- 1Infectious and Tropical Disease Institute, Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH, United States

- 2School of Communication Studies, Ohio University, Athens, OH, United States

- 3Department of Communication, California State University, Fresno, CA, United States

- 4Centro de Investigación para la Salud en América Latina (CISeAL), Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador

- 5College of Exact and Natural Sciences, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador

Chagas disease is a neglected tropical disease that disproportionately affects impoverished rural communities. Insecticide-based approaches are inconsistently performed and exorbitantly priced for the communities affected. The present study considers an alternative approach to primary prevention of Chagas disease using entertainment education. As part of an ongoing effort in rural Ecuador, we worked with the children of the community of Guara, national insect control workers, and academicians to co-develop a song to promote behaviors related to preventing Chagas. Through an analysis of the song, we demonstrate opportunities for meaningful intervention in rural communities, as well as challenges to implementing an entertainment education approach when working with national stakeholders.

Introduction

Chagas disease is a disease caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. This parasite infects ~6–7 million people, mostly in the American Continent (WHO, 2018). The main route of transmission of this parasite is via the infected feces of Triatomine bugs. Triatomine bugs, known as “chinchorros” or “chinches” in Ecuador (and by other names in other places), feed on the blood of mammals, including humans, and defecate near the site of the bite. People introduce the infected feces into the bite site, eyes, or other mucosal surfaces when they scratch. The parasite gains entry to the bloodstream and infects many organs. The initial infection can be asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms, such as fever, malaise, headache, or lack of appetite. When present, these disappear within a month or two; however, low-level infection remains in certain organs, such as the heart and the nervous system. The continuous, albeit slow, destruction of the tissues by the parasite, compounded by the patient's own immune response, causes damage to the tissues. Over 5–20 years, these changes remain unnoticed, until the damage is such that apparent chronic symptoms of Chagas disease appear. Progressive debilitating heart disease occurs and can lead to disability or death. In addition, the parasites can destroy the neurons that control the movement of the digestive system. This causes a progressive enlargement of the esophagus or colon. Known as mega syndromes, the massive size of the these organs results in difficulty swallowing, chronic constipation and, due to the volume they occupy in the chest and abdomen, can severely interfere with normal cardiorespiratory function (WHO, 2002).

Chagas disease is endemic in Loja Province, located in southern Ecuador. This province has one of the highest poverty rates in the country (INEC, 2010). Triatomines were found in 68% of communities located in sub-tropical areas of the province (Grijalva et al., 2015). In some communities, infestation of houses reached up to 48%. Outside of the house, bugs colonize chicken nests, Guinea pig pens, rodent nests, and places were domestic animals rest. Inside the home, bugs are often found in the bedroom, in deep cracks found in adobe walls, under the mattress or bedding, or under accumulation of clothes or other items near the bed. It is not uncommon for chickens or guinea pigs to be kept inside the house for protection. In these cases, bugs are commonly found where they nest or sleep. Control programs rely on insecticide spraying of the houses by personnel from the National Chagas Control Program and community education. However, due to the presence of wild populations of bugs associated with squirrel and bird nests (Grijalva et al., 2012), frequent reinfestation of the houses occurs soon after the residual effect of the insecticide subsides (Grijalva et al., 2011). Moreover, while most of the population is aware of the presence of bugs in their houses, they do not know that “chinchorros” can transmit Chagas disease. Due to lack of allocated resources and political decision, visits by the control program personnel to rural communities in Loja province are infrequent. Therefore, knowledge about the dangers of having bugs in and around the house, how the disease is transmitted, and what the inhabitants can do to protect themselves is paramount to prevent transmission (Patterson et al., 2018).

Because Chagas disease is largely invisible, and because there are few effective treatments, primary prevention is necessary. Primary prevention is an intervention that occurs before a health effect occurs, such as vaccination, elimination of substances known to be associated with a disease, or through altering risky behaviors (Reisig and Wildner, 2008). Unfortunately, because it is a neglected tropical disease, a disease that affects economically and geographically marginalized people, there is a long history of systemic underinvestment in efforts to prevent the transmission of Chagas disease (Molyneaux et al., 2016). In the present study, we discuss one communication intervention that attempts to promote primary prevention of Chagas disease. Specifically, working with children in the community of Guara, a small community in Loja Province, Ecuador, we co-created a song that raises knowledge of easily implemented home-based practices that can prevent infestation by triatomine bugs and, thus, reduce exposure to the vectors for Chagas disease. We begin with a discussion of our approach, an approach based in principles of Entertainment-Education with an emphasis on the song tradition. We then discuss the creation of the song to promote behavioral changes regarding Chagas and provide an analysis of this song and its messages. Finally, we offer some implications that this co-participatory process has for implementing Entertainment-Education strategies in the context of neglected tropical diseases.

Entertainment-Education and Performance for Social Change

Entertainment-Education (E-E), is a field devoted to using entertainment such as large-scale media (films, broadcast, radio, and television programs) and live performances for education. E-E scholars all over the world have done research on various entertainment programs, and how these programs have educated audiences and have supported pro-social change (Sabido, 1989; Wallack, 1990; Nariman, 1993; Piowtrow et al., 1997; Singhal and Rogers, 1999). Some of these programs are purposely designed by change agencies; other programs that were produced just for entertainment have had unintended positive effects on audiences' thoughts and behaviors. The success of these programs has inspired governments and non-profit organizations to purposefully design entertainment-education projects.

A classic example from Latin America often cited by E-E scholars is the telenovela “Simplemente Maria.” Simplemente Maria showed a young woman who achieved success by learning how to read and to sew. Researchers say that, as a result of Simplemente Maria's popularity, literacy classes became very popular in Peru and the Singer sewing machine's sales broke records (Simplemente absurdo, 1970; Vasquez, 1970; “Simplemente Maria” se acabo, 1971; Singhal et al., 1994). E-E scholars have also cited the popularity of Miguel Sabido's (1989) Mexican soap opera as Ven Conmigo Population Communication International's Indian soap opera Hum Log (Singhal and Rogers, 1988). In addition to studies of classical cases of E-E, many recent projects have used Entertainment-Education for change (Communication Initiative, 2011), including efforts in India to promote HIV/AIDS awareness (BBC, 2006), in Colombia to support healthier sexualities and gender relations (Igartua and Vega, 2014), and in Ukraine to address the dangers of land mines (Prokhorov, 2018).

Non-Broadcast Entertainment-Education Though Performance

One weakness of E-E scholarship, however, is that most E-E scholarship has focused on broadcast media such as television and radio or on music albums. Live performance, such as songs and theater performed among community inviting direct audience participation, has less often been researched or discussed. However, scholars of “performance theory” or more specifically, “performance for social change” have attended to various performances projects that have tried to educate and bring directed change in their audiences' thoughts and behavior. Dwight Conquergood (1988), a leading theorist of performance studies states:

…deCerteau's aphorism, “what the map cuts up, the story cuts across” also points to transgressive travel between two different domains of knowledge: one official, objective, and abstract- “the map”; the other one practical, embodied, and popular- “the story.” This promiscuous traffic between different ways of knowing carries the most radical promise of performance studies. Performance studies struggles to open the space between analysis and action. (p. 1)

Enacting this paradigm, Conquergood (2002) directed and helped to design live performances in a Hmong refugee campaign in Thailand. Specifically, Conquergood (1988), with his team, produced skits and scenarios drawing on Hmong folklore and folk singing to develop awareness about health problems. Following Conquergood, Sharma (2012) designed and directed a live song and theater campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. The campaign developed 15 scripts containing health message in different song and theater genres of Northern India, and more than 150 professional troupes were trained to perform these scripts.

In Latin America, entertainment-education through performance (theater songs, and other forms) has a long history. Latin America may be the place where live performance is used the most to educate and effect thought and behavioral change. As early as the 1970s, the University of California Los Angeles' Latin American Center “document[ed] and analyze[d] the role of the theater and other dramatic and paradramatic arts, such as cinema, television, dance, and song, as pedagogical tools for literacy and health campaigns, occupational and citizenship training, and also as motivational agents for social change” (Luzuriaga, 1978, p. 11). According to this research, performances (in its various forms) have played important educational role over the course of the Latin American history from the time of the Incan Empire to the present. Drawing on this tradition, teatro infantile, or “the theater for the children,” has been widely employed by ministries of education all over Latin America, and many plays for children, which were educative but “mainly” entertaining, were published. Teatro Infantile was also used in teaching children and also to educate them in social attitudes and ideologies much beyond the overt social issues (Luzuriaga, 1978).

Since 1960s, Paulo Freire's philosophy of concientización or critical pedagogy discussed in his books, (Freire, 1970, 1973), has influenced Latin American Theater for social change deeply in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Argentina, Peru, and other countries. Freire argues that an education that emphasizes critical thinking and awareness is the only way to liberate the oppressed people. Theater scholars and directors, such as Augusto Boal and Enrique Buenaventura (Luzuriaga, 1978), have used Freire's philosophy in their theater and performance work for education. Buenaventura worked on the method of “collective creation,” which is also known as Buenaventura Method. In this method the play is written collectively by the participants, rather than following the usual text-director-performers-process, which has a designated playwright and a director who directs designated performers (Luzuriaga, 1978). This method of performing for education and social change has become very popular all over the Latin America. One of Boal's (1993) experiments in popular theater was done in Peru where theater was used as a part of an official literacy campaign called ALFIN (Peración Integral). The campaign was based on Freire's pedagogy. In this project, along with theater, Boal also used other participatory methods such as photography and the puppet theater. Boal showed through this campaign that theater can be used as self-expression by the oppressed, and can help them to change their outlook from passivity toward things to the one of active participation and dramatic action. Boal called this kind of theater as truly educational or the “the theater of conscientization.”

This use of theater and other performance modalities for education has been since been very popular in the Latin America (McCarthy and Galvão, 2004). Through the work of these performer-thinkers, we see that there are local traditions of using performance, bringing awareness, and educating masses about political and social issues in global South. This work is distinct from the dominant Entertainment-Education initiatives supported by organizations situated in the first world or the global North.

The Use of Theater and “Song” Tradition for Education and Social Change in Latin America

The Use of Songs

Latin America is one of the few places where the “song” tradition has a very distinct place in the performance landscape and been used for social and political education and change. In the 20th century, almost all countries in Latin America have had their own “new song” movements that started in response, and in support of, progressive change. Examples include: “Nueva Canción Chilena” (Chilean New Song); “Canto Popular” (Popular Song) in Uruguay, and “Movimiento del Nuevo Cancionero” (the New Song Movement) in Argentina. The new song movements originated in 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s during a profound time of social change, including the Cuban revolution and guerrilla movements in Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Colombia, and most of Central America, and resistance to the socialist regime in Chile (Villa, 2014). However, the effects of these song movements for change has continued to impact the communication for educating people about new issues in Latin America to the present. Shaw (2014) argues:

Song can help give a voice to a people who otherwise are not heard, can help to amplify that voice, and can help create solidarity. By merely proposing questions pertaining to our circumstances, a song has the power to shift people's consciousness and create a vision for a better world. So though a song's reception is unique to each listener, there is potential for a communal experience. (p. 1)

“Song” can be an ideal medium for people to raise community issues such as health and social behaviors in front of their own community, as it is a medium is that combines lyrics, melody, and rhythm located in a specific place and moment in time to prompt community engagement, promote retention of the messages, and to speak in the language of its audience (Shaw, 2014).

Thus, song can get audiences to understand and remember the messages in a very effective way. Many musicians have used song to call their audiences' attention to social, political, and educative issues in Latin America (e.g., Blades, 2009; Brown, 2010; Brown et al., 2010). In addition to songs that are written to appeal across sections of society, other artists choose to target specific subpopulations that they feel can enact change, for example, rapper Tijoux's (2012) appeal to students in Chile or Zapotec rapper Mare's (2012) address of indigenous women in Mexico. Many scholars have tried to analyze the work of various artists and their songs in different Latin American countries in the context of socio-economic change, including Puerto Rico (Esterrich, 2014), Brazil (Chidester and Baldwin, 2014), and Mexico (Corona, 2014). Others have examined how song addresses specific issues like environmental degradation in Costa Rica (Ureña, 2014), youth issues in Argentina, Chile, and Peru (Balabarca, 2014), and resistance to imperialism in Cuba (Shaw, 2014). Thus, we see the tradition of “song” has been widely popular in Latin America to educate communities for change.

As community-based researchers and activists who believe that communities must be involved in their own social change, we believed that the song tradition was a strong and effective platform for continuing our work. Indeed, although they have not been subject to formal analysis, the potential for songs to be used in the fight against Chagas Disease has been recognized, for example, in local projects, such as Manos Unidas's efforts in Canton El Pinalito, Santa Ana (FUNDASAL – EL SALVADOR, 2010) and Medicos Sin Fronteras's work in Olopa, Chiquimula (junnaka, 2006), both in El Salvador, as well as Leo Messi and FC Barcelona's use of “Las palabras no dan miedo” (“Words are not scary”) in their efforts to raise awareness of the disease throughout the Spanish speaking world (FC Barcelona, 2016). Each of these groups has used song to promote awareness of the dangers of Chagas disease. Drawing on this tradition, and song's record of promoting participation in the creation of messages to promote health, we engaged in a co-participatory message design process to create a song with children to promote Chagas disease prevention.

Our Positions in This Tradition

It would be important here to mention that we, as authors and activists, believe and belong to a bottom-up local paradigm of performance that originates from community, and from the performers, writers, and directors working with local people. The first author of this study first trained as a rhetorical scholar who examined texts as others had produced them. Informed by principles from communication activism, he has increasingly seen the role of rhetorical scholars as producers of texts for social impact. Moreover, drawing on a community asset-based development perspective, he seeks actively to set aside deficit-based perspective he learned in the Global North to emphasize strengths within communities and the voices in those communities that express those strengths. The second author of this essay is a fifth-generation folk performer belonging to the Swang (musical theater) tradition of northern India. His father is a renowned Swang artist, and the second author grew up performing with his father and other socially engaged performer/writers and directors. The third and fourth authors are citizens and scholars from Ecuador. They have worked with members of rural communities affected by Chagas disease in Ecuador for nearly two decades. Although trained as a biological scientist, the third author has increasingly turned to audio and video production to tell stories of people in the community and to document the work performed by our study group by and with community members. The fourth author, also a biological scientist, first engaged members of the community through standard clinical approaches; he performed blood draws, examined the samples for parasites, and reported the results to the Ministry of Health. After realizing that this top-down approach did not necessarily equate to government action within highly impacted communities, he turned to more participatory and community-centered approaches to both the investigation of and proposing solutions to socioecological factors identified by community members as essential to primary prevention of Chagas disease.

Co-Participatory Message Design Process

The Government of Ecuador and the Provincial Government in Loja have longstanding programs to bring pesticide spraying to homes. These programs, however, require that individual families admit workers from the Servicio Nacional de Control de Enfermedades Transmitidas por Vectores Artrópodos (SNEM: National Service for the Control of Arthopod Vectors of Infectious Disease) and its successor agencies into their homes. The idea of addressing home access through children's attitudes was articulated by the fourth author in May 2010. The third and fourth authors consulted with approximately a dozen school teachers, more than 20 Ministry of Health workers, and other individuals in the communities who interacted with youth to investigate the messages that would be most likely to help children learn to identify the triatomine bug and to encourage their parents and other caregivers to work toward the prevention of infestation (unpublished). The recommendations included avoiding technical jargon, the use of vernacular expressions common to the rural population on this region of Loja province and the use of active learning tools to impart the knowledge to the children in the communities. This consultation process also led the authors think that a different approach was needed to attract the attention of children and, consequently, promoting their active role in the prevention of Chagas disease in their households. While this consultation in June 2010 was useful, the third and fourth authors did not feel that they were making much progress in identifying word choices or messages that would be persuasive to the children.

Therefore, facilitated by Ohio University and Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador students, the third and fourth authors turned to the children themselves to shed light on what the most significant messages for the children would be. After engaging in a community and verbal parental consent process approved by the institutional review board of Ohio University and the Comité de Ética de la Investigación en Seres Humanos at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, the research team began to work with 10 children ages 6–12 to design messages. In Loja province, specifically the communities of Chaquizhca and Guara, the third and fourth authors (along with students from both Universities and staff from SNEM and the larger project) visited with children in their schools and homes. The team sought to record the children's impressions of what constituted a healthy home, what people could do to make their homes healthier, and how insects played a role in keeping children and their families healthy. Many of the children were initially shy or afraid of the research team, but, after engaging in constructive play and with the presence of parents and teachers, the children opened up and articulated comments on each issue. Significantly, although parents and teachers were present, they were not included in the generation of ideas for how to communicate these messages. The children identified the best way to help them learn more about the insects. Specifically, they said that a song that they could easily learn would help them remember important things about preventing the insects' infestation.

All 10 children in the school were invited to participate and permission was given by their parents for their participation. There were no incentives given for participation, and no parents remained for the further activities with the children. Supervised by the schoolteacher, the research team then met in the classroom with ten children from Guara School for several hours where they first watched an educational video and worked with a booklet related to Chagas disease. The booklet included factual and cartoon-based information about the disease and activities such as cut and paste, number coloring, word-soup, and labyrinth aimed to reinforce knowledge about the Chagas disease transmission and preventive actions that can be undertaken by the family. Finally, bilingual members of the research team engaged the children in active conversation in Spanish regarding what the children considered the most important messages. Field notes were taken during this activity.

Three key issues that deserved attention emerged: identifying the presence of insects in the home; promoting awareness that they were biting insects; and, naming practical behaviors that could prevent infestations. Once the critical issues for preventing triatomine infestation were identified, the research team organized a song around these themes. For each issue named by the children, subject matter specialists from the team contributed advice. These specialists included infectious disease researchers (5), physicians (2), public health experts (2), and governmental workers (2). The subject matter experts assessed how prevalent the health practices were in the community and the efficacy of the various solutions named by the children. The key was to identify common themes the children articulated with evidence-based solutions for excluding or killing the bugs. Following the initial drafting of the song, which at that point contained three verses, the team sought feedback from SNEM, the agency responsible for eliminating triatomine infestation. SNEM requested an additional verse that would highlight and increase acceptability of SNEM's efforts, and the team added it. The added verse was brought back to the children, who did not have any objections to its addition.

The song was brought back to the community in July 2010. Children of Guara community performed the song at the school, and the children were encouraged to bring it home and teach it to other members of the family. Because the song was deployed along with other strategies—including classroom education, media efforts, public health education, community theater, graffiti, and more—it is not possible to assess the impact of the song on children's knowledge, attitude or practices. It is possible, however, to examine the messages themselves and identify promising opportunities for the community.

Analysis of the Song

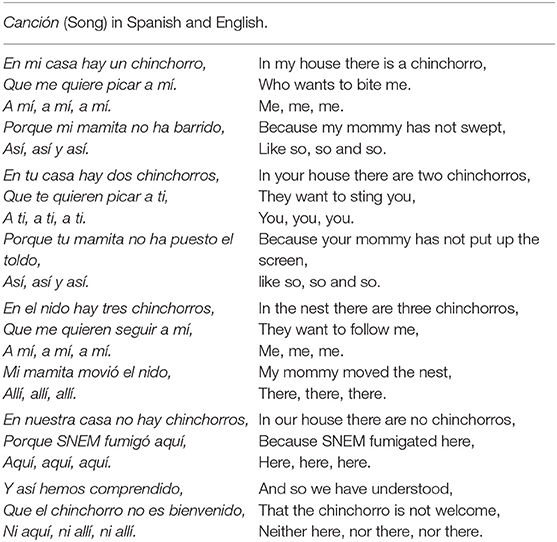

The song generated in coordination with the children is comprised of four stanzas (see Appendix A). The first three stanzas indicate some of the household management behaviors that the children identified as common in the communities and that raise the risk of being bitten by a tritominae bug. Each of these stanzas follows a pattern. First, the presence of the bug is identified (“In my house there is a Chinchorro,” “… are two chinchorros,” “… are three chinchorros”), and the number of insects found in the home grows larger each time. This move not only identifies the insect as common and present in many homes through the communities, it also makes the insect identifiable by its common name. Rather than naming the specific species of bug that might be found, the children use the local term “chinchorro.” After identifying the insect's presence, the next line of each stanza indicates that the insect is one that bites, that the bug is one “who wants to bite me,” “to sting you,” and “to follow me.” The presentation of the insect as one that bites reflects the transmission of disease via the triatomine bug; to contract Chagas' disease, the insect bites to feed and defecates on the host at the same time, and when the host scratches the bite, she or he rubs the feces into her skin and begins the infection cycle anew. The bugs are not passive feeders that bite only out of opportunity; they will emerge from hiding places at night and “follow” their hosts into bed for feeding. Although Chagas is pernicious, contracting it generally requires repeated exposure to the triatomine bite and the parasite contained within its feces. The children recognize this when the bite is repeated with “me, me, me” and “you, you, you” in the third line of each stanza. The children, then, create additional perceptions of greater susceptibility to contracting Chagas' disease because the risk of exposure is repeated.

The susceptibility comes not only from the bite, but from behaviors in the household that create a greater likelihood of triatomine infestation. In the first stanza, the children say a single chinchorro is present “because my mommy has not swept.” In the second stanza, two chinchorros are present “because your mommy has not set up the screens.” And, in the third stanza, three bugs are in a chicken nest and they were removed when “my mommy moved the nest.” Importantly, each behavior is one that must be repeated for it to be effective. This is indicated in the “so, and so, and so” of the first two stanzas where the children also make sweeping motions and pretend to erect netting, respectively, and the “there, there, there” of the third where the children also make pointing motions to show the chicken nest should be moved far away). Each of these behaviors affect the likelihood of infestations; they also require some knowledge of local strategies for insect control. Sweeping the home removes household debris and makes it easier to see signs of triatomine infestation, such as their droppings or carcasses. In addition, the brooms for sweeping in Calvas County are often made from local bushes that have a large amount of acid in their stems (Nieto-Sanchez et al., 2015). Thus, in addition to mechanically destroying nests by sweeping, the acid in the broom can work as a natural insecticide that may prevent reinfestation. Putting up screens may prevent problems of triatomine infestation as well. Although the words did not specify whether the screens represent bug nets erected over the individual bed or screens on windows and doorways into the home, the actions performed as part of the song mime erecting bug nets. Bug nets placed over the individual bed can prevent the transmission of Chagas because the bugs, which generally live in cracks in the home wall or behind picture frames and similar hiding places, cannot get to the body to bite it. If a person hears only the words, an alternative interpretation of placing window screens is also efficacious. Window screens also limit introduction of the insect into the home, as they provide a physical barrier to entry. Whereas, sweeping can remove nests after infestation, screening can prevent the establishment of nest or prevent the bugs from feeding should infestation have already occurred. Finally, even with screening, if an existing chicken nest containing triatomines is not moved outside the home or away from the walls of the home, infestation can occur. It is important then to move nests when one is collecting eggs or raising fighting birds away from the peridomicile and certainly not into the domicile. All three of these strategies are simple behaviors to adopt: sweeping, setting up screens or netting, and moving chicken nests containing chinchorros can easily be performed. It is also important to note the agent to whose this responsibility is assigned: to mommy. Prevention of Chagas becomes a feminine act, specifically a maternal one. Although men (and elders and children) are certainly capable of picking up a broom, the children articulate social norms that make household maintenance the responsibility of women.

Taken collectively, the first three stanzas, first, highlight the presence of infestation, then, indicate the general problem of transmission as well as the individual child's susceptibility to transmission, to locate infestation as a common problem (for me and you), and, finally, indicate the act of that can be performed to lessen infestation as well as its repeatability. The children's stanzas reflect concepts common in health communication theories for promoting behavioral change. The presence of the bug reflects awareness, the representation of transmission reflects perceived susceptibility, and the means of prevention reflect efficacy. The children, then, have identified important facets of promoting health behavior change in Guara that can be message points for a campaign to spread their message.

This community-centered and community-articulated pathway, however, becomes disrupted in the fourth stanza of the song. In the fourth stanza, we are told about a house in which there are no triatomines. The reason that the fourth house has no bugs is not because of sweeping or netting or individual change; rather; this home is bug-free “because SNEM fumigates here.” SNEM, the acronym for the now disbanded Servicio Nacional de Control de Enfermedades Transmitidas por Vectores Artrópodos (National Service for the Control of Arthopod Vectors of Infectious Disease), was a nation-wide agency, not an agency based in Calvas County or the community of Guara. In addition to being geographically distant, the solution they provide is insecticide spraying. Spraying is described as an ongoing act, however it should be noted that insecticide must be repeatedly applied with specialized equipment and is very expensive when compared with the average household income in the community. Because of the change in agent (from mother to outside government workers) and the change in act (from the simple and easily accomplished to the expert and expensive), the efficacy, in both perceived and actual terms, of the strategy for eliminating triatomine bugs changes. Indeed, the focus on spraying likely lessens the self-efficacy of families responding to the song. The target of persuasion and the goal of persuasion also changes. The first three verses implied that the family, specifically, the mother, should change behavior. The final verse indicates that the desired outcome is that “we have understood that the chinchorro is not welcome, neither here, nor there, nor there.” This outcome is a change in attitude rather than a change of behavior, the change in attitude occurs among the children themselves rather than in the family unit. In this final stanza, then, confusion is introduced as to who is responsible for preventing infestations, how they prevent infestation, and the role of community members in this prevention.

This change was introduced after the children had generated their topics and the initial parts of the song. Because the larger research project of which this song is a part also included staff of SNEM, when the children's topics were formalized into the song, the SNEM members sought additional inclusion of their efforts into the song. This insistence, in part, allows the song to recognize the important contributions that SNEM and the Ministry of Health have made to prevention of Chagas disease but also, in part, distracts from the voice of the community by displacing their community-based suggestions with solutions offered by the central government.

Discussion and Implications

The use of the Entertainment Education approach in Guara reveals a potentially powerful way of bringing children into the construction of their own health interventions. This song brings Entertainment Education to the context of neglected tropical diseases. As such, our analysis of the song and its development may provide important insights for other practitioners who wish to incorporate this longstanding and powerful form of intervention in the neglected tropical disease context.

The most important lesson is that, in the novel context of Chagas disease, entertainment education can serve as a powerful intervention. Co-creation of this song allowed members of the community in Guara to promote understanding of effective and efficacious personal strategies to combat the spread of triatomine vectors for Chagas disease. Through their co-participation in writing this song, the children emphasized messages about actions they and their families could take. Efforts in communities like Guara have tended to emphasize vector control through insecticide application (e.g., Samuels et al., 2013), but insecticide-based strategies are limited both by difficulties in complete and proper application and by recolonization of homes after the insecticide wears off. We agree with Grijalva et al. (2011) that the most effective intervention will not be the development of a better insecticide but, rather, changes in household behaviors and practices that will prevent initial colonization of the home. Field workers from SNEM generally recognize that lack of financial resources, personnel and the difficulty access to the households in the communities makes it operationally difficult to provide regular insecticide application in rural areas of Ecuador. Therefore, they welcomed the use of community education and entertainment education to promote community-based disease prevention. However, to our knowledge alternative prevention methods have not been implemented to date. Furthermore, since SNEM was disbanded in 2016, systematic Chagas disease control activities have practically ceased in the country (Dumonteil et al., 2016).

Previous research (e.g., Patterson et al., 2018) has approached communities in Loja province to understand the actions and activities members of the community believe will help reduce the risk of Chagas disease. Because the song developed in cooperation with the children promotes these changes and activities—specifically, regular sweeping, using screens, and moving chicken nests away from the domicile—it may be an effective way to communicate these behavioral changes to other members of the community. Moreover, because the song was developed with the children, it is more likely to use language that the community employs and be more understandable to residents of Guara than messages developed outside of the community. And, because a co-participatory approach draws ideas for messaging and insight into lived conditions in a way that top-down approaches do not, participatory approaches are more likely to be more effective than top-down communication approaches (Singhal and Rattine-Flaherty, 2006). Because the song developed with the children adopts a participatory communication approach, it is likely to empower children and the community of Guara to exert control over a significant health threat (see Singhal, 2001).

These potentials for entertainment education approaches encourage us to understand how people assert control in their local communities. EE approaches encourage us to listen to the community to emphasize local knowledge and norms, but also to understand whether there are harmful norms in the community that provide potential loci for change (Riley et al., 2017). In the song developed here, potential harmful norms might exist concerning perceptions of gender roles. Throughout the verses created by the children, bugs can bite children because of the mother's inaction (“mommy has not swept” and “mommy has not set up the screens”) or are protected when “my mommy moved the nest.” These verses reflect traditional Ecuadoran assumption that women are responsible for the care of families and upbringing of children while men are able to be less active in parenting. Men are just as capable of sweeping floors, erecting screens, and moving chicken nests as women are, but the children do not make fathers responsible for doing these things. Because the children indicated that mothers were important in the prevention of Chagas disease, future efforts in Guara, or in other communities where this approach is adopted, would benefit from including parents in the co-creation of the Entertainment-Education intervention. This inclusion, particularly of mothers, might allow all key players in the community to be involved in construing the messages. Although there are anthropological and sociological explanations for the emergence of these gender roles, the children's communicative choices reveal an important site of intervention for broader social change and possibilities in rural Ecuador, albeit one that should be revisited in future efforts.

In addition to limitations that come from these gender norms, the song was limited in that it returned to an insecticide-based strategy in the final verse. Over the course of the development of the song, public health experts insisted that we add a line that highlighted the work of their spraying program. To retain the support of the Ministry of Health and other governmental actors, we acquiesced, and this action nay have detracted from a central principle in participatory methods that the voice of the community should be privileged over that of the experts. Because this intervention was, however, a co-participatory design, we partially avoided many of the problems associated with top-down approaches. Entertainment Education approaches were initially theorized as being either top-down or bottom-up (Singhal and Rogers, 2001), and many early studies of EE efforts have sorted themselves into being either national (top-down) or cultural/local (bottom-up) campaigns (see Singhal and Rogers, 2002 for a review). Yet, as Riley et al. (2017) demonstrate, this dichotomization has been shown to be false; when entertainment education has been put into practice over the past two decades, a continuum between a more top-down and a more bottom-up approach has emerged.

Because our project was a true cooperation between our research group, SNEM, and the community, our project sought to incorporate the voices of SNEM members alongside those of the community. The SNEM team is correct that spraying the house does kill most triatomines and can complement well behavioral and home maintenance strategies. However, if insecticides become emphasized as the best or only solutions, SNEM's intervention into the song may limit perceptions of the effectiveness of alternative strategies or promote dependence on external intervention in the community. SNEM's participation in writing the song reveals a tension in how EE approaches are assumed to emphasize local voices but how they must also include national voices to gain funding and support from governmental actors. That is, although we privilege the voice of the community because of our commitment to participatory research and intervention, practical matters of governmental and funding relations for other portions of the project must also be brought into the equation. The co-participatory design of this song reveals that there are opportunities for experts to intervene in ways that both enable and disable community voices, with potentially supportive or unsupportive effects for preventing risk factors for neglected tropical diseases.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board, Ohio University, Comité de Ética de la Investigación en Seres Humanos, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MG and EB contributed conceptualization and design of the study and collected primary data. BB organized, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, conducted fieldwork related to the study, and the larger project. MG coordinated community involvement and participation from local institutions. DS wrote sections of the manuscript and performed primary theoretical conceptualization of the study. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Financial support were received from the UNICEF/UNPD/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) [A20785] Pan American Health Organization [A60655] National Institutes of Health (DMID/NIADID/NIH) [AI077896-01], the National Chagas Control Program-Ecuadorian Ministry of Health, Plan Internacional Ecuador, Children's Heartlink USA and the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (DMID/NIADID/NIH), Ohio University and Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (PUCE). Funding agencies did not play any role on the design of the study or in the data analyses and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Balabarca, L. (2014). “Social denunciation of the politics of fear: rock music through the eighties in Argentina, Chile, and Peru,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 77–90.

BBC (2006). Detective Vijay Series Tops the Audience Ratings in India - HIV and AIDS Awareness Messages Reach 16 Million. Retrieved from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2006/09_september/01/vijay.shtml

Blades, R. (2009). “Interview with rubén blades: the graduate center, NYC, November 24, 2009,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 175–188.

Brown, R. (2010). “Interview with roy brown: mayagüez, puerto rico, July 8, 2010,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 189–202.

Brown, V., Barbería, L., and Gutiérrez, A. (2010). “Interview with vanito brown, luis barbería, and alejandro gutiérrez: habana abierta interview, Madrid, Spain, May 15, 2010,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 203–214.

Chidester, P. J. and Baldwin, J. R. (2014). “Shattering myths: Brazil's Tropicália movement,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 27–48.

Communication Initiative (2011). Jasoos Vijay. Retrieved from: www.comminit.com

Conquergood, D. (1988). Health theatre in a Hmong refugee camp. Theater Drama Rev. 32, 174–207. doi: 10.2307/1145914

Conquergood, D. (2002). Performance studies: interventions and radical research. Theater Drama Rev. 46, 145–156. doi: 10.1162/105420402320980550

Corona, I. (2014). “The politics of language, class, and nation in Mexico's Rock en español movement,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 91–122.

Dumonteil, E., Herrera, C., Martini, L., Grijalva, M.J., Guevara, A.G., Costales, J.A., et al. (2016). Chagas disease has not been controlled in Ecuador. PLoS ONE 11:e0158145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158145

Esterrich, C. (2014). “Music and agency. Singing the city, documenting modernization: Cortijo y su combo and the insertion of the urban in 1950s Puerto Rican culture,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 9–26.

FC Barcelona (2016). “Las palabras no dan miedo,” per guanyar la por a la malaltia del Chagas. YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3N2auDpnTDs

FUNDASAL – EL SALVADOR (2010, August 25.). Cancion sobre el Mal de Chagas. YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CE3MjeHTarU.

Grijalva, M. J., Suarez-Davalos, V., Villacis, A. G., Ocana-Mayorga, S., and Dangles, O. (2012). Ecological factors related to the widespread distribution of sylvatic Rhodnius ecuadoriensis populations in southern Ecuador. Parasit. Vecto. 5:17. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-17

Grijalva, M. J., Villacis, A. G., Ocana-Mayorga, S., Yumiseva, C. A., and Baus, E. G. (2011). Limitations of selective deltamethrin application for triatomine control in central coastal Ecuador. Parasit. Vect. 4:20. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-20

Grijalva, M. J., Villacis, A. G., Ocana-Mayorga, S., Yumiseva, C. A., Moncayo, A. L., and Baus, E. G. (2015). Comprehensive survey of domiciliary triatomine species capable of transmitting Chagas Disease in Southern Ecuador. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9:e0004142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004142

Igartua, J.J., and Vega, J. (2014). Processes and Mechanisms of Narrative Persuasion in Entertainment-Education Interventions through Audiovisual Fiction: The Role of Identification With Characters. Communication Initiative Network. Available online at: http://www.comminit.com/global/content/processes-and-mechanisms-narrative-persuasion-entertainment-education-interventions-thro (accessed August 17, 2019).

INEC (2010). Resultados del Censo 2010 de Población y Vivienda en el Ecuador. Retrieved from: www.inec.gob.ec

junnaka (2006). Video y Cancion sobre la Enfermedad de Chagas. YouTube. Abailable online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xx8jiSs6OCw

Luzuriaga, G. (Ed.). (1978). Popular Theater for Social Change in Latin America. Los Angeles: University of California Los Angeles Latin American Center Publications.

Mare (2012). Interview with Mare: Skype (Oaxaca, Mexico – Ithaca, New York) June 27, 2012,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 227–236.

McCarthy, J., and Galvão, K. (2004). Enacting Participatory Development Theatre Based Techniques. New York, NY: Routledge.

Molyneaux, D. H., Savioloi, L., and Engels, D. (2016). Neglected tropical diseases: progress towards addressing the chronic pandemic. Lancet 389, 312–325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30171-4

Nariman, H. (1993). Soap Operas for Social Change: Toward a Methodology for Entertainment-Education Television. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Nieto-Sanchez, C., Baus, E. G., Guerrero, D., and Grijalva, M. J. (2015). Positive deviance study to inform a Chagas disease control program in southern Ecuador. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 110, 299–309. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760140472

Patterson, N. M., Bates, B. R., Chadwick, A. E., Nieto-Sanchez, C., and Grijalva, M. J. (2018). Using the health belief model to identify communication opportunities to prevent Chagas disease in Southern Ecuador. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12:e0006841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006841

Piowtrow, P. T., Kincaid, D. L., Rimon II, J. G., and Rinehart, W. (1997). Health Communication: Lessons From Family Planning and Reproductive Health. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Prokhorov, S. (2018). Mine Risk Education Via Entertainment Education. Communication Initiative Network. Available online at: http://www.comminit.com/global/content/mine-risk-education-entertainment-education (accessed August 17, 2019).

Reisig, V., and Wildner, M. (2008). “Prevention, primary,” in Encyclopedia of Public Health, ed W. Kirch (Berlin: Springer Verlag), 1141–1143.

Riley, A. H., Sood, S., and Robichaud, M. (2017). Participatory methods for entertainment-education: analysis of best practices. J. Creat. Commun. 12, 62–76. doi: 10.1177/0973258616688970

Sabido, M. (1989). Soap operas in Mexico. Paper presented at the Entertainment for Social Change Conference. Los Angeles: University of Southern California, Annenberg School of Communication.

Samuels, A. M., Clark, E. H., Galdos-Cardenas, G., Wiegand, R. E., Ferrufino, L., Menacho, S., et al. (2013) Epidemiology of and impact of insecticide spraying on chagas disease in communities in the bolivian Chaco. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002358.

Sharma, D. (2012). “Indigenous performance art forms as spaces for social reflection and participatory communication in directed social change” in Development Communication in Directed Social Change: A Reappraisal of Theories and Approaches, ed S. R. Melkote (Singapore: Asian Media Information Centre), 169–196.

Singhal, A. (2001). Facilitating community participation through communication. A Report by GPP, Programme Division. New York, NY: UNICEF. Available online at: http://utminers.utep.edu/asinghal/reports/Singhal-UNICEF-Participation-Report.pdf (accessed October 26, 2018).

Singhal, A., Obregon, R., and Rogers, E. M. (1994). Reconstructing the story of “Simplemente Maria,” the most popular telenovela in Latin America of all time. Gazette 54, 1–15.

Singhal, A., and Rattine-Flaherty, E. (2006). Pencils and photos as tools for communicative research and praxis: analyzing Minga Peru's quest for social justice in the Amazon. Int. Commun. Gazette 68, 313–330. doi: 10.1177/1748048506065764

Singhal, A., and Rogers, E. M. (1988). Television soap operas for development in India. Gazette 41, 109–126.

Singhal, A., and Rogers, E. M. (1999). Entertainment-Education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Singhal, A., and Rogers, E. M. (2001). “The entertainment-education strategy in communication campaigns,” in Public Communication Campaigns, 3rd edn, eds R. E. Rice and C. Atkins (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 343–356.

Singhal, A., and Rogers, E. M. (2002). A theoretical agenda for entertainment-education. Commun. Theory 12, 117–135. doi: 10.1093/ct/12.2.117

Tijoux, A. (2012). “Interview with ana tijoux: Boston, Massachusetts, May 15, 2012,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 215–226.

Ureña, J. C. (2014). “The mockingbird still calls for Arlen: Central American songs of rebellion, 1970-2010,” in Song and Social Change in Latin America, ed L. Shaw (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 49–76.

Villa, B. (2014). The Militant Song Movement in Latin America: Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Wallack, L. (1990). Two approaches to health promotion in the mass media. World Health Forum 11, 143–155.

WHO (2018). Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis)

Appendix

Keywords: Chagas disease, song (or singing), community-based participatory, entertainment education strategy, rural comminitites, Ecuador (country)

Citation: Bates BR, Sharma D, Baus EG and Grijalva MJ (2020) En Nuestra Casa No Hay Chinchorros: A Youth-Oriented, Participatory Approach to Chagas Prevention in Guara, Loja Province, Ecuador. Front. Commun. 5:18. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00018

Received: 16 January 2020; Accepted: 11 March 2020;

Published: 15 April 2020.

Edited by:

Elizabeth M. Glowacki, Northeastern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Azael Saldana, Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Studies, PanamaIgnacio Llovet, National University of Luján, Argentina

Marli Maria Lima, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), Brazil

Copyright © 2020 Bates, Sharma, Baus and Grijalva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Benjamin R. Bates, YmF0ZXNiQG9oaW8uZWR1

Benjamin R. Bates

Benjamin R. Bates Devendra Sharma

Devendra Sharma Esteban G. Baus

Esteban G. Baus Mario J. Grijalva

Mario J. Grijalva