissue of tested animals (23, 24), and the rapid tissue culture infection test (RTCIT). The RT-PCR technique is the third technique used; it is practiced mainly for humans and occasionally for animal samples (25). These methods are all reference techniques recommended by the WHO and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) (26).

The rabies control program established in 1982 involved the Ministry of Public Health for the application of PEP and the collection of any human specimen for diagnosis, the Ministry of Agriculture for dog vaccination campaigns and the collection of any suspect animal for diagnosis, and the Ministry of the Interior for stray dog management (22, 27). Initially, in 1982, the program in animals was based on parenteral vaccination (one campaign every 2 years) and on the destruction of stray dogs (13, 28, 29). Vaccination campaigns were conducted at fixed vaccination posts in urban and suburban areas, and house-to-house campaigns were organized in rural areas. Vaccinated dogs were issued a certificate of vaccination but were not identified. Annual mass dog vaccination campaigns have been conducted each year since 1992 in the country. The timing of the campaign was adjusted over time, initially in May, June, and July and later moved to March to May (from 2012) to coincide with the school holidays and improve dog owner participation, and subsequently shifted to January, February, and March (from 2014), to avoid the possible impact of temperature and hot season on the quality of the vaccine (30). Inactivated anti-rabies vaccines are used. Vaccination is free and obligatory, and all dogs over 3 months of age should be vaccinated. Ring vaccination (euthanizing contaminated animals and control of free-roaming dogs under the supervision of the regional veterinary services) is also implemented to prevent secondary outbreaks. The number of dogs to be vaccinated per governorate is estimated by the veterinary services at the national level using parameters elaborated by Hans Matter (16). In parallel, PEP has been established in order to prevent the disease in humans (31).

Data collection and analysis

Retrospective epidemiological data on rabies in animals and humans were collected from the Archives of the Pasteur Institute of Tunis, the annual reports of the General Directorate of Veterinary Services (DGSV), and the WOAH database. In the event of conflicting information, the Institut Pasteur is considered the authoritative source. The dataset included information on animal species, geographical origin (governorate), rabies diagnosis outcome (positive or negative), and, for dogs, the month and year of case detection. Human rabies case data were also collected. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the total number of animal submissions, positivity rates, species distribution, and temporal trends for the data between 1994 and 2023 due to the completeness and reliability of both animal and human rabies records during this period. Percentages were calculated for categorical variables such as species affected and geographical distribution. The annual positivity rate was defined as the proportion of rabies-positive cases among all tested animal samples per year. Vaccination coverage was calculated annually at both the national and governorate levels, dividing the number of dogs vaccinated by the estimated dog population, expressed as a percentage. The estimated population was assessed by the national veterinary services using Hans Matter parameters that characterize the canine populations of various types of habitats (rural, semi-urban, and urban) (7). The target population to be vaccinated was based on official estimates from the Ministry of Agriculture. Moran’s local index of spatial autocorrelation (LISA) was conducted to identify both clusters and spatial outliers, and the Getis–Ord Gi statistic was applied to highlight statistically significant hotspots and coldspots (p < 0.05) for each 5-year period, respectively.

Markov switching models (regime switching analysis)

To identify underlying epidemiological regimes (≈ trends) over time (e.g., low-, moderate-, or high-transmission phases) that may not be apparent in raw case data, we applied MS-AR models to the annual time series of canine rabies cases only—the dog being the main reservoir and the other species the victims—for the period 1962–2023 (62 observations), as these data were available and consistent enough to capture multi-decadal transmission dynamics. We fitted a two-state and three-state Markov switching model of the form:

where:

- yt is the number of canine rabies cases in year t,

- st ∈{1,2} or {1,2,3} is a latent (unobserved) discrete state variable following a first-order Markov process,

- μst is the regime-specific mean,

- ϕ 1 is the autoregressive coefficient,

- σst2 is the regime-specific variance,

- Transition probabilities between states are governed by a stochastic matrix P = [pij] where pij = P(s t+1 = j ∣ s t = i).

Models were estimated using maximum likelihood via the Hamilton filter (32). The optimal number of regimes (two vs. three) was selected based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and log likelihood. We also assessed the interpretability and epidemiological plausibility of each regime. Model diagnostics were conducted by examining residuals for autocorrelation (Ljung–Box test) and by checking that the smoothed regime probabilities were consistent with known epidemiological patterns, as well as the persistence suggested by the transition matrix. The smoothed probabilities of being in a given regime at time t were computed to identify periods of high- vs. low-transmission risk. Regimes were interpreted based on the estimated means and variances (e.g., “low incidence,” “epidemic,” or “resurgence” phases). To evaluate the previously observed cycle in rabies incidence, spectral analysis and autocorrelation function (ACF) were used in conjunction with the MS model outputs. The duration of each regime was also calculated to assess the average length of epidemic cycles.

Graphical representations and statistical tests were performed using R version 4.3.3. The depmixS4 package was used to estimate the Markov switching models. Kruskal–Wallis tests and chi-squared tests were used to compare abundances and proportions of positive samples and vaccination coverage, respectively. A significant difference was concluded when the p-value was below 0.05. Seasonal distribution was assessed by summing the incidence by month and by the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The relationship between the number of cases and the number of vaccination campaigns was studied using a Spearman’s correlation test. Choropleth maps were created using R version 4.3.3.

Results

During the indicated 30-year period, a total of 20,320 animal samples provided by the passive surveillance of rabies were submitted to the laboratory for rabies diagnosis. Among the 20,320 submissions, 6,920 were diagnosed positive (34%).

Affected species

Dogs accounted for 61.4% (4,250/6,920) of all confirmed rabies cases during the 30 years of the study. Results revealed that ruminants are victims of bites from rabid dogs with 24% (1,662/6,920). Cattle predominated with 17% of the cases (1,183/6,920), followed by horses (7.2%; 503/6,920), sheep (4.7%; 328/6,920), and camels (0.41%; 29/6,920). Cats represent only 6.1% (429/6,920) of positive animals (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 189.42, df = 7, p-value < 2.2e−16).

Monthly and seasonal distribution of rabies cases in dogs

The monthly distribution of dog rabies cases shows that an average of 12 cases per month were reported. Data indicate that dog rabies was endemic in Tunisia with reported significant peaks in March, April, and May (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 28.42, df = 11, p-value = 0.00279) (Figure 2). The same result was found when data were aggregated by seasons, and there was a significant difference between seasons with a peak detected in spring (Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared = 20.657, df = 3, p-value = 0.000124).

Figure 2

Monthly distribution of dog rabies cases in Tunisia (1994–2023).

Temporal distribution of animal and human rabies cases in Tunisia

The temporal distribution of rabies cases can be divided into four periods (Figure 3). Between 1994 and 1999, the number of submissions ranged from 353 in 1995 to 681 in 1999, with an average of 423 animal samples per year. From 2000 to 2010, a slight increase in the number of samples was observed, with an average of 484 samples per year. In 2011, a marked decline was noted (282 samples), followed by a rapid upward trend, particularly after 2012. From 2012 onward, a significant rise was recorded, with the average increasing to 1,014 samples per year, peaking in 2023 with 1,281 samples. Similarly, the number of confirmed animal rabies cases fluctuated over the years. It varied moderately in the first period, with an average of 132 cases per year. A peak was recorded in 2000 with 262 cases. Subsequently, the annual average decreased to 157 cases, up to 2011, which was marked by the lowest number of reported cases. In contrast and since 2012, a substantial increase in surveillance activity and case detection was perceived. Concurrently, positive cases slightly increased more than two-fold (350 cases) between 2012 and 2023. The highest annual number of confirmed canine rabies cases was observed in 2014 (476 cases). Human rabies cases followed a similar temporal trend with reported cases reappearing intermittently.

Figure 3

Trends in animal submissions, laboratory-confirmed animal rabies cases, and human rabies cases in Tunisia, 1994–2017.

Three periods (1994–2000, 2002–2008, and 2010–2017) characterize the evolution of human rabies cases, with no cases reported in 2001 and 2009. The highest number of human rabies cases occurred in 1996 (seven cases), coinciding with a sustained period of high canine rabies incidence. A second peak was observed in 2008 with six cases (Figure 3).

To better understand the underlying transmission dynamics of dog rabies, an MS-AR model was applied to the annual time series of canine rabies cases from 1961 to 2023, identifying two distinct transmission regimes (Figure 4): the “low” regime (average = 83.4 cases/year) includes 1983–1988 (33–72 cases), 1993–1998 (59–113), and 2003–2011 (54–128), and the “high” transmission regime (average = 218.0 cases/year) includes 1961–1982, 1989–1992 (peaks at 354–356), and 2012–2023 (167–280). Since 2012, the country has entered an unprecedented 12-year phase of high transmission, suggesting a structural change in the epidemiological dynamics of rabies (Figure 4). Model diagnostics indicated a slight residual autocorrelation (Ljung–Box test, p = 0.03). This result suggests that the MS-AR(1) specification captures the main regime changes but may not fully account for short-term serial dependence. Despite this, the model robustly identifies two epidemiologically distinct states, and the smoothed probabilities align with observed epidemic patterns.

Figure 4

Temporal distribution of dog rabies cases in Tunisia (1961–2023). The time series is classified into two transmission regimes (low and high) using a Markov switching model. The size of the points reflects the probability of regime membership.

The transition probabilities estimated by the model indicate that, in the case of a low regime, the process has an equal probability of remaining in the same state or switching to the high regime (50% each). Conversely, in the case of a high regime, there is a 62.1% probability that the process will remain high and a 37.9% probability that it will transition to a low regime. The average duration of a low-transmission episode is 2.0 years, compared to 2.6 years for a high-transmission episode. These parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Transmission regime | Number of years | Means of cases | Median of cases | Minimum cases | Maximum cases | Duration episode | Probability of persistence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 31 | 83.4 | 80 | 33 | 140 | 2 | 50% |

| High | 31 | 218.0 | 199 | 125 | 356 | 2,6 | 62.1% |

High- and low-transmission regime parameters.

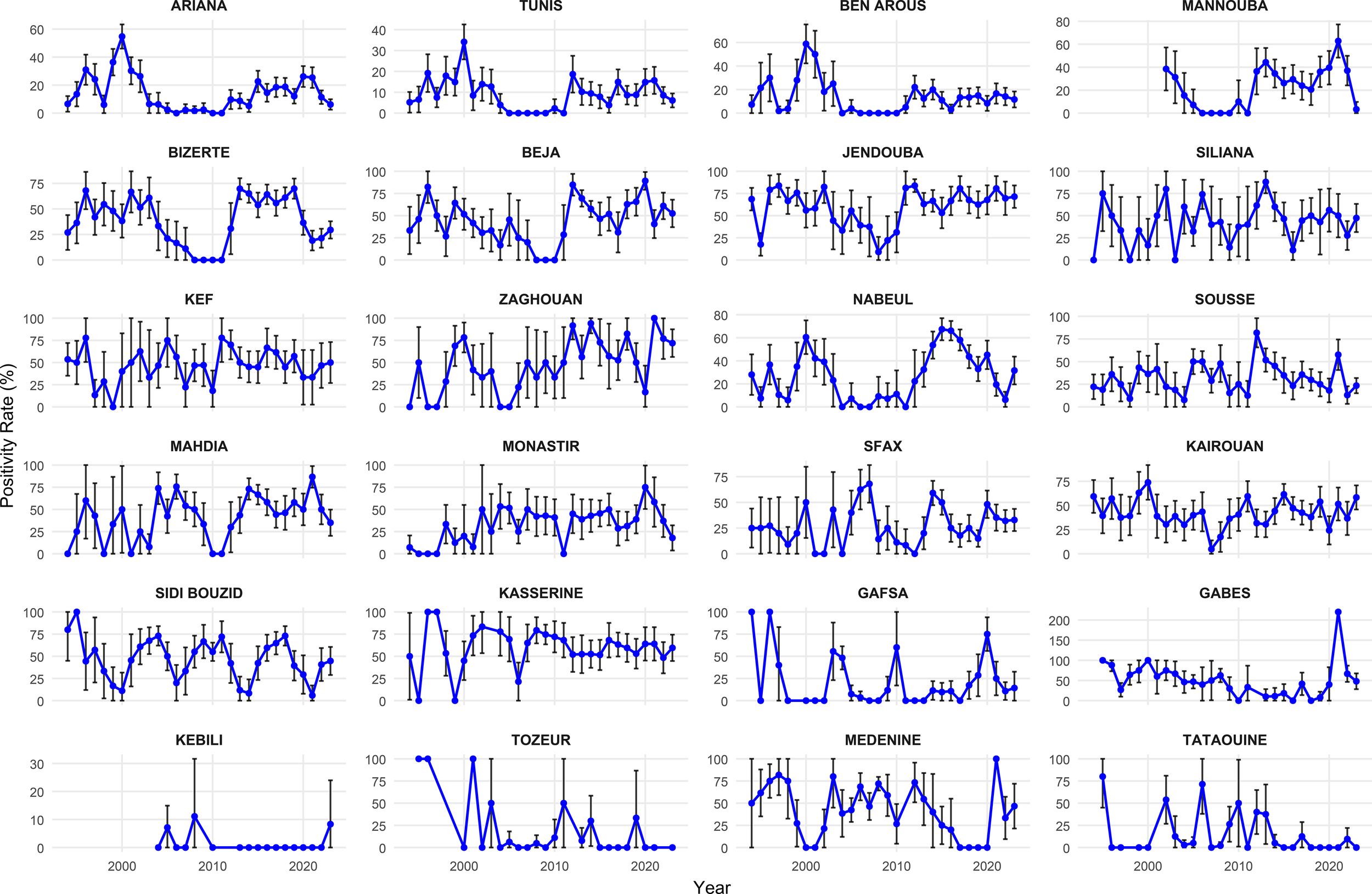

Analysis of regional trends of the annual positivity rate of rabies reveals a complex and heterogeneous epidemiological pattern across Tunisian governorates, characterized by interannual fluctuations. Peaks are often synchronized between neighboring governorates, as observed for Ariana, Beja, Tunis, Siliana, and Bizerte before 2000 and Beja, Jendouba, Bizerte, and Kef after 2010 (Figure 5). Notably, some governorates stand out due to their high risk and persistent transmission. These include Kasserine, Kairouan, Siliana, and Jendouba, where the positivity rate has exceeded 50% since 2010. In contrast, several governorates from the south (Tataouine, Tozeur, Medenine, Gabes, and Kebili, among others) reported a 100% positivity rate. However, this figure must be interpreted with caution, as it is based on very low sample sizes (often one to five submissions per year). The governorates of Kebili and Mannouba were created after 2000. Consequently, no data were available for these governorates prior to their creation, which explains their absence in the early period of the analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Evolution of the positivity rate of animal rabies in governorates in Tunisia, 1994–2023.

Geographical distribution of animal rabies cases

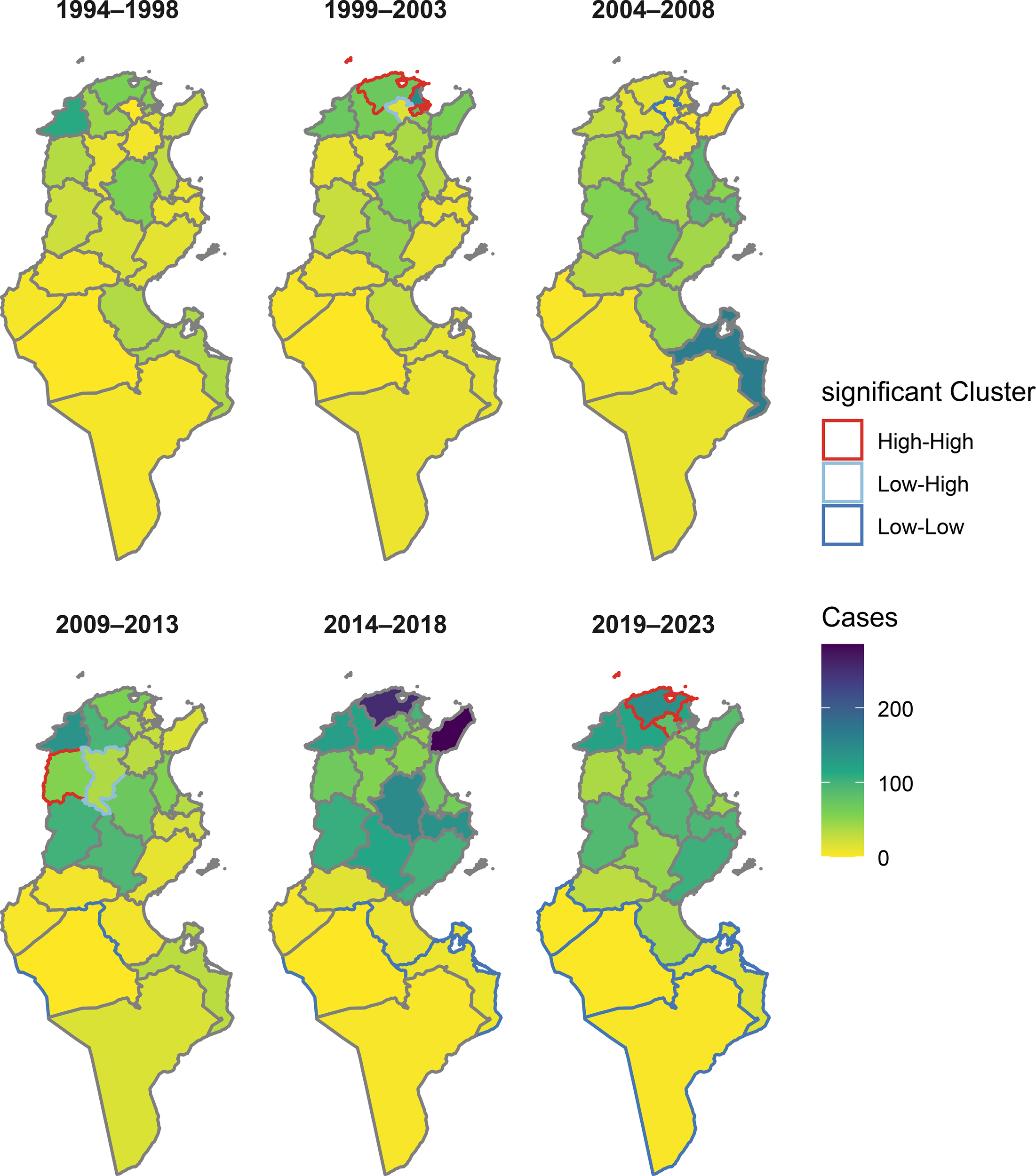

To assess the spatial distribution of animal rabies cases, data were aggregated into six 5-year periods: period 1 (1994–1998), period 2 (1999–2003), period 3 (2004–2008), period 4 (2009–2013), period 5 (2014–2018), and period 6 (2019–2023). Figure 6 illustrates the spatial evolution of the cumulative number of canine rabies cases in Tunisia across the 24 governorates. Over the 30-year study period, rabies was reported in all governorates at least once, with fewer cases detected in the southern and central-western regions.

Figure 6

Overlay of case intensity and significant clusters of canine rabies in Tunisia.

Periods 1 and 2: Rabies was predominantly confined in the north-east (Nabeul, Zaghouan, Ariana, Bizerte, Ben Arous, and Tunis), northwestern part of the country (Beja and Jendouba), and in the center (Kairouan, Sidi Bouzid) during these periods. The highest number of cases was recorded in the governorate of Ariana with 202 cases (total cases for the two periods), Jendouba with 183 cases, and Beja with 127 cases.

Period 3: A geographical change has occurred and a spread to the center from 2004 onward, with a decrease in the number of cases observed in the north-east. The governorates of Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, Kairouan, Mahdia, Sfax, Monastir, and Sousse reported 451 cases, accounting for 52.5% (451/858) of the total cases of this period. Two governorates from the north (Siliana and Kef) and two governorates from the south (Gabes and Medenine) have also recorded a high number of cases during this period.

Period 4: In addition to central governorates, rabies re-emerged in the north of the country. The governorates of Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, Beja, and Jendouba were identified as persistent hotspots.

Period 5: A marked intensification occurred in the north-west and north-east and the center between 2014 and 2018, particularly in the governorates of Bizerte, Kairouan, Mahdia, Jendouba, Beja, and Sidi Bouzid, where cumulative cases exceeded 250 (Bizerte and Nabeul). In contrast, southern governorates (Gafsa, Tozeur, Kebili, Tataouine, Gabes, and Medenine) reported the lowest number of rabies cases.

Period 6: A relative stabilization between 2019 and 2023, with continued high transmission in the north-west, was observed, but there was a slight decrease in previously affected areas (Figure 6).

Anselin’s local Moran’s I index applied at the governorate level reveals that areas of significant clustering (high–high) regularly extended in the north-east and north-west of the country, particularly in the governorates of Bizerte, Kef, Ariana, and Mannouba. In contrast, low–low clusters (low transmission surrounding low areas) appeared only in the south of the country from 2009 onward, indicating the persistence of rabies in isolated regions (Figure 6). Getis−Ord Gi* analysis endorses this result, and the identified hotspots (areas of high transmission) are concentrated in the north-east and north-west, while coldspots (areas of low transmission) are localized in the south, particularly in the governorates of Gabès, Médenine, and Tataouine (Figure 6). These results are consistent with the map of the cumulative cases, where the northwestern and northeastern governorates appear as high-prevalence areas, while the south remains generally low prevalence.

Rabies control program in animals

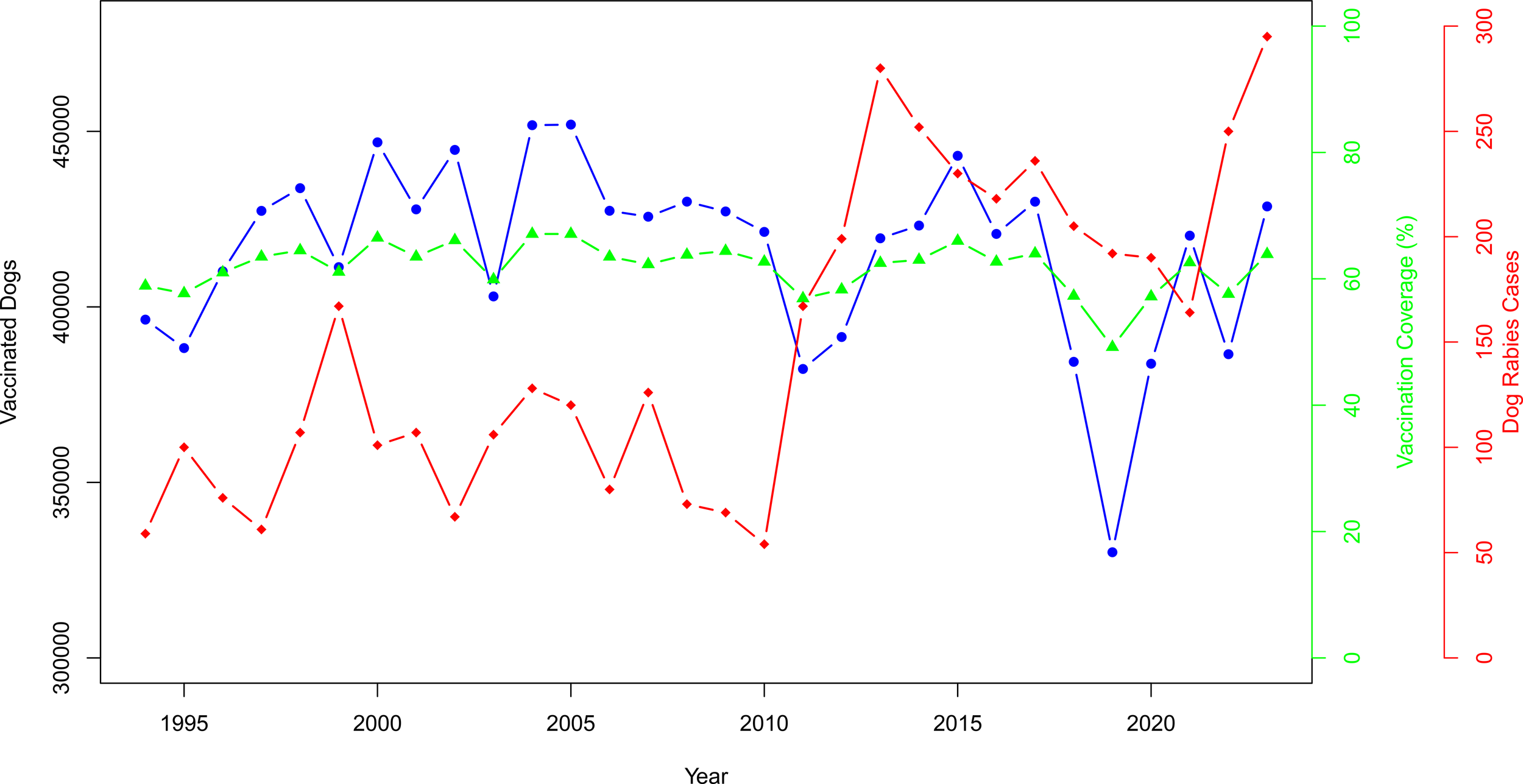

To evaluate the impact of the rabies control program, vaccination coverage was calculated by reporting the number of vaccinated dogs to the number of dogs to be vaccinated at the national level. The results presented in Figure 7 reveal an annual fluctuation of the number of vaccinated dogs, which remains approximately stable at approximately 400,000, with notable peaks in 2004, 2005, and 2023. Vaccination coverage trend seems to be also stable and under the recommended WHO value of 70% (33). The vaccination coverage remains mostly above 60% after 2000, except in 2011–2013 when it fell. The highest (67.1%; 451,766/673,000) was recorded in 2004 and 2005; however, the lowest (49.2%; 330,105/671,000) was in 2011, which was the most significant year during which a significant decrease in the number of vaccinated dogs was reported (Figure 7). Therefore, a remarkable increase in the number of cases was noted. A correlation test between vaccinated dogs in year n and the number of dog rabies cases observed in year n + 1 reveals a weak and insignificant negative correlation (r = −0.19, p = 0.3) (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Vaccination coverage (%) and number of vaccinated dogs in Tunisia (1993–2023).

Discussion

Rabies is a vaccine-preventable disease, and control measures have proven their efficacy to reach zero human cases (34). In Tunisia, despite more than four decades of control efforts, rabies remains endemic with an increase in confirmed cases observed since 2012.

The present study provides an in-depth overview of the epidemiological evolution of animal and human rabies cases in Tunisia over a 30-year period (1994–2023), highlighting multifaceted spatial, temporal, and transmission dynamics trends. It is important to note that this study focused on only the reported dog rabies cases captured through passive surveillance. Since rabies surveillance is known to capture less than 10% of actual cases in many settings (35, 36), the numbers reported here should be regarded as conservative estimates.

The analysis of the passive surveillance data reveals that rabies remains a major public and animal health issue and confirms the endemicity of the disease. As the primary source of human contamination is dog (14), the majority of analyses in this study were specifically conducted on dog rabies cases. Between 1994 and 2023, a total of 6,920 cases of rabies was confirmed at the IPT laboratory. Among these, dogs accounted for 61.4% of the diagnosed cases, confirming that they constitute the main vector and reservoir of rabies in Tunisia. This finding is consistent with global epidemiological data, according to which more than 99% of human rabies transmissions come from bites by infected dogs (37). Our results are similar to other studies conducted in Africa (31, 38–40). Lounis (41) reported that dogs are the main transmitter of rabies in Algeria (382 dog rabies cases in 2019) (41). In Morocco, 90% of human rabies cases are caused by dog bites (39, 42). Cattle are victims and represent 17% of total cases (the second affected species), and this finding is consistent with reports from neighboring countries such as Algeria (43), where bovines also account for a substantial proportion of reported cases. Additionally, while cats remain less frequently reported (6.1%) than cattle and horses, their role should not be ignored and must be discussed. Several studies have highlighted that cats can act as significant sources of rabies infection for humans and other animals (44).

The significant involvement of dogs in the chain of transmission in Tunisia highlights the importance of controlling canine rabies to reduce animal morbidity and the risk to humans. In addition to vaccination programs, dog population management (DPM) measures must be implemented in Tunisia in accordance with WOAH and WHO guidelines to reduce dog population turnover and density (45). As Tunisia currently lacks a structured national DPM program, an effective one must urgently be implemented, which aligns with international standards and definitively replaces ineffective dog culling campaigns, which have consistently demonstrated no measurable impact on rabies transmission and contradict the One Health principles (46, 47).

Monthly and seasonal analyses of dog rabies cases reveal endemic circulation of the virus with significant peaks in spring (March, April, and May). This seasonal pattern is confirmed by the seasonality of human cases (48) and could be attributed to several factors: increased canine activity during warmer periods, the mating season during which dogs’ fights tend to upsurge (49–52). This seasonal pattern has been observed in other countries (Morocco, Nepal, and Nigeria) (38, 53, 54).

The temporal evolution of dog cases shows two distinct periods. Between 1994 and 2011, a gradual decline in cases was observed, likely reflecting the impact of sustained vaccination efforts in the early 2000s. However, since 2012, there has been a marked resurgence of both animal and human cases, marking a break from previous trends. This reveal coincided with the period of national instability following the Tunisian revolution named “The Jasmin revolution,” during which disease surveillance and field activities were disrupted (14). Field veterinarians were unable to collect samples, and a notable variation in reporting cases was observed. Simultaneously, a decrease in vaccination has led to an explosive upsurge of rabies (476 cases in 2014). One year of drastic reduction in the vaccination coverage (2011) was enough to induce a large increase in the prevalence 1 year later (2012). This result highlights the need for a constant, continued, and large effort to sustainably eliminate the disease. This increase in rabies cases in the last years (2012–2017) may also be linked to the proliferation of the canine population observed in this period (671,838 dogs in 1998, 949,146 dogs in 2008, and 977,503 dogs in 2014) (24) due to the household garbage that was multiplied after the revolution. Indeed, the presence of garbage is considered a major risk factor for the persistence of rabies (55, 56). This resurgence was confirmed by the MS-AR model. The model identifies two transmission regimes—a “low” regime and a “high” regime—and reveals that Tunisia has entered an unprecedented phase of high, sustained transmission since 2012 for 12 consecutive years, suggesting a structural change in the epidemiological dynamics of the virus. The higher probability of remaining in the high regime (62.1%) than of returning to it from the low regime (50%) suggests a current worrying epidemic inertia, making it more difficult to exit this regime without targeted and intensified interventions. This situation reflects an unstable dynamic: Tunisia frequently alternates between phases of control and resurgence, without prolonged periods of stability.

According to model estimates, low-transmission episodes last on average 2.0 years, while high-transmission phases persist for 2.6 years, indicating frequent changes between epidemiological regimes. The persistence of the current high-transmission phase since 2012, lasting 12 years, is unprecedented in duration, suggesting a fundamental shift in rabies transmission dynamics. This prolonged period likely results from several interacting factors, such as low and heterogeneous vaccination coverage, inadequate management of rabies outbreaks, lack of coordination between sectors, and the continuously increasing dog population. Although the current analysis primarily focuses on canine rabies, the observed resurgence since 2012 also poses serious implications for human health. Human rabies cases, though relatively few each year, reflect failures in both animal control and timely or correct PEP. Strengthening rabies control, therefore, requires an integrated approach that ensures not only sustained dog vaccination but also equitable access to PEP, public awareness campaigns, and coordination between the veterinary and public health sectors. This One Health framework is essential to prevent spillovers to humans and to achieve the goal of zero human deaths from dog-mediated rabies.

Geographically, rabies is widespread across the country with marked heterogeneity. The north-western (Jendouba, Beja, Kef) and north-eastern regions (Ariana, Bizerte, Nabeul) appear to be persistent hotspots as confirmed by cluster analyses (local Moran and Getis–Ord Gi*), while in the south (Tataouine, Kebili, Tozeur, and Gafsa), only sporadic cases were reported. Results also show that rabies tends to move from one region to another over time. From the western region (governorate of Kasserine), rabies moved to the north of Tunisia (governorates of Siliana, Jendouba, Beja, Bizerte, and Zaghouan). It is probably due to the high density of dogs (14) in urban governorates and difficulties in accessing vaccination campaigns for rural governorates. A previous study in Tunisia reveals that the risk of rabies is low at low-dog densities (below 6.4 dogs/km²), suggesting that in these areas, virus transmission is limited by the isolation of animal populations or by insufficient connectivity to maintain the chain of transmission, which is applicable to the south of Tunisia. However, when density exceeds 33.5 dogs/km², the risk increases gradually, peaking at 170 dogs/km², which is observed in the north of Tunisia (57).

It was demonstrated that contact between dogs increases with a higher density of dogs (58). Similar results were observed in Morocco, where high rabies incidence was recorded in the most populated provinces (density more than 170.6 inhabitants/km2) (53). In Algeria, the south wilayas with low human density are free from rabies (59, 60). The road network may influence the spatial dynamics of rabies (61, 62). Other studies showed that dissemination of canine rabies is related to the movement of people (63).

The temporal evolution of human rabies incidence in Tunisia reveals a pattern of intermittent resurgence, with notable peaks in 1996 and 2008. This trend closely follows the waves of canine rabies, confirming the direct link between controlling animal rabies and preventing human rabies. The absence of human cases in certain years can be attributed to the concentrated efforts of veterinary services in implementing animal control measures and the effectiveness of public health awareness campaigns coordinated by the Ministry of Public Health, but the increase in human cases after 2021 is concerning and warrants discussion. It could be related to the increase in risk behaviors, including increased contact with pets such as cats, whose role in rabies transmission is often underestimated (64). Future rabies elimination strategies in Tunisia must treat human rabies not just as a consequence of canine transmission but as a sentinel indicator of gaps in the One Health approach, requiring coordinated monitoring of both dog vaccination and human PEP delivery.

Vaccination coverage rates at the national level have remained below the critical threshold of 70% recommended by the WHO throughout the study period, averaging approximately 60% (33). The drop in vaccination coverage to 49.2% in 2011, likely influenced by sociopolitical instability during the Tunisian revolution, was followed by a sustained surge in canine rabies cases from 2012 onward. This low level of dog vaccination coverage could be associated with the reduction in the number of vaccinated dogs, and the annual renewal rate for the dog population, estimated at 30%–40% in Tunisia (65, 66), was likely to have an impact on the epidemiological situation of rabies in the following years. Therefore, the persistent gap below the critical threshold likely explains the endemicity and recent intensification of rabies in Tunisia (67, 68). The weak and non-significant correlation between the number of vaccinated dogs in 1 year and dog rabies cases in the following year (r = −0.19, p = 0.3) should not be interpreted as evidence that vaccination is ineffective. On the contrary, mass vaccination of dogs remains the only proven strategy to eliminate canine rabies (69). This result rather highlights the complexity of transmission dynamics in Tunisia and suggests that the real questions are not whether to vaccinate but rather how many dogs to vaccinate, what types of dogs (owned, including puppies, or free roaming), and where and when to target campaigns. It is also important to highlight the potential limitations and biases in the annual estimation of the number of dogs used to calculate the vaccination coverage. The dog/human ratio used in the estimation of dog population is primarily related to the nature of the area (urban, suburban, and rural), which has probably evolved over time and can introduce uncertainty about the actual number of people. In addition, data on the composition and dynamics of subpopulations of dogs, which may present different levels of risk for rabies transmission, were not updated.

In addition, epidemiological and socioeconomic factors including gaps in the quality or spatial coverage of vaccination, limited communities’ engagement, and logistical challenges in rural or mountainous areas can contribute to the persistence of rabies despite the vaccination campaigns (70, 71).

A better understanding of the dog population, their movements, and the actual vaccination coverage of the subpopulations is crucial to ensure that campaigns effectively target the dogs most at risk and to maximize the effectiveness of control strategies. Filling these gaps is therefore essential for designing evidence-based rabies interventions in Tunisia.

Conclusion

This study highlights a concerning increase in canine rabies in Tunisia since 2012, with the disease remaining endemic and identified as a hotspot through modeling in several parts of the country. Despite efforts of veterinary services, insufficient vaccination coverage continues to limit the effectiveness of the control program. An improved strategy is urgently needed to reverse this trend, focusing on targeted vaccination in identified hotspots, inclusion of puppies aged less than 3 months, strengthened passive surveillance, better management of stray dogs, and increased community awareness. The MS-AR model provides a valuable tool for anticipating regime changes and adapting interventions in a timely manner. Finally, adopting a comprehensive “One Health” approach that integrates veterinary, human health, and environmental sectors will be essential to achieve the elimination of dog-mediated rabies as recommended by the WOAH.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The authors declare that no human participants or animals were directly involved in this study. All data were obtained from routine national surveillance systems (Decree No. 2009 -2200 of 14 July 2009) and aggregated epidemiological records provided by the IPT, the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Ministry of Public Health of Tunisia. Therefore, this study did not require a review by an ethics committee.

Author contributions

KaS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HM: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. KH: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BN: Writing – review & editing. LM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BB: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GR: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RE: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HK: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. KeS: Writing – review & editing. KhS: Writing – review & editing. ZI: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to all contributors of the National Rabies Control Program for their invaluable contribution. We also sincerely thank the administration of the IPT for their support of this program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI was used to generate a part of the script.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Afonso CL Amarasinghe GK Bányai K Bào Y Basler CF Bavari S et al . Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: update 2016. Arch Virol. (2016) 161:2351–60. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2880-1

2

Expert Consultation on Rabies, Weltgesundheitsorganisation . WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: second report; [Geneva from 18 to 20 September 2012]. Geneva: WHO (2013). p. 139. (WHO technical report series).

3

Singh R Singh KP Cherian S Saminathan M Kapoor S Manjunatha Reddy GB et al . Rabies – epidemiology, pathogenesis, public health concerns and advances in diagnosis and control: a comprehensive review. Vet Q. (2017) 37:212–51. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2017.1343516

4

Stöhr K Meslin FX . The role of veterinary public health in the prevention of zoonoses. Archives of virology. Supplementum. (1997) 13:207–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6534-8_20

5

Taylor LH Nel LH . Global epidemiology of canine rabies: past, present, and future prospects. Vet Med (Auckl). (2015) 6:361–71. doi: 10.2147/VMRR.S51147

6

Bennasrallah C Ben Fredj M Mhamdi M Kacem M Dhouib W Zemni I et al . Animal bites and post-exposure prophylaxis in Central-West Tunisia: a 15-year surveillance data. BMC Infect Dis. (2021) 21:1013. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06700-9

7

FAO . RAGE - tunisie. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2007). Available online at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:5UHVOqZE0tQJ:ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/012/ak150f/ak150f00.pdf+&cd=1&hl=fr&ct=clnk&gl=tn (Accessed March 20, 2025).

8

Warrell M . Rabies and African bat lyssavirus encephalitis and its prevention. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2010) 36:S47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.020

9

Aicha E . Economic impact of animal and human rabies prevention and control in Tunisia between 2012 and 2016. Int J Infect Dis. (2019) 79:36–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.11.093

10

Néfissa KB Moulin AM Dellagi K . La rage en Tunisie au XIXe siècle: recrudescence ou émergence? Gesnerus. (2007) 64:173–92. doi: 10.24894/Gesn-fr.2007.64009

11

Chadli A Benlasfar Z . Epidémiologie de la Rage en Tunisie. Analyse des Résultats des 30 Dernières Années. In: KuwertEMérieuxCKoprowskiHBögelK, editors. Rabies in the Tropics. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (1985). doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70060-6_49

12

World Health Organization . Réunion OMS sur la lutte contre la rage dans les pays maghrébins [PDF] (1985). Geneva: Author. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/62499/VPH_1985_fre.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed August 12, 2025).

13

Seghaier C Cliquet F Hammami S Aouina T Tlatli A Aubert M . Rabies mass vaccination campaigns in Tunisia: Are vaccinated dogs correctly immunized? Am J Trop Med Hygiene. (1999) 61:879–84. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.879

14

Kalthoum S Guesmi K Gharbi R Baccar MN Seghaier C Zrelli M et al . Temporal and spatial distributions of animal and human rabies cases during 2012 and 2018, in Tunisia. Vet Med Sci. (2021) 7:686–96. doi: 10.1002/vms3.438

15

Cleaveland S Lankester F Townsend S Lembo T Hampson K . Rabies control and elimination: A test case for one health. Vet Rec. (2014) 175:188–93. doi: 10.1136/vr.g4996

16

Wandeler AI Matter HC Kappeler A Budde A . The ecology of dogs and canine rabies: A selective review. Rev Sci Techn. (1993) 12:51–71. doi: 10.20506/rst.12.1.679

17

Bouslama Z Belkhiria JA Turki I Kharmachi H . Spatio-temporal evolution of canine rabies in Tunisia 2011–2016. Prev Vet Med. (2020) 185:105195. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105195

18

Hassine TB Ali MB Ghodhbane I Said ZB Hammami S . Rabies in Tunisia: A spatio-temporal analysis in the region of CapBon-Nabeul. Acta Trop. (2021) 216:105822. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.105822

19

Yilmaz Çağirgan Ö et Cagirgan A . Epidemiological modelling in infectious diseases: stages and classification. Vet J Mehmet Akif Ersoy Univ. (2020) 5:151–8. doi: 10.24880/maeuvfd.695267

20

Inayati S Iriawan N Irhamah . A markov switching autoregressive model with time-varying parameters. Forecasting. (2024) 6:568–90. doi: 10.3390/forecast6030031

21

Martínez-Beneito MA Conesa D López-Quílez A López-Maside A . Bayesian Markov switching models for the early detection of influenza epidemics. Stat Med. (2008) 27:4455–68. doi: 10.1002/sim.3330

22

Kharmachi H . Animal rabies in Tunisia. Pan Afr Med J. (2017) 4. Available online at: https://www.proceedings.panafrican-med-journal.com/conferences/2017/4/5/abstract/.

23

Dean DJ Abelseth MK Atanasiu P . The fluorescent antibody test. In: MeslinFXKaplanMMKoprowskiH, editors. Laboratory techniques in rabies, 4th ed. World Health Organization, Geneva (1996). p. 88–95.

24

Centre National de Veille Zoosanitaire en Tunisie (CNVZ) . Rage. (2017). Available online at: http://cnvz.agrinet.tn/index.php/fr/dossier-thematiques/mobilite-animales/item/392-rage (Accessed April 1, 2025).

25

Institut Pasteur Tunis . Rapport 2016 Institut Pasteur de Tunis (2016). Available online at: https://www.slideshare.net/Pasteur_Tunis/rapport-2016-institut-pasteur-de-tunis (Accessed March 2, 2025).

26

World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) . Chapter 3.1.18 – rabies (Infection with rabies virus and other lyssaviruses). In: Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (Terrestrial Manual). Paris, France: World Organisation for Animal Health. (2023). Available online at: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.01.18_RABIES.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2025).

27

Institut Pasteur Tunis . Rabies in Tunisia: Evolution and result of National Program of Rabies Control (2017). Available online at: https://www.slideshare.net/Pasteur_Tunis/rabies-in-Tunisiarabies-Tunisia-evolution-and-result-of-national-program-of-rabies-control (Accessed April 2, 2025).

28

Seghaier C Kalthoum S Ben Younes A . Animal rabies in Tunisia: Evolution and perspectives, in: Proceedings of the First Maghreban Meeting on Epidemiology of Animal Health Blida, Algeria. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer (2009).

29

Haddad N Kharmachi H Ben Osman F . Control programme against canine rabies in Tunisia: Control of rabies in stray dogs. Bull l’Académie Vét France. (1988) 61:395–401. doi: 10.4267/2042/64571

30

Aubert M Cliquet F Hammami S . de la vaccination orale du renard contre la rage à l’élimination de la rage canine. Bull Mensuel la Soc Vét Pratique France. (2000) 84:17.

31

Ripani A Mérot J Bouguedour R Zrelli M . Review of rabies situation and control in the North African region with a focus on Tunisia. Rev Sci Tech. (2017) 36:831–8. doi: 10.20506/rst.36.3.2718

32

Hamilton JD . A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica. (1989) 57:357–84. doi: 10.2307/1912559

33

Jibat T Hogeveen H Mourits MCM . Review on dog rabies vaccination coverage in Africa: A question of dog accessibility or cost recovery? PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2015) 9:e0003447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003447

34

Robardet E Bosnjak D Englund L Demetriou P Rosado Martín P Cliquet F . Zero endemic cases of wildlife rabies (Classical rabies virus, RABV) in the european union by 2020: an achievable goal. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2019) 4:124. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4040124

35

Hampson K Coudeville L Lembo T Sambo M Kieffer A Attlan M et al . Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2015) 9:e0003709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709

36

Taylor LH Hampson K Fahrion A Abela-Ridder B Nel LH . Difficulties in estimating the human burden of canine rabies. Acta Trop. (2017) 165:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.12.007

37

World Health Organization . Rabies: Fact sheet (2024). World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies (Accessed July 6, 2025).

38

Mshelbwala PP Weese JS Sanni-Adeniyi OA Chakma S Okeme SS Mamun AA et al . Rabies epidemiology, prevention and control in Nigeria: Scoping progress towards elimination. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2021) 15:e0009617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009617

39

Darkaoui S Cliquet F Wasniewski M Robardet E Aboulfidaa N Bouslikhane M et al . A century spent combating rabies in Morocco, (1911–2015): How much longer? Front Vet Sci. (2017) 4:78. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2017.00078

40

Mogano K Suzuki T Mohale D Phahladira B Ngoepe E Kamata Y et al . Spatio-temporal epidemiology of animal and human rabies in northern South Africa between 1998 and 2017. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2022) 16:e0010464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010464

41

Lounis M Zarif M Zeroug Z Brahimi SSF Meddour Z . Rabies in the endemic region of Algeria: knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) survey among university students. Animals. (2024) 14:2193. doi: 10.3390/ani14152193

42

Ziani S Sohaib K Lhor Y El Berbri I Fihri AOF . Multifactorial influences on rabies antibodies in moroccan exported dogs. Adv Anim Vet Sci. (2023) 11:1744–50. doi: 10.17582/journal.aavs/2023/11.10.1744.1750

43

Kardjadj M . Epidemiology of human and animal rabies in Algeria. J Dairy Vet Anim Res. (2016) 4. doi: 10.15406/jdvar.2016.04.00109

44

Fehlner-Gardiner C Gongal G Tenzin T Sabeta C De Benedictis P Rocha SM et al . Rabies in cats-an emerging public health issue. Viruses. (2024) 16:1635. doi: 10.3390/v16101635

45

Hiby E Rungpatana T Izydorczyk A Rooney C Harfoot M Christley R . Impact assessment of free-roaming dog population management by CNVR in greater bangkok. Animals. (2023) 13:1726. doi: 10.3390/ani13111726

46

Franka R Smith TG Dyer JL Wu X Niezgoda M Rupprecht CE . Current and future tools for global canine rabies elimination. Antiviral Res. (2013) 100:220–5. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.07.004

47

Morters MK Restif O Hampson K Cleaveland S Wood JL Conlan AJ . Evidence-based control of canine rabies: a critical review of population density reduction. J Anim Ecol. (2013) 82:6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.02033.x

48

Ayachi A Benabdallah R Bouratbine A Aoun K Bensalem J Basdouri N et al . Epidemiological profiles of human rabies cases in Tunisia between 2000 and 2022. Viruses. (2025) 17(7):966. doi: 10.3390/v17070966

49

Kehinde OO Adebowale OO Olaogun MO Olukunle J Adebowale O . Situation of rabies in a southwestern state of Nigeria: A retrospective study, (1997–2007). J Agric Sci Environ. (2009) 9:93–9. doi: 10.51406/jagse.v9i1.1066

50

Tenzin T Sharma B Dhand NK Timsina N Ward MP . Patterns of rabies occurrence in Bhutan between 1996 and 2009. Zoonoses Public Health. (2011) 58:463–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01393.x

51

Shrestha SP Chaisowwong W Upadhyaya M Shrestha SP Punyapornwithaya V . Cross-correlation and time series analysis of rabies in different animal species in Nepal from 2005 to 2018. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e25773. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25773

52

Gebru G Romha G Asefa A Hadush H Biedemariam M . Risk factors and spatio-temporal patterns of human rabies exposure in northwestern Tigray, Ethiopia. Ann Glob Health. (2019) 85:119. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2518

53

Fassi-Fehri N Bikour H . L’endémie rabique au Maroc de 1973 à 1983 [In French. Rev Sci Techn (International Office Epizootics). (1987) 6:55–67. doi: 10.20506/rst.6.1.280

54

Williams RD Entezami M Alafiatayo R Alabi O Horton DL Taylor E et al . Dog-mediated rabies surveillance in Nigeria, (2014–2023): investigating seasonality and spatial clustering. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2025) 10:76. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed10030076

55

Wright N Subedi D Pantha S Acharya KP Nel LH . The role of waste management in control of rabies: A neglected issue. Viruses. (2021) 13:225. doi: 10.3390/v13020225

56

Akinwale OP Olugasa BO Cadmus EO . Identification of geographic risk factors associated with clinical human rabies in a transit city of Nigeria (2015). ResearchGate. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283672072_Identification_of_geographic_risk_factors_associated_with_clinical_human_rabies_in_a_transit_city_of_Nigeria (Accessed April 26, 2025).

57

Kalthoum S Mzoughi S Gharbi R Lachtar M Bel Haj Mohamed B Hajlaoui H et al . Factors associated with the spatiotemporal distribution of dog rabies in Tunisia. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2024) 18:e0012296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0012296

58

Lembo T Hampson K Haydon DT Craft M Dobson A Dushoff J et al . Exploring reservoir dynamics: A case study of rabies in the Serengeti ecosystem. J Appl Ecol. (2008) 45:1246–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01468.x

59

Saadi F . Bilan épidémiologique de la rage en Algérie [Report] (2008). CIRAD. Available online at: http://agritrop.cirad.fr/577642/ (Accessed April 26, 2025).

60

Benali A . Étude épidémiologique de la rage dans la wilaya de Constantine (2017). Université Mentouri Constantine. Available online at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:AHY7oi_IS5IJ:bu.umc.edu.dz/theses/veterinaire/BEN6553.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=tn (Accessed March 17, 2025).

61

Sararat C Changruenngam S Chumkaeo A Wiratsudakul A Pan-Ngum W Modchang C . The effects of geographical distributions of buildings and roads on the spatiotemporal spread of canine rabies: An individual-based modeling study. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2022) 16:e0010397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010397

62

Wada YA Noordin MM Mazlan M Ramanoon SZ Izzati UZ Lau SF et al . Spatiotemporal mapping of canine rabies transmission dynamics in Sarawak, East Malaysia from 2017 to 2023. Trop Biomed. (2025) 42:36–43. doi: 10.47665/tb.42.1.006

63

Talbi C Lemey P Suchard MA Abdelatif E Elharrak M Jalal N et al . Phylodynamics and human-mediated dispersal of a zoonotic virus. PloS Pathog. (2010) 6:e1001166. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001166

64

Porsuk AO Cerit C . An increasing public health problem: Suspected rabies exposures. J Infect Develop Countries. (2021) 15:1694–700. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13133

65

OIE . Rabies control: Towards sustainable prevention at the source, in: Compendium of the OIE Global Conference on rabies control, Incheon-Seoul, 7–9. Paris, France: OIE. (2012). Available online at: https://openagrar.bmel-forschung.de/receive/openagrar_mods_00003606 (Accessed April 12, 2025).

66

Reece JF . Dogs and dog control in developing countries. In: SalemDJRowanAN, editors. The state of the animals III. Humane Society Press, Washington, DC (2005). p. 55–64.

67

Song M Tang Q Wang D-M Mo Z-J Guo S-H Li H et al . Epidemiological investigations of human rabies in China. BMC Infect Dis. (2009) 9:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-210

68

Knobel DL Lembo T Morters M Townsend SE Cleaveland S Hampson K . Dog rabies and its control. In: Rabies: Scientific Basis of the Disease and its Management. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier (2013). p. 591–615. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396547-9.00017-1

69

Velasco-Villa A Escobar LE Sanchez A Shi M Streicker DG Gallardo-Romero NF et al . Successful strategies implemented towards the elimination of canine rabies in the Western Hemisphere. Antiviral Res. (2017) 143:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.03.023

70

Sambo M Hampson K Johnson PCD Johnson OO . Understanding and overcoming geographical barriers for scaling up dog vaccinations against rabies. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:30975. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-82085-4

71

Arief R Hampson K Jatikusumah A Widyastuti M Basri C Putra A et al . Determinants of vaccination coverage and consequences for rabies control in Bali, Indonesia. Front Vet Sci. (2017) 3:123. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2016.00123

Summary

Keywords

Tunisia, canine rabies, dog, hotspot, vaccination, cluster, Markov switching autoregressive

Citation

Kalthoum S, Handous M, Kharmachi H, Baccar MN, Lachter M, Bel Haj Mohamed B, Gharbi R, Kachaou S, Khoufi S, Zaouia I, Hrabech K, Seghaier C, Cliquet F and Robardet E (2026) Rabies in Tunisia: a 30-year retrospective study (1994–2023). Front. Trop. Dis. 6:1694742. doi: 10.3389/fitd.2025.1694742

Received

28 August 2025

Revised

21 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

06 January 2026

Volume

6 - 2025

Edited by

Walter Muleya, University of Zambia, Zambia

Reviewed by

Sunny Doodu Mante, African Filariasis Morbidity Project, Ghana

Max Francois Millien, Université Quisqueya, Haiti

Augustin Twabela, Central Veterinary Laboratory, Democratic Republic of Congo

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kalthoum, Handous, Kharmachi, Baccar, Lachter, Bel Haj Mohamed, Gharbi, Kachaou, Khoufi, Zaouia, Hrabech, Seghaier, Cliquet and Robardet.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sana Kalthoum, kalthoum802008@yahoo.fr

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.