- Chaudhary Sarwan Kumar Himachal Pradesh Krishi Vishvavidyalaya, Palampur, India

Background: The rising cost of conventional feed ingredients and environmental concerns related to agro-waste disposal have created a need for sustainable feed alternatives. Vegetable waste provides valuable nutrients but contains anti-nutritional factors that may limit utilization. Strategic supplementation with small quantities of phytogenic additives such as cinnamon extract and turmeric powder may enhance nutrient utilization and overall performance.

Aim: This study evaluated the effects of partial substitution of conventional feed ingredients with vegetable waste, supplemented with low levels of cinnamon extract and turmeric powder, on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, carcass traits, and economic efficiency in broilers.

Methodology: A total of 150 day-old Vencobb-400 broiler chicks were randomly allocated to three dietary treatments for 42 days: T0 (control, basal diet), T1 (15% vegetable waste−4% Urtica dioica, 3% cauliflower, 3% pea, and 5% radish leaves–with 0.1% cinnamon extract and 0.3% turmeric powder), and T2 (same as T1 with approximately 10% reduced metabolizable energy).

Results: T1 demonstrated a significantly greater weight gain (P < 0.0001), showing a 16.96% increase over T0 and an improved feed conversion ratio of 1.72 over 2.05. Crude protein digestibility increased from 84.3% in T0 to 89.7% in T1. T1 also achieved the highest carcass yield, gross profit (40.0%) and European Efficiency Factor (321.96). No adverse effects were observed on liver enzyme levels.

Conclusion: Incorporating 15% vegetable waste, supported by minimal phytogenic supplementation, significantly improves broiler performance and profitability. Future research should explore optimization of waste composition and dietary energy levels for commercial application.

1 Introduction

Worldwide poultry production has transformed from traditional backyard operations to a technologically advanced industry. In 2025, global chicken meat production is forecast to reach 105.8 million metric tons (1), representing a 2% increase from the previous year. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, pork remains the most widely consumed meat globally (36%), followed by poultry (33%) (2). The rising demand for poultry products, driven by increasing urbanization and income levels, has led to intensified broiler production systems. While this growth contributes positively to food security and rural livelihoods, it also brings forth critical challenges—most notably, the availability and cost of feed. Feed constitutes the largest operational expense in broiler production, accounting for approximately 68–75% of the total cost (3). A major sustainability challenge stems from the broiler industry's heavy reliance on conventional feed ingredients like maize and soybean—commodities that are increasingly in demand for both human consumption and biofuel industries (4). Recent market analyses indicate that the global poultry feed market was valued at approximately USD 233 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach around USD 259 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 1.8%, reflecting the rising global feed costs and economic pressure on poultry producers. Moreover, resource constraints such as land degradation, water scarcity, and ecological pollution from conventional feed production necessitate innovative solutions.

Within this framework, incorporating vegetable waste and by-products unsuitable for human consumption as alternative feed ingredients offer a promising strategy. Globally, an estimated 1.05 billion tons of food was wasted in 2022, generating 8–10% of total greenhouse gas emissions and occupying nearly 30% of agricultural land (5). In countries like India, China, the Philippines, and the United States, vegetable waste alone—which includes leaves, discarded peas, and other non-edible parts—totals an estimated 55 million tons annually (6). This growing dependence raises serious sustainability concerns for broiler production, including competition with human food supplies, land and water scarcity, and the environmental impacts of large-scale feed production (7). In this context, identifying and utilizing alternative feed sources such as non-edible vegetable wastes is essential to improve sustainability and reduce environmental pollution. Globally, 10–20% of horticultural produce is discarded, representing a significant waste of resources. Redirecting this surplus vegetable biomass into broiler diets provides a dual benefit: reducing feed costs and mitigating ecological impacts. Broilers, owing to their efficient digestive and metabolic systems, can effectively convert vegetable waste into high-quality animal protein. Recent studies suggest that moderate dietary fiber levels (2–3%) can improve gizzard development and function in broilers by providing mechanical stimulation that enhances grinding activity and digestion efficiency (8). Additionally, components like Urtica dioica offer further nutritional benefits. It contains a wide range of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, polysaccharides, isolectins, terpenes, sterols, proteins, vitamins, minerals, volatile compounds, and fatty acids such as stearic, oleic, palmitic, and linolenic acids. The plant's leaves are rich in calcium, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, magnesium, iron, and vitamins B, C, and K. It also contains carotenoid, chlorophyll, glucokinins, and essential amino acids, which may support overall health and nutrient utilization in poultry (9).

Vegetable-derived feed materials, though nutrient-rich, often contain anti-nutritional compounds—such as phytic acid, nitrates, oxalates, tannins, alkaloids, trypsin inhibitors, and α-galactosides—that may hinder nutrient absorption and growth performance. At the molecular level, dietary modulation has been shown to influence intestinal immune signaling and epithelial integrity, thereby regulating nutrient absorption and host defense mechanisms in monogastric animals (10). To counteract the negative effects of these anti-nutrients, phytogenic feed additives (PFA) have emerged as a sustainable strategy. Beyond their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, PFAs and vegetable-derived feed components can beneficially modulate the gut microbiota composition, promoting beneficial microbial taxa and maintaining intestinal ecological balance, as revealed by recent metagenomic studies (11). PFAs have also been shown to enhance intestinal morphology, digestive enzyme secretion, and mucosal immunity through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways, thereby improving gut barrier integrity and nutrient assimilation in broilers (12). Moreover, phytogenic and botanical feed additives exhibit immunomodulatory effects by enhancing cytokine expression, stimulating macrophage activity, and promoting both innate and adaptive immune responses, thereby supporting overall health and resilience in broilers (13). PFA are known to improve nutrient digestibility, immune function, and growth performance while also meeting consumer demand for antibiotic-free poultry products. The global PFA market was valued at approximately USD 1.05 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 1.48 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 6.04% from 2025 to 2030. The poultry segment accounted for about 44% of this market in 2024, driven by the regular use of PFAs to improve poultry product quality and by ongoing research into novel phytogenic substances (14). Therefore, integrating processed vegetable waste with appropriate PFA not only mitigates anti-nutritional constraints but also lowers feed costs through the use of locally available plant-based by-products, enhancing both sustainability and profitability in broiler production.

Among these, cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) and turmeric (Curcuma longa) are known for their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects. The essential oil of cinnamon bark is rich in trans-cinnamaldehyde and other biologically active compounds such as cinnamyl acetate, eugenol, and β-caryophyllene which contribute to its antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties (15). The major active principle in cinnamon is the cinnamaldehyde. Antimicrobial properties of cinnamon are related to its cinnamaldehyde content followed by eugenol and carvacrol content. Curcumin is the key bioactive component responsible for the biological properties of Curcuma longa (16). Furthermore, adding turmeric (Curcuma longa) to poultry feed could reduce the harmful effects of aflatoxins on the liver and kidneys of chickens (17). Both cinnamon and turmeric have been shown to enhance feed intake, stimulate digestive enzymes, improve nutrient absorption, and support overall broiler performance. Similar findings have been reported where dietary inclusion of cinnamon extract and turmeric powder improved feed conversion efficiency, nutrient utilization, and broiler performance without adverse effects (18, 19). However, limited studies have examined the combined use of vegetable waste-based feed with phytogenic supplements under reduced energy diets. Addressing this gap is essential to develop sustainable and cost-effective feeding strategies without compromising broiler performance. Therefore, the present study was conducted to evaluate the effects of incorporating 15% vegetable waste, supplemented with cinnamon extract and turmeric powder, in broiler diets on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, carcass traits, and economic efficiency. In addition, a group receiving the same vegetable waste and phytogenic additives with approximately 10% reduced metabolizable energy was included to assess the impact of lower dietary energy density. We hypothesized that the vegetable waste-based diet supplemented with phytogenic additives would improve broiler performance and profitability compared to a conventional diet, and that moderate energy reduction may compromise these benefits.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethical approval

The experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) at DGCN COVAS, CSKHPKV, Palampur, Himachal Pradesh, India (Proposal No. IAEC/24/07, approved March 16, 2024). Approval covered the use of 150 Vencobb broiler chicks, in compliance with institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of animals.

2.2 Feed ingredient collection and preparation

Vegetable waste—including stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), cauliflower leaves and stems, radish leaves, and pea pods (with discarded peas)—was collected from local markets and households in Palampur, Himachal Pradesh. The material was washed, blanched at 80 °C for 2–3 min, and cooled. It was then sun-dried for 2 days under ambient conditions (32–35 °C), followed by oven drying at 55 °C for 6 h to ensure uniform moisture removal. The dried material was ground and incorporated into the basal diets along with phytogenic feed additives. The vegetable waste mixture used in the experimental diets was analyzed for proximate and mineral composition. The results are presented in Table 1. This processing method has been reported to reduce heat-labile antinutritional factors such as phytates, tannins, and saponins (20, 21). However, more heat-stable compounds such as lectins and protease inhibitors may not be fully inactivated under these conditions, as their deactivation generally requires higher temperatures and moist heat treatments (21). Roasted soybean was processed separately by dry roasting to improve palatability and reduce anti-nutrient levels. Phytogenic feed additives, including turmeric powder and cinnamon extract, were included to enhance the bioactive profile of the diet. Cinnamon bark (50 g) was extracted in 400 mL of 50:50 ethanol–water for 24 h, filtered, dried at room temperature for 3–4 days, ground, and stored at 4 °C. Other feed ingredients—such as maize, soya flakes, roasted soybean, vegetable oil, sodium bentonite, dicalcium phosphate, limestone, and premixes—were procured from the Department of Animal Nutrition Feed Store, DGCN COVAS, CSKHPKV and analyzed for nutrient composition prior to diet formulation.

2.3 Experimental design

A total of 150 day-old Vencobb-400 chicks were randomly allocated to three treatments, each with five replicates of 10 birds (Table 2). Diets were formulated for pre-starter (0–14 d), starter (15–21 d), and finisher (22–42 d) phases according to ICAR (2013) nutrient specifications. All diets were iso-nitrogenous and iso-caloric, except the reduced-metabolizable energy (ME) treatment. The T0 (control) group was fed a standard ICAR-based basal diet. The T1 group was fed a diet consisting of 85% basal feed and 15% vegetable waste (4% Urtica dioica, 3% cauliflower waste, 3% pea waste, 5% radish leaves), supplemented with 0.1% cinnamon extract and 0.3% turmeric powder. The T2 group was fed the same diet as T1, but with approximately 10% lower ME (Table 3). In this study, 15% vegetable waste was included in the broiler diet based on previous research demonstrating that vegetable by-products can be safely incorporated at levels up to 15–20% without adversely affecting growth performance or health (22–24). The inclusion levels of the nutraceuticals were based on previous research. Supplementing broiler diets with 0.1% cinnamon extract significantly enhanced feed conversion efficiency, nutrient utilization, and meat quality (18). Additionally, a previous study showed that turmeric powder, when used up to 0.5%, supported weight gain without causing any adverse effects (19).

2.4 Housing and management

From day 0–7, chicks were housed in battery brooders (36 × 72 inches) at 33–35 °C and 50–60% relative humidity. From day 8–42, they were reared in deep-litter pens (5 × 4 × 6 ft), stocking density of approximately 5.4 birds/m2, with 6 cm sawdust bedding at a temperature of 17.4–25 °C and 40–60% humidity. Feed and water were provided ad libitum, with 24-h lighting and adequate ventilation. Daily feed intake was recorded per replicate.

2.5 Analytical procedures

Proximate composition [dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), ether extract (EE), crude fiber (CF), total ash (TA), and nitrogen-free extract (NFE)] of feed ingredients, experimental diets, and feces was analyzed according to AOAC methods (25). DM was determined by oven drying; TA by muffle furnace; EE by Soxhlet extraction; CP by the Kjeldahl method; CF using a fiber analyzer. Calcium (Ca) was estimated by atomic absorption spectrophotometry, and phosphorus (P) by the spectrophotometric method (26). The ME of ingredients was calculated using a previously suggested equation (27).

2.6 Assessment of apparent nutrient digestibility

On day 35, a metabolic trial was conducted using the total fecal collection method. Two birds per replicate were placed in battery brooders for a 3-day adaptation, followed by 5 days of fecal collection. Feed was offered twice daily, and refusals were weighed to determine intake. Feces were pooled per replicate, with one portion preserved in 5% sulfuric acid for nitrogen estimation and the other for DM estimation. Digestibility coefficients for DM, CP, CF, EE, Ca, and P were calculated using the equation:

where nutrient intake is the amount of a given nutrient consumed by the birds and nutrient outgo is the amount excreted in feces during the collection period.

2.7 Growth performance

Initial body weight was measured before the chicks were housed, followed by weekly measurements. Weight gain was calculated as the difference between final and initial body weight for each replicate. Feed intake was monitored daily by providing a measured quantity of feed to each replicate and recording the feed refusal at the end of the day. Based on the collected data, feed conversion ratio (FCR: total feed consumed during the period divided by total weight gain) was calculated for each growth phase and the overall period.

2.8 Carcass characteristics and gizzard thickness

At day 42, two birds per replicate (average body weight) were fasted overnight and slaughtered by the jhatka method. Standard dressing procedures were followed, and weights of carcass components were recorded. Gizzard wall thickness was measured at three external points using a vernier caliper, and the mean was calculated per bird.

2.9 Meat quality assessment

Meat samples were collected post-slaughter and stored at −20 °C. Proximate composition was determined per AOAC methods (25). Sensory evaluation followed the described method (28): thawing at 3 °C for 18 h, deboning, cubing (2 × 2 × 2 cm), salting (1% NaCl), and pressure cooking to 80 ± 2 °C for 15 min. Sensory evaluation was conducted by panelists, comprising faculty and laboratory staff from the Department of Livestock Products Technology, Animal Nutrition, CSKHPKV, Palampur, who had prior familiarity with meat quality assessment but were not formally trained in sensory discrimination protocols. They scored flavor, texture, tenderness, juiciness, appearance, and overall acceptability on an 8-point scale (8 = like extremely; 1 = dislike extremely).

2.10 Serum biochemical analysis

On day 42, blood samples were collected from two birds per replicate (10 birds per treatment) via jugular venipuncture using sterile 24-gauge needles. Samples were transferred into clot activator vials for serum separation. Serum was obtained by allowing samples to clot for 3–4 h at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 15 min. ALT (SGPT) and AST (SGOT) activities were determined using commercial diagnostic kits (LyphoCHEK SGPT and SGOT kits; Agappe Diagnostics Ltd., Kerala, India). For each test, 100 μL of serum and 1,000 μL of reagent were mixed, incubated at 37 °C for 1 min, and the change in absorbance per minute (Δ OD/min) was recorded over 3 min using a MispaViva semi-automated clinical chemistry analyzer (Agappe Diagnostics Ltd.).

2.11 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) under a completely randomized design with IBM SPSS v30.0. Treatment means were compared using Tukey's Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test, and differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05, with additional levels of significance reported as P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001 where applicable. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (29). In addition, effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated for the primary performance indicators (overall final body weight, daily weight gain, feed intake, and FCR) to quantify the magnitude of treatment differences and to evaluate the adequacy of the replication level. Cohen's d was calculated for pairwise comparisons against the control (T0) using:

Standard deviations (SD) were obtained from the reported SEM using:

The exact Cohen's d values were:

Final body weight: T1 vs. T0 = 5.22; T2 vs. T0 = 1.54

Weight gain: T1 vs. T0 = 5.30; T2 vs. T0 = 1.52

Feed intake: T1 vs. T0 = 1.07; T2 vs. T0 = 1.88

FCR: T1 vs. T0 = 4.85; T2 vs. T0 = 1.57.

All effect sizes exceeded the conventional threshold for a large effect (d ≥ 0.8), with several reaching very large to extremely large magnitudes (d = 1.07–5.30), indicating that five replicates per treatment were adequate to detect biologically meaningful differences.

2.12 Economic evaluation

Economic performance was assessed using viability percentage, the European Efficiency Factor (EEF), and the cost of producing 1 kg live weight (Cm).

Viability (%) represents the proportion of broilers that survived until the end of the trial and was calculated as (30):

The EEF, a composite index of growth rate, feed efficiency, survival rate, and rearing duration, was calculated as:

where BW is the average body weight (kg), FCR is the feed conversion ratio, and A is the age of broilers (31). The production cost per kilogram of live weight was determined as:

where, Cm is the production cost (INR) per kg live weight and Cf is the cost of feed per kg (32).

3 Results

3.1 Growth performance

Growth performance was recorded during pre-starter (0–14 days), starter (15–21 days), finisher (22–42 days), and overall (0–42 days) phases (Table 4). Initial body weight values across all treatment groups were highly uniform. The highest final body weight was observed in T1 compared to T0 (control), while T2 (same diet as T1 with approximately 10% reduced ME) recorded lowest body weight during all the phases.

Table 4. Growth performance of broilers fed experimental diets during different phases: pre-starter (0–14 d), Starter (15–21 d), Finisher (22–42 d), and Overall (0–42 d).

A similar trend was observed in daily weight gain, with T1 showing significantly higher daily gains than both T0 (control) and T2 (p < 0.01). T1 consistently exhibited superior daily weight gain across all phases. Despite receiving the same feed formulation as T1, the reduced ME content in T2 led to significantly lower daily weight gains in all phases.

During the pre-starter and starter phases, daily feed intake was significantly higher in T0 compared to T1, while T2 had the lowest daily intake (p < 0.0001). This trend reversed in the finisher and overall phases, with T2 exhibiting the highest daily feed intake, followed by T1 and then T0. The treatment trends for total feed intake and weight gain mirrored their respective daily values.

Feed conversion ratio (FCR) was significantly improved in the T1 group across all phases, while T2 exhibited the poorest FCR. T0 displayed intermediate efficiency. No mortality was observed in any treatment group throughout the experimental period.

3.2 Apparent nutrient digestibility

Apparent digestibility coefficients of proximate nutrients (% DM basis) were determined in broiler chickens (Table 5). T1 and T2, both supplemented with vegetable waste, exhibited significantly higher digestibility of crude protein (CP) (p < 0.05), ether extract (EE), and phosphorus (P) (p < 0.01) compared to T0 (control). Although CP and P digestibility were statistically similar between T1 and T2, T1 exhibited numerically higher CP and P-values, while T2 showed a slightly higher ether extract digestibility. No significant differences were observed among groups for crude fiber (CF) and calcium (Ca) digestibility.

Table 5. Apparent digestibility coefficients of proximate nutrients (% DM basis) in broiler chickens during metabolic trial.

3.3 Carcass characteristics

3.3.1 Edible by-product yields (% live weight)

The edible by-product yields of broilers under different dietary treatments are presented in Table 6. Dressing percentage (relative to live weight) was significantly higher in T1 than in both T0 and T2 (p < 0.01). T2 performed similarly to T0, suggesting that the approximately 10% reduction in ME did not adversely affect dressing yield. Liver and gizzard yields (as percentages of live weight) were also significantly higher in T1 compared to T0 (p < 0.01), while T2 showed the lowest gizzard yield. Heart and skin yields did not differ significantly among treatments.

Table 6. Carcass attributes and edible by-product yields (% of live weight) of broiler chickens fed experimental diets.

3.3.2 Gizzard thickness and inedible by-product yields (% live weight)

The data on gizzard thickness and inedible by-product yields are shown in Table 7. Gizzard thickness was significantly higher in T1 compared to T0 (p < 0.01). The highest abdominal fat percentage was recorded in T0 (control) group compared to treatments (T1 and T2). Head yield was significantly higher in T1 than in T0 (p < 0.01), while feet yield did not differ significantly but was numerically higher in T1.

Table 7. Gizzard thickness and inedible by-product yields (% of live weight) of broiler chickens fed experimental diets.

3.4 Muscle yields

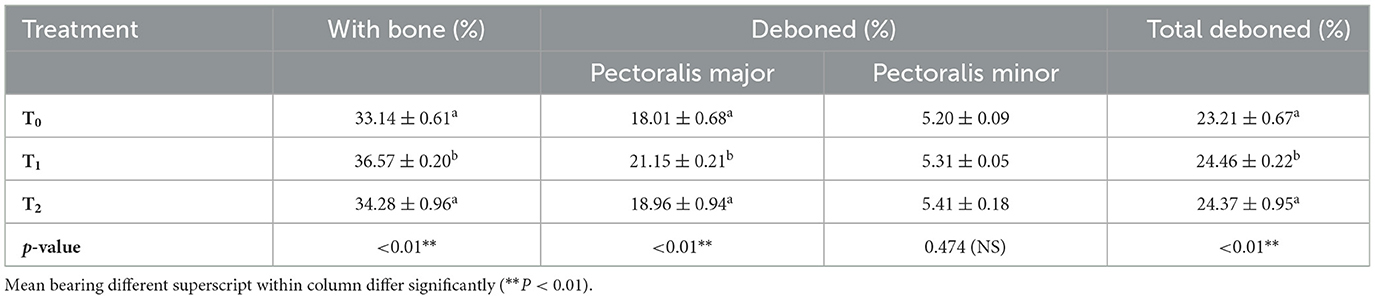

3.4.1 Breast muscle yield

The breast muscle yields are presented in Table 8. Boned and deboned breast muscle yields were significantly higher in T1 compared to both T0 and T2 (p < 0.01), while T0 and T2 displayed similar values. The deboned percentage of pectoralis major was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in T1 compared to the control group (p < 0.01), whereas pectoralis minor yield showed no significant differences, although numerically higher values were observed in T1 and T2 than in T0.

3.4.2 Leg muscle yield

The leg muscle yields are shown in Table 9. Thigh muscle yield did not differ significantly among the treatment groups (p = 0.123), indicating that dietary modifications did not affect thigh growth. However, drumstick percentage and total leg muscle yield were significantly higher in T1 compared to T0 (p < 0.01), with T2 showing intermediate performance. These findings suggest that reduced energy intake in T2 may have slightly limited leg muscle deposition.

3.5 Meat quality

3.5.1 Proximate composition

The proximate composition of broiler meat is summarized in Table 10. DM content was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in T1 compared to the control group (T0), while T2 and T0 recorded similar values. CP content differed significantly among groups (p < 0.01), with both T1 and T2 exhibiting higher CP values than T0. The highest (p < 0.01) EE content was observed in T0 (control), while T2 recorded the lowest value (p < 0.01). TA content did not differ significantly among treatments, although numerically higher values were recorded in T1 compared to T0. A highly significant difference (p < 0.01) in acid-insoluble ash (AIA) content was observed among groups, with both T1 and T2 showing higher values than the control (T0).

3.5.2 Sensory evaluation

The results of the sensory evaluation are given in Table 11. Differences in sensory attributes among the groups were non-significant for appearance/color and texture/tenderness scores, though numerically higher values were recorded in T1 compared to the T0 (control), while T2 had the lowest scores. The highest scores for flavor and juiciness (p < 0.05) were exhibited in treatment groups T1 and T2 compared to T0 (control). The overall acceptability scores were non-significant among the groups; however, numerically, the highest value was recorded in T1 compared to T0 (control).

3.6 Liver enzyme profile

The results for liver enzyme profile are given in Table 12. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels did not differ significantly among dietary treatments (p = 0.473 and 0.973, respectively). ALT values ranged from 24.49 to 27.73 U/L, while AST values ranged from 180.76 to 185.30 U/L, all of which fall within normal physiological limits for broilers.

3.7 Economic analysis

Economic parameters of different treatment groups are presented in Tables 13, 14. T1, included vegetable waste and was supplemented with small amounts of cinnamon extract and turmeric powder, incurred the highest feed cost per bird but also yielded the greatest final body weight and highest sale return, demonstrating its economic advantage. In contrast, T2 (with approximately 10% reduced ME) recorded the lowest feed cost but also the lowest return and body weight. The T0 (control) group was intermediate in both cost and return.

T1 achieved the highest gross profit, whereas T0 and T2 showed comparable results. Although the inclusion of cinnamon extract and turmeric powder slightly increased the feed cost in T1, its superior feed conversion ratio (FCR) resulted in a higher gross profit percentage, confirming the economic benefit of the supplementation strategy.

In terms of production efficiency, T1 recorded the highest EEF, followed by T0, while T2 had the lowest EEF due to the energy reduction in its diet. Viability (%) remained 100% across all groups. The cost of production per kilogram of live weight was lowest in T1 and highest in T0. Collectively, the improved FCR, elevated EEF, and reduced production cost in T1 confirm the economic viability of incorporating vegetable waste supplemented with cinnamon extract and turmeric powder in broiler diets

4 Discussion

4.1 Growth performance

The inclusion of vegetable waste (cauliflower waste, pea waste, radish leaves, nettle) in diet T1 significantly improved live weight gain and feed efficiency in broiler chickens. These improvements likely reflect enhanced nutrient digestibility and utilization, arising from the synergistic effects of dietary fiber and PFA (cinnamon and turmeric). Dietary fiber can improve gizzard function and gut motility, facilitating efficient feed passage and nutrient absorption (8). Correlation analysis further supported this relationship, showing a positive association between crude protein digestibility and final body weight (r = 0.46), and a negative correlation with FCR (r = −0.43), indicating that improved protein utilization contributed to better growth efficiency.

The phytogenic properties of cinnamon and turmeric, attributed to their antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, may also contribute to improved digestion and nutrient utilization (33). Cinnamaldehyde in cinnamon enhances digestion by stimulating salivary secretions and increasing intestinal and pancreatic enzyme activity (34), thereby supporting higher live weight gain. In addition, the antioxidant and immunomodulatory potential of phytogenic compounds such as cinnamaldehyde and curcumin have been shown to mitigate oxidative stress and enhance growth performance in broilers (35). In our study, cinnamon and turmeric supplementation improved FCR, likely due to their digestive and metabolic effects. Similar outcomes were reported in previous studies for cinnamon (36) and turmeric (37) which were attributed to their antioxidant properties and improved protein utilization, supporting growth and feed efficiency in broilers.

In the pre-starter phase, T1 achieved a numerically lower FCR compared to the control group (T0) despite lower feed intake, although the difference was not statistically significant. T2, in contrast, showed poorer FCR, suggesting reduced nutrient utilization efficiency—likely due to its lower energy content. It is important to note that sodium bentonite was used to dilute the diet in T2 in order to reduce ME by approximately 10%, replacing energy-contributing ingredients such as maize and soybean meal. While sodium bentonite is commonly used in poultry diets and was selected for its availability and presumed inertness, it may not be entirely metabolically inactive. Previous studies indicate that sodium bentonite can adsorb nutrients and alter intestinal transit and digestibility, which may reduce the bioavailability of some dietary nutrients and thereby affect energy utilization and growth (38). Its nutrient-binding properties could have further reduced the bioavailability of certain nutrients, thereby lowering actual ME more than anticipated. This unintended effect may have contributed to the poorer performance observed in T2. This limitation has been acknowledged, and future studies may consider using truly inert diluents such as purified cellulose or acid-washed sand to avoid potential confounding effects. During the starter phase, T1 recorded the highest weight gain, whereas T2 performed significantly worse (P < 0.01), again highlighting the limitations of reduced energy. In the finisher phase, T2 improved weight gain compared to earlier phases, accompanied by increased feed intake in both T1 and T2. This likely reflects compensatory feeding behavior in T2 broilers, where intake increased to offset the lower energy density of the feed. Although statistically different (p < 0.05), the feed intake values were very close in absolute terms—the differences were minimal (< 0.2 g/day), indicating that palatability and satiety were likely unaffected, and that differences in growth performance were primarily driven by nutrient utilization rather than consumption, as also reported for cinnamon powder supplementation (39).

Therefore, it is plausible that differences in growth performance were driven more by nutrient utilization efficiency than by consumption volume, consistent with previous findings on cinnamon powder supplementation.

Overall, T1 consistently demonstrated the most favorable growth outcomes, supporting earlier findings on the benefits of vegetable waste–based diets at moderate inclusion levels (23, 40). However, it is important to note that some studies have reported reduced growth performance at higher levels of vegetable waste inclusion. For example, one study observed significant declines in feed intake and weight gain when vegetable waste inclusion exceeded 25%, indicating potential limitations at excessive levels (41). Similarly, improved live weight and FCR were reported up to 15% inclusion, but performance declined at higher levels (23). These contrasting findings suggest that the effects of vegetable waste depend on the inclusion rate, type and composition of the waste, processing methods, and overall dietary formulation. It is also important to acknowledge that the use of five replicates per treatment may introduce some limitations in the precision of zootechnical performance estimates; however, the treatment differences observed in this study were associated with very large effect sizes (e.g., overall final body weight: d = 5.22 for T1 vs. T0; overall FCR: d = 4.85 for T1vs. T0), indicating that the replication level was sufficient to detect biologically meaningful responses despite the use of only five replicates per treatment.

4.2 Nutrient digestibility

DM digestibility remained statistically similar across treatments, indicating that vegetable waste and PFA (turmeric and cinnamon extract) inclusion did not adversely affect overall diet digestibility. CP digestibility was higher in T1 and T2 compared to the T0 (control), suggesting improved protein utilization possibly due to the amino acid profile of vegetable waste or the stimulatory effects of bioactive compounds in turmeric powder or cinnamon extract on digestive enzyme activity (42, 43). In addition, bioactive plant polysaccharides present in these additives may enhance gut barrier integrity and nutrient absorption efficiency by modulating intestinal morphology and microbial balance (44). EE digestibility was significantly higher in T2 (P < 0.01), likely reflecting adaptive responses to reduced dietary energy, resulting in enhanced lipid mobilization and utilization. This observation aligns with findings that curcumin supplementation can improve lipid digestion (45). Fiber digestibility, while low in all groups as expected for poultry, was slightly higher in T1. This improvement may be linked to fermentable fiber in vegetable waste, which promotes short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, supporting digestion and nutrient absorption (8, 46). Similar improvements have been reported with Urtica dioica supplementation in broiler diets (40).

4.3 Carcass characteristics

4.3.1 Edible and inedible by-product yields (including gizzard thickness)

Dressing percentage was significantly higher in vegetable waste-formulated groups, with T1 achieving the best values. Notably, T2 maintained comparable dressing percentage to T0 (control) despite reduced dietary energy, indicating that vegetable waste and PFA can sustain carcass yield even under energy restriction. Similar enhancements in carcass traits and dressing yield have been reported with vegetable waste supplementation (41) and with phytogenics such as turmeric (23, 47) and cinnamon (48).

The highest liver percentage was recorded in T1, suggesting enhanced metabolic activity, followed by T2, which may reflect physiological adjustments to reduced energy availability. Increases in liver weight have similarly been reported with nettle supplementation, attributed to carvacrol-induced stimulation of pancreatic secretions (49), and with cinnamon and turmeric inclusion in broiler diets (50).

Gizzard weight and thickness were significantly greater in T1, followed by T2, with T0 recording the lowest values. This can be attributed to the high fiber content of vegetable waste stimulating gizzard muscle activity, thereby improving grinding efficiency and nutrient assimilation (8). Similar findings were reported in a study that observed a significant (p < 0.05) increase in gizzard thickness with cinnamon extract supplementation (18). Abdominal fat percentage was lowest in T1 and T2, indicating reduced fat deposition compared to T0. This effect may result from the combined lipolytic and antioxidant properties of turmeric and cinnamon bioactives, which enhance fat oxidation, limit lipid accumulation, and simultaneously protect tissues from oxidative stress (47, 51).

4.4 Muscle yields

4.4.1 Breast muscle yield

Breast muscle (both deboned and with bone) and pectoralis major yield differed significantly among treatments (P < 0.01). T1 outperformed both T0 and T2, indicating that vegetable waste with cinnamon extract, and turmeric powder enhances muscle growth when ME is maintained. T2 was statistically similar to T0, suggesting that reducing ME by approximately 10% limits muscle development despite supplementation.

The superior breast muscle yield in T1 may result from the synergistic effects of vegetable waste fiber-driven digestive improvements and bioactive compound-mediated lipid mobilization from turmeric powder and cinnamon extract, favoring protein deposition. Cinnamon (18, 60), nettle (52), and turmeric (53) have all been shown to enhance carcass quality and muscle growth, supporting the present findings.

4.4.2 Leg muscle yield

Thigh yield remained statistically similar among treatments, indicating that dietary modifications did not significantly influence thigh muscle growth. In contrast, drumstick percentage and total leg muscle yield differed significantly (P < 0.01), with T1 and T2 recording higher values than T0. This suggests that vegetable waste, combined with Urtica dioica, cinnamon extract, and turmeric powder, enhances muscle deposition by improving nutrient utilization and protein accretion. The ability of alternative feed ingredients to support leg muscle growth without compromising performance aligns with findings on cinnamon supplementation improving thigh muscle yield through enhanced lipid utilization and fatty acid metabolism (16). However, other studies reported no significant effect of cinnamon on carcass traits, indicating that its impact may depend on diet composition and management conditions (33).

Turmeric has also been shown to improve thigh muscle development by promoting nutrient absorption and protein retention (54). The effects of Urtica dioica appear inconsistent; supplementation in broiler diets showed no significant impact on thigh yield (52). In the present study, both T1 and T2 exceeded T0 in leg muscle yield despite the reduced energy in T2, suggesting that vegetable waste and PFA supplementation can offset moderate energy restriction, though optimal results occur when energy is maintained.

4.5 Meat quality

4.5.1 Proximate composition

Breast meat composition showed significant differences in DM, CP, EE, and AIA content, with T1 recording the highest CP values. This improvement may be linked to vegetable waste fiber and nettle's role in reducing nitrogen excretion and enhancing protein utilization (52), cinnamon's capacity to improve protein digestion by increasing hydrochloric acid and pepsin secretion (55), and turmeric's reported effects on CP retention, fat deposition, and meat quality (43).

EE content was highest in T0 and lowest in T2, likely due to reduced energy intake limiting fat deposition. Similar trends were observed in previous work, where cinnamon extract supplementation in low-energy diets resulted in lower meat fat content compared to T0 (control) (18). These findings reinforce the concept that higher dietary energy promotes lipid storage, while lower energy intake reduces EE content, possibly through downregulation of lipogenic pathways and upregulation of fatty acid β-oxidation, as reported by Liu et al. (35). Overall, vegetable waste supplemented with turmeric powder and cinnamon extract improved protein retention and reduced fat deposition, enhancing meat quality even under reduced energy conditions. Furthermore, these improvements in carcass and meat quality may also be associated with enhanced intestinal morphology and antioxidant capacity, which together support better nutrient absorption and tissue integrity (56).

4.5.2 Sensory evaluation

Scores for appearance/color, texture/tenderness, and overall acceptability did not differ significantly among groups, though numerically higher values were observed in T1 compared to T0, with T2 showing the lowest scores. Flavor and juiciness, however, differed significantly (p < 0.05), with T1 and T2 outperforming T0. While these differences were statistically significant, the absolute numerical differences—particularly in flavor (0.6 points) and juiciness (1.0 point) on an 8-point scale—were modest and should be interpreted with caution when evaluating practical sensory benefits. Similar patterns were reported in previous studies, where flavor scores were highest in cinnamon-supplemented low-energy diets, while appearance and tenderness remained unaffected (18). The antioxidant properties of cinnamon (57) and turmeric (19) are known to enhance flavor stability. In the current study, T1 produced meat with the best flavor and juiciness, followed by T2, suggesting that energy restriction slightly attenuates the positive effects of vegetable waste supplemented with turmeric powder and cinnamon extract. Texture, appearance, and overall acceptability remained stable, indicating that the dietary modifications mainly influenced taste-related attributes rather than physical texture.

4.6 Liver enzyme profile

Despite a significant increase in liver weight observed in the T1 group, serum ALT and AST activities remained comparable across all treatments and within established physiological ranges, indicating no hepatocellular damage or leakage. This suggests that the increased liver weight likely reflects an adaptive metabolic response to the inclusion of 15% vegetable waste supplemented with cinnamon (0.1%) and turmeric (0.3%) in the diet, rather than pathological enlargement. These findings align with previous studies reporting that cinnamon supplementation supports liver health in broilers without adverse effects (58, 59). Moreover, the combination of vegetable waste and phytogenic additives appears to maintain normal liver function and overall broiler health.

4.7 Economic efficiency

Although the inclusion of PFA slightly increased feed cost, T1 achieved the highest gross profit percentage due to improved feed conversion efficiency, resulting in superior economic returns compared to the T0 (control) group.

Based on the economic analysis, T1—formulated with vegetable waste supplemented with turmeric powder and cinnamon extract while maintaining ME levels as per ICAR (2013) standards—was the most economically efficient treatment, supported by better feed conversion ratio, higher sale returns, greater gross profit, and superior production efficiency, consistent with earlier findings where cinnamon supplementation enhanced benefit–cost ratio (48) and turmeric inclusion improved profitability in broiler diets (37). T2, while benefiting from reduced feed cost through an approximately 10% lower ME diet, showed moderate performance and reduced profitability due to lower feed efficiency, whereas T0, relying solely on conventional feed ingredients, recorded the least favorable outcomes.

5 Conclusion

Incorporating 15% vegetable waste supplemented with 0.1% cinnamon extract and 0.3% turmeric powder significantly improved growth performance, nutrient digestibility, carcass yield, and economic efficiency in broilers without compromising meat quality. Maintaining ME levels as per ICAR (2013) standards was crucial to maximize these benefits, as excessive energy reduction limited performance. This feeding strategy provides a sustainable and cost-effective approach for broiler production. Future research should explore the long-term effects of such dietary inclusion on gut health and nutrient metabolism. Although the study used five replicates per treatment, the observed differences were associated with very large effect sizes (Cohen's d up to 5.30), supporting the adequacy of the replication level for detecting meaningful improvements in broiler performance.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of Dr. G.C. Negi College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, CSK Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University, Palampur, Himachal Pradesh, India. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. SK: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision. VS: Validation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – review & editing. A: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Validation. ND: Writing – review & editing, Validation. SS: Writing – review & editing, Validation. KK: Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Department of Animal Nutrition at Dr. G.C. Negi College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Chaudhary Sarwan Kumar Agricultural University, Palampur, India, for providing the necessary resources and facilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

Cm, Cost of production per kilogram live weight; Cf, Cost of feed per kilogram.

References

1. United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade (2025). p. 20–1. Available online at: https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2025-04/livestock_poultry_0.pdf (Accessed August 15, 2025)

2. United United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Global Meat Consumption Trends: Pork and Poultry Shares in 2024 (2024). Washington, DC: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online at: https://ask.usda.gov/s/article/What-is-the-most-consumed-meat-in-the-world#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20United%20Nations,goats/sheep%20(5%25) (Accessed August 14, 2025).

3. Bibyan RS, Kour H. PRICE RISE OF POULTRY FEED IS AN ISSUE: How to Economize Poultry Feeding (2024). Karamadai: SR Publications. Available online at: https://www.srpublication.com/price-rise-of-poultry-feed-is-an-issue-how-to-economize-poultry-feeding/#:~:text=The%20feed%20cost%20accounts%20for,major%20constraint%20in%20poultry%20production.

4. panda A, Samal P. Poultry production in India: opportunities and challenges ahead. In: Empowering Farmwomen Through Livestock and Poultry Intervention (2016). p. 12–25.

5. United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste (2024). Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/45230 (Accessed August 15, 2025).

6. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Utilization of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes as Livestock Feed and as Substrates for Generation of Other Value-Added Products. Bangkok: FAO (2013).

7. Truong L, Morash D, Liu Y, King A. Food waste in animal feed with a focus on use for broilers. Int J Recycl Org Waste Agric. (2019) 8:417–29. doi: 10.1007/s40093-019-0276-4

8. Jiménez-Moreno E, Chamorro S, Frikha M, Safaa HM, Lázaro R, Mateos GG. Effects of increasing levels of pea hulls in the diet on productive performance, development of the gastrointestinal tract, and nutrient retention of broilers from one to eighteen days of age. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2011) 168:100–12. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.03.013

9. Kalia A, Joshi B, Mukhija M. Pharmacognostical review of Urtica dioica L. Int J Green Pharm. (2014) 8:201. doi: 10.4103/0973-8258.142669

10. He Y, Guo Y, Liang X, Hu H, Xiong X, Zhou X. Single-cell transcriptome and microbiome profiling uncover ileal immuneimpairment in intrauterine growth-retarded piglets. Curr Pharm Des. (2025). p. 32. Available online at: https://www.eurekaselect.com/243691/article (Accessed November 13, 2025). doi: 10.2174/0113816128411269250707073647

11. Ma L, Lyu W, Zeng T, Wang W, Chen Q, Zhao J, et al. Duck gut metagenome reveals the microbiome signatures linked to intestinal regional, temporal development, and rearing condition. iMeta. (2024) 3:e198. doi: 10.1002/imt2.198

12. Obianwuna UE, Chang X, Oleforuh-Okoleh VU, Onu PN, Zhang H, Qiu K, et al. Phytobiotics in poultry: revolutionizing broiler chicken nutrition with plant-derived gut health enhancers. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. (2024) 15:169. doi: 10.1186/s40104-024-01101-9

13. Hassan F. ul, Liu C, Mehboob M, Bilal RM, Arain MA, Siddique F, et al. Potential of dietary hemp and cannabinoids to modulate immune response to enhance health and performance in animals: opportunities and challenges. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1285052. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1285052

14. Phytogenic Feed Additives Market Size Share Trends Analysis Report By Animal (Poultry Swine Ruminants) By Application (Antimicrobial Effect Digestion Enhancement), et al. Grand view research, Inc. (Animal health); p. 150. Report No.: GVR-4-68040-520-3. Available online at: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/phytogenic-feed-additives-market-report (Accessed August 15, 2025).

15. Knauth P, López ZL, Acevedo-Hernandez G, Sevilla MTE. Cinnamon essential oil: chemical composition and biological activities. In: Essential Oils Production, Applications and Health Benefits. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. (2018). p. chapter 13.

16. Kour J, Daroch N, Parmar N, Dhiman A. Emerging trends in the use of nutraceuticals for improved poultry production. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. (2025) 17:32–47. doi: 10.9734/ejnfs/2025/v17i41677

17. Gholami-Ahangaran M, Rangsaz N, Azizi S. Evaluation of turmeric (Curcuma longa) effect on biochemical and pathological parameters of liver and kidney in chicken aflatoxicosis. Pharm Biol. (2016) 54:780–7. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1080731

18. Sharma S, Katoch S, Snakhyan V, Mane BG, Wadhwa D. Effect of incorporating garlic (Allium sativum) powder and cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) extract in an energy deficient diet on broiler chicken performance, nutrient utilization, haemato-biochemical parameters, carcass characteristics, and economics of production. Anim Nutr Feed Technol. (2023) 23:303–17. doi: 10.5958/0974-181X.2023.00026.4

19. SIAS. The effect of Curcuma longa (tumeric) on overall performance of broiler chickens. Int J Poult Sci. (2003) 2:351–3. doi: 10.3923/ijps.2003.351.353

20. Jimoh FO, Adedapo AA, Afolayan AJ. Comparison of the nutritional value and biological activities of the acetone, methanol and water extracts of the leaves of Solanum nigrum and Leonotis leonorus. Food Chem Toxicol. (2010) 48:964–71. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.01.007

21. Mosha TC, Gaga HE. Nutritive value and effect of blanching on the trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitor activities of selected leafy vegetables. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. (1999) 54:271–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1008157508445

22. Hazarika H, Medhi AK, Ahmed F, Hazarika D, Gogoi AK. Performance of broiler fed on vegetable wastes supplemented diets. ACS Publ. (2014) 30:63–6.

23. Fitasari E, Mushollaeni W. The potential of vegetable waste-based pellets on broiler production performance and nutrient digestibility. IOSR-JAVS. (2020) 13:18–24.

24. Bekele B, Melesse A, Beyan M, berihun K. The effect of feeding stinging nettle (Urtica Simensis S.) leaf meal on feed intake, growth performance and carcass characteristics of hubbard broiler chickens. GJSFR. (2015) 15:1–20.

25. Latimer GW Jr. Official Methods of analysis of AOAC International, 22nd Edn. Rockville, MD, ISBN: AOAC International (2023).

26. Parks P, Dunn D. Evaluation of the molybdovanadate photometric determination of phosphorus in mixed feeds and mineral supplements. J AOAC Int. (1963) 46:836–8. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/46.5.836

27. Lodhi GN, Singh D, Ichhponani JS. Variation in nutrient content of feeding stuffs rich in protein and reassessment of the chemical method for metabolizable energy estimation for poultry. J Agric Sci. (1976) 86:293–303. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600054757

28. Keeton JT. Effects of fat and NaCl/phosphate levels on the chemical and sensory properties of pork patties. J Food Sci. (1983) 48:878–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1983.tb14921.x

29. Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods, 6th Edn. Ames, IA (USA): Iowa State University Press (1967).

30. Bera AK, Bhattacharya D, Pan D, Dhara A, Kumar S, Das SK. Evaluation of Economic Losses due to Coccidiosis in Poultry Industry in India (2010). Available online at: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/92156 (Accessed August 14, 2025).

31. Huff GR, Huff WE, Jalukar S, Oppy J, Rath NC, Packialakshmi B. The effects of yeast feed supplementation on turkey performance and pathogen colonization in a transport stress/Escherichia coli challenge. Poult Sci. (2013) 92:655–62. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02787

32. Mahmoudi M, Azarfar A, Khosravinia H. Partial replacement of dietary methionine with betaine and choline in heat-stressed broiler chickens. J Poult Sci. (2018) 55:28–37. doi: 10.2141/jpsa.0170087

33. Windisch W, Schedle K, Plitzner C, Kroismayr A. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry1. J Anim Sci. (2008) 86:E140–8. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0459

34. Abdelli N, Solà-Oriol D, Pérez JF. Phytogenic feed additives in poultry: achievements, prospective and challenges. Animals. (2021) 11:3471. doi: 10.3390/ani11123471

35. Liu S, Wang K, Lin S, Zhang Z, Cheng M, Hu S, et al. Comparison of the effects between tannins extracted from different natural plants on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immunity, and intestinal flora of broiler chickens. Antioxidants. (2023) 12:441. doi: 10.3390/antiox12020441

36. Behera S, Behera K, Babu L, Nanda S, Biswal G. Effect of supplementation of cinnamon powder on growth performance and FCR in broiler chickens. Int J Livest Res. (2020) 10:225–9. doi: 10.5455/ijlr.20200212053303

37. Choudhury D, Mahanta J, Sapcota D, Saikia B, Islam R. Effect of dietary supplementation of turmeric (Curcuma longa) powder on the performance of commercial broiler chicken. Int J Livest Res. (2018) 8:182. doi: 10.5455/ijlr.20171129032810

38. Attar A, Kermanshahi H, Golian A. Effects of conditioning time and sodium bentonite on pellet quality, growth performance, intestinal morphology and nutrient retention in finisher broilers. Br Poult Sci. (2018) 59:190–7. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2017.1409422

39. Chowdhury S, Mandal GP, Patra AK. Different essential oils in diets of chickens: 1. Growth performance, nutrient utilisation, nitrogen excretion, carcass traits and chemical composition of meat. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2018) 236:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.12.002

40. Gao Y, Yang X, Chen B, Leng H, Zhang J. The biological function of Urtica spp. and its application in poultry, fish and livestock. Front Vet Sci. (2024) 11:1430362. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1430362

41. Raza A, Hussain J, Hussnain F, Zahra F, Mehmood S, Mahmud A, et al. Vegetable waste inclusion in broiler diets and its effect on growth performance, blood metabolites, immunity, meat mineral content and lipid oxidation status. Braz J Poult Sci. (2019) 21:eRBCA-2019-0723. doi: 10.1590/1806-9061-2018-0723

42. Samarasinghe K, Wenk C, Silva KFST, Gunasekera JMDM. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) root powder and Mannan oligosaccharides as alternatives to antibiotics in broiler chicken diets. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. (2003) 16:1495–500. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2003.1495

43. Singh PK, Kumar A, Tiwari DP, Kumar A, Palod J. Effect of graded levels of dietary turmeric (Curcuma longa) powder on performance of broiler chicken. Indian J Anim Nutr. (2018) 35:428. doi: 10.5958/2231-6744.2018.00065.8

44. Sun W, Jia J, Liu G, Liang S, Huang Y, Xin M, et al. Polysaccharides extracted from old stalks of Asparagus officinalis L. improve nonalcoholic fatty liver by increasing the gut butyric acid content and improving gut barrier function. J Agric Food Chem. (2025) 73:6632–45. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c07078

45. Rajput N, Muhammad N, Yan R, Zhong X, Wang T. Effect of dietary supplementation of curcumin on growth performance, intestinal morphology and nutrients utilization of broiler chicks. J Poult Sci. (2013) 50:44–52. doi: 10.2141/jpsa.0120065

46. Jha R, Berrocoso JFD. Dietary fiber and protein fermentation in the intestine of swine and their interactive effects on gut health and on the environment: A review. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2016) 212:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.12.002

47. Mondal M, Yeasmin T, Karim R, Siddiqui MN, Nabi SR, Sayed M, et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of turmeric (Curcuma longa) powder on the growth performance and carcass traits of broiler chicks. SAARC J Agric. (2015) 13:188–99. doi: 10.3329/sja.v13i1.24191

48. Gaikwad DS, Fulpagare YG, Bhoite UY, Deokar DK, Nimbalkar CA. Effect of dietary supplementation of ginger and cinnamon on growth performance and economics of broiler production. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. (2019) 8:1849–57. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2019.803.219

49. Gul ST, Raza R, Hannan A, Khaliq S, Waheed N, Aderibigbe A. potential of a medicinal plant Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) as a feed additive for animals and birds: a review. Agrobiol Rec. (2024) 17:110–8. doi: 10.47278/journal.abr/2024.029

50. El-Maaty A, Hayam MA, Rabie MH, El-Khateeb AY. Response of heat-stressed broiler chicks to dietary supplementation with some commercial herbs. Asian J Anim Vet Adv. (2014) 9:743–55. doi: 10.3923/ajava.2014.743.755

51. Eevuri T, Putturu R. Use of certain herbal preparations in broiler feeds—a review. Vet World. (2013) 6:172–9. doi: 10.5455/vetworld.2013.172-179

52. Puvača N, Roljević Nikolić S, Lika E, Shtylla Kika T, Giannenas I, Nikolova N, et al. Effect of the nettle essential oil (Urtica dioica L.) on the Performance and Carcass Quality Traits in Broiler Chickens: Nettle essential oil in broilers diet. J Hell Vet Med Soc. (2023) 74:5781–8. doi: 10.12681/jhvms.30264

53. Wang D, Huang H, Zhou L, Li W, Zhou H, Hou G, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation with turmeric rhizome extract on growth performance, carcass characteristics, antioxidant capability, and meat quality of Wenchang broiler chickens. Ital J Anim Sci. (2015) 14:3870. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2015.3870

54. Yasmeen R. Effect of Curcuma Longa on growth and lipid profile of broiler chickens across seasons. J Bioresour Manag. (2024) 11:21–6. doi: 10.52057/jbm.v11i3.21

55. Mountzouris KC, Paraskevas V, Tsirtsikos P, Palamidi I, Steiner T, Schatzmayr G, et al. Assessment of a phytogenic feed additive effect on broiler growth performance, nutrient digestibility and caecal microflora composition. Anim Feed Sci Technol. (2011) 168:223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.03.020

56. Chen J, Chen F, Peng S, Ou Y, He B, Li Y, et al. Effects of Artemisia argyi powder on egg quality, antioxidant capacity, and intestinal development of roman laying hens. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:902568. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.902568

57. Singh J, Sethi APS, Sikka SS, Chatli MK, Kumar P. Effect of cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia) powder as a phytobiotic growth promoter in commercial broiler chickens. Anim Nutr Feed Technol. (2014) 14:471. doi: 10.5958/0974-181X.2014.01349.3

58. Toghyani M, Toghyani M, Gheisari A, Ghalamkari G, Eghbalsaied S. Evaluation of cinnamon and garlic as antibiotic growth promoter substitutions on performance, immune responses, serum biochemical and haematological parameters in broiler chicks. Livest Sci. (2011) 138:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2010.12.018

59. Koochaksaraie R, Irani M, Gharavysi S. The effects of cinnamon powder feeding on some blood metabolites in broiler chicks. Rev Bras Ciênc Avícola. (2011) 13:197–202. doi: 10.1590/S1516-635X2011000300006

Keywords: turmeric powder, cinnamon extract, nutrient digestibility, metabolizable energy, Urtica dioica (nettle), broilers

Citation: Kour J, Katoch S, Sankhyan V, Suman M, Dhiman A, Daroch N, Sharma S and Katkar K (2025) Vegetable waste-based diet supplemented with phytogenic feed additives improves growth performance, carcass characteristics, and economic efficiency in broilers under varying energy densities. Front. Vet. Sci. 12:1688247. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1688247

Received: 18 August 2025; Revised: 25 November 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025;

Published: 17 December 2025.

Edited by:

Matteo Dell'Anno, University of Messina, ItalyReviewed by:

Zhen Dong, Hunan Agricultural University, ChinaShahid Ali Rajput, Muhammad Nawaz Shareef University of Agriculture, Pakistan

Copyright © 2025 Kour, Katoch, Sankhyan, Suman, Dhiman, Daroch, Sharma and Katkar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jalmeen Kour, amFsbWVlbjFrb3VyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†Present address: Shubhani Sharma, ICAR National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana, India

Jalmeen Kour

Jalmeen Kour Shivani Katoch

Shivani Katoch Varun Sankhyan

Varun Sankhyan Madhu Suman

Madhu Suman Abhishek Dhiman

Abhishek Dhiman Nidhi Daroch

Nidhi Daroch Shubhani Sharma

Shubhani Sharma Kshitij Katkar

Kshitij Katkar